Abstract

Chemical- and enzyme-coated beads (ChemBeads and EnzyBeads) were introduced recently as a universal strategy for the accurate dispensing of various solids in submilligram quantities using automated instrumentation or manual dispensing. The coated beads are prepared using a resonant acoustic mixer (RAM)—an instrument that may be available only to well-established facilities. In this study, we evaluated alternative coating methods for preparing ChemBeads and EnzyBeads without the use of a RAM. We also evaluated the effects of bead sizes on loading accuracy using 4 coating methods and 12 solids (9 chemicals and 3 enzymes) as test subjects. While our original RAM coating method is the most versatile for the broadest range of solids, high-quality ChemBeads and EnzyBeads that are suitable for high-throughput experimentation can be prepared using alternative methods. These results should make ChemBeads and EnzyBeads readily accessible as the core technology for setting up high-throughput experimentation platforms.

Keywords: High-throughput experimentation, ChemBeads, EnzyBeads, Solid dispensing, Microscale experiments

High-throughput experimentation (HTE) and reaction miniaturization are becoming popular techniques to enable drug discovery and development where precious research materials are in low availability.1−3 The success of these technologies can be attributed to advancements in laboratory automation that can facilitate liquid handling and experiment setup. Many experiments have been adapted for HTE platforms. For example, scientists can evaluate hundreds of reaction conditions for product conversion, experimental conditions for optimal crystallization, or solvents for optimal solubility. Seeing the immense value of HTE, academic institutions are also beginning to invest in HTE core facilities.4,5 A successful HTE campaign should be small in experiment scale and large in number. These requirements translate to the need for scientists to manage a large number of reagents (tens to hundreds) in small quantities (milligram to submilligram). A major challenge in HTE is reliable solid dispensing at small scales.6,7 While there are plenty of commercial options available for solid-dispensing automation, we have experienced that when dosing small amounts of chemicals (low to submilligram scale), these instruments are not meeting the dosing range and accuracy required to accurately conduct small scale HTE.6

To remedy this, we invented solid-coated bead technologies (ChemBeads and EnzyBeads)—a simple, chemically inert solution to the solid dispensing problem—that can be used either with automated solid dispensing equipment or manually with calibrated weighing scoops.8−11 The technique behind the coated bead technology is a process called dry particle coating,12−17 where glass or polystyrene beads (larger host particle) are mixed with a solid (smaller guest particle). When an external mechanical force (e.g., shaking) is added to the mixture, the smaller guest particles will noncovalently adhere to the surface of the larger host particle via van der Waals forces (Figure 1A). The weight by weight (w/w) ratio of the solid to the beads was kept low (typically 5%), and the coated beads retained the favorable physical properties (uniform density and high flowability) of the host beads.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic depicting dry particle coating theory. (B) Bead sizes evaluated in this study (MorDalPhos Pd G3-coated beads shown).

The premise behind ChemBeads and EnzyBeads is straightforward and can be considered as a solid “stock solution,” where instead of the solids being dissolved by a solvent, they are dispersed onto the surface of glass or polystyrene beads. Since the solids are noncovalently coated onto the surface of beads, they are readily released from the surface when an experiment solvent is added. ChemBeads and EnzyBeads formulations have unified various solid properties (flowability, particle size, crystals versus powder, etc.) into a single favorable form that can be conveniently handled manually or by an automated solid dispensing instrument. Using ChemBead and EnzyBead as the core technology at AbbVie, we have successfully built a comprehensive HTE platform with more than 20 chemical transformations utilizing over 1000 different solids. The HTE platform has produced over 500 screens for the past several years and positively impacted numerous medicinal chemistry projects.

Our original protocols for ChemBead and EnzyBead preparation used a Resodyn resonant acoustic mixer (RAM),18 an instrument that may be available to well-established facilities but is less commonly available in smaller laboratories because of budget and space constraints, to provide the mechanical force. We received feedback from scientists (from academia, government institutions, small biotech, and large pharmaceutical companies) that they are interested in ChemBeads and EnzyBeads but do not have the resources available to acquire a RAM and they have attempted to make ChemBeads using common shakers found in the laboratory.19,20 Herein, we quantitatively evaluated three additional coating methods for the preparation of ChemBeads and EnzyBeads using cost-effective equipment with a small laboratory bench footprint (<US$650, Table 1 and Table S2). Our goal is to remove the barrier that solid dispensing presents to the HTE community by making ChemBeads and EnzyBeads core technologies for small-scale experiment setup.

