Abstract

Integrins are a family of transmembrane receptors that connect the extracellular matrix and actin skeleton, which mediate cell adhesion, migration, signal transduction, and gene transcription. As a bi-directional signaling molecule, integrins can modulate many aspects of tumorigenesis, including tumor growth, invasion, angiogenesis, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance. Therefore, integrins have a great potential as antitumor therapeutic targets. In this review, we summarize the recent reports of integrins in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), focusing on the abnormal expression, activation, and signaling of integrins in cancer cells as well as their roles in other cells in the tumor microenvironment. We also discuss the regulation and functions of integrins in hepatitis B virus-related HCC. Finally, we update the clinical and preclinical studies of integrin-related drugs in the treatment of HCC.

Keywords: Integrins, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Antitumor therapy

Introduction

Human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, and the incidence of HCC has been on the rise in recent decades.[1,2] Current treatment options include liver transplantation or surgical resection, while first-line chemotherapeutic agents include sorafenib, lenvatinib, atezolizumab, and bevacizumab.[3] While with a 5-year survival rate of >70% identified in early-stage disease, unfortunately, most patients have been diagnosed with advanced HCC, with a very low long-term survival rate.[4] Furthermore, HCC often develops resistance to conventional chemotherapy, which ultimately leads to a poor clinical prognosis.[5] As tumorigenesis and tumor progression in hepatocytes is a consequence of multiple genetic alterations, the single-molecule targeted therapies have not been identified.[3] Combination therapies are often applied to HCC treatment, amplifying the patients’ side effects. Therefore, it is important to identify target molecules that control the biological properties of HCC.

Integrins are a family of widespread cell membrane adhesion receptors, belonging to type I transmembrane proteins. To date, a total of 18 α and 8 β subunits have been identified, which can form 24 known heterodimers by non-covalent association.[6] Generally, α subunits offer ligand specificity to the integrins, while β subunits acquire several signaling transduction modules. Each subunit has a large ectodomain, a single transmembrane domain, and a comparatively short cytoplasmic tail. The globular head domain creates a binding site for extracellular ligands, while the cytoplasmic tails serve as a nucleation center for integrin and intercellular protein interactions.[7] Depending on their ligand-binding specificity, integrins can be categorized into four main groups: (1) leukocyte-specific receptors (α4β1, α9β1, α4β7, αEβ7, αLβ2, αMβ2, αXβ2, and αDβ2); (2) laminin-binding receptors (α6β4, α3β1, α6β1, and α7β1); (3) collagen-binding receptors that recognize the GFOGER sequence (α1β1, α2β1, α10β1, and α11β1); and (4) receptors that recognize the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif (α5β1, α8β1, αVβ1, αVβ3, αVβ5, αVβ6, αVβ8, and αIIbβ3).[8] The RGD is the minimum sequence required for integrins’ recognition of their aforementioned ligands, existing in various extracellular matrix (ECM) such as fibrinogen, fibronectin, and vitronectin.[9] Integrins do not only bind to the natural ECM, but also interact with various proteins, including hormones, growth factors, and polyphenols on the surfaces of cells, even on fungal cells and viruses.[9,10] Here, we summarize the recent reports of integrins in human HCC, focusing on the abnormal expression, activation, and signaling of integrins in cancer cells as well as their roles in other cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME). We also discuss the regulation and functions of integrins in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related HCC. Finally, we discuss the current status and therapeutic strategies of anti-integrin drugs in preclinical and clinical practice to combat life-threatening cancer.

Integrin Activation and Signaling Transmission

Integrin activation

Integrin activation is a process of reversible and flexible conformational changes.[11–13] During the resting state, the integrin ligand-binding head faces the membrane and the intracellular tails are clasped. Upon activation, the integrin head extends, the ligand-binding site opens, and the intracellular integrin tails separate.[14,15] Recent studies have shown that integrins exist in three conformations: bent-closed (inactive), extended-closed (active, low affinity), and extended-open (active, high affinity).[16] The delicate balance between different integrin conformations can regulate cell adhesion affinity and signaling strength.[9]

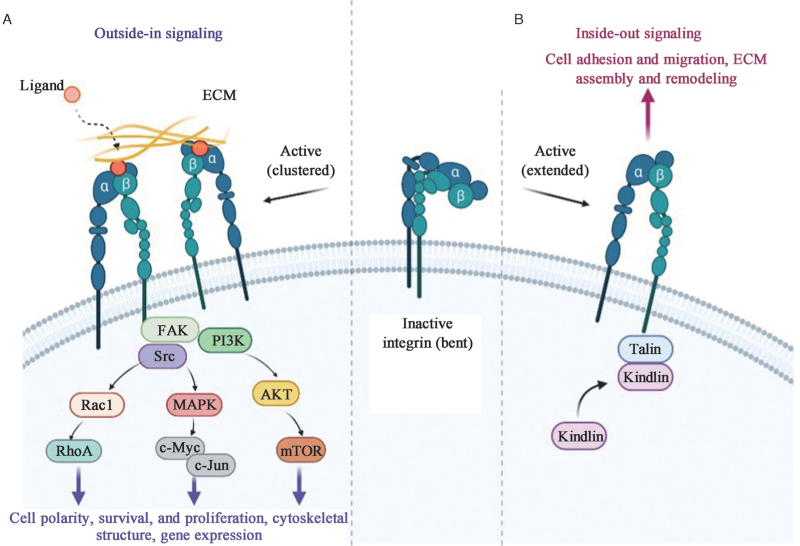

As a family of unique transmembrane receptors, integrins can activate bi-directional signaling, referred to as “inside-out” signaling and “outside-in” signaling [Figure 1]. In “inside-out” signaling, intracellular activators like talins or kindlins bind to the cytoplasmic tail of their β-subunits, triggering the conformational changes of integrins and recruiting multivalent protein complexes clustering, which increases their affinity for ligands and thus promotes cell migration and ECM assembly and remodeling.[11,17,18] In the opposite direction of “outside-in” signaling, integrin receptors for ECM components and other ligands, such as growth factor receptors (GFRs), urokinase plasminogen activator receptor, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) receptor, bind to the external integrin domains, leading to integrin clustering and sending signals into the cells, changing the cell polarity and cytoskeletal structure, inducing gene transcription, and promoting cell survival and proliferation.[19,20] Recent studies have found that endocytosed integrins also have certain functions as “inside-in” signaling, which can exert a specific role by recruiting focal adhesion kinase (FAK) or enhancing the signaling of the co-trafficking GFRs,[21] but such signaling has not been observed in HCC. In a word, integrins can make human cells respond to changes in the extracellular environment and can affect the extracellular environment itself through bi-directional signaling.

Figure 1.

Integrin “outside-in” signaling and “inside–out” signaling. Integrins exist in different conformations that determine the receptor affinity of ECM components and other ligands: from bent closed (inactive) to extended open (active high affinity). (A) “Outside-in” signaling: When bound to ECM proteins, integrins are activated and clustered, and trigger downstream signals, of which the most well-studied is the FAK signaling pathway, with subsequent recruitment and activation of the Src. Ultimately, cell behavior is affected through crosstalk with many other signaling effectors. (B) “Inside–out” signaling: In the active state, the binding of talins to the β-integrin tail triggers a conformational switch to an extended open state and further recruitment of integrin-activated proteins, such as kindlins, which can initiate functions including cell adhesion, migration, ECM assembly, and remodeling. AKT: Protein kinase B; ECM: Extracellular matrix; FAK: Focal adhesion kinase; MAPK: Mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTOR: Mammalian target of rapamycin; PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; RhoA: Ras homolog gene family member A.

Signaling transmission

To date, FAK-mediated signaling is the best-characterized integrin pathway.[22] Specifically, when integrins bind to the ECM to send “outside-in” signaling, the non-receptor tyrosine kinase FAK is a key signaling effector that binds to most integrins, triggering FAK tyrosine (Tyr) 397 autophosphorylation, which creates a binding site for the Src kinase domains Src homology 2 (SH2) and SH3. Phosphorylation of proto-oncogene kinase Src leads to maximal FAK activation, and the activated FAK-Src complex promotes multiple key signaling cascades.[23] For example, FAK recruits the growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (GRB2) and actives mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade to activate several transcription factors such as the oncogenic c-Myc and c-Jun via phosphorylation, thereby promoting cell cycle progression and growth.[24,25] FAK can also interact with phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), which leads to the activation of protein kinase B (AKT), and then promotes cell migration and invasion.[26,27] In addition, FAK- and Src-regulated Rac and Cdc42 signaling can activate actin-related protein-2/3 (ARP2/3) complex and LIM kinase to induce actin polymerization during the early stages of cell spreading.[28] Similarly, aberrations of the above pathways are common in HCC. For example, integrin β4 interacts with the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) to activate the FAK/AKT signaling pathway and promote HCC metastasis.[29] In addition, signaling pathways that negatively regulate integrins are also present in HCC. For example, dermatopontin inhibits integrin α3β1 activation and decreases Ras homolog gene family member A (RhoA) activity, as well as FAK and Src phosphorylation, ultimately preventing HCC metastasis.[30] The signaling pathways of integrins in HCC are briefly summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Integrin-related positively regulated signaling pathways in HCC.

