Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) had spread from China and, within 2 months, became a global pandemic. The infection from this disease can cause a diversity of symptoms ranging from asymptomatic to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome with an increased risk of vascular hyperpermeability, pulmonary inflammation, extensive lung damage, and thrombosis. One of the host defense systems against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). Numerous studies on this disease have revealed the presence of elevated levels of NET components, such as cell‐free DNA, extracellular histones, neutrophil elastase, and myeloperoxidase, in plasma, serum, and tracheal aspirates of severe COVID‐19 patients. Extracellular histones, a major component of NETs, are clinically very relevant as they represent promising biomarkers and drug targets, given that several studies have identified histones as key mediators in the onset and progression of various diseases, including COVID‐19. However, the role of extracellular histones in COVID‐19 per se remains relatively underexplored. Histones are nuclear proteins that can be released into the extracellular space via apoptosis, necrosis, or NET formation and are then regarded as cytotoxic damage‐associated molecular patterns that have the potential to damage tissues and impair organ function. This review will highlight the mechanisms of extracellular histone‐mediated cytotoxicity and focus on the role that histones play in COVID‐19. Thereby, this paper facilitates a bench‐to‐bedside view of extracellular histone‐mediated cytotoxicity, its role in COVID‐19, and histones as potential drug targets and biomarkers for future theranostics in the clinical treatment of COVID‐19 patients.

Keywords: COVID‐19, DAMPs, extracellular histones, histones, NETosis, NETs

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), an enveloped positive‐sense RNA virus, has infected more than 630 million people and caused 6.6 million deaths as of November 2022 [1]. Infection displays different symptoms ranging from asymptomatic to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [2, 3, 4].

An important host defense system is the formation of extracellular traps (ETs), which can be formed by several immune cells (e.g., eosinophils, monocytes, and neutrophils) [5]. During this process, intracellular components are released into the extracellular space, including cell‐free DNA (cfDNA), histones, and enzymes, such as neutrophil elastase (NE), and myeloperoxidase (MPO) in the case of ET formation by neutrophils [6]. The majority of neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) proteins, around 70%, consist of extracellular histones [7]. Histones are nuclear proteins that are essential for the structure and function of nucleosomes, the fundamental subunit of chromatin. The release of histones occurs through regulated processes (as in NET formation) or unregulated release (as in cell damage) and contributes to the neutralization of pathogens, including viruses [8].

During a SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, large numbers of viral particles are produced and released. Infected cells are recognized by the immune system, whereby viral RNA triggers the secretion of interferons and pro‐inflammatory cytokines (e.g., interferon‐I, interleukin (IL)‐1β, and IL‐18). Macrophages promote viral clearance and stimulate the recruitment of other immune cell types. Although the function of the immune system is to eliminate the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus and to protect the body, the homeostatic balance may shift during the fulminant phase and the immune system may become harmful to the host.

Such is the case when an extensive release of histones causes harmful effects on the host. Numerous studies have revealed elevated levels of NET components in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) patients [7, 9–13]. Extracellular histones act as damage‐associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that can cause cell activation [14] and cell death [8, 15] and can invoke an immune response by Toll‐like receptor (TLR)‐activation [16], nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2)/nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain‐like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) activation [17], and complement activation [18]. Neutralization of extracellular histones by complexation [8, 19–21] or proteolysis [22] has been shown to be beneficial in the reduction of tissue and organ damages. Therefore, histones are potential drug targets and biomarkers for future therapies.

Histone structure and nucleosome assembly

The nucleosome consists of two copies each of the core histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, bound to 147 base pairs of DNA [23, 24]. Additionally, linker histone H1 further compacts chromatin into 30 nm fibers and is positioned between two nucleosomes [25]. Core histones contain a histone fold domain, which comprises three α‐helices connected by two loops. This allows heterodimeric interactions between core histones through a so‐called handshake motif [24]. Heterodimeric interactions result in the formation of specific pairs, H3–H4 and H2A–H2B, whereby further interactions through four‐helix bundles are formed [23, 24]. Additionally, each core histone also contains N‐terminal tails of variable length that are subject to extensive posttranslational modifications. These modifications are implicated in transcriptional activation, gene silencing, chromatin assembly, and DNA replication [24].

Histone release into the extracellular environment

Histone release can be initiated via non‐programmed and programmed cell deaths [26]. Non‐programmed cell death, for example, necrosis, occurs by the initiation of the environment (e.g., inflammatory cytokines, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, or complement activation) and causes irreversible cell damage [26]. Programmed cell death, for example, apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis, leads to the leakage of cellular components into the environment, including extracellular histones. These processes occur extensively in diseases, including COVID‐19 infection. ET formation, which can occur entirely independent of cell death, is restricted to immune cells (e.g., monocytes, macrophages, eosinophils, and neutrophils) [5, 27]. This review will focus on NETs because neutrophils are the most abundant subtype (70%) of immune cells in the peripheral blood [28] and NETs are clinically relevant in many immune diseases (SLE, sepsis, and COVID‐19) [29, 30, 31]. Regardless of the route of externalization, extracellular histones are toxic to their environment.

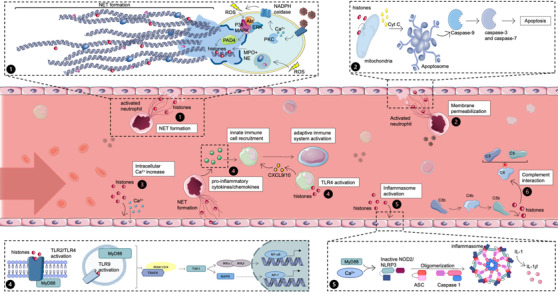

When a viral infection occurs, the life span of a neutrophil can be elongated by exposure to cytokines and chemokines [28]. During a viral infection, as seen, for example, by the respiratory syncytial virus and in HIV‐1 infection, neutrophil activation is induced by the interaction between viral antigens and pattern recognition receptors, such as TLR 4, 7, or 8 [32]. After stimulation, several downstream signaling molecules, such as phosphoinositide 3‐kinase, are activated. Intracellular calcium concentration increase results in protein kinase C activation. Via NADPH oxidase, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced [33]. The production of ROS leads to the induction and activation of protein arginine deiminase 4 (PAD4), a protein that converts positively charged arginine residues into neutral citrulline, which, in the case of core histone citrullination, results in chromatin decondensation [34, 35, 36]. In addition, NE and MPO are released from neutrophil granules into the neutrophil cytosol and translocated into the nucleus to promote further chromatin decondensation. As a result, chromatin is released into the cytosol, in which it binds to more granular and cytosolic proteins and is eventually released into the extracellular space [33, 35, 37, 38]. It was shown that the composition of NETs can vary depending on the stimulus, suggesting that the neutrophil will adapt its activation program to the type of invading pathogen [35, 39]. When DNA is released into the extracellular space, pathogens may become captured by it and destroyed by toxic proteins present in the DNA, including histones. These same activation pathways also play a role in COVID‐19 infections (Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.

Release and mechanisms of action of extracellular histones. (1.1) Histone release via NETosis. Activated neutrophils can undergo neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation to release their DNA and cytotoxic proteins, including histones, thereby killing pathogens. (1.2) Histone‐mediated membrane disruption. The direct effect of histones on plasma and mitochondrial membranes causes permeabilization. Cyt C is released from the mitochondria that lead to the formation of apoptosomes and activation of caspases. The cell will eventually undergo apoptosis. (1.3) Histone‐induced increase of intracellular calcium. Histones can actively bind to nonselective cation channels to rapidly increase calcium concentrations inside the cell leading to a disruption of calcium homeostasis. (1.4) Histone‐mediated pro‐inflammatory cytokine/chemokine release. Activation of Toll‐like receptors (TLR) receptors by histones triggers myD88 and TRAP. This cascade eventually leads to nuclear factor kappaB (NF‐κB) and activator protein 1 (AP‐1) transcription. (1.5) Histone‐mediated NOD2/nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain‐like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation. Extracellular histones can activate nucleotide binding oligomerization domain containing 2 (NOD2) via binding to TLR2/4, whereby the further establishment of the inflammasome is possible. Intracellular Ca2+ from the mitochondria or ER can enhance this pathway. (1.6) Complement‐mediated histone release. Extracellular histones are released when MAC lyses cells infected with the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus. Soluble complement protein C4 can be bound by extracellular histones, inhibiting complement proteins C3 and C5. Akt, protein kinase B; cyt C, cytochrome C; ERK, extracellular signal‐regulated kinases; IKK, IkappaB kinase; IL‐1, interleukin 1; IRAK, interleukin‐1 receptor–associated kinase; MAPK, mitogen‐activated protein kinases; MPO, myeloperoxidase; myD88, myeloid differentiation factor 88; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NE, neutrophil elastase; PAD4, protein arginine deiminase 4; PKC, protein kinase C; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TAK, transforming growth factor beta‐activated kinase‐1; TRAF, TNF receptor–associated factor. Source: Servier Medical Art was used to make these figures: smart.servier.com.

