Abstract

Background

Acupuncture is increasingly used in people with epilepsy. It remains unclear whether existing evidence is rigorous enough to support its use. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2008.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of acupuncture in people with epilepsy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialised Register (June 2013) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (2013, Issue 5), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and other databases (from inception to June 2013). We reviewed reference lists from relevant trials. We did not impose any language restrictions.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing acupuncture with placebo or sham treatment, antiepileptic drugs or no treatment; or comparing acupuncture plus other treatments with the same other treatments, involving people of any age with any type of epilepsy.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration.

Main results

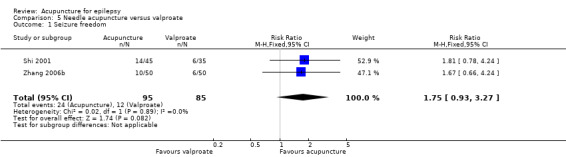

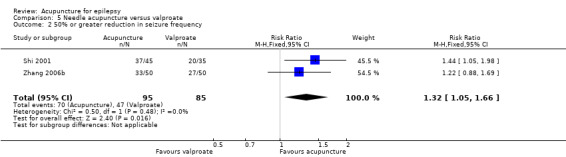

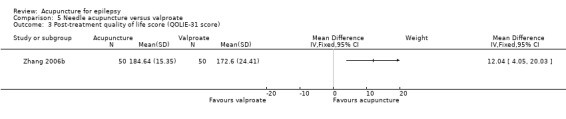

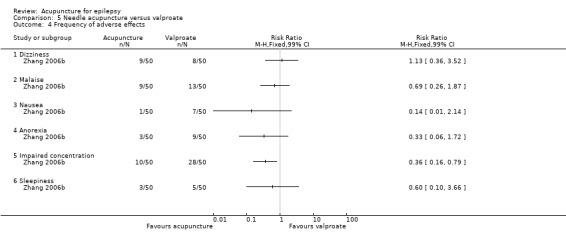

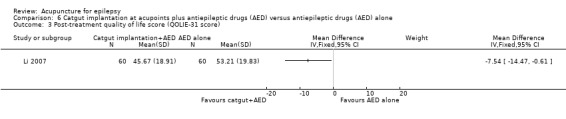

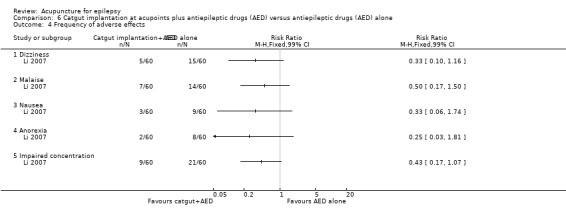

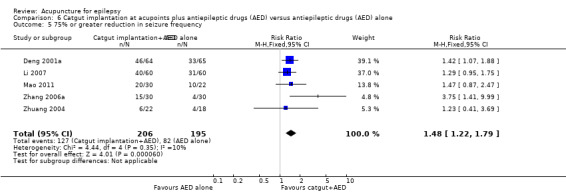

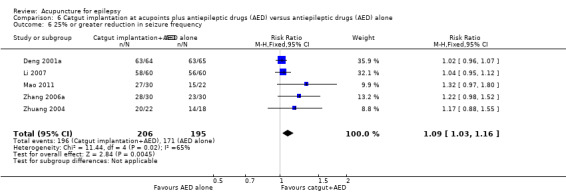

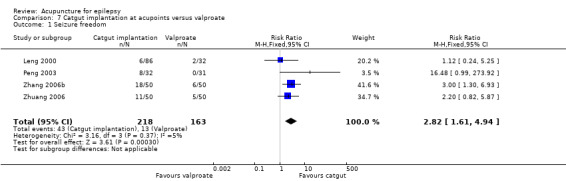

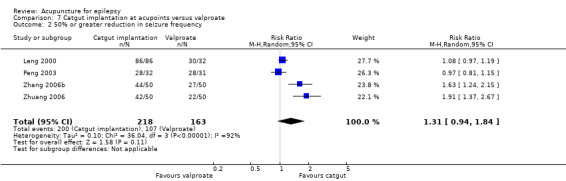

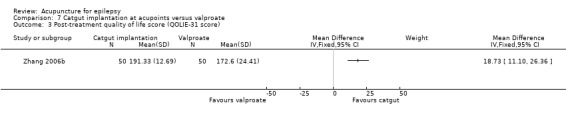

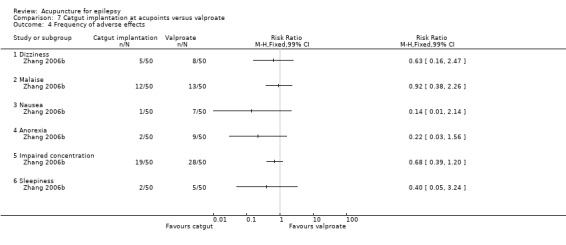

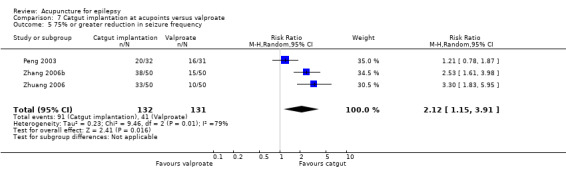

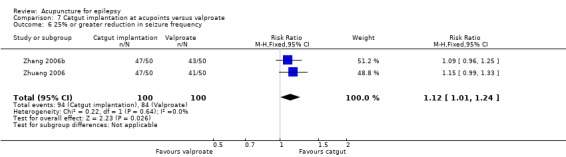

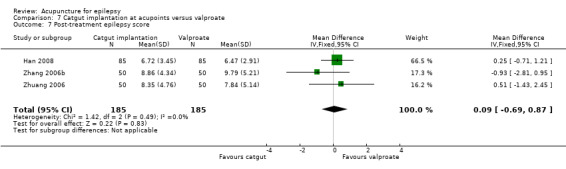

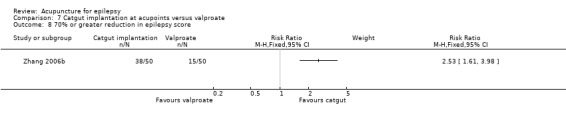

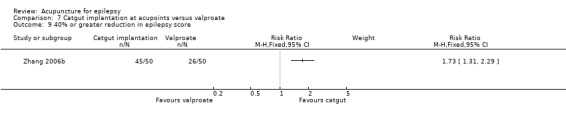

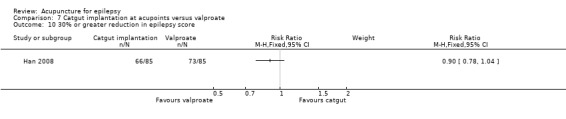

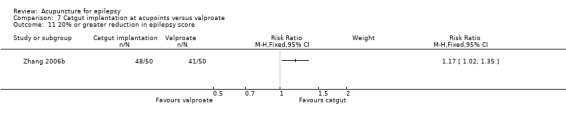

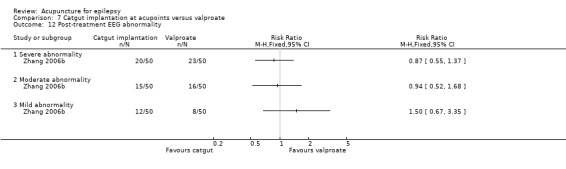

We included 17 RCTs with 1538 participants that had a wide age range and were suffering mainly from generalized epilepsy. The duration of treatment varied from 7.5 weeks to 1 year. All included trials had a high risk of bias with short follow‐up. Compared with Chinese herbs, needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs was not effective in achieving at least 50% reduction in seizure frequency (80% in control group versus 90% in intervention group, RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.31, 2 trials; assumed risk 500 per 1000, corresponding risk 485 to 655 per 1000). Compared with valproate, needle acupuncture plus valproate was not effective in achieving freedom from seizures (44% in control group versus 42.7% in intervention group, RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.30, 2 trials; assumed risk 136 per 1000, corresponding risk 97 to 177 per 1000) or at least 50% reduction in seizure frequency (69.3% in control group versus 81.3% in intervention group, RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.52 to 3.48, 2 trials; assumed risk 556 per 1000, corresponding risk 289 to 1000 per 1000) but may have achieved better quality of life (QOL) after treatment (QOLIE‐31 score (higher score indicated better QOL) mean 170.22 points in the control group versus 180.32 points in the intervention group, MD 10.10 points, 95% CI 2.51 to 17.69 points, 1 trial). Compared with phenytoin, needle acupuncture was not effective in achieving at least 50% reduction in seizure frequency (70% in control group versus 94.4% in intervention group, RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.46 to 4.44, 2 trials; assumed risk 700 per 1000, corresponding risk 322 to 1000 per 1000). Compared with valproate, needle acupuncture was not effective in achieving seizure freedom (14.1% in control group versus 25.2% in intervention group, RR 1.75, 95% CI 0.93 to 3.27, 2 trials; assumed risk 136 per 1000, corresponding risk 126 to 445 per 1000) but may be effective in achieving at least 50% reduction in seizure frequency (55.3% in control group versus 73.7% in intervention group, RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.66, 2 trials; assumed risk 556 per 1000, corresponding risk 583 to 923 per 1000) and better QOL after treatment (QOLIE‐31 score mean 172.6 points in the control group versus 184.64 points in the intervention group, MD 12.04 points, 95% CI 4.05 to 20.03 points, 1 trial). Compared with antiepileptic drugs, catgut implantation at acupoints plus antiepileptic drugs was not effective in achieving seizure freedom (13% in control group versus 19.6% in intervention group, RR 1.51, 95% CI 0.93 to 2.43, 4 trials; assumed risk 127 per 1000, corresponding risk 118 to 309 per 1000) but may be effective in achieving at least 50% reduction in seizure frequency (63.1% in control group versus 82% in intervention group, RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.89, 5 trials; assumed risk 444 per 1000, corresponding risk 475 to 840 per 1000) and better QOL after treatment (QOLIE‐31 score (higher score indicated worse quality of life) mean 53.21 points in the control group versus 45.67 points in the intervention group, MD ‐7.54 points, 95% CI ‐14.47 to ‐0.61 points, 1 trial). Compared with valproate, catgut implantation may be effective in achieving seizure freedom (8% in control group versus 19.7% in intervention group, RR 2.82, 95% CI 1.61 to 4.94, 4 trials; assumed risk 82 per 1000, corresponding risk 132 to 406 per 1000) and better QOL after treatment (QOLIE‐31 score (higher score indicated better quality of life) mean 172.6 points in the control group versus 191.33 points in the intervention group, MD 18.73 points, 95% CI 11.10 to 26.36 points, 1 trial) but not at least 50% reduction in seizure frequency (65.6% in control group versus 91.7% in intervention group, RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.84, 4 trials; assumed risk 721 per 1000, corresponding risk 677 to 1000 per 1000). Acupuncture did not have excess adverse events compared to control treatment in the included trials.

