Abstract

Background

The aim of this systematic review was to examine the classification of calls for suicidal behavior in emergency medical services (EMS).

Methods

A search strategy was carried out in four electronic databases on calls for suicidal behavior in EMS published between 2010 and 2020 in Spanish and English. The outcome variables analyzed were the moment of call classification, the professional assigning the classification, the type of classification, and the suicide codes.

Results

Twenty-five studies were included in the systematic review. The EMS classified the calls at two moments during the service process. In 28% of the studies, classification was performed during the emergency telephone call and in 36% when the professional attended the patient at the scene. The calls were classified by physicians in 40% of the studies and by the telephone operator answering the call in 32% of the studies. In 52% of the studies, classifications were used to categorize the calls, while in 48%, this information was not provided. Eighteen studies (72%) described codes used to classify suicidal behavior calls: a) codes for suicidal behavior and self-injury, and b) codes related to intoxication, poisoning or drug abuse, psychiatric problems, or other methods of harm.

Conclusion

Despite the existence of international disease classifications and standardized suicide identification systems and codes in EMS, there is no consensus on their use, making it difficult to correctly identify calls for suicidal behavior.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12245-023-00504-1.

Keywords: Suicide, Emergency medical services, Classification, Call centers, Systematic review

Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), suicide has emerged as one of the greatest public health problems worldwide, second only to traffic accidents as a cause of death in the population aged 15 to 29 years [1, 2].

Studies show that suicide attempts are the most important risk factor in the prediction of suicidal behavior [3]. Individuals with a previous history of self-harm are 25 times more likely to die by suicide than those who do not, and it is estimated that there are 20 previous attempts for every death by suicide [2–4].

Early diagnosis and treatment of these behaviors, as well as the adoption of appropriate measures to prevent the progression from suicidal ideation to death by suicide is one of the most effective preventive measures [4]. Accordingly, if the attention given to individuals who attempt suicide is swift, immediate, and appropriate, the number of suicides may be reduced. The risk of suicide can also be decreased with a suitable prevention and treatment program implemented by professionals in the prehospital and hospital setting [1, 5].

Studies show that contact between the population with suicidal behavior and health services is not sufficient to identify or prevent this health problem. Only 33% of people who die by suicide were hospitalized in the preceding year, which suggests that a high percentage of people received no medical or psychological help [6, 7]. Moreover, some people with suicide attempts only have contact with medical services through the emergency department [8–10].

EMS are among the first medical units to attend to people who have experienced severe events such as suicide attempts and are responsible for transferring patients to the emergency department [11–13]. The response of EMS to calls for suicidal behavior is crucial in order to improve medical care for this population [14]. Thus, proper identification and classification of calls can ensure that the individual is given access to psychiatric and psychological treatment to prevent future attempts with a fatal outcome [6, 15].

Since the detection of suicide attempts and related behaviors is necessary to prevent deaths, more studies are needed, especially in prehospital emergency services [16, 17]. With regard to suicidal behavior, its identification, diagnosis, and accurate recording are essential to provide a complete overview of the suicidal behavior. However, there is a lack of information on how suicidal behavior is recorded in the prehospital emergency setting. The aim of this systematic review was therefore to determine which classifications and codes are used in EMS to identify and record suicidal behavior, which professional assigns them, and when they are assigned during the process of attending an emergency call.

Methods

Study design

We performed a systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement [18]. The protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42021227036).

Search strategy

Two psychologist co-authors of this study (MAC and JR) independently conducted literature searches through PsycINFO, Pubmed, Scopus and Science Direct databases during the period September–October 2020. The search string was: (“emergency medical services” OR “emergency healthcare” OR “prehospital emergency” OR “911 calls”) AND “suicid*” in the title, abstract and keyword sections.

The following inclusion criteria were applied: a) empirical studies on suicidal behavior in emergency medical services (EMS); b) studies in Spanish or English; c) studies published between January 1, 2010 and October 31, 2020.

Study selection

First, the two researchers reviewed the title and abstract of all the studies found through the literature searches to determine which met the inclusion criteria. After identifying potentially eligible studies, the full text of each study was reviewed. All studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The final decision concerning the included studies was made by discussion between the two authors and any disagreement was resolved by the third co-author of the study (BMK).

Data extraction and variables

The variables collected from the different studies are detailed below and in Table 1.

Characteristics of the study variables: country, geographic study area, population, data collection period, sources of extraction of the calls, total number of calls, number of suicidal behavior calls, and quality of studies.

Outcome variables: moment of call classification, professional who assigned the suicide classification, and classification system and suicide codes used. Prehospital calls were recorded from information received by telephone at the emergency coordinating centers. First, the telephone operator or physician answering the call asked questions following a protocol established for each type of call, determined the priority level based on a triage system according to severity [19, 20], and assigned a classification code. Next, the professional who attended the patient on site classified the same call.

Table 1.

Description of the variables collected from the studies

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDIES | |

| Country | Country in which the study was conducted |

| Geographic study area | Name of the geographic study area |

| Population | Number of inhabitants of the geographic study area |

| Data collection period | Time period in which data collection was performed |

| Sources of extraction of the calls | Databases from which the calls were extracted |

| Total number of calls | Sample of calls used in the study (N) |

| Number of suicidal behavior calls | Suicidal behavior calls extracted from total calls (N/%) |

| Quality of study | Indicates the quality range of the study through the Manual for Quality Scoring of Qualitative Studies expressed as a percentage |

| OUTCOME VARIABLES | |

| Moment of call classification | Point in time when codes are assigned to a call |

| Professional who classifies the calls | Person who classifies a call as suicidal behavior |

| Type of classification | Classification system used to categorize the calls |

| Suicide codes | Codes to classify calls as suicidal behavior, according to the classification used |

Included studies were independently assessed for quality by two reviewers using the Manual for Quality Scoring of Qualitative Studies [21] (Table S1). Following Scott et al. (2014a), scores were transformed into percentages for a better understanding of quality. Accordingly, the minimum score corresponds to 0% and the maximum to 100%, with higher scores representing higher quality. Final quality scores are reported as the combination of the scores of each reviewer.

