Abstract

Haemophilus influenzae can cause intra-amniotic infection and early pregnancy loss. The mode of transmission and risk factors for H. influenzae uterine cavity infections are unknown. Here, we present the case of chorioamnionitis caused by ampicillin-resistant H. influenzae in a 32-year-old Japanese woman at 16 weeks of gestation. Despite empirical treatment, including ampicillin, as recommended by the current guidelines, she had fetal loss. The antimicrobial regimen was changed to ceftriaxone, and the treatment was completed without complications. Although the prevalence and risk factors for chorioamnionitis caused by ampicillin-resistant H. influenzae are unknown, clinicians need to recognize H. influenzae as a potentially drug-resistant and lethal bacterium for pregnant women.

Keywords: Haemophilus influenzae, Chorioamnionitis, Oral transmission, Fetal loss, Pregnancy

Highlights

-

•

Chorioamnionitis caused by ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae in a 32-year-old woman at 16 weeks of gestation.

-

•

Clinicians need to recognize H. influenzae as a potentially drug-resistant.

Introduction

Haemophilus influenzae is commonly found in the upper airway, where it causes respiratory tract infections [1]. Although the risk factors and route of transmission have not been thoroughly investigated, growing evidence suggests a correlation between chorioamnionitis and H. influenzae, particularly non-typeable H. influenzae (NTHi) [2]. Chorioamnionitis can be fatal to neonates, and the standard empiric antibiotic regimen lacks enough spectrum for NTHi because the ampicillin resistance rate has been dramatically increasing [3], [4]. Here, we present the case of a 32-year-old Japanese woman at 16 weeks of gestation. She reported having oral sex with her husband a few days before the presentation. She was diagnosed with chorioamnionitis and bacteremia due to ampicillin-resistant NTHi, which resulted in stillbirth despite antibiotic treatment with ampicillin and erythromycin.

Case report

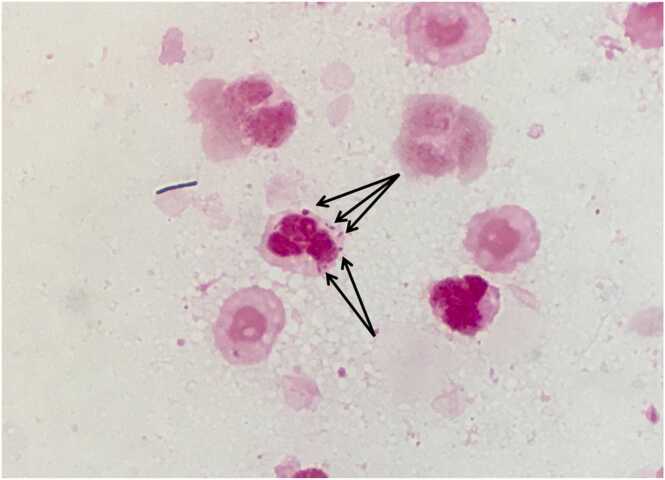

A 32-year-old Japanese woman at 16 weeks of gestation was admitted to the hospital with a one-day history of high-grade fever, acute abdominal pain, and brownish vaginal discharge. She had no notable medical history or pregnancy-related complications. She reported having oral sex with her husband a few days before admission. Her vital signs were normal, except for a 38.2 °C fever. Physical examination revealed abdominal bloating and dark-red vaginal discharge. Her white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelet count, serum creatinine, AST, ALT, and C-reactive protein levels were 19,100/μL, 12.8 g/dL, 227,000 cells/L, 0.37 mg/dL, 15 IU/L, 9 IU/L, and 3.68 mg/dL, respectively. According to the definition of The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, intra-amniotic infection was suspected based on maternal fever, uterine tenderness, and leukocytosis [3]. After obtaining blood and vaginal cultures, intravenous ampicillin 1 g q6h and oral erythromycin 200 mg q6h were administered. Despite medical intervention, the stillbirth occurred 14 h after admission. On day 2 of admission, the vaginal discharge Gram stain revealed small Gram-negative coccobacilli with phagocytosis (Fig. 1). On day 3, H. influenzae was identified in two sets of blood and vaginal cultures using a Vitek MS matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry system (bioMérieux, France). In anticipation of ampicillin resistance, the antibiotics were switched to ceftriaxone 2 g q24h. The broth microdilution method was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentrations of H. influenzae for various antibiotics, following the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (Table 1). The susceptibility test of the H. influenzae isolates revealed ampicillin resistance and sensitivity to other antibiotics, including ceftriaxone. The patient’s condition improved rapidly after a one-week course of ceftriaxone, and she was discharged without complications nine days after her admission. She returned for a follow-up visit one week after being discharged and showed no signs of the recurrent infection.

