Abstract

Background and study aims For distal malignant biliary obstruction, self-expandable metallic stents (SEMSs) have a larger inner diameter compared to plastic stents, which prolongs time to recurrent biliary obstruction (TRBO), although stent-related complications are still a problem. This study aimed to compare the outcomes between using 10– and 6-mm-diameter fully-covered SEMS (FCSEMS) for distal malignant biliary obstruction.

Patients and methods This single-center, retrospective study included patients with 10-mm or 6-mm-diameter FCSEMS to treat distal malignant biliary obstruction. Clinical success, stent-related adverse events (AEs), cumulative incidence of RBO, factors involved in stent-related AEs, and factors involved in RBO were evaluated.

Results There were 243 eligible cases between October 2017 and December 2021. The cumulative incidence of RBO did not differ significantly between the 10-mm and 6-mm groups. Stent-related AEs occurred in 31.6 % and 11.4 % of patients between the 10-mm and 6-mm groups, respectively ( P < 0.01). Pancreatitis occurred in 10.5 % and 3.6 % ( P = 0.04) and cholecystitis occurred in 11.8 % and 3.0 % of patients ( P = 0.03) in the 10-mm and 6-mm groups, respectively. In multivariate analysis, the 6-mm stent was extracted as a factor linked to a reduced risk of AEs, but not as a risk factor of RBO.

Conclusions The 6-mm-diameter FCSEMS for distal malignant biliary obstruction is a well-balanced stent with a cumulative incidence of RBO compatible to that of the 10-mm-diameter FCSEMS and fewer stent-related AEs.

Introduction

The main methods of biliary drainage to treat distal malignant biliary obstruction (DMBO) are endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). A self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) is recommended for both preoperative and non-resection cases 1 2 3 4 5 6 for DMBO, with the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommending the use of 10-mm-diameter SEMSs for DMBO 1 . A SEMS has the advantage of a longer time to recurrent biliary obstruction (TRBO) compared to a plastic stent (PS). However, the expansion force of SEMSs leads to stent-related adverse events (AEs), such as pancreatitis and cholecystitis 2 4 6 7 8 9 . The prevalence of stent-related AEs with SEMSs has been reported to be 1.5 % to 8.8 % for pancreatitis and 1.5 % to 10.0 % for cholecystitis 10 11 12 13 . The major problem is that these stent-related AEs may delay or stop treatment of the primary disease. In general, TRBO is thought to increase in proportion to the diameter of the stent 14 15 . However, a larger inner stent diameter can cause overexpansion of the bile duct, which may lead to an increase in stent-related AEs, such as cholecystitis and pancreatitis 16 . In other words, there is a trade-off between TRBO and stent-related AEs, and the optimal stent diameter for DMBO is still debated.

Several studies have reported on TRBO and stent-related AEs based on stent diameter. The following outcomes have been reported for 10-mm-diameter SEMS: TRBO, 240 to 385 days 10 16 17 , stent-related AEs, 7.2 % to 20.0 % 2 4 5 10 16 17 18 . The results for the 12-mm-diameter FCSEMS 14 and 14-mm-diameter uncovered SEMS 19 showed median TRBOs of 184 and 190 days with rates of stent-related AEs of 21.1 % and 28.9 %, respectively. In previous reports, there was no difference in TRBO between a larger-diameter stent and 10-mm-diameter FCSEMS, and stent-related AEs were more common with larger diameters. However, a prospective study compared the outcomes of 8-mm- and 10-mm-diameter FCSEMS with the aim of reducing AEs 16 . The results showed no significant difference in median TRBO between the 8-mm and 10-mm groups (275 and 293 days, respectively; P = 0.97), and there was no significant difference in the incidences of pancreatitis (4.1 and 10.0 %, respectively; P = 0.10) and cholecystitis (6.0 and 10.2 %, respectively; P = 0.28). In other words, the non-inferiority of the 8-mm-diameter FCSEMS compared to the 10-mm-diameter FCSEMS in TRBO was demonstrated, and there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of incident cases.

In the present study, the usefulness of the 6-mm-diameter FCSEMS was compared retrospectively with that of the 10-mm-diameter FCSEMS, the standard treatment. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports comparing the results of the 6-mm and 10-mm-diameter FCSEMS for DMBO.

Patients and methods

Ethics statements

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center Hospital, Japan (2018–149).

Study design and patients

This study was a single-center, retrospective study. Cases of FCSEMS deployed in a transpapillary fashion initially for DMBO at our hospital between October 2017 and December 2021 were retrieved from the ERCP database. The main eligibility criteria for this study were as follows: (1) DMBO; (2) initial FCSEMS deployment (cases where an FCSEMS was deployed for initial drainage or after PS or endoscopic nasobiliary drainage); and (3) FCSEMS placement across the papilla. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) cases with an 8-mm-diameter SEMS; (2) cases with FCSEMS placement above the papilla; and (3) cases with an additional PS within the FCSEMS.

