Highlights

-

•

In ovarian cancer, VEGFA and VASH1 were associated with angiogenic pathways, and the expression of VEGFA was positively correlated with that of VASH1.

-

•

The level of Tregs infiltration and the expression of its marker FOXP3 were positively correlated with the expression of VEGFA and VASH1.

-

•

High expression of VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 are all associated with poor prognosis in ovarian cancer.

-

•

Combined anti-angiogenic therapy and immunosuppressive therapy may become a new treatment direction for ovarian cancer in the future.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Angiogenesis, Immunotherapy, Immunosuppression, Tregs

Abstract

Vasohibin1 (VASH1) is a kind of vasopressor, produced by negative feedback from vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA). Anti-angiogenic therapy targeting VEGFA is currently the first-line treatment for advanced ovarian cancer (OC), but there are still many adverse effects. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are the main lymphocytes mediating immune escape function in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and have been reported to influence the function of VEGFA. However, whether Tregs are associated with VASH1 and angiogenesis in TME in OC is unclear. We aimed to explore the relationship between angiogenesis and immunosuppression in the TME of OC. We validated the relationship between VEGFA, VASH1, and angiogenesis in ovarian cancer and their prognostic implications. The infiltration level of Tregs and its marker forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) were explored in relation to angiogenesis-related molecules. The results showed that VEGFA and VASH1 were associated with clinicopathological stage, microvessel density and poor prognosis of ovarian cancer. Both VEGFA and VASH1 expression were associated with angiogenic pathways and there was a positive correlation between VEGFA and VASH1 expression. Tregs correlated with angiogenesis-related molecules and indicated that high FOXP3 expression is harmful to the prognosis. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) predicted that angiogenesis, IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, TGF-β signaling, and TNF-α signaling via NF-κB may be common pathways for VEGFA, VASH1, and Tregs to be involved in the development of OC. These findings suggest that Tregs may be involved in the regulation of tumor angiogenesis through VEGFA and VASH1, providing new ideas for synergistic anti-angiogenic therapy and immunotherapy in OC.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women and is particularly harmful to their health at the age of 40-80. American Cancer Society statistics predict that the number of new cases of OC in 2022 will be 19,880, and 12,810 patients will die [1]. Because of the late onset and non-specific nature of symptoms, most deaths are in patients with advanced, high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) [2], and only about 20% of patients survive to 5 years from diagnosis [3]. The high morbidity and mortality rates of OC are associated with late diagnosis of the disease and reduced effectiveness of surgical or pharmacological treatment [4]. Currently, the standard of care for advanced OC is tumor reduction surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy [5]. However, most patients responding well to these treatments eventually relapse and develop chemotherapy resistance [2]. This situation has prompted people to consider other alternative treatment modalities.

Tumor angiogenesis is a significant progress for tumorigenesis and development. It has become a hot topic of research in oncology in recent years, in which the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFA) plays an important role [6]. Judah Folkman first reported that neo-angiogenesis occurred in solid tumors and that inhibition of angiogenesis could be anti-tumor [7]. Vascular-targeting drugs block angiogenesis, inducing tumor hypoxia, and depriving tumors of the nutrients they need to grow, thereby slowing tumor growth. However, anti-VEGFA therapy leads to adverse events, including drug resistance, hypertension, and proteinuria. Moreover, the hypoxic environment caused by anti-VEGFA therapy inhibits the formation of immune function in the TME, which is detrimental to tumor elimination. Vasohibin1 (VASH1) is a new endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor with anti-angiogenic function [8]. A report identified that mice treated with the adenovirus VASH1 gene did not show any morphological changes in normal blood vessels [9], wound healing, body weight, or peripheral blood flow [10].

The TME consists of a complex network of multiple types of stromal cells, immune cells, and various cytokines, growth factors, and hormones that surround tumor cells and are nourished by the vascular system [11]. Among them, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and neovascularization are important for tumor progression. Tumor eradication requires effector T cells [12]. A sustained antitumor immune response requires both CD4+T cells and cytolytic CD8+T cells, but most OC patients have no high levels of effector T cells in their tumors [13]. Tregs and M2 macrophages limit the function of effector T cells in the TME of OC. These immunosuppressive cells can secrete cytokines to block the recruitment and proliferation of effector T cells [14]. Tregs specifically express CD4, CD25, and FOXP3, with FOXP3 playing a vital role in the development and suppressive function of Tregs. Some studies have confirmed that Tregs can promote tumor angiogenesis through direct or indirect actions. Tregs can promote angiogenesis by releasing TNFα, IFN-γ, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 when they suppress Th1 effector cells. Tregs can also directly secrete VEGFA to promote angiogenesis [15]. Recently, targeted Tregs therapies have received attention. Lim et al. showed that targeting SCAP/SREBP signaling in intra-tumor Tregs inhibited tumor growth and promoted immunotherapy by targeting the immune checkpoint protein PD-1 [16].

So, people want to find ways to simultaneously inhibit angiogenesis and immune escape in the TME and avoid drug toxicity as much as possible to treat OC. In this study, we used immunohistochemistry to explore the expression of the three proteins, VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3, combined with clinical data for survival analysis and determined the prognostic significance of these proteins in HGSOC tissues. Expression profiling data from public databases were used to explore the relationship between these genes and the link of VEGFA and VASH1, with Tregs infiltration in TME. Finally, the common signaling pathways among VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 were analyzed using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and protein interaction networks (PPI).

Materials and methods

Clinical data collection

This study screened 1069 samples diagnosed with OC in the Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, from January 2014 to January 2018. The patients were excluded if they had undergone neoadjuvant chemotherapy, were diagnosed with non-HGSOC, had secondary ovarian malignancies, or did not receive primary surgical treatment. Finally, 131 patients with complete clinical information, paraffin tissue, and follow-up results were finally available (Fig. S1). Follow-up results were obtained by telephone. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital, Shandong University (2021-281).

Immunohistochemistry

The expression levels of VEGFA, VASH1, FOXP3, and CD31 in HGSOC tissues were determined by immunohistochemistry. Paraffin sections of 4-μm thickness were cut, then dewaxed and hydrated. Hydrogen peroxide treatment blocked endogenous peroxidase activity, and goat serum blocked non-specific antigens (1:10). As shown in Table 1, the primary antibodies used in this study were summarized in detail. All primary antibodies were diluted using phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Next, these sections were treated with biotin-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG aggregates and streptavidin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. DAB substrate was used to detect the positive signals. All the above reagents except primary antibodies were purchased from Zhongshan Jin-Qiao Biotechnology Company. We invited two gynecological pathologists to blindly evaluated and scored the stained tissue specimens. Here are the rules of the staining intensity measurement: no staining = 0, yellowish staining = 1, yellow-brown staining = 2, and Brown staining = 3. The proportion of positively stained cells was scored: ≤5% = 0, 5-25% = 1, 26-50% = 2, 51-75% = 3, ≥76% = 4. The sum of the staining intensity grading and the percentage grading was defined as the staining score on a scale of 0 to 7. For statistical evaluation, the staining scores were classified as follows: 0-2 = low expression; 3-7 = high expression. CD31 positive cells represent vascular endothelial cells, and the lumen formed by positive endothelial cells was defined as a separate microvascular. The number of microvascular per unit area in five random fields of view was calculated and the mean value was used as the microvascular density (MVD).

Table 1.

