Key Points

Question

What are the associations between prenatal exposure to antiseizure medications and psychiatric disorders with onset in childhood and adolescence?

Findings

In this cohort study of 38 661 children of mothers with epilepsy, prenatal valproate exposure was associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders. Prenatal exposure to lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine was not associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders, whereas associations were found for prenatal exposure to topiramate and levetiracetam with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Meaning

This study strengthens the evidence for the warning against the use of valproate in pregnancy, supports concerns about the use of topiramate, and provides a preliminary indication for caution with the use of levetiracetam in pregnancy.

This cohort study of children of mothers with epilepsy examines whether prenatal exposure to common prenatal antiseizure medication is associated with a broad spectrum of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence.

Abstract

Importance

Prenatal antiseizure medication (ASM) exposure has been associated with adverse early neurodevelopment, but associations with a wider range of psychiatric end points have not been studied.

Objective

To examine the association between prenatal exposure to ASM with a spectrum of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence in children of mothers with epilepsy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective, population-based register study assessed 4 546 605 singleton children born alive in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden from January 1, 1996, to December 31, 2017. Of the 4 546 605 children, 54 953 with chromosomal disorders or uncertain birth characteristics were excluded, and 38 661 children of mothers with epilepsy were identified. Data analysis was performed from August 2021 to January 2023.

Exposures

Prenatal exposure to ASM was defined as maternal prescription fills from 30 days before the first day of the last menstrual period until birth.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome measure was diagnosis of psychiatric disorders (a combined end point and 13 individual disorders). Estimated adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) using Cox proportional hazards regression and cumulative incidences with 95% CIs are reported.

Results

Among the 38 661 children of mothers with epilepsy (16 458 [42.6%] exposed to ASM; 19 582 [51.3%] male; mean [SD] age at the end of study, 7.5 [4.6] years), prenatal valproate exposure was associated with an increased risk of the combined psychiatric end point (aHR, 1.80 [95% CI, 1.60-2.03]; cumulative risk at 18 years in ASM-exposed children, 42.1% [95% CI, 38.2%-45.8%]; cumulative risk at 18 years in unexposed children, 31.3% [95% CI, 28.9%-33.6%]), which was driven mainly by disorders within the neurodevelopmental spectrum. Prenatal exposure to lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine was not associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders, whereas associations were found for prenatal exposure to topiramate with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (aHR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.40-4.06) and exposure to levetiracetam with anxiety (aHR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.26-3.72) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (aHR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.03-3.07).

Conclusions and Relevance

Findings from this explorative study strengthen the evidence for the warning against the use of valproate in pregnancy and raise concern of risks of specific psychiatric disorders associated with topiramate and levetiracetam. This study provides reassuring evidence that lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine are not associated with long-term behavioral or developmental disorders but cannot rule out risks with higher doses.

Introduction

The use of antiseizure medication (ASM) among pregnant women has increased during recent decades, and today between 0.5% and 2% of all children are born to women using ASMs during pregnancy.1 In pregnancy, ASMs are used mainly for epilepsy but may be prescribed for other indications, such as mood disorders, migraine, and neuropathic pain.2,3

There are increasing concerns of adverse effects in offspring after prenatal ASM exposure. The evidence of harm is most definitive for valproate4 and shows increased risk of congenital anomalies5 and adverse neurodevelopment, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD),6,7,8,9,10 attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),7,11,12 and impaired cognitive function.9,10,13,14,15,16,17,18 Other ASMs influence fetal growth and development,19 yet our understanding of the potential link with psychiatric disorders in childhood is limited. Even in studies6,11,17,18 based on nationwide cohorts, data are insufficient to examine associations with less frequently used ASMs, warranting studies combining data from multiple countries. Current evidence is further limited to some neurodevelopmental outcomes, such as ASD and intellectual disability, but it is unclear whether the potential adverse behavioral effects of prenatal ASM exposure is limited to these end points. To inform clinicians and patients about the potential risks, there is a need to systematically compare different ASMs with respect to a broader spectrum of psychiatric disorders. In this Nordic cohort study of more than 38 000 children of mothers with epilepsy, we examined the association between prenatal exposure to common ASMs with a broad spectrum of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Population

We performed a prospective, population-based register study within the SCAN-AED project, which is a study of ASM teratogenicity based on children born in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. The SCAN-AED cohort was established by pooling and harmonizing individual-level data from the nationwide health and social registers from each of the 5 countries. This process was possible because of the similarity of the structure and contents of the registers and included data on all births (medical birth registers), maternal and child diagnoses (patient and hospital registers), dispensed prescription medications (prescription registers), vital status and place of residence (population registers), and socioeconomic measures (eg, education registers). Accurate linkage between the registers was ensured using a unique personal identification number. The relevant ethical and/or data protection authorities in all countries approved the project and granted a waiver of informed consent because no informed consent is required for a register-based study using anonymized data according to legislation in the Nordic countries. None of the participants received a stipend. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

This study was based on live-born singleton children of mothers with epilepsy in Denmark (1997-2017), Finland (1996-2016), Iceland (2004-2017), Norway (2005-2017), and Sweden (2006-2017) for the years with full coverage of all relevant registers (eFigure in Supplement 1). Maternal epilepsy was defined by a hospital contact with epilepsy before birth (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] codes G40-G41, all countries), use of ASM with epilepsy as an indication or reason for reimbursement before birth (Denmark since 2004, Norway, and Finland), or any registered diagnosis of epilepsy in the Medical Birth Register (all countries except Denmark) (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

Maternal Use of ASM in Pregnancy

Information on use of ASM was based on the national prescription registers, which contain information on all reimbursed prescription medications dispensed at pharmacies in each country, including date of dispensing and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification code. Children were considered prenatally exposed to ASM if the mother had redeemed 1 or more prescriptions for medications with ATC codes N03A (ASM), N05BA09 (clobazam), or S01EC01 (acetazolamide, data not available from Finland) during the exposure window, which was defined as 30 days before the first day of the last menstrual period (estimated using gestational age in days at birth) until the date of birth. We defined monotherapy with valproate, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, topiramate, clonazepam, pregabalin, and gabapentin as having redeemed 1 or more prescriptions for that specific ASM and no other prescriptions for ASMs in the exposure window. We defined polytherapy as having redeemed 1 or more prescriptions for 2 or more different ASMs during the exposure window and divided polytherapy into combinations with and without valproate. This definition did not distinguish between true polytherapy and those switching from one ASM to another, but even among switchers, transitional polytherapy is often necessary in the up-titration and tapering phase.

Child Psychiatric Disorders

Information on psychiatric disorders was retrieved from the patient registers, which contain diagnostic information from inpatient admissions and outpatient visits in specialist care. We considered the children to have a psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorder if they were registered with any main or secondary diagnosis from the ICD-10 F-chapter (excluding F00-09) and classified disorders further into 13 groups20 (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). For the combined psychiatric end point and for each subgroup, we defined the date of onset as the first day of the first inpatient or outpatient contact with that disorder.

