Abstract

How can gratitude interventions be designed to produce meaningful and enduring effects on people’s well-being? To address this question, the author proposes the Catalyst Model of Change—this novel, practical, and empirically testable model posits five socially oriented behavioral pathways that channel the long-term effects of gratitude interventions as well as how to augment gratitude experiences in interventions to boost treatment effects and catalyze these behavioral pathways. Specifically, interventions that enhance the frequency, skills, intensity, temporal span, and variety of gratitude experiences are likely to catalyze the following post-intervention socially oriented behaviors: (a) social support–seeking behaviors, (b) prosocial behaviors, (c) relationship initiation and enhancement behaviors, (d) participation in mastery-oriented social activities, and (e) reduced maladaptive interpersonal behaviors, which, in turn, produce long-term psychological well-being. A unique feature of the Catalyst Model of Change is that gratitude experiences are broadly conceptualized to include not just gratitude emotions, cognitions, and disclosures, but also expressing, receiving, witnessing, and responding to interpersonal gratitude. To this end, gratitude interventions that provide multiple opportunities for social experiences of gratitude (e.g., members expressing gratitude to each other in a group) might offer the greatest promise for fostering durable, positive effects on people’s psychological well-being.

Keywords: Gratitude, Thankful, Psychological well-being, Interventions, Positive emotions

Many people believe that gratitude is beneficial for their psychological well-being, yet struggle with practicing gratitude. In this regard, gratitude interventions are a popular means to help people cultivate gratitude (Wood et al., 2010). Indeed, over the past 20 years, such interventions have emerged as one of the most popular applications of positive psychology, perhaps because of their ease of implementation and scalability (Davis et al., 2016). Empirical evaluations of gratitude interventions typically involve self-help activities, especially gratitude journaling (e.g., listing what one is grateful for daily for 2 weeks; Emmons & McCullough, 2003) and writing letters of gratitude (Toepfer et al., 2012).

Gratitude interventions have been widely applied to improve the well-being of varied populations, such as children and adolescents (Froh et al., 2009), school teachers (Chan, 2010), psychotherapy clients (Wong et al., 2018), student athletes (e.g., Gabana et al., 2022), women with breast cancer (Sztachańska et al., 2019), suicidal inpatients (Huffman et al., 2014), and health care practitioners (Cheng et al., 2015) in diverse countries (e.g., Heckendorf et al., 2019; Sztachańska et al., 2019; Valdez et al., 2022). Despite their popularity, evidence for the efficacy of gratitude interventions has been mixed. For one thing, several meta-analyses have shown that intervention effects vary depending on the nature of the control conditions (Cregg & Cheavens, 2021; Davis et al., 2016; Dickens, 2017). Of concern, these analyses found medium effect sizes for gratitude interventions when compared to waitlist controls but only trivial effects, relative to activity-matched conditions (e.g., a daily activity journal; Cregg & Cheavens, 2021; Davis et al., 2016). For another, the positive effects of gratitude interventions wane over time (Cheng et al., 2015). Empirical evaluations of gratitude interventions have typically been short to medium term in nature (e.g., 1–6 months; Seligman et al., 2005), and, importantly, no published study has evaluated the long-term effects of gratitude interventions (defined, in this article, as 1 year and beyond). What is also missing is a theory of change that explains the positive effects of a gratitude intervention over a long period of time (Miller et al., 2017). Theorizing and research on enhancing the magnitude and durability of treatment effects are essential if gratitude interventions are to be widely disseminated and to understand how benefits from an intervention unfold over time to change people’s lives (Cohn & Fredrickson, 2010; Davis et al., 2016).

Therefore, in this article, I address the following question—how can interventionists design gratitude interventions with meaningful 1 and durable effects on people’s well-being? To this end, I develop the Catalyst Model of Change (CMC), which posits (a) the pathways that mediate the long-term effects of gratitude interventions on psychological well-being as well as (b) how to augment gratitude experiences within an intervention to boost the magnitude and durablity of intervention effects as well as facilitate these behavioral pathways. The model synthesizes empirical and conceptual insights from the psychology of gratitude (e.g., Emmons & Mishra, 2011), positive psychology interventions (e.g., Carr et al., 2021), and the long-term effects of social psychological interventions (e.g., Miller et al., 2017; Walton & Wilson, 2018).

Before describing the CMC, I provide clarifications on terminology. Following Emmons and Stern (2013), gratitude is defined as the appreciation of goodness in one’s life and acknowledgment that the sources of one’s benefits reside partially outside oneself (e.g., family members, friends, one’s community, and/or God). Put differently, gratitude is a social virtue in which people appreciate the benefits they receive from their benefactors (Emmons & Mishra, 2011). I further define gratitude experiences as those that include gratitude emotions, cognitions, and disclosures (e.g., sharing with a friend what one wrote in a gratitude journal) as well as expressing, receiving, witnessing, and responding to interpersonal gratitude. Notably, this definition is more encompassing than the types of activities found in most gratitude interventions, which focus mainly on gratitude emotions and cognitions (gratitude journaling) or expressing gratitude to someone (gratitude letters). And, as I will show, interventions that incorporate the full range of gratitude experiences described in this definition might offer the most optimal opportunities to effect long-term psychological benefits. Additionally, psychological well-being is conceived as a constellation of mental health indicators that include reduced psychopathology (e.g., depression), increased subjective well-being (e.g., more frequent positive emotions), and enhanced eudemonic well-being, which includes outcomes such as meaning in life, personal growth, and self-acceptance (Wood et al., 2010).

