Abstract

RecQ helicase family proteins play vital roles in maintaining genome stability, including DNA replication, recombination, and DNA repair. In human cells, there are five RecQ helicases: RECQL1, Bloom syndrome (BLM), Werner syndrome (WRN), RECQL4, and RECQL5. Dysfunction or absence of RecQ proteins is associated with genetic disorders, tumorigenesis, premature aging, and neurodegeneration. The biochemical and biological roles of RecQ helicases are rather well established, however, there is no systematic study comparing the behavioral changes amongst various RecQ-deficient mice including consequences of exposure to DNA damage. Here, we investigated the effects of ionizing irradiation (IR) on three RecQ-deficient mouse models (RecQ1, WRN and RecQ4). We find abnormal cognitive behavior in RecQ-deficient mice in the absence of IR. Interestingly, RecQ dysfunction impairs social ability and induces depressive-like behavior in mice after a single exposure to IR, suggesting that RecQ proteins play roles in mood and cognition behavior. Further, transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses revealed significant alterations in RecQ-deficient mice, especially after IR exposure. In particular, pathways related to neuronal and microglial functions, DNA damage repair, cell cycle, and reactive oxygen responses were downregulated in the RecQ4 and WRN mice. In addition, increased DNA damage responses were found in RecQ-deficient mice. Notably, two genes, Aldolase Fructose-Bisphosphate B (Aldob) and NADPH Oxidase 4 (Nox4), were differentially expressed in RecQ-deficient mice. Our findings suggest that RecQ dysfunction contributes to social and depressive-like behaviors in mice, and that aldolase activity may be associated with these changes, representing a potential therapeutic target.

Keywords: RecQ helicases, DNA damage, WRN, depressive-like behavior, Aldolase activity

Introduction

RecQ DNA helicases are critical for genome maintenance (Croteau et al., 2014). This family of proteins includes five human genes, RECQL1, BLM, WRN, RECQL4 and RECQL5 (Opresko et al., 2004). All of these are implicated in human disease: BLM is mutated in Bloom’s syndrome (BS), WRN is mutated in Werner’s syndrome (WS), RECQL4 is mutated in Rothmund–Thomson syndrome (RTS), RECQL1 in RECON syndrome, and RECQL5 in different conditions (Abu-Libdeh et al., 2022; Opresko et al., 2004; Tavera-Tapia et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2016). Patients with BS are prone to many types of cancer, with an average age of onset of 24 years (Chu and Hickson, 2009). WS patients are particularly prone to sarcoma, premature aging, and age-related diseases (Chu and Hickson, 2009). RTS patients have characteristic skin rashes, poikiloderma, osteosarcoma, and many features of premature aging (Chu and Hickson, 2009). RECON patients have progeroid features, short stature, and skin photosensitivity (Abu-Libdeh et al., 2022). RECQL5 is associated with cancer and early myocardial infarcts (Tavera-Tapia et al., 2019).

RecQ helicases play important roles in DNA repair, recombination, and replication, either directly or through functional interactions with proteins that regulate or play key roles in these pathways (Croteau et al., 2014). RecQ helicases also play direct roles in many aspects of DNA metabolic pathways (Annus et al., 2022; Tadokoro et al., 2013). The biological importance of RecQ helicases is well established; however, it remains unclear whether they can be exploited as therapeutic targets for cancer, or whether treatments can be developed to ameliorate or prevent diseases in patients carrying the RecQ mutations.

Knockout of RECQ1 in mice or knockdown of its expression in human cells result in chromosomal instability, increased load of DNA damage and heightened sensitivity to ionizing radiation (IR) (Parvathaneni et al., 2013). Deficiency of the Caenorhabditis elegans RecQ5 homologue reduces life span by 37% and increases sensitivity to IR (Lebel et al., 2001). Transgenic mice expressing a mutant WRN gene encoding a defective helicase showed no premature aging phenotypes characteristic of WS (Wang et al., 2000). However, mice have long telomeres and when Wrn-deficient mice were bred to mice with telomere dysfunction, they developed premature aging features (Pignolo et al., 2008). Lack of RECQL4 in mice is lethal (Ng et al., 2015). RECQL4 is the only RecQ helicase reported to localize both to the nucleus and to mitochondria and it is critical for maintenance of the mitochondrial genome (Croteau et al., 2012). In addition, mice with RECQL4 depleted specifically from their bone cells have shortened bones and a reduced rate of bone formation (Ng et al., 2015). Therefore, RECQL4 is critical for normal bone development. Our former study also identified sparser tail hair and fewer blood cells in Recql4-deficient mice accompanied with increased senescence in tail hair follicles and in bone marrow cells (Lu et al., 2014a). RECQL5 knockout mice are cancer prone and show increased chromosomal instability (Popuri et al., 2013). RECQL1 deficient mice appear normal, but RECQL1 deficient cells are hypersensitive to IR and have chromosomal instability in vitro (Sharma et al., 2007). Moreover, depletion of WRN, BLM, or RECQL4 increases cellular DNA damage, leading to a senescence-like phenotype in primary fibroblasts and in mice (Lombard et al., 2000; Lu et al., 2014b; Szekely et al., 2005; Tivey et al., 2013).

The complex biology of RecQ helicases presents a significant research challenge and there are many biological studies in RecQ mice relating to genome instability. It is reported that there are increased DNA breaks (Stott et al., 2021) and DNA damage is involved in neural plasticity and cognitive impairment (Konopka and Atkin, 2022). Given the important role of RecQ genes in DNA damage and repair, however, very few behavioral tests have been reported. There has been no systematic study comparing cognitive behavior, social interactions, depression, or other behaviors in RecQ-deficient mice, and it is largely unknown how they respond after IR stress. This study investigates behavioral changes and underlying mechanisms in these mice, with or without IR-induced DNA damage. While it is clearly established that RecQ deficiency is associated with cancer, its relation to neurodegeneration and behavior is much less evident and needs investigation. Since the number of patients with RecQ deficient diseases are so small, it is difficult to get thorough insights into their clinical phenotypes and the frequency of the clinical features. Studies in mice can help clarify conditions that should be further explored in humans and provide a broader picture of the disease phenotype and targets for intervention.

Results

RecQ dysfunction contributes to social and depressive-like behavior in mice with or without irradiation stress.

