Abstract

Sonodynamic therapy (SDT) is a novel promising approach for the minimally invasive treatment of cancer derived from photodynamic therapy (PDT). In this study, we have explored an effective sonosensitizer for SDT by loading the iridium(III) complex [Ir(ppy)2(en)] OOCCH3, where ppy = 2-phenylpyridine and en = ethylenediamine], from now on referred to as Ir, with high photosensitizing ability, into echogenic nanobubbles (Ir-NBs). Akin to photosensitizers, sonosensitizers are acoustically activated by deep-tissue-penetrating low-frequency ultrasound (US) resulting in a localized therapeutic effect attributed to an excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The Ir-NB formulation was optimized, and the in vitro characterizations were carried out, including physical properties, acoustic performance, intracellular ROS generation, and cytotoxicity against two human cancer cell lines. Ir-NBs had an average size of 303.3 ± 91.7 nm with a bubble concentration of 9.28 × 1010 particles/mL immediately following production. We found that the initial Ir feeding concentration had a negligible effect on the NB size, but affected the bubble concentration as well as the acoustic performance of the NBs. Through a combination of sonication and Ir-NBs treatment, an increase of 68.8% and 69.6% cytotoxicity in human ovarian cancer cells (OVCAR-3) and human breast cancer cells (MCF-7), respectively, was observed compared to the application of Ir-NBs alone. Furthermore, Ir-NBs exposed to the US also induced the highest levels of intracellular ROS generation compared to free Ir and free Ir with empty NBs. The combination of these results suggests that the differences in treatment efficacy is a direct result of acoustic cavitation. These results provide evidence that US activated Ir-loaded NBs have the potential to become an effective sonosensitizer for SDT.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, transition metal complexes have attracted growing interest as imaging probes and therapeutic agents for light-mediated cancer theranostics. This is due to their rich and advantageous photophysical properties.1–4 Unlike organic molecules, the presence of a heavy-metal center in these complexes induces a strong spin–orbit coupling, resulting in emission processes exhibiting long excited-state lifetimes and significant Stokes shifts, both of which are ideal characteristics for bioimaging modalities.5,6 In addition to their optimal imaging properties, transition metal complexes also exhibit excellent photosensitizing abilities in the application of photodynamic therapy (PDT). This arises from their ability to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), for example, singlet oxygen, 1O2, which is able to cause oxidative stress and trigger cell death mechanisms.7 Phosphorescent octahedral iridium(III) compounds especially have been extensively investigated via one- and two-photon light activation, and proven efficient photosensitizers, after leading to 1O2 generation quantum yields up to near-unity.8–10 Despite their growing potential in several fields, the widespread clinical use of transition metal complexes as well as conventional photosensitizers has been hindered due to the limited tissue penetration depth of millimeters to a few centimeters of the triggering light responsible for their therapeutic capabilities. This poor penetration, in turn, gives rise to a poor ability in treating deeper tumors, and a limited range of applicability for the treatment method as a whole.11

Sonodynamic therapy (SDT) is an emerging approach for minimally invasive cancer treatment that has arisen from the development of PDT due to their similar therapeutic mechanisms.12,13 Compared to the traditional light-mediated technique, SDT provides the advantage of activating the tumor-localized drug agents at deeper locations, sometimes up to tens of centimeters.14 This greater depth of penetration is made possible through the use of low-frequency ultrasound (US). This method was first explored in 1989 by Umemura et al., who reported the cytotoxic activity of hematoporphyrin upon ultrasonic exposure.15 It was hypothesized that the cytotoxiciy was a result of the photoactivation of the sensitizer leading to ROS generation through the emission of light. This ROS production was believed to arise from the rapid collapse of bubbles during acoustic cavitation resulting in a phenomenon known as sonoluminescence, which is capable of causing cell damage.16 Following these findings, additional studies on the US-mediated generation of ROS have been carried out using several porphyrin-based molecules.13,17–21 Similarly, to the photosensitizers utilized in PDT, the acoustically triggered agents used in these studies to further develop SDT methods are typically named sonosensitizers.

Microbubbles (MBs) are gas-filled colloidal particles with a diameter between 1 and 8 μm and are clinically used as US contrast agents. MBs are comprised of a gas core, which is typically air, nitrogen, or high-molecular-weight gases such as perfluorocarbon or sulfur hexafluoride. This gaseous core is stabilized by a shell membrane, which may be composed of lipids, polymers, surfactants, or a combination of these.22 These bubbles can enhance US backscatter by producing nonlinear acoustic signals while simultaneously improving the localization of drug delivery through their destruction and targeting properties. MBs have become an attractive theranostic agent for cancer therapy due to the simultaneous ability to colocalize contrast for imaging and drug loading including targeted therapy. A broad range of applications in this area are currently under investigation and have progressed toward clinical translation.23–25 Despite the previous clinical success of MBs as theranostic agents, their applications are somewhat limited, as they are too large to passively extravasate out of the bloodstream and get into the targeted organ.26,27 This limitation has given rise to a growing interest in the reduction of the size of MBs into submicron bubbles or nanobubbles (NBs), which would extend their activity into target tissues and cells beyond the vasculature.28 Substantial evidence has shown that NBs can pass through endothelial barriers and escape from the vascular system to reach cells at the tumor site, allowing targeted molecular imaging and drug delivery.29 As the permeability of tumor vasculature is higher than that of normal tissue, NBs are more likely to accumulate in tumors by extravasation via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. Additionally, this effect can be acoustically driven, which promotes US detection and controlled release of a drug when used as a drug delivery vehicle.30,31

Our group has previously developed diagnostic NBs loaded with the anticancer chemotherapy drug doxorubicin (Dox) that can serve as a potential theranostic agent.32,33 We have also combined porphyrin photosensitizers with this NB formulation to obtain a US-activated theranostic agent that takes advantage of SDT activity in vitro.34 We have shown that our NBs can utilize the limited EPR available, including the heterogeneous and variable vascular structure in tumors. This system was successfully applied in tumors of both primary and metastatic origins, proving their robust ability as a diagnostic contrast agent for solid tumors.35 Recently, we reported on an optimized lipid shell-stabilized perfluoropropane (C3F8) gas NB formulation, which has delayed signal decay under US in vitro, and a prolonged in vivo half-life.36,37 The formulation has been explored in several diagnostic and therapeutic applications,38,39 is straightforward to produce, and can be stored at −80 °C for one month with only a minor change in physical properties and acoustic performance.40 As an extension of our previously mentioned system, in this study, we have expanded the application of the stable NB formulation by incorporating an iridium(III) complex (Ir) into the NB shell. This complex has been shown to possess remarkable in vitro photosensitizing abilities.41 For this reason, we decided to investigate the ability of the new nanoplatform Ir-NBs to improve sonotherapeutic treatments efficacy. To this end, we assess the ability of the Ir-NBs to provide enhanced US-mediated ROS generation and the cytotoxic effect on two human cancer cell lines. We also assess the echogenic properties of the Ir-NBs, including US contrast, initial signal enhancement, and signal stability over time. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study where the sound-sensitizing properties of a transition metal complex are explored.

RESULTS

Proof of Principle in Ir-Loaded NBs.

Optical microscopy images (Figure 1a) showed a majority of Ir-NBs with a diameter smaller than 500 nm. Ir-loaded NBs can be distinguished by fluorescence signal of Ir shown as small red dots (Figure 1c). For improved visualization of Ir in the bubble shell, a heterogeneous mixture of Ir-MBs and Ir-NBs was imaged in this experiment; again, Ir-NBs were distinguished by a small dots while the MBs showed a standard bubble morphology with a bright center enclosed by a phospholipid membrane (Figure 1d and e). Under fluorescence microscopy, the colocalization of Ir was visible at the shell of the bubbles, as shown in Figures 1e and f.

