Abstract

Acute exposure to high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) leads to sudden death and, if survived, lingering neurological disorders. Clinical signs include seizures, loss of consciousness, and dyspnea. The proximate mechanisms underlying H2S-induced acute toxicity and death have not been clearly elucidated. We investigated electrocerebral, cardiac, and respiratory activity during H2S exposure using electroencephalogram (EEG), electrocardiogram, and plethysmography. H2S suppressed electrocerebral activity and disrupted breathing. Cardiac activity was comparatively less affected. To test whether Ca2+ dysregulation contributes to H2S-induced EEG suppression, we developed an in vitro real-time rapid throughput assay measuring patterns of spontaneous synchronized Ca2+ oscillations in cultured primary cortical neuronal networks loaded with the indicator Fluo-4 using the fluorescent imaging plate reader (FLIPR-Tetra®). Sulfide >5 ppm dysregulated synchronous calcium oscillation (SCO) patterns in a dose-dependent manner. Inhibitors of NMDA and AMPA receptors magnified H2S-induced SCO suppression. Inhibitors of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and transient receptor potential (TRP) channels prevented H2S-induced SCO suppression. Inhibitors of T-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, ryanodine receptors, and sodium channels had no measurable influence on H2S-induced SCO suppression. Exposures to >5 ppm sulfide also suppressed neuronal electrical activity in primary cortical neurons measured by multielectrode array (MEA), an effect alleviated by pretreatment with the nonselective TRP channel inhibitor, 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate (2-APB). 2-APB also reduced primary cortical neuronal cell death from sulfide exposure. These results improve our understanding of the role of different Ca2+ channels in acute H2S-induced neurotoxicity and identify TRP channel modulators as novel structures with potential therapeutic benefits.

Keywords: hydrogen sulfide, neurotoxicity, in vitro models, calcium dysregulation, transient receptor potential, L-type calcium channel

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), an invisible gas with a rotten egg smell, is an occupational environmental toxicant (Rumbeiha et al., 2016). It is the second most common cause of fatal gas exposures in workplaces (Guidotti, 2015). Recently, H2S gained attention for nefarious uses in chemical terrorism and in suicide (Binder et al., 2018; Morii et al., 2010). H2S is also endogenously produced at low concentrations in multiple organs, including the brain, serving multiple physiological functions in vertebrates. It is naturally synthesized from the amino acids, l-cysteine, and l-cystathionine, catalyzed by multiple enzymes including cystathion-β-synthase, cystathionine-γ-lyase, and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfur transferase (Polhemus and Lefer, 2014).

Acute exposure to high concentrations of H2S induces severe neurotoxicity (Anantharam et al., 2017a,b, 2018; Guidotti, 2010; Kim et al., 2018, 2019; Rumbeiha et al., 2016; Snyder et al., 1995; Tvedt et al., 1991b). At concentrations higher than 500 ppm, H2S causes apnea, seizures, coma, and death (Guidotti, 2015; Rumbeiha et al., 2016). Most deaths occur at the location of exposure (Santana Maldonado et al., 2022). Among survivors, acute H2S exposure often induces delayed neurological sequalae including nausea, persistent headache, movement disorders, impaired memory, amnesia, psychosis, anxiety, depression, sleeping disorders, and coma. Some cases progress to prolonged vegetative states (Rumbeiha et al., 2016; Tvedt et al., 1991a; Wasch et al., 1989). Murine and porcine models of H2S poisoning exhibit seizure activity and loss of consciousness (Anantharam et al., 2017a,b, 2018; Kim et al., 2018, 2019; O'Donoghue, 1961). Seizure activity has a high correlation with loss of consciousness in H2S-exposed mice (Anantharam et al., 2017a). The frequency and severity of seizure activity varies among mice, although seizure severity predicts shorter survival time (Anantharam et al., 2017a, 2018; Kim et al., 2018, 2019). Interestingly, preventing seizures with an anticonvulsant agent prolongs the survival of mice during H2S exposure (Anantharam et al., 2018). Victims of acute H2S poisoning also develop pulmonary edema (Tanaka et al., 1999) and heart failure (Sastre et al., 2013). Results from some animal models indicate cardiac arrest after acute sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) exposure (Haouzi et al., 2015).

Despite this knowledge, it remains unclear what organ(s) primarily mediates H2S-induced physiological dysfunction leading to death and which are second order sequalae of H2S exposure. For example, respiratory arrest will eventually precipitate cardiac arrest as a secondary outcome, but the inverse is also true. Likewise, cardiac and respiratory arrest can both elicit cerebral hypoxia which can trigger electrocerebral suppression and, in extreme cases, seizures; however, seizures and hypoxia can also elicit cardiac and respiratory dysfunction. Determining which factors are initiating the H2S cascade necessitates simultaneous respiratory, cardiac, and electrocerebral recordings under tightly controlled experimental conditions. Moreover, the molecular mechanisms underlying H2S-induced neurotoxicity and death are poorly understood.

It is widely reported that H2S inhibits cytochrome c oxidase enzyme in mitochondria; however, this alone does not explain the broad spectrum of toxic effects from knockdown and coma, to development of vegetative states (Anantharam et al., 2017a,b, 2018; Guidotti, 2015; Kim et al., 2018, 2019; Ng et al., 2019; Snyder et al., 1995; Tvedt et al., 1991a,b). Transcriptomic and proteomic studies of the inferior colliculus in H2S-exposed mice showed that H2S induces dysregulation of multiple biological pathways including calcium homeostasis, oxidative stress, immune response, and neurotransmitters (Kim et al., 2018, 2019).

Calcium homeostasis is important for virtually all neuronal functions. Synchronous calcium oscillations (SCOs) are ubiquitous signaling mechanisms whose frequency and amplitude encode information in both individual neurons (eg, regulating physiologic metabolic and transcriptional responses) and at the level of networks (eg, regulating synaptic connectivity and circadian rhythms) (Alford and Alpert, 2014; Cavieres-Lepe and Ewer, 2021; Tokumitsu and Sakagami, 2022). SCO patterns encode frequency and amplitude signals that provide a means to control a wide range of cellular physiological functions (Smedler and Uhlen, 2014; Sneyd et al., 2017). Dysregulation of SCO patterns has been reported in Alzheimer’s disease (Santos et al., 2009) and Huntington’s disease (Glaser et al., 2021). Various environmental toxicants have also been reported to disrupt SCO in neuronal cell cultures (Cao et al., 2014, 2017; Zheng et al., 2019).

Primary cortical neuronal coculture (PCN) displays spontaneous electrical spike activity that form synchronized and desynchronized field potentials as the PCN develops (Cao et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2019). This PCN model exhibits spontaneous SCOs which are driven by spontaneous electrical spike activity (Cao et al., 2012, 2014; Muramoto et al., 1993; Robinson et al., 1993; Zheng et al., 2019). SCOs are shown to be strongly related to seizure activity in an in vitro epileptic model (Sombati and Delorenzo, 1995). There are several types of Ca2+ channels in the brain that mediate physiological, pharmacological, and toxicological responses (Table 1). However, whether H2S alters SCO patterns and, if so, the channels contributing to dysfunction have not been investigated.

Table 1.

Select calcium channels in the brain, their specific inhibitors, and location

| Ca2+ channel | Inhibitor | Channel location |

|---|---|---|

| AMPAR | perampanel | Cell membrane |

| NMDAR | mK-801 | Cell membrane |

| L-type VGCC | nifedipine | Cell membrane |

| L-type VGCC | nimodipine | Cell membrane |

| T-type VGCC | ethosuximide | Cell membrane |

| TPC | 2-APB | Endoplasmic reticulum or cell membrane |

| Ryanodine receptor | dantrolene | Endoplasmic reticulum |

The present study uses an in vivo mouse model of inhaled H2S to measure brain electroencephalogram (EEG), electrocardiogram (EKG), and plethysmography to determine temporal changes in brain, heart, and lung, respectively, during H2S exposure. We identify suppression of brain electrical activity as the proximal effect of H2S intoxication preceding reduced pulmonary function and death. In combination with our prior knowledge that H2S causes Ca2+ dysregulation in brain and the important role of Ca2+ signaling in regulating neurological functions, we developed an in vitro PCN cell culture model to further test our in vivo findings of acute H2S exposure. The use of FLIPR and multielectrode array (MEA) assays with the PCN culture model provides new information about how H2S alters neuronal Ca2+ signaling and the mechanisms responsible.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Poly-l-Lysine (PLL), Fluo-4 AM, bovine serum albumin (BSA), cytosine β-d-arabinofuranoside (ARA-C), MK-801, nifedipine, nimodipine, 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate (2-APB), and dantrolene were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Perampanel and ethosuximide were generously gifted from Dr. Michael Rogawski, University of California at Davis (UC Davis). Neurobasal media, HEPES, penicillin-streptomycin, B-27 Plus, GlutaMAX, fetal bovine serum (FBS), Flu-4 AM, calcein AM, and Hoechst 33342 were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Animals

Animal use was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of UC Davis or the University of Iowa, Iowa City. Animals were treated humanely and handled with care in accordance with IACUC guidelines.

EEG, EMG, and EKG surgery

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (000664; Bar Harbor, ME). Seven- to 8-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were housed at room temperature of 20–22°C with a 12:12 h light dark cycle. Food (NIH-31 Mouse Diet) and water were available ad libitum. EEG and EKG electrodes were implanted as previously described (Muramoto et al., 1993). Briefly, mice were anesthetized under 1% isoflurane and skull surface was exposed and prepared. The headmount was then secured onto the skull aligning its middle with sagittal suture and the front 2 holes were in front of the coronal suture, while the back 2 holes were in front of the lambdoid suture. Four pilot holes were bored with a 23G hypodermic needle. The screws were coated with silver epoxy and were driven into the holes acting as EEG electrode. Two stainless steel wires extended from the headmount were buried under cervical muscle to collect electromyography (EMG) signals. The headmount was then secured using dental cements. Mice were allowed to recover for at least 1 week before experimentation.

EEG and EKG recording

EEG and EKG signals were acquired and processed as previously described (Purnell et al., 2017). Briefly, the preamplifier (8202-SL; Pinnacle Technology Inc.) was attached to the exposed plug on the implanted EEG headmount. EKG leads (MS303-76; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) were implanted during the same surgery in the left chest wall and right axilla in a modified lead II configuration. The preamplifier cord was passed through an airtight gasket in the custom plethysmography chamber and then attached to a 6-channel commutator (no. 8204; Pinnacle Technology Inc.). The signal was passed to a conditioning amplifier (model 440 Instrumentation Amplifier; Brownlee Precision, San Jose, CA). The EEG signals were amplified (100 times), band-pass filtered (0.3–200 Hz for EEG), and digitized (1000 samples/s; NI USB-6008; National Instruments, Austin, TX). The digitized signal was transferred to a desktop computer and recorded using software custom written in MATLAB (R2018b; MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Whole-body plethysmography

Whole-body plethysmography was employed to measure respiratory parameters during acute H2S exposure. Each animal was acclimated to the chamber. Baseline breathing was recorded for 10 min before exposure to 1000 ppm H2S or regular breathing air from pressurized cylinders. The recording chamber was outfitted with an ultralow volume pressure transducer (DC002NDR5; Honeywell International Inc., Morris Plains, NJ) to detect small pressure waves associated with breathing. The signal was amplified (100 times), band-pass filtered (0.3–30 Hz), and digitized before being recorded with a custom MATLAB software and stored on a desktop computer following previously published protocol (Purnell and Buchanan, 2020). Before H2S or breathing air exposure, the signal was calibrated by delivering metered breaths (300 μl; 150 breaths min−1) via a mechanical ventilator (Mini-Vent; Harvard Apparatus) to the recording chamber. Respiratory function parameters including minute ventilation (VE), tidal volume (VT), and respiratory rate were assessed with MATLAB custom script as previously described (Hodges and Richerson, 2008).

