ABSTRACT

Absolute bioavailability (F) and the impact of gastric pH, tablet formulation, and food on the pharmacokinetics and safety of asundexian, an oral factor XIa inhibitor, was assessed in healthy White men aged 18–45 years in 4 studies. For F, fasted participants received 50 μg of [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian intravenously 2 hours after 25 mg of asundexian orally. Tablet formulation (50‐mg immediate release [IR], and different amorphous solid dispersion [ASD] IR 25‐mg and 50‐mg ASD IR tablets) and food effects were explored in 2 studies. Formulation was compared using 50‐mg IR versus 25‐mg ASD IR and 25‐mg ASD IR versus 50‐mg ASD IR (fasted); food effect using 25‐mg ASD IR and 50‐mg ASD IR. Gastric pH modulation was assessed using omeprazole or antacid coadministration with asundexian in the fasted state. Pharmacokinetic parameters included area under the concentration‐time curve (AUC; and AUC/dose [D]) and maximum observed concentration (Cmax and Cmax/D) data were evaluable for 59 participants. F was 103.9%. Relative bioavailability with 25‐mg ASD IR and 50‐mg ASD IR tablets, respectively, was marginally affected by formulation (AUC/D ratios, 94.3% and 95.1%; Cmax/D ratios, 95.5% and 88.7%), food (AUC[/D] ratios, 91.1% and 96.9%; Cmax[/D] ratios: 78.3% and 95.1%), and gastric pH (omeprazole, no effect; antacid, AUC ratio, 89.9% and Cmax ratio, 83.7%). No serious adverse events or deaths occurred; most adverse events were mild or moderate. In summary, oral asundexian was well tolerated and demonstrated complete bioavailability irrespective of tablet formulation, food, or gastric pH.

Keywords: anticoagulation, asundexian, BAY 2433334, bioavailability, factor XIa, pharmacokinetics

Thromboembolic disorders can be characterized by the vascular system in which they occur, namely, arterial and venous thrombotic conditions. Arterial thromboses are commonly associated with atherosclerosis, and their major clinical manifestation is ischemic stroke or ischemic heart disease, with atrial fibrillation as a major risk factor for both ischemic stroke and arterial thromboembolism. 1 Together with venous thromboembolism, which most commonly presents as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, thromboembolic disorders (and their complications) are a major cause of morbidity and death, accounting for 25% of deaths globally. 1 , 2 , 3

While the currently available anticoagulants have had a major impact on the prevention of thromboembolic events in both venous and arterial thrombotic conditions, their inherent drawbacks have led to the search for safer and more effective alternatives. Recent efforts in the development of novel anticoagulants have focused on factor XIa (FXIa), a component of the intrinsic coagulation pathway that is upstream of factor X and factor II (and thus independent of the extrinsic pathway) and, therefore, unlikely to lead to an increased risk of clinically significant bleeding. 4 , 5

Asundexian is an orally available, direct and reversible inhibitor of FXIa (Figure 1), 6 which, in accordance with its mode of action, prolongs the activated partial thromboplastin time in a concentration‐dependent manner in plasma in in vitro and in vivo experiments. In animal experiments, thrombus weight reduction up to 91% was achieved without increasing the risk of bleeding. 7 Preclinical data are supported by data from clinical pharmacology studies demonstrating that asundexian is safe and well tolerated in healthy male participants. 8 , 9 Proof of concept for antithrombotic efficacy by inhibition of FXI or FXIa in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty has been shown for 4 compounds. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Furthermore, the first clinical evidence was generated from 3 phase 2b studies with asundexian in a total of ≈4000 patients with atrial fibrillation (PACIFIC‐AF [NCT04218266] 14 ), acute myocardial infarction (PACIFIC‐AMI [NCT04304534] 15 ), and noncardioembolic ischemic stroke (PACIFIC‐STROKE [NCT04304508] 16 ). In patients at risk for cardiovascular events in PACIFIC‐STROKE and PACIFIC‐AMI receiving 10 mg, 20 mg, or 50 mg once daily, there was no observed increase in major or not clinically relevant non‐major bleeding compared with placebo on top of standard of care. 15 , 16 These results were reinforced in PACIFIC‐AF where it was demonstrated that patients who received 20 mg or 50 mg of asundexian once daily had lower rates of observed bleeding compared with apixaban. 14 In all studies, 50 mg once daily revealed consistently near complete FXIa inhibition, assessed using a fluorogenic FXIa activity assay. 14 , 15 , 16

Figure 1.

Asundexian structure.

Initial clinical pharmacology studies used an immediate‐release (IR) tablet formulation; however, an amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) IR formulation has been developed to mitigate the risk of recrystallization of the amorphous compound during storage.

In healthy male participants, maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) of asundexian were observed after a median 2–4 hours following dosing. After administration of IR tablets, systemic exposure (area under the concentration‐time curve [AUC] and Cmax) to asundexian appeared to increase in a dose‐proportional manner within the investigated range of 25–150 mg. 8 , 9 Asundexian is eliminated with a terminal half‐life of about 14–17 hours, 8 , 9 with about 8%–14% excreted as unchanged drug via urine. 9 Further studies are investigating the biotransformation and excretion pattern of asundexian (manuscript in preparation), the drug‐drug interaction profile, and the pharmacokinetics (PK) in special populations.

To support the dosing regimens used in the phase 2 program, 3 tablet strengths (5 mg, 15 mg, and 25 mg) were developed and given as 2 tablets per administration and arm, that is, 10 mg once daily, 20 mg once daily, and 50 mg once daily. A second ASD IR single 50‐mg tablet formulation was developed for phase 3 studies to optimize drug load and tablet size.

