Introduction

Renal-limited lupus-like nephropathy is an entity characterized by pathologic features of lupus nephropathy, in the absence of clinical extrarenal signs and circulating markers specific for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).1, 2, 3, 4, 5,S1 The definition of “full-house” staining is based upon the detection of positivity for all 3 isotypes of immunoglobulins, together with C3, C4, and C1q on immunofluorescence with their relevant antisera.2,S2 The relationship of renal-limited lupus-like nephropathy with SLE is not fully clear; the kidney disease is often severe, and many cases evolve into full-blown SLE, so that some authors consider it a prodromal manifestation of SLE, whereas others suggest that this entity should be seen as self-standing.6,7 Membranous nephropathy is one of the most commonly found histologic types.6,7

The association between the activity of autoimmune diseases, of which SLE is the prototype, and pregnancy is complex; active diseases may also become quiescent owing to the immunosuppressive effect of pregnancy. Pregnancy is more often the trigger for flares, estimated to occur in 25% to 65% of the SLE cases.S3 Furthermore, pregnancy is the occasion for the diagnosis of different kinds of kidney diseases, often misinterpreted as preeclampsia.8,S3–S5

To the best of our knowledge, pregnancy has not been identified as a trigger for renal-limited lupus-like nephropathy. Here, we report on 7 cases diagnosed during pregnancy, suggesting that this finding may be more common than previously thought. We also propose 2 clinical associations that need testing in larger series (Table 1).

Table 1.

Teaching points

| Kidney diseases occurring or first diagnosed during pregnancy may present atypical clinical and histologic features. |

| “Full-house” immunofluorescence pattern is rare, outside the association with lupus nephritis. |

| The prognosis of “nonlupus” or “lupus-like” “full-house” glomerulonephritides needs to be elucidated. |

| In this series, 7 of 61 biopsies in pregnancy or after delivery found full-house membranous or membranoproliferative patterns, suggesting that frequency may be high in pregnancy. |

| Full-house membranous nephropathy was recorded in adolescent pregnancies in 3 of 4 cases, whereas 2 of 3 immune membranoproliferative glomerulonephritides were recorded in molar pregnancies. These associations should be tested in larger series. |

| Complete remission was achieved in 5 of 7 cases (4/4 membranous and 1/3 membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis) underlining, within the limit of the small series, the advantage of a proactive therapeutic attitude in kidney diseases discovered in pregnancy. |

Case Presentation

The main features of the 7 cases of kidney-limited lupus-like nephropathy, 4 with a full-house membranous pattern and 3 with a membranoproliferative pattern, are summarized in Table 2. They were observed over a 10-year period and encompass 7 of 62 kidney biopsies performed in pregnancy or shortly after delivery termination (3/31 in pregnancy and 4/31 after delivery or pregnancy termination) in the Instituto Nacional de Perinatologia, the only tertiary center in Mexico city dedicated to severe clinical problems in pregnancy. In all cases, at the time of diagnosis, and in all but one during follow-up, no systemic signs of SLE were present and specific serology was negative. Detailed patient data and further kidney biopsy images are available in the Supplementary Material.

Table 2.

Main clinical and kidney biopsy data

| Referral reasons and main functional data | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | Parity | Main reason for referral (wk) | sCr mg/dl at referral | PtUa g/d at referral | Kidney biopsy (wk of gestation, or wk post delivery termination) | sCr mg/dlat kidney biopsy | PtU g/d at kidney biopsy | Serum creatinine after delivery termination mg/dl (eGFR ml/min) | Last follow-up | Serum creatinine last follow-up (eGFR ml/min) | PtU g/d last follow-up | Delivery termination (wk) | Pregnancy outcome (birth weight centile)b | |

| Membranous full-house pattern | ||||||||||||||

| 1d | 23 | 2ndc | Proteinuria Anasarca (22) |

0.45 | 5.65 | Pregnancy (24) | 0.31 | 3.5 | 0.4 (136) | 8 yre | 0.4 (140) | 0.7 | 34f,g | Live birth (58) |

