Abstract

Background

Previously, several studies investigated the effect of cladribine among patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) as a treatment option. Due to the contradictory results of previous studies regarding the efficacy and safety of cladribine in the MS population, we aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis by including clinical trials and observational studies in terms of having more confirmative results to make a general decision.

Methods

The three databases including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were comprehensively searched in May 2022. We included the studies that investigated the efficacy and safety of cladribine in patients with MS. Eligible studies have to provide sufficient details on MS diagnosis and appropriate follow-up duration. We investigated the efficacy of cladribine with several outcomes including Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) change, progression-free survival (PFS), relapse-free survival (RFS), and MRI-free activity survival (MFAS).

Results

After two-step reviewing, 23 studies were included in our qualitative and quantitative synthesis. The pooled SMD for EDSS before and after treatment was − 0.54 (95%CI: − 1.46, 0.39). Our analysis showed that the PFS after cladribine use is 79% (95%CI 71%, 86%). Also, 58% of patients with MS who received cladribine remained relapse-free (95%CI 31%, 83%). Furthermore, the MFAS after treatment was 60% (95%CI 36%, 81%). Our analysis showed that infection is the most common adverse event after cladribine treatment with a pooled prevalence of 10% (95%CI 4%, 18%). Moreover, the pooled prevalence of infusion-related adverse events was 9% (95%CI 4%, 15%). Also, the malignancies after cladribine were present in 0.4% of patients (95%CI 0.25%, 0.75%).

Conclusion

Our results showed acceptable safety and efficacy for cladribine for the treatment of MS except in terms of reducing EDSS. Combination of our findings with the results of previous studies which compared cladribine to other disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), cladribine seems to be a safe and effective drug in achieving better treatment for relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10072-023-06794-w.

Keywords: Cladribine, Multiple sclerosis, Safety, Efficacy, Disease-modifying therapies

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a central neurodegenerative disease in which adaptive immune cells, especially lymphocytes, as the front line of nerve tissue destruction, independently and by recruiting innate immune cells, have a significant contribution to the pathophysiology of this disease [1]. In particular, the presence of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the environment of nerve tissue and subsequent activation of TH0 CD4 + T cells and proliferation to encephalitogenic phenotypes TH1 or TH17 have been potentially seen in acute neurological lesions associated with MS [2]. In addition, molecules released from CD8 + T present in active and inactive tissues of chronic lesions play a significant role in axonal damage, tissue destruction, and cell death [3]. The importance of this pathophysiology becomes stronger with the presence of B cells. So that their dual role as antigen presenters and activation of autoreactive T cells, as well as damage to the myelin of nerve cells by producing anti-myelin antibodies, could not be ignored [4]. It is worth noting that the cumulative effect of lymphocytes on the severity of the development, progression, and treatment-resistance of the disease according to their ratio in the analysis of CSF fluid of MS patients can also have significant clinical importance [5, 6]. These findings are parallel to the interesting results of in vivo and in vitro reports that cladribine inhibits the development and exacerbation of MS by preventing the infiltration of inflammatory cells and the production of chemokine [7, 8]. All these factors can have a potential role in determining the plan and discovering new strategies for the treatment of this disease according to the lymphocyte-based mechanism of the neuro-degeneration and lymphocyte targeting action of Cladribine as well.

Cladribine (2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine, CdA) is a chlorinated analog of deoxyadenosine [9], which was proposed for the first time in 1977 at the Scripps Research Institute (CA, USA), due to its selective lymphotoxic effect and was proposed as a promising treatment in lymphoid neoplasms and autoimmune diseases. Several clinical trials have been conducted on the effect of this compound in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, mainly multiple sclerosis [10].

The clinical importance of the use of cladribine in the treatment of MS based on the effective presence of lymphocytes and the principle that it exerts its role via destroying them by the final process of apoptosis has been investigated in studies through three phases. In different phases I–III of clinical trials as well as in local studies, the researchers achieved significant findings [11–17]. Despite the volume of sample size and the long follow-up duration among previous studies, the findings are contradictory. These differences are observed in the progression of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score, radiological findings, number of relapses, and the route of administration and dosage. However, based on the available studies, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommended using cladribine tablets (TA493) in relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) [10]. It is worth mentioning that cladribine tablets received the approval of the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2019 and 2020, and received marketing authorization for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS in more than 75 countries [18].

Here, due to the contradictory results of previous studies regarding the efficacy and safety of cladribine in the MS population, we aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis by including clinical trials and observational studies in terms of having more confirmative results to make a general decision.

Methods

This systematic review of the safety and efficacy of cladribine in patients with MS was performed by following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines [19].

Search strategy

The three databases including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were comprehensively searched in May 2022. We used a search strategy consisting of the following terms: “Multiple sclerosis” and “Cladribine” or “Mavenclad” or “Leustatin”. Furthermore, to avoid missing studies, we identified additional articles via the manual search of the reference list of review studies.