Table 1. ChemBead and EnzyBead Coating Methods Investigated in This Study.

| coating method | catalog price (USD) | mixing time (min) | g-force/speed setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAM | >60 000 | 10 | 50 |

| hand mixing | 0 | 5 | |

| vortex mixer | 637 | 15 | 7 |

| mini vortex mixer | 282 | 10 |

In our initial protocols, we formulated ChemBeads by coating 212–300 μm (medium) glass beads with powdered solids using RAM. Using these general methods, we have coated over 1000 reagents onto ChemBeads ranging from 5 to 20% (w/w) loading. ChemBeads have been successfully incorporated into high-throughput experimentation screening sets and have positively impacted drug discovery and reaction development,19−21 thereby saving valuable time and resources. For this study, we investigated four coating methods (Table 1); three glass bead diameter sizes [150–212 μm (small), 212–300 μm (medium), and 1 mm (large)] (Figure 1B); and 12 solids representing four different types of chemicals, including precatalysts and ligands (XPhos Pd G3, BrettPhos Pd G3, MorDalPhos Pd G3, DavePhos Pd G3, RuPhos), druglike small molecules (ketoprofen and noscapine), inorganic bases (potassium carbonate and cesium carbonate), and enzyme-containing cell-free lysate powders (3 ketoreductases).

To fairly compare the different methods, two factors were considered. First, a fine powder is critical for even and homogeneous coating. Therefore, prior to coating, all solids were milled into a fine powder by subjecting the solids to RAM mixing (70g, 5 min) in the presence of ceramic milling balls. A similar consistency and ChemBeads coating can be achieved when the solids are milled into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle (Figures S1, S12, and S13). Second, we standardized the coating methods across the bead and solid types. This resulted in lower-than-expected loadings that could normally be remedied by reiterative rounds of coating or by adjusting the mixing forces. We determined that coating efficiency is compound- and bead-size-dependent, and ultimately, in the reaction we tested, the coating method had minimal effects on experiment outcome.

In our initial evaluations of ChemBeads, we showed that 5% (w/w) loaded ChemBeads prepared by RAM could reliably deliver desired quantities of chemical within ±10% error, oftentimes within ±5% error.8,10 This became our standard for comparison in evaluating alternative ChemBead coating methods. Therefore, we evaluated whether a coating method could produce ChemBeads that reliably delivered solids with similar accuracy and targeted percent loading. From each batch of ChemBeads, we analyzed six samples using either UV absorption or weight recovery methods (Figures 2, 3, S7, and S8). For the UV absorption method, a calibration curve was generated, and the linear regression equation was used to calculate the total amount of chemical loaded onto the beads, along with the percent error on the basis of the expected mass.

Figure 2.

Analysis of percentage error comparing different bead sizes, coating methods, and compounds. Percent error was calculated by comparing the expected amount of compound with the amount measured by UPLC analysis (n = 6, bars represent minimum and maximum values, x denotes the average percent error). The solid line represents a percent error of zero, and the dash lines mark ±10% error. Methods for percentage error calculations are described in the Supporting Information.

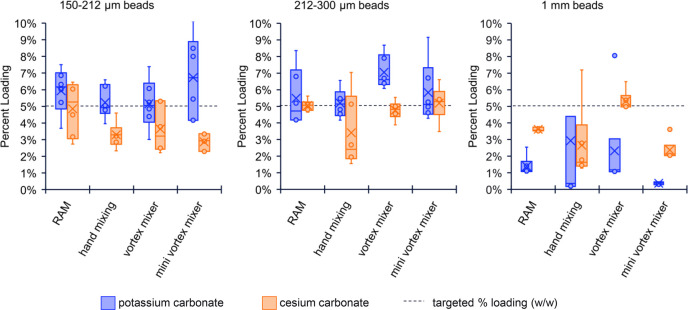

Figure 3.

Analysis of percentage loading comparing different bead sizes and coating methods for solid inorganic bases calculated by weight recovery. Dashed line represents targeted 5% loading (w/w).

We noticed two main trends in the results. First, ChemBead loading accuracy is dependent on bead size (Figure 2, Table S6). The small sized beads had more variation across the analytical samples compared with the medium and large sized beads. Interestingly, although hand coating provided the smallest variation in the dispensing of all four chemicals, these beads tended to have a lower percent loading (Figure S8, Table S5). While there is no lower limit to how small a quantity of solid material can be loaded, coated beads will have an upper limit where the accuracy will become unreliable (Figure S7). The maximum achievable percent loading is dependent on the compound, the environment (humidity, temperature), and the mixing container material (plastic vs glass). We determined that 5% targeted loading (w/w) for small- and medium-sized beads and 1% (w/w) for large sized beads is an ideal starting point. For the solids and bead sizes we tested, we determined that there was no substantial advantage for one coating method over another. In situations where precise ChemBead loading is required, users could use analytical methods to determine the precise loading of ChemBeads prior to conducting any experiments.