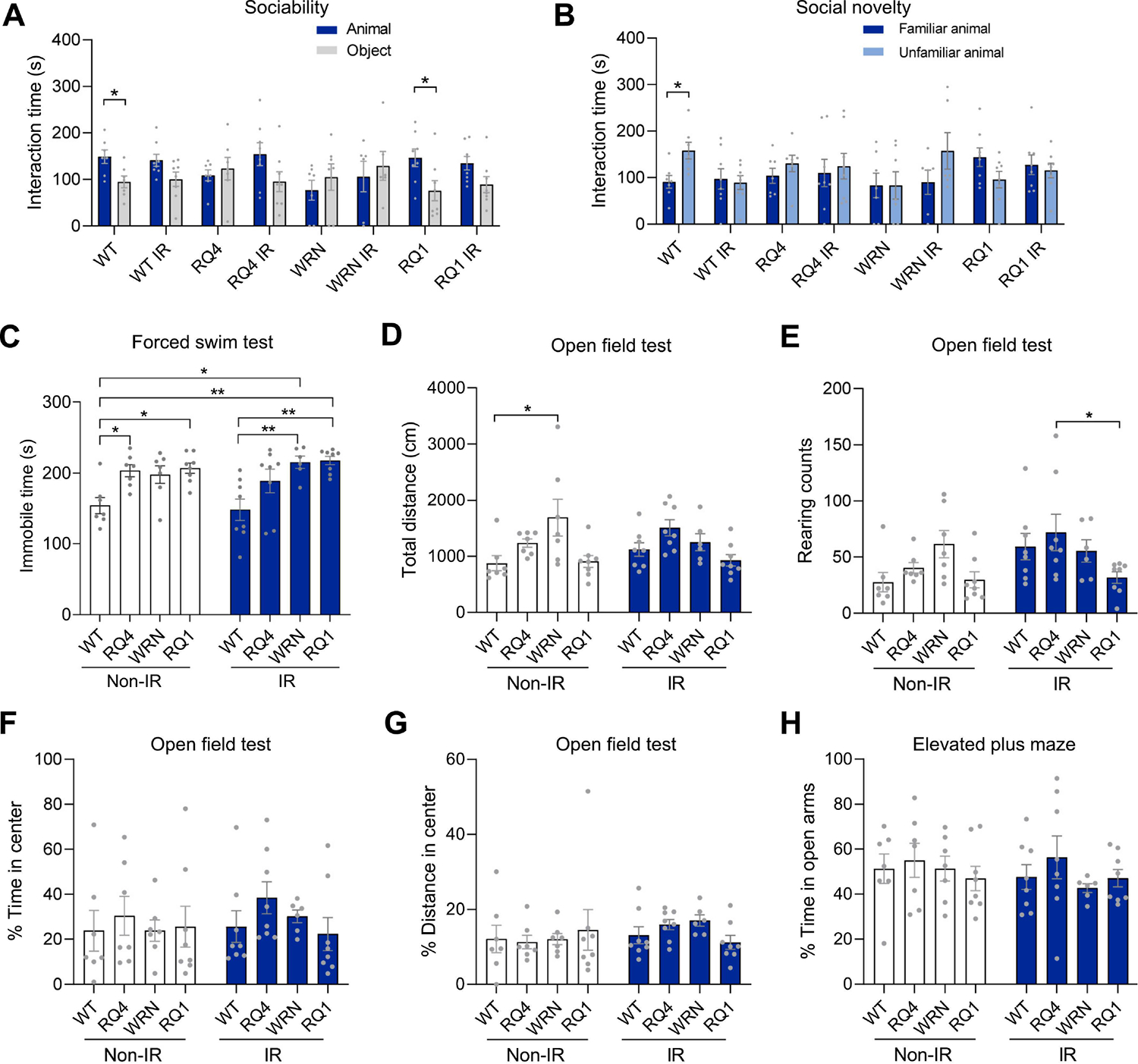

We evaluated behavioral changes of RecQ-deficient mice under normal conditions and after irradiation. In the sociability test, we found that the majority of RecQ-deficient mice, except RQ1, displayed impaired sociability, showing no preference for either the animal or the object, while WT mice could distinguish the animal and the object well and spent more time interacting with the animal target (Figure 1A). However, WT mice treated with IR could not distinguish between mouse and object, and their interaction time with the animal was comparable to their time with the object. RQ4 and Wrn mice, either with or without IR, showed significantly reduced sociability towards the unfamiliar animal compared with WT mice. Interestingly, the sociability of RQ1 mice without IR treatment was intact, but impaired after IR treatment (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. RecQ dysfunction contributes to social and depressive-like behavior in mice with or without irradiation stress.

(A) The sociability in the social behavior test of WT, RQ4 (RQ4), Wrn, RQ1 (RQ1) mice with or without IR. n = 6–8 mice/group. Two-way ANOVA, F (1, 102) = 6.147, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by post hoc uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test.

(B) The social novelty in the social behavior test. n = 6–8 mice/group. Two-way ANOVA, F (7, 102) = 1.485, *p = 0.0437 by post hoc uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test.

(C) The forced swim test. n = 6–8 mice/group. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 51) = 11.62, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by post hoc Tukey.

(D-G) The open field test, including total distance travelled in the area (D), the rearing counts (E), the % time in center (F), and the % of distance in center (G). n = 6–8 mice/group. For D, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 51) = 5.797, *p = 0.0181 by post hoc Tukey. For E, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 51) = 3.114, *p = 0.03 by post hoc Tukey. For F, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 51) = 0.8322. For G, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 51) = 0.1750.

(H) The elevated plus maze, the % time in open arms. n = 6–8 mice/group. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 51) = 0.8509.

Data were shown as mean ± SEM.

In the experiments on social novelty, WT mice clearly distinguished between the familiar and unfamiliar animal. However, all other groups of mice, including IR-treated WT mice, RQ4, Wrn, and RQ1, failed to do so, showing no preference for interaction with the novel intruder. These results indicated that the social novelty of all RecQ mice was defective compared with that of the WT group (Figure 1B).

To evaluate the depression status of mice, we used the forced swim test. Mice in the RQ4 and RQ1 groups showed more immobile time under non-IR treatment conditions, and Wrn and RQ1 groups showed more immobile time after IR exposure, indicating that they exhibited depressive-like behavior (Figure 1C). In the open field test, which evaluates anxiety and locomotion activity (Prut and Belzung, 2003), Wrn mice traveled a longer total distance in the non-IR treatment condition, whereas the other two groups, RecQ and WT mice, were about the same, and less than Wrn. However, after IR treatment, the total distance traveled by RecQ mice in each group was similar to that of WT (Figure 1D). Increased rearing was observed in the RQ4-IR group compared with the RQ1-IR group in the open field test, while there was no significant difference between the other groups (Figure 1E). The time of central entrances and the percent of distance in center among the groups were similar, indicating that there was no difference in anxiety between WT and RecQ mice (Figure 1F–G). The results from the elevated plus maze test showed no significant difference in the time spent in the open arm between the groups (Figure 1H), suggesting no change in anxiety RecQ mice compared with WT. Collectively, these data demonstrated that RecQ dysfunction contributes to social- and depressive-like behaviors in mice.

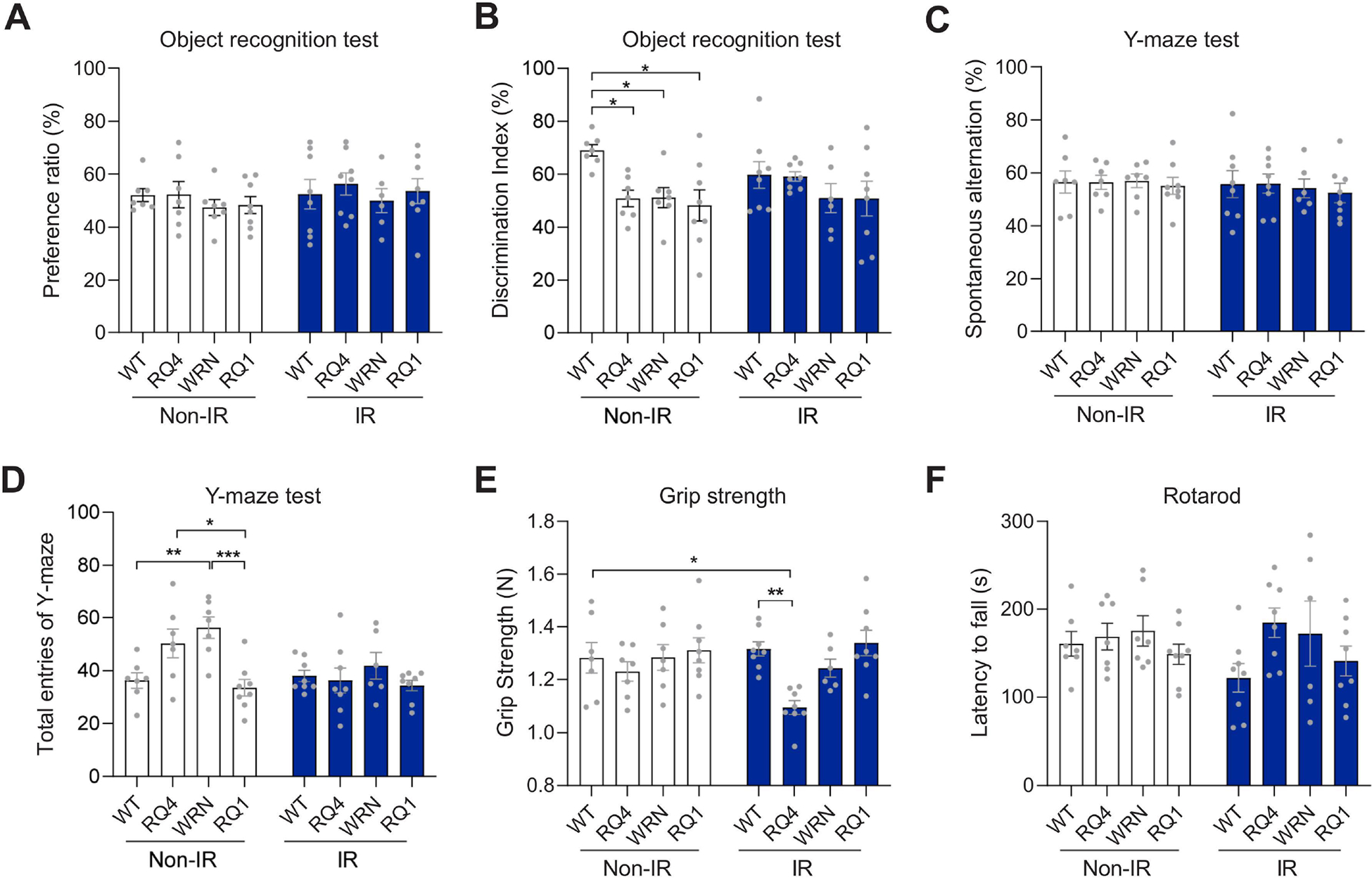

RecQ dysfunction decreased object recognition ability in mice.

In order to examine cognitive and motor functions of RecQ-deficient mice, we performed additional behavioral experiments. In the object recognition habituation phase, there were no significant differences in the preference ratio of each group of mice to the identical objects, indicating that they had no position preference (Figure 2A). In the test phase when mice were exploring the novel object, RQ4, Wrn, and RQ1 in the non-IR groups took significantly less time to explore the novel object than WT mice, indicating impairment of cognition function. However, there were no significant differences in the exploration time of novel objects between groups of mice after IR treatment (Figure 2B). It is noteworthy that the cohort of untreated RQ mice were impaired without IR and the other cohort of IR-treated mice showed no change in performance. In contrast, WT mice showed a preference for novel objects, and this was lost after IR, suggesting that DNA damage can modulate object recognition performance. In another memory-related experiment, the Y-maze test, we detected no difference in spontaneous alternation among all the mouse groups (Figure 2C), indicating no impairment in memory ability. Interestingly, there were some significant changes in the total entries into the Y-maze. The non-IR treatment group of Wrn mice had the highest total entries (Figure 2D), indicating that Wrn mice were more active. This is consistent with the results of total distance travelled in the previously mentioned open field test (Figure 1D). Interestingly, this high level of activity disappeared after IR treatment of the Wrn mice (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. RecQ dysfunction decreased object recognition ability in mice.

