Abstract

Introduction

The incidence of fracture and surgery of the hip and lower extremities is still high. Long postoperative bed rest can potentially increase the incidence of various complications that may increase patients’ morbidity and mortality rate after hip and lower extremities surgery. This literature review aimed to identify the effects of early mobilization on hip and lower extremity postoperative.

Methods

Search for articles on several databases such as ProQuest, ScienceDirect, CINAHL, Medline, Wiley Online, and Scopus, using the Boolean operator tools with “AND” and “OR” words by combining several keywords according to the literature review topic, with inclusion criteria of those published in the last three years (2019–2021), using a quantitative design, written in English and full-text articles. A total of 435 articles were obtained, screened, and reviewed so that there were 16 (sixteen) eligible articles.

Results

There were 11 (eleven) effects of early mobilization, that is, shorter the length of stay, lower postoperative complication, lower the pain, increase walking ability, increase quality of life, decrease the rate of readmission, decrease mortality rate, lower the total hospitalization cost, higher number of physical therapy sessions prior to discharge, increase in satisfaction, and no fracture displacement or implant failure.

Conclusion

This literature review showed that early mobilization is safe and effective in postoperative patients to reduce the risk of complications and adverse events. Nurses and health workers who care for patients can implement early mobilization and motivate patients to cooperate in undergoing early mobilization.

Keywords: early mobilization, hip, lower extremity, postoperative

Introduction

The incidence of hip and lower extremity fractures are still high, occurring about 100 per 100,000 people each year (Kenyon-Smith et al., 2019). Hip fracture more often occurs in females compared to males where half of them never walk independently again (Warren et al., 2019). Among elderly people, hip fractures are common, now become the second leading cause of hospitalization, and it became a serious injury that could lead to loss of mobility and independency (Baer et al., 2019; Rutenberg et al., 2020). It has significant socioeconomic consequences (Baer et al., 2019). Consigliere et al. (2019) reported that only 58.4% of very elderly patients with hip fractures who received rehabilitation were able to return to their original address to live independently.

Managing those kinds of fractures is still challenging (Consigliere et al., 2019). In several countries, hip fractures are managed by traction until surgical treatment (Biz et al., 2019). Surgery on the hip and lower extremities, especially on the femur and knee, is also increasingly common, and most patients undergoing surgery are elderly accompanied by various comorbidities.

Although surgical and anesthetic techniques have improved, morbidity and mortality rates following pelvic and lower extremity surgery are still high (Flikweert et al., 2018; Jennison & Yarlagadda, 2019; Kuru & Olcar, 2020). A high morbidity rate is found in half of the patients with hip fractures who cannot achieve the pre-operative ability to carry out daily activities (Svenøy et al., 2020). In hip fracture postoperative, the mortality rate was 37.1% in men and 26.4% in women (Kannegaard et al., 2010). The one-year mortality rate of hip surgery is about 12–36% (Kenyon-Smith et al., 2019; Rutenberg et al., 2020; Warren et al., 2019), and the mortality rate is about 8 times in patients above 80 years old (Kenyon-Smith et al., 2019).

This high morbidity and mortality rate is associated with some complications due to prolonged bed rest after surgery (Kenyon-Smith et al., 2019). Complications may include heart failure, thromboembolism, pneumonia, pressure ulcers, wound healing disorders, and delirium (Flikweert et al., 2018; Song et al., 2020). Another complication Biz et al. (2020) reported was the failure of femoral fracture osteosynthesis.

Early mobilization may reduce postoperative complications due to prolonged bed rest and has some benefits, so early mobilization is widely implemented. Prolonged bed rest, sedation, and immobilization are strongly associated with neuromuscular dysfunction and physical injury, and early mobilization is a valuable intervention to treat them (Koukourikos et al., 2020). Early mobilization is defined as the movement of the lower extremities performed within 24 h of surgery (Kuru & Olcar, 2020). In addition, early mobilization is defined as a physical activity carried out at appropriate intervention, providing benefits to the body and improving circulation, peripheral and central perfusion, ventilation and level of consciousness. Early mobilization program may consist of passive and active range of motion (ROM), active side-to-side turning, cycling in bed, exercises in bed, sitting on the edge of the bed, transferring from bed to a chair, marching on the spot, ambulation, hoist therapy, tilt table, active resistance exercises, and electrical muscle stimulation (Koukourikos et al., 2020).

Baer et al. (2019) reported that early mobilization could affect short-term (such as reduced complication and shortened length of stay [LOS]) and long-term outcomes (such as increased autonomy and reduced mortality). Early mobilization is not without risks. Early mobilization can increase the risk of falls and patient discomfort, so it has to be carefully implemented (Haslam-Larmer et al., 2021). It was reported that mobilizing patients as early as the day of surgery still became an uncommon practice (Chua et al., 2020). Therefore, a literature review is needed to identify the effects of early mobilization in the hip and lower extremity postoperative.

Methods

Searching Strategy

This literature review used articles from databases ProQuest, Science Direct, CINAHL, Medline, Wiley Online, and Scopus. Relevant articles were searched using Boolean operators, such as the word “AND,” “OR.” “AND” is used to join words or phrases when both (or all) the terms must appear in the items retrieved. This search query would return a much smaller set of records, and the items found would be more specific to the research question. If retrieving too many records, adding another search term with the Boolean Operator “AND” was conducted. “OR” was used to join synonymous or related terms and instruct the search tool to retrieve any record that contains either (or both) of the terms, thus broadening the search results. The “OR” operator is particularly useful when unsure of the words used to categorize a topic or if the information on a topic is even available. If retrieving too few records, the search was broadened by adding a synonym with the Boolean Operator “OR”; mixed method appraisal tools were used to evaluate the included studies by combining several keywords, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Words Used to Search the Articles From Databases.

| Early mobilization | AND | Effect | AND | Lower extremity | AND | Postoperative |

| OR | OR | OR | OR | |||

| Early mobility | Benefit | Lower limb | After surgery | |||

| OR | ||||||

| Hip OR knee |

Inclusion Criteria

The articles used in this literature review were those published in the last three years (2019–2021), using a quantitative design, having full text and using English. The articles used in this study consisted of original articles, randomized controlled trial articles, cohort study articles, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis articles. The inclusion criteria applied to the sample or population of articles:

- Adult patient (≥ 18 years old)

- Underwent early ambulation (24 h surgery)

- Not caused by a tumor (malignancy)

Article search comprised four steps: identification of articles from six databases, screening process based on title and abstracts and identification of excluded articles with reasons, eligible articles assessment and excluded articles with reasons, and total articles review.