Antibodies used for immunohistochemical staining.

| Antibody | Clone | Host species | Manufacturer | Dliution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGFA | ab1316 | Mouse mAb | Abcam, Cambridge, UK | 1:400 |

| VASH1 | #H00022846-M05 | Mouse mAb | Abnova, Taipei, Taiwan | 1:600 |

| FOXP3 | #12653 | Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology, USA | 1:800 |

| CD31 | ab28364 | Rabbit pAb | Abcam, Cambridge, UK | 1:100 |

Abbreviations: VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VASH1, vasohibin1; FOXP3, forkhead box protein 3; mAb, monoclonal antibody; pAb, polyclonal antibody

Analysis of the relationship of angiogenic markers, VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 expression in public databases

RNA-seq data were downloaded from the USCS Xena website for 33 cancers in the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database and 31 normal solid tissues in the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database. The expression correlations of angiogenic markers (i.e., CD34 and CD31)[17], VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 were analyzed in these cancer samples and normal tissue datasets, respectively.

Evaluation of the correlation of Tregs infiltration level with angiogenesis-related factors in public databases

The level of infiltration of 28 immune cell species in the TME of OC was quantified using the normalized enrichment score (NES). The NSE was derived based on the single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) function in the R package "GSVA". A set of 28 marker genes for TILs was obtained from Charoentong et al. [18]. RNA-seq data were obtained from the TCGA website for 380 patients. Gene expression datasets of 935 patients were obtained from three datasets, GSE9891, GSE32062, and GSE140082. The online TIMER 2.0 database is also used [19,20]. The relationship of Tregs infiltration level with the expression of CD34, CD31, VEGFA, and VASH1 was respectively analyzed.

Analysis of GSEA and PPI

We used the R package "clusterProfiler" function for GSEA to explore the relationship of VEGFA and VASH1 with angiogenesis pathway, and reveal the potential functions and common biological pathways of VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3. To realize these processes, the coefficient and P value of the correlation between the expression of a target gene and that of the other genes were individually calculated. GSEA was performed based on a list of genes generated by the correlation analysis. Fifty hallmark gene sets were obtained from the Broad Institute's MSigDB database. We ranked the GSEA enrichment score results for VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 from highest to lowest to identify the top 15 significantly enriched pathways, respectively. Finally, five common marker pathways were acquired. The online database STRING was used to construct PPI networks for VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3. The top 50 high-ranking relevant candidate proteins were identified using an interaction score > 0.5 as the threshold. We analyzed the interaction relationships between the candidate proteins and visualized the PPI network using Cytoscape 3.9.1 software. Using an insertional MCODE with a degree cutoff of 2, node score cutoff of 0.2, k-score of 2, max depth of 100, and a minimum number of genes of 4, we identified the central modules in the PPI network.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were assessed by chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Differences between continuous data were compared with the Mann-Whitney test. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Correlations among CD34, CD31, VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 were analyzed using Spearman correlation coefficients (r). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25, R software (version 4.1.3). Difference results were considered statistically significant when P-value < 0.05.

Results

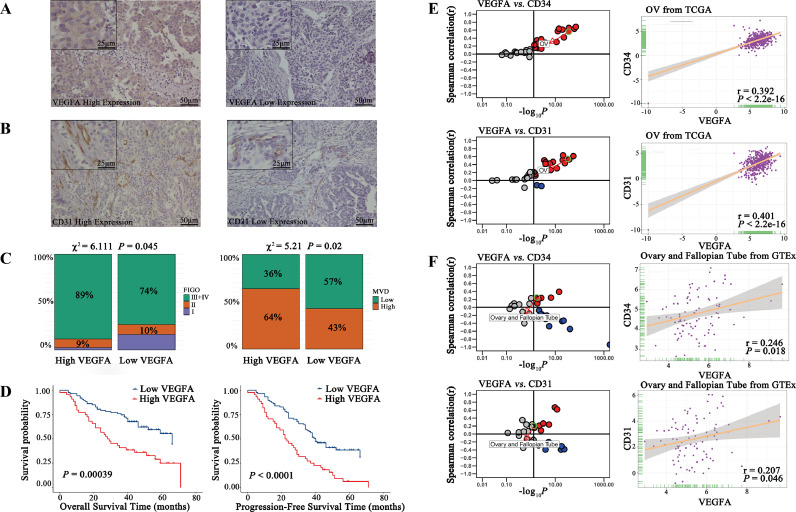

Correlation of VEGFA expression with clinicopathological parameters, micro angiogenesis, and prognosis

As shown in Fig. S1, a total of 131 patients were screened. Their clinicopathological characteristics are summarized in Table 2. We analyzed the relationship between the expression of VEGFA and clinicopathological parameters in Table 3. It was found that the expression VEGFA was localized in the cytoplasm of cancer cells (Fig. 1A) and CD31 was localized in the endothelial cytoplasm of blood vessels (Fig. 1B). VEGFA expression correlated with the FIGO stage (P=0.045) and MVD (P=0.022, Fig. 1C). Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig. 1D) showed that patients expressing high levels of VEGFA had worse OS (P=0.00039). Patients expressing high VEGFA had more rapid disease progression, meaning that these patients had worse PFS (P<0.0001). Then we analyzed the expression of angiogenic markers (i.e., CD34 and CD31), markers of endothelial cells, concerning VEGFA expression based on the TCGA database. Both CD34 (Fig. 1E, r=0.392, P<2.2e-16) and CD31 (r=0.401, P<2.2e-16) were positively correlated to the expression of VEGFA in OC tissues, which indicated the relationship between VEGFA and micro angiogenesis. In normal ovary-fallopian tube tissue, both CD34 (Fig. 1F, r=0.246, P=018) and CD31 (r=0.207, P=0.046) were also positively correlated to the expression of VEGFA.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the patients with HGSOC.

| Characteristics | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 55.4±10.3 |

| Age of menarche (years, mean ±SD) | 15.4±2.3 |

| CA125 (U/ml) | |

| ≤35 | 4(3.1) |

| >35 | 125(95.4) |

| Unknow | 2(1.5) |

| FIGO stage | |

| I | 15(11.5) |

| II | 13(9.9) |

| III+IV | 103(78.6) |

| Lymph Node Metastasis | |

| Negative | 106(80.9) |

| Positive | 25(19.1) |

| Lymph Vascular Space Invasion | |

| Negative | 94(71.8) |

| Positive | 37(28.2) |

| P53 | |

| Negative | 45(34.4) |

| Positive | 86(65.6) |

| Ki67 | |

| High | 59(45.1) |

| Low | 56(42.7) |

| Unknown | 16(12.2) |

| MVD | |

| High | 65(49.6) |

| Low | 66(50.4) |

| Family history of gynecologic cancer | |

| Yes | 9(6.9) |

| No | 122(93.1) |

| VEGFA | |

| High | 44(33.6) |

| Low | 87(66.4) |

| VASH1 | |

| High | 62(47.3) |

| Low | 69(52.7) |

| FOXP3 | |

| High | 18(13.7) |

| Low | 113(86.3) |

| Death | 66(50.4) |

| Progress | 27(20.6) |

Abbreviations: HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; CA125, Carbohydrate antigen 125;

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; P53, protein 53; MVD, microvascular density; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VASH1, vasohibin1; FOXP3, forkhead box protein 3.

Table 3.

