Highlights

-

•

Heteropolysaccharides are more suitable for addition to emulsions than other sugars.

-

•

The electrostatic repulsion hinders the stratification of the emulsion.

-

•

The protein membrane in the emulsion is affected by different sugar structures.

-

•

Heteropolysaccharides make emulsions more stable during long-term storage.

Keywords: Myofibrillar protein, Emulsion, Sugars structure, Polysaccharide, Physicochemical properties, Stability

Abstract

Different sugars (glucose, GL; fructose, FR; hyaluronic acid, HA; cellulose, CE) were added to a myofibrillar protein (MP) emulsion (MP: 1.2 w/v%, sugar: 0.1% w/v) to study the effect of sugar structure on the physicochemical properties and stability of the MP emulsions. The emulsifying properties of MP-HA were significantly (P < 0.05) higher than those of the other groups. The monosaccharide (GL/FR) exerted negligible effects on the emulsifying performance of the MP emulsions. The ζ-potential and particle size implied that HA introduced stronger negative charges, significantly reducing the final particle size (190–396 nm). Rheological examinations indicated that the introduction of polysaccharides considerably increased the viscosity and network entanglement; confocal laser scanning microscopy and creaming index revealed that MP-HA was stable during storage, whereas MP-GL/FR/CE exhibited severe delamination after long-term storage. HA, a heteropolysaccharide, is most suitable for improving MP emulsion quality.

Introduction

Myofibrillar protein (MP) is a primary component of animal proteins, accounting for approximately 50% of total protein content (Wang, Li, Sun, et al., 2022). Importantly, it determines the principal properties of bulk proteins, which are related to the final quality of protein products (Wang, Li, Sun, et al., 2022). For example, its gel and emulsifying properties determine the quality of protein gels and emulsion products (Li, Fu et al., 2020). In particular, emulsions are commonly used in foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, petrochemicals, agricultural products, and other fields (Castel, Rubiolo, & Carrara, 2017). Oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions are most commonly used to encapsulate chemically unstable hydrophobic active substances in the food industry (Lomova, Sukhorukov, & Antipina, 2010). These emulsions are composed of emulsified oil droplets dispersed in a continuous phase. Therefore, it is necessary to add stabilizers, including amphiphilic polymers and solid particles, to prevent phase separation between the oil and water (Wang et al., 2020). Emulsifiers can be adsorbed at the water–oil interface (Gao et al., 2022) and MP can prevent lipid droplet oxidation due to its ability to scavenge free radicals, chelate metal ions, and/or form steric hindrances. In addition, MP can be used as a carrier in emulsion systems for nutritional and bioactive components. The study of protein emulsion systems has practical significance, but owing to the poor functional properties of natural MPs, they are prone to aggregation and flocculation (Yu, Li, Sun, Yan, & Zou, 2022). The stability of emulsions prepared using MP emulsifier alone remains unsatisfactory, so researchers have attempted to improve MP emulsion quality (Guo, Zhang, Jamali, & Peng, 2021).

Considerably increasing the aqueous phase viscosity can hinder emulsion droplet movement and improve emulsion stability. Recently, researchers have enhanced the stability and oxidation resistance of emulsion products by applying high-intensity ultrasound, polyphenols, polysaccharides, and other factors (Gao et al., 2022, Li et al., 2020, Tian et al., 2021). However, the addition of sugars often results in superior cost performance and operability compared to these methods. Sugars can be divided into monosaccharides and polysaccharides, where monosaccharides cannot be hydrolyzed into smaller sugars, whereas polysaccharides are macromolecules formed by monosaccharide polymerization (Yang, Li, Li, Sun, & Guo, 2020). In order to highlight the structural differences of sugars and consider the practicability of raw materials, disaccharides and oligosaccharides are not included in the selection range. Addition of sugars can increase viscosity of the continuous phase or form weak gel networks in aqueous media, acting as effective emulsion stabilizers (Albano, Cavallieri, & Nicoletti, 2018). Liang et al. (2014) reported that monosaccharide addition increased the thermostability of the emulsion. Gao et al. (2022) revealed that polysaccharides prevent droplet and protein aggregation, delaying phase separation. When the classification is further refined, monosaccharides can be separated into aldoses and ketoses according to the carbonyl position. Glucose (GL) and fructose (FR) are representative of the aldose and ketose families, respectively, which are abundant in nature (Wang, Li, Zhang, et al. 2022). Polysaccharides can be divided into homopolysaccharides and heteropolysaccharides based on the monomer unit differences. The discrepancy between the two classes arises from the constituent units of the chain (Yang et al., 2020). Herein, cellulose (CE) and hyaluronic acid (HA) were selected as representative homopolysaccharides and heteropolysaccharides, respectively. CE is a widely used biopolymer because of its abundance, low cost, good biodegradability, and biocompatibility (Lu, Zhang, Li, & Huang, 2018). HA is a long-chain polysaccharide composed of N-acetylglucosamine and glucuronic acid that is a major component of connective and epithelial tissue (Aguilera-Garrido, del Castillo-Santaella, Galisteo-González, José Gálvez-Ruiz, & Maldonado-Valderrama, 2021). HA is a readily available raw material and multi-functional applications make it an excellent representative heteropolysaccharide. Different sugars may exert special effects on the stability and other properties of MP emulsions due to their intrinsic properties. However, few studies have compared monosaccharides with polysaccharides, and the underlying emulsion stabilization mechanisms remain unclear.

Thus, monosaccharides (GL and FR) and polysaccharides (HA and CE) were added to the MP emulsions to establish MP-sugar emulsion systems. This study was performed to (1) explore the effects of monosaccharides and polysaccharides on the physicochemical properties (emulsifying properties, particle size/potential, and rheological behaviors), microstructure, and stability of MP emulsions to select sugars that are most suitable for use in MP emulsions; and (2) to compare and elucidate the role of the structural composition of monosaccharides and polysaccharides in the emulsification system, thus clarifying a potential mechanism of sugar type and structure for stabilizing and improving the physicochemical properties of MP emulsions. The results summarized herein provide a theoretical basis for selecting appropriate sugars as additives to optimize the performance of MP emulsion products.