Exposure paradigm

Mice were acclimated to the air-tight exposure chamber for 1 h twice on different days prior to experimentation. EEG, EKG, and whole-body plethysmography recordings were calibrated before exposure to 1000 ppm H2S gas or breathing air from pressurized cylinders. Five minutes of baseline EEG, EKG, and whole-body plethysmography recordings were made before gas exposure. Gas exposure was simulated without an animal twice, while the concentration of H2S in the plethysmography chamber was monitored in real-time using a H2S sensor (RKI instrument, Union City, CA). EEG, EKG, and breathing of C57BL/6J mice was monitored in real-time using implanted electrodes and the air-tight plethysmography chamber as shown in the exposure paradigm figure (Figure 1A). Mice were continuously exposed to the gas until complete cardiac arrest as assessed by EKG (about 2 h) as the endpoint was mortality for this part of the study. Mice in the control group were exposed to normal breathing air, also from a pressurized cylinder.

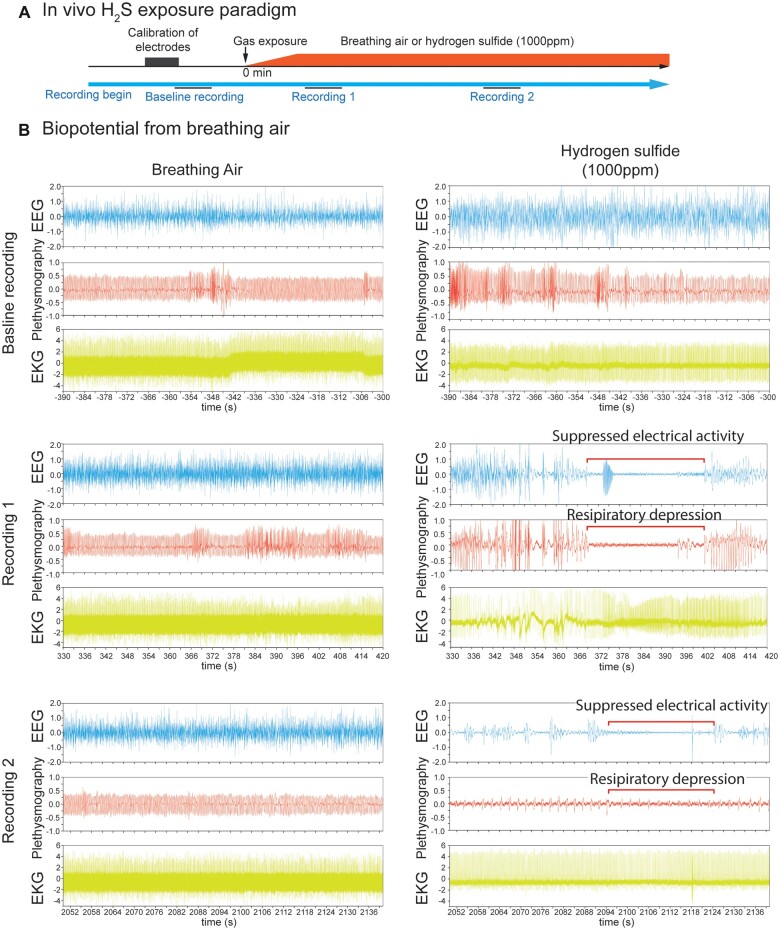

Figure 1.

In vivo H2S-induced suppression of brain activity was concomitant with apnea. Mice were preimplanted with electrodes for EEG and EKG. Breathing activity was recorded by plethysmography. In vivo H2S exposure paradigm was shown in A. After brief calibration of plethysmograph and recordings of biopotentials of baseline activity, mice were exposed to normal breathing air or 1000 ppm H2S (B) until death as assesses by EKG. Baseline recordings displayed EEG, EKG, and plethysmography traces of mice at rest. Recording 1 shows 90 s signal recordings at about 5 min from the start of gas exposure, while Recording 2 shows 90 s signal recordings at about 35 min from the start of gas exposure. Recordings 1 and 2 display typical suppression of EEG and plethysmography in H2S exposed mice (B). Note the H2S-induced electrocerebral suppression and respiratory arrest while cardiac activity persisted (B, Recordings 1 and 2). N = 3 mice. Abbreviations: EEG, electroencephalogram; EKG, electrocardiogram; H2S, hydrogen sulfide.

Primary cortical neuron culture (PCN)

Male and female wild type (WT) C57BL/6J mice (000664) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Sacramento, CA) and were housed in the Teaching and Research Animal Care Services facility (TRACS) at the School of Veterinary Medicine, UC Davis with a 12:12 h light and dark cycle. Room temperature and relative humidity were maintained at 22°C and 50 ± 10% respectively. Dissociated cortical neurons with minimal astrocyte composition were cultured as described previously (Cao et al., 2017). Briefly, neurons were dissociated from the cortex of C57BL/6J mouse pups of both sexes on postnatal day 0–1 and maintained in complete Neurobasal media (50 units of penicillin, 50 μg/ml of streptomycin, 2% [v/v] B-27 Plus, 10 mM HEPES, and 1% [v/v] GlutaMAX) supplemented with 2% FBS. Dissociated cortical neurons were seeded onto the plate precoated with PLL at a density of 1 × 105/well for 96-well plate for fluorescence laser plate reader (FLIPR Tetra; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) or MEA plate. The cell culture media was diluted to 2-fold with complete Neurobasal medium the next day. A final concentration of 10 mM ARA-C was added to the culture medium at 36–48 h of culture to prevent astrocyte proliferation. The culture medium was changed every other day by replacing half volume of the culture medium with serum-free complete Neurobasal medium. PCN were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity until experiment. We used developing primary cortical neurons (PCN) because they express multiple calcium channels and receptors, form neuronal networks, have SCOs, and produce neuronal electrical activity. The use of PCN is advantageous because the protocols to isolate and maintain PCN are well established and because cortex because of size provides the most neurons per individual animal.

Measurement of synchronous Ca2+ oscillations

Synchronous Ca2+ oscillations of the PCN culture were measured using fluorescent labeled calcium indicator and a FLIPR Tetra® system as previously described (Cao et al., 2017). This fluorescent plate reader-based Ca2+ assay allowed measurement of functional Ca2+ signaling in PCN providing a rapid throughput in vitro system to assess the role of various Ca2+ channels in H2S-induced neurotoxicity using various pharmacological probes. Briefly, PCN between day in vitro (DIV) 9 and DIV 16 were used. The growth medium was replaced with a dye loading solution (75 µl/well) containing 5 µM Fluo-4 AM and 0.5% BSA in Neurobasal medium. After incubation for 1 h in the dye loading solution, cells were washed 2 times with Neurobasal medium and once with imaging solution (125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 25 mM HEPES, and 6 mM Glucose at pH 7.2). After washing, the cell medium was gently aspirated, and 125 µl of imaging solution was then added to the cells. The plate was transferred to FLIPR instrument to measure real-time intracellular Ca2+ concentration using a fluorescent signal. The fluorophore within the cells was excited at 488 nm, and Ca2+-bound Fluo-4 emission was recorded at 535 nm. Baseline recordings of SCO were obtained before addition of the toxicant and/or drug probes using a programmable 96-channel robotic pipetting system. Properties of the SCO, including frequency and amplitude were analyzed using scipy module (version 1.7.1) in Python version 3.0 Software script (https://www.python.org/). A typical diagram of peak parameters of the normal SCO is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Multielectrode array recordings

Measuring spontaneous neuronal electrical activities using MEA system (Axion BioSystems, Atlanta, GA) was another cell function assay. It was performed as described previously (Cao et al., 2012). Briefly, dissociated PCN were seeded on to 48-well Maestro plates at a density of 1 × 105/well and maintained by changing growth medium every other day until use on 9–16 DIV. At the time of the experiment, the growth medium was gently aspirated and 125 µl Neurobasal medium was added to the cells. The plate was transferred to the MEA instrument prewarmed to 37°C. Cells were incubated on the MEA system for 5 min before measuring basal electrical activity. Cells were pretreated with vehicle or pharmacological drug probes, followed by exposure to H2S. The MEA instrument recorded and amplified the raw extracellular electrical signals which were digitized in the Axis software at a rate of 25 kHz and filtered using a Butterworth band-pass filter (cutoff frequency of 300 Hz). The Axis software was used to detect spontaneous electrical events, perform spike analysis, and to export the analyzed data.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was performed using ImageXpress® Micro (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA) and cell-permeant dye, calcein AM, according to the manufacture’s protocol. Briefly, PCN were grown in precoated 96-well plate with PLL. Primary cortical neuronal/glial coculture DIV 9–16 were exposed to designated concentrations of H2S for 40 min at 37°C. At the conclusion of the exposure period, the medium was aspirated and replaced with the growth medium. The H2S-exposed PCN were incubated for 72 h at 37°C with change of growth medium after 48 h. Calcein AM was applied to the H2S-exposed PCN and incubated for 30 min before taking images of cells using ImageXpress® Micro. Hoechst 33342 was used for nuclei staining. Live cell counts were calculated using MetaXpress version 6 (Molecular Devices).

Data analysis

Data are presented as mean and standard deviation of the mean. SCO peak parameters were normalized to the baseline values, which were compared to the control group. Statistical analyses of SCO peak parameters were performed by Student’s t-test using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) or ANOVA using scipy statistical module (version 0.12.2) in Python version 3.0 (https://www.python.org/). A p-value of <.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

In vivo acute H2S exposure caused rapid suppression of electrocerebral and respiratory suppression which preceded cardiac dysfunction

Mice exposed to normal air showed normal patterns of EEG, EKG, and plethysmography similar to the resting biopotentials throughout the observation period including recording epoch 1 and epoch 2 depicted in Figure 1B. Exposure to 1000 ppm H2S induced significant disruption in brain and breathing activity starting within recording epoch 1 which became more severe within recording epoch 2 (Figure 1B). Mice exposed to H2S exhibited an unstable burst-suppression pattern of EEG (Figure 1B). Recording epoch 1 (Figure 1B) shows that H2S-induced suppression of electrocerebral and respiratory suppression started as early as 5–7 min into H2S exposure. Thirty-four minutes into exposure (recording epoch 2), suppression of both electrocerebral activity and breathing became prominent (Figure 1B). However, cardiac activity was substantially less strongly impacted. Mice exposed to H2S displayed frequent seizure activity which was followed by loss of postural control, profound electrocerebral suppression, and behavioral immobility, presumably due to a loss of consciousness. The duration of electrographic burst/suppression episodes varied, but typically lasted for a few seconds to about 30 s. H2S exposed mice showed clear behavioral seizure activity before loss of consciousness characterized by myoclonus, body jerks, head bobbing, and loss of postural control; however, the cortical EEG traces during this time were not characterized by the high frequency, high amplitude discharges which typically characterized epileptiform discharges. The electrographic activity became progressively weaker as the exposure to H2S continued. Most notably, periods of electrographic suppression were frequently accompanied by apnea.

