Abstract

Traditional medicinal plants used by local Oromo people of Tulo District in west Hararghe, Ethiopia, were investigated before people's medicinal knowledge vanishes. Data on medicinal plants and demography were obtained between November 2019 and October 2020 through semi-structured interviews, group discussion and direct guided onsite observation to elicit information from 376 non-traditional and 20 traditional medicine practitioners. Ethnobotanical indices including informant consensus factor (ICF), preference ranking (PR), fidelity level (FL), relative frequency of citation (RFG) and cultural importance (CI) were employed for the data analysis. Moreover; descriptive statistics, t-test, analysis of variance and linear regression were used to reveal the effects of socio-demographic factors on respondents' traditional medicinal knowledge. Totally 104 plants distributed among 98 genera and 55 families were enumerated for the treatment of 60 illnesses. Seventy-seven of these medicinal plants serve to treat human ailments, whereas 11 and 16 of them were used for livestock and for both, respectively. Asteraceae and Lamiaceae were species rich families. Leaves were the most frequently (41.53%) reported structures for the preparation of remedies. Crushing was the principal approach (34.50%) of remedy preparation. Oral administration was frequently (66.08%) used route of application. The highest ICF was observed for swelling and hemorrhoid (0.90) category. Metabolic and degenerative as well as other ailment categories had the least ICF values. About 66% of medicinal plants had FL value of 100%. In PR, G. abyssinica was ranked first to treat cough. RFC values varied from 0.03 to 0.18 with the highest record for Salvia nilotica (0.18) followed by Lepidium sativum, Rydingia integrifolia and Nigella sativa each with 0.16; Euphorbia abyssinica and Asplenium monanthes each with 0.15. Extensive use of land for agricultural purpose was key threat to medicinal plant of Tulo District. All the tested socio-demographic features except religion significantly (P < 0.05) affected the traditional knowledge on medicinal plants possessed by the study population. The results of this study reveals that the people of Tulo District rely on traditional medicine of plant origin, and their indigenous knowledge is instrumental to exploit the most potential plants for further validation. Therefore, the medicinal plant species wealth of the study site and the associated indigenous knowledge need to be preserved.

Keywords: Ethnobotany, Ethnobotanical indices, Traditional knowledge, Medicinal plants, Tulo district

1. Introduction

Since ancient times, local communities inhabiting a given place have developed knowledge on the use and management of plants of their surroundings [1]. Around the globe, local communities possess exclusive knowledge related to plant resources that they rely on for food, medicine and other uses [2]. To explore their expertise on utilization of plants for different purposes, scientific ethnobotanical investigations are of paramount importance [3]. According to World Health Organization (WHO) nearly 60% of people in the globe utilize traditional medicine for treating illnesses, and besides modern medication, up to 80% of the population living in Africa rely on traditional medicinal plants for their healthcare [4]. Their dependence on traditional medicinal plants is mainly due to poor economic potential to afford to modern medication and limited number of modern health facilities especially in remote rural areas [5]. However, unless documented, medicinal plants and the indigenous knowledge associated to them may vanish in the future through various anthropogenic factors that are exacerbated by human population expansion. In this regard, ethnobotanical studies help to record and preserve information related to medicinal plants used traditionally by indigenous people.

The ethnic group dwelling in Tulo District is Oromo, the dominant ethnic community in Ethiopia [6]. This indigenous ethnic community has been practicing the Gada System (social institution) that sets guiding principles to help the local people preserve their socio-economic, political and cultural systems [5]. Previous studies [5,7] show Oromo people's reliance on the natural resources, in particular plant wealth; for food, shelter, ethnomedicine, firewood and religious purposes. Particularly, they have acquired a rich traditional medicinal knowledge on using plants of their vicinity to solve health problems [5]. Nevertheless, plant diversity and the local traditional knowledge related to them are generally under threat in Ethiopia [8,9]. Albeit a lot of reports on ethnomedicinal studies of Oromo people in Oromia region, Ethiopia [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]] are available, such studies in east and west Hararghe zones are scanty with only few available studies [18,19]. Thus, this study aimed at the identification and documentation of traditional medicinal plants and the expertise of the local people on their utilization as remedies for humans and livestock ailments in Tulo District, west Hararghe, Oromia region, Ethiopia. This study also assessed the key anthropogenic activities that put medicinal plants of the study area at risk. The novelty of this work is that the study district has never been explored from ethnobotanical point of view and the identified medicinal plant species of the study area were subjected to comprehensive quantitative analysis to figure out elite plants for medicinal purposes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study site and demography

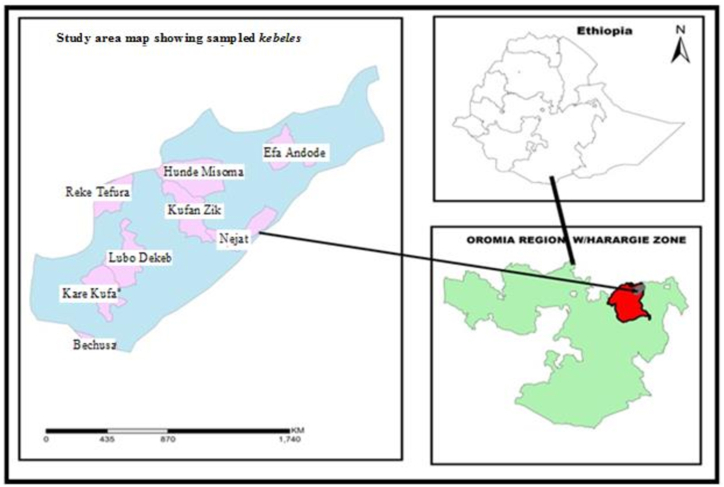

This study was carried out in Tulo District, which is found in west Hararghe zone of Oromia region at a distance of 360 km away from the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa (Fig. 1). The altitude of the district extends from 1631 to 2800 m above sea level. About 56.67% of this District is Midland (1600–2300 m above sea level), whereas 43.33% of it is Highland (>2300 m above sea level). Totally, 174,215 people (85,888 males and 88,327 females) live in the District. About 18,087 people of the District are urban dwellers, whereas 156,128 are rural dwelling [20]. The main language of the indigenous people is Afaan Oromo. In terms of religion, 90% of the people are Muslims while 10% are Christians. Under Tulo District, there are 33 Kebeles (Kebele is the lowest administration unit) of which 30 are rural and 3 are urban Kebeles. Totally, the District has 5 health centers, 1 hospital, 2 higher clinics, 30 health posts, 6 private drug vendors, 1 drug store, 5 small clinics, 42 elementary (1–8 grades) schools and 3 high schools.

Fig. 1.

Map of the study area (Source GIS Software).

The mean yearly temperature of the district is 26 °C, whereas that of rainfall is 1700 mm. (Tulo District Agricultural and Natural Resource Development Office [TDANRDO], 2018, unpublished data). In the area, most of the people engage in mixed subsistence agriculture, i.e., rearing livestock and cultivating cereals mainly maize and sorghum; tuber crops particularly sweet potato and potato; vegetables like onion and cabbage; and fruits such as lemon, banana, papaya and orange. The major income generating cultivated cash crops are coffee (Coffea arabica L.) and haricot bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). A large number of the populace in the District rely on traditional medicine of plant origin for treating human and livestock ailments to shun using expensive modern drugs.

2.2. Determination of sample size

Totally the number of households of the eight Kebeles considered for this study was 41,634. Hence, we used the formula of Yemane [21] defined below to get the representative sample size.

Where ‘n’, represents the required representative sample size; ‘N’, represents the entire population of the studied Kebeles (=41,634); ‘e’, represents margin of error, which is 5%; and 1 = the probability of event occurring.

Thus, the representative sample was:

Thus, preceding ethnobotanical data collection, a total of 396 informants with age range of 21–80 years were considered for this study. Among this total respondents, 376 were randomly sampled ordinary people that do not work as traditional healers. However, 20 individuals were known for their experience as traditional healers (herbalists) and selected purposively as key informants [22].

2.3. Sampling procedure and collection of data

Scouting was done between October and November 2019 to choose 8 study Kebeles. Three Kebeles: Efa Andode (2192–2700 m above sea level), Hunde Misoma (2293–2680 m above sea level) and Kare Kufa (2356–2800 m above sea level) from high-land areas and five Kebeles: Reke Tefura (1701–1987 m above sea level), Lubo Dekeb (1743–1984 m above sea level), Kufan Zik (1892–1965 m above sea level), Nejeta (1800–1902 m above sea level) and Buchesa (1631–1848 m above sea level) from mid-land areas were purposively selected to cover different agro-ecologies.