Material and methods

Materials

Chicken breasts were collected from Zhucheng Waimao Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China). Pure soybean oil was purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Glucose (GL), fructose (FR), hyaluronic acid (HA, ≥ 99%, Streptococcus equi, Mw: 600 kDa) and cellulose (CE, > 99.8%, Mw: 342.297 kDa) were purchased from Macklin Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals were of analytical reagent grade.

Extraction of MP

MP was extracted according to the method described by Wang, Li, Sun, et al. (2022). Fresh chicken breast meat was crushed using a meat grinder and the fascia and connective tissue were removed. The muscles were ground and homogenized at 10,000 g for 30 s in a four-buffer system (100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), and 10 mM K2HPO4; pH 7.0; chicken: buffer = 1:4 [w/v]). This procedure was repeated three times. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a standard to determine protein concentration according to the Biuret method. Fresh MP is stored in an environment of 0–4 °C for standby.

Preparation of MP emulsions combined with sugars

The method described by Gao et al. (2022) was used with minor modifications. MP was dispersed in phosphate buffer (0.6 M KCl, 0.01 M KH2PO4, pH 7.0) and stirred for hydration at 4 °C (1.2 w/v% MP). The MP solutions (180 mL each) and soybean oil (20 mL each) were added to a beaker. Then, 0.1 w/v% GL, FR, HA, and CE were added and the mixture was homogenized by an Ultra-Turrax T25 high-speed blender (IKA, Staufen, Germany) at 15,000 rpm for 40 s. After three homogenization cycles, a uniform emulsion was obtained. The pH of the emulsion was adjusted to 7.0, using 0.1 M HCl or NaOH. The final emulsion consisted of 1.2 w/v% MP, 10 v/v% soybean oil, and 0.1 w/v% of the specified sugar. An MP emulsion without sugars was used as a control. Finally, 0.04% sodium azide was added to the emulsion to inhibit microbial growth.

Emulsion activity and emulsion stability indices

The emulsion activity index (EAI) and emulsion stability index (ESI) were measured using a previously reported method (Li et al., 2020). EAI and ESI together represent the emulsifying properties of emulsions. EAI and ESI are important indicators of the physicochemical properties of emulsions, particularly for emulsified products containing proteins (Augusta Rolim Biasutti, Regina Vieira, Capobiango, Dias Medeiros Silva, & Pinto Coelho Silvestre, 2007). The emulsion (50 μL) was added to 5 mL of 1 g/L sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution. The absorbance at 500 nm was measured initially (A0) and 10 min (A10) after emulsion formation. The EAI and ESI values were calculated using Eqs. (1), (2), respectively:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where C is the sample concentration (mg/mL) before emulsification, ϕ is the oil volume fraction (v/v) of the emulsion (0.1), N is the dilution ratio (100), and d is the optical path length equal to 0.01 m.

ζ-potential measurement

The ζ-potential characterizes the droplet surface charges and reflects the repulsive force between droplets in the emulsion (Zhang, Yang, Hu, Liu, & Duan, 2019). The emulsion sample was diluted 100 times with deionized water and ζ-potential was measured using a Zetasizer Nano (ZEN 3690, Malvern Instruments Inc., Malvern, UK). The data were collected after 60 s of sample balance in a DTS-7010 capillary tube at 25 °C to ensure at least five sequential stable readings (Gao et al., 2022).

Particle size distribution

The emulsion sample was diluted 100 times with deionized water using the method described by Chen et al. (2016). The sample was transferred to a 1-cm path length quartz cuvette and subjected to dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a DLS instrument (ZEN 3690, Malvern Instruments Inc., Malvern, UK) with a detection angle of 90° at 25.0 ± 0.1 ℃. Based on the scattering intensity, the hydrodynamic diameters of the particles and particle size distributions were estimated and obtained.

Emulsion morphology

Optical microscopy

Fresh emulsion (1 mL) was diluted in 1 mL of phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 20 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 6.0). The emulsion microstructure was observed using an optical microscope (Carl Zeiss, scope A1, TengrantInc., Germany) with a 40× objective lens.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

A 40× objective lens confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM; Leica, TSC, Sp8X, Germany) was used to observe the sample microstructures in fluorescent mode. A certain amount of emulsion was diluted with two volumes of PBS buffer (CLSM operated, 20 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 6.0). The diluted samples were mixed with 40 μL of Nile Blue (0.01%, w/v) and Nile red (0.01%, w/v) solutions. After dyeing for 2 h, 80 μL of the stained sample was placed on a glass slide and covered with a glass slide, ensuring that no air gaps or bubbles formed between the mixture and the cover glass. After mixing evenly for 2 min, Nile blue and Nile red images were obtained at excitation wavelengths of 488 and 633 nm, respectively. Each sample was randomly captured five times at a resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels.

Rheological properties

A dynamic shear rheometer (MCR302, Anton Paar, Austria) equipped with a parallel plate (60 m diameter and 1 mm thickness) was connected to a cooling system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, New York, NY, USA). The sample flow behavior was determined using tests developed by Zhao et al. (2014). The apparent viscosity was determined in the shear rate range of 0.1–1000.0 s−1 at 25 °C with a gap width of 1000 μm. The 1–10 s−1 range was selected to ensure that any changes could be clearly observed. The storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) were determined as functions of the angular frequency (ω) at 0.1–100.0 rad/s. The range of 1–10 rad/s was selected to ensure that any changes could be observed clearly. The G′ profile of MP was measured while the temperature was increased from 20 to 80 °C at a heating rate of 1 °C/min (thermal gelation) while continuously recording G′ values.

