Background:

Lymphedema can significantly affect patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Various quality of life scales have been developed to assess the extent of the disease burden. The purpose of this study is to review various HRQoL instruments that have been used in lymphedema studies and compare their qualities against the COSMIN checklist.

Methods:

A systematic literature review search was conducted for clinical lymphedema studies published between January 1, 1984, and February 1, 2020, using Pubmed database. All clinical lymphedema studies which used HRQoL instruments as outcome measures were identified.

Results:

One thousand seventy-six studies were screened—of which, 288 studies were individually assessed. Thirty-nine HRQoL instruments were identified in these clinical lymphedema studies. Of these, there are eight lymphedema-specific questionnaires that cover all HRQoL domains, all of which have been validated for use in lymphedema. We contrasted the two most popular questionnaires [LYMQOL and Upper Limb Lymphedema (ULL)-27] and compared their features.

Conclusion:

There is currently no ideal lymphedema HRQoL measurement tool available based on the COSMIN criteria. However, our review suggested that LYMQOL and ULL-27 are the most used and most validated instruments at present, but each has their own limitations. We recommend the use of LYMQOL and ULL-27 for future studies to allow direct HRQoL comparison to current literature. Further research is required to develop an optimal HRQoL questionnaire that can ultimately become the gold standard HRQoL instrument for lymphedema.

Takeaways

Question: What quality of life questionnaires are available for patients with lymphedema? Which questionnaire can be used to monitor the extent of the disease burden?

Findings: Eight lymphedema-specific questionnaires are available and have been validated for use in lymphedema. LYMQOL and ULL-27 are the most cited questionnaires.

Meaning: LYMQOL and ULL-27 are the most comprehensive validated instruments at present; however, they are not without limitations. We recommend the use of LYMQOL and ULL-27 for future studies to allow direct HRQoL comparison to current literature. Further research is required to develop an optimal HRQoL questionnaire that can ultimately become the gold standard HRQoL instrument for lymphedema.

INTRODUCTION

Lymphedema is defined as chronic edema due to accumulation of protein-rich fluid following injuries to the lymphatic system.1 Approximately one in 1000 individuals in the population is affected by lymphedema.2 Lymphedema can be classified into primary lymphedema and secondary lymphedema. Primary lymphedema may be present at birth or develop at certain time points in the patients’ natural history.3 Secondary lymphedema is often due to cancer treatment or trauma to the limbs. Treatment for cancer of the breast, gynecological, genitourinary system, and head and neck frequently results in lymphedema.4 Morgan et al.5 reported that 25% of patients with cancer developed lymphedema related to cancer treatment.

Many studies have recognized the debilitating consequences of lymphedema symptoms such as swelling, heaviness, firmness, pain, and impaired limb mobility.5 The effect of lymphedema has a negative impact on patients’ well-being, resulting in a decreased overall health-related quality of life (HRQoL)6.

Lymphedema treatment is a rapidly evolving field. Conservative options include manual lymphatic drainage, intermittent pneumatic therapy and compressive garments.7 Surgical options include liposuction,8 excisional procedures,9 lymphatic bypass,10 lymphovenous anastomoses, and lymph node transfers.10 The use of a standardized and well-validated HRQoL instrument in clinical studies allows for objective assessment of the severity of lymphedema and evaluate the efficacy of treatment for each patient. It will also allow direct comparison of the effectiveness of different treatment options across the affected population. The ideal HRQoL measurement tool should be able to differentiate between individuals who have a better HRQoL and those who have a worse HRQoL, as well as measure how much the HRQoL changes in response to treatment.11 Ferrell et al.12 indicated that it is important to consider the different domains of HRQoL to understand the long-term impact of a disease, which include physical, psychological, social, and spiritual. Furthermore, statisticians evaluate an instrument’s validity and reliability by measuring its psychometric properties.

Numerous HRQoL measurement tools have been used to quantify the effect of lymphedema on patients and to assess the response to lymphedema treatment. This study aims to review all the HRQoL instruments currently used in published lymphedema studies, compare the different features and identify the most comprehensive HRQoL measurement tool that should be used in clinical research for lymphedema.

