Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) causes motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunctions. The gut microbiome has an important role in SCI, while short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are one of the main bioactive mediators of microbiota. In the present study, we explored the effects of oral administration of exogenous SCFAs on the recovery of locomotor function and tissue repair in SCI. Allen’s method was utilized to establish an SCI model in Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats. The animals received water containing a mixture of 150 mmol/L SCFAs after SCI. After 21 d of treatment, the Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan (BBB) score increased, the regularity index improved, and the base of support (BOS) value declined. Spinal cord tissue inflammatory infiltration was alleviated, the spinal cord necrosis cavity was reduced, and the numbers of motor neurons and Nissl bodies were elevated. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), and immunohistochemistry assay revealed that the expression of interleukin (IL)-10 increased and that of IL-17 decreased in the spinal cord. SCFAs promoted gut homeostasis, induced intestinal T cells to shift toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype, and promoted regulatory T (Treg) cells to secrete IL-10, affecting Treg cells and IL-17 + γδ T cells in the spinal cord. Furthermore, we observed that Treg cells migrated from the gut to the spinal cord region after SCI. The above findings confirm that SCFAs can regulate Treg cells in the gut and affect the balance of Treg and IL-17 + γδ T cells in the spinal cord, which inhibits the inflammatory response and promotes the motor function in SCI rats. Our findings suggest that there is a relationship among gut, spinal cord, and immune cells, and the “gut-spinal cord-immune” axis may be one of the mechanisms regulating neural repair after SCI.

Keywords: Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), Spinal cord injury (SCI), Regulatory T cells, IL-17 + γδ T cells, Neuroprotection, Inflammation, Motor function recovery

Abstract

脊髓损伤可以引起运动、感觉和自主神经功能障碍。肠道微生物组在脊髓损伤中具有重要作用,而短链脂肪酸是微生物群的主要生物活性介质之一。在本研究中,我们探讨了口服外源性短链脂肪酸对脊髓损伤运动功能恢复和组织修复的影响。采用Allen方法建立SD大鼠脊髓损伤模型。脊髓损伤后,动物接受含有150 mmol/L短链脂肪酸混合物的水。治疗21天后,BBB评分升高,步态的规律性指数改善,后肢步宽值下降。脊髓组织炎症浸润减轻,脊髓坏死腔减少,运动神经元和尼氏体数量升高。酶联免疫吸附测定(ELISA)、实时定量聚合酶链反应(qPCR)和免疫组化检测显示脊髓中白细胞介素-10(IL-10)表达升高,IL-17表达降低。短链脂肪酸能促进肠道稳态,诱导肠道T细胞转向抗炎表型,促进调节性T细胞(Treg)分泌IL-10,影响脊髓中的Treg细胞和IL-17 + γδ T细胞。此外,我们观察到脊髓损伤后Treg细胞从肠道迁移到脊髓区域。以上结果证实,短链脂肪酸可调节肠道中的Treg细胞,影响脊髓中Treg和IL-17 + γδ T细胞的平衡,抑制炎症反应,促进脊髓损伤大鼠的运动功能。我们的研究结果表明,肠道、脊髓和免疫细胞之间存在一定的关系,“肠道-脊髓-免疫”轴可能是脊髓损伤后神经修复的调节机制之一。

Keywords: 短链脂肪酸, 脊髓损伤, 调节性T细胞, IL-17 + γδ T细胞, 神经保护, 炎症, 运动功能恢复

1. Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) causes motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunctions ( Eli et al., 2021). As a result of SCI, the sympathetic control of the gastrointestinal tract is lost, which leads to acute and persistent gastrointestinal problems including intestinal barrier dysfunction, deficits in motility, and compromised immune function ( Cervi et al., 2014; Tate et al., 2016). The gut microbiota may be an important factor in gut and immune dysfunction ( Jing et al., 2021b; Lu et al., 2022). Neuronal lower urinary tract dysfunction is also one of the common complications after SCI, which seriously affects the life quality of patients ( Dodd et al., 2022). Exploring the correlation between urine microbiome and clinical presentation in patients with neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction may help to guide treatment strategies ( Lane et al., 2022).

Recent studies have shown that the gut microbiota after SCI becomes disordered, bacterial diversity declines, potential pathogenic or pro-inflammatory bacteria increase, and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria dwindle, which leads to gut dysfunction and exacerbates inflammatory responses, thus affecting the recovery of motor function after SCI ( Kigerl et al., 2016; Bazzocchi et al., 2021; Valido et al., 2022). Jing et al. (2021a) demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) can improve motility and gastrointestinal function in SCI mice via the anti-inflammatory effect of SCFAs. The spinal cord, gut, and immune system form an interactive network, where damage or dysfunction to any of the components can alter the homeostasis and cause disease ( Kigerl et al., 2018).

Gut microbiota and their metabolic products play an important role in the clinical outcome of SCI. As one of the main bioactive mediators produced by microbiota, the potential application of SCFAs in SCI remains to be further explored. To identify new therapeutic strategies for SCI, we explored the effects of oral administration of exogenous SCFAs on motor function recovery and tissue repair in SCI from the behavioral to the cellular level.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental animals

Sixty-five female Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (age: 4‒6 weeks; weight: (200±20) g) were provided by and housed in the Animal Experimental Centre of Guangxi Medical University (license No. SCXK(Gui)2014-0005). The animals were kept in a room with a 12/12-h light/dark cycle at 20‒25 ℃ with access to food and water ad libitum.

2.2. Study groups and SCI model establishment

The rats were divided into a sham operated group, SCI group, and SCFA-treated group. In the sham group, there was no SCI by laminectomy alone. Allen’s method was utilized to establish an SCI model ( Allen, 1911). The sham and SCI groups were provided with ordinary water, and the SCFA-treated group was given water containing a mixture of 150 mmol/L acetate sodium, propionate sodium, and butyrate sodium (all from Sigma (St. Louis, Missouri, USA) with catalog Nos. of 71183, 303410, and P5436, respectively) in a volume ratio of 12:5:3 after SCI. The concentrations and ratios of SCFAs were chosen in accordance with previous studies ( Ramos et al., 1997; Ferreira et al., 2012; Lucas et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020). Each group was randomly divided into four subgroups with five rats each. One of the subgroup samples was used for hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, Nissl staining, and immunohistochemistry. Samples of another subgroup were taken for flow cytometry analysis. The tissues of the remaining two groups were used for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), respectively. Additionally, five SCI rats were used for the migration assay.

2.3. Behavioral analysis

The rats were assessed for locomotor function using the Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan (BBB) motor rating scale ( Basso et al., 1995, 1996) after SCI was induced. Each animal was independently assessed for 4 min by three reviewers blinded to the study group, and the mean of the measurements was used.