Procedure

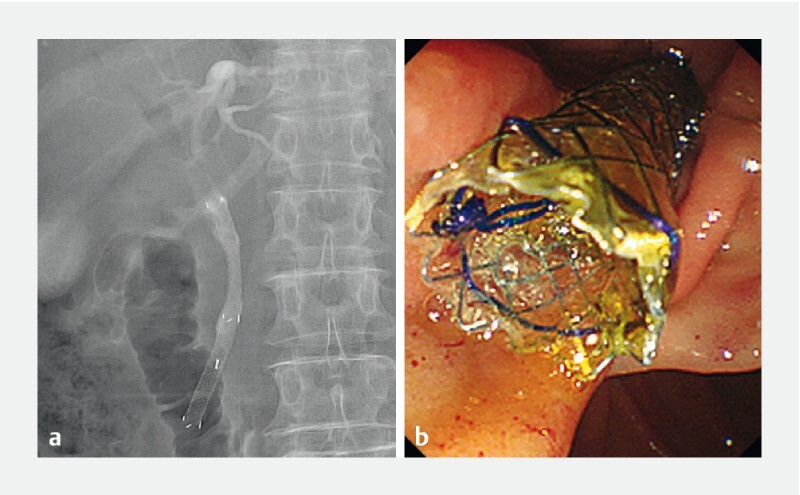

We pre-evaluated bile duct confluence morphology using computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. The length of bile duct stenosis was measured using the catheter or guidewire to determine the length of the FCSEMS. Regarding the choice of stent diameter, a 10-mm-diameter stent was mainly used until August 2019, and a 6-mm-diameter stent ( Fig. 1 ) was primarily used after September 2019. Both the 6-mm and the 10-mm-diameter stents used were braided-type FCSEMSs. The same diameter of SEMS was selected for each period strategically, and not at random. In this study, all cases underwent transpapillary stenting by the side-view endoscope; hence, no cases of metallic stenting for Billroth II or Roux-en-Y reconstruction were included.

Fig. 1.

The 6-mm-diameter, fully-covered, self-expandable metallic stent (HANAROSTENT; Boston Scientific, Tokyo, Japan) placement for distal biliary obstruction under endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; a fluoroscopic X-ray imaging; and b endoscopic imaging.

Definitions

The endpoints were the clinical success rate, procedure time, percentage of AEs, cumulative incidence of recurrent biliary obstruction (RBO), factors involved in stent-related AEs (pancreatitis and cholecystitis), and factors involved in RBO. These endpoints are defined as follows in accordance with the Tokyo criteria 2014 20 . The clinical success rate was defined as the percentage of patients with total bilirubin normalization or reduction by ≥ 50.0 % within 2 weeks of stent placement. RBO was defined as stent occlusion and migration (only if bile duct obstruction symptoms were present). TRBO was defined as the period between stent placement and RBO (death was censored). Pancreatitis was defined as cases with (1) new or worsened abdominal pain; (2) new or prolonged hospitalization for at least 2 days; and (3) serum amylase ≥ 3-fold the upper limit of normal, measured > 24 hours after procedure. Cholecystitis was defined as fever > 38 °C or right upper abdominal pain occurring with supportive imaging study findings. The procedure time was defined as the time from the frontal view of the papilla to stent deployment. The bile duct stenosis length, pancreatic duct dilation, and parenchyma length were measured using CT.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables, such as age and procedure time, are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze these data. Categorical variables are presented as ratios and were analyzed using the Fischer exact test. Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze factors involved in pancreatitis and cholecystitis. Cumulative incidence of RBO was calculated, treating death or surgery as a competing risk, and compared by the Gray’s test. Fine-Gray Sub-distribution hazard regression analysis was used to analyze factors involved in RBO. In Fine-Gray sub-distribution hazard regression (SHR) and logistic regression analyzes, the medians of all continuous variables were changed to binary variables as the reference value in the analysis. In logistic regression analyzes for AEs, factors with P < 0.20 were included in multivariate analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using R software, version 4.2.1 (R Core Development Team: http://www.r-project.org) and SPSS Statistics (version 23; IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, United States).