(A-B) The object recognition test in WT, RQ4, Wrn and RQ1 mice with or without IR, including the preference ratio in exploring two familiar objects (A) and the discrimination index in exploring one familiar and one novel objects (B). n = 6–8 mice/group. For A, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 51) = 0.5709. For B, Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 51) = 4.216, *p < 0.05 by post hoc Tukey.

(C-D) The spontaneous alternation (C) and the total entries of Y-maze test (D). n = 6–8 mice/group. For C, two-way ANOVA. F (3, 51) = 0.2015. For D, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 51) = 6.017, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by post hoc Tukey.

(E) The grip strength test. n = 6–8 mice/group. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 51) = 5.950, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by post hoc Tukey.

(F) The rotarod test. n = 6–8 mice/group. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 51) = 2.077. Data were shown as mean ± SEM.

We next examined the muscle capacity of the mice. In the grip strength test, there were no significant differences between the groups without IR treatment (Figure 2E). However, after IR, the grip strength of the RQ4 mice declined sharply compared with the WT mice, but not significantly different from RQ4 mice without IR (Figure 2E). In a rotarod test, no significant difference in the motor ability of the mice was detected among all groups with or without IR treatment (Figure 2F). These results indicated that the cognitive function of RQ4, Wrn, and RQ1 mice was impaired without IR, while their spatial memory ability and motor ability were not significantly affected.

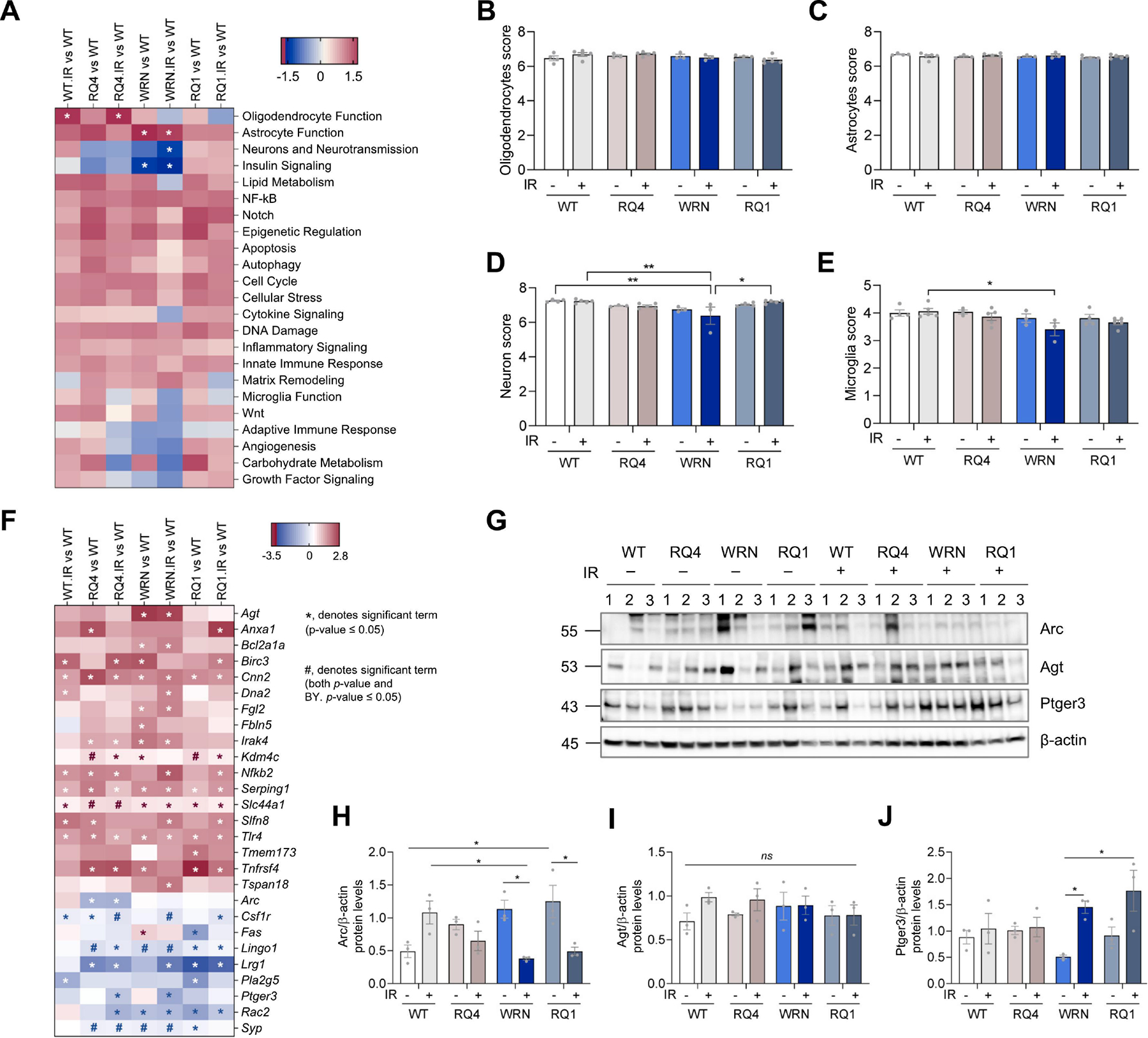

NanoString analysis on prefrontal cortex of RecQ mice with or without irradiation stress

In order to investigate potential mechanisms that might contribute to the behavioral changes in the mice, and to explore pathways and gene changes in each group before and after IR, NanoString gene expression analysis using the neuroinflammation panel was employed (see Methods for details). We found that the statistically significant pathways included oligodendrocyte function, astrocyte function, neurons and neurotransmission, and insulin signaling (Figure 3A). In cell type analysis, oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, neurons, and microglia scores in NanoString were analyzed. The cell type scores were calculated based on cell-type specific gene expression markers using nSolver 4.0 software. Astrocytes and oligodendrocytes scores did not show significant differences between the groups of mice (Figure 3B–C). However, the neuron and microglia scores were significantly decreased in mice in the Wrn+IR group compared with WT+IR mice, while the neuron scores were decreased in the Wrn+IR group when compared to the WT and RQ1+IR groups (Figure 3D–E). An early study found that Wrn mutant mice harbored microglial dysfunction and increased neuronal oxidative stress in the brain (Hui et al., 2018). This may contribute to the Wrn mice being more vulnerable to DNA damage and partly explain why changes were more obvious in Wrn mice after IR treatment.

Figure 3. Nanostring analysis in prefrontal cortex of RecQ mice with or without irradiation stress.

(A) NanoString analysis was done to study the changes in some specific gene panels. Pathway analysis using NanoString from prefrontal cortex tissue of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with or without IR. *denotes significant changes.

(B-E) Cell type score analysis using NanoString, including oligodendrocytes score (B), astrocytes score (C), neuron score (D) and microglia score (E). For B, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 24) = 1.570. For C, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 24) = 0.9203. For D, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 24) = 7.616, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by post hoc Tukey. For E, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 24) = 4.120, *p = 0.0368 by post hoc Tukey.

(F) Gene analysis using NanoString in prefrontal cortex of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with or without IR. *, denotes significant term (p-value ≤ 0.05), #, denotes significant term (both p-value and BY. p-value ≤ 0.05). Genes with a p-value ≤0.05 are shown and those with a BY p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

(G) Protein expression levels in the prefrontal cortex of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with or without IR.

(H) Quantification of Arc protein levels in (G). n = 3, respectively. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 16) = 10.76, *p < 0.05 by post hoc Tukey.

(I) Quantification of Agt protein levels in (G). n = 3, respectively. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 16) = 0.7568.

(J) Quantification of Ptger3 protein levels in (G). n = 3, respectively. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 16) = 2.507, *p < 0.05 by post hoc Bonferroni. Data were shown as mean ± SEM.

Because the term ‘neuron and neurotransmission’ was significantly changed in Figure 3A, we explored these genes further to better understand the behavioral changes we observed. As shown in Figure 3F, all genes with a p-value of less than 0.05 are shown. We note Activity Regulated Cytoskeleton Associated Protein (Arc) and Prostaglandin E Receptor 3 (Ptger3). Arc is a master regulator of synaptic function and critical determinant of memory consolidation (Leung et al., 2022). Arc showed a decrease in RQ4 and RQ4+IR groups, compared to WT mice (Figure 3F). Ptger3 plays a role in cardioprotection and in the nervous system (Meyer-Kirchrath et al., 2009; Treutlein et al., 2018), and was downregulated after IR stress in RQ4 and Wrn mice (Figure 3F). Among the genes related to astrocyte function, angiotensinogen (Agt) plays a role in blood pressure, body fluid, and electrolyte homeostasis (Xi et al., 2022). It was upregulated in both Wrn and Wrn+IR mouse prefrontal cortex (Figure 3F). Serpin Family G Member 1 (Serping1) is a serpin peptidase inhibitor and glycosylated plasma protein involved in the regulation of the complement cascade (Drouet et al., 2022). The serping1 gene was upregulated in all RecQ mice with or without IR compared to WT (Figure 3F). Schlafen family member 8 (Slfn8) plays a role in the DNA damage response (Nakagawa et al., 2018), and it was upregulated in WT+IR, RQ4, Wrn+IR and RQ1+IR mice compared to WT mice (Figure 3F). Synaptophysin (Syp) is a glycoprotein that is an essential component of the synaptic vesicles, which plays an important role in neurotransmission (Valtorta et al., 2004), it was downregulated in RQ4, RQ4+IR, Wrn, Wrn+IR and RQ1 mice compared to WT mice (Figure 3F).

