Graphical abstract

Keywords: Lycopene, Metabolic pathway, Fermentation, Genetic engineering, Plants

Highlights

-

•

Lycopene is a natural red compound with potent antioxidant activity.

-

•

A breakthrough in increasing the yield of lycopene synthesis is needed.

-

•

Conventional fermentation enhanced the yield of lycopene by optimizing strains, additives, and culture conditions.

-

•

Nowadays, genetic engineering, protein engineering, and metabolic engineering have been applied to lycopene production.

-

•

Current lycopene production strategies can provide useful reference for metabolic engineering of lycopene production in plants.

Abstract

Background

Lycopene is a natural red compound with potent antioxidant activity that can be utilized both as pigment and as a raw material in functional food, and so possesses good commercial prospects. The biosynthetic pathway has already been documented, which provides the foundation for lycopene production using biotechnology.

Aim of review

Although lycopene production has begun to take shape, there is still an urgent need to alleviate the yield of lycopene. Progress in this area can provide useful reference for metabolic engineering of lycopene production utilizing multiple approaches.

Key scientific concepts of review

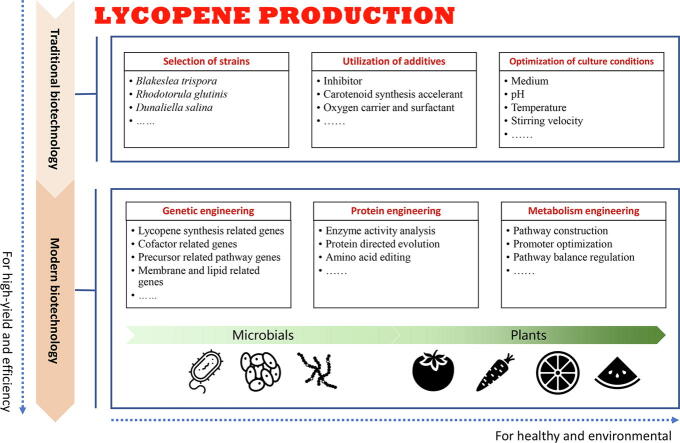

Using conventional microbial fermentation approaches, biotechnologists have enhanced the yield of lycopene by selecting suitable host strains, utilizing various additives, and optimizing culture conditions. With the development of modern biotechnology, genetic engineering, protein engineering, and metabolic engineering have been applied for lycopene production. Extraction from natural plants is the main way for lycopene production at present. Based on the molecular mechanism of lycopene accumulation, the production of lycopene by plant bioreactor through genetic engineering has a good prospect. Here we summarized common strategies for optimizing lycopene production engineering from a biotechnology perspective, which are mainly carried out by microbial cultivation. We reviewed the challenges and limitations of this approach, summarized the critical aspects, and provided suggestions with the aim of potential future breakthroughs for lycopene production in plants.

Introduction

Natural pigments are edible coloring matter extracted from natural resources such as plants, animals, and microorganisms. They are often useful as food coloring, but may also have physiological applications, including antioxidant, anti-cancer, health care and so on [1], [2]. Many natural pigments come from edible plants, therefore are generally safe for human consumption, a characteristic that is widely recognized and appreciated by consumers, and is one of the reasons the “Mediterranean Diet” is considered as one of most healthy diets [3]. Plant pigments consists of anthocyanins, carotenoids, flavonoids, and other bioactive substances, which offer health benefits and provide a range of different colors including yellow, orange, red, blue, and purple [4]. They are often added in small amounts in food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics to achieve a nice coloring effect [2]. The development and application of natural pigments is a hot topic for researchers in various industries [5]; but it has been demonstrated that the pigments in source materials often have low content coupled with the poor stabilities, and the separation and purification process are difficult to achieve [6]. Therefore, the substitution of artificial pigments by natural sources is difficult to proceed due to the above reasons [7].

As a natural carotenoid with strong antioxidant capacity found in plants, lycopene enjoys the reputation of being ‘plant gold’ [8]. Human body cannot make lycopene on its own, so it needs to be replenished from food. Eating food containing lycopene can improve human immunity, regulate blood lipids, and prevent cardiovascular diseases [9]. Researchers have demonstrated that lycopene has better antioxidant activity than other carotenoids, whose ranking is lycopene > α-carotene > β-cryptoxanthin > zeaxanthin = β-carotene > lutein [10], and consequently the commercial production of lycopene has suddenly heated up. In view of the potential applications of lycopene, research has been devoted to its production. Researchers have used various new techniques such as super critical fluid, enzyme-assisted, and ultrasound-assisted extraction, for extraction, purification, and processing technology to improve the lycopene’s yield, stability, and bioavailability [11].

As an antioxidant, lycopene was increasingly used in functional food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics at present [12]. Although it has long been permitted for use, the low yield of lycopene limited its commercial production. Molecular and biological engineering technology has become a viable solution for the targeted production of compounds beneficial to human health, as is the case of plant natural metabolites, health care products and bactericidin [13]. With the advance of biotechnology, numerous approaches such as metabolic engineering have been adopted to optimize the efficiency of lycopene synthesis [14]. Engineering the metabolic production of lycopene involves many aspects, including the selection of target genes [15], construction of the metabolic pathway [16], and the balance of metabolic flux [17]. Therefore, being motivated by the broad prospect of lycopene as an attractive target for metabolic engineering, this review discusses the advances in lycopene research, addressing its characteristics, distribution, biosynthesis pathway, and related advances facilitated by biotechnology, aiming to provide new prospects for the production of lycopene.

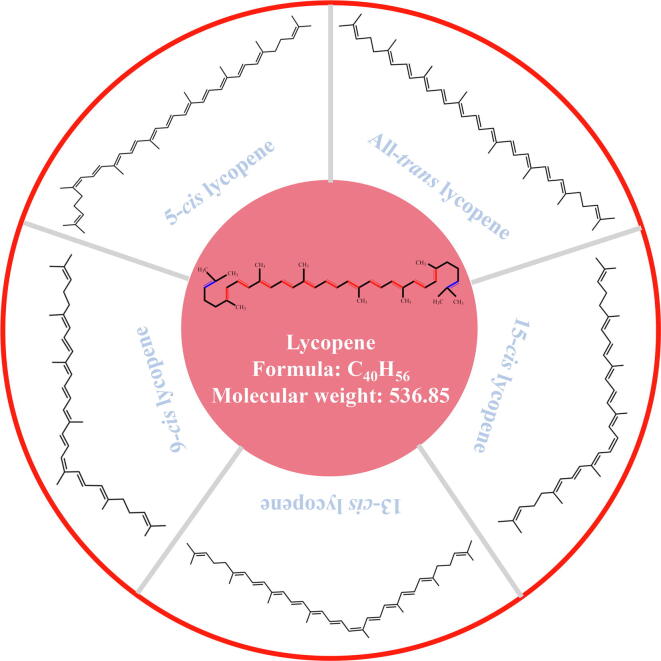

An overview of lycopene

Lycopene is a lipid-soluble natural pigment and an important member of the carotenoid family [18]. Chemically, lycopene (C40H56, Mw = 536.86) is an isoprene unsaturated olefin compound with 11 conjugated double bonds and 2 non-conjugated double bonds (Fig. 1). Among all carotenoids, lycopene holds the highest degree of unsaturation, mainly exists in trans configurations in nature, and it is easily oxidized, degraded, and isomerized [19]. As early as 1873, lycopene was isolated from the Tamus communis L. berries as a dark red crystal [20]. Further, Schunck [21] concluded that the absorption spectrum of this pigment differed from that of carotene, and eventually named it lycopene. According to research of Willstattler and Escher [22], lycopene is an isomer of carotene, containing 11 conjugated double bonds and 2 unconjugated C-C double bonds. Later, Kuhn and Gurndmann [23] proved that this structure belongs to non-cyclic plane multiple conjugate double bonds. Lycopene is prone to isomerization, it mainly exists in the form trans configuration in plants that contains lycopene, which is the most stable state. Through different degrees of molecular bending and twisting, the planar configuration is transformed into various cis-isomers [19]. There are four common cis-isomers of lycopene, 15-cis, 13-cis, 9-cis, and 5-cis lycopene, respectively (Fig. 1), among them 5-cis lycopene has the strongest antioxidant properties [24]. In terms of physical properties, lycopene is an aliphatic hydrocarbon, which imparts a red color, and a lipid-soluble pigment soluble in fats and nonpolar solvents. Lycopene can absorb visible light and has the highest absorption spectrum (λmax) at 472 nm [25].

Fig. 1.

General structure and main isomer configurations of lycopene. Red and blue color bonds in the structural formular in the central part represent conjugated double bonds and unconjugated double bonds, respectively.

In addition to the regulation of related enzymes in the lycopene synthesis pathway, lycopene accumulation can also be affected by the physical and chemical conditions, such as light, temperature, and other compounds. Red light treatment on tomato can promote the accumulation of lycopene in mature green fruits, and this effect will be reversed by far-red light [26]. Helyes et al. [27] found that high surface temperature caused by strong solar radiation reduced the lycopene content in vine ripened tomato fruit. Low growing temperature will reduce the content of lycopene in the pulp of pummelo (Citrus Maxima [Burm.] Merr.), which will lead to the pink pulp color to pale [28]. Both plant endogenous hormone content and exogenous hormone application can affect the accumulation of lycopene. An ABA-deficient mutant, high-pigment 3 (hp3) was identified as appearing increased plastid division and accumulating higher level of lycopene in the mature tomato fruit compared to wild-type [29]. Applying ABA can also increase the production of lycopene by fermentation of Blakeslea trispora [30].