Figure 1.

Representative (a) bright-field optical microscopy (100×, 2 μm scale bar), (b) bright-field image, and (c) merged image of Ir-loaded NBs (20×, 20 μm scale bar). NBs loaded with Ir are seen as tiny red dots. Images in (d, e) show bright field and an overlay of the fluorescence images and bright field image (10× zoom) of Ir-loaded bubbles, respectively. The analysis was carried out on the heterogeneous mixture of MBs and NBs before isolation of NB to improve visualization of the bubble shell. Ir-loaded bubbles appeared as a bright ring with red fluorescence visible in the bubble shell (f).

Physical Properties of Ir-NBs.

The average size of the bubble and nonbuoyant particles for all formulations was consistently in the range of 100–500 nm with no particle larger than 1 μm being observed, which is on par with previous reports.33,42 The largest average size of 303.3 ± 91.7 nm was found for Ir1k followed by 300.0 ± 100.0 nm, 295.0 ± 91.7 nm, and 281.3 ± 101.7 nm for Ir100, Ir500, and empty NBs, respectively. Some nonbuoyant particles were present in the sample solution of all formulations, but with various bubbles to micelle ratios, as shown in the histogram plots in Figure 2. An approximated bubble concentration of 1011 particles/mL was found to remain constant across the different formulations, which was consistent with previous reports of drug-loaded NBs.32,33 However, NB loaded with 500 μg Ir or greater showed a significant decrease in bubble concentration as 71.1 ± 21.2% and 84.3 ± 4.7% compared to empty-NBs (p < 0.05), with bubble concentrations of 1.71 × 1011 and 9.28 × 1010 particles per mL corresponding to Ir500 and Ir1k. Conversely, increasing the initial Ir feeding concentration lead to a decrease in the bubble to nonbuoyant particle ratio. Accordingly, the highest amount of bubbles with the least nonbuoyant particles was found in Ir100 followed by Ir500 and Ir1k, respectively. It should be noted that the bubble concentrations of Ir500 and Ir1k are not significantly different from each other (Figure S1a).

Figure 2.

Ir-NBs characterization: Histograms showing the size distribution and concentration of each NB formulation (n = 3): (a) Unloaded-NBs (Empty NBs), Ir-NBs with initial Ir feeding concentration of (b) 100 μg/mL (Ir100), (c) 500 μg/mL (Ir500), and (d) 1000 μg/mL (Ir1k) as measured by RMM. The NB size in the table represents the mean and SD of the distribution.

Acoustic Properties of Ir-NBs.

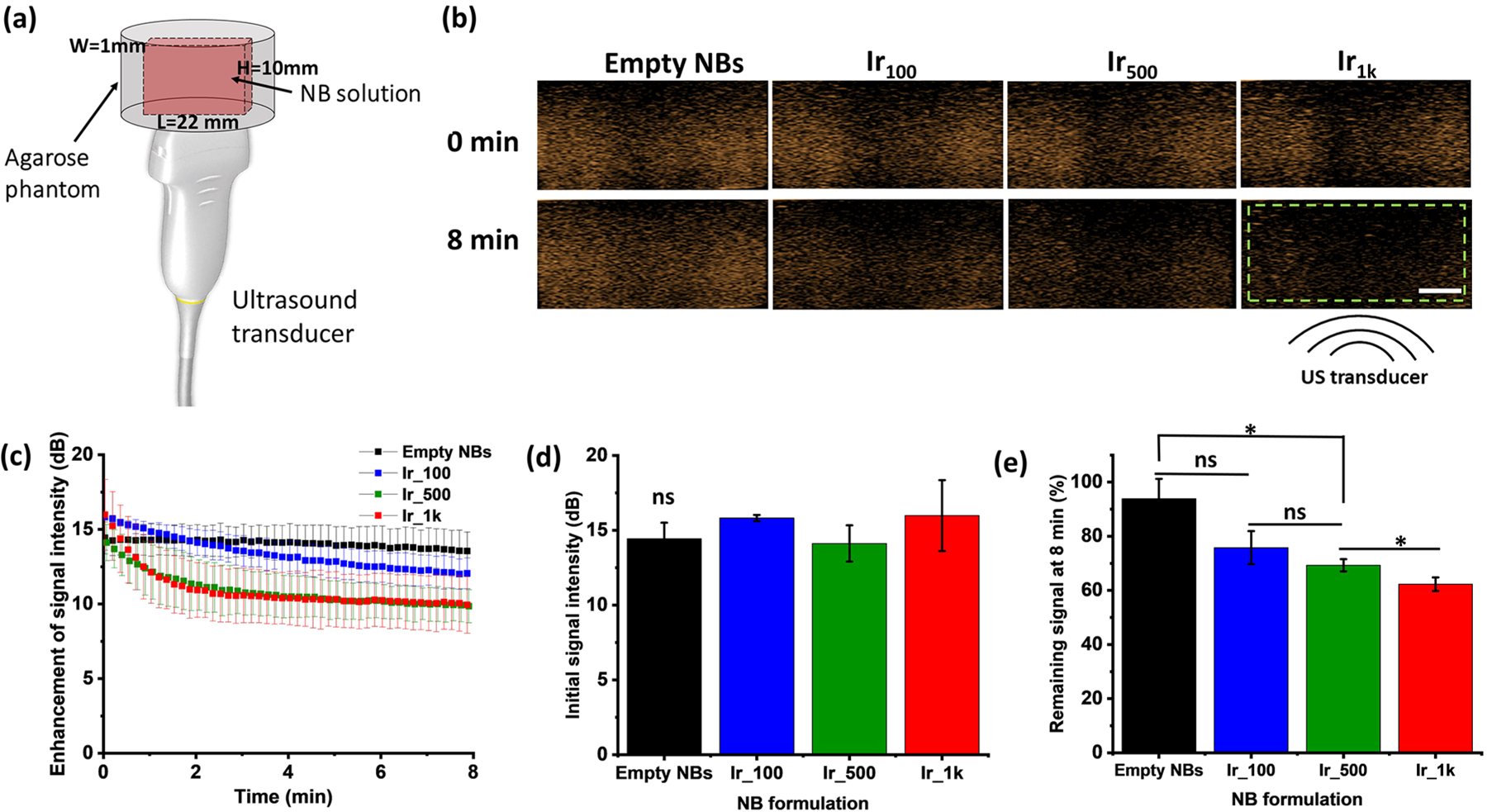

Representative nonlinear US contrast images were obtained for each initial loading concentration in Ir-NBs diluted in PBS and compared to empty NBs at different times after initiation of US exposure. The corresponding signal enhancement over time was shown in Figure 3b and c, which confirms that the Ir-NBs are acoustically active. Initial Ir feeding concentration did not result in any significant differences in the initial signal intensity (dB) compared to control empty NBs (p < 0.05). Although Ir1k has the lowest bubble yield, the initial signal intensity was comparable to control empty-NBs and other formulations (Figure 3d), only differing in US signal after 8 min exposure. The effect of initial Ir feeding concentrations of Ir-NBs on their acoustic stability during continuous insonation was also measured, as shown in Figure 3e. Empty NBs maintained 93.91 ± 7.30% of their initial signal intensity after 8 min. The signal decay is significantly faster for Ir500 and Ir1k as indicated by the lower remaining signal at 8 min of 69.30 ± 2.20% and 62.29 ± 2.50%, respectively.

