Abstract

Objectives

To examine the disparities between COVID-19 studies conducted in high-income countries (HICs) and low-and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods

We used the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform to identify COVID-19-related studies registered from December 31, 2019 to December 31, 2021. The World Bank definition was used to classify countries as high-, upper-middle-, lower-middle-, and low-income. The last three were considered to be LMICs. We examined the disparities in response speed, classification of medicines and vaccines, and registration and results reporting compliance between COVID-19 studies conducted in HICs and LMICs.

Results

We included 12,396 COVID-19 studies, with 6631 (53.5%) from HICs. HIC-registered studies reached a peak of 1039 in April 2020, whereas LMICs had only 440 studies. Of the 6969 interventional trials, those from HICs showed higher registration compliance (2199, 62.3% vs 1979, 57.6%, P <0.001) and results reporting compliance (hazard ratio 0.39, 95% confidence interval 0.28-0.55, P < 0.001) than LMICs. HICs also conducted significantly more small-molecule drug (956, 57.5% vs 868, 41.2%, P <0.001) and messenger RNA vaccine trials (135, 32.9% vs 19, 4.8%, P <0.001) than LMICs.

Conclusion

HICs conducted COVID-19 trials with faster response speed and higher registration and publication compliance and produced more innovative pharmaceutical and vaccine products to combat COVID-19 than LMICs.

Keywords: COVID-19, Clinical trials, Income economies, Registry platform

Introduction

COVID-19 is caused by SARS-CoV-2. From the end of 2019, the outbreak spread rapidly worldwide and critically affected global public health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers worldwide conducted numerous studies and made active efforts to explore the effective therapeutic approaches and prevention strategies for COVID-19. The range of COVID-19 studies that have been conducted worldwide should be understood. Since Zhang et al. published the first article on the analysis of clinical trials of COVID-19 therapies registered in China [1], subsequent articles have focused on the baseline characteristics, study design [2], [3], [4], [5], drug or vaccine effectiveness [6], [7] and strength of evidence of the COVID-19 registry studies [8].

High-income countries (HICs) and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have disparities in both their research infrastructures (researchers, the pharmaceutical sector, ethical and regulatory regimes, and data analysis) and their health facility infrastructure (medical devices, drugs, testing capacity, and standard registration systems) [9], [10], [11]. These disparities have encouraged researchers to explore whether disparities existed in COVID-19 studies conducted in HICs and LMICs. Ramanan and et al. discovered disparities between HICs and LMICs in the participation and leadership of COVID-19 trials published in leading medical journals [12]. Ramachandran et al. investigated the access to COVID-19 vaccines and found that HICs received proportionately more doses, allowing them to vaccinate their populations fully [13]. These articles have exposed the dominance of HICs in COVID-19 clinical trials; however, to the best of our knowledge, data are very limited on the disparities in response speed between HICs and LMICs in conducting COVID-19 studies. Whether there are disparities between HICs and LMICs in the registration and results reporting compliance for COVID-19 studies or in innovative drug and vaccine trials remains unknown.

This review included COVID-19 studies registered on the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) from December 31, 2019 to December 31, 2021. The objectives were to understand the disparities in the response speed, medication and vaccine innovation, and registration and publication compliance for COVID-19 studies conducted in HICs and LMICs.

Methods

Data source and search strategy

The World Health Organization (WHO) ICTRP is a voluntary platform used to link clinical trials registers and ensure a single point of access and the unambiguous identification of trials, and 18 original national and regional clinical trial registry platforms were used as the data source. These platforms were as follows: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry, Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, Clinical Research Information Service, Republic of Korea, Clinical Trials Registry - India, Clinical Trials.gov database, Cuban Public Registry of Clinical Trials, European Union Clinical Trials Register, German Clinical Trials Register, Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials, International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Registry, Japan Primary Registries Network, Lebanese Clinical Trials Registry, Thai Clinical Trials Registry, The Netherlands Trial Register, Pan African Clinical Trial Registry, Peruvian Clinical Trial Registry, and Sri Lanka Clinical Trials Registry.

We obtained raw data from COVID-19-related studies registered from December 31, 2019 to December 31, 2021 through the ICTRP platform. Two investigators (L.Z.Y. and Y.S.) independently performed a supplemental search of the 18 data sources included in the ICTRP. Searches were performed using the terms “Novel coronavirus”, “coronavirus disease 2019”, “2019 novel coronavirus”, “COVID-19”, “2019-nCov”, “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus2”, “SARS coronavirus 2”, and “SARS-CoV-2” as keywords.