Results

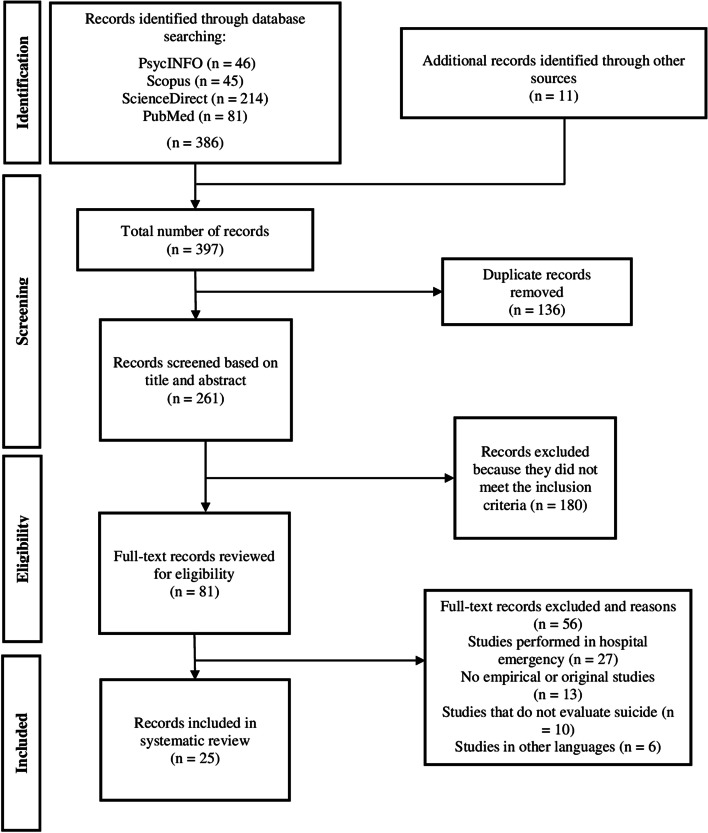

The search of electronic databases generated 386 results, and 11 studies were identified after manual bibliography searching. Thus, we found a total of 397 records. We excluded 136 duplicate articles, leaving 261 to be reviewed by title and abstract. Of these, 180 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The full text of the 81 remaining articles was reviewed, and 56 were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. Finally, a total of 25 publications were selected and included in the systematic review [10, 11, 19, 20, 22–42] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study selection for systematic review

Characteristics of the studies

The studies were conducted in various countries: Eight in Spain [10, 11, 20, 22, 25, 26, 31, 40]; three in the United Kingdom (UK) [28, 33, 41]; two in the United States of America (USA) [23, 29], Australia [19, 27], Brazil [24, 42], and Turkey [34, 35]; and one in Switzerland [30], Norway [32], Korea [36], Russia [37], France [38], and Japan [39]. According to the data collection period, two studies collected data for less than one year [33, 38] and fourteen for one year [11, 19, 20, 23–25, 28, 29, 31, 32, 34, 37, 41, 42]. Another study gathered data for two years [40], three for three years [35, 36, 39], one for six years [27], two for seven years [10, 22], and another two for ten years [26, 30]. According to the sources of extraction of the calls, thirteen studies used an EMS Coordination Center database [10, 11, 20, 22, 23, 25, 26, 31, 33–35, 39, 40], four used a hospital database [27, 28, 32, 38], and eight used ambulance records [19, 24, 29, 30, 36, 37, 41, 42]. Regarding the number of suicide calls, we observed great variability in the total number of calls selected by the studies, ranging from 779 to 6 million. With regard to the quality of the studies used in the systematic review, the quality was 90% in five studies, 80–85% in eight, 75–77.5% in nine, and less than 70% in the remaining three. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies

| ID-Article | First author (year-publication) | Country | Geographic study area (population) | Data collection period (month, year) | Sources of extraction of the calls |

Total calls N |

Suicidal behavior calls N (%) | Quality of studya (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Mejías-Martín Y. (2018) [10] | Spain | Andalusia (8,464,411) | 2007 – 2013 | Coordination Center database | 6,608,031 | 20,942 (0.31%) | 90 |

| 11 | Pacheco A. (2010) [11] | Spain | Spain (47,329,000) | 2008 | Coordination Center database | 711,228 | 2.645 (0.4%) | 52,5 |

| 19 | Roggenkamp R. (2018) [19] | Australia | Victoria (6,695,000) | 2015 | Ambulance records | 504,676 | 18,976 (3.7%) | 82,5 |

| 20 | Guzmán-Parra J. (2016) [20] | Spain | Malaga (1,528,851) | 2008 | Coordination Center database | 163,331 | 1,171 (0.7%) | 90 |

| 22 | Mejías-Martín Y. (2019) [22] | Spain | Andalusia (8,464,411) | 2007 – 2013 | Coordination Center database | 6,608,031 | 25,456 (0.4%) | 90 |

| 23 | Creed JO. (2018) [23] | United States | Wake County (1,112,000) | August 2013 – July 2014 | Coordination Center database | 1,555 | 101 (6.5%) | 85 |