Statistical Analysis

The children were followed up from birth until onset of the psychiatric disorder of interest, death, emigration, or the end of follow-up, whichever came first. We estimated 3 main measures of the risk of psychiatric disorders associated with prenatal ASM exposure: (1) incidence rates expressed as the number of affected children per 10 000 person-years, (2) hazard ratios (HRs) as relative risk measures of the association between prenatal ASM exposure and psychiatric disorders, and (3) cumulative incidences of psychiatric disorders across age, as an absolute measure of risk. Because this study was considered explorative, we did not adjust for multiple testing, but all main analyses were prespecified. Data analysis was performed from August 2021 to January 2023.

The HRs and corresponding 95% CIs were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression models. Age of the child was used as the underlying time scale, and we allowed for separate baseline diagnostic rates of psychiatric disorders (stratum) for each country and year of birth to account for country-wise differences in diagnostic practices and calendar period effects. The reference group was children of mothers with epilepsy unexposed to any ASM during the exposure window. We adjusted the HRs for sex of the child, smoking in pregnancy, use of antidepressants (ATC code N06A) in pregnancy, and maternal characteristics assessed at the time of birth (age, parity, highest level of completed education, and psychiatric comorbidity). Missing information on covariates was generally limited (range, 0%-3%), except for maternal smoking status (range, 6%-8%). For maternal smoking, we therefore included a separate missing category and otherwise performed complete case analyses. Proportionality of hazards was assessed visually using log minus log plots.

The cumulative incidence of psychiatric disorders was estimated using a nonparametric approach based on the subdistribution hazards, with death and emigration as competing events.21 The cumulative incidence can be interpreted as the risk of being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder within a given period.

To identify potential heterogeneity across countries, we performed country-wise analyses of any ASM exposure with each of the psychiatric outcomes. Because of the low number of children in many exposure-outcome combinations, the country-specific analyses were not restricted to children of mothers with epilepsy.

Several sensitivity analyses were performed. First, we restricted the population to children of mothers with active epilepsy, defined as a hospital contact with epilepsy or a prescription for antiseizure medication for epilepsy within 1 year before pregnancy and until birth. Second, children of mothers who redeemed only 1 prescription for ASMs during the exposure window were reclassified as unexposed. Third, we applied a minimum age criterion for each psychiatric end point.22

Results

We identified 38 661 children of mothers with epilepsy (19 852 [51.3%] male and 18 809 [48.7%] female), who were followed up to 22 years of age (mean [SD] age, 7.5 [4.6] years; see eTable 3 in Supplement 1 for length of follow-up by ASM exposure). In total, 16 458 children (42.6%) were prenatally exposed to ASM, and the maternal and pregnancy characteristics of the children are given in Table 1. Prenatal ASM exposure was associated with higher maternal educational attainment and lower levels of maternal smoking and diagnosed psychiatric comorbidity (but slightly higher levels of antidepressant use).

Table 1. Characteristics of Children With and Without Prenatal Exposure to Antiseizure Medication (ASM), Based on 38 661 Children of Mothers With Epilepsy in 5 Nordic Countries (1996-2017).

| Characteristic | Children of mothers with epilepsy | Proportion difference (95% CI) (any ASM minus no ASM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No ASM (n = 22 203) | Any ASM (n = 16 458) | ||

| Country of birth | |||

| Denmark | 9383 (42.3) | 4746 (28.8) | −13.4 (−14.4 to −12.5) |

| Finland | 1225 (5.5) | 4656 (28.3) | 22.8 (22.0 to 23.5) |

| Iceland | 91 (0.4) | 178 (1.1) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) |

| Norway | 6097 (27.5) | 2950 (17.5) | −9.5 (−10.4 to −8.7) |

| Sweden | 5407 (24.4) | 3928 (23.9) | −0.5 (−1.3 to 0.4) |

| Year of birth | |||

| 1996-1999 | 400 (1.8) | 1049 (6.4) | 4.6 (4.2 to 5.0) |

| 2000-2004 | 1457 (6.6) | 2071 (12.6) | 6.0 (5.4 to 6.6) |

| 2005-2009 | 6481 (29.2) | 4788 (29.1) | −0.1 (−1.0 to 0.8) |

| 2010-2014 | 8550 (38.5) | 5519 (33.5) | −5.0 (−5.9 to −4.0) |

| 2015-2017 | 5315 (23.9) | 3031 (18.4) | −5.5 (−6.3 to −4.7) |

| Sex of child | |||

| Male | 11 382 (51.3) | 8470 (51.5) | 0.2 (−0.8 to 1.2) |

| Female | 10 821 (48.7) | 7988 (48.5) | −0.2 (−1.2 to 0.8) |

| Maternal age, y | |||

| <20 | 498 (2.2) | 325 (2.0) | −0.3 (−0.6 to 0.0) |

| 20-24 | 3605 (16.2) | 2247 (13.7) | −2.6 (−3.3 to −1.9) |

| 25-29 | 6945 (31.3) | 5114 (31.1) | −0.2 (−1.1 to 0.7) |

| 30-34 | 6960 (31.3) | 5468 (33.2) | 1.9 (0.9 to 2.8) |

| 35-39 | 3482 (15.7) | 2739 (16.6) | 1.0 (0.2 to 1.7) |

| 40-44 | 677 (3.0) | 545 (3.3) | 0.3 (−0.1 to 0.6) |

| ≥45 | 36 (0.2) | 20 (0.1) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.0) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Maternal parity | |||

| 0 | 9832 (44.3) | 7658 (46.5) | 2.2 (1.2 to 3.3) |

| 1 | 7713 (34.7) | 5567 (33.8) | −0.9 (−1.9 to 0.0) |

| ≥2 | 4605 (20.7) | 3138 (19.1) | −1.7 (−2.5 to −0.9) |

| Missing | 53 (0.2) | 95 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.5) |

| Maternal educational level | |||

| Compulsory | 5827 (26.2) | 3402 (20.7) | −5.6 (−6.4 to −4.7) |

| Secondary or preuniversity | 9509 (42.8) | 7908 (48.0) | 5.2 (4.2 to 6.2) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 4231 (19.1) | 3205 (19.5) | 0.4 (−0.4 to 1.2) |

| Master’s degree or PhD | 2057 (9.3) | 1403 (8.5) | −0.7 (−1.3 to −0.2) |

| Missing | 579 (2.6) | 540 (3.3) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.0) |

| Smoking in pregnancy | |||

| No | 16 823 (75.8) | 12 630 (76.7) | 1.0 (0.1 to 1.9) |

| Yes | 3931 (17.7) | 2590 (15.7) | −2.0 (−2.7 to −1.2) |

| Missing | 1449 (6.5) | 1238 (7.5) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.5) |

| Use of antidepressants in pregnancy | 1631 (7.3) | 1376 (8.4) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.6) |

Prenatal exposure to valproate monotherapy was associated with a 1.80-fold (95% CI, 1.60-2.03) increased risk of the combined psychiatric end point compared with no prenatal ASM exposure (Table 2). None of the other monotherapies was associated with a significantly increased risk of the combined psychiatric end point, but associations were found for polytherapy with valproate (aHR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.56-2.18) and polytherapy without valproate (aHR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.15-1.51) (Table 2).

