Abstract

Research has proved learner engagement is a strong predictor of academic achievement, especially in the online learning environment. The lack of any reliable and valid instrument to measure this construct in the context of online education made the researchers of the current study develop and validate a potential measurement inventory to assess EFL learners' engagement in the online learning environment. For this purpose, a comprehensive review of the related literature and careful investigation of the existing instruments were carried out to find the theoretical constructs for learner engagement which led to the development of a 56-item Likert scale questionnaire. The newly developed questionnaire was piloted with 560 female and male EFL university students selected based on nonprobability convenience sampling. The results of the factor analysis indicated the reduction of items to 48 loaded on three main components, namely behavioral engagement (15 items), emotional engagement (16 items), and cognitive engagement (17 items). The results also revealed that the newly developed questionnaire enjoyed a reliability index of 0.925. The findings of the current study will undoubtedly help teaching practitioners assess EFL learners’ engagement in the online learning context and make principled decisions when it comes to learners' engagement.

Keywords: Behavioral engagement, Cognitive engagement, Emotional engagement, Learner engagement, Online learning, Student engagement questionnaire

Introduction

The past decades have witnessed a revolution in the education system due to the rapid advancement of information technologies that resulted in the integration of different media into the computer system and the application of digital technologies and virtual communication in teaching and learning. Now, more people and institutions have access to computers and technologies thanks to this advancement. Not only these technologies are used for presentation and practice, but also interaction and collaboration. Moreover, the implementation of computers into educational contexts to promote the efficacy of teaching and learning gained attention. As a result of this growing use of computers, the Internet, and different forms of distance learning, language educators and learners express an increasing interest in the use of computers as a supportive and facilitator tool for language learning [86].

Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic leads to schools and universities being closed all over the globe. Consequently, there is a dramatic change in education with the widespread use of online learning whereby education occurs remotely via various digital platforms. Therefore, this pandemic results in the dire need of applying technologies such as laptops, tablets, smartphones, and Wi-Fi connections in education [46]. Online learning provides learners with opportunities to learn a language more independently [83]. To build such fruitful and efficient online learning, different factors come into play, such as learners’ engagement [67], which is integral in the process of teaching and learning since it is a way of encouraging students’ active participation in learning-related activities, sharing ideas and experiences and accomplishing collaborative tasks [66].

The concept of learner engagement has gained increased attention over the last decades. Despite the popularity of this topic, there is a lack of consensus on the conceptual definition of learner engagement and its types [20]. In the language education field particularly, questions remain about why this construct is so critical and how it can be developed [20, 70, 74, 76]. In spite of the restrictions in the existing literature, there is constant evidence that engagement is closely linked to successful learning [43]. Learner engagement is a multidimensional construct defined as learners’ active participation, involvement, and emotional quality in learning-related activities [20]. In the online education context, student engagement deals with the energy and time invested by the students in the online learning process [55]. Several studies considered engagement as one of the strong predictors of students’ academic accomplishment [93]. The multidimensional construct of engagement has been defined as having three or four dimensions [9]. Most scholars theorized the construct of student engagement as three separate but inter-reliant dimensions, comprising behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement [31, 44, 54]. In the online learning environment, behavioral engagement reflects learning-related activities such as participating in online interactions and communications and asking questions, cognitive engagement is concerned with mental efforts that learners make to learn a particular skill or acquire intricate knowledge, while emotional engagement deals with students’ positive emotional feelings about their class, peers and teachers, and their online courses [54]. Highly engaged learners are more successful in absorbing knowledge and skills. Therefore, it is crucial to promote learners’ engagement, especially in online classes [58].

Considering the significance of learners’ engagement and its important role in academic achievement, it is worth investigating learners’ level of engagement. For doing so, a valid and reliable instrument is needed. Researchers have utilized various instruments for measuring learners’ engagement such as portfolios, semi-structured interviews [27], observation [3, 47], course and professor evaluation [41]. However, implementing these instruments for investigating learner engagement in an online education environment is not feasible and they are mainly utilized for providing qualitative data. Hence, an instrument that is easily applicable in an online learning context that provides quantitative data is required. Numerous researchers have developed and validated instruments for evaluating learners’ engagement [6, 8, 10, 22, 32, 37, 48, 50, 56, 96, 100, 101]. However, some of these instruments focus on measuring just one or two learner engagement dimensions (e.g., [6, 48]). Most of the instruments investigate learners' general engagement (e.g., [8, 96]) instead of engagement in specific subject areas (e.g., [50, 100]) such as foreign language learning or science. In addition, these instruments are developed to measure school students’ engagement in actual and face-to-face classes [10, 101] rather than in the online learning environment.

A plethora of research proved the domain specificity of motivational constructs, especially situation- and subject-relevant ones [102]. Some primary studies also suggest that student engagement is domain-specific; however, more research is required to identify how this concept varies across subject areas [57]. Sinatra et al. [90], for instance, stated that epistemological cognition, participation in science and mathematics activities, attitudes, and topical reactions are domain-specific features of science engagement that are essential to take into account.

Despite the studies mentioned above, learners’ engagement is not fully investigated in the online educational context due to the lack of reliable and valid instruments for assessing this construct in online learning. Therefore, the goal of the current attempt is to create and validate an instrument to evaluate learners' engagement in the online educational setting. The novelty of this study not only relies on developing and validating a multidimensional questionnaire exploring learners’ behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement but also focuses on assessing learners’ engagement in the context of online education as one of the main educational concerns in today’s world affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Literature review

Learner engagement

The concept of learner engagement has gained increasing attention in educational literature in recent years. Relied on educational psychology, learner engagement reflects learners’ behavior and their psychological relationships with education or established learning [72]. Learner engagement is also defined as learners’ attention, interest, and self-confidence during learning or receiving instruction. To put it another way, engagement is regarded as a motivational behavior revealing the learners’ motivation for learning and knowledge enhancement [77].

Empirical studies revealed a positive correlation between learners’ engagement and academic performance and achievement [31, 72, 81], and learners who involve actively in tasks planned by educational institutions advantage more than those who do not do as much [35, 51, 72]. Accordingly, Kidwell [49] asserted that “If students are not engaged in the learning process, all the testing, data analysis, teacher meetings and instructional minutes will not motivate students to learn” (p. 30).

Scholars have introduced various typologies of engagement and some researchers have employed a twofold engagement typology, recognizing the behavioral and emotional dimensions of this concept [98]. The twofold engagement typology acknowledged by Finn [28] was established based on his participation-identification model. According to this model, learner engagement reflects learners’ active involvement and participation in classroom activities, along with their sense of treasuring and belonging to educational institutions.

Other scholars theorize learner engagement as threefold, including behavioral, emotional, and cognitive dimensions in which each dimension correlates with the other, and the three create a single compound construct. In the same vein, Fredricks et al. [31] described learner engagement as “a multi-dimensional construct of motivation that includes three interrelated components: behavioral, emotional, and cognitive” (p. 305). This suggests that these three dimensions should be considered while examining learners’ engagement. According to Fredricks et al. [31] “behavioral engagement involves doing work and following the rules, emotional engagement incorporates interest, value, and emotions; and cognitive engagement includes motivation, effort, and strategy use” (p. 306).