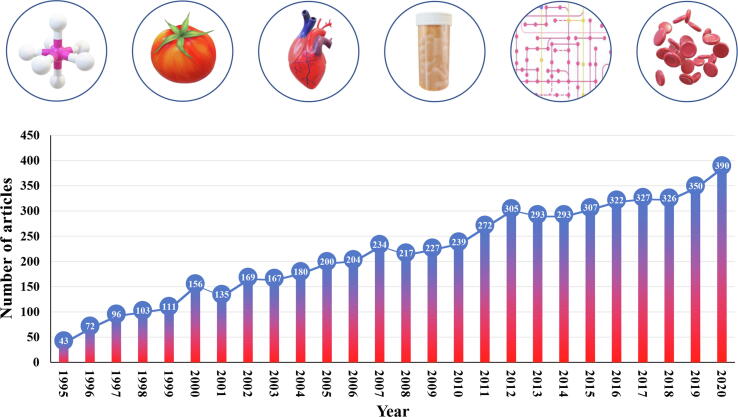

Lycopene has been considered as a key food component that contributes to human health [18]. It has a relatively higher physical quenching activity of singlet oxygen among all carotenoids [31]. Its oxidation potential is 100 times that of vitamin E and is more than twice that of carotene [32], [33]. Current studies on the biological functions of lycopene mainly focus on its antioxidant properties, which have potential for reducing cardiovascular disease, decreasing genetic damage, and inhibiting the occurrence and development of tumors [8], [34], [35], [36]. With the increasing recognition of lycopene’s health benefits, lycopene research has been heating up. Research related to physicochemical properties, biosynthesis, gene regulation, isolation and extraction, biological functions of lycopene has come to the fore [22], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [35]. In the decade from 1995, the number of lycopene related articles published rose from 43 to 200, and over the next 15 years, the number was doubled (Fig. 2). Even so, compared with other common natural pigments such as anthocyanins, carotenes, and chlorophyll (data from NCBI PubMed), studies on lycopene are still few and not deep enough. This can be attributed in part to the complexity of lycopene synthesis and its accumulation mechanism. Currently, lycopene remains a hot topic for researchers due to its powerful health benefits [12]. A breakthrough in understanding the regulatory mechanism of lycopene biosynthesis is needed to promote the massive production and application of this compound in the future.

Fig. 2.

Publication trends of lycopene in the last 25 years. Keyword ‘lycopene’ was used for searching in the ‘NCBI PubMed’ database.

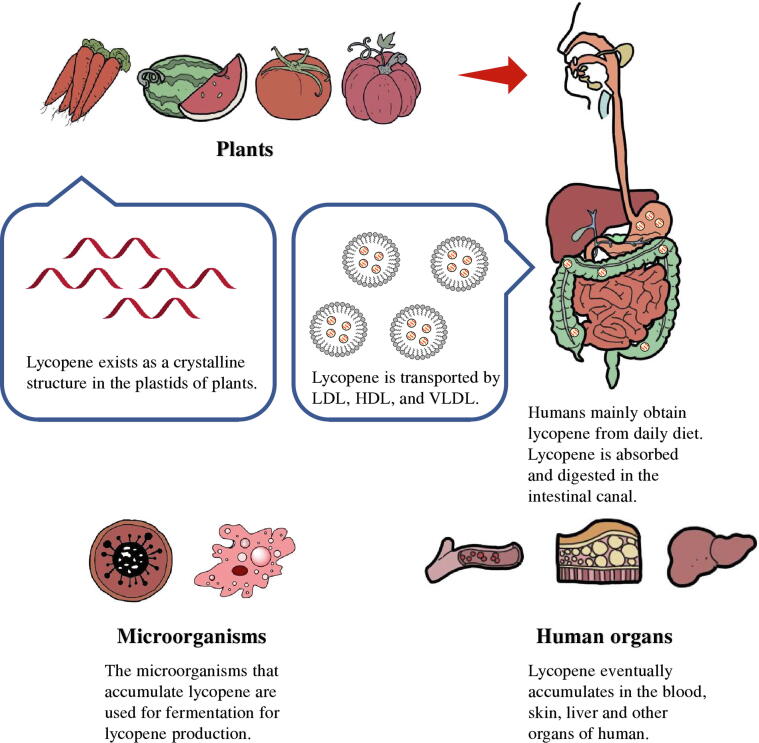

Distribution of lycopene in nature

Although tomatoes provide most of the lycopene in the human diet, lycopene can be found in numerous plant species and microorganisms as well. While animals including humans cannot synthesize lycopene, lycopene can be absorbed and distributed throughout different organs (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of lycopene in nature. LDL, low-density lipoproteins; HDL, high-density lipoproteins; VLDL, very-low-density lipoproteins.

In microorganisms

It has been demonstrated that lycopene can provide light protection for both photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic organisms [37], [38]. Studies have confirmed that lycopene can accumulate in microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, and algae, such as Cordyceps macleodganensis, Protomyces pachydermus, Protomyces inouyei, Phaffia rhodozyma, Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, and Streptomyces globisporus [39], [40], [41], [42]. The accumulation of lycopene in microorganisms can also result from mutations. For example, the inactivation of lycopene cyclase leads to the interruption of the carotenoid pathway, which contributes to the accumulation of lycopene in Blakeslea trispora [43]. Fermentation by microorganisms is one of the main primary methods to produce lycopene [14]. The Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) approves three sources of lycopene as food coloring agents: (a) tomato extraction, (b) Blakeslea trispora extraction, and (c) synthetic lycopene (INS No.: 160d) [44]. Under genetic engineering strategies, other microorganisms (e.g., Escherichia coli, Streptomyces avermitilis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Yarrowia lipolytica) can also serve as hosts for lycopene production [14]. In E. coli, 448 mg/g dry cell weight (DCW) lycopene can be obtained by combinatorial engineering approaches [45]. The highest lycopene content in S. cerevisiae could reach 73.3 mg/g DCW [46]. However, people have high requirements for its application in food, medicine, and cosmetics, so toxicity in microbial fermentation process caused by strain inhibitors or inducers, or extracting solvents should be avoided.

In plants

Lycopene is widely distributed in a variety of plants, mainly in mature fruits (Fig. 3, Table 1). Lycopene mainly accumulates in the chromoplast of cells and usually forms complexes with proteins. Different from other carotenoids, lycopene exists in the plastids as a crystalline structure (Fig. 3) [47]. In addition to the familiar tomato and watermelon, lycopene is also available in guavas, grapefruit, mango, papaya, and other plants [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59]. Scientists have also found numerous other plants that accumulate high levels of lycopene, such as autumn olive [48], rose hip [57] whose lycopene content can reach 540 and 352 µg/g fresh weight (Table 1). It’s worth noting that these lycopene accumulation species are not limited to specific families, but have a degree of diversity.

Table 1.

Lycopene content in some plants.

| Common name | Species | Family | Organ | Lycopene content (µg/g) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autumn olive | Elaeagnus umbellata | Burseraceae | Fruit | 150 ∼ 540 | [48] |

| Carrot | Daucus carota | Apiaceae | Root | 70 | [49] |

| Guavas | Psidium guajava | Myrtaceae | Fruit | 35.5 | [50] |

| Grapefruits | Citrus paradisi | Rutaceae | Fruit | 6.1 (pulp) 0.32 (flavedo) |

[51] |

| Mango | Mangifera indica | Anacardiaceae | Fruit | 0.53 | [52] |

| Papaya | Carica papaya | Rosaceae | Fruit | 14.4 ∼ 33.9 | [53], [54] |

| Persimmon | Diospyros kaki | Ebenaceae | Fruit | 270 | [55] |

| Pummelo | Citrus grandis | Rutaceae | Fruit | 5.83 | [56] |

| Rose hip | Rosa canina | Rosaceae | Fruit | 129 ∼ 352 | [57] |

| Tomato | Lycopersicon esculentum | Solanaceae | Fruit | 26.2 ∼ 6290 | [58] |

| Watermelon | Citrullus lanatus | Cucurbitaceae | Fruit | 36.5 ∼ 69.2 | [59] |

Note: In the above species, lycopene content was expressed as fresh weight except dry weight in persimmon.

It has been demonstrated that mutation and evolution of genes related to lycopene biosynthesis modify the accumulation pattern of different carotenoids in plants, leading to the continuous production of red mutant varieties in plants containing carotenoids, as is the case of watermelon [60], citrus [61] and papaya [62] (Table 1). The discovery of plants with high lycopene content serves as a material basis for the exploration of the accumulation mechanisms of lycopene. The storage organs for lycopene are not restricted to fruit, but also vegetative organs such as carrot roots [63]. Evidence suggests that the accumulation and biosynthesis of lycopene takes place in different organs. Previous studies evaluated the lycopene in distinct portions of tomato fruit: the skin, the water-insoluble fractions, fiber, and soluble solids. Interestingly, lycopene is found in higher concentrations and different chemical configurations in the peel [64]. In plants, lycopene can also convert to four cis-isomer configurations (15-cis, 13-cis, 9-cis, and 5-cis lycopene) in addition to the dominant all-trans form [19]. Ranveer et al. [65] found that the outer part of the tomato pericarp contained more chromoplasts. This suggests that the peel and seeds of tomato, which have traditionally been discarded as production waste in many cases, could be a potential good source of lycopene [66]. Our study in carrot demonstrated that the accumulation of lycopene in carrot taproot exhibited a tissue specific trend. In certain varieties, lycopene accumulates in the pericarp and phloem of carrots which leads to red color; nevertheless, the xylem is yellow [63]. Since lycopene only accumulates in certain species, and most of these species are horticultural crops that lack established stable genetic transformation systems, lycopene production using plants as bioreactors was hindered. To sum up, the production of lycopene is relatively complex compared to other carotenoids and involves many factors, cannot be represented as a simple genetic pathway.