The catwalk gait analysis system (VisuGait, Shanghai, China) was adopted to measure the gait parameters of each group on Day 21 post-injury. The recording criterion was that the rats could continuously run through the channel without stopping in less than 10 s. Since SCI at the T10 level is primarily a hind limb dysfunction, gait data from the hind limbs of the rats were collected in this study.

2.4. Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining

Tissue samples were taken on Day 21 post-injury. Spinal cord samples containing the injury epicenter and terminal ileum samples were taken from rats after being transcardially perfused with 4% (volume fraction) paraformaldehyde (P1110; Solarbio, Beijing, China). Representative sections of the paraffin-embedded tissue were cut and deparaffinized with xylene (10023418; Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and graded ethanol (100092683; Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.), and then mounted on slides for HE staining (G1003; Servicebio, Wuhan, China). Random sections were picked from each set, observed and photographed under a Zeiss microscope (Axio Imager A2, Jena, Germany). ImageJ 5.0 software (Rawak Software Inc., Stuttgart, Germany) was used to analyze the villus length, crypt length, and mucosal thickness in each group.

2.5. Nissl staining

The paraffin section was deparaffinized with xylene and graded ethanol, followed by rinsing in distilled water. Then, the sections were stained with Nissl staining (G1036; Servicebio) for 5 min. After rinsing in distilled water and thorough drying, the sections were fixed with neutral gum and observed under a Zeiss microscope. ImageJ 5.0 software was employed to analyze the number of spinal motor neurons.

2.6. ELISA

After the rats were sacrificed, the spinal cord segment containing the injury epicenter was removed. This was added with radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (P0013B; Beyotime, Beijing, China), homogenized thoroughly, and then incubated on ice to allow the cells to cleave fully. After centrifugation, the supernatant was carefully collected for detection. The concentrations of interleukin (IL)-10 and IL-17A in spinal cord tissues were determined with ELISA kits (Mlbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

2.7. qPCR

RNAiso Plus (9109; TaKaRa, Dalian, China) was used to extract the total RNA from spinal cord tissues. RNA was detected based on the ratio of absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm ( A 260/ A 280) (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) to assess the integrity of the RNA. The RNA PCR kit (RR019A; TaKaRa) was utilized to synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) from total RNA. PCR amplification was performed with a TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (RR820B; TaKaRa). The relative expression of each target gene was determined by the 2 method. The rat primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for PCR

| Target gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| IL-17A | 5'-AGTGTGTCCAAACGCCGAG-3' | 5'-GTCCAGGGTGAAGTGGAACG-3' |

| IL-10 | 5'-AGCAAAGGCCATTCCATCCG-3' | 5'-CACTTGACTGAAGGCAGCCC-3' |

| GAPDH | 5'-GGCACAGTCAAGGCTGAGAATG-3' | 5'-ATGGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGTA-3' |

PCR: polymerase chain reaction; IL: interleukin; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

2.8. Immunohistochemistry

The paraffin slices of the spinal cord were deparaffinized with xylene and graded ethanol. Then, citric acid antigen repair buffer (G1202, Servicebio) was used for antigen repair. After washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (G0002; Servicebio), the slices were incubated with 3% (volume fraction) hydrogen peroxide solution (10011208, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.) for 25 min in the dark. Next, 3% (0.03 g/mL) bovine serum albumin (BSA) (G5001; Servicebio) was added, followed by sealing for 30 min and incubation with rabbit polyclonal anti-IL-10 (GB11534; Servicebio) or rabbit polyclonal anti-IL-17 (GB11110; Servicebio) primary antibodies overnight in a humid box at 4 ℃. After rinsing with PBS, the slices were added with secondary antibody (GB23303; Servicebio) and incubated for 50 min. Images were captured using a Zeiss microscope. The relative gray value was calculated by ImageJ 5.0 software.

2.9. Lymphocyte isolation from spinal cord and terminal ileum

The spinal cords were digested in PBS containing 25 mg trypsin (P-9460; Solarbio) and 50 mg collagenase IV (17104019; Gibco, USA) for 20 min. Subsequently, the cell suspension was resuspended in 30% (volume fraction) Percoll solution (P8370; Solarbio) and overlaid on 70% Percoll solution. The interphase cells were collected for flow cytometric analysis after being centrifuged at 500 g for 30 min.

The terminal ilea tissues were cut into small pieces, and digested in PBS containing 0.5 mg/mL deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I) (D8071; Solarbio), 4% (volume fraction) fetal calf serum, 50 U/mL neutral protease (Z8031; Solarbio), and 0.5 mg/mL collagenase IV (17104019; Gibco). This was performed in a shaking incubator, and the cell suspension of the intrinsic layer of single nucleated cells was collected, filtered, and washed. The same gradient centrifugation was used to collect cells on the interphase for flow cytometric analysis.

2.10. Flow cytometry

The density of the cell suspension was adjusted, and cells were stained in the dark for 20 min with cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) (11-0040-82; Monoclonal Antibody (OX35), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), eBioscience, San Diego, USA), CD3 (11-0030-82; Monoclonal Antibody (G4.18), FITC, eBioscience), CD25 (17-0390-82; Monoclonal Antibody (OX39), allophycocyanin (APC), eBioscience), and T cell receptor (TCR)-γδ (202605; Monoclonal Antibody (V65), phycoerythrin (PE), BioLegend) for surface marker analysis. For intracellular staining, surface marker staining was first performed. After fixation and permeation with fixative and permeation buffers, respectively, FoxP3 (12-4774-42; Monoclonal Antibody (150D/E4), PE, eBioscience) and IL-17A (17-7177-81; Monoclonal Antibody (eBio17B7), APC, eBioscience) were added, followed by incubation for 30 min. Cells were subjected to flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, California, USA) after washing and resuspension. The analysis was performed with CytExpert 2.0 software (Beckman Coulter).

2.11. Isolation of Treg cells and γδ T cells

The lymphocytes isolated from terminal ilea were suspended in 100 μL MACS running buffer cell separation solution (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany), and the cell concentration was adjusted to 1×10 7 cells/mL. Cell suspensions were incubated with CD4-APC and CD25-PE antibodies. Next, the separation column (Miltenyi Biotec) was installed, and CD4 + cells were adsorbed by anti-APC multi-sorting magnetic beads on MACS Separators (Miltenyi Biotec). Once the release of multi-sorting magnetic beads was completed, CD25 + cells were sorted using anti-PE magnetic beads. For γδ T cells, γδ TCR antibody coupled to magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) was added. The mixture was incubated at 4 °C in the dark for 25 min, followed by washing and resuspension. The Miltenyi separation solumn was used to adsorb TCR-γδ + cells. Subsequently, the magnetic field was removed, the positively selected cells were washed out to be γδ T cells, and the sorted cells were transferred to Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium (G4534, Servicebio).