| 24 | Ferreira TD. (2019) [24] | Brazil | Ribeirão Preto (674,405) | 2014 | Ambulance records | 48,168 | 313 (0.6%) | 77,5 |

| 25 | Moreno-Küstner B. (2019) [25] | Spain | Malaga (1,528,851) | 2014 | Coordination Center database | 181,824 | 1.728 (0.9%) | 90 |

| 26 | Celada FJ. (2018) [26] | Spain | Castilla La Mancha (2,035,505) | 2006–2015 | Coordination Center database | Not specified | 1,308 | 77,5 |

| 27 | Crossin R. (2018) [27] | Australia | Victoria (6,695,000) | January 2012 – June 2017 | Hospital database | 779 | 236 (30.3%) | 77,5 |

| 28 | Duncan EA. (2019) [28] | United Kingdom | Scotland (5,463,300) | 2011 | Hospital database | 500,000 | 4,699 (0,9%) | 85 |

| 29 | Gratton M. (2010) [29] | United States | Kansas City (470,000) | 2006 | Ambulance records | 72,668 | 734 (1%) | 82,5 |

| 30 | Holzer BM. (2012) [30] | Switzerland | Zurich (400,000) | May & June from 2001 through 2010 | Ambulance records | 4,239 | 135 (3.2%) | 80 |

| 31 | Jiménez-Hernández M. (2017) [31] | Spain | Malaga (1,528,851) | 2008 | Coordination Center database | 163,331 | 1,380 (0.8%) | 90 |

| 32 | Johansen IH. (2010) [32] | Norway | Norway (5,367,580) | 2006 | Hospital database | 5,672 | 8 (0.2%) | 62,5 |

| 33 | John A. (2016) [33] | United Kingdom | Wales (3,153,000) | December 2007 – February 2008 | Coordination Center database | 92,331 | 175 (0.2%) | 85 |

| 34 | Kayipmaz S. (2020a) [34] | Turkey | Turkey (83,154,997) | September 2018 – August 2019 | Coordination Center database | Not specified | 769 | 77,5 |

| 35 | Kayipmaz S. (2020b) [35] | Turkey | Ankara (5,639,076) | January 2017 – June 2019 | Coordination Center database | Not specified | 6,777 | 77,5 |

| 36 | Kim SJ. (2015) [36] | Korea | Korea (48,000,000) | 2008 – 2010 | Ambulance records | 64,155 | 5,743 (8.9%) | 67,5 |

| 37 | Krayeva YV. (2013) [37] | Russia | Yekaterinburg (1,501,000) | March 2, 2009 – March 1, 2010 | Ambulance records | 2,536 | 984 (38.8%) | 85 |

| 38 | Maignan M. (2019) [38] | France | France (62,979,000) | March 17 / 18, 2015 | Hospital database | Not specified | 703 | 77,5 |

| 39 | Matsuyama T. (2016) [39] | Japan | Osaka (2,669,000) | 2010 – 2012 | Coordination Center database | 633,359 | 9,424 (1.5%) | 82,5 |

| 40 | Mejías-Martín Y. (2011) [40] | Spain | Granada (912,075) | 2008 – 2009 | Coordination Center database | 149,570 | 535 (0.4%) | 75 |

| 41 | Scott J. (2014)[41] | United Kingdom | Yorkshire (5,234,700) | April 2010 – March 2011 | Ambulance records | 5,818 | 459 (7.9%) | 77,5 |

| 42 | Veloso C. (2018) [42] | Brazil | Teresina (893,246) | 2014 | Ambulance records | 38,317 | 82 (0.2%) | 77,5 |

aRange of available quality score was 0% to 100%. Final quality score reported as the combination of each reviewer’s scores

Outcome variables

Moment of call classification

Seven studies (28%) classified the calls during the telephone call [20, 23, 29, 31, 38, 40, 41]; nine studies (36%) when the professional attended the patient at the scene [11, 24, 26–28, 30, 33, 37, 39], and five studies (20%) in both instances [10, 19, 22, 25, 32]. Four studies did not indicate when the call was classified (16%) [34–36, 42] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcome variables

| ID-Article | First author (year-publication) | Moment of call classification | Professional who classifies the calls | Type of classification | Suicide codes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Mejías-Martín Y. (2018) [10] |

Answering the call Attending at the scene |

Operator Physician |

ICD-9 ICD-10 |

300.9 (Unspecified non-psychotic mental disorder (Suicidal Tendencies)) 305 [305.4, 305.8] (Nondependent abuse of drugs) 969 [96.9.0, .1, .2, .3, .4, .5, .8, .9] (Poisoning by psychotropic agents) E950-E959 (Suicide and self-inflicted injury) E980-E989 (Injury undetermined whether accidentally or purposely inflicted) V62.84 (Suicidal ideations) X84 (Intentional self-harm by unspecified means) |

| 11 | Pacheco A. (2010) [11] | Attending at the scene | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| 19 | Roggenkamp R. (2018) [19] |