Moreover, Philp and Duchesne [76] conceptualized a task engagement model including four dimensions: cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social. While cognitive engagement consists of procedures like constant attention, emotional engagement reflects the expression of different emotions such as eagerness, interest, satisfaction, dissatisfaction, apprehension, and frustration. Behavioral engagement is described as continuing task as demonstrated by the extent of on-task talk, whereas social engagement refers to the degree of interaction and reciprocality between learners while doing task-based interaction [17].

Additionally, Dunleavy [25] examined Canadian learners’ engagement and conceptualized learner engagement as a three-dimensional construct including (1) behavioral (e.g., participation and attendance in school activities, attendance), (2) academic-cognitive (e.g., doing homework, responding to learning-related challenges), and (3) social-psychological (e.g., interest, motivation, sense of belonging). Furthermore, Reschly and Christenson [78] proposed a four-dimensional model of learner engagement comprising academic, behavioral, cognitive, and psychological which is not a common model. However, Appleton et al.’s [7] meta-analysis of numerous studies on learner engagement revealed that learner engagement is a meta-construct including multiple facets which have been mostly conceptualized as behavioral, emotional, and cognitive dimensions.

Theoretical framework

Fredricks et al.’s [31] three-dimensional model of learner engagement is adopted as the theoretical framework of the current study since this model is considered a more appropriate one in the language learning area due to the combination of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive dimensions that almost embraces some most-researched fields in language instruction research, such as motivation, learning strategies, affective factors, and cognitive qualities [104]. Fredricks et al. [31] analyzed various definitions and taxonomies of engagement and recognized three major dimensions of engagement: behavioral, emotional, and cognitive. These dimensions are defined and explained meticulously in the following section.

Behavioral engagement

According to the threefold model of learner engagement, behavioral engagement reflects learners’ active participation in learning-related tasks, such as doing homework or asking questions in class, attending in class, and showing a decent manner that relies on the notion of involvement, association with academic activities, and successful academic accomplishments [12]. Other researchers explain behavioral engagement in a positive manner, such as not showing troublemaking behavior, abiding by the rules, and following the classroom norms [29, 30].

Instances of behavioral engagement in language learning contexts contain learners’ intentional participation in speaking, interactional inventiveness, time on task, and perseverance on task without asking for support or guidance [76]. While all areas of engagement include some extent of action, current studies consider behavioral engagement as the amount of endeavor that learners make in learning activities, their involvement quality, and their active participation level in the process of learning [40]. Research that focused on learners’ behavioral engagement indicated that learners can either show positive behaviors (obeying the classroom rules), which are signs of a high level of learners’ behavioral engagement, or they can show negative behaviors (being troublemaking in the classroom), which are signs of low level of behavioral engagement or disengagement [71].

Considering the positive impact of behavioral engagement on learners’ achievement [89, 99], and on reducing learner dropout rates [80, 103], a considerable number of studies addressed recognizing the features of classrooms that are related to behavioral engagement. Two school-level features, namely school size and firm rules, have an excessive deal of research on their connection with learner behavioral engagement [88]. Though schools have a vital impact on learner behavioral engagement, engagement fluctuates by classroom within a school as well [14]. Consequently, numerous studies focused on finding classroom instructional factors that may affect learners’ behavioral engagement such as the quality and quantity of learners’ interactions with the teacher, peers, and content [71].

Emotional engagement

The second dimension of learner engagement is emotional engagement which deals with learners’ emotional reactions in the learning process. It is also defined as students’ feelings of interest, happiness, anxiety, and anger while accomplishing activities related to learner attainment [91]. That is to say, emotional engagement is the degree to which learners show a sense of concern about their learning and education [18] and their attitude toward school, teachers, and classmates [104]. It is apparent that actual emotional engagement impacts learners’ inclination to do the activity and creates an emotional attachment to the educational context [13].

In second language learning contexts, emotional engagement is often displayed in learners’ affective responses when they take part in language learning-related activities. Learners who are engaged emotionally are considered as having a “positive, purposeful, willing, and autonomous disposition” toward language-related learning activities, and peers [94], p. 247]. Declaration of positive emotions such as satisfaction, interest, and eagerness are supposed to be signs of learners’ emotional engagement; however, negative emotions such as apprehension, tediousness, frustration, and irritation reveal emotional disengagement [61].

Emotional engagement has a crucial effect on other dimensions of learner engagement due to the importance of subjective perceptions or attitudes that learners have during class activities or through language-related tasks [39]. Emotional engagement is, consequently, associated with learners’ points of view toward educational settings, the individuals in those settings, the learning activities, and their involvement in learning [40]. Pekrun [75] stated that emotions affect “a broad variety of cognitive processes that contribute to learning, such as perception, attention, memory, decision making, and cognitive problem solving” (p. 26), and Skinner and Pitzer [92] considered emotion as “the fuel for the kind of behavioral and cognitive engagement that leads to high-quality learning” (p. 33).

Cognitive engagement

Cognitive engagement is the third dimension of learner engagement that reflects implementing various learning strategies and self-regulation [20, 104]. Cognitive engagement is considered a mediator variable that has a positive and direct impact on the learners' academic achievement. It is also recognized as strategic and thoughtful to apply the required effort for comprehension of intricate ideas [34].

Cognitive engagement deals with learners’ mental energy, activity, and effort in the learning process. Learners are cognitively engaged when they show careful, discerning, and constant attention to accomplish a given activity or learning objective [40]. In the context of second or foreign language learning, studies on learner cognitive engagement focus chiefly on verbal manifestations such as peer interactions, learners’ questioning, reluctance and repetition, offering answers, expressing ideas, giving feedback, directing, and explaining. Along with such negotiation of meaning, other scholars consider language-related incidents as appropriate indicators of learners' cognitive engagement [52, 95]. Private speech, nonverbal communication, and exploratory talk that happen when learners try to make sense of learning are regarded as other indicators of this dimension. Besides these more concrete communications prompts, it is also likely to examine cognitive engagement via nonverbal signals such as eye movements, facial expressions, body language, and body positioning [40].

Online language learning

During the last 2 years, there has been a dramatic change in education due to the COVID-19 pandemic leading to the closure of educational institutions all over the globe and the sudden rise of online learning through which instruction takes place virtually on various digital platforms. Even before the COVID-19 outbreak, online learning had been a growing business in its own right in various educational fields and language learning was not an exception [82]. It is worth distinguishing between online learning approaches such as Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC) and Virtual classes. Although MOOCs have gained popularity over the past few years, the COVID-19 pandemic has made virtual classes almost universally adopted since they can meet a variety of pressing demands that arose as a result of the limits that were put in place. The name MOOC was first used by Cormier in 2008 and includes three key characteristics: first, they are open in that anyone may enroll and access the information, second, they are online courses, and third, they are massive in terms of the number of students they can accommodate [1]. According to another description, MOOC is an online course that offers free registration to users and has a publicly available curriculum with open-ended learning objectives [59].

On the other hand, virtual classes can be delivered in one of two ways: synchronously or asynchronously. In asynchronous virtual education, learning resources and materials are delivered asynchronously via platforms for learning management systems (LMS), such as Moodle or BB. The use of resources like email, discussion boards, blogs, wikis, or video/audio recordings can facilitate asynchronous online communication, which does not require the instructor and students to participate in real-time [42], whereas delivering course materials in real time is a part of the synchronous mode. Using synchronized software, students and teachers can converse verbally, type messages back and forth, upload PowerPoint presentations, send videos, or browse the web simultaneously [60]. Synchronous online learning, which is frequently supplemented by chat and video conferencing, is said to have the ability to aid e-learners in the formation of learning communities. It provides whiteboard, streaming video and audio, and file sharing [15, 79]. The synchronous conferencing sessions' nonverbal cues help learners feel more connected to and engaged with their classmates and teachers [4].