Western blots were conducted to validate gene expression changes. Arc showed a significant decrease in WRN+IR compared to WRN mice, and decrease in RQ1+IR compared to RQ1 mice (Figure 3H). There was no significant difference in Agt protein expression in the prefrontal cortex of RecQ mice (Figure 3G–I). Contrary to what was found by transcriptomics analysis, the expression of Ptger3 in the Wrn+IR group was significantly higher than in Wrn without IR treatment. The expression of Ptger3 in the RQ1+IR group was also significantly higher than that in Wrn without IR , which also is different from what was found by transcriptomics analysis (Figure 3G and 3J).

Many metabolites were changed in RecQ-deficient mice after irradiation stress.

NanoString’s metabolic pathway panel was applied to detect metabolism-related pathways and genes in the prefrontal cortex of RecQ-deficient mice. Compared to WT mice, the amino acid transporter pathway was decreased in WT+IR mice, whereas it was upregulated in RQ1+IR mouse prefrontal cortex compared to WT groups. In Wrn and Wrn+IR groups the DNA damage repair and reactive oxygen response pathways were downregulated compared to WT (Supplementary Figure 1A). The fatty acid synthesis pathway was upregulated in RQ4+IR and RQ1+IR mice. The glucose transport pathway was upregulated in RQ1+IR groups. Hypoxia and Myc pathways were upregulated in Wrn while hypoxia and Myc pathways were changed in RQ1+IR group (Supplementary Figure 1A). Arginine metabolism and cell cycle pathways were dysregulated in RQ1 and Wrn mice, respectively. Additionally, the pentose phosphate pathway was downregulated in RQ4 and Wrn+IR mice compared to WT (Supplementary Figure 1A).

In order to further explore metabolic changes in mouse brains, metabolomics was performed (Supplementary Table 1), and the heatmap shows that many metabolites had significantly changed in each RecQ-deficient mouse group (Supplementary Figure 1B). Overall, whereas WT mice tended to increase expression of metabolites following IR, the RecQ helicase mice appeared to display decreased metabolites following IR. In the non-IR group comparison, we found that glycerol-3-galactoside was significantly increased in RQ4 and Wrn mice, compared to WT mice. Ethanolamine and cysteine were significantly increased in RQ4 mice (Supplementary Figure 1C). In the IR treatment groups, we found that ribonic acid, stearic acid, palmitic acid, and arachidonic acid were significantly reduced in the RQ4+IR and Wrn+IR groups, compared to WT+IR mice (Supplementary Figure 1D). Ethanolamine and glycerol levels were significantly increased in RQ4+IR and Wrn+IR groups. Methionine, pantothenic acid, beta-glycerolphosphate, 2,5-dihydroxypyrazine, glutamic acid, serine, citric acid, and pyrophosphate were significantly reduced in RQ4+IR mice (Supplementary Figure 1D). Ribose was significantly decreased in Wrn+IR mice (Supplementary Figure 1D).

In addition, many metabolites were also altered in RecQ-deficient mice after IR stress. These include inosine 5’-monophosphate, N-acetylaspartic acid, creatinine, oxoproline, dehydroascorbic acid and 1,5-anhydroglucitol. Glycerol-alpha-phosphate was significantly decreased in RQ4+IR mice (Supplementary Figure 2A-G). However, butyrolactam, leucine and pentonic acid were significantly decreased in Wrn+IR mice (Supplementary Figure 2C-J). Lysine, glycine and glycero-3-galactoside were all significantly increased in RQ4+IR mice (Supplementary Figure 2K-M). 2,3-bisphosphoglyceric acid was significantly increased in Wrn+IR mice (Supplementary Figure 2N). Dihydrocholesterol was significantly increased in RQ1+IR mice (Supplementary Figure 2O). Taken together, these findings indicate that metabolomics is greatly altered in RecQ-deficient mice, especially after IR treatment, with the most metabolites altered in RQ4 and Wrn mice after IR stress.

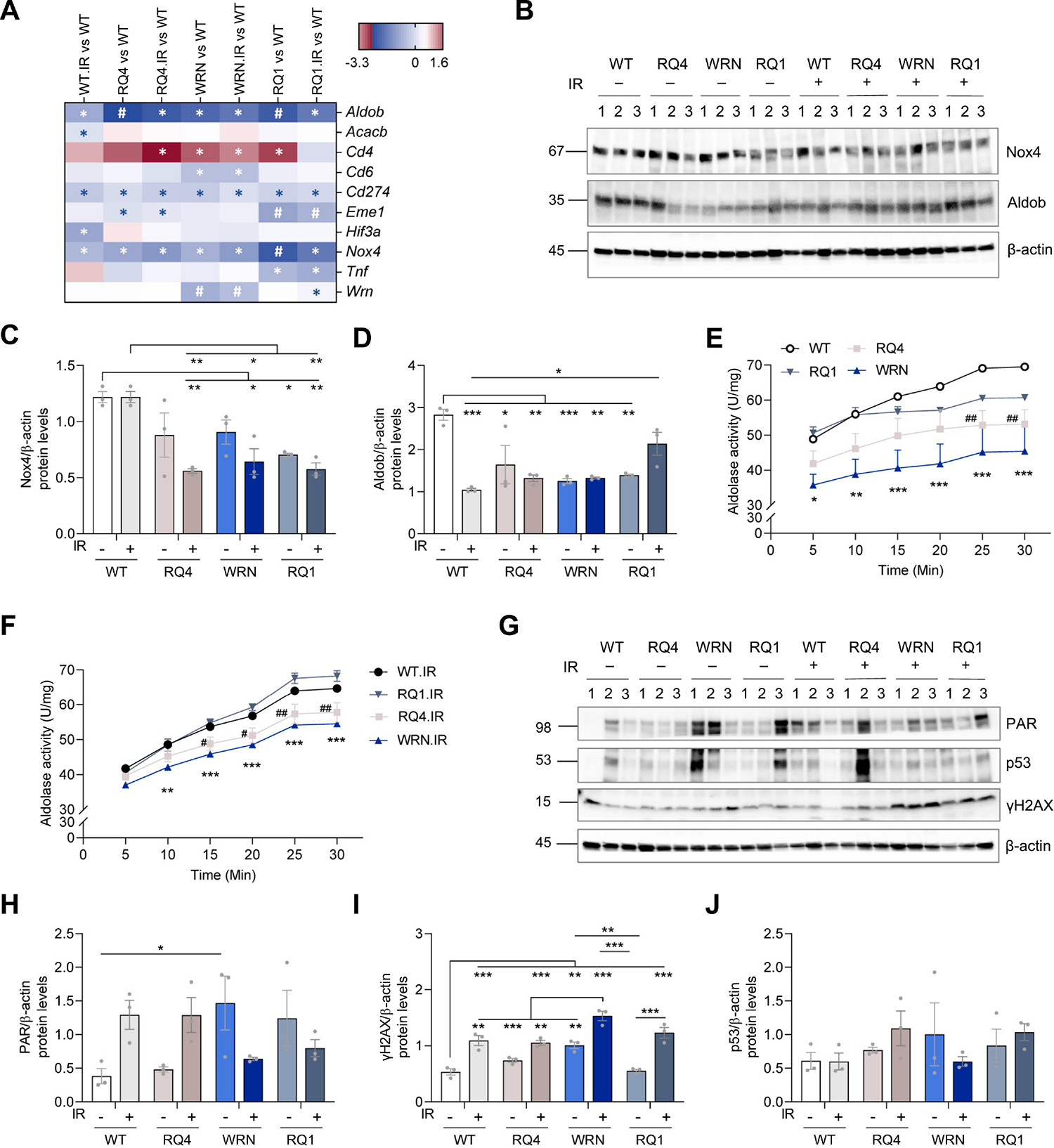

DNA damage responses were upregulated in RecQ-deficient mice.

To investigate DNA damage-related gene changes, we used the NanoString metabolic pathway panel for analysis, and found that aldolase fructose-bisphosphate B (Aldob) and NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) genes were significantly altered in RecQ deficient mice. Aldob plays an important role in gluconeogenesis and fructose metabolism. A recent study reported that Aldob also plays a role in DNA mismatch repair (Lian et al., 2019b). Here, we found that the Aldob gene expression was decreased in all genotypes compared to WT mice, significantly in RQ4 and RQ1 mice. NOX4 is a member of the NOX family of NADPH oxidases. It is a hydrogen peroxide-generating oxygen sensor (Nisimoto et al., 2014). Its expression was decreased in RQ4, Wrn, and RQ1 with or without IR treatment, significantly in RQ1 mice (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 4. DNA damage responses were up-regulated and Aldolase activity were decreased in RecQ-deficient mice.

(A) DNA damage-related genes analysis (part) using NanoString in prefrontal cortex of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with or without IR. *, denotes significant term (p-value ≤ 0.05), #, denotes significant term (both p-value and BY. p-value ≤ 0.05). The full list is in Supplementary Figure 3.

(B) Protein expression levels of Nox4 and Aldob in the prefrontal cortex of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with or without IR.