Figure 3.

In vitro acoustic properties of Ir-NBs (n = 3). (a) Schematic of the experimental setup consists of US transducer and agarose phantom with a thin channel where the sample is placed. (b) Representative US contrast images for each Ir-NB formulation with the analyzed region of interest (green dashed line) and the location of the US beam. The scale bar is 0.5 cm. (c) US signal decay of each formulation over an 8 min exposure period. (d) Differences in initial US signal intensity. All Ir-NB formulations are not significantly different compared to those of empty NBs. (e) Remaining US signal at 8 min (%). The asterisk * indicates p < 0.05, while ns means they are not statistically significantly different.

In Vitro Therapeutic Efficiency of Ir-NBs.

To support our hypothesis that Ir-NBs can work in synergy with low-frequency US to improve treatment efficacy, eight treatment groups were tested with OVCAR-3 and MCF-7 cells: (1) Ir-NBs, (2) Ir-NBs+US, (3) free Ir, (4) free Ir+US, (5) free Ir +empty NBs, (6) free Ir+empty NBs+US, (7) empty NBs, and (8) empty NBs + US. In the absence of the US, no toxicity was observed from the Ir-NBs or the other treatment groups. This suggests that free Ir alone is nontoxic, and does not contribute to the SDT effects. When combined with insonation, we found that Ir-NBs were highly cytotoxic toward OVCAR-3 and MCF-7 cells, but OVCAR-3 cells were overall less sensitive to SDT. Enhanced cytotoxicity in OVCAR-3 is shown in Figure 4a. Free Ir with US exposure showed reduced cell viability at 86.2 ± 16.4%. Co-delivery of free Ir and empty NBs combined with insonation did, however, result in a considerable decrease in cell viability at 47.2 ± 26.7%. Empty NBs alone at an equivalent concentration to Ir-NBs showed reduced cell viability of 78.2 ± 8.3% when exposed to the US. Combined with US exposure, Ir-NBs showed the highest toxicity compared to other groups. Ir-NBs+US significantly reduced cell viability by 68.8%. This suggests that the combination therapy of free Ir and NBs involves the SDT effect, but it is the presence of Ir within the NBs that contributes a much more significant benefit. Similar promising results were observed with MCF-7 cells (Figure 4b). The treatment with Ir-NBs and free Ir plus empty NBs showed significant reductions in cell viability, but treatments resulted in slightly higher toxicity than in OVCAR-3 cells. This implies that SDT efficiency is dependent on cell type.

Figure 4.

Cytotoxicity enhancement in (a) OVCAR-3 cells and (b) MCF-7 cells after treatment with Ir-NBs and ultrasound (+US). Cell viability of both cells for different treatments were normalized to the untreated control: When US is not present, Ir-NBs, free Ir, or free Ir+empty NBs have equivalent baseline toxicity. With US application, the Ir-NBs have the highest cytotoxicity as shown in the greatest reduction in cell viability compared to free Ir and free Ir coinjected with empty NBs for both cell lines. Assays were carried out in triplicate. Error bars represent standard deviation. The asterisk * indicates p < 0.05.

Intracellular ROS Generation.

Intracellular ROS generation in both OVCAR-3 and MCF-7 cells was determined using the DCFDA ROS detection assay. Figure 5 demonstrates that ROS level increased significantly with exposure to US compared to without US in both cell lines. ROS generation from US alone was negligible in control groups (only cell in media) of both cell lines. In the case of OVCAR-3, cells treated with Ir-NBs+US showed the highest ROS signal compared to free Ir and the combination of free Ir and empty-NBs. This suggests that SDT can induce more ROS generation, resulting in cell death beyond that of cavitation-mediated effect alone. However, free Ir with or without the US, nonetheless, showed significant elevation in ROS generation. ROS generation from empty-NBs+US was significantly lower than that of Ir-NBs, yet was notably elevated compared to the unsonicated control. OVCAR-3 showed about 2-fold increase in ROS level compared to MCF-7, which is consistent with the strong ROS fluorescence signal in confocal images (Figure 7). Interestingly, despite the generally lower ROS level, MCF-7 cells were much more susceptible to the treatment compared to OVCAR-3 cells. The difference of ROS level between cells treated with and without US is significantly different and higher compared to OVCAR-3. This result suggests that NB acoustic cavitation mostly regulates SDT-induced cytotoxicity in MCF-7.

Figure 5.

Intracellular ROS production in (a) OVCAR-3 cells and (b) MCF-7. Quantification of fluorescence intensity shows remarkable intracellular increases in ROS generation following the combination of Ir-NBs and US compared to free Ir and free Ir+empty NBs with the present and absence of the US. Assays were carried out in triplicate. Error bars represent standard deviation. The asterisk * indicates p < 0.05.

Figure 7.

Confocal fluorescence images showing ROS generation in MCF-7 cells treated with (a) Ir-NBs+US, (b) Ir-NBs, (c) Free Ir+US, (d) Free Ir, (e) Free Ir+empty NB+US, (f) Free Ir+ empty NB, (g) Empty NB+US, and (h) Empty NB using DCFDA an intracellular fluorescent ROS probe. The Ir and ROS signals were colored in red and green in each panel, respectively. The scale bar is 25 μm.

Confocal Microscopy Analysis.

The intracellular uptake of Ir-NBs and ROS imaging of two human tumor cells induced by SDT of Ir-NBs was investigated by confocal fluorescence microscopy. ROS levels were detected using DCFDA dye as a fluorescent probe. As shown in Figures 6 and 7, no obvious ROS fluorescent signals were observed in the control groups. Following all treatments, the bright red luminescence signal of Ir was found to be present in all groups, regardless of the US exposure. This highlights that the localization of Ir within the cells was mainly in the cytoplasm.43 Upon sonication with the low-frequency US, cells treated with Ir-NBs had the brightest green fluorescence intensity of DCF, which is proportional to the amount of ROS produced by the cells. This clearly shows that the combination of Ir-NBs+US leads to the highest generation of intracellular ROS. A dense packing of Ir within a single NB could allow for substantial therapeutic efficacy given the need for spatial–temporal localization of Ir-NBs for effective SDT.13 The morphological change was also observed in the group of Ir-NBs+US, while in all other groups, the cells appear with well-defined structure. In the group of Ir-NBs+US, most of the cells were detached, shrunk, aggregated, and lost their membrane integrity. Changes in cell morphologies such as irregular cell surface, pores in the membrane, decreased in cell density, and cell shrinkage can be caused immediately after sonoporation as the effect of sonoporation.44,45 This evidence confirms that the presence of SDT could be from the combined effect of bubble cavitation and ROS-triggered cell death.

Figure 6.

Confocal fluorescence images showing ROS generation in OVCAR-3 cells treated with (a) Ir-NBs+US, (b) Ir-NBs, (c) Free Ir+US, (d) Free Ir, (e) Free Ir+empty NB+US, (f) Free Ir+ empty NB, (g) Empty NB+US, and (h) Empty NB using DCFDA an intracellular fluorescent ROS probe. The Ir and ROS signals were colored in red and green in each panel, respectively. The scale bar is 25 μm. Ir signal were mainly found in the cytoplasm in all treatment groups. The highest ROS signal was found in the group of Ir-NBs+US.