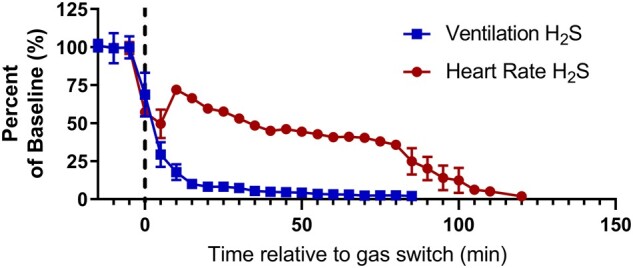

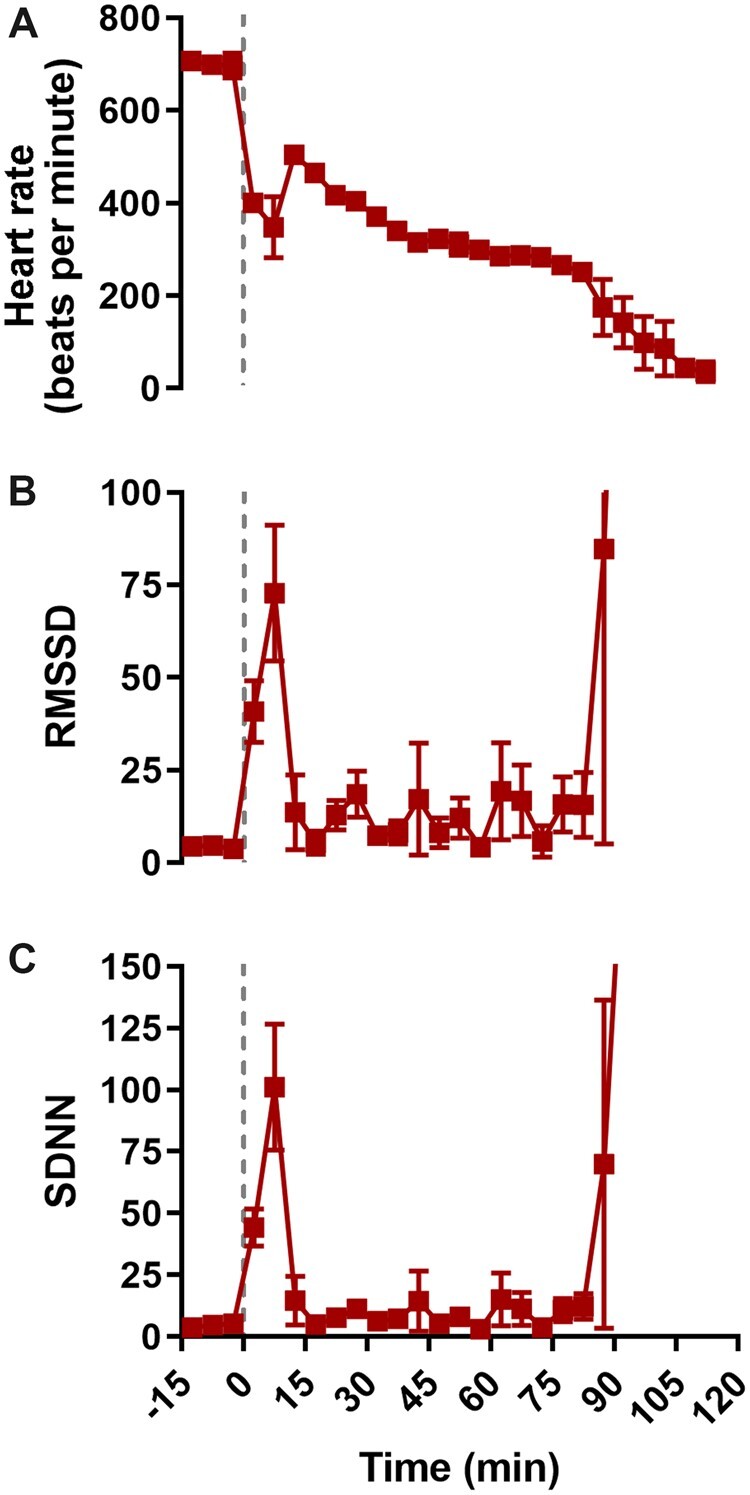

Respiratory suppression began early following the onset of H2S exposure and progressively worsened until the animal died (Figure 2). In contrast, severe suppression of cardiac activity did not occur until >30 min after the onset of H2S exposure (Figures 2 and 3). Furthermore, the suppression of cardiac activity during the first 10 min of H2S exposure was partially recovered (Figures 2 and 3). Given that respiratory suppression was only getting progressively more severe during this time period, it seems likely that the terminal decline in cardiac activity (>30 min following exposure) was the consequence of prolonged hypoxia due to insufficient respiration (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Respiratory suppression precedes cardiac suppression during H2S exposure. Time series data depicting baseline normalized ventilation (squares, ml/min/g) and heart rate (circles; beats per minute) before and during exposure to 1000 ppm H2S. Data are depicted as mean with SEM, n = 3 mice. Baseline was defined as the 15 min prior to H2S administration. Dotted line, start of H2S exposure. Abbreviations: H2S, hydrogen sulfide.

Figure 3.

H2S exposure was characterized by an initial phase of decreased heart rate and increased heart rate variability. Time series data depicting heart rate (A, beats per minute), root-mean square differences of successive R-R intervals (B; RMSSD, ms), and standard deviations of R-R intervals (C, SDNN, ms) before and during exposure to 1000 ppm H2S. Data were depicted as mean with SEM, n = 3 mice. Baseline was defined as the 15 min prior to H2S administration. Grey dotted line, start of H2S exposure. Abbreviations: H2S, hydrogen sulfide.

H2S suppressed synchronous calcium oscillations in primary cortical neuronal networks

SCOs in neurons play important roles in processing and interpreting sensory information in the central nervous system (Muramoto et al., 1993; Robinson et al., 1993). The effects of H2S on SCO in primary cortical neurons (PCN) were examined using a rapid-throughput FLIPR Tetra® system (Figure 4). Cultured PCN DIV 9–16 were exposed to H2S from Na2S, a H2S chemical donor. Na2S is spontaneously converted to H2S in solution under physiological conditions (Equation 1).

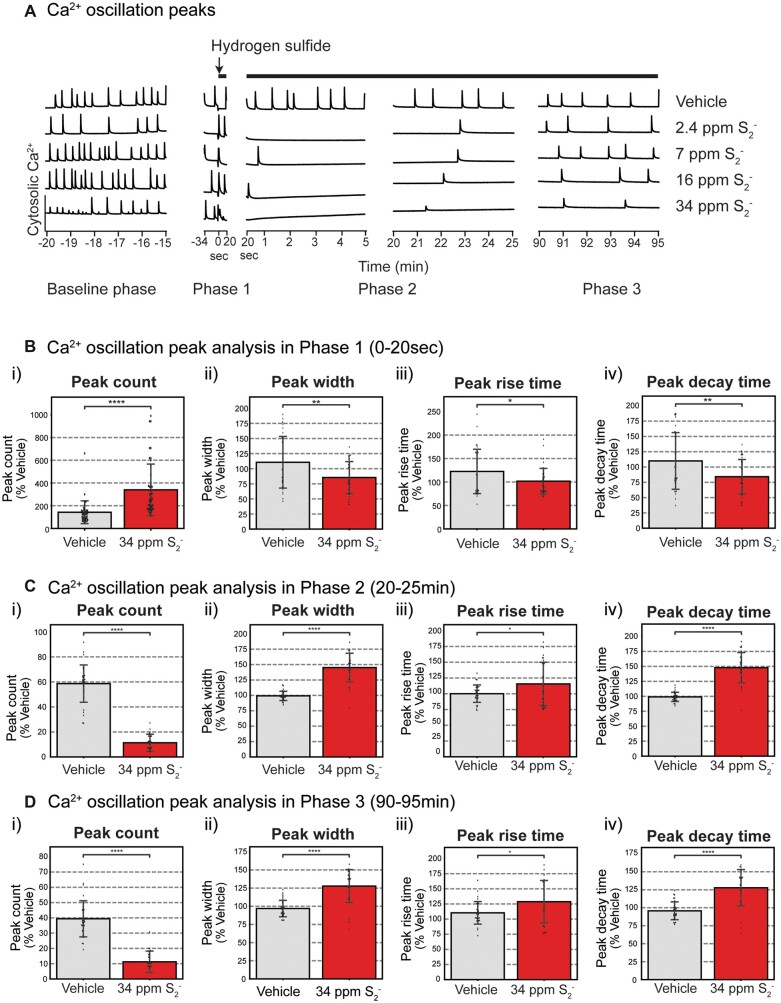

Figure 4.

Synchronous calcium oscillations (SCO) in primary cortical neurons following exposure to H2S. Mouse PCN were exposed to graded concentrations of H2S. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured, and synchronous Ca2+ oscillations were analyzed. A, Traces of Ca2+ oscillations to show dose-response-related effects of H2S exposure. A summary of SCO parameters in H2S exposed PCN for Phase 1 (0–20 s), Phase 2 (20–25 min), and Phase 3 (90–95 min) is shown in graphs B, C, and D, respectively. Please note that H2S increased peak counts in Phase 1 but significantly suppressed this parameter in Phases 2 and 3. Also note that peak width, peak rise time, and peak decay time in Phase 1 were significantly reduced by H2S but significantly increased (reversed) in Phases 2 and 3. N > 30. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation of multiple biological replicates. Each data point represents biological data from cells in a single well. This data are from more than 30 biological replicates that were pooled from 7 experiments of isolated primary cortical neurons. Student’s t test was performed for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to vehicle group. *p < .05, **p < .01, and ****p < .0001. Abbreviations: H2S, hydrogen sulfide.

| (1) |

In pilot experiments, a broad concentration range of sodium sulfide (Na2S), a chemical donor of H2S, was prepared in imaging solution to identify the effective concentration-response relationship for use in our in vitro studies. In solution, H2S dissociates to hydrosulfide (HS-). At high pH (pH >12) HS− is transformed to sulfide (S2−) ion. H2S generated from Na2S in the imaging solution was measured by adjusting the pH to a high pH (>12) to convert all hydrosulfide to S2−. We measured S2− as a biomarker of H2S concentration in solution using a sulfide ion microelectrode. Changes in S2− concentrations over the 60 min for the dose-response study are summarized in Supplementary Figure 2. Results show that the concentrations of S2− decreased over the 60 min observation time, in a concentration-dependent manner.

