Abstract

RNA splicing is a biological process to generate mature mRNA (mRNA) by removing introns and annexing exons in the nascent RNA transcript and is executed by a multiprotein complex called spliceosome. To aid RNA splicing, a class of splicing factors use an atypical RNA recognition domain (UHM) to bind with U2AF ligand motifs (ULMs) in proteins to form modules that recognize splice sites and splicing regulatory elements on mRNA. Mutations of UHM containing splicing factors have been found frequently in myeloid neoplasms. To profile the selectivity of UHMs for inhibitor development, we established binding assays to measure the binding activities between UHM domains and ULM peptides and a set of small-molecule inhibitors. Additionally, we computationally analyzed the targeting potential of the UHM domains by small-molecule inhibitors. Our study provided the binding assessment of UHM domains to diverse ligands that may guide development of selective UHM domain inhibitors in the future.

Keywords: U2AF homology motif, RNA binding protein, splicing factor, binding site analysis, homogenous time resolved fluorescence assay, small-molecule inhibitors

Gene transcription is a biological process in which the protein coding DNA sequences are transcribed into mRNA (mRNA). mRNAs are then translated to make functional proteins. During transcription, the sequences of intronic and exonic segments in DNA are transcribed in the nascent RNA transcripts called the precursor RNA (pre-mRNA). To obtain mature mRNA for protein synthesis, the pre-mRNA is processed by a multiprotein complex, spliceosome, to remove introns and annex exons. Selective inclusion and exclusion of exons in the RNA splicing, mediated via regulated splicing mechanisms,1 increase protein diversity in human than mice despite both species having the same genome size.1 For examples, >95% of human genes are alternatively spliced in comparison with ∼63% in mice, giving humans five time or greater gene products per gene according to the ENCODE humane gene set (v24) database.2 Different alternatively spliced mRNAs are found in tissues specifically3,4 and are important in biological development.5 Although encoded from the same gene, some protein isoforms, translated from the alternatively spliced mRNAs, possess very different functions. An example is that BCL2-like 1 gene encodes Bcl-xL and Bcl-xS proteins yielding opposing anti- and pro-apoptotic functions, respectively.6 Maintenance of RNA splicing programs in different cells and tissues is critical to cellular development and homeostasis to sustain life.

Alteration in RNA splicing can be induced by genetic mutations in splicing regulators that alter composition of protein isoforms in cells to cause diseases.7 Studies of whole-exome and targeted sequencing of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) patients’ samples8−10 have uncovered a set of frequently mutated genes encoding RNA splicing factors including SF3B1, U2AF1, SRSF2, ZRSR2, and LUC7L2,8,11−13 that change expression patterns of protein isoforms. Following this early discovery in MDS, mutations of splicing factors were later identified in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), melanoma, glioma, breast, lung, bladder, and pancreatic cancers.14,15 Prognostic values of the splicing factor mutations in myeloid malignancies are, however, context dependent.16 The most frequent SF3B1 mutations are associated with good prognosis in MDS17 but give poor outcome prognosis in CLL.18U2AF1 mutations19 generally deliver adverse prognosis,16,17 whereas less frequent SRSF2 mutations commonly co-occur with other nonsplicing gene mutations to give reduced overall survival in MDS.16

Among the splicing factors mutations, U2AF1 mutations occur in early MDS clones. Adult MDS patients, harboring U2AF1 mutations, have increased risk of progression to leukemia.9,20,21 Functionally, U2AF1 forms a heterodimer with U2AF2 to recruit U2snRNP to the 3′ splice site (3SS) in pre-mRNA processing.22,23 The frequently found mutations of S34 and Q157 in U2AF1 are located in the RNA recognition domain and alter the mRNA recognition preferences by U2AF1.8,9,24 On the other hand, overexpression of wild-type U2AF1 (U2AF1wt) failed to rescue the defective hematopoiesis caused by mutant U2AF1 (U2AF1mut),25,26 suggesting the gain of new (neomorphic) function by U2AF1mut. Studies also showed that the altered splicing activities of U2AF1S34F promoted oncogenic transformation of MDS and AML by decreasing ATG7 levels, leading to defective autophagy,27 and produced the IRAK4-L isoform to activate pro-survival NF-κB signaling.28 In vivo studies showed that U2AF1S34F hematopoietic cells and transgenic mouse models were sensitive to treatment of sudemycin (a SF3B1 modulator)29 implying the susceptibilities of U2AF1mut cells to splicing therapeutics. A recent study of mouse models further supported that U2AF1wt is a haplo-essential gene to sustain the viability of U2AF1mut cells.30

Clinical data suggest U2AF1 can be an attractive target for treating cancer patients harboring U2AF1 mutations. However, a recent study was unsuccessful to discover compounds directly targeting the mutations site in U2AF1.31 Because U2AF1 binds with U2AF2 to form a functional unit to recognize the 3SS in pre-mRNA, identifying compounds blocking U2AF1 and U2AF2 binding may be an attractive strategy. Heterodimerization of U2AF1 and U2AF2 is mediated primarily via UHM in U2AF1 and ULM in U2AF2. The UHM domain is an atypical RNA Recognition Motif (RRM)32 that engages in protein–protein interaction instead of binding to RNA. Currently, seven proteins were known to contain UHM including U2AF1, RBM39, RBM23 (an isoform of RBM39), U2AF2, PUF60, SPF45 (RBM17) and Tat-SF1 (Figure 1). ULM is a motif that contains up to 28 amino acids (in U2AF2) and dose not adopt a well-formed protein fold. Proteins containing ULM include U2AF2, SF1, SF3B1 (five ULMs), ATXN1,33 and a recently identified Rev HIV-134 (Figure 1). Previous studies have reported the binding activities between different UHM domains and the ULM peptides.32 Briefly, SF1-ULM has higher binding affinity to U2AF2-UHM and is >100-fold weaker to U2AF1-UHM. SF3b1-ULM5 is most potent in binding to SPF45-UHM and PUF60-UHM, but >150-fold weaker against U2AF1-UHM. Prior studies from different groups used different ULM peptide sequences to study their binding affinities to different proteins based on different biochemical assays. The binding activities data between the UHM domains and the ULM peptides obtained from different research groups may not be compared directly. Furthermore, no extensive data regarding the selectivity of small-molecule inhibitors against these UHM domains have been reported. This can be attributed to few inhibitors being reported to date. To characterize the selectivity between UHMs and ULMs and compounds using the same ligands in the same assay condition, we profiled the binding activities between four UHM proteins (U2AF1, RBM39, SPF45, and PUF60) and five ULM peptides (SF1, SF3b1, U2AF2, Rev HIV-1, and ATXN1) using biochemical assays and performed computational binding site analysis of the UHM domains followed by docking calculations to study the interaction of the inhibitors with the UHM domain proteins. The ULM peptides from SF1, SF3b1 and U2AF2 were well-known motifs that bound more potently to the four UHM domains. In addition to the ULMs from splicing factors, we included a recently discovered ULM in Rev HIV-1 and a less well-characterized ULM in ATXN1. Small-molecule inhibitors targeting the UHM domains have recently been reported.35−37 We synthesized seven analogous compounds based on the tryptophan scaffold and characterized the selectivity of these inhibitors against different UHM domains.