DISCUSSION

SDT has emerged as a promising alternative to PDT for the minimally invasive treatment of deep-seated tumors.46 Microbubbles (MBs), an ultrasound contrast agent, have served as preformed cavitation nuclei and contributed to the increased therapeutic effects of SDT.47–50 However, therapeutic benefits in cancer treatment of MBs are still limited due to their large size of 1–8 μm. Alternatively, submicron bubbles or nanobubbles (NBs) with smaller size in the range 100–500 nm can promote extravasation by taking advantage of the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, resulting in higher drug accumulation in tumors and improved efficacy.33,35,51 Several studies highlighted enhancing SDT through nanomedicines such as increasing drug delivery to tumor cells, amplifying ROS generation, or providing alternative pathways to sonosensitization.47–49 Accordingly, we have expanded the application of our previously developed, lipid shell-stabilized NB formulation36 and incorporated the photosensitizer, Ir(III) complex, into the bubble shell.41 In this work, we examined whether inclusion of a photosensitizer within the NB shell, when combined with a low-frequency US, is capable of enhancing SDT efficacy. To accomplish the goals of this study, the Ir-NB formulation was optimized, and the in vitro characterizations were carried out, including physical properties, acoustic performance, intracellular ROS generation, and cytotoxicity against two human cancer cell lines.

The Ir(III) complex was synthesized and characterized according to a previously reported procedure52 and then successfully loaded into the shell of the NBs. The morphology of the Ir-loaded bubbles and the colocalization of Ir were observed with a fluorescence microscope as shown in Figure 1. NBs with Ir cannot be easily visualized because the size of the NBs falls below the diffraction limit of light; therefore, the MB population was used to accurately visualize colocalization with Ir. NBs with different Ir loading concentrations (100, 500, and 1000 μg/mL denoted, respectively, as Ir100, Ir500, and Ir1k) were prepared, and their physical properties and in vitro echogenicity were evaluated. The size distribution and concentration of the NBs from different initial Ir concentrations were characterized by resonant mass measurement (RMM). The particle buoyant mass can be detected by measuring the change in frequency of a resonator as individual particles interact with it, resulting in the ability to evaluate if populations of different densities (bubbles vs nonbuoyant particles) are present in samples.53 Bubbles were loaded with initial Ir concentrations up to 1000 μg without any significant difference in particle size compared to control empty-NBs (p < 0.05), even though an increasing size trend was observed (Figure S1b). RMM results reveal a combination of buoyant (Ir-NBs) and nonbuoyant particles (Ir-micelles/liposome) with an average size of 303.3 ± 91.7 nm and 217.0 ± 86.7, respectively. DLS results point to a relatively uniform particle with a mean diameter of 334.4 ± 23.2 nm (Figure S2). This is consistent with microscopy images (Figure 1a and c) where the Ir-NBs show monodisperse size smaller than 500 nm. Acoustic property analysis indicates that the addition of Ir to NB shells does not interfere with the formation of echogenic NB. Therapeutic efficacy assessment results show that nanoparticles within this size range play a major role in the observed beneficial in vitro therapeutic effects. A recent study from our group shows that a narrow NB size distribution can be obtained using a filtration technique.54 NB size distribution and shell component clearly do affect their acoustic response, and the more uniform bubble size can be “tuned” better to respond at a specific pressure.

The effect of initial Ir feeding concentrations on NB acoustic properties was assessed by imaging with diagnostic US, as previously reported.36 Briefly, the setup consists of placing sample solutions into a tissue-mimicking agarose phantom placed directly over an US transducer, as shown in Figure 3a. NBs loaded with initial Ir concentration greater than 500 μg/mL did show significantly faster signal decay compared to empty NBs. The observed increasing signal decay corresponds with the increase in the size of Ir500 and Ir1k, which is expected, since it was reported that the attenuation coefficients scale with size.55 This implies that the increase in the size of Ir-NBs as the Ir loading concentration increases is likely a result of the increase of the Ir complex to lipid ratio on the NB shell. Once this relationship was established, we were able to move forward and determine if the combinatory treatment of both Ir-NBs and US could induce the generation of toxic ROS in cells. Due to the scope of this study, we will examine the actual Ir loading in future work. The acoustic stability of Ir-NB exposed to US was significantly reduced for Ir500 and Ir1k samples. This phenomenon corresponds with previous studies where either Paclitaxel or Doxorubicin hydrochloride was incorporated in the MB shell.56,57 For the sake of this study, the decreased stability was of relatively minor concern, as it is advantageous for the SDT to use the highest possible Ir content. For this reason, the Ir1k was selected as the optimal formulation for the following in vitro sonodynamic efficiency characterization. In future in vivo studies, the stability of Ir-NBs will become of critical importance, and thus the Ir loading maybe reduced to increase NB longevity.

The cytotoxic effect of sonodynamic therapy (SDT) using Ir-NBs was evaluated in human ovarian cancer (OVCAR-3) and breast cancer (MCF-7) cell lines, as shown in Figure 4. Other studies have shown that the application of sensitizer-loaded nanoparticles followed by exposure to low-frequency US (1–3 MHz) with intensity of 0.5–5 W/cm2 has several promising advantages such as (1) protection of the sonosensitizer from physiological environment; (2) promotion of ROS production; (3) lower cavitation threshold; and (4) enhancement of tumor accumulation.58–61 Additionally, it has been reported that SDT of NBs/droplets can act as cavitation nuclei and enhance sensitizer tumor penetration.34,62 The cytotoxic effects observed could, in part, be caused by mechanical stress resulting from acoustic cavitation and/or the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).63,64 The sonomechanical mechanism governing SDT is acoustic cavitation associated with endogenous bubbles or cavitation nuclei, which are typically located in cellular cytoplasm.65 The collapse of these inherent gas bubbles due to an increasing acoustic pressure above a certain threshold called inertial cavitation creates strong shear force resulting in an adequate stress to damage the cell membrane in nearby environments.66,67 Accordingly, our Ir-NBs could help lower the inertial cavitation pressure threshold for SDT events at equivalent or lower acoustic intensity, because they serve as potential preformed cavitation nuclei, which have acoustic behavior similar to that of endogenous formed bubbles. ROS-based mechanisms are thought to be a predominant cause in the biological effects of SDT. At a high intracellular ROS level, apoptotic cell death can be induced by DNA damage, disruption of mitochondria membrane potential, activation of Fas death receptor pathway, or loss in cell membrane integrity.68–71 Based on inertial cavitation, two potential mechanisms of actions have been suggested to explain the generation of ROS are (1) sonoluminescence and (2) pyrolysis.72 Sonoluminescence light is the emission of short bursts of light from an imploding bubble, which can transiently trigger the sonosensitizer to generate cytotoxic singlet oxygen (1O2). Alternatively, a substantial increase in local temperature generated from bubble implosion can cause pyrolysis of the sonosensitizer/molecule nearby the ruptured bubbles area to generate cytotoxic free radicals.13 Due to the ability to generate sonoluminescence, amplifying ROS generation could be achieved. These implied that SDT-cytotoxicity could be further enhanced by inclusion of Ir, a photosensitizer, within NB shell.

To better understand the mechanisms that result in the therapeutic effect of the generation of ROS, intracellular ROS generation by Ir-NB was investigated following the application of US to OVCAR-3 and MCF-7 cells (Figure 5). The ROS activity within cells was measured using cell-permeant reagent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA). After DCFDA diffuses into the cells, it is deacetylated by cellular esterase to a nonfluorescent compound. This is later oxidized by ROS into 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) which is a highly fluorescent compound and can be detected by fluorescence spectroscopy.73–75 In this experiment, a fluorescence plate reader was used, exciting the DCFDA probe containing samples at 485 nm, and monitoring the emission at 535 nm. The Ir, however, displays an intense emission band in the range 475–625 nm with the peak at 515 nm, meaning it is plausible that by using 485 nm as excitation wavelength, we excite not only the probe but also the Ir, which emits a signal in the same range as the probe. Therefore, in the absence of US exposure, what we observed in all the samples where the free Ir is present is likely not the ROS generation but the signal coming from the Ir.

