Abstract

Objectives

This psychobiography focuses on the advocacy work of Natasha Keating, a trans woman incarcerated in two male prisons in Australia between 2000 and 2007. Incarcerated trans women are a vulnerable group who experience high levels of victimization and discrimination. However, Natasha advocated for her rights while incarcerated and this advocacy contributed to substantial changes in the carceral system. This psychobiography uses psychological understandings of resilience as well as the Transgender Resilience Intervention Model (TRIM) to investigate the factors that enabled this advocacy.

Method

Data consisted of an archive of letters written by Natasha and interviews with individuals who knew her well. This psychobiography was guided by du Plessis' (2017) 12‐step approach and included the identification of psychological saliencies and the construction of a Multilayered Chronological Chart.

Results

Natasha's life is presented in four chapters, with each chapter including a discussion of resilience based on the TRIM.

Conclusions

The TRIM suggests that during incarceration, Natasha was able to access more group‐level resilience factors than at any other time in her life. This, combined with individual resilience factors, enabled her advocacy. This finding has implications for advocacy in general as it highlights the importance of both individual‐ and group‐level factors in enabling individuals to effectively advocate for change in their environments.

Keywords: Australia, incarceration, psychobiography, resilience, social justice, trans woman, transgender resilience intervention model, TRIM

1. INTRODUCTION

Natasha Keating had long blonde hair that cascaded down her back, she loved wearing beautiful clothes, and was an expert at applying makeup. As a child growing up in the Central Highlands of Victoria (Australia), she fantasized about a future in which she might work as a makeup artist. However, Natasha was never able to fulfill her dreams and instead spent a large portion of her adult life incarcerated in two men's prisons where as a trans woman she experienced indifference, victimization, and discrimination throughout the entirety of her incarceration (2000–2007). Despite these pervasive negative experiences while incarcerated, Natasha acted as an effective agent of social change and became a vocal advocate for her own health and rights in terms of access to gender‐affirming supports and care (clinical/medical, use of correct name and pronoun), clothing, grooming, hygiene, and commissary items (including female undergarments). Natasha was, thus, able to express her gender and receive suitable accommodation/housing assignment in line with her heightened vulnerability. Her work counter to the system, while held within the system, paved the way for important future policy and procedure revisions within the carceral system for trans persons in Queensland, Australia. Unfortunately, on her release from incarceration, Natasha returned to illicit substance use to cope with the trauma she experienced and she died by suicide when she was 31.

This psychobiography is written to honor Natasha and aims to provide a psychological explanation for how, despite experiences of numerous hardships throughout her life, she was able to advocate fiercely for herself (and ultimately for others) while she was incarcerated. Natasha's advocacy is particularly notable given that the other elements of her story, such as victimization from a young age; turning to street economies (such as sex work for economic survival); using illicit substances; experiencing multiple periods of incarceration; and making several suicide attempts and eventual death by suicide; are tragically commonplace for many trans women (Grant et al., 2011; Hughto et al., 2022; Mizock & Mueser, 2014; Nemoto et al., 2011; White Hughto et al., 2015; Ybarra et al., 2014). Natasha's ability to override this dominant marginalized and victimized narrative and express herself in an agentic and forceful way with integrity has implications for our understanding not only of Natasha's life but also of how to best support and affirm trans women within (and beyond) incarceration settings. While portrayals of trans individuals in the popular media tend to present these individuals in stereotypical ways either as pathological (McLaren et al., 2021) or embodying an authenticity of identity (Lovelock, 2016), what this psychobiography of Natasha provides is a more nuanced and in‐depth portrayal of a complex and courageous individual. Natasha's story also illustrates how a single individual's spirit, determination, and resilience can have a lasting, ripple effect for a community. Although Natasha's self‐advocacy did not ultimately improve her own future, it laid the groundwork for changing the living conditions of incarcerated trans women in Queensland, Australia.

1.1. Experiences of incarcerated trans women

In most countries, including Australia, incarceration settings are segregated by the person's sex assigned at birth (i.e., male or female setting). As a result, trans women who are not legally recognized as women are typically incarcerated in carceral settings intended for men (Brömdal, Clark, et al., 2019; Brömdal, Mullens, et al., 2019; Brömdal et al., 2022; Redcay et al., 2020; Van Hout et al., 2020; White Hughto et al., 2018;). This classification accords with medicalized views of being trans, which historically viewed trans individuals as medically deviant, labeling them initially as transexual (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1980) and subsequently as suffering from Gender Identity Disorder (APA, 1994). The World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH) standards of care (which were first published in 1979) are aimed at assisting trans individuals with gender‐affirming care; however, these guidelines remain firmly based on the medical cis‐normative model where being trans is viewed as deviant (Franks et al., 2022; Ker et al., 2021; Schulz, 2018; Shepherd & Hanckel, 2021).

Research has shown that incarcerated trans women experience victimization, misgendering/misnaming, as well as physical and sexual assault while incarcerated, at the hands of other incarcerated persons and correctional staff (Grant et al., 2011; Hughto et al., 2022; Lydon et al., 2015; Reisner, White Hughto, et al., 2015). Incarcerated trans women are, therefore, a vulnerable priority group (Brömdal et al., 2022; Brömdal, Clark, et al., 2019; Brown, 2014) who experience significant mistreatment, victimization, and indifference due to structural stressors and who thus require additional measures of support and resources, including protection to uphold their rights and health while incarcerated.

The authors of this paper are concerned about the effects of discriminatory and inhumane trans incarceration policies and practices and are committed to documenting the lived experiences of trans women who have been or who are incarcerated in order to promote social change by supporting and upholding the human rights and health of incarcerated trans persons. While we acknowledge the impact of incarceration on both trans men and trans women, this paper forms part of a larger body of scholarship focusing specifically on the experiences of incarcerated trans women in Australia, as they are disproportionately affected by discrimination, violence, and other forms of victimization (Swan et al., 2022), placing trans women at higher risk of arrest and incarceration (Brömdal et al., 2022; Brömdal, Clark, et al., 2019; Brömdal, Mullens, et al., 2019; Halliwell et al., 2022, 2023; Hughto et al., 2022; Phillips et al., 2020; Sanders et al., 2022). Our scholarship spans disciplines of clinical and health psychology, gender and trans studies, sociology, literary and historical narrative, education, public health, and critical policy analysis. The authors have been intimately engaged in trans rights and health research, and advocacy within and beyond the context of carceral settings for up to 25 years, and collectively the authorship team has over 50 years of experience within the fields. As critical analysts, trans rights and health scholars, allies, and clinicians, we include trans and cis‐gender researchers with lived experiences of incarceration. Our authorship spans sexual orientations (gender queer, pansexual, heterosexual), immigration statuses (immigrant, first generation, Native born), ethnic and cultural background (North African descent, White Australian, White North American, and White European descent), language statuses (English as an additional language, English as a first language), and class backgrounds (working class, middle class, and upper middle class). We are all personally and professionally transparent about our individual and collective commitment to dismantling the oppression and injustices trans women experience while incarcerated in Australia, and elsewhere in the world.

1.2. Psychobiographical framework

Psychobiographical studies use psychological theories and frameworks to understand individual lives (du Plessis, 2017). This form of research traditionally focuses on public figures such as politicians (e.g., McAdams, 2021), artists (e.g., Harisunker & du Plessis, 2021; Panelatti et al., 2021), religious leaders (e.g., Saccaggi, 2015), and/or psychologists/theorists (e.g., Bushkin et al., 2021). This is because psychobiography sets as its task the “understanding of persons” (Schultz, 2005c, p. 2003) who are in some way extraordinary or exemplary, and this extraordinariness often equates to widespread public recognition or notoriety. However, extraordinary individuals also exist outside of the public eye and these individuals often have a large impact on their sphere of existence without ever coming to the attention of the public. Natasha Keating is one such person and an illustrative agent of social change.