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

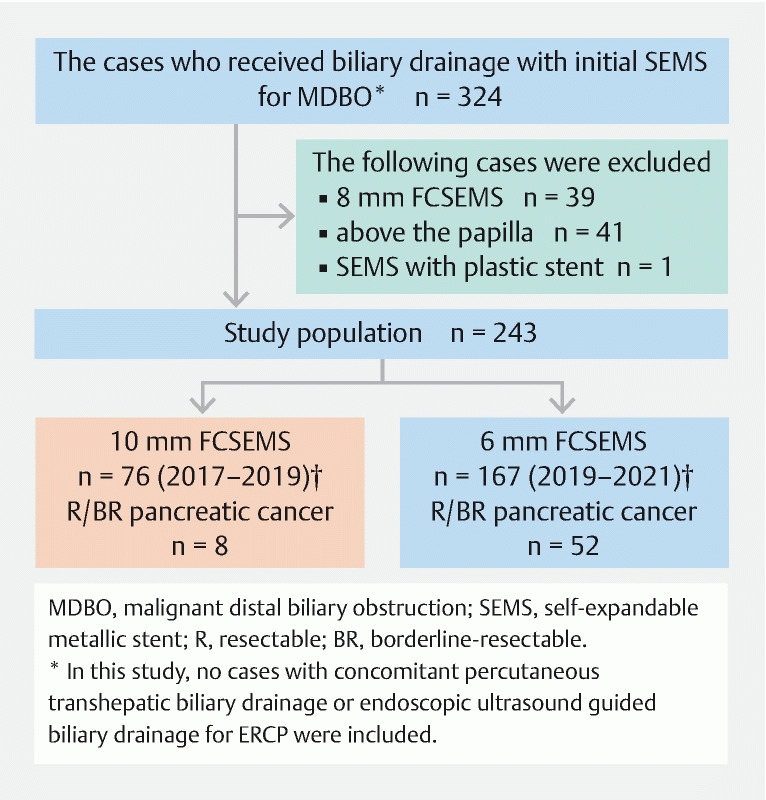

Of 324 cases of initial FCSEMS placement for DMBO, 243 cases were eligible ( Fig. 2 ). Among the 243 eligible cases, there were 76 and 167 cases in the 10-mm and 6-mm groups, respectively. There were more resectable/borderline resectable pancreatic cancers ( P < 0.01) and higher total bilirubin values ( P < 0.01) in the 6-mm group than in the 10-mm group. There were no significant differences in cases of biliary drainage before SEMS placement ( P = 0.68) or cases of orifice of the cystic duct invasion ( P = 0.38) between the groups ( Table 1 ).

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of patients in the current study showing results of inclusion and details of the 10-mm and 6-mm groups.

Table 1. Patient baseline characteristics.

| FCSEMS | ||||

| Patient characteristics | Total n = 243 | 10-mm n = 76 | 6-mm n = 167 | P value |

| Age, years | 68 (57–75) | 68 (57–72) | 68 (58–75) | 0.41 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 104 (42.8) | 34 (44.7) | 70 (41.9) | 0.78 |

| Causes of distal biliary obstruction, n (%) | ||||

| Pancreatic cancer | 186 (76.5) | 58 (76.3) | 128 (76.6) | 0.87 |

| R/BR | 60 (24.7) | 8 (10.5) | 52 (31.1) | < 0.01 |

| UR | 126 (51.9) | 50 (65.8) | 76 (45.5) | < 0.01 |

| Other cancers | 57 (23.5) | 18 (23.7) | 39 (23.4) | 0.87 |

| Previous biliary drainage, n (%) | 106 (43.6) | 35 (46.1) | 71 (42.5) | 0.68 |

| Previous cholecystectomy, n (%) | 17 (7.0) | 5 (6.6) | 12 (7.2) | 1.00 |

| Laboratory data before ERCP | ||||

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 2.3 (1.2–6.0) | 1.7 (1.0–3.9) | 2.8 (1.3–6.8) | < 0.01 |

| Amylase, U/L | 68.0 (44.5–111.0) | 112.0 (58.0–308.0) | 96.0 (54.0–196.8) | 0.18 |

| Main pancreatic duct opacification, n (%) | 111 (45.7) | 25 (32.9) | 86 (51.5) | < 0.01 |

| Diameter of each duct, mm | ||||

| Common bile duct | 12.0 (9.0–14.9) | 11.8 (8.8–13.5) | 12.5 (9.3–15.7) | 0.29 |

| Main pancreatic duct | 4.7 (2.8–6.6) | 4.9 (3.2–7.0) | 4.4 (2.6–6.2) | 0.25 |

| Diameter of the pancreatic body, mm | 16.5 (13.0–20.5) | 17.2 (13.0–20.8) | 16.0 (13.1–20.1) | 0.52 |

| Length of the biliary stricture, mm | 27.0 (23.7–31.0) | 27.0 (20.0–33.0) | 26.5 (24.0–34.3) | 0.77 |

| Duodenal stent 1 , n (%) | 6 (2.5) | 2 (2.6) | 4 (2.4) | 1.00 |

| Site of tumor invasion, n (%) | ||||

| OCD | 27 (11.1) | 6 (7.9) | 21 (12.6) | 0.38 |

| Duodenal papilla | 16 (6.6) | 5 (6.6) | 11 (6.6) | 1.00 |

| Duodenum 2 | 10 (4.1) | 6 (7.9) | 4 (2.4) | 0.08 |

| Therapy for malignancy, n (%) | ||||

| Chemotherapy 3 | 189 (77.8) | 64 (84.2) | 125 (71.0) | 0.13 |

| Best supportive care | 17 (7.0) | 6 (7.9) | 11 (6.6) | 0.79 |

| Observation period, day | 79 (35–166) | 118 (39–219) | 70 (34–132) | 0.03 |

Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range).

R, resectable; BR, borderline resectable; UR, unresectable; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; OCD, orifice of the cystic duct; FCSEMS, fully covered self-expandable metallic stent.

Duodenal stent cases were limited to those with stent placement within the TRBO (median) period calculated for all cases.

Excluding cases of duodenal papillary infiltration.

Excluding preoperative chemotherapy cases that underwent surgery.

Procedure details

Cases of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs before ERCP and stent length as long as 8 cm were significantly more common in the 6-mm group than in the 10-mm group. There were no significant differences in the method of bile duct canulation, cases of pancreatic duct stenting, and procedure time between the groups ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Procedure details.

| FCSEMS | ||||

| Procedure details | Total n = 243 | 10-mm n = 76 | 6-mm n = 167 | P value |

| NSAIDs used before ERCP, n (%) | 203 (83.5) | 51 (67.1) | 152 (91.0) | < 0.01 |

| Canulation method, n (%) | ||||

|

193 (79.4) | 60 (78.9) | 133 (79.6) | 0.98 |

|

39 (16.0) | 13 (17.1) | 26 (15.6) | |

|

8 (3.3) | 2 (2.6) | 6 (3.6) | |

|

3 (1.2) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (1.2) | |

|

238 (97.9) | 75 (98.7) | 163 (97.6) | 1.00 |

|

72 (29.6) | 20 (26.3) | 52 (31.1) | 0.55 |

|

16 (6.6) | 3 (3.9) | 13 (7.8) | 0.40 |

|

27 (17–36) | 23.5 (17–34) | 27 (20–38) | 0.11 |

| FCSEMs length, n (%) | ||||

|

59 (24.3) | 52 (68.4) | 7 (4.2) | < 0.01 |

|

167 (68.7) | 24 (31.6) | 143 (85.6) | < 0.01 |

|

16 (6.6) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (9.6) | < 0.01 |

|

1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1.00 |

Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range).