Effects of high-level H2S exposure by itself on SCO in PCN are summarized in Figure 4. SCO activity at rest in PCN (Baseline phase) was measured 10 min before exposure to graded concentrations of H2S (Figure 4A). During baseline, cultured PCN continuously exhibited baseline patterns of spontaneous SCO activity. Measured parameters included peak count, peak amplitude, peak width, peak rise time, and peak decay time. Exposure to vehicle (control) did not induce any significant changes in SCO peak parameters (Figure 4A). However, addition of H2S induced a biphasic effect on the SCO in PCN. Initially, we observed an acute increase in SCO activity within the first 20–30 s, followed by prolonged suppression of SCO (Figure 4A). We named the acute hyper-active SCO phase as Phase 1, and the subsequent prolonged period of suppressed SCO as Phase 2 (Figure 4A). We also noted that suppression of SCO started to recover at about 90 min after the addition of H2S. We called this recovery phase Phase 3 (Figure 4A).

These effects of H2S were concentration dependent. Statistically significant differences between control and H2S exposed cells in each of the 3 phases are summarized in Figures 4B–D. Note that peak count was significantly increased by H2S in Phase 1 (Figure 5Bi) but significantly suppressed in Phases 2 (Figure 4Ci) and 3 (Figure 4Di) compared to the respective Phases in vehicle control. H2S-exposed PCN showed significantly decreased SCO peak width, peak rise time, and peak decay time in Phase 1 (Figs.4Bii, 4Biii, and 4Biv). These effects of H2S were reversed (increased) in peak width, peak rise time, and peak decay time in Phases 2 and 3 (Figs. 4C and 4D). Effects of H2S on SCO in Phase 2 were reminiscent of comma/depression phenotype in Recording 2 in Figure 1C of the H2S exposed mice in vivo.

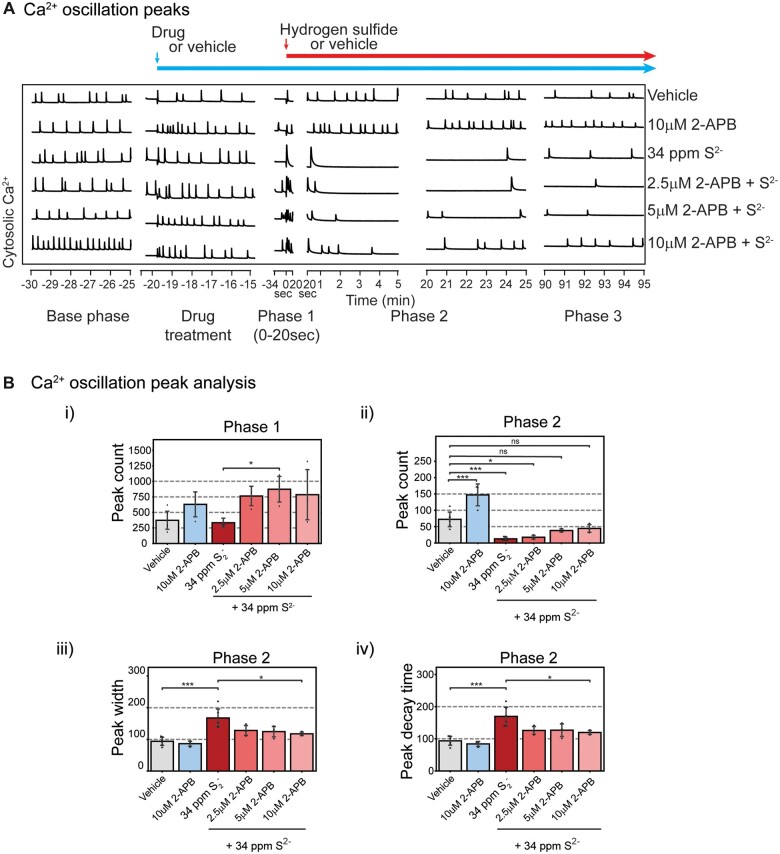

Figure 5.

2-APB at 10 µM antagonized H2S-induced suppression of SCO in Phases 2 and 3 (A). Mouse PCN were pretreated with 2.5–10 µM 2-APB before exposure to H2S. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured, and synchronous Ca2+ oscillations were analyzed. 2-APB by itself at 10 µM significantly increased peak counts in Phase 2 (Bii). B, Analysis of SCO in H2S exposed cortical primary neurons. In Phase 2, 2-APB at 10 µM significantly antagonized H2S-induced increase in peak width and peak decay time (Biii and Biv). Results in Phase 3 are similar to Phase 2 (data not shown). N = 3. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test was performed for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to vehicle group. *p < .05 and ***p < .001. Abbreviations: 2-APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; PCN, primary cortical neuronal coculture; SCO, synchronous calcium oscillation.

Transient receptor potential channel blocker, 2-APB, prevents H2S-induced suppression of SCO

Store-operated Ca2+ entry plays important roles in regulating intracellular Ca2+ in many eukaryotic cells, including neurons (Grudt et al., 1996). Of relevance to potential mechanisms contributing to high concentrations of H2S-induced toxicity observed in vivo is the emerging role of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels as primary mediators of physiological signals mediated by low levels of this gas in several organs, including the brain (Roa-Coria et al., 2019). We therefore examined whether 2-APB, a nonselective inhibitor of TRP channels, many of which function as store operated Ca2+ channels, (Baba et al., 2003) influence H2S-modified phases of SCO dysfunction described above. Mouse PCN were pretreated with 2.5–10 µM 2-APB before exposure to high concentrations of H2S mitigated the influences of H2S (Figure 5A, representative traces). 2-APB by itself at 10 µM showed a tendency to increase peak count during Phase 1, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5Bi) until Phase 2 (Figure 5Bii). 2-APB at 10 µM antagonized H2S-induced suppression of SCO in Phases 2 and 3. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured, and synchronous Ca2+ oscillations were analyzed. Pre-exposure to 10 µM 2-APB effectively antagonized the effects of H2S in Phases 2 and 3. Pretreatment with 2-APB dose-dependently increased peak counts in Phase 2 (Figure 5Bii). Also in Phase 2, 2-APB at 10 µM significantly antagonized H2S-induced increase in peak width and peak decay time (Figs. 5Biii and 5Biv). Results in Phase 3 were like those in Phase 2 (data not shown).

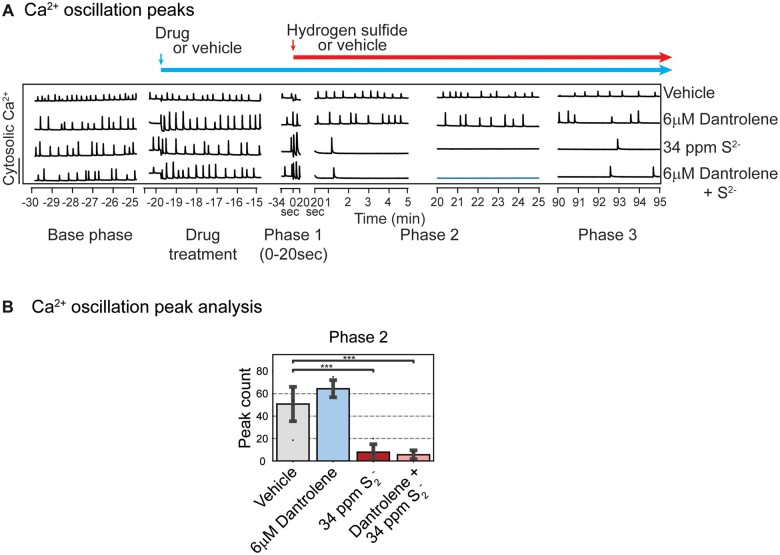

To further investigate the role of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-derived calcium in H2S-induced suppression of SCO we used dantrolene, a ryanodine receptor signaling inhibitor, as a pharmacological probe (Hayashi et al., 1997). Preliminary dose-range finding studies were done to optimize the concertation of dantrolene for use in this experiment. It is interesting that dantrolene did not show efficacy in preventing H2S-induced suppression of SCO (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Mouse PCN were pretreated with 6 µM dantrolene before exposure to H2S. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured, and synchronous Ca2+ oscillations were analyzed. A, Traces of Ca2+ oscillations are shown. Note that pretreatment with dantrolene had no impact on H2S-induced SCO in Phases 2 and 3. B, A summary of SCO peak counts in H2S exposed cortical primary neurons in Phase 2. Note that dantrolene failed to prevent on H2S-induced suppression of peak counts. Similar results were observed for peak width and peak decay time in Phases 2 and 3 (data not shown). N = 3. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test was performed for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to vehicle group. ***p < .001. Abbreviations: H2S, hydrogen sulfide; PCN, primary cortical neuronal coculture; SCO, synchronous calcium oscillation.

Ca2+ channel blockers differentially influence abnormal SCO patterns triggered by H2S

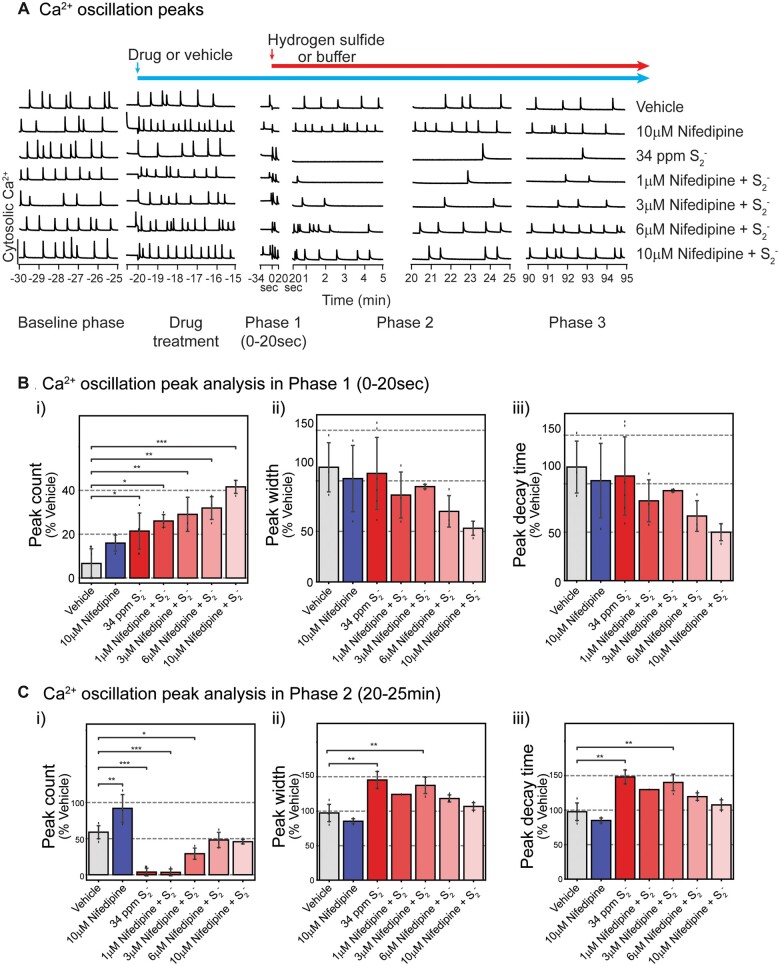

We proceeded to investigate pharmacological blockers with a spectrum of selectivity toward a number of neuronal voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels to determine whether the mitigating effects observed with 2-APB could be generalized. Basal SCO activities were recorded prior to application of pharmacological drugs as depicted with baseline shown in Figure 7A. PCN were pretreated with nifedipine (1–10 µM), followed by exposure to high concentration of H2S (34 ppm S2−). SCOs in each phase were assessed (Figs. 7B and 7C). Pretreatment with nifedipine significantly and dose-dependently increased acute H2S-induced SCO peak counts in Phase 1 compared to vehicle (control) group (Figure 7Bi). Although nifedipine dose-dependently reduced peak width and peak decay time in Phase 1, these were not statistically significant compared to vehicle control (Figs. 7Bii and 7Biii).