Prior to data collection, permission was obtained from Tulo District Administrative Office. Respondents were then approached and informed that the purpose of the study was only for education, but not for any other purpose. Thereafter they gave us oral consent to provide information we sought. Then after, ethnobotanical data were gathered between November 2019 and October 2020 by adapting the guidelines on ethnopharmacological studies [[23], [24], [25]]. Ethnobotanical techniques employed included interviews, group discussion and direct guided onsite observation to obtain information related to respondents' socio-demographic status, their traditional experience on utilization of medicinal plants, and factors threatening medicinal plants and conservation efforts being made to preserve medicinal plants. Interview was conducted with individuals separately to get socio-demographic (gender, educational status, age, marital status, religion and occupation) data, local names of medicinal plants, type of the disease they cure, plant part for remedy preparation, approaches to prepare remedies and modes of administration of remedies. Questions for interview were developed first using English language and later converted to native Afaan Oromo language of the indigenous people. Respondents were explained about the purpose of the survey and consent was obtained from the men to get information from female respondents too. Accordingly, females were interviewed near home gardens and the surrounding vegetation. Group discussion was carried out with traditional healers as per the arranged checklist questions and onsite field observations were made with them to observe medicinal plants' habits, their habitat and collection of medicinal plants’ specimens.

2.4. Collection and identification of ethnomedicinal plants

Voucher specimens of ethnomedicinal plants were collected, pressed, dried, mounted and identified by using Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea [26,27], other literatures [28] and by comparing with authentic specimens found in the herbarium of Haramaya University. After identification, the specimens were kept in the Herbarium of Haramaya University.

2.5. Data analysis

Descriptive statistical method was used to analyze qualitative data. Ethnobotanical indices viz. Informant consensus factor (ICF), preference ranking (PR), fidelity level (FL), the relative frequency of citation (RFC) and cultural importance (CI) were also computed to determine the most locally important species.

Informant consensus factor is a value that shows extent of agreement between people on the medicinal values of plants for the cited illness. In order to calculate this index, we first broadly classified the reported ailments into 8 categories (Table 2). ICF value was determined as follows:

Where, ‘nur’ stands for the number of use citations for each ailment, ‘nt’ stands for the number of species used for the ailment category [29,30].

Table 2.

Informant consensus factor (ICF) for eight disease categories.

| No | Ailment category | Nt | Nur | ICF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Body swelling and hemorrhoid | 9 | 81 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Gastrointestinal diseases and Parasitic infections (Stomach ache, bloating, Dyspepsia, Vomiting, Abdominal pain, Diarrhea, Gastritis, Constipation, Heart burn, Intestinal parasite including Ascariasis, Taeniasis and Amoebiasis) | 21 | 108 | 0.81 |

| 3 | Dermatology and Sensory organ diseases (Wound, Ringworm, Skin rash, Skin infection, Wart, Scabies, Dandruff, Eczema, Leech infestation, Eye disease, Ear disease, Nasal bleeding, Nerve problem, Toothache, Gum bleeding) | 32 | 150 | 0.79 |

| 4 | Febrile illness and related diseases (Febrile, Fever, Typhoid, Anemia, Headache, Evil eye, Stabbing pain) | 17 | 72 | 0.77 |

| 5 | Respiratory system and pharyngeal related diseases (Cough, Common cold, Asthma, Tonsillitis) | 20 | 65 | 0.69 |

| 6 | Urogenital related diseases (Gonorrhea, Orchitis, Impotence, Uterus problem, Urine retention, Placental retention) | 8 | 17 | 0.56 |

| 7 | Metabolic and degenerative diseases (Jaundice, Hypertension, Heart problem, Diabetes, Breast cancer, Malaria, Kidney disease, Gallstone, Anemia) | 18 | 32 | 0.45 |

| 8 | Others (Rabies, Anthrax, Black leg, Snake poisoning, Spider poisoning) | 11 | 18 | 0.41 |

Note: ‘Nur’ denotes number of use citations for category; ‘Nt’ denotes number of medicinal plant species cited for a disease category.

Preference ranking was done to rank six plants reported as a cure for cough. For this, ten key informants who mentioned the six plants as a cure for cough were randomly picked to do the ranking exercise depending on the relative potential of medicinal plants to cure cough. Those 6 mentioned plants were then given to individual respondents so as to rank them by giving the highest value (6) to the medicinal plant they believe is most effective and lowest value (1) for least effective one, and any value between 6 and 1 for the remaining plants based on their curative potential. The assigned values of each plant species were summed and then ranked based on the total score.

Fidelity level which shows a tendency of using a certain plant for curing single disease was computed by adopting the equation used by Ref. [30] as follows:

‘FL’, represents fidelity level; ‘Np’, represents the number of respondents who make use of a plant species for treating an illness; ‘N’, represents the number of respondents that use the plants as a medicine to treat any given disease.

The Relative frequency of citation was calculated by following the formula indicated by Refs. [[31], [32], [33]] as follows.

‘FC’, represents the number of respondents who cited a plant for its medicinal value, whereas ‘N’, is the total number of respondents that took part in the study.

The cultural importance (CI) was computed following the approaches of Refs. [31,34].

In order to compare medicinal knowledge of the different socio-demographic groups, t-test and analysis of variance were done. Regression analysis was also checked to detect socio-demographic factors that predicted traditional medicinal knowledge. In all cases, SPSS version 16 statistical software was used to analyze the data and statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Ranking was also made to prioritize the most important human activities that put medicinal plants in danger. For this, 10 key respondents were first requested to free list all possible anthropogenic causes that jeopardize medicinal plants and give the maximum value (5) for what they claim as the highest threatening factor and the minimum value (1) for the lowest threatening factor, and ordered the remaining ones according to their level of importance.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Ethnomedicinal plants recorded

Totally 104 medicinal plant species that belong to 98 genera and 55 families were documented from Tulo District. These plants were reported to treat about 60 different illnesses of humans and livestock. This number implies that the study site is the abode of huge repository of flora and rich expertise of the locals on medicinal plants. This suggests the wide utilization of traditional medicine of plant origin by the local community of Tulo District. The majority (78 plant species) was enumerated to treat various human health problems, whereas 10 and 16 plant species were used to cure livestock and ailments of both (Table 1), respectively.

Table 1.

Enumeration of ethnomedicinal plants used for the treatment of ailments of humans and livestock.

| Ethnobotanical Indices |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species name | Family | V.No. | V. Name | Ht | Hbt | Part | Ailments | R | AP | FL (%) | NU | CI | FC | RFC |

| Acacia abyssinica Hochst. ex Benth. | Fabaceae | MB101 | Laaftoo | T | W | Fruit | Orchitis | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 27 | 0.07 |

| Acokanthera schimperi (A.DC.) Schweinf. | Apocynaceae | MB18 | Qaraaru | S | W | Root | Gonorrhea | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 31 | 0.08 |

| Afrocarpus falcatus (Thunb.) | Podocarpaceae | MB97 | Birbirsa | T | W | Bark | Evil eye | N | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 30 | 0.08 |

| C·N.Page | ||||||||||||||

| **Agave sisalana Perrine ex Engelm. | Agavaceae | MB52 | Algee | S | W | Root | Gum bleeding | O | B | 56 | 2 | 0.005 | 34 | 0.09 |

| Stem | Black leg | F | ||||||||||||

| Allium cepa L. | Alliaceae | MB1 |

Shunkurtii Diimaa |

H | Cu | Bulb | Heart burn | O | F | 62.8 | 3 | 0.008 | 35 | 0.09 |

| Stabbing pain | ||||||||||||||

| Impotence | ||||||||||||||

| **Allium sativum L. | Alliaceae | MB8 | Qullubbii adii | H | Cu | Bulb | Febrile illness | O | B | 54.7 | 4 | 0.010 | 53 | 0.13 |

| Bloating | ||||||||||||||

| Malaria | ||||||||||||||

| Stomach ache | ||||||||||||||

| Aloe trichosantha A.Berger | Aloaceae | MB56 | Hargeysa | S | W | Leaf | Diabetes | O | F | 56.4 | 6 | 0.010 | 39 | 0.09 |

| Hypertension | ||||||||||||||

| Sap | Wound | D | ||||||||||||

| Heart burn | O | |||||||||||||

| Headache | ||||||||||||||

| Snake poisoning | ||||||||||||||

| *Ampelocissus bombycina (Bak.) Planch | Vitaceae | MB103 | Dubbaa jinnii | C | W | Fruit | Anthrax | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 33 | 0.08 |

| Anthemis tigreenisJ. Gay ex A.Rich | Asteraceae | MB2 | Zarnab | H | W | Seed | Cough | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 40 | 0,10 |

| Artemisia afraJacq. ex Willd. | Asteraceae | MB98 | Sakayyee adii | S | W | Leaf | Nerve problem | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 19 | 0.05 |

| Asplenium monanthes L. | Aspleniaceae | MB46 | Digaloo | M | W | Leaf | Fever | O | B | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 61 | 0.15 |

| makannisaa | ||||||||||||||

| Bersama abyssinica Fresen. | Melianthaceae | MB28 | Qillisaa | T | W | Fruit | Ascariasis | O | F | 63.8 | 2 | 0.005 | 36 | 0.09 |

| Taeniasis | ||||||||||||||

| Bidens pilosa L. | Asteraceae | MB48 | Xiyyee | H | W | Leaf | Wound | D | F | 70.5 | 3 | 0.008 | 51 | 0.13 |

| Nasal bleeding | N | |||||||||||||

| Febrile illness | O | |||||||||||||

| Brassica carinata A.Braun | Brassicaceae | MB19 | Midhaan raafuu | H | Cu | Seed | Uterus problem | O | Dr | 51.7 | 4 | 0.010 | 29 | 0.07 |