| 2d | 16 | 1st | Proteinuria Anasarca (26) |

0.31 | 8.0 | Pregnancy (27) | 0.42 | 3.8 | 0.3 (169) | 6 yr | 0.5 (143) | 0.5 | 38 | Live birth (3) |

| 3d | 14 | 1st | Proteinuria Anasarca (21) |

0.50 | 16.6 | Pregnancy (22) | 0.40 | 15.9 | 0.5 (143) | 1 yr | 0.55 (139) | 0.2 | 36g | Live birth (1) |

| 4d | 17 | 1st | Proteinuria Anasarca (30) |

0.70 | 3.2 | Puerperium | 0.50 | 0.5 | 0.5 (143) | 6 mo | 0.5 (141) | 0.03 | 38g | Live birth (7) |

| Membranoproliferative full-house pattern | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | 32 | 4th | Molar pregnancy Proteinuria (9) |

0.80 | 3.9 | After termination (4) | 0.60 | 4.0 | 0.7 (114) | 3 yr | 0.5 (130) | 0.11 g/l | 9 | Molar pregnancy |

| 6 | 31 | 1st | Proteinuria (27–30)h | 0.80 | 3.9 | After delivery (10) | 1.18 | 10.7 | 0.8 (98) | 1.5yr | 1.0 (74) | 4.5 | 32 | Live birth (36) |

| 7 | 26 | 4th | Molar pregnancy Proteinuria (8) |

1.07 | 4.6 | After termination (4) | 1.46 | 10.0 | 1.7 (41.2) | 1 yr | 2.4 (27) | 3.15 | 8 | Molar pregnancy |

| Morphologic findings and main treatments | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n. glom | IF (glomerular) positivity | PLA2R/EX | Other findings | Main treatments | Renal Outcome | |

| Membranous full-house pattern | ||||||

| 1d | 7 | Granular, global, and diffuse positivity for IgG, IgA, C1q, C3, kappa, and lambda, in glomerular basement membranes | (+)/(−) | Subepithelial deposits, and few mesangial deposits (EM), IgG and C3 positivity in tubular basement membrane (IF) Mesangial hypercellularity (LM) | Azathioprine, prednisone | SLE diagnosis after 7 yr |

| 2d | 13 | Granular, global, and diffuse positivity for IgG, C3c kappa, lambda; focal positivity for IgM, C1q, in glomerular basement membranes | Nd | Mild mesangial expansion | Azathioprine, prednisone | Complete remission |

| 3d | 12 | Granular, global, and diffuse positivity for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, C3, C4, kappa, and lambda in glomerular basement membranes. | (+)/(−) | Thickening of the glomerular basement membranes (LM) | Cyclophosphamide Methylprednisolone Prednisone |

Complete remission |

| 4d | 39 | Granular, global, and diffuse positivity for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, C3, C4, kappa, and lambda in glomerular basement membranes and scattered mesangial positivity | (+)/Nd | none | Tacrolimus Prednisone |

Complete remission |

| Membranoproliferative full-house pattern | ||||||

| 5 | 48 | Granular, global, and diffuse positivity for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, C3, C4, and kappa in glomerular basement membranes | Nd | Duplication of the glomerular basement membranes, intraluminal fibrin debris, erythrocyte fragmentation, cariorexis (LM). IgG, C1q, C3 deposits in tubular basement membranes (IF) vascular deposits (EM) |

Cyclophosphamide Methylprednisolone Prednisone |

Complete remission |

| 6 | 18 | Granular, global, and diffuse positivity for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, C3, C4, kappa, and lambda in glomerular basement membranes and mesangium | Nd | Double contour of the glomerular basement membranes, cell interposition, endothelial edema, cariorexis (LM) | Mycophenolate mofetil Prednisone |

Persistent proteinuria |

| 7 | 17 | Granular, global, and diffuse IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, C3, C4, kappa, and lambda in glomerular basement membranes and IgG, IgA, C3, C1q, and kappa in mesangium | Nd | Double contour of the glomerular BM. Cariorexis, cellular, and fibrocellular crescents (LM), IgG and C1q positivity in vascular walls (IF). | Cyclophosphamide Prednisone |

Renal impairment, proteinuria |

BM, basement membrane; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; EM, electron microscopy; EX, exostosin; IF, immunofluorescence; LM, light microscopy; Nd, not done; PE, pre-eclampsia; PtU, proteinuria; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Proteinuria was nonselective in all cases.

