Abstract

Mobile zinc is an abundant transition metal ion in the central nervous system, with pools of divalent zinc accumulating in regions of the brain engaged in sensory perception and memory formation. Here, we present essential tools that we developed to interrogate the role(s) of mobile zinc in these processes. Most important are (a) fluorescent sensors that report the presence of mobile zinc and (b) fast, Zn‐selective chelating agents for measuring zinc flux in animal tissue and live animals. The results of our studies, conducted in collaboration with neuroscientist experts, are presented for sensory organs involved in hearing, smell, vision, and learning and memory. A general principle emerging from these studies is that the function of mobile zinc in all cases appears to be downregulation of the amplitude of the response following overstimulation of the respective sensory organs. Possible consequences affecting human behavior are presented for future investigations in collaboration with interested behavioral scientists.

Keywords: bioinorganic chemistry, metalloneurochemistry, mobile zinc, neurochemistry, sensory perception

Fast chelating probes and novel fluorescent sensors reveal a common function for mobile zinc in sensory perception.

Abbreviations

AMD, age‐related macular degeneration

AMPA, α‐amino‐3‐hydroxy‐5‐methyl‐4‐isoxazolepropionic acid

DA‐ZP1, diacetyl‐ZP1

DCN, dorsal cochlear nucleus

EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

EPSC, excitatory postsynaptic currents

GABA, γ‐aminobutyric acid

GCL, granule cell

GL, glomerular

K d , dissociation constant

LGNd, dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus

NMDA, N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate

PET, photo‐induced electron transfer

TPA, tris(2‐pyridylmethyl)amine

TPEN, N,N,N′,N′‐tetrakis(2‐pyridinylmethyl)‐1,2‐ethanediamine

WT, wild‐type

ZP1, Zinpyr‐1

Neurotransmission, a form of electrophysiological information transfer, occurs at synapses in the central nervous system, a small space across which chemical signals pass from pre‐ to postsynaptic neurons. Such communication involving glutamate‐rich neurons in the brain facilitates cognition, memory formation, and perception [1, 2]. In these so‐called glutamatergic neurons, electrical signals travel along presynaptic neurons, causing glutamate‐filled vesicles to fuse with the membrane and release their cargo into the synapse (Fig. 1) [3]. In certain regions of the brain, these vesicles also contain mobile zinc, supplied by the zinc transporter ZnT3 [4]. Here, upon release into synapses, the glutamate and zinc ions compete for binding sites on postsynaptic neuronal receptors, such as N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate (NMDA) or α‐amino‐3‐hydroxy‐5‐methyl‐4‐isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), both transmembrane receptors that mediate fast synaptic transmission [1, 5, 6]. When glutamate binds to these receptors, they undergo a conformational change and open ion channels, one of which allows calcium ions to pass through to the postsynaptic neuron. There the calcium ions bind to a variety of protein targets, including calmodulin, which relay signals to various enzymes and other proteins. Although many of the details of these information transfer signaling mechanisms have been elucidated, a crucial question remains: What is the function of the zinc? Answering this question remained a holy grail in the field of metalloneurochemistry until the research described here was carried out [7, 8, 9].

Fig. 1.

Metalloneurotransmission at a synapse. Zinc ions (gray spheres) are loaded into presynaptic vesicles containing glutamate (red spheres) by the transporter ZnT3. In response to an action potential, the vesicles fuse to the presynaptic membrane, releasing cargo into the synapse. Zinc and glutamate ions compete for binding sites on postsynaptic receptors, such as the NMDA receptor. Upon glutamate binding, the NMDA receptor opens to form an ion channel that allows calcium ions (white spheres) to enter the postsynaptic neuron, where they bind to several targets, including calmodulin, initiating a signaling cascade.

Fluorescent sensors for mobile zinc in the brain

Historically, zinc(II) ions in the brain were detected histochemically by the Timm‐Danscher staining method whereby divalent zinc reacts to form insoluble sulfide complexes in tissue that is then frozen or embedded, sectioned, and developed with metallic silver [10, 11, 12, 13]. Although this approach provides precise visualization of brain zinc with anatomic resolution, it is not compatible with either in vitro or in vivo experiments that require live animals or tissue slices. Moreover, the method cannot be used to study dynamic processes that occur on short timescales [14]. Spectroscopic techniques to image divalent zinc in vivo and do not require ex vivo sampling include phosphorescence [15], bioluminescence [16], and magnetic resonance [17, 18], but the most popular method is fluorescence [19]. Although zinc(II) ions are spectroscopically silent, stores and fluxes of mobile zinc can be visualized in real time with fluorescence microscopy if appropriate probes are available. The development and application of optical sensors for this purpose have been comprehensively reviewed [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. We therefore limit our discussion to a few powerful small‐molecule probes, the first of which is Zinpyr‐1 (ZP1) [28, 29].

As shown in Fig. 2, ZP1 comprises a dichlorofluorescein fluorophore substituted with dipicolylamine ligands to form two binding pockets for coordinating divalent zinc. In the absence of zinc ions, a photo‐induced electron transfer (PET) mechanism renders the molecule nonfluorescent [30]. In the presence of zinc(II), PET quenching no longer occurs and the resulting fluorescence can be detected by optical spectroscopy. The spectral properties and solution behavior of ZP1 have been well characterized [31]. The molecule binds two zinc(II) ions with differing affinities. The dissociation constant (K d value) for binding the first ion is 0.04 pm, and for the second, it is 1.2 nm, resulting in an apparent K d of 0.7 nm for the overall complex, as measured by fluorescence spectroscopic titrations [31]. Replacement of the dipicolylamine groups with other ligand appendages facilitates tuning of the zinc(II) binding constants over several orders of magnitude, as required for different neuroscience applications [32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39]. Given the wide variety of available probes, it is possible to select one having the appropriate metal binding affinity for most studies of interest [40].

Fig. 2.

Reaction of selected sensors with zinc to give fluorescent products.

Zinpyr‐1 is cell‐membrane‐permeable and accumulates in the Golgi apparatus [41]. Derivatization of the fluorescein benzoic acid ring at either the 5‐ or 6‐position with an additional negatively charged carboxylate group prevents the sensor from crossing cell membranes, however, providing extracellular versions of ZP1, such as ZP1‐5CO2H or ZP1‐6CO2H (Fig. 2) [42]. Trappable analogs, including ZP1‐5CO2Et and ZP1‐6CO2Et, have also been synthesized by masking the carboxylate as an ester cleavable by intracellular esterases (Fig. 2) [42]. Subcellular localization can be controlled by attaching different substituents that direct the sensor to programmed locales. For example, one approach has been to use routine amide bond coupling reactions to attach a targeting peptide to the carboxylate group of ZP1‐5CO2H or ZP1‐6CO2H to provide constructs that localize to the plasma membrane, mitochondria, cytoplasm, nucleus, or other organelle of interest [43, 44]. Mitochondrial targeting has also been achieved by the attachment of a triphenylphosphonium group [45]. In a complementary way, ZP1 derivatives can be synthesized bearing reactive units that serve as substrates for readily localizable enzyme systems. Examples include a benzylguanine moiety for alkylation of human O 6‐alkylguanine transferase (SNAP‐tag) and a chloroalkane linker for reaction with a haloalkane dehalogenase (HaloTag®) [46, 47]. These methods can also be used in combination with other zinc sensors for multiwavelength imaging [48].