| Dyspepsia | ||||||||||||||

| Typhoid | ||||||||||||||

| Malaria | ||||||||||||||

| Brassica nigra (L.) Koch | Brassicaceae | MB11 | Sinaaficii | H | Cu | Seed | Common cold | O | Dr | 55.2 | 5 | 0.013 | 38 | 0.09 |

| Asthma | ||||||||||||||

| Stomach ache | ||||||||||||||

| Intestinal parasite | ||||||||||||||

| Wound | D | |||||||||||||

| Caesalpinia decapetala (Roth) Alston | Fabaceae | MB58 | Qajimaa | S | W | Seed | Tonsillitis | O | F | 45.7 | 3 | 0.008 | 35 | 0,09 |

| Root | Amoebiasis | |||||||||||||

| Leaf | Body swelling | D | ||||||||||||

| Calpurnia aurea (Aiton) Benth. | Fabaceae | MB15 | Ceekaa | S | W | Root | Vomiting | O | F | 65.7 | 4 | 0.010 | 35 | 0.09 |

| Leaf | Jaundice | |||||||||||||

| Snake poisoning | ||||||||||||||

| Amoebiasis | ||||||||||||||

| **Capsicum annum L. | Solanaceae | MB37 | Mixmixaa | H | Cu | Fruit | Leech infestation | D | B | 70 | 3 | 0.008 | 50 | 0.13 |

| Malaria | O | F | ||||||||||||

| Leaf | Dyspepsia | B | ||||||||||||

| Carica papaya L. | Caricaceae | MB50 | Paapaayaa | T | Cu | Root | Malaria | O | F | 64.1 | 2 | 0.005 | 39 | 0.09 |

| Seed | Intestinal parasite | Dr | ||||||||||||

| Carissa spinarum L. | Apocynaceae | MB26 | Hagamsa | S | W | Root | Wound | D | Dr | 51.2 | 2 | 0.005 | 39 | 0.09 |

| Body swelling | ||||||||||||||

| Carthamus tinctorius L. | Asteraceae | MB51 | Suufii | H | Cu | Seed | Cough | O | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 32 | 0.08 |

| Casimiroa edulis La Llave | Rutaceae | MB29 | Habuqqaa | T | Cu | Fruit | Kidney disease | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 40 | 0.10 |

| Catha edulis (Vahl) Endl. | Celastraceae | MB6 | Jimaa | S/T | Cu | Leaf | Common cold | O | B | 67.3 | 2 | 0.005 | 46 | 0.12 |

| Asthma | ||||||||||||||

| Cissampelos mucronata A.Rich. | Menispermaceae | MB80 | Baal-tokkee | C | W | Root | Dyspepsia | O | F | 77.7 | 2 | 0.005 | 45 | 0.11 |

| Snake poisoning | D | |||||||||||||

| Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck | Rutaceae | MB3 | Xuuxxoo | S | Cu | Fruit | Abdominal pain | O | F | 60.7 | 4 | 0.010 | 51 | 0.13 |

| Vomiting | ||||||||||||||

| Gum bleeding | ||||||||||||||

| Ringworm | D | |||||||||||||

| Citrus paradise Macfad. | Rutaceae | MB81 | Komxaaxxee | S | Cu | Fruit | Hypertension | O | F | 45.4 | 2 | 0.005 | 33 | 0.08 |

| Ringworm | ||||||||||||||

| Commelina benghalensis L. | Commelinaceae | MB13 | Hoolagabbis | H | W | Leaf | Ringworm | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 32 | 0.08 |

| Coriandrum sativum L. | Apiaceae | MB5 | Shukaar | H | Cu | Seed | Stomach ache | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 41 | 0.10 |

| Cordia africana Lam. | Boraginaceae | MB41 | Wadessa | T | W | Leaf | Eczema | D | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 32 | 0.08 |

| Crinum abyssinicum Hochst. ex A.Rich. | Amaryllidaceae | MB2 | Qullubbii | H | W | Bulb | Cough | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 39 | 0.09 |

| waraabeessaa | ||||||||||||||

| Croton macrostachyus Hochst. Ex Delile | Euphorbiaceae | MB17 | Bakkanisaa | T | W | Leaf | Ringworm | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 55 | 0.14 |

| Cucumis ficifolius A.Rich. | Cucurbitaceae | MB62 | Yemidir imbuway | H | W | Leaf | Common cold | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 43 | 0.11 |

| Cucurbita pepo L. | Cucurbitaceae | MB77 | Dubbaa | C | Cu | Seed | Headache | O | Dr | 94 | 2 | 0.005 | 49 | 0.12 |

| Fruit | Taeniasis | |||||||||||||

| *Cussonia ostinii Chiov. | Araliaceae | MB71 | Hafratu | T | W | Leaf | Leech infestation | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 35 | 0.09 |

| Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf. | Poaceae | MB9 | Xajii saar | H | W | Root | Evil eye | N | Dr | 63.6 | 3 | 0.008 | 33 | 0.08 |

| Leaf | Gallstone | O | ||||||||||||

| Root | Diarrhea | F | ||||||||||||

| **Datura stramonium L. | Solanaceae | MB73 | Banjii | H | W | Leaf | Wound | O | F | 36.1 | 4 | 0.010 | 36 | 0.09 |

| Seed | Toothache | |||||||||||||

| Leaf | Rabies | |||||||||||||

| Root | Skin rash | D | ||||||||||||

| Daucus carota L. | Apiaceae | MB14 | Kaaroota | H | Cu | Root | Kidney disease | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 30 | 0.08 |

| Digitaria velutina (Forssk.) P.Beauv | Poaceae | MB104 | Sarduu | H | W | Leaf | Wound | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 38 | 0.09 |

| Dodonaea viscosa subsp. angustifolia (L.f.) J.G.West | Sapindaceae | MB89 | Ittacha | S | W | Leaf | Eczema | D | Dr | 35.2 | 3 | 0.008 | 34 | 0.09 |

| Leaf | Body swelling | F | ||||||||||||

| Stem | Gum bleeding | O | ||||||||||||

| Dovyalis abyssinica (A.Rich.) Warb. | Salicaceae | MB20 | Koshimoo | S | W | Leaf | Body swelling | D | F | 53.3 | 2 | 0.005 | 30 | 0.08 |

| Seed | Hemorrhoid | |||||||||||||

| Echinops kebericho Mesfin | Asteraceae | MB75 | Qabarichoo | H | W | Root | Evil eye | N | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 30 | 0.08 |

| Ehretia cymosa Thonn | Boraginaceae | MB93 | Ulaagaa | T | W | Leaf | Stabbing pain | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 17 | 0.04 |

| *Erythrina burana Chiov. | Fabaceae | MB42 | Walensuu | T | W | Leaf | Wound | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 21 | 0.05 |

| Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | Myrtaceae | MB47 | Baargamoo adii | T | W | Leaf | Common cold | N | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 32 | 0.08 |

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. | Myrtaceae | MB23 | Baargamoo diimaa | T | W | Leaf | Stomach ache | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 29 | 0.07 |

| Euphorbia abyssinica J.F.Gmel. | Euphorbiaceae | MB83 | Hadaamii | T | W | Sap | Gastritis | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 58 | 0.15 |

| Euphorbia tirucalli L. | Euphorbiaceae | MB35 | Qinciba | S | W | Latex | Wart | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 33 | 0.08 |

| Ficus vasta Forssk. | Moraceae | MB24 | Qilxuu | T | W | Leaf | Ear disease | Er | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 18 | 0.05 |

| **Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Apiaceae | MB4 | Kamoona | H | Cu | Root | Urine retention | O | F | 72 | 2 | 0.005 | 43 | 0.11 |

| Placental retention | ||||||||||||||

| Gossypium barbadense L. | Malvaceae | MB39 | Jirbbii bukkee | S | W | Seed | Skin rash | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 31 | 0.08 |

| Guizotia abyssinica (L.f.) Cass. | Asteraceae | MB84 | Nuugii | H | Cu | Seed | Cough | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 56 | 0.14 |

| Hagenia abyssinica (Bruce ex Steud) J.F.Gmel. | Rosaceae | MB65 | Heexoo | T | W | Flowers, Seed | Intestinal parasite | O | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 42 | 0.11 |

| Juniperus procera Hochst. ex. Endl. | Cupressaceae | MB34 | Gatiraa habashaa | T | W | Seed | Uterus problem | O | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 37 | 0.09 |

| Justicia schimperiana (Hochst. Ex Nees) T. Anderson | Acanthaceae | MB85 | Dhumugaa | S | W | Root | Jaundice | O | Dr | 48.7 | 3 | 0.008 | 39 | 0.09 |

| Leaf | Intestinal parasite | B | ||||||||||||

| Root | Typhoid | |||||||||||||

| Kalanchoe marmorata Baker | Crassulaceae | MB59 | Phiphii | H | W | Leaf | Ear disease | Er | B | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 23 | 0.06 |

| **Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. | Cucurbitaceae | MB67 | Buqqee | C | W | Leaf | Ear disease | Er | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 36 | 0.09 |

| **Lawsonia inermis L. | Lythraceae | MB82 | Hinnaa | S | W | Leaf | Diarrhea | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | ||

