Abstract

Background:

Imaging biomarkers have the potential to distinguish between different brain pathologies based on the type of ligand used with PET. AV-45 PET (florbetapir, Amyvid™) is selective for the neuritic plaque amyloid of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), while AV-133 PET (florbenazine) is selective for VMAT2, which is a dopaminergic marker.

Objective:

To report the clinical, AV-133 PET, AV-45 PET, and neuropathological findings of three clinically diagnosed dementia patients who were part of the Avid Radiopharmaceuticals AV133-B03 study as well as the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders (AZSAND).

Methods:

Three subjects who had PET imaging with both AV-133 and AV-45 as well as a standardized neuropathological assessment were included. The final clinical, PET scan, and neuropathological diagnoses were compared.

Results:

The clinical and neuropathological diagnoses were made blinded to PET scan results. The first subject had a clinical diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB); AV-133 PET showed bilateral striatal dopaminergic degeneration, and AV-45 PET was positive for amyloid. The final clinicopathological diagnosis was DLB and AD. The second subject was diagnosed clinically with probable AD; AV-45 PET was positive for amyloid, while striatal AV-133 PET was normal. The final clinicopathological diagnosis was DLB and AD. The third subject had a clinical diagnosis of DLB. Her AV-45 PET was positive for amyloid and striatal AV-133 showed dopaminergic degeneration. The final clinicopathological diagnosis was multiple system atrophy and AD.

Conclusion:

PET imaging using AV-133 for the assessment of striatal VMAT2 density may help distinguish between AD and DLB. However, some cases of DLB with less-pronounced nigrostriatal dopaminergic neuronal loss may be missed.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid, AV-133, dementia with Lewy bodies, synucleinopathy, VMAT2

INTRODUCTION

As the population of the United States ages, there is an increasing burden of neurodegenerative diseases in the elderly. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is second only to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as a leading cause of dementia in elderly individuals, and Parkinson’s disease (PD) is overall the second most common neurodegenerative disease [1]. Even though clinical criteria have been established for antemortem diagnosis and for distinguishing these conditions from each other, there remains significant misdiagnosis when compared to gold-standard pathologic confirmation [2, 3], and clinical recognition of DLB is achieved in only a minority of subjects [4]. Imaging biomarkers based on the underlying pathology have been employed to improve diagnostic accuracy for clinical and research purposes. 2-[18F] fluoro-2-Deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has been in use for more than 25 years to help in the diagnosis of AD by assessing the cerebral metabolic rate of glucose [5], and there are now three PET tracers that are FDA-approved for the demonstration of neuritic plaques [6-8], allowing greatly improved AD diagnostic accuracy [9]. The ability to enrich clinical trials with subjects that have the targeted molecular pathology, and to identify neurodegenerative disorders in the prodromal or preclinical phase, is critical for increasing clinical trial efficiency of potential disease-modifying therapies [10].

Vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) is a nonselective transporter responsible for packaging of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin into monoamine vesicles [11]. There is interest in PET imaging of VMAT2 to identify the dopamine-deficient state. The imaging of VMAT2 has potential advantages over dopamine transporter imaging (DAT) as it is not affected by dopaminergic drugs [11]. AV-133 (florbenazine) is a fluorinated VMAT2 PET ligand designed to measure dopaminergic degeneration by in vivo assessment of striatal VMAT2 density in patients with PD [12]. Besides differentiating PD from essential tremor and drug-induced parkinsonism, PET imaging of VMAT2 may help in differentiating DLB from AD [13]. AV-45 (florbetapir, Amyvid™) is the first PET ligand to receive US FDA approval for the assessment of neuritic plaque amyloid [6].

The current study reports three patients with an antemortem clinical diagnosis of AD or DLB who underwent both AV-45 and AV-133 PET scans to assess the extent of cortical amyloid burden as well as striatal dopaminergic degeneration, respectively (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01503944). Recruited subjects included those with clinical diagnoses of AD, DLB, and PD as well as clinically normal subjects. Clinical and imaging results were compared to the neuropathological diagnosis at autopsy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the AV133-B03 study (Clinical-Trials.gov identifier: NCT00857506), sponsored by Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. Results and methodology from the trial have previously been reported [13]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Banner Sun Health Research Institute (BSHRI) in Sun City, AZ.

Briefly, subjects were > 50 years and had to be able to tolerate two PET imaging sessions. DLB subjects were enrolled if they met the diagnostic criteria for probable DLB [14] and did not meet the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and Alzheimer’s disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria for probable AD [15]. AD subjects were enrolled if they met the NINCDS criteria for probable AD, had a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score at screening between 10 and 24 inclusive and had no symptoms of parkinsonism.