Zinpyr‐1 exhibits modest proton‐induced background fluorescence [31]. To avoid this problem, the phenolic oxygen atoms of the ZP1 xanthene core were acetylated as shown in Fig. 3 to produce diacetyl‐ZP1 (DA‐ZP1) [45, 49]. Addition of the acetyl groups forces the fluorescein scaffold to adopt the completely nonfluorescent lactone form, such that DA‐ZP1 exhibits no background fluorescence, even under acidic conditions. Upon zinc ion binding, the acetyl groups are rapidly hydrolyzed, and fluorescence is restored as the parent ZP1 sensor is generated. By masking the phenolic oxygen atoms with photocleavable protecting, instead of acetyl, groups, the same reduction in background fluorescence can be obtained [50]. Additionally, because the protecting groups can be removed with brief pulses of ultraviolet light and the protected sensor does not bind zinc(II), both spatial and temporal control can be achieved [50]. Other reaction‐based sensors exhibit reduced background fluorescence, which may be important in some applications. The SpiroZin family of sensors, for example, have been used to image mobile zinc in acidic subcellular compartments, such as synaptic vesicles [51, 52]. These far‐red emitting probes are also compatible with two‐photon fluorescence microscopy, facilitating the imaging of zinc in functionally active brain tissue slices [52].

Fig. 3.

Reaction of the acetylated sensor DA‐ZP1 with zinc.

Intensity‐based sensors, like ZP1 and SpiroZin2, which fluoresce in the presence of zinc ions, are suitable for identifying the presence of mobile zinc in a variety of biological systems. With careful calibration, these tools can be used to extract information about local zinc concentrations [53, 54, 55, 56]. Although obtaining accurate absolute measurements of mobile zinc concentrations in synaptic spaces and live neurons can be difficult, such data are critical for understanding the role of the ion in health and disease [57]. The deployment of ratiometric probes is one strategy to address this challenge, and a number of suitable sensors have been described in the literature [58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65]. Of particular interest for quantifying synaptically released zinc is LZ9 (Fig. 4), an extracellular, peptide‐based ratiometric sensor [66, 67]. As shown in the figure, LZ9 provides ZP1 tethered to Lissamine Rhodamine™ B, a zinc‐insensitive fluorophore, through a polyproline helix. The peptide linker acts as a spacer to separate the two chromophores, thus preventing undesired photophysical interactions. Extracellular zinc concentrations are obtained by comparing the fluorescence intensity of the construct at different excitation wavelengths [66].

Fig. 4.

Structure of the ratiometric sensor LZ9, which features a zinc‐responsive ZP1 unit attached to Lissamine Rhodamine B, a zinc‐insensitive fluorophore, by a polyproline peptide.

Chemical tools to intercept mobile zinc

Small‐molecule chelators (Fig. 5) that can intercept and sequester a metal ion en route to a cellular or synaptic target are important tools in the metalloneurochemist's arsenal for interrogating both physiological and pathological functions [68]. When studying mobile zinc in neurotransmission, it is advantageous to deploy chelators either intra‐ or extracellularly, as determined by the experimental objective. In both cases, however, it is essential that the chelator binds zinc rapidly and selectively enough to block it from reaching the functional target. Application of insufficiently rapid or selective chelators can lead to false conclusions about the functions of zinc in the brain. For example, investigators studying hippocampal long‐term potentiation in mossy fiber synapses with various membrane‐permeable chelators reached conflicting conclusions about the role of mobile zinc in this process, differences that were traced to the choice of chelator [69, 70, 71]. Similarly, application of suboptimal extracellular chelators in separate studies of the same system also led experimentalists to report seemingly irreconcilable conclusions about how mobile zinc mediates synaptic strength in the hippocampus [71, 72, 73, 74]. Furthermore, evidence continues to mount that copper ions also play important roles in regulating neurotransmission [75, 76, 77]. Copper studies would benefit from the design and synthesis of chelators selective binding of zinc over copper. Peptoid ligands that exhibit such selectivity offer one intriguing approach [78].

Fig. 5.

Chemical structures of selected zinc chelators.

To prevent synaptically released zinc from binding to post‐ or extrasynaptic targets, neuroscientists typically use extracellular chelators that can be perfused into tissue slices or applied directly to the brain of a live animal. Comparison of electrophysiology recordings or other measurements in the presence and absence of the chelator allows inferences about the role of mobile zinc to be made. One of the most frequently applied divalent metal ion chelators for this purpose is ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). EDTA binds zinc(II) ions with a K d of 26 fm [79]. It also binds calcium(II) ions, although less strongly, with a K d of 19 nm [79]. To ensure that observations are solely a result of zinc chelation and not an artifact of complex formation between EDTA and calcium, a preformed calcium‐EDTA complex is often employed experimentally. Dissociation of the calcium(II) ion from EDTA and subsequent ligation with zinc(II) is a kinetically slow process, albeit thermodynamically favored [79]. As a result, fast neurotransmission events in the synapse cannot be accurately defined with the use of calcium‐EDTA or other such relatively slow extracellular chelators.

Fortunately, these problems have largely been solved by the development of novel, rapid extracellular chelators specifically designed for mobile zinc, including ZX1 [71, 80]. The case of ZX1 is instructive [71]. The molecule features a dipicolylamine zinc‐binding motif and, to prevent cell entry at physiological pH, a negatively charged sulfonate group. ZX1 binds divalent zinc tightly, with a K d of 1.0 nM, and selectively, with little affinity for calcium or other biologically relevant metal ions. Competitive kinetic experiments with the zinc‐bound form of the fluorescent sensor ZP3 with either ZX1 or calcium‐EDTA were carried out. Complete fluorescence quenching was observed in both cases, but the reaction with ZX1 was substantially faster than that with EDTA [71]. Stopped‐flow fluorescence experiments indicated that ZX1 chelates zinc approximately 200 times more rapidly than calcium‐EDTA [66]. Because of this rapid binding rate, relatively low concentrations (~100 μm) of the chelator are sufficient for many neuroscience experiments. By contrast, experiments with tricine, a weak extracellular zinc chelator having a K d of 2.8 μm, revealed that, even at concentrations of 10 mm, it is unable to chelate synaptically released zinc rapidly enough to inhibit its neurochemical functions [66].

For intracellular experiments, the membrane‐permeable and readily available chelator N,N,N′,N′‐tetrakis(2‐pyridinylmethyl)‐1,2‐ethanediamine (TPEN) has been used to chelate mobile zinc in cells, tissues, and live animals [81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88]. Given the high affinity of TPEN for zinc(II) ions, with an apparent K d of 0.7 fm, TPEN can chelate zinc ions that are otherwise tightly bound to cellular proteins, leading to programmed cell death by apoptotic pathways [79, 89, 90, 91, 92]. TPEN can bind many other transition metal ions tightly, so care must be taken when interpreting results when it is employed. Tris(2‐pyridylmethyl)amine (TPA) is a good alternative chelator for mobile zinc that is less toxic and membrane‐permeable [93]. In cells and live tissue slices, TPA removes zinc from fluorescence sensors more than twice as fast as TPEN [93]. The lower cellular toxicity associated with TPA makes it attractive for studies in a wide variety of biological contexts [48, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98]. Although there is some evidence that TPA chelates metal ions other than zinc(II), particularly copper(I), it does not appear to substantially affect the concentrations of these ions at the less toxic and membrane‐permeable levels where it has typically been applied [99, 100].