Study selection

We included COVID-19-related studies if they were reports in the English language. If a study was registered on multiple platforms, the registration time was taken from the first registered platform and the data from the platform with the most complete information. There were no constraints on sample size, study design, patient age, or intervention types. Studies with withdrawn, suspended, terminated, or uncertain status were excluded, as well as nonpopulation-based studies.

All eligible studies were reviewed using a data abstraction form to capture information on registration time, recruitment time of the first participant, sample size, age, study type, gender, primary sponsor, centers of research, funding support, study design, and results reporting. Data abstraction was performed independently by two of the authors (L.Z.Y. and Y.S.). The senior author (L.L.) performed random duplicate abstraction to ensure that the data abstraction was of high quality.

The supplementary files include a flow diagram of the screening procedure for COVID-19 studies. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses reporting guideline.

Data definition

We used the World Bank definition to categorize economies as HICs, upper-middle-income, lower-middle-income, or low-income countries. Upper-middle-income, lower-middle-income, and low-income countries were combined as LMICs [14]. We classified studies into countries by the affiliation of the primary sponsors. Funding and material support sources for studies were categorized as industry and nonindustry, with nonindustry including government, hospital, university, foundation, individual, or academic institution. The term nation, synonymous with the economy, did not imply political independence but refers to any region where authorities collect and report distinct social and economic information.

In line with the policy of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), a study was considered to be compliant with registration if it was registered before enrolling the first participant [15]. In line with the final regulation of the Food and Drug Administration amendments act (FDAAA) of 2007, a study was regarded as compliant with reporting requirements if the results were published within 1 year of the primary completion date [16], [17], [18].

Statistical analysis

The median (25th and 75th percentile) showed skewed distributions of continuous variables. Categorical data were described using percentages and compared using the chi-square or Fisher's exact tests. We used the Kaplan-Meier method to model time from the primary completion date to results submission for randomized controlled trials and separately for industry-funded interventional trials. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS software version 25. P-values were deemed statistically significant at less than 0.05.

Results

Search results and distribution of studies

Overall, 16,828 studies were registered from December 31, 2019 to December 31, 2021. After the removal of studies that met the exclusion criteria, we included 12,396 studies that planned to enroll 337,813,461 participants. The World Bank classifies 81 countries as HICs and 136 as LMICs. HICs had a higher percentage of country participation than LMICs in COVID-19 studies (50/81, 61.7% vs 67/136, 49.3%). HICs also hosted more COVID-19 studies than LMICs (6631, 53.5% vs 5765, 46.5%).

To explore whether there are disparities between HICs and LMICs in the relationship between the number of COVID-19 cases and studies, we used bubble plots to show the relationship between the number of COVID-19 cases and studies in HICs and LMICs. Figure 1 shows the trend in HICs, where more COVID-19 cases were associated with more studies, especially in countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and France.

Figure 1.

Relationship of COVID-19 studies with total COVID-19 cases in HICs and LMICs. Each bubble represents a country, and the size of the bubble is proportional to the number of studies conducted. In HICs, there was a trend toward more COVID-19 cases being associated with more studies. HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low-middle-income country.

General characteristics of the COVID-19 research

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 12,396 COVID-19 studies. The proportion of interventional trials was higher in LMICs than in HICs (3437, 59.6% vs 3532, 53.3%, P <0.001). HICs had a higher proportion of studies in the recruitment (3853, 58.1% vs 2496, 43.3%, P <0.001) and completion phases (1824, 27.5% vs 1110, 19.3%, P <0.001) than LMICs. Furthermore, more studies were funded by industry (1463, 22.1% vs 795, 13.8%, P <0.001) and multinationals (495, 7.5% vs 71, 1.2%, P <0.001) in HICs than in LMICs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the COVID-19 studies.