Table 2. Incidence Rates, Hazard Ratios, and Cumulative Incidence at 10 and 18 Years of Age of the Combined Psychiatric End Point in Children Exposed and Unexposed to ASM During Pregnancy, Based on 38 661 Children of Mothers With Epilepsy in 5 Nordic Countries (1996-2017).

| Exposure | No. of children | No. of children with psychiatric disorder | Incidence rate per 10 000 person-years (95% CI) | aHR (95% CI) | Cumulative incidence, % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basica | Fullb | Age 10 y | Age 18 y | ||||

| No ASM | 22 203 | 1892 | 132.9 (127.1-139.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 13.9 (13.2-14.6) | 31.3 (28.9-33.6) |

| Any ASMc | 16 458 | 2201 | 178.9 (171.6-186.5) | 1.12 (1.05-1.20) | 1.17 (1.09-1.25) | 17.4 (16.6-18.2) | 30.8 (29.2-32.3) |

| Monotherapies | |||||||

| Valproate | 1952 | 515 | 304.6 (279.4-332.1) | 1.71 (1.52-1.92) | 1.80 (1.60-2.03) | 27.2 (24.9-29.4) | 42.1 (38.2-45.8) |

| Lamotrigine | 5288 | 389 | 117.0 (105.9-129.2) | 0.87 (0.78-0.97) | 0.91 (0.82-1.02) | 12.4 (11.1-13.8) | 24.1 (19.7-28.7) |

| Levetiracetam | 1061 | 59 | 130.7 (101.3-168.7) | 1.14 (0.87-1.48) | 1.30 (0.99-1.71) | 17.6 (12.2-23.8) | NA |

| Carbamazepine | 2665 | 391 | 156.4 (141.7-172.7) | 0.94 (0.83-1.07) | 1.06 (0.93-1.22) | 15.0 (13.4-16.7) | 27.3 (24.5-30.1) |

| Oxcarbazepine | 1460 | 197 | 144.2 (125.4-165.9) | 0.78 (0.65-0.92) | 0.85 (0.71-1.02) | 12.3 (10.4-14.4) | 27.1 (23.1-31.2) |

| Topiramate | 290 | 34 | 182.0 (130.1-254.8) | 1.31 (0.92-1.85) | 1.34 (0.94-1.90) | 20.4 (14.0-27.7) | NA |

| Clonazepam | 339 | 64 | 189.0 (147.9-241.4) | 1.26 (0.97-1.64) | 1.08 (0.83-1.42) | 15.8 (11.7-20.5) | 35.1 (26.2-44.1) |

| Pregabalin | 120 | 8 | 164.1 (82.1-328.1) | 1.61 (0.80-3.26) | 1.06 (0.52-2.16) | NA | NA |

| Gabapentin | 138 | 16 | 190.6 (116.8-311.1) | 1.48 (0.90-2.42) | 1.30 (0.78-2.18) | NA | NA |

| Polytherapies | |||||||

| Without valproate | 2092 | 295 | 205.1 (183.0-229.9) | 1.33 (1.17-1.51) | 1.32d (1.15-1.51) | 21.0 (18.6-23.5) | 31.7 (27.5-36.0) |

| With valproate | 822 | 202 | 311.9 (271.7-358.0) | 1.86 (1.58-2.19) | 1.85 (1.56-2.18)d | 28.7 (25.0-32.5) | NAe |

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; ASM, antiseizure medication; NA, not analyzed because of low numbers or insufficient follow-up time.

Adjusted for year of birth, sex of the child, and country of birth.

Additionally adjusted for maternal age, parity, educational level, smoking in pregnancy, use of antidepressants in pregnancy, and maternal psychiatric comorbidity.

Numbers in monotherapy and polytherapy do not add up to any ASM exposure because the following monotherapies are not included because of low numbers: eslicarbazepine, lacosamide, acetazolamide, phenobarbital, and phenytoin.

The aHR for the risk of the combined psychiatric end point for polytherapy with valproate vs polytherapy without valproate was 1.39 (95% CI, 1.15-1.69).

Estimated based on available data up to 17 years of age (40.4%; 95% CI, 35.3%-45.5%).