METHODS

Search Strategy

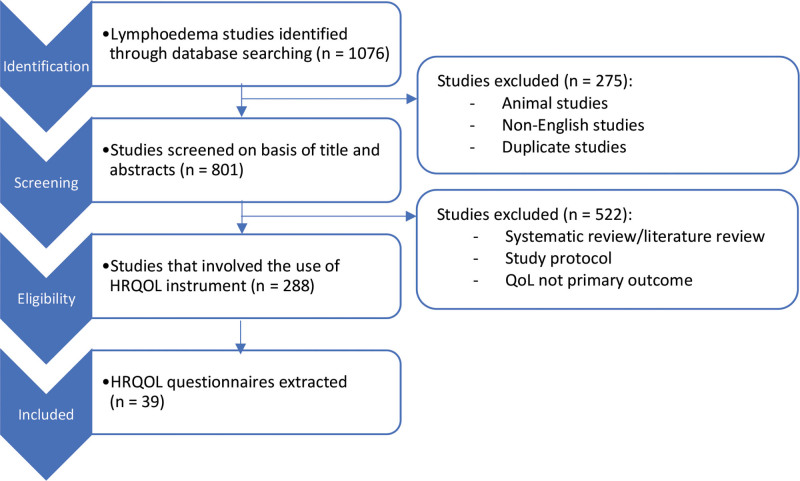

A systematic literature search was conducted as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Pubmed database was searched from January 1, 1984, to February 1, 2020. Search terms included variations of the following: “lymph*dema,” “quality of life,” “health-related quality of life,” “measures,” “scales,” “instruments,” and “questionnaires.” The search was conducted to identify HRQoL measurement tools that have been used to quantify the impact of lymphedema. Once identified, each of the HRQoL tools was reviewed for their psychometric properties and validation in lymphedema. A subsequent search was conducted to identify the number of published lymphedema studies that have utilized each of these HRQoL tools. The literature search process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic presentation of systematic review process.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) studies published in the English language which assessed HRQoL in patients with lymphedema; (2) studies which reviewed correlation between lymphedema severity and HRQoL; and (3) studies that assessed the effect of lymphedema treatment using HRQoL tools. Only studies which have the effects of lymphedema on quality of life as their primary outcome were included. Review articles and study protocols were excluded.

Data Extraction

There are three types of HRQoL measurement tools: generic, disease-specific, and condition-specific. Generic instruments are designed to be applied to a wide range of populations and interventions. Disease-specific instruments measure HRQoL domains specific to a particular disease. Condition-specific instruments are used to evaluate change in specific conditions related to a disease. The following factors were extracted from each HRQoL instruments: the full name and abbreviation of the questionnaire, the type of questionnaire, items, domains, domain description, scaling and scoring, and administration method. Psychometric properties of each instrument were extracted, which include reliability, validity, and responsiveness.13,14

RESULTS

Eligible Studies

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow chart depicting the identification of studies according to their inclusion criteria. We initially identified a total of 1076 clinical lymphedema studies. After the removal of duplicate studies, non-English studies and animal studies, we analyzed abstracts of 801 articles. Subsequently, we excluded 522 studies which were systematic reviews, study protocols, or studies which do not measure HRQoL as their primary outcome. We then assessed the full text of 288 lymphedema studies and identified 39 different HRQoL questionnaires that have been used across these studies.

