Abstract

Study Objectives

The psychomotor vigilance test (PVT), a 10-min one-choice reaction time task with random response-stimulus intervals (RSIs) between 2 and 10 s, is highly sensitive to behavioral alertness deficits due to sleep loss. To investigate what drives the performance deficits, we conducted an in-laboratory total sleep deprivation (TSD) study and compared performance on the PVT to performance on a 10-min high-density PVT (HD-PVT) with increased stimulus density and truncated RSI range between 2 and 5 s. We hypothesized that the HD-PVT would show greater impairments from TSD than the standard PVT.

Methods

n = 86 healthy adults were randomized (2:1 ratio) to 38 h of TSD (n = 56) or corresponding well-rested control (n = 30). The HD-PVT was administered when subjects had been awake for 34 h (TSD group) or 10 h (control group). Performance on the HD-PVT was compared to performance on the standard PVTs administered 1 h earlier and 1 h later.

Results

The HD-PVT yielded approximately 60% more trials than the standard PVT. The HD-PVT had faster mean response times (RTs) and equivalent lapses (RTs > 500 ms) compared to the standard PVT, with no differences between the TSD effects on mean RT and lapses between tasks. Further, the HD-PVT had a dampened time-on-task effect in both the TSD and control conditions.

Conclusions

Contrary to expectation, the HD-PVT did not show greater performance impairment during TSD, indicating that stimulus density and RSI range are not primary drivers of the PVT’s responsiveness to sleep loss.

Keywords: sustained attention, behavioral alertness, fatigue, sleep deprivation, time on task, response-stimulus interval, stimulus density, cognitive performance, neurobehavioral functioning

Statement of Significance.

Based on theoretical perspectives on the PVT’s remarkable sensitivity to sleep loss, we predicted that increasing the task’s stimulus density (i.e. high-density PVT) would be associated with a higher probability of capturing attentional instability, amplification of the time-on-task effect, and enhancement of the RSI effect—and thus even greater detection of behavioral alertness deficits during sleep deprivation. Our empirical findings contradict these predictions and instead suggest that the exertion of top-down compensatory effort during the RSIs to compensate for bottom-up degradation of neuronal processing is a critical mediator of performance impairment on the PVT. Our results help to explain what makes the PVT a gold standard for measuring behavioral alertness deficits due to sleep loss.

Introduction

Since the original invention, first publication [1], and further development [2–5] of the Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) by the research team led by David Dinges, this performance task has become the gold standard measure of behavioral alertness [5] or vigilant attention [6] in research on sleep loss, circadian rhythms, and operational fatigue [5, 7]. The PVT is a one-choice serial reaction time task in which a visual stimulus—typically a rolling millisecond counter—is presented at random response-stimulus intervals (RSIs) ranging from 2 to 10 s in steps of 1 s (or as a continuous range in later versions). Individuals are instructed to respond to the stimulus, by pressing a button or tapping a screen, as quickly as possible without making false starts (i.e. responding prior to the stimulus presentation). After each response, the response time (RT) is displayed for 1 s; then the screen is blank until the next stimulus appears. The PVT was originally administered with custom-built hardware (PVT-192) and was 10 min in duration [1], which entails approximately 80–100 stimuli. The PVT is now widely used in both standard (10-min) and abbreviated (e.g. 3-min or 5-min) durations and is available across a range of platforms, including desktop computers, laptops, tablets, smartphones, and personal digital assistants (e.g. [8–15]). In some versions, an auditory (rather than visual) stimulus can be used [16], although this is less commonly applied.

PVT performance is highly sensitive to [17–18], and considerably compromised by, sleep loss [19], circadian misalignment [20], sleep inertia [21], obstructive sleep apnea [22], and various other sleep-related conditions and challenges (e.g. [23–27]). With no practice effect [28, 29] and little variation among people in aptitude for the task [4], the PVT has been a valuable tool in studies of the temporal dynamics of performance in response to acute total sleep deprivation [3], chronic sleep restriction [28, 30], nap sleep [31, 32], recovery sleep [33], sleep extension [34], circadian rhythmicity [35], stimulant use [36, 37], etc., as well as individual differences therein [38, 39]. The PVT has been used in laboratory and field settings and across many different populations, including police officers, fire fighters, doctors, nurses, emergency medical technicians, truck drivers, sailors, pilots, astronauts, and others (e.g. [40–48]).

The PVT’s exceptional sensitivity makes it a valuable research tool, but it also raises important theoretical questions about neurobehavioral functioning under conditions of sleep loss—that is, what exactly makes PVT performance so reactive to sleep loss, and what does that reveal about what happens in the sleep-deprived brain? Paradoxically, classic vigilance tasks [49, 50] were thought to derive their sensitivity to sleep loss from long task durations (in the order of hours) and long intervals between stimuli (in the order of one to several minutes). The task duration and RSI range of the PVT are substantially shorter, but PVT performance exhibits a robust time-on-task effect (i.e. degradation of performance across the duration of the task; [51]), which interacts strongly with sleep deprivation and circadian rhythmicity and amplifies the task’s reactivity thereto [3, 52]; see Figure 1A. It has also been observed that performance impairment is most prominently seen in responses associated with the shortest of the RSIs [53], particularly during sleep deprivation [54, 55]; see Figure 1B. To this day, the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the time-on-task and RSI effects on the PVT and its overall sensitivity to performance changes in response to sleep loss are topics of investigation and debate.

Figure 1.

Signature effects captured by the PVT. (A) Performance degrades with increasing time on task, which is exacerbated by sleep loss. A 10-min standard PVT was administered every 3 h throughout 38 h of total sleep deprivation (TSD), which lasted from 08:00 until 22:00 the following evening. Mean RT (± SE) from 16 healthy adults is plotted per 1-min interval across the 10-min task duration, showing progressive slowing within each test bout, especially in the later part of the TSD period. Note that placement of the 1-min bins in each test is not to scale on the hours awake axis. Adapted from Fig. 2 in Grant et al. [12]. (B) Performance is worse for shorter response-stimulus intervals (RSIs), which is exacerbated by sleep loss. The percentage of RTs classified as lapses (RT > 500 ms) from 54 healthy adults who completed a 10-min PVT at 10:00 after 3.5 h awake and 24 h later after 27.5 h awake is plotted as a function of RSI sub-groups (with continuous-range RSIs between 2 and 10 s divided into 7 equal intervals on a log scale). Curves redrawn from data provided as part of Fig. 3 in Yang et al. [55]. (C) Extended wakefulness causes a rightward skewing of the RT distribution. The distribution of raw RTs from 9 healthy adults performing the PVT at 01:30 after 16 hours of wakefulness and after 40 hours of wakefulness is plotted. Adapted from Fig. 4.1 in Dinges and Kribbs [2]. (D) Sleep deprivation produces “lapses” evident as the emergence of slow RTs interspersed among fast RTs. Individual RTs for a healthy adult performing a PVT at 20:00 after 12 h awake (top panel) and again after 60 h awake (bottom panel). Gaps indicate false starts, the prevalence of which increases after sleep deprivation as well. Adapted from Fig. 3 in Doran et al. [3].