Creaming index of the emulsions during cold storage

The emulsion creaming index (CI) was determined using the techniques described by Shi et al. (2021) with some modification. First, 20 mL of a newly formulated emulsion was transferred to a single glass bottle with a plastic cap and stored at 4 °C to measure the CI. The serum layer height (H1, cm) and total emulsion height (H0, cm) were recorded every 12 h from 0 h to 168 h after emulsion preparation and CI was calculated using Eq. (3):

| (3) |

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine statistical differences. Multiple comparisons were performed according to Duncan’s multiple range test using SPSS19.0 software. All values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, with a significant difference of P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Physicochemical properties of MP emulsions with different sugars

Emulsifying properties

MP emulsification indicated that it is a perfect emulsifier. During homogenization, these amphiphilic biopolymers gather at the oil–water interface to form an interface coating that prevents flocculation and/or coalescence through steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion (Setiowati, Wijaya, & Van der Meeren, 2020). EAI refers to the emulsifier adsorption capacity at the oil–water interface, whereas ESI refers to the ability of the protein to inhibit phase separation. Changes in the EAI and ESI of MP emulsions after the addition of different sugars are listed in Table 1. The emulsifying ability of MP was poor and the sugar addition considerably strengthened the EAI and ESI of the control. EAI of the MP emulsion was increased from 14.79 ± 1.39 m2/g (control) to 20.27 ± 2.55 m2/g (MP-CE), while ESI increased from 67.07 ± 2.69% (control) to 89.87 ± 2.14% (MP-HA). This indicates that sugar can be used as a stabilizer to promote the emulsifying ability of MP and improve the stability of related emulsion products. These results are in agreement with those reported by Gao et al. (2022). Their research found that different sugars can bring varying degrees of improvement in EAI and ESI of low-salt MP emulsions, especially when combined with HIU treatment, which amplifies this effect. More importantly, they found that polysaccharides can be used as stabilizers to improve the stability of low-salt MP emulsions. Interestingly, it was confirmed that distinct sugars exhibit obvious differences in terms of emulsifying ability when added to MP emulsions. First, the EAI of MP emulsions containing polysaccharides (MP-HA, MP-CE) were significantly (P < 0.05) higher than those of monosaccharide-containing emulsions (MP-GL, MP-FR). This may be because the polysaccharides have a larger molecular weight and exert more significant steric hindrance than monosaccharides. This resulted in stronger adsorption capacity, allowing the emulsifier to play a bridging role between oil and water (Ribeiro, Morell, Nicoletti, Quiles, & Hernando, 2021). In addition, the mutual aggregation of droplets was prevented, phase separation delayed, and stability of the emulsification improved (Albano et al., 2018). Even similar sugars exhibited different effects on the EAI and ESI of the corresponding MP emulsions, but this phenomenon was only observed for polysaccharides. For instance, the EAI of MP-HA (27.49 ± 2.14 m2/g) was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than that of MP-CE (20.27 ± 2.55 m2/g), while the difference between MP-GL and MP-FR was negligible (P > 0.05). This may have a significant correlation with the different polysaccharide structures, as most homopolysaccharides are hydrophilic polysaccharides, which exhibit weak emulsifying abilities (Ribeiro et al., 2021). In contrast, heteropolysaccharides form long-chain units that are commonly able to stabilize protein-oil–water systems by fixation. This system is more stable than monosaccharides composed of the same unit as found in the monomers of the polysaccharides (Lin et al., 2018).

Table 1.

Changes in the emulsifying ability index (EAI) and emulsifying stability index (ESI), ζ-potential and average droplet size (size distribution A/B) of MP emulsions containing various sugars.

| Group | EAI (m2/g) | ESI (%) | ζ-potential (mV) | Size distribution A (nm) |

Size at intermediate peak A (nm) |

Size distribution B (nm) |

Size at intermediate peak B (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 14.79 ± 1.39d | 67.07 ± 2.69d | −5.84 ± 0.78d | 531–955 | 712 ± 9.14a | ||

| MP-GL | 17.89 ± 0.98c | 72.19 ± 2.69b | −6.12 ± 0.11c | 78.80–190 | 122.00 ± 8.03a | 190–615 | 396 ± 13.11b |

| MP-FR | 17.80 ± 1.11c | 72.78 ± 3.47b | −5.33 ± 0.10d | 68.10–122 | 91.30 ± 4.63b | 220–531 | 369 ± 14.87bc |

| MP-HA | 27.49 ± 2.14a | 89.87 ± 2.14a | −10.57 ± 0.25a | 190–396 | 255 ± 12.36d | ||

| MP-CE | 20.27 ± 2.55b | 70.88 ± 4.12c | −8.27 ± 0.07b | 220–459 | 295 ± 11.58c |

Note: intermediate peak A (at approximately 100 nm), intermediate peak B (at approximately 500 nm). Different letters (a-d) in the superscript indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Different sugars (glucose, GL; fructose, FR; hyaluronic acid, HA; cellulose, CE). Control refers to the MP emulsion without sugars.

Protein adsorbed on the oil drop surface in the emulsion can retain an electric charge (Shanmugam & Ashokkumar, 2014). The MP emulsion ζ-potential increased the phase energy and provided a high energy barrier between the emulsion droplets, resulting in strong electrostatic repulsion (Li, Zhao et al., 2020). Generally, MP emulsions are negatively charged because of the inherent nature of MP, and the addition of sugar decreases the ζ-potential (Chivero, Gohtani, Yoshii, & Nakamura, 2015). Table 1 shows that the addition of monosaccharides did not affect the MP emulsion ζ-potential likely because the weakly charged monosaccharide could not alter the ζ-potential of the entire MP emulsion. The absolute ζ-potential value of MP-GL was moderately higher than that of MP-FR, likely due to the introduction of more negative charges by hydroxyl groups on GL (an aldose). This is quite different from ketose without an aldehyde group (Wang, Li, Zhang, et al. 2022). When polysaccharides were added, the ζ-potential of the control significantly (P < 0.05) increased from −5.84 ± 0.78 mV (control) to −10.57 ± 0.25 (MP-HA) and −8.27 ± 0.07 mV (MP-CE). HA contains a large number of strongly negative charges due to its carboxyl groups, so its addition dramatically increased ζ-potential (Kupper, Klosowska-Chomiczewska, & Szumala, 2017). Therefore, HA could combine with a large amount of water, imparting excellent emulsifying performance to the MP-HA emulsion. The ζ-potential of MP-CE increased in absolute value because of the secondary structural changes in MP caused by CE, which expanded the protein structure (Li, Zhao et al., 2020). These changes decrease the exposure of positively charged groups and increased the negative charge of the proteins. Nevertheless, the increase in absolute ζ-potential value from the control was markedly less than that of MP-HA.