Catalyst Model of Change

The CMC proposes several key propositions about the mechanisms of change in the long-term effects of gratitude interventions, which I outline here and elaborate in subsequent sections. First, in well-designed gratitude interventions, gratitude experiences are catalysts that set in motion a series of pathways that effect meaningful and durable improvements in people’s psychological well-being. An analogy from the function of enzymes, a type of catalyst in the literal sense, helps illuminate the role of gratitude interventions. Enzymes improve the performance of many commercial applications (e.g., enhancing the washing performance of laundry detergents), but are often, not in themselves, the core compound in these applications (Wiltschi et al., 2020). Likewise, I argue that gratitude experiences in an intervention unleash the full potential of psychological and behavioral processes to improve well-being, although the long-term effects of a gratitude intervention are likely driven more by post-intervention variables than by the original gratitude experiences that occur during the intervention. This insight is congruent with scholarly observations on the nature of change in long-lag evaluations of social psychological interventions (Miller et al., 2017). That is, over the long run, activities in an intervention play a less crucial and direct role in propelling an intervention’s effects. For instance, a 1-hour intervention to improve students’ sense of belongingness to college improved the grade point average of Black students 3 years later (Walton & Cohen, 2011) and increased their psychological well-being 7–11 years, as compared to controls (Brady et al., 2020). Ironically, 92% of intervention participants could not accurately recall the core message of the intervention by their final year of college and most did not attribute their success to the intervention (Walton & Cohen, 2011). The message of belongingness, in itself, did not improve participants’ academic performance or well-being years later. Rather, it provided participants with new interpretations of themselves and their campus environments that then catalyzed behaviors that afforded greater success in college and beyond (Brady et al., 2020). In the same vein, the catalytic role of gratitude experiences might explain a paradox in which gratitude interventions have demonstrated weaker effects on increasing gratitude than on improving psychological well-being, relative to waitlist controls (Davis et al., 2016), and intervention effects on gratitude dissipate faster than those on mental health (Gabana et al., 2022; Wong, Gabana, et al., 2017). This does not imply that gratitude experiences in an intervention are unimportant; rather, as I will explain in the sections below, a short-term boost in gratitude experiences can jumpstart other psychological and behavioral processes that then propel the long-term benefits of the intervention over time (Miller et al., 2017).

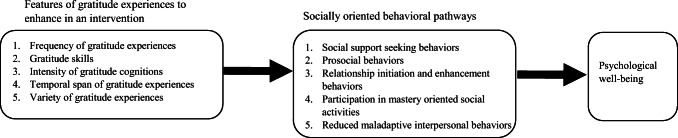

Second, if gratitude experiences play a catalytic role in gratitude interventions, the CMC proposes that participants’ post-intervention behaviors are the primary and proximal drivers of long-term change. Specifically, I identify five socially oriented behavioral pathways that mediate the long-term effects of gratitude interventions (Fig. 1). This focus on socially oriented behaviors, rather than generic behaviors, dovetails with the notion of gratitude as an other-oriented virtue (Emmons & Mishra, 2011). Further, the emphasis on socially oriented behaviors is novel insofar as theories of change for most positive psychological interventions, including gratitude interventions, tend to emphasize a broader array of psychological processes, such as emotions and cognitions (e.g., Cohn & Fredrickson, 2010; Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013; Wood et al., 2010). By contrast, Miller et al. (2017) have called for theories of change that emphasize behaviors in long-lag intervention studies in contrast to other psychological pathways in short-term evaluations of interventions.

Fig. 1.

Catalyst Model of Change. Note: The Catalyst Model of Change illustrates how features of gratitude experiences in an intervention can be enhanced to catalyze post-intervention socially oriented behavioral pathways, which, in turn, increase long-term psychological well-being

A focus on socially oriented behavioral pathways makes sense for several reasons. When assessing the long-term effects of an intervention, what participants do after a post-intervention cannot merely be treated as statistical noise because participants may use the psychological gains from the intervention (e.g., new insights) to modify their social context (e.g., initiate new relationships), thereby propelling the intervention effects over time (Kenthirarajah & Walton, 2015). Indeed, according to Walton and Wilson’s (2018) conceptualization of wise interventions, participants’ post-intervention behaviors often modify recursive cycles involving interactions with their social environments over time, thereby forming a positive feedback loop. To illustrate, gratitude experiences during an intervention might inspire a participant to appreciate their spouse, resulting in relationship enhancement behaviors (e.g., more verbal expressions of gratitude), which then triggers a positive response from the spouse (Algoe, 2012). The spouse’s response, in turn, reinforces the participant’s relationship enhancement behaviors and increases relationship intimacy, thereby fostering a positive upward spiral. Centralizing the role of behavioral pathways does not mean that other psychological processes are not implicated in the process of long-term change. Indeed, I outline below some of the cognitive-affective processes that link gratitude experiences to socially oriented behaviors. However, it may be easier for participants to report modifications to their own behaviors (e.g., I sought advice from a mentor), which are more concrete, rather than changes in their internal psychological dispositions, because people may have less insight into how their core beliefs, affect, and identities have evolved over time and are often motivated to maintain their self-views (North & Swann, 2009). For example, researchers have found that people’s self-reported core beliefs tend to be stable over time and resistant to psychotherapy treatment in contrast to large reductions in depressive symptoms over time (Renner et al., 2012). Moreover, from a practical standpoint, if researchers identify adaptive behavioral pathways from a long-lag intervention study, interventionists can redesign an intervention to include opportunities to practice these behaviors (Miller et al., 2017).

Third, the CMC proposes five features of gratitude experiences within an intervention that can increase the magnitude of intervention effects and catalyze the five behavioral pathways (see Fig. 1). What follows is a discussion of the five socially oriented behaviors and the five features of gratitude experiences.

Socially Oriented Behaviors

As seen in Fig. 1, the CMC posits five socially oriented behaviors that serve as pathways to psychological well-being in long-lag gratitude interventions.

Social Support–Seeking Behaviors

Gratitude experiences during an intervention might engender greater social support–seeking behaviors (e.g., asking for help), which can help participants better cope with stress and improve their well-being over the long term (Taylor, 2011). Although no study has identified social support seeking as a behavioral pathway in long-lag gratitude interventions, an evaluation of a belongingness intervention for Black college students showed that greater college mentoring experiences (a form of social support seeking) was the only variable that mediated the intervention effects on psychological well-being outcomes 7–11 years later (Brady et al., 2020). Importantly, support for the link between gratitude and social support was demonstrated in cross-lagged longitudinal studies showing that gratitude predicted subsequent perceived social support, but perceived social support did not predict subsequent gratitude (Wood et al., 2008). Why would gratitude experiences promote social support seeking behaviors? According to the (Fredrickson, 2001, 2004) broaden-and-build theory, positive emotions, including gratitude, momentarily expand individuals’ range of thoughts and behaviors and that the repetition of these broadened states enhance their long-term psychosocial resources. Experiencing the emotion of gratitude during an intervention might broaden participants’ thoughts concerning the means through which and people from whom they can seek social support, as well as reasons why they can trust others for support. Some indirect evidence for this perspective was found in a study in which gratitude journaling enhanced participants’ trust of other people during social interactions, which was mediated by the experience of more positive emotions (Drążkowski et al., 2017).