Correlation of VEGFA with clinical parameters of patients with HGSOC.

| Characteristics | VEGFA (%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | ||

| N | 44(33.6) | 87(66.4) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| <55 | 19(43.2) | 50(57.5) | 0.122 |

| ≥55 | 25(56.8) | 37(42.5) | |

| Age of menarche (years) | |||

| <15 | 14(31.8) | 25(28.7) | 0.463 |

| ≥15 | 22(50.0) | 52(59.8) | |

| Unknown | 8(18.2) | 10(11.5) | |

| CA125 (U/ml) | |||

| ≤35 | 1(2.3) | 3(3.4) | 1.000 |

| >35 | 41(93.2) | 84(96.6) | |

| Unknow | 2(4.5) | - | |

| FIGO stage | |||

| I | 1(2.3) | 14(16.1) | 0.045* |

| II | 4(9.1) | 9(10.3) | |

| III+IV | 39(88.6) | 64(73.6) | |

| Lymph Node Metastasis | |||

| Negative | 34(77.3) | 72(82.8) | 0.450 |

| Positive | 10(22.7) | 15(17.2) | |

| Lymph Vascular Space Invasion | |||

| Negative | 31(70.5) | 63(72.4) | 0.814 |

| Positive | 13(29.5) | 24(27.6) | |

| P53 | |||

| Negative | 16(36.4) | 29(33.3) | 0.438 |

| Positive | 28(63.6) | 58(66.7) | |

| Ki67 | |||

| High | 19(43.2) | 40(46.0) | 0.966 |

| Low | 19(43.2) | 37(42.5) | |

| Unknown | 6(13.6) | 10(11.5) | |

| MVD | |||

| High | 28(63.6) | 37(42.5) | 0.022* |

| Low | 16(36.4) | 50(57.5) | |

| VASH1 | |||

| High | 31(70.5) | 31(35.6) | 0.000* |

| Low | 13(29.5) | 56(64.4) | |

| FOXP3 | |||

| High | 8(18.2) | 10(11.5) | 0.294 |

| Low | 36(81.8) | 77(88.5) | |

| Family history of gynecologic cancer | |||

| Yes | 3(6.8) | 6(6.9) | 1.000 |

| No | 41(93.2) | 81(93.1) | |

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant

Abbreviations: HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; CA125, Carbohydrate antigen 125;

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; P53, protein 53; MVD, microvascular density; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VASH1, vasohibin1; FOXP3, forkhead box protein 3.

Fig. 1.

Correlation of VEGFA expression with clinicopathological parameters, micro angiogenesis, and prognosis.

A. Images of HGSOC tissues with high and low protein expression of VEGFA based on immunohistochemical staining.

B. Images of HGSOC tissues with high and low protein expression of CD31 based on immunohistochemical staining.

D. FIGO stage and MVD were associated with high VEGFA expression levels in HGSOC tissues.

E. Kaplan–Meier curves of OS and PFS according to VEGFA expression in HGSOC tissues. High levels of VEGFA expression were associated with poorer OS and PFS compared with low levels of VEGFA expression.

E. Correlation of VEGFA with angiogenic markers (i.e., CD34 and CD31) in expression in cancer samples (every dot represents one cancer type) and ovarian cancer based on the TCGA database. CD34 and CD31 were strongly positively associated with VEGFA in ovarian cancer.

F. Correlation of VEGFA with angiogenic markers expression in normal tissues (every dot represents one tissue type) and ovary-fallopian tube tissues based on the GETx database. CD34 and CD31 had no association with VEGFA in ovary-fallopian tube tissues.

Abbreviations: HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; MVD, microvascular density; VASH1, vasohibin1; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression.

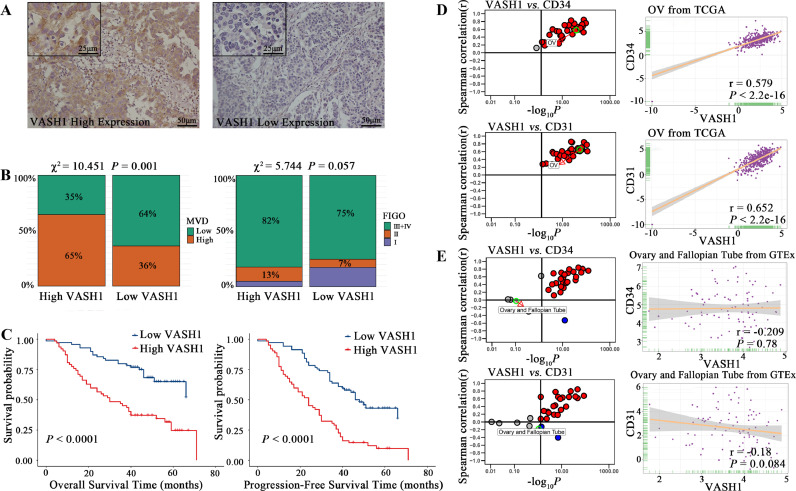

Correlation of VASH1 expression with clinicopathological parameters, micro angiogenesis, and prognosis

VASH1 expression was also localized in the cytoplasm of cancer cells (Fig. 2A). Then as shown in Table 4 and Fig. 2B, VASH1 expression correlated with MVD (P=0.001) and a marginal correlation with FIGO stage (P=0.057). Kaplan-Meier curves showed that patients expressing high levels of VASH1 had worse OS and had more rapid disease progression (Fig. 2C, P<0.0001). CD34 (Fig. 2D, r=0.579, P<2.2e-16) and CD31 (r=0.652, P<2.2e-16) were also positively correlated to the expression of VASH1 in OC tissues of the TCGA database and had no significant correlation in the GTEx database (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Correlation of VASH1 expression with clinicopathological parameters, micro angiogenesis, and prognosis.

A. Images of HGSOC tissues with high and low protein expression of VASH1 based on immunohistochemical staining.

B. MVD was strongly associated with high VASH1 expression levels in HGSOC tissues, and FIGO stage was marginally associated with high VASH1 expression levels.

C. Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS and OS according to VASH1 expression in HGSOC tissues. High levels of VASH1 expression were associated with poorer OS and PFS compared with low levels of VASH1 expression.

D. Correlation of VASH1 with angiogenic markers in expression in cancer samples (every dot represents one cancer type) and ovarian cancer samples based on the TCGA database. CD34 and CD31 were strongly positively associated with VASH1 in ovarian cancer.

E. Correlation of VASH1 with angiogenic markers expression in normal tissues (every dot represents one tissue type) and ovary-fallopian tube tissues based on the GETx database. CD34 and CD31 had no association with VASH1 in ovary-fallopian tube tissues.

Abbreviations: HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; MVD, microvascular density; VASH1, vasohibin1; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression.

Table 4.

Correlation of VASH1 with clinical parameters of patients with HGSOC.