Figure 1.

Summary of functional domains in ULM and UHM containing human proteins. Abbreviations: UHM, U2AF homology motif; ULM, U2AF ligand motif; Znf, zinc finger domain; RS, arginine/serine-rich domain; RRM, RNA recognition motif; G-patch, G-patch domain; Coil–Coil, coil–coil domain; KH-QUA2, K-homology/quaking 2 domain; Pro-Rich, proline-rich domain; HEAT repeats, Huntingtin, elongation factor 3, protein phosphatase 2A, and the yeast kinase TOR1 repeats; AXH, ataxin domain; MRS, methionyl-tRNA synthetase; Q, poly(Q) domain.

To profile the selectivity between the UHM domains and the ULM peptides, we first developed the biochemical binding assay between the UHM domains and the ULM peptides using a homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF) assay. All four UHM domains were fused with a His-tag followed by either a GST or Thioredoxin at the N-terminus. The N-terminus biotin conjugated ULM from either U2AF2 or SF3b1-ULM5 was used as the reference peptide in the assay development (see the Supporting Information for sequences). Anti-His-tag (histidine-tag) donors were used to bind with the His-tag in the UHM domains and the streptavidin coupled acceptors were used for the ULM peptides in our HTRF assay development. For U2AF1-UHM, we used biotinylated U2AF2 peptide. For all other UHM domains, we used the biotinylated SF3b1-ULM5 peptide. We varied the proteins and the peptides concentrations to identify the condition that gave the optimal energy transfer signals in the HTRF assay.