Confocal imaging was used to determine the cellular uptake and intracellular distribution of free Ir and Ir-NBs. The red signal of Ir was found to be present in all groups, regardless of the US exposure. This highlights that either free Ir or Ir-NBs were internalized into the cells and significant intracellular staining of Ir mainly in the cytoplasm as shown in Figures 6 and 7. Combined with the US stimulation, particles could migrate from cytoplasm to the mitochondria resulting in enhanced delivery.76 In addition, sonoluminescence generated from inertial cavitation could also be attributed to amplified ROS generation and increased SDT-mediated cytotoxicity.50 Accordingly, the intracellular ROS generation found in Ir-NB group were from both cavitation and sonodynamic effects.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we successfully developed photosensitizer-loaded NB. We were able to present an activatable molecule containing the iridium(III) complex that has the following characteristics: (1) high sensitizing ability, due to the triplet nature of its excited state; (2) water-solubility, which is a useful property for the incorporation process into NB lipid shell and finally; (3) luminescence, a feature that allows its detection within the nanostructure. We believe that acoustic cavitation generated from these Ir-NBs exposed to low-frequency US has to be the source of SDT-triggered ROS generation that can significantly enhance the in vitro therapeutic efficiency. The results demonstrate that the combination of the Ir and NB treatment can be utilized as a potential sonosensitizer for advancing SDT for cancer treatment. Importantly, Ir-NBs is a promising tool for highly efficient SDT that can be used to treat a broad range of deeper and less accessible tumors than its close relative PDT with an add benefit of nanomedicine.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials.

Lipids including DBPC (1,2-dibehenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), DPPA (1,2 dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate), and DPPE (1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Pelham, AL), and mPEG-DSPE (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (ammonium salt)) was obtained from Laysan Bio, Inc.(Arab, AL). Propylene glycol (PG) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). Glycerol was purchased from Acros Organics (Morris, NJ). Human ovarian cancer cells (OVCAR-3) and breast cancer cells (MCF-7) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). The Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 and Minimum Essential Media (MEM) enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin, trypsin–EDTA were purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). The cell proliferation reagent WST-1 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). The cellular ROS fluorogenic dye (2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate or DCFDA) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA).

Formulation of Ir-NBs.

NBs were formulated as previously reported.36,37,77 Lipids including DBPC, DPPA, DPPE, and DSPE-mPEG were dissolved in propylene glycol by heating and sonicating at 80 °C until all the lipids were completely dissolved. A mixture of glycerol, Ir (100 μg/mL, denoted as Ir100), and phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) was added to the lipid solution (final volume of 5 mL). The solution was sonicated in an ultrasonic bath for 10 min at room temperature. 1 mL of the solution was transferred to a 3 mL headspace vial and sealed tightly using a vial crimper. Gas was exchanged by manually removing air inside the vial with a 30 mL syringe and replacing it by injecting C3F8. Three different initial Ir feeding concentrations at 100, 500, and 1000 μg/mL denoted as Ir100, Ir500, and Ir1k were used. Ir500, and Ir1k were prepared similar to Ir100 but with 500 and 1000 μg/mL of Ir, respectively, instead of 100 μg/mL of Ir. Ir–lipid solution was activated by mechanical agitation using a VialMix shaker (Bristol-Myers Squibb Medical Imaging Inc., N. Billerica, MA) for 45 s. To isolate NBs from the heterogeneous bubble population, the bubble solution was centrifuged at 50 rcf for 5 min with the headspace vial inverted, and 200 μL of isolated NB population was withdrawn from the bottom of the vial with a fixed distance of 5 mm using a 21 G needle. A reproducible NB with consistent size can be obtained using this preparation protocol.

In Vitro Characterization of Ir-NBs.

Optical microscopy images of an isolated Ir-NB population were obtained using optical microscopy (OMAX digital compound trinocular LED lab biological microscope) using a 100× optical objective. This NB population and a mixed population of large and small Ir-loaded bubbles were diluted with PBS (1:100, v/v) and imaged under fluorescent microscopy (Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 motorized FL inverted microscope) using a 10× and 20× objective with Texas Red fluorescence filter. The size distribution and concentration of buoyant (bubble) and nonbuoyant (liposome/lipid aggregation) particles were measured using resonant mass measurement (RMM) (Archimedes, Malvern Pananalytical Inc., Westborough, MA, USA).77 A nanosensor with detectable range of 100 nm to 2 μm was precalibrated using NIST traceable 565 nm polystyrene bead standards (ThermoFisher 4010S, Waltham MA, USA). Ir-NBs were diluted 1:1000 with PBS (pH 7.4) before measuring, and a total of 1000 particles were measured for each trial (n = 3). Acoustic properties of Ir-NBs was examined using a clinical US scanner (AplioXG SSA-790A, Toshiba Medical Imaging Systems, Otawara-Shi, Japan). Ir-NBs were diluted in PBS at 1:100 and poured into a tissue-mimicking agarose phantom with a thin channel to make ensure that NBs were in the US field and continuously insonated. This phantom were placed directly over an US transducer (PLT-1204BT) and the nonlinear contrast images were continuously acquired via contrast harmonic imaging. The parameters were set as CHI, 12 MHz, mechanical index 0.1, focus depth of 1.5 cm, 2D gain of 70 dB, and dynamic range of 65 dB at 1 frame per second for 8 min. The data was analyzed using built-in software,29 and the initial signal enhancement and signal decay over time were determined from the recorded data.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity.

To determine cytotoxicity/viability of Ir-NBs, two different cell lines including human ovarian cancer (OVCAR-3) and breast cancer (MCF-7) were used in this study. Cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL in 96-well plate at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere and allowed to grow overnight. Four different sample solutions, including Ir-NBs, free Ir, free Ir + empty NBs, and empty NBs, were added into 96-well plates. The final concentration of Ir and NBs was equally controlled at 10 μg/mL and 1:100 dilution (v/v), respectively. Each well was filled with 400 μL of sample solution and wrapped with sterile transparent film dressing (Tegaderm). We conducted two treatments: (1) cells were immediately exposed to the unfocused US (Ir-NBs+US, free Ir +US, free Ir+empty NBs+US, empty NBs+US) and incubated for 3 h; (2) cells without US exposure were incubated for 3 h (Ir-NBs, free Ir, free Ir+empty NBs, empty NBs). For the group with ultrasound (+US), cells were exposed to an unfocused US transducer (Omnisound 3000 device, Accelerated Care Plus Corp., Reno, NV) with an effective radiating area of 2 cm2 with parameters set as 1 MHz, 1.7 W/cm2, 100% duty cycle, for 1 min. Untreated cells incubated with serum-free RPMI medium only (with US and without US) were used as a control. Following 3 h incubation, cells were washed three times with PBS, replaced with complete media, and further incubated for 72 h. Later, cell viability was determined using a colorimetric WST-1 assay. The cell viability and proliferation can be quantified based on mitochondrial dehydrogenases caused by the cleavage of the tetrazolium salt WST-1. Briefly, cells were incubated with WST-1 (1:10, v/v) for 1 h, and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a TECAN plate reader. The experiments were carried out in triplicate and performed in the dark.