| Integrins | Ligands/signaling partners | Function | References |

| β1 | Integrin β1/PXN/YWHAZ/AKT | Drive HCC progression by modulating the cell cycle process | [31] |

| THBS4-integrin β1/FAK/PI3K/AKT | Promote HCC development | [32] | |

| N-glycosylation by N-acetylglucosaminyl-transferase V/CD147/basigin-integrin β1 | Promote HCC metastasis | [33] | |

| Collagen I/integrin β1/FAK | Promote HCC cells proliferation | [34] | |

| IER2/integrin β1/FAK/Src/paxillin | Contribute to the HCC cell–ECM adhesion and motility | [35] | |

| CAS/integrin β1 | Promote HCC cells migration and invasion | [36] | |

| Integrin β1/ILK-AKT | Promote EMT, chemo-resistance, and radio-resistance of liver epithelial cells | [37] | |

| HAb18G/CD147-integrin β1 | Promote radio-resistance | [38] | |

| Prostaglandin E2/EP1/PKC/NF-κB/integrin β1 | Promote HCC cells migration | [39] | |

| C1GALT1/integrin β1 glycosylation | Promote invasive phenotypes | [34] | |

| Androgen receptor/integrin β1/AKT | Enhance HCC cells adhesion and decrease HCC cells migration | [40] | |

| HAb18G/CD147-integrin β1 | Enhance the malignant properties of HCC cells | [41] | |

| ANGPTL4/VCAM-1/integrin β1 | Contribute to HCC metastasis | [42] | |

| Thrombin/integrin β1/FAK | Play an important role in OPN-mediated aggressive phenotype | [43] | |

| OPN-integrin β1/NF-κB | Promote HCC growth and metastasis | [44] | |

| Integrin β1/MAPK | Contribute to chemotherapy resistance | [45] | |

| IGFBP2/integrin β1/FAK/ERK/EGR1 | Promote proliferation | [46] | |

| ADAM17/Notch1/integrin β1 | Promote cell migration and invasion | [47] | |

| Activated HSCs/POSTN/integrin β1/p52Shc and ERK1/2 | Accelerate progression of residual HCC after suboptimal heat treatment | [48] | |

| Integrin β1/FAK/AKT | Promote multicellular resistance | [49] | |

| α2 | IRS-4/integrin α2/FAK | A gain in migratory and invasive capacities | [50] |

| ADAR1 p110/integrin α2 | Enhance adhesion of HCC cells | [51] | |

| α2β1 | Integrin α2β1/MST1/YAP | Promote YAP-positive HCC development | [52] |

| α3 | Ln-332/integrin α3/FAK | Induce HCC cells’ resistance to sorafenib | [53] |

| α3β1 | Ln-5/integrin α3β1/ERK | Stimulate HCC growth | [54] |

| α5 | Sec62/integrin α5/CAV1 | Promote HCC metastasis and early recurrence | [55] |

| α5β1 | Ang-2/integrin α5β1/FAK | Regulate vessels encapsulated by tumor clusters positive HCC nest-type metastasis | [56] |

| uPAR (D1D2)-integrin α5β1 | Causes malignant transformation of hepatic cells and the occurrence of HCC | [57] | |

| CD147-integrin α5β1/E-cadherin/β-catenin translocation | Promote hepatocyte depolarization | [58] | |

| α6β1 | Integrin α6β1/FAK/MAPK | Necessary for FAK/MAPK-dependent migration | [59] |

| CD151/integrin α6β1/PI3K | Induce the EMT in HCC cells | [60] | |

| α6β4 | Exosome-derived ENO1/integrin α6β4/FAK/Src-P38MAPK | Promote the growth and metastasis of HCC cells | [61] |

| Ln-5/integrin α6β4/ERK | Stimulate HCC growth | [54] | |

| α7 | Integrin α7/PTK2/PI3K/AKT | Promote HCC cells proliferation, apoptosis, and stemness | [62] |

| αV | TAZ/integrin αV/YAP/TAZ | Regulate HCC cells invasion and feed back positively | [63] |

| SIN3B/HDAC2/integrin αV | Promote HCC cells migration | ||

| BRD1/Sulfatide/SP1/Integrin αV | Promote integrin αV gene expression | [64] | |

| Sec62/integrin αV/CAV1 | Promote HCC metastasis and early recurrence | [55] | |

| αVβ3 | OPN-integrin αVβ3/NF-κB | Promote HCC growth and metastasis | [44] |

| OPN-integrin αVβ3/FoxO3a | Induce autophagy to promote chemo-resistance | [46] | |

| Nogo-B-integrin αVβ3/FAK | Promote HCC angiogenesis | [65] | |

| Sulfatide-integrin αVβ3/FAK/Src | Trigger outside-in signaling | [66] | |

| Galectin-1/integrin αVβ3/PI3K/AKT | Induce HCC EMT and sorafenib resistance | [67] | |

| SM3/vitronectin-integrin αVβ3 | Enhance HCC cell adhesion and intrahepatic metastasis | [68] | |

| Cat B/integrin αVβ3/PI3K/AKT | Induce HCC progression | [69] | |

| POSTN/integrin αVβ3/FAK/STAT3/POSTN circuit POSTN/integrin αVβ3/FAK/ERK |

Promote HSC activation and HCC cell proliferation | [70] | |

| EDIL3-integrin αVβ3/ERK/TGF-β | Promote migration, invasion, and angiogenesis | [32] | |

| αVβ5 | KRASV12/fibrinogen-integrin αVβ5 | Activate HSC | [71] |

| POSTN/integrin αVβ5/FAK/STAT3/POSTN circuit | Promote HCC cells proliferation | [70] | |

| αMβ2 | M2 exos/integrin αMβ2/MMP9 | Support HCC cells migration | [72] |

| β3 | TGF-β1/H2O2/HOCl | Induction of metastatic phenotype of HCC | [73] |

| β4 | Integrin β4/Slug/AKT/Sox2-Nanog | Promote HCC cells invasion and EMT | [74] |

| Integrin β4/EGFR/FAK/AKT | Promote HCC lung metastases | [29] | |

| ZKSCAN3/integrin β4/FAK/AKT | Promote HCC cells EMT | [75] |

ADAM17: ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17; ADAR1: Adenosine deaminases acting on RNA 1; AKT: Protein kinase B; Ang-2: Angiopoietin-2; ANGPTL4: Angiopoietin like 4; BRD1: Bromodomain containing protein 1; CAV1: Caveolin1; C1GALT1: Core 1 β1,3-galactosyltransferase; CAS: Cellular apoptosis susceptibility; ECM: Extracellular matrix; EDIL3: Epidermal growth factor-like repeat and discoidin I-like domain-containing protein 3; EGFR: Epidermal growth factor receptor; EGR1: Early growth response protein 1; EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ENO1: Enolase 1; EP1: Prostaglandin E2 receptor 1; ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FAK: Focal adhesion kinase; FoxO3a: Forkhead box protein O transcription factors 3a; HCC: Human hepatocellular carcinoma; HDAC2: Histone deacetylase 2; H2O2: Hydrogen peroxide; HOCl: Hypochlorous acid; HSCs: Hepatic stellate cells; IER2: Immediate early response protein 2; IGFBP2: Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2; ILK: Integrin-linked kinase; IRS-4: Insulin receptor substrate-4; MST1: Mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1; KRAS: Kirsten rat sarcoma; Ln-332: Laminin-332; Ln-5: Laminin-5; M2 exos: Macrophage-derived exosomes; MAPK: Mitogen-activated protein kinase; MMP9: Matrix metalloproteinase-9; MST1: Mammalian STE20-like kinase 1; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-kappa B; OPN: Osteopontin; PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PKC: Protein kinase C; POSTN: Periostin; PTK2: Protein tyrosine kinase 2; PXN: Paxillin; SIN3B: Paired amphipathic helix protein Sin3b; SM3: Lactosylsulfatide; SP1: Stimulatory protein 1; STAT3: Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TAZ: PDZ-binding motif; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-β; THBS4: Thrombospondin 4; uPAR: Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor; VCAM-1: Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; YAP: Yes-associated protein; YWHAZ: 14-3-3 protein zeta; ZKSCAN3: Zinc finger with KRAB and SCAN domains 3.

Table 2.