This article presents the results of 4 studies on the PK, safety, and tolerability of asundexian; an absolute bioavailability study (study 1), 2 studies that assessed the effect of both formulation and food (studies 2 and 3), and 1 that assessed the effect of gastric pH‐modifying comedications (study 4) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Day 1 Study Interventions a

| Study 1 | |

| Asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR phase 2 formulation tablet in the fasted state followed 2 hours later by 50 µg [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian IV over 30 minutes | |

| Study 2 | |

| Treatment A | Asundexian 50‐mg IR tablet in the fasted state |

| Treatment B | Asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR phase 2 formulation tablet in the fasted state |

| Treatment C | Asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR phase 2 formulation tablet 30 minutes after the start of a high‐fat, high‐calorie breakfast |

| Study 3 | |

| Treatment A | Asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR phase 2 formulation tablet in the fasted state |

| Treatment B | Asundexian 50‐mg ASD IR phase 3 formulation tablet in the fasted state |

| Treatment C | Asundexian 50‐mg ASD IR phase 3 formulation tablet 30 minutes after the start of a high‐fat, high‐calorie breakfast |

| Study 4 | |

| Treatment A | Asundexian 50‐mg IR tablet in the fasted state |

| Treatment B | 40 mg of omeprazole (2 × 20 mg) for 4 days (day −4 to day −1), and 40 mg of omeprazole (2 × 20 mg) followed 2 hours later by 50‐mg asundexian IR tablet in the fasted state |

| Treatment C | 2 × 10 mL antacid suspension followed immediately by 50‐mg asundexian IR tablet in the fasted state |

ASD, amorphous solid dispersion; IR, immediate‐release; IV, intravenous.

Administered as a single oral dose unless otherwise stated.

Methods

Study Population

Studies 1–4 enrolled healthy White men aged 18–45 years with a body mass index between 18.0 and 29.9 kg/m2.

Key exclusion criteria included any preexisting diseases for which it could have been assumed that the absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination, and effects of the study drug were abnormal; known coagulation disorders; known disorders with increased bleeding risk; and use of systemic or topical medicines or substances that opposed the study objectives or that might have influenced them. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Table S1. Each participant provided written informed consent before study entry. All 4 phase 1 studies in healthy men (registration not required) were outsourced to clinical research organizations and approved by independent ethics committees (study 1: PRA Health Sciences [now ICON, Groningen, The Netherlands] and Stichting Beoordeling Ethiek Biomedisch Onderzoek, The Netherlands; study 2: CRS Clinical Research Services Wuppertal GmbH, Germany, and North‐Rhine Medical Council [Ethikkommission bei der Aertztkammer Nordrhein]; study 3: CRS Clinical Research Services Mannheim GmbH, Germany, and Baden‐Wuerttemberg Medical Council [Ethikkommission der Landesaertzekammer Baden‐Wuerttemberg]; study 4: CRS Clinical Research Services Berlin GmbH, Germany, and the ethics committee of Berlin [Ethikkommission des Landes Berlin] and the competent authority BfArM [Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte]). Studies were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council for Harmonization guideline on Good Clinical Practice and met all local legal and regulatory requirements.

Study Design

Absolute bioavailability (F) was evaluated in study 1, a single‐center, nonrandomized, nonblinded design conducted in 16 healthy male participants with a single intervention (administration of a 30‐minute intravenous [IV] microdose of 50 µg [13C7,15N] stable‐isotope–labeled asundexian 2 hours after a single 25‐mg ASD IR tablet in the fasted state with the aim of aligning the time of expected Cmax; Table 1 and Figure S1).

Formulation and food effects were evaluated in study 2 (50‐mg IR vs 25‐mg ASD IR formulation and 25‐mg ASD IR tablet fasted vs fed) and study 3 (25‐mg ASD IR vs 50‐mg ASD IR formulation and 50‐mg ASD IR tablet fasted vs. fed). The effect of gastric pH modulation was evaluated in study 4 (4‐day pretreatment and coadministration of the proton‐pump inhibitor omeprazole [40 mg] with asundexian or coadministration with an aluminum hydroxide/magnesium hydroxide antacid [antacid; 2 × 10 mL] in the fasted state). These 3 studies were conducted in a single center using a randomized, open‐label, 3‐fold, crossover design comprising 3 treatment regimens in 3 separate periods (Latin Square design). Fifteen healthy male participants were randomized 1:1:1 to each of the 3 study interventions (Figure S1).

Pharmacokinetics

Blood samples were taken before administration of the study treatment, and over a 72‐ to 96‐hour period following administration, with timings adjusted to account for the expected Cmax after a single‐dose administration. For more details, see Table S2. Following protein precipitation with methanol containing the internal standard ([13C7,2H6,15N] asundexian), the bioanalysis of asundexian and [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian in plasma was performed using high‐pressure liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometric detection. The methods validation and analysis of study samples were performed in compliance with the pertinent guidelines on bioanalytical method validation.

Chromatographic separation was performed using a 1290 LC Binary Pump (high pressure; Agilent Santa Clara, California) and an LC column 50.0 × 2.0 mm filled with Prodigy ODS3 5 µm (Phenomenex, Torrance, California) at a flow rate of 600 µL/min. A gradient elution was used with 5%–100% ammonium acetate buffer (2 mM, pH 3) and 0%–95% acetonitrile. Mass spectrometric detection used a triplequadrupol mass spectrometer (API 4000, AB Sciex LP, Concord, Ontario, Canada) equipped with a TurboIon spray ionization source operated in negative ion mode at 400°C. The mass transitions optimized for multiple reaction monitoring tandem mass spectrometry were 593.19/439.11 Da for the analyte and 601.15/438.99 Da for the internal standard. The chromatographic separation method was transferred and cross validated for use in different laboratories.

The calibration range for liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry was from 5000 µg/L (lower limit of quantification) to 5000 µg/L for asundexian and from 0.050 µg/L to 50.0 µg/L for [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian. Mean within‐ and between‐day accuracy for back‐calculated concentrations in quality control (QC) samples during validation was 96.7%–107.8% and precision was ≤6.0%. QC samples in the concentration range from 15.0 µg/L to 4000 µg/L (3750 µg/L for study 2) were determined with an accuracy and precision ranging between 97.0%–109% and 2.4%–6.4%, respectively, for asundexian across all studies. For [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian, QC samples in the concentration range from 0.150 µg/L to 40.0 µg/L were determined with an accuracy of 100%–102% and a precision of 1.7%–5.3%. Key PK parameters assessed across the 4 studies included AUC from time 0 to infinity (AUC0‐∞) after a single dose; AUC divided by dose (AUC/D); Cmax after a single dose; Cmax divided by dose (Cmax/D); time to reach Cmax (tmax); and half‐life associated with the terminal slope.