The context of online learning provides learners with flexible and self-paced learning without place and time restrictions [64, 65, 68] which results in the promotion of knowledge construction and the creation of online learning atmospheres that boost meaningful learner engagement [82]. Learning language, similar to other educational goals, is far more fruitful when joined with proper educational technology. The growing application of modern technology in educational contexts contributes to connecting teachers to learners, to resources, to professional content, and to systems planned to enhance their lessons and personalize instruction [62]. Research revealed that educational programs that take place in an online atmosphere are preferred by teachers because they seem to correlate with positive learners’ engagement with the teachers, and educational material and boost language learning [2, 46]. The main benefits of online classrooms are their flexibility, communication, and support for those with restricted movement or lack of resources. Such classes can enhance learners’ engagement and provide them with more opportunities for interaction along with their sense of community [38]. However, learners and teachers may encounter some challenges in online education such as (1) adaptability of teachers and learners (transition from traditional face-to-face education to online education may result in some struggle for teachers and learners) [73], (2) the lack of technological literacy (i.e., teachers and learners lack required knowledge and skills in applying computer and software in online classes) [53, 73], (3) the lack of technological infrastructure especially in developing countries [5], (4) the cost of online education, (5) classes time management (i.e., the online class takes a lot of time for teaching and assignment) [5, 36], (6) lack of motivation (i.e., both teachers and learners are less motivated in online classes due to the less active process of this classes compared with face-to-face education [5, 36, 87], and (7) learners’ engagement (i.e., students’ nature of engagement in online classes is considered the main challenge. Although some students actively engage in discussions and arguments in online classes, others incline toward being reluctant and just listening and observing [53]. Therefore, for online language learning to be successful, it is essential to make sure that learners are adequately engaged. It is extensively recognized that engagement is connected to improved productivity and learning advance. Some studies indicated that engagement is flexible, and appropriate instructive involvements, learning designs, and feedback can develop learner engagement [19, 69].

Eventually, given the significance of learner engagement as a robust predictor of learner academic accomplishment especially in the online education context, the review of the related literature, and previous studies provided here, the nonexistence of a comprehensive way of assessing EFL learners’ engagement in online learning was the gap targeted for which a questionnaire was developed and validated in the course of the present investigation.

Method

Participants

The participants of this study were 560 Iranian undergraduate university students of English majors studying at Karaj Islamic Azad University. In this sample, 53% of the participants were female and 47% were male between the ages of 18 and 25 years. The participants were selected through convenience sampling [11] to include the participants who were available and willing to take part in this study.

Instruments

A questionnaire was designed to assess EFL learners’ engagement in online classes. To determine the theoretical framework of the study and to develop the items of the questionnaire, a comprehensive review of related literature and a critical investigation of the existing questionnaires were done. To illustrate the purpose of the newly developed questionnaire and the way to answer its items, clear instruction was provided, and the rating scale was clarified as well. The first draft of the questionnaire included 56 items on a five-point Likert scale rating from never (rated 1) to always (rated 5).

Some items were constructed according to the previous study conducted by one of the researchers of the current study [63] focusing on EFL learners' progress from limited to elaborate behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement through conversation analysis techniques such as item 13 (When I do a task in the class, I try to relate the task to the prior knowledge). Some other items such as item 37 (When I do well in the class it’s because I work hard.) were borrowed and modified from frequently used questionnaires such as Appleton et al. [6] that have been recognized with psychometrically valid properties. This step is very crucial not only for generating the items but also for supporting the enhancement of reliability and validity evidence [23]. Additionally, some items are created by the researchers of the current study to best suit the online language learning contexts such as item 12 (I fully charge my telephone, laptop, and internet to not disconnect during the class in order to lose the material). Reviewing the related literature comprehensively and investigating the existing learner engagement questionnaires critically, an initial pool of 56 items was constructed assessing three constructs: behavioral (items 1–17), emotional (items 18–36), and cognitive (items 37–56).

Procedure

The researchers of the current study followed a standard, step-by-step process to develop a questionnaire for assessing EFL learners' engagement in online classes. This process was initiated with meticulous scrutiny of the related literature on numerous variables about various perceptional, methodological, and systematic variables. Accordingly, it was essential to develop an appropriate, efficient, and flexible framework for learner engagement. Reviewing the literature on learner engagement, a three-dimensional model of learner engagement focusing on behavioral, emotional, and cognitive dimensions [31] was selected from among various available frameworks on learner engagement. In order to operationalize the indicators and collect the questionnaire items, various existing questionnaires on learner engagement were investigated considering the three dimensions of learner engagement. In addition, some items are created and some other items were modified by the researchers to concern the online learning context.

Taken all together, the initial number of 56 five-point Likert scale questionnaire items (Appendix 1) was developed based on a comprehensive review of related literature and a thorough investigation of available questionnaires. Items were written in straightforward language without complexity in order to avoid any inconsistency between participants’ interpretation and scale intention. Furthermore, for examining the content validity of the newly developed questionnaire, a panel of experts was asked to evaluate the items and their appropriateness and relevance to the objectives of the study. Following their viewpoints and modifications, the ultimate items for the inventory were selected.

Moreover, to examine the reliability and construct validity of the questionnaire, it was piloted with 560 participants. Because of the COVID-19 outbreak, an online questionnaire implementing the Google Forms platform was conducted and distributed via email or other social media along with a brief overview of the purpose of the study and a description of the instrument. Students were given enough time to answer and also opportunities to edit their responses. In the process of designing the questionnaire, care was taken to make the questionnaire and its item as comprehensive as possible in terms of language and wording. In addition, researchers of the current study provide the participants with their email addresses to send them email in case of any questions. The researchers did not observe any difficulty in administering and collecting the questionnaire developed to measure engagement for a course during a semester for 15 sessions each lasting for 2 h. The ease with and also the speed of responding to the questionnaire and the availability of the researchers to assist students any time they face problems or the need for clarification give us the vision that the questionnaire can be utilized and adapted widely. Finally, for estimating the reliability and construct validity of the instrument, Cronbach’s alpha and exploratory factor analysis were run employing SPSS software.

Design

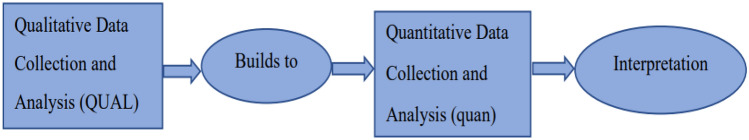

As mentioned before, this study is an attempt to design and develop a reliable and valid instrument to assess EFL learners' engagement in the online learning context. A sequential exploratory mixed methods design was used in this process. The main goal of using mixed methods research is often to join qualitative and quantitative approaches in a variety of ways and utilize each method's strength within a single inquiry [16]. An exploratory sequential mixed methods study consists of two phases, the first of which is the collection and analysis of the qualitative data. The quantitative data are then gathered and examined in the second phase using the findings of the previous phase. That is to say, a three-phase method should be used to create and construct a questionnaire, which includes looking at the qualitative data, creating the instrument, and then administering the instrument to a sufficient number of participants [16]. The design is demonstrated in the following figure (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Exploratory sequential mixed methods [16], p. 220]

Results

Reliability

This study aims at exploring the reliability and construct validity of the online classroom engagement questionnaire (OCEQ). The OCEQ has 56 items measuring three constructs of behavioral (items 1–17), emotional (items 18–36), and cognitive (items 37–56). Table 1 displays Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the overall OCEQ and its three components. The overall OCEQ enjoyed a reliability index of 0.897. The reliability indices for the behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagements were 0.881, 0.894, and 0.897 respectively.