In human

Lycopene is the most abundant carotenoid in the human body, accounting for about 50% of the total carotenoid content [67]. It is widely disseminated in various organs and tissues of the human body, mainly including blood, adrenal glands, testicles, and liver (Fig. 3). Generally, the content of lycopene in the serum is used to represent nutritional status of human lycopene [68]. Under normal conditions, the concentration of lycopene in human serum is in the range of 0.2 ∼ 1.0 µmol/L, accounting for 6.35% of total lycopene content [69]. It was noted that the lycopene in plants is mainly in the trans configuration, while the proportion of cis-isomer of lycopene in human body is higher [68]. cis-isomer lycopene has stronger bioavailability and can be digested and absorbed more easily [70]. After the human body obtains lycopene from plants, lycopene enters the intestinal tract in packages of oil droplets, when are then transformed into mixed micelles [71]. Through digestion and absorption, the lycopene-containing chylomicrons produced by enzyme cleavage are circulated in the blood or are transported to various body organs via lipoproteins [72] (Fig. 3).

Biochemistry of the lycopene biosynthesis pathway

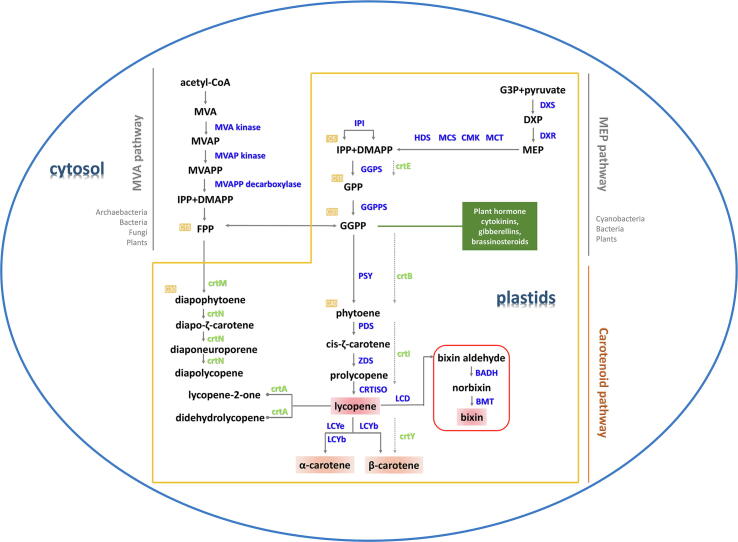

Lycopene is the linear C40 backbone of cyclic carotenoid synthesis. Lycopene biosynthesis is a part of carotenoid metabolism. The synthetic pathway of carotenoids has been known since the 1950 s (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Carotenoid biosynthesis via the MVA or MEP pathway. The yellow line shows reactions occurring in plastids. Compounds in the pathway are represented by black letters. Names of plant enzymes are in blue, those of bacterial are in green. Numbers in the yellow boxes represent carbon shelf structures. The green box shows the plant hormones used GGPP as precursors. The red box displays the biosynthesis of lycopene derivative bixin.

Synthesis of the precursor geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP)

Carotenoids are terpenoids composed of isoprene skeletons. The immediate precursor of carotenoids is geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP). GGPP results from the condensation of two C5 isoprene units, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP). The synthesis of IPP and DMAPP depends on two pathways: mevalonate (MVA) pathway in cytosol and 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway in plastid (Fig. 4) [73], [74]. The MVA pathway produces IPP with the glycolysis product acetyl-CoA as raw material with the help of MVA kinase. In higher plants, lycopene precursors are usually synthesized by the MVA-independent pathway (i.e., MEP pathway) in plastids [73]. With pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-P (G3P) as substrates, the first step of the MEP pathway is to generate 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) under the catalysis of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase (DXS). DXP reductoisomerase (DXR) is the second rate-limiting enzyme in the MEP pathway, and is responsible for converting DXP to MEP, further forming IPP and DMAPP. The conversion between IPP and DMAPP is completed by IPP isomerase (IPI). GGPP is finally yielded by the condensation of IPP and DMAPP catalyzed by GGPP synthase (GGPS, crtE) via C10 molecule geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) and C15 molecule farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) (Fig. 4). In addition to carotenoids, the MEP or MVA pathway also provides substrates for a diverse range of other metabolites, including multiple plant hormones (cytokinins, gibberellins and brassinosteroids), terpenoids (diterpenoids, monoterpenoids and sesquiterpenoids), also chlorophyll [75], [76], [77], [78].

Formation of phytoene, desaturation and isomerization

Under the catalysis of phytoene synthase (PSY, crtB), two molecules of GGPP are condensed to form the first C40 carotenoid phytoene [79]. Over the years, many studies on the regulation of lycopene synthesis revolved around PSY. It is not only a key rate-limiting enzyme in the pathway, but also an important integrator of diverse signaling pathways regulating lycopene accumulation [80].

Phytoene is colorless and requires desaturation catalyzed by phytoene desaturase (PDS) and ζ-carotene desaturase (ZDS) to form colored carotenoids. Phytoene takes at least four steps of desaturation to generate all-trans-lycopene. Each step requires the involvement of FAD and plastoquinone, and eventually loses two hydrogen atoms [81], [82]. In microorganisms, a single enzyme carotene desaturase (crtI) is responsible for the whole desaturation and isomerization processes. A similar enzyme carotenoid isomerase (CRTISO) which can isomerize the 7,9 and 7′,9′ positions of tetra-cis lycopene to yield all-trans lycopene has evolved in higher plants (Fig. 4). There is another isomerase called 15-cis-ζ-carotene isomerase (Z-ISO) in plants and some algae [83], [84], [85], [86].

Conversion from lycopene to carotene

Lycopene is the branch point of carotenoid synthesis. Lycopene is catalyzed into carotenes with ring structures by the action of two cyclases, lycopene-β-cyclase (LCYb) and lycopene-ε-cyclase (LCYe). These two cyclases can cyclize one or both ends of linear lycopene to form α-carotene or β-carotene (Fig. 4). This process can realize the conversion of carotenoid from red color to orange, which makes lycopene cyclase the cause of color differences in some plants, such as watermelon, kiwifruit and papaya [60], [87], [88].

In some species, FPP can synthesize diapolycopene of C30 structure under the catalysis of crtM and crtN [89]. Lycopene can also be catalyzed to other derivatives, such as lycopene-2-one, didehydrolycopene and bixin (Fig. 4) [90], [91], [92], [93], [94].

Advances in lycopene production from the perspective of biotechnology

Based on microbial and plant cell factories, biotechnology provides a method for the directed construction of secondary metabolite production with the support of molecular biology, cell biology, microbiology, and other disciplines. Both traditional and modern biotechnology have made significant contributions to guiding lycopene production.

Application of traditional biotechnology to lycopene production: Microbial fermentation

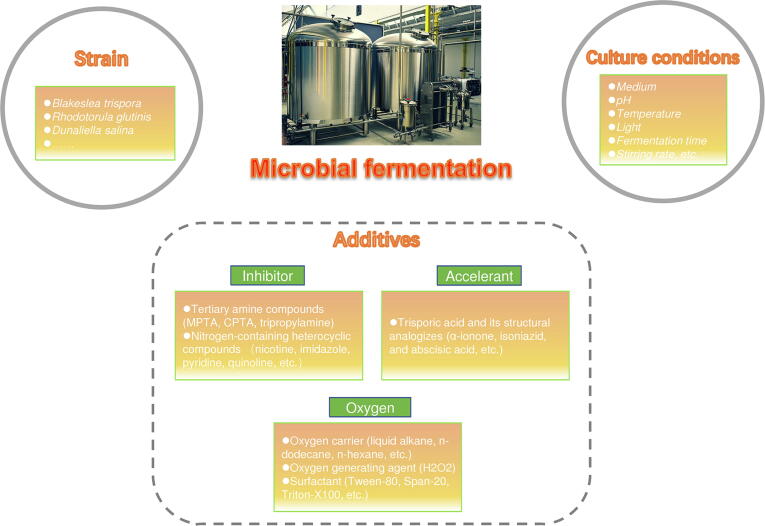

Traditional biotechnology dates back thousands of years, when people used workshop methods to process beer, bread, soy sauce and vinegar [95], [96], [97]. Pasteur firstly proved that fermentation was caused by microorganisms [98]. Subsequently, humans began to consciously use yeast and other microorganisms for large-scale fermentation production. Microorganisms that can produce lycopene include gram-negative bacteria, fungi, and algae. People extracted lycopene from these microbes by fermentation, the measures taken to improve the yield of lycopene started with optimizing the fermentation process (Table 2) [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108]. Based on strain selecting, together with the application of suitable additives (inhibitor, accelerant, and oxygen) and the optimization of suitable culture conditions (medium, pH, temperature, and light), the yield of lycopene produced by fermentation was continuously improved (Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Lycopene production by microbial fermentation.