The PK parameters were calculated using the noncompartmental method with Phoenix 8.1 (Certara, Princeton, New Jersey) software in conjunction with the noncompartmental analysis tool plugin, version 1.0, and were based on the actual sampling and dosing time.

A manuscript describing the bioanalytical methods has been submitted for publication (L. Fiebig et al, unpublished data, 2022).

Absolute Bioavailability

The F of 25‐mg ASD IR asundexian was derived from data obtained under fasted conditions and calculated as (AUC/D)oral/(AUC/D)IV (study 1).

Effect of Tablet Formulation

In studies 2 and 3, the relative bioavailability of the 25‐mg ASD IR and 50‐mg ASD IR tablet formulations of asundexian compared with the 50‐mg IR and 25‐mg ASD IR tablet, respectively, was assessed using AUC/D and Cmax/D.

Effect of Food

The effect of food was determined for the 25‐mg ASD IR and 50‐mg ASD IR formulation in studies 2 and 3 using AUC and Cmax. Asundexian was administered either without food (fasted state) or 30 minutes after the start of eating a high‐fat, high‐calorie meal (fed state). When asundexian was taken in the fasted state, participants fasted overnight for at least 10 hours before drug administration. Drinking of water was permitted until 2 hours before dosing and 2 hours after dosing. Asundexian was administered with 240 mL of noncarbonated water at room temperature. From 2 to 4 hours after dosing, up to 240 mL of water were allowed and drinking ad libitum from 4 hours after dosing onwards. Standardized lunch was provided 4 hours after drug administration.

Effect of Gastric pH Modulation

The effects of coadministration of the gastric pH modulators omeprazole or antacid (study 4) on the PK of the 50‐mg IR tablet of asundexian were evaluated using AUC and Cmax.

Safety

Safety was monitored through adverse event (AE) reporting by the participants. The investigator was responsible for detecting, documenting, and recording events that met the definition of an AE, serious AE, or AE of special interest (see Table S3). Additional safety evaluations included physical examination, blood pressure/heart rate, body temperature, and 12‐lead electrocardiogram.

Data Analysis

No formal statistical sample‐size estimation was performed owing to the exploratory nature of the studies. A minimum of 12 participants who were valid for PK evaluation were required to account for biological variability. In total, 15 participants (16 participants for study 1) were included. The PK analysis set was defined as all participants who received both treatments with valid PK profiles in study 1 and all participants with a valid PK profile for the intervention with the new tablet formulation in the fasted state in studies 2 and 3, or asundexian alone in study 4, and for at least 1 additional intervention. In all studies, the safety analysis set included all participants who received at least 1 dose of the study drug.

To compare PK between treatments, the logarithms of the PK characteristics were analyzed using analysis of variance, including sequence, participant (sequence), period, and treatment effects (studies 2, 3, and 4) or participant and treatment effects (study 1). Based on these analyses, point estimates (least‐squares means) and exploratory 90%CIs for the treatment ratios were calculated by retransformation of the logarithmic results given by the analysis of variance. Statistical evaluation of the results was performed by using the Statistical Analysis System software package 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). The effect of treatment on PK was judged on the inclusion of the 90%CIs of the AUC and Cmax ratios in the no effect boundary 80.0%–125.0%.

Results

Disposition

Overall, 60 participants received the study drug, and 58 completed the studies (Figure S2).

Of 39 individuals, 16 successfully completed screening for the assessment of F (study 1), all of whom received the study treatment, and completed the study and follow‐up. For the assessment of formulation and food effects, of the 29 individuals enrolled in study 2, 15 were randomized, all of whom received asundexian and completed the study and follow‐up. In study 3, 15 of 26 individuals successfully completed screening, all of whom received the study treatment. One participant did not complete the study but did complete follow‐up (Figure S2c); therefore, 14 participants completed the study and 15 completed follow‐up. In study 4, 37 individuals were enrolled for the evaluation of pH modulation effects, 22 of whom failed screening. Of the 15 participants who were randomized, 1 never received study drug, and 1 did not complete treatment A (but completed treatments B and C; Figure S2d). The study was completed by 13 participants, and follow‐up was completed by 14 participants. Participant characteristics were generally well balanced across all studies (Table S4).

Pharmacokinetics

PK parameters were evaluated in 59 participants (PK analysis set: study 1, N = 16; study 2, N = 15; study 3, N = 14; study 4, N = 14: Table 2). Summary statistics for all 4 studies are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Asundexian in Plasma

| Parameter | AUC0‐∞ (mg × h/L) | AUC/D (h/L) | Cmax (µg/L) | Cmax/D (10–3/L) | tmax (h) a | t1/2 (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 |