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EST, endoscopic sphincterotomies; FCSEMS, fully-covered self-expandable metallic stent.

Clinical outcomes

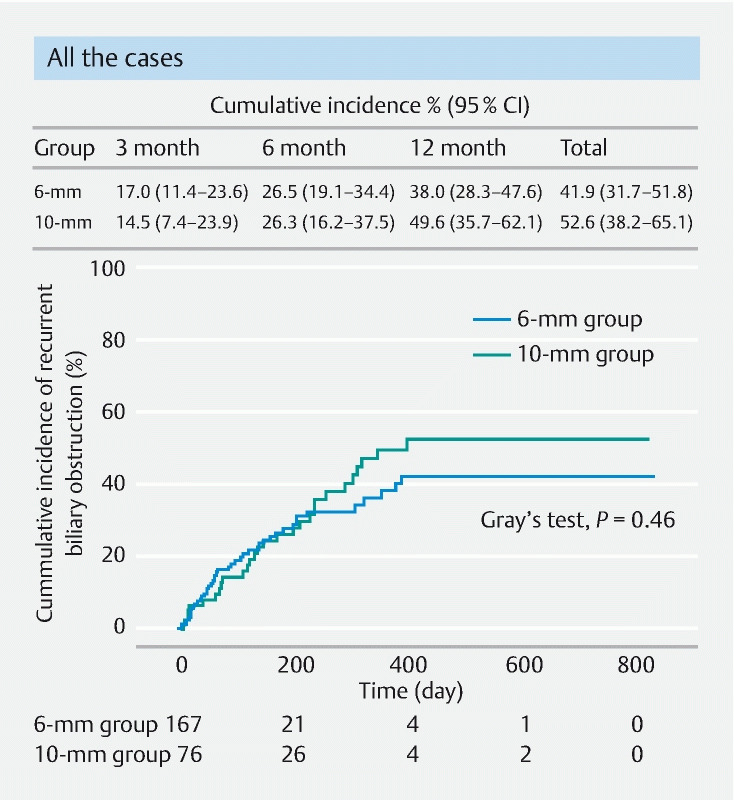

Clinical success rates were 94.7 % and 92.8 % ( P = 0.78) in the 10-mm and 6-mm groups, respectively, with no significant difference. The median observation period (IQR) was 233 days (91–438 days), and RBO occurred in 74 patients (30.4 %) during the observation period (38.2 % and 26.9 % in the 10-mm and 6-mm groups, respectively; P = 0.10). Regarding details of RBO, rates of migration and obstruction cases were 7.9 % and 14.4 % ( P = 0.10) and 30.3 % and 12.6 % ( P < 0.01) in the 10-mm and 6-mm groups, respectively ( Table 3 ). Cumulative incidence of RBO in all cases was 14.5 % versus 17.0 %, 26.3 % versus 26.5 %, and 49.6 % versus 38.0 % at 3, 6, and 12 months ( P = 0.46 by Gray’s test) in the 10-mm versus 6-mm groups, respectively ( Fig. 3 ). Adverse events occurred in 43 cases (17.7 %) overall, and the incidence of AEs was significantly less in the 6-mm group than in the 10-mm group (11.4 % versus 31.6 %; P < 0.01). Pancreatitis occurred in 10.5 % and 3.6 % of patients and cholecystitis occurred in 11.8 % and 3.0 % of patients in the 10-mm and 6-mm groups, respectively; both AEs occurred significantly less in the 6-mm group than in the 10-mm group ( P = 0.04 and P = 0.03, respectively). Other AEs were not significantly different between the groups ( Table 3 ). In summary, the 6-mm group showed no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of RBO of all cases and significantly fewer stent-related AEs compared to the 10-mm group.

Table 3. Clinical outcomes in all patients.