| Characteristics | VASH1(%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | ||

| N | 62(47.3) | 69(52.7) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| <55 | 29(46.8) | 40(58.0) | 0.200 |

| ≥55 | 33(53.2) | 29(42.0) | |

| Age of menarche (years) | |||

| <15 | 21(33.9) | 18(26.1) | 0.539 |

| ≥15 | 34(54.8) | 40(58.0) | |

| Unknown | 7(11.3) | 11(15.9) | |

| FIGO stage | |||

| I | 3(4.8) | 12(17.4) | 0.057 |

| II | 8(12.9) | 5(7.2) | |

| III+IV | 51(82.3) | 52(75.4) | |

| Lymph Node Metastasis | |||

| Negative | 50(80.6) | 56(81.2) | 0.940 |

| Positive | 12(19.4) | 13(18.8) | |

| Lymph Vascular Space Invasion | |||

| Negative | 46(74.2) | 48(69.6) | 0.557 |

| Positive | 16(25.8) | 21(30.4) | |

| CA125 (U/ml) | |||

| ≤35 | 2(3.2) | 2(2.9) | 1.000 |

| >35 | 58(93.5) | 67(97.1) | |

| Unknow | 2(3.2) | - | |

| P53 | |||

| Negative | 18(29.0) | 27(39.1) | 0.224 |

| Positive | 44(71.0) | 42(60.9) | |

| Ki67 | |||

| High | 27(43.5) | 32(46.4) | 0.941 |

| Low | 27(43.5) | 29(42.0) | |

| Unknown | 8(12.9) | 8(11.6) | |

| MVD | |||

| High | 40(64.5) | 25(36.2) | 0.001* |

| Low | 22(35.5) | 44(63.8) | |

| VEGFA | |||

| High | 31(50.0) | 13(18.8) | 0.000* |

| Low | 31(50.0) | 56(81.2) | |

| FOXP3 | |||

| High | 11(17.7) | 7(10.1) | 0.207 |

| Low | 51(82.3) | 62(89.9) | |

| Family history of gynecologic cancer | |||

| Yes | 5(8.1) | 4(5.8) | 0.735 |

| No | 57(91.9) | 65(94.2) | |

P<0.05 was considered the statistically significant

Abbreviations: HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; CA125, Carbohydrate antigen 125;

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; P53, protein 53; MVD, microvascular density; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VASH1, vasohibin1; FOXP3, forkhead box protein 3.

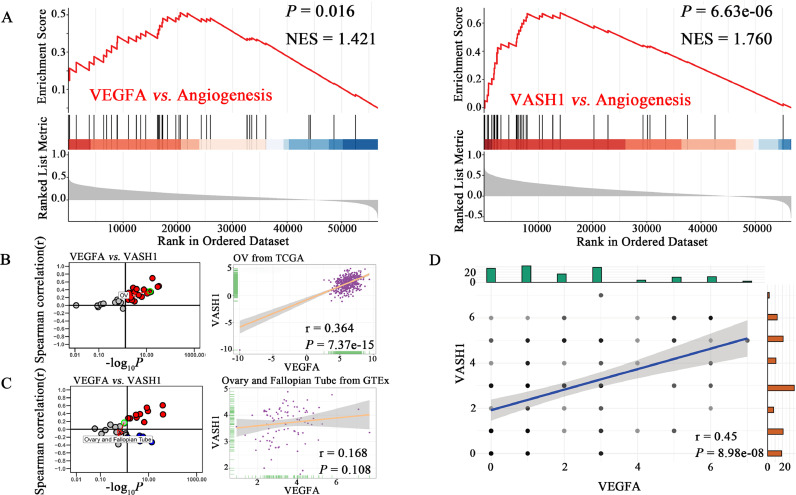

Correlation of VEGFA, VASH1, and angiogenesis pathway

The results of ssGSEA showed that VEGFA (P=0.016) and VASH1 (P=6.63e-06) could be significantly enriched in the angiogenesis pathway (Fig. 3A). Among the 33 cancer data, VEGFA and VASH1 were significantly positively correlated in 22 cancer samples, including OC tissues (Fig. 3B, r=0.364, P=7.37e-15). Among the 31 normal tissues data, they were positively correlated in 11 tissues. But in normal ovary-fallopian tube tissues, VEGFA and VASH1 had no significant correlation in the GTEx database (Fig. 3C, r=0.168, P=0.108). In HGSOC tissues, the expression of VEGFA and VASH1 were significantly correlated (Fig. 3D, r=0.45, P=8.98e-08).

Fig. 3.

Correlation of VEGFA, VASH1, and angiogenesis pathway.

A. VEGFA and VASH1 can be significantly enriched in the angiogenesis pathway.

B. Correlation of VEGFA with VASH1 in expression in cancer samples (every dot represents one cancer type) and ovarian cancer samples based on the TCGA database. VASH1 was strongly positively associated with VEGFA in ovarian cancer.

C. Correlation of VEGFA with VASH1 in expression in normal tissues (every dot represents one tissue type) and ovary-fallopian tube tissues based on the GETx database. VASH1 was positively associated with VEGFA in ovary-fallopian tube tissues.

D. Correlation of VEGFA with VASH1 in expression in HGSOC tissues. VASH1 was positively associated with VEGFA in HGSOC tissues.

Abbreviations: VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VASH1, vasohibin1; HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; NES, normalized enrichment score; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression.

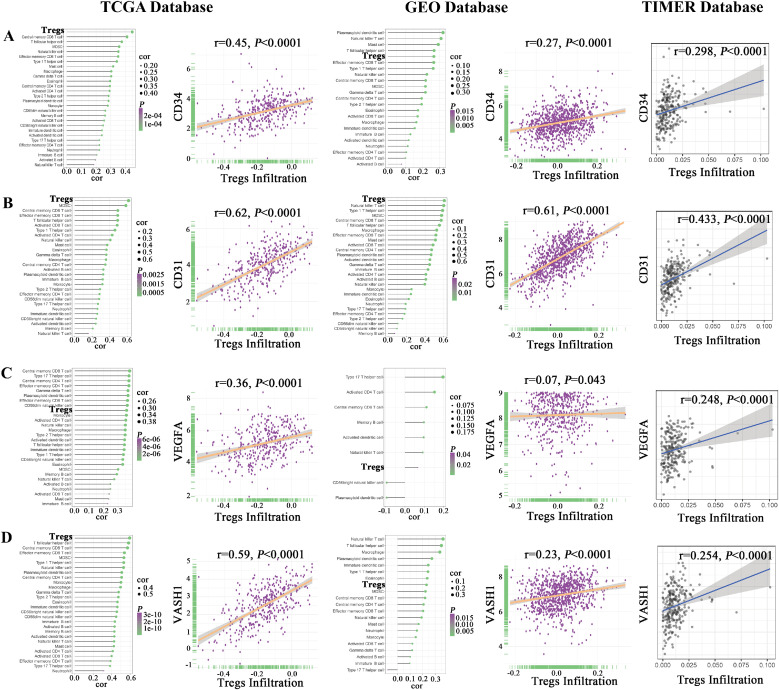

Correlation of Tregs infiltration level with angiogenesis-related factors in public databases

Our study and previous studies have shown that VEGFA and VASH1 are associated with the angiogenesis process, so we collectively refer to CD34, CD31, VEGFA, and VASH1 as angiogenesis-related factors. Using ssGSEA analysis, bubble plots showed the relationship between angiogenesis-related factors (i.e., CD34, CD31, VEGFA, and VASH1) and different types of immune cells in the TCGA and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) databases. Moreover, scatter plots showed that the expression of angiogenesis-related factors was positively correlated with Tregs infiltration based on the TCGA, the GEO, and the TIMER databases (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Correlation of Tregs infiltration level with angiogenesis-related factors in public databases. Angiogenesis-related factors were positively associated with Tregs infiltration levels.

A. Correlation of CD34 expression with the infiltration level of 28 types of immune cells and Tregs infiltration level in the TME of ovarian cancer based on the TCGA, the GEO, and the TIMER databases.

B. Correlation of CD31 expression with the infiltration level of 28 types of immune cells and Tregs infiltration level in the TME of ovarian cancer based on the TCGA, the GEO, and the TIMER databases.

C. Correlation of VEGFA expression with the infiltration level of 28 types of immune cells and Tregs infiltration level in the TME of ovarian cancer based on the TCGA, the GEO, and the TIMER databases.

D. Correlation of VASH1 expression with the infiltration level of 28 types of immune cells and Tregs infiltration level in the TME of ovarian cancer based on the TCGA, the GEO, and the TIMER databases.