Oral n = 16 |

7.370 (1.750) [4.250–10.400] |

0.295 (0.070) [0.170–0.417] |

368 (78.5) [241–546] |

14.7 (3.14) [9.64–21.8] |

4.50 [1.50–5.00] |

14.8 (2.30) [10.5–18.2] |

|

IV n = 16 |

0.014 (0.003) [0.008–0.020] |

0.284 (0.065) [0.156–0.392] |

1.28 (0.375) [0.691–2.16] |

25.6 (7.50) [13.8–43.1] |

0.500 [0.500–0.500] |

13.7 (2.41) [9.9–17.7] |

|

| Study 2 |

Treatment A n = 15 |

13.800 (3.250) [7.520–22.300] |

0.275 (0.065) [0.150–0.447] |

716 (143) [513–1010] |

14.3 (2.86) [10.3–20.1] |

2.00 [1.00–5.07] |

15.8 (4.34) [12.3–26.1] |

|

Treatment B n = 15 |

6.530 (1.620) [3.040–10.600] |

0.261 (0.065) [0.122–0.423] |

345 (76.2) [204–480] |

13.8 (3.05) [8.2–19.2] |

3.92 [1.48–5.00] |

15.4 (3.11) [10.0–22.3] |

|

|

Treatment C n = 15 |

5.890 (1.310) [3.690–8.730] |

0.236 (0.052) [0.148–0.349] |

271 (71.3) [175–443] |

10.8 (2.85) [7.0–17.7] |

4.92 [1.48–7.97] |

15.7 (2.82) [11.9–21.4] |

|

| Study 3 |

Treatment A n = 14 |

6.940 (1.940) [3.740–11.200] |

0.277 (0.078) [0.150–0.449] |

361 (76.2) [244–478] |

14.4 (3.05) [9.8–19.1] |

4.50 [2.00–5.50] |

14.4 (2.61) [11.2–20.7] |

|

Treatment B n = 14 |

13.300 (4.240) [6.340–23.200] |

0.266 (0.085) [0.127–0.464] |

652 (180) [341–1030] |

13.0 (3.61) [6.8–20.6] |

4.25 [2.00–4.52] |

15.2 (2.90) [11.6–23.4] |

|

|

Treatment C n = 14 |

12.700 (3.740) [8.240–20.300] |

0.255 (0.075) [0.165–0.407] |

612 (144) [405–964] |

12.2 (2.88) [8.1–19.3] |

3.75 [1.00–4.53] |

15.5 (2.27) [12.8–21.2] |

|

| Study 4 |

Treatment A n = 14 |

11.700 (2.870) [7.980–17.800] |

0.233 (0.057) [0.160–0.356] |

574 (105) [444–769] |

11.5 (2.11) [8.9–15.4] |

3.99 [0.75–6.00] |

15.5 (4.36) [10.4–23.4] |

|

Treatment B n = 14 |

12.500 (3.460) [8.910–20.400] |

0.251 (0.069) [0.178–0.407] |

615 (100) [451–777] |

12.3 (2.01) [9.0–15.5] |

3.98 [1.00–4.03] |

15.6 (4.21) [9.9–24.7] |

|

|

Treatment C n = 14 |

10.500 (2.890) [5.900–16.900] |

0.211 (0.058) [0.118–0.338] |

489 (123) [303–760] |

9.78 (2.45) [6.1–15.2] |

4.00 [1.50–8.00] |

15.2 (4.67) [10.2–29.4] |

ASD, amorphous solid dispersion; AUC0‐∞, area under the concentration versus time curve from zero to infinity; AUC/D, AUC divided by dose; Cmax, maximum observed drug concentration; Cmax/D, Cmax divided by dose; IR, immediate‐release; IV, intravenous; t1/2, half‐life associated with the terminal slope; tmax, time to reach Cmax.

All data are presented as mean (SD) [range] unless otherwise stated.

Study 1: asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR tablet in the fasted state followed 2 hours later by 50 µg [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian IV over 30 minutes.

Study 2: treatment A, asundexian 50‐mg IR tablet in the fasted state; treatment B, asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR tablet in the fasted state; treatment C, asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR tablet after a high‐fat, high‐calorie breakfast.

Study 3: treatment A, asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR tablet in the fasted state; treatment B, asundexian 50‐mg ASD IR tablet in the fasted state; treatment C, asundexian 50‐mg ASD IR tablet 30 minutes after the start of a high‐fat, high‐calorie breakfast.

Study 4: treatment A, asundexian 50‐mg IR tablet in the fasted state; treatment B, 40 mg of omeprazole (2 × 20 mg) for 4 days (day −4 to day –1) and 40 mg of omeprazole (2 × 20 mg) followed 2 hours later by asundexian 50‐mg tablet in the fasted state; treatment C, 2 × 10 mL antacid suspension followed immediately by asundexian 50‐mg IR tablet in the fasted state.

Median [range].

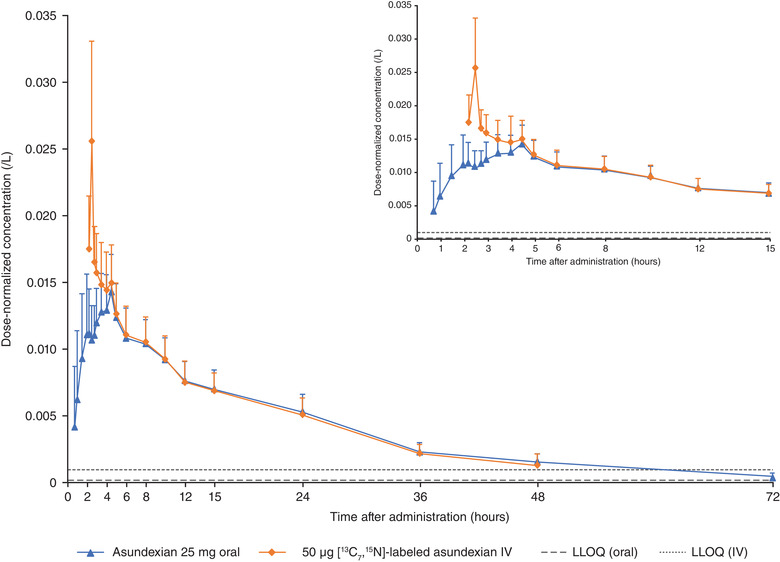

Absolute Bioavailability

In study 1, asundexian was absorbed with a median tmax of 4.5 hours after administration of a 25‐mg ASD IR tablet. [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian maximum plasma concentrations were reached at the end of the IV infusion (tmax of 0.5 hours) and, therefore, 2.5 hours after oral administration of the unlabeled compound. An overlaying decline in the dose‐normalized mean concentration versus time curves for the orally and IV‐administered asundexian is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mean (standard deviation) plasma concentrations of dose‐normalized asundexian after oral administration of asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR tablet followed 2 hours later by a 30‐minute IV infusion of 50 µg [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian (N = 16). ASD, amorphous solid dispersion; IR, immediate release; IV, intravenous; LLOQ, lower limit of quantification.