Fig. 1.

Vaginal Gram stain upon admission. Small Gram-negative coccobacilli with leukocyte phagocytosis (arrows) are evident.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility and MIC values for H. influenzae detected in the blood culture.

| Antibiotics | Susceptibility | MIC value (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | R | ≧ 8 |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | S | 2 |

| Cefaclor | S | 4 |

| Ceftriaxone | S | ≦ 0.06 |

| Levofloxacin | S | ≦ 1 |

| Clarithromycin | I | 16 |

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

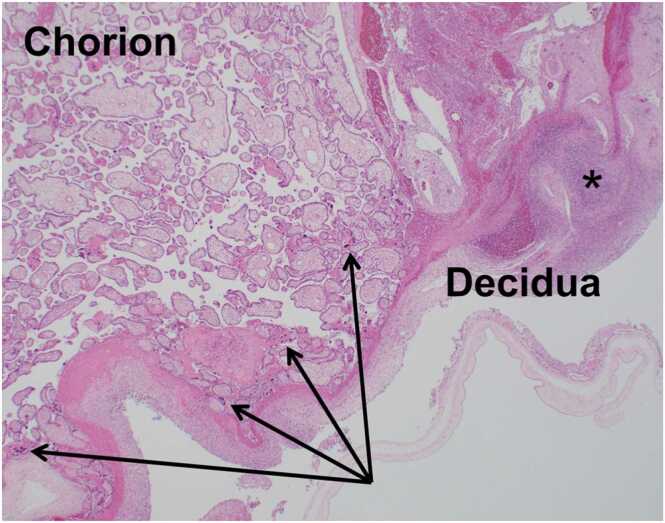

The placenta revealed chorionitis and a decidual abscess upon histopathological examination (Fig. 2). The patient was diagnosed with stage 2 acute chorioamnionitis based on these pathological findings. H. influenzae isolated from the blood culture was positive for penicillinase activity based on the Penicillinase–Cephalosporinase test (Nippon Suisan Kaisha, Ltd.) and was confirmed as NTHi using phenotypic characterization by PCR-based capsular typing [5]. Multi-locus sequence typing, performed using a previously described method, identified sequence types as ST187 [6].

Fig. 2.

Histopathological placental images. H and E staining showing diffuse neutrophil infiltration at the chorion membrane (arrows) and a decidual abscess (black asterisks), consistent with stage 2 acute chorioamnionitis.

Discussion

H. influenzae is a small Gram-negative coccobacillus that usually colonizes human respiratory mucosal surfaces and is a leading cause of respiratory infections such as bronchitis and pneumonia. It is also known to colonize the female genital tract, causing ascending invasion and critical intra-amniotic infections during pregnancy [7]. Collins et al. reported that the overall fetal and neonatal case fatality rate among pregnant women with invasive H. influenzae disease was 62.3%, and the incidence of invasive NTHi infection during pregnancy was 17-fold higher than that of their non-pregnant peers [8]. Moreover, a study in New Zealand revealed that the overall incidence of pregnancy-associated H. influenzae invasive disease was comparable to that of early-onset neonatal group B Streptococcus sepsis and higher than that of pregnancy-associated listeriosis [9]. Considering its severity and high incidence rate, it would be more appropriate to recognize H. influenzae as a threat pathogen for pregnant women.

Here, we present the case of a pregnant woman with chorioamnionitis and a septic abortion caused by ampicillin-resistant H. influenzae. The most effective antibiotic treatment for chorioamnionitis has not been established yet. The Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends ampicillin to prevent maternal and neonatal infections in the setting of premature membrane ruptures. However, no specific antibiotic regimen has been recommended for chorioamnionitis [10]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends a combination of ampicillin and gentamicin [3], even though there is limited evidence to support these recommendations [11]. Gentamicin has only modest activity against H. influenzae [12], and H. influenzae susceptibility testing is not routinely required [13]. Given the lack of efficacy and substantial adverse effects, such as nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, and difficulty maintaining appropriate blood concentrations, aminoglycosides could be avoided as a standard H. influenzae treatment.