| Category | Species | Strain | Strategy | Lycopene production/content | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Dietzia natronolimnaea | HS-1 | Utilization of lycopene cyclase inhibitors: | [99] | |

| imidazole, | 1.94 ∼ 6.57 mg/L | ||||

| nicotinic acid, | 1.89 ∼ 8.11 mg/L | ||||

| piperidine, | 0.98 ∼ 6.81 mg/L | ||||

| pyridine, | 1.44 ∼ 7.91 mg/L | ||||

| triethylamine, | 1.01 ∼ 6.97 mg/L | ||||

| control | 0.423 mg/L | ||||

| Fungi | Blakeslea trispora | NRRL2456 (+); NRRL2457 (-) | Chemical mutagenesis: | [43] | |

| N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine, | 27 ∼ 220 µg/g | ||||

| control | 16 ∼ 21 µg/g | ||||

| Blakeslea trispora | SB34; SB40 | Utilization of lycopene cyclase inhibitor: nicotine; Utilization of accelerant: β-ionone |

10.3 mg/g | [100] | |

| Blakeslea trispora | ATCC14271 (+); ATCC14272 (-) |

Utilization of ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors: | [101] | ||

| terbinafine hydrochloride, | 128.8 ∼ 182.4 mg/L | ||||

| ketoconazole, | 78.4 ∼ 358.1 mg/L | ||||

| control | 97.4 ∼ 153.4 mg/L | ||||

| Blakeslea trispora | NRRL2895 (+); NRRL2896 (-) |

Utilization of lycopene cyclase inhibitors: | [102] | ||

| imidazole, | 14.58 ∼ 115.15 mg/L | ||||

| piperonyl butoxide, | 25.26 ∼ 57.40 mg/L | ||||

| piperidine, | 54.28 ∼ 269.66 mg/L | ||||

| triethylamine, | 25.97 ∼ 198.27 mg/L | ||||

| pyridine, | 80.78 ∼ 198.07 mg/L | ||||

| creatinine, | 18.69 ∼ 116.33 mg/L | ||||

| nicotinic acid, | 32.57 ∼ 103.95 mg/L | ||||

| control | 34.74 mg/L | ||||

| Blakeslea trispora | NRRL2895 (+); NRRL2896 (-) |

Utilization of accelerants: abscisic acid, leucine, and penicillin | 270.3 mg/L | [103] | |

| Blakeslea trispora | NRRL2895 (+); NRRL2896 (-) |

Physical mutagenesis: atmospheric and room temperature plasma |

26.4 mg/g | [104] | |

| Rhodotorula |

R. glutinis; R. rubra |

Utilization of lycopene cyclase inhibitor: nicotine | Almost 35 ∼ 95 µg/g | [105] | |

| Rhodotorula glutinis | YB-252 | Utilization of lycopene cyclase inhibitor: imidazole | 6.82 mg/L | [106] | |

| Algae | Dunaliella salina | CCAP19/18 | Utilization of lycopene cyclase inhibitor: nicotine | 0.24 ∼ 0.41 mg/L | [107] |

| Haematococcus pluvialis | SAG 19-a | Utilization of lycopene cyclase inhibitor: (-)-nicotine | 0.61 mg/g | [108] |

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram of lycopene microbial fermentation production.

Selection of strains

Production of lycopene in microbes often requires the selection of certain strains. An important advantage is the ability to synthesize carotenoids, thus the accumulation of lycopene can be achieved by inactivating lycopene cyclase, blocking the downstream pathway of carotenoid synthesis. The main strains producing natural lycopene are Blakeslea trispora and Rhodotorula (Fig. 5) [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106]. B. trispora is a kind of filamentous fungi with strong ability to produce β-carotene that features rapid growth and high biomass production. B. trispora includes two parthenogenetic strains, B. trispora (+) and B. trispora (-), both of which have the ability of independent asexual reproduction to form sporangium and sporophyte spores. B. trispora (-) mycelium has strong reproduction and carotenoid production abilities, while B. trispora (+) is adept in germinating spores [109]. The trisporic acid produced by co-culture of B. trispora (+) and B. trispora (-) can promote the synthesis of lycopene [110]. Various attempts have been carried out to increase the production of lycopene in B. trispora with the addition of inhibitors [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [111] (Table 2). Rhodotorula can synthesize ergosterol, which shares a common precursor with lycopene. Lycopene accumulation can be carried out by controlling the metabolic flux. By contrast, the pigment production level of Rhodotorula is lower than that of B. trispora, but its simple nutritional requirements and short cultural cycle can make it better for comprehensive utilization. More importantly, the high-density liquid fermentation process is suitable to industrialize [105], [106].

Before the emergence of genetic engineering, the selection of strains was limited to mutagenesis breeding. In 1995, Mehta & Cerdá-Olmedo isolated red B. trispora which was different from the orange-yellow wild type by N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (NTG) mutagenesis, and this phenotype was caused by a block of lycopene cyclase [43]. Although it is difficult to find positive mutation effects and the characters are unstable, mutagenesis is still used to obtain high-yield lycopene stains today, and more mutagenesis methods and strains have been pursued [15], [40], [112], [113].

Utilization of additives

Inhibitor

One key step of microbial lycopene production is to add lycopene cyclase inhibitors to block the cyclization reaction from lycopene to carotenes, so that the metabolic flux is directed towards lycopene. Primary structure examination by Bouvier et al. [114] showed that the cyclization of lycopene requires the formation of a transient carbon cation, and lycopene cyclase inhibitors with protic aryl or carboxyl groups can prevent the cyclization process. There are two types of common lycopene cyclase inhibitors, (a) tertiary amine compounds, including 2-(4-methylphenoxyl) triethylamine (MPTA), 2-(4-chlorophenylthio) ethylamine hydrochloride (CPTA), tripropylamine; (b) nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds, such as nicotine, imidazole, pyridine, quinoline, and some substituted derivatives [115], [116], [117], [118] (Table 2). The results of the study in D. natronolimnaea showed that the lycopene production was increased by 2.3 ∼ 19.2 times (0.423 to 0.98 ∼ 8.11 mg/L) using different lycopene cyclase inhibitors [99] (Table 2). Ergosterol inhibitors are also used in the production of lycopene. The first step of the ergosterol synthesis is the formation of MVA. The product of MVA pathway, IPP and DMAPP, are precursors of carotenoid synthesis in microorganisms (Fig. 4). Common ergosterol inhibitors include terbinafine hydrochloride (TH) and ketoconazole [101], [119]. The yield of lycopene reached 182.4 and 358.1 mg/L by adding TH and ketoconazole in B. trispora fermentation [101] (Table 2).

Carotenoid synthesis accelerant

Dandekar et al. [120] found that trisporic acid and its structural analogizes can promote the synthesis of lycopene by B. trispora. These compounds have a ring structure with one ketone group and a short side chain structure (e.g., α-ionone, isoniazid, and abscisic acid) [121], [30]. Desai and Modi’s study [122] concluded that the addition of penicillin after 24 h of fermentation can boost the isoprene metabolic pathway, increasing the precursor substance for lycopene synthesis. Direct addition of the precursor β-ionone also promotes metabolic flow to the carotenoid pathway, as does isoniazid [30], [123]. Other studies have shown that related compounds in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, such as malate, α-ketoglutarate, and fumarate, can increase the production of β-carotene but inhibit the production of lycopene, which indicates that it may also enhance the cyclization reaction of lycopene while regulating flux [121].

Oxygen carrier and surfactant

During the process of production, the oxygen dissolution rate of the fermentation system is low, which will result in the decline of production capacity. The addition of an oxygen carrier can significantly improve the oxygen transfer coefficient of the reaction system, and the effect can be enhanced by surfactants [124]. There are two main measures to increase dissolved oxygen: (a) one is to add oxygen carrier, which is insoluble with water, non-toxic to microorganisms, and has a high ability to dissolve oxygen, such as liquid alkane, n-dodecane, n-hexane [124]; (b) another is to produce oxygen chemically in the aqueous phase, e.g., adding H2O2 to the fermentation broth [125]. The addition of surfactants such as Tween-80, Span-20, and Triton-X100 can regulate the fluid properties of fermentation liquid, change the permeability of cells, facilitate substance transfer, and create a ventilation effect [126].

Optimization of culture conditions

Optimization of culture conditions is the most basic method to promote the growth of microbial and increase yield (Fig. 5). The basic medium used in lycopene production is yeast malt (YM) medium which is composed of yeast powder, maltose, and peptone, providing carbon and nitrogen sources [111]. Inorganic salt (e.g., sulfates and phosphates) is also added to the culture medium to promote enzyme activity [102]. With the promotion of biomass materials, corn starch, soybean meal, and other feedstock are also applied to lycopene fermentation engineering [127]. The fermentation yield can be affected by culture conditions. Lopez-Nieto et al. [128] demonstrated that the initial pH of fermentation liquid was 7.5 which is conducive to the accumulation of lycopene in B. trispora, but with the influence of microbial metabolism on the pH during the fermentation process, the pH should be adjusted accordingly to maintain the metabolic flow. Temperature was confirmed to affect the growth and development of organisms, meanwhile control the enzymes concentration [129]. Zhou et al. [130] compared the effect of temperature on lycopene production in E. coli, the results showed that two stage temperature control strategy (0 ∼ 9 h 33 °C, after 9 h 28 °C) was more conducive to increase production (605.25 µg/L). Light can promote lycopene production, mainly due to the benefits to microbial and related enzyme activity [121]. The optimization of additional factors such as fermentation time and stirring rate can also improve the yield of lycopene. Studies in B. trispora demonstrated that lycopene production continued to increase as the agitation rate elevating from 150 to 300 rpm, and it was associated with the fermentation cycle [128].