Under fasted conditions, after oral administration of the 25‐mg ASD IR tablet, the absolute bioavailability (F) of asundexian was ≈104% (ie, complete bioavailability) relative to an IV infusion with 50 µg [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian administered 2 hours after the oral dose (ratio oral/IV of AUC/D). Because F was systematically above 100% using the nominal administered IV and oral doses, an exploratory sensitivity analysis was performed taking actual doses into account (F*). Each formulation ([13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian IV and 25‐mg ASD IR tablet) was within the predefined tolerance range for release of the study medication; however, based on the respective certificates of analysis, the actual administered dose for the [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian IV formulation was slightly lower than 100% (92.9% [46.45 µg] and 95.2% [47.60 µg] for the 2 dosing cohorts) and that of the oral formulation slightly higher than 100% (104.1% [26.03 mg] for the 25‐mg ASD IR tablet). Results (arithmetic mean F* of 93.7%) supported the virtually complete bioavailability of asundexian administered as a 25‐mg ASD IR tablet in the fasted state (Table 3).

Table 3.

Assessment of the Absolute Bioavailability and Impact of Formulation, Food, and Gastric pH Modulation on Asundexian PK in Plasma (%)

| Ratio of the PK parameter of asundexian (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | PK parameter | N | Point estimate | 90%CI |

| Absolute bioavailability | ||||

| Study 1: 25‐mg ASD IR (oral)/50 µg [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian (IV) | AUC/D | 16 | 103.9 | 101.8–106.1 |

| AUC/Dactual a | 16 | 93.6 | NA | |

| Relative bioavailability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 2: 25‐mg ASD IR fasted/50 mg IR fasted | AUC/D | 15 | 94.3 | 89.2–99.8 |

| Cmax/D | 15 | 95.5 | 87.0–104.9 | |

| Study 3: 50‐mg ASD IR fasted/25 mg ASD IR fasted | AUC/D | 14 | 95.1 | 91.0–99.3 |

| Cmax/D | 14 | 88.7 | 81.4–96.7 | |

| Food effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 2: 25‐mg ASD IR fed/25 mg ASD IR fasted | AUC0‐∞ | 15 | 91.1 | 86.1–96.3 |

| Cmax | 15 | 78.3 | 71.3–85.9 | |

| Study 3: 50‐mg ASD IR fed/50‐mg ASD IR fasted | AUC0‐∞ | 14 | 96.9 | 91.4–102.7 |

| Cmax | 14 | 95.1 | 86.7–104.3 | |

| Gastric pH modulation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 4: omeprazole b | AUC0‐∞ | 14 | 106.7 | 99.0–115.1 |

| Cmax | 14 | 106.5 | 96.2–117.9 | |

| Study 4: antacid c | AUC0‐∞ | 14 | 89.9 | 83.4–96.9 |

| Cmax | 14 | 83.7 | 75.7–92.7 | |

ASD, amorphous solid dispersion; AUC0‐∞, area under the concentration versus time curve from time 0 to infinity; AUC/D, AUC divided by nominal dose; AUC/Dactual, AUC divided by the actual administered dose, Cmax, maximum observed drug concentration; Cmax/D, Cmax divided by nominal dose; IR, immediate‐release; IV, intravenous; LS, least squares; NA, not available.

Data presented as LS mean % (90%CI [%]).

Actual administered dose: 46.45 µg and 47.60 µg for the 2 dosing cohorts for the [13C7,15N]‐labeled asundexian IV formulation; 26.03 mg for the 25‐mg ASD IR tablet.

Gastric pH modulation effect based on 50‐mg asundexian IR + omeprazole/50‐mg asundexian IR.

Gastric pH modulation effect based on 50‐mg asundexian IR + antacid/50‐mg asundexia.