The high rate of ampicillin resistance in H. influenzae is an unacceptable problem because ampicillin is included in the standard antibiotic regimen. Therefore, ampicillin resistance is directly linked to initial treatment failure. Approximately one-quarter of the H. influenzae isolates tested positive for β-lactamase in North America and the Asia-Pacific Rim [14]. According to the Clinical Laboratory Division of the Japan Nosocomial Infections Surveillance, the sensitivity of H. influenzae to ampicillin in Japan is only 40% [15]. Conversely, susceptibility to third-generation cephalosporins was sustained in over 95% of the cases [14], [15]. Because our patient’s H. influenzae was positive for penicillinase and resistant to ampicillin, empirical treatment with ampicillin and erythromycin might have been ineffective. In addition, our patient’s isolate was NTHi, which has been on the rise since Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccination became widely available [16]. In terms of drug resistance, NTHi was less susceptible to ampicillin than serotypeable H. influenzae [4]. Considering the susceptibility of pregnant women to H. influenzae infections and the growing rate of ampicillin resistance, broad-spectrum antibiotics such as third-generation cephalosporins might be considered for empiric antibiotic treatment of chorioamnionitis.

The risk factors for chorioamnionitis caused by H. influenzae are poorly understood. Chorioamnionitis is caused primarily by an ascending polymicrobial invasion of the lower genital tract [3]. However, H. influenzae prevalence in vaginal flora during pregnancy is reported to be extremely low [17], [18]. Given the low prevalence of H. influenzae chorioamnionitis in the genital region, a different etiology is possible. Another notable factor for intra-amniotic infection is oral sex, which is a potential route of intra-amniotic infection caused by oral pathogens [19]. The H. influenzae strain detected in our case was identified as ST187. In public databases for molecular typing and microbial genome diversity, ST187 has been isolated primarily from the head-neck region and never from the genital region [20]. Ostroaska et al. reported a case of chorioamnionitis caused by transmission of oral commensal bacteria via oral sex [21]. Because our patient reported having oral sex during her pregnancy, her chorioamnionitis could have been caused by her partner’s oral flora directly entering the vagina. The patient’s oral sex history could be a potential clue to the suspicion of H. influenzae as the causative bacterium of chorioamnionitis.

Our report has several limitations. First, we could not prove that H. influenzae was transmitted through oral sex because her husband's oral culture was unavailable. In this case, it is unclear whether H. influenzae infection was actually caused by oral sex. Second, the prevalence of chorioamnionitis caused by H. influenzae is poorly understood. Although broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as ceftriaxone, are considered empirical therapies given H. influenzae antibiotic resistance, it is unclear whether clinicians should adopt broad-spectrum treatment for all chorioamnionitis patients.