Results

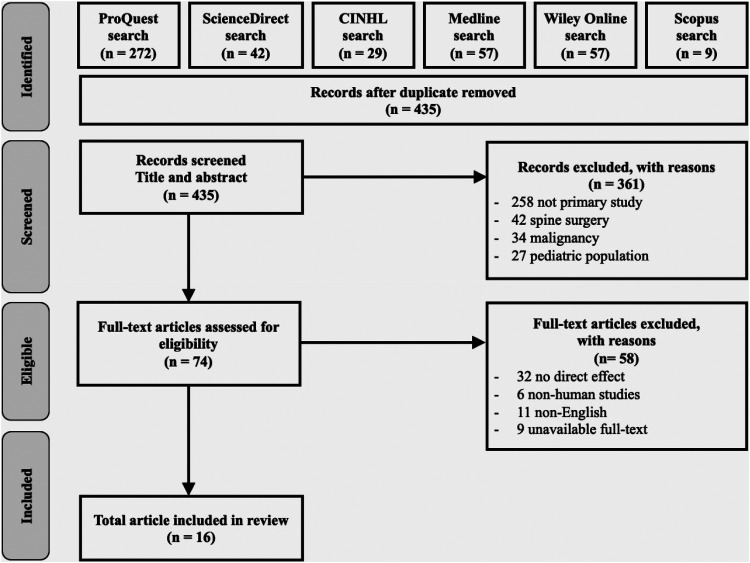

The identification of articles from six databases obtained 466 articles. It consisted of 272 from ProQuest, 42 from ScienceDirect, 29 from CINAHL, 57 from Medline, 26 from Wiley Online, and 9 from Scopus. After duplicate removal, 435 articles were recorded for the next step. The research articles were screened and reviewed based on inclusion criteria and relevance to the topics (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of literature review process.

Sixteen articles were obtained to be included in this literature review (Table 2). These articles used different research designs, mostly with retrospective study (seven studies). Research locations were mostly reported in Europe (four articles). Among 16 articles, it showed that there are 11 (eleven) effects of early mobilization, which consisted of lower postoperative complication (six studies), shorter the LOS (eight studies), lower the total hospitalization cost (one study), lower the pain (four studies), increase walking ability (three studies), increase the quality of life (two studies), higher number of physical therapy sessions prior to discharge (one study), decrease the rate of readmission (two studies), increase in satisfaction (one study), decrease mortality rate (two studies), and no fracture displacement or implant failure (one study) (Table 3). Shorter the LOS became the effect that was mostly reported (eight studies).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Studies Included in the Literature Review.

| Author names | Publication date | Study design | Study population | Interventions | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenyon-Smith, et al. | 2019 | Retrospective study | 240 patients (female = 165, male = 75, mean age: 82.2 years) admitted to a level 1 trauma center in Adelaide, Australia, for hip fracture surgery | Early mobilization on postoperative complications assessed along with premorbid status | The odds of developing a complication were 1.9 times higher if the patient remained bedbound than mobilizing. Premorbid health and postoperative delirium are better indicators of postoperative complications than time to mobilization. |

| Lei et al. | 2021 | Cohort study | Group A = 2687 patients with knee osteoarthritis who had undergone Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) at 24 large teaching hospitals who began ambulating within 24 h; Group B = 3761 patients who began ambulating later than 24 h; in the Chinese population | Ambulating within 24 h (group A) and later than 24 h (group B) | The early ambulation group (Group A) had a shorter length of stay (LOS) and lower hospitalization costs and pain levels than the late ambulation group (Group B). There was a favorable effect in enhancing range of motion (ROM) for patients in Group A compared with patients in Group B. In Group A, patients had significantly higher postoperative SF-12 scores than those in Group B. The incidence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary infection was significantly lower in Group A than in Group B. The incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE) and other complications did not differ between the two groups. |

| Kuru & Olcar | 2020 | Retrospective study | 52 geriatric patients with intertrochanteric and femoral neck fractures in a tertiary Training and Research Hospital in Turkey | Early mobilization and weight bearing on postoperative walking ability and pain | Early mobilization and full weight bearing in geriatric patients after hip fracture surgery shortened the length of stay in the hospital, increased walking ability, and positively affected postoperative functional outcomes and reduced pain. |

| Haslam-Larmer, et al. | 2021 | A descriptive mixed method embedded case study | The main case was one postoperative unit in a large tertiary care center located in Toronto, Ontario, and the embedded units were patients (and their families) recovering from hip fracture repair. Data from multiple sources were obtained to understand mobility activity initiation and patient participation. | No intervention | There are multi-level factors that require consideration when implementing best practice interventions: systemic, provider-related, and patient-related healthcare. An increased risk of poor outcomes occurs with compounding multiple factors, such as a patient with low pre-fracture functional mobility, cognitive impairment, and a mismatch of expectations. The study reports several variables to be important considerations for facilitating early mobility. Communicating mobility expectations and addressing physical and psychological readiness are essential. |

| Richtrmoc et al. | 2020 | Experimental study | 40 patients admitted to an adult Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in the Real Hospital Português de Beneficência em Pernambuco in Recife, Brazil, who met the inclusion criteria | Early mobilization protocol was structured in 5 steps according to the consciousness level and the scope of the functional criterion proposed for each stage. | Early mobilization protocol applied to spontaneous-breathing patients in ICU is safe and seemed effective at maintaining/increasing their respiratory muscle strength and functionality in a short period of ICU stay. Ceiling effect was high for the Medical Research Council scale (MRC-s), Functional Status Score for the Intensive Care Unit (FSS-ICU), and Functional Independence Measure (FIM) scales. |

