Abstract

Upon nutrient limitation, budding yeast of Saccharomyces cerevisiae shift from fast growth (the log stage) to quiescence (the stationary stage). This shift is accompanied by liquid-liquid phase separation in the membrane of the vacuole, an endosomal organelle. Recent work indicates that the resulting micrometer-scale domains in vacuole membranes enable yeast to survive periods of stress. An outstanding question is which molecular changes might cause this membrane phase separation. Here, we conduct lipidomics of vacuole membranes in both the log and stationary stages. Isolation of pure vacuole membranes is challenging in the stationary stage, when lipid droplets are in close contact with vacuoles. Immuno-isolation has previously been shown to successfully purify log-stage vacuole membranes with high organelle specificity, but it was not previously possible to immuno-isolate stationary-stage vacuole membranes. Here, we develop Mam3 as a bait protein for vacuole immuno-isolation, and demonstrate low contamination by non-vacuolar membranes. We find that stationary-stage vacuole membranes contain surprisingly high fractions of phosphatidylcholine lipids (∼40%), roughly twice as much as log-stage membranes. Moreover, in the stationary stage, these lipids have higher melting temperatures, due to longer and more saturated acyl chains. Another surprise is that no significant change in sterol content is observed. These lipidomic changes, which are largely reflected on the whole-cell level, fit within the predominant view that phase separation in membranes requires at least three types of molecules to be present: lipids with high melting temperatures, lipids with low melting temperatures, and sterols.

Significance

When budding yeast shift from growth to quiescence, the membrane of one of their organelles (the vacuole) undergoes liquid-liquid phase separation. What changes in the membrane’s lipids cause this phase transition? Here, we conduct lipidomics of immuno-isolated vacuole membranes. We analyze our data in the context of lipid melting temperatures, inspired by observations that liquid-liquid phase separation in model membranes requires a mixture of lipids with high melting temperatures, lipids with low melting temperatures, and sterols. We find that phase-separated vacuole membranes have higher concentrations of phosphatidylcholine lipids, and that those lipids have higher melting temperatures. To conduct our experiments, we developed a tagged version of a protein (Mam3) for immuno-isolation of vacuole membranes.

Introduction

During normal growth, cells undergo enormous changes as they adapt to their environment and pass through a sequence of distinct metabolic states (1). For example, when certain nutrients become limiting, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (henceforth “yeast”) transition away from fermentative, exponential growth (log stage), through respiratory growth (diauxic shift), to reach a quiescent state (stationary stage) (2). The shift from the logarithmic to the stationary stage is accompanied by striking changes in the yeast vacuole, the functional equivalent of the lysosome in higher eukaryotes. Multiple, small vacuoles fuse so that most cells contain only one large vacuole ((3), and reviewed in (4)), and the vacuole membrane undergoes liquid-liquid phase separation (Fig. 1) (5). As a result, in the stationary stage, the vacuole membrane contains micrometer-scale domains that are enriched in particular lipids and proteins (6,7,8,9). This phase transition is reversible, with a transition temperature roughly 15°C above the yeast’s growth temperature (10). Recent studies suggest that phase-separated domains in vacuole membranes regulate the metabolic response of yeast to nutrient limitation through the TORC1 pathway, which regulates protein synthesis, autophagy, lipophagy, and other processes (8,9,11,12,13,14).

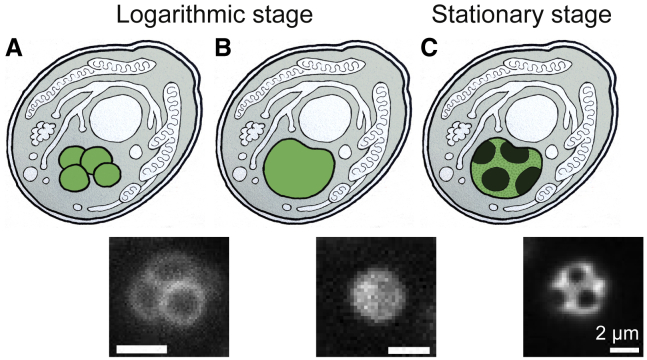

Figure 1.

(A) In nutrient-rich media, yeast cultures grow exponentially. In this logarithmic stage, each cell contains multiple small vacuoles, the lysosomal organelle of yeast. (B) As nutrients become limited, vacuoles fuse. (C) Eventually, yeast enter the stationary stage in which the vacuole membrane phase separates into micrometer-scale, coexisting liquid phases. Corresponding fluorescence micrographs are shown below each schematic, with scale bars representing 2 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

An outstanding question in the field has been what the molecular basis is for phase separation in the vacuole membrane. Here, we investigate changes in the lipidome of the vacuole as yeast enter the stationary stage. We expect the lipidome to be important because the mutations that perturb phase separation of the vacuole involve lipid trafficking and metabolism (8,9,15). Although our experiments do not address the potential contribution of proteins to membrane phase separation (16,17), we note that treatment of cells with cycloheximide, which inhibits protein translation, increases the prevalence of phase-separated vacuoles within 3 h (18).