Authors' conclusions

Available RCTs are small, heterogeneous and have high risk of bias. The current evidence does not support acupuncture for treating epilepsy.

Plain language summary

Acupuncture for epilepsy

People with epilepsy are currently treated with antiepileptic drugs but a significant number of people continue to have seizures and many experience adverse effects to the drugs. As a result, there is increasing interest in alternative therapies and acupuncture is one of those. Seventeen randomised controlled trials with 1538 participants were included in the current systematic review (literature search conducted on 3rd June 2013).

Compared with Chinese herbs, needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs was not effective in achieving satisfactory seizure control (at least 50% reduction in seizure frequency). If we assumed that 500 out of 1000 patients treated with Chinese herbs alone normally achieved satisfactory seizure control, we estimated that 485 to 655 out of 1000 patients treated with needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs would achieve satisfactory seizure control. Compared with valproate, needle acupuncture plus valproate was not effective in achieving freedom from seizures or satisfactory seizure control. If we assumed that 136 out of 1000 patients treated with valproate alone normally achieved seizure freedom, we estimated that about 97 to 177 out of 1000 patients treated with acupuncture plus valproate would achieve seizure freedom; if we assumed that 556 out of 1000 patients treated with valproate alone normally achieved satisfactory seizure control, we estimated that about 289 to 1000 out of 1000 patients treated with acupuncture plus valproate would achieve satisfactory seizure control. Compared with phenytoin, needle acupuncture was not effective in achieving satisfactory seizure control. If we assumed that 700 out of 1000 patients treated with phenytoin alone normally achieved satisfactory seizure control, we estimated that about 322 to 1000 out of 1000 patients treated with acupuncture alone would achieve satisfactory seizure control. Compared with valproate, needle acupuncture was not effective in achieving seizure freedom but it may have been better in achieving satisfactory seizure control. If we assumed that 136 out of 1000 patients treated with valproate alone normally achieved seizure freedom, we estimated that about 126 to 445 out of 1000 patients treated with acupuncture alone would achieve seizure freedom; if we assumed that 556 out of 1000 patients treated with valproate alone normally achieved satisfactory seizure control, we estimated that about 583 to 923 out of 1000 patients treated with acupuncture alone would achieve satisfactory seizure control. Compared with antiepileptic drugs, catgut implantation at acupoints plus antiepileptic drugs was not effective in achieving seizure freedom, but it may have been better in achieving satisfactory seizure control. If we assumed that 127 out of 1000 patients treated with antiepileptic drugs alone normally achieved seizure freedom, we estimated that about 118 to 309 out of 1000 patients treated with catgut implantation at acupoints plus antiepileptic drugs would achieve seizure freedom; If we assumed that 444 out of 1000 patients treated with antiepileptic drugs alone normally achieved satisfactory seizure control, we estimated that about 475 to 840 out of 1000 patients treated with catgut implantation at acupoints plus antiepileptic drugs would achieve satisfactory seizure control. Compared with valproate, catgut implantation may have been better in achieving seizure freedom but not satisfactory seizure control. If we assumed that 82 out of 1000 patients treated with valproate alone normally achieved seizure freedom, we estimated that about 132 to 406 out of 1000 patients treated with catgut implantation at acupoints alone would achieve seizure freedom; if we assumed that 721 out of 1000 patients treated with valproate alone normally achieved satisfactory seizure control, we estimated that about 677 to 1000 out of 1000 patients treated with catgut implantation at acupoints alone would achieve satisfactory seizure control.

Acupuncture did not have excess adverse events compared to control treatment in the included trials. However, the included trials were small, heterogeneous and had a high risk of bias. It remains uncertain whether acupuncture is effective and safe for treating people with epilepsy.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings: needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs versus Chinese herbs alone.

| Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs compared with Chinese herbs for epilepsy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children (0‐18 years) with generalised epilepsy Settings: hospital inpatients and outpatients Intervention: Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs Comparison: Chinese herbs alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Chinese herbs alone | Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs | |||||

|

50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (follow‐up: 6 months) |

500 per 1000 | 565 per 1000 (485 to 655) | RR 1.13 (0.97 to 1.31) | 120 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | |

|

Adverse effects (follow‐up: 6 months) |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 120 (2) |

See comment | None of included studies reported adverse effects. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. Evidence from RCT downgraded by one level because of high risk of bias in study design.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: needle acupuncture plus valproate versus valproate alone.

| Needle acupuncture plus valproate compared with valproate alone for epilepsy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: participants with generalised epilepsy Settings: hospital outpatients (one included study recruited outpatients only, the other included study did not specify the patient settings) Intervention: Needle acupuncture plus valproate Comparison: Valproate alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| valproate alone | Needle acupuncture plus valproate | |||||

|

Seizure freedom (follow‐up: 3‐6 months) |

136 per 1000 | 132 per 1000 (97 to 177) | RR 0.97 (0.72 to 1.30) | 150 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | |

|

50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (follow‐up: 3‐6 months) |

556 per 1000 | 745 per 1000 (289 to 1000) | RR 1.34 (0.52 to 3.48) | 150 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | |

|

Post‐treatment quality of life (QOLIE‐31 score, which has a range of 0‐200, with higher score indicates better quality of life) (follow‐up: 6 months) |

The mean post‐treatment quality of life across control groups ranged from 170.22 to 172.6 points. | The mean post‐treatment quality of life in the intervention group was 10.1 points higher (2.51 points higher to 17.69 points higher). | 90 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | ||

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ dizziness (follow‐up: 6 months) |

160 per 1000 | 107 per 1000 (19 to 608) | RR 0.67 (0.12 to 3.80) | 90 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ malaise (follow‐up: 6 months) |

233 per 1000 | 193 per 1000 (62 to 592) | RR 0.83 (0.27 to 2.54) | 90 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ nausea (follow‐up: 6 months) |

140 per 1000 | 96 per 1000 (21 to 331) | RR 0.60 (0.15 to 2.36) | 90 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ sleepiness (follow‐up: 6 months) |

119 per 1000 | 84 per 1000 (28 to 248) | RR 0.71 (0.24 to 2.08) | 90 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. Evidence from RCT downgraded by one level because of high risk of bias in study design.

b. Evidence from RCT downgraded by two levels because of high risk of bias in study design and imprecise result.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings: needle acupuncture versus sham acupuncture.

| Needle acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture for epilepsy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with intractable epilepsy Settings: hospital outpatients Intervention: Needle acupuncture Comparison: Sham acupuncture | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| sham acupuncture | needle acupuncture | |||||

|

Percentage reduction in seizure frequency (follow‐up: 12 weeks) |

The median reduction in seizure frequency was 20%. | The median reduction in seizure frequency was 45%. | 34 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | No standard deviation or confidence interval or P value was provided to estimate the confidence interval. | |

|

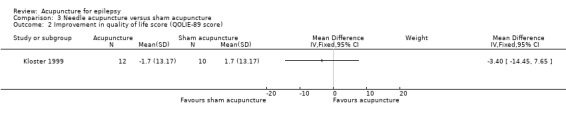

Improvement in quality of life (QOLIE‐89 score, which has a range of 0‐100, with higher score indicates better quality of life) (follow‐up: 12 weeks) |

The mean improvement in quality of life was 1.7 points. | The mean improvement in quality of life in the intervention group was 3.4 points lower (14.45 points lower to 7.65 points higher). | 22 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ||

|

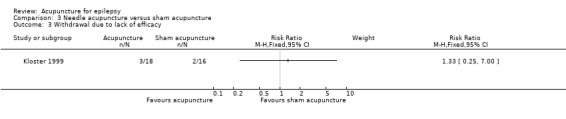

Withdrawal due to lack of efficacy (follow‐up: 12 weeks) |

125 per 1000 | 166 per 1000 (31 to 875) | RR 1.33 (0.25 to 7.00) | 34 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Adverse effects (follow‐up: 12 weeks) |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 120 (2) |

See comment | The included study did not report adverse effects. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. Evidence from RCT downgraded by two levels because of high risk of bias in study design and imprecise result.

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings: needle acupuncture versus phenytoin.

| Needle acupuncture compared with phenytoin for epilepsy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: participants with epilepsy Settings: hospital outpatients (one included study recruited outpatients only, the other included study did not specify the patient settings) Intervention: needle acupuncture Comparison: phenytoin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| phenytoin | needle acupuncture | |||||

|

50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (follow‐up: 6 months) |

700 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (322 to 1000) | RR 1.43 (0.46 to 4.44) | 150 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Adverse effects (follow‐up: 6 months) |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 120 (2) |

See comment | The included study did not report adverse effects. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. Evidence from RCT downgraded by two levels because of high risk of bias in study design and imprecise result.