| Characteristic | Studies, no (%)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| HICs | LMICs | |

| Study type | ||

| Interventional | 3532(53.3) | 3437(59.6)* |

| Observational | 3065(46.2) | 2275(39.5)* |

| Status | ||

| Not yet recruiting | 920(13.9) | 2158(37.4)* |

| Recruiting | 3853(58.1) | 2496(43.3)* |

| Completed | 1824(27.5) | 1110(19.3)* |

| Funding source type | ||

| Industryb | 1463(22.1) | 795(13.8)* |

| Number of research nations | ||

| Single national | 5888(88.8) | 5533(96.0)* |

| Multinationals | 495(7.5) | 71(1.2)* |

| Allocationc | ||

| RCTs | 2474(70.0) | 2687(78.2)* |

| Non-RCTs | 1058(30.0) | 750(21.8)* |

| Number of research centersd | ||

| Single center | 1228(49.6) | 1931(71.9)* |

| Blindingd | ||

| Blinded | 1506(60.9) | 1389(51.7)* |

| Length of study timed | ||

| Median (IQR) | 258(132,417) | 120(62,230) |

| Length ≤6 months | 758(30.6) | 1517(56.5)* |

| Length >6 months | 1328(53.7) | 678(25.2)* |

| Sample sized | ||

| Median (IQR) | 168(63,500) | 100(60,233) |

| Sample ≤100 | 947(38.3) | 1444(53.7)* |

| Sample >500 | 612(24.7) | 329(12.2)* |

| Number of primary outcomesd | ||

| Only one | 1532(61.9) | 1437(53.5)* |

| Subjectd | ||

| Asymptomatic to moderate patient | 238(9.6) | 467(17.4)* |

HIC, high-income country; IQR, interquartile range; RCT, randomized control trial.

Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100. The complete form is detailed in the supplementary materials.

“industry” included industry or industry combination with government, hospitals, universities, foundations, individuals, and academic institutions.

Interventional trials.

Randomized controlled trials.

P <0.001 for LMICs compared to HICs.

Of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs), HICs had a higher proportion that had used blinding than LMICs (1506, 60.9 % vs 1389, 51.7%, P <0.001). They also had more COVID-19 trials with sample sizes over 500 than LMICs (612, 24.7 % vs 329, 12.2%, P <0.001). The median study duration was 6 months longer in HICs than in LMICs (258 days, interquartile range [IQR] 132-417 vs 120, IQR 62-230), and the proportion of asymptomatic to moderate participants was lower in HICs than in LMICs (238, 9.6% vs 467, 17.4%, P <0.001).