Subjects were examined by neurologists, given a clinical diagnosis, and subsequently had PET imaging with AV-133 and AV-45. Three study subjects who had also been enrolled in the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders (AZSAND) [16] were autopsied after death by the Brain and Body Donation Program (http://www.brainandbodydonationprogram.org). The AV-133 and AV-45 PET scans were independently read while blinded to clinical diagnosis by 5 experienced nuclear medicine physicians. The interpretation given by the majority of the five readers for each image was used for analysis. For AV-133, the readers conducted a binary assessment of the presence or absence of dopaminergic degeneration based on the intensity and distribution of uptake in the striatum. Quantitative imaging measures were not used to make the binary reads. The neuropathological findings were recorded blinded to clinical diagnosis and imaging results by a single neuropathologist (T.G.B.). Research, clinical, and neuropathological records were available for review. Final clinical and clinicopathological diagnoses were compared.

Immunohistochemical staining for VMAT2 was performed and the staining intensity quantified on the left anterior caudate nucleus of the imaged subjects as well as in three clinically normal autopsied subjects without parkinsonism, dementia, or postmortem Lewy body disease. Cryostat sections (10 μm) of fresh-frozen left anterior caudate nuclei were incubated overnight with 1 : 3,000 dilutions of rabbit VMAT2 antibody (Invitrogen, OTI10C11), followed by biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG and an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vector), with intervening wash steps, then developed in 3,3’-diaminobenzidine with saturated nickel ammonium sulfate. Three photomicrographs were taken at 400x magnification of each section and then analyzed with ImageJ for area occupied by stained tissue elements exceeding a standard optical density threshold. The means for each case were compared graphically and with an unpaired, 2-tailed t-test.

RESULTS

Case results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of cases including clinical, imaging, and clinicopathological diagnosis

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at symptom onset (y) | 62 | 58–60 | 81 | N/A |

| Age at death (y) | 68 | 67 | 84 | 72.7SD 17.6 |

| AV-45 findings | Positive for amyloid | Positive for amyloid | Positive for amyloid | N/A |

| AV-133 findings | Bilateral caudate and putamen dopaminergic depletion | Normal | Dopaminergic depletion in center putamen and 3/5 readers noted a decrease in right putamen as well | N/A |

| Clinical diagnosis at PET imaging | DLB | AD | DLB | N/A |

| Clinicopathological diagnosis | DLB and AD | DLB and AD | MSA and AD | Cognitively normal |

| Time between symptoms and imaging | 5 y | 5 y | 3 y | N/A |

| Time between PET imaging and death | 22 mo | 30 mo | 1–2 wk | N/A |

| Postmortem interval | 3.0 h | 3.1 h | 2.5 h | 4.0 h SD 0.8 |

| NIA-AA ADNC | High ADNC | Intermediate ADNC | Intermediate ADNC | Not AD (1) Low AD (2) |

| Lewy body stage | Neocortical | Neocortical | N/A (MSA) | All Stage 0 |

NIA-AA ADNC, National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Alzheimer’s Disease Neuropathological Change Level; Lewy body stage, Unified Staging System for Lewy Body Disorders stage level; N/A, not applicable.