Integrin-related negatively regulated signaling pathways in HCC.

| Integrins | Ligands/signaling partners | Function | References |

| β1 | CD98-ICD/integrin β1 | Inhibit HCC progression | [76] |

| SERPINA5/fibronectin-integrin β1 | Inhibit tumor cells migration | [77] | |

| α1β1 | ANGPTL1-integrin α1β1/FAK/Src/JAK/STAT3 | Suppress HCC angiogenesis and metastasis | [78] |

| α3β1 | DPT/integrin α3β1/Rho GTPase | Inhibit HCC metastasis | [30] |

| α4β1 | SPON2/integrin α4β1/Rho GTPase-Hippo pathways | Promote M1-like macrophage recruitment | [75] |

| α5β1 | Fibulin-5-integrin α5β1 | Block HCC angiogenesis | [79] |

| HM-3-HSA/HUVEC-integrin α5β1 | Exhibit potent anti-angiogenesis and antitumor activity in HCC | [80] | |

| α6 | CCN1/integrin α6/ROS/p53 | Inhibit the compensatory proliferation of HCC | [81] |

| αVβ3 | HM-3-HSA/HUVEC-Integrin αVβ3 | Exhibit potent anti-angiogenesis and antitumor activity in HCC | [80] |

| Fibulin-5-integrin αVβ3 | Inhibit HCC adhesion, migration, and invasion | [79] | |

| αVβ5 | Fibulin-5-integrin αVβ5 | Inhibit HCC adhesion, migration, and invasion | [79] |

| β3 | NDRG1/integrin β3 | Inhibit the proliferation and invasion of HCC | [82] |

| α9 | Integrin α9/FAK/Src-Rac1/RhoA signaling | Prevent HCC cells migration and invasion | [83] |

ANGPTL1: Angiopoietin like 1; CCN1: Cellular communication network factor 1; CD98-ICD: Intracellular domain of CD98; DPT: Dermatopontin; FAK: Focal adhesion kinase; HCC: Human hepatocellular carcinoma; HSA: human serum albumin; HUVEC: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells; JAK: Janus kinase; NDRG1: N-Myc down regulated gene 1; RhoA: Ras homolog gene family member A; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; SERPINA5: Serpin family A member 5; SPON2: Spondin 2; STAT3: Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

Altered Expression of Integrins in HCC

Given the fact that the aberrant expression of multiple integrins involved in HCC development, as well as their capacity to cross-talk with growth factors and other signaling molecules, targeting integrins has been considered an attractive approach for anti-cancer therapy. The aberrant expression of integrins occurs at different levels, including transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational dysregulations. In this section, we first highlight the integrins that are significantly altered in HCC and the specific functions of these integrins in Table 3.

Table 3.

Aberrant expression of integrins in HCC.

| Integrins | Altered expression observed in HCC | Associated phenotypes | References |

| α1β1 | ↑ | Promote adhesion, invasion, and metastasis in HCC | [84] |

| α2β1 | ↑ | Promote cellular polarity and adhesion in HCC; gain in migratory and invasive capacities; accelerate cell cycle and promote tumorigenesis | [52,84,85] |

| α3β1 | ↑ | Induce HCC cells’ resistance to sorafenib | [53] |

| α4β1 | ↓ | Promote M1-like macrophage recruitment | [86] |

| α5β1 | ↓ | Inhibit HCC metastasis; promote hepatocyte depolarization | [56,58] |

| α6β1 | ↑ | Induce the EMT and migration in HCC cells | [87] |

| α7β1 | ↑ | Promote HCC cells proliferation, apoptosis, and stemness | [62] |

| α9β1 | ↓ | Prevent HCC cells migration and invasiveness | [83] |

| αVβ3 | ↑ | Promote HCC metastasis and angiogenesis; induce autophagy to promote chemo-resistance; induce HCC EMT and sorafenib resistance | [67,69] |

| α6β4 | ↑ | Promote the growth and metastasis of HCC cells | [61] |

| αVβ5 | ↑ | Promote HCC cells proliferation; drive HCC angiogenesis | [70,88] |

EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; HCC: Human hepatocellular carcinoma.

Regulation at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels

As we know, gene transcription is controlled by the interaction between transcription factors and epigenetic modification. Functional analysis showed that promoter regions of integrins contain binding sites for E-twenty six (ETS), immediate early response protein 2 (IER2), and zinc finger with KRAB and SCAN domains 3 (ZKSCAN3) transcription factors in HCC.[35,75,89] Katabami et al[89] demonstrated that TGF-β1 upregulates transcription of integrin α3 gene in HCC cells via ETS-transcription factor-binding motif in its promoter region. Xu et al[35] identified that IER2 promotes HCC cell adhesion and motility probably by transcriptionally promoting integrin β1 expressin. Besides, Li et al[75] showed that ZKSCAN3, a zinc-finger transcription factor, enhances integrin β4 expression by directly binding to the integrin β4 promoter. It has been reported that methionine adenosyltransferases 2A (MAT2A) upregulates integrin β3 expression by directly binding to integrin β3 promoter, which promotes HCC metastasis.[90] Altered histone modifications are also critical epigenetic regulations in gene transcription. For example, paired amphipathic helix protein (SIN3B) is a transcription corepressor for many genes. Cai et al[91] found that sulfatide induces the conformational change of SIN3B from compacted α-helices to a relaxed β-sheet in the PAH2 domain, impairing SIN3B binding with mitotic arrest deficient 1 (MAD1) and histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2), which reduces the recruitment of HDAC2 on integrin αV gene promoter and prevents the deacetylation of the histone 3. Furthermore, long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) AY927503 (lncRNA AY) strongly promotes integrin αV transcription by interacting with histone 1FX (H1FX), which decreases the occupancy of H3K27Me3 and H1FX on the integrin αV promoter.[92] Nevertheless, the effect of other histone modifications, such as demethylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, on the regulation of integrins expression in HCC needs further investigation.

In addition to transcriptional regulation, the expression of the integrin is also post-transcriptionally controlled by microRNA (miR) or lncRNA in HCC. For example, miR-185 suppresses integrin β5 expression in HCC[93]; overexpression of miR-124 results in robust downregulation of integrin αV[94]; miR-3653 inhibits the growth and metastasis of HCC by suppressing integrin β1[95]; and lncRNA zinc finger protein multitype 2 antisense RNA 1 (ZFPM2-AS1) promotes HCC cells proliferation and invasion through modulating miR-1226/integrin β1 axis.[96] Additional RNA regulatory factors such as RNA-binding proteins and circular RNAs, in integrin messenger RNAs (mRNAs) regulation at the post-transcriptional level, have not been reported in HCC.

Regulation at translational and post-translational levels

In recent years, aberrant mRNA translational regulation has received much attention as a key player in the process of tumor malignancy. However, whether or not the translational regulation of integrins is involved in HCC is poorly studied. Therefore, more studies are needed to further elaborate it.

Post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation and glycosylation are also critical mechanisms to increase proteomic diversity. Liu et al[34] showed that core 1 β1,3-galactosyltransferase (C1GALT1) might modify O-glycans on integrin β1 and regulate integrin β1 activity as well as its downstream signaling. Wang et al[66] illustrated that sulfide binds to integrin αVβ3 in HCC and induces clustering and phosphorylation of integrin αVβ3, triggering “outside-in” signaling. Bergamini et al[54] reported that laminin-5 (Ln-5) stimulates HCC growth via extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation as a consequence of integrin β4 phosphorylation. Besides, Fransvea et al[97] showed that TGF-β1 specifically phosphorylates integrin β1 (threonine 788–789) via Smad-2 and Smad-3, leading to the conformational change of extracellular components and promoting HCC vascular invasion. It is to be noted that the ubiquitin-proteasome system is also important for the homeostasis of the internal environment of many key proteins. Zhao et al[98] identified that the lack of Cullin-Ring E3 ubiquitin ligase complex prevents degradation of integrin β1, which ultimately leads to small-cell lung cancer metastasis. However, the E3 ubiquitin ligase of integrins has not been reported in HCC and needs to be further explored by investigators.

Function of Integrins in HCC

Accumulating evidence has suggested that integrins are involved in almost every step during cancer development, including proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), angiogenesis, adhesion, and invasion. Recent studies have added a range of cancer-related processes that require the participation of integrins in HCC, including drug resistance, radio-resistance, and stemness. We review below the evidence supporting the multiple functions of integrins in HCC pathogenesis.

Adhesion and migration

It is well known that the transition from carcinoma in situ to invasive carcinoma is driven by a series of adhesion changes. By remodeling or dissolving E-cadherin-dependent junctions and integrin-mediated adhesion, clustered cancer cells separate from adjacent normal cells and the underlying basement membrane. Integrins directly phosphorylate the E-cadherin-β-catenin complex via FAK and Src, preventing E-cadherin-dependent junctions and promoting the migration and invasion of cancer cells.[99]

A recent study has indicated that chloride intracellular channel 1 (CLIC1) recruits phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase (PIP5K) 1A and PIP5K1C from the cytoplasm to the leading edge of the plasma membrane, where PIP5Ks generate a phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-rich (PIP2-rich) microdomain to induce integrin-mediated signal for cell-matrix adhesion formation and cytoskeletal extension to promote HCC metastasis.[100] Xu et al[35] showed that IER2 may contribute to the adhesion and motility of ECM in HCC cells by activating the integrin β1/FAK/Src/parsillin signaling pathwy. In addition, integrins can promote HCC adhesion and invasion by interacting with other proteins, such as osteopontin (OPN), vitronectin, and CD151. In detail, Ramaiah and Rittling[68] demonstrated that OPN via RGD and non-RGD motifs interacts with integrin receptors to promote migration and adhesion of HCC cels. The interaction of integrin αVβ3 with vitronectin mediated by lactosylsulfatide (SM3) enhances cell adhesion to vitronectin and promotes intrahepatic metastasis in nude mice.[101] Furthermore, Devbhandari et al[102] showed that the tetrapeptide CD151 is involved in the metastasis of HCC by forming a complex with integrin β1 as molecular partners. However, the mechanisms of how they regulate each other need to be further investigated.