Registration and results reporting compliance

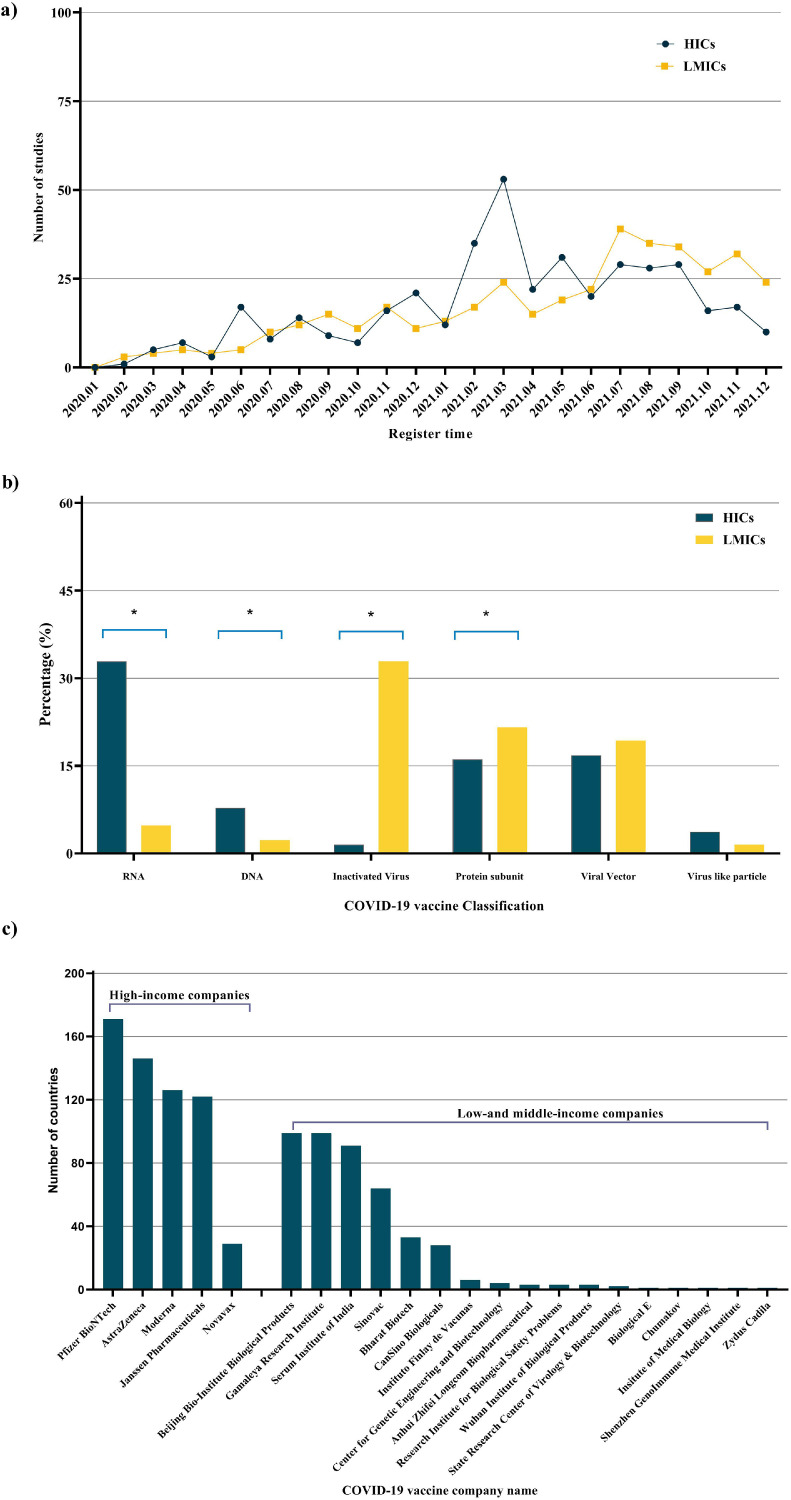

After the outbreak of the pandemic in HICs in February 2020, the number of registered research skyrocketed, with over 1,500 COVID-19 studies being registered in less than 2 months. The number of studies registered in HICs reached a peak of 1,039 within 2 months of the COVID-19 outbreak. At this stage, only 440 studies had been registered in LMICs (Figure 2 a). HICs had a higher registration compliance for interventional trials (2199, 62.3% vs 1979, 57.6%, P <0.001) and RCTs (1642, 66.4% vs 1587, 59.1%, P <0.001) than LMICs (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Compliance with registration and results reporting requirements for HICs and LMICs in COVID-19 interventional trials and RCTs. (a) The number of COVID-19 studies registered in HICs and LMICs per month. (b) Registration compliance for interventional trials, RCTs, and those funded by industry in HICs and LMICs. Kaplan-Meier curves showing time to reporting from the primary completion date for (c) interventional trials and RCTs; and (d) classified by industry and nonindustry. The dotted line in Figures c and d shows the 1-year deadline by which trials should have reported their results to comply with the Food and Drug Administration amendments act of 2007. *P <0.001 for LMICs compared to HICs. HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low-middle-income country; RCT, randomized control trial.

Figure 1(c,d) shows the Kaplan-Meier curves of time to report from the primary completion date for the included trials. Of the 1,558 interventional studies and 1,151 RCTs completed, we had information on the results’ first posted date for 1,456 and 1075. Only 117 (7.5%) interventional trials and 93 (8.1%) RCTs published their results within the 1-year reporting deadline, of which 86 (73.5%) interventional trials and 68 (73.1%) RCTs were conducted in HICs. Interventional trials (hazard ratio [HR] 0.39, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.28-0.55, P <0.001) and RCTs (HR = 0.35, 95% CI 0.24-0.51, P <0.001) were significantly more likely to be compliant with registration and results reporting requirements in HICs than LMICs. After the required period publication deadline, the discrepancy in COVID-19 trial results reporting compliance between HICs and LMICs became even more apparent.

Trials focused on medicines, vaccines, and in vitro diagnostic tests

Medicine trials

The clinical trials of drugs for COVID-19 registered in HICs peaked less than 2 months after February 2020, the date considered to mark the outbreak of COVID-19. Drug clinical trial registrations reached a peak in HICs faster than in LMICs (Figure 3 a). The number of monthly registered drug clinical trials for HICs and LMICs showed similar trends to trials using marketed drugs (Figure 3b). Most importantly, each point in Figure 3c show that HICs register more new drug clinical trials than LMICs.

Figure 3.

Relationship between the number and classification of drug clinical trials in HICs and LMICs. (a) The number of registered drug clinical trials; (b) marketed drug clinical trials; and (c) new drug clinical trials in HICs and LMICs. Figures 3a to 3c are all shown per month. (d) The proportion of each category of medicine in HICs and LMICs. *P <0.001 for LMICs compared to HICs. HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low-middle-income country.