Table 1.

Reliability statistics: online classroom engagement and its components

| Cronbach's Alpha | No. of items | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall OCEQ | 0.897 | 56 |

| Behavioral | 0.881 | 17 |

| Emotional | 0.894 | 19 |

| Cognitive | 0.897 | 20 |

It should be noted that Tseng et al. [97], Dörnyei and Taguchi [24] believe that 0.70 is the adequate reliability index for an instrument. George and Mallery [33] believe that “there is no set interpretation as to what is an acceptable alpha value. A rule of thumb that applies to most situations is: 0.9 = excellent, 0.8 = good, 0.7 = acceptable, 0.6 = questionable, 0.5 = poor and 0.5 = unacceptable” (p. 244). Based on these criteria, it can be concluded that the reliability indices (Table 1) for the OCEQ and its components were almost excellent.

Table 2 displays the item–total correlations for the three components of OCEQ. The results showed that all items had large, i.e., ≥ 0.50, contributions to their constructs except for: items 8 and 12 (behavioral engagement), items 10, 14, and 17 (emotional engagement), and items 9, 13, and 17 (cognitive engagement).

Table 2.

Item–total correlations: components of online classroom engagement questionnaire

| Behavioral | Item–total correlation | Emotional | Item–total correlation | Cognitive | Item–total correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beh1 | 0.692 | Emo1 | 0.642 | Cog1 | 0.715 |

| Beh2 | 0.633 | Emo2 | 0.661 | Cog2 | 0.627 |

| Beh3 | 0.631 | Emo3 | 0.667 | Cog3 | 0.679 |

| Beh4 | 0.698 | Emo4 | 0.674 | Cog4 | 0.629 |

| Beh5 | 0.626 | Emo5 | 0.714 | Cog5 | 0.745 |

| Beh6 | 0.617 | Emo6 | 0.662 | Cog6 | 0.700 |

| Beh7 | 0.643 | Emo7 | 0.642 | Cog7 | 0.642 |

| Beh8 | 0.035 | Emo8 | 0.616 | Cog8 | 0.646 |

| Beh9 | 0.615 | Emo9 | 0.658 | Cog9 | 0.033 |

| Beh10 | 0.676 | Emo10 | -0.079 | Cog10 | 0.699 |

| Beh11 | 0.667 | Emo11 | 0.625 | Cog11 | 0.751 |

| Beh12 | − 0.016 | Emo12 | 0.659 | Cog12 | 0.691 |

| Beh13 | 0.611 | Emo13 | 0.715 | Cog13 | 0.048 |

| Beh14 | 0.674 | Emo14 | 0.037 | Cog14 | 0.727 |

| Beh15 | 0.619 | Emo15 | 0.691 | Cog15 | 0.657 |

| Beh16 | 0.632 | Emo16 | 0.654 | Cog16 | 0.728 |

| Beh17 | 0.650 | Emo17 | 0.040 | Cog17 | − 0.033 |

| Emo18 | 0.710 | Cog18 | 0.742 | ||

| Emo19 | 0.693 | Cog19 | 0.653 | ||

| Cog20 | 0.743 |

Table 3 displays Cronbach’s alpha reliability indices after dropping these defective items out. The reliability index for the overall OCEQ increased to 0.925. The reliability indices for the behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagements increased to 0.921, 0.936, and 0.940 respectively. All these reliability indices can be considered excellent based on the criteria discussed above.

Table 3.

Reliability statistics: online classroom engagement and its components (after removing defective items)

| Cronbach's Alpha | No. of items | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall OCEQ | 0.925 | 48 |

| Behavioral | 0.921 | 15 |

| Emotional | 0.936 | 16 |

| Cognitive | 0.940 | 17 |

Construct validity

Tables 4, 5, and 6 display the results of the construct validity of the OCEQ. Based on the results displayed in Table 4, it can be concluded that the present sample size of 560 was adequate for running factor analysis (KMO = 0.944 > 0.60) and the significant results of the sphericity test (χ2 (1540) = 15,613.78, p < 0.05); the correlation matrix based on which the factors were extracted was a factorable one.

Table 4.

KMO and Bartlett's test: online classroom engagement questionnaire

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy | 0.944 |

| Bartlett's test of sphericity | |

| Approx. Chi-Square | 15,613.781 |

| df | 1540 |

| Sig. | 0.000 |

Table 5.

Total variance explained: online classroom engagement questionnaire

| Factor | Initial eigenvalues | Extraction sums of squared loadings | Rotation sums of squared loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 11.460 | 20.464 | 20.464 | 11.005 | 19.651 | 19.651 | 9.062 | 16.182 | 16.182 |

| 2 | 7.666 | 13.690 | 34.154 | 7.217 | 12.888 | 32.539 | 8.009 | 14.301 | 30.483 |

| 3 | 6.544 | 11.685 | 45.839 | 6.057 | 10.816 | 43.355 | 7.170 | 12.804 | 43.287 |

| 4 | 1.253 | 2.238 | 48.077 | 0.501 | 0.894 | 44.249 | 0.483 | 0.862 | 44.149 |

| 5 | 1.202 | 2.146 | 50.223 | 0.451 | 0.805 | 45.054 | 0.443 | 0.792 | 44.941 |

| 6 | 1.150 | 2.053 | 52.277 | 0.407 | 0.727 | 45.781 | 0.434 | 0.775 | 45.716 |

| 7 | 1.081 | 1.931 | 54.208 | 0.378 | 0.675 | 46.456 | 0.392 | 0.699 | 46.415 |

| 8 | 1.062 | 1.897 | 56.105 | 0.364 | 0.650 | 47.106 | 0.387 | 0.691 | 47.106 |

Extraction method: principal axis factoring

Table 6.

Rotated factor matrix: online classroom engagement questionnaire (after removing items with low contributions)

| Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Cog14 | 0.774 | ||

| Cog11 | 0.772 | ||

| Cog5 | 0.772 | ||

| Cog18 | 0.766 | ||

| Cog20 | 0.757 | ||

| Cog16 | 0.755 | ||

| Cog1 | 0.750 | ||

| Cog6 | 0.745 | ||

| Cog10 | 0.728 | ||

| Cog12 | 0.725 | ||

| Cog3 | 0.708 | ||

| Cog19 | 0.693 | ||

| Cog15 | 0.688 | ||

| Cog8 | 0.675 | ||

| Cog7 | 0.674 | ||

| Cog4 | 0.661 | ||

| Cog2 | 0.652 | ||

| Emo13 | 0.742 | ||

| Emo5 | 0.740 | ||

| Emo18 | 0.738 | ||

| Emo19 | 0.736 | ||

| Emo15 | 0.731 | ||

| Emo4 | 0.719 | ||

| Emo3 | 0.703 | ||

| Emo2 | 0.702 | ||

| Emo16 | 0.694 | ||

| Emo6 | 0.691 | ||

| Emo9 | 0.685 | ||

| Emo12 | 0.681 | ||

| Emo7 | 0.670 | ||

| Emo1 | 0.662 | ||

| Emo11 | 0.652 | ||

| Beh4 | 0.728 | ||

| Beh1 | 0.721 | ||

| Beh10 | 0.720 | ||

| Beh14 | 0.719 | ||

| Beh11 | 0.704 | ||

| Beh7 | 0.698 | ||

| Beh17 | 0.690 | ||

| Beh16 | 0.672 | ||

| Beh6 | 0.668 | ||

| Beh2 | 0.661 | ||

| Beh3 | 0.654 | ||

| Beh9 | 0.653 | ||

| Beh5 | 0.652 | ||

| Beh13 | 0.647 | ||

| Beh15 | 0.646 | ||

Eight factors accounted for 47.10% of the variance (Table 5). That is to say, the 56 items of the OCEQ measured eight factors with an accuracy of 47.10% were extracted.

