Abstract

Introduction

Arterial Hypertension (HT) has been described as a common comorbidity and independent risk factor of short-term outcome in COVID-19 patients. However, data regarding the risk of new-onset HT during the post-acute phase of COVID-19 are scant.

Aim

We assess the risk of new-onset HT in COVID-19 survivors within one year from the index infection by a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available data.

Methods

Data were obtained searching MEDLINE and Scopus for all studies published at any time up to February 11, 2023, and reporting the long-term risk of new-onset HT in COVID-19 survivors. Risk data were pooled using the Mantel–Haenszel random effects models with Hazard ratio (HR) as the effect measure with 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using I2 statistic.

Results

Overall, 19,293,346 patients (mean age 54.6 years, 54.6% males) were included in this analysis. Of them, 758,698 survived to COVID-19 infection. Over a mean follow-up of 6.8 months, new-onset HT occurred to 12.7 [95% CI 11.4–13.5] out of 1000 patients survived to COVID-19 infection compared to 8.17 [95% CI 7.34–8.53] out of 1000 control subjects. Pooled analysis revealed that recovered COVID-19 patients presented an increased risk of new-onset HT (HR 1.70, 95% CI 1.46–1.97, p < 0.0001, I2 = 78.9%) within seven months. This risk was directly influenced by age (p = 0.001), female sex (p = 0.03) and cancer (p < 0.0001) while an indirect association was observed using the follow-up length as moderator (p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that new-onset HT represents an important post-acute COVID-19 sequelae.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40292-023-00574-5.

Keywords: COVID-19, Long COVID, Arterial hypertension, Follow-up

Introduction

Since the beginning of COVID-19 outbreak, arterial hypertension (HT) was recognized as one of the most common comorbidities in COVID-19 patients as well as an independent predictor of short-term mortality and severe disease [1–4]. Recent analyses have demonstrated an increased risk of cardiovascular sequelae after COVID-19 recovery compared to the general population not exposed to SARS-CoV-2 infection [5–9]. However, data regarding the risk of development new-onset HT as a post-acute COVID-19 sequelae remain scant. Aim of the present manuscript is to assess the risk of new-onset HT in COVID-19 recovered patients by performing a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available data.

Methods

Study Design

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline (Supplementary file 1) [10]. Data were obtained searching MEDLINE and Scopus for all studies published at any time up to February 11, 2023, and reporting the risk of new-onset HT in COVID-19 recovered patients diagnosed between 4 months (minimum follow-up length of revised investigations) and a maximum of 12 months post discharge (maximum follow-up length of revised studies) after the infection. The diagnosis of new-onset HT was performed after reviewing the clinical records of enrolled subjects using the ICD-10 codes I10-I16. In the revised manuscripts, this group of patients were matched and compared to contemporary cohorts, defined as subjects who did not experience the SARS-CoV-2 infection and developed a pericarditis in the same follow-up period.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The selection of studies included in our analysis was independently conducted by two authors (M.Z., C.B.) in a blinded fashion. Any discrepancies in study selection were resolved by consulting a third author (G.R.). The following MeSH terms were used for the search: “Arterial Hypertension” AND “COVID-19 sequelae” OR “Arterial Hypertension” AND “COVID-19”. Moreover, we searched the bibliographies of the target studies for additional references. Specifically, inclusion criteria were: (i) studies enrolling subjects with previous confirmed COVID-19 infection (ii) providing the hazard ratio (HR) and relative 95% confidence interval (CI) for the risk of new-onset HT after the infection compared to contemporary control cohorts. Conversely, case reports, review articles, abstracts, editorials/letters, and case series with less than 10 participants were excluded. Data extraction was independently conducted by two authors (M.Z., G.R). For all the reviewed investigations we extracted, when provided, the number of enrolled patients, the mean age, the gender, the prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities such as arterial hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), obesity, pre-existing heart failure (HF), cerebrovascular disease and the length of follow-up. The quality of included studies was graded using the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale (NOS) [11].