As scholars familiar with the incarceration policy and practice affecting trans women in Australia and globally, we are also familiar with the stories of trans women's incarceration experiences (Brömdal, Clark, et al., 2019; Brömdal, Mullens, et al., 2019; Phillips et al., 2020). Thus, when we first encountered Natasha's story, we were immediately struck by the fact that it was notably different from many of the other incarceration narratives we had explored. Natasha's method of self‐advocacy while incarcerated in two men's facilities was notable and rich; from the perspective of being a social change agent, it ran contrary to what was reported in the existing literature (see, for example, Grant et al., 2011; Lydon et al., 2015) as well as in our own research (Brömdal, Clark, et al., 2019; Brömdal, Mullens, et al., 2019; Phillips et al., 2020). Natasha's epistolary documentation of her self‐advocacy allows us to track the processes through which she was able to demand changes to address her own and broader trans needs in incarceration.

As part of our larger research program, we initially undertook a critical discourse analysis (CDA) of a corpus of 121 letters written by Natasha with the aim of investigating how she was able to advocate for her rights and health as a trans woman incarcerated in two male correctional facilities (Halliwell et al., 2022). The analysis focused on the discursive and linguistic strategies Natasha used to construct a sense of self while incarcerated and identified that Natasha created a positive self‐identity through the discourse used in the letters. A second discursive paper (Halliwell et al., 2023) followed, focusing on the cognitive transformation from a critical discursive perspective. These two CDA papers were able to address the mechanics (the “how”) of Natasha's advocacy, but questions remained concerning the psychological factors (the “why”) that enabled Natasha to pursue these discursive and linguistic strategies to provoke and promote personal and wider social change.

Attempting to provide a psychological explanation for a central question or mystery in an individual's life is the starting point of most psychobiographical research (Schultz, 2005a). This central mystery, as well as the extraordinary nature of her actions while incarcerated, suggested that a psychobiography would be an appropriate research method to further investigate Natasha's life and legacy, even though she was not a “traditional” psychobiographical subject. This study is, therefore, framed as a psychobiography of Natasha Keating, with a focus on the central mystery of understanding the psychological factors that contributed to her resilience and fervent determination and allowed her to act as an agent of social change while incarcerated.

1.3. Psychological frame – Resilience and the transgender resilience intervention model

The concept of psychological resilience relates to the ability to “bounce back” or effectively cope in adverse situations (Aranda et al., 2012; Hillier et al., 2020). Resilience is, therefore, related to both an individual trait (“bouncing back”) and to the presence of negative circumstances (the adverse situation) (Aranda et al., 2012). In this way, it is similar to the concept of situated agency (Hillier et al., 2020), which views an individual's choices as constrained by the circumstances and institutions with which they interact. In addition, research suggests that resilience includes aspects of cognitive transformation (Tebes et al., 2004) and as such is characterized by qualitative and quantitative changes in individuals' cognitive processes and may be related to post‐traumatic growth (Mehta et al., 2022).

The Transgender Resilience Intervention Model (TRIM; Matsuno & Israel, 2018) provides a way to categorize factors that relate to an individual's expression of resilience in any given setting. The model was selected for use in this psychobiography because its clear delineation of factors served as a framework for exploring Natasha's resilience and determination in incarceration. The model is based on minority stress theory (Meyer, 2015), which theorizes that individuals from stigmatized and marginalized minority groups are exposed to high levels of stress due to their minority position in society. Minority stress theory differentiates between distal stressors, which are external to an individual and include experiences of victimization and discrimination, and proximal stressors, which are internal experiences that develop as a result of experiencing distal stressors, for example, fear and anxiety relating to the anticipation of possible victimization or discrimination (Grant et al., 2011; Meyer, 2015). Recent research suggests that trans individuals are particularly vulnerable to minority stress due to their experience of widespread prejudice, discrimination, and violence (White Hughto et al., 2015).

Matsuno and Israel's (2018) TRIM expands on the concept of proximal and distal stressors by identifying specific group and individual resilience factors relevant to trans individuals that are known to buffer these stressors. Group‐level resilience factors relate to resources in the community that can help individuals manage minority stress (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005), whereas individual‐level resilience factors are qualities possessed by an individual (Matsuno & Israel, 2018). Individual‐ and group‐level factors are related, as the presence of group resilience factors is likely to lead to an increase in individual resilience; for example, having a positive role model can contribute to increased positive self‐definition (Matsuno & Israel, 2018). Each factor is briefly described in Table 1. For each factor, a definition is provided as well as a summary of the positive outcomes linked to the factor. All information in Table 1 is drawn from Matsuno and Israel (2018).

TABLE 1.

Resilience factors in the transgender resilience intervention model

| Factor | Definition | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group‐level factors | Social support | Support from friends, family, and significant others | Associated with lower levels of distress for trans individuals. |

| Community belonging | A sense of belonging within the LGBTIQ+ community | Buffers rejection and increases well‐being. Decreases anxiety and depression. | |

| Family support | Acceptance from family of origin, especially parents | Higher life satisfaction and self‐esteem. Lower levels of depression and attempted suicide. | |

| Involvement in trans advocacy | Active involvement in advocacy | Increases access to resources such as health care. | |

| Having positive role models | The presence of visible positive role models | Lower levels of psychological distress. | |

| Being a positive role model | Acting as a positive role model to others | Buffers against acting on suicidal ideation. Sense of responsibility to model good behavior to others. | |

| Individual‐level factors | Self‐worth | Having a positive view of one's own identity as trans | Associated with decreased psychological distress. |

| Hope | Having an optimistic viewpoint | Helps to manage stress associated with rejection and discrimination. | |

| Positive self‐defined identity | The ability to generate one's own definition of self not bound by conventional gender norms | Sense of empowerment and the ability to cope better with discrimination. | |

| Transition | Being able to transition either medically or socially to the extent which an individual desires to transition | Improved mental health outcomes. Protects against suicide. |

2. METHOD

This study and its methods were pre‐registered in Open Science Framework in May 2021. The pre‐registration helped to determine the scope of the project by outlining the data that would be available to be used in the study; it also provided an initial psychological framework for analysis, although this framework was eventually not used (an explanation for this is provided later in this section). The research process generally followed the 12‐step approach to psychobiographical research outlined by du Plessis (2017), which was adapted (as described below) to suit the specific requirements of this study. In particular, the four phases of data collection, data condensation, data display, and conclusion drawing collectively informed the process followed in writing this psychobiography.

2.1. Data collection

Ethical approval was received from The University of Southern Queensland's Human Research Ethics Committee (H19REA236) to conduct this study. In addition, ethical approval was received to use Natasha's real name in publications about her. The decision to make Natasha's identity public was based on her own expressed wishes; the following extract is taken from a letter she wrote dated February 13, 2006: “I …. give … full permission … to use my known alias of “NATASHA” … [in] anyway you see fit to better educate and inform people on the issues, facing transgender people and the transgender community.” Use of her real name was further supported via direct communication with her mother Peggy, and Gina Mather and Kristine (Krissy) Johnson from the Australian Transgender Support Association of Queensland (henceforth ATSAQ) who donated the corpus of letters to an Australian archive. Peggy, Gina, and Krissy also requested that their real names be used in all publications related to Natasha and they are, therefore, named in this paper consistent with their stated wishes. However, the names of other individuals associated with Natasha who have not consented to be identified have been altered to protect their identities.

The first dataset relating to Natasha consisted of a corpus of letters written by her between 2002 and 2007 while she was incarcerated. It is this corpus of letters that was used in the CDA study mentioned previously (Halliwell et al., 2022) as well as in a subsequent book chapter focusing on the use of military metaphor in Natasha's cognitive transformation (Halliwell et al., 2023). The archive consists of 162 documents that Natasha either wrote to (121 documents) or received from (41 documents) various individuals (e.g, friends, support agencies) within and outside of the carceral system in Australia with most of the documents spanning the period October 2005 to August 2006 (Table 2). The original copies of these documents are located at a public library in Australia and remain in the public domain. The letters were initially accessed by A. Brömdal, who copied and digitized the documents and shared them with the research team. The table below, which is reproduced from Halliwell et al. (2022), details the contents of the archive.

TABLE 2.