Mobile zinc in audition

We now turn our attention to the role of mobile zinc in sensory perception. First, we discuss the role of zinc in audition, or hearing. In response to sound, nerve impulses from the ear are transmitted to the cochlear nucleus for processing. In the dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN), auditory signals are integrated with inputs from other areas of the brain, including additional somatosensory information that is used to help orient sounds in the vertical plane [101, 102, 103]. Autometallographic Timm‐Danscher staining of tissue from rodents revealed that, although the outer or so‐called molecular layer of the DCN is rich in zinc, the deeper layers do not accumulate the ion to a significant extent [104]. Treatment of live DCN brain slices from wild‐type (WT) mice with the small‐molecule sensor DA‐ZP1 corroborated these results and indicated that the molecular layer contains pools of mobile zinc, which can be released upon electrophysiological stimulation (Fig. 6) [67]. The release of zinc into synaptic and extrasynaptic spaces was further visualized and quantitated with the extracellular ratiometric sensor LZ9 [66]. Immediately upon electrical stimulation, the LZ9 ratiometric signal increased in a localized way around the electrode. To confirm that the signals originated from the presynaptic release of zinc, the slices were treated with various concentrations of ZX1 to chelate synaptic zinc. Addition of 20 μm ZX1 abrogated the change in signal. These results demonstrated that mobile zinc is released into the synapse upon electrical stimulation. In comparison, tissue from mice in which the ZnT3 transporter had been knocked out showed no accumulation of mobile zinc in either the molecular or deep layers [67].

Fig. 6.

Mobile zinc in live DCN tissue slices. (Left) Brightfield and fluorescence microscopy images of DCN tissue treated with DA‐ZP1 reveal mobile zinc in the molecular but not the deep layer of WT mice. (Right) Stimulation of the molecular layer releases synaptic zinc as revealed by extracellular ZP1‐6CO2H fluorescence. Stimulation of the deep layer has no effect. ZnT3 knockout mice did not exhibit this phenomenon. Figure adapted from reference [67].

A few electrophysiology experiments have been conducted to identify molecular targets of synaptically released mobile zinc in the DCN. Excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) carried by NMDA receptors are diminished by mobile zinc during neurotransmission such that the application of the fast extracellular chelator ZX1 to DCN tissue from WT mice caused a substantial increase in EPSC measurements [66]. Not surprisingly, in similar experiments with ZnT3 knockout mice, ZX1 did not show this effect [66]. In separate work, patch clamp electrophysiology experiments of pharmacologically isolated AMPA receptors in the DCN revealed an analogous ZnT‐3 dependent response: addition of the chelator ZX1 caused a significant increase in EPCSs carried by AMPA receptors in WT mice but not in ZnT‐3 knockout mice [67]. Furthermore, tonic or ambient zinc concentration levels in the DCN are sufficient to reduce the spontaneous firing of principal neurons by promoting a form of inhibitory glycinergic neurotransmission [105]. These data point to a role for mobile zinc in the DCN in which it acts to attenuate neurotransmission.

Physiologically, the effects of these processes can be observed in animal studies involving exposure to sustained, loud sounds [67]. DCN tissue harvested from noise‐ and sham‐exposed mice was used for electrophysiological recordings before and after the addition of the chelator ZX1. In tissue from the sham‐exposed mice, the addition of ZX1 caused an increase in the excitatory EPSC measurements—removal of the mobile zinc caused an increase in synaptic transmission. In tissue from the noise‐exposed group, the addition of ZX1 did not affect the EPSC. These data suggest a depletion of mobile zinc in response to sustained loud noises. To investigate this possibility, the ratiometric mobile zinc sensor LZ9 was applied to quantify the amount of synaptic zinc released from tissues from the two groups of mice. Tissue from the noise‐exposed animals released less zinc than tissue from sham‐exposed animals in response to electrical stimulation, suggesting that noise‐exposed animals have reduced vesicular zinc levels. These findings raise important questions: Is synaptic zinc released to suppress the effects of loud noises? If so, why? Is the effect applicable to other modes of sensory perception?

Mobile zinc in olfaction

Odor receptors are expressed in the nasal epithelium and comprise a family of G protein‐coupled receptors (GPCRs) that account for approximately 2% of the human genome and more than 4% of the human proteome [106, 107]. During olfaction, odorants transiently bind noncovalently to a subset of these receptors in the nose, inducing protein conformational changes with patterns that are characteristic for each unique smell [108, 109]. Signals resulting from these ligand binding events are communicated to the olfactory bulb in the brain for processing. The bulb has several layers of nerve cells that coordinate and integrate these signals coming directly from the nose, the architecture of which has been carefully described elsewhere [110, 111]. In these layers, glomerular (GL) and granule cells (GCLs) express high levels of the zinc transporter ZnT3 [112]. Timm‐Danscher staining of fixed tissues from mouse olfactory bulbs showed a correlation between the location of ZnT3 and zinc ion stores [112]. Subsequent experiments in rats indicated that many of these zinc‐enriched neuronal terminals originate in the primary olfactory cortex [113].

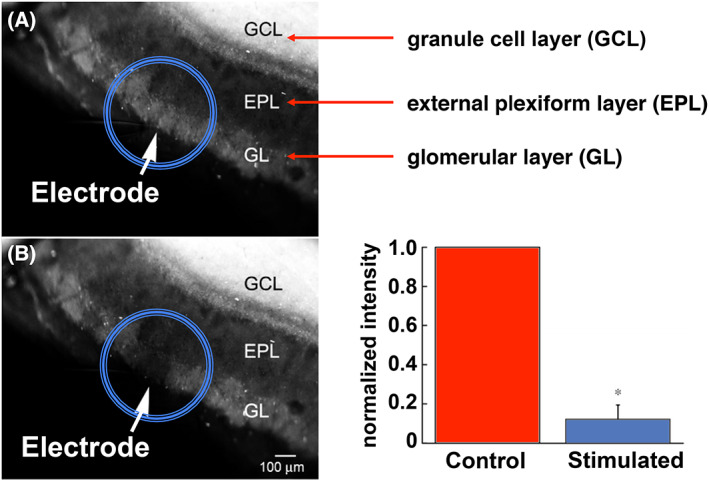

Staining of olfactory bulb tissue slices from mice with the fluorescent sensor ZP1 revealed the presence of large stores of mobile zinc in the GL and GCL layers, with significantly less accumulation elsewhere [114]. The reservoirs of zinc in the GL layer are released from synapses upon stimulation with electrical pulses, a result strikingly similar to that observed in the DCN during auditory processing (Fig. 7) [114]. In a functional study, application of exogenous zinc to dissociated mouse brain olfactory bulb neurons in culture modulated AMPA receptor responses, as measured by patch clamp electrophysiology [114, 115]. In these experiments, the frequency and magnitude of ESPCs affected by zinc addition were cell type‐specific, and in some cases, there were no responses at all [114, 115]. These data suggest that the synaptic release of zinc may play a role in odor discrimination, perhaps by selectively modulating neurotransmission between discrete pairs of neurons.