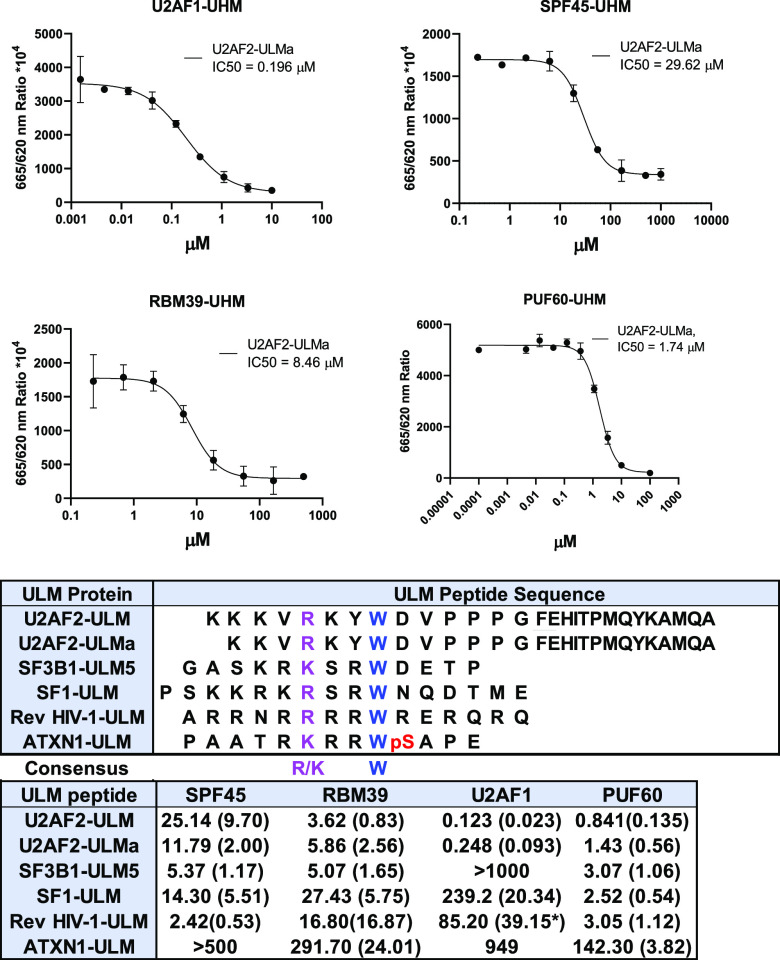

Using the HTRF assay, we measured the binding affinities of six ULM peptides, from all four ULM containing proteins (Figure 1), with four UHM domains based on the values of inhibition constants (IC50) to the reference peptides. The sequence alignment of the ULM peptides showed the consensus of one basic amino acid (R/K) followed by a conserved Trp separated by two amino acids (Figure 2). The diversity of the ULM peptide sequences allowed us to profile their binding selectivity with the four UHM domains. We found that U2AF2-ULM has an IC50 of 0.123 μM to U2AF1-UHM. U2AF2-ULM has a > 6-fold selectivity between U2AF1-UHM and three other UHM domains. The IC50 values between SF3b1-ULM5 to SPF45-UHM, RBM39-UHM and PUF60-UHM were 5.37, 5.07, and 3.07 μM, respectively, but had no binding activity to U2AF1-UHM. Both SF1-ULM and Rev HIV-1-ULM are more selective to SPF45-UHM (SF1-ULM is more selective to PUF60-UHM), whereas ATXN-1-ULM has a weak binding affinity to three UHM domains except PUF-UHM at 142.30 μM. In terms of the selectivity of the UHM domains, SPF45-UHM has the highest affinity to Rev HIV-1-ULM, whereas RBM39-UHM has a similar higher affinity to U2AF2-ULM and SF3b1-ULM5. U2AF1-UHM had a greater than 690-fold selectivity between U2AF2-ULM and four other ULM peptides. The enhanced affinity of U2AF2-ULM to U2AF1-UHM is contributed from the C-terminal amino acids in the U2AF2-ULM peptide (discussed later). Interestingly, PUF60-UHM had a similar affinity to these ULM peptides except ATXN1-ULM.

Figure 2.

Binding affinities of ULM domain peptides to UHM domains in SPF45, RBM39, U2AF1, and PUF60. IC50 values (in μM) are determined by at least two independent measurements. Standard deviations are shown in the parentheses. Each experiment is performed in duplicate. pS: phosphorylated serine. Sequence numbers of the ULM peptides: U2AF2-ULM (85–112), U2AF2-ULMa (86–112), SF3B1-ULM5 (330–341), SF1-ULM (13–28), Rev HIV-1-ULM (37–49), and ATXN1-ULM (766–788). Amino acids with conservation and similar physicochemical properties in the ULM peptides are colored in blue and pink, respectively. pS: phosphorylated Ser.

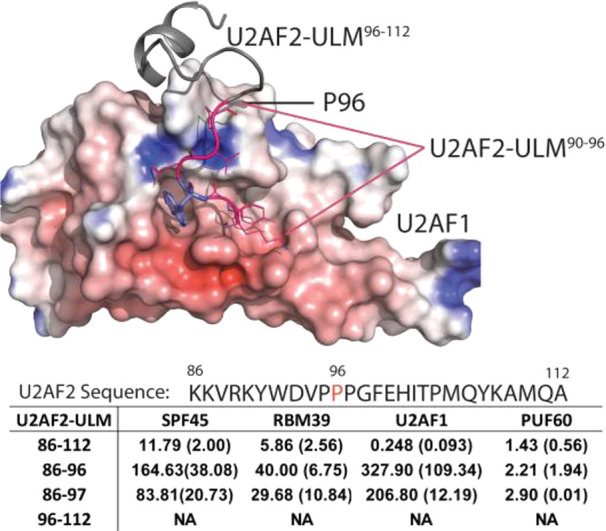

All the ULM peptides contained a conserved Trp to recognize a small hydrophobic pocket in the UHM domains (Figures 3 and 4).32 The crystal structure between U2AF1-UHM and U2AF2-ULM38 also revealed that U2AF2-ULM adopts a loop-helix conformation (Figure 3). The loop segment of U2AF2-ULM (containing the conserved W92) binds to a well-defined pocket in U2AF1-UHM and the helix binds to a shallow groove in U2AF1-UHM (Figure 3). W92A mutation of U2AF2-ULM significantly reduced the association between U2AF1 and U2AF2.38 In addition, a triplet of proline (Pro-95–97) pivoted the helix segment of U2AF2-ULM and interacted with a shallow groove in U2AF1-UHM. Although mutation of P96G reduced the binding between U2AF1 and U2AF2, the decreased binding affinity is much less than that between U2AF1 and U2AF2W92A-ULM. To dissect the binding affinities of the loop and the helix segment in U2AF2-ULM with the UHM domains, we determined the IC50 values of three U2AF2-ULM peptides, including sequences: 86–96, 86–97, and 96–112 (Figure 3), and the four UHM domains. We found that the helix peptide (sequence: 96–112) yielded no binding affinity to all four UHM domains (Figure 3). Both loop peptides (sequence: 86–96, 86–97) had similar IC50 values (differing by 2-fold) to all four UHM domains. An 833-fold reduction of IC50 values between U2AF2-ULM/86–112 and U2AF2-ULM/86–97 with U2AF1-UHM was found. For RBM39-UHM and SPF45-UHM, much less reduction by 5–8-fold in the IC50 values was found between U2AF2-ULM/86–112 and U2AF2-ULM/86–97. The data suggested that the pivoting poly-Pro in U2AF2-ULM/86–11238 indeed facilitated the enhanced binding affinity between the helix of U2AF2-ULM/96–112 and the groove in U2AF1-UHM. The synergistic enhanced interaction of the helix with the loop segment in U2AF2-ULM/86–112 with SPF45-UHM, RBM39-UHM, and PUF60-UHM was much less pronounced (Figure 3), suggesting the helix in U2AF2-ULM/96–112 may not lock in position in these UHM domains. Whether the differences impact the positioning of the domains following U2AF2-ULM/86–112 with these UHM domains and thus the interactions with other proteins regulating splicing remains to be determined.

Figure 3.

Binding affinities of the helical and the loop segment of the ULM-U2AF2 peptide to UHM domains in SPF45, RBM39, U2AF1, and PUF60. The helical and the loop segment of ULM-U2AF2 correspond to sequence number 86–96/97 and 96–112, respectively. IC50 values in μM are determined by at least two independent measurements. Standard deviations are shown in the parentheses. Each experiment is performed in duplicate. NA: no activity.

Figure 4.