Intergrowth standards.

First pregnancy: age 18, preterm delivery of a small-for-gestational-age baby, no information on the kidney function.

Normotensive at referral. Cases 5 and 7: known hypertension.

Development of full-blown SLE. In all other cases, negative SLE serology and clinical picture.

Superimposed preeclampsia.

Cesarean section.

Referral to our hospital at 27 weeks and to nephrology at 30 weeks.

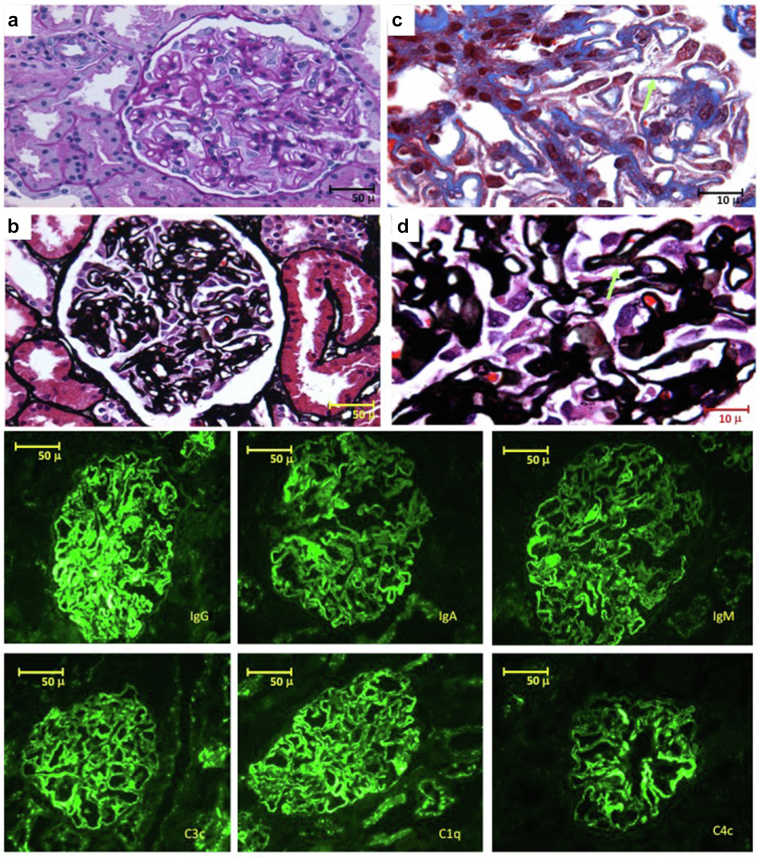

Case 1

A 23-year-old woman in her second pregnancy was referred at 22 gestational weeks owing to anasarca. She was normotensive, kidney function was normal (serum creatinine [sCr] 0.45 mg/dl), and proteinuria was 5.65 g/d, with very low serum albumin (1.0 g/dl). Urinary sediment showed rare red cell casts and dysmorphic erythrocytes. At 24 gestational weeks, a renal biopsy showed membranous nephropathy with full-house immunofluorescence staining (Figure 1). Staining was positive for phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R) and negative for exostosin. She was treated with methylprednisolone pulses and oral prednisone and azathioprine. Remission of proteinuria was achieved within 1 month. A cesarean section was performed at 34 gestational weeks because of the sudden development of hypertension and a small increase in proteinuria, and she delivered a female baby adequate for gestational age (47th percentile). Prednisone was tapered after delivery and azathioprine was continued for 1 year after delivery. Eight years later, SLE was diagnosed (arthritis, pericardial effusion, fever, and positivity for double-stranded DNA antibodies). Further details, including PLA2R and exostosin staining, are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 1.