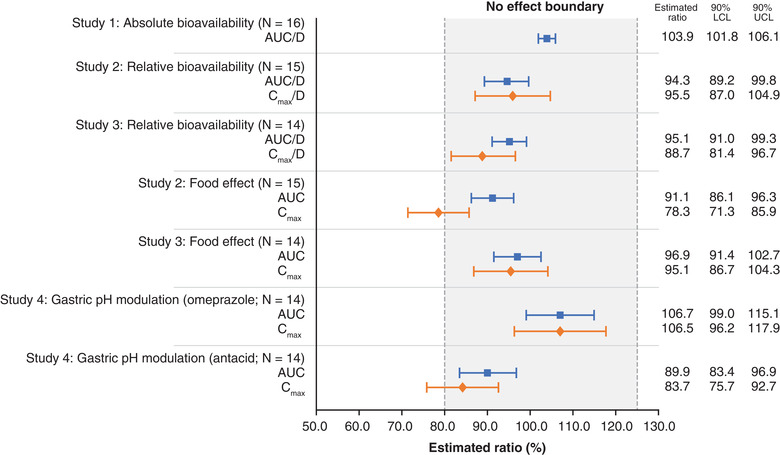

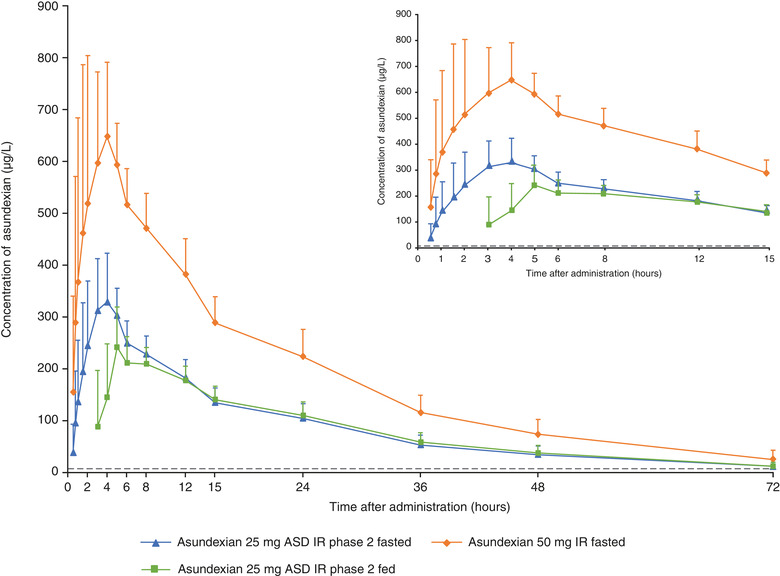

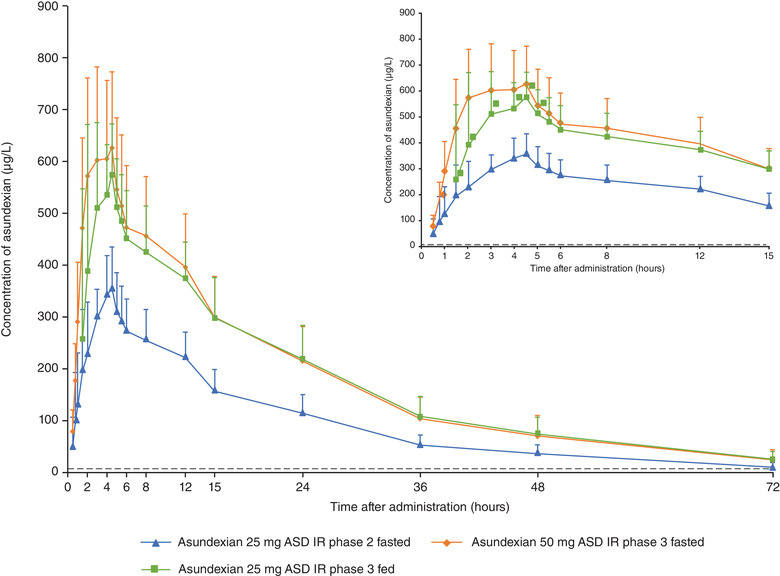

Effect of Tablet Formulation

The bioavailability of asundexian was not affected by the formulations under investigation (Table 3, Figure 3). When administered in the fasted state, in study 2, compared with the 50‐mg IR tablet, the relative bioavailability of the 25‐mg ASD IR tablet was 94.3% for AUC/D and 95.5% for Cmax/D. Similarly, in study 3, compared with the 25‐mg ASD IR formulation, the relative bioavailability of asundexian for the 50‐mg ASD IR formulation was 94.9% for AUC/D and 88.9% for Cmax/D. Point estimates and 90%CIs of the ratios were within the no effect boundary of 80.0%–125.0% (Table 3). The median tmax of asundexian for the 25‐mg ASD IR tablet was observed ≈2 hours later than for the 50‐mg IR tablet (3.9 hours vs 2.0 hours, respectively) and at approximately the same time for the ASD IR formulations, that is, the 25‐mg and 50‐mg tablets (4.5 hours vs 4.3 hours, respectively) (Table 2). Across studies 2 and 3, with the 25‐mg ASD IR tablet as a bridging arm, asundexian exposure was similar for all tablet formulations in the fasted state (Figures 4 and 5). Derived ratios for the mean AUC/D and Cmax/D comparing the 50‐mg ASD IR tablet versus the 50‐mg IR tablet were 94.8% and 89.4%, respectively, with a 2.3‐hour prolongation in tmax.

Figure 3.

AUC/D and Cmax/D by treatment. ASD, amorphous solid dispersion; AUC, area under the concentration‐time curve; AUC/D, area under the concentration‐time curve divided by dose; Cmax/D, maximum plasma concentration following administration divided by dose; IR, immediate‐release; IV, intravenous; LCL, lower confidence limit; UCL, upper confidence limit.

Figure 4.

Mean (standard deviation) plasma concentrations of asundexian after oral administration of asundexian 50‐mg IR tablet in the fasted state; asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR tablet in the fasted state; and asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR tablet after a high‐fat, high‐calorie breakfast (N = 15). ASD, amorphous solid dispersion; IR, immediate‐release.

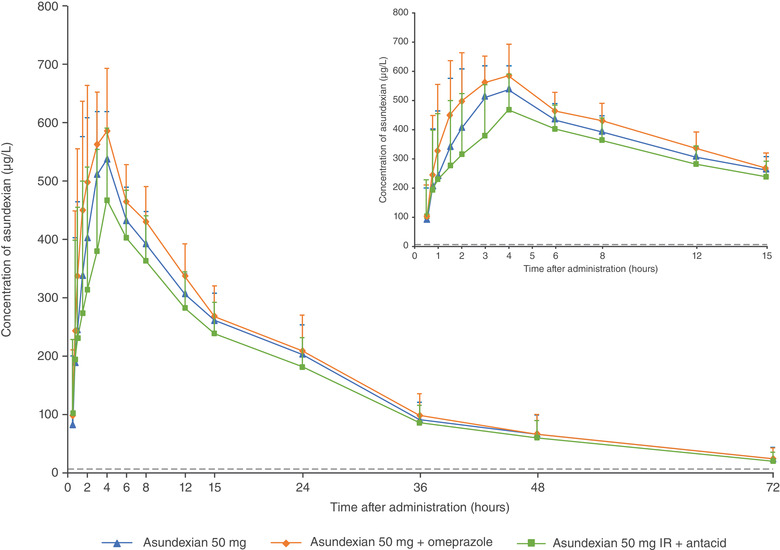

Figure 5.

Mean (standard deviation) plasma concentrations of asundexian after oral administration of asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR tablet in the fasted state; asundexian 50‐mg ASD IR tablet in the fasted state; and asundexian 50‐mg ASD IR tablet 30 minutes after the start of a high‐fat, high‐calorie breakfast (N = 14). ASD, amorphous solid dispersion; IR, immediate‐release.

Effect of Food

Compared with the fasted state, a high‐fat, high‐calorie breakfast led to an ≈1‐hour prolongation of tmax for the 25‐mg ASD IR tablet (fasted, 3.9 hours; fed, 4.9 hours), whereas median tmax values were similar for the 50‐mg ASD IR formulation between the fed (3.8 hours) and fasted states (4.3 hours; Table 2; Figures 4 and 5). For the 25‐mg ASD IR formulation, AUC/D and Cmax/D, respectively, were reduced by 8.9% and 21.7% with food relative to the fasted state. However, the exposure (AUC, Cmax) of asundexian was only minimally affected by food intake after administration of the 50‐mg ASD IR tablet (AUC, ‒3.2%; Cmax, ‒4.9%) with point estimates and 90%CIs of the ratios within the no effect boundary of 80.0%–125.0% (Table 3, Figure 3). Only the point estimate and lower limit of the 90%CI of the Cmax ratio for the 25‐mg ASD IR formulation exceeded the lower no effect boundary of 80.0% (Table 3, Figure 3).