A hallmark characteristic of the effect of sleep loss on PVT performance, as compared to well-rested baseline, is a pronounced rightward skewing of the RT distribution [2]; see Figure 1C. This phenomenon has also been observed in other RT tasks [56], in particular in the context of time-on-task effects [57] and the effects of sleep deprivation on performance [58] and their interaction [59, 60]. It has been interpreted as “gaps”, blocks”, or “lapses” evident through the emergence of slow RTs in response to stimuli being interspersed among otherwise fast responses that are also still observed, even in severely sleep-deprived individuals [3]; see Figure 1D. Several metrics extracted from PVT data to quantify the degree of performance impairment have focused on capturing this phenomenon, giving rise to the number of “lapses of attention” (traditionally defined as RTs > 500 ms) as one frequently used PVT outcome measure [4]. While other metrics have been developed to capture changes in the RT distribution more fully [61, 62], recognition of the “lapses” phenomenon has led to the idea that vigilant attention waxes and wanes over time scales of seconds and minutes and that frequent sampling is critical to capture this attentional instability [3]. Consequently, the impact of sleep deprivation on PVT performance may be determined at least in part by the density of stimuli.

An early theoretical interpretation posited that lapses are discrete events indicative of alertness being intermittently blocked [58]. However, this “lapse hypothesis” does not account for the previously observed, transiently mitigating effect of high incentives on performance impairment during sleep deprivation [63] or the interacting effects of sleep deprivation and stimulus quality on PVT performance [64]. Dinges and colleagues, noting that performing the PVT while sleep-deprived and across time on task requires compensatory effort, introduced the wake “state instability” hypothesis [3]. It proposes that the effects of sleep deprivation on performance involve escalating wake state instability from elevated homeostatic (and/or circadian) sleep drive resulting in rapid and uncontrolled sleep initiation, which subjects seek to resist using increasingly greater top-down compensatory effort to maintain task performance [65]. In this view, the number of lapses is seen as an index of state instability, whereas the number of false starts (which should be small) is seen as an index of compensatory effort. This way, the PVT is thought to expose the moment-to-moment variability in attention brought about by the interaction of the biological sleep drive with sustained compensatory effort exerted by participants performing the task [3].

Van Dongen and colleagues, building on “local sleep” theory [66], later proposed a bottom-up explanation for attentional instability on the PVT [67]. In this perspective, performance variability on the PVT is attributed to the task’s requirement for repetitive use of the same neuronal pathway(s), which would thereby be driven into a local (i.e. pathway-specific) sleep-like state in a use-dependent manner as previously demonstrated in a rodent model [68]. Consistent with this notion, a study of neurosurgical patients in which local neuronal activity was recorded through intracranial electrodes while they were performing a face/non-face categorization vigilance task found that performance lapses on the task were preceded by sleep-like changes in local field potentials [69]. As postulated [52], local sleep theory predicts that the greater the use (through extended wakefulness, longer task duration, and/or higher stimulus density), the greater the degradation of neuronal processing, and thus the greater the performance impairment on the PVT [62]. Regardless of whether or not the state instability hypothesis or the local sleep explanation will ultimately hold up to scientific scrutiny [6], from all the empirical and theoretical evidence discussed thus far it is evident that influential factors in the impact of sleep loss on PVT performance should include at least the following:

Task duration—a longer task duration should be associated with extended neuronal use and a more pronounced time-on-task effect, and therefore should contribute to performance impairment on the PVT.

Stimulus density—a greater number of stimuli per minute of task duration should increase the probability of capturing attentional instability, and therefore should contribute to task sensitivity; it may also be associated with more intense neuronal use, thereby amplify the time-on-task effect, and thus further contribute to impairment captured by the PVT.

Response-stimulus intervals—the effect of sleep deprivation is most noticeable for shorter RSIs, and thus restricting the range of RSIs to the shorter RSIs should intensify performance impairment on the PVT.

Basner and colleagues [10, 12] leveraged these factors to reduce the duration of the PVT while maintaining relatively high sensitivity to sleep loss. Specifically, they showed that an abbreviated version of the PVT with a 70% decrease in task duration (down to 3 min), a near-doubling of the stimulus density, and a restricted RSI range (from 2 to 5 s only) was associated with a disproportionately modest reduction in statistical effect sizes during total and partial sleep deprivation experiments, as compared to the standard (i.e. original) 10-min PVT. The authors had expected even better sensitivity for the brief version of the PVT, however, and suggested that the use of a different device for the 3-min high-density PVT than for the standard 10-min PVT in their study alerted subjects of the shorter task duration. As such, they potentially could more easily exert compensatory effort to maintain performance even when sleep-deprived [10]. Thus, even though the shorter RSIs and consequently increased stimulus density allowed for a shorter task duration while maintaining reasonably high sensitivity to sleep loss, whether stimulus density would prove to be a key driver of the impact of sleep loss on PVT performance if task duration and other task characteristics were held constant remains to be determined.

Here, in a controlled laboratory study, we juxtaposed the effects of sleep deprivation on a standard desktop PVT with a high stimulus density version, while keeping the task duration fixed at 10 min and all other hardware and software specifications the same. We predicted that after sleep deprivation, relative to baseline, the high-density PVT (HD-PVT) would:

Capture more attentional instability;

Exhibit a steeper time-on-task effect;

Bring about the enhanced sleep deprivation effect associated with shorter RSIs;

and compared to the standard PVT should therefore be unequivocally more sensitive to sleep loss, operationally defined as showing a higher level of performance impairment. Our objective was to test this prediction so as to gain deeper insights into the PVT’s exceptional sensitivity to sleep loss and its neurobehavioral underpinnings.

Methods

Subjects

n = 86 healthy, adult subjects (39 males, 47 females) between the ages of 21 y and 38 y (mean age ± SD: 26.6 ± 5.2 y) completed a 4-day/3-night, in-laboratory study. They were randomly assigned with a 2:1 probability ratio to a total sleep deprivation (TSD) condition (n = 56) or a well-rested control condition (n = 30). In the TSD condition, the mean age ± SD was 25.9 ± 5.3 y, with 24 males and 32 females. In the control condition, the mean age was 27.9 ± 4.9 y, with 15 males and 15 females.

Subjects were screened through a telephone interview, two in-laboratory screenings, an at-home week of sleep monitoring with actigraphy and a sleep diary, and baseline polysomnography. All were found to be physically and psychologically healthy, with no medical or drug treatment (except oral contraceptives) and no current drug or alcohol use (verified with an alcohol breathalyzer and urine drug screen both at screening and at the start of the laboratory study). Subjects had no history of drug or alcohol abuse in the past year, and no history of methamphetamine abuse; were not a current smoker; had no history of moderate to severe brain injury; had no present or presently clinically relevant history of psychiatric illness; were not pregnant; reported no previous adverse reaction to sleep deprivation; had no history of a learning disability; and were not vision impaired (unless corrected to normal). They had no sleep or circadian disorders; reported good habitual sleep, between 6 and 10 h in duration; had regular bedtimes, habitually getting up between 06:00 and 09:00; did not travel across time-zones within one month of entering the study; and did not engage in shift work within 3 months of entering the study.