Answering the call Attending at the scene |

Nurses/Paramedics | MPDS | Not specified |

| 20 | Guzmán-Parra J. (2016) [20] | Answering the call | Operator | UECC Classification | Suicidal behavior: Self-injury and suicidal tendency, suicidal thoughts, suicide threat and suicide |

| 22 | Mejías-Martín Y. (2019) [22] |

Answering the call Attending at the scene |

Operator Physician |

ICD-9 ICD-10 |

305 [305.4, 305.8] (Nondependent abuse of drugs) 969 (Poisoning by psychotropic agents) E950-E959 (Suicide and self-inflicted injury) E980-E989 (Injury undetermined whether accidentally or purposely inflicted) X84 (Intentional self-harm by unspecified means) |

| 23 | Creed JO. (2018) [23] | Answering the call | Operator | MPDS | Code 25 (psychiatric/suicide attempt) |

| 24 | Ferreira TD. (2019) [24] | Attending at the scene | Nurses | Not specified | Fatal or non-fatal suicidal behavior |

| 25 | Moreno-Küstner B. (2019) [25] |

Answering the call Attending at the scene |

Operator Physician |

UECC Classification ICD-9 |

Suicidal behavior: Self-injury and suicidal tendency, suicidal thoughts, suicide threat and suicide E950-E959 (Suicide and self-inflicted injury) V62.84 (Suicidal ideations) |

| 26 | Celada FJ. (2018) [26] | Attending at the scene | Physician | ICD-9 |

E850-E858 (Accidental poisoning by drugs, medicinal substances, and biologicals) E860-E869 (Accidental poisoning by other solid and liquid substances, gases, and vapors) E950-E957 (Suicide and self-inflicted injury) |

| 27 | Crossin R. (2018) [27] | Attending at the scene | Paramedics | Not specified | Not specified |

| 28 | Duncan EA. (2019) [28] | Attending at the scene | Physician | AMPDS |

09E03 (Hanging) 17D02J (Falls, Long fall (= > 6gy/2 m) – Jumper) 17D03J (Falls, unconscious or not alert – Jumper) 23 (Intentional poisoning) 25B01 (Psychiatric, serious hemorrhage) 25B02 (Psychiatric, minor hemorrhage) 25B03 (Psychiatric, suicide (threatening)) 25B04 (Psychiatric, jumper (threatening)) 25D01 (Psychiatric, not alert) |

| 29 | Gratton M. (2010) [29] | Answering the call | Operator | MPDS | Code 25 (psychiatric/suicide attempt) |

| 30 | Holzer BM. (2012) [30] | Attending at the scene | Paramedics | Not specified | Intoxication related to a suicide attempt |

| 31 | Jiménez-Hernández M. (2017) [31] | Answering the call | Operator | UECC Classification | Suicidal behavior: Self-injury and suicidal tendency, suicidal thoughts, suicide threat and suicide |

| 32 | Johansen IH. (2010) [32] |

Answering the call Attending at the scene |

Physician | ICPC-2 | P77 (Suicidal behavior) |

| 33 | John A. (2016) [33] | Attending at the scene | Physician | Not specified | Suicidal ideation or intent |

| 34 | Kayipmaz S. (2020a) [34] | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| 35 | Kayipmaz S. (2020b) [35] | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| 36 | Kim SJ. (2015) [36] | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| 37 | Krayeva YV. (2013) [37] | Attending at the scene | Physician | Not specified |

Circumstances of poisoning as: 2. Suicidal attempts |

| 38 | Maignan M. (2019) [38] | Answering the call | Physician | Not specified | Deliberation Self-Poisoning (DSP) |

| 39 | Matsuyama T. (2016) [39] | Attending at the scene | Physician | Not specified |

Type of self-inflicted injuries: 1. Poisoning sleeping pill or tranquilizer 2. Poisoning by CO 3. Poisoning by other gas 4. Cutting and/or piercing wrist or arm 5. Cutting and/or piercing other part 6. Hanging 7. Jumping 8. Drowning |

| 40 | Mejías-Martín Y. (2011) [40] | Answering the call | Operator | ICD-10 | X84 (Intentional self-harm by unspecified means) |

| 41 | Scott J. (2014) [41] | Answering the call | Not specified | AMPDS | Psychiatric/abnormal behavior/suicide attempt |

| 42 | Veloso C. (2018) [42] | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

AMPDS Advanced Medical Priority Dispatch System, ICD-9 International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, ICD-10 International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, ICP-2 International Classification of Primary Care, 2nd edition, MPDS Medical Priority Dispatch System, UECC Urgencies and Emergencies Coordination Center

Professional who classifies the calls

Suicide codes were assigned by the following professionals: physicians in ten studies (40%) [10, 22, 25, 26, 28, 32, 33, 37–39], telephone operators in eight studies (32%) [10, 20, 22, 23, 25, 29, 31, 40], paramedics in three studies (12%) [19, 27, 30], and nurses in two studies (8%) [19, 24]. Four studies [10, 19, 22, 25] included calls in more than one professional category due to the classification being carried out by more than one professional. The six remaining studies [11, 34–36, 41, 42] did not specify who was responsible for assigning the codes (Table 3).

Regarding the moment at which the call was classified and the professional involved, as expected, all telephone operators classified the call during the telephone call [10, 20, 22, 23, 25, 29, 31, 40], while paramedics [27, 30] and nurses [24] did this when they attended the patient on site. In one of the studies [19], the calls were classified both during the call and when attending the incident at the scene, so more than one professional category was included. Concerning physicians, in two studies [32, 38] they classified the calls during the call, and in nine studies when attending the call on site [10, 22, 25, 26, 28, 32, 33, 37, 39] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Moment of call classification, professional involved, and classification used

| Moment of call classification | Article ID | Professional who classifies the calls | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| During the telephone call | 10 | Operator | ICD-9 |

| 19 | Paramedics/Nurses | MPDS | |

| 20 | Operator | UECC | |

| 22 | Operator | ICD-9 | |

| 23 | Operator | MPDS | |

| 25 | Operator | UECC | |

| 29 | Operator | MPDS | |

| 31 | Operator | UECC | |

| 32 | Physician | ICPC-2 | |

| 38 | Physician | Not specified | |

| 40 | Operator | ICD-10 | |

| 41 | Not specified | AMPDS | |

| Attending at the scene | 10 | Physician | ICD-10 |

| 11 | Not specified | Not specified | |

| 19 | Paramedics/Nurses | MPDS | |

| 22 | Physician | ICD-10 | |

| 24 | Nurses | Not specified | |

| 25 | Physician | ICD-9 | |

| 26 | Physician | ICD-9 | |

| 27 | Paramedics | Not specified | |

| 28 | Physician | AMPDS | |

| 30 | Paramedics | Not specified | |

| 32 | Physician | ICPC-2 | |

| 33 | Physician | Not specified | |

| 37 | Physician | Not specified | |

| 39 | Physician | Not specified |

AMPDS Advanced Medical Priority Dispatch System, ICD-9 International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, ICD-10 International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, ICP-2 International Classification of Primary Care, 2nd edition, MPDS Medical Priority Dispatch System, UECC Urgencies and Emergencies Coordination Center