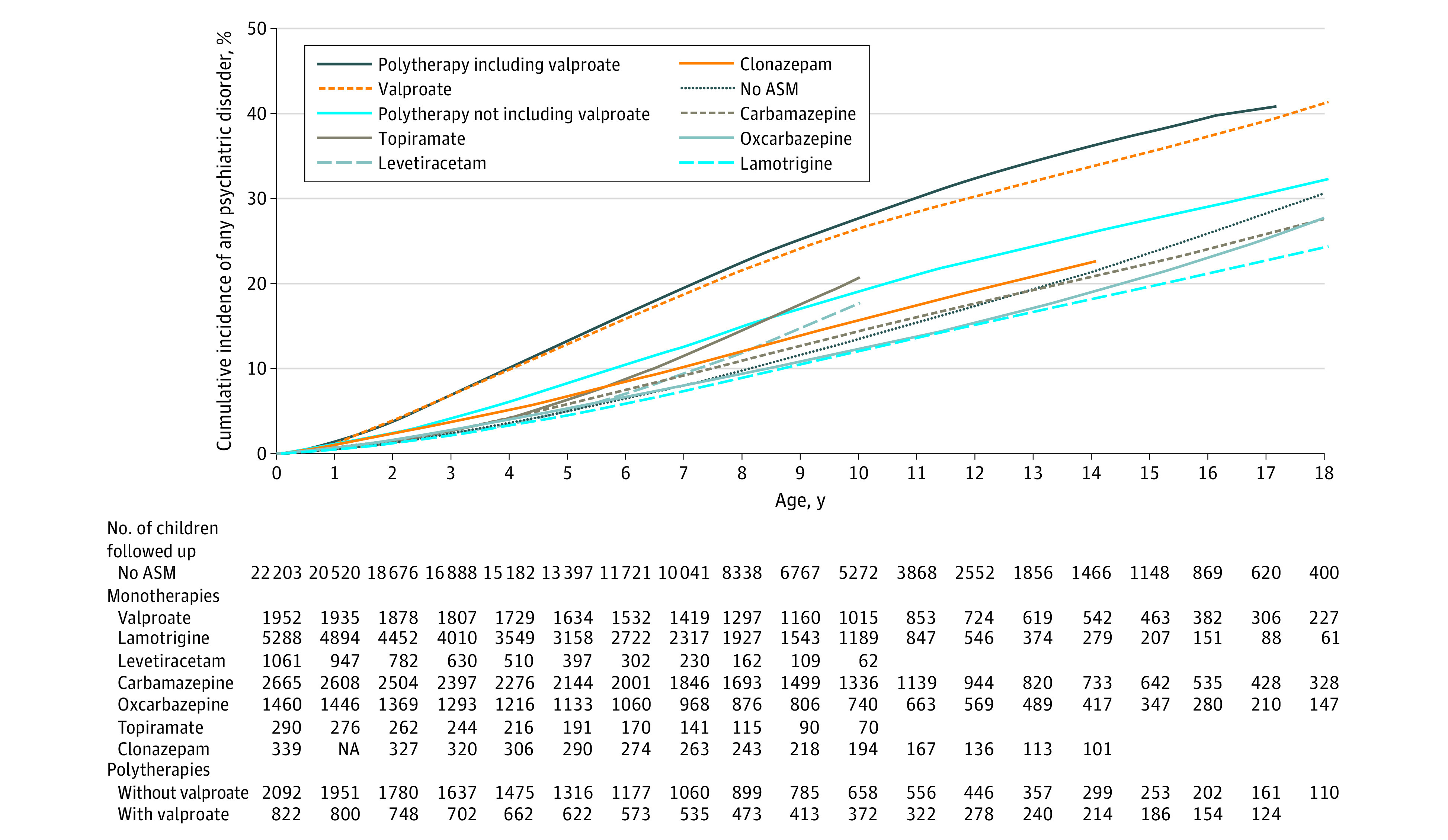

Figure 1 shows the cumulative risk of psychiatric disorders across childhood and adolescence (see point estimates with 95% CIs for ages 10 and 18 years in Table 2). Children of mothers with epilepsy unexposed to ASM had a 31.3% (95% CI, 28.9%-33.6%) risk of being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder by 18 years of age, whereas the corresponding risk was 42.1% (95% CI, 38.2%-45.8%) for valproate monotherapy exposure and 40.4% (95% CI, 35.3%-45.5%) for valproate polytherapy exposure (could only be estimated up to 17 years).

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of the Combined Psychiatric End Point According to Prenatal Antiseizure Medication (ASM) Exposure.

The cumulative incidence curves are unadjusted. Different lengths of the curves reflect differences in available follow-up data for the ASMs. NA indicates not applicable.