Summary of findings 5. Summary of findings: needle acupuncture versus valproate.

| Needle acupuncture compared with valproate for epilepsy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: participants with epilepsy (one included study only recruited children with absence epilepsy while another included study recruited both children and adults with generalised epilepsy) Settings: hospital inpatients and outpatients Intervention: needle acupuncture Comparison: valproate | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| valproate | needle acupuncture | |||||

|

Seizure freedom (follow‐up: 3 months to 1 year) |

136 per 1000 | 238 per 1000 (126 to 445) | RR 1.75 (0.93 to 3.27) | 180 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (follow‐up: 3 months to 1 year) |

556 per 1000 | 734 per 1000 (583 to 923) | RR 1.32 (1.05 to 1.66) | 180 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Post‐treatment quality of life (QOLIE‐31 score, which has a range of 0‐200, with higher score indicates better quality of life) (follow‐up: 3 months) |

The mean post‐treatment quality of life across control groups ranged from 170.22 to 172.6 points. | The mean post‐treatment quality of life in the intervention group was 12.04 points higher (4.05 points higher to 20.03 points higher). | 100 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ||

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ dizziness (follow‐up: 3 months) |

160 per 1000 | 181 per 1000 (75 to 429) | RR 1.13 (0.47 to 2.68) | 100 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ malaise (follow‐up: 3 months) |

233 per 1000 | 161 per 1000 (76 to 343) | RR 0.69 (0.33 to 1.47) | 100 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ nausea (follow‐up: 3 months) |

140 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (2 to 157) | RR 0.14 (0.02 to 1.12) | 100 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ sleepiness (follow‐up: 3 months) |

119 per 1000 | 71 per 1000 (17 to 284) | RR 0.60 (0.15 to 2.38) | 100 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. Evidence from RCT downgraded by two levels because of high risk of bias in study design and imprecise result.

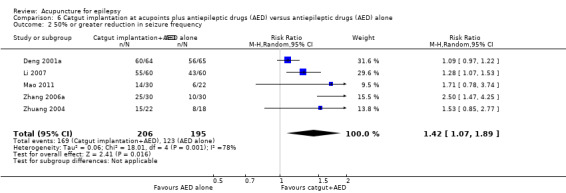

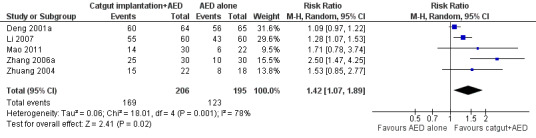

Summary of findings 6. Summary of findings: catgut implantation at acupoints plus antiepileptic drugs versus antiepileptic drugs alone.

| Catgut implantation at acupoints plus antiepileptic drugs compared with antiepileptic drugs alone for epilepsy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: participants with epilepsy Settings: hospital inpatients and outpatients Intervention: catgut implantation at acupoints plus antiepileptic drugs Comparison: antiepileptic drugs alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| antiepileptic drugs alone | catgut implantation at acupoints plus antiepileptic drugs | |||||

|

Seizure freedom (follow‐up: 2 months to 1 year) |

127 per 1000 | 192 per 1000 (118 to 309) | RR 1.51 (0.93 to 2.43) | 361 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (follow‐up: 2 months to 1 year) |

444 per 1000 | 630 per 1000 (475 to 840) | RR 1.42 (1.07 to 1.89) | 401 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Post‐treatment quality of life (QOLIE‐31 score, which has a range of 0‐100, with higher score indicates worse quality of life) (follow‐up: 3 months) |

The mean post‐treatment quality of life was 53.21 points. | The mean post‐treatment quality of life in the intervention group was 7.54 points lower (14.47 points lower to 0.61 points lower). | 120 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ||

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ dizziness (follow‐up: 3 months) |

160 per 1000 | 53 per 1000 (20 to 138) | RR 0.33 (0.13 to 0.86) | 120 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ malaise (follow‐up: 3 months) |

233 per 1000 | 117 per 1000 (51 to 268) | RR 0.50 (0.22 to 1.15) | 120 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ nausea (follow‐up: 3 months) |

140 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (12 to 164) | RR 0.33 (0.09 to 1.17) | 120 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ anorexia (follow‐up: 3 months) |

180 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (10 to 204) | RR 0.25 (0.06 to 1.13) | 120 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. Evidence from RCT downgraded by two levels because of high risk of bias in study design and imprecise result.

Summary of findings 7. Summary of findings: catgut implantation at acupoints versus valproate.

| Catgut implantation at acupoints compared with valproate for epilepsy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: participants with generalised epilepsy Settings: hospital inpatients and outpatients Intervention: catgut implantation at acupoints Comparison: valproate | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| valproate | catgut implantation at acupoints | |||||

|

Seizure freedom (follow‐up: 3 months to 1 year) |

82 per 1000 | 231 per 1000 (132 to 406) | RR 2.82 (1.61 to 4.94) | 381 (4) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (follow‐up: 3 months to 1 year) |

721 per 1000 | 945 per 1000 (677 to 1000) | RR 1.31 (0.94 to 1.84) | 381 (4) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Post‐treatment quality of life (QOLIE‐31 score, which has a range of 0‐200, with higher score indicates better quality of life) (follow‐up: 3 months) |

The mean post‐treatment quality of life across control groups ranged from 170.22 to 172.6 points. | The mean post‐treatment quality of life in the intervention group was 18.73 points higher (11.10 points higher to 26.36 points higher). | 100 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ||

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ dizziness (follow‐up: 3 months) |

160 per 1000 | 101 per 1000 (35 to 285) | RR 0.63 (0.22 to 1.78) | 100 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ malaise (follow‐up: 3 months) |

233 per 1000 | 214 per 1000 (109 to 425) | RR 0.92 (0.47 to 1.82) | 100 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ nausea (follow‐up: 3 months) |

140 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (2 to 157) | RR 0.14 (0.02 to 1.12) | 100 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

|

Frequency of adverse effects ‐ anorexia (follow‐up: 3 months) |

180 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (9 to 177) | RR 0.22 (0.05 to 0.98) | 100 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. Evidence from RCT downgraded by two levels because of high risk of bias in study design and imprecise result.

Background

Description of the condition

Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder with an estimated annual incidence of 50 per 100,000 and a prevalence of 5 to 10 per 1000 in developed countries (Sander 1996). About 2% to 3% of the general population will be given a diagnosis of epilepsy at some time in their lives (Hauser 1993), the majority of whom will go into remission. About 70% of patients with epilepsy become seizure free but up to 30% continue to have seizures despite treatment with adequate doses of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), that is they become drug resistant. Hence there is a constant search for newer modes of treatment. Furthermore, the commonly used AEDs can have adverse effects such as causing gingival hyperplasia; gastrointestinal disturbances (nausea, vomiting); osteoporosis, osteomalacia, and bone marrow toxicity; hepatotoxicity; nephrotoxicity; neurological symptoms (ataxia, dizziness, diplopia, somnolence); cognitive, mood and behavioural disturbances; endocrine dysfunction; and teratogenicity; as well as allergic reactions including skin rashes, toxic epidermal necrolysis or Steven Johnson syndrome (Holland 2001). Other treatments for epilepsy such as a ketogenic diet, use of a vagal nerve stimulator, and epilepsy surgery have their own limitations and complications. As a result, many people are turning to alternative complementary therapy for treatment of their condition and acupuncture is one of the popular options.

Description of the intervention

Acupuncture is a procedure in which specific body areas, the meridian points, are pierced with fine needles for therapeutic purposes. It is one of the major modalities of treatment in traditional Chinese medicine. In China its use can be traced back more than 2000 years (Wu 1996). Apart from the traditional needle acupuncture various forms of acupuncture have been developed, including electroacupuncture, laser acupuncture, acupressure, and catgut implantation at acupoints. Being a relatively simple, inexpensive and safe treatment, acupuncture has been well accepted by inhabitants in China and people worldwide who are of Chinese origin. Acupuncture is widely used by many Chinese practitioners in various neurological disorders as an alternative treatment approach (Johansson 1993). It is also increasingly practiced in some Western countries (NIH 1998).

How the intervention might work

Acupuncture involves complex theories of regulation of the five elements (fire, earth, metal, water, and wood), yin and yang, Qi, and blood and body fluids. By stimulating various meridian points disharmony and dysregulation of organ systems is corrected to relieve symptoms and restore natural internal homeostasis (Maciocia 1989). Many studies in animals and humans have demonstrated that acupuncture can cause multiple biological responses (Wang 2001). These responses can occur both locally or close to the site of application (Jansen 1989) and at a distance, mediated mainly by the sensory neurons to many structures that are within the central nervous system (Magnusson 1994). The result is activation of pathways affecting various physiological systems in the brain as well as in the periphery (Liu 2004; Middlekauff 2004; Sun 2001).

There are both anecdotal reports and animal studies that suggest acupuncture may inhibit seizures. In an experiment of penicillin‐induced epilepsy in rats electroacupuncture was found to inhibit seizures, possibly through decreasing neuronal and inducible nitric oxide synthase transcription in the hippocampus (Huang 1999; Yang 2000). Antagonism of gamma‐aminobutyric acid type A (GABA‐A) receptors was found to attenuate the antiepileptic effect of electroacupuncture, whilst electroacupuncture acted synergistically with the antagonists of non‐N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate (non‐NMDA) receptors (Liu 1997). Electroacupuncture may theoretically have an effect on epilepsy by increasing the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters (Liu 1995; Wu 1992) such as serotonin, GABA, or opioid peptides. Beneficial effects on human epilepsy have been reported in uncontrolled studies (Shi 1987; Yang 1990).