Classifications used

In twelve studies the classification systems used to categorize suicidal behavior calls were not specified (48%) [11, 24, 27, 30, 33–39, 42], while in thirteen studies they were indicated (52%) [10, 19, 20, 22, 23, 25, 26, 28, 29, 31, 32, 40, 41]. Four of these thirteen studies (16%) used the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) [10, 22, 26, 40]. One study used the ninth revision (ICD-9) [26], another used the tenth revision (ICD-10) [40], and two used both [10, 22]: the ninth revision when answering the telephone call and the tenth revision when attending the patient at the scene. Five studies (20%) used a computerized system based on protocols, the Medical Priority Dispatch System (MPDS) [19, 23, 24] and its Advanced version (AMPDS) [28, 41]. The other two studies (8%) used a classification developed by the Urgencies and Emergencies Coordination Center of Andalusia (Spain) (UECC) [20, 31], and one study (4%) used the International Classification of Primary Care-2 (ICPC-2) [32]. One study (4%) used both the UECC classification, when responding to the telephone call, and the ICD-9 classification, when attending the patient on site [25].

When analyzing the classification and country of the study, we observed that the ICD and the UECC classifications were used in Spain, the MPDS in the USA and Australia, the AMPDS in the UK, and the ICPC-2 in Norway (Table 3).

In relation to the moment of call classification and the classification used, the ICD-9 was used in two studies during the emergency telephone call [10, 22] and in another two studies when attending the patient at the scene [25, 26]. The ICD-10 was used in one study during the telephone call [40] and in two studies when attending the emergency on site [10, 22]. The UECC Classification was used in three studies during the call [20, 25, 31], and the MPDS was used in three studies at this same point in time [19, 23, 29]. The MDPS was also used in one study when attending at the scene [19]. The AMPDS was used in one study during the emergency call [41] and in another when attending the patient at the scene [28]. Finally, in one study the ICPC-2 was used for assigning codes both during the call and at the scene [32] (Table 4).

Codes used to classify suicidal behavior calls

In eighteen studies (72%), codes used to classify the calls were indicated [10, 20, 22–26, 28–33, 37–41], while in the remaining seven studies (28%) this information was not provided [11, 19, 27, 34–36, 42].

To present the results, we grouped the codes into two broad categories: (1) those that explicitly specified suicidal behavior and (2) those that referred to poisoning, psychiatric problems, etc. and that are also often used to classify suicidal behaviors.

Specific suicidal behavior and self-injury codes were used in ten studies [10, 20, 22, 24, 25, 28, 31–33, 40], while codes for intoxication, poisoning, or drug abuse were used in eight studies [10, 22, 26, 28, 30, 37–39]. Codes for psychiatric problems were also used in five studies [10, 23, 28, 29, 41], and codes related to other methods of suicide or self-harm such as jumping or cutting were used in two studies [28, 39] (Table 3).

When considering only the specific codes for suicidal behavior and the classification that includes them, the most used codes were E950-E959 (suicide and self-inflicted injury), E980-E989 (injury undetermined whether accidentally or purposely inflicted) and V62.84 (suicidal ideation) of the ICD-9 [10, 22, 25, 26], and X84 (intentional self-harm by unspecified means) of the ICD-10 [10, 22]. Code 25 (psychiatric/suicide attempt) of the MPDS was used [23, 29] and code P77 (suicidal behavior) of the ICPC-2 [32]. In studies applying the UECC Classification system, the most used term was suicidal behavior (self-injury and suicidal tendency, suicidal thoughts, suicide threat, and suicide) [20, 25, 31].

Alternatively, some studies used codes for intoxication, poisoning or drug abuse, or psychiatric problems that do not specify whether they are suicidal. These include, for example, 305, 969, E980-E989 of the ICD-9 [10, 22] and E850-E859, E860-E869 [26]. When the AMPDS was used, a group of psychiatric codes were included [28]. In some cases, a suicide code was reported without indicating the classification [30, 37–39] (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to analyze studies on suicidal behavior in EMS in order to identify the classification systems and codes used as well as the professional assigning the codes and the moment at which they are assigned. The main finding of our study is that there is a wide variety of classification systems and codes used in the reviewed studies. Similarly, the description of the recording of information varied considerably both by the professional classifying the call and the moment at which it is collected. In addition, in many of the studies this information was not indicated.

On the moment of call classification and the professional classifying calls

The results of this review show that in a higher proportion of the studies the assignment of classification and suicide codes is made by the physician at the time of attending the emergency on site, followed by a lower percentage of the studies in which the telephone operators perform this classification when answering the call. Considering that on many occasions certain emergencies, such as pill taking, poisoning, self-trauma, etc., may not be related to suicidal behavior, it is logical that the clinical judgment of the physician attending the person on site has greater weight in establishing whether the behavior is suicidal than the telephone operator, since the physician is better able to assess and analyze the situation and obtain more information about the intentionality of the act. However, the qualitative study by Blanco-Sánchez et al. (2018) indicates that there is disagreement as to who should establish whether the call is for suicidal behavior. While the telephone operators believe that the healthcare professionals at the scene should determine whether the call involves suicidal behavior, the healthcare professionals believe that their role is not to determine when an act was intentional, since their priority is to save the person's life, and they consider that the assessment of intentionality should be made later in the hospital services [43].