Validated QoL Instruments in Lymphedema

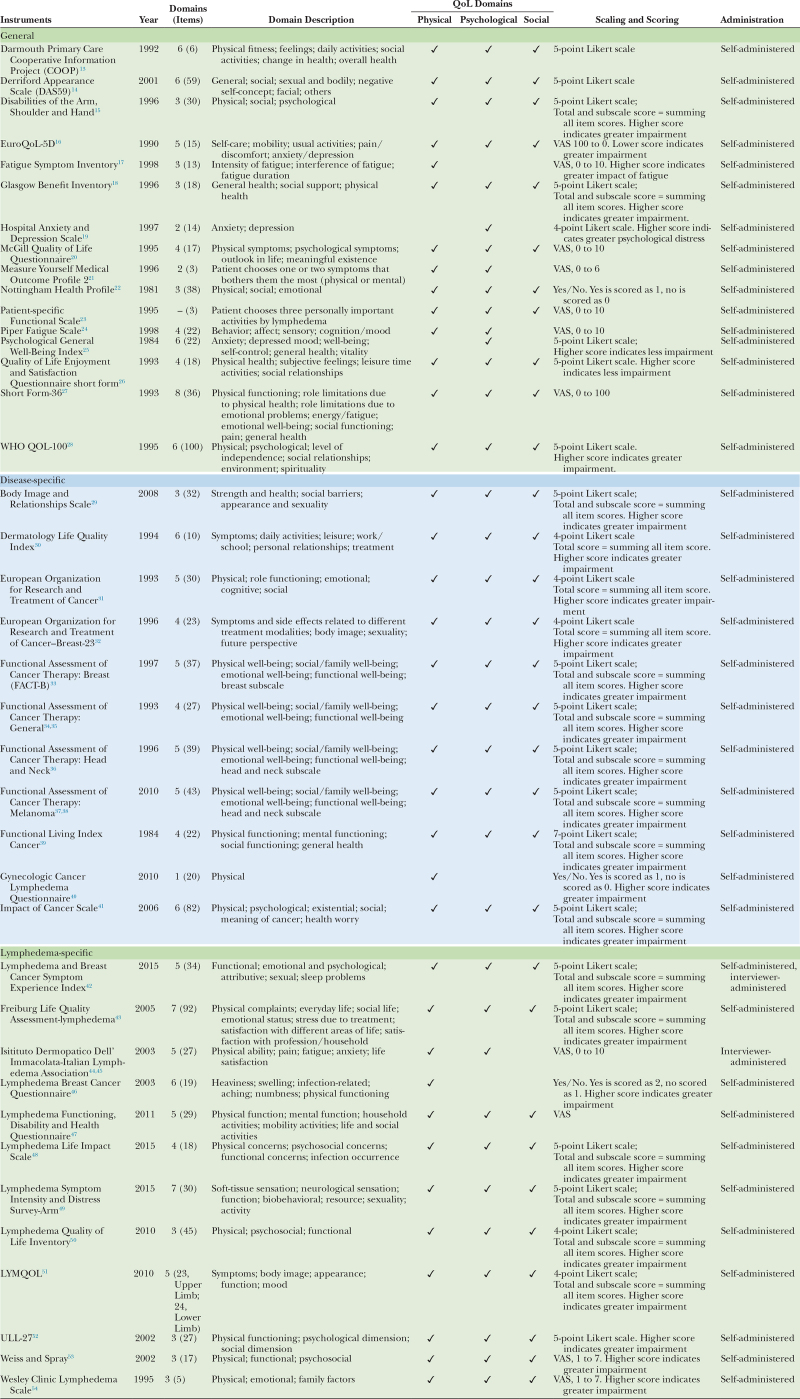

A total of 39 HRQoL instruments were identified and included in the review (16 general, 11 disease-specific, and 12 lymphedema-specific). The instruments varied widely in the number of items and domains, scaling and scoring, and psychometric properties. This is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of Quality of Life Instruments in Patients with Lymphedema

The 39 identified questionnaires were divided into three categories:

- Group I: General health questionnaires; this group consisted of 16 questionnaires.

- Group II: Disease-specific questionnaires; this group consisted of 11 questionnaires.

- Group III: Lymphedema-specific questionnaires; this group consisted of 12 questionnaires.

In group I, 10 of 16 questionnaires reported all three domains (physical, psychological, and social). Two questionnaires reported only physical and psychological domains (MYMOP2 and PFS), two questionnaires reported psychological symptoms only (HADS and PGWB), and one questionnaire reported physical symptoms only (FSI). In terms of scoring, eight questionnaires used the Likert scale, seven questionnaires used the visual analog scale (VAS) and only one questionnaire used categories. All questionnaires in this group were self-administered.

In group II, one of the 11 questionnaires reported physical symptoms only. The rest of the questionnaires reported symptoms from all three domains. In terms of scoring, 10 questionnaires used the Likert scale and one questionnaire used categories. All questionnaires in this group were self-administered.

In group III, 10 of 12 questionnaires reported symptoms from all three domains. IDI-ILA reported physical and psychological symptoms, whereas LBCQ reported physical symptoms only. In terms of scoring, seven questionnaires used Likert scale, four questionnaires used VAS and one questionnaire used categories. Two questionnaires were interviewer-administered.

Of 39 identified questionnaires, eight of the lymphedema-specific questionnaires have been validated for use in lymphedema. Psychometric properties of each questionnaire were reviewed and are summarized in Table 2. Lymphedema-specific questionnaires which have been utilized most frequently are LYMQOL (used in 29 studies, total of 209 patients), and Upper Limb Lymphedema (ULL)-27 (used in 10 studies, total of 304 patients).