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean while categorical variables were presented as numbers and relative percentages. New-onset HT risk data were pooled using the Mantel–Haenszel random effects models with Hazard ratio (HR) as the effect measure with 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Higgins and Thomson I2 statistic. Specifically, the I2 values correspond to the following levels of heterogeneity: low (< 25%), moderate (25–75%) and high (> 75%). The presence of potential publication bias was verified by visual inspection of the funnel plot. Due to the low number of the included studies (< 10), small-study bias was not examined as our analysis was underpowered to detect such bias. However, a predefined sensitivity analysis (leave-one-out analysis) was performed removing 1 study at the time, to evaluate the stability of our results regarding the risk of new-onset HT. To further appraise the impact of potential baseline confounders, a meta-regression analysis was also performed. All meta-analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, version 3 (Biostat, USA).

Results

Search Results and Included Studies

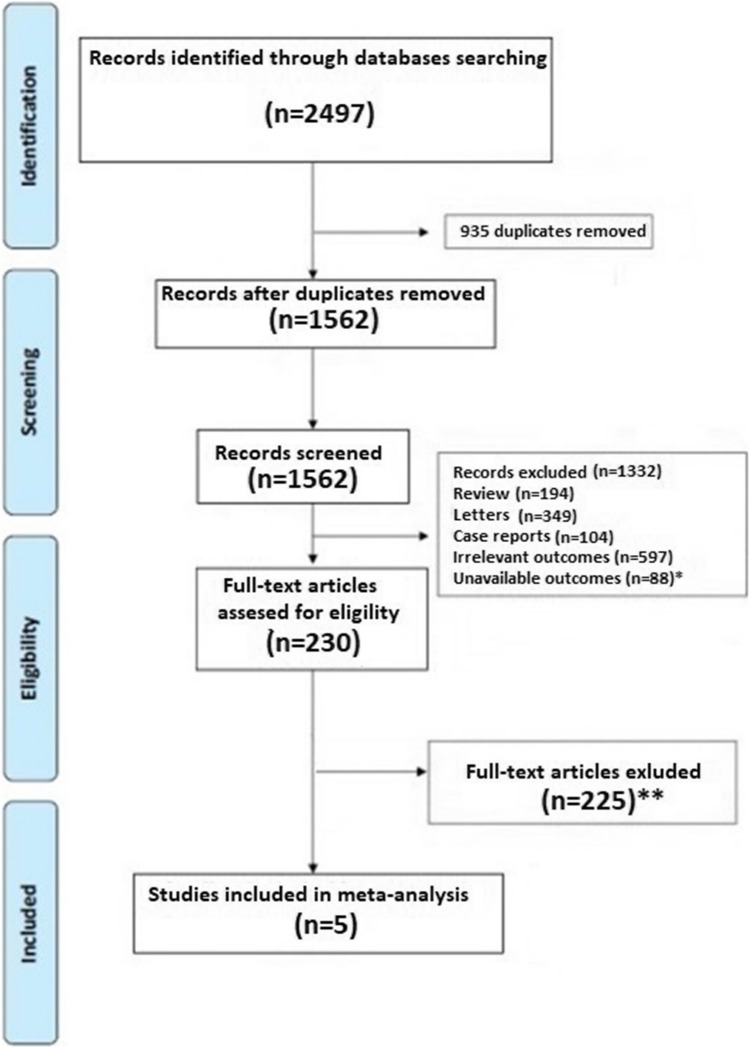

A total of 2497 articles were obtained using our search strategy. After excluding duplicates and preliminary screening, 230 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Among them, 225 studies were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, leaving 5 investigations fulfilling the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1) [12–16].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of selected studies for the meta-analysis according to the Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA). *Articles excluded because not provided data on new-onset arterial hypertension; **Articles excluded because not provided Hazard ratio for new-onset arterial hypertension

Characteristics of the Population and Quality Assessment

Overall, 19,293,346 patients (mean age 54.6 years, 54.6% males) were included in this analysis [12–16]. Among them 758,698 had confirmed COVID-19 infection. The general characteristics of the studies included are presented in Table 1. Although the demographic characteristics and concomitant comorbidities were not systematically recorded in all investigations, the cohorts mainly consisted of middle-aged patients. The mean length of follow-up was 6.8 months. Over the follow-up period, incident pericarditis occurred to 12.7 [95% CI 11.4–13.5] out of 1000 patients and to 8.17 [95% CI 7.34–8.53] out of 1000 patients in survived to COVID-19 infection and in control subjects, respectively. Quality assessment showed that all studies were of moderate-high quality according to the NOS scale (Table 1) [11].