On classifications and codes

We found that international classifications, such as the ICD-9 and ICD-10 [44, 45], and protocol-based computer systems, such as the MPDS and the AMPDS [46], are the most commonly used when recording calls for suicidal behavior. We also found an internally developed classification used in Andalusia (Spain), created by the UECC, which is based on 14 categories and does not follow any of the international classifications [20, 25, 31]. In addition, a classification used in primary care by family physicians, the ICPC-2, was used in the out-of-hospital setting [47]. The use of international classifications of diseases such as the ICD can help to standardize the collection of information and allow comparisons to be made. However, the use of the UECC classification, which is specific to a single autonomous community in Spain (Andalusia), prevents comparisons even within the country itself.

Another advantage of the international classifications cited above is that they have specific codes referring to suicide and self-injury that are used to record calls for suicidal behavior. Nonetheless, our results show that these calls are recorded using a wide variety of codes, many of which are not specific to suicide. Specifically, in addition to the codes specific to suicide, others are used that refer to intoxication, poisoning or drug abuse, mental health problems, and other methods of harm such as jumping or cutting. Although the existing literature indicates that the causes mentioned are closely related to suicidal behavior, it cannot be confirmed that all cases of intoxication, cutting, or jumping are suicidal behavior. Thus, in many studies, the calls for suicidal behavior could be overestimated.

Several studies also include in the group of calls for suicidal behavior those classified as intentional overdose/poisoning [10, 22, 26, 28, 30, 37–39]. This is because intoxication by drugs or noxious substances is a method frequently used in cases of suicide attempts [15, 48–50]. However, caution should be exercised when considering intoxication, poisoning, or drug abuse as suicidal behavior, as the lack of information on intentionality could be adding false positives to this group of calls. Several studies have shown that there is an increasing misclassification of suicides as poisonings [51–53], which would lead to misreporting of suicides.

The existing literature on suicide indicates that in order to consider a behavior or an associated act as suicidal (intoxication, jumping, cutting, etc.), there must be intent to die [54–56]. However, several studies indicate that in EMS the major barriers encountered by health professionals (physicians, nurses, or ambulance personnel) when classifying a call as suicide or attempted suicide are determining the intentionality of the act [40, 43], the absence of protocols, and insufficient training to manage this type of situation [57, 58].

We also note that the ICD-9 and ICD-10 are the most commonly used classifications. In cases referring to suicide, self-inflicted injuries, poisoning, and psychiatric problems, the codes used are standardized classifications and are usually the same. Nevertheless, in many instances, the codes used are not specific to suicidal behavior but also refer to psychiatric problems, suicidal behavior, or other methods of self-injury. This variability in the codes used may be explained by differences in the training received by the professionals and the information collected at the scene.

The intentionality of the act and the variety of methods for classifying suicidal behavior or self-injury highlight the complexity of the concept of suicide and can therefore lead to an underestimation or overestimation of suicidal behavior. There is a need for a thorough understanding of the characteristics of suicidal behavior and an awareness that there may also be risk behaviors that involve self-destruction of the person without deliberate intent to die, such as the abuse of drugs, alcohol, or other substances [51].

Finally, this systematic review shows that there is a lack of information concerning the classifications used to record calls for suicidal behavior, as they are not provided in half of the included studies. We cannot be certain whether this lack of information is due to the different studies not including these data or to the EMS not using specific classifications to record suicidal behavior, since it is very difficult to assess it accurately. Problems arising from the definition of suicidal behavior may affect the accuracy of data recording, which is consistent with the study by Miret et al. (2010), in which they observed that suicide attempts had very low recording rates in emergency department clinical reports [59].

Among the limitations of our systematic review, we highlight the exclusion of studies in languages other than Spanish and English, with the consequent loss of information on the subject. In addition, we did not include gray literature in our search. The variability and lack of information on the outcome variables are also limitations of our review. The included studies are framed in a transition period between the use of ICD-9 and ICD-10, which would explain the variability in the classifications for assigning calls for suicidal behavior. All this makes it very difficult to draw precise conclusions on the classification of calls for suicidal behavior in EMS.

In conclusion, the lack of consensus on the use of classifications and codes in EMS poses a problem in identifying and quantifying suicidal behavior. This may have a direct impact on the medical care received by this group of individuals. Therefore, improving the classification of suicidal behavior in the out-of-hospital setting by training professionals working in this area could improve care of suicide-related cases.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: TableS1. Manual for the quality rating of qualitative studies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Maria Repice for revising the English text.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Javier Ramos-Martín, María de los Ángeles Contreras-Peñalver, and Berta Moreno-Küstner. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Javier Ramos-Martín, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Fundación Pública Andaluza Progreso y Salud (AP-0226–2019).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Javier Ramos-Martín, Email: JavierRamos@uma.es.

Berta Moreno-Küstner, Email: bertamk@uma.es.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Preventing suicide: A global imperative. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Suicide in the world. Global Health Estimates. Geneva: WHO; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, McKean AJ. Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(11):1094–1100. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Suicide. Geneva: WHO; [updated 2019 Sept 2; cited 2021 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide.