| Leonotis ocymifolia (Burm.f.) Iwarsson. | Lamiaceae | MB32 | Raaskimir | S | W | Leaf | Cough | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 56 | 0.14 |

| **Lepidium sativum L. | Brassicaceae | MB43 | Shifuu | H | Cu | Seed | Bloating | O | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 65 | 0.16 |

| **Leucas stachydiformis (Benth.) Hochst. Ex Briq. | Lamiaceae | MB44 | Mukaroo | H | W | Leaf | Spider poison | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 57 | 0.14 |

| Linum usitatissimum L. | Linaceae | MB33 | Talbaa | H | Cu | Seed | Constipation | O | F | 65 | 2 | 0.005 | 43 | 0.11 |

| Gastritis | Dr | |||||||||||||

| Lippia adoensis Hochst. | Verbenaceae | MB44 | Sukee | S | W | Leaf | Skin infection | D | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 49 | 0.12 |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. | Solanaceae | MB12 | Timaatim | H | Cu | Leaf | Skin rash | D | Dr | 64.7 | 2 | 0.005 | 34 | 0.09 |

| Fruit | Anemia | O | F | |||||||||||

| **Melia azedarach L. | Meliaceae | MB45 | Kiniinzaaf | T | W | Leaf | Intestinal parasite | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 42 | 0.10 |

| Mentha aquatica L. | Lamiaceae | MB30 | Naanaa | H | Cu | Leaf | Cough | O | F | 85.9 | 2 | 0.005 | 57 | 0.14 |

| Common cold | ||||||||||||||

| **Mimusops kummel Bruce ex A.DC. | Sapotaceae | MB32 | Burris | S | W | Leaf | Body swelling | O | B | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 30 | 0.08 |

| Mirabilis jalapa L. | Nyctaginaceae | MB60 | Harmal | H | W | Root | Breast cancer | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 42 | 0.10 |

| *Momordica charantia L. | Cucurbitaceae | MB87 | Mukaloonii | C | W | Leaf | Bloating | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 19 | 0.05 |

| Moringa oleifera Lam. | Moringaceae | MB95 | Shiferaaw | T | Cu | Leaf | Hypertension | O | F | 45.7 | 2 | 0.005 | 35 | 0.09 |

| Stabbing pain | ||||||||||||||

| Musa paradisiaca L. | Musaceae | MB91 | Muuza | H | Cu | Leaf | Snake poisoning | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 34 | 0.09 |

| Myrtus communis L. | Myrtaceae | MB85 | Adas | S | W | Leaf | Dandruff | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 30 | 0.08 |

| Myrsine africana L. | Myrsinaceae | MB72 | Qacuu/qacamoo | S | W | Fruit | Taeniasis | O | Dr | 69.2 | 2 | 0.005 | 52 | 0.13 |

| Seed | Ascariasis | F | ||||||||||||

| *Nicotiana tabacum L. | Solanaceae | MB31 | Timboo | H | Cu | Leaf | Leech infestation | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 37 | 0.09 |

| Nigella sativa L. | Ranunculaceae | MB38 | Habasoodaa gurraatii | H | Cu | Seed | Common cold | O | Dr | 51.6 | 4 | 0.010 | 62 | 0.16 |

| Asthma | ||||||||||||||

| Stabbing pain | ||||||||||||||

| Headache | N | |||||||||||||

| Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst. ex Benth. | Lamiaceae | MB49 | Daamaakasediimaa | S | Cu | Leaf | Common cold | N | Dr | 89 | 4 | 0.010 | 54 | 0.14 |

| Febrile Illness | O | F | ||||||||||||

| Eye disease | E | |||||||||||||

| Fever | O | |||||||||||||

| Olea europaea L. | Oleaceae | MB99 | Ejarsa | T | W | Leaf | Asthma | N | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 11 | 0.03 |

| Parthenium hysterophorusL. | Asteraceae | MB70 | Faramsiis | H | W | Leaf | Hemorrhoid | D | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 39 | 0.09 |

| *Phytolacca dodecandra L'Hér. | Phytolaccaceae | MB79 | Handoode | S | W | Root | Intestinal parasite | O | F | 40 | 2 | 0.005 | 25 | 0.06 |

| Wound | D | |||||||||||||

| Plumbago zeylanica L. | Plumbaginaceae | MB79 | Marxas | H | W | Leaf | Heart problem | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 53 | 0.13 |

| Portulaca oleracea L. | Portulacaceae | MB74 | Mararree | H | W | Leaf | Eczema | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 24 | 0.06 |

| *Premna schimperi Engl. | Lamiaceae | MB94 | Urgessaa | S | W | Leaf | Body swelling | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 41 | 0.10 |

| Psidium guajava L. | Myrtaceae | MB55 | Zaytuna | T | Cu | Leaf | Kidney stone | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 38 | 0.09 |

| Punica granatum L. | Lythraceae | MB66 | Rumaana | S | Cu | Leaf | Gastritis | O | F | 37.9 | 2 | 0.005 | 29 | 0.07 |

| Fruit | Gum bleeding | |||||||||||||

| Raphanus raphanistrum L. | Brassicaceae | MB86 | Raafuu shimbirroo | H | W | Seed | Impotence | O | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 26 | 0.07 |

| Rhamnus prinoides L'Hér. | Rhamnaceae | MB92 | Geeshoo | S | Cu | Leaf | Tonsillitis | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 51 | 0.13 |

| Rhus ruspoli Engl. | Anacardiaceae | MB57 | Xaaxeesaa | S | W | Leaf | Body swelling | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 40 | 0.10 |

| *Ricinus communis L. | Euphorbiaceae | MB53 | Qobboo | S | W | Fruit | Anthrax | O | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 31 | 0.08 |

| Rotheca myricoides (Hochst.) Steane & Mabb. | Lamiaceae | MB90 | Misrichii | S | W | Stem | Toothache | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 19 | 0.05 |

| **Rumex nepalensis Spreng. | Polygonaceae | MB21 | Mucharraab | H | W | Leaf | Body swelling | D | F | 71.4 | 3 | 0.008 | 42 | 0.11 |

| Root | Breast cancer | |||||||||||||

| Snake poisoning | O | |||||||||||||

| Rumex nervosus Vahl | Polygonaceae | MB68 | Dhangagoo | S | W | Leaf | Body swelling | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 38 | 0.09 |

| Ruta graveolens L. | Rutaceae | MB100 | Xalataam | H | Cu | Fruit | Hypertension | O | F | 61.1 | 2 | 0.005 | 36 | 0.09 |

| Diabetes | ||||||||||||||

| Rydingia integrifolia (Benth.) Scheen & V.A. Albert | Lamiaceae | MB54 | Xuunjitii | S | W | Leaf | Headache | N | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 64 | 0.16 |

| **Salvia nilotica Juss. Ex Jacq. | Lamiaceae | MB27 | Hulgab | S | W | Root | Wound | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 70 | 0.18 |

| Solanum incanum L. | Solanaceae | MB76 | Hiddii | S | W | Fruit | Scabies | D | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 26 | 0.07 |

| *Silene macrosolen Stued. ex A.Rich | Caryophyllaceae | MB36 | Liqii | H | W | Root | Rabies | O | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 28 | 0.07 |

| Sphaeranthus suaveolens (Forssk.) DC. | Asteraceae | MB63 | Raashedii | H | W | Leaf | Headache | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 25 | 0.06 |

| **Tamarindus indicus L. | Fabaceae | MB107 | Rooqaa | T | W | Root | Gastritis | O | B | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 35 | 0.09 |

| Thymus schimperi Ronniger | Lamiaceae | MB7 | Xoosinyoo | H | Cu | Leaf | Hypertension | O | B | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 55 | 0.14 |

| Urtica simensis Hochst. Ex A.Rich | Urticaceae | MB22 | Doobbii gabaabduu | H | W | Leaf | Impotence | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 32 | 0.08 |

| *Verbascum sinaiticum Benth. | Scrophulariaceae | MB69 | Gurra harree | H | W | Root | Anthrax | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 39 | 0.09 |

| Verbena officinalis L. | Verbenaceae | MB102 | Mukalaagaa | H | W | Leaf | Tonsillitis | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 35 | 0.09 |

| **Vernonia amygdalina Del. | Asteraceae | MB10 | Obichaa | T | W | Root | Intestinal parasite | O | F | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 43 | 0.11 |

| **Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal | Solanaceae | MB40 | Hidda budee | S | W | Leaf | Evil eye | N | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 57 | 0.14 |

| Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Zingiberaceae | MB16 | Zanjabil | H | Cu | Rhizome | Cough | O | Dr | 100 | 1 | 0.003 | 37 | 0.09 |

Note: ‘*’ represents plants are used for livestock's diseases, ‘**’ is for both humans' and livestock's diseases, whereas plants with no asterisk are used to treat humans' ailments only. V. No. = Voucher Number; V. Name = Vernacular name; Ht = Habit (H=Herb, C=Climber, S=Shrub.

T = tree and M = Mistletoes); Hbt = Habitat (W =Wild, Cu=Cultivated); AP = Approaches of preparation (F=Fresh, Dr = Dried and B=Both); R = Route of Administration (O=Oral, N=Nasal, D = Dermal, Er = Ear, E = Eye).