The results of the rotated factor matrix (Table1, Appendix 1) indicated that all items related to cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagements loaded under the first, second, and third factors respectively, except for the following items whose factor loadings were lower than 0.30; cognitive (items 9, 13, and 17), behavioral (item 8), and emotional (items 10 and 14). Three items, i.e., emotional 8 and 17, behavioral 12, loaded under two factors.

After removing the items which had low contributions to their factors, or had loadings on more than one factor, the factor loadings became as displayed in Table 6. The items related to cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagements are loaded under the first, second, and third factors. All factor loadings enjoyed large effect sizes; i.e., ≥ 0.50.

Discussion

The current study aimed to design and validate a measurement instrument to assess EFL learners’ engagement in the online learning context. After a comprehensive review of the related literature and scrutiny of the existing instruments, the theoretical constructs concerning EFL learners’ behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement were obtained and were later employed as the underpinning theoretical framework of the current attempt that resulted in the development of a valid and reliable questionnaire. To examine the psychometric qualities of the newly developed questionnaire, it was administered to 560 undergraduate university students studying English majors at Karaj Islamic Azad University. The results of Cronbach’s alpha revealed that the overall OCEQ enjoyed a reliability index of 0.897. The reliability indices for the behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagements were 0.881, 0.894, and 0.897, respectively. Moreover, the results of the factor analysis revealed no construct-irrelevant factor, and all items contributed to their constructs except for items 8 and 12 (behavioral engagement), items 10, 14, and 17 (emotional engagement), and items 9, 13, and 17 (cognitive engagement). After eliminating these defective items, the overall OCEQ reliability index improved to 0.925. The reliability indices for the behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagements increased to 0.921, 0.936, and 0.940 respectively.

In spite of the existence of numerous instruments for assessing learners’ engagement, some instruments that measure engagement, such as the UWES developed by Schaufeli and Bakker [84] have been criticized due to the lack of appropriate construct definitions and dimensionality to their application to university students. The results of the present study are supported by those of a study conducted by Appleton et al. [6] who developed the Student Engagement Instrument (SEI), which is one of the most prominent instruments utilized for measuring learner engagement. However, this 35-item instrument is a four-Likert scale planned to assess just two dimensions of school students' engagement namely cognitive and psychological engagement.

The outcomes of the present study are in line with Gargallo et al.’s [32] study in which the Student Engagement Questionnaire developed by Kember and Leung [48] including 17 items on 6 points Likert scale was adopted to assess the behavioral dimension of the classroom. This instrument was validated by Gargallo et al. [32] with a Spanish sample of 805 university students. This questionnaire was utilized for two main purposes: (1) to analyze university students’ capabilities to acquire during the course of study and (2) to evaluate the learning environment created by the teacher in class to facilitate the learning process. Therefore, this inventory focuses on just one aspect of learner engagement, behavioral engagement.

The results of the current study are in agreement with those of previous studies concerning the main factors of learner engagement such as Balfanz [10] who designed the High School Survey of Student Engagement which includes 121 items measuring three dimensions of cognitive engagement (65 items), behavioral engagement (17 items), and emotional engagement (39 items) of secondary school students. Despite the wide use of this instrument, it lacks information on its reliability and validity. Similarly, Maroco et al. [56] developed the University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI) drawing on the conceptualization of engagement as a multifaceted concept, comprising emotional, cognitive, and behavioral engagement. The participants of this study were 609 Portuguese university students majoring in Social Sciences, Biological Sciences, and Engineering. The initial USEI included 35 items but the validated USEI was composed of 15 items loaded on three main components of learner engagement.

All the instruments mentioned above were designed and developed to measure learners’ engagement in actual and face-to-face classrooms. Despite the importance of learners’ engagement in the online learning context, there are very few instruments for assessing this crucial construct in the context of online education. The results of the current study are also consistent with those of the study conducted by Dixson [22] in which the online Student Engagement scale (OSE) was developed. The OSE includes 19 items of a 5-point Likert scale that reports how well thought, behavior, and the feeling were characteristic of them or their behavior. This instrument was utilized to find the correlation between learners' self-reports of engagement and following data of learner behaviors in an online course. According to the findings, learner engagement on the OSE significantly correlated with two types of student behaviors: observational learning behaviors and application learning behaviors.

As stated earlier, although numerous investigations were conducted with a focus on learner engagement, no studies were carried out to design and validate a questionnaire utilizing which EFL learners’ engagement in the online learning context can be evaluated. Therefore, explorations such as the current one will be very beneficial to enable those who are responsible for improving learners’ engagement in online learning environments.

Conclusion

Learner engagement and academic achievements are so inevitably intertwined that is really hard to conceptualize learners’ accomplishments without considering the crucial role of learner engagement, especially in the online learning context where learners may feel isolated. In this regard, teaching practitioners are required to be able to measure learners’ level of engagement and enhance it in order to achieve desired learning outcomes. Consequently, developing and validating an assessment inventory for assessing EFL learners’ engagement in the online educational context lies at the heart of the current attempt. This study resulted in the development of a questionnaire with a final number of 48 items across three components namely behavioral, emotional and cognitive engagement which were scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 representing the extent to which the statement was reckoned to be true for the respondent learner.

The results of the current attempt will potentially be beneficial for several stakeholders in the fields of English language teaching and learning. Teachers, supervisors, administrators, course designers, curriculum and materials developers, and policymakers all may take advantage of the results of this study since they will be equipped with a reliable and valid instrument to assess EFL learners’ engagement in the online learning environment. To achieve the desired learning outcomes, teachers, for instance, will be able to measure their students’ level of engagement during the online course of study and provide learners with more engaging activities and tasks. Considering the importance of the content of materials in online courses, course materials developers will also be cognizant of Iranian EFL learners’ level of engagement to develop more engaging materials. Administrators and policymakers can use this questionnaire as a yardstick to evaluate the efficiency of the online learning environment when it comes to learner engagement.

However, the researchers of the current study tried to follow established methods to develop and validate this measurement inventory, some caveats need to be noted regarding this study. First, even though both inductive and deductive approaches were implemented to substantiate the conceptualization of learner engagement, some intervening matters were not controlled due to time and practical restrictions. For instance, including a larger sample size or carrying out the research countrywide could result in better outcomes. In addition, the participants of this study were selected through convenience sampling which is considered a limitation. Therefore, other scholars can replicate and obtain a better understanding of learner engagement in the online learning environment and more generalizable results by implementing other sampling approaches. Moreover, the qualitative part of the present study was mainly carried out through a deep review of the related literature and a careful investigation of the existing instruments. The lack of data triangulation and usage of different sources of data collection is another limitation. The use of various data collection sources can open up new research horizons and reveal more research areas. Future studies can reflect on and identify various aspects of learner engagement in the online learning context by observing their classes or providing them with focus group discussions.