Droplet size and optical microscopy

Table 1 shows consistent differences in particle size, particularly after polysaccharide addition, where sugar addition caused changes in the droplet size and distribution in the MP emulsions. The particle size distribution of the control was 531–955 nm with an average particle size of 712 ± 9.14 nm, significantly (P < 0.05) larger than those of the other groups. This indicated that sugar could disperse the droplets evenly and prevent protein and oil aggregation. Similar results were reported by Chivero et al. (2015). However, there was an intriguing and significant differences in the particle size distribution between the monosaccharide and polysaccharide emulsions. Monosaccharide addition created a double peak distribution, whereas polysaccharide addition maintained the single peak mode observed in the control group. This indicated that monosaccharides induced MP aggregation, and the soluble polymer generated the first small peak, which also increased the emulsion particle size. Therefore, the distribution of the second peak of MP-GL (396 ± 13.11 nm) and MP-FR (369 ± 14.87 nm) was significantly (P < 0.05) greater than that of MP-HA (255 ± 12.36 nm) and MP-CE (295 ± 11.58 nm). MP-HA with a smaller particle size expanded the specific surface area and total charge per unit droplet, resulting in stronger electrostatic interactions, creating a uniform, dense, and complex system (Zang, Wang, Yu, & Cheng, 2019). Furthermore, the higher density and ζ-potential values prevented emulsion separation and improved stability. As shown in Fig. 1, the particle size and distribution of the MP emulsion droplets were determined, distinctly identifying differences caused by addition of the various sugars which were also verified by microscopy. Compared to the control, GL, FR, HA, and CE significantly (P < 0.05) reduced the droplet size and agglomeration was significantly reduced. However, small droplet aggregation was still observed in MP-GL, MP-FR, and MP-CE, which was the main reason behind the increased average particle size. MP-HA exhibited a uniform distribution with a regular droplet size, indicating that HA could uniformly disperse the MP emulsion droplets in the oil–water system. This was conducive to MP emulsification and the formation of a thin protein film on the droplet surface. The protein film thickness in the other groups was significantly larger, which was not conducive to emulsion stability. The flocculation that occurs in an emulsion is called reverse aggregation and occurs when several droplets combine due to unbalanced attraction and repulsion effects (Reiffers-Magnani, Cuq, & Watzke, 2000). The flocculation of MP-GL, MP-FR, and MP-CE may be related to the charge properties of the respective emulsion systems. This highlights the utility of polysaccharides (in particular heteropolysaccharides) for enhancing MP emulsion stability. The strong negative charge of HA prevented flocculation of emulsion droplets, resulting in a uniform equilibrium state for the MP-HA emulsions (Chivero et al., 2015).

Fig. 1.

Changes in the droplet size distribution and optical micrographs of MP emulsions combined with various sugars. Control refers to the MP emulsion without sugars. The different sugars are: glucose, GL; fructose, FR; hyaluronic acid, HA; cellulose, CE.

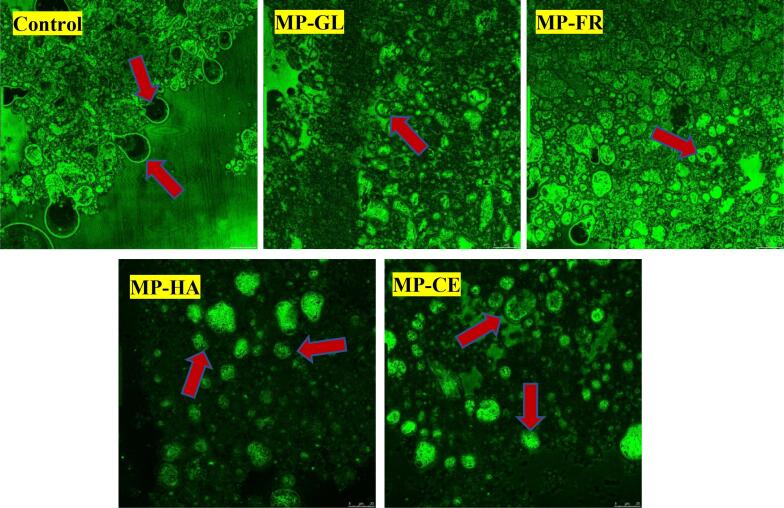

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

The oil was dyed green by Nile Red and the protein was dyed red by Nile blue (Fig. 2). From the images of each group, a layer of protein film was wrapped around the droplets, which is a key factor in MP emulsion formation. MP exhibits hydrophilic and lipophilic amphiphilic properties (Li et al., 2021), but MP alone is prone to agglomeration, which considerably reduces the quality and stability of the emulsion. In the control, the droplets were encapsulated by an incomplete protein membrane and some free protein aggregates were observed. When sugar was added, this agglomeration was eliminated and granular proteins were adsorbed on the water–oil interface to strengthen the membrane. The addition of GL and FR caused the droplets to disperse, decreasing the particle size. However, adhesion was still observed, which resulted in visible stratification of the MP emulsion. When the polysaccharide was added, MP emulsion aggregation inhibition was significantly strengthened, further reducing the droplet size. However, droplet aggregation in MP-HA was lower than that in MP-CE and the oil droplets of MP-HA became small and uniformly wrapped by protein. Electrostatic interactions and steric hindrance caused by the interfacial proteins prevented droplet aggregation, delayed phase separation, and greatly enhanced the emulsion stability (Albano et al., 2018). Furthermore, Wang, Tian, and Xiang (2020) demonstrated that low viscosity emulsions exhibit more significant agglomeration, consistent with the results presented herein. The microscopic images were consistent with previous characterizations of physicochemical indicators, indicating that polysaccharides can improve MP emulsion quality to a greater extent than monosaccharides, with heteropolysaccharides showing the greatest effects. The steric hindrance and branched chain viscosity of polysaccharides significantly enhance the emulsion dispersion and introduction of strong negative charges promotes the interaction between oil and water.