Prosocial Behaviors

According to McCullough et al.’s (2001) moral affect theory of gratitude, gratitude serves as a moral motivator to reciprocate a benefactor’s kindness and to enact other types of prosocial behaviors unrelated to the benefactor (e.g., helping a stranger or being kind to a colleague). Put differently, gratitude amplifies the good within a person, thereby facilitating one’s capacity to be good to others (Watkins, 2014). Indeed, studies have demonstrated that both receiving gratitude (Grant & Gino, 2010) and experiencing gratitude increase prosocial behaviors (Ma et al., 2017). In turn, prosocial behaviors foster greater psychological well-being (Nelson et al., 2015; Weinstein & Ryan, 2010), perhaps by cultivating meaning in life (Klein, 2017). Hence, gratitude experiences within an intervention could inspire post-intervention prosocial behaviors that then strengthen long-term well-being.

Relationship Initiation and Enhancement Behaviors

Algoe’s (2012) find-remind-and-bind theory of gratitude posits that gratitude helps people develop new relationships when they appreciate strengths in others that were previously unnoticed, reminds people of positive characteristics in current relationships, and strengthens the bonds of existing relationships by signaling that other people care about them. Therefore, gratitude experiences within an intervention could promote relationship initiation and enhancement behaviors (e.g., inspiring participants to deepen an existing friendship) that contribute to relationship satisfaction, reduced loneliness, and, ultimately, long-term psychological well-being (Fincham et al., 2018; Whitton & Whisman, 2010). Indeed, several studies have found support for the notion that gratitude emotions and expressions predict subsequent relationship closeness (e.g., Algoe et al., 2016; O’Connell et al., 2017).

Participation in Mastery-Oriented Social Activities

Gratitude experiences in an intervention might also boost participation in mastery-oriented social activities, which I define as socially centered activities that involve skills, challenge, or creativity. These include engagement in group-based sports, leadership activities, and socially oriented hobbies (e.g., singing in a choir). Gratitude experiences could help people view their life experiences and other people more positively (Watkins et al., 2021; Wong, McKean Blackwell, et al., 2017). This may, in turn, increase their willingness to affiliate with other people and their self-esteem (Rash et al., 2011), thereby bolstering participants’ engagement in mastery-oriented social activities. Mastery-oriented social activities may further bolster self-efficacy, and, when coupled with opportunities for social interactions, can increase people’s social connectedness and long-term psychological well-being (Cohen et al., 2006; Kanter et al., 2010).

Reductions in Maladaptive Interpersonal Behaviors

Finally, gratitude experiences during an intervention might reduce participants’ maladaptive interpersonal behaviors, such as withdrawing from others, aggressive behaviors, excessive reassurance seeking, and overreaction to social rejection, which are implicated in poorer mental health because other people tend to react negatively to such behaviors (Fearey et al., 2021). Moreover, a reduction of maladaptive interpersonal behaviors could improve people’s long-term well-being by reducing barriers to social connectedness (Teyber & Teyber, 2017). Gratitude experiences reduce participants’ maladaptive interpersonal behaviors by improving their self-regulatory resources (Locklear et al., 2021). Specifically, studies suggest that gratitude interventions might reduce people’s negative emotions (Wong et al., 2018), negative cognitions (Heckendorf et al., 2019), and aggressive behaviors (Deng et al., 2019). Importantly, one study found that the impact of a gratitude intervention on reducing uncivil workplace behaviors was mediated by improvement in self-regulatory resources (Locklear et al., 2021). When people turn their attention to appreciating what is positive in their lives, they might be better able to regulate their negative emotions (e.g., anxiety about social situations) and cognitions (e.g., belief that others will reject them), thereby reducing the frequency of deleterious interpersonal behaviors.

Enhancing the Features of Gratitude Experiences in Interventions

If socially oriented behaviors are proximal pathways linking gratitude interventions to long-term change in psychological well-being, gratitude experiences within an intervention serve as catalysts to boost the magnitude of intervention effects and foster these behavioral pathways. According to the CMC (Fig. 1), the enhancement of the following five features of gratitude experiences amplifies the magnitude and durability of intervention effects.

Frequency of Gratitude Experiences

First, gratitude interventions that provide frequent gratitude experiences are likely to have larger and more durable treatment effects. Although not focused specifically on gratitude interventions, meta-analytic research on positive psychology interventions has found that interventions with more sessions and were of longer duration generally exerted stronger effects (Carr et al., 2021). The best example of frequent gratitude experiences in an intervention is gratitude journaling, in which participants are instructed to list what they are grateful for across multiple time points (e.g., every day for a few weeks; Emmons & McCullough, 2003). Not surprisingly, research suggests that participants who participate in more frequent gratitude journaling demonstrate the greatest benefits from the intervention (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006). A key benefit of repeated activities is that it aids in the formation of a habit, such that gratitude journaling attains a quality of automaticity, thereby requiring less conscious effort to maintain (Wood & Neal, 2007). On this matter, interventionists can teach and encourage participants to apply best practices from the psychology of habits to aid habit formation (Gardner et al., 2012). For instance, implementation intentions, which involve specifying behaviors and situations in which the behaviors will occur, have been successfully used to help people achieve their goals and form new habits (Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006). Such practices can easily be taught to participants by encouraging them to specify a consistent context and time in which they will engage in gratitude journaling (e.g., while waiting for coffee to brew each morning, I will enter three things I’m grateful for in the gratitude app on my phone). I also propose that gratitude interventions are more likely to promote a higher frequency of gratitude experiences when participants are recruited from recursive social contexts, such as couples, families, schools, organizations, and sports teams (e.g., Gabana et al., 2022). In such environments, participants often know some or even all the participants in the intervention and are, therefore, afforded opportunities to immediately practice with each other what they have learned from a gratitude intervention in their naturalistic social environments, thereby increasing the frequency of gratitude experiences. For example, if an entire soccer team participates in a gratitude intervention and collectively learns the value of expressing interpersonal gratitude, this insight can be instantly applied to increase gratitude expressions to teammates during soccer practices.