(A–E) Computational analysis of the conserved Trp binding sites in five UHM domains using Sitemap. The Trp (green) binding location is circled and the binding ligands (peptides or inhibitor) are also displayed. Maps of the physicochemical properties in the binding sites of the representative SPF45-, RBM39-, PUF60-, U2AF1-, and U2AF2-UHM are shown in the lower panel in A–E. Blue, red, and yellow colors correspond to regions favorable to positively charged, negatively charged, and hydrophobic functional groups from ligands. (F) Dscore and the sizes of the binding site regions suitable for small-molecule binding. Red dashed line corresponds to Dscore = 0.83. The purple dots represent the data analyzed from the unbound ligand structures. U2AF1SP is the yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) U2AF1 ortholog.

The conserved Trp binding site in the UHM domains has been previously characterized as the key binding sites for the ULM peptides.32 To investigate the potential of the Trp binding site for small-molecule inhibitors development, we analyzed the four UHM domains and U2AF2-UHM (Figure 4A–E) using the computational Sitemap program.39 The Sitemap program has been used to analyze the protein binding sites for assessing the potential of developing small-molecule inhibitors for protein targets. In our analysis, we only included crystal structures of the UHM domains bound to either peptides or small molecules (Supporting Information). An overview of the electrostatic potential maps of the UHM domains indicated that the region below the Trp binding site was primarily negatively charged (Figure 4). We also found that the potential small-molecule binding locations were confined to the Trp binding site in SPF45-UHM, PUF60-UHM, RBM39-UHM, and U2AF2-UHM (Figure 4). In contrast, U2AF1-UHM contained two contiguous pockets including the Trp binding site and a nearby well-defined pocket to the right (Figure 4D). A mixed preference of negatively (shapes in red color) and positively (shapes in blue color) charged functional groups from inhibitors was identified on top of the Trp binding site, whereas the positively charged group was preferred at the region below the Trp binding site (Figure 4A–E). Dscore has been used as the scoring function to assess the overall likelihood of developing small-molecule inhibitors to the targeted binding sites. A binding site giving a Dscore >0.83 was inferred as being attractive for small-molecule inhibitor development.39 The Trp binding sites in these UHM domains gave Dscore values close to 0.83 implying they were attractive for small molecule inhibitor development. Further, the sizes of the binding sites in PUF60-UHM and U2AF1-UHM were relatively larger than other UHM domains. The cocrystal structure of PUF60-UHM and an inhibitor has been determined and suggested that the binding site is flexible and can adapt to a phenothiazine group (Figure 4C) larger than an indole group.35 The binding site analysis suggested the UHM domains are attractive targets for inhibitor development.

Previously, a macrocyclic peptide derived from the ULM peptide was reported to have a KD value of 0.18 μM to SPF45-UHM.40 To date, the most potent small-molecule inhibitor to target the UHM domains reported was cmp9 that had IC50 values of ∼7 μM to SPF45-UHM, PUF6-UHM, and U2AF2-UHM.35 Another study by Hanzawa et al.36 identified a PUF60-UHM inhibitor, DS89092425, and reported that a terminal amine group in DS89092425 contributed importantly to the binding affinity. Recently, Kobayashi et al. combined virtual screening and in vitro assays to discover an indole containing small-molecule inhibitor (UHMCP1, Figure 5) of the U2AF2-UHM domain (IC50 ∼ 30 μM).37 UHMCP1 and cmp9 were reported to induce splicing pattern changes in selective genes by inhibiting the UHM domains in HEK293 cells37 and a reconstituted minigene assay35 respectively. Both UHMCP1 and DS89092425 contain a primary amine group that can be protonated under physiological condition. To further assess the potential of the conserved Trp binding sites in different UHM domains for binding with inhibitors, we synthesized UHMCP1 and six analogs (Figure 5) by modifying the terminal amine group to investigate their activities against four UHM domains in this study. UHMCP1 (1) and analogs (2–7) were prepared via a reaction sequence of reductive amination and subsequent deprotection of Boc group using HCl or hydrolysis of an ester group as shown in Scheme 1. Note that UHMCP1 (1) and 4 have four stereoisomers according to the report,37 whereas 2, 3, and 5–7 have two stereoisomers, respectively.

Figure 5.

Binding affinity of UHMCP1 analogs to the UHM domains and the binding models of 5(S) (yellow) and 7(R) (yellow) to the UHM domains. The IC50 values are in μM and averages from at least two independent experiments. (B–H) Trp is shown in the line or stick models in green. The peptide ligands (U2AF2, cyclic peptide) are shown in a green loop structure and labeled. Acidic amino acids forming hydrogen bonds to the UHM domains are depicted in cyan dashed lines. The UHM domains are shown in surface representation and colored by the electrostatic potential with red, white, and blue indicating negative, neutral, and positive charged regions. The PDBIDs of the structures used for docking calculations are 1JMT(U2AF1), 5CXT(RBM39), 5LSO (SPF45), and 6SLO (PUF60). (I) Alignment of U2AF1-, RBM39-, SPF45-, and PUF60-UHM shows the residues form the Trp binding site. The labels (R375, L372, V382, M312, I395, L309) refer to the amino acids in SPF45-UHM. Residues at the similar locations to SPF45-UHM (V382, M312, I395, L309) are U2AF1-UHM (I140, I51, V113, L48), RBM39-UHM (I501, M431, V474, L428), and PUF60-UHM (V539, M446, I512, L463).

Scheme 1. General Synthetic Scheme to Prepare UHMCP1 and Analogs.

Reagents and conditions: (a) secondary amine, Ti(OiPr)4, THF, 65 °C; (b) NaBH(OAc)3, CH3OH, r.t.; (c) 4 M HCl in dioxane, r.t.; (d) LiOH, CH3OH/THF/H2O, r.t.. *: Chiral center.