We also found that not all chemicals are suitable for ChemBead coating. For example, sticky or hydroscopic solids may not coat as efficiently. However, with some additional effort, such as predrying the solids and glass beads, a longer coating time or repeated coating cycles with an incremental addition of solid, or stronger g forces, these solids can still be formulated into ChemBeads. Inorganic bases, such as potassium carbonate and cesium carbonate, can be successfully coated when milled into fine powders (Figure 3, Table S9). Generally, the alternative coating methods produced less evenly coated small and large ChemBeads (evidenced by broad boxes). Our original protocol (RAM, medium beads) reliably produced quality ChemBeads of inorganic bases close to the targeted loading.

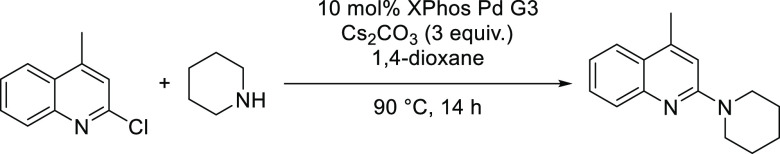

On the basis of our experience, and in most cases, the percent loading error of ChemBeads has minimal effect on HTE experiment outcomes. As an example, we ran the same C–N coupling reaction using XPhos Pd G3 ChemBeads coated by the different methods and compared it against directly adding the catalyst. It is easier to consistently weigh 10 mg of ChemBeads using calibrated scoops versus weighing <0.5 mg of catalyst per reaction. Ultimately, there was no substantial difference in the reaction outcome as determined by product conversion (Scheme 1, Table 2).

Scheme 1. C–N Coupling Reaction for Evaluating Effects of ChemBead Coating Accuracy on Reaction Outcomes.

Table 2. C–N Coupling Reaction Results Using ChemBeads Prepared by Different Coating Methods.

| coating method | actual loading (w/w) | bead mass (mg) | actual reagent mass (mg) | percent conversion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| free catalyst | 0.5 | 82 | ||

| RAM | 4.61 | 10 | 0.46 | 89 |

| hand mixing | 3.96 | 10 | 0.39 | 89 |

| vortex mixer | 5.01 | 10 | 0.50 | 85 |

| mini vortex mixer | 4.31 | 10 | 0.43 | 83 |

A unique feature of ChemBeads and EnzyBeads is the ability to coat multiple reagents onto a single batch of beads (mixed beads). In the case of mixed ChemBeads, the solid reagents (catalysts, ligands, bases, etc.) needed for the reaction can be coated in the appropriate stoichiometry and added to the reaction in a single weighing step.8 Then, the reaction is easily assembled by adding the reaction solvents and liquid reagents. In the case of mixed EnzyBeads, enzymes and cofactors can be coated on the same batch of beads and added to a buffer solution and substrate to initiate the reaction.22 This is particularly useful when starting materials are in limited quantity (<5 mg): they can be mixed with other solids before coating on beads, thereby making the coating process more convenient. The use of mixed reagents23 and mixed beads reduces the need to weigh multiple reagents, thereby saving time, simplifying the operation complexity, and also enabling nanomole-scale reactions with limited materials.