Abbreviations: VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VASH1, vasohibin1; TME, tumor microenvironment; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus.

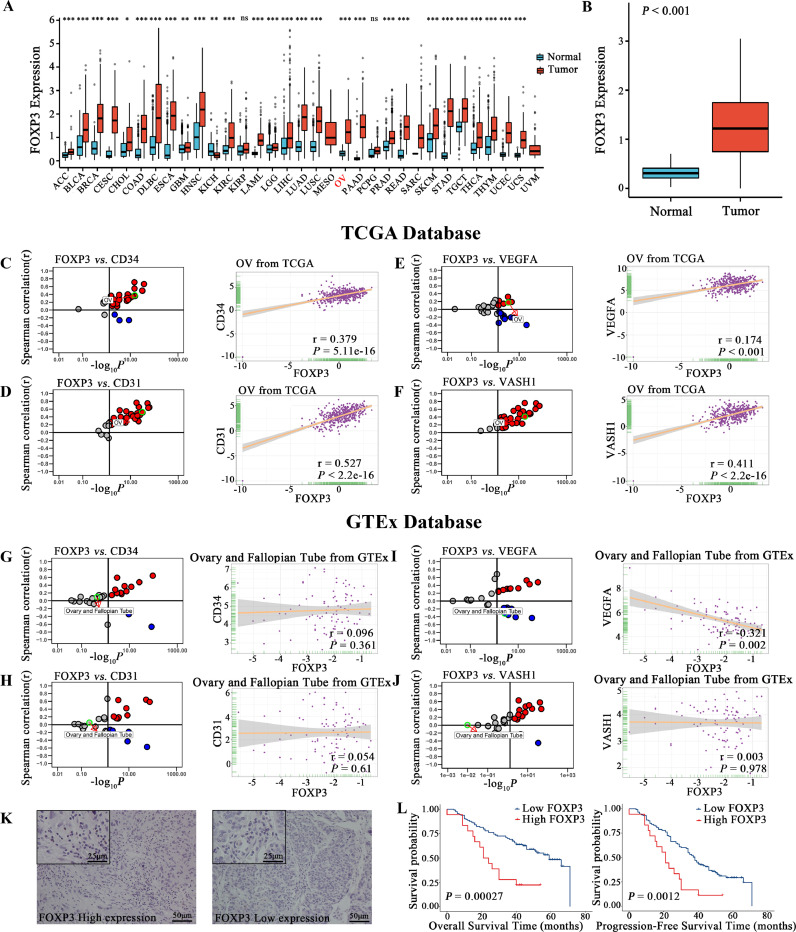

Correlation of FOXP3 expression with angiogenesis-related factors and prognosis

The difference in FOXP3 expression between tumor and normal tissues in various organs was analyzed from the TCGA and GTEx databases (Fig. 5A). The expression of FOXP3 was significantly higher in OC compared to normal tissues (Fig. 5B, P<0.001). In the TCGA database, the expression of angiogenesis-related factors, CD34, CD31, VEGFA, and VASH1, were strongly positively associated with FOXP3 in OC (Fig. 5C–F). Inversely, these had no positive association with FOXP3 in normal ovary-fallopian tube tissues in the GTEx database (Fig. 5G–J). FOXP3 expression was localized in the nucleus of lymphocytes, and the images of high and low expression were shown (Fig. 5K). Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig. 5L) showed that patients expressing high levels of FOXP3 had worse OS (P=0.00027) and had more rapid disease progression (P=0.0012). Univariate analysis for OS showed that FIGO stage, expression of VEGFA, VASH1 and FOXP3 were associated with OS. Multivariate analysis showed that VASH1 and FOXP3 were independent poor prognostic factors for ovarian cancer (Table 5). Univariate analysis for PFS showed that FIGO stage, expression of VEGFA, VASH1 and FOXP3 were associated with PFS. Multivariate analysis showed that FIGO stage, VASH1 and FOXP3 were independent poor prognostic factors for ovarian cancer (Table 6).

Fig. 5.

Correlation of FOXP3 expression with angiogenesis-related factors and prognosis

A. The difference in FOXP3 expression between tumor and normal tissues in the TCGA and GTEx database.

B. The difference in FOXP3 expression between ovarian tumor and normal tissues.

C. Expression correlation of FOXP3 with CD34 in cancer samples (every dot represents one cancer type) and in ovarian cancer samples based on the TCGA database.

D. Expression correlation of FOXP3 with CD31 in cancer samples and in ovarian cancer samples based on the TCGA database.

E. Expression correlation of FOXP3 with VEGFA in cancer samples and in ovarian cancer samples based on the TCGA database.

F. Expression correlation of FOXP3 with VASH1 in cancer samples and in ovarian cancer samples based on the TCGA database.

G. Expression correlation of FOXP3 with CD34 in normal tissues (every dot represents one tissue type) and in ovary-fallopian tube tissues based on the GTEx database.

H. Expression correlation of FOXP3 with CD31 in normal tissues and in ovary-fallopian tube tissues based on the GTEx database.

I. Expression correlation of FOXP3 with VEGFA in normal tissues and in ovary-fallopian tube tissues based on the GTEx database.

J. Expression correlation of FOXP3 with VASH1 in normal tissues and in ovary-fallopian tube tissues based on the GTEx database.

K. Images of HGSOC tissues with high and low protein expression of FOXP3 based on immunohistochemical staining.

L. Kaplan–Meier curves of OS and PFS according to FOXP3 expression in HGSOC tissues. High levels of FOXP3 expression were associated with poorer OS and PFS compared with low levels of FOXP3 expression.

Abbreviations: VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VASH1, vasohibin1; FOXP3, forkhead box protein 3; HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression.

Table 5.

Cox regression analysis for Overall Survival in 131 patients with HGSOC.

| Characteristics | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P-Value | HR | 95%CI | P-Value | |

| Age | ||||||

| <55 | 1.31 | 0.80-2.12 | 0.283 | |||

| ≥55 | ||||||

| FIGO stage | ||||||

| I | 1.54 | 1.07-2.23 | 0.022* | 1.38 | 0.92-2.07 | 0.120 |

| II | ||||||

| III | ||||||

| IV | ||||||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| Negative | 1.23 | 0.68-2.24 | 0.488 | |||

| Positive | ||||||

| Lymph Vascular Space Invasion | ||||||

| Negative | 1.10 | 0.65-1.89 | 0.717 | |||

| Positive | ||||||

| P53 | ||||||

| Negative | 1.13 | 0.67-1.91 | 0.643 | |||

| Positive | ||||||

| VEGFA | ||||||

| High | 2.42 | 1.49-3.92 | 0.000* | 1.56 | 0.92-2.63 | 0.097 |

| Low | ||||||

| VASH1 | ||||||

| High | 3.16 | 1.89-5.28 | 0.000* | 2.45 | 1.42-4.23 | 0.001* |

| Low | ||||||

| FOXP3 | ||||||

| Positive | 2.95 | 1.61-5.42 | 0.000* | 2.48 | 1.34-4.60 | 0.004* |

| Negative | ||||||

| MVD | ||||||

| High | 0.98 | 0.95-1.01 | 0.118 | |||

| Low | ||||||

| Family history of gynecologic cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 0.80 | 0.29-2.20 | 0.666 | |||

| No | ||||||

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant

Abbreviations: HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; HR, Hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; VASH1, vasohibin1; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; FOXP3, forkhead box P3; MVD, microvascular density; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Table 6.