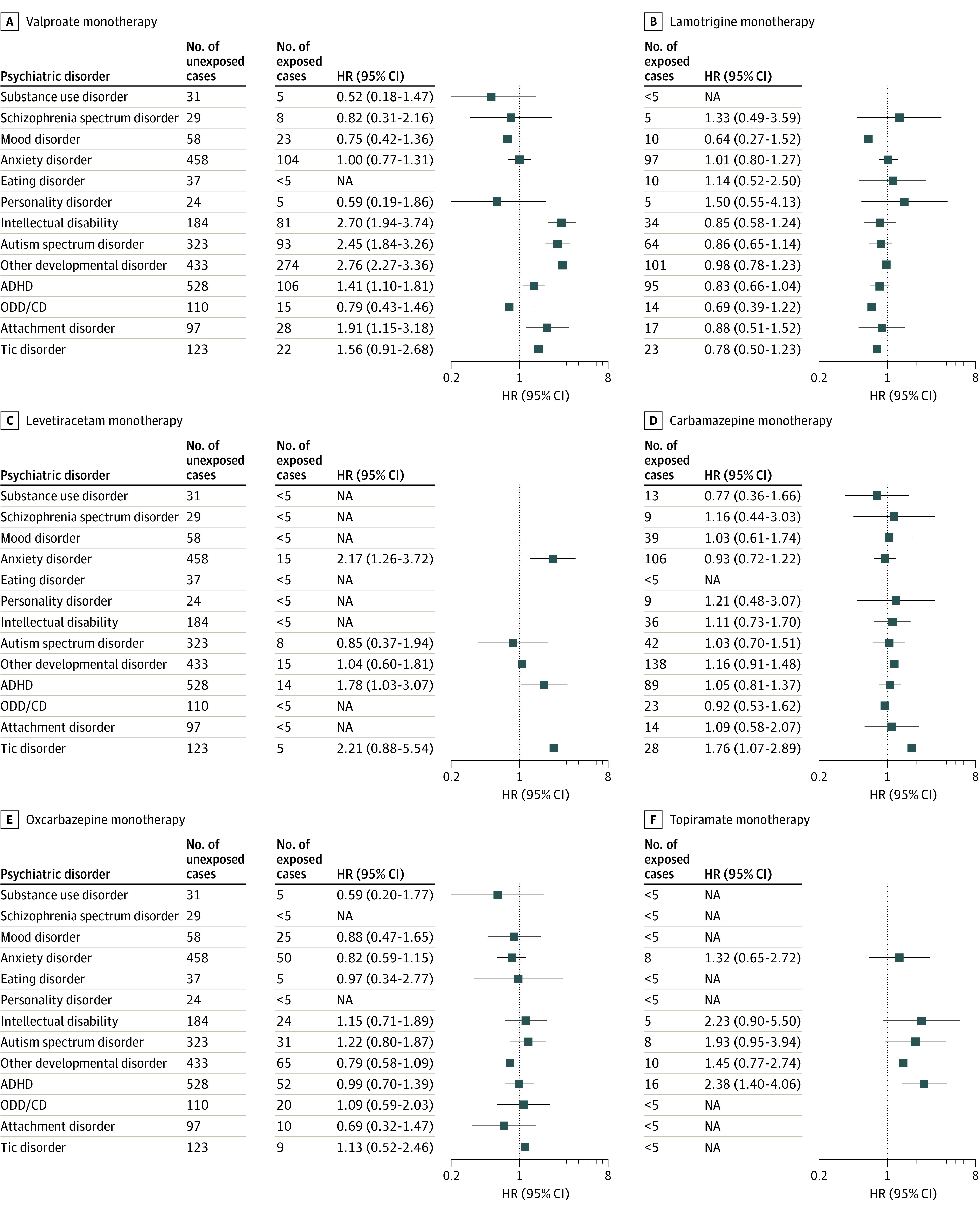

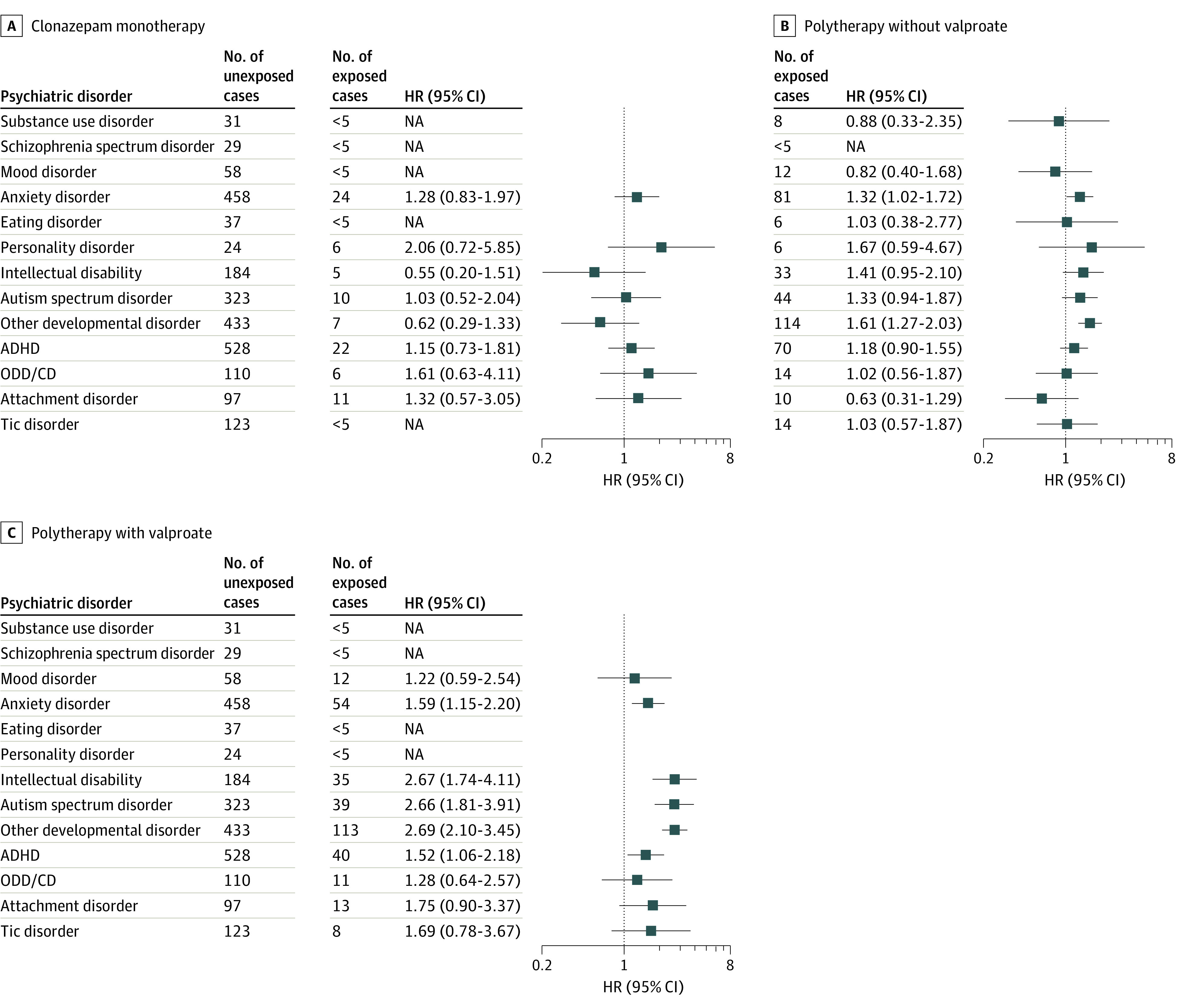

Children with prenatal valproate exposure had an increased risk of a range of early-onset disorders (Figure 2 and Figure 3), including intellectual disability (aHR, 2.70; 95% CI, 1.94-3.74), ASD (aHR, 2.45; 95% CI, 1.84-3.26), other developmental disorders (aHR, 2.76; 95% CI, 2.27-3.36), ADHD (aHR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.10-1.81), and attachment disorder (aHR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.15-3.18). In contrast, prenatal valproate exposure was not associated with increased risk of later-onset psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety, mood, substance use, or schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Analyses of lamotrigine and oxcarbazepine consistently identified no increased risk across the entire spectrum of psychiatric disorders studied, as did analyses of carbamazepine, with the exception of the risk of tic disorder (aHR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.07-2.89). Analyses of levetiracetam were hampered by limited follow-up (mean [SD], 4.4 [3.1] years), but prenatal levetiracetam exposure was associated with higher rates of anxiety (aHR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.26-3.72) and ADHD (aHR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.03-3.07). The number of children with prenatal exposure to topiramate was relatively low (n = 290; mean [SD] follow-up, 7.0 [3.7] years), but they had an increased risk of ADHD (aHR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.40-4.06) and potentially of intellectual disability (aHR, 2.23; 95% CI, 0.90-5.50) and ASD (aHR, 1.93; 95% CI, 0.95-3.94).

Figure 2. Hazard Ratios (HRs) of Psychiatric Disorders According to Maternal Antiseizure Medication (ASM) Use in Pregnancy for Valproate, Lamotrigine, Levetiracetam, and Carbamazepine Monotherapies.

The HRs are adjusted for sex of the child, maternal age, parity, educational level, smoking in pregnancy, use of antidepressants in pregnancy, and maternal psychiatric comorbidity, with separate baseline hazards for country and year of birth. ADHD indicates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; NA, not applicable; ODD/CD, oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder.

Figure 3. Hazard Ratios (HRs) of Psychiatric Disorders According to Maternal Antiseizure Medication (ASM) Use in Pregnancy for Clonazepam Monotherapy, Polytherapy Without Valproate, and Polytherapy With Valproate.

Associations are not shown for pregabalin and gabapentin because of insufficient numbers. The HRs are adjusted for sex of the child, maternal age, parity, educational level, smoking in pregnancy, use of antidepressants in pregnancy, and maternal psychiatric comorbidity, with separate baseline hazards for country and year of birth. ADHD indicates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; NA, not applicable; ODD/CD, oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder.

The cumulative incidence of specific psychiatric disorders at 15 years of age by ASM exposure is shown in Table 3 (corresponding estimates at ages 10 and 18 years are provided in eTables 4 and 5 in Supplement 1). The most common disorders in children of mothers with epilepsy prenatally exposed to valproate monotherapy was other developmental disorders (including developmental disorders of speech, scholastic skills, and motor function). The cumulative incidence at 15 years was 18.2% (95% CI, 16.1%-20.3%), which was substantially higher than in children of mothers with epilepsy unexposed to ASM (4.7%; 95% CI, 4.1%-5.4%). Other disorders with elevated absolute risks in children with prenatal valproate monotherapy exposure included ADHD (9.6%; 95% CI, 7.8%-11.7%), ASD (6.8%; 95% CI, 5.4%-8.5%), and intellectual disability (5.2%; 95% CI, 4.1%-6.5%). Country-specific analyses of associations between prenatal ASM exposure and each psychiatric end point are provided in eTable 6 in Supplement 1. These analyses showed that absolute rates of psychiatric disorders varied among the 5 countries, but there was little variation in the relative risk measures (ie, the HRs ranged from 1.7 to 2.3 for the combined psychiatric end point in children with vs without prenatal ASM exposure).