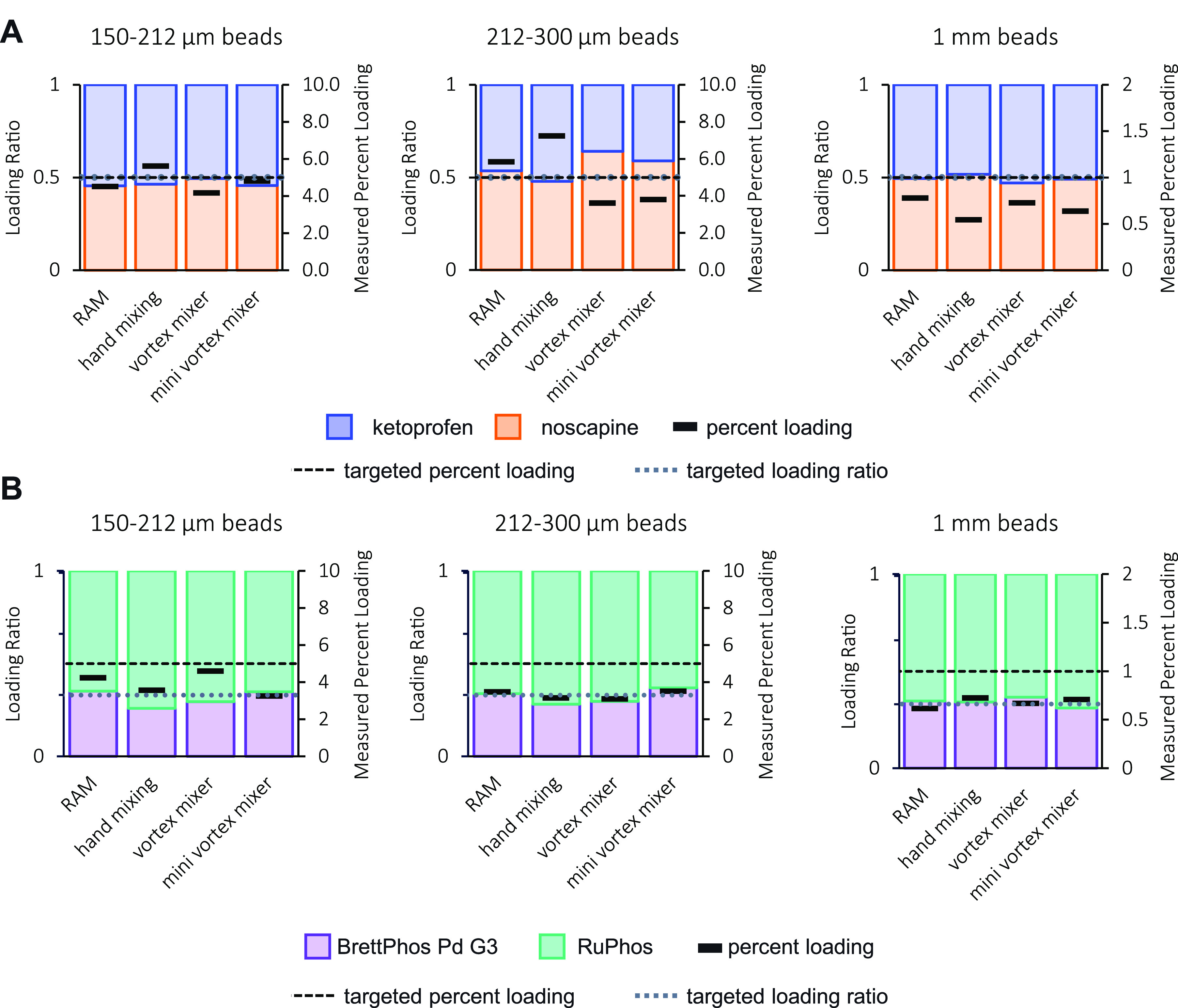

In our study we evaluated two combinations of mixed ChemBeads for loading accuracy. For the first batch, we coated ketoprofen and noscapine, which are two well-behaved powdered compounds that are commonly used as UPLC standards for their stability (Figures 4A and S10). For the second batch, we evaluated RuPhos and BrettPhos Pd G3 in a 2:1 molar ratio as an example of a combination that might be used for a cross-coupling reaction (Figures 4B and S11). We quantified the individual components using UPLC analysis and in both instances determined that the ratio between the two portions remained consistent through the different bead sizes and coating methods compared with the input mixture (Figure 4). The percentage loading, however, had considerable variation across samples, especially for the 150–212 μm sized beads, which is consistent with the ChemBeads formulated with a single reagent (Figure S6). Although the coating varies, on the experimental scale, a difference in percentage loading of 1% corresponds to only 0.1 mg of reagent for 10 mg of 5% (w/w) beads and in practice should have minimal effect on experimental outcomes.

Figure 4.

Mixed ChemBeads analysis. Average loading ratio and percent loading (w/w) (n = 6) measured for differently sized mixed ChemBeads prepared using different coating methods. The ratio of the solids subjected to coating and the targeted percent loadings are shown as dotted and dashed lines, respectively. (A) Ketoprofen and noscapine mixed beads were prepared with a 1:1 mixture of solids and either a 1% or 5% (w/w) targeted loading. (B) BrettPhos Pd G3 and RuPhos mixed beads were prepared with a 1:2 mixture of solids and either a 1% or 5% (w/w) targeted loading.