(C) Quantification of Nox4 protein levels in (B). n = 3, respectively. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 16) = 14.83, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by post hoc Tukey.

(D) Quantification of Aldob protein levels in (B). n = 3, respectively. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 16) = 14.64, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by post hoc Tukey.

(E-F) Relative aldolase activity in the prefrontal cortex of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with (F) or without IR (E) at different time points (0 – 30 min). Aldolase activity was determined by the rate of NADH oxidation. For E, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 48) = 34.65, *: WT vs. Wrn, #: WT vs. RQ4. ##p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by post hoc Bonferroni. For F, two-way ANOVA, F (3, 48) = 63.36, *: WT IR vs. Wrn IR, #: WT IR vs. RQ4 IR. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by post hoc Bonferroni.

(G) Protein levels of PAR, p53, and γH2AX in the prefrontal cortex of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with or without IR.

(H) Quantification of PAR levels in (G). n = 3, respectively. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 16) = 6.479, *p < 0.05 by post hoc Bonferroni.

(I) Quantification of γH2AX levels in (G). n = 3, respectively. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 16) = 19.33, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by post hoc Tukey.

(J) Quantification of p53 levels in (G). n = 3, respectively. Two-way ANOVA, F (3, 16) = 1.021.

Data were shown as mean ± SEM.

To further investigate the changes of Nox4 and Aldob protein expression levels in RecQ-deficient mouse brains, western blot was performed using mouse prefrontal cortex. The results showed that Nox4 expression was significantly decreased in RQ4+IR, RQ1 and RQ1+IR mice, relative to WT mice (Figure 4B–C). However, the expression levels of Aldob were significantly decreased in WT+IR, RQ4 with and without IR, and in Wrn with and without IR and RQ1 mouse brains (Figure 4B and D). Aldolase activity in RQ4 mice was significantly lower than that of WT mice at 25 min and 30 min, while aldolase activity of Wrn mice was significantly lower than that of WT mice at 5–30 min (Figure 4E). In IR-treated mice, the aldolase activity of RQ4+IR mice was significantly lower than that of WT+IR mice at 25–30 min. However, the aldolase activity of Wrn+IR mice was significantly lower than that of WT+IR mice at 10–30 min (Figure 4F).

Since RecQs play an important role in DNA damage responses, we examined the expression of DNA damage-related proteins in these mice. PARylation was increased in the prefrontal cortex of Wrn mice (Figure 4G, H), and the expression of γH2AX was significantly increased after IR treatment in all RecQ-deficient mice (Figure 4G, I), which means they have more DNA damage. However, there were no significant differences in the expression levels of p53 among the mice (Figure 4J). In conclusion, these results suggest that Wrn and RQ1 loss in mice aggravates the expression of DNA damage-related γH2AX proteins after IR treatment. Moreover, Aldob expression and activity were also significantly decreased in RQ4 and Wrn mice both with or without IR treatment (Figure 4F).

Discussion

RecQ deficiency leads to the development of many premature aging features (Croteau et al., 2014). RecQ-deficient mice have been studied before, but not with a focus on behaviors and with a view to DNA damage exposure. Here, we conducted a series of behavioral studies on RecQ-deficient mice and found that they had defects in depressive behavior, social behavior, and cognitive function. Wrn mice showed more distance travelled suggesting relatively high locomotor activity. There was no significant change in anxious behavior. Social and depressive behaviors have not been established in patients with RecQ-deficient disorders, possibly because the number of patients is so small. Individuals with diseases caused by RecQ deficiency may have social impairments, which may be neglected because other symptoms are more protruding, and this aspect has not been studied in detail. This area of research has not been developed, although a deeper understanding may give us an opportunity to link behavioral traits to specific known genes and therefore to gain mechanistic insight into the defects.

In this study, we found that various metabolites were changed in the RecQ mice compared with WT mice with or without IR treatment. These may be potential targets for RecQ dysfunction. Glycerol-3-galactoside is synthesized from UDP-galactose and diacylglycerol (DAG) by a microsomal galactosyltransferase, and the lysosomal enzyme cathepsin D helps produce UDP-galactose. Glycerol-3-galactoside is then hydrolyzed by α- or β-galactosidase to galactose, glycerol, or fatty acid (Nisimoto et al., 2014). In this study, we found that glycerol-3-galactoside was significantly elevated in the RQ4 and Wrn mice compared to controls without IR treatment (Supplementary Figure 1C) and RQ4 mice with IR treatment (Supplementary Figure 1M). Recently, glycerol-3-galactoside was identified as an independent marker to predict diabetic kidney disease (DKD) (Liu et al., 2021), and diabetes mellitus is reported to be common in WS patients (Oshima et al., 2017). Another identified metabolite was glycerol, which belongs to the glycerophosphate pathway and was significantly increased in the RQ4 and Wrn mice with IR treatment (Supplementary Figure 1D). This change can promote acute kidney injury and contribute to hippocampal long-term potentiating deficits and memory impairments (Sarkaki et al., 2022). In addition, the level of glycerol-alpha-phosphate involved in the glycolysis pathway was decreased in the RecQ4 mice with IR treatment (Supplementary Figure 2G). Thus, these data suggest that these metabolic pathways may play an important role in the RecQ deficit-related disorders.

Some metabolites, including ethanolamine, cysteine, and methionine may contribute to mental disorders in the RecQ mice. It was reported that increased levels of ethanolamine in plasma was observed in the patients with major depression disorder and this may be linked to neuroinflammatory responses (Woo et al., 2015). Increased ethanolamine can inhibit mitochondrial function, which contributes to mental diseases, such as depression and bipolar disorder (Modica-Napolitano and Renshaw, 2004). In line with this, we found that the level of ethanolamine was elevated in RecQ4 mice with or without IR treatment and in Wrn mice after IR treatment. These mice have social inability and depressive-like behaviors as we have reported here. Cysteine was alleged to influence the reward-reinforcement pathway, and the precursor of cysteine, N-acetyl-L-cysteine can exert a therapeutic effect on psychiatric disorders, such as autism, depression, and substance misuse (Bradlow et al., 2022; Egashira et al., 2012; Sansone and Sansone, 2011). This is consistent with a possible role of cysteine in the mood regulation in the RecQ mice, which showed social and depressive deficits in this study. A recent study revealed that methionine promoted resilience to social anxiety in mice (Bilen et al., 2020). Methionine is converted to S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) by the enzyme methionine adenosyltransferase in liver. SAMe is a promising antidepressant agent for depression and aging-related diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease (Di Rocco et al., 2000; Karas Kuželički, 2016). In the RecQ4 mice with IR treatment, the level of methionine was decreased.

There were several changed metabolites that may be involved in altered cognition ability in the RecQ mice. For instance, arachidonic acid (ARA) and glutamic acid (GLU) were down-regulated in the RecQ mice after IR treatment. Glutamic acid is known to regulate learning and memory (McEntee and Crook, 1993). Several studies have shown that ARA improves learning and memory deficits and decreases oxidative damage (Inoue et al., 2019; Li et al., 2015). Similarly, we found that ARA decreased in the RQ4 and Wrn mice after IR treatment, accompanying cognitive impairments (Figure 2B). Moreover, administrating ARA is reported to support cognitive, motor, and social development in humans and mice (Carlson et al., 2019; Yui et al., 2012). However, the specific underlying mechanisms of these molecules in the pathology of RecQ dysfunction are still unknown and need further study in the future.

We also investigated potential underlying biological molecular mechanisms in the association between RecQ deficiency and behavioural traits after DNA damage exposure. To address this, we performed gene expression analysis by NanoString Technologies in brain tissues from prefrontal cortex of RecQ-deficient mice. The prefrontal cortex is a hub for regulating depression (Hare and Duman, 2020; Pizzagalli and Roberts, 2022; Zhang et al., 2018), social function (Bicks et al., 2015; Levy et al., 2019), and cognition (Dalley et al., 2004; Friedman and Robbins, 2022). Prefrontal cortex projects to several brain areas that are known to influence sociability, including amygdala, nucleus accumbens, hippocampus and brainstem, highlighting the importance of this structure in interpreting and modifying social behaviors (Franklin et al., 2017). It also contributes to the discrimination of object familiarity and recognition memory, which may be involved in the novel object recognitive test (Akirav and Maroun, 2006; Wang et al., 2021).

According to our NanoString’s metabolic pathway panel, Aldob was dramatically downregulated in the prefrontal cortex of RecQL-deficient mice compared to WT. We confirmed that RecQ deficiency leads to decreased expression and activity of Aldob (Figure 4D–F). In addition, recent work reported that Aldob expression was significantly correlated to DNA mismatch repair (MMR) (Lian et al., 2019a). Protein-protein interaction analysis revealed an interaction between Aldob and DNA repair-related proteins (De Oliveira et al., 2016), indicating that Aldob may play a role in the DNA repair. This enzyme is one of three aldolases responsible for breaking down certain molecules in cells throughout the body (Chang et al., 2018). Mutations in the Aldob gene results in a condition known as hereditary fructose intolerance (HFI). HFI has not been associated with psychomotor retardation. However, the patient’s inability to handle sucrose might produce abnormal eating behaviors, especially in school-age children (Chinsky and Steiner, 2009), suggesting that loss of Aldob isozyme is associated with behavioral abnormalities. Further, due to the lack of the functional aldehyde Aldob, HFI patients cannot properly process F1P, resulting in the accumulation of F1P in body tissues. In addition to being toxic to cellular tissues, high levels of F1P trap phosphate in an unavailable form that does not return to the general phosphate pool, leading to depletion of phosphate and ATP stores. The lack of readily available phosphate leads to a cessation of glycogenolysis in the liver, resulting in hypoglycemia. This accumulation also inhibits gluconeogenesis, further reducing the amount of readily available glucose. Loss of ATP can cause a number of problems, including inhibition of protein synthesis and liver and kidney dysfunction. In Werner syndrome a well-known risk factor is underlying diabetes (Tsuge and Shimamoto, 2022). And Werner syndrome patients are vulnerable to develop kidney deficits (Brodsky, 2014). Thus, we postulate that the decreased Aldob expression and activity may be a potential target of the pathologies in WS patients.