Why it is important to do this review

Reports on the effects of acupuncture on electroencephalographic recordings have been conflicting (Chen 1983; Kloster 1999) and it is unclear whether the existing evidence is scientifically rigorous enough to recommend acupuncture for routine use in people with epilepsy. We examined the efficacy and safety of acupuncture therapy in epilepsy in a systematic review of randomised controlled trials.

This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2006.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of acupuncture in people with epilepsy.

We investigated the following hypotheses.

Acupuncture can increase the probability of becoming seizure free.

Acupuncture can reduce the frequency and duration of seizures.

Acupuncture can improve quality of life.

Acupuncture is associated with adverse effects.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled clinical trials using truly random or quasi‐random allocation of treatment in the review.

We included studies comparing acupuncture with at least one control group that used no treatment, placebo treatment, sham treatment or AED.

Studies were single or double blind or unblinded.

We included parallel group or cross‐over designs.

Types of participants

People with an epilepsy syndrome of any type (Commission 1989) who were of any age and of either gender.

Types of interventions

We planned to include trials evaluating all forms of acupuncture therapy including acupressure, laser acupuncture, electroacupuncture or catgut implantation at acupoints in the review regardless of times of treatment and length of the treatment period. We included both traditional acupuncture in classical meridian points and contemporary acupuncture in non‐meridian or trigger points regardless of the source or methods of stimulation (for example, hand, needle, laser, electrical stimulation, or catgut implantation). Acupuncture could be given alone or as an add‐on to AEDs.

The control interventions that were considered included placebo acupuncture, sham acupuncture or AEDs. Placebo acupuncture refers to a needle attached to the skin surface (not penetrating the skin but at the same acupoint) (Furlan 1999). Sham acupuncture refers to a needle placed in an area close to, but not in, the acupuncture point (Furlan 1999) or subliminal skin electrostimulation via electrodes attached to the skin (SCSSS 1999).

We investigated the following treatment comparisons.

Acupuncture alone compared with no treatment.

Acupuncture alone compared with placebo or sham treatment or antiepileptic medication.

Acupuncture in addition to baseline AED compared with baseline AED alone.

Acupuncture in addition to baseline AED compared with placebo or sham treatment in addition to baseline AED.

Trials that only compared different forms of acupuncture were excluded since we did not intend to investigate whether one type of acupuncture was more effective than another. Trials that compared acupuncture in addition to herbal medicines or other alternative therapies with AED treatment were also excluded since such trial cannot resolve which component of the combination, that is acupuncture or herbs, is more effective than control treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Seizure freedom.

Satisfactory seizure control: 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

Absolute or percentage reduction in seizure frequency and duration.

Improved quality of life if assessed by validated, reliable scales.

Secondary outcomes

-

Incidence of adverse or harmful effects:

sedation;

cognitive side effects;

allergic reactions ‐ skin rashes, Steven Johnson syndrome.

Withdrawals due to side effects or lack of efficacy.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases.

Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialised Register (3 June 2013).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (2013, Issue 5) searched on 3 June 2013 using the search strategy set out in Appendix 1.

MEDLINE (Ovid) (1946 to 30 May 2013) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 2.

EMBASE (Ovid) (1947 to 4 June 2013) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 3

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (EBSCOhost) (1937 to 3 June 2013) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 4.

AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database) (EBSCOhost) (1985 to 3 June 2013) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 5.

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/ searched on 3 June 2013) using the search terms "epilep* AND acupuncture", and "seizure* AND acupuncture".

Chinese literature databases, including China Journals Full‐text Database, China Master thesis Full‐text Database, and China Doctor Dissertations Full‐text Database (1999 to 4 June 2013) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 6.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of all relevant papers for further studies. In addition, we contacted colleagues and experts in the field to ascertain any unpublished or ongoing studies. There were no language restrictions either in the search or inclusion of studies. We considered multiple publications reporting the same groups of patients or subsets as the same trial.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (Daniel Ka Leung Cheuk and Virginia Wong) independently assessed trials for inclusion. We resolved any disagreements between the two review authors by mutual discussion.

Data extraction and management

We extracted the following data, if available.

-

Study methods:

design (e.g. parallel or cross‐over design);

randomisation method (including list generation);

method of allocation concealment;

blinding method;

stratification factors.

-

Participants:

inclusion and exclusion criteria;

number (total and per group);

age and sex distribution;

seizure type and epilepsy syndrome;

duration of epilepsy;

etiology of epilepsy;

seizure frequency;

presence of neurological signs;

number and types of AEDs taken.

-

Intervention and control:

type of acupuncture;

details of treatment regimen including duration of treatment;

type of control;

details of control treatment including drug dosage;

washout period if cross‐over design.

-

Follow‐up data:

duration of follow‐up;

dates of treatment withdrawal and reasons for treatment withdrawal;

withdrawal rates.

-

Outcome data:

as described above.

-

Analysis data:

methods of analysis (intention‐to‐treat and per protocol analysis);

comparability of groups at baseline (yes or no);

statistical techniques.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (Daniel Ka Leung Cheuk and Virginia Wong) independently assessed the risk of bias in each included study according to the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011, section 8.5.1). We resolved any disagreements between the two review authors by mutual discussion.

For each study we assessed the following items to see whether:

the allocation sequence was adequately generated ('sequence generation');

the allocation was adequately concealed ('allocation concealment');

knowledge of the allocated interventions was adequately prevented during the study ('blinding'), for participants, personnel and outcome assessors;

incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed;

reports of the study were free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting;

the study was apparently free of other problems that could put it at high risk of bias.

We allocated each domain one of three possible categories: 'Yes' for low risk of bias, 'No' for high risk of bias, and 'Unclear' where the risk of bias was uncertain or unknown.

Measures of treatment effect

We used risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for binary outcomes (seizure freedom, 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency, frequency of adverse effects, and withdrawal due to adverse effects), and mean differences (MD) with 95% CI for continuous outcomes (quality of life, absolute or percentage reduction in seizure frequency and duration). To account for multiple statistical testing we used 99% confidence intervals for the frequency of adverse effects if there were several adverse effects reported.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by comparing the distribution of important participant factors between trials (age, gender, seizure type, duration of epilepsy, number of AEDs taken at time of randomisation) and trial factors (randomisation concealment, blinding, losses to follow‐up). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by the I2 statistic (Higgins 2011, section 9.5.2), where a value greater than 50% was considered to indicate substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use funnel plots (effect size against standard error) if sufficient studies (more than five) were found. Asymmetry could be due to publication bias but could also be due to a relationship between trial size and effect size. In the event that a relationship was found, we planned to examine the clinical diversity of the studies (Higgins 2011, section 10.4). However, there were no more than five studies reporting the same outcome and therefore we did not draw a funnel plot.

Data synthesis

Where the interventions were the same or similar enough, and if there was no important clinical heterogeneity, we synthesised the results in a meta‐analysis. If no significant statistical heterogeneity was present we synthesised the data using a fixed‐effect model, otherwise we used a random‐effects model for analysis. The analyses included all participants in the treatment groups to which they were allocated (that is intention‐to‐treat analyses) as far as possible.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to assess the impact of important patient characteristics including seizure type, duration and aetiology of epilepsy and presence of neurological signs upon the outcome, although insufficient data were available to do so.

Sensitivity analysis

We also planned to undertake sensitivity analyses including: (i) all studies; (ii) only those not having a high risk of bias. However, since all included studies had a high risk of bias, we did not perform a sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

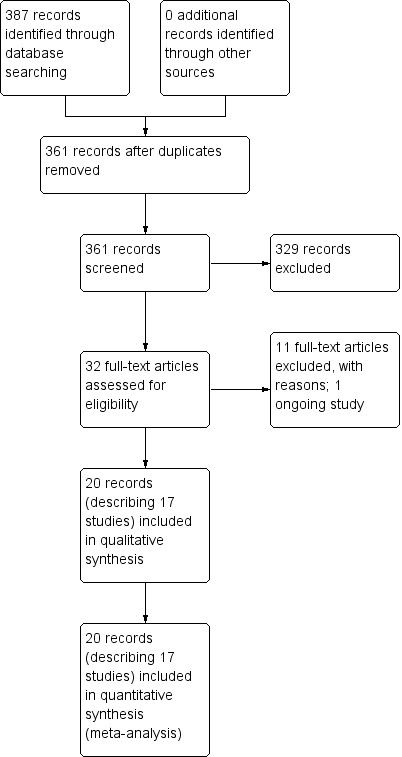

We obtained a total of 387 results from the electronic search of the databases. We did not identify any additional articles from references of relevant articles. After we removed duplicates, 361 articles remained. We screened the titles and abstracts of these against the inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection and excluded 329 references based on titles or abstracts alone. We obtained the full texts of the remaining 32 articles and assessed these for eligibility. We excluded 11 of these studies, with the reasons stated in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. One of the remaining studies is ongoing and is described in the table Characteristics of ongoing studies. The remaining 17 studies described by 20 papers (three studies were published in two papers each) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and we included these in the review (described in the table Characteristics of included studies). The flow of records is summarised in Figure 1. This included one new study in the current updated review (June 2013).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Seventeen randomised controlled trials met the inclusion criteria (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Kloster 1999; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Ma 2001; Mao 2011; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003; Yi 2009; Yu 1999; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2004; Zhuang 2006). Details of the included studies are summarised below.