Case 1

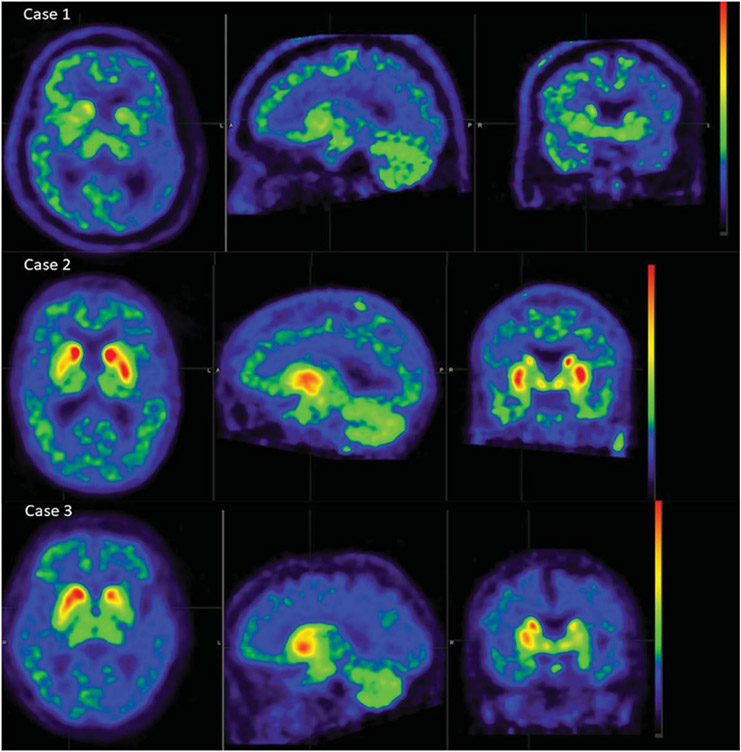

A 68-year-old male had symptoms of cognitive impairment and right upper extremity tremor beginning in October 2006, when he scored 27/30 on the MMSE. By March 2007, he declined to 22/30 on the MMSE, and comprehensive neuropsychological testing showed impairment in verbal and visual memory, naming, executive function, semantic fluency, and visuospatial function. In the fall of 2007, he had been diagnosed with parkinsonism and dementia and was being treated with carbidopa-levodopa, with a beneficial response. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors were started, but he was intolerant of these. His cognitive function then rapidly declined so that by September 2010, his MMSE score was 2/30. He had been having visual hallucinations when seen in September 2009 and a diagnosis of DLB was made. His UPDRS motor score was initially 4 in September 2008 and worsened to 33 in October 2009. He had no history of REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), and no fluctuations of alertness, cognition, or motor function. The final clinical diagnostic impression was DLB at the time of entry into the AV133-B03 trial and his AV-133 PET scan, done in July 2010, was consistent with bilateral dopaminergic depletion, in both putamen and caudate nucleus, according to 5/5 study readers (Fig. 1a). The AV-45 PET scan in May 2010 was read as positive by all 5 readers. He died of cardiac arrest in May 2012, two years after PET imaging.

Fig. 1.

AV-133 PET images for the three studied cases. Case 1 (top) was read as having bilateral dopaminergic depletion in putamen and caudate by all 5 study readers. Case 2 (middle) was read as normal, without dopaminergic depletion in caudate or putamen, by all 5 readers. Case 3 (bottom) was read by all 5 readers as having a decreased signal in the left putamen, while 3/5 noted a decrease in right putamen and one indicated the decreases were asymmetrical, left > right; all 5 readers reported no decrease in left or right caudate nuclei.

General autopsy findings were notable for coronary atherosclerosis and clinically unsuspected prostatic adenocarcinoma, confined to the prostate. The brain weight was 1,302 grams. Gross neuropathological findings included moderate depigmentation of the substantia nigra and mild atrophy of the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus. Microscopic examination with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) showed moderate to severe depletion of pigmented neurons from the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus, with Lewy bodies within remaining neurons in both regions. Immunohistochemical staining for phosphorylated α-synuclein showed frequent immunoreactive neuronal perikaryal inclusions and fibers in the olfactory bulb, brainstem, amygdala, and throughout the cerebral cortex, meeting Unified Staging System for Lewy Body Disorders (USSLB) stage IV (neocortical) [17]. Gallyas, Campbell-Switzer, and thioflavin-S staining showed frequent diffuse and neuritic neocortical amyloid plaques, Braak neurofibrillary stage V neurofibrillary change and Thal amyloid phase V, A3B3C3, “high” Alzheimer’s disease neuropathological change (ADNC) [18]. The final clinicopathological diagnoses were DLB and AD.

Case 2

A 67-year-old woman presented to a neurologist in August 2010 with a 4–5-year history of word finding difficulty, apathy, decreased sense of direction, depression, misplacing objects, and forgetting conversations. There were no signs or symptoms of parkinsonism, RBD, hallucinations or fluctuations in cognition or alertness. She scored 27/30 on the MMSE and neuropsychological testing showed mild impairment in memory and executive function. An FDG-PET scan revealed asymmetric hypometabolism involving the right temporal and posterior parietal lobe, while brain MRI was reported normal for her age. She was diagnosed with dementia and probable AD and was treated with donepezil, memantine, and anti-depressants. In January 2011, she scored 3 on the motor UPDRS, 1 point each for rapid bilateral alternating hand movements, and 1 for left leg agility. The patient was entered into the AV-133 study with a diagnosis of AD. The official study interpretation was absence of dopaminergic depletion in both left and right caudate and putamen for 5/5 readers (Fig. 1b). The AV-45 PET scan was read as positive by all 5 readers. She continued to decline, scoring 22/30 on the MMSE in November 2011. In 2012, she was found to have bilateral rest tremor in the upper extremities and myoclonus associated with visual hallucinations. In 2013, she developed urinary incontinence and lost the ability to walk and swallow. She died in August 2013 of cardiorespiratory arrest, two years after AV-133 and AV-45 PET imaging.

An autopsy was restricted to the brain. The brain weight was 1,216 grams, and pertinent gross findings included severe depigmentation of the substantia nigra and mild atrophy of the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus. Microscopic examination with H&E showed severe and moderate depletion of pigmented neurons from the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus, respectively, with Lewy bodies seen within remaining neurons in both regions. Immunohistochemical staining for phosphorylated α-synuclein showed frequent immunoreactive neuronal perikaryal inclusions and fibers in the olfactory bulb, brainstem, amygdala, and cerebral cortex, meeting USSLB stage IV criteria (Neocortical). Gallyas, Campbell-Switzer, and thioflavin-S staining showed frequent diffuse and neuritic neocortical amyloid plaques, Braak stage IV neurofibrillary change and Thal amyloid phase IV, A3B2C3, “intermediate” ADNC. The final clinicopathological diagnoses were DLB and AD.