The Nox4 gene was also inhibited in RecQ-deficient mice, especially in the RQ1 and 4 groups (Figure 4A–C). NOX4 is widely expressed in various brain regions and involved in cell signal transduction, metabolic regulation, and the removal of harmful substances (Xie et al., 2020). A decrease in NOX4 expression led to senescence of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and secretion of interleukin 6 (IL-6) and 8 (IL-8). Interestingly, NOX4 downregulation correlated with the inhibition of cell proliferation and with the induction of senescence. The number of SA-β-gal-positive cells correlated inversely with the level of NOX4 expression (Przybylska et al., 2016). These reports suggest that downregulated Aldob activity and Nox4 expression in RecQ-deficient mice may lead to metabolic disorders, which may lead to behavioral abnormalities.

In conclusion, we found behavioral changes in RecQ-deficient mice, including obvious depression and social behavioral abnormalities, and decreased cognitive function. We also found that the expression and activity of Aldob and the expression of Nox4 changed in the brains of RecQ-deficient mice. Further research should be conducted on the association of these changes in human with RecQ deficiencies. Brain specific mouse models, such as neuron-specific knockout of the RecQ helicases and IR localized to the brain should be considered for future studies.

Since the number of patients with RecQ deficient diseases are so small, it is difficult to get a thorough insight into their clinical phenotypes and the frequency of the clinical features. Studies in mice can provide insights into disease mechanism, which can then be explored in humans.

Materials and methods

Mice

The RecQ-deficient mice studied were RecQ4 (RQ4), Wrn, and RecQ1 (RQ1), and the WT control mice were littermates of RQ1 HO mice. RQ1 mice were obtained from Dr. Blackshear at NIEHS (Sharma et al., 2007). Wrn mice were obtained from Dr. Johnson (Lombard et al., 2000). The RQ4 deficient mice were obtained from Dr. Lou. The homozygous Recql4 mutant mice contain a PGKHprt mini-gene cassette inserted within exons 9–13, resulting in the deletion of 80% of the genomic DNA that encodes the helicase domain, which were generated as described previously (Lu et al., 2014a; Mann et al., 2005). Mice were fed ad libitum and maintained on a 12 h light dark cycle.

For the IR treatment and controls, mice were 8–11 months old and the male to female ratio was 1:1. Randomization was used to allocate animals to the IR and non-IR groups to control for age variations. 6–8 mice per group were used. The mice numbers for each groups were as follows: WT (Non-IR): 3 M (males) and 4 F (females), 8–9 months old when beginning the experiments; WT (IR): 4 M and 4 F, 8–11 months old; RQ4 (Non-IR): 4 M and 3 F, 8–9 months old; RQ4 (IR): 3 M and 5 F, 8–10 months old; WRN (Non-IR): 4 M and 3 F, 8–11 months old; WRN (IR): 3 M and 3 F, 8–11 months old; RQ1 (Non-IR): 6 M and 2 F, 8–11 months old; RQ1 (IR): 6 M and 2 F, 9–11 months old.

These mice all received a single whole-body dose of ionizing radiation (IR, 6 Gy) and were then subjected to a series of behavioral experiments starting 24 hours after IR. They were subjected to the whole body in Nordion Gamma cell 40 Exactor Irradiator. IR (6 Gy) was delivered at a rate of 0.74 Gy/min. The irradiation was done once and then tested in behavior tests. Since these mice underwent a series of behavioral experiments after IR, tissues were collected 3 months later. The mice were housed at the National Institute on Aging (NIA) under standard conditions and fed standard animal chow. All animal procedures and protocols were approved by the NIA Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

The tissue collection of mice was divided into two parts. Some of the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and were then perfused with PBS buffer, and then the tissues were quickly frozen with liquid nitrogen. In mouse brains, we used the prefrontal cortex, the cortex, the hippocampus, and the cerebellum. For immunostaining preparation, mice were anesthetized, and then perfused with PBS buffer and then with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. The collected brains were placed in 4% PFA for 24 h and then equilibrated in 30% sucrose for 24 h, for future immunostaining experiments.

Y maze

The Y maze spontaneous alternation performance (SAP) test measures the ability to recognize a previously explored environment. The maze consisted of three arms (8 × 30 × 15 cm), with an angle of 120 degrees between each arm. The number of entries and alterations were recorded by the ANY-maze video tracking system. Mice were introduced to the center of the Y maze and allowed to freely explore the maze for 10 min. Between trials the arms were cleaned with 70% ethanol solution. SAP is the subsequent entry into a novel arm over the course of 3 entries; the percentage SAP is calculated by the number of actual alternations/(total arm entries − 2) × 100.

Object recognition test

The object recognition tests were performed as described previously (Hou et al., 2021). The device was a Plexiglas box (25 × 25 × 25 cm3). Mice could explore two identical objects for 10 min during the training phase. After the training phase, there is a delay period (1 h) during which the mouse is returned to its home cage. During the test phase, one of the objects from the training phase is replaced with a novel object, and the mouse is allowed to explore both objects again for 10 min. To exclude olfactory cues, the boxes and objects were cleaned before each test. The automatic video tracking system (ANY-maze) was used to monitor exploration behavior. Exploration time was calculated as the length of time each mouse sniffed or pointed its nose or paws at the object. The ‘recognition index’ refers to the time spent exploring the novel object relative to the time spent exploring both objects.

Elevated plus maze

The elevated plus maze test is a widely used behavioral test to investigate the anxiety-like behavior in mice. The apparatus consists of two closed arms (30 × 5 × 15 cm) with high walls and two open arms (30 × 5 × 2.5 cm) with low walls. Before starting the test, the mice were allowed to acclimate to the testing room for at least an hour. The experimenter handled the mice gently to reduce stress during the test. Each mouse was placed in the central area of the maze facing one of the open arms. Time spent in the open arms was measured for 5 min with the EthoVisionXT video-imaging system. The time spent and the number of entries into the open arms were measured. After each test, the maze was cleaned to remove any odor or trace left by the previous mouse.

Social behavior test

The three-chamber sociability and social novelty test is widely used to assess sociability and social recognition in rodents (Moy et al., 2004). Rodents normally prefer to spend more time with another rodent (sociability) and will investigate a novel intruder longer than a familiar one (social novelty). Briefly, in the first habituation phase, each mouse was placed in a room without other mice for 10 minutes to acclimatize. In the second training stage, a mouse in a cage was placed in the chamber on the left, and an empty cage (that is, object) was placed in the chamber on the opposite side. The test mouse is placed in the center chamber and given access to all three chambers for 10 minutes. The time spent in the chamber with animal or object was recorded as interaction time to detect the sociability of mice. In the third testing stage, the test mouse is again placed in the center chamber. An unfamiliar mouse was placed in a chamber in the room on the right, while the familiar mouse was still in the previous chamber. The test mouse is given access to all three chambers for 10 minutes, and the time spent in each chamber is recorded, and the social novelty of the mice was examined.

Forced swim test

To evaluate behavioral despair in mice, the forced swim test was performed as previously described (Ayatollahi et al., 2017). We allow the mice to acclimate in the testing room for at least 1 hour before testing. Each mouse was individually placed in a transparent cylinder (height: 25 cm, diameter: 10 cm) filled with 15 cm depth fresh water (25 ± 1 °C) for 6 min. The mouse swimming and floating behaviors were recorded during the last 4 minutes of the observation period. Mice were judged to be immobile when they ceased struggling and remained floating motionless in the water and making only those movements necessary to keep their head above water.