- 5.Mann J, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hegerl U, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294(16):2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Leo D, Bertolote J, Lester D. Self-Directed Violence. In: Krug E, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, Zwi A, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO; 2002. pp. 183–212. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:909–916. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turecki G, Brent DA. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet. 2016;387(10024):1227–1239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu BP, Lui X, Jia CX. Characteristics of suicide completers and attempters in rural Chinese population. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;70:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mejías-Martín Y, Martí-García C, Rodríguez-Mejías C, Valencia-Quintero JP, García-Caro MP, de Dios J. Suicide attempts in Spain according to prehospital healthcare emergency records. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pacheco A, Burusco S, Senosiáin M. Prevalencia de procesos y patologías atendidos por los servicios de emergencia médica extrahospitalaria en España. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2010;33(supl.1):37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magalhães AP, Alves V, Comassetto I, Costa P, Faro AC, Nardi AE. Pre-hospital attendance to suicide attempts. J Bras Psiquiatr. 2014;63(1):16–22. doi: 10.1590/0047-2085000000003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott J, Strickland AP, Warner K, Dawson P. Frequent callers to and users of emergency medical systems: a systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(8):684–691. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-202545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin CJ, Lu HC, Sun FJ, Fang CK, Wu SI, Liu SI. The characteristics, management, and aftercare of patients with suicide attempts who attended the emergency department of a general hospital in northern Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc. 2014;77(6):317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawashima Y, Yonemoto N, Inagaki M, Yamada M. Prevalence of suicide attempters in emergency departments in Japan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2014;163:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreno-Küstner B, González F. Subregistro de los suicidios en el Boletín Estadístico de Defunción Judicial en Málaga. Gac Sanit. 2019;34(6):624–626. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakravarthy B, Hoonpongsimanont W, Anderson CL, Habicht M, Bruckner T, Lotfipour S. Depression, suicidal ideation, and suicidal attempt presenting to the emergency department: differences between these cohorts. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(2):211–216. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2013.11.13172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roggenkamp R, Andrew E, Nehme Z, Cox S, Smith K. Descriptive analysis of mental health-related presentations to emergency medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(4):399–405. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2017.1399181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guzmán-Parra J, Martínez-García AI, Guillén-Benítez C, Castro-Zamudio S, Jiménez Hernández M, Moreno-Küstner B. Factores asociados a las demandas psiquiátricas a los servicios de urgencias prehospitalarios de Málaga (España) Salud Ment. 2016;39(6):287–294. doi: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2016.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers form a variety of fields. Alberta: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mejías-Martín Y, Castillo J, Rodríguez-Mejías C, Martí-García C, Valencia-Quintero JP, García-Caro MP. Factors associated with suicide attempts and suicides in the general population of Andalusia (Spain) Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4496. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creed JO, Cyr JM, Owino H, Box SE, Ives-Rublee M, Sheitman BB, Steiner BD, Williams JG, Bachman MW, Cabanas JG, Myers JB, Glickman SW. Acute crisis care for patients with mental health crises: initial assessment of an Innovative Prehospital Alternative Destination Program in North Carolina. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(5):555–564. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2018.1428840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferreira TD, Vedana KG, do Amaral LC, Pereira CC, Zanetti AC, Miasso AI, Borges TL. Assistance related to suicidal behavior at a mobile emergency service: Sociodemographic and clinical associated factors. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2019;33:136. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2018.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreno-Küstner B, Campo-Ávila J, Ruiz-Ibáñez A, Martínez-García AI, Castro-Zamudio S, Ramos-Jiménez G, Guzmán-Parra J. Epidemiology of Suicidal Behavior in Malaga (Spain): an approach from the Prehospital Emergency Service. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:111. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Celada FJ, Quiroga-Fernández A, Mohedano-Moriano A, Aliaga I, Cristina F, Martín JL. Evolución de la tentativa suicida atendida por los Servicios de Emergencias Médicas de Castilla-La Mancha tras la crisis económica. Emerg. 2018;30(4):247–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crossin R, Scott D, Witt KG, Duncan JR, Smith K, Lubman DI. Acute harms associated with inhalant misuse: Co-morbidities and trends relative to age and gender among ambulance attendees. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;190:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan EAS, Best C, Dougall N, Skar S, Evans J, Corfield AR, Fitzpatrick D, Goldie I, Maxwell M, Snooks H, Stark C, White C, Wojcik W. Epidemiology of emergency ambulance service calls related to mental health problems and self-harm: a national record linkage study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2019;27(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s13049-019-0611-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gratton M, Garza A, Salomone JA, 3rd, McElroy J, Shearer J. Ambulance staging for potentially dangerous scenes: another hidden component of response time. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010;14(3):340–344. doi: 10.3109/10903121003760176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holzer BM, Minder CE, Schätti G, Rosset N, Battegay E, Müller S, Zimmerli L. Ten-year trends in intoxications and requests for emergency ambulance service. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012;16(4):497–504. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2012.695437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiménez-Hernández M, Castro-Zamudio S, Guzmán-Parra J, Martínez-García AI, Guillén-Benítez C, Moreno-Küstner B. Las demandas por conducta suicida a los servicios de urgencias prehospitalarios de Málaga: características y factores asociados. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2017;40(3):379–389. doi: 10.23938/ASSN.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johansen IH, Morken T, Hunskaar S. Contacts related to mental illness and substance abuse in primary health care: a cross-sectional study comparing patients´ use of daytime versus out-of-hours primary care in Norway. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2010;28(3):160–165. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2010.493310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.John A, Okolie C, Porter A, Moore C, Thomas G, Whitfield R, Oretti R, Snooks H. Non accidental non-fatal poisonings attended by emergency ambulance crews: an observational study of data sources and epidemiology. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011049. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kayipmaz S, Korkut S, Usul E. The investigation of the use of emergency medical services for geriatric patients due to suicide. Turk J Geriatr. 2020;23(1):82–89. doi: 10.31086/tjgeri.2020.141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kayipmaz S, San I, Usul E, Korkut S. The effect of meteorological variables on suicide. Int J Biometeorol. 2020;64:1593–1598. doi: 10.1007/s00484-020-01940-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SJ, Shin SD, Lee EJ, Ro YS, Song KJ, Lee SC. Epidemiology and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest according to suicide mechanism: a nationwide observation study. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2015;2(2):95–103. doi: 10.15441/ceem.15.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krayeva YV, Brusin KM, Bushuev AV, Kondrashov DL, Sentsov VG, Hovda KE. Prehospital management and outcome of acute poisonings by ambulances in Yekaterinburg. Russia Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2013;51(8):752–760. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.827707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maignan M, Viglino D, Muret RC, Vejux N, Wiel E, Jacquin L, Laribi S, N-Gueye P, Joly LM, Dumas F, Beaune S, IRU-SFMU Group Intensity of care delivered by prehospital emergency medical service physicians to patients with deliberate self‑poisoning: results from a 2‑day cross‑sectional study in France. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14(6):981–988. doi: 10.1007/s11739-019-02108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuyama T, Kitamura T, Kiyohara K, Hayashida S, Kawamura T, Iwami T, Ohta B. Characteristics and outcomes of emergency patients with self-inflicted injuries: a report from ambulance records in Osaka City, Japan. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:68. doi: 10.1186/s13049-016-0261-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mejías-Martín Y, García MP, Schmidt J, Quero A, Gorlat B. Estudio preliminar de las características del intento de suicidio en la provincia de Granada. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2011;34(3):431–441. doi: 10.4321/S1137-66272011000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scott J, Strickland AP, Warner K, Dawson P. Describing and predicting frequent callers to an ambulance service: analysis of 1 year call data. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(5):408–414. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-202146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veloso C, Monteiro LS, Veloso LU, Moreira IC, Monteiro CF. Psychiatric nature care provided by the urgent mobile prehospital service. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2018;27(2):e0170016. doi: 10.1590/0104-07072018000170016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blanco-Sánchez I, Barrera-Escudero M, Martínez-Martínez S, Mejías-Martín Y, Morales-García JA, García-Caro MP. Experiencia de los profesionales en la determinación de la situación de un intento de suicidio en urgencias extrahospitalarias. Presencia. 2018;14:e11658. [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization . International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision. Geneva: WHO; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization . International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision. Geneva: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 46.International Academies of Emergency Dispatch. The Medical Priority Dispatch System. [Cited 2021 Mar 13]. Available from https://www.emergencydispatch.org/what-we-do/emergency-priority-dispatch-system/medical-protocol.