Several oncogenic mutations, such as in the tumor suppresser protein p53 (TP53) or Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS), play a key role in the regulation of cancer metastasis. Mutations within the TP53 gene leading to loss or gain of function (LOF or GOF) of the protein are often observed in many aggressive cancer cells. A recent report found that the role of TP53 and its GOF mutants can promote cancer cell invasion through the reorganization and regulation of integrins and cadherins in cancers, such as colorectal, pancreatic, breast, and ovarian cancers.[103] In addition, TP53 and KRAS co-mutations may promote cholangiocarcinoma metastasis through the integrins/FAK/Src signaling pathway.[104] Furthermore, TP53 mutations and integrin β4 overexpression co-occur in many aggressive malignancies, including basal-like breast cancer, and serous ovarian carcinoma.[105] Although several studies have suggested that mutations in catenin beta 1 and TP53 are the main genetic alterations in HCC,[3,106] their relationship with integrins in HCC metastasis has not been reported yet.

The lung is the most frequent site of metastasis for HCC. Leng et al[29] demonstrated that integrin β4 is overexpressed in HCC tissues and promotes lung metastasis of HCC by conferring anchorage independence through EGFR-dependent FAK/AKT activation. A further study by Li et al[83] showed that integrin β4 promotes HCC growth and lung metastasis in an induced xenograft tumor model by injecting integrin β4-overexpressing cells into nude mice. These data suggested that integrin β4 regulates the growth of distant metastases from HCC and integrin β4 may be a prognostic indicator or therapeutic target for HCC patients.

Notably, the expression of integrin β3 and integrin α9 is downregulated in HCC and negatively correlated with HCC progression. Specifically, integrin α9 could act as an inhibitor of HCC, preventing HCC cell migration and invasion through FAK/Src/Rac1/RhoA signaling pathway.[107] In addition, Wu et al[108] elucidated that downregulation of integrin β3 and its ligand is associated with the aggressive growth of HCC. Therefore, the reconstitution of integrin β3 in HCC may be a potential therapeutic approach to inhibit the aggressive growth of HCC, but the exact mechanism needs to be further investigated.

EMT

Activation of EMT is considered to be a key process in cancer cell metastasis. During this process, epithelial cells acquire the characteristics of mesenchymal cells, resulting in altered morphology and increased mobility and invasiveness of the cells.[109] Integrins are known to regulate the EMT of tumor cells by triggering downstream signaling pathways. Here, we systematically summarize the abnormal signaling events triggered by integrins during EMT in HCC.

FAK is known to be the main signal transduction downstream molecule of integrins and plays a key role in the EMT process.[110] As an intersection of multiple signaling pathways, FAK can trigger EMT through pathways such as MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and Wnt/β-catenin. For example, Zhang et al[67] showed that galectin-1 (Gal-1), by increasing integrin αVβ3 expression, can activate the FAK/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and ultimately induce EMT in HCC. Li et al[75] found that ZKSCAN3 drives HCC metastasis via integrin β4/FAK/AKT mediated EMT in HCC. In addition, integrins can promote EMT in HCC by interacting with other cell surface proteins. For example, Ke et al[60,87] showed that high expression of the CD151/integrin α6β1 complex works together to induce and maintain the EMT process and promote HCC cells metastasis through PI3K/AKT/Snail/phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) feedback loops. Among them, excessive activation of PI3K signaling is the main cause of EMT. Guo et al[32] showed that thrombospondin 4 as an oncogene can interact with integrin β1 to regulate the progression of EMT in HCC through the FAK/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Xia et al[111] elucidated that elevated autocrine EDIL3, a novel EMT regulator, triggers activation of ERK and TGF-β signaling through interacting with integrin αVβ3, inducing EMT and HCC progression. Notably, since hepatocytes are epithelial cells with highly specialized polarity, the disruption and loss of hepatocyte polarity weaken cell adhesion and junctions, inducing EMT and hepatocarcinogenesis. Lu et al[58] showed that the ectopic CD147 polarization distribution on the basolateral membrane promotes E-cadherin ubiquitination and lysosomal degradation through competitive binding integrin α5β1, and reduces partitioning defective three expression and β-catenin nuclear translocation, ultimately leading to hepatocyte depolarization, and complementing the molecular pathway in hepatocarcinogeness.

Furthermore, TGF-β, the most studied growth factor in EMT, can regulate the expression and activation status of certain integrins to synergize with integrin signaling. It has been reported that TGF-β1 significantly enhances integrin α5β1 expression and induces EMT in HCC cells, suggesting the existence of tissue- and cell-specific modality of regulation that needs further investigation.[97] Ln-5 is known to be an ECM molecule widely expressed in human tissues and is involved in the metastasis of many different tumors. Giannelli et al[112] revealed that the coexistence of Ln-5 and TGF-β1 promotes the EMT process, where β-catenin is translocated into the nucleus and cells scatter and become invasive. Notably, the presence of anti-integrin α3-blocking antibodies effectively reverses EMT, suggesting an important role for integrin α3 in Ln-5 and TGF-β1-mediated EMT.[113] Recently, there is growing evidence that higher matrix stiffness acts as an independent initiator to trigger EMT. In HCC, a total of three signaling pathways converging on Snail expression are involved in the stiffness-mediated effect on EMT including integrin-mediated S100A11 membrane translocation, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) phosphorylation, and TGF-β1 autocrine secretion, suggesting an important function of biomechanical signaling in triggering EMT and promoting HCC invasion and metastasis.[114]

Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis plays an important role in tumorigenesis by the formation of new blood vessels that can provide tumor cells with oxygen and nutrients to sustain the growth of solid tumors and promote tumor cells to flow into the circulation through neovascularization, leading to cancer metastasis.[115] Since integrins are mediators of endothelial cell adhesion to ECM components and other cells, endothelium-dependent integrins (especially integrin αVβ3[116]) induce HCC cells to secrete various angiogenic factors by regulating downstream signaling pathways to promote tumor angiogenesis. For example, Cai et al[65] showed that Nogo-B, a tumor angiogenic factor, regulates tumor angiogenesis by binding to integrin αVβ3 and activating FAK. In addition, as mentioned above, EDIL3 has an important role in EMT, while it can also promote HCC angiogenesis and invasion by interacting with integrin αVβ3 to trigger activation of ERK and TGF-β signaling.[111]

Recently, an increasing number of studies have shown that higher matrix stiffness can regulate HCC angiogenesis through integrins. Dong et al[117] suggested that matrix stiffness stimulation signals can be transduced into HCC cells via integrin β1, which activates the PI3K/AKT pathway and upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression, indicating that matrix stiffness can act as a promoter to regulate HCC angiogenesis. Wang et al[88] further showed that increasing matrix stiffness increases the phosphorylation level of AKT and the expression of integrin αVβ5 and nuclear Sp1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). In contrast, inhibition of integrin αVβ5 significantly reversed VEGFR2 expression and AKT phosphorylation levels in HUVEC grown on a high stiffness substrate, suggesting that higher matrix stiffness could act as an initiator to drive angiogenesis in HCC.

Proliferation and stemness

In cancer, cells lose strict control over proliferation in response to extrinsic factors (such as growth factors, cytokines, or exogenous substances) or intrinsic factors (such as activation of oncogenes and transformation of cancer cells). Among them, integrins play a key role in the proliferation of HCC cells in different ways. For example, the exogenous insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 (IGFBP2) activates integrin β1, which promotes the phosphorylation of FAK, ERK, and Elk1, inducing early growth response protein 1 (EGR1)-mediated proliferation of HCC cells.[118] In addition, overexpression of type I collagen in mouse liver increases the expression of integrin β1 and downstream phosphorylated FAK, leading to the proliferation of HCC cells, which could be inhibited by blocking the integrin β1/FAK pathway.[119] Several recent studies have found that the effect of integrins on the cell cycle progression is also important. For example, activation of the integrin β1/paxillin/14-3-3 protein zeta/AKT pathway accelerates cell cycle progression and promotes HCC cell proliferatin.[31] Liu et al[85] showed that type IV collagen (COL4A1/2) can directly bind to integrin α2β1 to activate signal transduction with PI3K/AKT as the main pathway, thereby accelerating the cell cycle and promoting tumorigenesis.

Notably, integrin signaling has been shown to drive the stemness of tumor cells, a subset of tumor cells with stem cell-like properties of high proliferation, low differentiation, and high self-renewal capacity in many tumors. Stemness has become an important attribute of malignancy due to its close association with poor prognosis in various cancers.[120] Periostin (POSTN) has been reported to be a key extracellular regulator of several liver diseases, and it is also involved in the progression of HCC.[70] Zhang et al[74] showed that POSTN can regulate the stemness of HCC cells by activating the integrin β1/AKT/glycogen synthase kinase 3/β-catenin/transcription factor 4 (TCF4)/Nanog signaling pathway, suggesting that metformin is a potential drug to reverse this process. You et al[121] showed that integrin β1 may deliver higher matrix stiffness signals to HCC cells and activate the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, promoting high matrix stiffness-mediated stemness characteristics in HCC. Finally, Cao et al[44] found that OPN binds to integrin αVβ3 and activates the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), leading to upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and its downstream gene BMI1 expression, a recognized transcriptional repressor with the ability to maintain tissue-specific stem cell self-renewal and proliferation, thus this pathway may promote the maintenance of the HCC stem cell-like phenotype.