| FCSEMS | ||||

| Clinical outcomes | Total n = 243 | 10-mm n = 76 | 6-mm n = 167 | P value |

| Clinical success, n (%) | 227 (93.4) | 72 (94.7) | 155 (92.8) | 0.78 |

| RBO, n (%) | 74 (30.4) | 29 (38.2) | 45 (26.9) | 0.10 |

| Migration | 30 (12.3) | 6 (7.9) | 24 (14.4) | 0.10 |

| Obstruction | 44 (18.1) | 23 (30.3) | 21 (12.6) | < 0.01 |

| Debris | 28 (11.5) | 14 (18.4) | 14 (8.4) | 0.03 |

| Food impaction | 7 (2.9) | 2 (2.6) | 5 (3.0) | 1.00 |

| Kinking | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1.00 |

| Overgrowth | 7 (2.9) | 6 (7.9) | 1 (0.6) | < 0.01 |

| Hyperplasia | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 |

| Total adverse events, n (%) | 43 (17.7) | 24 (31.6) | 19 (11.4) | < 0.01 |

| Pancreatitis | 14 (5.8) | 8 (10.5) | 6 (3.6) | 0.04 |

| Cholecystitis | 14 (5.8) | 9 (11.8) | 5 (3.0) | 0.03 |

| Non-occlusion cholangitis | 10 (4.1) | 4 (5.3) | 6 (3.6) | 1.00 |

| Liver abscess | 5 (2.1) | 3 (3.9) | 2 (1.2) | 1.00 |

RBO, recurrent biliary obstruction; FCSEMS, fully covered self-expandable metallic stent.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative incidence of recurrent biliary obstruction in all cases in the 10-and 6-mm groups was analyzed, treating surgery and death as a competing risk, and compared with the Gray’s test. There was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of RBO between either group ( P = 0.46). CI, confidence interval.

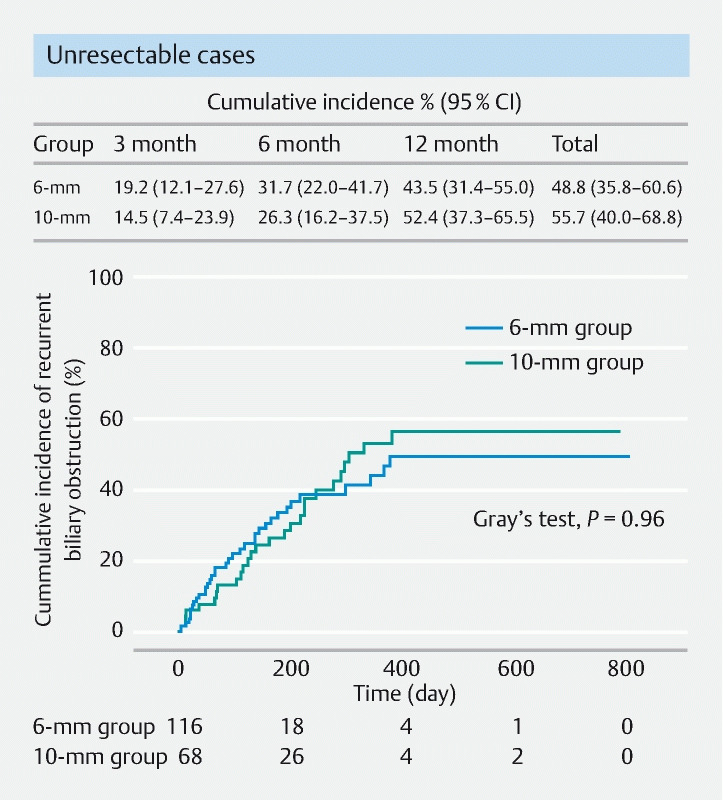

In patients with preoperative pancreatic cancer (resectable/borderline resectable cases), the incidence of total AEs was 37.5 % and 7.7 % in the 10-mm and 6-mm groups, respectively, and the incidence was significantly lower in the 6-mm group than in the 10-mm group ( P = 0.04). Pancreatitis occurred in 25.0 % and 3.8 % of patients ( P = 0.08) and cholecystitis occurred in 12.5 % and 0.0 % of patients ( P = 0.13) in the 10-mm and 6-mm groups, respectively. The median time to surgery was 83 days (IQR 42–142 days), with no significant difference between the groups. The non-RBO rates within this period were 75.0 % and 80.8 % ( P = 0.66) in the 10-mm and 6-mm groups, respectively, with no significant difference between the groups ( Table 4 ). Furthermore, in unresectable cases (68 and 115 in the 10-mm versus 6-mm groups, respectively), the cumulative incidence of RBO was 14.5 % versus 19.2 %, 26.3 % versus 31.7 %, and 52.4 % versus 43.5 % at 3, 6, and 12 months ( P = 0.96 by Gray’s test) ( Fig. 4 ).

Table 4. Clinical outcomes in patients with preoperative pancreatic cancer (resectable and borderline-resectable cases).

| FCSEMS | ||||

| Clinical outcomes | Total n = 60 | 10-mm n = 8 | 6-mm n = 52 | P value |

| Surgeries performed, n (%) | 37 (61.7) | 6 (75.0) | 31 (59.6) | 0.70 |

| Time to surgery, day | 83 (42–142) | 83 (41–152) | 83 (50–134) | 0.94 |

| Non-RBO rate, n (%) | 48 (80.0) | 6 (75.0) | 42 (80.8) | 0.70 |

| Total adverse events, n (%) | 7 (11.7) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (7.7) | 0.04 |

| Pancreatitis | 4 (6.7) | 2 (25.0) | 2 (3.8) | 0.08 |

| Cholecystitis | 1 (1.7) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.13 |

| Non-occlusion cholangitis | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.8) | 1.00 |

Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range).

RBO, recurrent biliary obstruction; FCSEMS, fully covered self-expandable metallic stent.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative incidence of recurrent biliary obstruction of unresectable cases in 10-and 6-mm groups was analyzed, treating surgery and death as a competing risk and compared with the Gray’s test. There was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of RBO between either group ( P = 0.96). CI, confidence interval.