Case 3

An 84-year-old woman was seen in January 2009 with a three-year history of hand tremor at rest and imbalance. She was started on antidepressants for the symptoms of anxiety and depression. In December 2009, she scored 25/30 on the MMSE, losing points on orientation, attention, and calculation. In April 2010, she had been diagnosed with PD and was being treated with carbidopa-levodopa. In June 2010, her major problems were with memory and loss of mobility. She was repeating stories, was often disoriented to time, and more disoriented when in unfamiliar places. She gave up driving a car and was having delusions but not hallucinations. There was no history suggestive of RBD, but daytime somnolence and fluctuation of alertness were present. Examination revealed shuffling gait, stooped posture, bradykinesia, rigidity, a right upper extremity rest tremor, and myoclonus. She scored 27/30 on the MMSE. The diagnostic impression was of DLB, and she was started on rivastigmine, with no clear benefit. In February 2011, she scored 17 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and 55 on the motor UPDRS. Later that month she was entered into the AV-133 study with a diagnosis of DLB. An AV-133 PET scan in May 2011 showed, for 5/5 readers, decreased signal in the left putamen, while 3/5 noted a decrease in the right putamen and one indicated that the decreases were asymmetrical, left > right (Fig. 1c). All 5 readers reported no decrease in the caudate nuclei. The AV-45 PET scan was read as positive by all 5 readers. She died 10 days after her last imaging session.

General autopsy findings were pertinent for coronary atherosclerosis and cardiomegaly. The brain weight was 1,046 grams. Pertinent gross findings included moderate depigmentation of the substantia nigra and mild atrophy of the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus. The left head of the caudate nucleus, putamen, and globus pallidus were markedly atrophied with reddish-brown discoloration while on the right side these structures showed only mild atrophy. Microscopic examination of H&E-stained left-sided brain structures showed moderate depletion of pigmented neurons from the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus with moderate to marked gliosis and tissue rarefaction of the head of the caudate nucleus and putamen. The Campbell-Switzer and Gallyas silver stains showed frequent diffuse and neuritic neocortical plaques with Braak neurofibrillary stage V and Thal amyloid phase II, A1B3C3, “intermediate” ADNC. Also seen were frequent crescentic and flame-shaped silver-stained inclusions within the perinuclear cytoplasm of oligodendrocytes throughout all brain regions but with particularly high densities in the frontal and temporal lobe white matter, the caudate and putamen, the globus pallidus, and the substantia nigra. Immunohistochemical staining for phosphorylated α-synuclein showed identical oligodendroglial inclusions, as well as sparse neuronal inclusions, in all sections examined, including the olfactory bulb, medulla, pons, amygdala, cerebral cortex, and all levels of the spinal cord. The final clinicopathological diagnoses were multiple system atrophy (MSA) and AD.

Control subjects

Three autopsied and neuropathologically-examined subjects were without parkinsonism or dementia during life and had no Lewy body disease or synucleinopathy postmortem. The subjects had not had prior imaging, biochemistry, or histological staining for dopaminergic markers. All had no depletion of substantia nigra pigmented neurons on H&E slide examination. The subjects were one male and two females, aged 53, 78, and 87 years. The brains were processed at death with the same methods as for the AV-133-imaged brains.