Fig. 7.

Mobile zinc in live olfactory bulb slices. The sensor ZP1 detects mobile zinc in the GL and GCL layers, but not in the external plexiform layer. In comparison with control tissue (panel A), upon stimulation with an electrode, mobile zinc is released from glomeruli (panel B), as visualized by ZP1 fluorescence, which is quantified in the bar graph. Figure adapted from reference [114].

In preliminary electrophysiology experiments to investigate the function of synaptically released zinc in the olfactory bulb, we measured the EPSCs at NMDA receptors in neurons that interface with one of the zinc‐rich layers. Just as we observed in the DCN, chelation of zinc with ZX1 causes an increase in synaptic transmission measured as ESPC. This exciting discovery revealed that two completely different organs, the ear and the nose, involved in sensory perception exhibit the same type of response when presented with synaptically released mobile zinc.

Because the olfactory bulb involved in odor processing is experimentally more readily accessible than the DCN involved in hearing, we were able to perform preliminary experiments in live animals to determine whether the olfactory phenomena we observed in live tissue slices occur in vivo. In this study, electrodes were inserted into the olfactory bulb of an anesthetized mouse to record synaptic activity before, during, and after the introduction of an odorant at the nose. Synaptic activity, revealed by patch clamp electrophysiology, increased when the animal smelled the odorant. To examine the role of zinc, we added the extracellular chelator ZX1 directly to the bulb and repeated the measurements. Here, baseline synaptic activity was greater in the presence of ZX1, even in the absence of odorant. Addition of the odorant induced a large increase in activity, much greater than that observed in the absence of ZX1. These results firmly establish a role for zinc during olfaction, namely to serve as a brake that attenuates the intensity of neurotransmission of odor perception by the brain. Chelation of mobile zinc increases synaptic transmission! A correlative hypothesis is that the addition of exogenous zinc should decrease such neurotransmission.

To test this hypothesis, we used mice that were genetically engineered to express proteins that fluoresce upon neurotransmission in the olfactory bulb. We collected detailed maps of synaptic activity in response to different odorants. Upon direct application of zinc sulfate to the olfactory bulb, we detected a significant reduction in activity. This effect was reversible upon washout of the excess zinc. Whereas chelation of zinc causes an increase in neurotransmission, application of extra zinc produced a reversible reduction in neurotransmission. Repetition of the experiments in the presence of the chelator ZX1 revealed large, but reversible, increases in synaptic transmission throughout the olfactory bulb. In the presence of ZX1, we no longer observed discrete regions of neuronal activity, but rather, global synaptic firing. These results reveal important roles played by mobile zinc in the perception of smell.

Mobile zinc in vision

As in other sensory circuits, mobile zinc in the visual system accumulates in only certain neurons and tissue types. Early X‐ray fluorescence studies of fresh, postmortem human eyes revealed the highest concentrations of zinc in retinal and choroid tissue, with substantially smaller amounts in the sclera, cornea, and lens [116]. Subsequent X‐ray fluorescence experiments revealed that only certain layers of the rat retina contain large amounts of zinc [117]. These findings were corroborated by immunohistochemistry experiments revealing the vesicular zinc transporter ZnT3. Mouse and rat retinal tissue treated with antibodies for ZnT3 showed characteristic staining patterns that suggested only certain tissue layers store significant quantities of vesicular zinc [118, 119]. Curiously, although Timm‐Danscher staining patterns of retinas obtained from light‐ and dark‐adapted rats were generally consistent in both sample groups, there was a significant difference in the amount of zinc detected in the outer and inner nuclear layers, suggesting that zinc migrates during phototransduction in the eye [120, 121]. Concentrated stores of zinc were found in the outer nuclear layer of tissue from dark‐adapted rats, but in the inner nuclear layer in tissue from light‐adapted animals [120, 121]. The physiological consequences of this observation are unclear.

Although mobile zinc has been implicated in a number of excitatory and inhibitory processes in the visual system, the functional roles of the ion in the retina are not well understood [122]. Depolarization of live rat retinal tissue with potassium chloride releases zinc ions, as detected by fluorescence microscopy with the zinc sensor Newport Green [121]. A growing body of evidence suggests that mobile zinc in the retina attenuates NMDA receptor‐mediated neurotransmission [117, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126]. This finding is consistent with the role of zinc in other sensory systems and is supported by electrophysiology recordings of ganglion cells from tiger salamander retina showing that zinc completely, and reversibly, inhibits NMDA receptor responses [123]. Other excitatory neurotransmission involving AMPA receptors in horizontal cells from frog retina can be potentiated or inhibited, depending on the zinc ion concentration [127]. Mobile zinc can also modulate inhibitory neurotransmission. For example, in retinas from different species of fish, zinc modulates GABAergic neurotransmission carried by γ‐aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, although the direction of modulation depends on receptor subtype [128, 129, 130]. Glycinergic neurotransmission carried by glycine receptors in retinal ganglion and amacrine cells is also affected by endogenous zinc [131, 132, 133]. Through these various mechanisms, mobile zinc might contribute to the processing of color discrimination [134, 135].

Land and Shamalla‐Hannah have proposed an intriguing role for mobile zinc in the segregation of visual pathways [136]. Timm‐Danscher imaging of the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (LGNd) of developing rats during the first 3 weeks of life revealed intense staining for zinc with a distribution that correlates with uncrossed neuronal axons projecting from the retina. After 24 days, however, zinc was no longer detectable in the LGNd by histochemical methods, although it was easily identified in adjacent tissue from the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus through adulthood. These results suggest that zinc may play role in early development through which ipsilateral and contralateral differentiation occurs for neurons originating in the eye. Additional study of this phenomenon is warranted.

During ocular injury, such as that following optic nerve crush, release of mobile zinc ions into neighboring tissue can cause cell death and prevent nerve regeneration [137]. Chelation of the zinc with the extracellular chelator ZX1 stops this process and allows the optic nerve to regenerate after injury. These encouraging findings suggest that rapid zinc chelation after traumatic injury may be clinically beneficial. Release of zinc and subsequent cell death occurs during other ophthalmological injuries, such as retinal ischemia [138] or target deprivation [139]. In the case of retinal ischemia, pretreatment with the chelator, TPEN or calcium‐EDTA, significantly inhibited retinal degeneration during ischemia in rats compared with control groups [138]. Prompt zinc chelation might have a general therapeutic effect for many eye‐related injuries in which zinc stores are liberated. On the contrary, treatment of postmortem human eyes with varying concentrations of the chelator TPEN led to apoptosis in retinal pigment epithelial cells in a dose‐dependent manner, an effect that could be reversed by the addition of zinc or copper [82].