Although beyond the scope of this paper, the presence of elevated cfDNA concentrations in both plasma and urine have been shown in several studies to be a prognostic factor in, for example, sepsis and acute kidney injury [40], as is it markedly increased in COVID‐19 [9]. cfDNA by itself is recognized by TLR9, leading to cytokine production, inflammation, oxidative stress, and renal failure [41]. Extracellular DNA concentrations are rapidly resolved in vivo by nucleases like DNase I and Dnase1L3, where the increased digestion of cfDNA by DNase I was shown to increase the clearance of NETs and protected mice from sepsis, AKI and SLE [42]. The administration of DNAse I in SLE patients did however not result in changed serum markers of disease activity [41]. In a study by Thomas et al. [43], it was shown that in vivo administration of DNAse 1 in mice could prevent alveolar NET accumulation, thereby reducing NET‐induced pulmonary damage and improving arterial oxygen saturation.

Histone‐mediated mechanisms leading to tissue damage

Extracellular histones have been described as DAMPs that play an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, such as in sepsis [21, 44, 45], SLE [31, 46], myocardial infarction [27, 47], and, as recently discovered, in COVID‐19 [7, 9, 10, 48–53]. Extracellular histones exert cytotoxic effects through several mechanisms: (i) histone‐mediated membrane disruption, (ii) histone‐induced increase of intracellular calcium, (iii) histone‐induced TLR‐activation, (iv) histone‐mediated NOD2/NLRP3 activation, and (v) complement activation. Each of these mechanisms is discussed in further detail in the following sections (Fig. 1).

Histone‐mediated membrane disruption

Histones can have a direct effect on the mitochondrial and plasma membrane of cells (Fig. 1.2). Linker and core histones can permeabilize mitochondrial membranes and initiate the mitochondrial pathway of cell death characterized by mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, the release of cytochrome c, and APAF‐1 apoptosome‐mediated caspase activation [15, 54]. Extracellular histones can bind and destabilize plasma membranes. Recently, Silvestre‐Roig et al. [8] showed that histone H4 causes the lysis of vascular smooth muscle cells by forming pores in the plasma membranes of these cells. This effect is not exclusive to NET‐derived histones, as it was shown that histones released from damaged cells caused rapid cardiomyocyte damage during ischemia and reperfusion, independent of TLR4 [47].

Histone‐induced increase of intracellular calcium

Histones are capable of disturbing cellular calcium ion (Ca2+) homeostasis. It was shown that the exposure of breast cancer cells to histone H1 results in a rise of extracellular Ca2+ influx and intracellular Ca2+ release in breast cancer cells, but the source of Ca2+ was not clear [55]. Collier et al. [14] further investigated this topic and suggested that circulating histones activate a nonselective cation channel of the plasma membrane to rapidly increase endothelial cell cytosolic Ca2+ levels. This pathway does not engage the vasodilatory pathways through endothelial cells that are otherwise activated by released Ca2+ from intracellular stores [56]. Given the importance of Ca2+ homeostasis for normal cellular function, the disruption of this balance by histones has significant effect on a wide variety of tissues (Fig. 1.3).

Histone‐mediated TLR‐activation

Extracellular histones can activate the innate immune system by binding the TLRs TLR2, TLR4, or TLR9 and triggering the MyD88 signaling pathway. After TLR ligation by extracellular histones, myD88 interacts with IL‐1 receptor–associated kinase 4 (IRAK‐4) to form the myD88–IRAK‐4 complex. This complex recruits IRAK‐1 and IRAK‐2 resulting in IRAK phosphorylation and interacts with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor–associated factor 6 (TRAF 6). TRAF 6 induces the activation of TGF‐ß‐activated kinase‐1 (TAK‐1) and TAK‐1 binding proteins that lead to the activation of nuclear factor‐κB (NF‐κB) via phosphorylation of IkappaB kinase (IKK). Simultaneously, activator protein 1 is activated via mitogen‐activated protein kinases (MAPK) [57]. Eventually, these pathways lead to a rise in the levels of pro‐inflammatory factors, such as TNF‐α, IL‐6, and IL‐1β levels [16, 27, 58]. Due to the release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, more innate immune cells are recruited and eventually the adaptive immune system is activated. Additionally, histone H4 showed direct binding to TLR4 in complex with myeloid differentiation factor 2 on human monocytes in the peripheral blood. This interaction results in the release of chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10, which lead to the recruitment of leukocytes [27, 59] (Fig. 1.4).

Histone‐mediated NOD2/NLRP3 activation

NOD2, a member of the NLR family, can interact with multiple proteins and modulate immune responses in a stimulus‐dependent manner. By the recruitment of receptor‐interacting protein 2, the NF‐κB and MAPK‐pathway are activated, which increases IL‐1 levels [17]. Extracellular histones induce pyroptosis, a form of cell death that results in inflammation, via the NOD2 and NLRP3 pathways [17]. The NLRP3 inflammasome consists of a sensor (NLRP3), an adaptor (ASC or PYCARD), and an effector (caspase 1). Extracellular histones have been shown in vivo and in vitro to induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation [17, 60]. Allam et al. [60] illustrated that the histone‐induced activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome requires oxidative stress, whereby they focused specifically on histone H4. Activation of NLRP3 induces IL‐1 secretion and neutrophil recruitment, which enhances inflammation. Furthermore, NOD2 contains a predicted TRAF2‐binding motif in its NOD and is therefore associated with ER stress and inflammatory signaling. The involvement of this pathway was further confirmed when it was found that thapsigargin, a noncompetitive inhibitor of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), induces NOD‐dependent pro‐inflammatory signaling. This indicates that extracellular histones can lead to an increase in intracellular Ca2+ via the ER, which contrasts with the data by Collier et al. [14] (Fig. 1.5).

Histone‐mediated complement inhibition

Circulating soluble complement components have been detected in COVID‐19 patients, whereby plasma C5a and C3 are elevated and associated with a more severe disease state [61, 62]. Extracellular histones can bind to proteins of the complement system. Histone H3 and H4 have been shown to have a strong affinity for complement protein C4, as compared to histone H2A, H2B, and H1. Although the binding to histone did not impair the cleavage of C4 into C4a and C4b, the activities of components C3 and C5 were significantly inhibited. This effect was not reversed by the administration of a high concentration of C4, indicating that C4 is not the only component that is targeted by histones [18]. The inhibition of complement activation by extracellular histones requires further investigation (Fig. 1.6).

The role of DNA in histone‐mediated cytotoxicity

Although much in vitro data generated on the toxicity induced by histones has used purified preparations of these nuclear proteins, naturally released histone/DAMP pools likely contain DNA–histone complexes as well as free histones. The presence of DNA has important implications for the toxicity of histones. It was shown that although DNA protects histones from degradation by bacterial proteases, at the same time, the antimicrobial activity of histones is inhibited by DNA [63]. Marsman et al. showed in an in vitro study that histones when complexed to DNA were not cytotoxic, whereas DNA digestion restored their cytotoxicity toward endothelial cells, suggesting that DNA can shield the cytotoxic properties in histones. A similar shielding was proposed to explain an observed difference among the abilities of histones on the one hand or, on the other, intact NETs, chromatin, or nucleosome particles to trigger coagulation in vitro; when histones are complexed with DNA, they do not directly stimulate platelet‐dependent coagulation [64]. Collectively, these observations suggest that DNA may serve a physiological function in maintaining a balance between the beneficial antimicrobial activity of extracellular histones and cytotoxicity toward host cells [63]. The presence of polyanions, like DNA or other engineered biomolecules, therefore opens up potential therapeutic options to treat histone‐mediated cytotoxicity (see also the “Treatment options to prevent excessive extracellular histone‐induced damage” section).

Histone‐mediated events in COVID‐19 patients

The damaging mechanisms initiated by histones as described before play a key role during the onset and progression phase of COVID‐19 disease. Particularly, COVID‐19‐associated coagulopathy and ARDS have been linked to circulating histones [49, 50]. This causative role for histones and their clinical involvement in the progression of COVID‐19 disease is further substantiated by studies from our group [10] and by others [49], where histone levels in cohorts of adult COVID‐19 patients were studied and it was found that the admission levels of histones correlated with the severity of COVID‐19 disease (i.e., mild, moderate, critical, or non‐survivor patients).