Furthermore, it should be noted that individual differences are not considered in this study since it was carried out during the COVID-19 outbreak. Hence, some research procedures such as piloting the questionnaire were conducted online. Consequently, paying attention to the participants’ individual differences was not possible. Therefore, the findings of future studies would certainly complement those of the current study in terms of controlling the impact of individual differences and clarifying how these features may contribute to learners’ engagement in the online learning environment.

Appendix 1

Learner Engagement in Online Learning Questionnaire

| Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral engagement | ||||||

| 1 | I treat my classmates and teachers with respect either in Skyroom or in the WhatsApp group | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | I comply with the rules in the class by doing all my homework and being punctual | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | I work with great effort to answer the teacher’s questions by typing in the chatbox or by clicking the Raising Hand icon | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | When I encounter a hard homework exercise, I continue working on it till I think I’ve answered it | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | I participate actively in the activities such as presenting a lecture and participating in class discussions by asking the teacher to turn on my microphone | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | When I’m in class, my mind wanders | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7 | I discover that when the teacher is teaching, I think of other things and don't really listen to what is being said | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | When I am in class, I listen carefully | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | I turned in a homework assignment late or not at all | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10 | I never use my mother tongue in class, I keep speaking English | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11 | When I do not understand something in class, I request the teacher to clarify it | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12 | I fully charge my telephone, laptop, and internet to not disconnect during the class in order to lose the materials | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 13 | When I do a task in class, I try to relate the task to prior knowledge | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 14 | I tutored or taught the class materials to other students in the WhatsApp group after the class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 15 | When I participate in class discussions or present a lecture, I pause frequently to remember a word or I laugh | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 16 | I fully attend the class by affirming the teacher by typing “yes” or “that’s right” in the chatbox | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 17 | I speak fluently in class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Emotional engagement | ||||||

| 18 | I enjoy learning new things in online classes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 19 | The online class is one of my favorite places to be | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 20 | When I run out of the internet or lose the connection, I worry a lot about it | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 21 | I enjoy learning new things in class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 22 | When I have a project to do, I worry a lot about it not being disconnected | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 23 | My teacher praises me most of the time when I work hard | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 24 | I am interested in the work, discussions, and exercises in my class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 25 | When I’m not interested in the class I excuse myself for a camera or microphone | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 26 | When the teacher wants to teach new things, I complain by typing “no, please” | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 27 | I feel relaxed in doing exercises or during a discussion | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 28 | I believe I can do it well during answering the exercise | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 29 | I am all ears when my teacher teaches a new thing | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 30 | My classmates always affirm my correct answers by typing “yes” or “very good” | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 31 | Students in my class are there for me when I need them | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 32 | I believe in myself when I want to present a lecture | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 33 | When I present a lecture, I need my teacher’s affirmation by saying “that’s right” or nodding her head while her camera is on | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 34 | I Volunteer to present in the class by clicking on the Raising Hand icon | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Cognitive engagement | ||||||

| 35 | Because I work hard, I succeed in class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 36 | I check my classwork to ensure that I have done it correctly | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 37 | When I study for an exam, I attempt to combine the information from the book and the class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 38 | Finding the main ideas of a text is difficult for me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 39 | When my classmates do an exercise or present a lecture, I try to justify their answers or lecture | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 40 | When I study or learn new things, I attempt to put the ideas in my own words | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 41 | I make my own examples to understand the important concepts I learn from the class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 42 | When I study for a test, I repeat the important points several times | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 43 | When I am studying a topic, I try to connect everything properly | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 44 | When I am studying my coursebook, I try to outline its chapters to learn better | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 45 | I try to give directions to my classmates when they do not know how to do the task | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 46 | When lessons are difficult, I either stop studying or study only the easy parts | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 47 | I work on practice exercises and answer the end-of-chapter questions even when I don't have to | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 48 | Even when lessons are uninteresting, I continue studying till I finish | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 49 | I try to use dictionaries or reference books in doing tasks and exercises | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 50 | I prevent exchanging ideas with my peers or teachers during a discussion | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 51 | I attempt to think carefully about topics and find what I’m expected to learn from them, instead of studying topics by just reading them over | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 52 | When I am studying course materials, I try to join different pieces of information together in innovative ways | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 53 | When I finish working on an exercise, I check my answer to see if it is reasonable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 54 | English class is important for achieving my future goals | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