We carried out further analyses of categories of medicines trialed in HICs and LMICs. HICs had more trials than LMICs of small-molecule drugs (956, 57.5% vs 868, 41.2%, P <0.001) and neutralizing antibodies (173, 10.4% vs 79,3.7%, P <0.001). Examples included the emergency approval of molnupiravir and casirivimab/imdesimab for the treatment of COVID-19. LMICs were more likely than HICs to trial traditional treatments, such as Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicines, which are widely used in many LMICs (46, 2.8% vs 534. 25.3%, P <0.001).

COVID-19 vaccine trials

Of the 808 COVID-19 vaccine trials, there was no significant difference between HICs and LMICs in the number of studies (410 vs 398) (Figure 4 a). Notably, HICs hosted more messenger RNA (mRNA) (135, 32.9% vs 19, 4.8%, P <0.001) and DNA vaccines (32, 7.8% vs 9, 2.3%, P <0.001) trials than LMICs. In contrast, LMICs hosted more inactivated vaccine trials than HICs (131, 31.9% vs 6, 1.5%, P <0.001) (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Relationship between the number and classification of vaccines developed in HICs and LMICs in the COVID-19 trials. (a) The number of registered COVID-19 vaccine trials in HICs and LMICs per month. (b) COVID-19 vaccine classification in HICs and LMICs. (c) The number of countries that have approved vaccines developed in HICs and LMICs. *P <0.001 for LMICs compared to HICs. HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low-middle-income country.

According to the WHO COVID-19 vaccine database, as of August 29, 2022 [19], 22 pharmaceutical companies offer 31 vaccine products. Surprisingly, only five of these 22 pharmaceutical companies are based in HICs. Far more are based in LMICs. More countries overall have approved for emergency use COVID-19 vaccines developed in HICs than in LMICs (582 vs 460). The median was also much higher for HIC-developed vaccines than LMICs (122, IQR 51-182 vs 3, IQR 6-30).

In vitro diagnostic test trials

The world's first in vitro diagnostic test clinical trial was registered in an HIC less than 1 month after February 2020. We included 155 in vitro diagnostics trials in this study, of which 80% were conducted in HICs.

The WHO emergency use listing for in vitro diagnostics detecting SARS-CoV-2 includes 33 products as of October 06, 2022 [20], of which 17 were produced in HICs. The first in vitro diagnostic test to detect SARS-CoV-2 was also developed in an HIC and received WHO emergency use approval in April 2020. Overall, 16 in vitro diagnostics tests were from LMICs, of which 14 were developed in China.

Discussion

We examined the COVID-19 studies conducted in HICs and LMICs and found a sizable disparity between them. There were several noteworthy points. First, HICs played a leading role in research and quickly conducted diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive studies to combat COVID-19. Second, HICs had higher compliance with study registration and results reporting requirements. Third, HICs seemed more intent on finding novel medications and vaccines that can rapidly be transformed into efficient treatments and preventive measures for defeating COVID-19.

Numerous studies have explored the differences between HICs and LMICs in preventing and treating COVID-19 during the pandemic. Park et al. reported that more COVID-19 studies were conducted in HICs than LMICs, which has led to inadequate geographical representation of LMICs in the COVID-19 studies landscape [21]. Usuzaki et al. confirmed that HICs published more COVID-19-related articles than LMICs [22]. Ramanan et al. found that HICs have more COVID-19 studies published in leading medical journals than LMICs [12]. This was consistent with our findings that HICs were conducting more COVID-19 studies and were able to jump in quickly during the early pandemic phase. These results suggested that HICs were leading the global fight against COVID-19. Based on these results, we further analyzed the medication and vaccine innovation. We found that studies in HICs focused significantly more than LMIC studies on small-molecule drugs. To date, the main treatment option for COVID-19 is oral small-molecule antiviral drugs, especially for severe cases [23], [24]. For vaccine development, mRNA-based technology has outperformed more cumbersome traditional vaccine development methods and is the most successful means for rapidly developing vaccines against COVID-19 [24], [25], [26]. Our study showed that HICs hosted nearly 87.7% of mRNA vaccine trials. These findings suggested that HICs were more likely than LMICs to produce innovative and effective products to combat COVID-19.