Contents of Natasha Keating archive

| Document type | Number of letters sent by Natasha Keating | Number of letters received by Natasha Keating |

|---|---|---|

| Higher legal authority – Anti‐Discrimination Commission/Council for Civil Liberties/QLD Ombudsman/Supreme Court | 20 | 13 |

| Australian Transgender Support Association of Queensland – ATSAQ | 32 | 1 |

| Carceral service – Department of Corrective Services | 18 | 7 |

| Correctional Center General Managers | 25 | 10 |

| Legal correspondence with independent counsel | 7 | 0 |

| Medical correspondence with independent physicians and authorities | 3 | 2 |

| Grievance particulars, incidents, and write‐ups | 11 | 0 |

| Request for policies and documents | 4 | 1 |

| Policy documents and notices | 0 | 2 |

| Newspaper articles and material intended for publication | 1 | 3 |

| Property seizure notices | 0 | 2 |

In addition to the archival material, two interviews were conducted specifically for this psychobiography. Both interviews were conducted in early 2021 by three members of the research team who explained the aims of the psychobiography, including their trans rights and health academic advocacy positionality. The first interview was with Peggy, Natasha's mother, and was conducted by A. Brömdal and A. B. Mullens. The second interview was with Gina Mather and Kristine (Krissy) Johnson and was conducted by A. Brömdal and S. D. Halliwell. Gina is the president and Krissy is the secretary of ATSAQ. Gina and Krissy were also close friends of Natasha and the original custodians of the letters described above. These three individuals were the most central long‐term sources of support in Natasha's life and are thus appropriate key informants for her story and legacy. After providing informed consent, Peggy, Gina, and Krissy engaged in deeply humanizing and empowering conversations with the interviewers exploring Natasha's life within and outside the prison walls, and the authors were offered access to immensely rich, sensitive, and varied stories of Natasha by the three participants.

In addition to the primary data sources listed above, it was also important for the psychobiography that Natasha's life be situated in context (du Plessis, 2017). This context involves both laws and practices relating to the incarceration of trans women in Australia as well as the development of support organizations such as ATSAQ. This information was compiled by the team members, particularly A. Brömdal, who is an expert in this field, and the information was verified by Gina and Krissy, who are the founders of ATSAQ and have been advocating for trans rights and health in Queensland, Australia since 1990.

2.2. Data condensation and data display

The first step in data condensation involved identifying psychologically salient material (Alexander, 1990; Schultz, 2005b) within the archive of letters, as well as within the transcripts of biographical interviews conducted. The material was viewed as psychologically salient based on Alexander's (1990) indicators of frequency, primacy, emphasis, isolation, uniqueness, incompletion, error or omission, and negation. These indicators are defined in the Table 3 below.

TABLE 3.

Indicators of psychological salience

| Frequency | Repeated events, themes, scenes, patterns, etc. |

| Primacy | What is mentioned or noted first within a text |

| Emphasis | That which stands out in some way, either by over, under, or misplaced emphasis |

| Isolation | Material that appears to not be in keeping with the remainder of the text |

| Uniqueness | Material that is marked by the subject as unprecedented or somehow, especially singular |

| Incompletion | Missing details, avoidance |

| Error, distortion, omission | Incorrect details, half‐truths, etc. |

| Negation | Strenuous disavowal, especially in the absence of any positive assertion to the contrary |

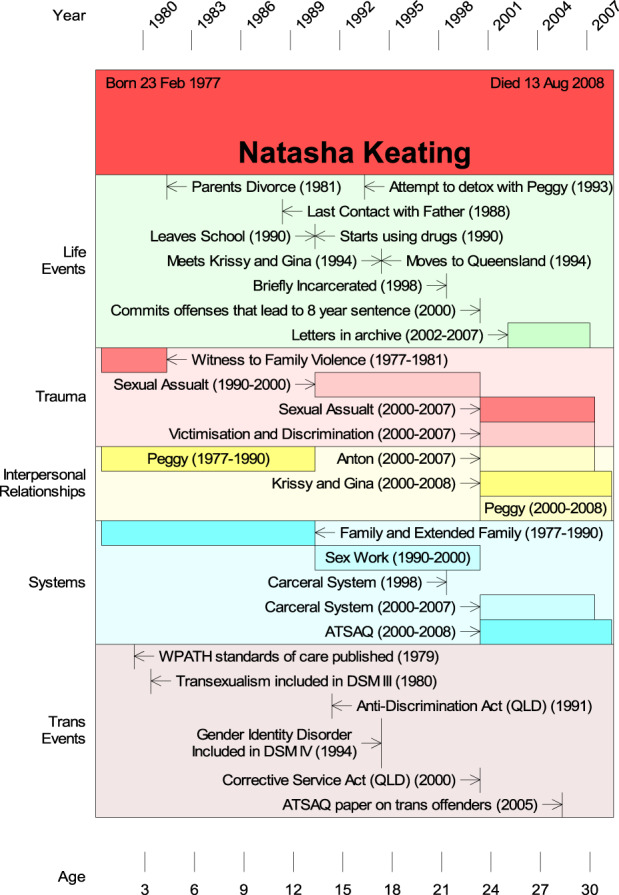

An initial thematic analysis of the archival material was conducted by S. D. Halliwell and this thematic analysis was then checked by the remaining members of the research team. Based on this initial thematic analysis, the first author, C. du Plessis, who is an experienced psychobiographer as well as a clinical psychologist, undertook the identification of psychological saliencies within the archive of letters. Following a discussion with the interviewers (A. Brömdal, S. D. Halliwell, and A. B. Mullens) about the themes in the interviews, C. du Plessis then further explored psychologically salient materials in the interviews. The psychologically salient material was used to construct a narrative psychological biography of Natasha, which was discussed with all team members, and is presented in the results section. In the analysis, four distinct “chapters” were identified in Natasha's life, each with its own psychological characteristics. In addition to these narrative “chapters”, underlying psychological themes were identified within Natasha's life: interpersonal relationships, trauma, and positioning within systems. These themes are represented as layers in the multilayered chronological chart (MCC: Hiller, 2011) included in the results section (Figure 1). The use of the MCC allows for the presentation of the intersection of various aspects of Natasha's life, as well as for positioning Natasha's experiences within the wider sociocultural and political context (Ponterotto & Reynolds, 2013) of trans rights and health in Australia and internationally.

FIGURE 1.

Multilayered chronological chart for Natasha Keating (1977–2008) created with Genelines™

2.3. Conclusion drawing

The conclusion drawing stage involved linking the psychologically salient material identified in the previous step with psychological theory. In the initial pre‐registration, it was proposed that Bronfenbrenner's ecological model be used as the explanatory framework—the inclusion of a theoretical framework as part of the data collection phase is in accordance with the steps proposed by du Plessis (2017). However, following the analysis process, it was decided that this theory did not sufficiently foreground the individual characteristics that resulted in Natasha's advocacy. Therefore, an alternate framework was sought, and the TRIM was selected as the group‐ and individual‐level factors included in this model allowed for the further exploration of the psychological themes of interpersonal relationships and positioning within systems that had been identified in our analysis.

In writing the psychobiography, we took care to avoid a pathography or deficits focus (Schultz, 2005a) by ensuring that we did not focus exclusively on aspects of Natasha's experience such as her illicit drug use or suicide, or be inadvertently pejorative in nature. Instead, we followed Ponterotto's (2014) guidelines for best practice, being explicit about our positionality as scholar advocates, being transparent about the research process followed, and the way the conclusions were drawn; and by virtue of a strength‐based approach.

3. RESULTS – A NARRATIVE PSYCHOBIOGRAPHY OF NATASHA KEATING

3.1. Chapter 1: Childhood (1977–1990)

Natasha Keating was born Shannon Richard Keating on February 23, 1977 in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia, and was presumed male on her birth certificate. She was the youngest of three children. Natasha's father was physically and financially abusive toward her mother, Peggy, which resulted in the couple divorcing in 1981. Natasha's relationship with Peggy appears to be an important protective factor in her childhood, and Peggy described their bond as strong and secure. Further to this, Peggy shared how she remembers Natasha as an “easy and good 1 ” child who loved cuddles, swimming, and volleyball (interview with Peggy).