| Warwick et al. | 2019 | Retrospective study | 2051 total joint arthroplasty (TJA) procedures performed at a single academic medical center in Durham, USA | No intervention | Barriers to receiving immediate physical therapy (PT) following TJA included general anesthesia, later operative start time, longer operative time, and higher daily caseload. These factors present potential targets for improving the delivery of immediate postoperative PT. Early PT may help reduce 30-day readmissions, but additional research is necessary to further characterize this correlation. |

| Flikweert et al. | 2018 | Prospective cohort study | 479 patients aged ≥60 treated for a hip fracture at University Medical Center Groningen between July 2009 and June 2013 | A comprehensive multidisciplinary care pathway | The mean age of patients was 78.4 (SD 9.5) years; 33% were men. The overall complication rate was 75%. Delirium was the complication seen most frequently (19%); the incidence of surgical complications was 9%. Most risk factors for complications were not preventable (high comorbidity rate, high age and dependent living situation). However, general anesthesia (OR 1.51; 95% CI 0.97–2.35) and delay in surgery (OR 3.16; 95% CI 1.43–6.97) may be risk factors that can potentially be prevented. Overall, the mortality risk was not higher in patients with a complication, but delirium and pneumonia were risk factors for mortality. |

| Deng et al. | 2018 | Meta-analysis | 25 studies involving 16,699 patients that met the inclusion criteria | Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) on the postoperative recovery of patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) or total knee arthroplasty (TKA) | Compared with conventional care, ERAS was associated with a significant decrease in mortality rate (relative risk (RR) 0.48, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.85), transfusion rate (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.51), complication rate (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.87) and in-hospital length of stay (LOS) (mean difference (MD) -2.03, 95% CI −2.64 to −1.42) among all included trials. However, no significant difference was found in the range of motion (ROM) (MD 7.53, 95% CI −2.16 to 17.23) and 30-day readmission rate (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.30). There was no significant difference in complications of TKA (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.06) and transfusion rate in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.88) between the ERAS group and the control group. |

| Sattler, Hing, & Vertullo | 2020 | No information | No information | No information | Rapid recovery protocols have been shown to be effective at reducing the length of stay, postoperative pain and complications without compromising patient safety. These rapid recovery protocols include same-day mobilization; blood preservation protocols; self-directed pedaling-based rehabilitation; and individualized targeted discharge to self-directed, outpatient therapist-directed or inpatient therapist-directed rehabilitation. Low-cost self-directed rehabilitation should be considered usual care, with inpatient rehabilitation reserved for the minority of at-risk patients. |

| Rutenberg et al. | 2020 | A retrospective cohort study | 851 patients 65 years and older, who were treated operatively following fragility hip fractures at Tel Aviv University, Israel; 369 (43.4%) had recurrent hospitalizations within the first postoperative year. | No intervention | Rehospitalized patients were more likely to be males, to use a walking aid and live dependently. They had a higher age-adjusted Charlson's comorbidity index (ACCI) score, a higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation, lower hemoglobin, worse renal function, less platelets, and longer time to surgery. The prevalence of in-hospital complications was similar. Six variables were found to independently influence the chance for readmissions: male gender, using a walking aid, higher ACCI score, lower hemoglobin, atrial fibrillation, and a longer surgical delay. Only the first four were found to be adequate predictors and were added to the prediction formula. |

| Chua et al. | 2020 | A before-after (quasi-experimental) study | Five hundred twenty consecutive patients (n = 278, Before; n = 242, After) treated at an arthroplasty center in South West Sydney Australia | Standard practice pre-implementation of the new protocol was physiotherapist-led mobilization once per day commencing on postoperative Day 1 (Before phase). The new protocol (After phase) aimed to mobilize patients four times by the end of Day 2, including an attempt to commence on Day 0; physiotherapy weekend coverage was necessarily increased. | The new protocol was associated with no change in unadjusted length-of-stay (LOS), a small reduction in adjusted LOS (8.1%, p = .046), a reduction in time to first mobilization (28.5 (10.8) vs. 22.6 (8.1) hours, p < .001), and an increase in the proportion mobilizing Day 0 (0 vs. 7%, p < .001). Greater improvements were curtailed by an unexpected decrease in physiotherapy staffing (After phase). There were no significant changes to the rates of complications or readmissions, joint-specific pain and function scores or health-related quality of life to 12 weeks post-surgery. Qualitative findings of 11 multidisciplinary team members highlighted the importance of morning surgery, staffing, and well-defined roles. |

| Baer et al. | 2019 | A retrospective study | 219 patients aged 70 years or older who were treated with surgical procedures after a hip fracture at University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland | No intervention | A shorter time between the operation and first mobilization was significantly associated with lower in-hospital mortality and complications. Early mobilization (within 24 h after the operation) and full weight bearing had no influence on pain, mobility of the hip, and ability to walk as well as the length of stay in our cohort. Fracture type and treatment influenced the mobility of the hip, while age and physical health status affected the ability to walk. |

| Aprato et al. | 2020 | A cross-sectional study | 516 patients older than 65 years admitted at a level I trauma center with proximal femoral fracture during a 1-year period in Turin, Italy | No intervention | The mean age was 83.6 years; ASA score was 3–5 in 53% of patients; 42.7% presented with medial fracture; mean time between admission and surgery was 48.4 h; 22.7% of patients were not able to walk during the first 10 days after fracture; mean duration of hospitalization was 13 days; and mortality was 17% at 6 months and 25% at 1 year. Early surgery and walking ability at 10 days after trauma were independently and significantly associated with mortality at 6 months (p = .014 and 0.002, respectively) and 1 year (0.027 and 0.009, respectively). |