Cox regression analysis for Progression-Free-Survival in 131 patients with HGSOC.

| Characteristics | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P-Value | HR | 95%CI | P-Value | |

| Age | ||||||

| <55 | 0.81 | 0.53-1.22 | 0.311 | |||

| ≥55 | ||||||

| FIGO stage | ||||||

| I | 1.81 | 1.31-2.50 | 0.000* | 1.81 | 1.27-2.59 | 0.001* |

| II | ||||||

| III | ||||||

| IV | ||||||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| Negative | 1.44 | 0.88-2.35 | 0.144 | |||

| Positive | ||||||

| Lymph Vascular Space Invasion | ||||||

| Negative | 1.35 | 0.87-2.09 | 0.175 | |||

| Positive | ||||||

| P53 | ||||||

| Negative | 0.48 | 0.94-2.32 | 0.089 | |||

| Positive | ||||||

| VEGFA | ||||||

| High | 2.46 | 1.63-3.72 | 0.000* | 1.54 | 0.99-2.40 | 0.055 |

| Low | ||||||

| VASH1 | ||||||

| High | 3.03 | 1.99-4.62 | 0.000* | 2.55 | 1.62-4.02 | 0.000* |

| Low | ||||||

| FOXP3 | ||||||

| Positive | 2.41 | 1.39-4.17 | 0.002* | 2.16 | 1.23-3.81 | 0.008* |

| Negative | ||||||

| MVD | ||||||

| High | 0.99 | 0.97-1.01 | 0.311 | |||

| Low | ||||||

| Family history of gynecologic cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.46-2.17 | 0.994 | |||

| No | ||||||

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant

Abbreviations: HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; HR, Hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; VASH1, vasohibin1; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; FOXP3, forkhead box P3; MVD, microvascular density; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

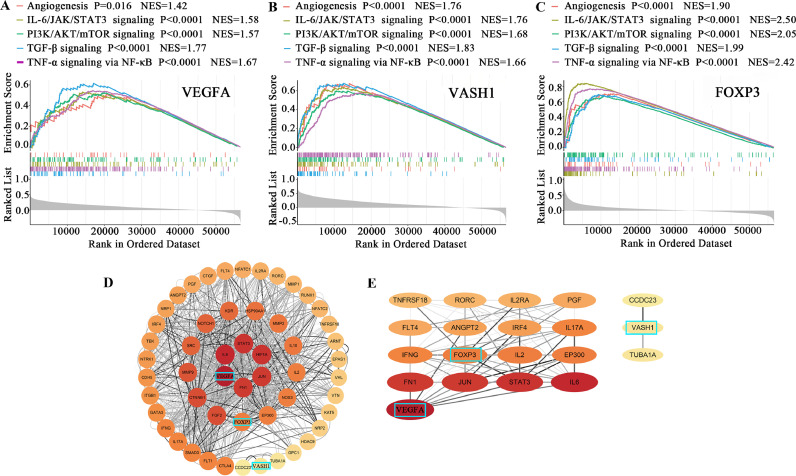

The common pathways of VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 in influencing the development of ovarian cancer

Based on the GSEA enrichment scores of VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3, the top 15 enrichment results were identified and intersected to obtain five common enrichment pathways, namely angiogenesis, IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, TGF-β signaling, and TNF-α signaling via NF-κB (Table 7, Fig. 6A–C). The PPI network has 53 nodes and 998 edges (Fig. 6D). The nodes are sorted according to their degree, and the importance is reflected by the size of the circle and the color shade. The two most essential modules identified by MCODE, as shown in Fig. 6E, showed that VEGFA and FOXP3 were associated with factors such as STAT3, IL6, and IFNG, while VASH1 was associated with microtubule activity.

Table 7.

GSEA of the genes most related to the expression of VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3.

| VEGFA | ES | P-Value | VASH1 | ES | P-Value | FOXP3 | ES | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallmark Gene Sets Top 15 | TGF_BETA_SIGNALING | 0.615 | 0.000* | HEDGEHOG_SIGNALING | 0.681 | 0.000* | INTERFERON_GAMMA_RESPONSE | 0.875 | 0.000* |

| MITOTIC_SPINDLE | 0.604 | 0.000* | TGF_BETA_SIGNALING | 0.676 | 0.000* | INTERFERON_ALPHA_RESPONSE | 0.874 | 0.000* | |

| PROTEIN_SECRETION | 0.577 | 0.000* | ANGIOGENESIS | 0.673 | 0.000* | ALLOGRAFT_REJECTION | 0.842 | 0.000* | |

| HYPOXIA | 0.565 | 0.000* | UV_RESPONSE_DN | 0.660 | 0.000* | IL6_JAK_STAT3_SIGNALING | 0.841 | 0.000* | |

| UNFOLDED_PROTEIN_RESPONSE | 0.550 | 0.000* | WNT_BETA_CATENIN_SIGNALING | 0.659 | 0.000* | INFLAMMATORY_RESPONSE | 0.824 | 0.000* | |

| UV_RESPONSE_DN | 0.549 | 0.000* | EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION | 0.655 | 0.000* | TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB | 0.769 | 0.000* | |

| TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB | 0.544 | 0.000* | MITOTIC_SPINDLE | 0.653 | 0.000* | COMPLEMENT | 0.769 | 0.000* | |

| G2M_CHECKPOINT | 0.543 | 0.000* | IL6_JAK_STAT3_SIGNALING | 0.632 | 0.000* | IL2_STAT5_SIGNALING | 0.752 | 0.000* | |

| HEDGEHOG_SIGNALING | 0.533 | 0.008* | APICAL_JUNCTION | 0.625 | 0.000* | EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION | 0.747 | 0.000* | |

| IL6_JAK_STAT3_SIGNALING | 0.532 | 0.000* | INFLAMMATORY_RESPONSE | 0.616 | 0.000* | APOPTOSIS | 0.723 | 0.000* | |

| HEME_METABOLISM | 0.530 | 0.000* | PROTEIN_SECRETION | 0.605 | 0.000* | KRAS_SIGNALING_UP | 0.712 | 0.000* | |

| PI3K_AKT_MTOR_SIGNALING | 0.524 | 0.000* | NOTCH_SIGNALING | 0.601 | 0.002* | ANGIOGENESIS | 0.704 | 0.000* | |

| ANGIOGENESIS | 0.511 | 0.016* | PI3K_AKT_MTOR_SIGNALING | 0.597 | 0.000* | APICAL_SURFACE | 0.695 | 0.000* | |

| APICAL_JUNCTION | 0.502 | 0.000* | IL2_STAT5_SIGNALING | 0.581 | 0.000* | TGF_BETA_SIGNALING | 0.693 | 0.000* | |

| WNT_BETA_CATENIN_SIGNALING | 0.496 | 0.000* | TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB | 0.577 | 0.000* | PI3K_AKT_MTOR_SIGNALING | 0.677 | 0.000* |

Note: P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Bolded text for co-enriched pathways. Abbreviations: GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; ES, Enrichment Score; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VASH1, vasohibin1; FOXP3, forkhead box protein 3.

Fig. 6.

Exploring the mechanisms of VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 in influencing ovarian cancer development.

A. Significant enrichment of high VEGFA expression and five common enrichment pathways (angiogenesis, IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, TGF-β signaling, and TNF-α signaling via NF-κB).

B. Significant enrichment of high VASH1 expression and five common enrichment pathways.

C. Significant enrichment of high FOXP3 expression and five common enrichment pathways

D. The PPI network was constructed by Cytoscape software among the associated genes from VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 based on the STRING database.