Natasha was about 4‐year old when her mother first noted that she did not display “typical boy behavior” (interview with Peggy) and showed a preference for “girls' toys” and makeup. Peggy was supportive of Natasha's identity throughout her childhood, and she described it as follows: “He had a lovely personality. You know, he just grew up and became what she became. And, I suppose that's the tapestry of life” (interview with Peggy). Natasha's early expression of her gender identity is consistent with existing literature, which shows that most trans children are aware of their gender identity from a very early age (Pullen Sansfaçon et al., 2020).

The support that Natasha received from her mother during her childhood is an example of the group‐level factor of family support within the TRIM (Matsuno & Israel, 2018). However, none of the other group‐level factors that promote resilience, such as community belongingness or having positive trans role models, were present in Natasha's childhood. Trans identity was not commonly acknowledged in Australia in the 1970s and 1980s and it is likely that the only exposure Natasha would have had to other trans people would be through media reports, which often ran in tabloid newspapers, and which were written in an exploitative and negative manner and designed to shock (Riseman, 2021). At the time, trans identity was termed transsexualism and was pathologized through its inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) III (APA, 1980). Thus, it is likely that Natasha would have experienced a sense of social exclusion and marginalization in relation to her identity. However, it is important to note that there is significant evidence to suggest that family support is one of the most important factors contributing to the development of resilience (Matsuno & Israel, 2018; Telfer et al., 2020).

With regard to the individual‐level factors included in the TRIM, the ability to transition is an important aspect of resilience (Matsuno & Israel, 2018). While limited, trans youth in Australia now have access to gender‐affirming care such as hormone blockers (Telfer et al., 2020). This was not the case in the 1970s and 1980s when Natasha was a child. Thus, the only resilience factor that can be identified in Natasha's childhood is the support and affirmation she received from her mother; and it seems likely that this may have provided a foundation for the development of resilience in her later life.

3.2. Chapter 2: Adolescence (1990–1999)

At the age of 13, Natasha refused to attend school, possibly (according to Peggy) due to being teased about her increasingly open trans identity. She identified strongly with the singer Madonna and wore women's clothes and makeup. Although she never overtly told her mother that she was a trans woman, it was during this time that she began to use the name Natasha, a name that began as a joking reference to herself as “Natasha the Flasher”. Her idolization of Madonna and increasingly public self‐presentation as feminine marked the beginning of her public identity transition.

Natasha started using illicit drugs, such as heroin, soon after she left school. She moved away from home and appears to have started to engage in sex work for economic survival. She lost contact with her mother Peggy as well as with her sisters and extended family. She was incarcerated several times, for charges including illicit substance use, fraud, and solicitation. Peggy also believes that Natasha experienced sexual assault during this time: “she knew she didn't have to tell me … she knew I just knew” (interview with Peggy).

In the mid‐1990s, Natasha met Gina and Krissy, who were to play an important role in her later advocacy. She attended a few meetings of ATSAQ and they remember her as a shy young woman who appeared lonely and did not seem to have friends. She impressed them as being very intelligent and very interested in “legal ways to help move the community forward” (Krissy; interview with Krissy and Gina). Natasha also frequently spoke about her dream of one day having “a husband, adopting children. White picket fence, you know” (Krissy; interview with Krissy and Gina). Prior to meeting Krissy and Gina, Natasha had already undertaken hormone therapy 2 to begin her gender‐affirmation process and had developed breasts and she desperately wanted to have genital gender‐affirming surgery as she believed this would enable her to fulfill her dream—“She wanted the op. That's about the only thing she'd always say, I need the op …. Because she was such a pretty girl and she wanted to be the woman she wanted to be” (Gina; interview with Krissy and Gina). After visiting approximately five or six times, Natasha suddenly disappeared, and Gina and Krissy did not hear from her for several years.

This period of Natasha's life is sadly typical of the adolescent experience of many trans individuals. Research suggests that Natasha's experiences of extended family rejection, social exclusion, discrimination, and victimization due to being trans are commonplace for trans adolescents and adults (including discriminatory attitudes held by health professionals; see Mullens et al., 2017), and have been shown to be associated with depression, anxiety, and post‐traumatic stress symptoms (Hughto et al., 2022; White Hughto et al., 2015; Ybarra et al., 2014). Many trans people report using alcohol and other drugs to cope with the psychological implications of family rejection, social exclusion, discrimination, and victimization (Grant et al., 2011; Hughto et al., 2022; Mizock & Mueser, 2014; Nemoto et al., 2011; Reisner, Pardo, et al., 2015), which in turn can place trans persons at greater risk for arrest and incarceration. The aforementioned factors may also restrict access to material and financial recourses, including employment and housing, leading some trans persons to turn to street economies, such as sex work, for economic survival (Grant et al., 2011; Hughto et al., 2022; Mizock & Mueser, 2014; Nemoto et al., 2011). Indeed, studies report that sex work is the central predictor of incarceration for trans women across their life span (Hughto et al., 2022; White Hughto et al., 2019). Biased policing practices, including differential targeting of gender minorities, particularly trans women, also translate to trans women being at heightened risk for arrest and incarceration (Brömdal, Clark, et al., 2019; Brömdal, Mullens, et al., 2019; Glezer et al., 2013; Grant et al., 2011; Hughto et al., 2022; Wolff & Cokely, 2007).

The above research findings paint a grim picture of the possibilities available to Natasha at this time in her life, and this grim outlook is echoed in the application of the TRIM (Matsuno & Israel, 2018) to this chapter of Natasha's life. In terms of group factors, there is evidence of some limited family support (prior to her estrangement from her mother), and some limited social support and positive role models through her interaction with ATSAQ. In terms of individual‐level factors, her hormone therapy and her use of the name Natasha can be viewed as partial gender affirmation, and her dream of the “white picket fence” speaks to the resilience factor of hope. However, on the whole, the application of the TRIM to this chapter of Natasha's life does not portray her as particularly resilient and instead, we are left with a vision of a young Natasha who is very much the victim of her circumstances.

However, a broader understanding of resilience as a situated and temporal (Aranda et al., 2012) phenomenon allows for a more nuanced reading of this period in Natasha's life. From this perspective, many of Natasha's choices can be viewed as agentic responses to adverse circumstances. For example, it is well established that Madonna offered a vision of gender‐fluid femininity (de Jesus, 2021) in the 1990s that counteracted mainstream views of femininity, and Natasha's identification with the singer thus speaks to her awareness of the existence of alternative narratives of being a woman, including expressing and embodying femininity. This cognitive flexibility is reminiscent of Tebes et al.’s (2004) conceptualization of cognitive transformation, which suggests that the ability to re‐interpret and re‐evaluate events is a crucial component of resilience. We have elsewhere (Halliwell et al., 2023) argued that Natasha displayed cognitive transformation during her time in incarceration, but our analysis here suggests that she was already displaying elements of cognitive transformation and resilience prior to her incarceration.

While Natasha's desire for a “husband”, “children”, a “white picket fence”, supposed women's clothing and makeup, and gender‐affirming hormones and surgery could be assumed to be representative of a transnormative subjectivity that reifies a gender binary (Johnson, 2016); this conceptualization of Natasha's gender relies on a belief that gender sits neatly within an intelligible cis‐normative frame (Stryker et al., 2008). Trans outside this fixed space provided Natasha with unlimited choice regarding gender expression, and embodiment. Natasha was a self‐proclaimed woman, but even in this place, her gender is not reducible to a cis conceptualization of woman. Considering that more broadly, societal conceptualizations of trans expect a predictable iteration of woman and yet at the same time punishes trans women for being/attempting to be this woman, Natasha's demand for her own subjectivity arguably demonstrates resilience in this situated and temporal context.