| Consigliere et al. | 2019 | Retrospective study | 51 patients in London, UK, who were divided into two groups of patients surgically treated for distal femur fractures with respect to their rehabilitation protocol and postoperative instructions | Group A (delayed weight-bearing/DWB) was instructed not to weight bear (NWB) or to toe touch weight bear (TTWB), while group B (early weight-bearing/EWB) started to weight bear soon after surgery without specific restrictions. | The results showed no statistically significant differences in the two groups regarding gender, type of injury, and type of operation. No postoperative complications in the EWB group. Six complications were observed in the non-weight-bearing group (four fractures displacement and two implants failure at 12-week follow-up). Distal femur fractures treated with locking plates can be rehabilitated with EWB to allow early return to function. There is no evidence that EWB increases the risk of fracture displacement or implant failure in distal femur fractures treated with distal locking plates. Instead, it is possible that postoperative non-weight-bearing status delays the fracture-healing process increasing the risk of fixation failure. |

| Warren et al. | 2019 | No explanation | 7947 patients; 4040 underwent a cephalomedullary nail procedure, 1138 patients underwent a sliding hip screw procedure, and 2769 patients underwent hip hemiarthroplasty or internal fixation procedures in Cleveland, USA | No intervention | Among the cephalomeddullary nail patients, weight-bearing as tolerated (WBAT) on a postoperative day one (POD1) was associated with a decreased likelihood of mortality. In the cephalomedullary nail and sliding hip screw treatment groups, patients were less likely to experience major and minor complications if they were WBAT on POD1. WBAT patients had a shorter length of stay (LOS) in the sliding hip screw and cephalomedullary nail treatment groups. Patients were less likely to be discharged to a non-home facility when WBAT on POD1, regardless of treatment. |

| Gautreau et al. | 2020 | A retrospective study | 283 patients who had a primary total joint arthroplasty (TJA) and mobilized on the day of surgery (POD0) in The Moncton Hospital, Canada | No intervention | The Hall group had a significantly shorter length of stay than all other groups. There were sex differences across the mobilization groups. Farther mobilization was predicted by younger age, male sex, lower body mass index, spinal anesthesia and fewer symptoms limiting mobilization. Shorter LOS was predicted by male sex, lower body mass index, lower American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification score, less pain/stiffness and farther mobilization on POD0. |

Table 3.

Effect of Mobilization Identified From 16 Articles Obtained After Screened and Reviewed Based on Inclusion Criteria and Relevance to the Topics.

| Kenyon-Smith, et al. (2019) | Lei et al. (2021) | Kuru & Olcar (2020) | Haslam-Larmer, et al. (2021) | Richtrmoc et al. (2020) | Warwick et al. (2019) | Flikweert, et al. (2018) | Deng et al. (2018) | Sattler, Hing, & Vertullo (2020) | Rutenberg, et al. (2020) | Chua, et al. (2020) | Baer, et al. (2019) | Aprato, et al. (2020) | Consigliere, et al. (2019) | Warren, et al. (2019) | Gautreau, et al. (2020) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of early mobilization | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. Lower postoperative complication | ||||||||||||||||

| a. Delirium | ||||||||||||||||

| b. Pulmonary infection | ||||||||||||||||

| c. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) | ||||||||||||||||

| d. Pneumonia, atelectasis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), sepsis, myocardial infarction and stroke | ||||||||||||||||

| e. Complication rate | ||||||||||||||||

| f. Reducing risk of wound infection | ||||||||||||||||

| g. Pressure sore | ||||||||||||||||

| h. Transfusion | ||||||||||||||||

| i. C. diff infection | ||||||||||||||||

| j. Major complication (deep incisional surgical site infection (SSI), unplanned reintubation, cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)) | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Shorter the length of stay (LOS) | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Lower the total hospitalization costs | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Lower the pain | ||||||||||||||||

| a. Lower the visual analog scale (VAS) score at 72 h after surgery | ||||||||||||||||

| b. Higher score of pain subscale of Harris hip score (positive effect on postoperative pain) | ||||||||||||||||

| c. Less pain | ||||||||||||||||

| d. Reducing postoperative pain | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Increase walking ability | ||||||||||||||||

| a. Favorable effect in enhancing range of motion (ROM) | ||||||||||||||||

| b. Higher score of Harris hip score (slight, occasional, no compromise in activity) | ||||||||||||||||

| c. Improving extremity function and ability to walk | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Increase the quality of life | ||||||||||||||||

| a. Higher postoperative of the 12-item Short Form Survey (SF-12) score | ||||||||||||||||

| b. Improve health-related quality of life | ||||||||||||||||

| 7. Higher number of physical therapy sessions prior to discharge | ||||||||||||||||

| 8. Decrease the rate of readmission | ||||||||||||||||

| a. Decrease the rate of unplanned 30-day readmission | ||||||||||||||||

| b. Reducing readmission | ||||||||||||||||

| 9. Increase in satisfaction | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. Decrease mortality rate | ||||||||||||||||

| 11. No fracture displacement or implant failure |

Among 16 articles, it was found that there were various definitions of early ambulation, different weight bearing scheme, and different patients’ age (Table 4). Among 16 articles, four articles defined early ambulation as within 24 h, one article defined it as immediate PT between 8 h of surgery, and one article defined it as ambulation 4–8 h after total knee replacement. Regarding the weight-bearing scheme, 10 studies did not report it specifically. Three studies recruited patients who were categorized as having partial or full weight-bearing activities. One study used the term delayed weight-bearing (DWB) and early weight-bearing. One study used the term weight-bearing as tolerated on postoperative day one and those that did not/non-weight-bearing tolerated. One study only reported that all patients were allowed full weight bearing after surgery. Among 16 articles, elderly patients were included in eight studies.

Table 4.