The association of zinc with age‐related macular degeneration (AMD) has attracted attention, not only because of the wide prevalence and global burden of the disease [140] but also because there is no reliable treatment for preventing the loss of vision that arises from the irreversible degradation of photoreceptors in the eye [141]. A small but well‐controlled study published in 1988 found that adults who took twice‐daily zinc sulfate tablets experienced significantly less vision loss than those who were administered a placebo [142]. Given the uncertainty surrounding the small population sample size and relatively short duration of this study, a larger prospective investigation of the benefits and risks of zinc dietary supplementation was undertaken [143]. The results suggested a therapeutic benefit to taking either zinc, as zinc oxide, or a combination of zinc and antioxidants for patients at high risk of developing AMD [144]. Curiously, in a separate study, patients who took zinc supplements had higher blood plasma zinc concentrations than those who did not, but there was no significant difference between plasma zinc levels in patients suffering from neovascular AMD and those in control groups [145]. Perhaps this observation is a consequence of the fact that blood plasma zinc concentrations are not always reliable indicators of local zinc concentrations in specific organs, tissues, cells, or subcellular compartments, thus highlighting the need for robust tools for ascertaining these values. For example, one of the hallmarks of AMD is the development of subretinal pigment epithelial deposits such as drusen; these deposits are associated with the accumulation of zinc in this area of the eye, as revealed by X‐ray fluorescence and optical spectroscopy with small‐molecule zinc sensors [146]. Subsequent studies with primary human retinal pigment epithelium cells in culture identified several genes that are beneficially associated with zinc supplementation [147]. These data suggest that zinc plays a critical role in maintaining eye health, even when the precise molecular mechanisms are incompletely elucidated.

Concluding remarks

Fluorescent sensors and fast zinc chelators have enabled us to discover a conserved role of mobile zinc in regulating and fine‐tuning signal intensity in sensory perception, specifically for audition, olfaction, and vision. The fast, zinc‐specific chelator ZX1 and zinc‐selective fluorescent probes provided tools that enabled these key discoveries, including the finding that mobile zinc binding to postsynaptic and extrasynaptic glutamatergic receptors downregulates excitatory postsynaptic current. This information may auger a general principle for zinc mobile ions in metalloneurochemistry, consequences of which could be the protection of neuronal circuits from sensory overload that interferes with the intended function and/or the suppression of background to enhance the primary signal. Furthermore, mobile zinc may potentially minimize any damage, such as seizures, that such an overload might produce. As new experimental methods, such as RNA‐seq and DRUG‐seq, enable the collection of data pertaining to the biochemical and genetic responses to these processes, new roles for mobile zinc in sensory perception may be discovered [148, 149]. The tools are in place!

Author contributions

JMG and SJL composed and edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health grant R01‐GM065519 to S.J.L. None of the conclusions presented could have been possible without the close and enthusiastic participation of our principal collaborators, Larry Benowitz, Ian Davison, Paul Rosenberg, and Thanos Tzounopoulos, as well as members of their research groups, whose names are listed in our citations.