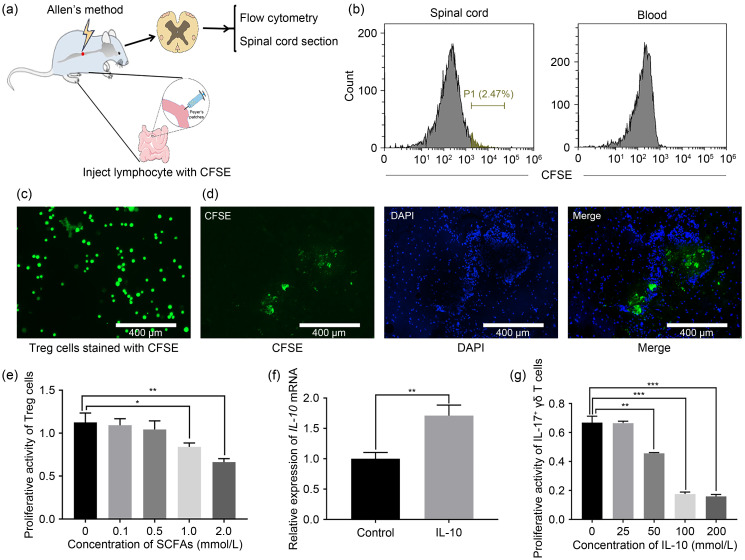

2.12. Tracing the migration of Treg cells from the gut to the spinal cord region

Two days after SCI surgery, 2 μL carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl amino ester (CFSE) (65-0850-84; eBioscience)-labeled regulatory T (Treg) cells were injected into the Peyer’s patches ( Benakis et al., 2016). The labeled Treg cells in the spinal cord and blood were detected after 24 h. The spinal cord tissue was removed, embedded with tissue optimum cutting temperature (OCT)-freeze medium (4583; Sakura, USA), and fixed in the slicer for continuous slicing. Next, the slices were sealed with anti-fluorescence fade solution. Finally, the distribution of lymphocytes (CFSE-labeled) in the spinal cord was observed under a fluorescent microscope (EVOS FL Auto, Massachusetts, USA).

2.13. Cell cytotoxicity and proliferation assay

Treg cells and γδ T cells were collected and suspended in RPMI-1640 medium at a concentration of 2×10 4 cells/mL. The cell suspension was inoculated overnight in 96-well plates containing 100 μL medium per well. The Treg cells treated with SCFAs (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mmol/L) and γδ T cells treated with IL-10 (0, 50, 100, and 150 mmol/L) were incubated with 5% (volume fraction) CO2 at 37 °C. Next, 100 μL fresh RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% (volume fraction) cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent (Dojindo, Japan) was added to each well and the cells were incubated in the dark. The absorbance of each well was measured at 450 nm wavelength using an enzyme marker (Gen5; BioTek, USA).

2.14. Statistical analysis

The SPSS statistical software (V23.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was employed to analyze the data. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze differences between groups. In addition, the Pearson’s correlation method was applied to evaluate the correlations. All data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). Differences of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Improvement of locomotor recovery in SCI via orally administered SCFAs

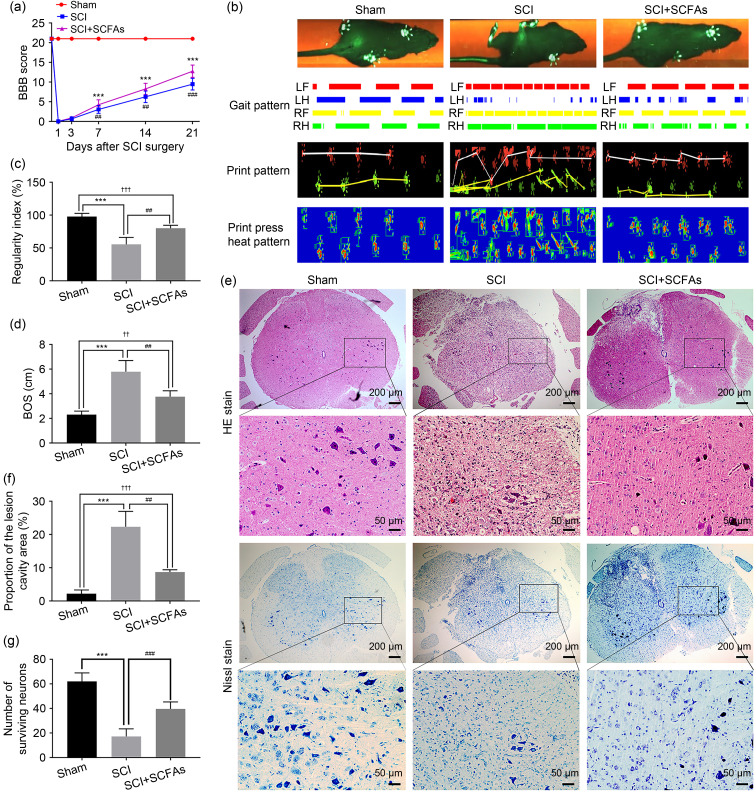

In order to determine whether gut microbiota metabolite SCFAs affected the recovery of SCI, acetate sodium, propionate sodium, and butyrate sodium were orally administered to post-SCI rats through the animals’ drinking water for 21 d until euthanasia. After observing the locomotor recovery during these three weeks, there was no remarkable improvement in hind limb motor function in the SCI group or the SCFA group at 3 and 7 d following injury. The motor function of the hind limbs was significantly enhanced 14 d after injury in the SCFA-treated group, and the improvement in BBB score continued up to the end of the experiment ( Fig. 1a). Due to the subjectivity of BBB score, we used catwalk to evaluate the recovery of hind limb motor function in rats with SCI. After three weeks of SCI, the sequence in the SCFA treatment group was significantly improved, and the base of support (BOS) value of the hind limbs was significantly decreased in the SCI group ( Figs. 1b‒1d). In conclusion, rats treated with SCFAs exhibited relatively enhanced motor recovery.

Fig. 1. Improvement of locomotor recovery in SCI via exogenously administered oral SCFAs. (a) The BBB score of each group was recorded. (b) The typical "catwalk" image of each group at 21 d after SCI. (c) The regularity indexes of the different groups were analyzed. (d) The BOS value of the rat hind limb was determined. (e) Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining was used to assess injury in spinal cord slices from different groups. Representative images of Nissl staining for spinal motor neurons. (f) The proportion of the lesion cavity area to the total area was calculated. (g) The number of surviving motor neurons was counted after Nissl staining. Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), n=5. *** P<0.001, SCI vs. sham; ## P<0.01, ### P<0.001, SCI vs. SCI+SCFAs; †† P<0.01, ††† P<0.001, SCI+SCFAs vs. sham. SCI: spinal cord injury; SCFAs: short-chain fatty acids; BBB: Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan; BOS: base of support; LF: left forelimb; LH: left hindlimb; RF: right forelimb; RH: right hindlimb.