Three of the included trials were published in two records (Kloster 1999; Ma 2001; Peng 2003). One trial was performed in Norway and was published in English (Kloster 1999) while the remaining 16 trials were performed in China and published in Chinese (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Ma 2001; Mao 2011; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003; Yi 2009; Yu 1999; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2004; Zhuang 2006); they were translated for this review. The 17 included trials recruited a total of 1538 people with epilepsy. All trials recruited participants in the hospital setting. Five trials recruited hospital inpatients and outpatients (Li 2007; Ma 2001; Shi 2001; Zhang 2006b; Zhuang 2006), while four trials recruited outpatients only (Kloster 1999; Mao 2011; Yi 2009; Yu 1999) and eight trials did not specify the patient setting (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Leng 2000; Peng 2003; Xiong 2003; Zhang 2006a; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2004). One trial included only adults (Kloster 1999), four trials included only children (Ma 2001; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003), and the remaining 12 trials included both adults and children (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Mao 2011; Yi 2009; Yu 1999; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2004; Zhuang 2006). Four trials included patients with both partial and generalized epilepsy (Kloster 1999; Yu 1999; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2004), while 12 trials included only patients with generalized epilepsy (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Ma 2001; Mao 2011; Peng 2003; Xiong 2003; Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhuang 2006), and one trial included only patients with childhood absence epilepsy (Shi 2001). The duration of epilepsy was highly variable in the included trials, ranging from three days to over 30 years. The baseline seizure frequency varied from once every four to six months to many times a day. Aetiologies of epilepsy in the patients were reported in only four trials, which encompassed a wide variety in three of the trials (Ma 2001; Xiong 2003; Zhuang 2004) and only childhood absence in one trial (Shi 2001). Neurological signs were not mentioned in any of the trials. One trial reported that patients were taking a mean of two AEDs before entering the trial (Kloster 1999) and one trial excluded patients who were currently using an AED (Peng 2003). One trial summarised what kinds of drugs patients were taking without mentioning the average number of AEDs that patients required before entering the trial (Xiong 2003). Two trials simply mentioned that some patients were taking AEDs without giving details (Ma 2001; Yu 1999). The remaining 12 trials did not mention anything about the drug history of the participants (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Mao 2011; Shi 2001; Yi 2009; Zhou 2000; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhuang 2004; Zhuang 2006).

The type of acupuncture used in the included trials varied. Traditional needle acupuncture was used in six trials (Ma 2001; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003; Yi 2009; Yu 1999; Zhou 2000) and catgut implantation into acupoints was used in eight trials (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Mao 2011; Peng 2003; Zhuang 2004; Zhuang 2006). Two trials included two treatment groups, catgut implantation in one group and needle acupuncture in the other (Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b). One trial combined traditional needle acupuncture and electroacupuncture in the treatment group (Kloster 1999). The acupoints chosen were highly variable in the included trials . While the chosen acupoints were fixed and universally applied to all patients in eight trials (Leng 2000; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003; Yu 1999; Zhang 2006a; Zhuang 2004; Zhuang 2006), the remaining nine trials (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Kloster 1999; Li 2007; Ma 2001; Mao 2011; Yi 2009; Zhang 2006b; Zhou 2000) allowed some flexibility in the use of additional acupoints on top of the protocol acupoints set for all patients.

All 17 included trials used a parallel group, randomised controlled design. Two trials had two intervention groups (catgut implantation in acupoints with or without valproate, and needle acupuncture with or without valproate) and one control group (valproate alone) (Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b). One trial (Xiong 2003) employed two control groups (carbamazepine in one control group and Chinese herbs in the other), while the other 16 trials used only one control group. The controls chosen were sham acupuncture in one trial (Kloster 1999), Chinese herbal tablet in one trial (Ma 2001), phenytoin in two trials (Yu 1999; Zhou 2000), phenobarbital plus phenytoin in one trial (Zhuang 2004), and valproate in 12 trials (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Mao 2011; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhuang 2006). The duration of treatment ranged from 7.5 weeks to 12 months and the duration of follow‐up ranged from 12 weeks to 12 months.

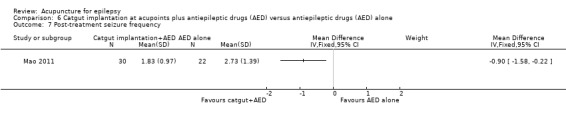

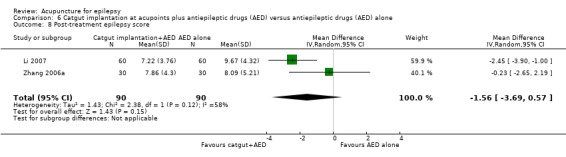

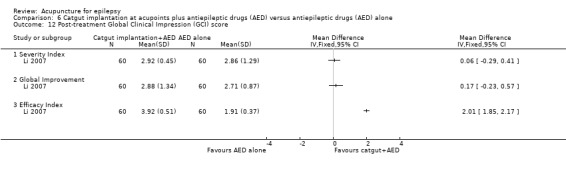

Ten trials used freedom from seizures as an outcome (Deng 2001a; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Mao 2011; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhuang 2006). Fifteen trials reported the number of patients with good (75% or over), moderate (50% to 74%), or mild (25% to 49%) reductions in seizure frequency as outcomes (Deng 2001a; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Ma 2001; Mao 2011; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003; Yi 2009; Yu 1999; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2004; Zhuang 2006). Two trials reported post‐treatment seizure frequency as an outcome (Mao 2011; Zhou 2000). Two trials reported good (75% or over) or moderate (50% to 74%) reductions in seizure duration as outcomes (Ma 2001; Xiong 2003). Seven trials reported epilepsy score (Han 2008; Li 2007; Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a; Zhuang 2006; Zhang 2006b; Zhuang 2006) and four trials reported different degrees of epilepsy score improvement (Han 2008; Li 2007; Yi 2009; Zhang 2006b) as outcomes, but the epilepsy score was not clearly defined in any of the trials. One trial (Kloster 1999) used the percentage reduction in seizure frequency; percentage increase in seizure‐free weeks; and the numbers of patients who had their seizure frequency improved, remain static, or worsened as outcomes. This trial also reported withdrawal due to lack of efficacy (Kloster 1999). Four trials reported the quality of life (QOL) of the patients as an outcome (Kloster 1999; Li 2007; Yi 2009; Zhang 2006b). One trial also reported Global Clinical Improvement scores (Li 2007). Seven trials reported post‐treatment electroencephalogram (EEG) abnormality (Deng 2001a; Li 2007; Ma 2001; Xiong 2003; Yi 2009; Zhang 2006b) or degrees of EEG improvement (Kloster 1999; Ma 2001) as outcomes. Four trials reported adverse effects of treatment (Kloster 1999; Li 2007; Yi 2009; Zhang 2006b).

Excluded studies

The reasons for exclusion of the 11 studies were: non‐epilepsy population (Luo 2004; Yi 2005), comparisons of different acupuncture methods (Li 2004; Lin 2001; Xu 2003), acupuncture plus other treatment against acupuncture (Kuang 1996), acupuncture plus other treatment against AEDs or a different treatment (Chui 2006; Deng 2001b; Han 2005; Wu 2008; Xu 2004).

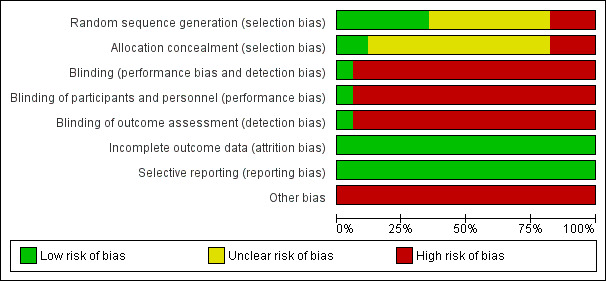

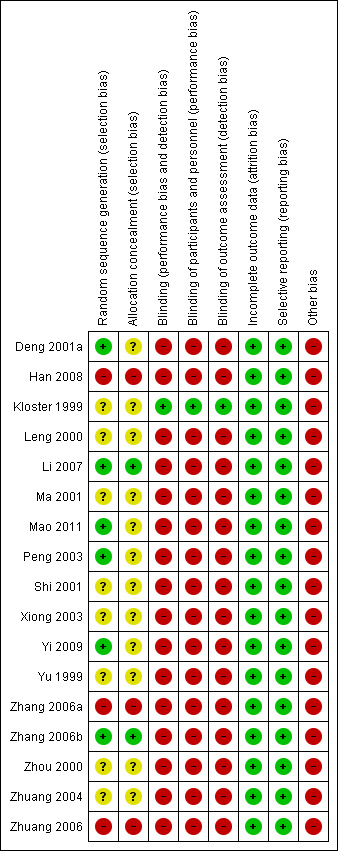

Risk of bias in included studies

All 17 iIncluded studies were of poor methodological quality with at least one area at high risk of bias. These findings are summarised in the table Characteristics of included studies, Figure 2 and Figure 3, and described below.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Although all trials mentioned that the patients were randomly allocated to the intervention and control groups, the method of randomisation was not described in eight trials (Kloster 1999; Leng 2000; Ma 2001; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003; Yu 1999; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2004) and sequence generation was considered to be inadequate in three trials (Han 2008; Zhang 2006a; Zhuang 2006) since they allocated participants according to sequence of attendance. Allocation concealment was not reported in 12 trials (Deng 2001a; Kloster 1999; Leng 2000; Ma 2001; Mao 2011; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003; Yi 2009; Yu 1999; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2004) and was considered inadequate in three trials (Han 2008; Zhang 2006a; Zhuang 2006).

Blinding

Sixteen of the included trials did not blind the participants, the personnel, or the outcome assessors (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Ma 2001; Mao 2011; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003; Yi 2009; Yu 1999; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2004; Zhuang 2006). Only one trial blinded all parties (Kloster 1999).

Incomplete outcome data

There were no dropouts in 15 trials (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Ma 2001; Mao 2011; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003; Yu 1999; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2004; Zhuang 2006) and dropouts were accounted for in one trial (Kloster 1999) as the dropouts were mentioned to be due to lack of efficacy requiring change of AED. Dropouts were not explained in one trial (Yi 2009). Among those trials which reported dropouts, the number was small and we considered it unlikely to result in significant bias.

Selective reporting

In all included trials, all predefined or expected outcomes were reported and selective reporting was not evident.