3.3. Chapter 3: Incarceration (2000–2007)

The next time Natasha contacted Peggy, Krissy, and Gina, she was incarcerated in a men's prison in Brisbane. Under the influence of illicit substances and desperate for money to fund her gender‐affirming surgery, Natasha had resorted to robbery: over a 9‐day period in May and June 2000, she had armed herself with a syringe apparently filled with blood and had robbed, or attempted to rob, several small businesses in Brisbane. Natasha received a sentence of 8 years and would serve most of her sentence in two male prisons in Brisbane, Queensland.

At the time of her incarceration (2000–2007), the legislative and policy environment governing incarcerated trans women in Australia lacked specificity and particularization and there was no universally acknowledged policy designation to enshrine or enact trans‐specific rights. “Transgender offenders [were managed] on an as‐needed individual basis” (Queensland Department of Corrective Services, 2005, p.1). Trans incarcerated persons at the time of Natasha's incarceration were subject to and managed by two general instruments: the Corrective Services Act, 2000, which recognizes “(a) the need to respect an offender's dignity; and (b) the special needs of some offenders by taking into account… gender”; and the Anti‐Discrimination Act, 1991 (amended 2003) which makes it “unlawful to discriminate against a person on the basis of a person's gender identity.” 3

Natasha was thus incarcerated in a prison system that had no process or strategy for accommodating her, and this left her vulnerable to ignorance and insensitivity on the one hand, and victimization and abuse on the other. Trans women in male prisons experience extremely high rates of victimization, sexual assault, abuse, and indifference (Brömdal, Clark, et al., 2019; Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2016; Phillips et al., 2020; Sumner & Sexton, 2016; Van Hout et al., 2020; White Hughto et al., 2018) and Natasha was exposed to all these atrocities. She described her experience, in a letter to the Department of Corrections, as resulting in “ongoing humiliation and discrimination … having a severe impact on [my] emotional and psychological well‐being” (Natasha Keating, 12/20/2005).

However, despite these extremely negative and harmful experiences, Natasha was also able to advocate for herself while she was incarcerated. Natasha's actions during this period of incarceration represent the central psychological mystery addressed by this psychobiography (Schultz, 2005a).

Instead of accepting the circumstances in which she found herself, Natasha expressed that she would “no longer tolerate the narrow‐minded, petty, power trips” of the system (Natasha, letter to ATSAQ, 11/10/2005). She waged a continuous campaign throughout her time in incarceration against her positioning in the system as male by expressing, “to say that I am male and will be treated as such is … offensive” (Natasha Keating, letter to General Manager of Prisons, 25/10/2005). Her campaign took the form of multiple letters written to individuals in authority initially demanding access to various gender‐affirming items such as women's undergarments and running shoes, but later addressing broader issues, such as campaigning against the ways in which the carceral system managed her romantic relationship, making repeated requests for appropriate physical and mental health interventions, and detailing abuses that contravene her rights (Halliwell et al., 2022, 2023). She also corresponded frequently with ATSAQ, and this correspondence (see the description of the data in the method section) provides us with insight into the ways in which Natasha enacted her agency while incarcerated.

To provide an example of the way in which Natasha expressed resilience during these campaigns we discuss below a specific incident from her letters. This incident concerns a six‐month campaign relating to permission to purchase a pair of pink Nike running shoes. While this incident might seem “small” compared to the other injustices Natasha faced, such as having to battle to access hormone therapy, receive appropriate physical care or to not be separated from her romantic partner, we foreground it here for several reasons. Firstly, the running shoes themselves are a ‘small’ item but they represent, for Natasha, an important aspect of her positive self‐identity (Matsuno & Israel, 2018), as being able to access and wear gender‐affirming clothing is a mode of expressing an authentically gendered self (Coleman et al., 2012). Secondly, the strategies she used in this campaign are similar to the strategies she used in other campaigns and provide a clear example of the grit, determination, and persistence that characterize her advocacy. Finally, the campaign ends in a clear victory for Natasha when she is finally able to purchase the shoes; these clear victories were rare for Natasha, as most of the time she was fighting a continual battle against an unjust and mostly unyielding system.

The first mention of the pink running shoes appears in a letter Natasha wrote to the Prison Manager in October 2005 where she expressed her unhappiness with the denial of her request for women's running shoes. She writes “it is important to my Mental and Emotional well‐being to live as, and be treated as a woman …. This unreasonable refusal of a simple request was made without the proper insight into my situation and the overwhelming emotional upset this and many other decisions over the past five years has caused” (Natasha Keating, 21/10/2005, Letter to Prison Manager). Thus, even in this initial mention of the shoes, Natasha is explicitly linking the denial of this “simple request” to other, more serious denials. Indeed, Gina explained how Natasha linked her desire for running shoes to fighting for gender‐affirmation more generally: “those pink joggers 4 became an obsession, to the average person outside, no one would give a bugger, but that is like having gender reassignment, I want them pink joggers” (Gina, interview with Krissy and Gina). Viewed through a resilience lens, this “obsession” reflects Natasha's sense of self‐worth and her positive self‐defined identity (Matsuno & Israel, 2018), both important individual factors in the TRIM.

Six weeks after the initial denial of the request, Natasha again highlighted the unfairness of the situation, “this type of petty power play is humiliating [emphasis in original] and it is causing me ongoing stress and emotional grief, and is also, I believe discriminatory [sic] and being dealt with unprofessionally” (Natasha Keating, Letter to Prison Manager, 8/12/2005). Natasha also indicated her willingness to take the matter further: “… I am requesting an answer within 7 days or I will have no choice but to forward all correspondence to [name redacted] and the Anti‐Discrimination Commission” (Natasha Keating, Letter to Prison Manager, 8/12/2005). Natasha's statement about escalating her case shows both her ability to use the legal means available to her, but also an awareness of herself as being potentially part of a community, an awareness that is an important factor in resilience (Matsuno & Israel, 2018).

When Natasha's request for the shoes was finally approved (her request for other gender‐affirming items such as women's nighties/nightshirts was denied) several weeks later, Correctional Services attempted to explain the delay by stating that her “particular circumstances are complex” (Letter from Custodial Operations of Correctional Services, no date). Natasha responded: “I would like to know what is so complex about a pair of size 9 NIKE runners” (Natasha Keating, Letter to Executive Director of Custodial Operations, 02/20/2006), a response that speaks both to her humor and to her ability to highlight the petty but cumulatively destructive discrimination to which she was constantly subjected.

Even after permission was granted, it took several months for Natasha to be allowed to purchase her shoes, and she ultimately had to purchase a different pair as the original shoes were out of stock. Natasha eventually received her shoes on March 16, 2006 and expressed her delight at finally possessing the “… cutest, pinkest ‘bad girls’ around” (Natasha Keating, Letter to Director General of Correctional services). This was over 6 months after her initial request for running shoes.

That Natasha viewed this campaign for running shoes as a battle in a much larger war is very clear from her letters. For example, in a letter to ATSAQ dated January 30, 2006 she indicates: “The battle hasn't quite been won, and the war is really only beginning.” She also later indicates, in a letter to a discrimination lawyer, that she sees this fight for running shoes as just one step in a larger campaign: “I could take on the Department of Corrective Services for them to allow me to have surgery … Although with the battle I've had just trying to purchase a pair of women's runners … it would definitely be bigger than Ben Hur!” (Natasha Keating, Letter to Discrimination Lawyer, 2/2/2006).

In our previous analysis of Natasha's corpus of letters, we (Halliwell et al., 2022, 2023) analyzed the linguistic strategies used by Natasha in this and other campaigns. We identified a reliance on language related to conflict, assault, and trauma, and positioning her experiences as relating to a battle or fight between herself and the carceral system's bureaucracy. This language is evident in her “victory speech”, which was published in the ATSAQ newsletter in 2006:

Well here we go again boys and girls, the fight never ends! …. First were the bras, then the panties, and the battle for them was nowhere near the “BATTLE” I had for the size 9's but with a lot of help from my friends, we got them too! … and now we battle on, to get them to recognize that yes, I am a woman, hear me roar! I will not back down; I will not be stood over by anyone. (Natasha Keating; ATSAQ newsletter, 2006)

This vision of Natasha as a fighter was echoed in the interviews conducted with Peggy, Gina, and Krissy. In particular, these interviews allowed us to place this language and discursive strategy into the broader context of Natasha's life experience and to view it as part of an expression of her positive self‐identity (Matsuno & Israel, 2018) as a trans woman or, as Natasha described herself, “I am a[n] M‐F pre‐op Transgender woman incarcerated in a men's prison [and this does not give] anyone the right to treat me like I'm less of a human being” (Natasha, 13/02/2006). In particular, the interviews allowed us to see that those agentic actions taken by Natasha prior to incarceration, such as taking up sex work to provide for herself financially, laid the foundations for the resilience that she later displayed while incarcerated. Natasha had been fighting against unjust systems long before she was incarcerated; the carceral system now provided her with a clear set of rules for her fight.