Eligibility criteria

We included the studies that investigated the efficacy and safety of cladribine in patients with MS. Eligible studies have to provide sufficient details on MS diagnosis and appropriate follow-up duration (more than 6 months). Non-English studies, case reports, and review articles were excluded.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers (F. A and R. R) performed the selection process in two steps. First, they evaluated titles and abstracts and excluded irrelevant studies. Then, the remained articles entered full-text screening for final selection. Any disagreements were resolved by consulting with a third reviewer (F. N).

Data extraction

The same investigators (F. A and R. R) extracted the following information from included studies based on a prepared data form: study demographics, study design, follow-up duration, number of patients with MS, age, number of females, cladribine dosage, other medications, description of prescription, mean EDSS score before and after taking cladribine, progression-free survival (PFS), relapse-free survival (RFS), MRI free activity survival (MFAS), number of cases with infections, autoimmune disorders, malignancies, and infusion-related side effects. We obtained the data of the last time point for PFS, RFS, MFAS, and EDSS change.

Quality of studies

The quality of observational studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) [20]. Moreover, we used the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool to assess the quality of clinical trials.

Statistical analysis

The R software (version 3.3.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for all statistical analyses. The medians and interquartile range converted to mean and standard deviation based on the Hozo et al. method [21]. We investigated the EDSS change after treatment using a standardized mean difference (SMD) methodology with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The prevalence of adverse events after treatment was measured using Freeman-Tukey’s double arcsine transformation. To assess the heterogeneity among studies, we used I-squared (I2) statistics. The random effect model was used if heterogeneity was high (I2 > 50%), and the fixed effect model was used if I2 < 50%. Also, sensitivity analysis was performed to further validate our analysis. Outlier studies that affected heterogeneity or pooled effect size were detected using the leave-one-out approach. Outlier studies were removed at each step (both overall analysis and subgroup analysis), and all analyses were repeated and results were compared with previous results. Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate the effect of follow-up duration and study type on our results.

Results

Search results and characteristics of included studies

Our initial search and manual hand searching yielded 2024 articles (Fig. 1). After duplicate removal, the title and abstract of 1570 studies were screened and 1494 papers were excluded. Finally, after a full-text review, 23 studies were included in our qualitative and quantitative synthesis [12, 22–43]. A total of 15 clinical trials and eight observational studies involving 7244 MS patients were included in our study (Table 1). The mean NOS score for observational studies was 7.12. Among clinical trials, the risk of bias was low in seven studies while two studies had a high risk of bias (Supplementary 1). Furthermore, there were some concerns regarding the risk of bias in six studies.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram depicting the flow of information through the different phases of a systematic review

Table 1.

Demographical and clinical characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Country | Mean age, years | Dosage of cladribine | Other medications | Mean duration of disease, years | Type of study | Number of MS patients | Number of controls | Number of female | Number of patients RRMS | Description of prescription | Mean EDSS baseline | Follow-up duration, month | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Stefano et al. 2020 | Multicenter | 37.7 | 10 mg | NR | 83.4 ± 83.9 months | RCT | 260 | NR | 172 | NR | tablet | 2.5 | 24 | _ |

| Vermersch et al. 2018 | Germany | 38.1 ± 10.6 | 3.5 mg/kg | NR | 3.86 ± 4.68 | RCT | 98 | NR | 67 | 98 | tablet | 3.01 | NR | _ |

| Thrower et al. 2019 | USA | 38.3018 | 3.5 mg/kg | NR | 8.4 | RCT | 870 | 437 | 288 | 870 | tablet | 2.85 | 24 | _ |

| Stelmasiak et al. 2009 | Poland | Range: 21 − 51 years | 5 mg/day | NR | NR | RCT | 80 | 42 | 49 | 80 | SC | 3.9 | 24 | _ |

| Selby et al. 1998 | Canada | 43 | 0.07 mg/kg/day | NR | 12.6 | RCT | 19 | NR | NR | NR | SC | 6.7 | 17.6 | _ |

| Rice et al. 2000 | USA and Canada | 44.2025 | 0.7 mg/kg or 2.1 mg/kg | NR | 11.2 | RCT | 159 | 54 | 91 | NR | IV | 5.6 | 12 | _ |

| Patti et al. 2020 | Italy | 38.7 ± 10.2 | 3.5 mg/kg or 5.25 mg/kg |

IFN β-1a or 1b 47 Natalizumab 31 Fingolimod 17 Glatiramer acetate Teriflunomide Dimethyl fumarate Azathioprine Cyclophosphamide Laquinimod Mitoxantrone Rituximab Other |