VMAT2 immunohistochemical staining

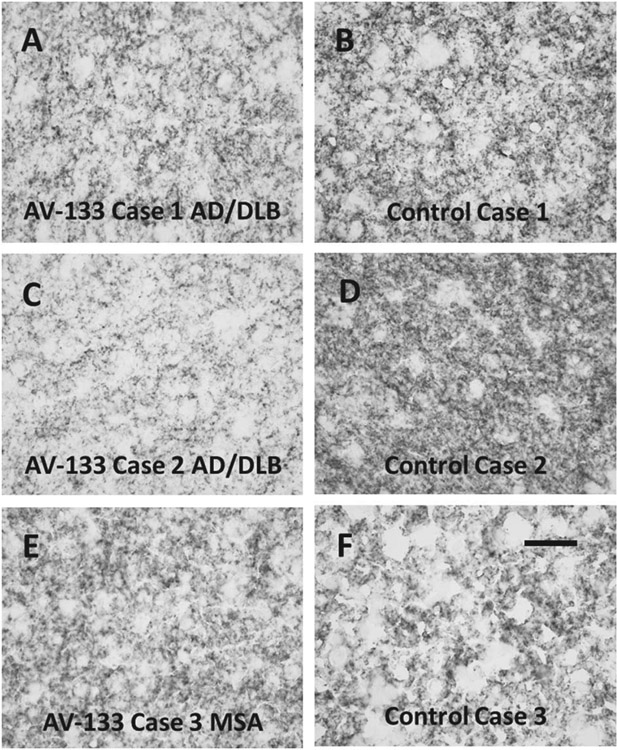

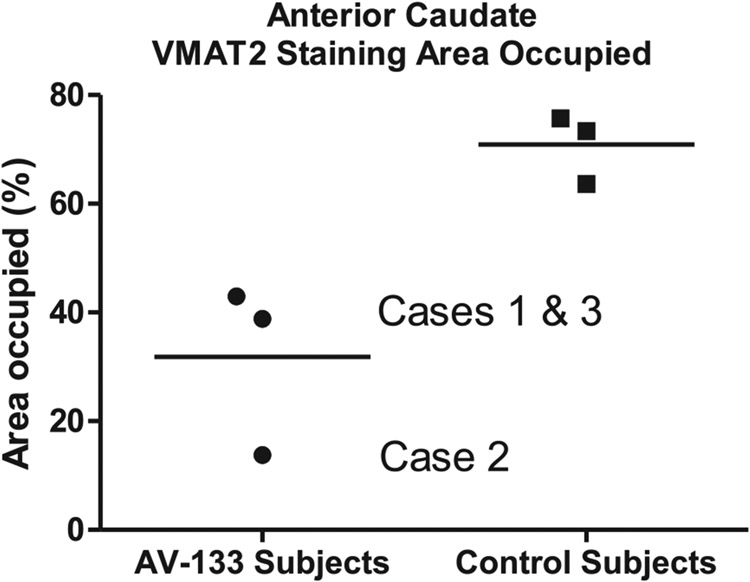

Sections of left anterior caudate nucleus from the three AV-133-imaged cases and three control subjects all showed dense punctate staining, consistent with dopaminergic presynaptic terminals originating from the substantia nigra (Fig. 2). Quantification of the area occupied by stained tissue elements showed decreased areas for the AV-133-imaged subjects (Fig. 3A, C, E) with diagnoses of AD/DLB (Cases 1 and 2; 38.8% and 13.8% area occupied, respectively) and MSA (Case 3; 60.6% area occupied), as compared to the three control subjects (Fig. 3B, D, F; mean 70.9% SD 6.4%.

Fig. 2.

Sections stained with an immunohistochemical method for VMAT2, showing the left anterior caudate nucleus from the three AV-133-imaged subjects (A, C, E) and three control subjects (B, D, F) without clinical dementia or parkinsonism. Scale bar (F) is 50 μm and serves for A–F.

Fig. 3.

Quantification of staining intensity in caudate nucleus sections stained with an immunohistochemical method for VMAT2, for the three AV-133-imaged subjects and three control subjects (B, D, F) without clinical dementia or parkinsonism.

DISCUSSION

These three cases, although insufficient as a statistical sample, demonstrate that functional imaging of dopaminergic neuronal systems with AV-133 holds promise for the clinical identification of DLB cases, although borderline cases may present difficulties. As in prior reports on DLB subjects with combined amyloid PET and dopaminergic imaging [19], all three subjects had increased cortical signal for AV-45, consistent with the presence of amyloid neuritic plaques, and neuropathological examination confirmed this, with all three subjects meeting intermediate or high ADNC criteria [16]. Clinicopathological concordance for AV-133 was not unanimous, however.

The first subject met clinical and neuropathological diagnostic criteria for DLB [20] and AV-133 PET imaging was read as having decreased striatal uptake consistent with dopaminergic degeneration. As the final clinicopathological diagnosis was also DLB, PET imaging confirmed the clinical diagnosis in this case.

At the time of PET imaging, the second subject was given a clinical diagnosis of AD without DLB. PET AV-45 imaging was read as positive for neocortical amyloid but AV-133 PET imaging was read by all 5 readers as being negative for dopaminergic degeneration. Subsequently, this patient developed rest tremor, visual hallucinations, and movement difficulties, and was diagnosed with DLB. The neuropathological diagnosis was AD and DLB. The AV-133 PET scan was therefore not consistent with the final clinical or neuropathological diagnoses.