Table 3. Cumulative Incidence of Psychiatric Disorders at Age 15 Years in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on 38 661 Children of Mothers With Epilepsy in 5 Nordic Countries (1996-2017)a.

| Psychiatric disorder | ASM | Monotherapies | Polytherapies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 22 203) | Any (n = 16 458) | Valproate (n = 1952) | Lamotrigine (n = 5288) | Carbamazepine (n = 2665) | Oxcarbazepine (n = 1460) | Clonazepam (n = 339) | Without valproate (n = 2092) | With valproate (n = 822) | |

| Substance use | 0.0 (0.0-0.1) | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Schizophrenia spectrum | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | 0.5 (0.3-0.8) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mood | 1.5 (1.0-2.2) | 2.4 (1.9-3.1) | 1.7 (0.9-2.9) | NA | 3.0 (2.0-4.4) | 3.5 (2.1-5.6) | NA | NA | NA |

| Anxiety | 8.6 (7.6-9.8) | 8.4 (7.6-9.3) | 8.3 (6.5-10.4) | 8.9 (6.5-11.6) | 7.5 (6.0-9.3) | 6.1 (4.2-8.4) | 8.1 (4.5-13.1) | 9.2 (6.9-11.9) | 13.8 (10.2-17.9) |

| Eating | 0.5 (0.3-0.8) | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Personality | 0.3 (0.1-0.7) | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Intellectual disability | 2.3 (1.9-2.8) | 3.1 (2.7-3.5) | 5.2 (4.1-6.5) | 2.1 (1.2-3.4) | NA | 2.5 (1.5-3.8) | NA | 3.8 (2.4-5.5) | 6.4 (4.4-9.0) |

| ASD | 4.0 (3.4-4.7) | 4.2 (3.7-4.8) | 6.8 (5.4-8.5) | 4.2 (2.8-6.1) | 2.4 (1.7-3.2) | 2.9 (1.9-4.2) | NA | 4.3 (3.0-5.9) | 7.7 (5.4-10.6) |

| Other developmental disorder | 4.7 (4.1-5.4) | 8.6 (8.0-9.3) | 18.2 (16.1-20.3) | NA | 7.2 (6.0-8.5) | 5.8 (4.5-7.4) | NA | 10.2 (8.3-12.4) | 19.9 (16.3-23.7) |

| ADHD | 7.9 (7.1-8.8) | 7.5 (6.8-8.2) | 9.6 (7.8-11.7) | 5.9 (4.5-7.6) | 5.7 (4.5-7.1) | 6.4 (4.8-8.3) | 9.7 (5.8-14.7) | 8.3 (6.3-10.6) | 8.2 (5.8-11.1) |

| ODD/CD | 1.9 (1.5-2.4) | 1.6 (1.3-2.0) | NA | NA | NA | 2.4 (1.4-3.7) | NA | ||

| Attachment disorder | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | 1.9 (1.2-2.9) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tic disorder | 1.7 (1.3-2.1) | 1.6 (1.3-1.9) | 1.6 (1.0-2.5) | NA | 1.8 (1.2-2.6) | NA | NA | ||

| Any psychiatric disorder | 22.8 (21.5-24.2) | 25.0 (23.9-26.1) | 34.8 (31.9-37.6) | 19.7 (17.0-22.6) | 22.3 (20.1-24.6) | 20.2 (17.3-23.3) | 22.5 (17.1-28.5) | 27.8 (24.4-31.3) | 38.5 (33.7-43.3) |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CD, conduct disorder; NA, not analyzed and estimated for combinations with fewer than 20 exposed cases or with insufficient follow-up (children with prenatal exposure to levetiracetam, topiramate, gabapentin, and pregabalin are consequently not included); ODD, oppositional defiant disorder.

The age of 15 years was chosen for balance, on one hand providing estimates for adolescent-onset disorders and on the other hand ensuring sufficient follow-up data for as many ASMs as possible. Estimates at ages 10 and 18 years are provided in eTables 3 and 4 in Supplement 1.

Restricting the population to 25 139 children of mothers with active epilepsy, of whom 15 378 (61.2%) were prenatally exposed to ASM, did not substantially change associations with the combined psychiatric end point, with the exception of the association with topiramate, which was stronger (aHR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.11-2.29), and the association with levetiracetam (aHR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.03-1.84), which reached statistical significance (eTable 7 in Supplement 1). Requiring at least 2 redeemed prescriptions did not meaningfully change the associations with each of the 9 ASM monotherapies (eTable 8 in Supplement 1), but the association with levetiracetam reached statistical significance (aHR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.02-1.79). Finally, only negligible changes in associations were observed when a lower age limit was applied for each of the 13 psychiatric disorders (eTable 9 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort with up to 22 years of follow-up, we estimated the absolute and relative risk of a broad spectrum of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence associated with prenatal ASM exposure among children of mothers with epilepsy. Our findings strengthen the evidence for the warning against the use of valproate in pregnancy, support concerns about the use of topiramate, and raise some concern about levetiracetam. For pregnant women with epilepsy, the results reassuringly indicate that prenatal exposure to lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine are associated with little or no long-term behavioral or developmental problems in their children.

Children with prenatal valproate exposure faced an absolute risk of being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder that exceeded 40% by the age of 18 years, mainly driven by a marked excess of neurodevelopmental disorders. These findings strengthen previous evidence of the association between prenatal valproate exposure and risk of ASD,6,7,8,9,10,23 ADHD,7,11,12 cognitive impairment,9,10,13,14,15,16,17,18 and developmental delay.18,24,25 Our study is the first, to our knowledge, to report associations between prenatal valproate exposure with other psychiatric and behavioral disorders. We observed no increased risk of psychiatric disorders occurring mainly later in life (eg, schizophrenia or mood disorders). However, we found an increased risk of attachment disorder in children with prenatal valproate exposure, which has not been reported before. The potential mechanism is unclear, but insecure attachment has been reported to be more prevalent in children with neurodevelopmental disorders,26 which could explain the finding. It is also possible that women using valproate in pregnancy have more severe epilepsy and psychiatric comorbidity, which may in turn affect mother-child attachment during the child’s upbringing.

Previous studies27,28 suggest that topiramate has a teratogenic potential; however, evidence regarding the risk of adverse behavioral outcomes is limited. Interestingly, we observed an increased risk of ADHD with prenatal topiramate exposure, which extends the potential behavioral risks identified in a recent SCAN-AED study10 based on the same cohort of children. In that study,10 the associations of prenatal topiramate exposure with ASD and intellectual disability were slightly stronger than in the current study (and reached statistical significance), which is explained by the former study applying a narrower exposure window (ie, not including the 30 days before the last menstrual period), which will tend to increase HRs due to higher specificity of exposure classification (but lower sensitivity).6,29 Findings from the 2 SCAN-AED studies contrast a few prior studies reporting no reductions in child cognitive abilities30 and no increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders associated with prenatal topiramate exposure9 but align with a few others.31,32,33 More evidence is therefore needed, but our findings strengthen the increasing concerns about the use of topiramate in pregnancy.