NR | Observational | 80 | NR | 46 | 60 | tablet | NR | 60 | 7 |

| Oh et al. 2021 | Canada | NR | 3.5 mg/kg | NR | NR | RCT | 636 | 641 | NR | NR | tablet | NR | 3 | _ |

| Niezgoda et al. 2001 | Poland and USA | Range: 20 to 50 | 5 mg/day | NR | 4.5 ± 2.2 | RCT | 35 | 10 | 24 | 25 | SC | NR | NR | _ |

| Lizak et al. 2021 | Australia | 47 | 1.75 mg/kg | Interferon β, natalizumab, and glatiramer acetate | 13 | Observational | 88 | NR | 65 | 70 | tablet | 4.7 | 42 | 7 |

| Montalban et al. 2018 | Multicenter | 38.9465 | 3.5 mg/kg | IFN-β | NR | RCT | 172 | 48 | 120 | 107 | tablet | 2.92 | 24 | _ |

| Möhn et al. 2019 | Germany | 49.2941 | NR | Natalizumab | Median: 15.3 | RCT | 17 | NR | 11 | 17 | tablet | 3.34 | 9.7 | _ |

| Moccia et al. 2021 | Italy and UK | 39.4555 | 3.5 mg/kg and 5.25 mg/kg | NR | 9.86 | RCT | 13 | 14 | 17 | 27 | tablet | NR | NR | _ |

| Martinez-Rodriguez et al. 2007 | USA and Spain | 28.2 ± 8.45 | 0.07 mg/kg/day | NR | NR | Observational | 6 | NR | 4 | 6 | NR | 6.47 | 49.3 | 7 |

| Kalincik et al. 2018 | Multicenter | 45 | 3.5 mg/kg | Interferon beta-1a, fingolimod, and natalizumab | 11 | Observational | 679 | 599 | NR | 679 | NR | 3.57 | NR | 8 |

| Galazka et al. 2017 | USA and Canada | 36.5409 | 3.5 mg/kg | NR | 8.34 | RCT | 923 | 641 | 1036 | NR | tablet | NR | > 96 | _ |

| Giovanni et al. 2018 | Multicenter | 41.1223 | 3.5, 5.25, 7, and 8.75 mg/kg | NR | 11 | RCT | 806 | 244 | 531 | 806 | tablet | 2.65 | 24 | _ |

| Allen-philbey et al. 2021 | UK | 44 | 10 mg | NR | 11 | Observational | 208 | NR | 131 | 100 | SC | NR | 19 | 7 |

| Alshamrani et al. 2020 | USA | Median: 47 | 0.07 mg/kg/day | NR | Median: 13 | Observational | 24 | NR | 19 | NR | IV | 4 | 84 | 6 |

| Barros et al. 2020 | Germany | Median: 39 | 3.5 mg/kg | Dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod, natalizumab | Median: 6 | Observational | 270 | NR | 231 | 270 | tablet | 1.99 | 25 | 8 |

| Bose et al. 2021 | Canada | 40.609 | Two courses of 1.75 mg/kg per year, delivered over two treatment weeks separated by 1 month, each consisting for 4 or 5 days of taking one or two 10-mg tablet each day, depending on weight | Alemtuzumab | 8.4 | Observational | 111 | 46 | 84 | 111 | IV | NR | 24 | 7 |

| Comi et al. 2018 | Multicenter | NR | 3.5, 5.25, 7, and 8.75 mg/kg | NR | NR | RCT | 806 | 244 | NR | 806 | tablet | NR | 24 | _ |

| Cook et al. 2017 | Multicenter | NR | 3.5 mg/kg or 5.25 mg/kg | NR | NR | RCT | 884 | 437 | NR | NR | tablet | NR | NR | _ |

RCT, randomized control trial; NR, not reported; MS, multiple sclerosis; RRMS, relapsing–remitting MS; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa scale; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous

Efficacy of cladribine

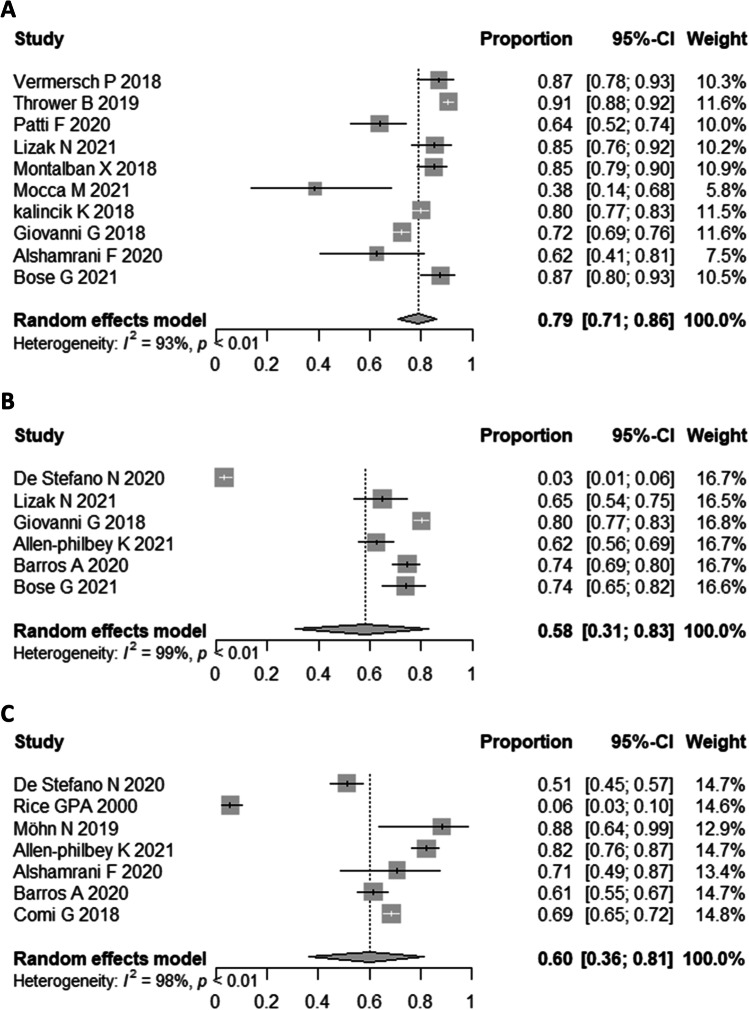

We investigated the efficacy of cladribine with several outcomes including EDSS change, PFS, RFS, and MFAS. The pooled SMD for EDSS before and after treatment was − 0.54 (95%CI: − 1.46, 0.39; P: 0.03, I2 = 72%) (Fig. 2). Our analysis showed that the PFS after cladribine use is 79% (95%CI 71%, 86%; I2 = 93%) (Fig. 3). Also, 58% of patients with MS who received cladribine remained relapse-free (95%CI 31%, 83%; I2 = 99%). Furthermore, the MFAS after treatment was 60% (95%CI 36%, 81%; I2 = 98%).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of EDSS score before and after treatment

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of PFS (A), RFS (B), and MAFS (C) treatment

Sub-group analysis showed 79% (95%CI 64%, 91%; I2 = 96%) PFS in RCTs and 78% (95%CI 67%, 87%; I2 = 80%) PFS in observational studies. Furthermore, the PFS was 81% (95%CI 73%, 89%; I2 = 95%) in studies with less than 24 months of follow-up and 72% (95%CI 55%, 87%; I2 = 84%) in studies with more than 24 months of follow-up.

RFS was 49% (95%CI 26%, 72%; I2 = 97%) in observational studies. Also, sub-group analysis based on follow-up duration revealed that the RFS was 50% (95%CI 10%, 91%; I2 = 98%) in studies with less than 24 months of follow-up and 33% (95%CI 6%, 68%; I2 = 99%) in studies with more than 24 months of follow-up.

Furthermore, the MFAS was 67% (95%CI 48%, 84%; I2 = 92%) in RCTs and 72% (95%CI 57%, 85%; I2 = 92%) in observational studies. Also, the MFAS was higher in studies with less than 24 months of follow-up and 71% (95%CI 55%, 86%; I2 = 95%) compared to studies with more than 24 months of follow-up 62% (95%CI 57%, 68%; I2 = 0%).

Sensitivity analysis showed that after omitting each study, the SMD for EDSS remained insignificant (Supplementary 2). The similar results were obtained for PFS, RFS, and MFAS and the results remained significant (Supplementary 3).

We re-analyzed the data after removing outlier studies (Supplementary 4).

Safety of cladribine

Our analysis showed that infection is the most common adverse event after cladribine treatment with a pooled prevalence of 10% (95%CI 4%, 18%; I2 = 95%, P < 0.01) (Fig. 4). Moreover, the pooled prevalence of infusion-related adverse events was 9% (95%CI 4%, 15%; I2 = 56%, P: 0.11). Also, the malignancies after cladribine were present in 0.4% of patients (95%CI 0.25%, 0.75%; I2 = 32%, P: 0.16). In the next step, sensitivity analysis showed that omitting each study did not influence the results (Supplementary 5). Re-analysis after removing outlier studies detailed in the Supplementary 5.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of pooled prevalence of infusion related complications (A), infections (B), and malignancies (C)

Discussion

The current systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the safety and efficacy of cladribine for MS patients to update clinical decisions for a better therapeutic plan. We have entered 7244 MS patients from 23 included studies. Based on our result, cladribine seems to be a safe and effective drug for the treatment of RRMS patients.

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis study to categorize individual adverse events (AE) to estimate the safety of cladribine therapy in patients with MS. Based on current data analysis, infection with 10% is the most common AE after treatment with cladribine, followed by infusion-related AEs with 9% prevalence and malignancy with 0.4%. In Siddiqui et al., a network meta-analysis was performed to consider an overall AE of each randomized controlled trial [44]. Results showed that there was no significant difference in the safety of cladribine versus the placebo and other disease-modifying therapies (DMT). Results of Albanese et al. also showed that hospitalization and death rates for MS patients with COVID-19 treated with cladribine were 9.36% and 0% respectively; however, these numbers in a similar situation with alternative treatments were higher for both indexes [45]. Therefore, cladribine seems to be a safe treatment for RRMS patients, especially in times of the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 strains [46]. Furthermore, compared to other commonly used DMTs, such as dimethyl fumarate [47, 48], fingolimod [49, 50], and natalizumab [51], cladribine is a safer therapeutic option with less known or rare AEs [52].