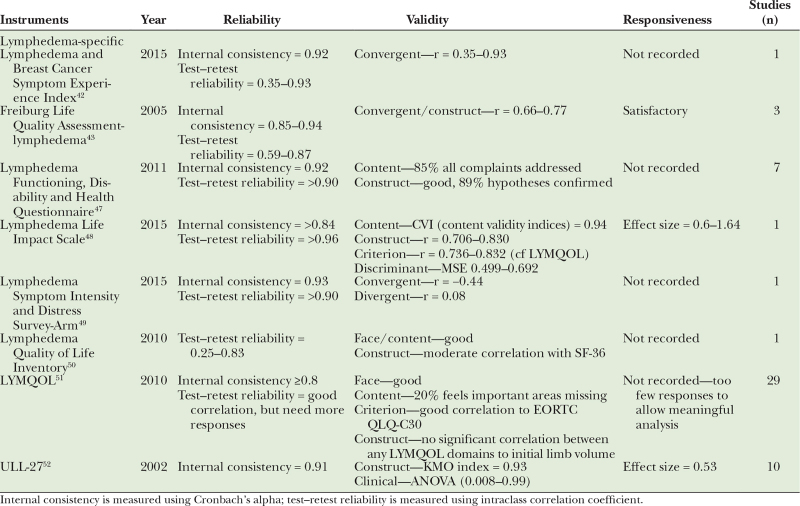

Table 2.

Psychometric Properties of Lymphedema-specific Quality of Life Instruments in Patients with Lymphedema—Validated in Lymphedema

Four questionnaires were validated for use in both primary or secondary lymphedema of upper limbs and/or lower limbs, which are Freiburg Life Quality Assessment-lymphedema, Lymphedema Life Impact Scale, Lymphedema Quality of Life Inventory, and LYMQOL.15–18 The other four questionnaires were specifically developed to assess quality of life in patients with upper limb lymphedema following breast cancer surgery, which are Lymphedema and Breast Cancer Symptom Experience Index, Lymphedema Functioning, Disability and Health Questionnaire, Lymphedema Symptom Intensity and Distress Survey-ARM, and ULL-27 (Table 2).19–22

DISCUSSION

Various questionnaires have been used in clinical studies to evaluate HRQoL in patients with lymphedema. Currently, there is no standardized HRQoL tool in the literature. Of the 39 HRQoL instruments identified, we categorized them into three groups (general, disease-specific, and lymphedema-specific). The general questionnaires (16 tools) are broad and only discriminate between healthy and chronically ill populations.23 They are relatively insensitive to clinical changes in lymphedema.24 The disease-specific questionnaires (11 tools), focus on domains of function most relevant to that particular disease. However, they do not necessarily reflect symptoms that are seen in lymphedema. The lymphedema-specific questionnaires (12 tools), are instruments that have been specifically developed for patients with lymphedema. Of the 12 questionnaires, eight have been validated for use in lymphedema and cover the relevant HRQoL domains. This is summarized in Table 2. In particular, LYMQOL and ULL-27 are the most common instruments used in the current published literature.

To adequately measure quality of life, the questionnaire should include symptoms important to the disease it is measuring and it should have good psychometric properties.14 Morgan et al5 conducted a systematic review and concluded that pain and discomfort were the symptoms which significantly affect HRQoL of patients with lymphedema. However, in clinical practice, the pain described by patients can be neuropathic pain relating to their previous cancer treatment rather than from the lymphedema itself. Furthermore, patients found lymphedema and its treatment disruptive to their social, emotional and working lives.5 Other symptoms experienced by patients include sensation of tightness, heaviness and limited range of motion of the affected limb, which are evaluated in all eight lymphedema-specific questionnaires.

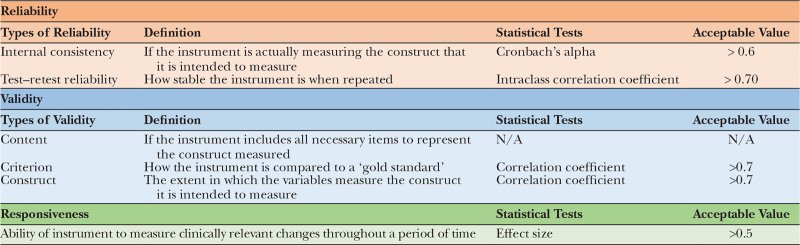

In terms of psychometric properties, the COSMIN study25 described standardized terminology and definitions of the ideal HRQoL measurement tool. Reliability, validity and responsiveness are the three domains to be assessed when developing the HRQoL instrument (Table 3).