Fig. 2.

Changes in the confocal laser scanning micrographs and images after MP emulsion stabilization with sugars.

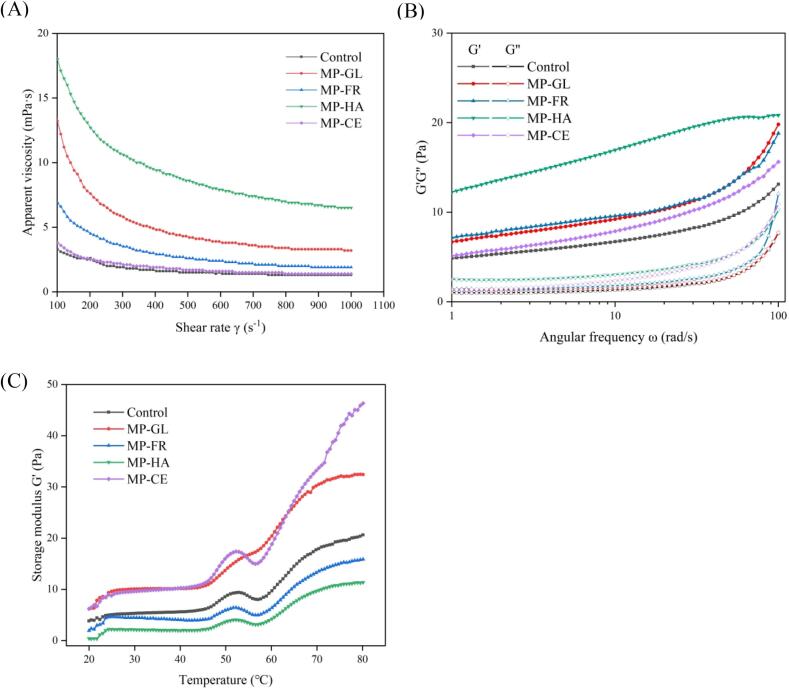

Rheological properties

Emulsion viscosity is considerably affected by the particle size, conformation, and interaction of constituent macromolecules (Gao et al., 2022). Fig. 3A shows the changes in apparent viscosity of the MP emulsions after the addition of different sugars. The addition of sugars other than CE significantly increased the MP emulsion viscosity, particularly for MP-HA which was significantly higher than those of the other groups. As an aldose, GL provides more hydroxyl groups to act on myosin rods than FR (a representative ketose), which inhibits their interaction with other myosin rods. The negative charge also increased the MP emulsion viscosity (Wang, Li, Zhang, et al. 2022). The improvement effect on MP emulsion stability can be ordered: heteropolysaccharides (HA) > monosaccharides (GL, FR) > homopolysaccharides (CE). It is likely that the powerful negative charge introduced by HA increased the electrostatic forces in the system, improving the protein adsorption capacity on the oil droplet surface (Qian & McClements, 2011). The negatively charged carboxyl group and the repulsion between hydrogen bonds in proteins generated the spherical MP-HA polymer in aqueous solution, occuping a large hydrodynamic volume (Sutariya & Salunke, 2022). CE was piled up from microfibrils, wherein highly ordered crystalline regions were interrupted by disordered regions (amorphous or comparatively disordered). Similar to CE, the same polysaccharides can easily polymerize and show negligible surface activity (Lu et al., 2018). Many CE molecules competitively replace MP adsorbed on the droplet surface, weakening the interaction between droplets and decreasing viscosity (Nishinari et al., 2018). In addition, the entanglement between homopolysaccharide chains is more easily broken compared to heteropolysaccharides and the molecular chain orientation is more random. Finally, the interaction between adjacent chains was hindered, resulting in decreased MP-CE viscosity. Therefore, the apparent viscosity of MP-CE was not significantly different from that of the control.

Fig. 3.

Flow curves of viscosity as a function of shear rate (A), plots of G′ and G″ as a function of angular frequency ω (B), and changes in G′of MP emulsion heated from 20 to 80 °C (C) with different sugars.

The frequency scan test results could also be explained by changes in the type of sugar added. As shown in Fig. 3B, G′ and G” respectively represent the storage and loss moduli of the MP emulsion. Over the frequency range tested, G′ was much larger than G”, indicating that the emulsion was predominantly elastic. In addition, a weak three-dimensional gel network was detected in the emulsion (Lu et al., 2018). Compared to the control, the MP emulsion containing sugar exhibited stronger elasticity caused by the entanglement and bridging between droplets mediated by sugar particles (Kalashnikova, Bizot, Bertoncini, Cathala, & Capron, 2013). West and Rousseau (2019) also demonstrated that adding sugar significantly strengthened the G′ and hardness of the oil phase, thereby improving the emulsion rheological properties. The G′ of the polysaccharide MP emulsions were higher than those of the monosaccharides, likely due to their higher molecular weight, steric hindrance, and elasticity (Gao et al., 2022). The G′ value of MP-HA was larger, but its separation from G” was smaller, which confirmed that HA addition improved the stability and fluid properties of the MP emulsion. The natural negative charge generated by the carboxylic acid group enabled MP-HA to bind a large number of water molecules. This large water binding force allowed HA to form a highly viscous aqueous solution when mixed (Sutariya & Salunke, 2022). During the later stage of the test, the G′ and G” of MP-FR intersected because the higher shear rate promoted the conversion of ketose into a Newtonian fluid, which could form a dilute solution separate from the gel network (Methacanon, Krongsin, & Gamonpilas, 2014).