The Timing of Mobilization, Weight-Bearing Scheme, and the Characteristics of Patients.

| Author (year) | Timing of mobilization | Weight-bearing scheme: full or partial weight bearing | Characteristics of patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kenyon-Smith, et al. (2019) | Within 24 h as per the Australian and New Zealand hip fracture guidelines |

|

Patients with hip fracture surgery comprised 165 females and 75 males, with a mean age of 82.2 years. |

| Lei et al. (2021) | Within 24 h (group A) and later than 24 h (group B) after unilateral total knee arthroplasty | Early ambulation was defined as any partial or full weight-bearing activities (walking on the spot, bed-to-chair or bed-to-toilet) under the supervision of a physiotherapist within 24 h. |

|

| Kuru & Olcar (2020) | Mobilization of the patients was categorized as (a) within 24 h,

(b) between 24 and 48 h, and (c) after 48 h. Early mobilization was defined as the first mobilization of the patient within 24 h after surgery and late mobilization after 24 h. |

All patients were asked to bear full weight on the first operative day. Patients were categorized as full weight-bearing or partial weight bearing | 52 geriatric patients who underwent partial prosthesis surgery following hip fracture aged over 65 years old |

| Haslam-Lamer, et al. (2021) | No information | No information | Adults 65 years old or older, admitted for surgical repair of a fragility hip fracture with postoperative admission to the unit of study |

| Richtrmoc et al. (2020) | The early mobilization protocol of this study was adopted from previous studies (Barros et al., 2015; Morris et al., 2008) and was structured in 5 steps according to the consciousness level and the scope of the functional criterion proposed for each stage | No information | 40 non-intubated patients over 18 years of age with over 24-h intensive care unit (ICU) stay |

| Warwick et al. (2019) | Immediate physical therapy was defined as patients undergoing Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) that receive physical therapy within eight hours of surgery based on the standard of care at the researcher's institution | No information | 2051 primary total joint arthroplasty procedures that were performed at the researcher's institution from July 2015 to December 2017, where 226 received delayed physical therapy. Then 226 delayed physical therapy were matched based on demographic and preoperative variables to a group of patients who received immediate PT. |

| Flikweert, et al. (2018) | No information | No information | 479 patients aged more than or equal to 60 that being treated for a hip fracture |

| Deng et al. (2018) | No information | No information | 16,699 patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty that met the inclusion criteria: (1) human patient undergoing hip joint replacement, knee joint replacement and spinal surgery for general osteoarthritis |

| Sattler, Hing, & Vertullo (2020) | Early mobilization as ambulation 4–8 h following total knee replacement. | No explanation | No explanation |

| Rutenberg, et al. (2020) | There is no definition of early mobilization, but it was explained that it was initiated after the surgery focusing on the range of motion, gait, and balance. | No explanation | 851 patients 65 years and older, who were treated operatively following fragility hip fractures between 01.2011 and 06.2016 |

| Chua et al. (2020) | No definition of early mobilization. It was explained that successful mobilization was defined as standing and marching on the spot and/or walking forward. Transfers from bed-to-chair were not considered mobilization. | No explanation | 521 patients undergoing primary total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty |

| Baer et al. (2019) | Early mobilization was defined as the first mobilization of the patient within 24 h after surgery and late mobilization after 24 h. | The surgeon determined the postoperative level of weight bearing. The actual weight bearing formed by the patient was used as the postoperative level of weight bearing, either with full or partial weight bearing. | 219 patients aged 70 years or older were treated with surgery after a hip fracture. |

| Aprato et al. (2020) | No explanation | All patients were allowed to full weight bearing after surgery | 516 patients aged older than 65 years old who were admitted at the level I trauma center with proximal femoral fracture during a 1-year period |

| Consigliere et al. (2019) | No explanation |

|

70 patients treated for distal femoral fracture at the level I major trauma center |

| Warren et al. (2019) | No explanation | Weight-bearing as tolerated on postoperative day one (partial weight-bearing, touch-down weight-bearing) and those that did not/non-weight bearing tolerated (patient who did not weight bear as tolerated) | 7947 patients who underwent cephalomedullary nail, sliding hip screw, and hip hemiarthroplasty and internal fixation using the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) |

| Gautreau et al. (2020) | No explanation | No explanation | Patients who had an elective unilateral primary total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty between June 2015 and March 2017 |

Discussion

In this study, the effect of early mobilization on hip fracture and lower extremity postoperative was summarized and discussed orderly starting from the most often investigated and reported.

Shorter the LOS

The LOS of patients with total knee arthroplasty (TKA) that undergo early mobilization is shorter than patients who did not undergo early mobilization (10 days versus 12 days) (Lei et al., 2021). Then, early mobilization of femur postoperative patients also showed an acceleration of the LOS (Consigliere et al., 2019). However, Warwick et al. (2019) reported that postoperative LOS in their study was shorter overall in immediate and delayed physical therapy. The median of postoperative LOS in their study was two days for both immediate and delayed physical therapy groups. Chua et al. (2020) reported that the introduction of early mobilization protocol is associated with a modest reduction in LOS at a high-volume hospital while accounting for factors such as increasing obesity, increasing age, and language barrier. An important point was discussed by Sattler et al. (2020) that although reducing LOS has been shown to improve functional recovery and enable a more rapid return to independent living of patients with total knee replacement, it may result in increased hospital readmissions. In their report, Warwick et al. (2019) suggested that the shorter LOS compared to previous studies may be caused by institutional differences and the continuing trend toward accelerated perioperative care and earlier discharge. Gautreau et al. (2020) concluded that the greater the distance patients mobilized on postoperative day 0 (POD0), the shorter their LOS.