In Vitro Intracellular ROS Detection.

OVCAR-3 and MCF-7 cells (104 cells/well) were seeded into black 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h. Cells were stained with 25 μM of DCFDA solution in PBS at 37 °C for 45 min. After that, cells were washed with PBS and treated with the same treatment groups and methods as previously described in the cytotoxicity section. Untreated nonstained cells were used to determine background fluorescence. Empty NBs and 100 mM of tert-butyl hydrogen peroxide (TBHP) were used as a negative and positive control (ROS inducer), respectively. Following treatment, the relative fluorescence intensity of ROS was immediately read using a TECAN plate reader at the excitation and emission wave-lengths of 485 and 535 nm, respectively. The experiments were carried out in triplicate and performed in the dark.

Confocal Microscopy.

The intracellular ROS imaging of human tumor cells upon treatment with Ir-NBs and US was carried out by confocal fluorescence microscopy. OVCAR-3 and MCF-7 cells were seeded in 6-well cover glass-bottom plates with an ideal thickness of 0.17 mm at the seeding density of 2 × 105 cells/well. RPMI without phenol red was used in this experiment. After 24 h incubation at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were rinsed with PBS and stained with DCFDA for 45 min. The solutions were aspirated and replaced with treatment solutions. Cells were treated with the same treatment groups and methods as previously described in the cytotoxicity section. Then, the confocal microscopy was carried out using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope equipped with the HC PL APO 63×/1.40 oil immersion objective. Imaging was performed sequentially using excitation of 488 nm for DCFDA and 405 nm for Ir-NBs. In both cases, emission was collected from 505 to 550 nm. The experiments were performed in the dark.

Statistical Analysis.

In this study, all experiments were done in triplicate unless otherwise noted, and the results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical analysis was performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the different means between groups were evaluated by the Tukey–Kramer comparison test in Origin. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant unless otherwise noted.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

National Institutes of Health (R01EB028144 and R01EB025741) supported this work and P.N. was supported by the Royal Thai Government, Thailand. We would like to acknowledge use of a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope in the Case Western Reserve University SOM Light Microscopy Imaging Core, with funding support from NIH ORIP S10OD016164 and technical assistance by Richard Lee.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.1c00082.

Size and concentration characterization of Ir-NBs; Nanoparticle characterization via dynamic light scattering; Confocal fluorescence images (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.1c00082

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Pinunta Nittayacharn, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States.

Eric Abenojar, Department of Radiology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States.

Massimo La Deda, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Technologies, University of Calabria, 87036 Rende, Cosenza, Italy; CNR NANOTEC - Institute of Nanotechnology, UOS Cosenza, 87036 Rende, Cosenza, Italy.

Loredana Ricciardi, CNR NANOTEC - Institute of Nanotechnology, UOS Cosenza, 87036 Rende, Cosenza, Italy.

Giuseppe Strangi, CNR NANOTEC - Institute of Nanotechnology, UOS Cosenza, 87036 Rende, Cosenza, Italy; Department of Physics, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States.