Asteraceae and Lamiaceae, each being represented by 9 species were “the dominant families” followed by Solanaceae (6 spp); Fabaceae (5 spp); Cucurbitaceae, Brassicaceae, Rutaceae, Euphorbiaceae and Myrtaceae (4 spp each); Apiaceae (3 spp); Boraginaceae, Poaceae, Verbenaceae, Alliaceae, Polygonaceae, Apocynaceae and Lythraceae had 2 species each. The rest 38 families had one species each. The abundance of medicinal plant species under Asteraceae and Lamiaceae families may be ascribed to their cosmopolitan distribution [35]. Members of family Asteraceae and Lamiaceae were reported for their wider use in traditional medicine to treat various ailments in Tulo District, which could be ascribed to the occurrence of diverse bio-active constituents [36,37]. Species under Lamiaceae family are known to possess a wide spectrum of plants with essential oil composition that have use in cosmetic, perfume and pharmaceutical industries [38], and have pharmacologically important compounds such as terpenoids, flavonoids, phenolics and alkaloids [[39], [40], [41]]. Species under the Asteraceae family have been found to contain various components such as sesquiterpenoids, diterpenoids, phenols and flavonoids with a variety of biological activities [[42], [43], [44]]. Reports have also been found on the high medicinal usage of both families in Ethiopia [9,[45], [46], [47], [48], [49]].

3.2. Life-form, habitat and parts of ethnomedicinal plants used

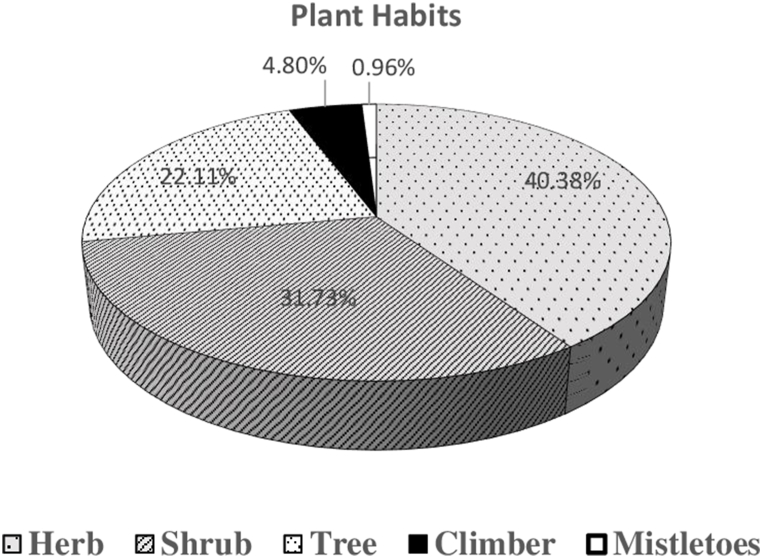

Most of the documented medicinal plants were herbs followed by shrubs, trees, climbers and mistletoes (Fig. 2). This dominance of herbs and shrubs may be due to their rapid widespread growth [50]. Previous reports [16,51,52] from Ethiopia reiterated the results obtained in our study. The high usage of herbs for therapeutic purpose was also reported by Ref. [53].

Fig. 2.

Life-forms of ethnomedicinal plants.

Most (73) of the plant species were harvested from wild environment, and a few (31) of them were cultivated. Our result was validated by other similar works [[54], [55], [56]]. This infers that majority of the medicinal plants in Tulo District are not under human management and are facing any anthropogenic and natural disturbances.

People native to the current study District make use of different parts of medicinal plants to treat humans' and livestock's ailments. Nevertheless, leaf was the most widely (56.73%) reported plant organ followed by root (22.11%), seed (18.27%), fruit (13.46%), bulb (2.88%), stem (2.88%), sap (1.92%), latex (0.96%) and rhizome (0.96%). Leaves have been reported as vital reservoirs of most bioactive compounds like alkaloids, phenolics and terpenoids [57]. High reliance on leaves for remedy preparations was reported previously by different researchers in Ethiopia [8,58,59]. More use of leaves than other plant parts reduces the risk of losing medicinal plants [[60], [61], [62]].

3.3. Approaches of remedy preparation and administration

Local people of Tulo District prepare remedies from medicinal plants while in fresh or dried form or both. Most reported form, however, was fresh harvest (73.08%), whereas about 25.96% medicinal plants were used in dry form. On the other hand, for 9.61% of medicinal plant parts, either freshly harvested or in dry form is possible to prepare the remedies. Reports show that the use of fresh harvest surpasses the dried form due to its assumed greater efficacy, because of its intact and unchanged secondary metabolites [63]. Earlier, various researchers [5,56,64,65] published similar reports from other parts of Ethiopia.

Regarding to the preparation of remedies, the local ethnic people use different approaches depending on the type of diseases. The top popular approaches reported were pounding, crushing and boiling. They accounted for more than 70% of the reported preparation methods, whereas direct application, smoking, etc. accounted for 30% of the methods. Such reports have been given by other researchers including [5,52,64,65], suggesting the commonality of methods of remedy preparations by indigenous communities of different localities and ethnic groups in Ethiopia.

During field observations, we noticed that local people use two or more herbal combinations in the preparation of remedies to treat some illnesses. For example, combinations of bulbs of Allium cepa with rhizome of Zingiber officinale for impotence problem, seeds of Brassica nigra with Allium sativum bulbs for asthma, Carthamus tinctorius seeds with Allium sativum bulbs for cough, Rhamnus prinoides leaves with juice of Citrus lemon for tonsillitis and poly-herbal formulations (e.g. Leaves of Premna schimperi combined with leaves of Calpurnea aurea and Croton macrostachyus) for body swelling in livestock. Combined use of remedies has been previously reported [30,66] to cure some ailments, suggesting high synergistic effects.

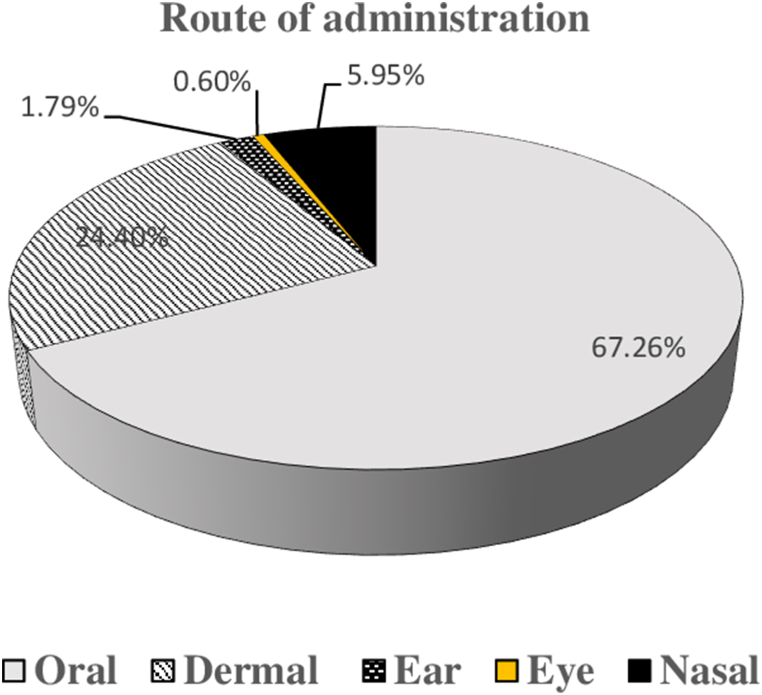

The indigenous people follow various routes of remedy administration or application, which of course is based on the type of ailment and the affected body part. Mostly remedies are taken orally, but dermal and nasal were also considerable routes recorded (Fig. 3). Different investigators [56,58,[67], [68], [69], [70]] who carried out similar research in various corners of the country have also reported the same.

Fig. 3.

Routes of administration of remedies.

3.4. Ethnobotanical indices

3.4.1. Informant consensus factor

The homogeneousness of traditional medical knowledge among the informants on utilization of medicinal plants for curing particular disease categories was tested using ICF index. The values of ICF vary from 0 to 1, whereby 1 depicts highest agreement and subsequent decrease in agreement level with values decreasing from 1 [71]. In the present study, the computed values of ICF for eight category of ailments ranged from 0.50 to 0.90 (Table 2). The finding showed that Swelling and hemorrhoid had the highest ICF value with a nearly complete agreement between respondents followed by gastrointestinal diseases and parasitic infections, Dermatology and Sensory organ diseases, febrile illness and related diseases. Earlier [72], reported highest ICF value (0.99) for hemorrhoid from another District in west Hararghe zone. This implies that hemorrhoid is the most common ailment that the local community shares information on the remedy of this ailment [73]. On the other hand, lower ICF value indicates rare occurrence of the ailment in the study area for which less information is exchanged among individuals to seek for its remedy [74].

3.4.2. Preference ranking

Ranking exercise performed by 10 key traditional healers on 6 plant species that were stated to cure cough revealed that Guizotia abyssinica was the favorite medicinal plant to cure cough (Table 3). This shows that the ethnic people of the study site prefer one plant over the other to treat a given ailment for which multiple remedies are suggested. This preference could be due to the perceived effectiveness of a medicinal plant for the reported ailment and further investigations on its chemical content and pharmacology are required.