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy resistance

Chemotherapeutic drugs kill tumor cells by inducing apoptosis, but the development of drug resistance limits the efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g., cisplatin, paclitaxel, etc.). Recently, integrin β1-mediated cell adhesion to the ECM inhibits apoptosis of tumor cells induced by various stimuli, suggesting that integrin β1-mediated signaling may protect cancer cells from chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis, especially in HCC.[122,123] In a previous study, Liu et al[46] found that tumor chemo-resistance is associated with OPN and autophagy, and then they further showed that secreted OPN can promote HCC cells’ autophagy by both binding to its receptor integrin αVβ3 and stabilizing forkhead box protein O transcription factors 3a (FoxO3a) protein, which induces autophagy gene expression and further promotes HCC chemoresistance. Zhang et al[45] showed that overexpression of integrin β1 confers the anti-apoptotic ability to HCC cells through a MAPK-dependent pathway and may be associated with chemotherapy resistane. Furthermore, Tian et al[124] found that integrin β1 mediates multicellular resistance in HCC spheroids via the FAK/AKT pathway. Sorafenib is known to be the only systemic therapy approved to date for the treatment of patients with advanced HCC. However, resistance to sorafenib is common and is partly related to the integrin signaling pathway. Gal-1 induces sorafenib resistance by increasing integrin αVβ3 expression, leading to AKT activation.[67] Furthermore, Azzariti et al[53] discovered that simultaneous expression of integrins α3β1 and α6β4 in the presence of hepatic stellate cell-conditioned medium (HSC-CM) or laminin-332 (Ln-332) inhibits the efficacy of sorafenib against HCC cells. However, inhibition of integrin α3 but not integrin α6 subunits by blocking antibodies or small interfering RNAs abrogates the protective effect induced by Ln-332 and HSC-CM, suggesting that the mechanism of sorafenib resistance is dependent on the integrin α3β1/Ln-332 axis.

Onco-radiotherapy, a local treatment using radiation to treat tumors, has been clinically used to improve the survival of patients with advanced HCC. Although the response of HCC to stereotactic body radiation therapy has been described in the past few years, the presence of radio-resistant cells in HCC remains an important reason for the failure of local radiotherapy.[122] Activation of the integrins and their downstream FAK/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is associated with decreased radiation responsiveness in various malignancies including HCC.[125] Jiang et al[37] found that overexpression of integrin β1 significantly increases the resistance of HCC cells to radiation and cisplatin treatment, indicating the importance of integrin β1 in HCC to chemo/radiation therapy. In addition, Wu et al[38] showed that HAb18G/CD147, a heavily glycosylated protein, promotes radio-resistance in HCC by interacting with integrin β1. Inhibition of HAb18G/CD147 interactions with integrin β1 may provide a potential new approach for HCC treatment.

Integrins with Other Cells in the TME of HCC

TME refers to the surrounding microenvironment in which tumor cells exist, consisting of blood vessels, immune cells, fibroblasts, stem cells, ECM, and various cytokines and chemokines.[126] TME has a promotional role in tumor development, and integrins are considered to affect multiple components in TME, such as the effect on angiogenesis described above. In this section, we summarize the roles of cancer cell integrins in regulating the recruitment and functions of other cell types in HCC.

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)

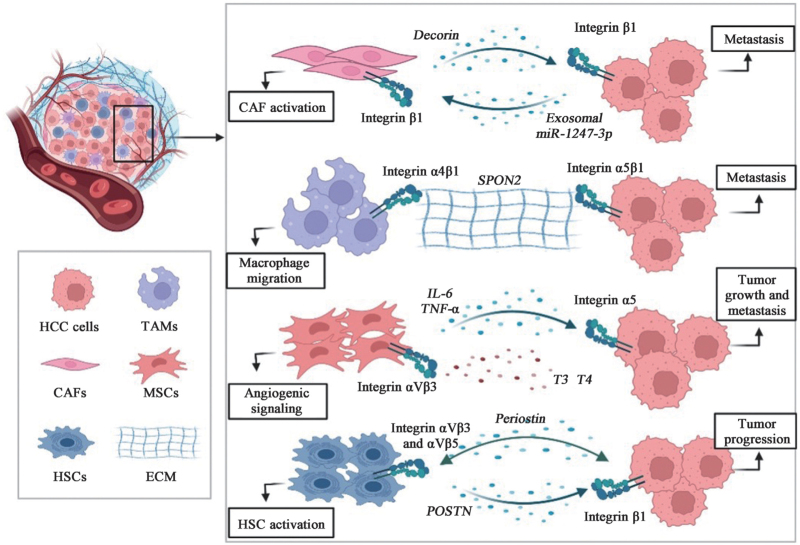

CAFs are major tissue components of the TME and can promote cancer progression through interactions with tumor cells. Numerous studies support the critical role of CAFs in promoting HCC progression through integrins expression [Figure 2]. It is well known that portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT) is a common condition in intrahepatic metastases of HCC. Zheng et al[127] demonstrated that decorin secreted by CAFs is progressively downregulated from normal to tumor tissues, and more so in PVTT tissues. Mechanistically, decorin downregulates integrin β1 and inhibits HCC cell invasion and migration, suggesting that decorin targeting in CAFs is not only a promising strategy but also provides insight into the clinical treatment of patients with PVTT. In addition, Fang et al[128] found that high-metastatic HCC cells secrete exosomal miR-1247-3p, which directly targets beta-1,4-galactosyltransferase 3, leading to activation of integrin β1/NF-κB signaling in CAFs. Activated CAFs further promote HCC progression by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8. These results demonstrate that intercellular crosstalk between HCC cells and CAFs is mediated by tumor-derived exosomes.

Figure 2.

Integrins with other cells in the HCC-TME. TME typically contains multiple cell types, including tumor cells, stromal cells, immune cells, endothelial cells, and non-pathogenic cells. We list the four cell types that have been reported in HCC-TME with a lineage map of HCC cells that promote cancer progression through integrin-related mechanisms. For more information, please refer to the text. CAF: Cancer-associated fibroblast; ECM: Extracellular matrix; HCC: Human hepatocellular carcinoma; HSCs: Hepatic stellate cells; IL-6: Interleukin 6; MSCs: Mesenchymal stem cells; POSTN: Periostin; SPON2: Spondin 2; T3: Triiodothyronine; T4: Thyroxine; TAMs: Tumor-associated macrophages; TME: Tumor microenvironment; TNF-α: Tunor necrosis factor-α.

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)

TAMs are the most abundant immune cells in the TME of HCC. Studies have shown that M1-type macrophages mainly play a role in tumor suppression, promotion of inflammation, and immune activity, while M2-type macrophages play a role in tissue repair, immune escape, and promotion of tumor development. Integrins play a bi-directional regulatory role as key mediators in cancer cells and TAMs [Figure 2]. Zhang et al[86] showed that matricellular protein Spondin 2 (SPON2)-integrin α4β1 signaling increases F-actin reorganization by activating RhoA and Rac1 and promotes M1-like macrophage recruitment. Interestingly, SPON2-integrin α5β1 signaling inactivates RhoA and prevents F-actin assembly, thereby inhibiting HCC cells migration, suggesting that SPON2 acts as an inhibitor of HCC using different signaling events in TE. Furthermore, Wu et al[72] found that integrin αMβ2 (CD11b/CD18) in M2 macrophage-derived exosomes (M2 exos) significantly promotes HCC cells metastasis by activating the matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9) signaling pathway, suggesting that exosome-mediated transfer of functional CD11b/CD18 protein from TAMs to HCC cells may have the potential to enhance HCC cells migration.