Gratitude Skills

Second, whereas most gratitude interventions are self-help activities (i.e., participants perform an activity with no ongoing guidance from interventionists; Davis et al., 2016), meta-analyses of positive psychological interventions have found that interventions with face-to-face individual or group-based formats generally confer stronger treatment effects (Carr et al., 2021). Simply put, a just-do-it approach to gratitude interventions might be insufficient to trigger the catalytic effect of gratitude experiences if participants lack the self-efficacy to initiate or persist in performing a gratitude activity (Wong, Gabana, et al., 2017). Indeed, the formidable challenges of self-help gratitude interventions is seen in intervention studies that reveal high levels of participant attrition (e.g., 70% attrition rate in a gratitude journaling intervention; Geraghty et al., 2010). Furthermore, research has shown that people have lower self-efficacy about writing a gratitude letter, compared to gratitude journaling, which then decreases their rate of completion (Kaczmarek et al., 2015). Moreover, if a gratitude intervention consists of recurrent gratitude journaling (e.g., daily gratitude journaling for several weeks), participants might experience hedonic adaptation or run out of things to write about after multiple journal entries. Accordingly, gratitude interventions that provide skills and resources to help participants optimize their experiences of gratitude are likely to be more successful. For example, interventionists could help participants introduce variety into the content of their gratitude journaling entries by providing a list of prompts to help participants think of diverse topics to write about (Wong, Gabana, et al., 2017). Interventionists can also help scaffold participants’ experience of writing a gratitude letter by offering suggestions on the content (e.g., encouraging participants to discuss the cost and altruistic intentions of the benefactor’s action and its positive impact on their lives; Froh et al., 2014). Additionally, in a group-based format for gratitude interventions, group members who are skillful in gratitude practices (e.g., ability to be specific about what they are grateful for) could serve as role models to those who are less skillful since their expressions of gratitude are witnessed by the entire group (Wong, Gabana, et al., 2017).

I also propose a series of cognitive skills that interventionists could address in gratitude interventions. Because grateful people are more likely to notice the good in their lives, possess a grateful memory bias, and embrace benevolent interpretations of the benefits they receive (Watkins, 2014), interventions that help people improve in these three areas are likely to produce salutary effects. To help participants attend to the good in their lives, interventionists could use a series of prompts to help them notice and record the simple pleasures in their lives (e.g., what they like about their home and why they are grateful for it). Interventionists could also use cognitive bias modification (e.g., computer tasks that guide participants toward more grateful interpretations of ambiguous situations) to help participants develop more benevolent appraisals of benefits (Watkins et al., 2021). Furthermore, participants could be taught how to develop a grateful memory bias. While maintaining a gratitude journal would be one obvious way to encode grateful memories, other strategies may include identifying what is novel and surprising about a grateful experience as well as sharing one’s grateful experiences with other people (Fernández & Morris, 2018; Lambert et al., 2013; Pasupathi, 2007).

Intensity of Gratitude Cognitions

Third, interventions that amplify the intensity of gratitude cognitions are likely to be more successfully in catalyzing the behavioral pathways in the CMC. Gratitude cognitions are considered more intense when they are more deeply believed, respectively. In this respect, gratitude activities that involve reflecting or writing extensively about one’s life experiences (e.g., for 20 minutes) or writing a heartfelt gratitude letter to someone are more likely to generate more intensely grateful thoughts than conventional gratitude journaling that merely involves listing what one is grateful for. This is because the former activities emphasize depth of experiences and might enable participants to better understand not just what they are grateful for but also why they are grateful (Payne et al., 2020). Moreover, when using gratitude to process painful experiences, writing extensively on a focused topic (e.g., writing about gratitude for the consequences of a painful experience for 20 minutes; Watkins et al., 2008) can help people better organize their thoughts and create a narrative that fuels insight (Pennebaker et al., 1997), thereby deepening their grateful thoughts. In turn, the intensity of gratitude cognitions could confer the motivational resources needed to pursue the aforementioned socially oriented behaviors described in the CMC (Gendolla, 2017).

Temporal Span of Gratitude Experiences

Fourth, I theorize that interventions with a longer temporal span of gratitude—namely, exploration of gratitude experiences associated with both present/recent events as well as past events over a long period of time in their lives—are more likely to be effective than those that focus only on present and recent events. When people describe their past self in negative terms, they also tend to believe the same attributes will characterize their lives in the future (Markus & Nurius, 1986; Peetz & Wilson, 2008). Hence, altering people’s dysfunctional interpretations of their past (including experiences from their distant past) might boost their self-worth and change the way they interact with their social world in the future. For example, a person who changes their view of the past to include gratitude for the support they received from others during difficult times might increase their social support–seeking behaviors. In this respect, conventional gratitude journaling (in which participants list what they are grateful for) might not adequately address the temporal span of gratitude experiences because people tend to focus more on current or recent events when they list what they are grateful for (e.g., Ghosh & Deb, 2017). Instead, to increase the temporal span of gratitude experiences, interventionists could incorporate journaling activities that explicitly encourage participants to express gratitude for major events from different periods of their lives in the past (e.g., childhood, adolescence, and emerging adulthood; Serrano et al., 2004; Wong, Gabana, et al., 2017). Relatedly, people might have painful experiences from the past that have a disproportionately negative influence on their current lives because these constitute an open memory (i.e., unfinished business), which generates intrusive thoughts, aversive emotions, and lowered self-esteem (Beike & Wirth-Beaumont, 2005). For instance, the experience of a traumatic event many years ago might continue to haunt an individual in the present because it disrupts one’s fundamental assumption about the world’s benevolence (Janoff-Bulman, 1992). In this regard, Watkins et al. (2008) found that college students’ grateful processing of such open memories through journaling about the positive consequences of painful experiences brought greater memory and emotional closure. I therefore recommend that gratitude interventions incorporate a version of this activity to increase the temporal span of their gratitude experiences.