The release of extracellular histones into the bloodstream as is seen in COVID‐19 can be attributed to both virus‐ and host‐induced damage (Fig. 2). In the following sections, a detailed description of these two events will be given.

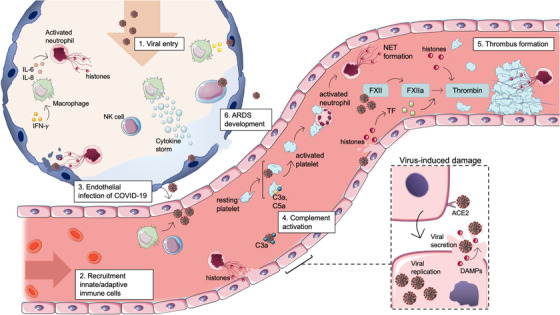

Fig. 2.

The role of extracellular histones during early and severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) infection. Binding of the coronavirus spike protein to the human angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE‐2) receptor allows for the entry of the virus into the target host cell. After entering the cytoplasm and uncoating of the viral particle, viral gene expression is ensued. Viral particles, including histones, are released during apoptosis or necrosis. (2.1) When the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus enters the upper respiratory tract, innate immune cells are activated by infected respiratory cells. Alveolar macrophages secrete pro‐inflammatory cytokines to activate neutrophils, which undergo NETosis. In later phases of the infection, the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus infects the lower respiratory tract, and the adaptive immune system is activated. (2.2) Recruitment of innate and adaptive immunes cells to the site of infection. Secretion of pro‐inflammatory cytokines by alveolar macrophages results in the recruitment of other macrophages, invasion of neutrophils and natural killer (NK) cells. (2.3) Due to activation of neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, infected epithelial cells are cleared via secretion of cytotoxic components. However, these components damage the epithelial and endothelial layer of the alveoli and blood vessel wall, leading to a spread of the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus toward endothelial cells. (2.4) Infected endothelial cells initiate the recruitment of platelets and neutrophils to the microvasculature. Activated platelets can trigger neutrophils to form NETs. During a viral infection, platelets can engulf viral particles mediated by TLR7, triggering complement C3‐dependent NET formation. (2.5) Coagulation can be initiated in different ways during COVID‐19 infection. NETs can form a surface for thrombin formation, whereas histones can also directly stimulate the activation of prothrombin by activated factor X (FXa). Furthermore, the coagulation pathway can be triggered directly by viral damage or by tissue factor exposure. (2.6) Newly recruited immune cells secrete high levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines/chemokines that, when excessive, cause a cytokine storm, leading to epithelial and endothelial damage. Over time, the alveolar permeability barrier will disrupt, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) will develop. DAMPs, damage‐associated molecular patterns; FVa, activated factor V; PAMPs, pathogen‐associated molecular patterns; TLR, Toll‐like receptor. Source: Servier Medical Art was used to make these figures: smart.servier.com.

Histone release during virus‐induced damage

After its most likely route of infection, through the upper respiratory tract, the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus will initially replicate in the epithelial cells of the nasal cavity. The binding of the coronavirus spike protein to the human angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 receptor allows for cellular entry. After entering the cytoplasm and uncoating the viral particle, viral gene expression ensued [65, 66]. To increase genome replication in the host cell, the SARS‐CoV‐2 protein encoded by ORF8 (ORF8) exhibits histone mimicry that matches a region within the histone H3 N‐terminal tail [67]. In severe cases, the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus will reach the alveoli of the lower respiratory tract and invade the epithelial lining of the alveoli [68, 69]. After infection, large numbers of viral particles are produced and released, and infected cells will undergo necrosis. Together with the viral particles that are released when a cell undergoes necrosis, pathogen‐associated molecular patterns and DAMPs are then released, including histones. Extracellular histones released into the extracellular space can activate surrounding alveolar cells and immune cells via several mechanisms that trigger inflammation and contribute to the onset of a vicious circle of histone‐mediated direct damage, leading to histone release.

Histone release during host‐induced damage

When the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus reaches the conducting airways, infected cells activate innate immune cells [66]. Viral RNA released into the cytoplasm of epithelial cells triggers the secretion of interferons and pro‐inflammatory cytokines, for example, interferon‐I, IL‐1β, and IL‐18, which attract alveolar macrophages [69]. Macrophages promote viral clearance and, in their turn, secrete more pro‐inflammatory and chemotactic cytokines, including IL‐6 and IL‐8 (Fig. 2.1). These responses result in the recruitment of other immune cell types, including neutrophils, natural killer cells, and monocytes [70] (Fig. 2.2).

In later phases of the infection, when the virus is located in the lower respiratory tract, more immune cells are recruited to promote viral clearance. Although the function of the immune system is to eliminate the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus and to protect the body, the homeostatic balance may shift during the fulminant phase and the immune system may become harmful to the host in the fulminant phase. In severe COVID‐19 infections, the massive infiltration of neutrophils has been observed and postmortem lung specimens of patients who died from COVID‐19 revealed the presence of NETs in the lungs [71, 72]. NETs contribute to lung injury by damaging epithelial and endothelial cells via the secretion of many effector compounds, such as MPO, NE, and histones [69]. Especially, histones H3 and H4 are cytotoxic to endothelial and epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo [21]. In vitro studies revealed that the presence of all extracellular histone isotypes can lead to the production of cytokines (TNF‐α, IL‐6, and IL‐10), stimulate formation of NETs, and increase calcium influx in immune and endothelial cells [22, 73]. In vivo studies with histone, administration resulted in cytokine release, endothelial damage, activation of coagulation, and lung injury in animal trauma models [21, 22, 73]. The damage caused to the epithelial and endothelial cells by the virus and the immune system leads to the spread of infection to blood vessels surrounding the alveoli (Fig. 2.3).

Viral diseases, such as COVID‐19, involve the exposure of active tissue factors (TFs) and recruitment of platelets and neutrophils to the microvasculature. Platelets can become activated and they can trigger neutrophils to form NETs via αIIb integrin and neutrophil αM integrin. During a viral infection, for example, influenza A, platelets can engulf viral particles mediated by TLR7 [74], triggering complement C3‐dependent NET formation. Additionally, viral infections can trigger NET formation directly [75] (Fig. 2.4). NETs may have a direct impact on coagulation through their associated externalized histones. During hemostasis, prothrombin is activated by the prothrombinase complex comprising activated factor X (FXa), activated cofactor V (FVa), negatively charged phospholipids, and calcium. In the presence of extracellular histones, FXa may directly cleave prothrombin to form thrombin, even in the absence of FVa or a lipid surface. The binding of histones to prothrombin fragment 1 (F1) and fragment 2 (F2) does not require the presence of suitable phospholipid surfaces to anchor FXa [76]. This effect may further enhance the formation of thrombin, contributing to immunothrombosis in COVID‐19 patients [75] (Fig. 2.5). Enhanced thrombin generation in COVID‐19 patients was demonstrated by increased levels of circulating thrombin: antithrombin complexes in these patients [10]. In addition, coagulation can directly be triggered by virus‐induced tissue damage and subsequent exposure to TF (extrinsic pathway) and activation via a coagulation factor XII (intrinsic pathway) [77]. It has been proposed that TF plays a major role in the histone‐induced hypercoagulable state of COVID‐19 patients. Recent studies showed higher soluble TF plasma levels and increased TF expression on circulating neutrophils in COVID‐19 patients [78]. Furthermore, both TF activity and TF antigen were increased in blood monocytes in the presence of extracellular histones, whereby histones contributed to pronounced and persistent monocyte alterations [79, 80]. Moreover, endothelial cells exposed to extracellular histones supported more thrombin formation than untreated cells, an effect that could be abrogated by a TF‐neutralizing antibody [81] (Fig. 2.5). Collectively, a prothrombotic shift in the hemostatic balance occurs, which is based on ischemic events that further contribute to a loss of organ function in COVID‐19 patients.