Effect of Gastric pH Modulation

Pre‐ and coadministration with 40‐mg omeprazole resulted in an ≈7% increase in both AUC and Cmax, with point estimates and 90%CIs of the AUC ratio within the no effects boundary (Table 3, Figure 3). Coadministration of 2 × 10 mL of aluminum hydroxide/magnesium hydroxide suspension reduced the exposure of asundexian by ≈10% and 16% based on the mean ratios of AUC and Cmax, respectively. Only the lower limit of the 90%CI of the Cmax ratio of asundexian was outside the lower no effect boundary of 80.0% when coadministered with antacid (Table 3, Figure 3). Asundexian half‐life associated with the terminal slope (15.0 hours, 15.1 hours, and 14.7 hours without and with omeprazole or antacid, respectively) and tmax (4.0 hours for all treatments) were not affected by omeprazole or antacid (Table 2; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Mean (standard deviation) plasma concentrations of asundexian after oral administration of asundexian 50‐mg IR tablet in the fasted state, omeprazole 40 mg (2 × 20 mg) for 4 days (day −4 to day −1), and omeprazole 40 mg (2 × 20 mg) followed 2 hours later by asundexian 50‐mg IR tablet in the fasted state and 2 × 10 mL antacid suspension followed immediately by asundexian 50‐mg IR tablet in the fasted state (N = 14). ASD, amorphous solid dispersion; IR, immediate‐release.

Safety

A summary of AEs is presented in Table S5. Safety was evaluated in a total of 60 participants (study 1, N = 16; study 2, N = 15; study 3, N = 15; study 4, N = 14). Across all studies, a total of 15 participants (25.0%) experienced at least 1 treatment‐emergent AE (TEAE; study 2, n = 3; study 4, n = 8; study 1, n = 3; study 3, n = 1). Of these, 1 TEAE was considered by the investigator to be related to treatment with asundexian (study 4; headache, mild). Of these 15 TEAEs, 14 were mild and 1 moderate (study 3; back pain) in intensity. No deaths or serious AEs occurred in any study. One AE of special interest was reported in study 2 (elevated amylase [4.1 times upper limit of normal] with concurrent normal lipase; asundexian 25‐mg ASD IR fasted).

For studies 1–3, all AEs had resolved by the end of the study. In study 4, 1 participant experienced 1 AE (chalazion) that was recovering/resolving at the end of the study; another participant experienced a posttreatment AE (skin lesion, mild) that had not recovered/not resolved at the end of the study. No clinically relevant changes were observed in vital signs or electrocardiogram parameters for any participant in any study.

Discussion

Asundexian is an oral inhibitor of the coagulation factor FXIa and is under clinical investigation for efficacy and safety in patients at risk for thromboembolic events.

The primary aim of these studies was to elucidate factors potentially affecting the absorption and subsequent bioavailability of asundexian (eg, drug formulation, food, and pH modulation) as an important step to providing dosing recommendations for future studies.

Asundexian demonstrated complete bioavailability under fasting conditions; this conclusion is supported considering the nominal doses as well as by a sensitivity analysis that accounted for the actual doses (within the specification for release of the study drug) of the tablet and IV formulation. These results are also in line with those of a previous study that suggested a high oral bioavailability of asundexian based on the observed low to moderate interindividual variability and the low oral clearance. 8 This indicates that asundexian is a low‐clearance drug with negligible first‐pass metabolism, and that the bioavailability of the IR tablet compared with an oral solution is not limited by solubility. 8

As shown in studies 2 and 3, differences in oral IR tablet formulation (ie, 50‐mg IR, 25‐mg and 50‐mg ASD IR) had no effect on the bioavailability of asundexian. These results are supported by a previous study showing a similar exposure of the oral solution (AUC/D and Cmax/D of 0.265 h/L and 14.9 × 10−3/L, respectively) to that observed for the tablet formulations in both studies with AUC/D and Cmax/D ranging from 0.253 h/L to 0.268 h/L and from 12.6 to 14.1 × 10−3/L, respectively, and a high relative bioavailability of a 5‐mg IR tablet compared to the oral solution (AUC, 89.5%; Cmax, 86.0%). 8 A high‐fat, high‐calorie breakfast also had only a minimal effect on the bioavailability of asundexian. These findings are in agreement with, and even less pronounced than previous food‐effect data that show a reduction in AUC and Cmax by 12.4% and 31.4%, respectively, after administration of a 5‐mg IR tablet. 8 Further, gastric pH modulation does not appear to have any effect on bioavailability, as demonstrated by pretreatment and coadministration of 40 mg of omeprazole; coadministration with antacid had a minor effect on the rate of absorption of asundexian that is expected to be mainly related to adsorption effects and/or delayed gastric emptying.

In addition, data showed that neither food nor gastric pH modulation had a clinically relevant effect on the bioavailability and PK of asundexian, with point estimates and 90%CIs of all AUC/D ratios included in the no effect boundary. The only values that slightly exceeded the lower no effect boundary of 80% were the point estimate and lower limit of the 90%CI of the Cmax ratio investigating the food effect on the 25‐mg ASD IR formulation in study 2, and the lower limit of the 90%CI of the Cmax ratio investigating of the effect of antacid in study 4. This is not considered to be clinically relevant.

Because of the high bioavailability, the permeability of asundexian is considered to be high. As expected for neutral compounds, changes in pH do not lead to changes in solubility, supporting the observation that gastric pH modulation did not have a meaningful effect on the bioavailability of asundexian. Subsequently, absorption of asundexian is not limited by solubility or permeability under a variety of conditions and first‐pass metabolism in the gut and/or liver does not play an important role in its bioavailability, as expected for a low‐clearance drug. The interindividual variability was low to moderate and was not influenced in a meaningful way by any of the factors under investigation (Table 2).