Agata A. Exner, Department of Biomedical Engineering and Department of Radiology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Ko CN, Li G, Leung CH, and Ma DL (2019) Dual Function Luminescent Transition Metal Complexes for Cancer Theranostics: The Combination of Diagnosis and Therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev 381, 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Baggaley E, Weinstein JA, and Williams JAG (2012) Lighting the Way to See inside the Live Cell with Luminescent Transition Metal Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev 256, 1762–1785. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Imberti C, Zhang P, Huang H, and Sadler PJ (2020) New Designs for Phototherapeutic Transition Metal Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 59 (1), 61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zhao J, Wu W, Sun J, and Guo S (2013) Triplet Photosensitizers: From Molecular Design to Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 42 (12), 5323–5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zhao Q, Huang H, and Li F (2011) Phosphorescent Heavy-Metal Complexes for Bioimaging. Chem. Soc. Rev 40 (5), 2508–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Shaikh S, Wang Y, Ur Rehman F, Jiang H, and Wang X (2020) Phosphorescent Ir (III) Complexes as Cellular Staining Agents for Biomedical Molecular Imaging. Coord. Chem. Rev 416, 213344. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Castano AP, Demidova TN, and Hamblin MR (2005) Mechanisms in Photodynamic Therapy: Part Two - Cellular Signaling, Cell Metabolism and Modes of Cell Death. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther 2, 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Zamora A, Vigueras G, Rodríguez V, Santana MD, and Ruiz J (2018) Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Luminescent Complexes in Therapy and Phototherapy. Coord. Chem. Rev 360, 34–76. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Huang H, Banerjee S, and Sadler PJ (2018) Recent Advances in the Design of Targeted Iridium(III) Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. ChemBioChem 19 (15), 1574–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).McKenzie LK, Bryant HE, and Weinstein JA (2019) Transition Metal Complexes as Photosensitisers in One- and Two-Photon Photodynamic Therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev 379, 2–29. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Fan W, Huang P, and Chen X (2016) Overcoming the Achilles’ Heel of Photodynamic Therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev 45, 6488–6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).McHale AP, Callan JF, Nomikou N, Fowley C, and Callan B (2016) Sonodynamic Therapy: Concept, Mechanism and Application to Cancer Treatment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 880, 429–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Choi V, Rajora MA, and Zheng G (2020) Activating Drugs with Sound: Mechanisms behind Sonodynamic Therapy and the Role of Nanomedicine. Bioconjugate Chem. 31, 967–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Rengeng L, Qianyu Z, Yuehong L, Zhongzhong P, and Libo L (2017) Sonodynamic Therapy, a Treatment Developing from Photodynamic Therapy. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther 19, 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yumita N, Nishigaki R, Umemura K, and Umemura S. -i. (1989) Hematoporphyrin as a Sensitizer of Cell-damaging Effect of Ultrasound. Jpn. J. Cancer Res 80 (3), 219–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Umemura S. -i, Yumita N, Nishigaki R, and Umemura K (1990) Mechanism of Cell Damage by Ultrasound in Combination with Hematoporphyrin. Jpn. J. Cancer Res 81 (9), 962–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hachimine K, Shibaguchi H, Kuroki M, Yamada H, Kinugasa T, Nakae Y, Asano R, Sakata I, Yamashita Y, Shirakusa T, et al. (2007) Sonodynamic Therapy of Cancer Using a Novel Porphyrin Derivative, DCPH-P-Na(I), Which Is Devoid of Photo-sensitivity. Cancer Sci. 98 (6), 916–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Huang P, Qian X, Chen Y, Yu L, Lin H, Wang L, Zhu Y, and Shi J (2017) Metalloporphyrin-Encapsulated Biodegradable Nanosystems for Highly Efficient Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Guided Sonodynamic Cancer Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139 (3), 1275–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Yumita N, Iwase Y, Nishi K, Komatsu H, Takeda K, Onodera K, Fukai T, Ikeda T, Umemura SI, Okudaira K, et al. (2012) Involvement of Reactive Oxygen Species in Sonodynamically Induced Apoptosis Using a Novel Porphyrin Derivative. Theranostics 2 (9), 880–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Huynh E, Lovell JF, Helfield BL, Jeon M, Kim C, Goertz DE, Wilson BC, and Zheng G (2012) Porphyrin Shell Microbubbles with Intrinsic Ultrasound and Photoacoustic Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc 134 (40), 16464–16467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ma A, Chen H, Cui Y, Luo Z, Liang R, Wu Z, Chen Z, Yin T, Ni J, Zheng M, et al. (2019) Metalloporphyrin Complex-Based Nanosonosensitizers for Deep-Tissue Tumor Theranostics by Noninvasive Sonodynamic Therapy. Small 15 (5), 1804028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Sirsi SR, and Borden MA (2009) Microbubble Compositions, Properties and Biomedical Applications. Bubble Sci., Eng., Technol 1, 3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ibsen S, Schutt CE, and Esener S (2013) Microbubble-Mediated Ultrasound Therapy: A Review of Its Potential in Cancer Treatment. Drug Des., Dev. Ther, 375–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Kogan P, Gessner RC, and Dayton PA (2010) Microbubbles in Imaging: Applications beyond Ultrasound. Bubble Sci., Eng., Technol 2, 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Lee H, Kim H, Han H, Lee M, Lee S, Yoo H, Chang JH, and Kim H (2017) Microbubbles Used for Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound and Theragnosis: A Review of Principles to Applications. Biomedical Engineering Letters. 7, 59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Rychak JJ, and Klibanov AL (2014) Nucleic Acid Delivery with Microbubbles and Ultrasound. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 72, 82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).McDannold N, Arvanitis CD, Vykhodtseva N, and Livingstone MS (2012) Temporary Disruption of the Blood-Brain Barrier by Use of Ultrasound and Microbubbles: Safety and Efficacy Evaluation in Rhesus Macaques. Cancer Res. 72 (14), 3652–3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Cavalli R, Soster M, and Argenziano M (2016) Nanobubbles: A Promising Efficienft Tool for Therapeutic Delivery. Ther. Delivery 7, 117–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Wu H, Rognin NG, Krupka TM, Solorio L, Yoshiara H, Guenette G, Sanders C, Kamiyama N, and Exner AA (2013) Acoustic Characterization and Pharmacokinetic Analyses of New Nanobubble Ultrasound Contrast Agents. Ultrasound Med. Biol 39 (11), 2137–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Zheng R, Yin T, Wang P, Zheng R, Zheng B, Cheng D, Zhang X, and Shuai X-T (2012) Nanobubbles for Enhanced Ultrasound Imaging of Tumors. Int. J. Nanomed 7, 895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Li J, Xi A, Qiao H, and Liu Z (2020) Ultrasound-Mediated Diagnostic Imaging and Advanced Treatment with Multifunctional Micro/Nanobubbles. Cancer Lett. 475, 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Nittayacharn P, Abenojar E, De Leon A, Wegierak D, and Exner AA (2020) Increasing Doxorubicin Loading in Lipid-Shelled Perfluoropropane Nanobubbles via a Simple Deprotonation Strategy. Front. Pharmacol 11, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Nittayacharn P, Yuan H-X, Hernandez C, Bielecki P, Zhou H, and Exner AA (2019) Enhancing Tumor Drug Distribution With Ultrasound-Triggered Nanobubbles. J. Pharm. Sci 108 (9), 3091–3098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Bosca F, Bielecki PA, Exner AA, and Barge A (2018) Porphyrin-Loaded Pluronic Nanobubbles: A New US-Activated Agent for Future Theranostic Applications. Bioconjugate Chem. 29 (2), 234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Perera RH, Wu H, Peiris P, Hernandez C, Burke A, Zhang H, and Exner AA (2017) Improving Performance of Nanoscale Ultrasound Contrast Agents Using N,N-Diethylacrylamide Stabilization. Nanomedicine 13 (1), 59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).de Leon A, Perera R, Hernandez C, Cooley M, Jung O, Jeganathan S, Abenojar E, Fishbein G, Sojahrood AJ, Emerson CC, Stewart PL, Kolios MC, and Exner AA (2019) Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound Imaging by Nature-Inspired Ultrastable Echogenic Nanobubbles. Nanoscale 11 (33), 15647–15658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Abenojar EC, Nittayacharn P, de Leon AC, Perera R, Wang Y, Bederman I, and Exner AA (2019) Effect of Bubble Concentration on the in Vitro and in Vivo Performance of Highly Stable Lipid Shell-Stabilized Micro- and Nanoscale Ultrasound Contrast Agents. Langmuir 35 (31), 10192–10202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Hysi E, Fadhel MN, Wang Y, Sebastian JA, Giles A, Czarnota GJ, Exner AA, and Kolios MC (2020) Photoacoustic Imaging Biomarkers for Monitoring Biophysical Changes during Nanobubble-Mediated Radiation Treatment. Photoacoustics 20, 100201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Perera RH, de Leon A, Wang X, Wang Y, Ramamurthy G, Peiris P, Abenojar E, Basilion JP, and Exner AA (2020) Real Time Ultrasound Molecular Imaging of Prostate Cancer with PSMA-Targeted Nanobubbles. Nanomedicine 28, 102213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Nittayacharn P, Dai K, Leon De A, Therdrattanawong C, and Exner AA (2019) The Effect of Freeze/Thawing on the Physical Properties and Acoustic Performance of Perfluoropropane Nanobubble Suspensions. IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, IUS, 2279–2282. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Ricciardi L, Sancey L, Palermo G, Termine R, De Luca A, Szerb EI, Aiello I, Ghedini M, Strangi G, and La Deda M (2017) Plasmon-Mediated Cancer Phototherapy: The Combined Effect of Thermal and Photodynamic Processes. Nanoscale 9 (48), 19279–19289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Nittayacharn P, De Leon A, Abenojar EC, and Exner AA (2018) The Effect of Lipid Solubilization on the Performance of Doxorubicin-Loaded Nanobubbles. IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, IUS, 1 DOI: 10.1109/ULTSYM.2018.8579716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Ricciardi L, Sancey L, Palermo G, Termine R, De Luca A, Szerb EI, Aiello I, Ghedini M, Strangi G, and La Deda M (2017) Plasmon-Mediated Cancer Phototherapy: The Combined Effect of Thermal and Photodynamic Processes. Nanoscale 9 (48), 19279–19289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Suehiro S, Ohnishi T, Yamashita D, Kohno S, Inoue A, Nishikawa M, Ohue S, Tanaka J, and Kunieda T (2018) Enhancement of Antitumor Activity by Using 5-ALA-Mediated Sonodynamic Therapy to Induce Apoptosis in Malignant Gliomas: Significance of High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound on 5-ALA-SDT in a Mouse Glioma Model. J. Neurosurg 129 (6), 1416–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Zhang J-Z, Saggar JK, Zhou Z-L, and Hu B (2012) Different Effects of Sonoporation on Cell Morphology and Viability. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci 12, 64–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Rosenthal I, Sostaric JZ, and Riesz P (2004) Sonodynamic Therapya Review of the Synergistic Effects of Drugs and Ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem 11, 349–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Logan K, Foglietta F, Nesbitt H, Sheng Y, McKaig T, Kamila S, Gao J, Nomikou N, Callan B, McHale AP, et al. (2019) Targeted Chemo-Sonodynamic Therapy Treatment of Breast Tumours Using Ultrasound Responsive Microbubbles Loaded with Paclitaxel, Doxorubicin and Rose Bengal. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 139, 224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Nesbitt H, Sheng Y, Kamila S, Logan K, Thomas K, Callan B, Taylor MA, Love M, O’Rourke D, Kelly P, et al. (2018) Gemcitabine Loaded Microbubbles for Targeted Chemo-Sonodynamic Therapy of Pancreatic Cancer. J. Controlled Release 279, 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Beguin E, Shrivastava S, Dezhkunov NV, Mchale AP, Callan JF, and Stride E (2019) Direct Evidence of Multibubble Sonoluminescence Using Therapeutic Ultrasound and Microbubbles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11 (22), 19913–19919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Nomikou N, Fowley C, Byrne NM, McCaughan B, McHale AP, and Callan JF (2012) Microbubble-Sonosensitiser Conjugates as Therapeutics in Sonodynamic Therapy. Chem. Commun 48 (67), 8332–8334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Wu H, Rognin NG, Krupka TM, Solorio L, Yoshiara H, Guenette G, Sanders C, Kamiyama N, and Exner AA (2013) Acoustic Characterization and Pharmacokinetic Analyses of New Nanobubble Ultrasound Contrast Agents. Ultrasound Med. Biol 39 (11), 2137–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Ricciardi L, Mastropietro TF, Ghedini M, La Deda M, and Szerb EI (2014) Ionic-Pair Effect on the Phosphorescence of Ionic Iridium(III) Complexes. J. Organomet. Chem 772, 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Zheng S, Puri A, Li J, Jaiswal A, and Adams M (2017) Particle Characterization for a Protein Drug Product Stored in Pre-Filled Syringes Using Micro-Flow Imaging, Archimedes, and Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation. AAPS J. 19 (1), 110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Sojahrood AJ, de Leon A, Lee R, Cooley M, Abenojar E, Kolios MC, and Exner AA High Yield, Shell-Stabilized, Narrow-Sized C3F8 Nanobubbles with Different Shell Properties and Precisely Controllable Response to Acoustic Excitations: Experimental Observations and Numerical Simulations. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Gorce JM, Arditi M, and Schneider M (2000) Influence of Bubble Size Distribution on the Echogenicity of Ultrasound Contrast Agents: A Study of Sonovue(TM). Invest. Radiol 35 (11), 661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Eisenbrey JR, Burstein OM, Kambhampati R, Forsberg F, Liu JB, and Wheatley MA (2010) Development and Optimization of a Doxorubicin Loaded Poly(Lactic Acid) Contrast Agent for Ultrasound Directed Drug Delivery. J. Controlled Release 143 (1), 38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Cochran MC, Eisenbrey J, Ouma RO, Soulen M, and Wheatley MA (2011) Doxorubicin and Paclitaxel Loaded Microbubbles for Ultrasound Triggered Drug Delivery. Int. J. Pharm 414 (1–2), 161–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Jin Q, Kang ST, Chang YC, Zheng H, and Yeh CK (2016) Inertial Cavitation Initiated by Polytetrafluoroethylene Nanoparticles under Pulsed Ultrasound Stimulation. Ultrason. Sonochem 32, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Liu Y, Bai L, Guo K, Jia Y, Zhang K, Liu Q, Wang P, and Wang X (2019) Focused Ultrasound-Augmented Targeting Delivery of Nanosonosensitizers from Homogenous Exosomes for Enhanced Sonodynamic Cancer Therapy. Theranostics 9 (18), 5261–5281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Huang P, Qian X, Chen Y, Yu L, Lin H, Wang L, Zhu Y, and Shi J (2017) Metalloporphyrin-Encapsulated Biodegradable Nanosystems for Highly Efficient Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Guided Sonodynamic Cancer Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139 (3), 1275–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Gorgizadeh M, Azarpira N, Lotfi M, Daneshvar F, Salehi F, and Sattarahmady N (2019) Sonodynamic Cancer Therapy by a Nickel Ferrite/Carbon Nanocomposite on Melanoma Tumor: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther 27, 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Chang N, Qin D, Wu P, Xu S, Wang S, and Wan M (2019) IR780 Loaded Perfluorohexane Nanodroplets for Efficient Sonodynamic Effect Induced by Short-Pulsed Focused Ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem 53, 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Suslick KS (1990) Sonochemistry. Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 247 (4949), 1439–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Umemura S, Yumita N, and Nishigaki R (1993) Enhancement of Ultrasonically Induced Cell Damage by a Gallium-Porphyrin Complex, ATX-70. Jpn. J. Cancer Res 84 (5), 582–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Sato K, Hachine K, and Saito Y (2003) Inception and Dynamics of Traveling-Bubble-Type Cavitation in a Venturi. Proceedings of the ASME/JSME Joint Fluids Engineering Conference 2A, 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- (66).Prosperetti A, Crum LA, and Commander KW Nonlinear Bubble Dynamics, 1987. https://pages.jh.edu/aprospe1/publications/PapersPublished/GasBubbles/ProsperettiCrumCommanderJASA.pdf