Table 3.

Ranking of favorite medicinal plant to cure cough.

| No | Plant species | Respondents' (R1-R10) Scores |

Total | Rank | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | R9 | R10 | ||||

| 1 | Guizotia abyssinica | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 55 | 1st |

| 2 | Anthemis tigreenis | 5 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 52 | 2nd |

| 3 | Carthamus tinctorius | 5 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 48 | 3rd |

| 4 | Mentha aquatica | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 34 | 4th |

| 5 | Zingiber officinale | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 19 | 5th |

| 6 | Crinum abyssinicum | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 6th |

Note: Scores given by the informants (R1-R10) are based on the efficacy of the medicinal plant species to treat cough; where ‘6’ suggests the highest curative potential and ‘1’ suggests lowest potential to cure cough.

3.4.3. Fidelity level, RFC and CI

Ethnobotanical quantitative indices (e.g. FL, RFC and CI) were computed to determine popularity and cultural importance of medicinal plants used by the local people of the study area. Fidelity level (FL) helps to identify the most important plant used to cure a given disease. It suggests the medicinal plant that is specifically used to cure a given ailment. FL of a plant reported by many respondents for the same purpose will have the highest value, whereas plant reported for several purposes will have lowest FL [75]. In the current study, FL for all 104 plants was computed by considering the most frequently reported ailment to be treated by each medicinal plant. Results showed that the values ranged from 35.2 to 100% (Table 1). Majority (66%) of the medicinal plants had FL value of 100% (e.g., Croton macrostachyus, Hagenia abyssinica, Rydingia integrifolia, Salvia nilotica, Thymus schimperi, etc.). Cucurbita pepo had FL value of 94% followed by Mentha aquatic (84.9%), whereas the rest had below 80%. The high FL value shows that these plants were mentioned individually by several informants for the treatment of certain specific ailments. This could be a signal of their therapeutic efficiency for the reported ailments. In Ethiopia, there have been wide reports on the role of C. macrostachyus for treating ringworm [5,9,11,[76], [77], [78]]. Traditional use of H. abyssinica for the treatment of intestinal parasites (especially worms) has also been well vindicated [10,[79], [80], [81]]. Hence, the plant species with highest FL value deserve further investigations on their pharmacology and phytochemistry. The least FL index rank was reported for Dodonaea viscosa subsp. angustifolia for treating Eczema (Table 1). Although some plant species have been found with low FL index, they should not be ignored from conservation plan and pharmacological investigations for sustainable use in the future [82].

The RFC demonstrates the significance of the medicinal plants in relation to the respondents who mentioned them [83]. In our investigation, five plants having top FC values were Salvia nilotica (n = 70) followed by Lepidium sativum (n = 65), Rydingia integrifolia (n = 64), Nigella sativa (n = 62), Asplenium monanthes (n = 61) and Euphorbia abyssinica (n = 58). The RFC results of the entire medicinal plants ranged from 0.03 to 0.18 for their curative properties (Table 1). The highest RFC (0.18) was recorded for Salvia nilotica followed by Lepidium sativum, Rydingia integrifolia and Nigella sativa each 0.16; Euphorbia abyssinica and Asplenium monanthes each 0.15. Overall, 37% of the recorded plants had RFC values above 0.1 (Table 1). The high RFC values of these species depict that these plants are familiar and widely used by the locals for their medicinal property. Thus, plants with high RFC are recommended for further phytochemical and bioactivity studies. On the contrary, the lowest RFC (0.03) was recorded for Olea europaea, suggesting that this species is less known for its medicinal value. Of course, the relative frequency of citations differs from region to region and they depend on traditional medicinal knowledge of the local people [84].

The cultural importance index (CI) is used to determine the value of a particular plant that is used by the locals [84]. On analyzing the species ranking based on the CI index, Brassica nigra and Aloe trichosantha were amongst the most culturally important species with a CI index of 0.013 each followed by Aloe trichosantha, Nigella sativa and Ocimum lamiifolium with a CI index of 0.010 each (Table 1). Several plant species were found to have CI index of 0.003. The extent of information possessed by the locals, their background on local culture and the predominant situations of a given place influence CI values [84].

3.5. Socio-demographic features and knowledge on traditional medicine

A participant's level of traditional knowledge has always been associated with certain socio-demographic status including gender, age, educational level and occupation [85,86]. Thus, the above stated socio-demographic features were examined to unveil their role related to traditional medicinal knowledge based on the amount of cited medicinal plants by respondents. Results showed that male respondents cited significantly higher (t67.174 = 2.484, P = 0.015) amount of medicinal plants when compared to female counterparts (Table 4). In Ethiopia, the traditional medical knowledge is transferred from one generation to the other through verbal communication to family members, particularly to sons [30]. The higher medicinal knowledge of males than females could therefore be attributed to the gender biased knowledge transfer. The same result was reported by various researchers who conducted ethnobotanical investigations in different regions of Ethiopia [45,82,[87], [88], [89]]. Our statistical analysis showed that age categories varied significantly (P < 0.01, df = 4, F = 26.8) in the amount of reported medicinal plants. Overall, respondents of age ≥51 years cited large amount of medicinal plants when compared to individuals of age <51 (Table 4). This suggests that the older people possess accumulated knowledge due to their long years of interaction with their environment [90,91]. Some earlier studies conducted by Refs. [45,82,89,90,92] vindicate our results. The lower medicinal knowledge possessed by younger individuals implies the probable decline in knowledge transfer between generations, which in turn can be considered as one of the factors jeopardizing indigenous knowledge. Therefore, the elderly people should be encouraged to exchange their rich expertise on traditional medicine to the young ones before they die. Moreover, analysis of multiple linear regression showed that gender (β = 1.143, P = 0.05) and age (β = 1.925, P = 0.01) of the study population were found to be determinants of respondents' knowledge on traditional medicine, and our finding is in line with that of [5,59,93].

Table 4.

Demographic features of respondents.

| Demographic features | Categories | No. | No. of plants reported (mean ± SE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 305 | 5.87 ± 0.41 | 0.015 |

| Female | 91 | 4.34 ± 0.41 | ||

| Education | Illiterate | 151 | 7.10 ± 0.53 | <0.001 |

| Elementary level (1–8 grade) | 150 | 4.69 ± 0.28 | ||

| Secondary level (9–12 grade) | 75 | 2.70 ± 0.41 | ||

| >12 grade | 8 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | ||

| Religious study | 12 | 8.00 ± 2.30 | ||

| Age | 20–30 | 32 | 1.5 ± 0.19 | <0.001 |

| 31–40 | 48 | 2.38 ± 0.18 | ||

| 41–50 | 102 | 12.0 ± 0.42 | ||

| 51–60 | 103 | 10 ± 0.28 | ||

| >60 | 111 | 18.0 ± 0.65 | ||

| Occupation | Peasant | 258 | 5.60 ± 0.38 | <0.001 |

| Teacher | 68 | 3.33 ± 1.33 | ||

| Housewives | 37 | 5.72 ± 0.61 | ||

| Pensioners | 8 | 11.50 ± 1.50 | ||

| Merchants | 25 | 2.73 ± 0.45 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 380 | 5.73 ± 0.33 | <0.001 |

| Single | 16 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | ||

| Religion | Islam | 281 | 5.59 ± 0.40 | 0.802 |

| Christian | 115 | 5.41 ± 0.58 |

Respondents’ knowledge on traditional medicines of plant origin was also significantly affected by the level of their education (P < 0.01, df = 4, F = 10.5), occupation (P < 0.01, df = 4, F = 7.89) and marital status (t95.00 = 14.289, P < 0.001). Previous reports by Refs. [45,55,81,89,92] show that the number of reported medicinal plants, which suggests the extent of traditional knowledge, decreases with increasing level of education.

3.6. Threats to ethnomedicinal plants and conservation efforts

Respondents reported five anthropogenic factors that they consider as the key threatening factors to the availability of medicinal plants of their surroundings and ranked them according to their level of importance (Table 5). Expansion of agriculture through which natural ecosystems are exploited for farming was ranked first as the major cause of deterioration of medicinal plant resources followed by use of plant for fire wood, charcoal production, overgrazing by animals and use of plant materials for construction purposes. The livelihood of most Ethiopian population is based on agriculture, especially crop production. With increasing human population, agricultural lands are encroaching to the wilderness consistently, making agriculture as the dominant factor to convert the natural ecosystem to manmade ecosystem. Results of some previous studies also support our finding [16,52,73,93].

Table 5.

Anthropogenic factors for loss of medicinal plant species in the study site.

| No. | Threatening factors | Respondents' (R1-R10) Scores |

Total | Rank | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | R9 | R10 | ||||

| 1 | Agricultural expansion | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 57 | 1st |

| 2 | Fire wood collection | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 53 | 2nd |

| 3 | Charcoal | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 50 | 3rd |

| 4 | Overgrazing by animals | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 28 | 4th |

| 5 | House construction | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 5th |

Note: Scores given by the informants (R1-R10) are based the perceived threatening levels of the factors on the medicinal plants. Score 6 stands for highest threatening factor, whereas 1 is the least and others ordered according to their relative importance.