Experimental design

On the first day of the study, subjects entered the laboratory at 15:30, were oriented to the laboratory environment, and then were trained on a number of cognitive tests, including the standard PVT. During this training, members of the research team worked one-on-one with each of the subjects at their testing station in their individual room to instruct them on the tasks and clarify the demand characteristics. This included general instructions for testing (e.g. maintain good and stable posture, maintain attention without fidgeting, etc.) and instructions for completing specific tests (e.g. whether to respond using the keyboard/mouse, etc.). For the PVT, the researcher indicated that the subject should press the designated button on a response box as fast as possible whenever the rolling millisecond counter stimulus appeared. Specific instructions were provided to emphasize that subjects should try their very hardest to respond as fast as they could, even if they experienced this to be difficult to sustain (i.e. avoid errors of omission), and to avoid making false starts (i.e. avoid errors of commission). Subjects were asked to give their best performance every time, to use determination and focus, and to aim to have consistently fast RTs. The researcher then positioned themself behind the subject and observed the performance throughout the entire 10-min test, providing feedback as needed so that the subject understood the expectations and could produce fast and relatively consistent RTs at baseline.

At the end of the first day, subjects had a 10-h sleep opportunity from 22:00 to 08:00. At 18:00 on day 2, subjects were told whether they had been assigned to the TSD condition or the control condition. Subjects in the TSD condition were kept awake from 08:00 on day 2 until 22:00 on day 3 (38 h of TSD), while subjects in the control condition had another 10-h sleep opportunity on the second night (22:00–08:00). All subjects had a final 10-h sleep opportunity from 22:00 until 08:00 on the final night; they left the laboratory around 11:30 on day 4.

Sleep periods were recorded polysomnographically. During scheduled wakefulness, various performance tasks were administered, and meals and snacks were served every 4 h (including during the night when subjects in the TSD condition were awake). Subjects were in their own individual room while sleeping and during performance testing. When not eating, sleeping, or testing, they were only allowed non-vigorous activities such as reading or chatting with other participants or research staff. No visitors and no contact with people outside the laboratory were allowed. Trained research assistants monitored the subjects’ behavior throughout the study.

During the scheduled wake periods, a computerized test battery was administered at approximately 2-h intervals. The test battery, which took approximately 25 min to complete, included the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS; [70]), a performance prediction scale, the standard PVT, a 9-point computerized variation on a mood visual analog scale [38], the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; [71]), another KSS, a continuous performance matching task [72], and a computerized digit symbol substitution test (4-min standard version; [73]). The HD-PVT was administered once during the study, as a standalone test at 18:00 on day 3, when subjects in the control condition had been awake for 10 h and those in the TSD condition had been awake for 34 h.

For the present purposes, only the HD-PVT at 18:00 and the surrounding standard PVTs at 17:00 and 19:00 on day 3 were analyzed. To avoid carry-over effects, there was a break of more than 30 min between the standard PVTs and the HD-PVT; see Figure 2. The standard PVT and the HD-PVT were administered on the same desktop computer using the same base software and same stimulus presentation. Responses were made with a custom-made response box, positioned flat on the desk in front of the subject, and calibrated to record RTs with a precision standard deviation of no more than 10 ms, as recommended by Basner and colleagues [74]. The tasks were administered while subjects were seated at a computer in their individual bedrooms, with continuous monitoring by the research team from a separate observation room via camera and microphone. Both the standard PVT and the HD-PVT tasks were 10 min in duration. Any impact of task novelty from the single administration of the HD-PVT should be mitigated by these experimental and test platform standardizations.

Figure 2.

Testing timeline, task specifications, and descriptive statistics.

While the standard PVT had an RSI range from 2 to 10 s (in steps of 1 s) and averaged 95 trials per test bout, the HD-PVT had an RSI range from 2 to 5 s (in steps of 1 s) and averaged 157 trials per test bout. The probability of each RSI occurring was evenly distributed within each test version, with approximately 11.1% of trials having each RSI value (2 to 10 s) on the standard PVT and approximately 25% of trials having each RSI value (2 to 5 s) on the HD-PVT. Other than the RSI range, the two PVT versions were identical. Thus, the modified RSI range and resultant difference in stimulus density were expected to drive any differences in results between the task versions.

Statistical analyses

To verify the PVT manipulation (standard versus high-density version), the number of trials in each test bout (17:00 PVT, 18:00 HD-PVT, and 19:00 PVT) was compared using a mixed-effects analysis of variance (ANOVA) with fixed effects for condition (TSD, control), bout (17:00, 18:00, 19:00), and their interaction. To investigate the overall effect of TSD on the different versions of the PVT, the mean RT, number of lapses (RTs > 500 ms), mean RT of lapses, mean percent of responses that were lapses, and number of false starts for each test bout were analyzed using mixed-effects ANOVA with fixed effects for condition, bout, and their interaction. Additionally, as part of this analysis, the standard PVT and the HD-PVT were compared head-to-head through planned contrasts, both with regard to the mean outcome (for mean RT, number of lapses, mean RT of lapses, percent lapses, and false starts) between tasks and with regard to the TSD effect (difference Δ between the TSD and control conditions) within and between tasks. To investigate the time-on-task effect, the mean RT per 1-min bin in each test bout was analyzed for the two conditions separately using mixed-effects ANOVA with fixed effects for bout, bin (1–10), and their interaction. The magnitude of the time-on-task effect, quantified as the difference in mean RT from the first minute (bin 1) to the last minute (bin 10) of the task, was compared between tasks by means of a planned contrast. Lastly, to investigate the RSI effect, the mean RT for each test bout was analyzed for the two conditions separately using mixed-effects ANOVA with fixed effects for bout, RSI (using only the RSIs in common between the tests: 2–5 s), and their interaction. The magnitude of the RSI effect, quantified as the difference in mean RT from trials with RSIs of 2 and 5 s, was compared between tasks by means of a planned contrast. All analyses included a random effect over subjects on the intercept. The type I error threshold was set at α = 0.05; significance levels between 0.05 and 0.10 are reported as trends.

Results

Figure 2 shows specifications and descriptive statistics for the three test bouts of interest (17:00 PVT, 18:00 HD-PVT, and 19:00 PVT). The difference in the RSI range between the two PVT versions caused a more than 60% increase in the number of trials in the HD-PVT compared to the standard PVT (main effect of bout: F2,168 = 9423.5, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.990), confirming that the HD-PVT did indeed have high stimulus density as intended; see Figure 2. TSD caused no change to the number of trials (main effect of condition: F1,168 = 0.7, p = 0.41, ηp2 = 0.004), with a trend for the condition by bout interaction: (F2,168 = 2.4, p = 0.097, ηp2 = 0.027).