Natasha's construction of her identity within the carceral system appears to have coalesced around this central image of herself as fighting a battle against an unjust and oppressive system. In this way, she was able to articulate what the TRIM would describe as a positive self‐defined identity (Matsuno & Israel, 2018). While some of the actual victories may appear small, such as the battle for the pink running shoes, they came to represent gender affirmation (Matsuno & Israel, 2018) and identity for Natasha. Considering that the carceral setting embodying societal conceptualizations of trans also expects a predictable iteration of trans woman and yet at the same time punishes trans women for not being men (Sanders et al., 2022), Natasha's demand for the pink running shoes is a fight for her trans subjectivity, further demonstrating resilience in this situated and temporal carceral context.

Other important resilience factors present during Natasha's time in incarceration relate to her interpersonal relationships and social support. She rebuilt her relationship with her mother, Peggy, and spoke to her frequently on the telephone. To this point, Krissy commented that “[her] mother always had her back” (interview with Gina and Krissy). In addition, Natasha's relationship with Krissy and Gina deepened during her incarceration. Gina served as a mentor to Natasha in terms of trans advocacy and can be viewed as a positive role model (Matsuno & Israel, 2018). Gina, herself a vociferous and experienced trans legal and human rights advocate, persuasive writer, and a past secretary of the Australian Railways Union advocating for social justice and change, encouraged Natasha: “I might have given [her] some urging. You know, but I didn't put the words in. She did it all herself, but I used to say to [her] … you've gotta write from your heart … I always used to say write how you feel” (Gina; interview with Krissy and Gina). Natasha clearly valued this relationship deeply and expressed this as follows in a letter to ATSAQ dated 8 May 2006: “I want to give you both a big hug for having helped me sooooooooo much in these battles and wars against the system, I really don't think I could have done it without all of your help.”

An additional important relationship during this time in Natasha's life was her romantic relationship with ‘Anton’, 5 a man with whom she had been incarcerated. This relationship lasted for a substantial portion of Natasha's carceral time; Natasha viewed Anton as her husband and believed that the relationship would endure after they had both served their sentences. Natasha's commitment to Anton is evident in her letters, where in response to an attempt to transfer Anton she declares herself “more than happy to take the fight on [because] he's my husband” (Natasha, 30/01/2006). Although Natasha trusted that the relationship would endure outside of prison, Peggy was less sure and warned her that “it was a prison thing … it's not going to come out to the outside world with you” (Interview with Peggy). In a companion paper (Halliwell et al., 2023), we explore in detail the protective process that Natasha used while incarcerated to enable the continuation of this relationship. However, a detailed exploration of these processes falls outside of the scope of this psychobiography.

Post incarceration, Anton and Natasha were in contact up until the day she ended her life. Due to a lack of information about his full name and whereabouts, he was unable to be interviewed for this research project. While this relationship with Anton was clearly an important part of Natasha's life during this chapter of her life, we, therefore, do not have additional information about Anton and his psychology, or on the nature of their relationship within the carceral system.

All of the supports described above can be viewed as indicative of group‐level resilience factors in the TRIM (Matsuno & Israel, 2018). Several of the other group‐level factors identified by the model can also be identified during this stage of Natasha's life. In particular, she was able to contribute toward trans carceral rights and health advocacy through her correspondence with ATSAQ, and the trans community, and served as a positive role model through her advocacy.

In understanding Natasha's advocacy during this time, it is also important to recognize the significance of the context in helping shape her advocacy and resilience. The carceral system within which she was confined subjected her to injustices and discrimination even while it outlined pathways and structures for complaint and advocacy. Reading through Natasha's letters in chronological order, one is struck by her increasing familiarity with the system in which she was placed and the regulative frameworks of institutional governance. Natasha's letters frequently allude to specific legal acts governing prison services, and she became an expert at mobilizing organizations outside of the prison system to assist with her requests. For example, in a letter dated December 7, 2005, she states that she has reached out to “the Anti‐Discrimination Commission of Queensland, The General Manager of [prison in which she was incarcerated], Prisoners [sic] Legal Service … and the ‘Custodial Directorate’ and the Department of Corrective Services.” In our previous work (Halliwell et al., 2022), we have argued that this familiarity is part of a discursive strategy through which she achieves mastery of the legal instruments of the carceral system in order to affirm her positive self‐identity within the system.

If resilience is viewed through the lens of performativity and situated in context (Aranda et al., 2012), it is possible to see how Natasha's embodied reality of living as a woman in a man's prison resulted in her interacting with systems of power in ways that would not have been possible in other contexts. For example, the carceral system's constant misgendering of Natasha (she is referred to as “he” throughout the official records) resulted in her seeking an official directive to be referred to as by her preferred pronoun of “she,” thus creating an official acknowledgment of her identity.

In concluding this chapter of Natasha's life, it is important to note that although it is instinctive to want to celebrate the victories Natasha achieved while incarcerated, we must not lose sight of the fact that she also experienced “years of cruel and unusual punishment” (Natasha Keating, letter to ATSAQ, 30/03/2006) characteristic of the experiences of trans incarcerated women (Brömdal, Clark, et al., 2019; Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2016; Phillips et al., 2020; Sumner & Sexton, 2016; Van Hout et al., 2020; White Hughto et al., 2018). More specifically, once incarcerated, trans women often experience what has been referred to as “double punishment” or being “doubly imprisoned,” suggesting that trans incarcerated persons are punished “first by the pervasive discrimination in the judicial system that continues to fail to give due legal recognition of transgender people's right to dignity and self‐identity, and second by the often ‘cruel and unusual’ mistreatment of them in the prison” (Erni, 2013, p. 139; Phillips et al., 2020, pp. 332–333). Natasha wrote that this “ongoing humiliation and discrimination … [has] a severe impact on my emotional and psychological well‐being” (Natasha Keating, Letter to Custodial Directorate 20/12/2005). The fact that she managed to advocate for herself in a “total institution” characterized by being “encompassing” and “totalistic” (Goffman, 1961, p. 4) evidence a strength of character, determination and ultimately resilience that allowed her to thrive. In the words of Peggy: “She'd done pretty well. Probably better than a lot of people would do under the circumstances because she was a tough little nut. That's what got her through” (Interview with Peggy).

3.4. Chapter 4: After incarceration (2007–2008)

Natasha was released from prison in 2007 (conditioned by a parole order) and almost immediately became involved again with illicit substances. The prison system had provided Natasha with some structure and had limited her access to substances but had not provided any psychological assistance in helping Natasha manage her addiction. Thus, once the structures of the system were removed, she was left to attempt to cope with unresolved trauma as well as social stigma relating to her status as a previously incarcerated person, and as a trans woman. In addition, her relationship with Anton started to break down and she came to realize that he was not willing to be in a romantic relationship with her outside of the prison setting. Gina and Krissy expressed their sadness at Natasha's powerlessness to overcome her drug addiction during this time (Gina: “you are married to drugs once you're on them”; Krissy: “and even the strongest people, like Natasha, at times fall down and become very weak and vulnerable, and she did, and she fell hard”).

On August 13, 2008, Natasha was staying with her mother and stepfather. After she went to bed, she lit a candle and took an overdose of prescription medication. Peggy found her lifeless in her room the following morning. A few days after her death, Gina received a letter that Natasha had mailed shortly before her passing. It contained a healing crystal and the words, “Gina, please look out for the girls, Tash.” The letter to Gina made it clear that Natasha had not overdosed unintentionally and had decided to end her life.