The results of HE staining in the sham group showed that the spinal cord structure was intact and the boundaries between the gray and white matter could be clearly distinguished. The nuclei were normal, showing no inflammatory cell infiltration, hemorrhage, necrosis, and/or tissue edema. The spinal cord structure was disordered in the SCI group, with a wide range of lesion cavities; some neurons were dissolved and numerous inflammatory cells could be observed. The inflammatory cell infiltration and spinal cord necrosis cavity were reduced in the SCFA group (Figs. 1e and 1f).

In order to evaluate the neuroprotective effect of SCFAs after SCI, the number of surviving motor neurons was determined by Nissl staining 21 d after treatment. In the SCI group, the number of motor neurons significantly reduced, the nucleus showed shrinkage, and the protrusions around neuron cells were reduced. After treatment with SCFAs, the number of motor neurons was increased, and the color of Nissl bodies was deeper, indicating that SCFAs had a good neuroprotective effect after SCI in rats (Figs. 1e and 1g).

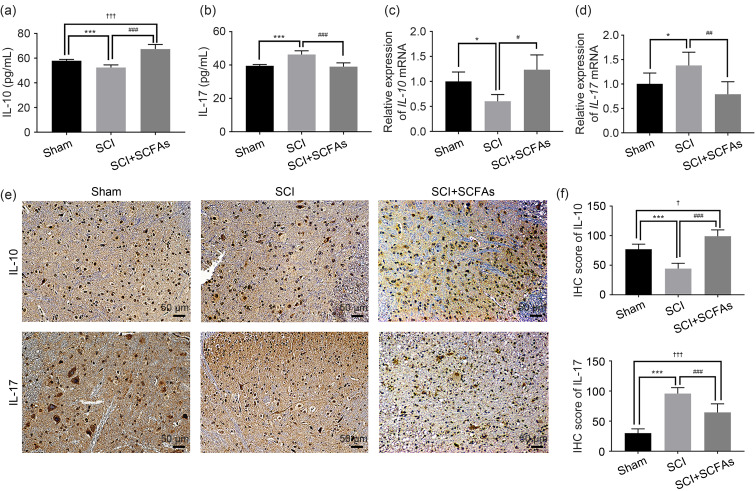

3.2. Relationship between SCFA-induced alleviation of neuroinflammation and IL-10

In order to explore the effect of SCFAs on inflammation in SCI, the expression levels of IL-10 and IL-17 in the spinal cord tissue were detected by ELISA, qPCR, and immunohistochemistry. ELISA and qPCR showed that the expression of IL-10 varied significantly among different groups. The expression of IL-10 was decreased in the SCI group and increased with SCFA treatment after SCI (Figs. 2a and 2c). Meanwhile, the expression of IL-17 was increased in the SCI group and decreased with SCFA treatment after SCI (Figs. 2b and 2d). Furthermore, the immunostaining results of IL-10 and IL-17 in the spinal cord tissues at 21 d after SCI induction were consistent with the ELISA and qPCR results (Figs. 2e and 2f), which indicated that the SCFA-induced alleviation of neuroinflammation after SCI likely depends on IL-10.

Fig. 2. Expression of IL-10 and IL-17 in the spinal cord after SCFA treatment. (a, b) The expression of IL-10 and IL-17 was detected by ELISA. (c, d) The relative expression of IL-10 and IL-17 mRNAs was detected by qPCR. (e) IL-10 and IL-17 were stained by IHC in the spinal cord. (f) The IHC scores of IL-10 and IL-17 of the spinal cord. Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), n=5. * P<0.05, *** P<0.001, SCI vs. sham; # P<0.05, ## P<0.01, ### P<0.001, SCI vs. SCI+SCFAs; † P<0.05, ††† P<0.001, SCI+SCFAs vs. sham. IL: interleukin; SCI: spinal cord injury; SCFA: short-chain fatty acid; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; mRNA: messenger RNA; qPCR: real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction; IHC: immunohistochemistry.

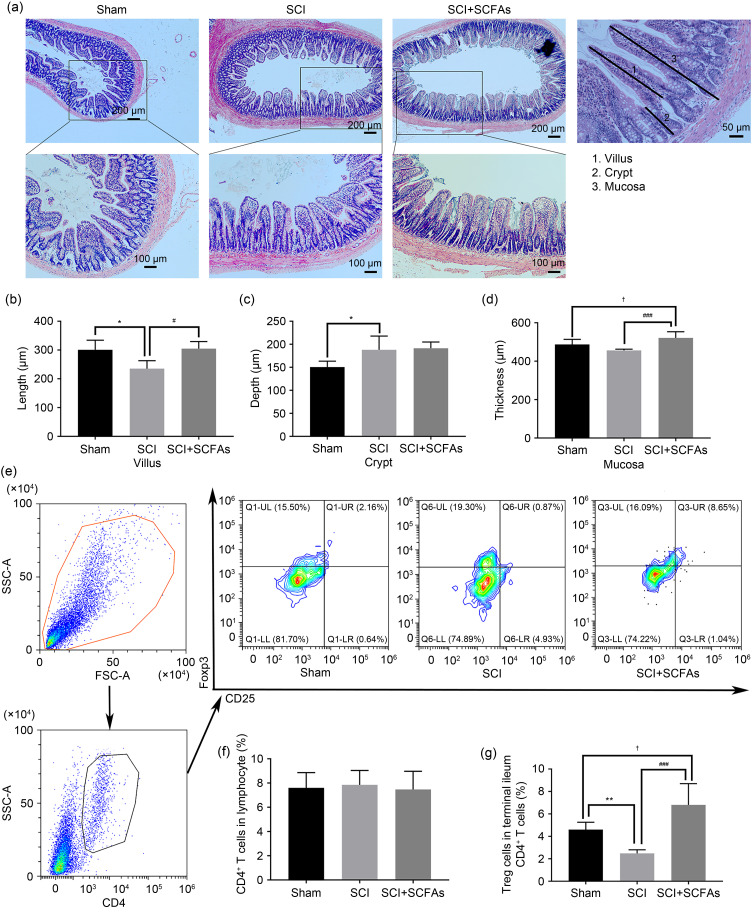

3.3. Effects of SCFAs on gut homeostasis and intestinal T cell differentiation

In order to explore the effect of oral SCFAs on intestinal barrier dysfunction after SCI, we assessed the villus height, crypt depth, and the mucosal thickness of ileum. In the sham group, the intestinal mucosa epithelial structure was intact, the mucosal glands were orderly and regular, and the villi were intact and slender without obvious hyperemia, edema, or inflammatory cell infiltration. However, in the SCI group, the integrity of intestinal mucosa was damaged, the intestinal villi were shortened and blunt, the gap between the top of villi was enlarged, and the infiltration of inflammatory cells was noted. The intestinal villus height was decreased and the crypt depth was enlarged with statistically significant differences. After 21 d of continuous treatment with SCFAs, villus height and mucosal thickness in the SCFA group were improved compared with the SCI group ( P<0.05). At the same time, the depth of crypts did not decrease significantly ( P>0.05) ( Figs. 3a‒3d).