Additionally, newly recruited immune cells secrete high levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, including IL‐6, IL‐2, IL‐7, TNF, and C‐reactive protein (CRP) [82, 83, 84]. When the secretion of the cytokine release is uncontrolled and excessive, this can lead to a so‐called cytokine storm. This cytokine storm can also be observed in COVID‐19 patients, which leads to unwanted damage [85, 86]. A recent meta‐analysis showed that IL‐6, CRP, and neutrophils are good indicators of severity and mortality in COVID‐19 [87]. Macrophages and neutrophils are believed to cause respiratory epithelial and endothelial damage in COVID‐19 patients and contribute to the development of ARDS [30, 88, 89]. In vivo studies revealed that the administration of histones caused a dose‐dependent disruption of the alveolar permeability in rodents [90]. This process can contribute to the pathogenesis of ARDS and COVID‐19 (Fig. 2.6).

NET components as biomarkers for COVID‐19 early diagnosis

NET components, including extracellular histones, may be used as biomarkers in COVID‐19. Numerous studies have measured elevated levels of NE, histone–DNA, MPO–DNA, NE–DNA, cfDNA, and (citrullinated) histone H3 in blood, plasma, and tissues to detect the presence of NETs in COVID‐19 patients [3, 7, 9, 11–13] (Table 1). Elevated levels of the histone–DNA complex were associated with ICU admission, increased body temperature, lung damage, and increased the expression of IL‐6 and IL‐8 [3, 13, 91]. When looking at different disease stages of COVID‐19, citrullinated extracellular histone H3 (cit‐H3) was present in 73% (38 out of 52 cases) of mild/moderate COVID‐19 patients, which suggests NET formation and its resultant formation of extracellular histone in COVID‐19 to proceed predominantly via the PAD4 route [10]. This observation is supported by reports of increased cit‐H3 levels in COVID‐19 patients [3, 12, 13]. Clinically, these are significant findings as the pharmacologic inhibition of this route might represent a novel way to treat COVID‐19 patients [92]. Furthermore, it was found that the severity of COVID‐19 disease correlated with the levels of histone levels found in the blood plasma of COVID‐19 patients, whereby increasing levels were found going from mild disease to non‐survivor [10, 49]. Circulating cit‐H3 in combination with MPO, measured between day 1 and day 3 after inclusion, could predict the risk of 28‐day mortality [51]. Histone‐quantitative ELISA methods, using antibodies reacting with (citrullinated) histone H3 and histone–DNA complex, performed at the time of admission to the ICU have a prognostic value and can discriminate among healthy controls, COVID‐19 patients hospitalized at ICU, non‐survivors, and even those hospitalized with thrombosis [53, 93–95]. Immunohistochemistry revealed cit‐H3‐positive alveolar septa, blood vessel walls, and intravascular thrombi [96]. In vitro studies showed that neutrophils executed NET formation when exposed to the plasma of progressive/severe COVID‐19 patients [10]. To further explore the association between NET formation and epithelial damage, Veras et al. [52] showed that neutrophils, when incubated with SARS‐CoV‐2, induced the apoptosis of cultured A549 lung epithelial cells. This result underscores the involvement of neutrophils in the process that leads to lung damage following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Becker et al. [97] studied the role of NETs in COVID‐19 in a Syrian hamster model and observed pulmonary lesions that were characterized by interstitial inflammation, type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, edema, fibrin formation and infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils. Their study showed that NETs play a role in vascular pathology already during the early phase of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Given the associations that were found, NET components might prove useful as biomarkers to monitor the state of disease in COVID‐19 patients and, moreover, there is a potential role for NET‐biomarkers in clinical decision‐making [53].

Table 1.

Summary of clinical data obtained from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) patients, and results of in vitro experiments and in vivo COVID‐19 experiments

| Clinical data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarker(s) | Patient sample | Results | References |

| MPO | Plasma, tissue (lung) | Elevated levels, positive staining, indication of NET formation | [7, 96] |

| MPO–DNA complex | Plasma, serum, tissue (coronary artery) | Elevated levels, indication of NET formation | [7, 11–13] |

| NE–DNA complex | Plasma | Elevated levels, indication of NET formation | [13] |

| cfDNA | Plasma, serum | Respiratory requirement, short‐term mortality, correlated with pro‐inflammatory innate immune system (leukocytes, CRP), activation of extrinsic pathway of coagulation, 30‐day mortality predictor, higher male‐to‐female ratio | [3, 7, 9, 12, 13, 121] |

| DNase activity | Plasma, serum | Lower activity in males compared to females, potential risk factor combined with lower LL‐37 levels | [121] |

| Extracellular histone H3 (±cit) | Plasma, serum, tissue (lung, coronary artery) | Respiratory requirement, short‐term mortality, correlated with pro‐inflammatory innate immune system and NET components (cfDNA and NE), proteolysis, association with thromboembolic events, higher presence in moderate/severe patients | [3, 7, 9–13, 96] |

| NE | Plasma | Respiratory requirement, short‐term mortality, correlated with pro‐inflammatory innate immune system and components of the coagulation system (fibrinogen) | [3, 7, 9, 13] |

| Neutrophils/Neutrophil‐related transcripts | Blood | Activated neutrophils, neutrophil covered thrombocytes, CD15+ neutrophils showed increase in nuclear DNA and NE compared to controls, 25‐fold increase in DEFA1, whereas 3–5 fold reduction in TCR | [13, 122] |

| MPO‐cit‐H3 | Blood | Decreased between day 1 and day 3 in survivors, remained stable in non‐survivors, higher NET concentration compared to controls | [51, 52] |

| In vitro | |||

| Biological process | Method | Results | References |

| NET formation | Neutrophils stimulated with patient serum | Serum of progressive/severe COVID‐19 patients induced NET formation positive for DNA, cit‐H3, NE, and MPO | [10] |

| NET formation | Healthy neutrophils stimulated with SARS‐CoV‐2 | Longer branch lengths, more efficient to produce NETs | [52] |

| In vivo | |||

| Biological process | Model | Results | References |

| NET formation | Syrian golden hamsters infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 | Development of vascular lesions and NET formation, NETs present during early infection | [97] |

Abbreviations: cfDNA, cell‐free DNA; CRP, C‐reactive protein; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NE, neutrophil elastase; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps.

Clinical perspective

Over the past years, extracellular histones have been studied as possible targets for the pharmacological treatment of several pathologies (Table 2). In this context, the physiological downregulation of extracellular histones has not been well described, despite the existence of several potentially important negative feedback loops, of which CRP, activated protein C (APC), and NE have received attention. Of relevance, the glycocalyx forms a natural barrier that has been described to prevent extracellular histone damage to multiple types of cells [98]. Given the role that extracellular histones play in COVID‐19 disease, potential drug candidates known to bind and neutralize histones, for example, heparins, peptides, and small polyanions, are currently also under investigation as a pharmacological treatment of COVID‐19. The previously mentioned feedback loops and drug options will be further discussed in the following sections.

Table 2.

Current support for targeting of extracellular histones as viable means of therapy

| Natural inhibitors | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|

| CRP | Binding of histone H4, probably all histones | [100, 101] |

| APC | Cleavage of histones | [27, 103, 104, 123] |

| NE | Cleavage of histones | [106] |

| Glycocalyx | Trapping of histones | [102, 124] |

| Treatment options | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|

| Heparins | ||

| Heparin | Binding of histones, interaction with the coagulation system | [108, 109, 110] |

| LMWH | Binding of histones, lower interaction with the coagulation system | [19, 108–112] |

| Small polyanions | Electrostatic interaction with histones | [113] |

| Peptides | Binding of histones | [8, 20, 114]) |

| Clinical trials | Clinical Identifier | |

|---|---|---|

| Annexin A5 | Inhibition of the procoagulant phosphatidylserine in severe COVID‐19 patients at ICU and medium care to disrupt endothelial cell activation, NET formation (e.g., histone release) and coagulation | NCT04748757, EudraCT 2021‐002200‐12 |

| Low anticoagulant heparin M6229 | Neutralization of extracellular histones in COVID‐19 patients with sepsis at ICU | NCT05208112 |

| Dociparstat sodium (DSTAT) | Binding of histones, reduced interaction with the coagulation system | NCT04389840 |

Abbreviations: APC, activated protein C; COVID, coronavirus disease 2019; CRP, C‐reactive protein; LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin; NE, neutrophil elastase; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps.

Natural inhibitors of extracellular histones

Two important mechanisms to downregulate the cytotoxicity of extracellular histones are neutralization by binding to histones and enzymatic proteolysis of histones, resulting in their degradation. These two essentially different regulatory processes are described in the following sections.