Lower Postoperative Complications

The type of postoperative complications identified in the current study include delirium, pulmonary infection, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pneumonia, atelectasis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), sepsis, myocardial infarction and stroke, wound infection, pressure sore, transfusion, C. diff infection, deep incisional surgical site infection, unplanned reintubation, and cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation (Baer et al., 2019; Haslam-Larmer et al., 2021; Kenyon-Smith et al., 2019; Lei et al., 2021; Sattler et al., 2020; Warren et al., 2019). Patients who develop postoperative delirium have a 2.3 times chance of developing other complications. Early mobilization and delirium are interrelated. Early mobilization can reduce the complications of delirium, and delirium can also reduce the chance of the patients undergoing early mobilization (Kenyon-Smith et al., 2019). The incidence of pneumonia can be reduced because early mobilization can effectively improve the strength and function of the respiratory muscles (Richtrmoc et al., 2020). The incidence of DVT is lower in patients undergoing early mobilization compared to patients who did not undergo early mobilization (0.71% versus 1.41%) (Ascione et al., 2020; Lei et al., 2021). However, the effect of early ambulation on thrombogenesis after TKA is still inconclusive in the Chinese population (Lei et al., 2021). Early mobilization can prevent urinary retention, thereby reducing the incidence of UTIs (Sattler et al., 2020). The incidence of wound dehiscence is lower in TKA patients who undergo early mobilization (0.22%) compared to TKA patients who do not undergo early mobilization (0.35%) (Lei et al., 2021). The occurrence of postoperative pressure ulcer of hip fracture will slow down the recovery process and become a predictor of patient mortality (Morri et al., 2019). Early mobilization may reduce the risk of pressure ulcers by increasing the vascular circulation (Koukourikos et al., 2020). Among patients treated with sliding hip screw, weight bearing as tolerated on postoperative day one (POD1) status was associated with a significantly reduced risk of major complication (Warren et al., 2019).

Lower the Pain

Lei et al. (2021) used visual analog scale (VAS) to measure the severity of pain experienced by the patient with knee osteoarthritis who had undergone TKA at 24 large teaching hospitals in China. In their study, early ambulation was defined as any partial or full weight-bearing activities (walking on the spot, bed-to-chair, or bed-to-toilet) under the supervision of a physiotherapist within 24 h postoperatively. Patients who did early mobilization had a significantly lower VAS score at 72 h after surgery than those who did not. Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) postoperative patients who undergo early mobilization have better pain control than patients who do not undergo early mobilization (13) (Warwick et al., 2019). In their study, Warwick et al. (2019) defined immediate physical therapy as being delivered within 8-h time period following the operation. Early mobilization can be an intervention for pain management in femur postoperative patients (Aprato et al., 2020). Gautreau et al. (2020) recommended identifying and managing impediments to early mobilization and discharge, such as pain/stiffness, in support of the well-patient model.

Increase Walking Ability

Rapid functional recovery from TKA may be related to postoperative rehabilitation because it can effectively reduce swelling, improve ROM, and decrease postoperative pain (Chua et al., 2020). A study reported by Kuru and Olcar (2020) found that 69.6% of the patients with early weight-bearing could walk with a cane, while 62.1% of the patients with late weight-bearing could walk only with crutches or walking frame. They defined early mobilization as the first mobilization of the patient within 24 h after surgery. Early mobilization may increase muscle strength, prevent neuromuscular weakness, avoid loss of muscle mass, thus improving limb function and ability to walk (Koukourikos et al., 2020).

Increase the Quality of Life

Early mobilization has an effect on increasing the quality of life. Lei et al. (2020) used Short Form Survey (SF-12) to measure the quality of life. The higher postoperative score SF-score in early ambulation than those in the late ambulation group indicates that this active intervention could achieve a quick return to independence in daily activities, which might comprehensively reflect all the functional beneficial effects of the early ambulation regimen in their study.

Decrease the Rate of Readmission

The 30-day readmission rate is lower in TJA postoperative patients who undergo early mobilization than those who are not. Readmission occurred in 3.1% of patients who undergo early mobilization and 7.6% of patients who do not undergo early mobilization (Warwick et al., 2019). Early mobilization can prevent complications and improve quality of life, thereby reducing readmission (Flikweert et al., 2018; Rutenberg et al., 2020).

Decrease Mortality Rate

In-hospital mortality rate was reported at 7.3% in a study of patients with femoral neck fractures after total hip arthroplasty (Baer et al., 2019). Early ambulation, defined as the first mobilization of the patient within 24 h after surgery, was associated with less complication and therefore related to lower mortality. Aprato et al. (2020) recommended that early surgery and early mobilization be performed to decrease the mortality rate at 6 and 12 months after femure fracture. In their study, Aprato et al. (2020) define early surgery as within 48 h surgical treatment and early mobilization defined as within 24 h after surgery. All patients were allowed to have full weight bearing after surgery. Warren et al. (2019) concluded that weight-bearing after surgical care of hip fracture seems to decrease morbidity and mortality, but it is highly dependent on the treatment.

Lower the Total Hospitalization Cost

The increase in the cost of hospitalization is largely determined by the lengthening of the patient's LOS after femoral fracture surgery (Sermon et al., 2018). The benefit of early mobilization in reduced LOS was in line with the achievement of the reduction of hospitalization cost of nearly ¥4000 (equal to USD 596,40) (Lei et al., 2021).

Higher Number of Physical Therapy Sessions Prior to Discharge

Patients who receive immediate physical therapy (PT) following TJA had a higher number of PT sessions prior to discharge compared to those in delayed PT (Warwick et al., 2019). In their study, Warwick et al. (2019) defined immediate PT as being delivered within the 8-h time period following the operation. Patients are encouraged to get out of bed and ambulate during the first visit, but each therapy session is tailored to an individual patient's needs and abilities. It ranges from bed exercise to walking stairs. Conditions of patients who have risk factors for not receiving immediate PT were later operative end time, logistical factors, patient-level factors, and type of anesthesia. Those conditions may contribute to the lower number of PT sessions prior to discharge.

Increase in Satisfaction

Sattler et al. (2020) cited a study by Cox et al. (2016), who reported that 82% of patients with primary hip and knee arthroplasty surgery were very satisfied with early mobilization. In their study, early mobilization was applied by a collaborative team that focused on mobility continued throughout the duration of the patients’ admission where each member of the healthcare team (nurse, physiotherapy, doctor) participated in increasing the frequency of mobility by providing gait training twice a day, ambulating patients to the bathroom and performing activity daily livings. Lei et al. (2021) mentioned that ROM and content pain control are important factors for patient satisfaction after TKA.

No Fracture Displacement or Implant Failure

In this current study, no fracture displacement or implant failure was reported as the effect of early mobilization, as reported by Consigliere et al. (2019). In their study, respondents were divided into two groups: DWB and early weight-bearing (EWB). Patients in the EWB group reported having no fracture displacement or implant failure. Bone reacts to external mechanical stimuli such as loading and weight bearing. When a fracture occurs, the bone physiologically reacts to the stimuli improving its potential to heal. Implant failure may lead to fracture-healing delay and non-union.