As expected, the mean RT was significantly slower in the TSD condition than in the control condition (main effect of condition: F1,168 = 10.7, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.060). Surprisingly, in both conditions the HD-PVT exhibited faster mean RT than the standard PVT (main effect of bout: F2,168 = 15.1, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.152), with no differential effect of TSD on the two task versions (condition by bout interaction: F2,168 = 1.6, p = 0.21, ηp2 = 0.018); see Figure 3A (top left). Head-to-head comparison of the two task versions across both the sleep deprivation and control conditions through planned contrast revealed that the mean difference (± SE) was –34.3 ± 6.6 ms (planned contrast: F1,168 = 27.3, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.140), with a faster mean RT on the HD-PVT (mean ± SE: 277.8 ± 11.6 ms) than on the standard PVT (mean ± SE: 312.1 ± 11.0 ms). There were significant effects of TSD on the HD-PVT (ΔRT mean ± SE: 61.5 ± 23.2 ms; F1,168 = 7.0, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.040) and on the standard PVT (ΔRT mean ± SE: 74.7 ± 21.9 ms; F1,168 = 11.6, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.064), but no difference between the TSD effects on the two tasks (F1,168 = 1.0, p = 0.32, ηp2 = 0.006). Thus, despite arguably being associated with more intense neuronal use due to the higher stimulus density, the HD-PVT exhibited no greater performance changes in response to sleep loss than the standard PVT.

Figure 3.

(A) Mean RT, (B) number of lapses, (C) percent of lapses, and (D) false starts. Data shown are mean ± SE on the standard PVT (open circles) and the HD-PVT (closed circles), by condition, as a function of measurement time. Data from control subjects are shown in blue and from TSD subjects in red.

Again as expected, there were more lapses on the PVT in the TSD condition than in the control condition (main effect of condition: F1,168 = 20.2, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.108). Counter to expectation, however, there was no significant difference between the two task versions regardless of condition (main effect of bout: F2,168 = 0.9, p = 0.42, ηp2 = 0.010; condition by bout interaction: F2,168 = 0.6, p = 0.58, ηp2 = 0.007); see Figure 3B (top right). Head-to-head comparison of the two task versions across both the sleep deprivation and control conditions through planned contrast also showed no significant difference (F1,168 = 0.2, p = 0.62, ηp2 = 0.001), with a similar number of lapses on the HD-PVT (mean ± SE: 4.2 ± 0.7 lapses) and on the standard PVT (mean ± SE: 4.0 ± 0.7 lapses). There were significant effects of TSD on the HD-PVT (Δlapses mean ± SE: 6.5 ± 1.4 lapses; F1,168 = 20.4, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.108) and on the standard PVT (Δlapses mean ± SE: 5.6 ± 1.3 lapses; F1,168 = 17.6, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.095), but no difference between the TSD effects on the two tasks (F1,168 = 0.9, p = 0.34, ηp2 = 0.006). Further, an analysis of mean RT for lapses only revealed no significant effects for condition (F1,120 = 2.29, p = 0.13), bout (F2,120 = 0.88, p = 0.42), or condition by bout interaction (F2,120 = 0.05, p = 0.95). That is to say, despite its higher sampling frequency, the HD-PVT did not capture more lapses of attention than the standard PVT, nor were mean lapse RTs in the HD-PVT any longer than in the standard PVT.

Repeating the lapse analysis with the percent of responses that were lapses instead of the raw number of lapses similarly revealed a larger percent of lapses in the TSD condition than in the control condition (main effect of condition: F1,168 = 20.1, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.107). Unlike the raw lapse analysis, percent lapses also showed a significant difference between the two task versions (main effect of bout: F2,168 = 7.8, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.085; condition by bout interaction: F2,168 = 3.0, p = 0.052, ηp2 = 0.034); see Figure 3C (bottom right). Head-to-head comparison of the two task versions across both the sleep deprivation and control conditions through planned contrast showed a significant difference (F1,168 = 13.4, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.074), with a smaller percent of responses that were lapses on the HD-PVT (mean ± SE: 3.0% ± 0.7%) than on the standard PVT (mean ± SE: 4.4% ± 0.7%). While there were significant effects of TSD on the HD-PVT (Δpercent lapses mean ± SE: 4.4% ± 1.4%; F1,168 = 10.4, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.058) and on the standard PVT (Δpercent lapses mean ± SE: 6.3% ± 1.3%; F1,168 = 23.8, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.124), there was a notable difference between the TSD effects on the two tasks (F1,168 = 5.8, p = 0.017, ηp2 = 0.033). Notwithstanding the increased sampling frequency, the HD-PVT displayed a lower percent of responses that were lapses than the standard PVT.

There was a trend for more false starts on the PVT in the TSD condition compared to the control condition (main effect of condition: F1,168 = 2.7, p = 0.10, ηp2 = 0.016). There were also more false starts in the HD-PVT than in the standard PVT (main effect of bout: F2,168 = 50.1, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.374), but no differential effect of TSD on the two task versions (condition by bout interaction: F2,168 = 1.4, p = 0.24, ηp2 = 0.017); see Figure 3D (bottom left). Head-to-head comparison of the two task versions across both the sleep deprivation and control conditions through planned contrast revealed that the mean difference (± SE) was 2.9 ± 0.3 false starts (planned contrast: F1,168 = 99.2, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.371), with more false starts on the HD-PVT (mean ± SE: 4.4 ± 0.3 false starts) than on the standard PVT (mean ± SE: 1.5 ± 0.3 false starts). There was a significant effect of TSD on the HD-PVT (Δfalse starts mean ± SE: 1.6 ± 0.7 false starts; F1,168 = 5.3, p = 0.022, ηp2 = 0.031), but not on the standard PVT (Δfalse starts mean ± SE: 0.6 ± 0.6 false starts; F1,168 = 1.0, p = 0.33, ηp2 = 0.006), and a trend of a difference between the TSD effects on the HD-PVT and the standard PVT (F1,168 = 2.9, p = 0.092, ηp2 = 0.017). While the difference in false starts between the two task versions may simply be a consequence of having more stimuli to respond to on the HD-PVT, 98% of HD-PVT bouts and in 99% of standard PVT bouts had fewer than 10% of responses as false starts, which is comparable to previously reported false start rates on the standard PVT during TSD [3].1

There was a significant time-on-task effect in the TSD condition (main effect of bin: F9,1594 = 15.7, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.081); see Figure 4. Overall, mean RT per bin was lower in the HD-PVT than in the standard PVT (main effect of bout: F2,1594 = 21.2, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.026), but there was no significant difference in the manifestation of the time-on-task effect between the two task versions in the TSD condition (bout by bin interaction: F18,1594 = 0.6, p = 0.91, ηp2 = 0.007). Still, the magnitude of the time-on-task effect, quantified as the difference in mean RT from the first to the last minute of the task, was trending toward smaller (planned contrast: F1,1594 = 3.0, p = 0.083, ηp2 = 0.002) for the HD-PVT (mean ± SE: 51.7 ± 26.0 ms; F1,1594 = 4.0, p = 0.047, ηp2 = 0.002) than for the standard PVT (mean ± SE: 106.8 ± 18.3 ms; F1,1594 = 34.1, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.021).

Figure 4.

Time-on-task effect displayed as mean RT per 1-min bin on the standard PVT and the HD-PVT. Data shown are mean ± SE by condition as a function of measurement time.