For lamotrigine, carbamazepine (with 1 exception), oxcarbazepine, clonazepam, pregabalin, and gabapentin, we found no association between prenatal exposure and psychiatric disorders. Evidence of cognitive and behavioral outcomes following prenatal exposure to these ASMs is most comprehensive for lamotrigine and carbamazepine,34 and findings from cohorts of children born to mothers with epilepsy largely, but not entirely,23,24,35 align with our findings. Important prospective clinical investigations from the UK and US (the Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs13,14 study and its extension Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs15) and data from European16 and US-based25 registries of pregnant women taking ASM have provided robust evidence regarding the comparative safety of lamotrigine and carbamazepine compared with valproate in terms of their neurodevelopmental effects. For oxcarbazepine, our findings are consistent with the existing, yet limited, evidence.34

Limitations

This study has several potential limitations. First, we present a vast number of analyses and did not adjust for multiple comparisons, which increases the risk of type 1 errors. Results should therefore be considered explorative. Second, given the large number of specific exposure-outcome combinations, it was not feasible to undertake in-depth analyses of, for example, exposure timing or dose. However, our results may serve to generate specific hypotheses for future research. Third, important country-wise differences existed in terms of data availability. For instance, the length of look-back in the registers to identify maternal epilepsy varied, with only 1 year before pregnancy in Iceland and Finland compared to up to 20 years in Denmark. Hence, the proportion of mothers with active epilepsy and in need of ASM treatment in pregnancy differed among countries, but sensitivity analyses in children of mothers with active epilepsy reassuringly aligned with the overall conclusions. Diagnostic rates of psychiatric disorders also varied among countries, possibly indicating differences in diagnostic practice or registration. However, we accounted for this in our statistical models, and country-specific analyses indicated that the relative risk measures varied less than absolute measures, suggesting that diagnostic differences were nondifferential in relation to prenatal ASM exposure. Fourth, residual confounding by maternal lifestyle (eg, body mass index and alcohol consumption) and psychiatric disease is possible. Lifestyle information is generally not well captured in the registers, but through the adjustment for correlated characteristics, such as maternal educational attainment and smoking, we have likely somewhat accounted for this. Information on maternal psychiatric disorders was only available from specialized health care, but we adjusted for antidepressant use in pregnancy, thereby capturing women pharmacologically treated in primary care or by private specialists only. Fifth, pregnant women who redeemed prescriptions for ASM were assumed to ingest the medication, and although high levels of adherence have been reported,36 some misclassification is possible. However, analyses restricting the exposure definition to at least 2 prescriptions (where such misclassification was reduced) were in line with the main findings. Furthermore, the quality of the data in the national prescription registers is considered to be high because of the reimbursement structure in the health care systems,37 which provides a strong economic incentive for recording all dispensed drugs and ensures high sensitivity in capturing drug exposures. Sixth, despite the sizeable population and lengthy follow-up, our data were insufficient to evaluate several less frequently used ASMs, including zonisamide, lacosamide, phenobarbital, and phenytoin, and we could not fully evaluate therapies such as levetiracetam and topiramate. Seventh, generalizability may depend on contextual factors, such as access to psychiatric care, diagnostic threshold norms, and differences in clinical practice (eg, in terms of types and dosing of ASM).

Conclusions

Findings from this large multinational cohort study strengthen the evidence for the warning against the use of valproate in pregnancy, support concerns about the use of topiramate, raise preliminary indication for caution with use of levetiracetam, and provide reassuring evidence that lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine are not associated with long-term behavioral or developmental disorders. Long-term follow-up data are still needed for less frequently used ASMs to fully evaluate potential behavioral risks associated with prenatal exposure.

eTable 1. Information Available in SCAN-AED From Each Country to Determine Maternal Epilepsy Status

eTable 2. List of ICD-10 codes and Corresponding Disorders Included in the 13 Subgroups of Psychiatric Disorders

eTable 3. Average Length of Follow-up by ASM Exposure Groups

eTable 4. Cumulative Incidence of Psychiatric Disorders at Age 10 Years in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on 38 661 Children of Mothers With Epilepsy in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017)

eTable 5. Cumulative Incidence of Psychiatric Disorders at Age 18 Years in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on 38 661 Children of Mothers With Epilepsy in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017)

eTable 6. Country-Specific Incidence Rates, Hazard Ratios, and Cumulative Incidence of Specific Psychiatric Disorders in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on Children Born in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017)

eTable 7. Incidence Rates, Hazard Ratios (HR) and Cumulative Incidence at Age 10 and 18 Year of the Combined Psychiatric Endpoint in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on 25 139 Children of Mothers With Active Epilepsy in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017)

eTable 8. Incidence Rates, Hazard Ratios (HR) and Cumulative Incidence at Age 10 and 18 Year of the Combined Psychiatric Endpoint in Children Exposed (at Least Two Prescriptions) and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on 38 661 Children of Mothers With Epilepsy in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017)

eTable 9. Age-Restricted Analysis of Specific Psychiatric Disorders in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on Children Born in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017

eFigure. Flowchart of the study population

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Cohen JM, Cesta CE, Furu K, et al. Prevalence trends and individual patterns of antiepileptic drug use in pregnancy 2006-2016: a study in the five Nordic countries, United States, and Australia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020;29(8):913-922. doi: 10.1002/pds.5035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pennell PB. Use of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy: evolving concepts. Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13(4):811-820. doi: 10.1007/s13311-016-0464-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurko T, Saastamoinen LK, Tuulio-Henriksson A, et al. Trends in the long-term use of benzodiazepine anxiolytics and hypnotics: a national register study for 2006 to 2014. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(6):674-682. doi: 10.1002/pds.4551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Antiepileptic Drugs: Review of Safety of Use During Pregnancy. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency; 2021. Accessed March 4, 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/public-assesment-report-of-antiepileptic-drugs-review-of-safety-of-use-during-pregnancy/antiepileptic-drugs-review-of-safety-of-use-during-pregnancy