E. The two most important modules identified by MCODE of Cytoscape software based on the PPI network from VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3.

Abbreviations: VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VASH1, vasohibin1; FOXP3, forkhead box protein 3; NES, normalized enrichment score; PPI, protein interaction networks.

Discussion

Recent cancer research has shifted from focusing only on tumor cells to the TME. The TME includes various types of immune cells, stromal cells, and various chemokines and cytokines. They collaborate to create a tumor-promoting environment with chronic inflammation and immunosuppression [21]. According to a growing body of evidence, angiogenesis and immunity seem to be linked in the TME, and targeting angiogenesis may play a key role in enhancing cancer immunotherapy [22,23]. In this study, we combined angiogenesis-related factors, VEGFA, VASH1, CD34, and CD34, with Tregs to investigate the possible relationship between angiogenesis and immunosuppression in the TME and their impact on the prognosis of OC.

Clinical results showed that high expression of VEGFA and VASH1 were associated with increased MVD and poor prognosis, and the expression of VEGFA and VASH1 were positively correlated. The positive correlation between VEGFA, VASH1, and angiogenesis was further verified using public databases. VEGFA and VASH1 are important molecules that regulate angiogenesis in the TME. It is widely known that VEGFA is a well-known inducer of angiogenesis, which promotes endothelial cell survival, vascular permeability, cell proliferation and migration, and neointima formation [24]. VEGFA is highly expressed in ovarian, colon, lung, gastric, and liver cancer tissues and is associated with poor tumor prognosis [25]. VASH1 is a vasopressor induced by selective negative feedback from VEGFA [8,26,27]. VASH1 is involved in a variety of pathological processes, including atherosclerosis [28], age-dependent macular degeneration (AMD)[27], diabetic retinopathy [29], as well as cancer [30]. In vitro and in vivo experiments have confirmed that VASH1 inhibits the induction of vascular neovascularization by VEGFA [31]. However, it was found that VASH1 was highly expressed in the cytoplasm and vascular endothelium of breast cancer [32], renal cell carcinoma, cervical squamous cell carcinoma [33], hepatocellular carcinoma [34], lung adenocarcinoma [35], colorectal cancer [36], and ductal adenocarcinoma [37]. This gene was closely associated with tumor recurrence and metastasis, although some studies have also shown contrary findings. The same results were obtained in our study. This implies that VASH1 expression may be associated with infiltrative tumor growth as a response of tumor tissue to angiogenic stimuli. Meanwhile, VASH1 has recently been found to form a complex with SVBP that de-tyrosines microtubule proteins. The de-tyrosine microtubules are more stable in mitosis, associated with increased tumor aggressiveness. The amount of de-tyrosine microtubule protein is increased in patients with metastatic breast cancer than in early-stage breast cancer [38,39]. This also suggests a possible mechanism by which high VASH1 expression is associated with poor clinical outcomes. It was found that the VASH1 protein consists of 365 amino acids and has a predicted molecular weight of 44 kDa. VASH1 is degraded by tumor cell-produced protein hydrolases into a 36-kDa protein and a 29-kDa protein, with the 36-kDa protein retaining its anti-angiogenic activity and the 29-kDa protein losing its anti-angiogenic activity by cleavage at the N and C termini [40]. Due to this degradation and inactivation, the anti-angiogenic effect of VASH1 may be insufficient in the TME.

Tregs are potent immunosuppressive cells within the TME and are thought to be the primary mechanism for evading immune surveillance and promoting tumor progression [41,42]. Studies have shown that tumor-derived Tregs have relatively more potent inhibitory activity than naturally occurring Tregs. Tumor cells, under hypoxic conditions, can secrete various chemokines that attract Tregs to the tumor site [15]. Increased levels of Tregs infiltration are associated with poor prognosis in many tumors, including ovarian cancer [25]. In previous studies, Tregs and VEGFA were shown to have a reciprocal regulatory relationship. In TME, VEGFA inhibits dendritic cell differentiation, leading to immature or partially differentiated dendritic cells, which in turn induces Tregs formation and promotes Tregs proliferation and differentiation through the release of TGF-β [43]. Tregs promote tumor growth, exacerbating tissue hypoxia, which affects the vascular endothelium and leads to changes in the TME. Hypoxia induces the expression of CCL28, which further encourages tumor tolerance and angiogenesis by recruiting Treg cells. There was a significant increase in both VEGFA and Tregs levels in the blood of patients with metastatic colon cancer compared to healthy individuals. Tregs were significantly reduced after treatment with bevacizumab [44]. Therefore, we further analyzed the relationship between the infiltration level of Tregs and angiogenesis in the TME. The results showed that the expression of VEGFA, VASH1, and angiogenic markers, CD34 and CD31, were significantly correlated with the infiltration level of Tregs. VASH1 may be involved in the regulation of angiogenesis by Tregs.

Almost all Tregs express FOXP3. FOXP3 is an X chromosome-related factor that is essential for the suppressive function of Tregs. Immunosuppressive properties of FOXP3+Treg cells depend on FOXP3 expression level. It has been shown that transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) can promote the development of Tregs by initiating and maintaining FOXP3 expression [45]. The chemokine receptor CCR4 expressed by tumor-infiltrating Tregs is also transcriptionally activated by FOXP3 to facilitate the recruitment of Tregs [46]. Therefore, we proceeded to analyze the relationship between FOXP3 and angiogenesis-related molecules. The results showed that FOXP3 was positively correlated with the expression of VEGFA, VASH1, CD34, and CD31. Our clinical data also showed that patients with high FOXP3 expression had a worse prognosis. No studies specifically elaborate on the relationship between Tregs infiltration and VASH1 expression. However, based on our findings suggesting a possible common action pathway or a reciprocal regulatory relationship between Tregs and VASH1, we speculate that this mechanism may be linked through VEGFA.

We performed GSEA to explore the possible common mechanism of action of VEGFA, VASH1, and Tregs. The enrichment results showed that VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 were co-enriched in five gene pathways of angiogenesis, IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, TGF-β signaling, and TNF-α signaling via NF-κB. While confirming that VASH1, VEGFA, and FOXP3 may all be involved in the microangiogenesis process, it was hypothesized that they jointly participate in the above pathological processes in the tumor microenvironment to promote tumor development and may have an interactive relationship. Further, we used the PPI network to construct VASH1, VEGFA, and FOXP3-related gene networks. VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 are associated with various oncogenes and inflammatory factors such as STAT3, HIF1A, and IL6. They were clustered, and the two most consequential networks were selected for display. VASH1 was closely associated with microtubule-related molecules CCDC23 and TUBA1A, which also suggested that VASH1 not only plays an anti-angiogenic role in tumor development but may play an important role in the process of microtubule-related activities as a way to promote tumor development.

Currently, many efforts are made to explore targets that can inhibit tumor angiogenesis and immune escape. Anti-angiogenesis can enhance the effect of immunotherapy. However, problems with resistance to anti-VEGFA therapy have prompted researchers to target ovarian cancer with VASH1, which exhibits broad-spectrum anti-angiogenic activity, including anti-FGF2 and PDGF activity [44]. The VASH1-SVBP complex has also been shown to have tubulin carboxypeptidase activity, which regulates microtubule activity and promotes tumor progression. All these studies suggest that VASH1 may be a promising anti-tumor targeting factor in the future. Combined targeting of VASH1 and Tregs may exhibit better efficacy. This study analyzed a large amount of data using immunohistochemistry and bioinformatics, but there are still things that could be improved. Our clinical sample size was small, and only public databases of RNA-seq and microarray data were used for correlation analysis. Further expansion of sample size and in vivo and in vitro experiments are needed for validation and correlation mechanism exploration.