Case 1: nonlupus full-house membranous nephropathy. (a,b) Photomicrographs (original magnification ×40) stained with Periodic Acid-Schiff (a) and Jones methenamine silver (b), showing homogeneous thickening of the glomerular basement membranes, with podocyte hypertrophy. (c,d) Photomicrographs (original magnification ×100) stained with Masson’s trichrome (c) and Jones methenamine silver (d); the arrows indicate subepithelial deposits (c) and filling defects (d) characteristic of membranous glomerulopathies. Bottom panels: (original magnification ×40) direct immunofluorescence staining with granular, global positivity in the glomerular basement membranes for all immunoglobulins and for complement, characteristic of the “full house” pattern.

Case 2

A 16-year-old female adolescent in her first pregnancy was referred at 26 gestational weeks owing to anasarca and heavy proteinuria (8 g/d), with normal kidney function (sCr 0.31 mg/dl). A kidney biopsy at 27 gestational weeks diagnosed membranous nephropathy with full-house immunofluorescence staining. Methylprednisolone pulses, oral prednisone, azathioprine, and hydroxychloroquine led to rapid remission. At 38 weeks, she delivered a small-for-gestational-age baby (2.5th percentile) in otherwise good condition. Azathioprine was given as maintenance therapy and was discontinued 1 year later. Full remission was maintained at last follow-up, 6 years later. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Case 3

A 14-year-old female adolescent in her first pregnancy was referred at 21 gestational weeks owing to anasarca. Blood pressure and kidney function were normal (sCr 0.5 mg/dl), proteinuria was 16.6 g/d, and serum albumin 0.9 g/dl. A kidney biopsy was performed at 22 gestational weeks, detecting membranous nephropathy with full-house immunofluorescence staining, further found to be positive for PLA2R and negative for exostosin. Because of logistic constraints (low-income, lack of availability of alternative long-term treatments), severity of the disease, and the relatively advanced pregnancy, she was treated with methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide pulses, followed by oral steroids, with rapid response. At 36 gestational weeks, she delivered, by cesarean section, a small-for-gestational-age (first percentile) otherwise healthy baby, without signs of cyclophosphamide-related embryopathy. A role of cyclophosphamide in growth restriction cannot be excluded. At the last follow-up, 1 year later, she was in complete remission, and the baby was in good health. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Case 4

A 17-year-old female adolescent in her first pregnancy was referred at 30 gestational weeks owing to anasarca. Kidney function (sCr 0.7 mg/dl) and blood pressure were normal; proteinuria was >10 g/d. She was treated with pulses of methylprednisolone and oral prednisone without response; the addition of tacrolimus allowed achieving prompt remission. At 38 gestational weeks, she delivered a small-for-gestational-age baby (eighth percentile) in good clinical condition. A kidney biopsy showed membranous nephropathy, with full-house pattern. PLA2R staining was positive. Tacrolimus was discontinued 2 months after the delivery. Remission lasted to the last follow-up, 6 months after delivery. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Case 5

A 32-year-old woman was referred for a molar pregnancy (fourth episode). Urinalysis showed proteinuria, with 500 mg/dl. The genetic study identified a homozygous mutation c.2248C>G (p.Leu750val) conferring a >90% risk of molar pregnancy. A kidney biopsy performed 1 month after surgical removal of the mole found membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with signs of thrombotic microangiopathy. Immunofluorescence test was positive for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, C3c, C4c, fibrinogen, and kappa light chains. She was treated according to the National Institutes of Health lupus protocol, including bolus methylprednisolone, oral steroids, and cyclophosphamide pulses, achieving complete remission in 4 months, which persisted at last follow-up, 3 years later. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Case 6

A 31-year-old woman in her first pregnancy was referred at 27 gestational weeks owing to anasarca. She had a history of poorly controlled diabetes, starting at the age of 24 years. Kidney function was normal (sCr 0.8 mg/dl), and proteinuria (3.9 g/d) was initially attributed to diabetes. At 32 gestational weeks, however, proteinuria increased to 7.2 g/d with microhematuria, hypertension, and renal function impairment. An adequate-for-gestational-age baby (36th percentile) was delivered by cesarean section. Ten weeks later, in the presence of increased sCr (1.18 mg/dl) and proteinuria (10.7 g/d) despite good diabetes control, a kidney biopsy was performed, which showed membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, superimposed on diabetic nephropathy, with immunofluorescence test positive for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, and C3. She received mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone and was lost to follow-up during the first lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eighteen months after the kidney biopsy, kidney function was normalized, and proteinuria was 4.47 g/d on mycophenolate and prednisone. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Material.