In spite of being threatened by anthropogenic factors, from our observation in the field, we have also noticed some conservation efforts being made for some medicinal plants by growing them around home. For example, Thymus schimperi, Coriandrum sativum, Ocimum lamiifolium, Ruta graveolens, Moringa oleifera, Rhamnus prinoides, Foeniculum vulgare and Punica granatum were found to be grown in home gardens by some people. These plants are being managed by humans most probably because of their use as food and spice in addition to their medicinal value. However, most of the reported medicinal plants are from wild and were given no conservation attention. Thus, they need due attention for conservation.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, report of high number of medicinal plants shows the occurrence of enormous knowledge on traditional medicine and reliance of the people on traditional medicine due to limited access to modern medication and for cultural reasons. Age and gender were predictors of knowledge on traditional medicine. Of all human activities, conversion of natural habitats for agricultural purposes was the major treat to medicinal plants. Therefore, appropriate conservation methods including growing of medicinal plants in home garden are recommended to preserve plants and associated indigenous knowledge. The medicinal plants, especially those with high preference ranking, ICF and FL should be screened pharmacologically for their efficacy and safety for wider usage.

Author contribution statement

Meskerem Bogale, J. M. Sasikumar, Meseret C. Egigu: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Ministry of Education, Ethiopia.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tulo District Administrative Office and the respondents for their cooperation.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15361.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Cotton C.M. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1996. Ethnobotany: Principles and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samar R., Shrivastava P.N., Jain M. Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants used by tribe of Guna District, Madhya Pradesh, India. Int. J. Cur. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2015;4(7):466–471. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaman W., Ahmad M., Zafar M., Amina H., Lubna, Saqib S., Ullah F., Ayaz A., Bahadur S., Park S. Diversity of medicinal plants used as male contraceptives: an initiative towards herbal contraceptives. Ind. J. Tradi. Know. 2022;21(3):616–624. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO (World Health Organization) 2000. Development of National Policy on Traditional Medicinal Report of the Workshop on Development of National Policy on Traditional Medicine. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yineger H., Yewhalaw D., Teketay D. Ethnomedicinal plant knowledge and practice of the Oromo ethnic group in southwestern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008;4 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-11. Article ID 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feyisa D. The origin of the Oromo: reconsideration of the theory of the cushitic roots. J. Oromo Stud. 1998;5 Article ID 155. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Getahun M. Oromo indigenous knowledge and practices in natural resources management: land, forest, and water in focus. J. Ecosyst. Ecography. 2016;6 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bekele E. 2007. Study on Actual Situation of Medicinal Plants in Ethiopia.http://www.endashaw.com [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mesfin F., Demissew S., Teklehaymanot T. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Wonago Woreda, SNNPR, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009;5:28. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Assefa B., Glatzel G., Buchmann C. C. Ethnomedicinal uses of Hagenia abyssinica (Bruce) J.F. Gmel. among rural communities of Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010;6:20. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Megersa M., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E., Beyene A., Woldeab B. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in yayu tuka district, east welega zone of Oromia regional state, west Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9(68):51–64. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avigdor E., Wohlmuth V., Asfaw Z., Awas H. The current status of knowledge of herbal medicine and medicinal plants in Fiche, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014;10 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-38. Article ID 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andarge E., Shonga A., Agize M., Tora A. Utilization and conservation of medicinal plants and their associated Indigenous Knowledge (Ik) in Dawuro Zone: an ethnobotanical approach. Int. J. Med. Plant Res. 2015;4(3):330–337. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kefalew A., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E E. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in Ada'a district, east Shewa zone of Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015;11 doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0014-6. Article ID 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jima T.T., Megersa M. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases in Berbere district, Bale zone of Oromia regional state, south east Ethiopia. Evid. Based Compl. Alternat. Med. 2018;17 doi: 10.1155/2018/8602945. Article ID 8602945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonfa N., Tulu D., Hundera K., Raga D. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants, its utilization, and conservation by indigenous people of Gera district, Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2020;6 Article ID 1852716. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feyisa M., Kassahun A., Giday M. Medicinal plants used in ethnoveterinary practices in Adea Berga District, Oromia region of Ethiopia. Evid. Based Compl. Alternat. Med. 2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/5641479. Article ID 5641479, 1-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belayneh A., Asfaw Z., Demissew S., Bussa N.F. Medicinal plants potential and use by pastoral and agro-pastoral communities in Erer Valley of Babile Wereda, Eastern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012;8:42. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belayneh A., Bussa N.F. Ethnomedicinal plants used to treat human ailments in the prehistoric place of Harla and Dengego valleys, eastern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CSA (Central Statistical Agency) Addis Ababa; Ethiopia: 2007. The 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Statistical Report for Oromia Region. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yemane T. second ed. Harper and Row; New York: 1967. Statistics, an Introductory Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tongco D.C. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007;5:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin G. Chapman and Hall; London, U.K: 1995. Ethnobotany: A Method Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexiades M. Selected Guidelines for Ethnobotanical Research: A Field Manual. The New York Botanical Garden Press; 1996. Collecting ethnobotanical data. An introduction to basic concepts and techniques; pp. 58–94. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weckerle C.S., de Boer, Puri H.J., et al. Recommended standards for conducting and reporting ethnopharmacological field studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;220:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friis I., White F. Addis Ababa University; 2003. Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea: Apiaceae to Dipsacaceae, red./Inga Hedberg; Sue Edwards; Sileshi Nemomissa. Bind 4, 1 Addis Ababa & Uppsala; pp. 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friis I. In: Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea Vol. 8. General Part and Index to Volumes 1-7 (Addis Ababa and Uppsala: the National Herbarium. Hedberg I., Friis I., Persson E., editors. 2009. Floristic richness and endemism in the flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea; pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bekele A.T., Birnie A., Tengbnaa B. Swedish International Development Authority; Nairobi, Kenya: 1993. Useful Trees and Shrubs for Ethiopia. Identification, Propagation and Management for Agricultural and Pastoral Communities, Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodrigo R.F., Saldanh U.P. Knowledge and use of medicinal plants by local specialists' in a region of Atlanta Forest in state of Pernambuco (Northern eastern Brazil) J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2005;1(9) doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teklehaymanot T., Gidey M. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by people in Zegie Peninsula, Northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007;3(3):12. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tardio J., Pardo-de-Santayana M. Cultural Importance Indices: a Comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of southern Cantabria (Northern Spain) Econ. Bot. 2008;62(1):24–39. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Napagoda M.T., Sundarapperuma T., Fonseka D., Amarasiri S., Gunaratna P. Scientifica; 2018. An Ethnobotanical Study of the Medicinal Plants Used as Anti-inflammatory Remedies in Gampaha District, Western Province, Sri Lanka. Article ID 9395052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siddique Z., Shad N., Shah G.M., Naeem A., Yali L., Hasnain M., Mahmood A., Sajid M., Idrees M., Khan I. Exploration of ethnomedicinal plants and their practices in human and livestock healthcare in Haripur District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021;17:55. doi: 10.1186/s13002-021-00480-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boakye M.K., Agyemang A.O., Turkson B.K., Wiafe E.D., Baidoo M.F., Bayor M.T. Ethnobotanical inventory and therapeutic applications of plants traded in the Ho Central Market, Ghana. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2022;23:8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderberg A., Baldwin B.G., Bayer R.G., et al., editors. vol. 8. Springer; 2007. pp. 61–588. (The Families and Genera of Flowering Plants). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soković M., Skaltsa H., Ferreira I.C.F.R. Editorial: bioactive phytochemicals in Asteraceae: structure, function, and biological activity. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01464. Article ID 1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marchioni I., Najar B., Ruffoni B., Copetta A., Pistell L. Bioactive compounds and aroma profile of some Lamiaceae edible flowers. Plants. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/plants9060691. Article ID 691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poonkodi K. Chemical composition of essential oil of Ocimum basilicum. (Basil) and its biological activities–an overview. J. Cri. Rev. 2016;3(3):56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wojdylo A., Oszmianski J., Czemerys R. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 32 selected herbs. Food Chem. 2007;105:940–949. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonesi M., Loizzo M.R., Leporini M., Tenuta M.C., Passalacqua N.G., Tundi R. Comparative evaluation of petit grain oils from six Citrus species alone and in combination as potential functional antiradicals and antioxidant agents. Plant Biosyst. 2017;152:986–993. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elansary H.O., El-Ansary D.O., Al-Mana F.A. 5-aminolevulinic acid and soil fertility enhance the resistance of Rosemary to Alternaria dauci and Rhizoctonia solani and modulate plant biochemistry. Plants. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/plants8120585. Article ID 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sasikumar J.M., Doss P.A., Doss A. Antibacterial activity of Eupatorium glandulosum leaves. Fitoterapia. 2005;76:240–243. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaiswal R., Kiprotich J., Kuhnert N. Determination of the hydroxycinnamate profile of 12 members of the Asteraceae family. Phytochemistry (Elsevier) 2011;72:781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petropoulos S.A., Fernandes A., Tzortzakis N., et al. Bioactive compounds content and antimicrobial activities of wild edible Asteraceae species of the Mediterranean flora under commercial cultivation conditions. Food Res. Int. 2019;119:859–868. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giday M., Asfaw Z., Woldub Z. Medicinal plants of the Meinit ethnic group of Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124(3):513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Birhanu T., Abera D., Ejeta E. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plant in selected Horro Gudurru district, Western Ethiopia. J. Biol. Agric. Healthcare. 2015;5(1):83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mogosse S. MSc Thesis. Haramaya University; Ethiopia: 2016. Assessment of Ethnomedicinal Plants and Associated Indigenous Knowledge in Oda-Bultum District, West Hararghe Zone of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jafarirad S., Rasoulpour I. Pharmaceutical ethnobotany in the Mahabad (West Azerbaijan) biosphere reserve: ethno-pharmaceutical formulations, nutraceutical uses and quantitative aspects. Brazilian J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2019;55 Article ID e18133. [Google Scholar]