- 5.Jentink J, Loane MA, Dolk H, et al. ; EUROCAT Antiepileptic Study Working Group . Valproic acid monotherapy in pregnancy and major congenital malformations. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(23):2185-2193. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen J, Grønborg TK, Sørensen MJ, et al. Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and childhood autism. JAMA. 2013;309(16):1696-1703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiggs KK, Rickert ME, Sujan AC, et al. Antiseizure medication use during pregnancy and risk of ASD and ADHD in children. Neurology. 2020;95(24):e3232-e3240. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bromley RL, Mawer G, Clayton-Smith J, Baker GA; Liverpool and Manchester Neurodevelopment Group . Autism spectrum disorders following in utero exposure to antiepileptic drugs. Neurology. 2008;71(23):1923-1924. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339399.64213.1a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coste J, Blotiere PO, Miranda S, et al. Risk of early neurodevelopmental disorders associated with in utero exposure to valproate and other antiepileptic drugs: a nationwide cohort study in France. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):17362. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74409-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjørk MH, Zoega H, Leinonen MK, et al. Association of prenatal exposure to antiseizure medication with risk of autism and intellectual disability. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(7):672-681. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen J, Pedersen L, Sun Y, Dreier JW, Brikell I, Dalsgaard S. Association of prenatal exposure to valproate and other antiepileptic drugs with risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e186606. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen MJ, Meador KJ, Browning N, et al. ; NEAD study group . Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure: adaptive and emotional/behavioral functioning at age 6years. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;29(2):308-315. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; NEAD Study Group . Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1597-1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; NEAD Study Group . Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(3):244-252. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70323-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meador KJ, Cohen MJ, Loring DW, et al. ; Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs Investigator Group . Two-year-old cognitive outcomes in children of pregnant women with epilepsy in the maternal outcomes and neurodevelopmental effects of antiepileptic drugs study. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(8):927-936. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huber-Mollema Y, van Iterson L, Oort FJ, Lindhout D, Rodenburg R. Neurocognition after prenatal levetiracetam, lamotrigine, carbamazepine or valproate exposure. J Neurol. 2020;267(6):1724-1736. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09764-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elkjær LS, Bech BH, Sun Y, Laursen TM, Christensen J. Association between prenatal valproate exposure and performance on standardized language and mathematics tests in school-aged children. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(6):663-671. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.5035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daugaard CA, Pedersen L, Sun Y, Dreier JW, Christensen J. Association of prenatal exposure to valproate and other antiepileptic drugs with intellectual disability and delayed childhood milestones. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2025570. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomson T, Battino D, Perucca E. Teratogenicity of antiepileptic drugs. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32(2):246-252. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalsgaard S, Thorsteinsson E, Trabjerg BB, et al. Incidence rates and cumulative incidences of the full spectrum of diagnosed mental disorders in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(2):155-164. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coviello V, Boggess M. Cumulative incidence estimation in the presence of competing risks. Stata J. 2004;4(2):103-112. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0400400201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedersen CB, Mors O, Bertelsen A, et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):573-581. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood AG, Nadebaum C, Anderson V, et al. Prospective assessment of autism traits in children exposed to antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. Epilepsia. 2015;56(7):1047-1055. doi: 10.1111/epi.13007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veiby G, Daltveit AK, Schjølberg S, et al. Exposure to antiepileptic drugs in utero and child development: a prospective population-based study. Epilepsia. 2013;54(8):1462-1472. doi: 10.1111/epi.12226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deshmukh U, Adams J, Macklin EA, et al. Behavioral outcomes in children exposed prenatally to lamotrigine, valproate, or carbamazepine. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2016;54:5-14. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Ijzendoorn MH, Rutgers AH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, et al. Parental sensitivity and attachment in children with autism spectrum disorder: comparison with children with mental retardation, with language delays, and with typical development. Child Dev. 2007;78(2):597-608. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF, Desai RJ, et al. Topiramate use early in pregnancy and the risk of oral clefts: a pregnancy cohort study. Neurology. 2018;90(4):e342-e351. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt S, Russell A, Smithson WH, et al. ; UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register . Topiramate in pregnancy: preliminary experience from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. Neurology. 2008;71(4):272-276. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000318293.28278.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skurtveit S, Selmer R, Tverdal A, Furu K, Nystad W, Handal M. Drug exposure: inclusion of dispensed drugs before pregnancy may lead to underestimation of risk associations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(9):964-972. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bromley RL, Calderbank R, Cheyne CP, et al. ; UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register . Cognition in school-age children exposed to levetiracetam, topiramate, or sodium valproate. Neurology. 2016;87(18):1943-1953. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rihtman T, Parush S, Ornoy A. Preliminary findings of the developmental effects of in utero exposure to topiramate. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;34(3):308-311. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bech LF, Polcwiartek C, Kragholm K, et al. In utero exposure to antiepileptic drugs is associated with learning disabilities among offspring. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(12):1324-1331. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knight R, Craig J, Irwin B, Wittkowski A, Bromley RL. Adaptive behaviour in children exposed to topiramate in the womb: an observational cohort study. Seizure. 2023;105:56-64. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2023.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knight R, Wittkowski A, Bromley RL. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children exposed to newer antiseizure medications: a systematic review. Epilepsia. 2021;62(8):1765-1779. doi: 10.1111/epi.16953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cummings C, Stewart M, Stevenson M, Morrow J, Nelson J. Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to lamotrigine, sodium valproate and carbamazepine. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(7):643-647. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.176990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olesen C, Søndergaard C, Thrane N, Nielsen GL, de Jong-van den Berg L, Olsen J; EuroMAP Group . Do pregnant women report use of dispensed medications? Epidemiology. 2001;12(5):497-501. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200109000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pottegård A, Schmidt SAJ, Wallach-Kildemoes H, Sørensen HT, Hallas J, Schmidt M. Data resource profile: The Danish National Prescription Registry. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):798-798f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Information Available in SCAN-AED From Each Country to Determine Maternal Epilepsy Status

eTable 2. List of ICD-10 codes and Corresponding Disorders Included in the 13 Subgroups of Psychiatric Disorders

eTable 3. Average Length of Follow-up by ASM Exposure Groups

eTable 4. Cumulative Incidence of Psychiatric Disorders at Age 10 Years in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on 38 661 Children of Mothers With Epilepsy in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017)

eTable 5. Cumulative Incidence of Psychiatric Disorders at Age 18 Years in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on 38 661 Children of Mothers With Epilepsy in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017)

eTable 6. Country-Specific Incidence Rates, Hazard Ratios, and Cumulative Incidence of Specific Psychiatric Disorders in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on Children Born in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017)

eTable 7. Incidence Rates, Hazard Ratios (HR) and Cumulative Incidence at Age 10 and 18 Year of the Combined Psychiatric Endpoint in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on 25 139 Children of Mothers With Active Epilepsy in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017)

eTable 8. Incidence Rates, Hazard Ratios (HR) and Cumulative Incidence at Age 10 and 18 Year of the Combined Psychiatric Endpoint in Children Exposed (at Least Two Prescriptions) and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on 38 661 Children of Mothers With Epilepsy in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017)

eTable 9. Age-Restricted Analysis of Specific Psychiatric Disorders in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Antiseizure Medication (ASM) During Pregnancy, Based on Children Born in Five Nordic Countries (1996-2017

eFigure. Flowchart of the study population

Data Sharing Statement