Variety of Gratitude Experiences

Finally, interventions with a wider variety of gratitude experiences are likely to be more successful in catalyzing the behavioral pathways in the CMC and effecting long-term benefits. Because gratitude experiences encompass not just gratitude emotions, cognitions, and disclosures, but also expressing, receiving, witnessing, and responding to interpersonal gratitude, interventions that encompass the full range of gratitude experiences will likely require diverse types of activities; these include gratitude journaling, gratitude letter writing, disclosing to someone what one is grateful for, and opportunities to express gratitude to another person in the presence of others (Wong, Gabana, et al., 2017). In this regard, group-based activities, either in an online (e.g., Valdez et al., 2022) or in a face-to-face format (e.g., Deng et al., 2019), provide the ideal forum for diverse types of gratitude experiences. To illustrate, in Wong and colleagues’ multisession Gratitude Group Program, group members are encouraged, during the last 5 minutes of each session, to orally express gratitude to other group members for something they learned from them in the presence of the entire group, thus conferring opportunities to receive, witness, and respond to interpersonal expressions of gratitude. Several studies attest to the benefits of diverse gratitude experiences. Similar to experiencing gratitude, receiving gratitude from someone else increases reciprocity and prosocial behaviors by boosting a person’s social worth (Grant & Gino, 2010). Notably, bystanders who witness the interpersonal expression of gratitude may experience elevation—the positive emotion felt when witnessing the virtuous behavior of others (Walsh et al., 2022) —which may then inspire a more positive view of humanity, a desire to become a better person, and increased prosocial behaviors (Thomson & Siegel, 2017). Moreover, third-party witnesses to interpersonal expressions of gratitude tend to behave more positively toward both the expressers and recipients of gratitude (Algoe et al., 2020). For instance, within a group-based intervention, a bystander who experiences elevation by witnessing the expression of gratitude might respond by praising the expresser of gratitude (for being grateful) or the recipient of gratitude (for being worthy of gratitude). Thus, in a group-based intervention, interpersonal expressions of gratitude might have a positive ripple effect that extends beyond the expresser and recipient of gratitude to the rest of the group. Importantly, when participants in a group-based intervention have ample in vivo opportunities to disclose, express, witness, receive, and respond to gratitude in relation to other group members, they also enact several of the aforementioned socially oriented behaviors (e.g., prosocial behaviors and relationship enhancement behaviors), thus strengthening the catalytic effects of the intervention on the behavioral pathways described in the CMC. Given the centrality of socially oriented behaviors in the CMC, I argue that social experiences of gratitude (i.e., opportunities to disclose one’s gratitude experiences to others and to express, receive, witness, and respond to interpersonal gratitude) may be the most distinctive feature of gratitude experiences in an intervention that drives enduring positive change.

Contributions, Implications, and Future Directions

In this penultimate section, I spotlight the uniqueness and contributions of the CMC as well as its implications for practice and future research. The CMC differs from other theoretical explanations of gratitude in at least two ways. For one thing, the CMC has a singular focus on gratitude interventions and does not tackle the broader question of why grateful people tend to have better well-being (Wood et al., 2010). In other words, my goal was not to explain why gratitude is generally beneficial, but, rather, what features of a gratitude intervention catalyze the pathways that generate positive effects on peoples’ well-being. For another, the CMC is unique in its focus on post-intervention, socially oriented behaviors as the key mechanisms mediating the positive, long-term effects of gratitude interventions. This emphasis on behaviors can be contrasted with other theories that highlight emotions (e.g., the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions; Fredrickson, 2004), cognitions (e.g., the amplification theory of gratitude; Watkins, 2014), and interpersonal relationships (the find-remind-and-bind theory of gratitude; Algoe, 2012). Although the find-remind-and-bind theory of gratitude dovetails with the CMC in its focus on the social dimension of people’s lives, only one of the five socially oriented behavioral pathways in the CMC—relationship initiation and enhancement behaviors—is accounted for in the find-remind-and-bind theory. The prominence of behaviors as key markers of change in the CMC reflects the reality that it may be easier for people to detect modifications in their own behaviors (e.g., I sought help from someone) after an intervention than changes in internal psychological processes, such as their self-concept (North & Swann, 2009).

Several implications can be gleaned from the CMC. Perhaps the most important recommendations are the need to (a) evaluate the long-term effects of gratitude interventions on psychological well-being (at least 1 year) and to (b) design interventions that have stronger and more long-lasting intervention effects. If gratitude is a socially oriented virtue, it is ironic that the most commonly researched gratitude intervention, gratitude journaling, is an individualistic activity that does not involve social experiences of gratitude (Davis et al., 2016). Hence, interventionists are encouraged to shift from brief, self-help gratitude interventions to longer, group-based, multicomponent interventions that enable people to disclose, express, receive, witness, and respond to gratitude (Gabana et al., 2022; Valdez et al., 2022; Wong, Gabana, et al., 2017). Such interventions might present the greatest promise for facilitating durable, positive effects on people’s well-being. Although such interventions are more intensive, they can still be scalable, accessible, and affordable. Online groups (e.g., private Facebook groups) could be used to enable participants to engage in group-based journaling and to express gratitude to each other (Valdez et al., 2022). Alternatively, groups could be modeled after Alcoholics Anonymous groups (Pagano et al., 2013) in which individuals commit to meeting regularly in no-cost support groups to encourage each other in the long-term practice of gratitude.