To complete our study, we evaluated our coating methods on the performance of EnzyBeads—enzyme-coated beads for biocatalytic reaction screening (Scheme 2, Figure 5).11 We coated polystyrene beads with three different ketoreductases using RAM, hand mixing, a vortex mixer, and a mini vortex mixer (Table 1 and Figures S11 and S12). We screened the beads for reaction efficiency using three different ketone substrates (Scheme 2, phenyl cyclohexanone, 2′ methoxyacetophenone, and phenoxyacetophenone) and compared the EnzyBeads to the uncoated lyophilized enzyme powder. When phenyl cyclohexanone was used as a substrate, there was no substantial difference in product conversion or reaction kinetics (Figure 5). This observation was consistent with the other substrates we tested (Figure 5). We also evaluated the stereoselectivity of the reaction of substrate 1 with the three ketoreductases and did not notice a difference between the beads coated using different methods and the corresponding free enzyme (Figure S14).

Scheme 2. General Reaction Scheme for Ketoreductase Reaction.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of EnzyBeads formulated using different coating methods. (A) Percent conversion of ketoreductase reactions determined by HPLC analysis. (B) Kinetic evaluation of substrate 1 conversion.

In conclusion, we quantitatively evaluated different readily accessible coating methods for preparing ChemBeads and EnzyBeads. While there may be slight variations across methods, the variations are unlikely to affect experimental outcomes. When choosing bead size for coating, we found that 212–300 μm and 1 mm beads generate ChemBeads with high accuracy and consistency. In addition, mixed ChemBeads can be generated in high accuracy to further simplify experimental setup. When preparing ChemBeads or EnzyBeads of sensitive reagents for the first time, it is important to confirm that any coating method used does not degrade the chemical and that the targeted loading is achieved. The ChemBeads and EnzyBeads described here can be implemented in workflows using an automated or manual reaction setup. With these methods, ChemBeads and EnzyBeads can be used by any scientists interested in HTE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Alexander Rago and Mary Bellizzi of AbbVie for helpful discussions in experimental design and setup.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- RAM

resonant acoustic mixer

- HTE

high-throughput experimentation

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00491.

Author Present Address

§ Department of Chemistry, New York University, 100 Washington Square E, New York, New York 10003, USA

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This research was sponsored by AbbVie.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): J.T.C.B., Y.W., and N.P.T. are employees of AbbVie. A.C.I. was an employee of AbbVie at the time of the study. The design, study conduct, and financial support for this research were provided by AbbVie. AbbVie participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the publication.

Special Issue

Published as part of the ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters virtual special issue “New Enabling Drug Discovery Technologies - Recent Progress”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Shevlin M. Practical High-Throughput Experimentation for Chemists. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8 (6), 601–607. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selekman J. A.; Qiu J.; Tran K.; Stevens J.; Rosso V.; Simmons E.; Xiao Y.; Janey J. High-Throughput Automation in Chemical Process Development. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2017, 8 (1), 525–547. 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-060816-101411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernak T.; Gesmundo N. J.; Dykstra K.; Yu Y.; Wu Z.; Shi Z.-C.; Vachal P.; Sperbeck D.; He S.; Murphy B. A.; Sonatore L.; Williams S.; Madeira M.; Verras A.; Reiter M.; Lee C. H.; Cuff J.; Sherer E. C.; Kuethe J.; Goble S.; Perrotto N.; Pinto S.; Shen D.-M.; Nargund R.; Balkovec J.; DeVita R. J.; Dreher S. D. Microscale High-Throughput Experimentation as an Enabling Technology in Drug Discovery: Application in the Discovery of (Piperidinyl)Pyridinyl-1H-Benzimidazole Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase 1 Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60 (9), 3594–3605. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmeier E. K.Groundbreaking chemistry research at record speeds. Penn Today; University of Pennsylvania, 2019. https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/groundbreaking-chemistry-research-record-speeds (accessed 2022-09-22).

- University of Delaware. Mission & Services – High Throughput Experimentation Center. https://sites.udel.edu/htecenter/ (accessed 2022-11-01).