Other potential sources of bias

Twelve trials (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Leng 2000; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003; Yi 2009; Yu 1999; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhuang 2004; Zhuang 2006) did not provide data on important baseline characteristics of the intervention and control groups to judge the comparability of the two groups. In three trials (Kloster 1999; Ma 2001; Zhou 2000) the authors claimed that the two groups were comparable at baseline but the data they provided suggested otherwise since one group seemed to have more frequent seizures than the other. Furthermore, the acupuncture treatment in 12 trials was not standardised (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Kloster 1999; Li 2007; Ma 2001; Mao 2011; Yi 2009; Yu 1999; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2006). Eleven trials relied on the discretion of the clinician in choosing acupoints (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Kloster 1999; Li 2007; Ma 2001; Mao 2011; Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2006) and in two trials the number of courses of acupuncture or the interval between courses was variable (Deng 2001a; Yu 1999). The control treatment was also not standardised for two trials. In one trial, whether valproate or carbamazepine was used in the control patients depended on the clinician's judgement and preference (Deng 2001a). In another trial, the dose of phenytoin used was variable (Zhou 2000). In 16 studies (Deng 2001a; Han 2008; Leng 2000; Li 2007; Ma 2001; Mao 2011; Peng 2003; Shi 2001; Xiong 2003; Yi 2009; Yu 1999; Zhang 2006a; Zhang 2006b; Zhou 2000; Zhuang 2004; Zhuang 2006) no sham or placebo control was used and the placebo effect might have caused bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7

All effect sizes were calculated with the fixed‐effect model unless otherwise specified.

Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs compared with Chinese herbs alone

Two trials compared needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs with Chinese herbs alone (Ma 2001; Xiong 2003). Although the Chinese herbs used were different in the two studies, they were the same in the treatment and control groups in each study. Therefore, unless significant interaction between the effects of acupuncture and the particular type of Chinese herbs was present, it was expected that the comparison of outcomes between the treatment and control groups represented the net effect of acupuncture. Where the described outcomes were comparable, we combined the results in a meta‐analysis. We found that apart from using different acupoints and different control herbs, there was no significant clinical heterogeneity between the two trials. Both trials included only paediatric patients with generalized epilepsy of widely differing durations. There was also no significant statistical heterogeneity in the various outcomes reported and hence the results were combined in meta‐analyses using the fixed‐effect model. Results on adverse effects and the available primary outcomes are summarised in Table 1.

Primary outcomes

Seizure freedom

Neither of the trials (Ma 2001; Xiong 2003) reported our predetermined primary outcome of seizure freedom.

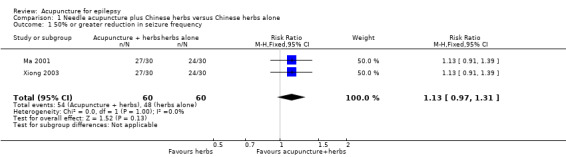

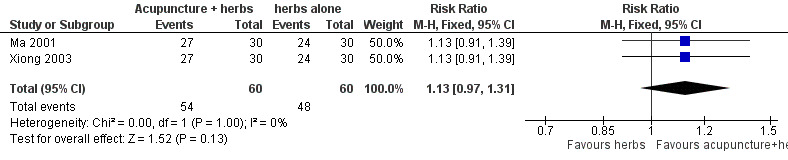

A 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

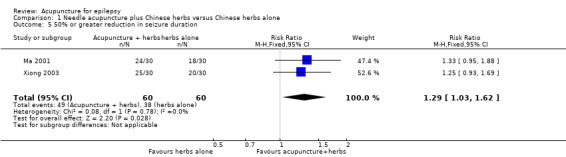

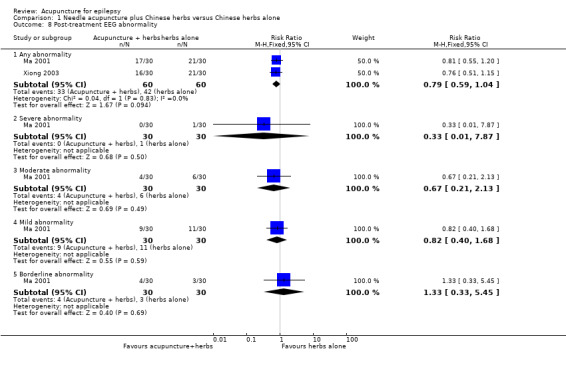

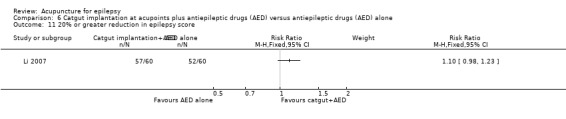

Both trials (Ma 2001; Xiong 2003) showed a mild positive effect of acupuncture in achieving 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (pooled RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.31, 2 studies, 120 participants) but this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.13) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs versus Chinese herbs alone, Outcome 1 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs versus Chinese herbs alone, outcome: 1.1 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

Absolute or percentage reduction in seizure frequency and duration

The two trials (Ma 2001; Xiong 2003) did not report absolute or percentage reduction in seizure frequency or duration.

Quality of life

The two trials (Ma 2001; Xiong 2003) did not report quality of life changes.

Secondary outcomes

The two trials (Ma 2001; Xiong 2003) did not report adverse effects or withdrawal due to adverse effects or lack of efficacy.

Additional outcomes

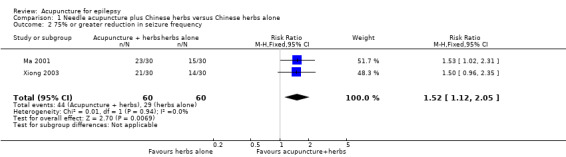

A 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

We found a statistically significant difference (P = 0.007) between the treatment and control groups in the number of patients with 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (pooled RR 1.52, 95% CI 1.12 to 2.05, 2 studies, 120 participants) favouring acupuncture treatment (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs versus Chinese herbs alone, Outcome 2 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

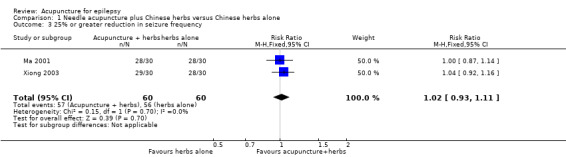

A 25% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

There was no significant difference (P = 0.7) between the treatment and the control groups in the number of patients with 25% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (pooled RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.11, 2 studies, 120 participants) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs versus Chinese herbs alone, Outcome 3 25% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

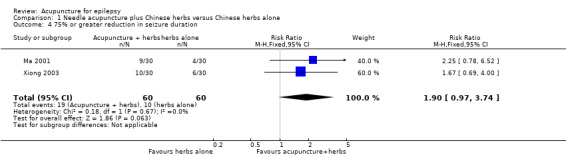

A 75% or greater reduction in seizure duration

There was no significant difference (P = 0.06) between the treatment and the control groups in the number of patients with 25% or greater reduction in seizure duration (pooled RR 1.90, 95% CI 0.97 to 3.74, 2 studies, 120 participants) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs versus Chinese herbs alone, Outcome 4 75% or greater reduction in seizure duration.

A 50% or greater reduction in seizure duration

The treatment group was significantly more likely (P = 0.03) to have 50% or greater reduction in seizure duration compared with the control group (pooled RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.62, 2 studies, 120 participants) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs versus Chinese herbs alone, Outcome 5 50% or greater reduction in seizure duration.

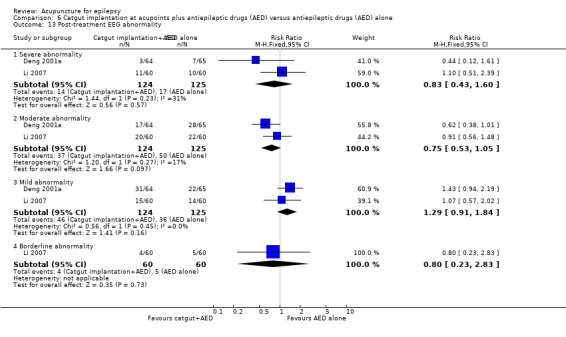

Post‐treatment EEG abnormality

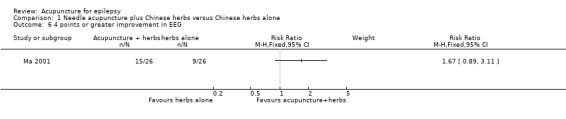

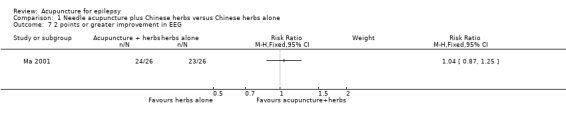

One study (Ma 2001) graded EEG abnormalities using a scoring system, with a higher score representing more severe abnormality. There was no significant difference between the treatment and the control groups in the proportion of patients with 4 points or greater improvement in EEG abnormality (RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.89 to 3.11, 1 study, 52 participants, P = 0.11) (Analysis 1.6), or 2 points or greater improvement in EEG abnormality (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.25, 1 study, 52 participants, P = 0.64) (Analysis 1.7). Two studies (Ma 2001; Xiong 2003) classified the EEG abnormalities into different grades (borderline, mild, moderate, and severe abnormality). There was no statistically significant difference between the treatment and the control groups in the number of patients with different degrees of post‐treatment EEG abnormality (any abnormality: pooled RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.04, 2 studies, 120 participants, P = 0.09; severe abnormality: RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.01 to 7.87, 1 study, 60 participants, P = 0.5; moderate abnormality: RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.21 to 2.13, 1 study, 60 participants, P = 0.49; mild abnormality: RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.68, 1 study, 60 participants, P = 0.59; and borderline abnormality: RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.33 to 5.45, 1 study, 60 participants, P = 0.69) (Analysis 1.8).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs versus Chinese herbs alone, Outcome 6 4 points or greater improvement in EEG.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs versus Chinese herbs alone, Outcome 7 2 points or greater improvement in EEG.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbs versus Chinese herbs alone, Outcome 8 Post‐treatment EEG abnormality.