Application of modern biotechnology to lycopene production

Modern biotechnology is based on molecular biology, which organically applies engineering technology on biological systems. According to the pre-design, biological genetic traits or processing materials are directional transformed, further creating new biological types or new biological functions [131]. Compared with traditional biotechnology, modern biotechnology has made great leaps in terms of the research objectives, research level and engineering principles [132]. Traditional biotechnology is limited to microbial fermentation and chemical engineering, and is unable to change the genetic material of microorganisms, let alone create new hereditary traits, so cannot bring high efficiency and yield. With the discovery of the DNA double helix and the birth of recombinant DNA technology, the phase of modern biotechnology began [133].

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering is the operation of introducing foreign genes into recipient cells after recombination in vitro so that they can be duplicated, transcribed, translated, and expressed in the recipient cells [134]. Gene recombination can control the reassembly of genes with different traits, resulting in a large number of variants [135]. Candidate genes for enhancing lycopene production by genetic engineering usually include those related to the lycopene synthesis pathway, cofactor production, competitive pathways, and membrane- and lipid- production [111].

Lycopene synthesis related genes

Direct homologous recombination of genes encoding the catalytic enzyme lycopene synthase can increase lycopene production [15]. The bifunctional gene carRA encodes both phytoene synthase and lycopene cyclase in B. trispora. The lycopene content improved from 0.47 to 1.40 mg/g DCW in carR-knockout strains, as well as in carA overexpressing strains [136]. The Rhodobacter sphaeroides lycopene-producing strain was obtained by introducing crtI4 from Rhodospirillum rubrm and deleting crtC [137]. Adjusting the copy number of key genes is also an effective strategy, in this way, Shi et al. [138] obtained a lycopene yield of 3.28 g/L in S. cerevisiae. The utilization of regulatory genes as targets can also enhance the production of lycopene. In R. sphaeroides, the yield of lycopene was increased ∼ 6.5 fold (3.32 to 21.45 mg/g DCW) by deleting the photosynthetic gene cluster repressor ppsR and overexpression of the activator prrA [139].

Cofactor related genes

Synthesis of lycopene precursors requires cofactors (i.e., ATP and NADPH) to provide sufficient energy. Based on E. coli mutant screeding, ATP synthase related genes were identified as candidate genes involved in the early isoprenoid biosynthesis of lycopene formation [140]. By modulating susAB, sdhABCD and talB, three genes within central metabolic modules, the supplies of ATP and NADPH increased, leading to higher lycopene production. The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) can produce vast amounts of NADPH [141]. Knockout of the zwf gene encoding glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase by one-step inactivation in E. coli increased the lycopene content by 30% compared to control (5.39 to 7.55 mg/g DCW). Transcript analysis showed that the carbon flux was shifted from PPP to glycolytic pathway [142]. Promoting NADPH production has now become a frequently-used method in metabolic engineering [143], [144]. In S. cerevisiae, a gene POS5 encoding NADH kinase were overexpressed to increase the lycopene yield (258 mg/L) [145]. Hong et al. [143] overexpressed a NADPH related gene STB5 in lycopene-producing S. cerevisiae strains and finally obtained a yield of 41.8 mg/g DCW.

Precursor related pathway genes

In lycopene production, regulation of genes in precursor related pathways also affects lycopene accumulation, including the pathways that provide or compete for precursors. Stable production requires sufficient precursors and a continuous metabolic flow. For lycopene production, it is necessary not only to promote the synthesis of MEP/MVA pathway product IPP, but also to ensure adequate supply of acetyl-CoA or pyruvate. By co-expressing exogenous MEP pathway genes dxs and idi in E. coli, the transcription of downstream isoprenoid pathway genes was promoted, and the yield of lycopene was increased by 16.5 times (20.57 mg/L) [146]. In S. cerevisiae cell factories for lycopene production, overexpression of the rate-limiting enzyme genes of the MVA pathway, tHMG1, BTS-ERG20 and SaGGPS, increased the yield to 2, 16.9, and 20.5 times, respectively. When the 3 genes were overexpressed together, the yield reached to 77 times (0.17 to 13.23 mg/L) [147]. To provide a better supply of the precursors G3P and pyruvate, Jung [148] tuned the expression of ppsA and gapA, which resulted in down-regulation of gapA and a 97% increase in lycopene content. Similarly, a sufficient supply of acetyl-CoA was achieved by overexpression of ADH2 and ALD6 which promoted ethanol production from acetyl-CoA, and inhibition of CIT2 and MLS1 blocked acetyl-CoA consumption by other reactions [149]. Inhibition of other metabolic pathway with competing precursors can also induce more metabolic flux into the lycopene pathway. Hong et al. [143] inhibited the farnesol pathway by deleting DPP1 and LPP1, inhibited ergosterol production of by downregulation of ERG9, and also deleted ROX1 and MOT3 which repressed mevalonate and sterol biosynthesis, to finally obtain high lycopene yield mutant strains.

Membrane and lipid related genes

Lycopene is a fat-soluble pigment that tends to form aggregates in cells when it accumulates in high levels. It has been demonstrated that increasing the permeability and surface area of the cell membrane will bring higher carrying capacity for lycopene. Wu et al. [150] increased lycopene production by overexpressing membrane bending related gene Almgs and membrane synthesis related genes, plsb, plsc, and dgka, which confirmed the feasibility of membrane engineering strategy in lycopene production. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) can affect the permeability of the outer membrane of E. coli. One study using a set of deletion mutants of E. coli waa locus indicated that mutants with shorter LPS produced higher lycopene yields [151].

Increasing the content of unsaturated fatty acids in cell membranes is beneficial to the flexibility of cell membranes, also contributes to the storage of lycopene [152]. Y. lipolytica is a yeast with greasy properties which can form liposomes. Overexpression of AMPD together with multiple copies of crt genes and a series of key central metabolic genes significantly enhanced lycopene production in Y. lipolytica [153]. Ma et al. [46] modulated lipid oil-triacylglycerol (TAG) metabolism through overexpression of OLE1 and FLD1 that regulate lipid droplet size, to produce lycopene yields of 56.2 mg/g cell DCW in S. cerevisiae.

Protein engineering

Protein engineering is considered as ‘the second generation of genetic engineering’, which is not limited to the recombination of natural genes but can also redesign and transform the genes encoding natural protein according to people’s needs [154]. It is an effective strategy to increase the yield of lycopene by using protein engineering to improve the activity of catalytic enzymes. A recent study found that the introduction of Vibrio sp. dhg Dxs and IspA could lead to significantly higher lycopene production than the endogenous enzymes in E. coli, Vibrio sp. dhg derived enzymes has higher catalytic efficiencies [155]. Research carried out on tomato PSY1 identified two key amino acid residues, Asn-136 and Gly-198 are essential for phytoene synthase activity [156]. Targeted evolutionary strategies have also been used in S. cerevisiae to modify proteins to promote lycopene production. With the help of error-prone PCR, directed evolution of CrtE led to a 2.2-fold increment of lycopene production (24.41 mg/g DCW) [157]. It has been demonstrated that a 25% increase in lycopene production (final production 128 mg/L) was obtained using E. coli mutant through the amino acid mutation of the global regulator cAMP receptor protein (CRP) [158]. The advent of CRISPR/Cas9 technology has made it easier to engineer proteins. Using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated markerless integration, HMG1, CrtI, MVD1, EGR8, CrtB, and CrtE were overexpressed in Y. lipolytica which led to significant enhancement in lycopene titer [159]. Similarly, integrating the idi gene of the MVA pathway into E. coli increased lycopene production by 2.28 times [160]. Such protein engineering pushes bioengineering research to a new stage and opens up new prospects for lycopene production.

Metabolic engineering

Metabolic engineering (pathway engineering) increases the production of specific metabolites by the systematic analysis of cellular metabolic networks and the design and genetic modification of the metabolic pathway and is considered ‘the third generation of genetic engineering’. With the rapid development of synthetic biology in the 21st century, scientists have performed the artificial design and construction of regulatory metabolic pathways through the reasonable assembly of various components, such as insulin [161], artemisinin [162], starch [163]. To achieve better target compound production, several approaches need to be optimized and many techniques need to be applied comprehensively [164]. Here we introduce the progress of common strategies in metabolic engineering for lycopene production.

Pathway construction

Metabolic engineering can lead to lycopene accumulation in new species through the introduction of lycopene pathway enzymes. The production of lycopene in non-lycopene producing strains (e.g., E. coli and S. cerevisiae) can be conducted by introducing 3 genes, crtE, crtB and crtI [126], [143], [165]. The copy number of crt genes in the construction can influence the metabolic flux. Zhang et al. [153] constructed 6 combinations of strains with different copy numbers of crt genes and found that appropriate adjustment of copy numbers of crtE, crtB and crtI can result in enhanced lycopene synthesis in Y. lipolytica. The same conclusion was also drawn based on work in S. cerevisiae [138].

For increasing the metabolic flow of precursors, some studies have also supplemented the precursor pathways (MEP and MVA pathways). The supplementation of MVA pathway modules consisting of mvak1, mvak2, mvaD and idi provided precursors IPP and DMAPP, which increased lycopene production by more than three folds (17 mg/L) [126]. Wei et al. [16] optimized the expression of the MVA upper pathway, MVA lower pathway, and lycopene synthesis pathway based on a multiple plasmid system and chromosomal multiple position integration strategy, and finally achieved a maximum yield of 224 mg/L. Recent research constructed a new isopentenol utilization pathway (IUP) by inserting IPK and CHK in Y. lipolytica that produces higher levels of IPP and DMAPP than the MVA pathway. Combined with further fermentation optimizations, a final output of 4.2 g/L of lycopene was obtained [166].

Promoter optimization

Efficient expression of heterologous genes requires an appropriate promoter and related expression elements. Researchers controlled the MVA pathway through promoters of different strengths (1Ptac, 2Ptac, 3Ptac, 4Ptac, and 5Ptac) and increased the production of lycopene [167]. In order to precisely control gene expression, a promoter modularization regulatory element was created which introduced RiboJ to eliminate the interference between the promoter and ribosome binding sites, enabling lycopene production in Streptomyces [168]. Lv et al. [169] utilized three promoters of different strengths, pT7, pTrc, and pAra, to regulate the balance of the MEP and isoprene-forming pathways, and succeeded in increasing isoprene production by 4.7 folds. Study has also shown that compared with inducible promoters, constitutive promoters can control gene expression persistently and are more suitable for balancing the lycopene synthesis pathway [170].

Pathway balance regulation

Due to the introduction of multiple genes and metabolic pathways, regulation of the stability of the entire complex pathway is an important task in metabolic engineering, otherwise metabolite production will be limited by reduced metabolic activity and growth retardation. Farmer and Liao [171] designed a dynamic controller glnAP2 and applied it to the lycopene pathway to control idi and pps to successfully avoid growth inhibition. This demonstrated that the dynamic control allowed the expression of key enzymes for lycopene biosynthesis to be coordinated with the metabolic state of the cell. At present, a flux balance analysis (FBA) method has been established as a simulation tool for quantitative analysis of metabolic networks. It can determine the optimal reaction flux distribution based on stoichiometry, and one study confirmed that FBA can be utilized to improve lycopene production in Y. lipolytica [17]. Kang et al. [172] chose a pair of short peptide tags (RIAD and RIDD) to control the flux of metabolites. Idi-CrtE assembly tagged with RIAD or RIDD effectively increased the lycopene production in S. cerevisiae, the yield reached 2.3 g/L.

Application of biotechnology to lycopene production in plants

Status of lycopene production in plants

Extraction of natural pigments from plants is the most preferred method for lycopene production. Researchers have made great efforts on developing economical and efficient extraction methods. Using conventional extraction method, 35 mg/kg lycopene can be obtained from tomato peel [173]. Higher level of lycopene content can be obtained from watermelon [174]. Assisted by microwave, lycopene extracted from watermelon could reach 1.602 mg/g [175]. The yield of lycopene extracted from cherry tomato by ultrasound assisted method was 168.2 mg/g [176]. A new method supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) led to 93.7 mg/kg lycopene production using tomato industry waste as materials [11]. The above methods can only reduce the loss of lycopene during the extraction process, for higher lycopene yield, plant materials with high lycopene content are essential and basic. The most striking advantage of genetic engineering is that it breaks down boundaries between species that are hard to break through with conventional breeding. With the help of stable transient expression systems and plant tissue culture, DNA encoding high-value proteins can be introduced into cells in vitro, and gene transfer can be realized after culture and reproduction [177]. Compared with microorganisms, plants are more environmentally friendly, and can avoid the byproduct metabolites and toxicity produced in the production process of microorganisms. Avoiding the complex and long process of fermentation, lycopene in plants can be extracted and purified directly. Therefore, it has great prospect to develop lycopene production by biotechnology.

Mechanism of lycopene accumulation in plants

Understanding the molecular mechanism of lycopene accumulation in plants will provide reference for the application of biotechnology. The genes involved in lycopene synthesis in plants have undergone a complex evolution and are regulated by a complex network. The present research progress conducive to lycopene production in plants mainly focuses on the following aspects: (a) functional identification of potential genes; (b) establishment of genetic transformation system for target species; (c) optimization of gene editing system (e.g., RNAi and CRISPR/Cas9); (d) preliminary mining of regulation network (Table 3). Modern biotechnology strategies have been gradually applied to plants for high lycopene production. Introduction of crtW and crtZ from marine bacteria in tomato led to over production of lycopene (∼3.5 mg/g DW) [187]. By manipulation of MVA and MEP pathway using hmgr1 and gxs genes, several isoprenoids content in tomato has been promoted including lycopene [188]. The same effect was later achieved with the introduction of Brassica juncea BjHMGS1 gene in tomato [189]. Enfissi et al. [190] found that components of the light signal transduction pathway DE-ETIOLATED1 could affect plastid biogenesis, further influence the lycopene accumulation in tomato. By co-expressing the genes crtB, HpBHY, CrBKT, and SlLCYB in the fruit of yellowish tomato ‘Huang Song’, the lycopene content in transgenic tomatoes increased, and ketocarotenoids including astaxanthin, canthaxanthin, and ketolutein were found to accumulate in large quantities [191]. Overexpression of blue light photoreceptors CRY1a also enhanced the content of lycopene in tomato fruit [192]. Although the factors regulating lycopene in plants involve more aspects, they can provide more options for target genes used in genetic engineering. Moreover, codon optimization, regulatory gene introduction, tissue specificity and other factors need to be taken into consideration.

Table 3.

Research on lycopene accumulation mechanism in plants.

| Species | Method | Conclusion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) |

Expression analysis; RNAi; Transgenesis. |

Accumulation of lycopene in fruit of autumn olive is associated with the expression pattern of EutPSY and the silencing of EuLcy-e. | [178] |

| Carrot (Daucus carota) |

Expression analysis. | Carrot cultivars with lycopene accumulation in fleshy roots have lower LCYE gene expression compared to universal orange carrots. | [63] |

| Orange (Citrus sinensis) |

Cloning; Expression analysis; Norther and southern blot hybridization. |

Accumulation of lycopene in red citrus was associated with the reduction in the expression of b-LCY2 and b-CHX. Different alleles of b-LCY2 displayed altered enzyme activity. | [51] |

| Iris (Iris germanica) |

Expression analysis; Suspension culture. |

Ectopic expression of a bacterial crtB leads to the accumulation of lycopene, which caused color changes of iris ovaries, flower stalks and anthers. | [179] |

| Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) |

Enzymes assays; Expression analysis; Immunoprecipitation; Western blot. |

Phytoene synthase was located in the plastid stroma. The transcription of Psy and Pds is regulated developmentally. Psy and Pds was expressed in breaker and ripe fruit, also flowers, but hardly in green fruits. | [180] |

| Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) |

Expression analysis; Heterologous expression. |

During the ripening stage of tomato fruit, with the accumulation of lycopene, the expression of LCY-ε and LCY-β genes were gradually down-regulated until disappeared. | [181] |

| Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) |

Cloning; Expression analysis; Heterologous expression; RFLP mapping. |

The expression of CrtL-e showed significantly decrease at the ‘breaker’ stage of ripening of wile type tomato. In the Delta mutant, it increased around 30-fold and resulted in the transform from lycopene to δ-carotene. | [182] |

| Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) |

Antisense expression; Transgenesis. |

Down-regulating the expression of β-Lcy by antisense construct in a fruit-specific fashion led to a slight increase in lycopene content. | [183] |

| Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) |

Genomic DNA sequencing; SNP analysis. |

Yellow flesh color in tomato is due to a nucleotide mutation in the PSY gene. Lycopene content was quantitatively inherited. | [184] |

| Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) |

Expression analysis; RNAi; Transgenesis. |

After silencing LCY-ε and LCY-β by RNAi, lycopene content in tomato plant had significantly increased. | [185] |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) |

Expression analysis; Interaction analysis; Transgenesis. |

SlSGR1 which encodes a STAY-GREEN protein can regulate lycopene accumulation through inhibit the activity of SlPSY1. | [186] |

| Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) |

Enzyme assay; Map-based cloning; RACE and RT-qPCR; Transgenesis; Western-blot analysis. |

Two missense mutations led to three haplotypes with red, white, or yellow pulp among 211 watermelon accessions. This difference is primarily caused by influencing the protein abundance of ClLCYB protein. | [60] |

Notes: Lcy-e/LCYE/LCY-ε/CrtL-e, genes encoding lycopene ε-cyclase; b-LCY2/LCY-β/β-Lcy/LCYB, genes encoding lycopene β-cyclase; Pds, gene encoding phytoene desaturase; PSY/crtB/Psy, genes encoding phytoene synthase; SGR1, gene encoding STAY-GREEN protein.

Lycopene production based on plant bioreactor

Plant bioreactor refers to a method of producing secondary metabolites with high economic value, such as medical proteins, enzymes and special carbohydrates, using common plants as chemical factories through genetic engineering. At present, there are precedents for the use of genetically modified plants and plant cells in the commercial production of biological products [177], [193], [194], [195]. Shaaltie et al. [193] produced alpha-galactosidase-A (PRX-101), an enzyme for the therapy of Fabry disease, in the tobacco cell culture. Carrot cell culture was also used for the production of PRX-102 and PRX-105 [195]. Through introducing provitamin A (β-carotene) biosynthetic pathway in rice endosperm, ‘golden rice’ was obtained and contribute to Vitamin A deficiency [196]. In Arabidopsis, human intrinsic factor was produced to defeat Vitamin B12 deficiency [197]. Carrot is a kind of plant with strong differentiation ability and regeneration efficiency, and contains various kinds of carotenoids, which is the model plant of carotenoid research [198], [199]. Currently, some studies have focused on carrot carotenoids, and red root carrots contains a large amount of lycopene, which promotes the possibility of using carrots as bioreactors to produce lycopene [200], [201]. As clinical data continue to be enriched and regulatory framework improved, plant bioreactor production owns leading commercial potential. Although the production of lycopene using plant bioreactors is not widely available, this method could be considered and may lead to a leap.

Conclusions and perspectives

Lycopene is recognized as an important natural pigment and a potent antioxidant with anti-cardio-cerebrovascular disease and anti-cancer properties. Having said that, the low content, unstable chemical properties, and low bioavailability has kept it from reaching its full potential as a nutraceutical. Further efforts are needed to overcome drawbacks in the extraction and processing technologies. More importantly, further exploration of the lycopene accumulation mechanism can fundamentally address the matter of increasing lycopene yields. One strategy is to focus on species that accumulate high levels of lycopene. Achievement in this area will not only address the issue of low lycopene production but can also allow the production of lycopene in non-lycopene producing species. In this context, strategic exploration of lycopene synthesis mechanism using molecular biological techniques represents a novel approach. Existing studies have demonstrated the key role of biotechnology in driving lycopene production and application. However, we are still faced with many challenges and limitations due to the unique characteristic of lycopene.

The following lists the perspectives and research directions for consideration by research community in the future:

-

(a)

The accumulation of lycopene in nature is limited, not only due to its presence in a limited number of species, but also because it is accumulated in very small amounts. Germplasm accumulating high levels of lycopene needs to be created.

-

(b)

The stability of lycopene in its natural form is one of the main factors limiting the yield of lycopene, which can be affected by various factors, such as the configuration, physical conditions, chemical conditions and so on. Therefore, appropriate optimization of the culture and extracting conditions is necessary to maintain the yield and stability of lycopene.

-

(c)

Identifying and isolating transcription factors relevant to lycopene production and accumulation and characterizing their regulatory mechanisms is a challenging but necessary task. The expression of structural genes in the lycopene synthesis pathway is controlled by a complex regulatory network, and understanding the role of these key transcription factors should be considered as a fundamental goal.

-

(d)

Lycopene is an intermediate substance in carotenoid metabolic flow. Balancing the flux of the entire metabolic flow to avoid feedback inhibition is a key factor affecting productivity.

-

(e)

Synthetic biology and metabolic engineering provide an excellent technical platform to produce numerous metabolites, including lycopene. The selection of target genes, the construction of genetic transformation systems, the utilization of efficient promoters, codon optimization, the supplementation of coenzyme factors and other measures need to be pondered in the metabolic engineering construction. Research on this aspect is expected to become a hot spot in the future.

-

(f)

One key to lycopene accumulation is the blocking of lycopene cyclase. The increasing maturity of gene silencing (i.e., RNAi, VIGS) and gene/genome editing (i.e., CRISPR/Cas9) technologies provides further option for the creation of lycopene in more species.

-

(g)

The storage capacity of lycopene constitutes one of the factors limiting the efficiency of its production. Membrane and lipid engineering strategies need to be developed and introduced to address this issue.

-

(h)

The potential of multi-omics analysis in identifying novel players associated with lycopene production and regulation under normal and stress conditions should be focused on.

In general, the production of lycopene does face various challenges. At the same time, the difficulties provide us with corresponding research directions. With the continuous development and improvement of biotechnology, our understanding of all aspects of lycopene production will advance, as will the application of biotechnology in lycopene production.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ya-Hui Wang: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft. Rong-Rong Zhang: Data curation, Formal analysis. Yue Yin: Data curation, Formal analysis. Guo-Fei Tan: Data curation, Formal analysis. Guang-Long Wang: Data curation, Formal analysis. Hui Liu: Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Jing Zhuang: Investigation, Resources, Methodology. Jian Zhang: Investigation, Resources, Methodology. Fei-Yun Zhuang: Investigation, Resources, Methodology. Ai-Sheng Xiong: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for the helpful comments on the manuscript.

Funding

This article was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31872098; 32072563), Key Research and Development Projects of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (No.2022BBF02008); Key Research and Development Project of Jiangsu (BE2022388); Jilin Agricultural University high level researcher grant (JAUHLRG20102006); Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX21_0607), and Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions Project (PAPD).

Biographies

Ya-Hui Wang is currently a PhD student at State Key Laboratory of Crop Genetics and Germplasm Enhancement, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China. Her research project focuses on the molecular mechanism of lycopene accumulation and synthesis regulation in carrot.

Rong-Rong Zhang obtained her Master degree majoring in in vegetable science from Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China in 2021. Currently, she continues to pursue her PhD at NJAU. Her research project focuses on the molecular mechanism of carotenoid response to stress in carrot.

YueYin worked as a research associate at Ningxia Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences, Yinchuan, China. Currently, he continues to pursue his PhD at Northwest A&F University. His research project focuses on the molecular mechanism of carotenoid metabolism in wolfberry.

Guo-Fei Tan, PhD. He works as an associate researcher at Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Guiyang, China. He has expertise in collection and creation of vegetable germplasm resources. His current research project focuses on the Apiaceae vegetables (mainly celery and carrot), including resource collection, identification and molecular mechanism research.

Guang-Long Wang has earned his PhD in Vegetable Science from Nanjing Agricultural University. Then, he worked as an associate professor at the School of Life Science and Food Engineering, Huaiyin Institute of Technology, Huaian, China. His research focus is on the physiology and molecular biology of vegetable quality.

Hui Liu obtained her phD from college of horticulture, Nanjing Agricultural University. Currently she serves as a postdoctor in the State Key Laboratory of Crop Genetics and Germplasm Enhancement, Nanjing Agricultural University. Her current research focuses on th omics research related to vegetable key quality traits.

Jing Zhuang, PhD. She serves as a doctoral supervisor and professor at College of Horticulture, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China. She mainly focuses on the collection, preservation, evaluation and utilization of tea germplasm resources, as well as the reseach on stress resistant molecular biology and secondary metabolism of tea.

Jian Zhang, PhD. He joint the Alberta Research Council and started his long-term adventures in applied genomis, genetic engineering, improving food safety, environmental related studies, functional food, smart africulture and new material research. In 2020, he joint Jilin Agricultural University as a professor in the area of Smart Agriculture and plant genomics and phenomics research.

Fei-Yun Zhuang, PhD. He serves as a deputy researcher at Institute of Vegetable and Flower, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China. He mainly engaged in the genetic research of important agronomic traits and breeding of new varieties of carrot.

Ai-Sheng Xiong, PhD. He serves as a professor of National Key Discipline of Vegetable Science and State Key Laboratory of Crop Genetics and Germplasm Enhancement, Nanjing Agricultural University. He mainly engaged in the research on genetic and germplasm innovation of Apiaceae vegetable crops.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Boo H., Hwang S., Bae C., Park S., Heo B., Gorinstein S. Extraction and characterization of some natural plant pigments. Ind Crops Prod. 2012;40:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Y. Tanaka, A Ohmiya., Seeing is believing: engineering anthocyanin and carotenoid biosynthetic pathways, Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008, 19(2):190-197. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Figueroa C., Echeverria G., Villarreal G., Martinez X., Ferreccio C., Rigotti A. Introducing plant-based mediterranean diet as a lifestyle medicine approach in Latin America: Opportunities within the chilean context. Front Nutr. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.680452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miao S., Wang P., Xu Y., Sun J., Li C., Li L. Review on development and utilization of natural edible pigments from plant sources. Food Res Develop. 2012;33(7):211–216. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortez R., Luna-Vital D.A., Margulis D., de Mejia E.G. Natural pigments: stabilization methods of anthocyanins for food applications. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2017;16(1):180–198. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giuliani A., Cerretani L., Cichelli A. Colors: properties and determination of natural pigments. Encyclopedia of Food and Health. 2016:273–283. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schweiggert R.M. Perspective on the ongoing replacement of artificial and animal-based dyes with alternative natural pigments in foods and beverages. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(12):3074–3081. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b05930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng J., Miller B., Balbuena E., Eroglu A. Lycopene protects against smoking-induced lung cancer by inducing base excision repair. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9(7):643. doi: 10.3390/antiox9070643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pataro G., Carullo D., Falcone M., Ferrari G. Recovery of lycopene from industrially derived tomato processing by-products by pulsed electric fields-assisted extraction. Innovative Food Sci Emerging Technol. 2020;63 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stahl W., Junghans A., de Boer B., Driomina E.S., Briviba K., Sies H. Carotenoid mixtures protect multilamellar liposomes against oxidative damage: synergistic effects of lycopene and lutein. FEBS Lett. 1998;427(2):305–308. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00434-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waqas A., Anam L., Zhang L., Zhang J., Wang C., Abdur R., et al. Technological advancement in the processing of lycopene: A review. Food Rev Int. 2022;62(4):1003–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prathibha G., Yadav V. Lycopene: a plant pigment with prominent role on human health. Int J Curr Res. 2015;6(6):7006–7010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasotti L., Zucca S. Advances and computational tools towards predictable design in biological engineering. Comput Math Methods Med. 2014;2014:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2014/369681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M.J., Xia Q.Q., Zhang H.B., Zhang R.B., Yang Y.M. Metabolic engineering of different microbial hosts for lycopene production. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(48):14104–14122. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velayos A., Eslava A.P., Iturriaga E.A. A bifunctional enzyme with lycopene cyclase and phytoene synthase activities is encoded by the carRP gene of Mucor circinelloides. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267(17):5509–5519. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei Y., Mohsin A., Hong Q., Guo M., Fang H. Enhanced production of biosynthesized lycopene via heterogenous MVA pathway based on chromosomal multiple position integration strategy plus plasmid systems in Escherichia coli. Bioresour Technol. 2018;250:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nambou K., Jian X., Zhang X., Wei L., Lou J., Madzak C., et al. Flux balance analysis inspired bioprocess upgrading for lycopene production by a metabolically engineered strain of Yarrowia lipolytica. Metabolites. 2015;5(4):794–813. doi: 10.3390/metabo5040794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stahl W., Sies H. Lycopene: a biologically important carotenoid for humans? Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;336(1):1–9. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong L., Elshareif O., Cheng Y., Sun Q., Zhang L. Rapid isomerization and storage stability of lycopene. Acta Hortic. 2015;1081:323–330. [Google Scholar]

- 20.M.L. Bianchi, G. Franceschi, M.P. Marnati, C. Spalla, Microbiological process for the production of lycopene.[WWW document] URL https://www.freepatentsonline.com/3467579.html [accessed 15 Dec 2021].

- 21.Schunck A. The xanthophyll group of yellowcoloring matters. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1903;72:165–176. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willstatter R., Escher H.H.Z. Lycopene extracted from tomato Physiol Chem. 1910;76:214–225. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhn R., Grundmann C. Die konstitution des lycopins. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1932;65(11):1880–1889. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honest K.N., Zhang H.W., Zhang L. Lycopene: Isomerization effects on bioavailability and bioactivity properties. Food Rev Int. 2011;27(3):248–258. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzouganaki Z.D., Atta-Politou J., Koupparis M.A. Development and validation of liquid chromatographic method for the determination of lycopene in plasma. Anal Chim Acta. 2002;467(1–2):115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alba R., Cordonnier-Pratt M., Pratt L.H. Fruit-localized phytochromes regulate lycopene accumulation independently of ethylene production in tomato. Plant Physiol. 2000;123(1):363–370. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.1.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helyes L., Lugasi A., Pek Z. Effect of natural light on surface temperature and lycopene content of vine ripened tomato fruit. Can J Plant Sci. 2007;87(4):927–929. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buaban P., Beckles D.M., Mongkolporn O., Luengwilai K., K. Lycopene accumulation in pummelo (Citrus Maxima [Burm.] Merr.) is influenced by growing temperature. Inter J Fruit Sci. 2020;20(2):149–163. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galpaz N., Wang Q., Menda N., Zamir D., Hirschberg J. Abscisic acid deficiency in the tomato mutant high-pigment 3 leading to increased plastid number and higher fruit lycopene content. Plant J. 2008;53(5):717–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu J., Xu F., Yuan Q. Effect of abscisic acid related compounds on lycopene production by Blakeslea trispora. Journal of Bjing University of Chemical Technology (Natural ence Edition) 2007;34(2):134–137. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Mascio P., Kaiser S., Sies H. Lycopene as the most efficient biological carotenoid singlet oxygen quencher. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;274(2):532–538. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90467-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao A.V., Shen H.L. Effect of low dose lycopene intake on lycopene bioavailability and oxidative stress. Nutr Res. 2002;22(10):1125–1131. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torregrosa-Crespo J., Montero Z., Fuentes J., Reig García-Galbis M., Garbayo I., Vílchez C., et al. Exploring the valuable carotenoids for the large-scale production by marine microorganisms. Mar Drugs. 2018;16(6):203. doi: 10.3390/md16060203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCormack T., Dent R., Blagden M. Very low LDL-C levels may safely provide additional clinical cardiovascular benefit: the evidence to date. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2016;70(11):886–897. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palozza P., Catalano A., Simone R., Cittadini A. Lycopene as a guardian of redox signalling. Acta Biochim Pol. 2012;59(1):21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao Y., Xin Z., Li N., Chang S., Chen Y., Geng L., et al. Nano-liposomes of lycopene reduces ischemic brain damage in rodents by regulating iron metabolism. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;124:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armstrong G.A. Eubacteria show their true colors: genetics of carotenoid pigment biosynthesis from microbes to plants. J Bacteriol. 1994;176(16):4795–4802. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.4795-4802.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chattopadhyay M.K., Jagannadham M.V., Vairamani M., Shivaji S. Carotenoid pigments of an antarctic psychrotrophic bacterium Micrococcus roseus: temperature dependent biosynthesis, structure, and interaction with synthetic membranes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239(1):85–90. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrewes A.G., Phaff H.J., Starr M.P. Carotenoids of Phaffia rhodozyma, a red-pigmented fermenting yeast. Phytochemistry. 1976;15(6):1003–1007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holembiovs'ka S.L., Matseliukh B.P. Production of carotene and lycopene by mutants of Streptomyces globisporus 1912 cultivated on mealy media. Mikrobiol Z. 2008;70(4):45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma S.K., Gautam N., Atri N.S., Dhancholia S. Taxonomical establishment and compositional studies of a new Cordyceps (Ascomycetes) species from the northwest Himalayas (India) Int J Med Mushrooms. 2016;18(12):1121–1130. doi: 10.1615/IntJMedMushrooms.v18.i12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valadon L.R.G. Carotenoid pigments of some lower Ascomycetes. J Exp Bot. 1964;15(2):219–224. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehta B.J., Cerdá-Olmedo E. Mutants of carotene production in Blakeslea trispora. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;42(6):836–838. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Codex General Standard for Food Additives (GSFA) Online Database [Internet]. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization; c1995- [cited 2022 April]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/dbs/gsfa/en/.

- 45.Coussement P., Bauwens D., Maertens J., De Mey M. Direct combinatorial pathway optimization. ACS Synth Biol. 2017;6(2):224–232. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma T., Shi B., Ye Z., Li X., Liu M., Chen Y., et al. Lipid engineering combined with systematic metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for high-yield production of lycopene. Metab Eng. 2019;52:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang X., Liu S., Gao P., Liu H., Wang X., Luan F., et al. Expression of ClPAP and ClPSY1 in watermelon correlates with chromoplast differentiation, carotenoid accumulation, and flesh color formation. Sci Hortic. 2020;270 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fordham I.M., Clevidence B.A., Wiley E.R., Zimmerman R.H. Fruit of autumn olive: a rich source of lycopene. HortScience. 2001;36(6):1136–1137. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clotault J., Peltier D., Berruyer R., Thomas M., Briard M., Geoffriau E. Expression of carotenoid biosynthesis genes during carrot root development. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:3563–3573. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ordóñez-Santos L., Vázquez-Riascos A. Effect of processing and storage time on the vitamin C and lycopene contents of nectar of pink guava (Psidium guajava L.) Arch Latinoam Nutr. 2010;60(3):280–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alquezar B., Zacarias L., Rodrigo M.J. Molecular and functional characterization of a novel chromoplast-specific lycopene beta-cyclase from Citrus and its relation to lycopene accumulation. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:1783–1797. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D.M. Muli, Quantification of β-carotene, lycopene and β-cryptoxanthin in different varieties and stages of ripening of mangoes grown in Mwala, Machakos county. 2013; PhD thesis, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya.

- 53.de Souza L.M., Ferreira K.S., Chaves J.B.P., Teixeira S.L. L-ascorbic acid, beta-carotene and lycopene content in papaya fruits (Carica papaya) with or without physiological skin freckles. Sci Agric. 2008;65(3):246–250. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanupriya S.M., Jayanth K.S., Shivashankara C. Vasugi, Biochemical properties of yellow and red pulped papaya and its validation by molecular markers. Indian J Hortic. 2016;73(3):315–318. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qi Y., Liu X., Zhang Q.i., Wu H., Yan D., Liu Y., et al. Carotenoid accumulation and gene expression in fruit skins of three differently colored persimmon cultivars during fruit growth and ripening. Sci Hortic. 2019;248:282–290. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu W., Ye Q., Jin X., Han F., Huang X., Cai S., et al. A spontaneous bud mutant that causes lycopene and β-carotene accumulation in the juice sacs of the parental Guanxi pummelo fruits (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) Sci Hortic. 2016;198:379–384. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhm V., Frhlich K., Bitsch R. Rosehip - A “new” source of lycopene? Mol Aspects Med. 2004;24(6):385–389. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(03)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baranska M., Schutze W., Schulz H. Determination of lycopene and beta-carotene content in tomato fruits and related products: Comparison of FT-Raman, ATR-IR, and NIR spectroscopy. Anal Chem. 2006;78(24):8456–8461. doi: 10.1021/ac061220j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perkins-Veazie P., Collins J.K., Pair S.D., Roberts W. Lycopene content differs among red-fleshed watermelon cultivars. J Sci Food Agric. 2001;81(10):983–987. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang J., Sun H., Guo S., Ren Y.i., Li M., Wang J., et al. Decreased protein abundance of lycopene β-cyclase contributes to red flesh in domesticated watermelon. Plant Physiol. 2020;183(3):1171–1183. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu C.J., Fraser P.D., Wang W.J., Peter M.B. Differences in the carotenoid content of ordinary citrus and lycopene-accumulating mutants. J Agri Food Chem. 2006;54(15):5474–5481. doi: 10.1021/jf060702t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]