We also investigated the efficacy of cladribine by measuring several outcomes including MFAS, PFS, RFS, and change in EDSS. However, MFAS, PFS, and RFS seem to be acceptable. Our findings revealed that cladribine has no significant effect on EDSS reduction among MS patients. For a synthetic drug known as a first-line DMT, cladribine can target both B and T (CD4+ and CD8+) lymphocytes and exploit the enzymatic deoxycytidine degradation [10, 53, 54]. With a 40% estimated bioavailability, cladribine can properly penetrate CNS. However, with blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption as a common pathological finding at all MS disease stages, cladribine can penetrate better to the CNS of MS patients [55–57]. Cladribine can interfere with DNA repair and synthesis processes through inclusion with enzymes that contributed to DNA metabolism, ribonucleotide reductase, and DNA polymerase, for example, leading to DNA breakage and cell death [58].

Despite a great impact on reducing the relapse frequency of RRMS, DMTs mechanisms of action are limited to prevent the inevitable transition of RRMS patients to non-active primary or secondary PMS. However, cladribine is found to affect a mix of active and non-active PMS patients [59–61]. Based on Siddiqui et al. [44], cladribine tablets are equal to or considerably better than the placebo with a 58% reduction in annualized relapse rate (ARR) (P < 0.05). Similar to our findings, with a − 0.54 EDSS score and 58% better RFS, confirmed disease progression (CDP) for 6 months and no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) of cladribine were significantly higher than the placebo (P < 0.05). Compared to other DMTs, such as interferon, glatiramer acetate, and dimethyl fumarate, cladribine has a significantly lower ARR. In the subgroup of high-disease activity patients, the beneficial effect of cladribine was also amplified [62, 63]. However, ARR for cladribine was significantly higher compared to natalizumab, a possible disadvantage of cladribine tablets for MS patients [63]. In Bartosik-Psujek et al., cladribine tablets were significantly more efficient in attaining NEDA than dimethyl fumarate and teriflunomide, but there was no considerable difference compared to fingolimod, which is similar to the results of our study maintaining 79% better PFS and 60% improved MFAS after treatment with cladribine [64].

The role of cladribine is also investigated in the treatment of hematological cancers, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) for example. As one of the most severe forms of bone marrow malignancies, most attempts to uptake immune response and improve survival of AML patients remained unsuccessful; and complete remission, especially in relapsed AML patients, remained a great challenge to be addressed [65, 66]. Scientists have studied the use of cladribine, either alone or in combination with a standard regime. Results of several studies confirmed the anti-leukemic activity with a lack of prohibitive non-hematologic toxicity of cladribine for children with AML [67, 68]. The combination of cladribine with cytarabine [69] and topotecan [70] was well tolerated, and response rates were found to be hopeful for AML patients, leading to the development of safe and effective therapeutic methods for non-MS patients as well.

Limitations and future

Similar to the other works, this study was not without limitations. The longest follow-up period was extracted from studies as the end-point for assessing efficacy and safety; however, the follow-up duration varied from 3 to more than 96 months, making the selection range so extensive. The dosage and use duration of cladribine also differed among studies; a potential drawback could result in a false conclusion when gathered for the pooled analysis. However, after sub-group analysis based on follow-up duration and study design, the heterogeneity remained high. Safety should also be considered with more attention, as there was considerable heterogeneity in the analysis. Other demographical and clinical characteristics such as RRMS to MS patients ratio, as well as a form of prescription (tablet, SC, IV) of cladribine can also be a case of bias, as all are taken similarly for treatment of patients with MS. There is still a lot to investigate to address drawbacks of cladribine administration for patients with MS, for inevitable AEs (mainly in immunocompromised patients) and lower effectiveness in several outcomes. Until that time, cladribine can be considered a safe and effective DMT against patients with RRMS, and a considerable pace of further studies are required to get a better inside around the prescription of cladribine in MS patients. Also, there is need for more data on whether cladribine should prescribe as first-line therapy or used after DMTs.

Conclusion

MS is a progressive disease with no certain cure for patients who face relapsed neurological impairments after the onset of the disease. Our results showed acceptable safety and efficacy for cladribine for the treatment of MS except in terms of reducing EDSS. Combination of our findings with the results of previous studies which compared cladribine to other DMTs, cladribine seems to be a safe and effective drug in achieving better treatment for RRMS patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

Fardin Nabizadeh, Omid Mirmosayyeb, Mobin Mohamadi, Shayan Rahmani, and Soroush Najdaghi: designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; Fardin Nabizadeh, Rayan Rajabi, and Fatemeh Afrashteh: collected data, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the draft version of the manuscript. The manuscript was revised and approved by all authors.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available upon request with no restriction.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

This manuscript has been approved for publication by all authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and animal rights