In the immune system, integrins can regulate various functions of lymphocytes including T lymphocyte activation, migration, and extravasation into tissues. When T cells are presented with cognate antigens by the antigen presenting cells (APCs), signals from the T cell receptor (TCR) initiate the actin cytoskeleton rearrangement program, leading to T cell polarization and activation. Integrin activation further assists the TCR signaling for additional modifications of actin-associated proteins that play a key role in altering plasma membrane rigidity.[129] In addition, it is known that “inside-out” signaling regulates the affinity of integrins for their ligands and/or the extent to which integrins diffuse and cluster on the cell surface. After stimulation, lymphocytes acquire the ability to adhere to endothelial cells, APCs, or ECMs through regulatory interactions of integrins.[130] For example, the “inside-out” signaling triggered by chemokines increases the affinity of lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA1) and integrin α4, which leads to their strong attachment to ligands. Subsequently, lymphocytes migrate through endothelial cells to lymphoid or inflammatory tissues.[131] While there are no reports on the involvement of integrins in regulating lymphocytes in HCC so far, it is speculated that the HCC integrins play identical roles as that in other tumors. Nevertheless, future studies are needed for further validation.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)

MSCs are self-renewing pluripotent stem cells that modulate and participate in anti-tumor immune responses. MSCs are potential anti-cancer drug carriers due to their excellent tumor targeting. However, the study between MSCs and HCC is highly controversial, with integrins playing a key role in promoting cancer progression [Figure 2]. For example, Chen et al[132] performed RNA sequencing to elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which human MSCs (hMSCs) promote HCC progression and metastasis, and found that integrin α5 in HCC is significantly upregulated by hMSCs and promotes the migration and invasive ability in HCC-hMSCs. Furthermore, as new thyroid hormone-dependent targets, MSCs are important contributors to the tumor fibrovascular network. Schmohl et al[133] initially found that the thyroid hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) increase the migration and invasion of MCS toward HCC cells and promote the expression of genes related to mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) differentiation, all of these effects are dependent on the integrin-specific inhibitor tetrac and therefore mediated by integrin αVβ3. Later, they further found that in HCC cells conditioned medium, T3 and T4 can increase angiogenesis-related factor expression and promote endothelial cell tube formation in MSCs, while tetrac can reverse all these effects, suggesting that thyroid hormones affect angiogenic signaling in MSCs via integrin αVβ3.[134] These studies significantly improve our understanding of the antitumor activity of tetrac.

HSCs

HSCs are liver-specific mesenchymal cells and the main source of ECM production and deposition. The dormant HSC is an important component of the HCC-TME and a key regulator of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, which contributes to the tumorigenicity and invasiveness of HCC. Recently, it was found that integrins are surface receptors on the HSC that receive signals from TME and are essential for liver fibrosis. Xiao et al[70] found that POSTN promotes HSC activation via an autocrine POSTN/integrin αVβ3 and αVβ5/FAK/STAT3/POSTN circuit pathway and enhances the proliferation of HCC cells via the ERK pathway, promoting the development of HCC. Zhang et al[74] found that when HCC cells are exposed to sublethal heat treatment, activated HSC can release POSTN, which promotes stem cell-like phenotypes of residual HCC cells after incomplete thermal ablation by activating the integrin β1/AKT/glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK-3β)/β-catenin/TCF4/Nanog signaling pathwy. Later, the team further found that POSTN can also activate p52Shc and ERK1/2 in HCC residual cells via integrin β1, promoting tumor progression in heat-treated residual HCC cells.[48] In addition, Yan et al[71] found that upregulated fibrinogen may bind to integrin αVβ5 on stellate cells and activate stellate cells after KRASV12 induction in tumorigenic hepatocytes. Treatment with the integrin αVβ5 antagonist, cilengitide, significantly blocks HSC activation and function, while inhibiting the proliferation of oncogenic hepatocytes and the progression of liver fibross.

Integrins and HBV-related HCC

HBV accounts for >60% of HCC cases and is the main etiological risk for HCC development, while high expression of integrins, a gene-specific marker for HBV-driven HCC, plays an important role in HCC development. Integrin α6 is commonly overexpressed in HBV-driven HCC patients and significantly correlated with HBV and is considered a predictive marker for tumor recurrence and aggressiveness in HBV-driven HCC.[135] Shang et al[136] found that the expression of integrin α5 and β5 is higher in HBV-related HCC tissues and predicts poorer prognosis for patients with HBV-related HCC, which is in contrast to the expression of integrin α2B. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are reported to be one of the most common forms of genetic variation in the human genome, and various SNPs may increase susceptibility to various common diseases. Therefore, in this study, they also investigated 18 SNPs in integrin family genes and found that the AG/GG genotype at rs988574 in integrin α1 predicts a better prognosis than AA genotype carriers.[136] In addition, Lee et al[137] investigated that SNPs of integrin αV are associated with HBV-infected HCC in the Korean population and that SNPs of integrin αV may be genetic factors that increase susceptibility to HBV-infected HCC in Koreans. Taken together, the expression of these genes is a potential independent prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for patients with HBV-associated HCC and may contribute to the diagnosis of HBV-associated HCC.

The regulatory protein encoded by HBV, hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx), is known for its pleiotropic role in tumorigenesis and is essential for HBV replication and cellular transformation.[137] HBx positively regulates integrins and promotes HCC cell proliferation in HBV-related HCC, but exhibits negative regulation of integrins with many different functions in other cells. For example, in HBV-related glomerulonephritis (HBV-GN), He et al[138] found that HBx-mediated downregulation of integrin α3β1 expression was sufficient to reduce podocyte adhesion and increase apoptosis, which leads to a decrease in the number of podocytes. HBx-induced apoptosis of podocytes may contribute to HBV-GN. In addition, Lara-Pezzi et al[139] provided evidence that HBx may alter the adhesion properties of cells to the ECM by interfering with the expression of integrin α5 in HBx-bearing Chang liver cells. Furthermore, they found that activated integrin β1 is redistributed to the tip of the pseudopod of cells carrying HBx and demonstrated that HBx induces Chang liver cell motility in an integrin β1-dependent manner. However, in HBV-related HCC, Zhang et al[140] elucidated that HBx expression inhibits transcription factor EB (TFEB), leading to impaired autophagy/lysosome biogenesis and flux, which leads to integrin β1 accumulation and promotes HCC cell proliferation. Functional studies of integrins in HBV-related HCC are currently scarce, and further research is needed in the future.

Targeting Integrins as HCC Therapeutics

Since the discovery that integrins promote cancer progression, integrins have been considered potential therapeutic targets. A range of drugs, including antibodies, synthetic peptides, and mimetic peptides, have been used to target integrins in cancer.

Besides, various promising preclinical studies have been identified. For example, Ke et al[60] successfully prepared a mouse monoclonal antibody tetraspanin CD151 (immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1], called CD151 mAb 9B) against the CD151-integrin α6β1 binding site in the extracellular structural domain of CD151. Both in vivo and in vitro experiments showed that CD151 mAb 9B not only displays good reactivity to the CD151 antigen but also inhibits the growth and metastasis of HCC. Synstatin (SSTN92-119) is a peptide that mimics syndecan-1 (CD-138) at its interaction site and it can interfere with the interaction between CD-138 and integrin αVβ3, downregulating integrin αVβ3 receptors and thus inhibiting HCC angiogenesis and proliferation.[141] Raj-tspin is a novel recombinant peptide from Japanese ginseng that contains an RGD motif and six cysteine residues. Yu et al[49] found that Raj-tspin inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells by inhibiting the integrin β1/FAK/AKT signaling pathway and exhibits low toxicity at effective doses. T7 peptide is considered an anti-angiogenic peptide. Under normoxic and hypoxic conditions, T7 peptide inhibits endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis through the integrin α3β1 and αVβ3 pathways and promotes apoptosis of HCC endothelial cells.[142] Capasso et al[143] recently reported a cyclic peptide RGDechi15D that specifically binds to integrin αVβ5 and does not cross-react with integrin αVβ3. Here, they demonstrated that RGDechi15D can interfere with the PI3K pathway, inhibit HCC cell adhesion, proliferation, and invasion, and reduce HCC endothelial cell angiogenesis.

In addition, several natural product compounds have been reported to exhibit promising effects in modulating integrin signaling and are undergoing preclinical application studies. Garcinia cambogia acid (GA) is a natural compound derived from Garcinia cambogia with anticancer activity. Park et al[144] showed that GA inhibits actin rearrangement associated with cytoskeleton and migration and reduces the expression of MMP2, MMP9, and NF-κB through downregulating the expression of integrin β1/Rho family GTPase signaling pathway. These results suggest that GA may be a novel anti-metastatic agent worthy of further exploration. Cordycepin, also known as 3-deoxyadenosine, is an analog of adenosine extracted from the traditional Chinese medicine “Cordyceps sinensis.” Yao et al[145] found that the expression levels of integrin α3, α6, and β1, and phosphorylated FAK are significantly reduced after the treatment of HCC cells with cordycepin. Meanwhile, the expression of E-cadherin is significantly increased and suppresses EMT, which suggests that cordycepin may be a potential therapeutic or supplementary agent for preventing HCC tumor progression. Fucoidan is a fucose-enriched sulfated polysaccharide from brown algae. In recent years, this polysaccharide has been found to have various biological effects, including anti-tumor effects such as anti-proliferation, activation of apoptosis, and anti-angiogenesis of tumor cells. Pan et al[146] found that fucoidan could exert anti-metastatic effects by targeting integrin αVβ3 and mediating the integrin αVβ3/Src/E2F transcription factor 1 signaling pathway in various HCC cells.

Clinical Trials in Integrin Targeting

Because of the variable expression of integrins in tumors, the redundancy of integrin function, and the possible different roles of integrins in different disease stages, integrin-targeted therapy has so far failed to achieve clinical efficacy.[147] Although they are not yet fully established, many of them are being developed in clinical trials as anticancer drugs.[148,149] Herein, we summarize some recent encouraging clinical trials and preclinical findings of integrin-related drugs in the treatment of HCC [Table 4].

Table 4.