In the temperature test, G′ represents the MP emulsion thermostability. As shown in Fig. 3C, sugar addition altered the thermostability of the MP emulsion. The addition of HA and FR imparted heat and solidification resistance to the MP emulsion, resulting in a significantly lower G′ value compared to the control. This can be explained by the steric hindrance of the heteropolysaccharides directly affecting the thermostability of MP-HA, which considerably increases the droplet resistance to high-temperature heating. In contrast, FR reduced the thermal sensitivity of the emulsion owing to its resistance to MP/droplet interaction. The addition of GL and CE substantially enhanced the G′ value of the emulsion, specifically in MP-GL at 55–70 °C. This illustrates that the hydrophilicity of the heteropolysaccharide enhanced the emulsion thermal sensitivity and facilitated physical property modification. As an aldose, GL exerted more dramatic effects because the presence of a large number of hydroxyl groups improved the head–tail interaction of myosin. The GL hydroxyl group combines with protein residues, which stretches the protein and exposes more hydrophobic groups. A greater increase in surface hydrophobicity would result in weak protein stability. The weakening of the interaction between proteins and water results in hydrophobic aggregation and this denaturation weakens the heat resistance of the MP-GL emulsion (Li, Fu et al., 2020).

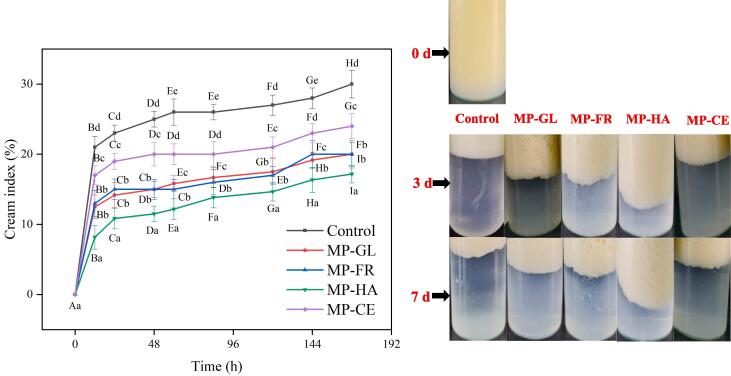

Creaming index

Emulsions are systems constructed by water and oil that contain an emulsifier and can be easily destroyed over time by precipitation, flocculation, aggregation, Ostwald maturation, and phase separation (Albano et al., 2018). CI is an important index for testing emulsion stability as it represents storability. The main factors influencing CI are changes in gravity and density (Ma et al., 2019). Fig. 4 shows the change in emulsions stored at 4 °C for 7 d (days). At day 0, each group displayed a trend of slowly continuing to the layer. The control without sugar showed significantly faster stratification, followed by MP-CE. The movement speed of MP-GL was similar to that of MP-FR, whereas the slowest stratification was observed for MP-HA. Emulsion stability significantly increased after sugar addition and the order of the effect was as follows: HA > GL = FR > CE. The high-viscosity continuous phase limited droplet aggregation and molecular motion through increased resistance that slowed molecules and the macroscopic upper interface (Wang et al., 2020). The weak emulsion gel network formed by sugar addition can fix the local structure, which considerably hinders droplet movement (Farshi et al., 2019). The high viscosity polysaccharides can decrease fluidity between droplets and prevent aggregation, enhancing the apparent viscosity and stability of the MP emulsion (Castel et al., 2017). The highest stability of MP-HA was likely caused by a combination of electrostatic repulsion, steric hindrance, and thickening effects (Zhang, Cai, Ding, & Wang, 2021). CE is a homopolysaccharide that exhibits strong hydrophilicity, leading to MP aggregation and significant stratification after long-term storage. Compared to the polysaccharides, monosaccharides exerted much less electrostatic and steric effects, resulting in less stable emulsions. Consequently, HA, as a heteropolysaccharide, is more suitable for enhancing the storage stability of MP emulsions. The improved emulsion stability can be attributed to particle aggregation at the O/W interface. The formation of the emulsion network in the continuous phase limited droplet interaction (Mwangi, Ho, Tey, & Chan, 2016). Therefore, it was confirmed that the network formed by polysaccharide particles inhibited interaction between droplets and the effect of heteropolysaccharides on droplet movement was stronger than that of homopolysaccharides.

Fig. 4.

Creaming index of MP emulsions with different sugars. Means with different letters (a–e, A–I) within the same parameter group differ significantly (P < 0.05). The attached images show the final stable MP emulsions of each group.

Mechanisms of sugars influence on the physicochemical properties and stability of MP emulsions