In Figure 5, we showed UHMCP1 had an IC50 value of 74.85 ± 6.18 μM against SPF45-UHM. The binding affinity of UHMCP1 to other three UHM domains was much weaker. Based on the microplate assay, UHMCP1 had an IC50 value of 30 μM to U2AF2-UHM.37 When the amine group was positioned in the fused diazabicyclo-octane ring, the IC50 values of 2 to SPF45-UHM, RBM39-UHM and PUF60-UHM were not markedly changed but were ∼5-fold lower with U2AF1-UHM. Removing the bridged atoms (3) or adding a methyl-substituted group (4) on piperazine significantly reduced the activity across all UHM proteins. When the unbridged piperidine group was used, 5 gave the lowest IC50 values to all four UHM domains compared with other analogs. However, 5 exhibited <2-fold selectivity to all four UHM domains. Analysis of the all four UHM domains also showed that the Trp binding sites were partly surrounded by acidic amino acids (Figure S1A–D). To investigate if the carboxylic or ester group will impact on the binding of the compounds, we synthesized 6 and 7 in a manner similar to 5 but with opposite electron density. Dramatic reductions in the activities of 6 and 7 to all four UHM proteins were observed except that 7 had an IC50 of 212.8 μM against SPF45-UHM. Despite the differences of the activities and selectivity of 1–5 to the four UHM domains observed here, these compounds contain stereoisomers. Compounds 2, 3, and 5–7 had two stereoisomers, whereas UHMCP1 and 4 had four. Binding affinities of stereospecific compounds in 1–7 to these UHM domains need to be evaluated to guide future optimization. The binding affinities data of 1–5 with four UHM domains also confirmed that Trp can serve as a primary recognition motif.

To understand the factors contributing to the selectivity of the inhibitors, we aligned U2AF1-, RBM39-, SPF45-, and PUF60-UHM with different peptides including U2AF2-, SF3B1-, and SF1-ULM (Figure S1). In the ULM peptide, the conserved Trp is flanked by an Asp/Asn and an Arg/Tyr residue to interact with the UHM domains (Figure S1E). The conserved Arg/Lys discussed in Figure 2 was further away from the Trp binding site. Because the sizes of our inhibitors (Figure 5) are small, the basic amine groups in the inhibitors likely formed hydrogen bonds with the nearby acidic amino acids around the Trp binding pocket in the UHM domains (Figure S1A–D) but not with the conserved Arg/Lys (Figure S1E). To confirm this observation, we subsequently performed docking calculations of the most potent compound 5 with all four UHM domains. Based on the docking scores of the top binding poses, 5(S), the S-form, was predicted to have higher affinity than 5(R), the R-form, with all four UHM domains (Table S1, Figure S2A–D). Therefore, we used the binding models of 5(S) with all four UHM domains for discussion in Figure 5. Based on the binding modes of 5(S), the indole group may adopt either a horizontal orientation (similar to Trp in the ULM peptides) with U2AF1-UHM or a vertical orientation with RBM39-UHM, SPF45-UHM (Figure 5B–E). For PUF60-UHM, the indole group in 5(S) adopted a flipped horizontal orientation in the binding site (Figure 5E). In U2AF1-, RBM39-, SPF45-UHM, the indole group of 5(S) formed a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl of E84, W495, Y376 in these three UHM domains, respectively (Figure 5B–D). No hydrogen bond was formed between the indole group of 5(S) with PUF60-UHM (Figure 5E). This may be contributed to that the binding site in PUF60-UHM was adopted to an inhibitor possessing a different scaffold. The binding mode of 5 with PUF60-UHM remains to be determined experimentally. Additionally, the terminal substituted piperazine group in 5(S) formed salt-bridged hydrogen bonds with nearby acidic amino acids as hypothesized (Figures 5B–E). Using U2AF1-UHM and the S-form of compounds 2 and 3 as examples, we found that the bridged atoms in 2(S) may constrain two basic amine atoms in cis conformation to form stronger bifurcated hydrogen bonds with carboxylic group in E88 (Figure S2E). Further, the terminal amine group of the piperazine in 3(S) was not as far-reaching as 5(S) to establish a stronger hydrogen bond with E83 (Figure S2F) that resulted in a lower affinity in 3.

A significant selectivity was observed in 7 that had an IC50 value of 212.8 μM with SPF45-UHM but >1 mM to other UHM domains. In this case, we did not find reasonable binding models of 7(S) with the UHM domains. When 7(R) was used, we found that the carboxylic group in 7(R) may form a salt-bridged interaction with R375 and the backbone carbonyl group of Y376, capturing the interaction between the Asp side chain in the cyclic peptide and R375 in SPF45-UHM (Figure 5H). Such interaction was not found between 7(R) and U2AF1-, RBM39-UHM, whereas no reasonable binding mode of 7(R) with PUF60-UHM was found. The contribution of this salt-bridge interaction to the selectivity of 7 to SPF45-UHM remain to be explored. Our analysis of the Trp binding site in the UHM domains also suggested that the binding site shaped by L309, I355, M312, and V382 in SPF45-UHM (Figure 5I) positioned 7(R) to allow the carboxylic group to interact with R375 and was assisted by the conformation preference of the chiral methyl group in 7. L309, I355, M312, and V382 were not conserved in the U2AF1-UHM and RBM39-UHM but conserved in PUF60-UHM. In PUF60-UHM, whether F334 (Figure 5E) functions as a gatekeeper to prevent 7 from adopting favorable interaction with R532 needs to be investigated. Differences of the hydrophobic resides forming the Trp binding site in the UHM domains may also offer opportunities for developing selective inhibitors. Although we have constructed binding models of select inhibitors with all four UHM domains, the precise binding modes of these compounds with the UHM domains need to be determined experimentally. Nevertheless, our computational modeling analyses suggested different optimization strategies in 5 that could lead to the development of pan- or selective inhibitors against different UHM domains. Taken together, UHMCP1 and 7 were relatively selective to SPF45-UHM, while 5 was most potent and had the least selectivity against U2AF1-, SPF45-, RBM39-, and PUF60-UHM.