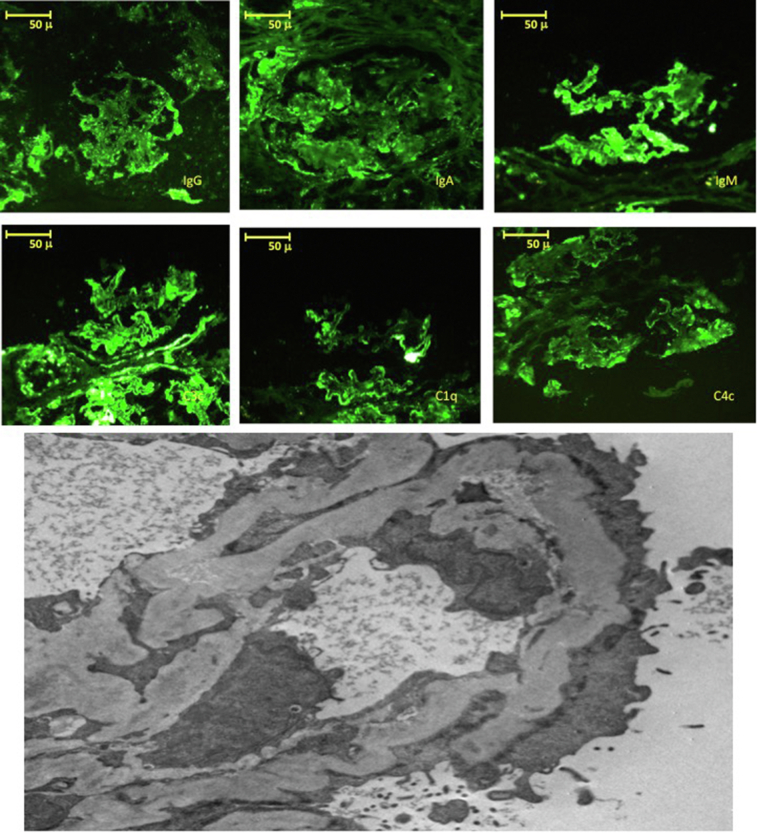

Case 7

A 26-year-old woman in her fourth pregnancy was referred for a molar pregnancy. At referral, proteinuria was 4.6 g/d, and kidney function was slightly impaired (sCr 1.07 mg/dl). The mole was complete and p57 negative. Four weeks after surgical removal of the mole, proteinuria increased to 10 g/d, and a renal biopsy was performed, which diagnosed membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with extra capillary proliferation (Figure 2). She received methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide pulses and oral steroids. At the last follow-up, 1 year later, her renal function was reduced (estimated glomerular filtration rate was 27 ml/min) with proteinuria (3.15 g/d). Further details are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 2.

Case 7. Top panels show direct immunofluorescence staining with granular positivity in the mesangium and in some segments of the capillary loops for all immunoglobulins and for complement, characteristic of the “full house” pattern. Bottom panel: electron microscopy (original magnification ×10,000) showing the presence of subendothelial and intramembranous electron dense deposits.

Discussion

Pregnancy is known to modulate kidney function, but its role in modulating immunologic kidney diseases is less well known. The association between renal-limited lupus-like glomerulonephritis and pregnancy has only previously been reported in a small number of cases.S6,S7

The 7 cases of renal-limited lupus-like glomerulonephritis that we report here represent a relatively high percentage of kidney biopsies performed in pregnancy or after delivery/pregnancy termination in a study setting in the past decade (7/62). Even considering a negative selection bias for referral, this suggests that these rare nephropathies may be more common in pregnancy than was previously thought.