Table 1.

General characteristics of the population reviewed

| Authors | Study Design | Sample size n |

Cases n |

Controls n |

Age (years) |

Males n (%) |

HT n (%) |

DM n (%) |

COPD n (%) |

CKD n (%) |

Obesity n (%) |

HF n (%) |

Cancer n (%) |

Cerebrovascular disease n (%) |

FW-length (months) | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen et al. [12] | R | 2.895.943 | 133,366 | 2,762,577 | 75.7 | 1.227.545 (42.0) |

2.081.772 (72.0) |

938.043 (32.7) | 578.650 (20)a | 528.314 (14.0) |

478.902 (17.0) |

334,654 (12) |

418.700 (14.4) |

364.782 (13.0) |

4 | 8 |

| Daugherty et al. [13] | R | 9.247.505 | 266,586 | 8,980,919 | 42.4 | 4.640.393 (50.2) | NR |

521.699 (5.6) |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6 | 6 |

| Al-Aly et al. [14] | R | 5.017.431 | 33,940 | 4,983,491 | 64.9 |

4.512.549 (89.9) |

NR | 1.275.370 | NR |

423.329 (8.4) |

NR | NR |

371.526 (7.4) |

288.266 (5.7) |

6 | 7 |

| Mizrahi et al. [15] | R | 1,913,324 | 320,857 | 1,792,150 | 25.0c |

148.095 (49.4)c |

22,490 (7.5)c |

11,412 (3.8)c |

1519 (0.5)c |

4756 (1.6)c |

63,418 (21.1)c |

NR |

6953 (2.3)c |

NR | 6 | 8 |

| Tisler et al. [16] | R | 19,460 | 3949 | 15,511 | 65.1 |

8900 (45.7) |

10,601 (54.4) |

3341 (17.1) |

2205 (13.9)a |

870 (4.4) |

1496 (7.6) |

NR |

3998 (20.5) |

578 (2.9) |

12 | 8 |

HT Arterial Hypertension, DM Diabetes Mellitus, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CKD Chronic Kidney disease, HF Heart failure, FW Follow-up, NR Not reported, R Retrospective

aDefined as Chronic Pulmonary disease

bOnly DM type 2. R: Retrospective

cReferred to propensity matched cohort

Risk of New-Onset Arterial Hypertension After COVID-19 Recovery

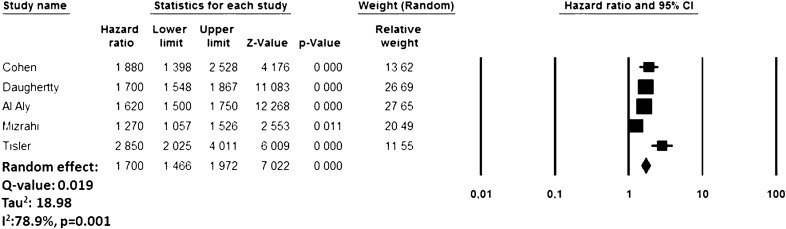

During the follow-up period, recovered COVID-19 patients presented an increased risk of new-onset HT (HR: 1.70, 95% CI 1.46–1.97, p < 0.0001, I2 = 78.9%) compared to subjects who did not experience COVID-19 infection but developed a pericarditis over the same period (Fig. 2). The funnel plot is presented in Supplemental File 2. The sensitivity analysis confirmed yielded results reporting an HR ranging between 1.62 (95% CI 1.53–1.71, p < 0.0001, I2:65.6%) and 1.80 (95% CI 1.56–2.07, p < 0.0001, I2: 71.8%), indicating that the obtained results were not driven by any single study.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot investigating the risk of new-onset arterial hypertension after COVID-19 Infection

Meta-regression for the Risk of New-Onset Arterial Hypertension

A meta-regression analysis showed a significant direct relationship for the risk of new-onset HT using age (p = 0.001), female sex (p = 0.03) and cancer (p < 0.0001) as moderators, while an indirect association was observed when the follow-up length (p < 0.0001) was adopted as moderating variables (Table 2).

Table 2.