Researchers are concerned about the disparities in research conducted in HICs and LMICs for many different diseases, conditions, and specialties, including cancer [27], [28], gynecology [10], [29], kidney disease [30], and sickle cell disease [31], etc. Oncology RCTs in LMICs were more likely to have palliative intent than in HICs [28]. A nephrology study found that the availability of infrastructure for HICs far exceeded that of LMICs [30]. For a disease like COVID-19, which was previously unknown in humans and spread rapidly, researchers were also interested in exploring whether there were differences in the COVID-19 studies conducted by HICs and LMICs. Ramanan et al. observed disparities between HICs and LMICs in the participation and leadership of COVID-19 studies published in leading medical publications [12]. Ramachandran et al. discovered that HICs received proportionately more doses of COVID-19 vaccines, allowing them to vaccinate their populations fully [13]. We found that COVID-19 studies conducted in HICs and LMICs exhibited disparities in response speed, medication and vaccine innovation, and compliance with trial registration and publication requirements. The reasons for the disparities include research and health facility infrastructure limitations, capacity for designing and regulating studies, and the clinical workload of health care workers [10], [32], [33]. In the future, LMICs need to narrow the disparities with HICs and protect the rights of their populations by improving research infrastructure, mobilizing funding from diverse sources, strengthening research capacity, and identifying relevant translatable research priorities.

Another issue of concern is access to COVID-19 diagnosis, therapeutics, and vaccines. Olalekan et al. reported that testing per population is high in developed countries but was deficient in developing countries during the early stages of COVID-19. The low testing rate severely underestimated COVID-19 cases [34], [35], [36]. The COVID-19 oral antiviral agents—nirmatrelvir/ritonavir and molnupiravir—have been approved in multiple countries. However, purchases were dominated by HICs, and LMICs had limited access to these drugs because of supply, funding, and distribution [23], [37], [38]. Similarly, the LMICs’ limited ability to purchase large quantities of vaccines, their vaccination policies, and vaccine hesitancy limited vaccination in LMICs. This difference in accessibility between HICs and LMICs increases the gap between different income economies on effective outbreak response and population protection.

Clinical trial transparency can provide accessibility to the public, advance medical science, and inform medical decision making [39]. To increase trial transparency, the United States has passed legislation FDAAA 2007 Final Rule, which mandated the trial registration and publication of results. The ICMJE required public registration of clinical trials before publication would be considered. However, Dal-Ré et al. reported that 72% of trials published in high-impact journals were prospectively registered and that these trials were registered within 6 months of the effective date of the public registration required by the ICMJE [40]. DeVito et al. claimed that compliance with the registration and results reporting requirements in the FDAAA was poor and not improving [41]. We found that approximately 60% of interventional trials were prospectively registered, and only 117 (7.5%) trials published results within the 1-year reporting deadline. This level of compliance is therefore worse than previously found [41]. In the face of the rapid spread of COVID-19, study registration and reporting of results should be completed on time, even if it is difficult. This will avoid duplication of studies, and enable rapid development of effective therapies against COVID-19.

Conclusion

The WHO claimed that the global COVID-19 situation was better now than during the peak of Omicron transmission. Each country has made efforts to support the progress against the pandemic, and HICs and LMICs have played different roles in the pandemic. HICs conducted COVID-19 trials with faster response speed, with higher registration and publication compliance, and produced more innovative and effective medicine and vaccine products than LMICs. They, therefore, played an important role in leading the global fight against COVID-19. The long-term systemic sequelae of post–COVID-19 condition and the elevated risk of postinfection cardiovascular and metabolic disease will probably have a severe negative ongoing impact on the population. The disparities between HICs and LMICs are more likely to persist in the future as long COVID-19 affects more people worldwide. LMICs need to reduce the disparities with HICs and strengthen their readiness to respond to pandemic outbreaks, contributing significantly to managing diseases.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. It considered clinical trials registered on ICTRP and 18 national and regional clinical trial partner registers, which may not reflect all the COVID-19 studies worldwide. Similarly, the data on trial outcomes were obtained from registration platforms rather than from articles published in journals. The number of articles actually published on COVID-19 is undoubtedly higher than those listed in the registers because of untimely updating of the register data. This study did not examine the COVID-19 medications that are now on the market nor evaluate the clinical efficacy and real patient benefit of the various medicines and vaccinations. Finally, the FDAAA of 2007 was the proposed rule that most accurately applied to clinical trial registration and resulted in submission in the United States. Our study expanded the scope of applicable clinical trials, and not all databases must follow the FDAAA publication requirements.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The work was funded under a grant from Guizhou Province Science and Technology Project ([2020]4Y164), Guiyang Science and Technology Project ([2021]43-5), and Guizhou Provincial Health Commission Science and Technology Project (gzwkj2021-428). The funders of this study did not play any role in the study conception, designed, guided, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Ethical approval

All trials used publicly available data without protected health information. Therefore, ethical approval and patient written informed consent are not required.