In summary, we have developed biochemical HTRF assays to measure the binding affinities between four UHM domains and six ULM peptides from endogenous proteins. The assays allowed us to characterize the selectivity of the ULM peptides to each UHM domain. U2AF1-UHM exhibited the highest selectivity to these ULM peptides while PUF60-UHM had lowest selectivity. To lay the foundation for small-molecule inhibitors development, we computationally analyzed the binding sites of five UHM domains and assessed that the UHM domains are attractive binding sites for future study. Indeed, small-molecule inhibitors targeting these UHM domains started to emerge and their IC50 values are in 10–50 μM range. Using a recently discovered Trp-based inhibitor as a template, we further showed that the activities and selectivity of the compounds can be fine-tuned by changing the position of the basic amine group and the nearby hydrophobic group. Our binding sites profiling of the UHM domains using endogenous peptides and a class of small-molecule inhibitors should be useful for developing UHM domain inhibitors in future. Taking compound 5 as an example, additional modifications to the indole group and the piperidine group are feasible and may potentially lead to improved activity and selectivity. Future development of potent and selective UHM domain inhibitors will serve as an important tool to validate the UHM containing proteins as therapeutic targets in cancer.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- UHM

U2 auxiliary factor homology motif

- U2AF1

U2 auxiliary factor 1

- ULM

U2AF ligand motif

- Znf

zinc finger domain

- RS

arginine/serine-rich domain

- RRM

RNA recognition motif

- G-patch

G-patch domain

- Coil–Coil

coil–coil domain

- KH-QUA2

K-homology/quaking 2 domain

- Pro-Rich

proline-rich domain

- HEAT repeats

Huntingtin, elongation factor 3, protein phosphatase 2A, and the yeast kinase TOR1 repeats

- AXH

ataxin domain

- MRS

methionyl-tRNA synthetase

- Q

poly(Q) domain

- RBM39

RNA-binding protein 39

- SPF45

splicing factor 45

- PUF60

poly(U)-binding-splicing factor PUF60

- SF1

splicing factor 1

- SF3b1

splicing factor 3b subunit

- ATXN1

ataxin-1

- Trx

thioredoxin

- Trp

tryptophan

- r.t.

room temperature

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00537.

Materials and methods, mass spectra, NMR spectra, computational modeling, and HTRF assay methods (PDF)