The high bioavailability of asundexian is expected to remain valid for the doses currently under investigation in ongoing phase 2b studies (ie, 10, 20, and 50 mg once daily). It has been shown that exposure to asundexian (AUC and Cmax) increased in a dose‐proportional manner in this dose range and that the PK is independent of time. 8 , 9

In these small‐scale, short‐term phase 1 studies, asundexian was found to be well tolerated. Only 1 reported TEAE was considered by the investigator to be related to treatment with asundexian (study 4; headache, mild); there were no deaths or serious TEAEs, there were no discontinuations due to AEs, and all TEAEs were mild or moderate in intensity. The majority of AEs had resolved by the end of the studies. In addition, there were no clinically relevant changes in laboratory profiles (with the exception of the mode of action–related prolongation of activated partial thromboplastin time), vital signs, or electrocardiogram results.

Several limitations of these studies should be noted. First, due to the lack of data from reproductive studies, women were excluded, therefore limiting the study population solely to healthy White men. Second, the number of participants was small, and all studies were single dose, thereby limiting the assessment of safety. However, studies have been performed (PACIFIC program 14 , 15 , 16 ) that consistently demonstrate the safety of asundexian at doses up to 50 mg once daily, and phase 3 studies are under way in a variety of cardiovascular disorders and in larger study populations than reported in this article to investigate further the safety and efficacy of asundexian.

Conclusions

When orally administered, asundexian is entirely bioavailable in the fasted state. The effects of food, formulation, and pH modulation on the bioavailability of asundexian are not considered to be of clinical relevance. These results have guided the dosing recommendations (that asundexian can be taken independently of food and coadministered with pH modulators) for completed phase 2b (PACIFIC program) and planned phase 3 studies (OCEANIC‐AF and OCEANIC‐STROKE).

Across all studies, at doses of 25 mg and 50 mg, in the fasted and fed states, and when coadministered with pH modulators, a single TEAE was considered to be related to asundexian treatment. The amount of safety data was limited due to the small overall number of participants; however, when taken together with the inherent limitations of phase 1 trials, asundexian was found to be well tolerated in healthy White men.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

FK, CB, SU, and DK are employees of Bayer AG, and own shares or share options. All studies were funded by Bayer AG. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK, funded by Bayer AG.

Supporting information

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the volunteers who participated in the studies and the following investigators for their assistance in conducting the studies: Annemone Köchel, CRS Wuppertal (study 2); Dr Sybille Baumann, MD, CSR Berlin (study 4); Dr Jeroen van de Wetering, MD, PRA (study 1); and Dr Helen Basse, CRS Mannheim (study 3). The authors than the following for statistical support: Stephanie Fechtner MS (study 2); Jana Distler MS (study 4); and Katharina Sommer MS (study 3). Additional thanks go to Dr Dorina van der Mey, Bayer AG (study 2, study 4), Dr Michael Gerisch and Patricia Egidi, Bayer AG (study 3), for PK support; Peter Nagy, Bayer AG (study 3), for study medical expert support; and Dr Lukas Fiebig, Bayer AG (study 1, study 4), and Dr Alexander Schriewer, Swiss BioQuant (study 2, study 3), for the bioanalysis of asundexian. The authors also thank Jim Purvis PhD of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK, for providing medical writing support in accordance with Good Publication Practice 3 guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3). Editorial support was provided by Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK.

References

- 1. Gregson J, Kaptoge S, Bolton T, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with venous thromboembolism. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(2):163–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raskob GE, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco AN, et al. Thrombosis: a major contributor to global disease burden. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(11):2363–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wendelboe AM, Raskob GE. Global burden of thrombosis: epidemiologic aspects. Circ Res. 2016;118(9):1340–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gailani D, Gruber A. Factor XI as a therapeutic target. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(7):1316–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang H, Lowenberg EC, Crosby JR, et al. Inhibition of the intrinsic coagulation pathway factor XI by antisense oligonucleotides: a novel antithrombotic strategy with lowered bleeding risk. Blood. 2010;116(22):4684–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization . WHO Drug Information. 2021;35(1):102. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heitmeier S, Visser M, Tersteegen A, et al. Pharmacological profile of asundexian, a novel, orally bioavailable inhibitor of factor XIa. J Thromb Haemost. 2022;20(6):1400–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomas D, Kanefendt F, Schwers S, et al. First evaluation of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of BAY 2433334, a small molecule targeting coagulation factor XIa. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(10):2407–2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kubitza D, Heckmann M, Distler J, et al. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of BAY 2433334, a novel activated factor XI inhibitor, in healthy volunteers: A randomized phase 1 multiple‐dose study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(7):3447–3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weitz JI, Bauersachs R, Becker B, et al. Effect of osocimab in preventing venous thromboembolism among patients undergoing knee arthroplasty: the FOXTROT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(2):130–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weitz JI, Strony J, Ageno W, et al. Milvexian for the prevention of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(23):2161–2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buller HR, Bethune C, Bhanot S, et al. Factor XI antisense oligonucleotide for prevention of venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):232–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Verhamme P, Yi BA, Segers A, et al. Abelacimab for prevention of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):609–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Piccini JP, Caso V, Connolly SJ, et al. Safety of the oral factor XIa inhibitor asundexian compared with apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation (PACIFIC‐AF): a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, double‐dummy, dose‐finding phase 2 study. Lancet. 2022;399(10333):1383‐1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rao SV, Kirsch B, Bhatt DL, et al. A multicenter, phase 2, randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, parallel‐group, dose‐finding trial of the oral factor XIa inhibitor asundexian to prevent adverse cardiovascular outcomes following acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2022;146(16):1196–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shoamanesh A, Mundl H, Smith EE, et al. Factor XIa inhibition with asundexian after acute non‐cardioembolic ischaemic stroke (PACIFIC‐Stroke): an international, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10357):997–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information