Figure 7.

Pre-exposure to nifedipine, an inhibitor of L-type voltage-dependent calcium channel, antagonized H2S-induced suppression of SCO in Phases 1–3 at 6 and 10 µM in mouse PCN. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured, and SCO were analyzed. A, Traces of Ca2+ oscillations showing that nifedipine at 6 and 10 µM effectively prevented H2S-induced dysregulation of SCO. A summary of SCO characteristics in H2S exposed PCN for Phase 1 (0–20 s) and Phase 2 (20–25 min) in B and C. Effects of nifedipine in Phase 3 were similar to those in Phase 2 (data not shown). N = 3. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test was performed for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to vehicle group. *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001. Abbreviations: H2S, hydrogen sulfide; PCN, primary cortical neuronal coculture; SCO, synchronous calcium oscillation.

Consistent with results shown in Figure 4 H2S suppressed peak counts in Phase 2 but pretreatment with nifedipine antagonized this H2S-induced effect at 6 and 10 µM concentrations (Figure 7Ci). In Phase 2 H2S increased both peak width and peak decay time consistent with observations in Figure 4. Notably, pretreatment with 6 or 10 µM nifedipine prevented H2S-induced increase in peak width (Figure 7Cii) and peak decay time (Figure 7Ciii). Effects of Nif in Phase 3 were like those in Phase 2 (data not shown). An interesting observation was that pretreatment with nimodipine, a chemically related L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel inhibitor, failed to prevent H2S-induced suppression of SCO in PCN (Figs. 8Aiii and 8Biii).

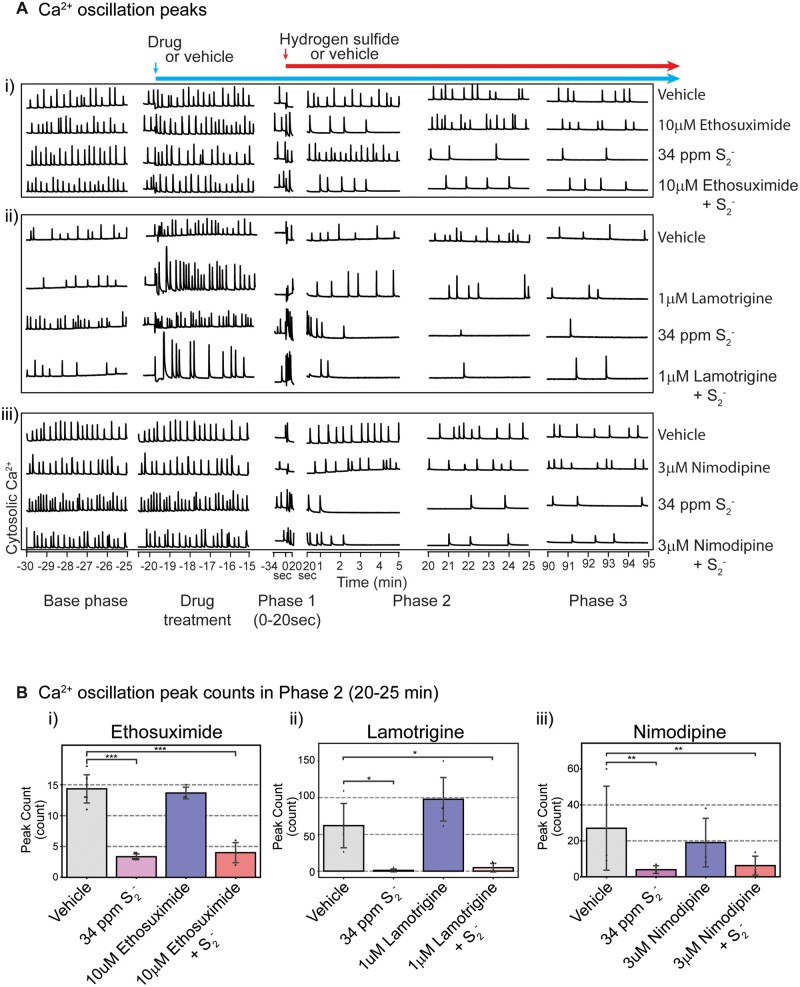

Figure 8.

Ethosuximide, lamotrigine, and nimodipine failed to prevent H2S-induced suppression of SCO. Mouse cortical primary neurons were pretreated with ethosuximide, lamotrigine, or nimodipine before exposure to H2S. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured, and synchronous Ca2+ oscillations were analyzed. A, Traces of Ca2+ oscillations. B, A summary of analyses of SCO activity in H2S exposed cortical primary neurons following pretreatment with ethosuximide, lamotrigine, and nimodipine. N = 3. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test was performed for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to vehicle group. *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001. Abbreviations: H2S, hydrogen sulfide; SCO, synchronous calcium oscillation.

To investigate the role T type Ca2+ channels play in H2S-induced neurotoxicity, ethosuximide, a T type Ca2+ channel blocker, was used. As was the case for nifedipine and nimodipine, preliminary dose-range finding studies were done to select the ideal test dose for ethosuximide, lamotrigine, and nimodipine. Pretreatment with ethosuximide did not prevent H2S-induced suppression of SCO peak counts (Figs. 8Ai and 8Bi). We then used lamotrigine to investigate the effects of sodium channels on H2S-induced toxicity. Lamotrigine is a voltage-dependent sodium channel blocker (Cheung et al., 1992). Pretreatment with lamotrigine also failed to antagonize the effects of H2S-induced dysregulation on SCO in both Phase 1 and Phase 2 (Figure 8Aii).

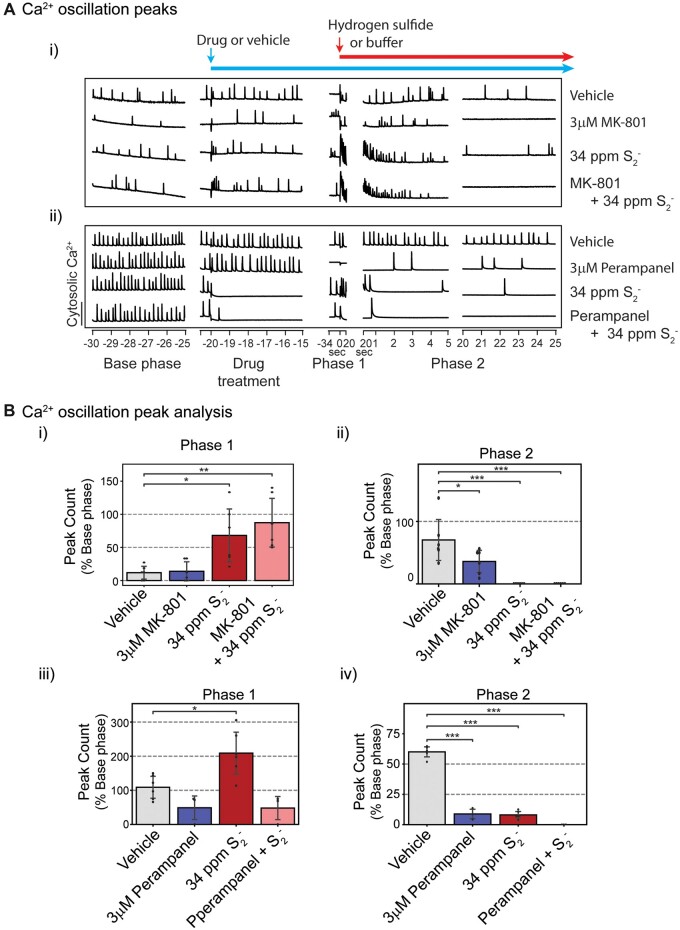

NMDA and AMPA receptor antagonists failed to prevent H2S-induced suppression of SCO

It has been reported that H2S toxicity is mediated by glutamate (Cheung et al., 2007) and that it induces influx of Ca2+ through NMDA receptors. MK-801, an NMDA receptor inhibitor, was used to investigate the role of NMDA receptors in H2S-induced suppression of SCO (Figure 9). As with other pharmacological probes, preliminary range finding studies were performed to select the optimal concentration for MK-801 and perampanel (an AMPA receptor blocker) (Joshi et al., 2011). Pretreatment of PCN with MK-801 alone induced suppression of SCO. Addition of high concentration of H2S exacerbated the MK-801-induced suppression of SCO in PCN (Figs. 9Ai and 9Bii). Pretreatment of PCN with perampanel, suppressed SCO activity (Figs. 9Aii, 9Biii, and 9Biv). Unique among all drug probes used in this study, perampanel prevented H2S-induced increase in peak counts in Phase 1 (Figure 9Biii). However, in Phase 2, pretreatment with perampanel augmented H2S-induced suppression of SCO in PCN (Figure 9Biv).

Figure 9.

Mouse PCN were pretreated with MK-801 or perampanel before exposure to H2S. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured, and synchronous Ca2+ oscillations were analyzed. A, Traces of Ca2+ oscillations were shown. Inhibitors for NMDA receptor and AMPA receptor failed to antagonize H2S-induced suppression of SCO in Phase 2 (A). B, Analysis of SCO in H2S exposed PCN. MK-801 failed to prevent H2S-induced effects on peak counts in Phases 1 and 2 (Bi and Bii). Perampanel significantly prevented H2S-induced increase in peak counts in Phase 1 (Biii) but worsened H2S-induced decrease in peak counts in Phase 2 (Biv). N = 3. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test was performed for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to vehicle group. *p < .05 and ***p < .001. Abbreviations: H2S, hydrogen sulfide; PCN, primary cortical neuronal coculture; SCO, synchronous calcium oscillation.