Needle acupuncture plus valproate compared with valproate alone

Two trials compared needle acupuncture plus valproate with valproate alone (Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a). Apart from using different acupoints there was no significant clinical heterogeneity between the two trials. Both trials recruited patients with generalized epilepsy. The participants in the trial by Zhang 2006a appeared to have a longer duration of epilepsy than those in Yi 2009. Results on adverse effects and the available primary outcomes are summarised in Table 2.

Primary outcomes

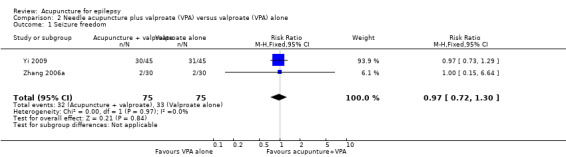

Seizure freedom

The pooled result of the two trials (Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a) showed no significant difference (P = 0.84) in seizure freedom between the treatment and the control groups (pooled RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.30, 2 studies, 150 participants) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, Outcome 1 Seizure freedom.

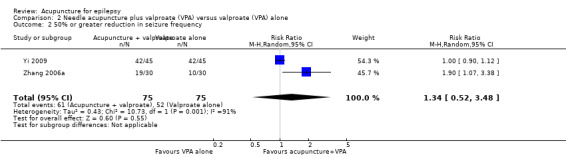

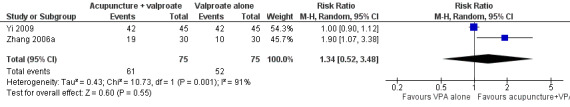

A 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

There was also no significant difference (P = 0.55) in the number of patients achieving 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (pooled RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.52 to 3.48, random‐effects model, 2 studies, 150 participants) (Analysis 2.2; Figure 5). However, there was a high degree of statistical heterogeneity between the trials (I2 = 91%). The included trials differed in the age of the patients, duration of epilepsy, and acupuncture methods.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, Outcome 2 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, outcome: 2.2 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

Absolute or percentage reduction in seizure frequency and duration

The two trials (Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a) did not report absolute or percentage reduction in seizure frequency or duration.

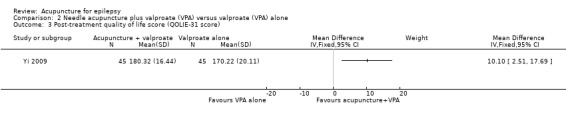

Quality of life

One trial (Yi 2009) reported that the treatment group had a significantly better (P = 0.009) quality of life after treatment compared with the control group by the QOLIE‐31 score (MD 10.10, 95% CI 2.51 to 17.69, 1 study, 90 participants) (Analysis 2.3). Higher score indicated better quality of life; a positive MD indicated benefit of the treatment compared with control.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, Outcome 3 Post‐treatment quality of life score (QOLIE‐31 score).

Secondary outcomes

Frequency of adverse effects

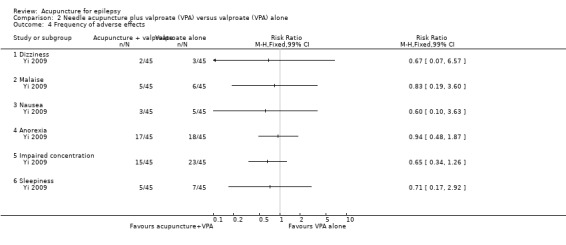

One trial (Yi 2009) with 90 participants reported the frequencies of several adverse effects and found no statistically significant differences between the treatment and the control groups (dizziness: RR 0.67, 99% CI 0.07 to 6.51, P = 0.65; malaise: RR 0.83, 99% CI 0.19 to 3.60, P = 0.75; nausea: RR 0.60, 99% CI 0.10 to 3.63, P = 0.47; anorexia: RR 0.94, 99% CI 0.48 to 1.87, P = 0.83; impaired concentration: RR 0.65, 99% CI 0.34 to 1.26, P = 0.10; and sleepiness: RR 0.71, 99% CI 0.17 to 2.92, P = 0.54) (Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, Outcome 4 Frequency of adverse effects.

Withdrawals due to adverse effects or lack of efficacy

The two trials did not report any withdrawals due to adverse effects or lack of efficacy (Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a).

Additional outcomes

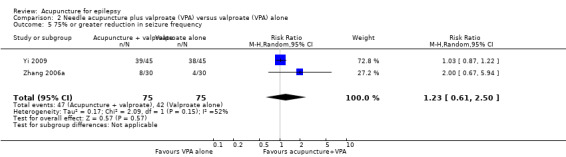

A 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

We found no significant difference (P = 0.57) between the treatment and control groups in the number of patients with 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency when the results of the two trials (Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a) were combined (pooled RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.50, random‐effects model, 2 studies, 150 participants) (Analysis 2.5). However, there was moderate statistical heterogeneity between the trials (I2 = 52%). The included trials differed in the age of the patients, duration of epilepsy, and acupuncture methods.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, Outcome 5 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

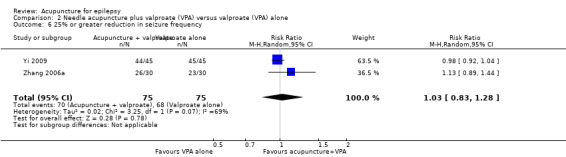

A 25% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

There was also no significant difference (P = 0.78) between the treatment and control groups in the number of patients with 25% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (pooled RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.28, random‐effects model, 2 studies, 150 participants) (Analysis 2.6). There was moderate statistical heterogeneity between the trials (I2 = 68%). The included trials differed in the age of the patients, duration of epilepsy, and acupuncture methods.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, Outcome 6 25% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

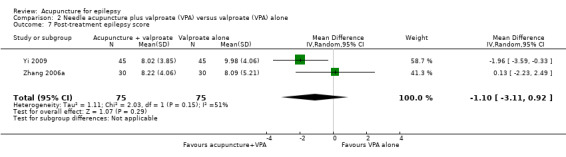

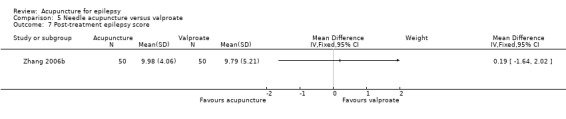

Post‐treatment epilepsy score

Both trials (Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a) reported the post‐treatment epilepsy score (a higher score indicated more severe epilepsy), which was not significantly different (P = 0.29) between the treatment and the control group when the results of the trials (Yi 2009; Zhang 2006a) were combined (pooled MD ‐1.10, 95% CI ‐3.11 to 0.13, random‐effects model, 2 studies, 150 participants) (Analysis 2.7). A negative MD indicated benefit of treatment compared with control. However, there was moderate statistical heterogeneity between the trials (I2 = 51%). The included trials differed in the age of the patients, duration of epilepsy, and acupuncture methods.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, Outcome 7 Post‐treatment epilepsy score.

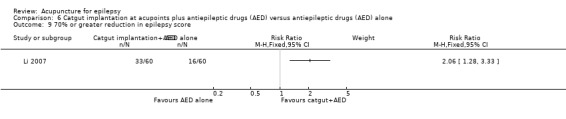

A 70% or greater reduction in epilepsy score

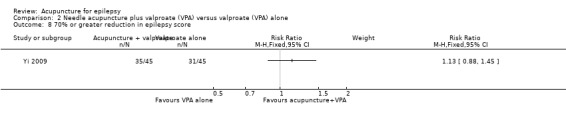

One trial (Yi 2009) reported no significant difference (P = 0.34) between the treatment and the control groups in the number of patients with 70% or greater reduction in epilepsy score (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.45, 1 study, 90 participants) (Analysis 2.8).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, Outcome 8 70% or greater reduction in epilepsy score.

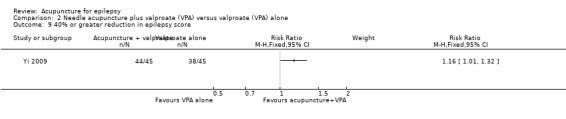

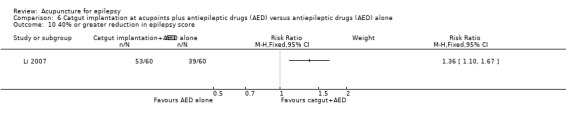

A 40% or greater reduction in epilepsy score

The same trial (Yi 2009) reported that the treatment group was significantly more likely (P = 0.03) to have 40% or greater improvement in epilepsy score compared with the control group (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.32, 1 study, 90 participants) (Analysis 2.9).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, Outcome 9 40% or greater reduction in epilepsy score.

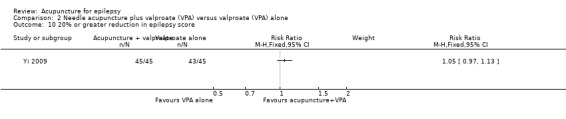

A 20% or greater reduction in epilepsy score

The same trial (Yi 2009) reported no significant difference (P = 0.24) between the treatment and the control groups in the number of patients with 20% or greater reduction in epilepsy score (pooled RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.13, 1 study, 90 participants) (Analysis 2.10).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, Outcome 10 20% or greater reduction in epilepsy score.