Researchers could assess the hypotheses within the CMC; namely, a serial multiple mediation model could be tested in which a well-designed gratitude intervention would increase the frequency, skills, intensity, temporal span, and variety of gratitude experiences by the conclusion of the intervention, which would, in turn, bolster the five socially oriented behaviors in the short term (e.g., 3 months later), thereby increasing long-term psychological well-being (e.g., 1 year later). One drawback of the CMC is that because multiple features of gratitude experiences in an intervention are theorized to improve well-being, it lacks parsimony and precision in identifying a single mechanism of change. However, I argue that a well-designed gratitude intervention with many components is analogous to psychotherapy in which there are multiple cognitive, behavioral, affective, and relational mechanisms of change (Lemmens et al., 2016); like psychotherapy, the myriad features of a well-designed, multicomponent gratitude intervention is probably the reason why such an intervention is more likely to produce enduring positive effects than a single-activity, self-help gratitude intervention. Nevertheless, given the prominence of social experiences of gratitude in the CMC (e.g., social opportunities to disclose, express, receive, witness, and respond to gratitude), researchers can use the dismantling research design commonly used in psychotherapy research (Papa & Follette, 2015) to test the hypothesis that such experiences of gratitude are a vital driver of change. That is, the efficacy of a gratitude intervention with in vivo group-based gratitude experiences could be compared to that of another gratitude intervention with similar activities (e.g., gratitude journaling) but without in vivo group-based gratitude experiences. Also, although I believe that multicomponent gratitude interventions offer the most promise in generating enduring well-being effects, each feature of gratitude experiences in the CMC can also be tested in isolation to evaluate a single-component gratitude intervention. For instance, researchers could test the relative efficacy of a gratitude journaling intervention that encourages participants to focus only on current or recent events versus a gratitude journaling intervention that incorporates a longer temporal span (e.g., gratitude for recent events and events from the distant past).

Researchers could also conduct moderation analyses to investigate who benefits most from gratitude interventions. A recent meta-analysis showed that positive psychology interventions demonstrated a stronger treatment effect in non-Western countries and in samples with a higher percentage of racially minoritized individuals (Carr et al., 2021). Because stigma surrounding mental health is a salient barrier for seeking professional psychological help in racially minoritized and non-Western populations (Clement et al., 2015), gratitude interventions, which emphasize the positive aspects of one’s life, may be a less stigmatizing and more appealing intervention for these populations (Wong, Gabana, et al., 2017). Moreover, I theorize, based on previous research (Rash et al., 2011), that gratitude interventions will be more effective in improving the well-being of people with lower levels of dispositional gratitude because highly grateful people may have already reaped the mental health benefits of practicing gratitude prior to an intervention. Additionally, research has shown that people with depressed mood tend to experience a disconnection between their past and present selves (Sokol & Eisenheim, 2016). Therefore, I posit that gratitude interventions that emphasize a longer temporal span (including gratitude for events in the distant past) may be more useful for people with depressed mood than those without because the process of experiencing gratitude for past events may help people with depression find positive connections between their past and present lives.

Finally, gratitude interventions may have to be modified to fit the needs of diverse populations, given that the meaning and expression of gratitude differ across cultures (Corona et al., 2020) and culturally adapted mental health interventions generally outperform non-adapted interventions for culturally diverse populations (Rathod et al., 2018). For instance, a gratitude intervention for Muslim participants could emphasize an Islamic concept of gratitude, which involves recognizing that blessings are from God and responding in gratitude by doing good deeds (Rusdi et al., 2021). Likewise, the efficacy of gratitude interventions may vary as a function of age because gratitude may require certain developmental competencies, such a possessing a theory of mind (recognizing that someone else has thoughts distinct from one’s own cognitions), an understanding of emotions, and perspective taking (e.g., ability to identify people’s benevolent intentions; Layous & Lyubomirsky, 2014). Hence, gratitude interventions may be less efficacious in promoting psychological well-being for very young children (e.g., those younger than 7 years old) who lack these developmental competencies.

Conclusions

In this article, I presented the CMC, a conceptual model that proposes five socially oriented behavioral pathways that mediate the long-term effects of gratitude interventions on psychological well-being as well as five features of gratitude experiences within an intervention that catalyze these behavioral pathways. The strengths of the CMC lie in its (a) novelty (focusing on long-lag interventions and on socially oriented behavioral pathways); (b) practicality (precisely specifying the features of gratitude experiences to enhance in an intervention); and (c) empirical falsifiability (providing directional hypotheses). My hope is that this article will stimulate innovative designs of interventions that will enable people to reap the full potential of gratitude practices to lead happier, healthier, and more fulfilling lives.

Acknowledgements

This writing of this article was supported by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation on Mental Healthcare, Virtue, and Human Flourishing (#61603). The author is also grateful to Jee Yoon Park for her help with library research.

Additional Information

Data availability

Not applicable

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Informed consent

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Code availability

Not applicable

Footnotes

I use the term “meaningful” to refer to the magnitude of intervention effects, while durability refers to whether an effect can be sustained over time after an intervention.