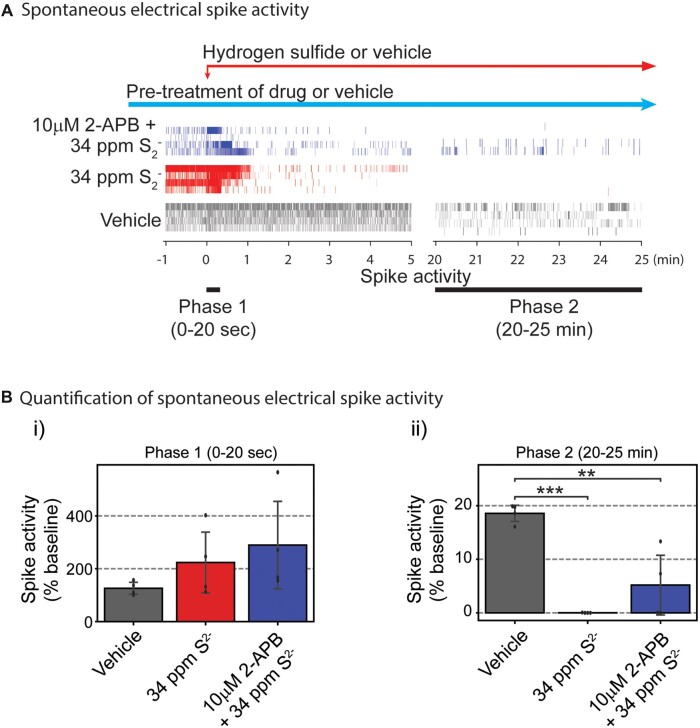

Pretreatment with 2-APB prevented H2S-induced suppression of neuronal electrical network spike activity in primary cortical neurons using MEA

Considering the overall activity of 2-APB toward mitigating the 3 phases of H2S-triggered SCO dysfunction, we plated PCN on MEAs to measure electrical spike activity (Johnstone et al., 2010). Spontaneous neuronal electrical spike activity in PCN at rest was measured before treatments to obtain 10 min of baseline. Following recording of baseline activity, PCN were pretreated with 10 µM 2-APB or buffer 20 min before addition of a high concentration of H2S (34 ppm S2−). Recording of neuronal electrical activity was initiated 1 min before H2S was added (Figure 10A). Neuronal spike activity was detected by the Axis software. Addition of H2S immediately induced hyperactive electrical stimulation by more than 75% compared to vehicle group (Figs. 10A and 10Bi) which was followed by suppression of electrical activity (Figs. 10A and 10Bii). We named the hyperexcitation period as Phase 1 and the suppression phase as Phase 2, similar to our data analysis strategy with FLIPR. Pretreatment with 2-APB prevented H2S-induced acute hyper-active electrical activity in Phase 1. Whereas H2S significantly suppressed neuronal electrical activity in Phase 2 (20 min after H2S exposure), 2-APB pretreatment modestly prevented H2S-induced suppression of neuronal electric activity by 27% compared to the vehicle group (Fig. 10Bii).

Figure 10.

Neuronal electrical activities were measured using the multiple-electrode array system (MEA). Mouse PCN were pretreated with 2-APB or vehicle before exposure to a H2S donor. A, spontaneous neuronal electrical spike activities are shown. Addition of H2S-induced hyperactive electrical spike activity in Phase 1, whereas pretreatment with 2-APB modestly antagonized H2S-induced suppression of electrical activity in Phases 1 and 2. B, Spontaneous electrical spike activities in PCN were quantified. Note that pretreatment with 2-APB modestly antagonized H2S-induced suppression of electrical activity in Phase 2 (Bii). N = 4. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test was performed for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to vehicle group. **p < .01 and ***p < .001. Abbreviations: 2-APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; PCN, primary cortical neuronal coculture.

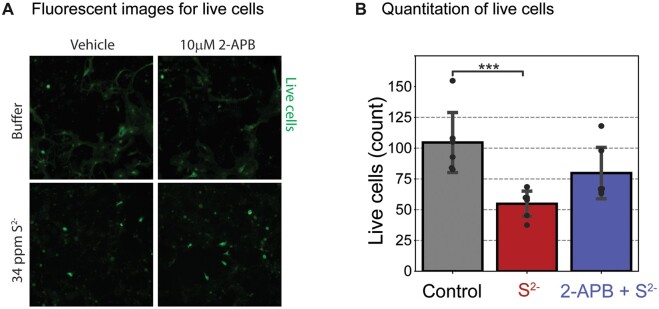

2-APB protected cortical neurons from H2S-induced cell death

Of the diverse ion channel probes investigated in this study, 2-APB was the most interesting as far as antagonizing effects of H2S on SCO. We therefore investigated whether the antagonistic effects of 2-APB observed in this study had impact on H2S-induced neuronal cell death. To do this, a cell viability assay was performed using ImageXpress® Micro (Molecular Devices) and cell-permeant dye, calcein AM, according to the manufacture’s protocol (Figure 11). PCN DIV 9–15 were pretreated with 2-APB or buffer 10 min before exposure to a high concentration of H2S (34 ppm S2−) for 40 min. The H2S exposure medium was then replaced with fresh cell growing medium. Cells were incubated for 72 h after H2S exposure before assessing cell death by counting the live cells using fluorescent calcein dye (Figure 11A). A summary of results of live cells is shown in Figure 11B. H2S by itself induced about 50% cell mortality. For cells pretreated with 10 µM 2-APB, only 25% cell mortality was observed (Figure 11B). These preliminary results suggest that 2-APB was neuroprotective in this model.

Figure 11.

Mouse PCN were pretreated with 10 µM 2-APB and exposed to H2S for 40 min only. The cells were washed and incubated for 72 h before imaging of live cells to assess cell survival. A, Live cortical neurons were imaged using cell-permeable calcein AM fluorescent dye. B, A summary of results. Pretreatment with 2-APB significantly increased cell survival compared to the H2S group. N = 6. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test was performed for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to Control group. ***p < .001. Abbreviations: 2-APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; PCN, primary cortical neuronal coculture.

Discussion

The toxicity of H2S is complex and the proximate cause of death following acute high concentrations of H2S exposure is debatable. Moreover, the molecular mechanisms of H2S-induced neurotoxicity are not known. The study addressed several of these gaps in knowledge. First, in the in vivo study we show that it is electrocerebral suppression which precipitates respiratory suppression and outright apnea. Cardiac arrest is of later onset and likely a consequence of hypoxia due to prolonged respiratory insufficiency and/or H2S-induced lack of ATP. The onset of H2S exposure mildly decreased cardiac activity and increased heart rate variability. These mild changes in heart function partially recovered early during exposure. In contrast, respiratory suppression was severe and did not recover (Figs. 2 and 3). H2S exposure rapidly elicited a burst-suppressed EEG pattern in which periods of electrographic suppression frequently coincided with apnea (Figure 1). As the exposure progressed, periods of bursting became less regular giving way to complete electrocerebral suppression (Figure 1). This progressive electrocerebral dysfunction was temporally mirrored by progressive decreases in breathing until respiration was no longer compatible with life (Figs. 1 and 3). It is interesting however that we did not see clear epileptiform discharges in this study, suggesting that the electrographic seizure activity was localized to the brainstem. This is supported by our observations that seizure activity in this model are akin to audiogenic induced seizures in DBA mice and other models which originate from the brainstem.

Respiratory rhythmogenesis is a function of the brain, specifically pre-Bötzinger complex within the ventrolateral medulla (Smith et al., 1991). The coincidence between episodes of electrocerebral suppression and frank apnea may be indicative of transient periods neuronal inactivity across the entirety of the brain, including the respiratory nuclei of the brainstem. The data presented here indicate that (1) the electrocerebral dysfunction induced by H2S exposure is the driving force behind the respiratory dysfunction and (2) the cardiac dysfunction observed in the later stages of H2S exposure are causally downstream to the electrocerebral/respiratory dysfunction.

To further understand the mechanisms involved in electrocerebral suppression, we developed an in vitro model of PCN which recapitulated the in vivo H2S-induced EEG using SCO in FLIPR and electrical spike activity using MEA. In this study we used PCN because primary neuron/astrocyte coculture have functional receptors, unlike immortalized cell lines. FLIPR is a fluorescent plate reader-based assays that allows fast and simultaneous readings of intracellular Ca2+ of cells in multiple wells. Use of PCN with rapid-throughput systems using FLIPR and MEA allowed us to gain insights in the role of the various calcium channels in acute H2S-induced toxicity on the brain.

SCO is driven by action potentials in the neurons. The infinite patterns of frequency of SCO and changes of SCO frequency or amplitude provides important means to fulfill diverse cellular and tissue functions (Smedler and Uhlen, 2014). Dysregulation of SCO in neurons is also implicated in toxicant-induced neuronal dysfunction (Cao et al., 2012). As shown in FLIPR experiments, H2S induced an acute hyper-active neuronal firing upon addition of H2S (Phase 1), followed by suppression of spontaneous neuronal firings in MEA system (Phase 2). The acute hyper-active SCO and neuronal firing is akin to the seizure like burst suppression activity that was observed in vivo whereas suppressed SCO and suppressed neuronal firings are akin to loss of consciousness or central nervous system depression characteristic of acute H2S poisoning.

Acute hyper-active SCO in Phase 1 was characterized by increased SCO peak count and a shorter SCO peak rise time, width, and decay time indicating the cycle of SCO is much faster, which is also corresponds with the acute hyper-active neuronal firings in the MEA system. Phase 2 SCO is characterized by wider peak width and by increased SCO peak decay time. Action potential drives SCO in cortical neurons (Robinson et al., 1993), and action potential initiates opening of sodium channels in neurons (Grider et al., 2022). We hypothesize that the acute hyper-active SCO plays a role in prolonged suppression of SCO in PCN. Treatment with 1 µM lamotrigine, a sodium channel blocker, by itself significantly decreased SCO peak count in Phase 1, whereas 30 µM lamotrigine completely abolished SCO in Phase 1 (data not shown). However, lamotrigine failed to prevent H2S-induced acute hyper-active SCO in Phase 1, within 20 s of adding H2S (data not shown). These results indicate that H2S may induce acute hyper excitability in neurons in Phase 1 via a different mechanism other than through the lamotrigine-sensitive sodium channel.

Neurons have numerous Ca2+ channels targeted to specific anatomical regions that mediate specific physiological functions (Berridge, 2016; Brini et al., 2014). We investigated select Ca2+ channel blockers for their ability to reverse H2S-induced dysregulation of SCO including acute hyper-active (Phase 1), prolonged suppression (Phase 2) and recovery (Phase 3) SCO epochs that we identified as biomarkers of cellular dysfunction using the FLIPR Tetra® imaging system. We observed that not all Ca2+ channel blockers had the same influence on the 3 phases of H2S-triggered Ca2+ dysregulation. Moreover, those that showed efficacy toward antagonizing effects of H2S did not reverse all 3 phases of dysfunction. For example, nifedipine failed to suppress acute hyper-active SCO in Phase 1 but it reversed H2S-induced suppression of SCO in Phase 2. It is not clear what the exact mechanism(s) behind nifedipine-induced reversal of suppressed SCO by H2S exposure are at this time. Further research is needed to understand more about nifedipine-induced reversal of SCO when PCN culture was exposed to H2S. Although both nifedipine and nimodipine are L type VGCC inhibitors and are used for anti-seizure treatment, they showed different efficacy toward seizures(Grabowski and Johansson, 1985; Konrad-Dalhoff et al., 1991). Nimodipine has a higher efficacy toward blocking CaV1.3α1 (Xu and Lipscombe, 2001), whereas nifedipine blocks CaV 1.2 at lower concentrations that nimodipine (Wang et al., 2018). Nifedipine and nimodipine were also shown to inhibit T-type calcium channels. However, ethosuximide, another T-type calcium channel inhibitor, in this study failed to reverse H2S-induced suppression of SCO in PCN. These results showed that H2S-induced neurotoxicity is not mediated through T-type receptors as blockage of T-type VGCC channels using ethosuximide failed to reverse H2S -suppressed SCO in PCN. Even though nifedipine showed efficacy in reversing H2S-induced suppression of SCO in vitro, this drug was reported to induce hypotension in vivo. H2S poisoning was also reported to induce hypotension (Baldelli et al., 1993) limiting the possible use of nifedipine as a drug for treating victims of H2S poisoning.