Fig. 3. Effects of SCFAs on the gut homeostasis and intestinal T cells differentiation. (a) Assessment of terminal ileum homeostasis of different groups using hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. (b) The length of villus. (c) The depth of crypt. (d) The thickness of mucosa. (e) Flow cytometry was used to identify Treg cells in the small intestinal lamina propria of different groups. (f) The ratio of small intestinal lamina propria CD4 + T cells in the lymphocytes of different groups. (g) The ratio of small intestinal lamina propria Treg cells in CD4 + T cells of different groups. Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), n=5. * P<0.05, SCI vs. sham; # P<0.05, ### P<0.001, SCI vs. SCI+SCFAs; † P<0.05, SCI+SCFAs vs. sham. SCI: spinal cord injury; SCFAs: short-chain fatty acids; SSC-A: side scatter-area; FSC-A: forward scatter-area; Treg: regulatory T; CD4: cluster of differentiation 4.

In the gut, bacterial metabolites can be translocated from the intestinal lumen to the lamina propria, regulating the differentiation of T cells into different subgroups, which in turn affects host immunity. To determine the effect of oral administration of SCFAs on intestinal T cell differentiation, we first analyzed lymphocytes of the small intestinal lamina propria of SCI rats treated with SCFAs. The flow cytometry analysis revealed no statistical difference in the frequency of CD4 + T cells of the small intestine lamina propria between the groups. However, we found that treatment with SCFAs significantly increased the abundance of Treg cells, as compared to the SCI and sham groups ( Figs. 3e–3g). These data suggested that SCFAs promote the differentiation of T cells in the small intestinal lamina propria towards an anti-inflammatory state.

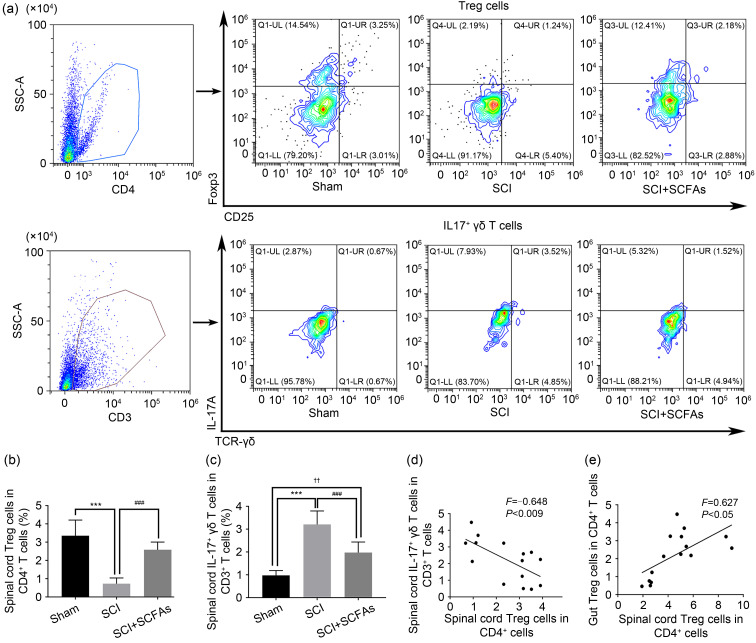

3.4. Effects of oral SCFAs on the frequencies of Treg cells and IL-17 + γδ T cells in the spinal cord

Next, we investigated whether SCFAs can alter the frequency of Treg cells in the spinal cord after SCI. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that, compared to the SCI group, the SCFA-treated group showed a significantly enhanced frequency of Treg cells in the spinal cord (Figs. 4a and 4b). We explored whether SCFAs altered IL-17 + γδ T cells in the spinal cord after SCI. Twenty-one days after SCI, the frequency of the spinal cord IL-17 + γδ T cells in CD3 + T cells was significantly increased compared with the sham group, and the frequency of IL-17 + γδ T cells was lower in SCI rats treated with SCFAs than in the SCI group (Figs. 4a and 4c). Moreover, Pearson’s correlation analysis showed that the frequency of Treg cells was correlated between the intestine and the spinal cord. At the same time, there was a certain association between the two groups of cells, with an increase in Treg cells suppressing the frequency of IL-17 + γδ T cells (Figs. 4d and 4e).

Fig. 4. Effects of SCFAs on the frequencies of Treg cells and IL-17 + γδ T cells in the spinal cord. (a) Representative flow cytometry plots to identify Treg cells and IL-17 + γδ T cells in the spinal cord of different groups. (b, c) The ratios of spinal cord Treg cells in CD4 + cells and IL-17 + γδ T cells in CD3 + cells of different groups. (d) Correlations between Treg cells and IL-17 + γδ T cells in the spinal cord. A negative correlation was found between Treg cells and IL-17 + γδ T cells. (e) Correlations of Treg cells between spinal cord and intestine. There was a positive correlation of Treg cells between spinal cord and intestine. Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), n=5. *** P<0.001, SCI vs. sham; ### P<0.001, SCI vs. SCI+SCFAs; †† P<0.01, SCI+SCFAs vs. sham. Treg: regulatory T; SCI: spinal cord injury; SCFAs: short-chain fatty acids; SSC-A: side scatter-area; IL: interleukin; CD: cluster of differentiation; TCR: T cell receptor.

3.5. Migration of Treg cells from the gut to the spinal cord region after SCI

In order to study Treg cell migration from the gut to the spinal cord region, we microinjected fluorescently labeled Treg cells into the Peyer’s patches in the gut of mice with SCI ( Benakis et al., 2016) ( Fig. 5a). We then performed flow cytometry analysis of the gut-derived Treg cells, and confirmed that the gut-derived Treg cells migrated through the Peyer’s patches to the spinal cord without potentially spreading through the blood circulatory system ( Figs. 5b‒5d). Here, we detected the infiltration of Treg cells around the injury, which migrated from the Peyer’s patches to the spinal cord ( Fig. 5d). These results clearly showed that in SCI, Treg cells migrate from the intestine to the damaged spinal cord region.