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ward M, Goldman MD (2022) Epidemiology and pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology 28(4):988–1005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Hedegaard CJ, Krakauer M, Bendtzen K, Lund H, Sellebjerg F, Nielsen CH. T helper cell type 1 (Th1), Th2 and Th17 responses to myelin basic protein and disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Immunology. 2008;125(2):161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denic A, Wootla B, Rodriguez M. CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17(9):1053–1066. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.815726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gharibi T, Babaloo Z, Hosseini A, Marofi F, Ebrahimi-kalan A, Jahandideh S, et al. The role of B cells in the immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Immunology. 2020;160(4):325–335. doi: 10.1111/imm.13198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cepok S, Jacobsen M, Schock S, Omer B, Jaekel S, Böddeker I, et al. Patterns of cerebrospinal fluid pathology correlate with disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2001;124(11):2169–2176. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.11.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenfield AL, Dandekar R, Ramesh A, Eggers EL, Wu H, Laurent S et al (2018) Longitudinally persistent cerebrospinal fluid B-cells resist treatment in multiple sclerosis. bioRxiv. 490938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Kraus SH, Luessi F, Trinschek B, Lerch S, Hubo M, Poisa-Beiro L, et al. Cladribine exerts an immunomodulatory effect on human and murine dendritic cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;18(2):347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kopadze T, Döbert M, Leussink V, Dehmel T, Kieseier B. Cladribine impedes in vitro migration of mononuclear cells: a possible implication for treating multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(3):409–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beutler E. Cladribine (2-chlorodeoxyadenosine) The Lancet. 1992;340(8825):952–956. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92826-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sipe JC. Cladribine for multiple sclerosis: review and current status. Expert Rev Neurother. 2005;5(6):721–727. doi: 10.1586/14737175.5.6.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beutler E, Sipe J, Romine J, Koziol J, McMillan R, Zyroff J. The treatment of chronic progressive multiple sclerosis with cladribine. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93(4):1716–1720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rice GP, Filippi M, Comi G. Cladribine and progressive MS: clinical and MRI outcomes of a multicenter controlled trial. Neurology. 2000;54(5):1145–1155. doi: 10.1212/WNL.54.5.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montalban X, Cohen B, Leist T, Moses H, Hicking C, Dangond F (2016) Efficacy of cladribine tablets as add-on to IFN-beta therapy in patients with active relapsing MS: final results from the phase II ONWARD study (P3. 029). AAN Enterprises

- 14.Romine JS, Sipe JC, Koziol JA, Zyroff J, Beutler E. A Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of cladribine in relpaasing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1999;111(1):35–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1381.1999.09115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stelmasiak Z, Solski J, Nowicki J, Jakubowska B, Ryba M, Grieb P. Effect of parenteral cladribine on relapse rates in patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis: results of a 2-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Mult Scler J. 2009;15(6):767–770. doi: 10.1177/1352458509103610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leist TP, Comi G, Cree BA, Coyle PK, Freedman MS, Hartung H-P, et al. Effect of oral cladribine on time to conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis in patients with a first demyelinating event (ORACLE MS): a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(3):257–267. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giovannoni G, Comi G, Cook S, Rammohan K, Rieckmann P, Sørensen PS, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral cladribine for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(5):416–426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rammohan K, Coyle PK, Sylvester E, Galazka A, Dangond F, Grosso M, et al. The development of cladribine tablets for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive review. Drugs. 2020;80(18):1901–1928. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01422-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo CK-L, Mertz D, Loeb M (2014) Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol 14(1):45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen-Philbey K, De Trane S, Mao Z, Álvarez-González C, Mathews J, MacDougall A, et al. Subcutaneous cladribine to treat multiple sclerosis: experience in 208 patients. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021;14:17562864211057661. doi: 10.1177/17562864211057661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alshamrani F, Alnajashi H, Almuaigel MF. Efficacy and safety of intravenous cladribine in patients with rapidly evolving or early secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e6995. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barros A, Santos M, Sequeira J, Brum M, Parra J, Leitao L et al (2020) Effectiveness of cladribine in multiple sclerosis—clinical experience of two tertiary centers. Mult Scler J 26(3_SUPPL):278-

- 25.Bose G, Rush C, Atkins HL, Freedman MS. A real-world single-centre analysis of alemtuzumab and cladribine for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;52:102945. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.102945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Comi G, Leist T, Freedman MS, Cree BAC, Coyle PK, Hartung HP et al (2018) Cladribine tablets in the ORACLE-MS study open-label maintenance period: analysis of efficacy in patients after conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis (CDMS). Mult Scler J 24(2):NP5-NP

- 27.Cook S, Leist T, Comi G, Montalban X, Sylvester E, Hicking C et al (2017) Cladribine tablets in the treatment of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS): an integrated analysis of safety from the MS clinical development program. Neurology 88

- 28.De Stefano N, Achiron A, Barkhof F, Chan A, Derfuss T, Hodgkinson S et al (2020) A 2-year study to evaluate the onset of action of cladribine tablets in subjects with highly active relapsing multiple sclerosis: results from MAGNIFY-MS baseline analysis. Neurology 94(15)