TRP channels mediate Store-operated Ca2+ (SOC) entry (Lopez et al., 2020) and have previously been implicated in H2S-induced pathophysiology (Ng et al., 2019; Pozsgai et al., 2019). Pre-exposure to 2-APB showed partial efficacy by preventing H2S-induced suppression of SOC in Phase 2. 2-APB, like nifedipine, failed to antagonize effects of H2S in Phase 1. Previously, SCO was shown to require cyclic Ca2+ entry through the NMDA receptor in cerebellar neurons via activated P-type Ca2+ channel (Nunez et al., 1996). We have shown that H2S suppresses neuronal electrical activity in PCN, and that 10 µM 2-APB antagonized this, reversing it to a degree. TRP channels are a large group of channels with multiple sub-families, and diverse groups of proteins are involved (Samanta et al., 2018). 2-APB is a nonselective blocker of TRP channels and SOCE. 2-APB also antagonizes IP3R and store-operated Ca2+ channel in ER (Splettstoesser et al., 2007). Activation of SOC entry is triggered by the depletion of Ca2+ stores in ER (Bollimuntha et al., 2017). Dantrolene antagonizes ryanodine receptor in ER and inhibits calcium release. 2-APB may also play a role in inhibiting voltage-gated and calcium-dependent potassium conductance and affecting on depolarization of membrane potential (Hagenston et al., 2009). Though promising, as a nonselective TRP blocker, 2-APB might induce off-target effects. More research is warranted to investigate the efficacy of 2-APB and to study the efficacy of other more selective TRP antagonists in acute H2S-induced neurotoxicity.

Hydrogen sulfide is known to inhibit cytochrome c oxidase activity in mitochondria (Anantharam et al., 2017a) depleting ATP. It is plausible that H2S-induced depletion of ATP might lead to Ca2+ dysregulation via glutamate receptor. The NMDA receptor has been implicated in H2S-induced neurotoxicity because MK-801, an NMDA receptor inhibitor protects cerebellar granule neurons (Cheung et al., 2007; Garcia-Bereguiain et al., 2008). However, other investigators reported that H2S-induced neurotoxicity was not improved by use of NMDA receptor inhibitors (Kurokawa et al., 2011). In this study, MK-801 exacerbated H2S-induced suppression of SCO in PCN. This implies that H2S acting through NMDA receptors plays a role in regulating SCO in PCN through Ca2+ signaling. Pretreatment with perampanel also exacerbated H2S-induced suppression of SCO. Dravid and Murray (2004) showed that glutamate and AMPA receptors play a role in spontaneous SCO in neocortical neurons. Findings from this study are consistent with those observations and is further evidence that glutamate and AMPA receptors are involved in regulating SCO during H2S intoxication.

Hydrogen sulfide exposure induces many neurological dysfunctions including motor, behavioral, memory, and visual impairment, and induces neurological sequalae (Nam et al., 2004; Tvedt et al., 1991a) including neuronal cell death in select brain regions (Anantharam et al., 2017a,b, 2018; Kim et al., 2018, 2019). Inhibition of the breathing center in the brainstem and/or prolonged coma have been linked to death and neurological complications (Guidotti, 1994; Sonobe and Haouzi, 2015). Whether the distribution or physiological differences of calcium channels are responsible for this selective sensitivity of specific brain regions deserves investigations in future studies. In summary preventing or reversing dysregulation of Ca2+ signaling may be one of the ways to treat acute H2S-induced neurotoxicity, and reduce mortality and morbidity.

Conclusion

Hydrogen sulfide is a potent toxicant targeting the brain, lung, and heart. In this study, we examined brain, lung, and heart function in real-time during H2S exposure. H2S suppressed electrocerebral activity and disrupted breathing. Cardiac activity was comparatively less affected. This in vivo study provided direct evidence that it is the H2S-induced dysregulation of brain activity that triggers breathing challenges and not vice versa. It also showed that heart function is the last to fail of the 3 major target organs of H2S poisoning. We were also able to recapitulate the in vivo brain electrical activity using a simple in vitro model of PCN in 2 neuronal function assays FLIPR and MEA. Using the in vitro functional PCN model we showed that following a single acute H2S exposure, 3 phases of H2S-induced neurotoxicity were discernible using FLIPR and MEA. Phase 1 is characterized by hyperactivity. Phase 2 is characterized by suppressed electrical activity. Phase 3 is characterized by recovery. H2S consistently induced phase-specific changes in peak count, peak width, peak rise time, and peak decay time. Using these parameters, we showed that nifedipine, an L-type voltage-gated calcium channel inhibitor antagonized H2S-induced suppression of SCO in PCN. Surprisingly, nimodipine, another L-type voltage-gated calcium channel antagonist, failed. Blockage of Store-operated Ca2+ entry by 2-APB also prevented H2S-induced suppression of SCO and neuronal electrical activity and was protective of the PCN. NMDA and AMPA receptors were shown to be involved in H2S-induced regulation of SCO. For example, pretreatment with perampanel effectively antagonized effects of H2S in Phase 1. However, like MK-801, it worsened the effects of H2S in Phase 2, further suppressing SCO. Notably, we have developed a rapid in vitro system consisting of FLIPR and MEA to study the role of various Ca2+ channels in H2S-induced neurotoxicity. Used in conjunction with ImagExpress® high content imaging, we can also assess the neuroprotective efficacy of test articles and drug candidates to treat acute H2S-induced neurotoxicity. Drugs that can normalize H2S-induced Ca2+ dysregulation may have therapeutic potential in reducing H2S-induced mortality and morbidity. We plan to use this in vitro system to further understand the role of calcium in H2S-induced neurotoxicity and for potential discovery of novel and repurposed drugs for treatment of acute H2S poisoning to reduce mortality and/or morbidity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Dr Michael A. Rogawski for generously donating the ethosuximide and perampanel for this study. We also appreciate Raissa Raineri for valuable technical support. We also acknowledge funding from Mind Institute IDDRC (P50HD103526) for high content imaging included in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dong-Suk Kim, Department of Molecular Biosciences, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, Davis, California 95616, USA.

Isaac N Pessah, Department of Molecular Biosciences, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, Davis, California 95616, USA.

Cristina M Santana, VDPAM, College of Veterinary Medicine, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 50011, USA; MRIGlobal, Kansas City, Missouri 64110, USA.

Benton S Purnell, Department of Neurology, Iowa Neuroscience Institute, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52246, USA; Department of Nerosurgery, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA.

Rui Li, Department of Neurology, Iowa Neuroscience Institute, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52246, USA.

Gordon F Buchanan, Department of Neurology, Iowa Neuroscience Institute, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52246, USA.

Wilson K Rumbeiha, Department of Molecular Biosciences, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, Davis, California 95616, USA.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

Funding

Internal grants of UC Davis and Iowa State University for Wilson Rumbeiha.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alford S. T., Alpert M. H. (2014). A synaptic mechanism for network synchrony. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8, 290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharam P., Kim D. S., Whitley E. M., Mahama B., Imerman P., Padhi P., Rumbeiha W. K. (2018). Midazolam efficacy against acute hydrogen sulfide-induced mortality and neurotoxicity. J. Med. Toxicol. 14, 79–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharam P., Whitley E. M., Mahama B., Kim D. S., Imerman P. M., Shao D., Langley M. R., Kanthasamy A., Rumbeiha W. K. (2017a). Characterizing a mouse model for evaluation of countermeasures against hydrogen sulfide-induced neurotoxicity and neurological sequelae. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1400, 46–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharam P., Whitley E. M., Mahama B., Kim D. S., Sarkar S., Santana C., Chan A., Kanthasamy A. G., Kanthasamy A., Boss G. R., et al. (2017b). Cobinamide is effective for treatment of hydrogen sulfide-induced neurological sequelae in a mouse model. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1408, 61–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba A., Yasui T., Fujisawa S., Yamada R. X., Yamada M. K., Nishiyama N., Matsuki N., Ikegaya Y. (2003). Activity-evoked capacitative Ca2+ entry: Implications in synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 23, 7737–7741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldelli R. J., Green F. H., Auer R. N. (1993). Sulfide toxicity: Mechanical ventilation and hypotension determine survival rate and brain necrosis. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 75, 1348–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J. (2016). The inositol trisphosphate/calcium signaling pathway in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 96, 1261–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder M. K., Quigley J. M., Tinsley H. F. (2018). Islamic state chemical weapons: A case contained by its context? CTC Sentinel 11, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bollimuntha S., Pani B., Singh B. B. (2017). Neurological and motor disorders: Neuronal store-operated Ca(2+) signaling: An overview and its function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 993, 535–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brini M., Cali T., Ottolini D., Carafoli E. (2014). Neuronal calcium signaling: Function and dysfunction. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 2787–2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z., Cui Y., Nguyen H. M., Jenkins D. P., Wulff H., Pessah IN. (2014). Nanomolar bifenthrin alters synchronous Ca2+ oscillations and cortical neuron development independent of sodium channel activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 85, 630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z., Hammock B. D., McCoy M., Rogawski M. A., Lein P. J., Pessah IN. (2012). Tetramethylenedisulfotetramine alters Ca2+ dynamics in cultured hippocampal neurons: Mitigation by NMDA receptor blockade and GABAA receptor-positive modulation. Toxicol. Sci. 130, 362–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z., Xu J., Hulsizer S., Cui Y., Dong Y., Pessah IN. (2017). Influence of tetramethylenedisulfotetramine on synchronous calcium oscillations at distinct developmental stages of hippocampal neuronal cultures. Neurotoxicology 58, 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavieres-Lepe J., Ewer J. (2021). Reciprocal relationship between calcium signaling and circadian clocks: Implications for calcium homeostasis, clock function, and therapeutics. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 14, 666673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung H., Kamp D., Harris E. (1992). An in vitro investigation of the action of lamotrigine on neuronal voltage-activated sodium channels. Epilepsy Res. 13, 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung N. S., Peng Z. F., Chen M. J., Moore P. K., Whiteman M. (2007). Hydrogen sulfide induced neuronal death occurs via glutamate receptor and is associated with calpain activation and lysosomal rupture in mouse primary cortical neurons. Neuropharmacology 53, 505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravid S. M., Murray T. F. (2004). Spontaneous synchronized calcium oscillations in neocortical neurons in the presence of physiological [mg(2+)]: Involvement of AMPA/kainate and metabotropic glutamate receptors. Brain Res. 1006, 8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bereguiain M. A., Samhan-Arias A. K., Martin-Romero F. J., Gutierrez-Merino C. (2008). Hydrogen sulfide raises cytosolic calcium in neurons through activation of L-type Ca2+ channels. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser T., Shimojo H., Ribeiro D. E., Martins P. P. L., Beco R. P., Kosinski M., Sampaio V. F. A., Correa-Velloso J., Oliveira-Giacomelli A., Lameu C., et al. (2021). Atp and spontaneous calcium oscillations control neural stem cell fate determination in Huntington’s disease: A novel approach for cell clock research. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 2633–2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski M., Johansson B. B. (1985). Nifedipine and nimodipine: Effect on blood pressure and regional cerebral blood flow in conscious normotensive and hypertensive rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 7, 1127–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grider M. H., Jessu R., Kabir R. (2022). Physiology, action potential. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL. [PubMed]