Meta-regression analysis for the risk of new-onset arterial hypertension after COVID-19 infection

| Items | Coeff. | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.008 | 0.001 to 0.018 | 0.001 |

| Females (%) | 0.003 | 0.008 to 0.014 | 0.03 |

| DM (%) | 0.011 | − 0.033 to 0.054 | 0.62 |

| CKD (%) | 0.013 | − 0.047 to 0.074 | 0.66 |

| Cancer (%) | 0.040 | 0.021 to 0.059 | < 0.0001 |

| Follow-up length (months) | 0.073 | − 0.153 to − 0.005 | < 0.0001 |

CI Confidence interval, DM diabetes mellitus, Chronic kidney disease

Discussion

Our meta-analysis, based on a large population of more than 19 million people, showed that COVID-19 recovery subjects had an additional 70% risk of developing new-onset HF within 7 months from the acute infection. As demonstrated by the meta-regression, this risk was directly influenced by age, female sex and cancer and resulted higher in the early post-acute phase of the infection. The moderate heterogeneity observed may be also partly explained by the differences in baseline characteristics of the population enrolled, pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors and/or chronic conditions and immunization against COVID-19 infection. However, sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of our results.

The revised population had a lowest incidence rate of new-onset HT compared to the previous analyses based on the general population which vary between 15.3 and 47.3 per 1000 people [17–19]. This difference could be partially explained by the fact that the population revised was relatively young, having a median age of 54 years. Furthermore, potential sex and racial differences [20, 21] as well as the absence of a systematic blood pressure screening may have significantly contributed to the lower incidence race observed. Indeed, in the article reviewed, the new-onset HT was identified using the relative ICD-10 codes. However, our findings are in accordance with those presented by Zhang et al. [9] and Ogungbe et al. [22], which demonstrated am increased risk for essential HT after COVID-19 infection.

Unfortunately, the revised studies did not systematically report data regarding the left ventricular ejection fraction or the presence of target organ damage (TOD), limiting the possibility to further characterize the reported risk. However, to the best of our knowledge, our analysis represents the first attempt to comprehensively assess the risk of new-onset HT in the post-acute phase of COVID-19 subjects. Moreover, it is also true that when the death rate is high from causes other than the disease of interest, the incidence rates of the illness may be overestimated in traditional Kaplan–Meier survival analysis due to existence of competing risks [23].

Currently, pathophysiological mechanisms potentially involved in the onset of new HT remains poorly understood. However, it seems that viral persistence, delayed resolution of inflammation or residual organ damage after the acute phase of infection as well as renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) dysregulation and previous autoimmune conditions, may represent potential contributors, alone or together [24–26]. From our data it seems that females sex influences the risk of new-onset HT sequalae after COVID-19 infection. This difference may be partially explained by the known differences in immune system function between females and males [27]. Indeed, females generally mount more rapid and robust innate and adaptive immune responses, which can protect them from initial infection and severity. Wang et al. [28], analyzing the long-term cardiovascular squeal in COVID-19 survivors evidenced that women had a higher risk of cardiovascular events, including myocarditis, ischemic cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation compared to the sex-matched control subjects.

Unfortunately, most of the studies reviewed did not evaluate or report granular data by sex, which limited sex-specific sub-analysis in our analysis. Similarly, few data were provided regarding the potential association between the severity of the index COVID-19 infection and the subsequent risk of new-onset HT. However, data from Al-Aly et al. [14] and Tisler et al. [16] suggested that this risk significantly increase in patients hospitalized and in those requiring intensive care treatments compared to those not hospitalized. Indeed, the hospitalization setting may indirectly reflect the severity of COVID-19 infection. Moreover, Mizrahi et al. [15] observed an increased risk of new-onset HT during the recovery period in unvaccinated subjects compared to those immunized.

Our data, based on a large cohort, may be useful for designing strategies to minimize the risk of new HT onset during the post-acute phase after COVID-19 infection, although our results must be considered preliminary and cannot be directly translated into clinical practice regarding the use of antihypertensive drugs. However, our findings may have several implications for daily clinical practice and future research. Indeed, being the risk of new HT onset not limited just to the acute phase of the infection but extends in the medium/long-term period [29], indicating the need to prevent the infection and to consider post COVID-19 patients at future of HT and related cardiovascular consequences.