Interestingly, 3 of our 4 cases of membranous nephropathy with a full-house pattern were adolescent pregnancies, and the fourth case had had a complicated first pregnancy at the age of 18 years, with delivery of a preterm, small-for-gestational-age baby, a situation that is often associated with an unacknowledged kidney disease in pregnancy.S8 Notably, this is in keeping with one of the largest series of nonlupus, full-house membranous nephropathy in which 12 of 20 cases were adolescents.9 Because the series is from Colombia, a genetic Latin American background may have played a role, given that only 2 cases were reported in adolescents in the largest case series available from China.S9 Membranous nephropathy with full-house staining has been associated with PLA2R-negative and exostosin-positive staining and a high risk of developing full-blown SLE, but the cases included in our analysis were negative for exostosin and positive for PLA2R.S10 Over a long follow-up (8 years), only 1 patient developed SLE, similar to another reported case who developed SLE 11 years after receiving a diagnosis of full-house membranous nephropathy in pregnancy.S7 Overall, the period of observation may have been too short to exclude this risk in our other cases.

The clustering of full-house membranous nephropathy in the second and third trimester of pregnancy might suggest a role for angiogenic-antiangiogenic factors because the hormonal milieu is altered at the start of pregnancy, whereas the angiogenic-antiangiogenic balance gains progressive importance throughout gestation.

Conversely, 2 of the 3 cases with lupus-like membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis were observed in molar pregnancy. Molar pregnancies have been associated with preeclampsia; hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets; and hyperemesis.S11 Complete molar pregnancies (cases 5 and 7) arise from villous trophoblast; their genetic material is of paternal origin. One case was a carrier of the homozygous mutation of the NLRP7 gene, c.2248C>G(p.Leu 750Val), found in approximately 60% of recurrent molar pregnancies in Mexico and associated with >90% risk of recurrence.S12 Interestingly, a recent review of placental site trophoblastic tumors associated with kidney involvement reported membranous and proliferative full-house pattern in 4 such cases.S13

Within the limitations of heterogeneous treatments, the choice for which was often dictated by logistic constraints, potentially leading to suboptimal choices, like in case 3 (treated by cyclophosphamide pulses, in the third trimester of pregnancyS14) and affected by the loss to follow-up of patients during the COVID-19 lockdown, the short-term prognosis was favorable in all cases with full-house membranous nephropathy, and only one of the cases with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis showed further kidney function impairment (case 7). Although dealing with a small series requires caution, this unusually good response is in line with what we reported in a small series of collapsing lesions in pregnancy, and although treatment suggestions cannot be drawn from a small number of cases, our findings support a proactive attitude in the treatment of severe or unusual forms of glomerular nephritis in pregnancy.S15

This series shares further limitations with clinical reports from medium-resourced settings, including the lack of systematic assessment of angiogenic-antiangiogenic biomarkers. Furthermore, PLA2R staining was available in only 3 of the 4 cases of membranous nephropathy, exostosin was available in 2 cases only, and serum antibodies against PLA2R were not available. These drawbacks may be partly balanced by the fact that the patients were treated by the same team, kidney biopsy was analyzed by the same pathologist, and information on follow-up was available.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this case series suggests that full-house, lupus-like glomerulonephritides may be triggered by pregnancy and suggests a possible association to be further confirmed with adolescent pregnancy for membranous lupus-like patterns and with molar pregnancy for membranoproliferative patterns. The unusually good response to treatment supports proactive management and indicates that further research should be conducted to better characterize the interplay between pregnancy and glomerular diseases. Given the high threshold to biopsy in pregnancy, it is possible that further similar cases are missed in clinical practice; higher awareness of these unusual cases responding well to treatment may improve diagnosis and outcomes.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Patient Consent

All patients provided signed informed consent for the anonymous publication of their data in the present report.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Susan Finnel for her careful language revision. Centre Hospitalier Le Mans supported professional editing and publication fees.

Footnotes

Extensive description of the cases.

Supplementary References.