The findings of the current study are consistent with published data in this field that show early mobilization to be one of the interventions that can reduce complications and indicate that early mobilization is a safe technique in helping to reduce the postoperative LOS, readmission and in turn, financial costs.

Early mobilization was found to have many benefits for the patients, but the current study found that the definition of early mobilization was still inconsistent. This may be caused by the different guidelines that are applied in each study location, for example, as reported by Lei et al. (2021) and Warwick et al. (2019). There were seven studies that did not provide sufficient information about how they define early mobilization. Different definitions may lead to different interpretations of the effect of early mobilization. Further study is recommended to clarify it.

In the current study, the weight-bearing scheme was evaluated. It was found that 10 out of 16 studies did not report weight bearing specifically. Studies reported different findings related to the relationship between LOS in hospitals according to full and partial weight bearing may be resulted from fracture type included and patient-specific factors (Kuru & Olcar, 2020). In the current study, elderly patients were included in eight studies. A previous study by Gautreau et al. (2020) reported that age was a significant predictor of mobilization and recommended further research to explore how age relates to that outcome. Finally, although there were different definitions of early ambulation, all studies reported that early ambulation is relatively safe. For example, a study by Chua et al. (2020) suggested that among 2,687 patients who ambulated within 24 h after TKA, the occurrence of falls, dislocations, nerve damage, and wound dehiscence, and the risk was low, and it was not different between the two groups based on the timing of first ambulation. A study by Baer et al. (2019) reported that at least early mobilization and full-weight bearing did not increase the level of pain. Furthermore, the collaboration among healthcare providers in caring for patients with hip and lower extremity fractures was explained in the studies. An interdisciplinary pathway in hip-fractured elderly patients is recommended because it could reduce in-hospital mortality, improve functional recovery, and increase the probability of living along at home, for 6 months (Bano et al., 2020).

Limitations of the Study

The limitation of the current study was that the articles included in the review were only studies published in English. One study included in the review did not specifically analyze fracture patients, so the findings were limited to be discussed in this review. Other limitations included the different research design types, the wide age range of the respondents, and different definitions of early mobilization and weight-bearing schemes. The research location was mostly in European countries.

Implications for Practice

Nurses need to apply early mobilization by paying attention to the patient's hemodynamic condition. In addition, nurses also need to prepare patients from the preoperative stage, for example by training muscle strength so that the patient is ready and can apply it after the operation is performed.

Conclusions

The incidence of complications after hip and lower extremities surgery is still quite high, leading to prolonged LOS, increased morbidity and mortality, increased unplanned readmissions, and increased hospitalization costs. These complications and unwanted events can be prevented by programmed early mobilization. Various research articles showed that early mobilization is safe and effective for postoperative patients. Nurses and health providers involved in caring for patients need to equip themselves with the knowledge and ability to provide early mobilization for postoperative patients safely and effectively. Nurses and health providers also need to motivate patients to cooperate in undergoing early mobilization to optimize the benefits of early mobilization to prevent complications and improve recovery. Further study is needed to clarify the definition of early mobilization and weight-bearing scheme and to confirm the effect of early mobilization among different patients’ characteristics, such as age and Asian patients.

Acknowledgment

The author(s) would like to thank the Rector of Respati University, Indonesia for his support to our study in Doctoral Program.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Elsi Dwi Hapsari https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8031-5111

References

- Aprato A., Bechis M., Buzzone M., Bistolfi A., Daghino W., Massè A. (2020). No rest for elderly femur fracture patients: Early surgery and early ambulation decrease mortality. Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 21, 12. 10.1186/s10195-020-00550-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascione F., Braile A., Romano A. M., di Giunta A., Masciangelo M., Senorsky E. H., Samuelsson K., Marzano N. (2020). Experience-optimised fast track improves outcomes and decreases complications in total knee arthroplasty. The Knee, 27(2), 500–508. 10.1016/j.knee.2019.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer M., Neuhaus V., Pape H. C., Ciritsis B. (2019). Influence of mobilization and weight bearing on in-hospital outcome in geriatric patients with hip fractures. SICOT J, 5(1), 4. 10.1051/sicotj/2019005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bano G., Dianin M., Biz C., Bedogni M., Alessi A., Bordignon A., Bizzotto M., Berizzi A., Ruggieri P., Manzato E., Sergi G. (2020). Efficacy of an interdisciplinary pathway in a first level trauma center orthopaedic unit: A prospective study of a cohort of elderly patients with hip fractures. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 86, 103957. 10.1016/j.archger.2019.103957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros C. E. S. R., Lima A. M. S., Vilaça A. F., Correia R. F., Gonçalves T. F., Silva R. M. O., Cardozo S. M., Rattes C. F. S., Souza H. C. M., Brandão D. C., Dornelas A. F. A., Campos S. L. (2015). Impact of standardized mobilization in mechanically ventilated patients on respiratory muscular strength. European Respiratory Journal, 46: PA2171. [Google Scholar]