Fig. 5. Migration of Treg cells from the gut to the spinal cord region after SCI and the effect on the γδ T cells. (a) Experimental design of gut-derived Treg cell migration following SCI in rats. On the second day after SCI, fluorescently labeled Treg cells were injected into the Peyer's patches, and the labeled Treg cells in the spinal cord and blood were detected 24 h later. (b) Flow cytometric detection of labeled Treg cells in the spinal cord and blood 24 h after enteral microinjection of Peyer's patch microinjection. (c) Treg cells stained with CFSE. (d) Fluorescently labeled Treg cells from the gut were found in the SCI area and displayed in the horizontal sections of the spinal cord. (e) CCK-8 assays were used to detect the effects of varying SCFA concentrations (0‒2 mmol/L) on the proliferation of Treg cells. (f) The relative expression of IL-10 mRNA in Treg cells was detected by qPCR. (g) CCK-8 assays were used to measure the effects of varying IL-10 concentrations (0‒20 ng/mL) on the proliferation of γδ T cells. Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), n=5. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001. Treg: regulatory T; SCI: spinal cord injury; CFSE: carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl amino ester; DAPI: 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; SCFA: short-chain fatty acid; IL: interleukin; CCK-8: cell counting kit-8; mRNA: messenger RNA; qPCR: real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

3.6. Effects of SCFAs on the proliferation and viability of γδ T cells

In order to investigate the effect of SCFAs on the IL-10 secretion of Treg cells, we treated Treg cells with mixed SCFAs at a concentration of 0.5 mmol/L for 24 h ( Fig. 5e). The expression of IL-10 detected by qPCR increased with SCFA treatment ( Fig. 5f). Then, the γδ T cells were treated with IL-10 for 24 h. CCK-8 assay revealed that IL-10 suppressed the proliferation and viability of γδ T cells ( Fig. 5g).

4. Discussion

SCI can have severe consequences for patients. Certain compounds such as betulinic acid and cannabinoids are gaining attention in the treatment of SCI ( Michel et al., 2021). As the largest microbiota in the body, intestinal flora and their metabolites are emerging drug candidates in SCI. It has been demonstrated that FMT can improve motility and gastrointestinal function in SCI mice ( Jing et al., 2021b). In this study, we determined that exogenous administration of SCFAs can regulate Treg cells in the gut and promote their secretion of IL-10. This in turn alters the balance of Treg and IL-17 + γδ T cells in the spinal cord, inhibits the inflammatory response, and promotes the motor function in SCI rats. In addition, we demonstrated that Treg cells migrate from the intestinal tract to the damaged region in SCI, which provides a new direction for understanding the interaction between the gut and the spinal cord.

Inflammatory immune imbalance plays a key role in a series of important processes such as secondary injury and nerve regeneration after SCI ( Michel et al., 2021). Imbalance and disorders of the intestinal flora after SCI result in a decrease in SCFA metabolizing flora ( Gungor et al., 2016; Kigerl et al., 2018; O'Connor et al., 2018; Wallace et al., 2019; Jogia and Ruitenberg, 2020; Jing et al., 2021a; Yu et al., 2021; Valido et al., 2022). Recent studies have demonstrated that SCFAs play an important role in stabilizing the immune responses, modulating the central nervous system, and maintaining an anti/pro-inflammatory balance, which act as a bridge between the gut microbiota and the immune system ( Kigerl et al., 2016, 2018; Ratajczak et al., 2019). Our results showed that exogenously administered oral SCFAs into SCI rats exert a beneficial effect on behavioral recovery. After 21 d of treatment with SCFAs, the BBB scores were significantly increased, the regularity index was improved, and the BOS value was decreased, suggesting that SCFAs have a certain effect on the promotion of motor function recovery. The results of tissue staining revealed that local inflammatory infiltration was inhibited, cell morphology was regular, and the numbers of motor neuron cells and Nissl bodies were increased after SCFA treatment, which indicated that SCFAs can alleviate inflammation and improve motor function to some extent.

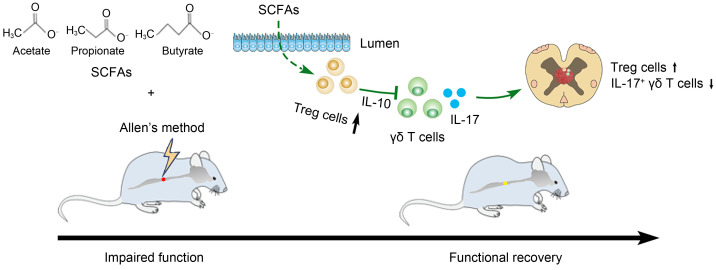

Treg cells are a set of regulatory immune cells that block the immune response owing to their anti-inflammatory activity. After the initiation and completion of immune response, Treg cells prevent immune cells from continuing to attack the body, thereby avoiding excessive inflammation and promoting healing and repair. In models of stroke and immune-mediated neurodegeneration, Treg cells have been found to inhibit inflammatory response and exert protective effects ( Benakis et al., 2016; Stephenson et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2022). Treg cells can reduce the infiltration of inflammatory factors by secreting anti-inflammatory factor IL-10, which is key to inhibiting the inflammatory response and producing an immunosuppressive effect ( Park et al., 2015). γδ T cells are mainly distributed in epithelial tissues, especially the intestinal mucosa. Although their number is small, their role in immunity cannot be underestimated. Their activation process is faster than that of traditional T cells and secrete the important regulatory molecule IL-17, which is a powerful early inflammatory factor in the disease. In addition, γδ T cells can activate B/dendritic cell (DC)/αβ T/natural killer (NK) cells in a variety of ways to promote inflammation. Studies have shown that γδ T cells and IL-17 are related to SCI, and γδ T cells can be recruited to SCI sites through C-C motif chemokine ligand 2/C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCL2/CCR2) signal transduction, thereby promoting inflammatory responses and aggravating neurological damage ( Hill et al., 2011; He et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2021). In our study, we found that the frequency of IL-17 + γδ T cells changed in the spinal cord of rats after SCFA treatment; hence, IL-17 + γδ T cells were identified as potentially effector T cells. Similar to our results, another study demonstrated that SCFAs could reduce ocular inflammation by altering Treg cells in the gut and distal tissues ( Nakamura et al., 2017). SCFAs have pleiotropic properties in the nervous system, which can act on microglia and neurons ( Silva et al., 2020). Microglia are widely distributed immune cells in the central nervous system and play an important role in secondary SCI. Research has shown that acetate can attenuate the production of nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in microglia to alleviate neuroinflammatory response ( Moriyama et al., 2021). Butyrate attenuates the expression of proinflammatory factors in microglia and performs an anti-inflammatory function, so SCFAs can inhibit microglia inflammatory response to improve SCI ( Huuskonen et al., 2004; Patnala et al., 2017; Matt et al., 2018). In this study, we found that SCFAs can regulate Treg cells in the gut and promote their secretion of IL-10, which in turn affects the balance of Treg and IL-17 + γδ T cells in the spinal cord, thus inhibiting the inflammatory response and promoting motor function in SCI rats ( Fig. 6). This may be another mechanism of SCFAs promoting SCI repair.