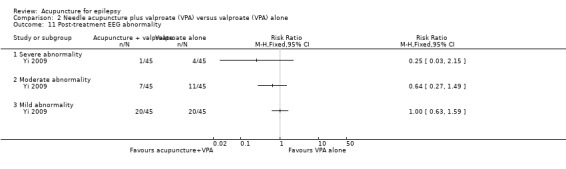

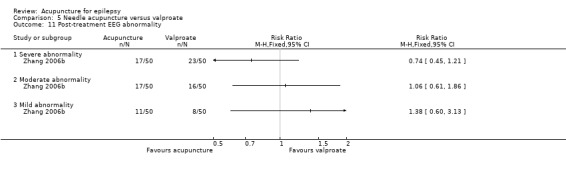

Post‐treatment EEG abnormality

This trial (Yi 2009) with 90 participants also reported post‐treatment EEG abnormalities and found no significant difference between the treatment and the control groups (severe abnormality: RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.15, P = 0.21; moderate abnormality: RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.49, P = 0.3; mild abnormality: RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.59, P = 1.0) (Analysis 2.11).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Needle acupuncture plus valproate (VPA) versus valproate (VPA) alone, Outcome 11 Post‐treatment EEG abnormality.

Needle acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture

Only one trial used sham acupuncture as control treatment (Kloster 1999). Results on adverse effects and the available primary outcomes are summarised in Table 3.

Primary outcomes

Seizure freedom

This trial (Kloster 1999) did not report seizure freedom.

A 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

This trial (Kloster 1999) also did not report the number of patients with 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

Percentage reduction in seizure frequency

The percentage reduction in seizure frequency was reported to be higher in the treatment group (median 45%, 18 participants) compared with the control group (median 20%, 16 participants) but this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.38) (Analysis 3.1). Since no mean or standard deviation (SD) was reported, we could not perform a re‐analysis.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Needle acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, Outcome 1 Percentage reduction in seizure frequency.

| Percentage reduction in seizure frequency | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Treatment | Control |

| Kloster 1999 | median 45% (n=18) | median 20% (n=16) |

Quality of life

This trial (Kloster 1999) reported no significant difference (P = 0.55) in quality of life improvement between the treatment and the control groups (MD ‐3.4, 95% CI ‐14.45 to 7.65, 1 study, 22 participants) (Analysis 3.2). The authors also did not find any significant differences between the treatment and the control groups in any of the 17 subscores of the various items in the questionnaire.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Needle acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, Outcome 2 Improvement in quality of life score (QOLIE‐89 score).

Secondary outcomes

Frequency of adverse effects

The included trial (Kloster 1999) reported that a number of participants in the trial experienced adverse effects of treatment, such as changes in the sense of well‐being, sleep, bowel movements, micturition, menstruation, nausea and vomiting. However, the frequencies of their occurrence and the treatment groups these patients were allocated to were not reported.

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy

This trial (Kloster 1999) reported dropouts due to lack of efficacy and there was no significant difference (P = 0.73) between the treatment and the control groups (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.25 to 7.00, 1 study, 34 participants) (Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Needle acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, Outcome 3 Withdrawal due to lack of efficacy.

Additional outcomes

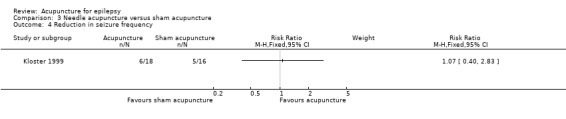

Reduction in seizure frequency

Six out of 18 patients in the treatment group compared with five out of 16 in the control group had fewer seizures on follow‐up, which was not significantly different (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.40 to 2.83, 1 study, 34 participants, P = 0.9) (Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Needle acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, Outcome 4 Reduction in seizure frequency.

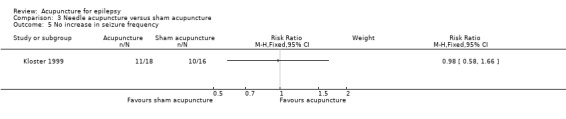

No increase in seizure frequency

Similarly, the numbers of patients without an increase in seizures on follow‐up were not significantly different (P = 0.93) between the treatment and the control groups (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.66, 1 study, 34 participants) (Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Needle acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, Outcome 5 No increase in seizure frequency.

Percentage increase in seizure‐free weeks

The percentage increase in seizure‐free weeks was reported to be lower in the treatment group (median 50%, 18 participants) compared with the control group (median 100%, 16 participants) (Analysis 3.6). However, no statistical test was performed and therefore we were uncertain whether the difference was statistically significant, or not. Since no mean or SD was reported we did not perform a re‐analysis.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Needle acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, Outcome 6 Percentage increase in seizure‐free weeks.

| Percentage increase in seizure‐free weeks | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Treatment | Control |

| Kloster 1999 | median 50% (n=18) | median 100% (n=16) |

Improvement in EEG abnormality

This trial (Kloster 1999) reported that there was no difference between the two groups in changes in EEG abnormality. However, no further data were provided.

Needle acupuncture compared with phenytoin

Two trials compared needle acupuncture with phenytoin (Yu 1999; Zhou 2000). The acupuncture regimen and acupoints chosen were different in these two trials. Otherwise the trials appeared similar. Results on adverse effects and the available primary outcomes are summarised in Table 4.

Primary outcomes

Seizure freedom

Neither of the trials (Yu 1999; Zhou 2000) reported our predetermined primary outcome of seizure freedom.

A 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

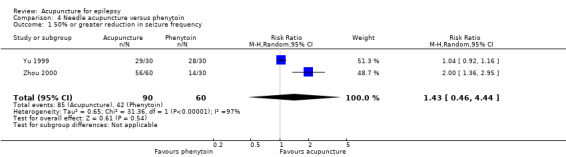

The combined results of the two trials (Yu 1999; Zhou 2000) showed no significant difference (P = 0.54) in the number of participants with 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (pooled RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.46 to 4.44, random‐effects model, 2 studies, 150 participants) (Analysis 4.1). However, the two trials exhibited very high statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 97%). The included trials differed in acupuncture methods.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Needle acupuncture versus phenytoin, Outcome 1 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

Absolute or percentage reduction in seizure frequency and duration

The two trials (Yu 1999; Zhou 2000) did not report absolute or percentage reduction in seizure frequency or duration.

Quality of life

The two trials (Yu 1999; Zhou 2000) also did not report quality of life changes.

Secondary outcomes

The two trials (Yu 1999; Zhou 2000) did not report adverse effects or dropouts due to adverse effects or lack of efficacy.

Additional outcomes

A 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

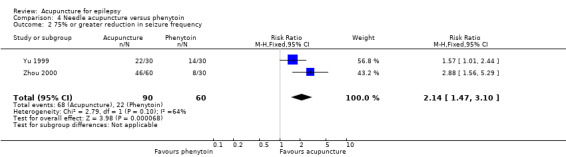

There were significantly more patients in the treatment group who achieved 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (pooled RR 2.14, 95% CI 1.47 to 3.1, 2 studies, 150 participants, P < 0.0001) (Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Needle acupuncture versus phenytoin, Outcome 2 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

A 25% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

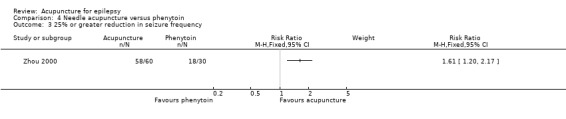

One study (Zhou 2000) also reported significantly more patients in the treatment group who achieved 25% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.17, 1 study, 90 participants, P = 0.0002) (Analysis 4.3).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Needle acupuncture versus phenytoin, Outcome 3 25% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

Post‐treatment seizure frequency

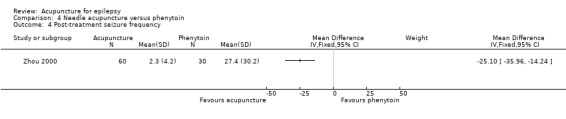

The same trial (Zhou 2000) reported a significantly lower seizure frequency after treatment (MD ‐25.1 per year, 95% CI ‐35.96 to ‐14.24 per year, 1 study, 90 participants, P < 0.00001) (Analysis 4.4).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Needle acupuncture versus phenytoin, Outcome 4 Post‐treatment seizure frequency.

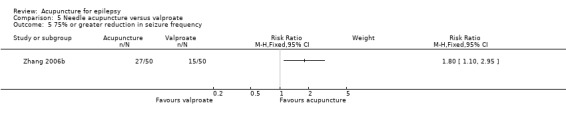

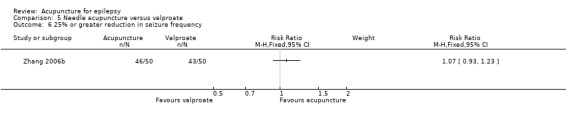

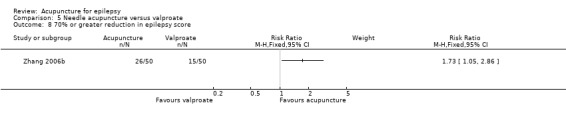

Needle acupuncture compared with valproate

Two trials compared needle acupuncture with valproate (Shi 2001; Zhang 2006b). One trial recruited patients with childhood absence epilepsy (Shi 2001) while the other trial recruited patients aged 15 to 60 years with generalized tonic‐clonic epilepsy (Zhang 2006b). Their acupuncture protocols were different. Results on adverse effects and the available primary outcomes are summarised in Table 5.

Primary outcomes

Seizure freedom

The pooled result of the two trials (Shi 2001; Zhang 2006b) showed no significant difference (P = 0.08) in seizure freedom between the treatment and the control groups (RR 1.75, 95% CI 0.93 to 3.27, 2 studies, 180 participants) (Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Needle acupuncture versus valproate, Outcome 1 Seizure freedom.

A 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

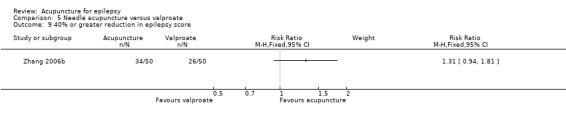

There were significantly more patients in the treatment group who achieved 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (pooled RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.66, 2 studies, 180 participants, P = 0.02) (Analysis 5.2).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Needle acupuncture versus valproate, Outcome 2 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.