- 49.da Costa F.V., Guimarae M.F.M., Messias M.C.T.B. Gender differences in traditional knowledge of useful plants in a Brazilian community. PLoS One. 2021;16(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253820. Article No e0253820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farooq A., Amjad M.S., Ahmad K., Altaf M., Umair M., Abbasi A.M. Ethnomedicinal knowledge of the rural communities of Dhirkot, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019;15(1):1–30. doi: 10.1186/s13002-019-0323-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meragiaw M., Asfaw Z., Argaw M. The status of ethnobotanical knowledge of medicinal plants and the impacts of resettlement in Delanta, north western Wello, northern Ethiopia. Evid. Based Compl. Alt. Med. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/5060247. Article No. 5060247, 1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahmed A.J. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by people of Gumer Woreda, Gurage Zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia. Acad. J. Biotechnol. 2021;9(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mukaila Y.A., Oladipo O.T., Ogunlowo I., Ajao A.A., Sabiu S. 2021. Which Plants for what Ailments: A Quantitative Analysis of Medicinal Ethnobotany of Ile-Ife, Osun State, Southwestern Nigeria. Article ID 5711547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 54.Constant N.L., Tshisikhawe M.P. Hierarchies of knowledge: ethnobotanical knowledge, practices and beliefs of the Vhavenda in South Africa for biodiversity conservation. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14 doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0255-2. Article No. 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tadesse A., Kagnew B., Kebede F., Kebede M. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human ailment in Guduru District of Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. J. Pharmacogn. Phytotherapy. 2018;10(3):64–75. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gebre T., Chinthapalli B. Ethnobotanical study of the traditional use and maintenance of medicinal plants by the people of Aleta-Chuko woreda, south Ethiopia. Phcog. J. 2021;13(5):1097–1108. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muluye A.B., Ayicheh W. Medicinal plants utilized for hepatic disorders in Ethiopian traditional medical practices: a review. Clin. Phytosci. 2020;6 Article No. 52. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ketema M. MSc Thesis, Haramaya University; Haramaya, Ethiopia: 2015. Assessment of Indigenous Knowledge on Medicinal Plants of Deder Woreda, East Hararghe Zone of Oromia, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weldearegay E.M., Awas T. Ethnobotanical study in and around Sirso natural forest of Melokoza district, Gamo Goffa zone, southern Ethiopia. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2021;22 Article No. 272021. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giday M., Asfaw Z., Elmqvist T., Woldu Z. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the Zay people in Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003;85(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00359-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bekalo T.H., Woodmatas S.D., Woldemariam Z.A. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by local people in the lowlands of Konta Special Woreda, southern nations, nationalities and peoples regional state. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009;5 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-26. Article No. 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng X., Xing F. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants around Mt. Yinggeling, Hainan Island, China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124(2):197–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiong Y., Sui X., Ahmed S., Wang Z., Long C. Ethnobotany and diversity of medicinal plants used by the Buyi in eastern Yunnan, China. Plant Divers. 2020;42(6):401–414. doi: 10.1016/j.pld.2020.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Birhanu A., Ayalew S. Indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants used in and around robe town, bale zone, Oromia region, southeast Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Res. 2018;12(16):194–202. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alemneh D. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used for the treatment of domestic animal diseases in yilmana densa and quarit districts, west gojjam zone, amhara region, Ethiopia. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2021;2 doi: 10.1155/2021/6615666. Article No. 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ayyanar M., Ignacimuthu S. Traditional knowledge of kani tribals in kouthalai of tirunelveli hills, Tamil nadu, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102(2):246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Agisho H., Osie M., Lambore T. Traditional medicinal plant utilization, management and threat in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2014;2(2):94–108. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Assegid A., Tesfaye A. Ethnobotanical study of wild medicinal trees and shrubs in Benna Tsemay District, Southern Ethiopia. J. Sci. Develop. 2014;2(1):17–33. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alemayehu G., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by local communities of Minjar-shenkor District, North Shewa zone of Amhara region, Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2015;3(6):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kewessa G., Abebe T., Demessie A. Indigenous knowledge on the use and management of medicinal trees and shrubs in Dale district, Sidama zone, southern Ethiopia. J. Plants People Appl. Res. 2015:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gazzaneo L.R.S., de Lucena R.F.P., de Albuquerquev U.P. Knowledge and use of medicinal plants by local specialists in a region of Atlantic Forest in the state of Pernambuco (Northeastern Brazil) J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2005;1 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-9. Article No. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fassil A., Gashaw G. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in chiro district, West Hararghe, Ethiopia. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2019;13(11):309–323. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heinrich M., Ankli A., Frei B., Weimann C., Sticher O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: healers' consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998;47:1863–1875. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heinrich M. Ethnobotany and its role in drug development. Phytother Res. 2000;14:479–488. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200011)14:7<479::aid-ptr958>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Friedman J., Yaniv Z., Dani A., Palewitch D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on the rationale analysis of an ethnopharmacological survey among bedouins in the Negev desert. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986;16:275–287. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Njoroge G.N., Bussmann R.W. Ethnotherapeautic management of skin diseases among the Kikuyus of Central Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;111(2):303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bekele G., Reddy P.R. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human ailments by Guji Oromo tribes in Abaya district, Borana, Oromia, Ethiopia. Univ. J. Plant Sci. 2015;3(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mbunde M.V.N., Innocent E., Mabiki F., Andersson P.G. Ethnobotanical survey and toxicity evaluation of medicinal plants used for fungal remedy in the southern highlands of Tanzania. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2017;6(1):84–96. doi: 10.5455/jice.20161222103956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Giday M., Teklehaymanot T., Animut A., Mekonen Y. Medicinal plants of the shinasha, agew-awi and amhara peoples in northwest Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110(3):516–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lulekal E., Kelbessa E., Bekele T., Yineger H. An Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Mana Angetu Wereda, south eastern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008;4(10):25–31. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kassa Z., Asfaw Z., Demissew S. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in sheka zone of southern nations nationalities and peoples regional state, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020;16 doi: 10.1186/s13002-020-0358-4. Article No. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chaachouay N., Benkhnigue O., Fadli M., et al. Heliyon; 2019. Ethnobotanical and Ethnopharmacological Studies of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Used in the Treatment of Metabolic Diseases in the Moroccan Rif. Article No. e02191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shaheen H., Qaseem M.F., Amjad M.S., Bruschi P P. Exploration of ethno-medicinal knowledge among rural communities of pearl valley, rawalakot, district poonch azad Jammu and Kashmir. PLoS One. 2017;12(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Iqbal M.S., Ahmad K.S., Ali M.A., Akbar M., Mehmood A., Nawaz F. An ethnobotanical study of wetland flora of Head Maralla Punjab Pakistan. PLoS One. 2021;16(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 85.Hanazaki N., Herbst D.F., Marques M.S., Vandebroek I. Evidence of the shifting baseline syndrome in ethnobotanical research. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-75. Article No. 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McCarter J., Gavin M.C. Assessing variation and diversity of ethnomedical knowledge: a case study from Malekula Island. Vanuatu, Econ. Bot. 2015:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chekole G. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used against human ailments in Gubalaf to District, Northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017;3 doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0182-7. Article No. 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tefera B.N., Kim Y.D. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019;5(1):1–21. doi: 10.1186/s13002-019-0302-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Girmay M., Lulekal E., Bekele T., Demissew S. S. Use and management practices of medicinal plants in and around mixed woodland vegetation, Tigray regional state, Northern Ethiopia. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2021;21 Article No. 43. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Giday M. An Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the Zay people in Ethiopia. Centrum för Biologisk Mångfald (CBM):s Skriftserie. 2001;3:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brandt R., Mathez-Stiefel S.-L., Lachmuth S., Hensen I., Rist S. Knowledge and valuation of Andean agroforestry species: the role of sex, age, and migration among members of a rural community in Bolivia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-83. Article No. 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Abebe B.A., Teferi S.C. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human and livestock ailments in hulet eju enese woreda, east gojjam zone of amhara region, Ethiopia. Evid. Based Compl. Alt. Med. 2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/6668541. Article No. 6668541, 1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kidane L., Gebremedhin G., Beyene T. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Ganta Afeshum district, eastern zone of Tigray, northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14 doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0266-z. Article No. 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.