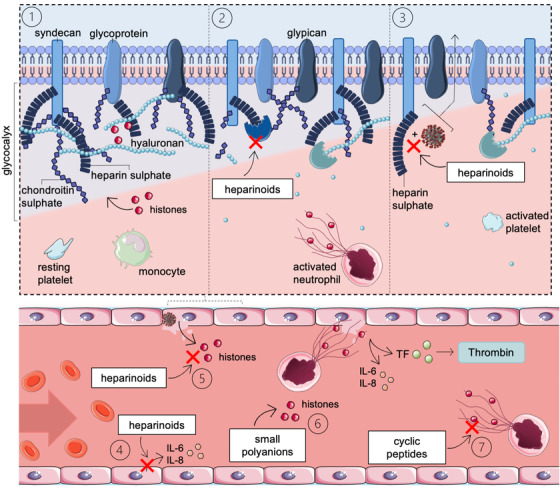

Histone‐neutralization by complex formation

CRP is an important mediator of inflammation, which can be released via the IL‐6 pathway that is activated by immune and nonimmune cells. In addition to its biomarker status, CRP is more and more appreciated as an active participant in inflammation [99]. CRP, the synthesis of which is increased by extracellular histones, protects against the cytotoxic activity and the procoagulant and platelet‐activating activity of extracellular histones in vitro and in vivo [100, 101]. Recent research shows that CRP can bind directly to histone H4 and reduce its cytotoxicity and thus can potentially aid to disrupt the vicious cycle in COVID‐19 patients [101]. Similar to CRP, binding to the glycocalyx can reduce extracellular histone cytotoxicity (Fig. 3.1). The glycocalyx forms a natural barrier between the blood and tissues that can bind histones. Therefore, it represents a protective barrier one may consider to be a natural buffer that protects from excessive histone‐mediated cytotoxicity. When exposed to plasma, as occurs in several diseases (e.g., SLE and sepsis), extracellular histones bind to the glycocalyx by electrostatic interactions. Degradation of the glycocalyx, which can occur in severe disease states of sepsis and COVID‐19 infection, will make the underlying endothelial cell layer more vulnerable to the cytotoxicity of extracellular histones [102].

Fig. 3.

Working mechanisms of unfractionated heparin (UFH)/low‐molecular weight heparin (LMWH) to prevent cellular damage in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) patients. (3.1) The glycocalyx forms a natural barrier between blood and tissues that can reduce extracellular histone cytotoxicity. Histones are attracted to the glycocalyx through electrostatic interactions. Upon glycocalyx degradation, as occurs in severe disease states, mobilized extracellular histones can damage the underlying endothelium. (3.2) UFH/LMWH inhibits heparinase activity, preventing heparan sulfate degradation. (3.3) UFH/LMWH inhibits cell attachment of spike glycoproteins (SGPs) from viruses via heparin sulfate. (3.4) UFH/LMWH inhibits various pro‐inflammatory pathways. For example, LPS‐stimulated endothelial cells increase interleukin (IL)‐6 and IL‐8, whereas a UFH treatment after LPS‐stimulation reduced the pro‐inflammatory cytokine levels. (3.5, 3.6, 3.7) UFH/LMWH, small polyanions and cyclic peptides can neutralize extracellular histones by binding. TF, tissue factor. Source: Servier Medical Art was used to make these figures: smart.servier.com.

Natural inhibitors that can neutralize extracellular histones by proteolysis

The anticoagulant APC expresses its anti‐inflammatory activity by binding the endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) with subsequent proteolytic activation of protease‐activated receptor 1 [103]. APC can also proteolyze extracellular histones, thereby destroying their cytotoxic activity [21, 27]. During SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, circulating levels of soluble EPCR are elevated [104]. Soluble EPCR can bind APC and cause local APC depletion at sites of inflammation [99]. To translate the protective activities of APC, recombinant APC (Xigris) was marketed for the treatment of sepsis patients. This drug was, however, withdrawn from the market in 2010 due to a lack of efficacy in the heterogenous sepsis population [105]. Recombinant APC could be revisited as a drug to treat COVID‐19 patients. A recent study illustrated that APC inhibits the pro‐inflammatory signaling effects of poly(I:C), a synthetic analog of viral double‐stranded RNA that is used to mimic a viral infection. It was demonstrated that APC inhibits key events of NET formation: histone H3 citrullination, and translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [103].

Similar to APC, NE can reduce the cytotoxicity of histones by proteolytic cleavage. Previously, we showed a positive correlation between circulating levels of cleaved histone H3 and NE in severe COVID‐19 patients, suggesting that NE downregulates extracellular histones in the plasma of COVID‐19 patients [7]. Zhou et al. showed that NE cleaves histones and that the peak of histone degradation occurs during NET formation [106]. These two studies indicate that NE‐catalyzed proteolysis represents a mechanism to dampen inflammation. NE, therefore, is a potential biomarker that could have additional therapeutic potential in COVID‐19.

Treatment options to prevent excessive extracellular histone‐induced damage

Histones are highly positively charged. Hence negatively charged molecules can bind extracellular histones and thereby neutralize their cytotoxic properties. Heparin, a negatively charged polysaccharide, is known for its anticoagulant, anti‐inflammatory, and anticomplement properties [107]. Besides these properties, Wildhagen et al. showed that heparin also blocks the cytotoxic properties of extracellular histones [19]. In COVID‐19 patients, the anticoagulants unfractionated heparin (UFH) and/or low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) could therefore have beneficial effects through multiple mechanisms. First, UFH/LMWH can inhibit heparinase activity, preventing the degradation of heparan sulfate, the most abundant sulfate in the glycocalyx. UFH/LMWH protects the endothelial barrier and prevents the formation of leaky blood vessels that contribute to lung complications, as observed in ARDS (Fig. 3.2). Second, UFH/LMWH inhibits pro‐inflammatory pathways via various mechanisms as discovered by in vitro and in vivo experiments, and via clinical trials (Fig. 3.4) [108, 109]. For example, LPS stimulation of endothelial cells increases the levels of IL‐6 and IL‐8, whereas a UFH treatment after LPS stimulation reduces the pro‐inflammatory cytokine levels [109].

Third, UHF/LMWH can inhibit cell attachment through viral spike glycoproteins (SGPs), including those of SARS‐CoV‐2, via the sulfated sugars of heparin (Fig. 3.3). Tandon et al. [110] illustrated, using a third‐generation lentivirus pseudotyped with SARS‐CoV‐2 SGP, that UFH (IC50, 5.99 μg/L) and LMWH (enoxaparin, IC50, 108 μg/L) can inhibit SGP binding to HEK293T cells.

Lastly, UFH/LMWH neutralizes the cytotoxic effects of extracellular histones in COVID‐19 patients (Fig. 3.5). In severe COVID‐19 patients, the anticoagulant function of heparin can be undesirable. Our group showed that the removal of the anticoagulant fraction from UFH results in a low anticoagulant heparin fraction that can neutralize histone‐mediated cytotoxicity as well as UFH in vitro and in vivo [19]. Currently, a phase I/IIa clinical trial investigates this low‐anticoagulant fraction of heparin, named M6229, in septic COVID‐19 patients hospitalized at the ICU (trial identifier NCT05208112). Hogwood et al. showed that heparins that have lost anticoagulant activity by selective desulfation, reduce the histone‐induced generation of inflammatory markers (IL‐6, IL‐8, and TF) in whole blood of healthy volunteers [111]. Currently, a phase II/III clinical trial evaluates the safety and efficacy of desulfated heparins in patients with acute lung injury due to COVID‐19 (trial identifier NCT04389840) [112].

Small polyanions are negatively charged compounds of 0.9–1.4 kDa. Meara et al. [113] reported that small polyanions consisting of di‐ and trisaccharides of hexoses are as effective as UFH in neutralizing histone‐mediated cytotoxicity in HMEC‐1 and red blood cells. Furthermore, in vivo data showed that small polyanions can inhibit histone‐mediated and NET‐associated disease states, including sepsis [113]. Although small polyanions are not tested in COVID‐19‐related models, they could prove beneficial to severe COVID‐19 patients and improve clinical outcomes.

Rationally designed cyclic peptides are a novel treatment option to prevent histone‐mediated cytotoxicity [114]. Silvestre‐Roig et al. [8] illustrated that the N‐terminal region of histone H4 is responsible for the H4–membrane interaction. To inhibit this interaction, a cyclic peptide (HIPe) was designed to prevent histone‐mediated cell death. In vitro and in vivo results showed reduced cytotoxicity of histone H4 [47]. Following a similar approach, Schumski et al. [20] focused on the N‐terminal region of histone H2A. Electrostatic interactions between the arginine and lysine residues (positively charged) of histone H2A and aspartate and glutamate residues (negatively charged) of the peptide (CHIP) promoted stable complex formation. In vitro and in vivo experiments showed that CHIP specifically prevented the interaction between monocytes and NETs, diminished arterial adhesion of neutrophils and monocytes, and drastically reduced histone‐mediated atherosclerotic lesion sizes. Given these recent findings, blocking histone cytotoxicity with cyclic peptides in COVID‐19 patients could be beneficial during progressive/severe stages of the disease. Therefore, cyclic peptides should not be overlooked as a potential treatment option for COVID‐19.