In conclusion, we reported a case of chorioamnionitis caused by ampicillin-resistant H. influenzae that led to a septic abortion. Clinicians keep in mind that orogenital sex may cause chorioamnionitis due to upper respiratory tract commensals, and the rise in ampicillin-resistant H. influenzae suggests that guideline-based antimicrobial therapy may be insufficient to treat the disease. More research into the frequency and risk factors of genital H. influenzae infection, as well as the prevalence of ampicillin-resistant H. influenzae, is needed to determine the best antibiotic strategy for chorioamnionitis.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and his family to publish this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuji Nishihara: Writing – original draft. Nobuyasu Hirai: Writing – original draft. Takahiro Sekine: Methodology (patient treatment). Nao Okuda: Methodology (patient treatment). Tomoko Nishimura: Methodology (patient treatment). Hiroyuki Fujikura: Methodology (patient treatment). Ryutaro Furukawa: Methodology (patient treatment). Natsuko Imakita: Methodology (patient treatment). Tatsuya Fukumori: Methodology (patient treatment). Taku Ogawa: Methodology (patient treatment). Yuki Suzuki: Investigation (laboratory work). Ryuichi Nakano: Investigation (laboratory work). Akiyo Nakano: Investigation (laboratory work). Hisakazu Yano: Investigation (laboratory work). Kei Kasahara: Writing – review & editing. All authors contributed to the final manuscript and to the management and administration of this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- 1.King P. Haemophilus influenzae and the lung (Haemophilus and the lung) Clin Transl Med. 2012;1:10. doi: 10.1186/2001-1326-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter M., Charles A.K., Nathan E.A., French N.P., Dickinson J.E., Darragh H., et al. Haemophilus influenzae: a potent perinatal pathogen disproportionately isolated from Indigenous women and their neonates. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;56:75–81. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Committee on Obstetric Practice Committee opinion No. 712: intrapartum management of intraamniotic infection. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e95–e101. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsang R.S.W., Shuel M., Whyte K., Hoang L., Tyrrell G., Horsman G., et al. Antibiotic susceptibility and molecular analysis of invasive Haemophilus influenzae in Canada, 2007 to 2014. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:1314–1319. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LaClaire L.L., Tondella M.L.C., Beall D.S., Noble C.A., Raghunathan P.L., Rosenstein N.E., et al. Identification of Haemophilus influenzae serotypes by standard slide agglutination serotyping and PCR-based capsule typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:393–396. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.393-396.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meats E., Feil E.J., Stringer S., Cody A.J., Goldstein R., Kroll J.S., et al. Characterization of encapsulated and noncapsulated Haemophilus influenzae and determination of phylogenetic relationships by multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1623–1636. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1623-1636.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Eldere J., Slack M.P.E., Ladhani S., Cripps A.W. Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae, an under-recognised pathogen. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:1281–1292. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70734-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins S., Ramsay M., Slack M.P., Campbell H., Flynn S., Litt D., et al. Risk of invasive Haemophilus influenzae infection during pregnancy and association with adverse fetal outcomes. JAMA. 2014;311:1125–1132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hills T., Sharpe C., Wong T., Cutfield T., Lee A., McBride S., et al. Fetal loss and preterm birth caused by intraamniotic Haemophilus influenzae infection, New Zealand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:1749–1754. doi: 10.3201/eid2809.220313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstetrics and gynecology guideline, obstetrics; 2020.

- 11.Alrowaily N., D’Souza R., Dong S., Chowdhury S., Ryu M., Ronzoni S. Determining the optimal antibiotic regimen for chorioamnionitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:818–831. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sojo-Dorado J., Rodríguez-Baño J. Gentamicin. In: Kucers’ the use of antibiotics: a clinical review of antibacterial, antifungal, antiparasitic, and antiviral drugs. 7th ed. Grayson M.L., editor. CRC Press; 2017. pp. 964–991. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; thirtieth informational supplement; M100-S32. Clin Lab Stand Inst 2022 update.

- 14.Darabi A., Hocquet D., Dowzicky M.J. Antimicrobial activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae collected globally between 2004 and 2008 as part of the tigecycline Evaluation and Surveillance Trial. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;67:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Japan nosocomial infections surveillance (JANIS). Annual open report by prefectures; 2021. 〈https://janis.mhlw.go.jp/report/open_report/2021/3/1/ken_Open_Report_202100.pdf〉, [Accessed 12 January 2023].

- 16.Whittaker R., Economopoulou A., Dias J.G., et al. Epidemiology of invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease, Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;2007–2014(23):396–404. doi: 10.3201/eid2303.161552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardines R., Daprai L., Giufrè M., Torresani E., Garlaschi M.L., Cerquetti M. Genital carriage of the genus Haemophilus in pregnancy: species distribution and antibiotic susceptibility. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:724–730. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schønheyder H., Ebbesen F., Grunnet N., Ejlertsen T. Non-capsulated Haemophilus influenzae in the genital flora of pregnant and post-puerperal women. Scand J Infect Dis. 1991;23:183–187. doi: 10.3109/00365549109023398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballini A., Cantore S., Fatone L., Montenegro V., de Vito D., Pettini F., et al. Transmission of nonviral sexually transmitted infections and oral sex. J Sex Med. 2012;9:372–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pub MLST. 〈https://pubmlst.org〉, [Accessed 12 January 2023].

- 21.Ostrowska K., Rotstein C., Thornley J., Mandell L. Pneumococcal endometritis with peritonitis: case report and review of the literature. Can J Infect Dis. 1991;2:161–164. doi: 10.1155/1991/686408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]