Metabolomics

The mice cerebellum samples were used to detect metabolomics. Mouse cerebellum tissues were extracted and flash frozen and sent to UC Davis Genome Center Core Facilities using ALEX-CIS GCTOF mass spectrometry for analysis. N = 5, 5, 3, 4, 4, 3, 4, 5 mice in WT, WT+IR, RQ4, RQ4+IR, Wrn, Wrn+IR, RQ1, RQ1+IR groups, respectively. The data were analyzed by two-way or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Western blots

Mouse brain tissues from prefrontal cortex were homogenized in 1X RIPA lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, #9806S) containing protease inhibitors cocktail, and halt phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Specifically, the area of the prefrontal cortex evaluated included the lateral prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. These regions are known for their involvement in decision making, problem solving, and emotional regulation. Additionally, these areas also contribute to self-control, complex cognition, and working memory (Dalley et al., 2004). Collected samples were sonicated on ice and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined with Bradford reagent. 15 μg proteins were separated on 4–15% Bis-Tris gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, #5671085) and transferred to PVDF blotting membranes. Membranes were then blocked for 1h at RT in TBS-T (500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 0.1% Tween 20) supplemented with 5% non-fat dried milk. Subsequently membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies followed by 1 h at RT with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Proteins were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescent detection system (EMD Millipore, #WBKLS0500) and ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, #12003153, CA, USA). Quantification was performed using ImageJ. The specific primary antibodies used including: Aldob (Proteintech, #18065-1-AP), Agt (Proteintech, #11992-1-AP), Ptger3 (Proteintech, #14357-1-AP), p53 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, # sc-126), Arc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, #sc-17839), PAR (Trevigen, #4335-MC-100), γH2AX (Cell signaling, #9718), NOX4 (Abcam, #ab216654), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, #A2228). Secondary antibodies including anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; Southern biotech, #1010-05) and anti-rabbit IgG (Southern biotech, #4010-05) were obtained from Southern biotech. Primary antibodies were used at a 1:1000 dilution (unless otherwise stated), with secondary antibodies used at a 1:5000 dilution (unless otherwise stated). All antibodies were validated for use in mouse/human tissues and detailed antibody validation profiles are available on the websites of the companies the antibodies were sourced from.

Aldolase assay

Aldolase catalyzes the reversible reaction of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (F-1,6-BP) to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate. Aldolase activity was determined by measuring a colorimetric assay kit (#K665-100; BioVision, San Francisco, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, the prefrontal cortex tissue (10 mg) was rapidly homogenized with 100 μl aldolase assay buffer on ice and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to 96-well clear plate with a flat bottom. It was measured absorbance at 450 nm for 30 min at 37°C on a multi-well spectrophotometer using Microplate Manager v5.2.1 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Unit definition: One unit of aldolase is the amount of enzyme that generates 1.0 μmol of NADH per minute at pH 7.2 at 37°C.

Gene expression analysis by NanoString Technologies

NanoString analysis was performed on the prefrontal cortex of RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice and WT mice with or without IR treatment. Total RNA was purified with a Nucleospin RNA isolation kit (Macherey-Nagel, #740955.250) as per the manufacturer’s protocol and quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. Purified RNA was diluted in nuclease-free water to 20 ng/uL. It was hybridized in CodeSet Master mix carrying hybridization buffer, Reporter Code Set, and Capture Probe Set for 16 to 24 hours at 65°C (NanoString Technologies, MAN-10056–05) and then applied to the nCounter Prep Station (MAN-C0035). The Prep Station can process up to 12 samples per run in approximately 2.5 to 3 hours depending on which protocol is used. We loaded the hybridized RNA onto the nCounter Prep Station for immobilization in the sample cartridge according to the manufacturer’s high sensitivity protocol. Next, the sample cartridge was subsequently processed for 2 hours in the nCounter Analysis System. The nCounter Digital Analyzer which is a multi-channel epifluorescence scanner collected data by taking images of the immobilized fluorescent reporters in the sample cartridge with a CCD camera through a microscope objective lens. The results were directly downloaded from the digital analyzer in RCC files format. NanoString data was analyzed via the NanoString nCounter nSolver 4.0 software (MAN-C0019-08) with the NanoString Advanced Analysis 2.0 plugin (MAN-10,030-03) following the NanoString Gene Expression Data Analysis Guidelines (MAN-C0011-04). Both positive control and housekeeping normalization were used to normalize all sources of variation associated with the platform. Genes were selected by a p-value ≤0.05, while genes with a BY corrected p-value of ≤0.05were considered statistically significant.

Randomization and blinding

Animal/samples (mice) were assigned randomly to the various experimental groups, and mice were randomly selected for the behavioral experiments. In data collection and analysis (for example, mouse behavioral studies, mouse imaging data analysis, as well as imaging and data analysis of electron microscopy), the performer(s) was (were) blinded to the experimental design.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by the Graph Pad Prism 8.0 software (San Diego, CA) and Results presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The statistical significance of the behavior tests, NanoString analysis, aldolase assay, and western blots were determined by two-way ANOVA analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests (unless otherwise specified). The metabolomics were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests. Differences were considered to be statistically significant with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our samples sizes (mouse experiments) are similar to those reported in previous publications.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Many metabolites were changed in RecQ-deficient mice after irradiation stress.

(A) Metabolic pathway panel analysis using NanoString in prefrontal cortex of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with or without IR. *denotes significant terms.

(B) Metabolomics analysis in the cerebellum of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with or without IR. *denotes significant terms.

(C-D) Metabolomics changes in the cerebellum of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with or without IR. N = 5, 5, 3, 4, 4, 3, 4, 5 mice in WT, WT+IR, RQ4, RQ4+IR, Wrn, Wrn+IR, RQ1, RQ1+IR groups, respectively. One-way ANOVA. (C) For glycerol-3-galactoside, F (3, 12) = 14.81; for ethanolamine, F (3, 12) = 9.014; for cysteine, F (3, 12) = 6.375. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by post hoc Tukey. (D) For ribonic acid, F (3, 13) = 10.82; for stearic acid, F (3, 13) = 7.378; for palmitic acid, F (3, 13) = 7.491; for arachidonic acid, F (3, 13) = 6.337; for ethanolamine, F (3, 13) = 33.59; for glycerol, F (3, 13) = 11.50; for methionine, F (3, 13) = 5.261; for pantothenic acid, F (3, 13) = 3.391; for beta-glycerolphosphate, F (3, 13) = 3.917; for 2,5-dihydroxypyrazine, F (3, 13) = 5.880; for glutamic acid, F (3, 13) = 6.068; for serine, F (3, 13) = 5.456; for citric acid, F (3, 13) = 4.425; for pyrophosphate, F (3, 13) = 4.840; for ribose, F (3, 13) = 6.697; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by post hoc Tukey. Data were shown as mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Figure 2. Other metabolites were changed in RECQL-deficient mice after irradiation stress.

(A-O) More metabolomics changes in the cerebellum of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with or without IR. Data were shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (A) F (3, 13) = 3.398; (B) F (3, 13) = 4.312; (C) F (3, 13) = 5.421; (D) F (3, 13) = 5.671; (E) F (3, 13) = 5.257; (F) F (3, 13) = 4.956; (G) F (3, 13) = 6.136; (H) F (3, 13) = 3.788; (I) F (3, 13) = 4.386; (J) F (3, 13) = 5.823; (K) F (3, 13) = 4.090; (L) F (3, 13) = 4.376; (M) F (3, 13) = 4.283; (N) F (3, 13) = 6.156; (O) F (3, 13) = 3.582.

Supplementary Figure 3. The full list of DNA damage-related genes analysis using NanoString in prefrontal cortex of mice. *, denotes significant term (p-value ≤ 0.05), #, denotes significant term (both p-value and BY. p-value ≤ 0.05).

Supplementary Table 1. Metabolomics data.

The metabolomics data of WT, RQ4, Wrn, RQ1 mice with or without IR.

N = 5, 5, 3, 4, 4, 3, 4, 5 mice in WT, WT+IR, RQ4, RQ4+IR, Wrn, Wrn+IR, RQ1, RQ1+IR groups, respectively.

Highlights.

Abnormal cognitive behavior is present in RecQ-deficient mice.

RecQ dysfunction impairs social ability and induces depressive-like behavior in mice after a single exposure to IR.

Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses revealed significant alterations in RecQ-deficient mice, especially after IR exposure.

Pathways related to neuronal and microglial functions, DNA damage repair, cell cycle, and reactive oxygen responses were downregulated in the RecQ4 and WRN mice.

Aldolase Fructose-Bisphosphate B (Aldob) and NADPH Oxidase 4 (Nox4) were differentially expressed in RecQ-deficient mice.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alfred May and Tom for performing irradiations. We thank Dr. Kulikowicz and Dr. Akbar Ali for reading the paper. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH (V.A.B.). Y.H. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (#82171405), the Lingang Laboratory (#LG-QS-202205-10), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The NanoString GEO accession number for the data reported in this paper is GSE 220637. All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Abu-Libdeh B, et al. , 2022. RECON syndrome is a genome instability disorder caused by mutations in the DNA helicase RECQL1. J Clin Invest. 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akirav I, Maroun M, 2006. Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Is Obligatory for Consolidation and Reconsolidation of Object Recognition Memory. Cereb. Cortex 16, 1759–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annus T, et al. , 2022. Bloom syndrome helicase contributes to germ line development and longevity in zebrafish. Cell Death Dis. 13, 363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayatollahi AM, et al. , 2017. TAMEC: a new analogue of cyclomyrsinol diterpenes decreases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Neurol Res. 39, 1056–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicks LK, et al. , 2015. Prefrontal Cortex and Social Cognition in Mouse and Man. Front. Psychol 6, 1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilen M, et al. , 2020. Methionine mediates resilience to chronic social defeat stress by epigenetic regulation of NMDA receptor subunit expression. Psychopharmacology. 237, 3007–3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradlow RCJ, et al. , 2022. The Potential of N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC) in the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders. CNS Drugs. 36, 451–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky SV, 2014. Anticoagulants and acute kidney injury: clinical and pathology considerations. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 33, 174–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SJ, et al. , 2019. A diet with docosahexaenoic and arachidonic acids as the sole source of polyunsaturated fatty acids is sufficient to support visual, cognitive, motor, and social development in mice. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 13, 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YC, et al. , 2018. Roles of Aldolase Family Genes in Human Cancers and Diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 29, 549–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinsky JM, Steiner RD, 2009. Chapter 30 - Inborn errors of metabolism. Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics (Fourth Edition). [Google Scholar]