- Grudt T. J., Usowicz M. M., Henderson G. (1996). Ca2+ entry following store depletion in sh-sy5y neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 36, 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti T. L. (1994). Occupational exposure to hydrogen sulfide in the sour gas industry: Some unresolved issues. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 66, 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti T. L. (2010). Hydrogen sulfide: Advances in understanding human toxicity. Int. J. Toxicol. 29, 569–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti T. L. (2015). Hydrogen sulfide intoxication. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology (Lotti M., Bleecker M. L., Eds.), 3rd ed., Vol. 131, pp. 111–133. Elsevier, Cambridge, MA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenston A. M., Rudnick N. D., Boone C. E., Yeckel M. F. (2009). 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl-borate (2-APB) increases excitability in pyramidal neurons. Cell Calcium 45, 310–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haouzi P., Chenuel B., Sonobe T. (2015). High-dose hydroxocobalamin administered after H2S exposure counteracts sulfide-poisoning-induced cardiac depression in sheep. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila) 53, 28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T., Kagaya A., Takebayashi M., Oyamada T., Inagaki M., Tawara Y., Yokota N., Horiguchi J., Su T. P., Yamawaki S. (1997). Effect of dantrolene on KCl- or NMDA-induced intracellular Ca2+ changes and spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation in cultured rat frontal cortical neurons. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 104, 811–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges M. R., Richerson G. B. (2008). Contributions of 5-HT neurons to respiratory control: Neuromodulatory and trophic effects. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 164, 222–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone A. F., Gross G. W., Weiss D. G., Schroeder O. H., Gramowski A., Shafer T. J. (2010). Microelectrode arrays: A physiologically based neurotoxicity testing platform for the 21st century. Neurotoxicology 31, 331–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi D. C., Singh M., Krishnamurthy K., Joshi P. G., Joshi N. B. (2011). AMPA induced Ca2+ influx in motor neurons occurs through voltage gated Ca2+ channel and Ca2+ permeable AMPA receptor. Neurochem. Int. 59, 913–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.-S., Anantharam P., Hoffmann A., Meade M. L., Grobe N., Gearhart J. M., Whitley E. M., Mahama B., Rumbeiha W. K. (2018). Broad spectrum proteomics analysis of the inferior colliculus following acute hydrogen sulfide exposure. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 355, 28–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. S., Anantharam P., Padhi P., Thedens D. R., Li G., Gilbreath E., Rumbeiha W. K. (2019). Transcriptomic profile analysis of brain inferior colliculus following acute hydrogen sulfide exposure. Toxicology 430, 152345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad-Dalhoff I., Baunack A. R., Ramsch K. D., Ahr G., Kraft H., Schmitz H., Weihrauch T. R., Kuhlmann J. (1991). Effect of the calcium antagonists nifedipine, nitrendipine, nimodipine and nisoldipine on oesophageal motility in man. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 41, 313–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa Y., Sekiguchi F., Kubo S., Yamasaki Y., Matsuda S., Okamoto Y., Sekimoto T., Fukatsu A., Nishikawa H., Kume T., et al. (2011). Involvement of ERK in NMDA receptor-independent cortical neurotoxicity of hydrogen sulfide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 414, 727–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez J. J., Jardin I., Sanchez-Collado J., Salido G. M., Smani T., Rosado J. A. (2020). TRPC channels in the SOCE scenario. Cells 9, 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morii D., Miyagatani Y., Nakamae N., Murao M., Taniyama K. (2010). Japanese experience of hydrogen sulfide: The suicide craze in 2008. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 5, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramoto K., Ichikawa M., Kawahara M., Kobayashi K., Kuroda Y. (1993). Frequency of synchronous oscillations of neuronal activity increases during development and is correlated to the number of synapses in cultured cortical neuron networks. Neurosci. Lett. 163, 163–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam B., Kim H., Choi Y., Lee H., Hong E. S., Park J. K., Lee K. M., Kim Y. (2004). Neurologic sequela of hydrogen sulfide poisoning. Ind. Health 42, 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng P. C., Hendry-Hofer T. B., Witeof A. E., Brenner M., Mahon S. B., Boss G. R., Haouzi P., Bebarta V. S. (2019). Hydrogen sulfide toxicity: Mechanism of action, clinical presentation, and countermeasure development. J. Med. Toxicol. 15, 287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez L., Sanchez A., Fonteriz R. I., Garcia-Sancho J. (1996). Mechanisms for synchronous calcium oscillations in cultured rat cerebellar neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 8, 192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donoghue J. G. (1961). Hydrogen sulphide poisoning in swine. Can. J. Compar. Med. Vet. Sci. 25, 217–219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polhemus D. J., Lefer D. J. (2014). Emergence of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous gaseous signaling molecule in cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 114, 730–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozsgai G., Batai I. Z., Pinter E. (2019). Effects of sulfide and polysulfides transmitted by direct or signal transduction-mediated activation of trpa1 channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 176, 628–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnell B. S., Buchanan G. F. (2020). Free-running circadian breathing rhythms are eliminated by suprachiasmatic nucleus lesion. J. Appl. Physiol. 129, 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnell B. S., Hajek M. A., Buchanan G. F. (2017). Time-of-day influences on respiratory sequelae following maximal electroshock-induced seizures in mice. J. Neurophysiol. 118, 2592–2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roa-Coria J. E., Pineda-Farias J. B., Barragan-Iglesias P., Quinonez-Bastidas G. N., Zuniga-Romero A., Huerta-Cruz J. C., Reyes-Garcia J. G., Flores-Murrieta F. J., Granados-Soto V., Rocha-Gonzalez H. I. (2019). Possible involvement of peripheral trp channels in the hydrogen sulfide-induced hyperalgesia in diabetic rats. BMC Neurosci. 20, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson H. P., Kawahara M., Jimbo Y., Torimitsu K., Kuroda Y., Kawana A. (1993). Periodic synchronized bursting and intracellular calcium transients elicited by low magnesium in cultured cortical neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 70, 1606–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbeiha W., Whitley E., Anantharam P., Kim D. S., Kanthasamy A. (2016). Acute hydrogen sulfide-induced neuropathology and neurological sequelae: Challenges for translational neuroprotective research. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1378, 5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta A., Hughes T. E. T., Moiseenkova-Bell V. Y. (2018). Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. Subcell Biochem. 87, 141–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana Maldonado C., Weir A., Rumbeiha W. K. (2022). A comprehensive review of treatments for hydrogen sulfide poisoning: Past, present, and future. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 33, 183–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos S. F., Pierrot N., Morel N., Gailly P., Sindic C., Octave J. N. (2009). Expression of human amyloid precursor protein in rat cortical neurons inhibits calcium oscillations. J. Neurosci. 29, 4708–4718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre C., Baillif-Couniou V., Kintz P., Cirimele V., Bartoli C., Christia-Lotter M. A., Piercecchi-Marti M. D., Leonetti G., Pelissier-Alicot A. L. (2013). Fatal accidental hydrogen sulfide poisoning: A domestic case. J. Forensic Sci. 58, S280–S284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedler E., Uhlen P. (2014). Frequency decoding of calcium oscillations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1840, 964–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. C., Ellenberger H. H., Ballanyi K., Richter D. W., Feldman J. L. (1991). Pre-botzinger complex: A brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science 254, 726–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneyd J., Han J. M., Wang L., Chen J., Yang X., Tanimura A., Sanderson M. J., Kirk V., Yule D. I. (2017). On the dynamical structure of calcium oscillations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 114, 1456–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J. W., Safir E. F., Summerville G. P., Middleberg R. A. (1995). Occupational fatality and persistent neurological sequelae after mass exposure to hydrogen sulfide. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 13, 199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sombati S., Delorenzo R. J. (1995). Recurrent spontaneous seizure activity in hippocampal neuronal networks in culture. J. Neurophysiol. 73, 1706–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonobe T., Haouzi P. (2015). H2s induced coma and cardiogenic shock in the rat: Effects of phenothiazinium chromophores. Clin. Toxicol. 53, 525–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splettstoesser F., Florea A. M., Busselberg D. (2007). IP(3) receptor antagonist, 2-APB, attenuates cisplatin induced Ca2+-influx in HeLa-S3 cells and prevents activation of calpain and induction of apoptosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 151, 1176–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S., Fujimoto S., Tamagaki Y., Wakayama K., Shimada K., Yoshikawa J. (1999). Bronchial injury and pulmonary edema caused by hydrogen sulfide poisoning. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 17, 427–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumitsu H., Sakagami H. (2022). Molecular mechanisms underlying Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase signal transduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 11025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tvedt B., Edland A., Skyberg K., Forberg O. (1991a). Delayed neuropsychiatric sequelae after acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning: Affection of motor function, memory, vision and hearing. Acta Neurol. Scand. 84, 348–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tvedt B., Skyberg K., Aaserud O., Hobbesland A., Mathiesen T. (1991b). Brain damage caused by hydrogen sulfide: A follow-up study of six patients. Am. J. Ind. Med. 20, 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Tang S., Harvey K. E., Salyer A. E., Li T. A., Rantz E. K., Lill M. A., Hockerman G. H. (2018). Molecular determinants of the differential modulation of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 by nifedipine and FPL 64176. Mol. Pharmacol. 94, 973–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasch H. H., Estrin W. J., Yip P., Bowler R., Cone J. E. (1989). Prolongation of the P-300 latency associated with hydrogen sulfide exposure. Arch. Neurol. 46, 902–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Lipscombe D. (2001). Neuronal Ca(V)1.3alpha(1) L-type channels activate at relatively hyperpolarized membrane potentials and are incompletely inhibited by dihydropyridines. J. Neurosci. 21, 5944–5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Yu Y., Feng W., Li J., Liu J., Zhang C., Dong Y., Pessah IN., Cao Z. (2019). Influence of nanomolar deltamethrin on the hallmarks of primary cultured cortical neuronal network and the role of ryanodine receptors. Environ Health Perspect 127, 67003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.