Lastly, clinical trials have been initiated that study the pro‐inflammatory and procoagulant phosphatidylserine (PS) in COVID‐19 patients by the intravenous administration of annexin A5 (anxA5) (trial identifiers NCT04748757 and EudraCT number, 2021‐002200‐12). AnxA5 is a human protein that binds PS with high affinity and that inhibits PS‐dependent thrombin generation [115]. Recently, it was shown that COVID‐19 patients with acute pulmonary embolisms have circulating procoagulant microparticles that express PS [116]. Another study demonstrated that circulating microparticles from COVID‐19 patients trigger NET formation, for example, the release of histones, through the activation of endothelial cells [117]. Treating the microparticles with anxA5 annihilated their effects on endothelial cell activation and histone release, indicating that anxA5 may disrupt the amplifying loop connecting endothelial cell activation, NET formation, and coagulation.

Conclusions and future perspective

As early as 1958, Hirsch discovered that histones are not only essential for chromatin structure but are also able to protect the host from bacteria when released into the extracellular space [118]. Over the years, it was shown that extracellular histones possess valuable properties in immune responses against several pathogens (e.g., bacteria, viruses, and fungi). Different histone‐mediated molecular processes are described in this review, such as membrane disruption, intracellular calcium influx, TLR activation, and inflammasome activation. These processes are rather indiscriminate as they not only protect the host against pathogens but at the same time, they can be harmful to the host cells when they occur excessively. During disease states, as seen in SLE, sepsis and COVID‐19 patients, disproportionate histone release causes damage to healthy tissues and organs and, in severe cases, contributes to mortality. COVID‐19 is a novel histone‐mediated disease, whereby extracellular histones are linked to critical complications such as ARDS and immunothrombosis. Assessment of levels of circulating histone or NET‐markers was shown to have predictive value in COVID‐19 patients as they associated with clinical outcomes. A potential role for histones in clinical decision‐making may therefore exist and could enable a clinician to adapt their treatment to the need of individual patients. Therefore, current (e.g., UFH/LMWH, peptides, and polyanions) and novel (e.g., Annexin A5, M6229, or DSTAT) histone inhibitors could represent promising drugs in a clinical setting. These drugs can possibly be combined with current immune‐ or antithrombotic therapeutics. Given that extracellular histones are a significant part of our immune system, they could become an important drug target in the treatment of viral‐ and immune diseases. As we have learned from the current COVID‐19 pandemic and also from the past outbreaks of MERS and SARS, vaccine and drug development for a specific viral infection requires tremendous financial support, effort, and time. Thus, broad‐spectrum therapeutic methods, such as host‐directed therapy to combat diseases caused by infection with SARS‐CoV‐2 and other coronaviruses, represent an attractive alternative approach. As described in this review, viral infections can induce the NET formation and histone release that may lead to severe ARDS—the major cause of mortality of coronavirus diseases, including MERS, SARS, and COVID‐19 [119, 120]. Histones represent promising drug targets and biomarkers for viral‐induced ARDS. Therefore, the newly developed drugs and diagnostic tools that target extracellular histones can be promptly used as an alternative treatment for the next outbreak of the virus‐induced ARDS, whereas a specific therapeutic approach (vaccines and drugs) is being developed in parallel.

Conflict of interest

CR and GN are inventors of a patent owned by the Maastricht University on the use of non‐anticoagulant heparin to treat histone‐mediated inflammatory disease. KW and GN are inventors of a patent filed by the Maastricht University to use peptides to target extracellular histones H4 and H2A.

Acknowledgment

This study was financially supported by a grant from the Netherlands Thrombosis Foundation (2016‐01, to GN).

de Vries F, Huckriede J, Wichapong K, Reutelingsperger C, Nicolaes GAF. The role of extracellular histones in COVID‐19. J Intern Med. 2023;293:275–292.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation 2013 . WHO Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Dashboard . The United Nations, https://covid19.who.int. Accessed 30 November 2022