Fig. 6. Effects of SCFAs on the inflammatory response and the recovery of motor function in rats after SCI through regulation of Treg/IL-17 + γδ T cells. SCFAs promote gut homeostasis, induce intestinal T cells to shift toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype, promote Treg cells to secrete IL-10, and migrate from the gut to the spinal cord region after SCI to affect Treg cells and IL-17 + γδ T cells in the spinal cord. This exerts an inhibitory effect on the inflammatory response and promotes motor function in SCI rats. SCI: spinal cord injury; IL: interleukin; Treg: regulatory T; SCFAs: short-chain fatty acids.

Recently, increasing research has focused on the effects of gut microbiota metabolites on the gut environment and distant target organs in the body. However, the exact mechanism linking the intestine immune-phenotypic changes with the target tissues away from the intestine has been elusive. In vivo cell tracking experiments determined that some of the Treg cells invading the spinal cord after injury originated from the gut. For example, one study showed that T cells from the intestine can migrate to the leptomeninges after an ischemic stroke ( Benakis et al., 2016). In this work, we observed that inflammatory cells entered the injured spinal cord, which might be caused by compromised spinal meninges after trauma.

The spinal cord, gut, and immune system are all interconnected, and a problem in any of these can cause the imbalance of homeostasis and result in disease. The recovery of patients with spinal cord injuries will undoubtedly accelerate if there is an effective interplay among the spinal cord, gut, and immune system. Oral probiotics or FMT has been used to treat rats with SCI ( Kigerl et al., 2016; Jing et al., 2021b). A large proportion of oral probiotics fail to reach the gut and exert their curative effects because of the killing effect of digestive juice. However, oral SCFAs can counter the effects of these factors and may be a relatively effective choice ( Bezkorovainy, 2001; Nakamura et al., 2017). Meanwhile, SCFA supplementation has certain risks, which requires further elucidation. For example, high levels of SCFAs were found to cause inflammation in a kidney disease model and increase the risk of icteric hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in wild-type mice ( Park et al., 2016). For SCFAs to be used to treat clinically relevant diseases and avoid potentially detrimental side effects, a deeper knowledge of the interactions between microbial metabolites and host is required.

Our study has some limitations. First, the relationship between Treg and IL-17 + γδ T cells and the specific mechanism of action need to be further explored. Second, due to the experimental design, cells were labeled in vitro, and the changes in the number of cells that migrated from the intestinal tract to the spinal cord after treatment with SCFAs could not be directly demonstrated. Third, a mixture of SCFAs was used in the study; hence, the effects of single SCFAs on SCI rats must be further explored. Despite the above limitations, this study successfully performed the initial therapeutic assessment of a mixture of SCFAs in an in vivo SCI rat model. The findings will provide a valuable theoretical foundation for the treatment of SCI with SCFAs. It is worth mentioning that most previous studies employed millimolar concentrations to study the biological effects of SCFAs, which may be much higher than the physiological concentrations of SCFAs in humans.

In summary, we have demonstrated the potential of oral SCFAs in the treatment of SCI in a rat model, where the motor function was significantly improved after SCFA treatment. Hence, our tentative conclusion is that SCFAs can regulate Treg cells in the gut and promote their secretion of IL-10, affecting the balance of Treg and IL-17 + γδ T cells in the spinal cord, which in turn inhibits the inflammatory response and promotes the motor function of SCI rats. We suggest that the intimate relationship among the gut, spinal cord, and immune cells, that is, the “gut‒spinal cord‒immune” axis may be one of the vital mechanisms regulating neural repair after SCI.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82060399) and the Guangxi Medical High-level Key Talents Training “139” Program Training Project (No. [2020]15), China.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82060399) and the Guangxi Medical High-level Key Talents Training “139” Program Training Project (No. [2020]15), China.

Author contributions

Shaohui ZONG and Gaofeng ZENG performed the study concept and design. Pan LIU, Mingfu LIU, and Deshuang XI performed the experimental research and data analysis. Yiguang BAI established animal models. Ruixin MA and Yaoming MO contributed to the data analysis, writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript, and therefore, have full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and security of the data.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Pan LIU, Mingfu LIU, Deshuang XI, Yiguang BAI, Ruixin MA, Yaomin MO, Gaofeng ZENG, and Shaohui ZONG declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

All experimental procedures adhered to the Guidelines for Animal Treatment of Guangxi Medical University (approval No. 201810042) and were performed according to the principles and procedures of the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