Table 3.

COSMIN Psychometric Properties of an Instrument

Reliability

Reliability refers to how stable, consistent, or accurate an instrument is.26 It can be assessed by measuring internal consistency and test–retest reliability.25 Internal consistency demonstrates if all components of an instrument measure the same characteristic and is most frequently assessed through Cronbach’s alpha coefficient26 (values between 0.60 and 0.70 are considered satisfactory27).

Reliability can also be gauged using test–retest reliability, which assesses the similarity of results when measured at two different times.26 Intraclass correlation coefficient is the most used test to measure test–retest stability, with a minimum value of 0.70 considered as satisfactory.28

Validity

Validity is used to assess whether an instrument measures exactly what it proposes to measure, which include content validity, criterion validity, and construct validity. Content validity evaluates how much the items sampled represent in a defined universe or content domain, in this case lymphedema. There is no statistical test to assess content validity, thus researchers usually use a qualitative method such as experts committee assessment and a quantitative method using the content validity index (CVI).26

Criterion validity refers to the relationship between the score of the instrument and an external criterion, typically an instrument that is considered “gold standard.”29 In lymphedema HRQoL, there is currently no “gold standard” tool to compare to. In which case, the criterion validity can be measured using a correlation coefficient, with values equal to 0.70 or more regarded as acceptable.30

Construct validity indicates how well the instrument represents the construct to be measured. To measure it, researchers look at convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity is obtained through correlation between the instrument that is being assessed and another instrument that measures a similar construct, expecting a high correlation between them.31 Discriminant validity measures the degree to which one construct differs from the other. For example, an instrument that assesses motivation to work should show low correlation with an instrument that measures self-efficiency.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness is defined as the ability of an instrument to detect clinically important changes over time, which can be measured using effect size. According to Cohen,32 a value of less than 0.2 is considered trivial, 0.2–0.5 is a small effect, 0.5–0.8 is a moderate effect, and greater than 0.8 is a large effect.

Lymphedema-specific Questionnaires

Based on our review, we focus the discussion on two lymphedema-specific questionnaires, which are LYMQOL and ULL-27. The two questionnaires cover all the quality of life domains, have been validated in lymphedema and are the most cited instruments used to measure HRQoL in lymphedema studies based on the current published literature.

LYMQOL

LYMQOL was developed in 2010 by United Kingdom–based lymphologist Dr. Vaughan Keeley and colleagues.19 It consists of separate tools developed for arm and leg lymphedema, each containing 24 and 23 items, respectively. The instrument has been used in 29 studies and has been validated in a total of 209 patients. Participants found the questionnaire easy to complete and 92% of participants felt that all questions were important.19 The tool was deemed reliable with a Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.8 and validity was supported in face, content, and criterion domains. However, in terms of construct validity, there was no correlation between initial limb volume and LYMQOL score. Responsiveness was not reported due to a limited number of responses at 3 and 6 months after the initial assessment. This is a major drawback on using LYMQOL as responsiveness is considered one of the major advantages of a disease-specific questionnaire in comparison to a generic questionnaire. An instrument that has poor responsiveness (poor ability to detect change following treatment) can result in false-negative outcomes on the effect of treatment.33

Upper Limb Lymphedema-27

ULL-27 was developed in 2002 by Launois et al18 in France. As the name suggests, the tool consists of 27 questions on ULL across three domains (physical functioning, psychological dimension, and social dimension). It has been used in 10 lymphedema studies and was validated in a total of 304 patients. The tool is reliable (internal consistency = 0.91), valid (both in construct and clinical), and responsive (effect size = 0.53). Interestingly, their findings suggest that the volume of upper limb edema poorly reflects the impact of the condition on patients’ quality of life. ULL-27 was developed to assess upper limb lymphedema following breast cancer surgery, and thus is not able to be used for patients with lower limb lymphedema.