- 47.Wonca International Classification Committee. International Classification of Primary Care, 2th edition. [Cited 2021 May 1]. Available from https://ehelse.no/kodeverk/icpc-2e--english-version.

- 48.Cano-Montalbán I, Quevedo-Blasco R. Sociodemographic variables most associated with suicidal behaviour and suicide methods in Europe and America. A systematic review. Eur J Psychol Appl Legal Context. 2018;10(1):15–25. doi: 10.5093/ejpalc2018a2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fernández C, García G, Romero R, Marquina AJ. Intoxicaciones agudas en las urgencias extrahospitalarias. Emergencias. 2008;20(5):328–331. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hawton K, Bergen H, Cooper J, Turnbull P, Waters K, Ness J, Kapur N. Suicide following self-harm: Findings from the Multicentre Study of self-harm in England, 2000–2012. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rockett IRH, Hobbs G, De Leo D, Stack S, Frost JL, Ducatman AM, et al. Suicide and unintentional poisoning mortality trends in the United States, 1987–2006: two unrelated phenomena? BMC Public Health. 2010;10:705. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gunnell D, Bennewith O, Simkin S, Cooper J, Klineberg E, Rodway C, et al. Time trends in coroners’ use of different verdicts for possible suicides and their impact on officially reported incidence of suicide in England: 1990–2005. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1415–1422. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chan CH, Caine ED, Chang SS, Lee WJ, Cha ES, Yip ES. The impact of improving suicide death classification in South Korea: a comparison with Japan and Hong Kong. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Carroll PW, Berman AL, Maris RW, et al. Beyond the tower of babel: a nomenclature for suicidiology. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1996;26:237–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1996.tb00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hawton K, Harriss L, Hall S, Simkin S, Bale E, Bond A. Deliberate self-harm in Oxford, 1990–2000: a time of change in patient characteristics. Psychol Med. 2003;33:987–996. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703007943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silverman MM, Berman Al, Sanddal ND, et al. Rebuilding the tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 2: a suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37:264–77. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nelson PA, Cordingley L, Kapur N, Chew-Graham CA, Shaw J, Smith S, McGale B, McDonnell S. ‘We’re the first port of call’ – Perspectives of ambulance staff on responding to deaths by suicide: a qualitative study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:722. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vedana KG, Magrini DF, Miasso AI, Zanetti ACG, Souza J, Borges TL. Emergency nursing experiences in assisting people with suicidal behaviour: a grounded theory study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31(4):345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miret M, Nuevo R, Morant C, Sainz-Cortón E, Jiménez-Arriero MA, López-Ibor JJ, Reneses B, Saiz-Ruiz J, Baca-García E, Ayuso-Mateos JL. Calidad de los informes médicos sobre personas que han intentado suicidarse. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2010;3(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/S1888-9891(10)70003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: TableS1. Manual for the quality rating of qualitative studies.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).