References

- Algoe SB. Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2012;6(6):455–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Algoe SB, Dwyer PC, Younge A, Oveis C. A new perspective on the social functions of emotions: Gratitude and the witnessing effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2020;119(1):40–74. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algoe SB, Kurtz LE, Hilaire NM. Putting the “you” in “thank you” examining other-praising behavior as the active relational ingredient in expressed gratitude. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2016;7(7):658–666. doi: 10.1177/1948550616651681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beike D, Wirth-Beaumont E. Psychological closure as a memory phenomenon. Memory. 2005;13(6):574–593. doi: 10.1080/09658210444000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady ST, Cohen GL, Jarvis SN, Walton GM. A brief social-belonging intervention in college improves adult outcomes for Black Americans. Science Advances. 2020;6(18):eaay3689. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A, Cullen K, Keeney C, Canning C, Mooney O, Chinseallaigh E, O’Dowd A. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2021;16(6):749–769. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DW. Gratitude, gratitude intervention and subjective well-being among Chinese school teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology. 2010;30(2):139–153. doi: 10.1080/01443410903493934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S-T, Tsui PK, Lam JHM. Improving mental health in health care practitioners: Randomized controlled trial of a gratitude intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(1):177–186. doi: 10.1037/a0037895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, Thornicroft G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(1):11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GD, Perlstein S, Chapline J, Kelly J, Firth KM, Simmens S. The impact of professionally conducted cultural programs on the physical health, mental health, and social functioning of older adults. The Gerontologist. 2006;46(6):726–734. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.6.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn MA, Fredrickson BL. In search of durable positive psychology interventions: Predictors and consequences of long-term positive behavior change. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2010;5(5):355–366. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2010.508883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona K, Senft N, Campos B, Chen C, Shiota M, Chentsova-Dutton YE. Ethnic variation in gratitude and well-being. Emotion. 2020;20(3):518–524. doi: 10.1037/emo0000582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregg DR, Cheavens JS. Gratitude interventions: Effective self-help? A meta-analysis of the impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2021;22(1):413–445. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00236-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DE, Choe E, Meyers J, Wade N, Varjas K, Gifford A, Quinn A, Hook JN, Van Tongeren DR, Griffin BJ, Worthington EL., Jr Thankful for the little things: A meta-analysis of gratitude interventions. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2016;63(1):20–31. doi: 10.1037/cou0000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Xiang R, Zhu Y, Li Y, Yu S, Liu X. Counting blessings and sharing gratitude in a Chinese prisoner sample: Effects of gratitude-based interventions on subjective well-being and aggression. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2019;14(3):303–311. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2018.1460687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens LR. Using gratitude to promote positive change: A series of meta-analyses investigating the effectiveness of gratitude interventions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2017;39(4):193–208. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2017.1323638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drążkowski D, Kaczmarek LD, Kashdan TB. Gratitude pays: A weekly gratitude intervention influences monetary decisions, physiological responses, and emotional experiences during a trust-related social interaction. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017;110:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, Mccullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(2):377–389. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, Mishra A. Why gratitude enhances well-being: What we know, what we need to know. In: Sheldon KM, Kashdan TB, Steger MF, editors. Designing positive psychology: Taking stock and moving forward. Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 248–262. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R. A., & Stern, R. (2013). Gratitude as a Psychotherapeutic Intervention. Journal of Clinical Psychology 69(8), 846–855. 10.1002/jclp.22020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fearey E, Evans J, Schwartz-Mette RA. Emotion regulation deficits and depression-related maladaptive interpersonal behaviours. Cognition and Emotion. 2021;35(8):1559–1572. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2021.1989668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández G, Morris RG. Memory, novelty and prior knowledge. Trends in Neurosciences. 2018;41(10):654–659. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Rogge R, Beach SRH. Relationship satisfaction. In: Vangelisti AL, Perlman D, editors. The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. Cambridge University Press; 2018. pp. 422–436. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist. 2001;56(3):218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In: Emmons RA, McCullough ME, editors. The psychology of gratitude. Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 145–166. [Google Scholar]

- Froh JJ, Bono G, Fan J, Emmons RA, Henderson K, Harris C, Leggio H, Wood AM. Nice thinking! An educational intervention that teaches children to think gratefully. School Psychology Review. 2014;43(2):132–152. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2014.12087440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Froh JJ, Kashdan TB, Ozimkowski KM, Miller N. Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention in children and adolescents? Examining positive affect as a moderator. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2009;4(5):408–422. doi: 10.1080/17439760902992464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gabana NT, Wong YJ, D’Addario A, Chow G. The Athlete Gratitude Group (TAGG): Effects of coach participation in a positive psychology intervention with youth athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 2022;34(2):229–250. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2020.1809551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B, Lally P, Wardle J. Making health habitual: The psychology of ‘habit-formation’ and general practice. British Journal of General Practice. 2012;62(605):664–666. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X659466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendolla GH. Comment: Do emotions influence action?–Of course, they are hypo-phenomena of motivation. Emotion Review. 2017;9(4):348–350. doi: 10.1177/1754073916673211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geraghty AWA, Wood AM, Hyland ME. Attrition from self-directed interventions: Investigating the relationship between psychological predictors, intervention content and dropout from a body dissatisfaction intervention. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(1):30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Deb A. An exploration of gratitude themes and suggestions for future interventions. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2017;27(7):678–693. doi: 10.1007/s12646-016-0367-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2006;38:69–119. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant AM, Gino F. A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98(6):946–955. doi: 10.1037/a0017935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckendorf H, Lehr D, Ebert DD, Freund H. Efficacy of an internet and app-based gratitude intervention in reducing repetitive negative thinking and mechanisms of change in the intervention's effect on anxiety and depression: results from a randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2019;119:103415. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JC, DuBois CM, Healy BC, Boehm JK, Kashdan TB, Celano CM, Denninger JW, Lyubomirsky S. Feasibility and utility of positive psychology exercises for suicidal inpatients. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2014;36(1):88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R. Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek LD, Kashdan TB, Drążkowski D, Enko J, Kosakowski M, Szäefer A, Bujacz A. Why do people prefer gratitude journaling over gratitude letters? The influence of individual differences in motivation and personality on web-based interventions. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;75(3):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter JW, Manos RC, Bowe WM, Baruch DE, Busch AM, Rusch LC. What is behavioral activation? A review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(6):608–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenthirarajah D, Walton GM. How brief social-psychological interventions can cause enduring effects. In: Scott R, Kosslyn S, editors. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. John Wiley and Sons; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Klein N. Prosocial behavior increases perceptions of meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2017;12(4):354–361. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1209541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, N. M., Gwinn, A. M., Baumeister, R. F., Strachman, A., Washburn, I. J., Gable, S. L., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). A boost of positive affect: The perks of sharing positive experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 30(1), 24–43. 10.1177/0265407512449400

- Layous K, Lyubomirsky S. Benefits, mechanisms, and new directions for teaching gratitude to children. School Psychology Review. 2014;43(2):153–159. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2014.12087441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens LH, Müller VN, Arntz A, Huibers MJ. Mechanisms of change in psychotherapy for depression: An empirical update and evaluation of research aimed at identifying psychological mediators. Clinical Psychology Review. 2016;50:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locklear LR, Taylor SG, Ambrose ML. How a gratitude intervention influences workplace mistreatment: A multiple mediation model. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2021;106(9):1314–1331. doi: 10.1037/apl0000825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Layous K. How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22(1):57–62. doi: 10.1177/0963721412469809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma LK, Tunney RJ, Ferguson E. Does gratitude enhance prosociality?: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2017;143(6):601–635. doi: 10.1037/bul0000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Nurius P. Possible selves. American Psychologist. 1986;41(9):954–969. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Kilpatrick SD, Emmons RA, Larson DB. Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(2):249–266. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, Dannals JE, Zlatev JJ. Behavioral processes in long-lag intervention studies. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2017;12(3):454–467. doi: 10.1177/1745691616681645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SK, Della Porta MD, Jacobs Bao K, Lee HC, Choi I, Lyubomirsky S. ‘It’s up to you’: Experimentally manipulated autonomy support for prosocial behavior improves well-being in two cultures over six weeks. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2015;10(5):463–476. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.983959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- North, R. J., & Swann, W. B. (2009). Self-verification 360°: Illuminating the Light and Dark Sides. Self and Identity 8(2–3), 131–146.10.1080/15298860802501516