1 = never or almost never; 2 = rarely; 3 = sometimes; 4 = often; and 5 = always or almost always.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Adham RS, Lundqvist KO. MOOCS as a method of distance education in the Arab world–a review paper. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2015;18(1):123–139. doi: 10.1515/eurodl-2015-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmadi RM. The use of technology in English language learning: a literature review. Int. J. Res. Engl. Educ. 2018;3(2):115–125. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alimoglu MK, Sarac DB, Alparslan D, Karakas AA, Altintas L. An observation tool for instructor and student behaviors to measure in-class learner engagement: a validation study. Med. Educ. Online. 2014;19(1):24037. doi: 10.3402/meo.v19.24037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Nofaie H. Saudi University students’ perceptions towards virtual education during Covid-19 PANDEMIC: a case study of language learning via blackboard. Arab World Engl. J. (AWEJ) 2020;11:4–20. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol11no3.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amalia NH, Atmowardoyo H, Abduh A. The challenges of teaching and learning English faced by the English teachers and students during the Covid-19 pandemic at SMP PGRI Barembeng. JTechLP J. Technol. Lang. Pedagogy. 2022;1(2):158–171. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appleton JJ, Christenson SL, Kim D, Reschly AL. Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: validation of the student engagement instrument. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006;44(5):427–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appleton JJ, Christenson SL, Furlong MJ. Student engagement with school: critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychol. Sch. 2008;45(5):369–386. doi: 10.1002/pits.20303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assunção H, Lin SW, Sit PS, Cheung KC, Harju-Luukkainen H, Smith T, Maloa B, Campos JADB, Ilic IS, Sposito G, Francesca FM, Marôco J. University student engagement inventory (USEI): transcultural validity evidence across four continents. Front. Psychol. 2020;10:2796. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagheri M, Mohamadi Zenouzagh Z. Comparative study of the effect of face-to-face and computer mediated conversation modalities on student engagement: speaking skill in focus. Asian Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 2021;6(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balfanz R. Can the American high school become an avenue of advancement for all? Future Child. 2009;19(1):17–36. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Best JW, Kahn JV. Research in Education. London: Pearson Education Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connell JP. Context, self, and action: a motivational analysis of self-system processes across the life span. In: Cicchetti D, Beeghly M, editors. The Self in Transition: Infancy to Childhood. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Mental Health and Development. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 61–97. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connell JP, Wellborn JG. Competence, autonomy and relatedness: a motivational analysis of self-system processes. In: Gunnar M, Sroufe LA, editors. Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology: Self Processes and Development. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. pp. 43–77. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper KS. Eliciting engagement in the high school classroom: a mixed-methods examination of teaching practices. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2014;51(2):363–402. doi: 10.3102/0002831213507973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornelius S. Facilitating in a demanding environment: experiences of teaching in virtual classrooms using web conferencing. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2014;45(2):260–271. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cresswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 4. New York: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dao P, McDonough K. Effect of proficiency on Vietnamese EFL learners’ engagement in peer interaction. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018;88:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2018.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis HA, Summers JJ, Miller LM. An Interpersonal Approach to Classroom Management: Strategies for Improving Student Engagement. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dewan MAA, Murshed M, Lin F. Engagement detection in online learning: a review. Smart Learn. Environ. 2019;6(1):1–20. doi: 10.1186/s40561-018-0080-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dincer A, Yeşilyurt S, Noels KA, Vargas Lascano DI. Self-determination and classroom engagement of EFL learners: a mixed-methods study of the self-system model of motivational development. SAGE Open. 2019;9(2):1–15. doi: 10.1177/2158244019853913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding Y, Zhao T. Emotions, engagement, and self-perceived achievement in a small private online course. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2020;36(4):449–457. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixson MD. Measuring student engagement in the online course: the online student engagement scale (OSE) Online Learn. 2015;19(4):1–15. doi: 10.24059/olj.v19i4.561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dörnyei Z. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration, and Processing. 2. New York: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dörnyei Z, Taguchi T. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration, and Processing. New York: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunleavy J. Bringing student engagement through the classroom door. Educ. Can. 2008;48(4):23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farizka NM, Santihastuti A, Suharjito B. Students’ learning engagement in writing class: a task-based learning. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. Linguist. 2020;5(2):203–212. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farrell O, Brunton J. A balancing act: a window into online student engagement experiences. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020;17(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s41239-020-00199-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finn JD. Withdrawing from school. Rev. Educ. Res. 1989;59:117–142. doi: 10.3102/00346543059002117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finn JD, Pannozzo GM, Voelkl KE. Disruptive and inattentive-withdrawn behavior and achievement among fourth graders. Elem. Sch. J. 1995;95:421–434. doi: 10.1086/461853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finn JD, Rock DA. Academic success among students at risk for school failure. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997;82(2):221–234. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH. School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004;74:59–109. doi: 10.3102/00346543074001059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gargallo B, Suárez-Rodríguez JM, Almerich G, Verde I, Iranzo MÀC. The dimensional validation of the student engagement questionnaire (SEQ) with a Spanish university population. Students’ capabilities and the teaching-learning environment. An. Psicol. 2018;34(3):519. doi: 10.6018/analesps.34.3.299041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.George D, Mallery P. IBM SPSS Statistics 26 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. New York: Routledge; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghanizadeh A, Amiri A, Jahedizadeh S. Towards humanizing language teaching: error treatment and EFL learners' cognitive, behavioral, emotional engagement, motivation, and language achievement. Iran. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2020;8(1):129–149. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gordon J, Ludlum J, Hoey JJ. Validating NSSE against student outcomes: Are they related? Res. High. Educ. 2008;49(1):19–39. doi: 10.1007/s11162-007-9061-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta MM. Impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on classroom teaching: challenges of online classes and solutions. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021;10:155. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1104_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Handelsman M, Briggs W, Sullivan N, Towler A. A measure of college student course engagement. J. Educ. Res. 2005;98(3):184–191. doi: 10.3200/JOER.98.3.184-192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hazaymeh WA. EFL students’ perceptions of online distance learning for enhancing English Language learning during Covid-19 pandemic. Int. J. Instr. 2021;14(3):501–518. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henry A, Thorsen C. Disaffection and agentic engagement: ‘redesigning’ activities to enable authentic self-expression. Lang. Teach. Res. 2020;24(4):456–475. doi: 10.1177/1362168818795976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiver P, Al-Hoorie AH, Vitta JP, Wu J. Engagement in language learning: a systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Lang. Teach. Res. 2021 doi: 10.1177/13621688211001289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hollister B, Nair P, Hill-Lindsay S, Chukoskie L. Engagement in online learning: student attitudes and behavior during COVID-19. Front. Educ. 2022;7:851019. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.851019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang JH, Hsiao TT, Chen YF. The effects of electronic word of mouth on product judgment and choice: the moderating role of the sense of virtual community 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012;42(9):2326–2347. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00943.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jang H, Kim EJ, Reeve J. Why students become more engaged or more disengaged during the semester: a self-determination theory dual-process model. Learn. Instr. 2016;43:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jung Y, Lee J. Learning engagement and persistence in massive open online courses (MOOCS) Comput. Educ. 2018;122:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung E, Kim D, Yoon M, Park S, Oakley B. The influence of instructional design on learner control, sense of achievement, and perceived effectiveness in a supersize MOOC course. Comput. Educ. 2019;128:377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawinkoonlasate P. Online language learning for Thai EFL learners: an analysis of effective alternative learning methods in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2020;13(12):15–26. doi: 10.5539/elt.v13n12p15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelly PA, Haidet P, Schneider V, Searle N, Seidel CL, Richards BF. A comparison of in-class learner engagement across lecture, problem-based learning, and team learning using the STROBE classroom observation tool. Teach. Learn. Med. 2005;17(2):112–118. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1702_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kember D, Leung DYP. Development of a questionnaire for assessing students’ perceptions of the teaching and learning environment and its use in quality assurance. Learn. Environ. Res. 2009;12(1):15–29. doi: 10.1007/s10984-008-9050-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kidwell C. The impact of student engagement on learning. Leadership. 2010;39(4):28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kong Q, Wong N, Lam C. Student engagement in mathematics: development of instrument and validation of construct. Math. Educ. Res. J. 2003;15(1):4–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03217366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuh GD. What we're learning about student engagement from NSSE: benchmarks for effective educational practices. Change Mag. High. Learn. 2003;35(2):24–32. doi: 10.1080/00091380309604090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lambert C, Philp J, Nakamura S. Learner-generated content and engagement in second language task performance. Lang. Teach. Res. 2017;21(6):665–680. doi: 10.1177/1362168816683559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li D. The shift to online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic: benefits, challenges, and required improvements from the students’ perspective. Electron. J. E-Learn. 2022;20(1):1–18. doi: 10.34190/ejel.20.1.2106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luan L, Hong JC, Cao M, Dong Y, Hou X. Exploring the role of online EFL learners’ perceived social support in their learning engagement: a structural equation model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1855211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma J, Han X, Yang J, Cheng J. Examining the necessary condition for engagement in an online learning environment based on learning analytics approach: the role of the instructor. Internet High. Educ. 2015;24:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2014.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maroco J, Maroco AL, Campos JADB, Fredricks JA. University student’s engagement: development of the University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI) Psicol. Reflex. Crít. 2016 doi: 10.1186/s41155-016-0042-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martin AJ. Enhancing student motivation and engagement: the effects of a multidimensional intervention. Contem. Educ. Psychol. 2008;33(2):239–269. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin F, Bolliger DU. Engagement matters: student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learn. 2018;22(1):205–222. doi: 10.24059/olj.v22i1.1092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McAulay A, Stewart B, Siemens G. The MOOC Model for Digital Practice. Charlottetown: University of Prince Edward Island; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 60.McBrien JL, Cheng R, Jones P. Virtual spaces: Employing a synchronous online classroom to facilitate student engagement in online learning. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2009;10(3):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mercer S. Language learner engagement: setting the scene. In: Gao X, editor. Second Handbook of English Language Teaching. Berlin: Springer; 2019. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mofareh A. The use of technology in English language teaching. Front. Educ. Technol. 2019;2(3):168–180. doi: 10.22158/fet.v2n3p168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mohamadi Z. Task engagement: a potential criterion for quality assessment of language learning tasks. Asian Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 2017;2(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mohamadi Z. Comparative effect of online summative and formative assessment on EFL student writing ability. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2018;59:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mohamadi Z. Comparative effect of project-based learning and electronic project-based learning on the development and sustained development of English idiom knowledge. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2018;30(2):363–385. doi: 10.1007/s12528-018-9169-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mohamadi Zenouzagh Z. Language-related episodes and feedback in synchronous voiced-based and asynchronous text-based computer-mediated communications. J. Comput. Educ. 2022;9:1–33. doi: 10.1007/s40692-021-00212-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mohammadi Zenouzagh Z. Student interaction patterns and co-regulation practices in text-based and multimodal computer mediated collaborative writing modalities. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11423-022-10158-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mohammadi Zenouzagh Z. Multidimensional analysis of efficacy of multimedia learning in development and sustained development of textuality in EFL writing performances. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2018;23(6):2969–2989. doi: 10.1007/s10639-018-9754-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Monkaresi H, Bosch N, Calvo RA, D'Mello SK. Automated detection of engagement using video-based estimation of facial expressions and heart rate. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2017;8(1):15–28. doi: 10.1109/TAFFC.2016.2515084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Montenegro A. Understanding the concept of agentic engagement. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. 2017;19:117–128. doi: 10.14483/calj.v19n1.10472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nguyen LT, Conduit J, Lu VN, Rao Hill S. Engagement in online communities: implications for consumer price perceptions. J. Strateg. Market. 2016;24(3–4):241–260. doi: 10.1080/0965254X.2015.1095224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nguyen, T.H.: EFL Vietnamese Learners’ Engagement with English Language During Oral Classroom Peer Interaction. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Wollongong (2017)