There was also a significant time-on-task effect in the control condition (main effect of bin: F9,841 = 6.0, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.060), albeit much more modest in magnitude; see Figure 4. Overall, mean RT per bin was again lower in the HD-PVT than in the standard PVT (main effect of bout: F2,841 = 122.7, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.226), with a significant difference in the manifestation of the time-on-task effect between task versions (bout by bin interaction: F18,841 = 1.8, p = 0.018, ηp2 = 0.038). The time-on-task effect was smaller (planned contrast: F1,841 = 2.4, p = 0.13, ηp2 = 0.003) and essentially eliminated on the control condition for the HD-PVT (mean ± SE: 5.2 ± 6.4 ms; F1,841 = 0.7, p = 0.42, ηp2 < 0.001) as compared to its already modest magnitude on the standard PVT (mean ± SE: 17.2 ± 4.5 ms; F1,841 = 14.43, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.017). Thus, contrary to expectation, the higher stimulus density of the HD-PVT did not amplify the time-on-task effect, but significantly dampened it in both the TSD and control conditions.

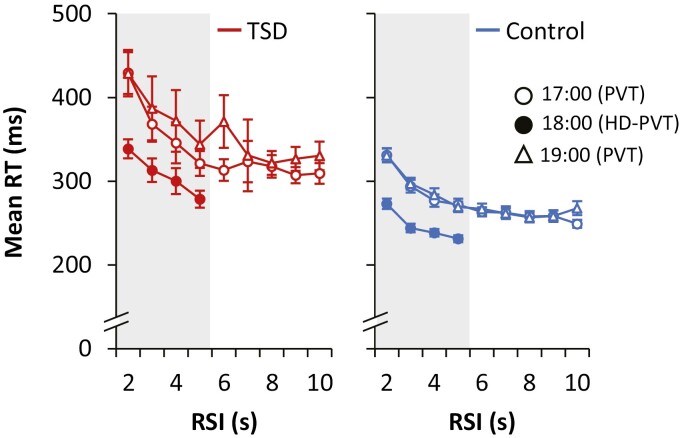

There was a significant RSI effect in the TSD condition (main effect of RSI: F3,605 = 13.4, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.062); see Figure 5 (left). Overall, the mean RT at each RSI from 2 to 5 s (the RSI range both task versions had in common) was faster in the HD-PVT than in the standard PVT (main effect of bout: F2,605 = 25.0, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.076), but there was no other difference in the manifestation of the RSI effect between the two task versions in the TSD condition (bout by RSI interaction: F6,605 = 0.5, p = 0.84, ηp2 = 0.005). The magnitude of the RSI effect, quantified as the difference in mean RT between the RSIs of 2 and 5 s, was not significantly different (planned contrast: F1,605 = 1.6, p = 0.20, ηp2 = 0.003) between the HD-PVT (mean ± SE: 60.2 ± 24.4 ms; F1,605 = 6.07, p = 0.014, ηp2 = 0.010) and the standard PVT (mean ± SE: 98.5 ± 17.3 ms; F1,605 = 32.6, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.051).

Figure 5.

Response-stimulus interval (RSI) effect displayed as mean RT for each RSI on the standard PVT and the HD-PVT. Data shown are mean ± SE per RSI duration in the TSD condition (left) and the control condition (right) on the standard PVT at 17:00 (open circles), the HD-PVT at 18:00 (filled circles), and the standard PVT at 19:00 (open triangles). Note that although the figure shows all RSIs for each test (i.e. 2–10 s for the standard PVT and 2–5 s for the HD-PVT), the analyses of the RSI effect included only RSIs common between the two task versions, as indicated by the gray rectangles (i.e. 2–5 s).

There was also a significant RSI effect in the control condition (main effect of RSI: F3,319 = 102.8, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.492); see Figure 5 (right). Overall, the mean RT at each RSI from 2 to 5 s was faster in the HD-PVT than in the standard PVT (main effect of bout: F2,319 = 185.0, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.537), with no significant difference in the manifestation of the RSI effect between task versions (bout by RSI interaction: F6,319 = 1.8, p = 0.10, ηp2 = 0.032). The magnitude of the RSI effect was significantly smaller (planned contrast: F1,319 = 7.1, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.022) for the HD-PVT (mean ± SE: 41.7 ± 5.7 ms; F1,605 = 52.9, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.142) than for the standard PVT (mean ± SE: 60.3 ± 4.1 ms; F1,605 = 221.7, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.410).

Discussion

In this controlled laboratory study with a total sleep deprivation (TSD) condition and a corresponding control condition, we made within-subjects comparisons of the effects of sleep deprivation on two versions of the PVT: one being the standard PVT [1, 5] and one with a higher stimulus density (HD-PVT) implemented specifically for this study. Administration of the HD-PVT was flanked by administration of the standard PVT within a 2-h timeframe (Figure 2), eliminating sleep homeostatic (time awake) and circadian (time of day) effects as potential confounds; and with 86 carefully screened, healthy subjects, our statistical power was high. Accordingly, both the standard PVT and the HD-PVT showed significant performance impairment due to TSD, including slower mean RT, more lapses, and increased time-on-task effect as compared to the control condition (Figures 3 and 4).

However, the effects of TSD on the two task versions were not identical. As described above, we had a priori predicted that the greater stimulus density and truncated RSI range of the HD-PVT would result in increased performance impairment in response to sleep loss compared to the standard PVT, given the fixed 10-min task duration and all other task characteristics being the same. Yet, that is clearly not what the data showed. Contrary to expectation, there were multiple indications that performance on the HD-PVT is not more, and in some respects is even less, impaired due to TSD than on the standard PVT. This includes faster mean RTs and an equivalent number of lapses on the HD-PVT, with no differential impact of TSD relative to the standard PVT—except when considering the percent of responses that were lapses, for which the HD-PVT showed a relatively dampened response to TSD.

The faster mean RTs are by themselves unexpected, as the more restricted, lower RSI range of the HD-PVT would have been anticipated to emphasize the RSI effect and thus increase mean RT. That said, the overall faster RTs on the HD-PVT could have artificially reduced the number of lapses, as greater skewing of the RT distribution would be needed for the tail of the RT distribution to cross the conventional 500 ms lapse threshold. Indeed, it has been pointed out that an increase in sensitivity could be achieved by lowering the lapse threshold [10, 12], which would also make effective use of the greater number of trials in the HD-PVT. The increase in sensitivity from such an adaptation would however be strictly statistical in nature (i.e. pertaining to effect size only). Note also that responses on the HD-PVT included more false starts than on the standard PVT, but false starts remained rare and should have little relevance for understanding the differential sensitivity of the two task versions.

Surprisingly, the magnitude of the time-on-task effect—a hallmark response of PVT performance during TSD—was reduced on the HD-PVT compared to the standard PVT. The dampening of the time-on-task effect was observed in the TSD condition as well as the control condition, indicating that it is at least partially characteristic of the HD-PVT per se and not solely associated with the effect of TSD. In every case, the differences between the two tasks in the magnitude of the response to TSD were associated with commensurate differences in the statistical effect size (ηp2), underlining that the HD-PVT is not more sensitive to sleep loss than the standard PVT, but rather the opposite. Thus, our prediction that the greater stimulus density and reduced RSI range of the HD-PVT would render this task version more responsive to sleep loss was incorrect. It follows that by itself, stimulus density cannot be the sole or main driver of the impact of sleep loss on PVT performance.