- O’Connell BH, O'Shea D, Gallagher S. Feeling thanks and saying thanks: A randomized controlled trial examining if and how socially oriented gratitude journals work. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017;73(10):1280–1300. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano ME, White WL, Kelly JF, Stout RL, Tonigan JS. The 10-year course of Alcoholics Anonymous participation and long-term outcomes: a follow-up study of outpatient subjects in Project MATCH. Substance Abuse. 2013;34(1):51–59. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2012.691450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa, A., & Follette, W. C. (2015). Dismantling studies of psychotherapy. The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology, 1–6. 10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp523

- Pasupathi M. Telling and the remembered self: Linguistic differences in memories for previously disclosed and previously undisclosed events. Memory. 2007;15(3):258–270. doi: 10.1080/09658210701256456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne J, Babar H, Tse E, Moyer A. The Gratitude visit: Student reflections on a positive psychology experiential learning exercise. Journal of Positive School Psychology. 2020;4(2):165–175. doi: 10.47602/jpsp.v4i2.228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peetz J, Wilson AE. The temporally extended self: The relation of past and future selves to current identity, motivation, and goal pursuit. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2(6):2090–2106. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00150.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Mayne TJ, Francis ME. Linguistic predictors of adaptive bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72(4):863–871. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.4.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JA, Matsuba MK, Prkachin KM. Gratitude and well-being: Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention? Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being. 2011;3(3):350–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2011.01058.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rathod S, Gega L, Degnan A, Pikard J, Khan T, Husain N, Munshi T, Naeem F. The current status of culturally adapted mental health interventions: A practice-focused review of meta-analyses. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2018;14:165–178. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S138430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner F, Lobbestael J, Peeters F, Arntz A, Huibers M. Early maladaptive schemas in depressed patients: Stability and relation with depressive symptoms over the course of treatment. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136(3):581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusdi A, Sakinah S, Bachry PN, Anindhita N, Hasibuan MAI. The Development and validation of the Islamic Gratitude Scale (IGS-10) Psikis: Jurnal Psikologi Islami. 2021;7(2):120–142. doi: 10.19109/psikis.v7i2.7872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical Validation of Interventions. American Psychologist. 2005;60(5):410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano JP, Latorre JM, Gatz M, Montanes J. Life review therapy using autobiographical retrieval practice for older adults with depressive symptomatology. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19(2):272–277. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM, Lyubomirsky S. How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2006;1(2):73–82. doi: 10.1080/17439760500510676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol Y, Eisenheim E. The relationship between continuous identity disturbances, negative mood, and suicidal ideation. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 2016;18(1):26150. doi: 10.4088/PCC.15m01824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sztachańska J, Krejtz I, Nezlek JB. Using a gratitude intervention to improve the lives of women with breast cancer: A daily diary study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:1365. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE. Social support: A review. In: Friedman HS, editor. The Oxford handbook of health psychology. Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Teyber E, Teyber FH. Interpersonal process in therapy: An integrative model. Cengage Learning; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AL, Siegel JT. Elevation: A review of scholarship on a moral and other-praising emotion. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2017;12(6):628–638. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1269184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toepfer SM, Cichy K, Peters P. Letters of gratitude: Further evidence for author benefits. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2012;13(1):187–201. doi: 10.1007/s10902-011-9257-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez JPM, Datu JAD, Chu SKW. Gratitude intervention optimizes effective learning outcomes in Filipino high school students: A mixed-methods study. Computers & Education. 2022;176:104268. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh LC, Regan A, Lyubomirsky S. The role of actors, targets, and witnesses: Examining gratitude exchanges in a social context. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2022;17(2):233–249. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2021.1991449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, Cohen GL. A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science. 2011;331(6023):1447–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.1198364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, Wilson TD. Wise interventions: Psychological remedies for social and personal problems. Psychological Review. 2018;125(5):617–655. doi: 10.1037/rev0000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins PC. Gratitude and the good life: Toward a psychology of appreciation. Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins PC, Cruz L, Holben H, Kolts RL. Taking care of business? Grateful processing of unpleasant memories. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2008;3(2):87–99. doi: 10.1080/17439760701760567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, P. C., Munger, P., Hutton, B., Elliot, K., & Mathews, A. (2021). Modifying interpretation bias leads to congruent changes in gratitude. The Journal of Positive Psychology. Advance online publication, 1–11. 10.1080/17439760.2021.1940249

- Weinstein N, Ryan RM. When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98(2):222–244. doi: 10.1037/a0016984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Whisman MA. Relationship satisfaction instability and depression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(6):791–794. doi: 10.1037/a0021734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltschi B, Cernava T, Dennig A, Casas MG, Geier M, Gruber S, et al. Enzymes revolutionize the bioproduction of value-added compounds: From enzyme discovery to special applications. Biotechnology Advances. 2020;40:107520. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YJ, Gabana NT, Zounlome N, Goodrich N, Lucas M. Cognitive correlates of gratitude among prison inmates. Personality & Individual Differences. 2017;107:208–211. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YJ, McKean Blackwell N, Goodrich Mitts N, Gabana N, Li Y. Giving thanks together: A preliminary evaluation of the Gratitude Group Program. Practice Innovations. 2017;2:243–257. doi: 10.1037/pri0000058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YJ, Owen J, Gabana N, Brown J, McInnis S, Toth P, Gilman L. Does gratitude writing improve the mental health of psychotherapy clients? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research. 2018;28:192–202. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1169332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Froh JJ, Geraghty AW. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(7):890–905. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Maltby J, Gillett R, Linley PA, Joseph S. The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008;42(4):854–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood W, Neal DT. A new look at habits and the habit-goal interface. Psychological Review. 2007;114(4):843–863. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable