Abstract

Study Background

In a pluralistic health care delivery model, it is important to assess whether the individual's health care choices are based upon evidences of efficacy and safety. Since the essence of medical pluralism lies in the fact that all such systems are equally accessible to a seeker, in such situation, it is highly relevant to check what defines such choices in real life.

Objective

To identify the factors influencing the health care choices in a subpopulation seeking Ayurveda health care in an Ayurvedic teaching hospital.

Materials and Method

The study was an all-inclusive cross sectional survey, done on randomly selected out patients visiting an Ayurveda teaching hospital. The data was collected using a 21 items questionnaire refined through pilot testing from 7.9.2017 to 30.9.2017.

Results

The data of 289 respondents who have given their consent were included in statistical analysis. Out of 21 variables studied for their agreement or disagreement in the study population 8 were found to have a significant proportion in favour of agreement. Among these relative safety (Item 9); disease eradicating potential (Item 14); belief (Item 3) and indirect evidences of efficacy (Item 4) were found to have high significance (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Participants chose Ayurveda treatment due to its perceived safety and probability of helping in a particular clinical condition. Contrary to the common perception, enabling factors like availability, accessibility and affordability were given less importance by the participants in making health care choices related to Ayurveda.

Keywords: Cross sectional survey, Pluralistic health care, Health care choice, Aayurveda

1. Introduction

Knowing about the methods and reasons people utilize to choose their health care systems may have substantial value for the policy makers and the market leaders in health care [1]. How and why one health care system is valued over the other in context of a disease and how it is weighted against expected benefits, availability, affordability and accessibility to an individual has a great bearing in health care choice determination. The reasons of choosing a system may be more abstract than the tangible trio of accessibility, availability and affordability as it can surely get influenced by evidences of clinical benefits witnessed directly or indirectly in similar clinical context.

Indian health policy embraces medical pluralism by allowing scores of health care systems to function fully and freely in a clinical context open to patient's choice. State itself has no directives of its own for preferring one system over the other and thereby it’s open to patients to choose their health care providers. State however does have its regulations to prohibit unethical practices and claims not based upon tenable scientific evidences [2]. The ultimate objective of any pluralistic health care policy however should be to provide a competitive yet effective health care choice to the patients suiting to their individual needs and matching to their cultural belief. By providing an open access to all health care opportunities, it also indirectly insists the systems to generate the evidences related to their comparative benefits and to help the people take an informed decision about their health care choices based upon strong scientific evidences and not merely on belief [3]. The benefits of this Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) approach are straight, immediate and sustainable. Demonstration of benefits of one system over the other in particular clinical condition will help filtering various health care systems on the basis of their strengths and advantages in a realistic clinical context and eventually will help sharing the burden of disease among various players operating simultaneously in the field on the basis of their proven strengths. This will come as an immense help to the policy makers for enabling them to allocate the resources on the basis of actual burden sharing among different systems. This will also help focusing upon further improving the areas of strength in various systems to make them more dependable and reproducible [4].

For the actual beneficiaries, the benefits of CER approach are invaluable as it opens up the possibility of providing the information about the advantages of one health care system over the other referring to a particular clinical condition matching to their interest. Such benefits may be multifaceted and tangible in terms of early interventions, reduced cost and better prognosis.

For any CER related research however, utmost importance is to see what actually prompts the patients to seek advice from a particular health care system in the absence of demonstrable CER related information and evidences. Getting inspired from such observations, the realistic goals of functioning of a health care system may be evolved to meet the patient's expectations and at the same time misbeliefs of patients may also be countered by putting the counter evidences. Any other compelling factor unrelated to clear clinical benefits of a particular system may be revealed by such observational studies and will help taking the appropriate measures by the authorities to improve the situation. This cross sectional survey of patients visiting an Ayurvedic teaching hospital to screen the reasons for choosing Ayurveda as a preferred health care system therefore seems to serve many purposes and warrants for similar studies at many other health care facilities across the country to briefly underline all the factors which play decisively behind the choice of a health care system in a pluralistic health care model to optimize the role of every system eventually to maximize the benefits while reducing the cost and time.

This cross sectional survey conducted in 289 outpatient department (OPD) visitors during the routine services at State Ayurvedic College and Hospital, Lucknow for a September month in 2017 consisted of a set of 21 hypothesised reasons for the respondent's preference of Ayurveda. The participants were asked to mark their dissonance or resonance to the proposed reasons as were applicable in their case. Through this exercise, the survey was able to screen the respondent's reasoning of visiting an Ayurvedic hospital for their healthcare needs. The survey was also able to screen the belief and misbeliefs playing decisively in choosing the particular health care system. The commonest belief shared by majority of respondents was related to culture and belief making these strong influencers behind the choice of Ayurveda. Recommendations (by someone, the respondents rely upon), belief (upon safety and least adversity of Ayurveda) and radical curing potential are other reasons the people have attributed for their adherence to Ayurveda.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Developing the survey items

Keeping the focus of the survey in mind, an open brain storming session was organized in the Department of Kaya Chikitsa, State Ayurvedic College and Hospital (SAC&H), Lucknow in August 2017 to discuss about all possible causes prompting a patient to seek Ayurveda treatment and to arrive at SAC & H, Lucknow for the possible care. The discussion involved 30 participants including the faculty members, PG scholars and interns holding their duties in OPs and IPs in the hospital. Besides this, the discussion also involved BAMS final year students having Kaya Chikitsa as a subject and having their rotational duties in Kaya Chikitsa related OPs and IPs. The discussion focused upon various aspects and possibilities as probable reasoning prompting the patients to choose Ayurveda as their health care provider. It primarily discussed three principle factors namely predisposing factors, enabling factors and need factors and their various components for their roles in choosing Ayurveda as the preferred health care system in a situation. Predisposing factors involved the direct or indirect information about Ayurveda owned by the patients and their presumption of it being helpful in context of their disease. Enabling factors involved affordability, availability and accessibility as prime causes for this care related decision making. Need factors have further discussed the disease profile and possibility of patient's weighing of other possible interventions suiting or un-suiting to the individual's need. The moderator (SR) of the brain storming session initiated the discussion and each point of concern was discussed in detail to reach a consensus.

As a result of the brain storming, 19 primary reasons have been identified and agreed for their possible individual or collective roles in the Ayurveda health care seeking decision making. Subsequently, these reasons have been transformed into direct questions having a possibility of being replied in ‘yes’ or ‘no’ format to show the respondent's agreement or disagreement with the reasons proposed by the interviewer as one of the several causes leading him/her to choose Ayurveda health care. An agreement or disagreement method was preferred over any other measurment scale since the survey items have included almost every possible reason for choosing Ayurveda and hence were clearly identifiable for their presence or absence in a given case. Using a dichotomous rating scale was having further advantages of offering clarity and swiftness in choosing the reply [5,6].

The questionnaire was subsequently validated for its construct and content and was pilot tested in a small sample patient population during a working Kaya Chikitsa OPD. On the basis of pilot observations, two complex items in the original questionnaire were split into parts making the final questionnaire containing 21 items (Supplementary file).

2.2. Conduction of the survey

2.2.1. Approval of the study

Since the study did not involve any intervention, an ethical clearance from Institutional Ethics Committee was not sought. All the survey participants were duly informed about the survey purpose and method of its execution. Only those who have given their consent to participate were included in the study.

2.2.2. Setting of the study

The survey study was conducted in Out Patient department of State Ayurvedic College and Hospital, Lucknow, having outpatient facilities to all clinical disciplines running on daily basis. The hospital has an average foot fall of about 350–400 new and follow up patients every day.

3. Method of data collection and respondent's characteristics

The survey data was collected on a printed form having the brief description of the survey, followed by the respondent's demography and actual survey items. The survey sheet was prepared in Hindi for ease of understanding by the people attending the hospital. The respondents were asked to read the survey items and to mark their responses as yes or no (√ or X) if they agree or disagree to the statements. After completion of the survey the filled forms were collected and subjected to data entry and analysis.

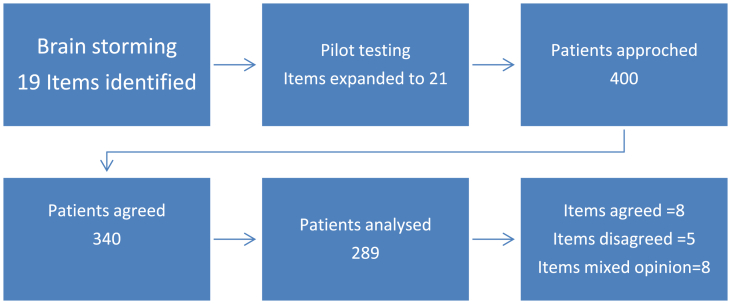

Actual data collection was done from (7.9.2017 to 30.9.2017). Data was collected between 9.00 AM till 1.00 PM on all regular hospital days in the OP section of the hospital. Respondents were chosen randomly irrespective of their age, gender or clinical condition from the pool of patients who have come to Ayurveda hospital for the purpose of consultation. On any single day, the sample was selected from all places in the OP section including all working OP clinics in order to have a mixed clinical profile of the respondents. The survey was conducted by the BAMS final year students who had been the part of initial brain storming session which took place in August 2017. Those who volunteered themselves to help in collection of the data were given an initial induction, explanation and training about methods of collecting the data. The data collection proforma was thoroughly explained referring to the explicit meaning of individual assessment items. About 20 students, who volunteered for data collection, were given the data collection sheets in sufficient number and were told to collect the data from waiting, consultation and dispensing area of the OP section of the hospital. Care was taken to avoid duplicity in data collection (enquiring the same patient twice), omission of responses (incomplete responses) and hurried response (study flow chart Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart.

3.1. Statistical analysis

Data was stored and analysed with the help of Microsoft Excel 2007 (Redmond, Washington, United States). A descriptive analysis inclusive of response observation in % was done for the survey. Further to this, significance test was also applied to check the significance of the responses. Since there is no similar previously published study for population, it was assumed that the proportion of participants agreeing and disagreeing were equal. In other words, saying yes or proportion of yes = 50% i.e. 0.50 so P = 0.50. Z test is applied to the data to find whether the observed opinions have any statistically significant difference in compared to initiall assumption. The analysis was done on 21 sets of variables as were covered in survey questionnaire.

4. Results

Among all patients who have visited OP section of the hospital during the survey days, total 400 patients have randomly been approached for the purpose of survey related data collection. Among these 60 (15%) have refused to participate in the study due to paucity of time. Among 340 participants who participated in the survey, responses from 51 (14.70%) were eliminated from the study due to incomplete or missing data. An analysis of these incomplete responses prima facie identified poor conduction of interview by few of the volunteers leading to incomplete data collection. Final analysis was done on 289 patients having complete data. The study participants comprised of 152 (52.59%) males and 137 (47.40%) females. Average age of the study participants was 44 (±12.40) years. Average time to conduct the survey was 7.05 (±3.52) minute (study flow chart) (Fig. 1).

Out of 21 surveyed items, total 13 items (2,3,4,5,6,9,11,12,13,14,17,18 and 19) were found to have a significant difference of opinion on the basis of their z and p values (Table 1). On the basis of sign of z value, this may easily be interpreted if the respondents agreed with propositions or not. On the basis of z value sign convention, we identified item 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 13, 14 and 19 as significantly agreed items whereas item 6, 11, 12, 17 and 18 were significantly disagreed items. Within the significantly agreed items the highest agreement (commonest reasons) was observed for items 9, 14, 3 and 4 whereas less common agreement was for 2,13and 19. Item 5 was ‘least common’ in terms of agreement. These items are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Proportion of responses for survey items and their significance.

| Items | Short description | Agree | % | Disagree | % | Z | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Cost of therapy | 156 | 53.97 | 133 | 46.03 | 1.353 | p>0.05 |

| Q2 | Inefficacy of other systems | 200 | 69.20 | 89 | 30.80 | 6.529 | p < 0.001 |

| Q3 | Belief | 229 | 79.23 | 60 | 20.77 | 9.941 | p < 0.001 |

| Q4 | Indirect evidences of efficacy | 217 | 75.08 | 72 | 24.92 | 8.529 | p < 0.001 |

| Q5 | Direct evidences of efficacy | 175 | 60.34 | 114 | 39.66 | 3.588 | p < 0.001 |

| Q6 | Referral from allopathy | 47 | 16.26 | 242 | 83.74 | −11.471 | p < 0.001 |

| Q7 | Curiosity | 154 | 53.28 | 135 | 46.72 | 1.118 | p>0.05 |

| Q8 | Self-search | 119 | 41.17 | 170 | 58.83 | −3.000 | p < 0.01 |

| Q9 | Safety | 240 | 83.04 | 49 | 16.96 | 11.235 | p < 0.001 |

| Q10 | Side effects of allopathy | 170 | 58.82 | 119 | 41.18 | 3.000 | p < 0.01 |

| Q11 | Avoidance of surgery | 91 | 31.48 | 198 | 68.52 | −6.294 | p < 0.001 |

| Q12 | Prognosticated by others | 63 | 21.79 | 226 | 78.21 | −9.588 | p < 0.001 |

| Q13 | Previous experience | 187 | 64.70 | 102 | 35.30 | 5.000 | p < 0.001 |

| Q14 | Disease eradicating potential | 231 | 79.93 | 58 | 20.07 | 10.176 | p < 0.001 |

| Q15 | Lifelong therapy in other systems | 154 | 53.28 | 135 | 46.72 | 1.118 | p>0.05 |

| Q16 | No investigations | 139 | 48.09 | 150 | 51.91 | −0.647 | p>0.05 |

| Q17 | Less crowded hospital | 114 | 39.44 | 175 | 60.56 | −3.588 | p < 0.001 |

| Q18 | Proximity of hospital | 102 | 35.29 | 187 | 64.71 | −5.000 | p < 0.001 |

| Q19 | General belief of efficacy in my condition | 185 | 64.01 | 104 | 35.99 | 4.765 | p < 0.001 |

| Q20 | Need of Integrative therapy | 121 | 41.86 | 168 | 58.32 | −2.765 | p < 0.01 |

| Q21 | Wish to discontinue allopathy | 167 | 57.78 | 122 | 42.22 | 2.647 | p < 0.01 |

Table 2.

Significantly agreed, disagreed and indifferent items in the survey sheet.

| Item No | Items significantly agreed |

|---|---|

| 2 | अन्य उपायों से मुझे अपेक्षित लाभ नही हो रहा है। I am not getting adequate benefits from other interventions. |

| 3 | मुझे आयुर्वेद पर विश्वास है। यह हमारी अपनी चिकित्सा पद्ध्यति है। I believe in Ayurveda. This is our own system of medicine. |

| 4 | आयुर्वेदिक चिकित्सा काम करती है, ऐसा मैने अपने दोस्त/रिश्तेदार को कहते सुना है। Ayurvedic therapy works, I heard about this from my friends/relatives. |

| 5 | आयुर्वेदिक चिकित्सा काम करती है, ऐसा मैने प्रत्यक्ष मे किसी पर देखा है। Ayurvedic therapy works. I have seen it directly. |

| 9 | आयुर्वेदिक चिकित्सा निरापद है । इसका कोई साइड इफ़ेक्ट नहीं है। Ayurvedic therapy is not having side effects. |

| 13 | मैने पहले भी आयुर्वेद से इलाज लिया था। मुझे उससे लाभ हुआ था । I have taken ayurvedic therapy previously and got benefitted. |

| 14 | आयुर्वेद रोग को जड से खतम कर देता है । एलोपैथी रोग को दबा देती है। Ayurveda eradicates the disease whereas allopathy only palliates it. |

| 19 | मेरी बीमारी मे आयुर्वेद का इलाज ही सबसे बेहतर है ऐसा सभी कहते है। Ayurveda has best remedy for my type of problems, everyone says this. |

| Item No | Items significantly disagreed |

|---|---|

| 6 | मेरे एलोपैथी चिकित्सक ने मुझे आयुर्वेद से सलाह लेने को कहा है । My allopathy physician has told me to get an opinion from Ayurveda. |

| 11 | मेरे एलोपैथी डाक्टर ने आपरेशन के लिये बताया है। मै आपरेशन नही करवाना चाहता हूं। My Allopathy physician has told me to go for surgery. I don't want to have surgery. |

| 12 | मेरे एलोपैथी डाक्टर ने बताया है कि मेरी बीमारी का उनके पास कोई इलाज नही है। मै इलाज की खोज में आयुर्वेद में आया हू।My Allopathy physician told that they don't have a remedy for my problem. I came to Ayurveda for search of remedy. |

| 17 | एलोपैथिक अस्पताल में भीड बहुत होती है। आयुर्वेदिक अस्पताल मे भीड नही होती। Allopathy hospitals are overcrowded. There are fewer crowds in Ayurveda hospitals. |

| 18 | यह मेरे घर के सबसे करीब का अस्पताल है । बाकी अस्पताल अधिक दूरी पर है। Ayurveda hospital is nearest to my place. Other hospitals are far away. |

| Item No | Item description having not significant difference of opinion |

|---|---|

| 1 | अन्य इलाज की विधियां मंहगी हैं जबकि आयुर्वेदिक चिकित्सा सस्ती है। Other treatments are expensive whereas Ayurvedic treatment is cheap. |

| 7 | मै यह जानने को उत्सुक हू कि आयुर्वेद कैसे काम करता है। I am eager to know how Ayurveda works. |

| 8 | इन्टरनेट में ढूंडने तथा किताबो को पढने से मुझे लगा कि आयुर्वेद से मेरा इलाज हो सकता है । While searching on internet and books I felt that I can be treated through Ayurveda. |

| 10 | एलोपैथी मुझे सूट नही करती । उससे मुझे नुकसान होते हैं। Allopathy does not suit me. It harms me. |

| 15 | एलोपैथी में जिन्दगी भर दवा खानी पडती है। In Allopathy the drugs are needed to be taken throughout the life. |

| 16 | एलोपैथिक डाक्टर बहुत सी जांचे करवाते है। आयुर्वेद मे जांच नही होती। Allopathy doctors ask for many investigations. Ayurveda do not require investigations. |

| 20 | मैं एलोपैथिक इलाज के साथ आयुर्वेदिक इलाज भी चाहता हूं जिससे मुझे ज्यादा फायदा मिले। I need Ayurvedic treatment along with allopathic treatment to maximise the benefits. |

| 21 | मै अपनी बीमारी के लिये चल रही एलोपैथिक दवायें छोडना चाहता हूं। I want to withdraw the allopathic medicines which I am taking for my illness |

5. Discussion

Among 21 potential reasons presumed to have an influencing effect upon the decision making of patients related to their choice of Ayurveda and displayed as the survey items to respond for agreement or disagreement, 13 (61.90%) were found to have significant difference between the opinions with a clear inclination towards agreement or disagreement. Among 13 items, 8 (61.53%) were found to have a significant influence upon decision making through agreement whereas 5 (38.46%) have made it by clearly disagreeing to it. Contrary to the common belief, such Ayurvedic hospital visits are not guided by the recommendations from other system practitioners, reach of the hospital and ease of consultation available in an Ayurveda hospital.

5.1. Items leading to significant agreement

8 items from the survey which have largely been agreed by the respondents as the factors influencing their turning to the Ayurveda as a health care choice were largely related to the need factors related to the disease (I am not getting adequate benefits from other interventions; Ayurveda has best remedy for my type of problems, everyone says this; Ayurvedic therapy is not having side effects.), and predisposing factors related to the direct or indirect information about Ayurveda the patients already had (I believe in Ayurveda. This is our own system of medicine; Ayurvedic therapy works, I heard about this from my friends/relatives; Ayurvedic therapy works. I have seen it myself; I have expirienced Ayurvedic therapy previously and got benefitted from it; Ayurveda eradicates the disease whereas Allopathy only palliates it). Most importantly the enabling factors involving affordability, availability and accessibility have not been surfaced in the survey as important influencing factors related to choice of Ayurveda as a health care provider. The agreement pattern in the survey clearly demonstrated a specific reasoning behind the choice of Ayurvedic therapy. This is evident that the choice is largely disease specific and is driven by the indirect or direct evidences of its presumed effectiveness and safety in the clinical condition of interest. Contrary to the common perception of choosing Ayurveda on account of its low cost, ease of accessibility and availability, the survey clearly discarded these as having any dependable impact upon health care choice.

5.2. Items leading to significant disagreement

Among the items leading to significant disagreement from the respondents most important ones are related to the possibility of any cross referral from Allopathy to Ayurveda as a possible influencing factor. Most respondents denied the items suggesting a cross referral from Allopathy to Ayurveda (My allopathic physician has told me to get an opinion from Ayurveda; My Allopathy physician told that they don't have a remedy for my problem. I came to Ayurveda for search of remedy). The respondents also have denied any withholding of the standard therapy including surgery as their reason for looking out at alternatives like Ayurveda (My Allopathic physician has told me to go for surgery. I don't want to have surgery). Enabling factors like distance from home and ease of consultation also did not found ground in the survey as most respondents disagreed for these playing any role in decision making (Allopathic hospitals are overcrowded. There are fewer crowds in Ayurveda hospitals; Ayurveda hospital is nearest to my place. Other hospitals are far away).

5.3. Items leading to insignificant difference of opinion

Among 21 items included in the survey 8 items could not find any significant difference of opinion among the respondents. Items 1, 7,8,10, 15, 16, 20 and 21 have nearly equal proportion of agreement and disagreement (Table 2) among the respondents hence these were considered as non-influencing factors in the health care choice related to the conducted survey. The items where a clear trend of agreement or disagreement could not be established were related to cost (Other treatments are expensive whereas Ayurvedic treatment is cheap), inquisitiveness (I am eager to know how Ayurveda works), recent information obtained through common resources (While searching on internet and books I felt that I can be treated through Ayurveda), unsuitability of other system (Allopathy does not suit me), belief related to other system of care (In Allopathy the drugs are needed to be taken throughout the life; Allopathy doctors ask for many investigations. Ayurveda do not require investigations) and personal agenda (I need Ayurvedic treatment along with allopathic treatment to maximise the benefits; I want to withdraw the allopathic medicines which I am taking for my illness). This is obvious to see that these items do not show a clear trend of agreement or disagreement and hence cannot be considered as the trends preferred by majority thus showing a common opinion.

Factors influencing the health care choices have been the area of intensive research among health policy researchers. The common factors found influencing to health care choices were demographic, socioeconomic, insurance status, quality of care, household size and cost of health care [7,8]. Studies have also been conducted to explore the rising trends of people turning towards specialty hospitals comparing to primary health care centers leading an overcrowding in higher centers and relative underutilization of primary care centers [9]. Quality of care and availability of facilities including drugs from essential drug list (EDL) have been identified as the primary reasons of suboptimal utilization in such cases. The similar trend has also been observed in Ayurveda where its primary care centres are found struggling with basic infrastructure and facilities and hence are sub optimally utilised [10]. Prescription quality in Ayurveda is also been brought under the scanner and found as an important influencing factor behind the quality of health care eventually determining the health care choice [11]. Observations from speciality clinics of Ayurveda have clearly demonstrated the patient's choices towards the optimization of care within their preferred health care systems [12].

There had been clear constructs showing the parameters of service quality identified by the patients in any health care setting [13]. Previous experiences come as strong influencing factors to determine the choice of a health care not only in one's own case but it also in the form of advice influencing the decision in a given case.

This is largely observed that the health care choices in a pluralistic health care delivery system as is embraced in India are much different than a singular or a pauci system health care delivery with limited choices. This would have been a very promising research in context of India to look at what actually prompts someone to choose a system of health care and what are the factors which influence this behaviour. On the basis of research, this can easily be projected if the behaviour is based upon substantial facts and observations and is expected to deliver the outcomes the people are expecting from the system. On the contrary, if there are confounding factors influencing the behaviour, a serious effort should be made to minimise their influence by providing the counter mechanisms to minimise the effects of confounding factors. Despite of its huge implications and impact on net health care delivery in the country and net improved outcome of the delivered health care, not many researches have been done in this area.

Based on a nationally representative health survey 2014, an analysis to understand utilization of AYUSH care across the socioeconomic and demographic groups in India was done [14,15]. Overall, 6.9% of all patients seeking outpatient care in the reference period were found using AYUSH services without any big rural-urban divide. Use of AYUSH among middle-income households was lower when compared with poorer and richer households. AYUSH care utilization was higher among patients with chronic diseases and also for treating skin-related and musculo-skeletal ailments. Although the overall share of AYUSH prescription drugs in total medical expenditure is only about 6% but the average expenditure for drugs on AYUSH and allopathy did not differ hugely. The discussion compares our estimates and findings with other studies and also highlights major policy issues around mainstreaming of AYUSH care. Many observations made in this study are similar to what has been observed by our study. We have observed that the need based factors related to disease play crucially in choosing a health care system and the cost of the therapy do not come as a big deterrent in choice of the health care. There had been strong socio-cultural influences playing decisively regarding the health care choices [16]. Any effort to optimise the health care delivery and its outcome in India should focus upon the factors influencing the health care choices, meeting adequately with factors affecting adversely to the optimisation of outcomes, promotion of comparative effectiveness research across various health care disciplines and dissemination of the evidences regarding the effectiveness of particular systems in particular disease context [17].

Factors affecting the health care choices may have significant effects upon the net outcome in the context of an illness. If inappropriately chosen under the influence of driving factors, the outcome may result in the suboptimal care, delayed responses, increased cost of the therapy and damages beyond the level of repair. In a country where multiple systems of health care are freely available to choose from without any real awareness among the people about the advantages and disadvantages of various systems in particular context, this becomes imperative to know about the factors influencing the choice of health care system. Minimal cross system referrals leading to the underutilisation of one system by the practitioners of other systems makes this further important [18]. In the absence of authentic information to choose the appropriate health care system, the choices are often self-driven and influenced by factors operating in a particular context. There are chances of selection to be incorrect hence leading to inadvertent damages. By understanding the reasons of health care choices, the policies can be made to promote the factors leading to the informed decision making by promoting comparative effectiveness evidence generation. At the same time the factors other than evidence of effectiveness may effectively be dealt by the appropriate policies and actions to minimise their influence on health care decision making. A cross talk between various systems for the exploration of their limitations and advantages seems to be a crucial step in this regard [19]. This study, in the broader perspective of enabling the patients to make an informed choice regarding their health care provider, seems to be a landmark observation as it begins discussing about one of the most important yet highly ignored aspect of evidence based health care. This is the time we need to respect the patients for their own health care choices but at the same time without giving up our responsibility to make them better informed in the pretext of real effectiveness added with availability, accessibility and affordability of the health care system desired to opt [20]. The ultimate objective is to serve the patient with the best possible health care without getting compromised on the backdrop of any limiting factor.

This study however should be viewed through its limitations related to limited sample number and screening of a subpopulation from an Ayurvedic hospital which had already made its health care choice. The ideal scenario would have been to get the survey done among the people who are suffering from some clinical condition and have not yet made a choice. Since it is repeatedly argued that Ayurveda is largely sought for help in some specific clinical conditions and not in all, the analysis presented in the study is likely to pertain from the patient group having a similar clinical condition. An identification of clinical conditions for which the people have come to seek Ayurveda consultation may have added value to this work. Despite the survey being conducted some time back, the context of the research has not been changed during this time and the observations reported are still highly relevant. Moreover we are not aware of any other published article pertaining to the area during this time. Lack of participant's data in terms of socio economic status, rural or urban background, and educational status may also be viewed as a limitation in the context of present study.

6. Conclusion

In pluralistic health care delivery model, it is important to see if the health care choices are being made on the basis of existing evidences. A wrong choice in health care may have miserable consequences. This cross sectional study, probably first of its kind, had clearly demonstrated that such choices in Ayurveda are not actually evidence based but are driven through belief and socio-cultural connotations. Choosing factors like relative safety, disease eradicating potential, belief and indirect evidences of efficacy as primary reasons for opting Ayurveda health care by majority of respondents emphasises that these areas should be dealt more emphatically in order to create better evidences in future. It is also evident from this study that affordability, accessibility and availability has less important role to play in decision making related to Ayurveda. These observations have a great bearing for future policy making and research drive in Ayurveda as it may help making the choice more gratifying for the people who opt for Ayurvedic health care for their clinical conditions.

Funding

The study was not funded by any funding agency in any form.

Author contributions

Sanjeev Rastogi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing Original draft, final approval of draft, Supervision. Vandana Tiwari: Data collection, Writing- review of draft. Swayam Prabha Jatav: Data collection, Writing- review of draft. Nilendra Singh: Data collection, Writing- review of draft. Sonam Verma: Data collection, Writing- review of draft. Sharmishtha Verma: Data collection, Writing- review of draft. Krishna Gopal Sharma: Data collection, Writing- review of draft. Preeti Pandey: Data collection, Writing- review of draft. Girish Singh: Validation, Data analysis, Writing- editing of draft.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgement

Students of BAMS final year (2012-13 batch),Interns and PG scholars, Department of Kaya Chikitsa, State Ayurvedic College and Hospital, Lucknow are acknowledged for their help in organising the brain storming session, framing the items, pilot observations and the data collection.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Transdisciplinary University, Bangalore.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaim.2021.100539.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rastogi Sanjeev, Bhattacharya Arindam. Translational Ayurveda. Springer; Singapore: 2019. Dreaming of health for all in an unequal world: finding a fit for traditional health care exemplified through ayurveda; pp. 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The drug and magic remedies (objectionable advertisement) act. 1954. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1412/1/195421.pdf available at: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rastogi S. In: Comparative Effectiveness Research. Francesco Chiappeli., editor. Nova Science Publishers; New York: 2016. Comparative effectiveness research: Appropriating the benefits of traditional health care referring Ayurveda; pp. 507–516. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rastogi Sanjeev. Comparative effectiveness research: implication deeper than it may be felt. Indian J Surg. 2020;82:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhupalam P. Yes or No 2.0: are likert scales always preferable to dichotomous rating scales? IJPI. 2019;9(3):146. https://www.jpionline.org/index.php/ijpi/article/view/412 [internet]. 5Nov.2019 [cited 11Jan.2021] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeCastellarnau A. A classification of response scale characteristics that affect data quality: a literature review. Qual Quantity. 2018;52(4):1523–1559. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0533-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uchendu O.C., Ilesanmi O.S., Olumide A.E. Factors influencing the choice of health care providing facility among workers in a local government secretariat in South Western Nigeria. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2013;11(2):87–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halasa Y., Nandakumar A.K. Factors determining choice of health care provider in Jordan. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15(4):959–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y., Kong Q., Yuan S., van de Klundert J. Factors influencing choice of health system access level in China: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201887. Published 2018 Aug 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rastogi S. Quality of Ayurvedic health care delivery in provinces of India: lessons from essential drugs availability at State run Ayurveda dispensaries. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2018;9(3):233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rastogi S. Development and pilot testing of a prescription quality index for Ayurveda. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2019;10(4):277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rastogi S. Emanating the specialty clinical practices in Ayurveda: preliminary observations from the Arthritis clinic and its implications. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2020;S0975–9476(19) doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2019.09.009. 30335-3[published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 1] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rastogi S. Effectiveness, safety, and standard of service delivery: a patient-based survey at a pancha karma therapy unit in a secondary care Ayurvedic hospital. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2011;2(4):197–204. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.90767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudra S., Kalra A., Kumar A., Joe W. Utilization of alternative systems of medicine as health care services in India: evidence on AYUSH care from NSS 2014. PLoS One. 2017;12(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176916. Published 2017 May 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh R.H. Declining popularity of AYUSH, the recent report of national sample survey organization. Anals Ayur. Med. 2015;4:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Islary Jacob. Health and health seeking behaviour among tribal communities in India: a socio-cultural perspective. Journal of Tribal Intellectual Collective India. June 16, 2014:1–16. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3151399 Available at: SSRN: [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh R.H. Doing ayush in India today: against all odds. Annals Ayurvedic Med. 2015;4:2–4. 1-2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.AYUSHMAN BHARAT comprehensive primary health care through health and wellness centers, operational guidelines. https://ab-hwc.nhp.gov.in/ Available at:

- 19.National education policy 2020, professional education. 2020. https://www.mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheehan H.E. Medical pluralism in India: patient choice or no other options? Indian J Med Ethics. 2009;6(3):138–141. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2009.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.