Applications of preclinical and clinical integrin antagonists in HCC.

| Drug name | Type | Target and mechanism | Clinical trial | References |

| MINT1526A (RG-7594) | Monoclonal antibody | Inhibit integrin α5β1 binding to FN1 | Phase I | [150] |

| Tetraspanin CD151 | Monoclonal antibody | Against the CD151-integrin α6β1 binding site | Preclinical | [60] |

| Synstatin (SSTN92-119) | Peptide | Interfere with the interaction between CD-138 and integrin αVβ3 | Preclinical | [141] |

| Raj-tspin | Peptide | Inhibit the integrin β1/FAK/AKT signaling pathway | Preclinical | [49] |

| T7 peptide | Peptide | Inhibit the integrin α3β1 and αVβ3 pathways | Preclinical | [142] |

| RGDechi15D | Peptide | Bind to integrin αVβ5 and interfere with the PI3K pathway | Preclinical | [143] |

| GA | Natural compound | Downregulate the expression of integrin β1/Rho family GTPase signaling pathway | Preclinical | [144] |

| Cordycepin | Natural compound | Suppress integrin α3, α6, and β1/FAK signaling pathway | Preclinical | [145] |

| Fucoidan | Natural polysaccharide | Suppress integrin αVβ3/Src/E2F1 signaling pathway | Preclinical | [146] |

AKT: Protein kinase B; E2F1: E2F transcription factor 1; FAK: Focal adhesion kinase; FN1: Fibronectin 1; GA: Garcinia cambogia acid; HCC: Human hepatocellular carcinoma; PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

In a phase I trial, Colin et al[150] investigated the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the integrin α5β1-targeting monoclonal antibody MINT1526A (RG-7594) in patients with various solid tumors, including HCC. MINT1526A can inhibit integrin α5β1 binding to fibronectin 1 (FN1), as well as integrin α5β2-mediated endothelial cell adhesion, migration, and germination in FN1-containing matrices (NCT01139723). Based on trial data, dual anti-angiogenic therapy combining with integrin α5β1 and VEGF inhibition is well tolerated without significant exacerbation of bevacizumab-related toxicities. However, comparing to the positive control bevacizumab monotherapy, MINT1526A did not achieve a significant clinical activity as measured by conventional response evaluation criteria in solid tumors response in this phase I study. Therefore, more emphasis should be placed on elucidating the relationship between baseline tumor expression or vascular biology signature of FN1 and anti-integrin α5β1 response before developing MINT1526A or similar agents in phase II study. In addition, several preclinical trials have been ongoing in evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of integrin targeting in antitumor therapy.[49,142–146] As integrins are expressed in various normal cells, their targeting should be critically evaluated for both acute and chronic toxicities.

Although there are some clinical trials in different cancers, the overall outcomes of targeting integrins were somewhat disappointing. Possible reasons are the following. First, integrins are widely expressed in vivo, and most cells can express more than one integrin on their surface, which plays a key role in various biological functions. Therefore, the development of integrin-targeting drugs with high specificity to tumors is a major challenge. Second, many integrins show overlap in their ligand binding spectrum. For example, ECM proteins such as fibronectin, laminin, and collagen are recognized by more than one integrin. Hence, the effect of blocking one integrin may be compensated for by another integrin binding the same ligand. Nevertheless, extensive future efforts are needed for the development of integrin targeting in anticancer therapy.

Conclusions and Perspectives

In summary, we comprehensively discuss the effects of integrins on HCC progression, including the aberrant expression, activation, and signaling pathways, as well as the multiple functions of integrins in HCC produced in vivo, which are involved in almost every step of HCC development. The diversity of integrins and their roles in HCC demonstrate the great potential of this superfamily as drug targets. Therefore, to improve the efficacy of integrin-targeted therapy and to fully understand the role of integrins in the development of HCC, we prospectively propose the following points for further study: (1) Knowledge derived from in vitro and in vivo experiments remains to be translated into clinical situations. In animal models, several RGD peptides and monoclonal antibodies have shown promising results in inhibiting HCC metastasis, but whether these results can be reproduced in humans remains to be tested; (2) integrin-related mechanisms linking the immune and metabolic systems in HCC remain a gaping area and require more research attention; (3) it is warranted to explore the stage-specific expression patterns of integrins, in particular, their role in differentiating early low-risk from late-stage high-risk metastatic HCC; (4) it is important to elucidate the mechanism of integrins in promoting HCC metastasis in multiple metastatic steps, including EMT/invasion, perfusion, circulation, extravasation, and colonization, which is a promising avenue of research. We believe that continued efforts to better understand the role of integrins in hepatocarcinogenesis will lead to the development of more innovative targeted approaches and a renaissance in the field.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Gao Q, Sun Z, Fang D. Integrins in human hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis and therapy. Chin Med J 2023;136:253–268. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002459