Natasha's suicide speaks to the temporal and situated nature of resilience. While Natasha's resilience was embodied within the carceral system by her fight against a domineering institution, once she was outside of that context different factors were at play in her life. When Natasha was released from incarceration, many of the group‐level factors that enabled her resilience and determination were removed. From the perspective of community belonging (Matsuno & Israel, 2018), she had lost the prison structures, the clear enemy, and her “fighter” identity, and instead, she was left to fend for herself in a lonely and isolating environment from which she had been absent for 7 years. In this environment, she again turned to illicit substances and prescription drugs and started to repeat old patterns. She also no longer felt provoked to act as an advocate and seemed to lose that aspect of her identity. Although her strong relationships with Peggy, Krissy, and Gina persisted, she lost the social and emotional support and affection of Anton, which was a severe setback to her dreams for the future. She also remained thwarted in her desire to undertake gender‐affirming surgery, and as such appears to have given up hope for the life she had imagined.

3.5. Natasha's legacy

Natasha's battle to address “the entirety and enormity of the negligence and [mis]treatment that women like myself are forced to endure” (Natasha Keating, 25/05/2006) has had ripple effects in the carceral system in Queensland. Gina explains:

Natasha wrote so well and was so comical that eventually people had to give in. The saga of the pink joggers—went public to the local newspaper. The governor of the prison and [their] deputy managers ended up coming for a meeting with ATSAQ two years later to “understand the situation”. So they could give [the governor] some insight into the life of transgenders and what they should do within the prison system to help them have a lifestyle without committing suicide or self‐harming …. Tash actually made them recognize that trans … is a … recognized condition … And she trailblazed. (Interview with Krissy and Gina)

According to Krissy, other tangible changes include the fact that preoperative trans women are now housed in single cells with shower facilities and housed with other trans women if possible (albeit still in male prisons). In addition, corrective service officers now undergo sensitivity training on trans empathy, identities, and how to ensure they meet the unique needs of incarcerated trans women, such as the use of correct name and pronoun, access to gender‐affirming supports and care (hormone therapy), and gender‐affirming items.

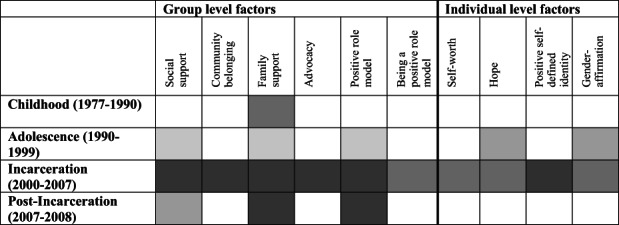

4. DISCUSSION

This psychobiography posed as its central mystery the question of what enabled Natasha's trans carceral rights and health advocacy work while she was incarcerated. Based on a thematic analysis of Natasha's life, we investigated her advocacy for personal and social change by focusing on her resilience, using the resilience factors identified within the TRIM to help shape the discussion. Based on this model, group‐level and individual‐level factors enabling Natasha's resilience were identified in each of the chapters in her life. The figure below provides a visual representation of the degree to which each identified level factor was present in Natasha's life. In the figure, the darkness of the shading indicates the extent to which a factor was present, with darker shading representing a greater presence.

Figure 2 below shows that the TRIM assists in providing an understanding of Natasha's advocacy while incarcerated. During Natasha's incarceration, more resilience‐promoting factors were present than at any other time in her life. On a group level, these included support from Peggy, Gina, Krissy, and Anton; a sense of belonging within the prison community, as well as within the trans community; the ability to act as a trans carceral rights and health advocate through her letter writing; the presence of a positive role model in the form of Gina; as well as the opportunity to be a positive role model for others, through her advocacy. On an individual level, the most prominent factor is her positive self‐defined identity, where her letter writing enabled her to articulate her identity as a trans fighter. She was also able, though her victories in relation to gender‐affirming items (e.g., bras, undergarments, pink Nike runners, and grooming and hygiene items), to experience a small measure of gender affirmation. Finally, within her corpus of letters, she expresses hope for the future as she believed that she would never stop fighting. All these individual factors suggest that she experienced a sense of self‐worth while she was incarcerated and viewed herself as someone who was worthy, and worth fighting for.

FIGURE 2.

Presence of resilience factors in Natasha Keating's life narrative

However, while the TRIM does help to categorize the resilience factors present within Natasha's life, there are aspects of Natasha's resilience that do not fit neatly within the model. Specifically, some of Natasha's individual characteristics, such as her sense of humor and her intelligence, which come across so strongly in her letters, are not neatly encapsulated in any of the individual‐level resilience factors within the model. There is no doubt that Natasha's intelligence played a core role in her advocacy as she was able to learn the intricacies of the carceral system and astutely use the rules of that system to help her in her fight against the injustices she faced. The intricacies of this process are explored in more detail in our CDA papers focusing on Natasha's advocacy (Halliwell et al., 2022, 2023).

In addition, while the analysis highlights the presence of individual and group factors, it is not possible to identify the relationship between them or how they developed. For example, we know that Natasha's action of reaching out to Krissy and Gina while incarcerated was vital to establishing many of the group‐level factors that promoted her resilience. Given that there is a strong link between group‐level resilience factors and individual‐level resilience factors (Matsuno & Israel, 2018), it is likely that Natasha already possessed levels of resilience prior to her incarceration, and it is this resilience that drove her to reconnect with Gina and Krissy, and through so doing started the process that enabled the development of multiple group‐level resilience factors. How she came to possess this prior resilience is unknown; however, it seems likely that she experienced some level of group belonging in the adolescent period. In addition, from a post‐traumatic growth perspective (Tedeschi et al., 2018), it is possible that the trauma Natasha experienced led to psychological growth and her ability to survive through this tumultuous period and sowed the seeds for her later advocacy while incarcerated.

Secondly, although the TRIM does incorporate group‐level factors, it does not allow for an exploration of the way in which an individual such as Natasha is both restricted and enabled by their specific context. Thus, Natasha's relationship with the carceral system and the way in which the mechanics of that system provided the context for her resilience and advocacy falls outside of the scope of the TRIM and thus could not be fully explored in this paper.

However, one of the strengths of the analysis presented here is that the focus on the TRIM's group‐level resilience factors as a core component of Natasha's trans carceral rights and health advocacy has implications for how we understand the work of social change agents such as Natasha. A substantial body of research suggests that advocacy is particularly complicated for individuals who have multiple minority statuses (Hagan et al., 2018) and that trans women are often excluded from female‐only activist/advocacy spaces (Hagan et al., 2018). For Natasha, the group‐level resilience factors appear to have been core enablers for her advocacy and this suggests that establishing support and community is an important component of advocacy for individuals in minority marginalized and disenfranchised groups.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this study represents an unusual use of the method of psychobiography, which is usually used to analyze the lives of public and famous individuals for whom there is an abundance of publicly available data (du Plessis, 2017). Using this method to examine the life of a “lay” social change agent allowed us to apply a systematic method to what is essentially a case study approach (Yin, 2009), and further allowed for the explicit connection between life history and psychological theory.

This study is limited by its decision to make use of a single psychological theory (the TRIM) to explore Natasha's resilience. Although other resilience theories have been included where possible (e.g., Hillier et al., 2020), the analysis is primarily based on the factors within the TRIM. It is possible that incorporating different models of resilience might have assisted in expanding the results, but this was not possible due to space constraints within this paper. However, other aspects of Natasha's advocacy are explored in more detail in Halliwell et al. (2022) and Halliwell et al. (2023).

An additional limitation of this study relates to the absence of additional information about Natasha, specifically in relation to the adolescent chapter in her life as well as to her drug use. There are significant gaps in our knowledge of what happened to Natasha at various points in her life, and we are thus only able to speculate on the impact certain episodes might have had on her later resilience, determination, and trans carceral rights and health advocacy. Finally, our trans rights and health academic advocacy positionality with lived experiences of incarceration could be viewed as both a strength and a weakness in how the authors interpreted the corpus of letters linked to Natasha's life while incarcerated, as well as the interview data provided by Peggy, Gina, and Krissy about Natasha's life story within and outside the prison walls.