Our search identified 288 published clinical lymphedema studies, which assessed quality of life using HRQoL measurement tools. Although patient-reported outcome is a commonly used metric to measure outcome following treatment for lymphedema, the limited ability to measure this outcome makes it challenging to objectively compare the effect of lymphedema treatment and monitor clinical progression. Our study showed that LYMQOL and ULL-27 are the two most cited and comprehensive lymphedema-specific questionnaires. However, they do not represent the optimal questionnaire as outlined by the COSMIN checklist.34 According to the COSMIN checklist, the ideal HRQoL measurement tool should include content validity, structural validity, internal consistency, cross-cultural validity, reliability, measurement error, criterion validity, hypotheses testing for construct validity, and responsiveness. Based on our findings outlined in Table 2, reliability and internal consistency have been measured appropriately among the available lymphedema-specific questionnaires. However, responsiveness could be investigated further to create a more comprehensive HRQoL measurement tool. In particular, LYMQOL has not been validated for responsiveness. On the other hand, although ULL-27 covers the COSMIN checklist, the tool is specifically developed for upper limb lymphedema only. This precludes the questionnaire to be used in lower limb lymphedema, which constitutes a high percentage of lymphedema patients. There is also selection bias in terms of which questionnaire is used by clinical studies based on the available literature. For example, the Lymphedema Life Impact Scale is a relatively new questionnaire and as such is less likely to have been implemented in studies compared to other questionnaires which were developed earlier.

At present, there is currently no ideal HRQoL questionnaire available for lymphedema as per the COSMIN criteria. Based on our literature review, LYMQOL and ULL-27 are the best compromise at this stage. We suggest the use of these two questionnaires in future studies to allow direct comparison of HRQoL to previously published literature. In contrast, using a variety of questionnaires in different studies will make it difficult to directly compare clinical progression and evaluate the effects of different lymphedema treatments. Newer questionnaires which are being developed, such as LYMPH-Q,35 may eventually become a more appropriate questionnaire to use.