- Bahr M. N.; Damon D. B.; Yates S. D.; Chin A. S.; Christopher J. D.; Cromer S.; Perrotto N.; Quiroz J.; Rosso V. Collaborative Evaluation of Commercially Available Automated Powder Dispensing Platforms for High-Throughput Experimentation in Pharmaceutical Applications. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2018, 22 (11), 1500–1508. 10.1021/acs.oprd.8b00259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr M. N.; Morris M. A.; Tu N. P.; Nandkeolyar A. Recent Advances in High-Throughput Automated Powder Dispensing Platforms for Pharmaceutical Applications. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020, 24 (11), 2752–2761. 10.1021/acs.oprd.0c00411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tu N. P.; Dombrowski A. W.; Goshu G. M.; Vasudevan A.; Djuric S. W.; Wang Y. High-Throughput Reaction Screening with Nanomoles of Solid Reagents Coated on Glass Beads. Angew. Chem. 2019, 131 (24), 8071–8075. 10.1002/ange.201900536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski A.; Tu N. P.; Wang Y.. High Throughput Methods for Screening Chemical Reactions Using Reagent-Coated Bulking Agents. US 20190033185 A1, 2019.

- Martin M. C.; Goshu G. M.; Hartnell J. R.; Morris C. D.; Wang Y.; Tu N. P. Versatile Methods to Dispense Submilligram Quantities of Solids Using Chemical-Coated Beads for High-Throughput Experimentation. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2019, 23 (9), 1900–1907. 10.1021/acs.oprd.9b00213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. T. C.; Tu N. P.; Phelan R. M. Solid, Noncovalent Formulation of Biocatalysts for Rapid and Accurate Submilligram Dosing to Microtiter Plates. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2021, 25 (2), 337–341. 10.1021/acs.oprd.0c00443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmash E. Z.; Mohammed A. R. Functionalised Particles Using Dry Powder Coating in Pharmaceutical Drug Delivery: Promises and Challenges. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery 2015, 12 (12), 1867–1879. 10.1517/17425247.2015.1071351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullarney M. P.; Beach L. E.; Davé R. N.; Langdon B. A.; Polizzi M.; Blackwood D. O. Applying Dry Powder Coatings to Pharmaceutical Powders Using a Comil for Improving Powder Flow and Bulk Density. Powder Technol. 2011, 212 (3), 397–402. 10.1016/j.powtec.2011.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomas J.; Kleinschmidt S. Improvement of Flowability of Fine Cohesive Powders by Flow Additives. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2009, 32 (10), 1470–1483. 10.1002/ceat.200900173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Sliva A.; Banerjee A.; Dave R. N.; Pfeffer R. Dry Particle Coating for Improving the Flowability of Cohesive Powders. Powder Technol. 2005, 158 (1), 21–33. 10.1016/j.powtec.2005.04.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer R.; Dave R. N.; Wei D.; Ramlakhan M. Synthesis of Engineered Particulates with Tailored Properties Using Dry Particle Coating. Powder Technol. 2001, 117 (1), 40–67. 10.1016/S0032-5910(01)00314-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramlakhan M.; Wu C. Y.; Watano S.; Dave R. N.; Pfeffer R. Dry Particle Coating Using Magnetically Assisted Impaction Coating: Modification of Surface Properties and Optimization of System and Operating Parameters. Powder Technol. 2000, 112 (1), 137–148. 10.1016/S0032-5910(99)00314-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resodyn Corporation. Home. https://resodyn.com/ (accessed 2022-10-05).

- Aguirre A. L.; Loud N. L.; Johnson K. A.; Weix D. J.; Wang Y. ChemBead Enabled High-Throughput Cross-Electrophile Coupling Reveals a New Complementary Ligand. Chemistry 2021, 27 (51), 12981–12986. 10.1002/chem.202102347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K.; Loud N. L.; DiBenedetto T. A.; Weix D. J. A General, Multimetallic Cross-Ullmann Biheteroaryl Synthesis from Heteroaryl Halides and Heteroaryl Triflates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (51), 21484–21491. 10.1021/jacs.1c10907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fordham J. M.; Kollmus P.; Cavegn M.; Schneider R.; Santagostino M. A “Pool and Split” Approach to the Optimization of Challenging Pd-Catalyzed C–N Cross-Coupling Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87 (6), 4400–4414. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c00104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Chew J.; Nha Ho T. T.; Ken Lee C.-L. Biocatalytic Ketone Reductions Using Biobeads for Miniaturized High Throughput Experimentation. New J. Chem. 2021, 45 (1), 32–35. 10.1039/D0NJ04889E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless K. B.; Amberg W.; Bennani Y. L.; Crispino G. A.; Hartung J.; Jeong K. S.; Kwong H. L.; Morikawa K.; Wang Z. M. The Osmium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Dihydroxylation: A New Ligand Class and a Process Improvement. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57 (10), 2768–2771. 10.1021/jo00036a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.