The failure of some DLB subjects to show reduced striatal dopaminergic functional imaging has been previously reported by others and the underlying reason for the discrepancy may be due to lesser degrees of loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neuronal and nerve terminals in DLB as compared to PD [21-25]. The complete AV-133 clinical trial results, as previously reported, found that 3 of 11 subjects clinically diagnosed with DLB had a binary normal qualitative read and normal levels of striatal AV-133 uptake [13]. For our Case 2, 30 months had elapsed between AV-133 imaging and death, during which time dopaminergic degeneration would presumably have advanced, so that repeat AV-133 imaging more proximal to death may have been positive. Another possibility for these unexpected results may be due to persisting noradrenergic or serotonergic striatal innervation in some patients, as VMAT2 serves these neurotransmitter systems as well. The clinical failure to detect DLB is a well-known deficiency of current DLB diagnostic criteria, as up to 80% of autopsy-diagnosed DLB subjects are never diagnosed during life [4, 26]. It is possible that AV-133 could increase diagnostic sensitivity for DLB but the potential for this would require a larger autopsy-confirmed study.

The third subject met clinical criteria for probable DLB [18] and was found to have evidence of dopaminergic neuronal loss and amyloid deposition on PET imaging. On neuropathological examination, she was found to have pathognomonic features of MSA and AD. The concomitant pathology of MSA and AD is rare [27]. The cognitive deficits and parkinsonism seen in this case were likely due to a combination of these two separate pathologies, and PET imaging showed two different pathologies (AD and dopaminergic depletion) as well. Aside from PD and DLB, other disorders with striatal dopaminergic depletion include MSA, corticobasal degeneration (CBD), and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). Dopaminergic functional imaging identifies nigrostriatal degeneration but not the specific cause [28]. This subject had markedly asymmetric AV-133 striatal uptake that was matched by autopsy findings of markedly asymmetric striatal atrophy. A prior autopsy-confirmed study has reported increased striatal asymmetry of dopamine transporter binding in MSA as compared to PD, but this was not sufficiently distinct to provide a reliable differentiation of individual subjects [29].

This small clinicopathological series, although insufficient to be statistically evaluated, and subject to the selection bias that is unavoidable with autopsy studies, shows that AV-133 imaging may be useful for detecting striatal dopaminergic degeneration but may not be sensitive in subjects with early or mild loss and may not be able to distinguish between DLB and MSA. Prior published autopsy-confirmed work indicates that dopaminergic functional imaging ligands of other types cannot distinguish PD from DLB, PSP, CBD, and MSA [26]. The presence of amyloid pathology on PET imaging does not necessarily reflect clinical disease as positivity can be seen in cognitively normal individuals as well [10]. However, in the setting of dementia, a positive AV-45 scan is likely to be a highly sensitive and specific indicator that AD is at least one cause [9]. Since most autopsied cases of DLB concurrently meet neuropathological criteria for intermediate or high ADNC, but most subjects with DLB are clinically unrecognized, amyloid imaging in conjunction with a dopaminergic functional scan would likely increase both sensitivity and specificity for the dual diagnosis, since other causes of striatal dopaminergic depletion are either reliably separated by clinical criteria (e.g., PD versus DLB) or are much less prevalent, in neuropathological series, as concurrent diagnoses with AD (i.e., AD with DLB or PD is much more common than AD with PSP, CBD, or MSA).

The immunohistochemical comparison of VMAT2 staining in the AV-133-imaged subjects and three controls all showed decreased staining density in the diseased subjects as compared to the three controls, supporting 2 of 3 of the visual reads made by the clinical trial readers. The one discrepant read, as compared to the postmortem staining, may have been due to this subject having had the longest time interval between imaging and death, allowing progression of striatal dopaminergic terminal loss from non-apparent on PET imaging to obvious on immunohistochemical stains.

In summary, the findings in these three subjects show that PET imaging with AV-133 and AV-45 may be helpful in identifying underlying amyloid plaques and striatal dopaminergic degeneration co-existing in the same individual.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the subjects who have volunteered to participate in the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program. The authors thank members of the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium for helpful discussions, including Kathryn Davis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Banner Sun Health Research Institute (BSHRI) in Sun City, AZ and compliance with guidelines on human experimentation was followed.

The AV133-B03 study was sponsored by Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program has been supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901, and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium), the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, Sun Health Foundation and Mayo Clinic Foundation.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/20-0323r2).