Author Contributions

X.Y. synthesized the compounds; X.Y., K.H., and M.K.S. conducted the biochemical assay; C.-Y.Y. performed computer modeling; K.C. and J.A.S. expressed the proteins; C.-Y.Y. designed and supervised the study. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The work was supported by R21CA270590 from the National Institute of Health. Additional supports were provided by the UTHSC College of Pharmacy startup fund and the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center Core Grant from the National Cancer Institute, NIH (P30 CA046592). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Michael Sattler for providing the GSAM-linked Trx-PUF60-UHM construct and Dejian Ma for technical assistance in collecting the analytical data of the compounds.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lee Y.; Rio D. C. Mechanisms and Regulation of Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 291–323. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow J.; Frankish A.; Gonzalez J. M.; Tapanari E.; Diekhans M.; Kokocinski F.; Aken B. L.; Barrell D.; Zadissa A.; Searle S.; Barnes I.; Bignell A.; Boychenko V.; Hunt T.; Kay M.; Mukherjee G.; Rajan J.; Despacio-Reyes G.; Saunders G.; Steward C.; Harte R.; Lin M.; Howald C.; Tanzer A.; Derrien T.; Chrast J.; Walters N.; Balasubramanian S.; Pei B.; Tress M.; Rodriguez J. M.; Ezkurdia I.; van Baren J.; Brent M.; Haussler D.; Kellis M.; Valencia A.; Reymond A.; Gerstein M.; Guigo R.; Hubbard T. J. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1760–1774. 10.1101/gr.135350.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J. D.; Barrios-Rodiles M.; Colak R.; Irimia M.; Kim T.; Calarco J. A.; Wang X.; Pan Q.; O’Hanlon D.; Kim P. M.; Wrana J. L.; Blencowe B. J. Tissue-specific alternative splicing remodels protein-protein interaction networks. Mol. Cell 2012, 46, 884–892. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlén M.; Fagerberg L.; Hallström B. M.; Lindskog C.; Oksvold P.; Mardinoglu A.; Sivertsson Å.; Kampf C.; Sjöstedt E.; Asplund A.; Olsson I.; Edlund K.; Lundberg E.; Navani S.; Szigyarto C. A.-K.; Odeberg J.; Djureinovic D.; Takanen J. O.; Hober S.; Alm T.; Edqvist P.-H.; Berling H.; Tegel H.; Mulder J.; Rockberg J.; Nilsson P.; Schwenk J. M.; Hamsten M.; von Feilitzen K.; Forsberg M.; Persson L.; Johansson F.; Zwahlen M.; von Heijne G.; Nielsen J.; Pontén F. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsotra A.; Cooper T. A. Functional consequences of developmentally regulated alternative splicing. Nat. Rev. Genet 2011, 12, 715–729. 10.1038/nrg3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. J.; Wang Q.; Kennedy C. J.; Silver P. A. An Alternative Splicing Network Links Cell-Cycle Control to Apoptosis. Cell 2010, 142, 625–636. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotti M. M.; Swanson M. S. RNA mis-splicing in disease. Nat. Rev. Genet 2016, 17, 19–32. 10.1038/nrg.2015.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K.; Sanada M.; Shiraishi Y.; Nowak D.; Nagata Y.; Yamamoto R.; Sato Y.; Sato-Otsubo A.; Kon A.; Nagasaki M.; Chalkidis G.; Suzuki Y.; Shiosaka M.; Kawahata R.; Yamaguchi T.; Otsu M.; Obara N.; Sakata-Yanagimoto M.; Ishiyama K.; Mori H.; Nolte F.; Hofmann W. K.; Miyawaki S.; Sugano S.; Haferlach C.; Koeffler H. P.; Shih L. Y.; Haferlach T.; Chiba S.; Nakauchi H.; Miyano S.; Ogawa S. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature 2011, 478, 64–69. 10.1038/nature10496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graubert T. A.; Shen D.; Ding L.; Okeyo-Owuor T.; Lunn C. L.; Shao J.; Krysiak K.; Harris C. C.; Koboldt D. C.; Larson D. E.; McLellan M. D.; Dooling D. J.; Abbott R. M.; Fulton R. S.; Schmidt H.; Kalicki-Veizer J.; O’Laughlin M.; Grillot M.; Baty J.; Heath S.; Frater J. L.; Nasim T.; Link D. C.; Tomasson M. H.; Westervelt P.; DiPersio J. F.; Mardis E. R.; Ley T. J.; Wilson R. K.; Walter M. J. Recurrent mutations in the U2AF1 splicing factor in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 53–57. 10.1038/ng.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makishima H.; Yoshizato T.; Yoshida K.; Sekeres M. A.; Radivoyevitch T.; Suzuki H.; Przychodzen B.; Nagata Y.; Meggendorfer M.; Sanada M.; Okuno Y.; Hirsch C.; Kuzmanovic T.; Sato Y.; Sato-Otsubo A.; LaFramboise T.; Hosono N.; Shiraishi Y.; Chiba K.; Haferlach C.; Kern W.; Tanaka H.; Shiozawa Y.; Gomez-Segui I.; Husseinzadeh H. D.; Thota S.; Guinta K. M.; Dienes B.; Nakamaki T.; Miyawaki S.; Saunthararajah Y.; Chiba S.; Miyano S.; Shih L. Y.; Haferlach T.; Ogawa S.; Maciejewski J. P. Dynamics of clonal evolution in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 204–212. 10.1038/ng.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H.; Lane A. A.; Correll M.; Przychodzen B.; Sykes D. B.; Stone R. M.; Ballen K. K.; Amrein P. C.; Maciejewski J.; Attar E. C. Putative RNA-splicing gene LUC7L2 on 7q34 represents a candidate gene in pathogenesis of myeloid malignancies. Blood Cancer Journal 2013, 3, e117. 10.1038/bcj.2013.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger C. E.; Hosono N.; Singh J.; Dietrich R. C.; Gu X.; Makishima H.; Saunthararajah Y.; Maciejewski J. P.; Padgett R. A. The Role of LUC7L2 in Splicing and MDS. Blood 2016, 128, 5504–5504. 10.1182/blood.V128.22.5504.5504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger C. E.; Moyer D. C.; Adema V.; Kerr C. M.; Walter W.; Hutter S.; Meggendorfer M.; Baer C.; Kern W.; Nadarajah N.; Twardziok S.; Sekeres M. A.; Haferlach C.; Haferlach T.; Maciejewski J. P.; Padgett R. A. Complex landscape of alternative splicing in myeloid neoplasms. Leukemia 2021, 35, 1108–1120. 10.1038/s41375-020-1002-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebestyen E.; Singh B.; Minana B.; Pages A.; Mateo F.; Pujana M. A.; Valcarcel J.; Eyras E. Large-scale analysis of genome and transcriptome alterations in multiple tumors unveils novel cancer-relevant splicing networks. Genome Res. 2016, 26, 732–744. 10.1101/gr.199935.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler M.; Peng S.; Agrawal A. A.; Palacino J.; Teng T.; Zhu P.; Smith P. G.; Buonamici S.; Yu L.; et al. Somatic Mutational Landscape of Splicing Factor Genes and Their Functional Consequences across 33 Cancer Types. Cell reports 2018, 23, 282–296. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez B.; Walter M. J.; Graubert T. A. Splicing factor gene mutations in hematologic malignancies. Blood 2017, 129, 1260–1269. 10.1182/blood-2016-10-692400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling A. S.; Gibson C. J.; Ebert B. L. The genetics of myelodysplastic syndrome: from clonal haematopoiesis to secondary leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 5–19. 10.1038/nrc.2016.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oscier D. G.; Rose-Zerilli M. J.; Winkelmann N.; Gonzalez de Castro D.; Gomez B.; Forster J.; Parker H.; Parker A.; Gardiner A.; Collins A.; Else M.; Cross N. C.; Catovsky D.; Strefford J. C. The clinical significance of NOTCH1 and SF3B1 mutations in the UK LRF CLL4 trial. Blood 2013, 121, 468–475. 