- 2. Gibson PG, Qin L, Puah SH. COVID‐19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): clinical features and differences from typical pre‐COVID‐19 ARDS. Med J Aust. 2020;213(2):54–6 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ng H, Havervall S, Rosell A, Aguilera K, Parv K, von Meijenfeldt FA, et al. Circulating markers of neutrophil extracellular traps are of prognostic value in patients with COVID‐19. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:988–94 ATVBAHA120315267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arcanjo A, Logullo J, Menezes CCB, de Souza Carvalho Giangiarulo TC, Dos Reis MC, et al. The emerging role of neutrophil extracellular traps in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (COVID‐19). Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):19630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Castanheira FVS, Kubes P. Neutrophils and NETs in modulating acute and chronic inflammation. Blood. 2019;133(20):2178–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huckriede J, de Vries F, Hultstrom M, Wichapong K, Reutelingsperger C, Lipcsey M, et al. Histone H3 cleavage in severe COVID‐19 ICU patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:694186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silvestre‐Roig C, Braster Q, Wichapong K, Lee EY, Teulon JM, Berrebeh N, et al. Externalized histone H4 orchestrates chronic inflammation by inducing lytic cell death. Nature. 2019;569(7755):236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huckriede J, Anderberg SB, Morales A, de Vries F, Hultstrom M, Bergqvist A, et al. Evolution of NETosis markers and DAMPs have prognostic value in critically ill COVID‐19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):15701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Busch MH, Timmermans S, Nagy M, Visser M, Huckriede J, Aendekerk JP, et al. Neutrophils and contact activation of coagulation as potential drivers of COVID‐19. Circulation. 2020;142(18):1787–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blasco A, Coronado MJ, Hernandez‐Terciado F, Martin P, Royuela A, Ramil E, et al. Assessment of neutrophil extracellular traps in coronary thrombus of a case series of patients with COVID‐19 and myocardial infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;6:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zuo Y, Zuo M, Yalavarthi S, Gockman K, Madison JA, Shi H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps and thrombosis in COVID‐19. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;51:446–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leppkes M, Knopf J, Naschberger E, Lindemann A, Singh J, Herrmann I, et al. Vascular occlusion by neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID‐19. EBioMedicine. 2020;58:102925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Collier DM, Villalba N, Sackheim A, Bonev AD, Miller ZD, Moore JS, et al. Extracellular histones induce calcium signals in the endothelium of resistance‐sized mesenteric arteries and cause loss of endothelium‐dependent dilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019;316(6):H1309–H22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cascone A, Bruelle C, Lindholm D, Bernardi P, Eriksson O. Destabilization of the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes by core and linker histones. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Munemasa Y. Histone H2B induces retinal ganglion cell death through toll‐like receptor 4 in the vitreous of acute primary angle closure patients. Lab Invest. 2020;100(8):1080–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shi CX, Wang Y, Chen Q, Jiao FZ, Pei MH, Gong ZJ. Extracellular histone H3 induces pyroptosis during sepsis and May Act through NOD2 and VSIG4/NLRP3 pathways. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qaddoori Y, Abrams ST, Mould P, Alhamdi Y, Christmas SE, Wang G, et al. Extracellular histones inhibit complement activation through interacting with complement component 4. J Immunol. 2018;200(12):4125–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wildhagen KC, Garcia de Frutos P, Reutelingsperger CP, Schrijver R, Areste C, Ortega‐Gomez A, et al. Nonanticoagulant heparin prevents histone‐mediated cytotoxicity in vitro and improves survival in sepsis. Blood. 2014;123(7):1098–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schumski A, Ortega‐Gomez A, Wichapong K, Winter C, Lemnitzer P, Viola JR, et al. Endotoxinemia accelerates atherosclerosis through electrostatic charge‐mediated monocyte adhesion. Circulation. 2021;143(3):254–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu J, Zhang X, Pelayo R, Monestier M, Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, et al. Extracellular histones are major mediators of death in sepsis. Nat Med. 2009;15(11):1318–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen R, Kang R, Fan XG, Tang D. Release and activity of histone in diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Talbert PB, Henikoff S. Histone variants at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2021;134(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marino‐Ramirez L, Kann MG, Shoemaker BA, Landsman D. Histone structure and nucleosome stability. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2005;2(5):719–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Biterge B, Schneider R. Histone variants: key players of chromatin. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;356(3):457–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang J, Hu S, Bian Y, Yao J, Wang D, Liu X, et al. Targeting cell death: pyroptosis, ferroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis in osteoarthritis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:789948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Y, Wan D, Luo X, Song T, Wang Y, Yu Q, et al. Circulating histones in sepsis: potential outcome predictors and therapeutic targets. Front Immunol. 2021;12:650184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(3):159–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barnes BJ, Adrover JM, Baxter‐Stoltzfus A, Borczuk A, Cools‐Lartigue J, Crawford JM, et al. Targeting potential drivers of COVID‐19: neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2020;217(6):e20200652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li RHL, Tablin F. A comparative review of neutrophil extracellular traps in sepsis. Front Vet Sci. 2018;5:291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pieterse E, Hofstra J, Berden J, Herrmann M, Dieker J, van der Vlag J. Acetylated histones contribute to the immunostimulatory potential of neutrophil extracellular traps in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;179(1):68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hiroki CH, Toller‐Kawahisa JE, Fumagalli MJ, Colon DF, Figueiredo LTM, Fonseca B, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps effectively control acute Chikungunya virus infection. Front Immunol. 2019;10:3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(2):134–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nagar M, Tilvawala R, Thompson PR. Thioredoxin modulates protein arginine deiminase 4 (PAD4)‐catalyzed citrullination. Front Immunol. 2019;10:244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jorch SK, Kubes P. An emerging role for neutrophil extracellular traps in noninfectious disease. Nat Med. 2017;23(3):279–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu X, Arfman T, Wichapong K, Reutelingsperger CPM, Voorberg J, Nicolaes GAF. PAD4 takes charge during neutrophil activation: impact of PAD4 mediated NET formation on immune‐mediated disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(7):1607–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mesa MA, NETosis Vasquez G.. Autoimmune Dis. 2013;2013:651497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Delgado‐Rizo V, Martinez‐Guzman MA, Iniguez‐Gutierrez L, Garcia‐Orozco A, Alvarado‐Navarro A, Fafutis‐Morris M. Neutrophil extracellular traps and its implications in inflammation: an overview. Front Immunol. 2017;8:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dwyer M, Shan Q, D'Ortona S, Maurer R, Mitchell R, Olesen H, et al. Cystic fibrosis sputum DNA has NETosis characteristics and neutrophil extracellular trap release is regulated by macrophage migration‐inhibitory factor. J Innate Immun. 2014;6(6):765–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Celec P, Vlkova B, Laukova L, Babickova J, Boor P. Cell‐free DNA: the role in pathophysiology and as a biomarker in kidney diseases. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2018;20:e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Daniel C, Leppkes M, Munoz LE, Schley G, Schett G, Herrmann M. Extracellular DNA traps in inflammation, injury and healing. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(9):559–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Han DSC, Lo YMD. The nexus of cfDNA and nuclease biology. Trends Genet. 2021;37(8):758–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thomas GM, Carbo C, Curtis BR, Martinod K, Mazo IB, Schatzberg D, et al. Extracellular DNA traps are associated with the pathogenesis of TRALI in humans and mice. Blood. 2012;119(26):6335–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zetoune FS, Ward PA. Role of complement and histones in sepsis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:616957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Keane C, Coalter M, Martin‐Loeches I. Immune system disequilibrium‐neutrophils, their extracellular traps, and COVID‐19‐induced sepsis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:711397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Allam R, Kumar SV, Darisipudi MN, Anders HJ. Extracellular histones in tissue injury and inflammation. J Mol Med (Berl). 2014;92(5):465–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shah M, He Z, Rauf A, Kalkhoran SB, Heiestad CM, Stenslokken KO, et al. Extracellular histones are a target in myocardial ischaemia reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;118:1115–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Morimont L, Dechamps M, David C, Bouvy C, Gillot C, Haguet H, et al. NETosis and nucleosome biomarkers in septic shock and critical COVID‐19 patients: an observational study. Biomolecules. 2022;12(8):1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shaw RJ, Abrams ST, Austin J, Taylor JM, Lane S, Dutt T, et al. Circulating histones play a central role in COVID‐19‐associated coagulopathy and mortality. Haematologica. 2021;106(9):2493–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Middleton EA, He XY, Denorme F, Campbell RA, Ng D, Salvatore SP, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to immunothrombosis in COVID‐19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Blood. 2020;136(10):1169–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Godement M, Zhu J, Cerf C, Vieillard‐Baron A, Maillon A, Zuber B, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in SARS‐CoV2 related pneumonia in ICU patients: the NETCOV2 study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:615984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Veras FP, Pontelli MC, Silva CM, Toller‐Kawahisa JE, de Lima M, Nascimento DC, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2‐triggered neutrophil extracellular traps mediate COVID‐19 pathology. J Exp Med. 2020;217(12):e20201129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ng H, Havervall S, Rosell A, Aguilera K, Parv K, von Meijenfeldt FA, et al. Circulating markers of neutrophil extracellular traps are of prognostic value in patients with COVID‐19. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41(2):988–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tait SW, Green DR. Mitochondrial regulation of cell death. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(9):a008706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ganapathy V, Shyamala Devi CS. Effect of histone H1 on the cytosolic calcium levels in human breast cancer MCF 7 cells. Life Sci. 2005;76(22):2631–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brini M, Cali T, Ottolini D, Carafoli E. Intracellular calcium homeostasis and signaling. Met Ions Life Sci. 2013;12:119–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zheng C, Chen J, Chu F, Zhu J, Jin T. Inflammatory role of TLR‐MyD88 signaling in multiple sclerosis. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang X, Li L, Liu J, Lv B, Chen F. Extracellular histones induce tissue factor expression in vascular endothelial cells via TLR and activation of NF‐kappaB and AP‐1. Thromb Res. 2016;137:211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Westman J, Papareddy P, Dahlgren MW, Chakrakodi B, Norrby‐Teglund A, Smeds E, et al. Extracellular histones induce chemokine production in whole blood ex vivo and leukocyte recruitment in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(12):e1005319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Allam R, Darisipudi MN, Tschopp J, Anders HJ. Histones trigger sterile inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43(12):3336–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cugno M, Meroni PL, Gualtierotti R, Griffini S, Grovetti E, Torri A, et al. Complement activation and endothelial perturbation parallel COVID‐19 severity and activity. J Autoimmun. 