Table S1. The main biochemical data in case 1.

Table S2. The main biochemical data in case 2.

Table S3. The main biochemical data in case 3.

Table S4. The main biochemical data in case 4.

Table S5. The main biochemical data in case 5.

Table S6. The main biochemical data in case 6.

Table S7. The main biochemical data in case 7.

Figure S1. Immunofluorescence staining for PLA2R and EXT1 in paraffin sections in case 1 and in case 3.

Figure S2. Case 2: light microscopy (×40).

Figure S3. Case 2: direct immunofluorescence staining (×40).

Figure S4. Case 3: light microscopy (×40).

Figure S5. Case 3: direct immunofluorescence staining (×40).

Figure S6. Case 3: electron microscopy (×800).

Figure S7. Case 4: light microscopy (×40).

Figure S8. Case 4: direct immunofluorescence staining (×40).

Figure S9. Case 4: immunohistochemistry for PLA2R (×40).

Figure S10. Case 5: light microscopy (×40).

Figure S11. Case 5: light microscopy: aspects of thrombotic microangiopathy (×40).

Figure S12. Case 5: direct immunofluorescence staining (×40).

Figure S13. Case 6: light microscopy (×40).

Figure S14. Case 6: direct immunofluorescence staining (×40).

Figure S15. Case 7: light microscopy showing crescents (×40).

Supplementary Material

Extensive description of the cases.

Supplementary References.

Tables S1. The main biochemical data in case 1.

Table S2. The main biochemical data in case 2.

Table S3. The main biochemical data in case 3.

Table S4. The main biochemical data in case 4.

Table S5. The main biochemical data in case 5.

Table S6. The main biochemical data in case 6.

Table S7. The main biochemical data in case 7.

Figure S1. Immunofluorescence staining for PLA2R and EXT1 in paraffin sections in case 1 and in case 3.

Figure S2. Case 2: light microscopy (×40).

Figure S3. Case 2: direct immunofluorescence staining (×40).

Figure S4. Case 3: light microscopy (×40).

Figure S5. Case 3: direct immunofluorescence staining (×40).

Figure S6. Case 3: electron microscopy (×800).

Figure S7. Case 4: light microscopy (×40).

Figure S8. Case 4: direct immunofluorescence staining (×40).

Figure S9. Case 4: immunohistochemistry for PLA2R (×40).

Figure S10. Case 5: light microscopy (×40).

Figure S11. Case 5: light microscopy: aspects of thrombotic microangiopathy (×40).

Figure S12. Case 5: direct immunofluorescence staining (×40).

Figure S13. Case 6: light microscopy (×40).

Figure S14. Case 6: direct immunofluorescence staining (×40).

Figure S15. Case 7: light microscopy showing crescents (×40).

References

- 1.Huerta A., Bomback A.S., Liakopoulos V., et al. Renal-limited ‘lupus-like’ nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2337–2342. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cameron J.S. Lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:413–424. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V102413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sam R., Joshi A., James S., et al. Lupus-like membranous nephropathy: is it lupus or not? Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19:395–402. doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-1002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Touzot M., Terrier C.S., Faguer S., et al. Proliferative lupus nephritis in the absence of overt systemic lupus erythematosus: a historical study of 12 adult patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang Z., Cai M., Dong B., et al. Clinicopathological features of atypical membranous nephropathy with unknown etiology in adult Chinese patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rijnink E.C., Teng Y.K., Kraaij T., et al. Idiopathic non-lupus full-house nephropathy is associated with poor renal outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:654–662. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stokes M.B., D’Agati V.D. Full-house glomerular deposits: beware the sheep in wolf’s clothing. Kidney Int. 2018;93:18–20. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan Y., Yang S., Liu Q., et al. Pregnancy-related complications in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2022;132 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2022.102864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muñoz Grajales C., Garnica E.R., Velásquez Méndez M.P., arias L.F. Nefropatía “full house” no lúpica, Aspectos Clínicos e Histológicos. Experiencia en dos Centros Hospitalarios de Medellín, Colombia. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2013;19:124–130. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.