Conclusion

The combination of immunotherapy with anti-angiogenic agents has now achieved significantly better efficacy than monotherapy in certain tumors. This study demonstrates the prognostic significance of VEGFA, VASH1, and FOXP3 in HGSOC patients. Our study confirmed the correlation between angiogenesis and immunosuppressive cell infiltration in TME. This evidence could provide a new idea for combining anti-angiogenesis and immunotherapy in ovarian cancer.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital, Shandong University (2021-281).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sijing Qiao: Data curation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Yue Hou: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation. Qing Rong: Writing – original draft, Validation. Bing Han: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Peishu Liu: Project administration, Writing – original draft, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The work described in this article has not been previously published.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Youth Fund from Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no. ZR2020QH252 and ZR2020QH045), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no. ZR2020MH272), the China Postdoctoral Science Fund (21510077311145 and 21300076311047), and Scientific and Technical Innovation Plan in clinical medicine of Jinan (grant no.202019005). Big data, science and technology program from jinan Health Commission (grant no. 2022-YBD-03). Shandong Medical Association Clinical Research Fund -- Qilu Special Project (grant no. YXH2022ZX02168).

Acknowledgments

I received a great deal of support and assistance throughout this dissertation. I would first like to thank my supervisors, Peishu Liu and Bing Han, whose expertise was invaluable in formulating my research questions and methodology. Her insightful feedback encouraged me to sharpen my thinking skills and brought my work to a higher level. I would like to acknowledge my team members, for their wonderful collaboration and support. Finally, I am indebted to my parents for their support and encouragement.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101665.

Contributor Information

Bing Han, Email: hanbing1030@126.com.

Peishu Liu, Email: peishuliu@126.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Fuchs H.E., Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022 doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berek J.S., Kehoe S.T., Kumar L., Friedlander M. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2018;143(2):59–78. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12614. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiavone M.B., et al. Natural history and outcome of mucinous carcinoma of the ovary. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;205:480.e481–480.e488. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu J.W., Charkhchi P., Akbari M.R. Potential clinical utility of liquid biopsies in ovarian cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21:114. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01588-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baden L.R., et al. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections, version 2.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:882–913. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zetter B.R. The scientific contributions of M. Judah Folkman to cancer research. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:647–654. doi: 10.1038/nrc2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl. J. Med. 1971;285:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe K., et al. Vasohibin as an endothelium-derived negative feedback regulator of angiogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:898–907. doi: 10.1172/JCI21152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heishi T., et al. Endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor vasohibin1 exhibits broad-spectrum antilymphangiogenic activity and suppresses lymph node metastasis. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;176:1950–1958. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li D., Zhou K., Wang S., Shi Z., Yang Z. Recombinant adenovirus encoding vasohibin prevents tumor angiogenesis and inhibits tumor growth. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:448–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao Y., Yu D. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021;221 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Disis M.L. Immune regulation of cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:4531–4538. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gokuldass A., et al. Qualitative analysis of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes across human tumor types reveals a higher proportion of bystander CD8 T cells in non-melanoma cancers compared to melanoma. Cancers. 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/cancers12113344. (Basel) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batchu R.B., et al. IL-10 signaling in the tumor microenvironment of ovarian cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021;1290:51–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-55617-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facciabene A., et al. Tumour hypoxia promotes tolerance and angiogenesis via CCL28 and T(reg) cells. Nature. 2011;475:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature10169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim S.A., et al. Lipid signalling enforces functional specialization of T cells in tumours. Nature. 2021;591:306–311. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03235-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rakocevic J., et al. Endothelial cell markers from clinician's perspective. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2017;102:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charoentong P., et al. Pan-cancer immunogenomic analyses reveal genotype-immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint blockade. Cell Rep. 2017;18:248–262. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li T., et al. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:W509–W514. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li B., et al. Comprehensive analyses of tumor immunity: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Genome Biol. 2016;17:174. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao R., et al. Characterization of hypoxia response patterns identified prognosis and immunotherapy response in bladder cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolyt. 2021;22:277–293. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2021.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivera L.B., Bergers G. Intertwined regulation of angiogenesis and immunity by myeloid cells. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trenti A., et al. Estrogen, angiogenesis, immunity and cell metabolism: solving the puzzle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19 doi: 10.3390/ijms19030859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrara N., Adamis A.P. Ten years of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2016;15:385–403. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curiel T.J., et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat. Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerbel R.S. Vasohibin: the feedback on a new inhibitor of angiogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:884–886. doi: 10.1172/JCI23153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato Y. The vasohibin family: a novel family for angiogenesis regulation. J. Biochem. 2013;153 doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamashita H., et al. Vasohibin prevents arterial neointimal formation through angiogenesis inhibition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;345:919–925. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakusawa R., et al. Expression of vasohibin, an antiangiogenic factor, in human choroidal neovascular membranes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2008;146:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Du H., et al. The roles of vasohibin and its family members: beyond angiogenesis modulators. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2017;18:827–832. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2017.1373217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voron T., et al. VEGF-a modulates expression of inhibitory checkpoints on CD8+ T cells in tumors. J. Exp. Med. 2015;212:139–148. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamaki K., et al. Vasohibin-1 in human breast carcinoma: a potential negative feedback regulator of angiogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.01015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao L., Sun P.-L., He Y., Yao M., Gao H. Desmoplastic reaction and tumor budding in cervical squamous cell carcinoma are prognostic factors for distant metastasis: a retrospective study. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020;12:137–144. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S231356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Q., Tian X., Zhang C., Wang Q. Upregulation of vasohibin-1 expression with angiogenesis and poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative surgery. Med. Oncol. 2012;29:2727–2736. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu M., et al. Association between TAp73, p53 and VASH1 expression in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2018;15:5175–5180. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.7912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu S., et al. Vasohibin-1 suppresses colon cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:7880–7898. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakagawa S., et al. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) regulates tumor angiogenesis and predicts recurrence and prognosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2018;20:939–948. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aillaud C., et al. Vasohibins/SVBP are tubulin carboxypeptidases (TCPs) that regulate neuron differentiation. Science. 2017;358:1448–1453. doi: 10.1126/science.aao4165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nieuwenhuis J., et al. Vasohibins encode tubulin detyrosinating activity. Science. 2017;358:1453–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.aao5676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saito M., Suzuki Y., Yano S., Miyazaki T., Sato Y. Proteolytic inactivation of anti-angiogenic vasohibin-1 by cancer cells. J. Biochem. 2016;160:227–232. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvw030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobs J.F.M., Nierkens S., Figdor C.G., de Vries I.J.M., Adema G.J. Regulatory T cells in melanoma: the final hurdle towards effective immunotherapy? Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e32–e42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Camisaschi C., et al. Immune landscape and in vivo immunogenicity of NY-ESO-1 tumor antigen in advanced neuroblastoma patients. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:983. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4910-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terme M., et al. VEGFA-VEGFR pathway blockade inhibits tumor-induced regulatory T-cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:539–549. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahashi Y., et al. The angiogenesis regulator vasohibin-1 inhibits ovarian cancer growth and peritoneal dissemination and prolongs host survival. Int. J. Oncol. 2015;47:2057–2063. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshimura A., Muto G. TGF-β function in immune suppression. Curr. Top Microb. Immunol. 2011;350:127–147. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lan H.-R., et al. Role of immune regulatory cells in breast cancer: foe or friend? Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021;96 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.