- (67).O’BRIEN WD (1986) Biological Effects of Ultrasound: Rationale for the Measurement of Selected Ultrasonic Output Quantities. Echocardiography 3 (3), 165–179. [Google Scholar]

- (68).Tang W, Fan W, Liu Q, Zhang J, and Qin X (2011) The Role of P53 in the Response of Tumor Cells to Sonodynamic Therapy in Vitro. Ultrasonics 51 (7), 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Honda H, Kondo T, Zhao QL, Feril LB, and Kitagawa H (2004) Role of Intracellular Calcium Ions and Reactive Oxygen Species in Apoptosis Induced by Ultrasound. Ultrasound Med. Biol 30 (5), 683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Tachibana K, Uchida T, Ogawa K, Yamashita N, and Tamura K (1999) Induction of Cell-Membrane Porosity by Ultrasound. Lancet 353 (9162), 1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Cheng J, Sun X, Guo S, Cao W, Chen H, Jin Y, Li B, Li Q, Wang H, Wang Z, et al. (2013) Effects of 5-Aminolevulinic Acid-Mediated Sonodynamic Therapy on Macrophages. Int. J. Nanomed 8, 669–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Costley D, Mc Ewan C, Fowley C, McHale AP, Atchison J, Nomikou N, and Callan JF (2015) Treating Cancer with Sonodynamic Therapy: A Review. Int. J. Hyperthermia 31 (2), 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Zhang C, Lai SH, Zeng CC, Tang B, Wan D, Xing DG, and Liu YJ (2016) The Induction of Apoptosis in SGC-7901 Cells through the ROS-Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction Pathway by a Ir(III) Complex. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 21 (8), 1047–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Zhang C, Lai SH, Yang HH, Xing DG, Zeng CC, Tang B, Wan D, and Liu YJ (2017) Photoinduced ROS Regulation of Apoptosis and Mechanism Studies of Iridium(Iii) Complex against SGC-7901 Cells. RSC Adv. 7 (29), 17752–17762. [Google Scholar]

- (75).Cheng J, Sun X, Guo S, Cao W, Chen H, Jin Y, Li B, Li Q, Wang H, Wang Z, et al. (2013) Effects of 5-Aminolevulinic Acid-Mediated Sonodynamic Therapy on Macrophages. Int. J. Nanomed 8, 669–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Liu Y, Bai L, Guo K, Jia Y, Zhang K, Liu Q, Wang P, and Wang X (2019) Focused Ultrasound-Augmented Targeting Delivery of Nanosonosensitizers from Homogenous Exosomes for Enhanced Sonodynamic Cancer Therapy. Theranostics 9 (18), 5261–5281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Hernandez C, Abenojar EC, Hadley J, De Leon AC, Coyne R, Perera R, Gopalakrishnan R, Basilion JP, Kolios MC, and Exner AA (2019) Sink or Float? Characterization of Shell-Stabilized Bulk Nanobubbles Using a Resonant Mass Measurement Technique. Nanoscale 11 (3), 851–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.