REFERENCES

- [1].Villemagne VL, Okamura N, Pejoska S, Drago J, Mulligan RS, Chetelat G, O’Keefe G, Jones G, Kung HF, Pontecorvo M, Masters CL, Skovronsky DM, Rowe CC (2012) Differential diagnosis in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies via VMAT2 and amyloid imaging. Neurodegener Dis 10, 161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Adler CH, Beach TG, Hentz JG, Shill HA, Caviness JN, Driver-Dunckley E, Sabbagh MN, Sue LI, Jacobson SA, Belden CM, Dugger BN (2014) Low clinical diagnostic accuracy of early vs advanced Parkinson disease: Clinicopathologic study. Neurology 83, 406–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Beach TG, Monsell SE, Phillips LE, Kukull W (2012) Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005–2010. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 71, 266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Kryscio RJ, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Cooper G, Xu LO, Smith CD, Markesbery WR (2010) Low sensitivity in clinical diagnoses of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol 257, 359–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mosconi L, Berti V, Glodzik L, Pupi A, De Santi S, de Leon MJ (2010) Pre-clinical detection of Alzheimer’s disease using FDG-PET, with or without amyloid imaging. J Alzheimers Dis 20, 843–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Beach TG, Bedell BJ, Coleman RE, Doraiswamy PM, Fleisher AS, Reiman EM, Sabbagh MN, Sadowsky CH, Schneider JA, Arora A, Carpenter AP, Flitter ML, Joshi AD, Krautkramer MJ, Lu M, Mintun MA, Skovronsky DM, AV-45-A16 Study Group (2012) Cerebral PET with florbetapir compared with neuropathology at autopsy for detection of neuritic amyloid-beta plaques: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 11, 669–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Curtis C, Gamez JE, Singh U, Sadowsky CH, Villena T, Sabbagh MN, Beach TG, Duara R, Fleisher AS, Frey KA, Walker Z, Hunjan A, Holmes C, Escovar YM, Vera CX, Agronin ME, Ross J, Bozoki A, Akinola M, Shi J, Vandenberghe R, Ikonomovic MD, Sherwin PF, Grachev ID, Farrar G, Smith AP, Buckley CJ, McLain R, Salloway S (2015) Phase 3 trial of flutemetamol labeled with radioactive fluorine 18 imaging and neuritic plaque density. JAMA Neurol 72, 287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sabri O, Sabbagh MN, Seibyl J, Barthel H, Akatsu H, Ouchi Y, Senda K, Murayama S, Ishii K, Takao M, Beach TG, Rowe CC, Leverenz JB, Ghetti B, Ironside JW, Catafau AM, Stephens AW, Mueller A, Koglin N, Hoffmann A, Roth K, Reininger C, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Florbetaben Phase 3 Study Group (2015) Florbetaben PET imaging to detect amyloid beta plaques in Alzheimer’s disease: Phase 3 study. Alzheimers Dement 11, 964–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Beach TG, Schneider JA, Sue LI, Serrano G, Dugger BN, Monsell SE, Kukull W (2014) Theoretical impact of Florbetapir (18F) amyloid imaging on diagnosis of Alzheimer dementia and detection of preclinical cortical amyloid. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 73, 948–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Breteler MM (2011) Mapping out biomarkers for Alzheimer disease. JAMA 305, 304–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hefti FF, Kung HF, Kilbourn MR, Carpenter AP, Clark CM, Skovronsky DM (2010) (18)F-AV-133: A delective VMAT2-binding radiopharmaceutical for PET imaging of dopaminergic neurons. PET Clin 5, 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Okamura N, Villemagne VL, Drago J, Pejoska S, Dhamija RK, Mulligan RS, Ellis JR, Ackermann U, O’Keefe G, Jones G, Kung HF, Pontecorvo MJ, Skovronsky D, Rowe CC (2010) In vivo measurement of vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 density in Parkinson disease with (18)F-AV-133. J Nucl Med 51, 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Siderowf A, Pontecorvo MJ, Shill HA, Mintun MA, Arora A, Joshi AD, Lu M, Adler CH, Galasko D, Liebsack C, Skovronsky DM, Sabbagh MN (2014) PET imaging of amyloid with Florbetapir F 18 and PET imaging of dopamine degeneration with 18F-AV-133 (florbenazine) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body disorders. BMC Neurol 14, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, Cummings J, Duda JE, Lippa C, Perry EK, Aarsland D, Arai H, Ballard CG, Boeve B, Burn DJ, Costa D, Del Ser T, Dubois B, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Goetz CG, Gomez-Tortosa E, Halliday G, Hansen LA, Hardy J, Iwatsubo T, Kalaria RN, Kaufer D, Kenny RA, Korczyn A, Kosaka K, Lee VM, Lees A, Litvan I, Londos E, Lopez OL, Minoshima S, Mizuno Y, Molina JA, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Pasquier F, Perry RH, Schulz JB, Trojanowski JQ, Yamada M, Consortium on DLB (2005) Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 65, 1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr., Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Serrano G, Shill HA, Walker DG, Lue L, Roher AE, Dugger BN, Maarouf C, Birdsill AC, Intorcia A, Saxon-Labelle M, Pullen J, Scroggins A, Filon