- Biz C., Fantoni I., Crepaldi N., Zonta F., Buffon L., Corradin M., Lissandron A., Ruggieri P. (2019). Clinical practice and nursing management of pre-operative skin or skeletal traction for hip fractures in elderly patients: A cross-sectional three-institution study. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing, 32, 32–40. 10.1016/j.ijotn.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biz C., Tagliapietra J., Zonta F., Belluzzi E., Bragazzi N. L., Ruggieri P. (2020). Predictors of early failure of the cannulated screw system in patients, 65 years and older, with non-displaced femoral neck fractures. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 505–513. 10.1007/s40520-019-01394-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua H., Brady B., Farrugia M., Pavlovic N., Ogul S., Hackett D., Farag D., Wan A., Adie S., Gray L., Nazar M., Xuan W., Walker R. M., Harris I. A., Naylor J. M. (2020). Implementing early mobilisation after knee or hip arthroplasty to reduce length of stay: A quality improvement study with embedded qualitative component. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 21(1), 1–14. 10.1186/s12891-020-03780-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consigliere P., Iliopoulos E., Ads T., Trompeter A. (2019). Early versus delayed weight bearing after surgical fixation of distal femur fractures: A non-randomized comparative study. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology, 29(8), 1789–1794. 10.1007/s00590-019-02486-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J., Cormack C., Prendergast M., Celestino H., Willis S., Witteveen M. (2016). Patient and provider experience with a new model of care for primary hip and knee arthroplasties. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing, 20, 13–27. 10.1016/j.ijotn.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q. F., Gu H. Y., Peng W. Y., Zhang Q., Huang Z. D., Zhang C., Yu Y. X. (2018). Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery on postoperative recovery after joint arthroplasty: Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 94(1118), 678–693. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2018-136166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flikweert E. R., Wendt K. W., Diercks R. L., Izaks G. J., Landsheer D., Stevens M., Reininga I. H. F. (2018). Complications after hip fracture surgery: Are they preventable? European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery: Official Publication of the European Trauma Society, 44(4), 573–580. 10.1007/s00068-017-0826-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautreau S., Haley R., Gould O. N., Canales D. D., Mann T., Forsythe M. E. (2020). Predictors of farther mobilization on day of surgery and shorter length of stay after total joint arthroplasty. Canadian Journal of Surgery, 63(6), E509–E516. 10.1503/cjs.003919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam-Larmer L., Donnelly C., Auais M., Woo K., DePaul V. (2021). Early mobility after fragility hip fracture: A mixed methods embedded case study. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 1–15. 10.1186/s12877-021-02083-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennison T., Yarlagadda R. (2019). A case series of patients change in mobility following a hip fracture. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology, 29(1), 87–90. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2018-136166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannegaard P. N., van der Mark S., Eiken P., Abrahamsen B. (2010). Excess mortality in men compared with women following a hip fracture. National analysis of comedications, comorbidity and survival. Age and Ageing, 39(2), 203–209. 10.1093/ageing/afp221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon-Smith T., Nguyen E., Oberai T., Jarsma R. (2019). Early mobilization post-hip fracture surgery. Geriatric Orthopaedic Surgery & Rehabilitation, 10, 1–16. 10.1177/2151459319826431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukourikos K., Lambrini K., Christos I., Vassiliki D., Vassiliki K., Areti T. (2020). Early mobilization of intensive care unit ((ICU) patients. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 13(3), 2269–2277. [Google Scholar]

- Kuru T., Olcar H. A. (2020). Effects of early mobilization and weight bearing on postoperative walking ability and pain in geriatric patients operated due to hip fracture: A retrospective analysis. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences, 50(1), 117–125. 10.3906/sag-1906-57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y. T., Xie J. W., Huang Q., Huang W., Pei F. X. (2021). Benefits of early ambulation within 24 h after total knee arthroplasty: A multicenter retrospective cohort study in China. Military Medical Research, 8(1), 1–8. 10.1186/s40779-020-00296-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morri M., Ambrosi E., Chiari P., Magli A. O., Gazineo D., D’Alessandro F., Forni C. (2019). One-year mortality after hip fracture surgery and prognostic factors: A prospective cohort study. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 18718. 10.1038/s41598-019-55196-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris P. E., Goad A., Thompson C., Taylor K., Harry B., Passmore L., Ross A., Anderson L., Baker S., Sanchez M., Penley L., Howard A., Dixon L., Leach S., Small R., Hite R. D., Haponik E. (2008). Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Critical Care Medicine, 36(8): 2238–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richtrmoc M. K., Leite S. W., Azevedo A. M., Correia R. F., Lins R. A. C., Lima W. A., Morais C. C. A., Pereira R. R., Bandeira M., Barros CE,S,R, de Lima A. M. S., Rodgrigues-Machado M. G., Brandao D. C., Andrade A. D. D., de Aguiar M. I. R., Campos S. L. (2020). Effect of early mobilization on respiratory and limb muscle strength and functionality of nonintubated patients in critical care: A feasibility trial. Critical Care Research and Practice, 2020, 1–9. 10.1155/2020/3526730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutenberg T. F., Rutenberg R., Vitenberg M., Cohen N., Beloosesky Y., Velkes S. (2020). Prediction of readmissions in the first postoperative year following hip fracture surgery. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery: Official Publication of the European Trauma Society, 46(5), 939–946. 10.1007/s00068-018-0997-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler L., Hing W., Vertullo C. (2020). Changes to rehabilitation after total knee replacement. Aust J Gen Pract, 49(9), 587–591. 10.31128/AJGP-03-20-5297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sermon A., Rochus I., Smeets B., Metsemakers W. J., Misselyn D., Nijs S., Hoekstra H. (2018). The implementation of a clinical pathway enhancing early surgery for geriatric hip fractures: How to maintain a success story? European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery, 45(2), 199–205. 10.1007/s00068-018-1034-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Zhang G., Liang J., Bai C., Dang X., Wang K., He C., Liu R. (2020). Effects of delayed hip replacement on postoperative hip function and quality of life in elderly patients with femoral neck fracture. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 21, 487. 10.1186/s12891-020-03521-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenøy S., Watne L. O., Hestnes I., Westberg M., Madsen J. E., Frihagen F. (2020). Results after introduction of a hip fracture care pathway: Comparison with usual care. Acta Orthopaedica, 91(2), 139–145. 10.1080/17453674.2019.1710804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren J., Sundaram K., Anis H., McLaughlin J., Patterson B., Higuera C. A., Piuzzi N. S. (2019). The association between weight-bearing status and early complications in hip fractures. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology, 29(7), 1419–1427. 10.1007/s00590-019-02453-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warwick H., George A., Howell C., Green C., Seyler T. M., Jiranek W. A. (2019). Immediate physical therapy following total joint arthroplasty: Barriers and impact on short-term outcomes. Advances in Orthopedics, 2019, 6051476. 10.1155/2019/6051476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]