5. CONCLUSION

This psychobiography of Natasha Keating investigated the mystery of her trans carceral rights and health advocacy while serving her time in two male carceral settings in Queensland, Australia. We identified her resilience and resilience‐promoting factors as core components supporting her advocacy. In the words of Gina, although “life gave her a bloody raw deal” (Interview with Gina and Krissy), Natasha's legacy is one of courage and strength that serves as a reminder of the difference that one individual fighting for recognition can make within a system, for self and others.

6. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Carol du Plessis, Sherree D. Halliwell, Amy B. Mullens and Annette Brömdal. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Carol du Plessis and all authors commented on all versions of the manuscript, including versions incorporating revisions suggested by the anonymous reviewers. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the Centre for Health, Informatics, and Economic Research Internal Funding Bid (2019) at the University of Southern Queensland with the last author as the lead investigator. This work was also supported by the University of Southern Queensland through an Internal Research Capacity Grant with the last author as the lead investigator [Project ID 1007573, 2020].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ETHICS APPROVAL

This study was granted ethical approval by the Human Ethics Committee of the University of Southern Queensland [H19REA236].

PRE‐REGISTRATION

This study was pre‐registered in OFS in May 2021. The data collection and analysis strategies are as described in the pre‐registration; however, the psychology theory used is different to that proposed in the pre‐registration.

7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First, we wish to express our heartfelt and sincere gratitude to Peggy Keating, Natasha’s mother, and Gina Mather (President) and Kristine Johnson (Secretary) of the Australian Transgender Support Association of Queensland Inc. (ATSAQ) who shared their experiences of Natasha’s advocacy and social change work regarding trans persons in incarceration with our research team. Without their stories, this paper would not have been possible. The authors also wish to thank the anonymous reviewers who provided insightful, affirming and detailed feedback on earlier revisions of the manuscript. Finally, we are grateful for the support of the editorial team who helped to guide this manuscript through the publication process. Open access publishing facilitated by University of Southern Queensland, as part of the Wiley ‐ University of Southern Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

du Plessis, C. , Halliwell, S. D. , Mullens, A. B. , Sanders, T. , Gildersleeve, J. , Phillips, T. , & Brömdal, A. (2023). A trans agent of social change in incarceration: A psychobiographical study of Natasha Keating. Journal of Personality, 91, 50–67. 10.1111/jopy.12745

Endnotes

Referring to Natasha's behavior and/or temperament.

It is not known when Natasha started her hormone therapy, or which doctors prescribed the treatment.

Prior to 2003, “unlawful” discrimination “on the basis of a person's gender identity” did not interpret “gender identity” to include trans persons—regardless of if they had affirmed gender surgically/legally. The 2003 amendment to the Anti‐Discrimination Act, 1991 interprets “gender identity” to include trans persons; however, trans persons are not literally specified or articulated in the Act's interpretation of “gender identity” (ATSAQ personal communication, 2021).

‘Joggers’ is an Australian slang term referring to trainers, sneakers, and running shoes.

A pseudonym has been used as this individual has not given permission to be identified.

REFERENCES

- Alexander, I. E. (1990). Personology: Method and content in personality assessment. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Author. [Google Scholar]

- Anti‐Discrimination Act 1991. (Qld) s. 15 (Austl.).

- Aranda, K. , Zeeman, L. , Scholes, J. , & Morales, A.,. S.‐M. (2012). The resilient subject: Exploring subjectivity, identity and the body in narratives of resilience. Health, 16(5), 548–563. 10.1177/1363459312438564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal, A. , Clark, K. A. , Hughto, J. M. W. , Debattista, J. , Phillips, T. M. , Mullens, A. B. , Gow, J. , & Daken, K. (2019). Whole‐incarceration‐setting approaches to supporting and upholding the rights and health of incarcerated transgender people. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(4), 341–350. 10.1080/15532739.2019.1651684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal, A. , Halliwell, S. , Sanders, T. , Clark, K. , Gildersleeve, J. , Mullens, A. B. , Phillips, T. , Debattista, J. , du Plessis, C. , Daken, K. , & Hughto, J. M. W. (2022). Navigating intimate trans citizenship while incarcerated in Australia and the US. Feminism & Psychology, 1–23. 10.1177/09593535221102224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal, A. , Mullens, A. B. , Phillips, T. M. , & Gow, J. (2019). Experiences of transgender prisoners and their knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding sexual behaviors and HIV/STIs: A systematic review. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(1), 4–20. 10.1080/15532739.2018.1538838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. R. (2014). Qualitative analysis of transgender Inmates' correspondence. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 20(4), 334–342. 10.1177/1078345814541533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushkin, H. , van Niekerk, R. , & Stroud, L. (2021). Searching for meaning in chaos: Viktor Frankl's story. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 17(3), 233–242. 10/5964/ejop.5439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E. , Bockting, W. , Botzer, M. , Cohen‐Kettenis, P. , DeCuypere, G. , Feldman, J. , Fraser, L. , Green, J. , Knudson, G. , Meyer, W. J. , Monstrey, S. , Adler, R. K. , Brown, G. R. , Devor, A. H. , Ehrbar, R. , Ettner, R. , Eyler, E. , Garofalo, R. , Karasic, D. H. , … Zucker, K. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender‐nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. [Google Scholar]

- Corrective Service Act 2000. (Qld) (Austl.).

- de Jesus, D. S. V. (2021). The rebel madame: Madonna's postmodern evolution. Journal of Literature and Art Studies, 11(1), 26–32. 10.17265/2159-5836/2021.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis, C. (2017). The method of psychobiography: Presenting a step‐wise approach. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 14(2), 216–237. 10.1080/14780887.2017.1284290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erni, J. N. (2013). Legitimating transphobia: The legal disavowal of transgender rights in prison. Cultural Studies, 27(1), 136–159. 10.1080/09502386.2012.722305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus, S. , & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks, N. , Mullens, A. B. , Aitken, S. , & Brömdal, A. (2022). Fostering gender‐IQ: Barriers and enablers to gender‐affirming behavior amongst an australian general practitioner cohort. Journal of Homosexuality, 1–24. 10.1080/00918369.2022.2092804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glezer, A. , McNiel, D. E. , & Binder, R. L. (2013). Transgendered and incarcerated: A review of the literature, current policies and laws, and ethics. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 41(4), 551–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental health patients and other inmates. Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J. M. , Mottet, L. A. , Tanis, L. A. , Harrison, J. , Herman, J. L. , & Keisling, M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, W. B. , Hoover, S. M. , & Morrow, S. L. (2018). A grounded theory of sexual minority women and transgender individuals' social justice activism. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(7), 833–859. 10.1080/00918369.2017.1364562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, S. , du Plessis, C. , Hickey, A. , Gildersleeve, J. , Mullens, A. B. , Sanders, T. , Clark, K. , Hughto, J. M. W. , Debattista, J. , Phillips, T. , Daken, K. , & Brömdal, A. (2022). A critical discourse analysis of an Australian incarcerated trans woman's letters of complaint and self‐advocacy. Ethos, 1–25. 10.1111/etho.12343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, S. , Hickey, A. , du Plessis, C. , Mullens, A. B. , Sanders, T. , Gildersleeve, J. , Phillips, T. , Debattista, J. , Clark, K. , Hughto, J. M. W. , Daken, K. , & Brömdal, A. (2023). “Never let anyone say that a good fight for the fight for good wasn't a good fight indeed”: The enactment of agency through military metaphor by one Australian incarcerated trans woman. In Panter H. & Dwyer A. (Eds.), Transgender identities and criminal justice: An examination of issues in victimology, policing, sentencing, and prisons. Palgrave Macmillan; Accepted for Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Harisunker, N. , & du Plessis, C. (2021). A journey towards meaning: An existential psychobiography of Maya Angelou. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 17(3), 210–220. 10.5964/ejop/5491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]