Edited by Martin Högbom

References

- 1. Barr CA, Burdette SC. The zinc paradigm for metalloneurochemistry. Essays Biochem. 2017;61:225–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Besser L, Chorin E, Sekler I, Silverman WF, Atkin S, Russell JT, et al. Synaptically released zinc triggers metabotropic signaling via a zinc‐sensing receptor in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2890–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paoletti P, Vergnano AM, Barbour B, Casado M. Zinc at glutamatergic synapses. Neuroscience. 2009;158:126–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shen H, Wang F, Zhang Y, Xu J, Long J, Qin H, et al. Zinc distribution and expression pattern of ZnT3 in mouse brain. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2007;119:166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rachline J, Perin‐Dureau F, Le Goff A, Neyton J, Paoletti P. The micromolar zinc‐binding domain on the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B. J Neurosci. 2005;25:308–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Westbrook GL, Mayer ML. Micromolar concentrations of Zn2+ antagonize NMDA and GABA responses of hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1987;328:640–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burdette SC, Lippard SJ. Meeting of the minds: metalloneurochemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3605–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goldberg JM, Lippard SJ. Challenges and opportunities in brain bioinorganic chemistry. Acc Chem Res. 2017;50:577–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang CJ. Bioinorganic life and neural activity: toward a chemistry of consciousness? Acc Chem Res. 2017;50:535–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Danscher G, Stoltenberg M. Zinc‐specific autometallographic In vivo selenium methods: tracing of zinc‐enriched (ZEN) terminals, ZEN pathways, and pools of zinc ions in a multitude of other ZEN cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:141–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Danscher G, Juhl S, Stoltenberg M, Krunderup B, Schrøder HD, Andreasen A. Autometallographic silver enhancement of zinc sulfide crystals created in cryostat sections from human brain biopsies: a new technique that makes it feasible to demonstrate zinc ions in tissue sections from biopsies and early autopsy material. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45:1503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Danscher G, Zimmer J. An improved timm sulphide silver method for light and electron microscopic localization of heavy metals in biological tissues. Histochemistry. 1978;55:27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Danscher G. Histochemical demonstration of heavy metals. Histochemistry. 1981;71:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frederickson CJ, Rampy BA, Reamy‐Rampy S, Howell GA. Distribution of histochemically reactive zinc in the forebrain of the rat. J Chem Neuroanat. 1992;5:521–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. You Y, Lee S, Kim T, Ohkubo K, Chae WS, Fukuzumi S, et al. Phosphorescent sensor for biological mobile zinc. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18328–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aper SJA, Dierickx P, Merkx M. Dual readout BRET/FRET sensors for measuring intracellular zinc. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:2854–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang X‐a, Lovejoy KS, Jasanoff A, Lippard SJ. Water‐soluble porphyrins as a dual‐function molecular imaging platform for MRI and fluorescence zinc sensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10780–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. You Y, Tomat E, Hwang K, Atanasijevic T, Nam W, Jasanoff AP, et al. Manganese displacement from Zinpyr‐1 allows zinc detection by fluorescence microscopy and magnetic resonance imaging. Chem Commun. 2010;46:4139–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carter KP, Young AM, Palmer AE. Fluorescent sensors for measuring metal ions in living systems. Chem Rev. 2014;114:4564–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nolan EM, Lippard SJ. Small‐molecule fluorescent sensors for investigating zinc metalloneurochemistry. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Que EL, Domaille DW, Chang CJ. Metals in neurobiology: probing their chemistry and biology with molecular imaging. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1517–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pratt EPS, Damon LJ, Anson KJ, Palmer AE. Tools and techniques for illuminating the cell biology of zinc. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2021;1868:118865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tomat E, Lippard SJ. Imaging mobile zinc in biology. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:225–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kumar N, Roopa, Bhalla V, Kumar M. Beyond zinc coordination: bioimaging applications of Zn(II)‐complexes. Coord Chem Rev. 2021;427:213550. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vinkenborg JL, Koay MS, Merkx M. Fluorescent imaging of transition metal homeostasis using genetically encoded sensors. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thompson RB. Studying zinc biology with fluorescence: ain't we got fun? Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:526–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chang CJ, Lippard SJ. Zinc metalloneurochemistry: physiology, pathology, and probes. Met Ions Life Sci. 2006;1:321–70. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burdette SC, Walkup GK, Spingler B, Tsien RY, Lippard SJ. Fluorescent sensors for Zn2+ based on a fluorescein platform: synthesis, properties and intracellular distribution. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7831–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walkup GK, Burdette SC, Lippard SJ, Tsien RY. A new cell‐permeable fluorescent probe for Zn2+ . J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5644–5. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kowalczyk T, Lin Z, Voorhis TV. Fluorescence quenching by photoinduced electron transfer in the Zn2+ sensor Zinpyr‐1: a computational investigation. J Phys Chem A. 2010;114:10427–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wong BA, Friedle S, Lippard SJ. Solution and fluorescence properties of symmetric dipicolylamine‐containing dichlorofluorescein‐based Zn2+ sensors. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7142–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khan M, Goldsmith CR, Huang Z, Georgiou J, Luyben TT, Roder JC, et al. Two‐photon imaging of Zn2+ dynamics in mossy fiber boutons of adult hippocampal slices. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:6786–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nolan EM, Lippard SJ. The Zinspy family of fluorescent zinc sensors: syntheses and spectroscopic investigations. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:8310–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nolan EM, Ryu JW, Jaworski J, Feazell RP, Sheng M, Lippard SJ. Zinspy sensors with enhanced dynamic range for imaging neuronal cell zinc uptake and mobilization. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15517–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chang CJ, Nolan EM, Jaworski J, Burdette SC, Sheng M, Lippard SJ. Bright fluorescent chemosensor platforms for imaging endogenous pools of neuronal zinc. Chem Biol. 2004;11:203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chang CJ, Nolan EM, Jaworski J, Okamoto K‐I, Hayashi Y, Sheng M, et al. ZP8, a neuronal zinc sensor with improved dynamic range; imaging zinc in hippocampal slices with two‐photon microscopy. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:6774–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nolan EM, Jaworski J, Okamoto K‐I, Hayashi Y, Sheng M, Lippard SJ. QZ1 and QZ2: rapid, reversible quinoline‐derivatized fluoresceins for sensing biological Zn(II). J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16812–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nolan EM, Jaworski J, Racine ME, Sheng M, Lippard SJ. Midrange affinity fluorescent Zn(II) sensors of the Zinpyr family: syntheses, characterization and biological imaging applications. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:9748–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Burdette SC, Frederickson CJ, Bu W, Lippard SJ. ZP4, an improved neuronal Zn2+ sensor of the Zinpyr family. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1778–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bastian C, Li YV. Fluorescence imaging study of extracellular zinc at the hippocampal mossy fiber synapse. Neurosci Lett. 2007;419:119–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Huang Z, Lippard SJ. Illuminating mobile zinc with fluorescence: from cuvettes to live cells and tissues. Methods Enzymol. 2012;505:445–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Woodroofe CC, Masalha R, Barnes KR, Frederickson CJ, Lippard SJ. Membrane‐permeable and ‐impermeable sensors of the Zinpyr family and their application to imaging of hippocampal zinc in vivo. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1659–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Radford RJ, Chyan W, Lippard SJ. Peptide‐based targeting of fluorescent zinc sensors to the plasma membrane of live cells. Chem Sci. 2013;4:3080–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Radford RJ, Chyan W, Lippard SJ. Peptide targeting of fluorescein‐based sensors to discrete intracellular locales. Chem Sci. 2014;5:4512–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chyan W, Zhang DY, Lippard SJ, Radford RJ. Reaction‐based fluorescent sensor for investigating mobile Zn2+ in mitochondria of healthy versus cancerous prostate cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:143–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zastrow ML, Huang Z, Lippard SJ. HaloTag‐based hybrid targetable and ratiometric sensors for intracellular zinc. ACS Chem Biol. 2020;15:396–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tomat E, Nolan EM, Jaworski J, Lippard SJ. Organelle‐specific zinc detection using Zinpyr‐labeled fusion proteins in live cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15776–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liu R, Kowada T, Du Y, Amagai Y, Matsui T, Inaba K, et al. Organelle‐level labile Zn2+ mapping based on targetable fluorescent sensors. ACS Sens. 2022;7:748–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zastrow ML, Radford RJ, Chyan W, Anderson CT, Zhang DY, Loas A, et al. Reaction‐based probes for imaging mobile zinc in live cells and tissues. ACS Sens. 2016;1:32–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Goldberg JM, Wang F, Sessler CD, Vogler NW, Zhang DY, Loucks WH, et al. Photoactivatable sensors for detecting mobile zinc. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:2020–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rivera‐Fuentes P, Lippard SJ. SpiroZin1: a reversible and pH‐insensitive, reaction‐based, red‐fluorescent probe for imaging biological mobile zinc. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:1238–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rivera‐Fuentes P, Wrobel AT, Zastrow ML, Khan M, Georgiou J, Luyben TT, et al. A far‐red emitting probe for unambiguous detection of mobile zinc in acidic vesicles and deep tissue. Chem Sci. 2015;6:1944–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Han Y, Goldberg JM, Lippard SJ, Palmer AE. Superiority of SpiroZin2 versus FluoZin‐3 for monitoring vesicular Zn2+ allows tracking of lysosomal Zn2+ pools. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Buccella D, Horowitz JA, Lippard SJ. Understanding zinc quantification with existing and advanced ditopic fluorescent Zinpyr sensors. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4101–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ghosh SK, Kim P, Zhang X‐a, Yun S‐H, Moore A, Lippard SJ, et al. A novel imaging approach for early detection of prostate cancer based on endogenous zinc sensing. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang X‐a, Hayes D, Smith SJ, Friedle S, Lippard SJ. New strategy for quantifying biological zinc by a modified Zinpyr fluorescence sensor. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15788–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Canzoniero LMT, Sensi SL, Choi DW. Measurement of intracellular free zinc in living neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 1997;4:275–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tomat E, Lippard SJ. Ratiometric and intensity‐based zinc sensors built on rhodol and rhodamine platforms. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:9113–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhu J‐F, Chan W‐H, Lee AWM. Both visual and ratiometric fluorescent sensor for Zn2+ based on spirobenzopyran platform. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:2001–4. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang Y, Guo X, Si W, Jia L, Qian X. Ratiometric and water‐soluble fluorescent zinc sensor of Carboxamidoquinoline with an alkoxyethylamino chain as receptor. Org Lett. 2008;10:473–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhang DY, Azrad M, Demark‐Wahnefried W, Frederickson CJ, Lippard SJ, Radford RJ. Peptide‐based, two‐fluorophore, ratiometric probe for quantifying mobile zinc in biological solutions. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:385–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Xue L, Li G, Yu C, Jiang H. A ratiometric and targetable fluorescent sensor for quantification of mitochondrial zinc ions. Chem A Eur J. 2012;18:1050–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Woodroofe CC, Won AC, Lippard SJ. Esterase‐activated two‐fluorophore system for ratiometric sensing of biological zinc(II). Inorg Chem. 2005;44:3112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Woodroofe CC, Lippard SJ. A novel two‐fluorophore approach to ratiometric sensing of Zn2+ . J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11458–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Xiong M, Yang Z, Lake RJ, Li J, Hong S, Fan H, et al. DNAzyme‐mediated genetically encoded sensors for ratiometric imaging of metal ions in living cells. Angew Chem Weinheim Bergstr Ger. 2020;59:1891–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Anderson CT, Radford RJ, Zastrow ML, Zhang DY, Apfel U‐P, Lippard SJ, et al. Modulation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors by synaptic and tonic zinc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E2705–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kalappa BI, Anderson CT, Goldberg JM, Lippard SJ, Tzounopoulos T. AMPA receptor inhibition by synaptically released zinc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:15749–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chang CJ. Searching for harmony in transition‐metal signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:744–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Budde T, Minta A, White JA, Kay AR. Imaging free zinc in synaptic terminals in live hippocampal slices. Neuroscience. 1997;79:347–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Quinta‐Ferreira ME, Matias CM. Hippocampal mossy fiber calcium transients are maintained during long‐term potentiation and are inhibited by endogenous zinc. Brain Res. 2004;1004:52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pan E, Zhang X‐a, Huang Z, Krezel A, Zhao M, Tinberg CE, et al. Vesicular zinc promotes presynaptic and inhibits postsynaptic long‐term potentiation of mossy fiber‐CA3 synapse. Neuron. 2011;71:1116–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vogt K, Mellor J, Tong G, Nicoll R. The actions of synaptically released zinc at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Neuron. 2000;26:187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Li Y, Hough CJ, Frederickson CJ, Sarvey JM. Induction of mossy fiber→CA3 long‐term potentiation requires translocation of synaptically released Zn2+ . J Neurosci. 2001;21:8015–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Huang YZ, Pan E, Xiong Z‐Q, McNamara JO. Zinc‐mediated transactivation of TrkB potentiates the hippocampal mossy fiber‐CA3 pyramid synapse. Neuron. 2008;57:546–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Opazo CM, Greenough MA, Bush AI. Copper: from neurotransmission to neuroproteostasis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lee S, Chung CYS, Liu P, Craciun L, Nishikawa Y, Bruemmer KJ, et al. Activity‐based sensing with a metal‐directed acyl imidazole strategy reveals cell type‐dependent pools of labile brain copper. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142:14993–5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dodani SC, Domaille DW, Nam CI, Miller EW, Finney LA, Vogt S, et al. Calcium‐dependent copper redistributions in neuronal cells revealed by a fluorescent copper sensor and X‐ray fluorescence microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5980–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ghosh P, Maayan G. A rationally designed peptoid for the selective chelation of Zn2+ over Cu2+ . Chem Sci. 2020;11:10127–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Radford RJ, Lippard SJ. Chelators for investigating zinc metalloneurochemistry. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:129–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kawabata E, Kikuchi K, Urano Y, Kojima H, Odani A, Nagano T. Design and synthesis of zinc‐selective chelators for extracellular applications. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:818–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shin J‐H, Jung HJ, An YJ, Cho Y‐B, Cha S‐S, Roe J‐H. Graded expression of zinc‐responsive genes through two regulatory zinc‐binding sites in Zur. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5045–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hyun HJ, Sohn JH, Ha DW, Ahn YH, Koh J‐Y, Yoon YH. Depletion of intracellular zinc and copper with TPEN results in apoptosis of cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:460–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Cao J, Bobo JA, Liuzzi JP, Cousins RJ. Effects of intracellular zinc depletion on metallothionein and ZIP2 transporter expression and apoptosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:559–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Horton TM, Allegretti PA, Lee S, Moeller HP, Smith M, Annes JP. Zinc‐chelating small molecules preferentially accumulate and function within pancreatic β cells. Cell Chem Biol. 2019;26:213–22.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Wang H, Li B, Asha K, Pangilinan RL, Thuraisamy A, Chopra H, et al. The ion channel TRPM7 regulates zinc‐depletion‐induced MDMX degradation. J Biol Chem. 2021;297:101292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Cho E, Hwang J‐J, Han S‐H, Chung SJ, Koh J‐Y, Lee J‐Y. Endogenous zinc mediates apoptotic programmed cell death in the developing brain. Neurotox Res. 2010;17:156–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zhao Y, Pan R, Li S, Luo Y, Yan F, Yin J, et al. Chelating intracellularly accumulated zinc decreased ischemic brain injury through reducing neuronal apoptotic death. Stroke. 2014;45:1139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Rivera JF, Baral AJ, Nadat F, Boyd G, Smyth R, Patel H, et al. Zinc‐dependent multimerization of mutant calreticulin is required for MPL binding and MPN pathogenesis. Blood Adv. 2021;5:1922–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Meeusen JW, Nowakowski A, Petering DH. Reaction of metal‐binding ligands with the zinc proteome: zinc sensors and N,N,N′,N′‐Tetrakis(2‐pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:3625–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zhu B, Wang J, Zhou F, Liu Y, Lai Y, Wang J, et al. Zinc depletion by TPEN induces apoptosis in human acute promyelocytic NB4 cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;42:1822–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Lee J‐M, Kim Y‐J, Ra H, Kang S‐J, Han S, Koh J‐Y, et al. The involvement of caspase‐11 in TPEN‐induced apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1871–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Rana U, Kothinti R, Meeusen J, Tabatabai NM, Krezoski S, Petering DH. Zinc binding ligands and cellular zinc trafficking: apo‐metallothionein, glutathione, TPEN, proteomic zinc, and Zn‐Sp1. J Inorg Biochem. 2008;102:489–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Huang Z, Zhang X‐a, Bosch M, Smith SJ, Lippard SJ. Tris(2‐pyridylmethyl)amine (TPA) as a membrane‐permeable chelator for interception of biological mobile zinc. Metallomics. 2013;5:648–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Weiss A, Murdoch CC, Edmonds KA, Jordan MR, Monteith AJ, Perera YR, et al. Zn‐regulated GTPase metalloprotein activator 1 modulates vertebrate zinc homeostasis. Cell. 2022;185:2148–63.e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pratt EPS, Anson KJ, Tapper JK, Simpson DM, Palmer AE. Systematic comparison of vesicular targeting signals leads to the development of genetically encoded vesicular fluorescent Zn2+ and pH sensors. ACS Sens. 2020;5:3879–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Uh K, Ryu J, Zhang L, Errington J, Machaty Z, Lee K. Development of novel oocyte activation approaches using Zn2+ chelators in pigs. Theriogenology. 2019;125:259–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Schnaars C, Kildahl‐Andersen G, Prandina A, Popal R, Radix S, le Borgne M, et al. Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of TPA‐based zinc Chelators as Metallo‐β‐lactamase inhibitors. ACS Infect Dis. 2018;4:1407–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wang S, Korenchan DE, Perez PM, Taglang C, Hayes TR, Sriram R, et al. Amino acid‐derived sensors for specific Zn2+ detection using hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chem A Eur J. 2019;25:11842–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lo MN, Damon LJ, Wei Tay J, Jia S, Palmer AE. Single cell analysis reveals multiple requirements for zinc in the mammalian cell cycle. Elife. 2020;9:e51107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zhang C, Maslar D, Minckley TF, LeJeune KD, Qin Y. Spontaneous, synchronous zinc spikes oscillate with neural excitability and calcium spikes in primary hippocampal neuron culture. J Neurochem. 2021;157:1838–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Bell CC, Han V, Sawtell NB. Cerebellum‐like structures and their implications for cerebellar function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Oertel D, Young ED. What's a cerebellar circuit doing in the auditory system? Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Apostolides PF, Trussell LO. Superficial stellate cells of the dorsal cochlear nucleus. Front Neural Circuits. 2014;8:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Frederickson CJ, Howell GA, Haigh MD, Danscher G. Zinc‐containing fiber systems in the cochlear nuclei of the rat and mouse. Hear Res. 1988;36:203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Perez‐Rosello T, Anderson CT, Ling C, Lippard SJ, Tzounopoulos T. Tonic zinc inhibits spontaneous firing in dorsal cochlear nucleus principal neurons by enhancing glycinergic neurotransmission. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;81:14–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Buck L, Axel R. A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell. 1991;65:175–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. de March CA, Kim S‐K, Antonczak S, Goddard WA III, Golebiowski J. G protein‐coupled odorant receptors: from sequence to structure. Protein Sci. 2015;24:1543–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ache BW, Young JM. Olfaction: diverse species, conserved principles. Neuron. 2005;48:417–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Axel R. Scents and sensibility: a molecular logic of olfactory perception (Nobel lecture). Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:6110–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Nagayama S, Homma R, Imamura F. Neuronal organization of olfactory bulb circuits. Front Neural Circuits. 2014;8:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Blakemore LJ, Trombley PQ. Zinc as a neuromodulator in the central nervous system with a focus on the olfactory bulb. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:297. 10.3389/fncel.2017.00297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Jo SM, Won MH, Cole TB, Jensen MS, Palmiter RD, Danscher G. Zinc‐enriched (ZEN) terminals in mouse olfactory bulb. Brain Res. 2000;865:227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Mook Jo S, Kuk Kim Y, Wang Z, Danscher G. Retrograde tracing of zinc‐enriched (ZEN) neuronal somata projecting to the olfactory bulb. Brain Res. 2002;956:230–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Blakemore LJ, Tomat E, Lippard SJ, Trombley PQ. Zinc released from olfactory bulb glomeruli by patterned electrical stimulation of the olfactory nerve. Metallomics. 2013;5:208–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Blakemore LJ, Trombley PQ. Diverse modulation of olfactory bulb AMPA receptors by zinc. Neuroreport. 2004;15:919–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Galin MA, Nano HD, Hall T. Ocular zinc concentration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1962;1:142–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Ugarte M, Osborne NN. Zinc in the retina. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;64:219–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Redenti S, Chappell RL. Localization of zinc transporter‐3 (ZnT‐3) in mouse retina. Vision Res. 2004;44:3317–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Márquez García A, Salazar V, Lima Pérez L. Consequences of zinc deficiency on zinc localization, taurine transport, and zinc transporters in rat retina. Microsc Res Tech. 2022;85:3382–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Ugarte M, Osborne NN. The localization of free zinc varies in rat photoreceptors during light and dark adaptation. Exp Eye Res. 1999;69:459–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Redenti S, Chappell RL. Neuroimaging of zinc released by depolarization of rat retinal cells. Vision Res. 2005;45:3520–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Ripps H, Chappell RL. Review: Zinc's functional significance in the vertebrate retina. Mol Vis. 2014;20:1067–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Gottesman J, Miller RF. Pharmacological properties of N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptors on ganglion cells of an amphibian retina. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Osborne NN, Herrera AJ. The effect of experimental ischaemia and excitatory amino acid agonists on the GABA and serotonin immunoreactivities in the rabbit retina. Neuroscience. 1994;59:1071–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Wu SM, Xiaoxi Q, Noebels JL, Xiong Li Y. Localization and modulatory actions of zinc in vertebrate retina. Vision Res. 1993;33:2611–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Ugarte M, Osborne NN. The localization of endogenous zinc and the in vitro effect of exogenous zinc on the GABA Immunoreactivity and formation of reactive oxygen species in the retina. Gen Pharmacol. 1998;30:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Shen Y, Yang X‐L. Zinc modulation of AMPA receptors may be relevant to splice variants in carp retina. Neurosci Lett. 1999;259:177–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Dong CJ, Werblin FS. Zinc downmodulates thf GABAc receptor current in cone horizontal cells acutely isolated from the catfish retina. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:916–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Han M‐H, Yang X‐L. Zn2+ differentially modulates kinetics of GABACvs GABAA receptors in carp retinal bipolar cells. Neuroreport. 1999;10:2593–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Qian H, Li L, Chappell RL, Ripps H. GABA receptors of bipolar cells from the skate retina: actions of zinc on GABA‐mediated membrane currents. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:2402–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Kaneda M, Ishii K, Akagi T, Tatsukawa T, Hashikawa T. Endogenous zinc can be a modulator of glycinergic signaling pathway in the rat retina. J Mol Histol. 2005;36:179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Han Y, Wu SM. Modulation of glycine receptors in retinal ganglion cells by zinc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3234–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Li P, Yang X‐L. Zn2+ differentially modulates glycine receptors versus GABA receptors in isolated carp retinal third‐order neurons. Neurosci Lett. 1999;269:75–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Luo D‐G, Li G‐L, Yang X‐L. Zn2+ modulates light responses of color‐opponent bipolar and amacrine cells in the carp retina. Brain Res Bull. 2002;58:461–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Luo D‐G, Yang X‐L. Zn2+ differentially modulates signals from red‐ and short wavelength‐sensitive cones to horizontal cells in carp retina. Brain Res. 2001;900:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Land PW, Shamalla‐Hannah L. Transient expression of synaptic zinc during development of uncrossed retinogeniculate projections. J Comp Neurol. 2001;433:515–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Li Y, Andereggen L, Yuki K, Omura K, Yin Y, Gilbert HY, et al. Mobile zinc increases rapidly in the retina after optic nerve injury and regulates ganglion cell survival and optic nerve regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E209–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Choi J‐S, Kim K‐A, Yoon Y‐J, Fujikado T, Joo C‐K. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase‐2 expression by zinc‐chelator in retinal ischemia. Vision Res. 2006;46:2721–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Land PW, Aizenman E. Zinc accumulation after target loss: an early event in retrograde degeneration of thalamic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:647–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Wong WL, Su X, Li X, Cheung CMG, Klein R, Cheng C‐Y, et al. Global prevalence of age‐related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e106–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Fleckenstein M, Keenan TDL, Guymer RH, Chakravarthy U, Schmitz‐Valckenberg S, Klaver CC, et al. Age‐related macular degeneration. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Newsome DA, Swartz M, Leone NC, Elston RC, Miller E. Oral zinc in macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Seddon JM, Hennekens CH. Vitamins, minerals, and macular degeneration: promising but unproven hypotheses. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:176–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Age‐Related Eye Disease Study Research Group . A randomized, placebo‐controlled, clinical trial of high‐dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age‐related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report No. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Heesterbeek TJ, Rouhi‐Parkouhi M, Church SJ, Lechanteur YT, Lorés‐Motta L, Kouvatsos N, et al. Association of plasma trace element levels with neovascular age‐related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2020;201:108324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Lengyel I, Flinn JM, Pető T, Linkous DH, Cano K, Bird AC, et al. High concentration of zinc in sub‐retinal pigment epithelial deposits. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:772–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Pao P‐J, Emri E, Abdirahman SB, Soorma T, Zeng H‐H, Hauck SM, et al. The effects of zinc supplementation on primary human retinal pigment epithelium. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2018;49:184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Sanford L, Carpenter MC, Palmer AE. Intracellular Zn2+ transients modulate global gene expression in dissociated rat hippocampal neurons. Sci Rep. 2019;9:9411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Li J, Ho DJ, Henault M, Yang C, Neri M, Ge R, et al. DRUG‐seq provides unbiased biological activity readouts for neuroscience drug discovery. ACS Chem Biol. 2022;17:1401–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]