References

- Allen AR, 1911. Surgery of experimental lesion of spinal cord equivalent to crush injury of fracture dislocation of spinal column: a preliminary report. JAMA, LVII( 11): 878- 880. 10.1001/jama.1911.04260090100008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC, 1995. A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J Neurotrauma, 12( 1): 1- 21. 10.1089/neu.1995.12.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC, et al. , 1996. Mascis evaluation of open field locomotor scores: effects of experience and teamwork on reliability. J Neurotrauma, 13( 7): 343- 359. 10.1089/neu.1996.13.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzocchi G, Turroni S, Bulzamini MC, et al. , 2021. Changes in gut microbiota in the acute phase after spinal cord injury correlate with severity of the lesion. Sci Rep, 11: 12743. 10.1038/s41598-021-92027-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benakis C, Brea D, Caballero S, et al. , 2016. Commensal microbiota affects ischemic stroke outcome by regulating intestinal γδ T cells. Nat Med, 22( 5): 516- 523. 10.1038/nm.4068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezkorovainy A, 2001. Probiotics: determinants of survival and growth in the gut. Am J Clin Nutr, 73( 2): 399S- 405S. 10.1093/ajcn/73.2.399s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervi AL, Lukewich MK, Lomax AE, 2014. Neural regulation of gastrointestinal inflammation: role of the sympathetic nervous system. Auton Neurosci, 182: 83- 88. 10.1016/j.autneu.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd W, Motwani K, Small C, et al. , 2022. Spinal cord injury and neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction: what do we know and where are we going? J Mens Health, 18( 1): 24. 10.31083/j.jomh180102435106100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eli I, Lerner DP, Ghogawala Z, 2021. Acute traumatic spinal cord injury. Neurol Clin, 39( 2): 471- 488. 10.1016/j.ncl.2021.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira TM, Leonel AJ, Melo MA, et al. , 2012. Oral supplementation of butyrate reduces mucositis and intestinal permeability associated with 5-fluorouracil administration. Lipids, 47( 7): 669- 678. 10.1007/s11745-012-3680-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gungor B, Adiguzel E, Gursel I, et al. , 2016. Intestinal microbiota in patients with spinal cord injury. PLoS ONE, 11( 1): e0145878. 10.1371/journal.pone.0145878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Zhao J, Peng X, et al. , 2017. Molecular mechanism of miR-136-5p targeting NF-κB/A20 in the IL-17-mediated inflammatory response after spinal cord injury. Cell Physiol Biochem, 44( 3): 1224- 1241. 10.1159/000485452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill F, Kim CF, Gorrie CA, et al. , 2011. Interleukin-17 deficiency improves locomotor recovery and tissue sparing after spinal cord contusion injury in mice. Neurosci Lett, 487( 3): 363- 367. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.10.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R, Liu P, Bai YG, et al. , 2022. Changes in the gut microbiota of osteoporosis patients based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci B (Biomed & Biotechnol), 23( 12): 1002- 1013. 10.1631/jzus.B2200344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huuskonen J, Suuronen T, Nuutinen T, et al. , 2004. Regulation of microglial inflammatory response by sodium butyrate and short-chain fatty acids. Br J Pharmacol, 141( 5): 874- 880. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing YL, Yu Y, Bai F, et al. , 2021a. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on neurological restoration in a spinal cord injury mouse model: involvement of brain-gut axis. Microbiome, 9: 59. 10.1186/s40168-021-01007-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing YL, Bai F, Yu Y, 2021b. Spinal cord injury and gut microbiota: a review. Life Sci, 266: 118865. 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jogia T, Ruitenberg MJ, 2020. Traumatic spinal cord injury and the gut microbiota: current insights and future challenges. Front Immunol, 11: 704. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kigerl KA, Hall JCE, Wang LL, et al. , 2016. Gut dysbiosis impairs recovery after spinal cord injury. J Exp Med, 213( 12): 2603- 2620. 10.1084/jem.20151345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kigerl KA, Mostacada K, Popovich PG, 2018. Gut microbiota are disease-modifying factors after traumatic spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics, 15( 1): 60- 67. 10.1007/s13311-017-0583-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane G, Gracely A, Bassis C, et al. , 2022. Distinguishing features of the urinary bacterial microbiome in patients with neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. J Urol, 207( 3): 627- 634. 10.1097/JU.0000000000002274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YT, Liu HY, Yang K, et al. , 2022. A comprehensive update: gastrointestinal microflora, gastric cancer and gastric premalignant condition, and intervention by traditional Chinese medicine. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci B (Biomed & Biotechnol), 23( 1): 1- 18. 10.1631/jzus.B2100182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas S, Omata Y, Hofmann J, et al. , 2018. Short-chain fatty acids regulate systemic bone mass and protect from pathological bone loss. Nat Commun, 9: 55. 10.1038/s41467-017-02490-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matt SM, Allen JM, Lawson MA, et al. , 2018. Butyrate and dietary soluble fiber improve neuroinflammation associated with aging in mice. Front Immunol, 9: 1832. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel M, Goldman M, Peart R, et al. , 2021. Spinal cord injury: a review of current management considerations and emerging treatments. J Neurol Sci Res, 2( 2): 14. 36037050 [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama M, Nishimura Y, Kurebayashi R, et al. , 2021. Acetate suppresses lipopolysaccharide-stimulated nitric oxide production in primary rat microglia but not in BV-2 microglia cells. Curr Mol Pharmacol, 14( 2): 253- 260. 10.2174/1874467213666200420101048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura YK, Janowitz C, Metea C, et al. , 2017. Short chain fatty acids ameliorate immune-mediated uveitis partially by altering migration of lymphocytes from the intestine. Sci Rep, 7: 11745. 10.1038/s41598-017-12163-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor G, Jeffrey E, Madorma D, et al. , 2018. Investigation of microbiota alterations and intestinal inflammation post-spinal cord injury in rat model. J Neurotrauma, 35( 18): 2159- 2166. 10.1089/neu.2017.5349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Kim M, Kang SG, et al. , 2015. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR-S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol, 8( 1): 80- 93. 10.1038/mi.2014.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Goergen CJ, Hogenesch H, et al. , 2016. Chronically elevated levels of short-chain fatty acids induce T cell-mediated ureteritis and hydronephrosis. J Immunol, 196( 5): 2388- 2400. 10.4049/jimmunol.1502046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patnala R, Arumugam TV, Gupta N, et al. , 2017. HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate-mediated epigenetic regulation enhances neuroprotective function of microglia during ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol, 54( 8): 6391- 6411. 10.1007/s12035-016-0149-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos MG, Bambirra EA, Cara DC, et al. , 1997. Oral administration of short-chain fatty acids reduces the intestinal mucositis caused by treatment with Ara-C in mice fed commercial or elemental diets. Nutr Cancer, 28( 2): 212- 217. 10.1080/01635589709514577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak W, Ryl A, Mizerski A, et al. , 2019. Immunomodulatory potential of gut microbiome-derived short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Acta Biochim Pol, 66( 1): 1- 12. 10.18388/abp.2018_2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva YP, Bernardi A, Frozza RL, 2020. The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-brain communication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 11: 25. 10.3389/fendo.2020.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson J, Nutma E, van der Valk P, et al. , 2018. Inflammation in CNS neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology, 154( 2): 204- 219. 10.1111/imm.12922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun GD, Yang SX, Cao GC, et al. , 2018. γδ T cells provide the early source of IFN-γ to aggravate lesions in spinal cord injury. J Exp Med, 215( 2): 521- 535. 10.1084/jem.20170686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate DG, Forchheimer M, Rodriguez G, et al. , 2016. Risk factors associated with neurogenic bowel complications and dysfunction in spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 97( 10): 1679- 1686. 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valido E, Bertolo A, Frankl GP, et al. , 2022. Systematic review of the changes in the microbiome following spinal cord injury: animal and human evidence. Spinal Cord, 60( 4): 288- 300. 10.1038/s41393-021-00737-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DJ, Sayre NL, Patterson TT, et al. , 2019. Spinal cord injury and the human microbiome: beyond the brain-gut axis. Neurosurg Focus, 46( 3): E11. 10.3171/2018.12.FOCUS18206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Zhang F, Chang MM, et al. , 2021. Recruitment of γδ T cells to the lesion via the CCL2/CCR2 signaling after spinal cord injury. J Neuroinflammation, 18: 64. 10.1186/s12974-021-02115-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu BB, Qiu HD, Cheng SP, et al. , 2021. Profile of gut microbiota in patients with traumatic thoracic spinal cord injury and its clinical implications: a case-control study in a rehabilitation setting. Bioengineered, 12( 1): 4489- 4499. 10.1080/21655979.2021.1955543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JX, Xie QS, Kong WM, et al. , 2020. Short-chain fatty acids oppositely altered expressions and functions of intestinal cytochrome P4503A and P-glycoprotein and affected pharmacokinetics of verapamil following oral administration to rats. J Pharm Pharmacol, 72( 3): 448- 460. 10.1111/jphp.13215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]