- 29.Galazka A, Nolting A, Cook S, Leist T, Comi G, Montalban X, et al. An analysis of malignancy risk in the clinical development programme of cladribine tablets in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS) Mult Scler J. 2017;23:999–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giovannoni G, Soelberg Sorensen P, Cook S, Rammohan KW, Rieckmann P, Comi G, et al. Efficacy of cladribine tablets in high disease activity subgroups of patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: a post hoc analysis of the CLARITY study. Mult Scler. 2019;25(6):819–827. doi: 10.1177/1352458518771875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalincik T, Jokubaitis V, Spelman T, Horakova D, Havrdova E, Trojano M, et al. Cladribine versus fingolimod, natalizumab and interferon for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J. 2018;24(12):1617–1626. doi: 10.1177/1352458517728812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lizak N, Hodgkinson S, Butler E, Lechner-Scott J, Slee M, McCombe PA, et al. Real-world effectiveness of cladribine for Australian patients with multiple sclerosis: an MSBase registry substudy. Mult Scler. 2021;27(3):465–474. doi: 10.1177/1352458520921087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez-Rodriguez JE, Cadavid D, Wolansky LJ, Pliner L, Cook SD. Cladribine in aggressive forms of multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(6):686–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moccia M, Lanzillo R, Petruzzo M, Nozzolillo A, De Angelis M, Carotenuto A, et al. Single-center 8-years clinical follow-up of cladribine-treated patients from phase 2 and 3 Trials. Front Neurol. 2020;11:489. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Möhn N, Skripuletz T, Sühs KW, Menck S, Voß E, Stangel M. Therapy with cladribine is efficient and safe in patients previously treated with natalizumab. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:1756286419887596. doi: 10.1177/1756286419887596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montalban X, Leist TP, Cohen BA, Moses H, Campbell J, Hicking C et al (2018) Cladribine tablets added to IFN-β in active relapsing MS. Neurology: Neuroimmunol NeuroInflamm 5(5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Niezgoda A, Losy J, Mehta PD. Effect of cladribine treatment on beta-2 microglobulin and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) in patients with multiple sclerosis. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2001;60(3):225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oh J, Walker B, Giovannoni G, Jack D, Dangond F, Nolting A, et al. Treatment-emergent adverse events occurring early in the treatment course of cladribine tablets in two phase 3 trials in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2021;7(3):20552173211024298. doi: 10.1177/20552173211024298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patti F, Visconti A, Capacchione A, Roy S, Trojano M, Grp C-MS (2020) Long-term effectiveness in patients previously treated with cladribine tablets: a real-world analysis of the Italian multiple sclerosis registry (CLARINET-MS). Ther Adv Neurol Disord 13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Selby R, Brandwein J, O’Connor P. Safety and tolerability of subcutaneous cladribine therapy in progressive multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 1998;25(4):295–299. doi: 10.1017/S0317167100034302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stelmasiak Z, Solski J, Nowicki J, Jakubowska B, Ryba M, Grieb P. Effect of parenteral cladribine on relapse rates in patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis: results of a 2-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Mult Scler. 2009;15(6):767–770. doi: 10.1177/1352458509103610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thrower B, Fox EJ, Damian D, Lebson L, Dangond F. Risk reduction of EDSS progression in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis treated with cladribine tablets in the CLARITY study: post-hoc analysis including patients who went on to receive rescue therapy. Mult Scler J. 2019;25:306–307. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vermersch P, Giovannoni G, Soelberg-Sorensen P, Keller B, Jack D. Sustained efficacy in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis following switch to placebo treatment from cladribine tablets in patients with high disease activity at baseline. Mult Scler J. 2018;24:268–269. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siddiqui MK, Khurana IS, Budhia S, Hettle R, Harty G, Wong SL. Systematic literature review and network meta-analysis of cladribine tablets versus alternative disease-modifying treatments for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(8):1361–1371. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1407303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Albanese A, Sormani MP, Gattorno G, Schiavetti I. COVID-19 severity among patients with multiple sclerosis treated with cladribine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Dis. 2022;68:104156. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.104156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rahmani S, Rezaei N (2022) SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant: no time to wait! Acta Bio-Med: Atenei Parmensis 93(2):e2022097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Diebold M, Altersberger V, Décard BF, Kappos L, Derfuss T, Lorscheider J. A case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy under dimethyl fumarate treatment without severe lymphopenia or immunosenescence. Mult Scler J. 2019;25(12):1682–1685. doi: 10.1177/1352458519852100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kresa-Reahl K, Repovic P, Robertson D, Okwuokenye M, Meltzer L, Mendoza JP. Effectiveness of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate on clinical and patient-reported outcomes in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis switching from glatiramer acetate: RESPOND, a prospective observational study. Clin Ther. 2018;40(12):2077–2087. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.London F, Cambron B, Jacobs S, Delrée P, Gustin T. Glioblastoma in a fingolimod-treated multiple sclerosis patient: causal or coincidental association? Mult Scler Relat Dis. 2020;41:102012. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma SB, Griffin DWJ, Boyd SC, Chang CC, Wong JSJ, Guy SD. Cryptococcus neoformans var grubii meningoencephalitis in a patient on fingolimod for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: case report and review of published cases. Mult Scler Relat Dis. 2020;39:101923. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.101923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alping P, Askling J, Burman J, Fink K, Fogdell-Hahn A, Gunnarsson M, et al. Cancer risk for fingolimod, natalizumab, and rituximab in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2020;87(5):688–699. doi: 10.1002/ana.25701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aruta F, Iovino A, Costa C, Manganelli F, Iodice R. Lichenoid rash: a new side effect of oral cladribine. Mult Scler Relat Dis. 2020;41:102023. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawasaki H, Carrera CJ, Piro LD, Saven A, Kipps TJ, Carson DA. Relationship of deoxycytidine kinase and cytoplasmic 5′-nucleotidase to the chemotherapeutic efficacy of 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. Blood. 1993;81(3):597–601. doi: 10.1182/blood.V81.3.597.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rafiee Zadeh A, Ghadimi K, Ataei A, Askari M, Sheikhinia N, Tavoosi N et al (2019) Mechanism and adverse effects of multiple sclerosis drugs: a review article. Part 2. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 11(4):105–14 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Cramer SP, Simonsen H, Frederiksen JL, Rostrup E, Larsson HB. Abnormal blood-brain barrier permeability in normal appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis investigated by MRI. NeuroImage Clinical. 2014;4:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liliemark J. The clinical pharmacokinetics of cladribine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32(2):120–131. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yates RL, Esiri MM, Palace J, Jacobs B, Perera R, DeLuca GC. Fibrin(ogen) and neurodegeneration in the progressive multiple sclerosis cortex. Ann Neurol. 2017;82(2):259–270. doi: 10.1002/ana.24997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leist TP, Weissert R. Cladribine: mode of action and implications for treatment of multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34(1):28–35. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e318204cd90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manouchehri N, Salinas VH, Rabi Yeganeh N, Pitt D, Hussain RZ, Stuve O. Efficacy of disease modifying therapies in progressive MS and how immune senescence may explain their failure. Front Neurol. 2022;13:854390. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.854390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Montalban X, Leist TP, Cohen BA, Moses H, Campbell J, Hicking C et al (2018) Cladribine tablets added to IFN-β in active relapsing MS: the ONWARD study. Neurology(R) Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 5(5):e477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Rice GP, Filippi M, Comi G. Cladribine and progressive MS: clinical and MRI outcomes of a multicenter controlled trial. Cladribine MRI study group. Neurology. 2000;54(5):1145–1155. doi: 10.1212/WNL.54.5.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalincik T, Jokubaitis V, Spelman T, Horakova D, Havrdova E, Trojano M, et al. Cladribine versus fingolimod, natalizumab and interferon β for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J. 2017;24(12):1617–1626. doi: 10.1177/1352458517728812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Signori A, Saccà F, Lanzillo R, Maniscalco GT, Signoriello E, Repice AM et al (2020) Cladribine vs other drugs in MS: merging randomized trial with real-life data. Neurology(R) Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 7(6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Bartosik-Psujek H, Kaczyński Ł, Górecka M, Rolka M, Wójcik R, Zięba P, et al. Cladribine tablets versus other disease-modifying oral drugs in achieving no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) in multiple sclerosis—a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Dis. 2021;49:102769. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.102769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rahmani S, Yazdanpanah N, Rezaei N (2022) Natural killer cells and acute myeloid leukemia: promises and challenges. Cancer Immunol Immunother [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Qasrawi A, Bahaj W, Qasrawi L, Abughanimeh O, Foxworth J, Gaur R. Cladribine in the remission induction of adult acute myeloid leukemia: where do we stand? Ann Hematol. 2019;98(3):561–579. doi: 10.1007/s00277-018-3562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Santana VM, Mirro J, Jr, Harwood FC, Cherrie J, Schell M, Kalwinsky D, et al. A phase I clinical trial of 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine in pediatric patients with acute leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(3):416–422. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Santana VM, Mirro J, Jr, Kearns C, Schell MJ, Crom W, Blakley RL. 2-Chlorodeoxyadenosine produces a high rate of complete hematologic remission in relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(3):364–370. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.3.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rubnitz JE, Crews KR, Pounds S, Yang S, Campana D, Gandhi VV, et al. Combination of cladribine and cytarabine is effective for childhood acute myeloid leukemia: results of the St Jude AML97 trial. Leukemia. 2009;23(8):1410–1416. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Inaba H, Stewart CF, Crews KR, Yang S, Pounds S, Pui CH, et al. Combination of cladribine plus topotecan for recurrent or refractory pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2010;116(1):98–105. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available upon request with no restriction.