As shown in Fig. 5, the influence of the sugars on the MP emulsions varied. Although the final result was decreased droplet size and breaking aggregation, the droplets were more evenly and stably distributed throughout the system. From the droplet structure and physicochemical properties it could be inferred that the four sugars acted via different mechanisms. Aldose monosaccharides contain more hydroxyl groups, which promote the head tail binding of myosin and the emulsifying ability of MP (Wang, Li, Zhang, et al. 2022). The ketose monosaccharide contains no aldehyde group, so it only reduced the droplet size and promoted even distribution of the emsulsion. Ketone groups may reduce the droplet size by dividing larger droplets into smaller droplets. The introduction of large steric hindrance and strong negative charges of heteropolysaccharide stregnthens the interaction between MP and oil–water, while significantly decreasing particle size (Ribeiro et al., 2021). Furthermore, the steric hindrance and viscous properties of heteropolysaccharides hinder the movemet and phase separation of droplets, improving MP emulsion stability (Zhang & Li, 2022). Although the characteristics of polysaccharides can improve the physicochemical properties of MP emulsions, the hydrophilicity of polysaccharides greatly reduces their stability. The improvement effect on emulsion stability was reduced owing to the single hydrophilicity of the homopolysaccharides and significant aggregation and stratification were still observed due to phase separation. Finally, the property changes caused by the differences in sugar structure were fully reflected in the MP emulsion. An important discovery is that the addition of sugar mainly affects the properties of the protein film of the encapsulated droplets, and further changes the droplet state of the emulsion. The aldehyde and ketone groups in monosaccharides contribute differently to the protein film formation surrounding the oil droplets, which is closely related to the particle size and distribution of the final droplets. The simple constituent units in different polysaccharides reflect their respective abilities to promote repulsion between droplets, which is important for the uniformity and stability of the MP-HA and MP-CE droplets. In summary, the different sugar structures are the main reason for the different properties of the resulting sugar-MP emulsions.

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram of the interaction mechanism of sugar addition on the physicochemical properties and stability of the MP emulsion.

Conclusions

The physicochemical properties and stability improvement effects of different sugars in MP emulsions were investigated. It was confirmed that the addition of all types of sugars showed beneficial effects on the physicochemical properties and stability of MP emulsions, but the effect varied depending on the sugar. The common point is that the addition of sugar mainly changes the protein film that encapsulates the droplets, thus changing the droplet state of the MP emulsion. Compared with aldose, ketose in monosaccharides imparted enhanced stability and droplet distribution in the MP emulsion, but viscosity improvements were inadequate. Compared to the monosaccharides, the polysaccharides produced MP emulsions with smaller particle sizes, more uniform distributions, and better storage stability. In particular, heteropolysaccharides were markedly stronger than homopolysaccharides for reducing particle size and improving the viscosity and stability. In conclusion, polysaccharides are better than monosaccharides for improving the physicochemical properties and stability of MP emulsions. Heteropolysaccharides are more suitable than homopolysaccharides for improving MP emulsion quality. This study provides a theoretical basis for widening the application of sugars in MP oil-in-water emulsions and upgrading their product value.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ke Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Yan Li: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Jingxin Sun: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Yimin Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Shandong Modern Agricultural Technology and Industry System (SDAIT-11-11) and China Agricultural Research System (CARS-41-Z06), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2022MC087).

Contributor Information

Jingxin Sun, Email: jxsun20000@163.com.

Yimin Zhang, Email: ymzhang@sdau.edu.cn.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Aguilera-Garrido A., del Castillo-Santaella T., Galisteo-González F., José Gálvez-Ruiz M., Maldonado-Valderrama J. Investigating the role of hyaluronic acid in improving curcumin bioaccessibility from nanoemulsions. Food Chemistry. 2021;351 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albano K.M., Cavallieri N.L.F., Nicoletti V.R. Electrostatic interaction between proteins and polysaccharides: Physicochemical aspects and applications in emulsion stabilization. Food Reviews International. 2018:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Augusta Rolim Biasutti E., Regina Vieira C., Capobiango M., Dias Medeiros Silva V., Pinto Coelho Silvestre M. Study of some functional properties of casein: Effect of ph and tryptic hydrolysis. International Journal of Food Properties. 2007;10(1):173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Castel V., Rubiolo A.C., Carrara C.R. Droplet size distribution, rheological behavior and stability of corn oil emulsions stabilized by a novel hydrocolloid (Brea gum) compared with gum arabic. Food Hydrocolloids. 2017;63:170–177. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zou Y., Han M., Pan L., Xing T., Xu X., Zhou G. Solubilisation of myosin in a solution of low ionic strength l-histidine: Significance of the imidazole ring. Food Chemistry. 2016;196:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivero P., Gohtani S., Yoshii H., Nakamura A. Effect of xanthan and guar gums on the formation and stability of soy soluble polysaccharide oil-in-water emulsions. Food Research International. 2015;70:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Farshi P., Tabibiazar M., Ghorbani M., Mohammadifar M., Amirkhiz M.B., Hamishehkar H. Whey protein isolate-guar gum stabilized cumin seed oil nanoemulsion. Food Bioscience. 2019;28:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gao T., Zhao X., Li R., Bassey A., Bai Y., Ye K., Zhou G. Synergistic effects of polysaccharide addition-ultrasound treatment on the emulsified properties of low-salt myofibrillar protein. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;123 [Google Scholar]

- Guo X.Y., Zhang Y.W., Jamali M.A., Peng Z.Q. Manipulating interfacial behaviour and emulsifying properties of myofibrillar proteins by L-Arginine at low and high salt concentration. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2021;56(2):999–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Kalashnikova I., Bizot H., Bertoncini P., Cathala B., Capron I. Cellulosic nanorods of various aspect ratios for oil in water Pickering emulsions. Soft Matter. 2013;9(3):952–959. [Google Scholar]

- Kupper S., Klosowska-Chomiczewska I., Szumala P. Collagen and hyaluronic acid hydrogel in water-in-oil microemulsion delivery systems. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2017;175:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Zhao Y., Wang X., Tang H., Wu N., Wu F., Elfalleh W. Effects of (+)-catechin on a rice bran protein oil-in-water emulsion: Droplet size, zeta-potential, emulsifying properties, and rheological behavior. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;98 [Google Scholar]

- Li K., Fu L., Zhao Y.Y., Xue S.W., Wang P., Xu X.L., Bai Y.H. Use of high-intensity ultrasound to improve emulsifying properties of chicken myofibrillar protein and enhance the rheological properties and stability of the emulsion. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;98 [Google Scholar]