This finding has important theoretical implications. Firstly, as evidenced by the equivalent mean number of lapses per bout and the smaller fraction of trials observed as lapses during TSD, the increased stimulus density of the HD-PVT did not result in greater detection of lapses. This is congruent with David Dinges’ assertion that lapses are not a discrete phenomenon, but rather a reflection of a more gradual, continuous waxing and waning of attention indicative of wake state instability [3], as has also been recognized in more recent PVT research [75]. As such, enhancing the sampling frequency by increasing the stimulus density does not meaningfully improve the PVT’s effectiveness of capturing lapses of attention during task performance.

Secondly, our results do not support the ideas that the increased stimulus load of the HD-PVT is associated with more workload [10] or greater neuronal use [52] leading to greater performance impairment and amplified time-on-task and RSI effects. It would seem that some other facet of the HD-PVT must in fact provide some relief from these challenges of performing the task when sleep-deprived. A bottom-up perspective on performance impairment from sleep loss [67] does not, by itself, offer any clues as to what that facet might be.

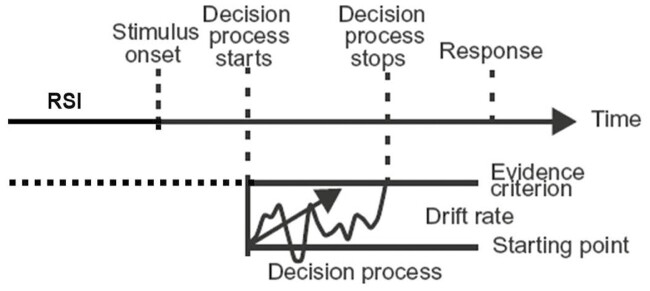

Computational cognitive modeling accounts of the effects of sleep deprivation on the PVT [75, 76] may offer a further insight. Specifically, the effects of TSD on performance of the standard PVT have been described with a one-choice diffusion decision model [75]; see Figure 6. In this computational model, after encoding of the stimulus, a decision process takes place that involves accumulation of evidence through neuronal processing until an evidence criterion is met, upon which a response is made. Stimulus encoding and motor responses are relatively unaffected by sleep loss [77, 78], leaving the decision process as the model component of interest. This decision process can be described as a random walk with a drift rate that varies naturally across trials and is the main driver of the RT distributions produced when subjects perform the task. Consistent with the idea of bottom-up degradation of neural processing [67], the primary effect of TSD was an increase in the mean drift rate [75], which is associated with the characteristic skewing of the RT distribution and the manifestation of state instability (Figure 1C and D).

Figure 6.

Illustration of the one-choice diffusion decision model for the PVT. After presentation of a stimulus and subsequent stimulus encoding, a decision process takes place during which evidence is accumulated through neuronal processing resembling a random walk with a certain drift rate. When the accumulated evidence reaches an evidence criterion, the decision process stops and a response is made. While performing the PVT, the evidence criterion must be set in advance of the stimulus onset and maintained throughout the RSI, which in the face of sleep deprivation may require sustained effort. Figure adapted from Ratcliff and Van Dongen [75].

In this account of the PVT, the evidence criterion—which reflects the demand characteristics of the task and represents the balance between trying one’s hardest to respond and not making any false starts (i.e. between avoiding errors of omission and avoiding errors of commission; [3])—was essentially unchanged by TSD [75]. However, in a go/no-go variant of the PVT, which required either responding or withholding a response based on which of two different stimuli appeared after a variable RSI from 2 to 10 s, subjects traded speed for accuracy (i.e. avoiding false starts) when sleep deprived [79]. In the diffusion decision model, this corresponds with subjects raising the evidence criterion, which is under behavioral control [80], and doing so reduces sensitivity to sleep loss [79].

For the present study, the demand characteristics associated with both the standard PVT and the HD-PVT emphasized response speed and urged subjects to apply compensatory effort to try to maintain optimal performance in the face of sleep deprivation. This was reinforced during training on the standard PVT at the beginning of the laboratory study and via continuous behavioral monitoring throughout the study. Furthermore, the PVT and HD-PVT provided performance feedback by displaying the RT for 1 s immediately after each trial, which further emphasized the importance of compensatory effort to maintain good performance [81]. Effectively, subjects were driven to exert sustained effort during the variable durations of the RSIs to maintain a tight evidence criterion, even when sleep deprivation—and the associated wake state instability and hypothesized bottom-up degradation of neuronal processing due to local sleep—made it difficult to do so. It stands to reason that this exertion of sustained effort to maintain a tight evidence criterion throughout the RSIs would have come at a performance cost, could give rise to the increased time-on-task effect, and may in fact be a central aspect of what makes the PVT sensitive to sleep loss. Indeed, as Dinges and colleagues pointed out [3], the increasing top-down compensatory effort that subjects must make to resist the escalating wake state instability from elevated homeostatic (and/or circadian) sleep drive during TSD appears to be pivotal in understanding the impact of TSD on PVT performance.

Previously published work on the one-choice diffusion decision model of the PVT [75] has not explicitly addressed this aspect of the PVT. It has also not provided an explanation for the time-on-task effect and its interaction with TSD (Figure 1A). The present results from a head-to-head comparison between the standard PVT and the HD-PVT may help to fill this gap. That is, if exerting compensatory effort to maintain a tight evidence criterion throughout the RSIs is key to the impact of sleep loss on PVT performance, then increasing the stimulus density and making the RSIs shorter (while holding task duration constant) would reduce the requirement to sustain such effort through long RSIs, which should lessen the time-on-task effect and its interaction with TSD and thereby the task’s overall performance responsiveness to sleep loss—as indeed we did observe for the HD-PVT (Figures 3 and 4, respectively).

Thus, our current, empirical results support previous speculation that PVT performance relies on a combination of bottom-up and top-down attentional mechanisms [82]. That is, although the sleep loss-induced degradation of cognitive processing for stimulus detection and response is principally a bottom-up problem, maintaining good performance to meet the task demands requires top-down attentional control. The latter is not only essential for task compliance, but may also be where the perceived cognitive demand comes from [83]. This sheds new light on why subjective sleepiness is increased right after performing the PVT [84] and why it is so hard to perform the task when sleep-deprived. Follow-up research in older populations with potentially differential, age-related changes in bottom-up versus top-down attentional functioning [85] could provide helpful data to further evaluate this explanation. Furthermore, we speculate that other performance tasks with RSIs of unpredictable duration, if they require rapid responses (in order to be as fast as possible or to meet short response deadlines), would be similarly impacted by sleep loss.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and students at the Sleep and Performance Research Center at Washington State University for their help conducting this study. We are grateful to Prof. David Dinges for his mentorship, support, and scientific rigor, as well as his many contributions to the field of sleep science on which we build in our research. His esteemed career is a source of inspiration to keep challenging ourselves and continuing to move the science forward.

Submitted for inclusion in the special issue, Festschrift for David Dinges

This paper is part of the David F. Dinges Festschrift Collection. This collection is sponsored by Pulsar Informatics and the Department of Psychiatry in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

One subject in the TSD condition had 23% false starts on the 17:00 standard PVT and 13% on the 18:00 HD-PVT (and 9% on the 19:00 standard PVT). One TSD subject had 11% false starts on the 19:00 standard PVT. One control condition subject had 12% false starts on the HD-PVT and another control condition subject had 11% false starts on the HD-PVT.