- 73.Nifriza I, Yenti D. Students' barriers in learning English through online learning. Linguist. Engl. Educ. Art LEEA J. 2021;5(1):39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Noels KA, Lascano DIV, Saumure K. The development of self-determination across the language course: trajectories of motivational change and the dynamic interplay of psychological needs, orientations, and engagement. Stud. Second Lang. Acquisit. 2019;41(4):821–851. doi: 10.1017/S0272263118000189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pekrun R. Emotions as drivers of learning and cognitive development. In: Calvo RA, D’Mello SK, editors. New Perspectives on Affect and Learning Technologies. Berlin: Springer; 2011. pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Philp J, Duchesne S. Exploring engagement in tasks in the language classroom. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2016;36:50–72. doi: 10.1017/S0267190515000094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reeve J, Jang H, Carrell D, Jeon S, Barch J. Enhancing students' engagement by increasing teachers' autonomy support. Motiv. Emot. 2004;28(2):147–169. doi: 10.1023/B:MOEM.0000032312.95499.6f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reschly AL, Christenson SL. Prediction of dropout among students with mild disabilities: a case for the inclusion of student engagement variables. Remed. Spec. Educ. 2006;27(5):276–292. doi: 10.1177/07419325060270050301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rudd DP, II, Rudd DP. The value of video in online instruction. J. Instr. Pedagog. 2014;13:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rumberger RW, et al. High school dropouts in the United States. In: Lamb S, Markussen E, Teese R, et al., editors. School Dropout and Completion. Berlin: Springer; 2011. pp. 275–294. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Salamonson Y, Andrew S, Everett B. Academic engagement and disengagement as predictors of performance in pathophysiology among nursing students. Contem. Nurse. 2009;32(1–2):123–132. doi: 10.5172/conu.32.1-2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sari FM. Exploring English learners’ engagement and their roles in the online language course. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. Linguist. 2020;5(3):349–361. doi: 10.21462/jeltl.v5i3.446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sari FM, Wahyudin AY. Undergraduate students' perceptions toward blended learning through instagram in English for business class. Int. J. Lang. Educ. 2019;3(1):64–73. doi: 10.26858/ijole.v1i1.7064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2004;25(3):293–315. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schaufeli WB, Martinez IM, Marques-Pinto AM, Salanova M, Bakker AB. Burnout and engagement in university students: a cross-national study. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2002;33:464–548. doi: 10.1177/0022022102033005003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sharifi M, Rostami AbuSaeedi A, Jafarigohar M, Zandi B. Retrospect and prospect of computer assisted English language learning: a meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2018;31(4):413–436. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2017.1412325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sharma S, Bumb A. The challenges faced in technology-driven classes during covid-19. Int. J. Distance Educ. Technol. (IJDET) 2021;19(1):66–88. doi: 10.4018/IJDET.20210101.oa2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shernoff DJ. Measuring student engagement in high school classrooms and what we have learned. In: Shernoff DJ, editor. Optimal Learning Environments to Promote Student Engagement. Berlin: Springer; 2013. pp. 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shernoff DJ, Csikszentmihalyi M, Schneider B, Shernoff ES. Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. In: Csikszentmihalyi M, editor. Applications of Flow in Human Development and Education. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 475–494. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sinatra GM, Heddy BC, Lombardi D. The challenges of defining and measuring student engagement in science. Educ. Psychol. 2015;50:1–13. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2014.1002924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Skinner EA, Belmont MJ. Motivation in the classroom: reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. J. Educ. Psychol. 1993;85(4):571. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Skinner EA, Pitzer JR. Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In: Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C, editors. Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Berlin: Springer; 2012. pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Soffer T, Cohen A. Students' engagement characteristics predict success and completion of online courses. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2019;35(3):378–389. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Svalberg AML. Engagement with language: Interrogating a construct. Lang. Aware. 2009;18(3–4):242–258. doi: 10.1080/09658410903197264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Svalberg AML. Researching language engagement; current trends and future directions. Lang. Aware. 2018;27(1–2):21–39. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2017.1406490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tinio, M.F.: Academic engagement scale for grade school students. In: The Assessment Handbook, vol. 2, pp. 64–75. PEMEA (2009)

- 97.Tseng WT, Dörnyei Z, Schmitt N. A new approach to assessing strategic learning: the case of self-regulation in vocabulary acquisition. Appl. Linguist. 2006;27(1):78–102. doi: 10.1093/applin/ami046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.van Uden JM, Ritzen H, Pieters JM. I think I can engage my students. Teachers' perceptions of student engagement and their beliefs about being a teacher. Teach. Teacher Educ. 2013;32:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2013.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang MT, Holcombe R. Adolescents’ perceptions of school environment, engagement, and academic achievement in middle school. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2010;47(3):633–662. doi: 10.3102/0002831209361209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang MT, Fredricks JA, Ye F, Hofkens TL, Linn JS. The math and science engagement scales: scale development, validation, and psychometric properties. Learn. Instr. 2016;43:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang Z, Bergin C, Bergin DA. Measuring engagement in fourth to twelfth grade classrooms: the classroom engagement inventory. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2014;29(4):517. doi: 10.1037/spq0000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wigfield A, Guthrie JT. Engagement and motivation in reading. In: Kamil M, Mosenthal P, Pearson P, Barr R, editors. Handbook of Reading Research. New York: Routledge; 2000. pp. 403–422. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yazzie-Mintz E, McCormick K. Finding the humanity in the data: understanding, measuring, and strengthening student engagement. In: Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C, editors. Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Berlin: Springer; 2012. pp. 743–761. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang Z. Learner engagement and language learning: a narrative inquiry of a successful language learner. Lang. Learn. J. 2020;50:1–15. [Google Scholar]