Risk factors for total adverse events, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, and RBO

Results of univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors involved in total AEs, pancreatitis, and cholecystitis are shown in Table 5 . For total AEs, 6-mm FCSEMS (odds ratio [OR], 0.18; 95 % confidence interval [CI], 0.07–0.46; P < 0.01) was extracted as an independent risk-reducing factor. For pancreatitis, 6-mm FCSEMS (OR, 0.30; 95 % CI, 0.10–0.96; P = 0.04) was similarly extracted as an independent risk-reducing factor. However, the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was not extracted as a risk-reducing factor. For cholecystitis, 6-mm FCSEMS (OR, 0.13; 95 % CI, 0.03–0.61; P = 0.01) was an independent risk-reducing factor, and tumor invasion to the orifice of the cystic duct (OR, 9.90; 95 % CI, 2.62–37.3; P < 0.01) was extracted as an independent risk factor. Thus, 6-mm FCSEMS was extracted as an independent risk-reducing factor for total AEs, pancreatitis, and cholecystitis. The results of univariate and multivariate analyses of factors involved in RBO are shown in Table 6 . Resectable/borderline resectable cases were extracted as an independent risk-reducing factor for RBO (SHR, 2.59; 95 % CI, 1.26–5.32; P < 0.01). However, 6-mm FCSEMS was not extracted as a risk factor for RBO (SHR, 1.30; 95 % CI, 0.48-3.50; P = 0.61).

Table 5. Univariate and multivariate analyses for risk factors for adverse events.

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||||

| Risk factors | n | Event | OR | 95 % CI | P value | OR | 95 % CI | P value | |

| Total adverse events | |||||||||

| Pancreatic cancer | Yes | 186 | 34 | 1.23 | 0.55–2.73 | 0.62 | |||

| Previous biliary drainage | Yes | 106 | 20 | 1.15 | 0.60–2.23 | 0.67 | |||

| NSAIDs use before ERCP | Yes | 203 | 34 | 0.69 | 0.30–1.60 | 0.39 | |||

| Stent length | ≥ 8 cm | 184 | 28 | 0.53 | 0.26–1.07 | 0.08 | 1.69 | 0.65–4.43 | 0.28 |

| Stent diameter | 6 mm | 167 | 19 | 0.28 | 0.14–0.55 | < 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.07–0.46 | < 0.01 |

| Pancreatitis | |||||||||

| Female sex | Yes | 104 | 5 | 0.73 | 0.24–2.24 | 0.58 | |||

| Pancreatic cancer | Yes | 186 | 10 | 0.77 | 0.23–2.56 | 0.67 | |||

| Previous biliary drainage | Yes | 106 | 4 | 0.50 | 0.15–1.63 | 0.25 | |||

| Diameter of the pancreatic body | ≥ 16.5 mm | 93 | 6 | 1.19 | 0.35–4.03 | 0.78 | |||

| Main pancreatic duct opacification | Yes | 111 | 9 | 2.24 | 0.73–6.90 | 0.16 | 2.96 | 0.92–9.50 | 0.07 |

| NSAIDs use before ERCP | Yes | 203 | 11 | 0.71 | 0.19–2.66 | 0.61 | |||

| PGW | Yes | 39 | 4 | 2.22 | 0.66–7.47 | 0.20 | |||

| Stent diameter | 6 mm | 167 | 6 | 0.32 | 0.10–0.95 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.07–0.82 | 0.02 |

| Cholecystitis | |||||||||

| Previous biliary drainage | Yes | 106 | 6 | 0.97 | 0.33–2.88 | 0.95 | |||

| Tumor invasion to the OCD | Yes | 27 | 6 | 7.43 | 2.35–23.5 | < 0.01 | 11.30 | 3.10–41.2 | < 0.01 |

| OCD occluded by the stent | Yes | 162 | 10 | 1.27 | 0.39–4.20 | 0.69 | |||

| Stent length | ≥ 8 cm | 184 | 8 | 0.40 | 1.21–1.32 | 0.11 | 1.22 | 0.28–5.39 | 0.80 |

| Stent diameter | 6-mm | 167 | 5 | 0.23 | 0.07–0.71 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.03–0.65 | 0.01 |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; PGW, pancreatic duct guidewire technique; OCD, orifice of the cystic duct; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 6. Univariate and multivariate analyses for factors involved in time to recurrent biliary obstruction.

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||||

| Factors | n | Event | SHR | 95 % CI | P value | SHR | 95 % CI | P value | |

| Pancreatic cancer | Yes | 186 | 58 | 1.29 | 0.74–2.22 | 0.37 | 1.45 | 0.79–2.66 | 0.24 |

| Resectable/borderline resectable status | Yes | 60 | 12 | 0.48 | 0.25–0.92 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.19–0.78 | < 0.01 |

| Chemotherapy | Yes | 189 | 69 | 4.9 | 0.65–37.5 | 0.12 | 4.65 | 0.62–36.4 | 0.13 |

| Duodenal stent 1 | Yes | 6 | 2 | 0.92 | 0.21–4.03 | 0.91 | 1.20 | 0.25–5.85 | 0.82 |

| Diameter of the common bile duct | ≥ 12 mm | 157 | 44 | 1.05 | 0.66–1.65 | 0.85 | 1.16 | 0.72–1.86 | 0.55 |

| Length of the biliary stricture | ≥ 27 mm | 154 | 41 | 0.83 | 0.53–1.30 | 0.40 | 0.80 | 0.50–1.28 | 0.35 |