Changes in HT incidence over time represents an important issue which require urgent actions as increased awareness, adequate screening, and preventive measure to minimize the risk of future cardiovascular disease.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations related to the observational nature of the studies reviewed and their own limitations with all inherited bias. Potential underestimation could derive from detection bias considering that patients were not systematically screened HT and per se, these conditions is clinically silent. Moreover, sampling bias by the competing risk of death may also have led to underestimation of the real cumulative incidence of new HT cases. Our data must be carefully interpreted considering that the reviewed studies mainly based their search strategy on the revision of hospital admission and screening of ICD-10 codes during the follow-up period; indeed, the utility of such data largely depends on their accuracy and reliability. In fact, the absence of a dedicated screening for HT may have determined some bias in our analysis, evidencing the lower limit of such phenomenon. Furthermore, no data regarding the type of HT, the dipping status and the chronic use of anti-hypertensive drugs limited our ability to perform further sub analyses.

We can neither exclude those geographical differences, also related to the quality of care, may have influenced our findings. Finally, no data regarding the vaccination status of patients enrolled as well as information on variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus were systematically provided in the investigators reviewed, limiting the possibility to conduct further sub-analyses.

Conclusions

During the first months after COVID-19 infection, recovered patients have a higher risk to develop HT compared to subjects from the general population, which increase with aging, male sex and cancer. These findings suggest that HT represents an important post-acute COVID-19 sequelae that might benefit from an adequate primary prevention against SARS-CoV-2 infection and an appropriate follow-up in COVID-19 patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file 1: PRISMA Checklist. Supplementary material 1 (DOCX 28.5 kb)

Supplementary file 2: Full, search strategy. Supplementary material 2 (DOCX 13.9 kb)

Supplementary file 3: Funnel plot for the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation after COVID-19 infection. Supplementary material 3 (JPG 42.5 kb)

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

None of the Authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study did not require Ethical approval due to the study design.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Tadic M, Cuspidi C, Grassi G, Mancia G. COVID-19 and arterial hypertension: hypothesis or evidence? J Clin Hypertens. 2020;22:1120–6. doi: 10.1111/jch.13925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lippi G, Wong J, Henry BM. Hypertension in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pooled analysis. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2020;130:304–9. doi: 10.20452/pamw.15272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Zuliani G, Rigatelli A, Mazza A, Roncon L. Arterial hypertension and risk of death in patients with COVID-19 infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e84–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roncon L, Zuin M, Zuliani G, Rigatelli G. Patients with arterial hypertension and COVID-19 are at higher risk of ICU admission. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:e254–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayoubkhani D, Khunti K, Nafilyan V, Maddox T, Humberstone B, Diamond I, Banerjee A. Post-covid syndrome in individuals admitted to hospital with covid-19: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuin M, Barco S, Giannakoulas G, Engelen MM, Hobohm L, Valerio L, Vandenbriele C, Verhamme P, Vanassche T, Konstantinides SV. Risk of venous thromboembolic events after COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s11239-022-02766-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Roncon L, Pasquetto G, Bilato C. Risk of incident heart failure after COVID-19 recovery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10741-022-10292-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Battisti V, Costola G, Roncon L, Bilato C. Increased risk of acute myocardial infarction after COVID-19 recovery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2023;372:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2022.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang HG, Dagliati A, Shakeri Hossein Abad Z, Xiong X, Bonzel CL, Xia Z, Tan BWQ, Avillach P, Brat GA, Hong C, Morris M, Visweswaran S, Patel LP, Gutiérrez-Sacristán A, Hanauer DA, Holmes JH, Samayamuthu MJ, Bourgeois FT, L’Yi S, Maidlow SE, Moal B, Murphy SN, Strasser ZH, Neuraz A, Ngiam KY, Loh NHW, Omenn GS, Prunotto A, Dalvin LA, Klann JG, Schubert P, Vidorreta FJS, Benoit V, Verdy G, Kavuluru R, Estiri H, Luo Y, Malovini A, Tibollo V, Bellazzi R, Cho K, Ho YL, Tan ALM, Tan BWL, Gehlenborg N, Lozano-Zahonero S, Jouhet V, Chiovato L, Aronow BJ, Toh EMS, Wong WGS, Pizzimenti S, Wagholikar KB, Bucalo M, Consortium for Clinical Characterization of COVID-19 by EHR (4CE) Cai T, South AM, Kohane IS, Weber GM. International electronic health record-derived post-acute sequelae profiles of COVID-19 patients. NPJ Digit Med. 2022;5:81. doi: 10.1038/s41746-022-00623-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses (2012). http://www.ohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp, Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