References

- 1.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019; 380:1450–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer 2019; 144:1941–1953. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakraborty E, Sarkar D. Emerging therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Cancers 2022; 14:2798.doi: 10.3390/cancers14112798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han TS, Ban HS, Hur K, Cho HS. The epigenetic regulation of HCC metastasis. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19:3978.doi: 10.3390/ijms19123978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang W, Chen Z, Zhang W, Cheng Y, Zhang B, Wu F, et al. The mechanisms of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: theoretical basis and therapeutic aspects. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020; 5:87.doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0187-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 2002; 110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell ID, Humphries MJ. Integrin structure, activation, and interactions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011; 3:a004994.doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takada Y, Ye X, Simon S. The integrins. Genome Biol 2007; 8:215.doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humphries JD, Byron A, Humphries MJ. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci 2006; 119:3901–3903. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaFoya B, Munroe JA, Miyamoto A, Detweiler MA, Crow JJ, Gazdik T, et al. Beyond the matrix: the many non-ECM ligands for integrins. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19:449.doi: 10.3390/ijms19020449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carman CV, Springer TA. Integrin avidity regulation: are changes in affinity and conformation underemphasized. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2003; 15:547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo BH, Carman CV, Springer TA. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu Rev Immunol 2007; 25:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye F, Kim C, Ginsberg MH. Reconstruction of integrin activation. Blood 2012; 119:26–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-292128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnaout MA, Mahalingam B, Xiong JP. Integrin structure, allostery, and bidirectional signaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2005; 21:381–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.090704.151217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim M, Carman CV, Springer TA. Bidirectional transmembrane signaling by cytoplasmic domain separation in integrins. Science 2003; 301:1720–1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1084174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michael M, Parsons M. New perspectives on integrin-dependent adhesions. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2020; 63:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2019.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wegener KL, Campbell ID. Transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains in integrin activation and protein-protein interactions (Review). Mol Membr Biol 2008; 25:376–387. doi: 10.1080/09687680802269886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ginsberg MH, Partridge A, Shattil SJ. Integrin regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2005; 17:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science 1999; 285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shattil SJ, Kim C, Ginsberg MH. The final steps of integrin activation: the end game. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010; 11:288–300. doi: 10.1038/nrm2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alanko J, Mai A, Jacquemet G, Schauer K, Kaukonen R, Saari M, et al. Integrin endosomal signalling suppresses anoikis. Nat Cell Biol 2015; 17:1412–1421. doi: 10.1038/ncb3250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horton ER, Humphries JD, Stutchbury B, Jacquemet G, Ballestrem C, Barry ST, et al. Modulation of FAK and Src adhesion signaling occurs independently of adhesion complex composition. J Cell Biol 2016; 212:349–364. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201508080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamidi H, Ivaska J. Every step of the way: integrins in cancer progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 2018; 18:533–548. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0038-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yee KL, Weaver VM, Hammer DA. Integrin-mediated signalling through the MAP-kinase pathway. IET Syst Biol 2008; 2:8–15. doi: 10.1049/iet-syb:20060058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mainiero F, Murgia C, Wary KK, Curatola AM, Pepe A, Blumemberg M, et al. The coupling of alpha6beta4 integrin to Ras-MAP kinase pathways mediated by Shc controls keratinocyte proliferation. EMBO J 1997; 16:2365–2375. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun F, Wang J, Sun Q, Li F, Gao H, Xu L, et al. Interleukin-8 promotes integrin β3 upregulation and cell invasion through PI3K/Akt pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2019; 38:449.doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1455-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw LM, Rabinovitz I, Wang HH, Toker A, Mercurio AM. Activation of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase by the alpha6beta4 integrin promotes carcinoma invasion. Cell 1997; 91:949–960. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raftopoulou M, Hall A. Cell migration: Rho GTPases lead the way. Dev Biol 2004; 265:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leng C, Zhang ZG, Chen WX, Luo HP, Song J, Dong W, et al. An integrin beta4-EGFR unit promotes hepatocellular carcinoma lung metastases by enhancing anchorage independence through activation of FAK-AKT pathway. Cancer Lett 2016; 376:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu Y, Feng MX, Yu J, Ma MZ, Liu XJ, Li J, et al. DNA methylation-mediated silencing of matricellular protein dermatopontin promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by α3β1 integrin-Rho GTPase signaling. Oncotarget 2014; 5:6701–6715. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie J, Guo T, Zhong Z, Wang N, Liang Y, Zeng W, et al. ITGB1 drives hepatocellular carcinoma progression by modulating cell cycle process through PXN/YWHAZ/AKT pathways. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021; 9:711149.doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.711149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo D, Zhang D, Ren M, Lu G, Zhang X, He S, et al. THBS4 promotes HCC progression by regulating ITGB1 via FAK/PI3K/AKT pathway. FASEB J 2020; 34:10668–10681. doi: 10.1096/fj.202000043R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cui J, Huang W, Wu B, Jin J, Jing L, Shi WP, et al. N-glycosylation by N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V enhances the interaction of CD147/basigin with integrin β1 and promotes HCC metastasis. J Pathol 2018; 245:41–52. doi: 10.1002/path.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu CH, Hu RH, Huang MJ, Lai IR, Chen CH, Lai HS, et al. C1GALT1 promotes invasive phenotypes of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by modulating integrin β1 glycosylation and activity. PLoS One 2014; 9:e94995.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu Z, Zhu L, Wu W, Liao Y, Zhang W, Deng Z, et al. Immediate early response protein 2 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma cell adhesion and motility via integrin β1-mediated signaling pathway. Oncol Rep 2017; 37:259–272. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winkler J, Roessler S, Sticht C, DiGuilio AL, Drucker E, Holzer K, et al. Cellular apoptosis susceptibility (CAS) is linked to integrin β1 and required for tumor cell migration and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Oncotarget 2016; 7:22883–22892. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang X, Wang J, Zhang K, Tang S, Ren C, Chen Y. The role of CD29-ILK-Akt signaling-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition of liver epithelial cells and chemoresistance and radioresistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Med Oncol 2015; 32:141.doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0595-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu J, Li Y, Dang YZ, Gao HX, Jiang JL, Chen ZN. HAb18G/CD147 promotes radioresistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells: a potential role for integrin β1 signaling. Mol Cancer Ther 2015; 14:553–563. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park JY, Pillinger MH, Abramson SB. Prostaglandin E2 synthesis and secretion: the role of PGE2 synthases. Clin Immunol 2006; 119:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma WL, Jeng LB, Lai HC, Liao PY, Chang C. Androgen receptor enhances cell adhesion and decreases cell migration via modulating β1-integrin-AKT signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett 2014; 351:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, Wu J, Song F, Tang J, Wang SJ, Yu XL, et al. Extracellular membrane-proximal domain of HAb18G/CD147 binds to metal ion-dependent adhesion site (MIDAS) motif of integrin β1 to modulate malignant properties of hepatoma cells. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:4759–4772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, Ge C, Zhao F, Yan M, Hu C, Jia D, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha-activated angiopoietin-like protein 4 contributes to tumor metastasis via vascular cell adhesion molecule-1/integrin β1 signaling in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2011; 54:910–919. doi: 10.1002/hep.24479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xue YH, Zhang XF, Dong QZ, Sun J, Dai C, Zhou HJ, et al. Thrombin is a therapeutic target for metastatic osteopontin-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2010; 52:2012–2022. doi: 10.1002/hep.23942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao L, Fan X, Jing W, Liang Y, Chen R, Liu Y, et al. Osteopontin promotes a cancer stem cell-like phenotype in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via an integrin-NF-κB-HIF-1α pathway. Oncotarget 2015; 6:6627–6640. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang H, Ozaki I, Mizuta T, Matsuhashi S, Yoshimura T, Hisatomi A, et al. Beta 1-integrin protects hepatoma cells from chemotherapy induced apoptosis via a mitogen-activated protein kinase dependent pathway. Cancer 2002; 95:896–906. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu G, Fan X, Tang M, Chen R, Wang H, Jia R, et al. Osteopontin induces autophagy to promote chemo-resistance in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett 2016; 383:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Y, Ren Z, Wang Y, Dang YZ, Meng BX, Wang GD, et al. ADAM17 promotes cell migration and invasion through the integrin β1 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp Cell Res 2018; 370:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang R, Lin XH, Ma M, Chen J, Chen J, Gao DM, et al. Periostin involved in the activated hepatic stellate cells-induced progression of residual hepatocellular carcinoma after sublethal heat treatment: its role and potential for therapeutic inhibition. J Transl Med 2018; 16:302.doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1676-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu P, Wu R, Zhou Z, Zhang X, Wang R, Wang X, et al. rAj-Tspin, a novel recombinant peptide from Apostichopus japonicus, suppresses the proliferation, migration, and invasion of BEL-7402 cells via a mechanism associated with the ITGB1-FAK-AKT pathway. Invest New Drugs 2021; 39:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s10637-020-01008-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guijarro LG, Sanmartin-Salinas P, Pérez-Cuevas E, Toledo-Lobo MV, Monserrat J, Zoullas S, et al. Possible role of IRS-4 in the origin of multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers 2021; 13:2560.doi: 10.3390/cancers13112560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu J, Zhang C, Yu Q, Yu H, Zhang B. ADAR1 p110 enhances adhesion of tumor cells to extracellular matrix in hepatocellular carcinoma via up-regulating ITGA2 expression. Med Sci Monit 2019; 25:1469–1479. doi: 10.12659/MSM.911944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong KF, Liu AM, Hong W, Xu Z, Luk JM. Integrin α2β1 inhibits MST1 kinase phosphorylation and activates Yes-associated protein oncogenic signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016; 7:77683–77695. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azzariti A, Mancarella S, Porcelli L, Quatrale AE, Caligiuri A, Lupo L, et al. Hepatic stellate cells induce hepatocellular carcinoma cell resistance to sorafenib through the laminin-332/α3 integrin axis recovery of focal adhesion kinase ubiquitination. Hepatology 2016; 64:2103–2117. doi: 10.1002/hep.28835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bergamini C, Sgarra C, Trerotoli P, Lupo L, Azzariti A, Antonaci S, et al. Laminin-5 stimulates hepatocellular carcinoma growth through a different function of alpha6beta4 and alpha3beta1 integrins. Hepatology 2007; 46:1801–1809. doi: 10.1002/hep.21936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Du J, Zhao Z, Zhao H, Liu D, Liu H, Chen J, et al. Sec62 promotes early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma through activating integrinα/CAV1 signalling. Oncogenesis 2019; 8:74.doi: 10.1038/s41389-019-0183-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dong XF, Zhong JT, Liu TQ, Chen YY, Tang YT, Yang JR. Angiopoietin-2 regulates vessels encapsulated by tumor clusters positive hepatocellular carcinoma nest-type metastasis via integrin α5β1 (in Chinese). Natl Med J China 2021; 101:654–660. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20200605-01780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou YQ, Lv XP, Li S, Bai B, Zhan LL. Synergy of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor isomer (D1D2) and integrin α5β1 causes malignant transformation of hepatic cells and the occurrence of liver cancer. Mol Med Rep 2014; 10:2568–2574. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu M, Wu J, Hao ZW, Shang YK, Xu J, Nan G, et al. Basolateral CD147 induces hepatocyte polarity loss by E-cadherin ubiquitination and degradation in hepatocellular carcinoma progress. Hepatology 2018; 68:317–332. doi: 10.1002/hep.29798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carloni V, Mazzocca A, Pantaleo P, Cordella C, Laffi G, Gentilini P. The integrin, alpha6beta1, is necessary for the matrix-dependent activation of FAK and MAP kinase and the migration of human hepatocarcinoma cells. Hepatology 2001; 34:42–49. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ke AW, Zhang PF, Shen YH, Gao PT, Dong ZR, Zhang C, et al. Generation and characterization of a tetraspanin CD151/integrin α6β1-binding domain competitively binding monoclonal antibody for inhibition of tumor progression in HCC. Oncotarget 2016; 7:6314–6322. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang K, Dong C, Yin Z, Li R, Mao J, Wang C, et al. Exosome-derived ENO1 regulates integrin α6β4 expression and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth and metastasis. Cell Death Dis 2020; 11:972.doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-03179-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ge JC, Wang YX, Chen ZB, Chen DF. Integrin alpha 7 correlates with poor clinical outcomes, and it regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis and stemness via PTK2-PI3K-Akt signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Signal 2020; 66:109465.doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.109465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weiler S, Lutz T, Bissinger M, Sticht C, Knaub M, Gretz N, et al. TAZ target gene ITGAV regulates invasion and feeds back positively on YAP and TAZ in liver cancer cells. Cancer Lett 2020; 473:164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cai QQ, Dong YW, Qi B, Shao XT, Wang R, Chen ZY, et al. BRD1-mediated acetylation promotes integrin αV gene expression via interaction with sulfatide. Mol Cancer Res 2018; 16:610–622. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cai H, Saiyin H, Liu X, Han D, Ji G, Qin B, et al. Nogo-B promotes tumor angiogenesis and provides a potential therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Oncol 2018; 12:2042–2054. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang R, Qi B, Dong YW, Cai QQ, Deng NH, Chen Q, et al. Sulfatide interacts with and activates integrin αVβ3 in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncotarget 2016; 7:36563–36576. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]