Contributor Information

Kimberly A Honn, Sleep and Performance Research Center and Department of Translational Medicine and Physiology, Washington State University, Spokane, WA, USA.

Hans P A Van Dongen, Sleep and Performance Research Center and Department of Translational Medicine and Physiology, Washington State University, Spokane, WA, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, through the Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program under Award No. W81XWH-16-1-0319 and through the Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program Expansion Award under Award No. W81XWH-20-1-0442. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

Upon reasonable request to K.A.H., the deidentified data can be shared with researchers.

References

- 1. Dinges DF, et al. Microcomputer analyses of performance on a portable, simple visual RT task during sustained operations. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 1985;17(6):652–655. doi: 10.3758/bf03200977 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dinges DF, et al. Performing while sleepy: effects of experimentally-induced sleepiness. In: Monk TH, ed. Sleep, Sleepiness and Performance. New York, NY: Wiley; 1991:97–128. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doran SM, et al. Sustained attention performance during sleep deprivation: evidence of state instability. Arch Ital Biol. 2001;139(3):253–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dorrian J, et al. Psychomotor vigilance performance: neurocognitive assay sensitive to sleep loss. In: Kusida CA, ed. Sleep Deprivation: Clinical Issues, Pharmacology, and Sleep Loss Effects. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 2005:39–70. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lim J, et al. Sleep deprivation and vigilant attention. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:305–322. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hudson AN, et al. Sleep deprivation, vigilant attention, and brain function: a review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45(1):21–30. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0432-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Satterfield BC, et al. Occupational fatigue, underlying sleep and circadian mechanisms, and approaches to fatigue risk management. Fatigue. 2013;1(3):118–136. doi: 10.1080/21641846.2013.798923 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thorne DR, et al. The Walter Reed palm-held psychomotor vigilance test. Behav Res Methods. 2005;37(1):111–118. doi: 10.3758/bf03206404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lamond N, et al. The sensitivity of a palm-based psychomotor vigilance task to severe sleep loss. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(1):347–352. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.1.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Basner M, et al. Validity and sensitivity of a brief Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT-B) to total and partial sleep deprivation. Acta Astronaut. 2011;69(11–12):949–959. doi: 10.1016/j.actaastro.2011.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Honn KA, et al. Validation of a portable, touch-screen psychomotor vigilance test. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2015;86(5):428–434. doi: 10.3357/AMHP.4165.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grant DA, et al. 3-minute smartphone-based and tablet-based psychomotor vigilance tests for the assessment of reduced alertness due to sleep deprivation. Behav Res Methods. 2017;49(3):1020–1029. doi: 10.3758/s13428-016-0763-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arsintescu L, et al. Validation of a touchscreen psychomotor vigilance task. Accid Anal Prev. 2019;126:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2017.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Benderoth S, et al. Reliability and validity of a 3-min psychomotor vigilance task in assessing sensitivity to sleep loss and alcohol: fitness for duty in aviation and transportation. Sleep. 2021;44(11):zsab151. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thompson BJ, et al. Test-retest reliability of the 5-minute psychomotor vigilance task in working-aged females. J Neurosci Methods. 2022;365:109379. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2021.109379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jung CM, et al. Comparison of sustained attention assessed by auditory and visual psychomotor vigilance tasks prior to and during sleep deprivation. J Sleep Res. 2011;20(2):348–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00877.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Balkin TJ, et al. Comparative utility of instruments for monitoring sleepiness-related performance decrements in the operational environment. J Sleep Res. 2004;13(3):219–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2004.00407.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Basner M, et al. Maximizing sensitivity of the psychomotor vigilance test (PVT) to sleep loss. Sleep. 2011;34(5):581–591. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Banks S, et al. Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5):519–528. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.26918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ganesan S, et al. The impact of shift work on sleep, alertness and performance in healthcare workers. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):4635. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40914-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hilditch CJ, et al. Sleep inertia during a simulated 6-h on/6-h off fixed split duty schedule. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33(6):685–696. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2016.1167724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kribbs NB, et al. Effects of one night without nasal CPAP treatment on sleep and sleepiness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147(5):1162–1168. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.5.1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lim J, et al. A meta-analysis of the impact of short-term sleep deprivation on cognitive variables. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(3):375–389. doi: 10.1037/a0018883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thomann J, et al. Psychomotor vigilance task demonstrates impaired vigilance in disorders with excessive daytime sleepiness. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(9):1019–1024. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khan OF, et al. Immediate-term cognitive impairment following intravenous (IV) chemotherapy: a prospective pre-post design study. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5349-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilson N, et al. Postpartum fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and psychomotor vigilance are modifiable through a brief residential early parenting program. Sleep Med. 2019;59:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reiter AM, et al. No effect of chronotype on sleepiness, alertness, and sustained attention during a single night shift. Clocks Sleep. 2021;3(3):377–386. doi: 10.3390/clockssleep3030024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Van Dongen HPA, et al. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2003;26(2):117–126. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.2.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Basner M, et al. Repeated administration effects on psychomotor vigilance test performance. Sleep. 2018;41(1):zsx187. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Belenky G, et al. Patterns of performance degradation and restoration during sleep restriction and subsequent recovery: a sleep dose-response study. J Sleep Res. 2003;12(1):1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2003.00337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mollicone DJ, et al. Response surface mapping of neurobehavioral performance: testing the feasibility of split sleep schedules for space operations. Acta Astronaut. 2008;63(7-10):833–840. doi: 10.1016/j.actaastro.2007.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Signal TL, et al. Scheduled napping as a countermeasure to sleepiness in air traffic controllers. J Sleep Res. 2009;18(1):11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00702.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Banks S, et al. Neurobehavioral dynamics following chronic sleep restriction: dose-response effects of one night for recovery. Sleep. 2010;33(8):1013–1026. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.8.1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rupp TL, et al. Banking sleep: realization of benefits during subsequent sleep restriction and recovery. Sleep. 2009;32(3):311–321. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.3.311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Graw P, et al. Circadian and wake-dependent modulation of fastest and slowest reaction times during the psychomotor vigilance task. Physiol Behav. 2004;80(5):695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dinges DF, et al. Effects of modafinil on sustained attention performance and quality of life in OSA patients with residual sleepiness while being treated with nCPAP. Sleep Med. 2003;4(5):393–402. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00108-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wesensten NJ, et al. Modafinil vs. caffeine: effects on fatigue during sleep deprivation. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2004;75(6):520–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Van Dongen HPA, et al. Systematic interindividual differences in neurobehavioral impairment from sleep loss: evidence of trait-like differential vulnerability. Sleep. 2004;27(3):423–433. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.3.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rupp TL, et al. Trait-like vulnerability to total and partial sleep loss. Sleep. 2012;35(8):1163–1172. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Waggoner LB, et al. A combined field and laboratory design for assessing the impact of night shift work on police officer operational performance. Sleep. 2012;35(11):1575–1577. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ferguson SA, et al. Fatigue in emergency service operations: assessment of the optimal objective and subjective measures using a simulated wildfire deployment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(2):171. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13020171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sparrow AR, et al. Naturalistic field study of the restart break in US commercial motor vehicle drivers: Truck driving, sleep, and fatigue. Accid Anal Prev. 2016;93:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2016.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Patterson PD, et al. Impact of shift duration on alertness among air-medical emergency care clinician shift workers. Am J Ind Med. 2019;62(4):325–336. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wilson M, et al. Performance and sleepiness in nurses working 12-h day shifts or night shifts in a community hospital. Accid Anal Prev. 2019;126:43–46. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2017.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Matsangas P, et al. Sleep quality, occupational factors, and psychomotor vigilance performance in the U.S. Navy sailors. Sleep. 2020;43(12):zsaa118. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rahman SA, et al.; ROSTERS STUDY GROUP. Extended work shifts and neurobehavioral performance in resident-physicians. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e2020009936. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-009936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fletcher A, et al. Work schedule and seasonal influence on sleep and fatigue in helicopter and fixed-wing aircraft operations in extreme environments. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):8263. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08996-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jones CW, et al. Sleep deficiency in spaceflight is associated with degraded neurobehavioral functions and elevated stress in astronauts on six-month missions aboard the International Space Station. Sleep. 2022;45(3):zsac006. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsac006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mackworth NH. Researches on the measurement of human performance. Med Res Council Spec Rep Ser. London: H. M. Stationery Office; 1950;268:156. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Broadbent DE. Noise, paced performance and vigilance tasks. Br J Psychol. 1953;44(4):295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1953.tb01210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bills AG. Fatigue in mental work. Physiol Rev. 1937;17:436–453. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1937.17.3.436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Van Dongen HPA, et al. Investigating the temporal dynamics and underlying mechanisms of cognitive fatigue. In: Ackerman PL, ed. Cognitive Fatigue: Multidisciplinary Perspective on Current Research and Future Applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2011:127–147. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tucker AM, et al. The variable response-stimulus interval effect and sleep deprivation: an unexplored aspect of psychomotor vigilance task performance. Sleep. 2009;32(10):1393–1395. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.10.1393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kong D, et al. Increased automaticity and altered temporal preparation following sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2015;38(8):1219–1227. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yang FN, et al. Sleep deprivation enhances inter-stimulus interval effect on vigilant attention performance. Sleep. 2018;41(12):zsy189. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Luce RD. Response Times: Their Role in Inferring Elementary Mental organization. Cary, NC: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bills AG. Blocking: a new principle in mental fatigue. Am J Psychol. 1931;43(2):230–245. doi: 10.2307/1414771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Williams HL, et al. Impaired performance with acute sleep loss. Psychol Monogr. 1959;73(14):1–26. doi: 10.1037/h0093749 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Deaton M, et al. The effect of sleep deprivation on signal detection parameters. Q J Exp Psychol. 1971;23(4):449–452. doi: 10.1080/14640747108400257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gunzelmann G, et al. Fatigue in sustained attention: Generalizing mechanisms for time awake to time on task. In: Ackerman PL, ed. Cognitive Fatigue: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Current Research and Future Applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2011:83–101. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Basner M, et al. A new likelihood ratio metric for the psychomotor vigilance test and its sensitivity to sleep loss. J Sleep Res. 2015;24(6):702–713. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chavali VP, et al. Signal-to-noise ratio in PVT performance as a cognitive measure of the effect of sleep deprivation on the fidelity of information processing. Sleep. 2017;40(3):zsx016. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Horne JA, et al. High incentive effects on vigilance performance during 72 hours of total sleep deprivation. Acta Psychol (Amst). 1985;58(2):123–139. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(85)90003-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rakitin BC, et al. The effects of stimulus degradation after 48 hours of total sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2012;35(1):113–121. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dinges DF. The nature of sleepiness: causes, contexts, and consequences. In: Stunkard AJ, Baum A, eds. Eating, Sleeping, and Sex. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1989:147–179. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Krueger JM, et al. Sleep as a fundamental property of neuronal assemblies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(12):910–919. doi: 10.1038/nrn2521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Van Dongen HPA, et al. A local, bottom-up perspective on sleep deprivation and neurobehavioral performance. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11(19):2414–2422. doi: 10.2174/156802611797470286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rector DM, et al. Local functional state differences between rat cortical columns. Brain Res. 2005;1047(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nir Y, et al. Selective neuronal lapses precede human cognitive lapses following sleep deprivation. Nat Med. 2017;23(12):1474–1480. doi: 10.1038/nm.4433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Åkerstedt T, et al. Subjective sleepiness is a sensitive indicator of insufficient sleep and impaired waking function. J Sleep Res. 2014;23(3):242–254. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Watson D, et al. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hudson AN, et al. Effects of total sleep deprivation on performance on a continuous performance matching task. Sleep. 2022;45(Suppl. 1) :A530119–A530A54. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsac079.117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Honn KA, et al. New insights into the cognitive effects of sleep deprivation by decomposition of a cognitive throughput task. Sleep. 2020;43(7):zsz319. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Basner M, et al. Response speed measurements on the psychomotor vigilance test: how precise is precise enough? Sleep. 2021;44(1):zsaa121. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ratcliff R, et al. Diffusion model for one-choice reaction-time tasks and the cognitive effects of sleep deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(27):11285–11290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100483108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Walsh MM, et al. Computational cognitive modeling of the temporal dynamics of fatigue from sleep loss. Psychon Bull Rev. 2017;24(6):1785–1807. doi: 10.3758/s13423-017-1243-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Honn KA, et al. Total sleep deprivation does not significantly degrade semantic encoding. Chronobiol Int. 2018;35(6):746–749. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1411361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Fournier LR, et al. Action plan interrupted: resolution of proactive interference while coordinating execution of multiple action plans during sleep deprivation. Psychol Res. 2020;84(2):454–467. doi: 10.1007/s00426-018-1054-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hudson AN, et al. Speed/accuracy trade-off in the effects of acute total sleep deprivation on a sustained attention and response inhibition task. Chronobiol Int. 2020;37(9-10):1441–1444. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1811718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ratcliff R, et al. Diffusion decision model: current issues and history. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20(4):260–281. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wilkinson RT. Interaction of lack of sleep with knowledge of results, repeated testing, and individual differences. J Exp Psychol. 1961;62(3):263–271. doi: 10.1037/h0048787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Chee MWL, et al. Functional imaging of inter-individual differences in response to sleep deprivation. In: Nofzinger E, Maquet P, Thorpy MJ, eds. Neuroimaging of Sleep and Sleep Disorders. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013:154–162. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Warm JS, et al. Vigilance requires hard mental work and is stressful. Hum Factors. 2008;50(3):433–441. doi: 10.1518/001872008X312152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Van Dongen HPA, et al. Circadian rhythms in fatigue, alertness, and performance. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine (3rded). Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2000:391–399. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Li L, et al. Age-related frontoparietal changes during the control of bottom-up and top-down attention: an ERP study. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(2):477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Upon reasonable request to K.A.H., the deidentified data can be shared with researchers.