CONCLUSIONS

Lymphedema significantly impacts patients’ HRQoL. According to the COSMIN criteria, there is no ideal questionnaire yet among the currently available lymphedema-specific HRQoL tools. LYMQOL and ULL-27 are the most commonly used and validated questionnaires; however, they have their own limitations. Nonetheless, we recommend the use of LYMQOL and ULL-27 for future research as they are the two best tools currently available that allow direct comparison to previous studies. Further research is required to develop the ideal HRQoL measurement tool for lymphedema.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, et al. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:500–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moffatt CJ, Franks PJ, Doherty DC, et al. Lymphoedema: an underestimated health problem. QJM. 2003;96:731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockson SG, Rivera KK. Estimating the population burden of lymphedema. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cormier JN, Askew RL, Mungovan KS, et al. Lymphedema beyond breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cancer-related secondary lymphedema. Cancer. 2010;116:5138–5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan PA, Franks PJ, Moffatt CJ. Health-related quality of life with lymphoedema: a review of the literature. Int Wound J. 2005;2:47–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velanovich V, Szymanski W. Quality of life of breast cancer patients with lymphedema. Am J Surg. 1999;177:184–187; discussion 188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Földi E, Földi M, Weissleder H. Conservative treatment of lymphoedema of the limbs. Angiology. 1985;36:171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brorson H, Svensson H. Complete reduction of lymphoedema of the arm by liposuction after breast cancer. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1997;31:137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson N. Surgical treatment of chronic lymphoedema of the lower limb. With preliminary report of new operation. Br Med J. 1962;2:1566–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, Yuan L, Chen X, et al. Current treatments for breast cancer-related lymphoedema: a systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:4875–4883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higginson IJ, Carr AJ. Measuring quality of life: using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ. 2001;322:1297–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muldoon MF, Barger SD, Flory JD, et al. What are quality of life measurements measuring? BMJ. 1998;316:542–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu MR, Axelrod D, Cleland CM, et al. Symptom report in detecting breast cancer-related lymphedema. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2015;7:345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devoogdt N, Van Kampen M, Geraerts I, et al. Lymphoedema functioning, disability and health questionnaire (Lymph-ICF): reliability and validity. Phys Ther. 2011;91:944–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridner SH, Dietrich MS. Development and validation of the lymphedema symptom and intensity survey-arm. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:3103–3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Launois R, Megnigbeto AC, Pocquet K, et al. A specific quality of life scale in upper limb lymphedema: the ULL-27 questionnaire. Lymphology. 2002;35:181–187. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keeley V, Crooks S, Locke J, et al. A quality of life measure for limb lymphoedema (LYMQOL). J Lymphoedema. 2010;5:26–37. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klernäs P, Johnsson A, Horstmann V, et al. Lymphedema Quality of Life Inventory (LyQLI)-development and investigation of validity and reliability. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:427–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Augustin M, Bross F, Földi E, et al. Development, validation and clinical use of the FLQA-l, a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire for patients with lymphedema. Vasa. 2005;34:31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss J, Daniel T. Validation of the Lymphedema Life Impact Scale (LLIS): a condition-specific measurement tool for persons with lymphedema. Lymphology. 2015;48:128–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrick DL, Deyo RA. Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Med Care. 1989;27(Suppl 3):S217–S232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacKeigan LD, Pathak DS. Overview of health-related quality-of-life measures. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49:2236–2245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Souza AC, Alexandre NMC, de Brito Guirardello E. Psychometric properties in instruments evaluation of reliability and validity. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2017;26:649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Streiner DL. Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J Pers Assess. 2003;80:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimberlin CL, Winterstein AG. Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:2276–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polit DF, Beck CT. Fundamentos de pesquisa em enfermagem: avaliação de evidências para a prática da enfermagem. Artmed Editora; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polit DF. Assessing measurement in health: Beyond reliability and validity. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1746–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.List MA, D'Antonio LL, Cella DF, et al. The performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients and the functional assessment of cancer therapy‐head and neck scale: a study of utility and validity. Cancer. 1996;77:2294–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Askew RL, Swartz RJ, Xing Y, et al. Mapping FACT-melanoma quality-of-life scores to EQ-5D health utility weights. Value Health. 2011;14:900–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Askew RL, Xing Y, Palmer JL, et al. Evaluating minimal important differences for the FACT‐Melanoma quality of life questionnaire. Value Health. 2009;12:1144–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schipper H, Clinch J, McMurray A, et al. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: the functional living index-cancer: development and validation. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:472–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim MC, Lee JS, Joo J, et al. Development and evaluation of the Korean version of the Gynecologic Cancer Lymphedema Questionnaire in gynecologic cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zebrack BJ, Ganz PA, Bernaards CA, et al. Assessing the impact of cancer: development of a new instrument for long-term survivors. Psychooncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer. 2006;15:407–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu MR, Axelrod D, Cleland CM, et al. Symptom report in detecting breast cancer-related lymphedema. Breast Cancer: Targets Ther. 2015;7:345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Augustin M, Bross F, Földi E, et al. Development, validation and clinical use of the FLQA-l, a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire for patients with lymphedema. Vasa. 2005;34:31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cemal Y, Jewell S, Albornoz CR, et al. Systematic review of quality of life and patient reported outcomes in patients with oncologic related lower extremity lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol. 2013;11:14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carmeli E, Bartoletti R. Retrospective trial of complete decongestive physical therapy for lower extremity secondary lymphedema in melanoma patients. Supportive Care Cancer. 2011;19:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armer JM, Radina ME, Porock D, et al. Predicting breast cancer-related lymphedema using self-reported symptoms. Nurs Res. 2003;52:370–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Devoogdt N, Van Kampen M, Geraerts I, et al. Lymphoedema functioning, disability and health questionnaire (Lymph-ICF): Reliability and validity. Phys. Ther. 2011;91:944–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weiss J, Daniel T. Validation of the Lymphedema Life Impact Scale (LLIS): a condition-specific measurement tool for persons with lymphedema. Lymphology. 2015;48:128–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ridner SH, Dietrich MS. Development and validation of the lymphedema symptom and intensity survey-arm. Supportive Care Cancer. 2015;23:3103–3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klernas P, Kristjanson L, Johansson K. Assessment of quality of life in lymphedema patients: validity and reliability of the Swedish version of the Lymphedema Quality of Life Inventory (LQOLI). Lymphology. 2010;43:135–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keeley V, Crooks S, Locke J, et al. A quality of life measure for limb lymphoedema (LYMQOL). J Lymphoedema. 2010;5:26–37. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Launois R, Megnigbeto AC, Pocquet K, et al. A specific quality of life scale in upper limb lymphedema: the ULL-27 questionnaire. Lymphology. 2002;35:181–187. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiss J, Spray B. The effect of complete decongestive therapy on the quality of life of patients with peripheral lymphedema. Lymphology. 2002;35:46–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mirolo BR, Bunce IH, Chapman M, et al. Psychosocial benefits of postmastectomy lymphedema therapy. Cancer Nursing. 1995;18:197–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]