| Tumor invasion to the duodenal papilla | Yes | 16 | 6 | 1.31 | 0.59–2.88 | 0.51 | 1.05 | 0.45–2.42 | 0.92 |

| Tumor invasion to the duodenum 2 | Yes | 10 | 3 | 0.76 | 0.25–2.28 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.19–1.72 | 0.32 |

| Stent length | ≥ 8 cm | 184 | 46 | 0.63 | 0.40–0.99 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.24–1.77 | 0.41 |

| Stent diameter | 6-mm | 167 | 44 | 0.79 | 0.50–1.29 | 0.29 | 1.30 | 0.48–3.48 | 0.61 |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; SHR, sub-distribution hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Duodenal stent cases were limited to those with stent placement within the TRBO (median) period calculated for all cases.

Excluding cases of duodenal papillary infiltration.

Discussion

This study compared outcomes of using 10-mm and 6-mm FCSEMS for DMBO. Stent-related AEs were significantly less frequent in the 6-mm group than in the 10-mm group, and cumulative incidence of RBO was not significantly different between the groups. In addition, 6-mm FCSEMS was identified as an independent factor associated with a reduced risk of total AEs, pancreatitis, and cholecystitis. Hence, the 6-mm FCSEMS may be a safe, well-balanced, and useful stent that can ensure longer TRBO.

Clinically problematic stent-related AEs include pancreatitis and cholecystitis. In previous reports, the risk factors for pancreatitis were pancreatography 21 , volume preservation of the pancreatic parenchyma 22 23 , and high axial force SEMS 24 , whereas the risk factors for cholecystitis were tumor invasion into the orifice of the cystic duct 25 and FCSEMS placement 26 . In terms of the inner diameter of SEMSs, 8-mm 16 22 , 10-mm 2 4 5 10 16 18 , and 12-mm 14 27 diameters are reported; however, none of these reports examined factors related to the stent diameter. Nevertheless, reducing the stent diameter to 8 mm 16 does not reduce the risk of stent-related complications. In the present study, 6-mm FCSEMS was extracted as the first risk-reducing factor for pancreatitis and cholecystitis. A 6-mm FCSEMS is a slim stent that approximates the physiologic diameter of the common bile duct, which minimizes bile duct overexpansion and reduces pressure to the duodenal papilla and the orifice of the cystic duct, and these factors may have resulted in fewer AEs.

TRBO has been reported to be 240 to 385 days 10 16 17 for 10-mm FCSEMSs in previous randomized controlled trials. Although TRBO for 6-mm FCSEMSs has been reported in patients with preoperative pancreatic cancer, there is no previous report showing long-term results. In this study, considering the competing risks, cumulative incidence was calculated using the Gray’s test. The present study evaluated cumulative incidence of RBO in all cases and in unresectable cases, and no significant difference was found between the 10-mm and 6-mm groups in either type of case. Migration was a cause of RBO, which is a risk associated with FCSEMS use, but there was no significant difference between the groups ( P = 0.10). In terms of the causes of RBO, the 6-mm stent caused less debris and overgrowth than the 10-mm stent. We consider that the narrower 6-mm stent may have reduced the reflux of the duodenal fluid and thus prevented the formation of debris. In addition, the 6-mm FCSEMS allows for a longer stent with a lower shortening rate, which provides adequate tumor coverage and prevents overgrowth.

In this study of preoperative pancreatic cancer cases, the non-RBO rates in the time to surgery were 75.0 % and 80.8 % ( P = 0.66) in the 10-mm and 6-mm groups, respectively. Furthermore, the 6-mm group had significantly fewer total AEs than the 10-mm group. Thus, the 6-mm FCSEMS may be useful in preoperative biliary drainage. Kataoka et al 28 compared the outcomes of a 6-mm FCSEMS and 7F to 8.5F PS retrospectively in patients with preoperative pancreatic cancer; they found that TRBO was longer in the 6-mm FCSEMS group ( P = 0.02) than in the 7F to 8.5F PS group, and stent-related complications were not significantly different between the groups ( P = 0.47). In summary, a 6-mm FCSEMS could be a well-balanced stent that reduces the risk of stent-related AEs as much as a PS, while ensuring TRBO comparable to the standard 10-mm FCSEMS. Regarding the possibility of shortening TRBO, which is a concern with thin stents, this study examined palliative drainage of unresectable cases and found no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of RBO with the 10-mm and 6-mm FCSEMS. In addition, the 6-mm group had more resectable/borderline resectable cases, which were considered as a competing risk for RBO and were analyzed using Fine-Gray sub-distribution hazard regression compared to the 10-mm group. Resectable/borderline resectable cases were extracted as a risk-reducing factor for RBO due to the limited observation period, in the cases of 6-mm FCSEMS, but not as a risk factor for RBO (SHR,1.30; 95 % CI, 0.48–3.48; P = 0.61). In other words, a 6-mm FCSEMS may be the first choice for a large number of patients, including preoperative and unresectable cases.