10.1182/blood-2012-05-429282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorge J.; Petronilho S.; Alves R.; Coucelo M.; Goncalves A. C.; Nascimento Costa J. M.; Sarmento-Ribeiro A. B. Apoptosis induction and cell cycle arrest of pladienolide B in erythroleukemia cell lines. Investigational new drugs 2019, 38, 369–377. 10.1007/s10637-019-00796-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damm F.; Kosmider O.; Gelsi-Boyer V.; Renneville A.; Carbuccia N.; Hidalgo-Curtis C.; Della Valle V.; Couronne L.; Scourzic L.; Chesnais V.; et al. Mutations affecting mRNA splicing define distinct clinical phenotypes and correlate with patient outcome in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2012, 119, 3211–3218. 10.1182/blood-2011-12-400994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S. J.; Tang J. L.; Lin C. T.; Kuo Y. Y.; Li L. Y.; Tseng M. H.; Huang C. F.; Lai Y. J.; Lee F. Y.; Liu M. C.; et al. Clinical implications of U2AF1 mutation in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and its stability during disease progression. Am. J. Hematol 2013, 88, E277–282. 10.1002/ajh.23541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackereth C. D.; Madl T.; Bonnal S.; Simon B.; Zanier K.; Gasch A.; Rybin V.; Valcarcel J.; Sattler M. Multi-domain conformational selection underlies pre-mRNA splicing regulation by U2AF. Nature 2011, 475, 408–411. 10.1038/nature10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haferlach T.; Nagata Y.; Grossmann V.; Okuno Y.; Bacher U.; Nagae G.; Schnittger S.; Sanada M.; Kon A.; Alpermann T.; Yoshida K.; Roller A.; Nadarajah N.; Shiraishi Y.; Shiozawa Y.; Chiba K.; Tanaka H.; Koeffler H. P.; Klein H. U.; Dugas M.; Aburatani H.; Kohlmann A.; Miyano S.; Haferlach C.; Kern W.; Ogawa S. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 2014, 28, 241–247. 10.1038/leu.2013.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przychodzen B.; Jerez A.; Guinta K.; Sekeres M. A.; Padgett R.; Maciejewski J. P.; Makishima H. Patterns of missplicing due to somatic U2AF1 mutations in myeloid neoplasms. Blood 2013, 122, 999–1006. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-480970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip B. H.; Steeples V.; Repapi E.; Armstrong R. N.; Llorian M.; Roy S.; Shaw J.; Dolatshad H.; Taylor S.; Verma A.; Bartenstein M.; Vyas P.; Cross N. C.; Malcovati L.; Cazzola M.; Hellstrom-Lindberg E.; Ogawa S.; Smith C. W.; Pellagatti A.; Boultwood J. The U2AF1S34F mutation induces lineage-specific splicing alterations in myelodysplastic syndromes. J. Clin Invest 2017, 127, 3557. 10.1172/JCI96202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei D. L.; Zhen T.; Durham B.; Ferrarone J.; Zhang T.; Garrett L.; Yoshimi A.; Abdel-Wahab O.; Bradley R. K.; Liu P.; Varmus H. Impaired hematopoiesis and leukemia development in mice with a conditional knock-in allele of a mutant splicing factor gene U2af1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, E10437–E10446. 10.1073/pnas.1812669115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. M.; Ou J.; Chamberlain L.; Simone T. M.; Yang H.; Virbasius C. M.; Ali A. M.; Zhu L. J.; Mukherjee S.; Raza A.; Green M. R. U2AF35(S34F) Promotes Transformation by Directing Aberrant ATG7 Pre-mRNA 3′ End Formation. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 479–490. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. A.; Choudhary G. S.; Pellagatti A.; Choi K.; Bolanos L. C.; Bhagat T. D.; Gordon-Mitchell S.; Von Ahrens D.; Pradhan K.; Steeples V.; Kim S.; Steidl U.; Walter M.; Fraser I. D. C.; Kulkarni A.; Salomonis N.; Komurov K.; Boultwood J.; Verma A.; Starczynowski D. T. U2AF1 mutations induce oncogenic IRAK4 isoforms and activate innate immune pathways in myeloid malignancies. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 640–650. 10.1038/s41556-019-0314-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirai C. L.; White B. S.; Tripathi M.; Tapia R.; Ley J. N.; Ndonwi M.; Kim S.; Shao J.; Carver A.; Saez B.; et al. Mutant U2AF1-expressing cells are sensitive to pharmacological modulation of the spliceosome. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14060. 10.1038/ncomms14060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadugu B. A.; Nonavinkere Srivatsan S.; Heard A.; Alberti M. O.; Ndonwi M.; Liu J.; Grieb S.; Bradley J.; Shao J.; Ahmed T.; et al. U2af1 is a haplo-essential gene required for hematopoietic cancer cell survival in mice. J. Clin Invest 2021, 131, 131. 10.1172/JCI141401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatrikhi R.; Feeney C. F.; Pulvino M. J.; Alachouzos G.; MacRae A. J.; Falls Z.; Rai S.; Brennessel W. W.; Jenkins J. L.; Walter M. J. A synthetic small molecule stalls pre-mRNA splicing by promoting an early-stage U2AF2-RNA complex. Cell Chem. Biol. 2021, 28, 1145. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loerch S.; Kielkopf C. L. Unmasking the U2AF homology motif family: a bona fide protein–protein interaction motif in disguise. RNA 2016, 22, 1795–1807. 10.1261/rna.057950.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Chiara C.; Menon R. P.; Strom M.; Gibson T. J.; Pastore A. Phosphorylation of S776 and 14–3-3 binding modulate ataxin-1 interaction with splicing factors. PLoS One 2009, 4, e8372. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabis M.; Corsini L.; Vincendeau M.; Tripsianes K.; Gibson T. J.; Brack-Werner R.; Sattler M. Modulation of HIV-1 gene expression by binding of a ULM motif in the Rev protein to UHM-containing splicing factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 4859–4871. 10.1093/nar/gkz185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagtap P. K. A.; Kubelka T.; Soni K.; Will C. L.; Garg D.; Sippel C.; Kapp T. G.; Potukuchi H. K.; Schorpp K.; Hadian K.; et al. Identification of phenothiazine derivatives as UHM-binding inhibitors of early spliceosome assembly. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5621. 10.1038/s41467-020-19514-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa H.; Shimada T.; Takahashi M.; Takahashi H. Revisiting biomolecular NMR spectroscopy for promoting small-molecule drug discovery. J. Biomol NMR 2020, 74, 501–508. 10.1007/s10858-020-00314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A.; Clement M. J.; Craveur P.; El Hage K.; Salone J. M.; Bollot G.; Pastre D.; Maucuer A. Identification of a small molecule splicing inhibitor targeting UHM domains. Febs J. 2022, 289, 682–698. 10.1111/febs.16199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielkopf C. L.; Rodionova N. A.; Green M. R.; Burley S. K. A Novel Peptide Recognition Mode Revealed by the X-Ray Structure of a Core U2AF35/U2AF65 Heterodimer. Cell 2001, 106, 595–605. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren T. A. Identifying and Characterizing Binding Sites and Assessing Druggability. J. Chem. Inf Model 2009, 49, 377. 10.1021/ci800324m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagtap P. K.; Garg D.; Kapp T. G.; Will C. L.; Demmer O.; Luhrmann R.; Kessler H.; Sattler M. Rational Design of Cyclic Peptide Inhibitors of U2AF Homology Motif (UHM) Domains To Modulate Pre-mRNA Splicing. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 10190–10197. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.