2021;116:102560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lin P, Chen W, Huang H, Lin Y, Cai M, Lin D, et al. Delayed discharge is associated with higher complement C3 levels and a longer nucleic acid‐negative conversion time in patients with COVID‐19. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sol A, Skvirsky Y, Blotnick E, Bachrach G, Muhlrad A. Actin and DNA protect histones from degradation by bacterial proteases but inhibit their antimicrobial activity. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Noubouossie DF, Whelihan MF, Yu YB, Sparkenbaugh E, Pawlinski R, Monroe DM, et al. In vitro activation of coagulation by human neutrophil DNA and histone proteins but not neutrophil extracellular traps. Blood. 2017;129(8):1021–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. V'Kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(3):155–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mason RJ. Pathogenesis of COVID‐19 from a cell biology perspective. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(4):2000607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kee J, Thudium S, Renner DM, Glastad K, Palozola K, Zhang Z, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 disrupts host epigenetic regulation via histone mimicry. Nature. 2022;610(7931):381–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ruaro B, Salton F, Braga L, Wade B, Confalonieri P, Volpe MC, et al. The history and mystery of alveolar epithelial type II cells: focus on their physiologic and pathologic role in lung. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(5):2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Torres Acosta MA, Singer BD. Pathogenesis of COVID‐19‐induced ARDS: implications for an ageing population. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(3):2002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bonaventura A, Vecchie A, Dagna L, Martinod K, Dixon DL, Van Tassell BW, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and immunothrombosis as key pathogenic mechanisms in COVID‐19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:319–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Karawajczyk M, Douhan Hakansson L, Lipcsey M, Hultstrom M, Pauksens K, Frithiof R, et al. High expression of neutrophil and monocyte CD64 with simultaneous lack of upregulation of adhesion receptors CD11b, CD162, CD15, CD65 on neutrophils in severe COVID‐19. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2021;8:20499361211034065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Radermecker C, Detrembleur N, Guiot J, Cavalier E, Henket M, d'Emal C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps infiltrate the lung airway, interstitial, and vascular compartments in severe COVID‐19. J Exp Med. 2020;217(12):e20201012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Goggs R, Jeffery U, LeVine DN, Li RHL. Neutrophil‐extracellular traps, cell‐free DNA, and immunothrombosis in companion animals: a review. Vet Pathol. 2020;57(1):6–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Banerjee M, Huang Y, Joshi S, Popa GJ, Mendenhall MD, Wang QJ, et al. Platelets endocytose viral particles and are activated via TLR (toll‐like receptor) signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(7):1635–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Stark K, Massberg S. Interplay between inflammation and thrombosis in cardiovascular pathology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(9):666–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Abrams ST, Su D, Sahraoui Y, Lin Z, Cheng Z, Nesbitt K, et al. Assembly of alternative prothrombinase by extracellular histones initiates and disseminates intravascular coagulation. Blood. 2021;137(1):103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kusadasi N, Sikma M, Huisman A, Westerink J, Maas C, Schutgens R. A pathophysiological perspective on the SARS‐CoV‐2 coagulopathy. HemaSphere. 2020;4(4):e457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Skendros P, Mitsios A, Chrysanthopoulou A, Mastellos DC, Metallidis S, Rafailidis P, et al. Complement and tissue factor‐enriched neutrophil extracellular traps are key drivers in COVID‐19 immunothrombosis. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(11):6151–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gould TJ, Lysov Z, Swystun LL, Dwivedi DJ, Zarychanski R, Fox‐Robichaud AE, et al. Extracellular histones increase tissue factor activity and enhance thrombin generation by human blood monocytes. Shock. 2016;46(6):655–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ligi D, Lo Sasso B, Giglio RV, Maniscalco R, DellaFranca C, Agnello L, et al. Circulating histones contribute to monocyte and MDW alterations as common mediators in classical and COVID‐19 sepsis. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kim JE, Yoo HJ, Gu JY, Kim HK. Histones induce the procoagulant phenotype of endothelial cells through tissue factor up‐regulation and thrombomodulin down‐regulation. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Cron RQ. COVID‐19 cytokine storm: targeting the appropriate cytokine. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3(4):e236–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hojyo S, Uchida M, Tanaka K, Hasebe R, Tanaka Y, Murakami M, et al. How COVID‐19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflammation Regener. 2020;40:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Fajgenbaum DC, June CH. Cytokine storm. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(23):2255–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kox M, Waalders NJB, Kooistra EJ, Gerretsen J, Pickkers P. Cytokine levels in critically ill patients with COVID‐19 and other conditions. JAMA. 2020;324:1565–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Leisman DE, Ronner L, Pinotti R, Taylor MD, Sinha P, Calfee CS, et al. Cytokine elevation in severe and critical COVID‐19: a rapid systematic review, meta‐analysis, and comparison with other inflammatory syndromes. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(12):1233–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Melo AKG, Milby KM, Caparroz A, Pinto A, Santos RRP, Rocha AP, et al. Biomarkers of cytokine storm as red flags for severe and fatal COVID‐19 cases: a living systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0253894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Xu W, Sun NN, Gao HN, Chen ZY, Yang Y, Ju B, et al. Risk factors analysis of COVID‐19 patients with ARDS and prediction based on machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Jiang P, Jin Y, Sun M, Jiang X, Yang J, Lv X, et al. Extracellular histones aggravate inflammation in ARDS by promoting alveolar macrophage pyroptosis. Mol Immunol. 2021;135:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Xu Z, Huang Y, Mao P, Zhang J, Li Y. Sepsis and ARDS: the dark side of histones. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:205054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Block H, Zarbock A. A fragile balance: does neutrophil extracellular trap formation drive pulmonary disease progression? Cells. 2021;10(8):1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Elliott W, Jr. , Guda MR, Asuthkar S, Teluguakula N, Prasad DVR, Tsung AJ, et al. PAD inhibitors as a potential treatment for SARS‐CoV‐2 immunothrombosis. Biomedicines. 2021;9(12):1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Zuo Y, Zuo M, Yalavarthi S, Gockman K, Madison JA, Shi H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps and thrombosis in COVID‐19. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;51(2):446–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Cavalier E, Guiot J, Lechner K, Dutsch A, Eccleston M, Herzog M, et al. Circulating nucleosomes as potential markers to monitor COVID‐19 disease progression. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:600881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Bouchard BA, Colovos C, Lawson MA, Osborn ZT, Sackheim AM, Mould KJ, et al. Increased histone‐DNA complexes and endothelial‐dependent thrombin generation in severe COVID‐19. Vascul Pharmacol. 2022;142:106950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Obermayer A, Jakob LM, Haslbauer JD, Matter MS, Tzankov A, Stoiber W. Neutrophil extracellular traps in fatal COVID‐19‐associated lung injury. Dis Markers. 2021;2021:5566826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Becker K, Beythien G, de Buhr N, Stanelle‐Bertram S, Tuku B, Kouassi NM, et al. Vasculitis and neutrophil extracellular traps in lungs of golden Syrian hamsters with SARS‐CoV‐2. Front Immunol. 2021;12:640842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Jin J, Fang F, Gao W, Chen H, Wen J, Wen X, et al. The structure and function of the glycocalyx and its connection with blood‐brain barrier. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:739699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sproston NR, Ashworth JJ. Role of C‐reactive protein at sites of inflammation and infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Abrams ST, Zhang N, Dart C, Wang SS, Thachil J, Guan Y, et al. Human CRP defends against the toxicity of circulating histones. J Immunol. 2013;191(5):2495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Hsieh IN, White M, Hoeksema M, Deluna X, Hartshorn K. Histone H4 potentiates neutrophil inflammatory responses to influenza A virus: down‐modulation by H4 binding to C‐reactive protein and Surfactant protein D. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0247605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Wadowski PP, Jilma B, Kopp CW, Ertl S, Gremmel T, Koppensteiner R. Glycocalyx as possible limiting factor in COVID‐19. Front Immunol. 2021;12:607306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Cai X, Panicker SR, Biswas I, Giri H, Rezaie AR. Protective role of activated protein C against viral mimetic poly(I:C)‐induced inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2021;121:1448–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Bayrakci N, Ozkan G, Mutlu LC, Erdem L, Yildirim I, Gulen D, et al. Relationship between serum soluble endothelial protein C receptor level and COVID‐19 findings. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2021;32(8):550–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Alaniz C. An update on activated protein C (xigris) in the management of sepsis. P T. 2010;35(9):504–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Zhou P, Wu E, Alam HB, Li Y. Histone cleavage as a mechanism for epigenetic regulation: current insights and perspectives. Curr Mol Med. 2014;14(9):1164–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Beurskens DMH, Huckriede JP, Schrijver R, Hemker HC, Reutelingsperger CP, Nicolaes GAF. The anticoagulant and nonanticoagulant properties of heparin. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(10):1371–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Mousavi S, Moradi M, Khorshidahmad T, Motamedi M. Anti‐inflammatory effects of heparin and its derivatives: a systematic review. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2015;2015:507151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Li X, Li L, Shi Y, Yu S, Ma X. Different signaling pathways involved in the anti‐inflammatory effects of unfractionated heparin on lipopolysaccharide‐stimulated human endothelial cells. J Inflamm (Lond). 2020;17:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Tandon R, Sharp JS, Zhang F, Pomin VH, Ashpole NM, Mitra D, et al. Effective inhibition of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry by heparin and enoxaparin derivatives. J Virol. 2021;95(3):e01987–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Hogwood J, Pitchford S, Mulloy B, Page C, Gray E. Heparin and non‐anticoagulant heparin attenuate histone‐induced inflammatory responses in whole blood. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Lasky JA, Fuloria J, Morrison ME, Lanier R, Naderer O, Brundage T, et al. Design and rationale of a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 2/3 study evaluating dociparstat in acute lung injury associated with severe COVID‐19. Adv Ther. 2021;38(1):782–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Meara CHO, Coupland LA, Kordbacheh F, Quah BJC, Chang CW, Simon Davis DA, et al. Neutralizing the pathological effects of extracellular histones with small polyanions. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Wichapong K, Silvestre‐Roig C, Braster Q, Schumski A, Soehnlein O, Nicolaes GAF. Structure‐based peptide design targeting intrinsically disordered proteins: novel histone H4 and H2A peptidic inhibitors. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:934–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Boersma HH, Kietselaer BL, Stolk LM, Bennaghmouch A, Hofstra L, Narula J, et al. Past, present, and future of annexin A5: from protein discovery to clinical applications. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(12):2035–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Morel O, Marchandot B, Jesel L, Sattler L, Trimaille A, Curtiaud A, et al. Microparticles in COVID‐19 as a link between lung injury extension and thrombosis. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(2):00954–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]