J, Scott S, Hoffman B, Garcia A, Caviness JN, Hentz JG, Driver-Dunckley E, Jacobson SA, Davis KJ, Belden CM, Long KE, Malek-Ahmadi M, Powell JJ, Gale LD, Nicholson LR, Caselli RJ, Woodruff BK, Rapscak SZ, Ahern GL, Shi J, Burke AD, Reiman EM, Sabbagh MN (2015) Arizon a Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders and Brain and Body Donation Program. Neuropathology 35, 354–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Beach TG, Adler CH, Lue L, Sue LI, Bachalakuri J, Henry-Watson J, Sasse J, Boyer S, Shirohi S, Brooks R, Eschbacher J, White CL 3rd, Akiyama H, Caviness J, Shill HA, Connor DJ, Sabbagh MN, Walker DG, Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium (2009) Unified staging system for Lewy body disorders: Correlation with nigrostriatal degeneration, cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction. Acta Neuropathol 117, 613–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mirra SS, Nelson PT, Schneider JA, Thal DR, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Hyman BT, National Institute on Aging; Alzheimer’s Association (2012) National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: Apractical approach. Acta Neuropathol 123, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shirvan J, Clement N, Ye R, Katz S, Schultz A, Johnson KA, Gomez-Isla T, Frosch M, Growdon JH, Gomperts SN (2019) Neuropathologic correlates of amyloid and dopamine transporter imaging in Lewy body disease. Neurology 93, e476–e484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Halliday G, Taylor JP, Weintraub D, Aarsland D, Galvin J, Attems J, Ballard CG, Bayston A, Beach TG, Blanc F, Bohnen N, Bonanni L, Bras J, Brundin P, Burn D, Chen-Plotkin A, Duda JE, El-Agnaf O, Feldman H, Ferman TJ, Ffytche D, Fujishiro H, Galasko D, Goldman JG, Gomperts SN, Graff-Radford NR, Honig LS, Iranzo A, Kantarci K, Kaufer D, Kukull W, Lee VMY, Leverenz JB, Lewis S, Lippa C, Lunde A, Masellis M, Masliah E, McLean P, Mollenhauer B, Montine TJ, Moreno E, Mori E, Murray M, O’Brien JT, Orimo S, Postuma RB, Ramaswamy S, Ross OA, Salmon DP, Singleton A, Taylor A, Thomas A, Tiraboschi P, Toledo JB, Trojanowski JQ, Tsuang D, Walker Z, Yamada M, Kosaka K (2017) Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 89, 88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Walker Z, Jaros E, Walker RW, Lee L, Costa DC, Livingston G, Ince PG, Perry R, McKeith I, Katona CL (2007) Dementia with Lewy bodies: A comparison of clinical diagnosis, FP-CIT single photon emission computed tomography imaging and autopsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78, 1176–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zaccai J, Brayne C, McKeith I, Matthews F, Ince PG, MRC Cognitive Function, Ageing Neuropathology Study (2008) Patterns and stages of alpha-synucleinopathy: Relevance in a population-based cohort. Neurology 70, 1042–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Colloby SJ, McParland S, O’Brien JT, Attems J (2012) Neuropathological correlates of dopaminergic imaging in Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementias. Brain 135, 2798–2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Beach TG, Walker DG, Sue LI, Newell A, Adler CC, Joyce JN (2004) Substantia nigra Marinesco bodies are associated with decreased striatal expression of dopaminergic markers. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 63, 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Burke JF, Albin RL, Koeppe RA, Giordani B, Kilbourn MR, Gilman S, Frey KA (2011) Assessment of mild dementia with amyloid and dopamine terminal positron emission tomography. Brain 134, 1647–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Malek-Ahmadi M, Beach TG, Zamrini E, Adler CH, Sabbagh MN, Shill HA, Jacobson SA, Belden CM, Caselli RJ, Woodruff BK, Rapscak SZ, Ahern GL, Shi J, Caviness JN, Driver-Dunckley E, Mehta SH, Shprecher DR, Spann BM, Tariot P, Davis KJ, Long KE, Nicholson LR, Intorcia A, Glass MJ, Walker JE, Callan M, Curry J, Cutler B, Oliver J, Arce R, Walker DG, Lue LF, Serrano GE, Sue LI, Chen K, Reiman EM (2019) Faster cognitive decline in dementia due to Alzheimer disease with clinically undiagnosed Lewy body disease. PLoS One 14, e0217566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dugger BN, Adler CH, Shill HA, Caviness J, Jacobson S, Driver-Dunckley E, Beach TG, Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium (2014) Concomitant pathologies among a spectrum of parkinsonian disorders. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 20, 525–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kraemmer J, Kovacs GG, Perju-Dumbrava L, Pirker S, Traub-Weidinger T, Pirker W (2014) Correlation of striatal dopamine transporter imaging with post mortem substantia nigra cell counts. Mov Disord 29, 1767–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Perju-Dumbrava LD, Kovacs GG, Pirker S, Jellinger K, Hoffmann M, Asenbaum S, Pirker W (2012) Dopamine transporter imaging in autopsy-confirmed Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord 27, 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]