- 12.Cohen K, Ren S, Heath K, Dasmariñas MC, Jubilo KG, Guo Y, Lipsitch M, Daugherty SE. Risk of persistent and new clinical sequelae among adults aged 65 years and older during the post-acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068414. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daugherty SE, Guo Y, Heath K, Dasmariñas MC, Jubilo KG, Samranvedhya J, Lipsitch M, Cohen K. Risk of clinical sequelae after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021;373:n1098. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Aly Z, Bowe B, Xie Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2022;28:1461–7. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01840-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizrahi B, Sudry T, Flaks-Manov N, Yehezkelli Y, Kalkstein N, Akiva P, Ekka-Zohar A, Ben David SS, Lerner U, Bivas-Benita M, Greenfeld S. Long covid outcomes at one year after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2023;380:e072529. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tisler A, Stirrup O, Pisarev H, Kalda R, Meister T, Suija K, Kolde R, Piirsoo M, Uusküla A. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 among hospitalized patients in Estonia: Nationwide matched cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0278057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colangelo LA, Yano Y, Jacobs DR, Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM. Association of resting heart rate with blood pressure and Incident Hypertension over 30 years in black and white adults: the CARDIA Study. Hypertension. 2020;76:692–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ladin A, Al Rifai M, Rasool S, et al. The association of resting heart rate and Incident Hypertension: the Henry Ford Hospital Exercise Testing (FIT) project. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29:251–7. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpv095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tu K, Chen Z, Lipscombe LL, Canadian Hypertension Education Program Outcomes Research Taskforce Prevalence and incidence of hypertension from 1995 to 2005: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2008;178:1429–35. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kent ST, Schwartz JE, Shimbo D, Overton ET, Burkholder GA, Oparil S, Mugavero MJ, Muntner P. Race and sex differences in ambulatory blood pressure measures among HIV + adults. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2017;11:420–427e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asgari S, Moazzeni SS, Azizi F, Abdi H, Khalili D, Hakemi MS, Hadaegh F. Sex-specific incidence rates and risk factors for hypertension during 13 years of follow-up: the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Glob Heart. 2020;15:29. doi: 10.5334/gh.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogungbe O, Gilotra NA, Davidson PM. Et alCardiac postacute sequelae symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 in community-dwelling adults: cross-sectional. studyOpen Heart. 2022;9:e002084. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133:601–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehandru S, Merad M. Pathological sequelae of long-haul COVID. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:194–202. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01104-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto C, Shibata S, Kishi T, Morimoto S, Mogi M, Yamamoto K, Kobayashi K, Tanaka M, Asayama K, Yamamoto E, Nakagami H, Hoshide S, Mukoyama M, Kario K, Node K, Rakugi H. Long COVID and hypertension-related disorders: a report from the Japanese society of Hypertension Project Team on COVID-19. Hypertens Res. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41440-022-01145-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Annweiler Z, Cao Y, Wu E, Faucon S, Mouhat H, Kovacic J, Sabatier M. Counter-regulatory ‘renin-Angiotensin’ systemBased candidate drugs to treat COVID-19 diseases in SARS-CoV-2-Infected patients. Infect Disord -Drug Targets. 2020;20:407–8. doi: 10.2174/1871526520666200518073329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:626–38. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Wang CY, Wang SI, Wei JC. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in COVID-19 survivors among non-vaccinated population: a retrospective cohort study from the TriNetX US collaborative networks. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;53:101619. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruzzenenti G, Maloberti A, Giani V, Biolcati M, Leidi F, Monticelli M, Grasso E, Cartella I, Palazzini M, Garatti L, Ughi N, Rossetti C, Epis OM, Giannattasio C, Covid-19 Niguarda Working Group Covid and cardiovascular diseases: direct and indirect damages and future perspective. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2021;28:439–45. doi: 10.1007/s40292-021-00464-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file 1: PRISMA Checklist. Supplementary material 1 (DOCX 28.5 kb)

Supplementary file 2: Full, search strategy. Supplementary material 2 (DOCX 13.9 kb)

Supplementary file 3: Funnel plot for the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation after COVID-19 infection. Supplementary material 3 (JPG 42.5 kb)