This study has several limitations. This study was a single-center, retrospective study and had small sample size. It is possible that the 6-mm group had more cases of preoperative pancreatic cancer due to selection bias, which may have affected the outcome of the study. A randomized controlled trial is needed to confirm this study’s results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this is the first report to compare the outcomes of the thinner-diameter 6-mm FCSEMS with those of the standard 10-mm FCSEMS. In the 6-mm FCSEMS, a cumulative incidence of RBO was comparable to that of the 10-mm FCSEMS, and furthermore, the risk of pancreatitis and cholecystitis was reduced. A prospective study is planned to evaluate these findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the endoscopy team of the Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Oncology, National Cancer Center Hospital, for their support of this research. This study was funded by The National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (2022-A-16) and a grant from the Japanese Foundation for Research and Promotion of Endoscopy. The funding source had no role in the design, practice or analysis of this study.

Footnotes

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dumonceau J M, Tringali A, Papanikolaou I S et al. Endoscopic biliary stenting: indications, choice of stents, and results: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline - Updated October 2017. Endoscopy. 2018;50:910–930. doi: 10.1055/a-0659-9864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner T B, Spangler C C, Byanova K L et al. Cost-effectiveness and clinical efficacy of biliary stents in patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma in a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aadam A A, Evans D B, Khan A et al. Efficacy and safety of self-expandable metal stents for biliary decompression in patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song T J, Lee J H, Lee S S et al. Metal versus plastic stents for drainage of malignant biliary obstruction before primary surgical resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:814–821. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tol J A, van Hooft J E, Timmer R et al. Metal or plastic stents for preoperative biliary drainage in resectable pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2016;65:1981–1987. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crippa S, Cirocchi R, Partelli S et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of metal versus plastic stents for preoperative biliary drainage in resectable periampullary or pancreatic head tumors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:1278–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almadi M A, Barkun A, Martel M. Plastic vs. self-expandable metal stents for palliation in malignant biliary obstruction: a series of meta-analyses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:260–273. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Decker C, Christein J D, Phadnis M A et al. Biliary metal stents are superior to plastic stents for preoperative biliary decompression in pancreatic cancer. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2364–2367. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1552-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong W D, Chen X W, Wu W Z et al. Metal versus plastic stents for malignant biliary obstruction: an update meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kogure H, Ryozawa S, Maetani I et al. A prospective multicenter study of a fully covered metal stent in patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction: WATCH-2 study. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:2466–2473. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fumex F, Coumaros D, Napoleon B et al. Similar performance but higher cholecystitis rate with covered biliary stents: results from a prospective multicenter evaluation. Endoscopy. 2006;38:787–792. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitano M, Yamashita Y, Tanaka K et al. Covered self-expandable metal stents with an anti-migration system improve patency duration without increased complications compared with uncovered stents for distal biliary obstruction caused by pancreatic carcinoma: a randomized multicenter trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1713–1722. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moses P L, Alnaamani K M, Barkun A N et al. Randomized trial in malignant biliary obstruction: plastic vs partially covered metal stents. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8638–8646. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukai T, Yasuda I, Isayama H et al. Pilot study of a novel, large-bore, fully covered self-expandable metallic stent for unresectable distal biliary malignancies. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:671–679. doi: 10.1111/den.12643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loew B J, Howell D A, Sanders M K et al. Comparative performance of uncoated, self-expanding metal biliary stents of different designs in 2 diameters: final results of an international multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawashima H, Hashimoto S, Ohno E et al. Comparison of 8- and 10-mm diameter fully covered self-expandable metal stents: A multicenter prospective study in patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction. Dig Endosc. 2019;31:439–447. doi: 10.1111/den.13366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elshimi E, Morad W, Elshaarawy O et al. Optimization of biliary drainage in inoperable distal malignant strictures. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;12:285–296. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v12.i9.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isayama H, Komatsu Y, Tsujino T et al. A prospective randomised study of “covered” versus “uncovered” diamond stents for the management of distal malignant biliary obstruction. Gut. 2004;53:729–734. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.018945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kikuyama M, Shirane N, Kawaguchi S et al. New 14-mm diameter Niti-S biliary uncovered metal stent for unresectable distal biliary malignant obstruction. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;10:16–22. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v10.i1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isayama H, Hamada T, Yasuda I et al. Tokyo criteria 2014 for transpapillary biliary stenting. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:259–264. doi: 10.1111/den.12379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dumonceau J M, Andriulli A, Deviere J et al. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline: prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2010;42:503–515. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeda T, Sasaki T, Mie T et al. Novel risk factors for recurrent biliary obstruction and pancreatitis after metallic stent placement in pancreatic cancer. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8:E1603–E1610. doi: 10.1055/a-1244-1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maruyama H, Shiba M, Ishikawa-Kakiya Y et al. Positive correlation between pancreatic volume and post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:769–776. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Nakai Y et al. Risk factors for pancreatitis following transpapillary self-expandable metal stent placement. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:771–776. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1950-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Kawakubo K et al. Metallic stent with high axial force as a risk factor for cholecystitis in distal malignant biliary obstruction. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1557–1562. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao J, Peng C, Ding X et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP cholecystitis: a single-center retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:128. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0854-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakaoka K, Hashimoto S, Kawabe N et al. Evaluation of a 12-mm diameter covered self-expandable end bare metal stent for malignant biliary obstruction. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E1164–E1170. doi: 10.1055/a-0627-7078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kataoka F, Inoue D, Watanabe M et al. Efficacy of 6-mm diameter fully covered self‐expandable metallic stents in preoperative biliary drainage for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. DEN Open. 2022;2:e55. doi: 10.1002/deo2.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]