Author contributions

Sha Yin had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Lei Luo, Guangheng Luo, Sha Yin. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Lei Luo, Zhenyu Li, Sha Yin, Guangheng Luo. Drafting of the manuscript: Sha Yin. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Sha Yin. Administrative, technical, or material support: Lei Luo. Supervision: Lei Luo, Guangheng Luo, Jingwen Ren.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in this study are publicly accessible from the ICTRP portal.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2023.04.393.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Zhang Q, Wang Y, Qi C, Shen L, Li J. Clinical trial analysis of 2019-nCoV therapy registered in China. J Med Virol. 2020;92:540–545. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kouzy R, Abi Jaoude J, Garcia Garcia CJ, El Alam MB, Taniguchi CM, Ludmir EB. Characteristics of the multiplicity of randomized clinical trials for coronavirus disease 2019 launched during the pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fidahic M, Nujic D, Runjic R, Civljak M, Markotic F, ZL Lovric Makaric, al et. Research methodology and characteristics of journal articles with original data, preprint articles and registered clinical trial protocols about COVID-19. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20:161. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-01047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu L, Li F, Wen H, Ge S, Zeng J, Luo W, et al. An evidence mapping and analysis of registered COVID-19 clinical trials in China. BMC Med. 2020;18:167. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01612-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang J, He Y, Su Q, Yang J. Characteristics of COVID-19 clinical trials in China based on the registration data on ChiCTR and ClinicalTrials.gov. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:2159–2164. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S254354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fragkou PC, Belhadi D, Peiffer-Smadja N, Moschopoulos CD, Lescure FX, Janocha H, et al. Review of trials currently testing treatment and prevention of COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:988–998. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen VT, Rivière P, Ripoll P, Barnier J, Vuillemot R, Ferrand G, et al. Research response to coronavirus disease 2019 needed better coordination and collaboration: a living mapping of registered trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;130:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pundi K, Perino AC, Harrington RA, Krumholz HM, Turakhia MP. Characteristics and strength of evidence of COVID-19 studies registered on ClinicalTrials.gov. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1398–1400. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seruga B, Sadikov A, Cazap EL, Delgado LB, Digumarti R, Leighl NB, et al. Barriers and challenges to global clinical cancer research. Oncologist. 2014;19:61–67. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grover S, Xu M, Jhingran A, Mahantshetty U, Chuang L, Small W. Clinical trials in low and middle-income countries - Successes and challenges. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;19:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dandekar M, Trivedi R, Irawati N, Prabhash K, Gupta S, Agarwal JP, D'Cruz AK. Barriers in conducting clinical trials in oncology in the developing world: A cross-sectional survey of oncologists. Indian J Cancer. 2016;53:174–177. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.180865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramanan M, Tong SYC, Kumar A, Venkatesh B. Geographical representation of low- and middle-income countries in randomized clinical trials for COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramachandran R, Ross JS, Miller JE. Access to COVID-19 vaccines in high-, middle-, and low-income countries hosting clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The World Bank. World Bank country and lending groups, https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups; 2022 [accessed 16 September 2022].

- 15.The ICMJE's clinical trial registration policy, https://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/publishing-and-editorial-issues/clinical-trial-registration.html; 2022 [accessed 16 September 2022].

- 16.US Food and Drug Administration . 2007. Food and Drug Administration amendments act of 2007,https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-110publ85/pdf/PLAW-110publ85.pdf [accessed 16 September 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarin DA, Tse T, Sheehan J. The proposed rule for U.S. clinical trial registration and results submission. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:174–180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1414226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, Car S. Trial reporting in ClinicalTrials.gov - the final rule. N Engl J Med. 2016;37:1998–2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1611785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Vaccination metadata, https://covid19.who.int/data; 2022 [accessed 29 August 2022].

- 20.World Health Organization. Emergency use list: IVDs for SARS-CoV-2, https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/vitro-diagnostics/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-pandemic-%E2%80%94-emergency-use-listing-procedure-eul-open; 2022 [accessed 06 October 2022].