- Chu WK, Hickson ID, 2009. RecQ helicases: multifunctional genome caretakers. Nat Rev Cancer. 9, 644–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croteau DL, et al. , 2014. Human RecQ helicases in DNA repair, recombination, and replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 83, 519–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croteau DL, et al. , 2012. RECQL4 localizes to mitochondria and preserves mitochondrial DNA integrity. Aging cell. 11, 456–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, et al. , 2004. Prefrontal executive and cognitive functions in rodents: neural and neurochemical substrates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 28, 771–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira KM, et al. , 2016. Clinical findings, dental treatment, and improvement in quality of life for a child with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Contemp Clin Dent. 7, 240–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Rocco A, et al. , 2000. S - adenosyl - methionine improves depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease in an open - label clinical trial. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 15, 1225–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouet C, et al. , 2022. SERPING1 Variants and C1-INH Biological Function: A Close Relationship With C1-INH-HAE. Front Allergy. 3, 835503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egashira N, et al. , 2012. N-acetyl-L-cysteine inhibits marble-burying behavior in mice. Journal of pharmacological sciences. 119, 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TB, et al. , 2017. Prefrontal cortical control of a brainstem social behavior circuit. Nat. Neurosci 20, 260–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman NP, Robbins TW, 2022. The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 47, 72–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare BD, Duman RS, 2020. Prefrontal cortex circuits in depression and anxiety: contribution of discrete neuronal populations and target regions. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 2742–2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, et al. , 2021. NAD(+) supplementation reduces neuroinflammation and cell senescence in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease via cGAS-STING. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui CW, et al. , 2018. Nonfunctional mutant Wrn protein leads to neurological deficits, neuronal stress, microglial alteration, and immune imbalance in a mouse model of Werner syndrome. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 73, 450–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, et al. , 2019. Effect of chronic administration of arachidonic acid on the performance of learning and memory in aged rats. Food & nutrition research. 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karas Kuželički N, 2016. S-Adenosyl methionine in the therapy of depression and other psychiatric disorders. Drug development research. 77, 346–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopka A, Atkin JD, 2022. The Role of DNA Damage in Neural Plasticity in Physiology and Neurodegeneration. Front Cell Neurosci. 16, 836885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel M, et al. , 2001. Tumorigenic effect of nonfunctional p53 or p21 in mice mutant in the Werner syndrome helicase. Cancer Res. 61, 1816–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung HW, et al. , 2022. Arc Regulates Transcription of Genes for Plasticity, Excitability and Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DR, et al. , 2019. Dynamics of social representation in the mouse prefrontal cortex. Nat. Neurosci 22, 2013–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, et al. , 2015. Arachidonic acid attenuates learning and memory dysfunction induced by repeated isoflurane anesthesia in rats. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine. 8, 12365–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian J, et al. , 2019a. Aldolase B impairs DNA mismatch repair and induces apoptosis in colon adenocarcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 215, 152597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian J, et al. , 2019b. Aldolase B impairs DNA mismatch repair and induces apoptosis in colon adenocarcinoma. Pathology - Research and Practice. 215, 152597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, et al. , 2021. Serum integrative omics reveals the landscape of human diabetic kidney disease. Molecular Metabolism. 54, 101367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard DB, et al. , 2000. Mutations in the WRN gene in mice accelerate mortality in a p53-null background. Mol Cell Biol. 20, 3286–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, et al. , 2014a. Senescence induced by RECQL4 dysfunction contributes to Rothmund-Thomson syndrome features in mice. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, et al. , 2014b. Senescence induced by RECQL4 dysfunction contributes to Rothmund–Thomson syndrome features in mice. Cell Death & Disease. 5, e1226–e1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann MB, et al. , 2005. Defective sister-chromatid cohesion, aneuploidy and cancer predisposition in a mouse model of type II Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 14, 813–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEntee WJ, Crook TH, 1993. Glutamate: its role in learning, memory, and the aging brain. Psychopharmacology. 111, 391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Kirchrath J, et al. , 2009. Overexpression of prostaglandin EP3 receptors activates calcineurin and promotes hypertrophy in the murine heart. Cardiovasc Res. 81, 310–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modica-Napolitano JS, Renshaw PF, 2004. Ethanolamine and phosphoethanolamine inhibit mitochondrial function in vitro: implications for mitochondrial dysfunction hypothesis in depression and bipolar disorder. Biological psychiatry. 55, 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy S, et al. , 2004. Sociability and preference for social novelty in five inbred strains: an approach to assess autistic-like behavior in mice. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 3, 287–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa K, et al. , 2018. Schlafen-8 is essential for lymphatic endothelial cell activation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Int Immunol. 30, 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng AJ, et al. , 2015. The DNA helicase recql4 is required for normal osteoblast expansion and osteosarcoma formation. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisimoto Y, et al. , 2014. Nox4: a hydrogen peroxide-generating oxygen sensor. Biochemistry. 53, 5111–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opresko PL, et al. , 2004. Junction of RecQ helicase biochemistry and human disease. J Biol Chem. 279, 18099–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima J, et al. , 2017. Werner syndrome: clinical features, pathogenesis and potential therapeutic interventions. Ageing research reviews. 33, 105–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvathaneni S, et al. , 2013. Human RECQ1 interacts with Ku70/80 and modulates DNA end-joining of double-strand breaks. PLoS One. 8, e62481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignolo RJ, et al. , 2008. Defects in telomere maintenance molecules impair osteoblast differentiation and promote osteoporosis. Aging Cell. 7, 23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Roberts AC, 2022. Prefrontal cortex and depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 47, 225–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popuri V, et al. , 2013. Human RECQL5: guarding the crossroads of DNA replication and transcription and providing backup capability. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 48, 289–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prut L, Belzung C, 2003. The open field as a paradigm to measure the effects of drugs on anxiety-like behaviors: a review. European journal of pharmacology. 463, 3–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybylska D, et al. , 2016. NOX4 downregulation leads to senescence of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Oncotarget. 7, 66429–66443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA, 2011. Getting a Knack for NAC: N-Acetyl-Cysteine. Innovations in clinical neuroscience. 8, 10–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkaki A, et al. , 2022. Synaptic plasticity and cognitive impairment consequences to acute kidney injury: Protective role of ellagic acid. Iranian journal of basic medical sciences. 25, 621–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, et al. , 2007. RECQL, a member of the RecQ family of DNA helicases, suppresses chromosomal instability. Mol Cell Biol. 27, 1784–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott RT, et al. , 2021. Profiling DNA break sites and transcriptional changes in response to contextual fear learning. PLoS One. 16, e0249691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekely AM, et al. , 2005. Werner protein protects nonproliferating cells from oxidative DNA damage. Molecular and cellular biology. 25, 10492–10506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro T, et al. , 2013. Functional deficit associated with a missense Werner syndrome mutation. DNA Repair (Amst). 12, 414–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavera-Tapia A, et al. , 2019. RECQL5: Another DNA helicase potentially involved in hereditary breast cancer susceptibility. Hum Mutat. 40, 566–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tivey HS, et al. , 2013. p38 MAPK stress signalling in replicative senescence in fibroblasts from progeroid and genomic instability syndromes. Biogerontology. 14, 47–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treutlein EM, et al. , 2018. The prostaglandin E2 receptor EP3 controls CC-chemokine ligand 2-mediated neuropathic pain induced by mechanical nerve damage. J Biol Chem. 293, 9685–9695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuge K, Shimamoto A, 2022. Research on Werner Syndrome: Trends from Past to Present and Future Prospects. Genes (Basel). 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valtorta F, et al. , 2004. Synaptophysin: leading actor or walk-on role in synaptic vesicle exocytosis? Bioessays. 26, 445–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, et al. , 2021. Hippocampus–prefrontal coupling regulates recognition memory for novelty discrimination. J. Neurosci 41, 9617–9632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, et al. , 2000. Cellular Werner phenotypes in mice expressing a putative dominant-negative human WRN gene. Genetics. 154, 357–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo HI, et al. , 2015. Plasma amino acid profiling in major depressive disorder treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics. 21, 417–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi H, et al. , 2022. Fluorescence detection of the human angiotensinogen protein by the G-quadruplex aptamer. Analyst. 147, 4040–4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, et al. , 2020. Inhibition of NOX4/ROS Suppresses Neuronal and Blood-Brain Barrier Injury by Attenuating Oxidative Stress After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Front Cell Neurosci. 14, 578060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, et al. , 2016. Exome Sequencing in a Family Identifies RECQL5 Mutation Resulting in Early Myocardial Infarction. Medicine (Baltimore). 95, e2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yui K, et al. , 2012. Effects of large doses of arachidonic acid added to docosahexaenoic acid on social impairment in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 32, 200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang FF, et al. , 2018. Brain structure alterations in depression: Psychoradiological evidence. CNS Neurosci. Ther 24, 994–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The NanoString GEO accession number for the data reported in this paper is GSE 220637. All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.