- Li M.H., Ritzoulis C., Du Q.W., Liu Y.F., Ding Y.T., Liu W.L., Liu J.H. Recent progress on protein-polyphenol complexes: Effect on stability and nutrients delivery of oil-in-water emulsion system. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.765589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Matia-Merino L., Patel H., Ye A., Gillies G., Golding M. Effect of sugar type and concentration on the heat coagulation of oil-in-water emulsions stabilized by milk-protein-concentrate. Food Hydrocolloids. 2014;41:332–342. [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.H., Shen M.Y., Liu S.C., Tang W., Wang Z.J., Xie M.Y., Xie J.H. An acidic heteropolysaccharide from Mesona chinensis: Rheological properties, gelling behavior and texture characteristics. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2018;107:1591–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomova M.V., Sukhorukov G.B., Antipina M.N. Antioxidant coating of micronsize droplets for prevention of lipid peroxidation in oil-in-water emulsion. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2010;2(12):3669. doi: 10.1021/am100818j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X.X., Zhang H.W., Li Y.Q., Huang Q.R. Fabrication of milled cellulose particles-stabilized Pickering emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2018;77:427–435. [Google Scholar]

- Ma W., Wang J., Xu X., Qin L., Wu C., Du M. Ultrasound treatment improved the physicochemical characteristics of cod protein and enhanced the stability of oil-in-water emulsion. Food Research International. 2019;121:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methacanon P., Krongsin J., Gamonpilas C. Pomelo (Citrus maxima) pectin: Effects of extraction parameters and its properties. Food Hydrocolloids. 2014;35:383–391. [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi W.W., Ho K.W., Tey B.T., Chan E.S. Effects of environmental factors on the physical stability of pickering-emulsions stabilized by chitosan particles. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;60:543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Nishinari K., Fang Y., Yang N., Yao X., Zhao M., Zhang K., Gao Z. Gels, emulsions and application of hydrocolloids at Phillips Hydrocolloids Research Centre. Food Hydrocolloids. 2018;78:36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Qian C., McClements D.J. Formation of nanoemulsions stabilized by model food-grade emulsifiers using high-pressure homogenization: Factors affecting particle size. Food Hydrocolloids. 2011;25(5):1000–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Reiffers-Magnani C.K., Cuq J.L., Watzke H.J. Depletion flocculation and thermodynamic incompatibility in whey protein stabilised O/W emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2000;14(6):521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro E.F., Morell P., Nicoletti V.R., Quiles A., Hernando I. Protein- and polysaccharide-based particles used for Pickering emulsion stabilisation. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;119(2) [Google Scholar]

- Setiowati A.D., Wijaya W., Van der Meeren P. Whey protein-polysaccharide conjugates obtained via dry heat treatment to improve the heat stability of whey protein stabilized emulsions. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2020;98:150–161. [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam A., Ashokkumar M. Ultrasonic preparation of stable flax seed oil emulsions in dairy systems – Physicochemical characterization. Food Hydrocolloids. 2014;39:151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Shi T., Liu H., Song T., Xiong Z., Yuan L., McClements D.J., Gao R. Use of l-arginine-assisted ultrasonic treatment to change the molecular and interfacial characteristics of fish myosin and enhance the physical stability of the emulsion. Food Chemistry. 2021;342 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutariya S.G., Salunke P. Effect of hyaluronic acid on milk properties: Rheology, protein stability, acid and rennet gelation properties. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;131 doi: 10.3390/foods12050913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Kejing Y., Zhang S., Yi J., Zhu Z., Decker E.A., McClements D.J. Impact of tea polyphenols on the stability of oil-in-water emulsions coated by whey proteins. Food Chemistry. 2021;343 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Tian H.Y., Xiang D. Stabilizing the oil-in-water emulsions using the mixtures of dendrobium officinale polysaccharides and gum arabic or propylene glycol alginate. Molecules. 2020;25(3) doi: 10.3390/molecules25030759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Li Y., Sun J., Qiao C., Ho H., Huang M., Huang H. Synergistic effect of preheating and different power output high-intensity ultrasound on the physicochemical, structural, and gelling properties of myofibrillar protein from chicken wooden breast. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 2022;86 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Li Y., Zhang Y.M., Huang M., Xu X.L., Ho H., Sun J.X. Improving physicochemical properties of myofibrillar proteins from wooden breast of broiler by diverse glycation strategies. Food Chemistry. 2022;382 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Yang J., Shao G., Qu D., Zhao H., Yang L., Zhu D. Soy protein isolated-soy hull polysaccharides stabilized O/W emulsion: Effect of polysaccharides concentration on the storage stability and interfacial rheological properties. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;101 [Google Scholar]

- West R., Rousseau D. Regression modelling of the impact of confectioner's sugar and temperature on palm oil crystallization and rheology. Food Chemistry. 2019;274:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.08.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Li A., Li X., Sun L., Guo Y. An overview of classifications, properties of food polysaccharides and their links to applications in improving food textures. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2020;102:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yu C., Li S., Sun S., Yan H., Zou H. Modification of emulsifying properties of mussel myofibrillar proteins by high-intensity ultrasonication treatment and the stability of O/W emulsion. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2022;641 [Google Scholar]

- Zang X., Wang J., Yu G., Cheng J. Addition of anionic polysaccharides to improve the stability of rice bran protein hydrolysate-stabilized emulsions. LWT. 2019;111:573–581. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Cai X.X., Ding L., Wang S.Y. Effect of pH, ionic strength, chitosan deacetylation on the stability and rheological properties of O/W emulsions formulated with chitosan/casein complexes. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;111 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Li L. The interaction between anionic polysaccharides and legume protein and their influence mechanism on emulsion stability. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;131 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Yang L., Hu S., Liu X., Duan X. Consequences of ball-milling treatment on the physicochemical, rheological and emulsifying properties of egg phosvitin. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;95:418–425. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.Y., Wang P., Zou Y.F., Li K., Kang Z.L., Xu X.L., Zhou G.H. Effect of pre-emulsification of plant lipid treated by pulsed ultrasound on the functional properties of chicken breast myofibrillar protein composite gel. Food Research International. 2014;58:98–104. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.