- 21.Park JJH, Mogg R, Smith GE, Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Jehan F, Rayner CR, et al. How COVID-19 has fundamentally changed clinical research in global health. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e711–e720. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30542-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Usuzaki T, Chiba S, Shimoyama M, Ishikuro M, Obara T. A disparity in the number of studies related to COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 between low- and middle-income countries and high-income countries. Int Health. 2021;13:379–381. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihaa088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Launch & Scale Speedometer. COVID-19 therapeutics, https://launchandscalefaster.org/covid-19/therapeutics; 2022 [accessed 06 March 2023].

- 24.Kumari M, Lu RM, Li MC, Huang JL, Hsu FF, Ko SH, et al. A critical overview of current progress for COVID-19: development of vaccines, antiviral drugs, and therapeutic antibodies. J Biomed Sci. 2022;29:68. doi: 10.1186/s12929-022-00852-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang E, Liu XH, Li M, Zhang ZL, Song LF, Zhu BY, et al. Advances in COVID-19 mRNA vaccine development. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:94. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00950-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park JW, Lagniton PNP, Liu Y, Xu RH. mRNA vaccines for COVID-19: what, why and how. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17:1446–1460. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.59233. eCollection 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells JC, Sharma S, Del Paggio JCD, Hopman WM, Gyawali B, Mukherji D, et al. An analysis of contemporary oncology randomized clinical trials from low/middle-income vs high-income countries. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:379–385. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubagumya F, Hopman WM, Gyawali B, Mukherji D, Hammad N, Pramesh CS. Participation of lower and upper middle-income countries in clinical trials led by high-income countries. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.27252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen J, Sleaby R, Kumarakurusingham E, Mol BW. Randomised controlled trials in women's health in the last two decades: A meta-review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022;278:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.09.001. (Epub 2022 Sep 7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okpechi IG, Alrukhaimi M, Ashuntantang GE, Bellorin-Font E, Benghanem Gharbi MB, Braam B, et al. Global capacity for clinical research in nephrology: a survey by the International Society of Nephrology. Kidney Int Suppl. 2018;8:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.10.012. (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gyamfi J, Ojo T, Epou S, Diawara A, Dike L, Adenikinju D, et al. Evidence-based interventions implemented in low-and middle-income countries for sickle cell disease management: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okpechi IG, Swanepoel CR, Venter F. Access to medications and conducting clinical trials in LMICs. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:189–194. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.COVID-19 Clinical Research Coalition Electronic address: nick.white@covid19crc.org. Global coalition to accelerate COVID-19 clinical research in resource-limited settings. Lancet. 2020;395:1322–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30798-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olalekan A, Iwalokun B, Akinloye OM, Popoola O, Samuel TA, Akinloye O, et al. COVID-19 rapid diagnostic test could contain transmission in low- and middle-income countries. Afr J Lab Med. 2020;9:1255. doi: 10.4102/ajlm.v9i1.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pasquale S, Gregorio GL, Caterina A, Francesco C, Beatrice PM, Vincenzo P, et al. COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): a narrative review from prevention to vaccination strategy. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:1477. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9121477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han AX, Hannay E, Carmona S, Rodriguez B, Nichols BE, Russell CA. Estimating the potential need and impact of SARS-CoV-2 test-and-treat programs with oral antivirals in low-and-middle-income countries. medRxiv 05 October 2022. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.10.05.22280727v1 [accessed 28 February 2023].

- 37.So AD, Woo J. Reserving coronavirus disease 2019 vaccines for global access: cross sectional analysis. BMJ. 2020;371:m4750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith DJ, Hakim AJ, Taylor A, Bennett SD, Patel P, Greiner A, Marston BJ. Global challenges with oral antivirals for COVID-19. Popul Health Manag. 2022;25:822–827. doi: 10.1089/pop.2022.0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lassman SM, Shopshear OM, Jazic I, Ulrich J, Francer J. Clinical trial transparency: a reassessment of industry compliance with clinical trial registration and reporting requirements in the United States. BMJ Open. 2017;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dal-Ré R, Ross JS, Marušić A. Compliance with prospective trial registration guidance remained low in high-impact journals and has implications for primary end point reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeVito NJ, Bacon S, Goldacre B. Compliance with legal requirement to report clinical trial results on ClinicalTrials.gov: a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:361–369. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are publicly accessible from the ICTRP portal.