We expect to observe changes in vacuole lipidomes from the log to the stationary stage because log-stage vacuole membranes do not phase separate over large shifts in temperature from 30°C to 5°C, whereas stationary-stage vacuole membranes do, even when they are grown over a range of growth temperatures (10). However, we do not necessarily expect the lipidomic changes that drive phase separation to be large. Phase transitions are an effective means of amplifying small signals.

What types of changes do we expect to see in the lipidome? In the past, researchers have focused on ergosterol, the predominant sterol in fungi and many protozoans. Multicomponent model membranes containing ergosterol can separate into coexisting liquid phases (19). Moreover, phase separation in isolated vacuoles is reversed through changes in ergosterol levels (8,10,20). Klose et al. measured whole-cell lipidomes through the growth cycle and found that ergosterol decreased from ∼14 mol % of total lipids in the log stage to ∼10 mol % in the stationary stage (21). However, because most ergosterol is highly enriched in the plasma membrane, it has remained unclear how and to what extent ergosterol in the vacuolar membrane may contribute to membrane phase separation during the stationary stage.

Previous attempts to measure changes in vacuole lipidomes have been limited by the technical challenge of separating vacuole membranes from the membranes of other organelles. This challenge is formidable because vacuoles form stable membrane contacts with other organelles, such as the nuclear envelope, which can co-purify with vacuoles (22,23). Here, we employ an immuno-isolation technique called MemPrep to efficiently separate vacuole membranes from those of other organelles (24,25,26,27,28). We first identify a bait protein that resides only in the membrane of interest and then genomically fuse a cleavable epitope tag to that bait protein. To achieve roughly equal immuno-isolation efficiencies in the log and stationary stages, we use the membrane protein Mam3 as our bait, which isolates highly enriched membranes from both growth stages at sufficient yields for quantitative lipidomic analyses. This allows us to map the differences in the lipid profiles of the vacuole membrane in the logarithmic and the stationary stages. We then put our lipidomic data into context of existing data of the physical properties of lipids.

Materials and methods

Yeast cell culture and microscopy

For lipidomics experiments, we used the plasmid pRE866 (28) and the primers 5′-GAACTTCCAATTATGATGCCAACGGCTCCTCGTCGACCATAAAAAGAGGGGGAGGCGGGGGTGGA-3′ and 5′-GGTTATTATGATGCATGGGCAATTCTTTTGGCATAATCTCTTCAGATGGCGGCGTTAGTATCG-3′, and we generated a S. cerevisiae strain with a bait tag targeted to the C terminus of Mam3 (a vacuolar membrane protein involved in Mg2+ sequestration) (29). A Mam3-bait strain is also available from the MemPrep library (28). The bait tag for immuno-isolation contains a linker region followed by a Myc epitope tag for detection in immunoblotting analysis, a specific cleavage site for the human rhinovirus (HRV) 3C protease for selective elution from the affinity matrix, and three repeats of an FLAG epitope that ensures binding to the affinity matrix. The complete amino acid sequence of the bait tag is: GGGGGGEQKLISEEDLGSGLEVLFQGPGSGDYKDHDGDYKDHDIDYKDDDDK.

From a single colony on a YPD (yeast extract peptone dextrose) agar plate, 3 mL of synthetic complete medium was inoculated. Cells were cultivated for 20 h at 30°C, producing a starter culture. From this starter culture, we inoculated 4 L of synthetic complete medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) = 0.1 and cultivated the cells at 30°C and 220 rpm constant agitation. For yeast in the log stage, cells were cultivated for approximately 8 h, until they reached OD600 = 1 (yielding a total of 4000 OD600·mL). For cultivating yeast to the stationary stage, 2 L of synthetic complete medium were inoculated to OD600 0.1 and cultivated for 48 h. The final OD600 was 8.6 ± 0.4 (yielding a total of 17,200 OD600·mL). We used more biomass for isolations from stationary cells because mechanical cell disruption is less efficient at the stationary stage. In the stationary stage, roughly 80% of vacuole membranes undergo phase separation into micrometer-scale domains (8,9,10, 15).

Yeast were imaged by fluorescence microscopy as described in the supplemental methods section of the Supporting Materials.

Immuno-isolation of microsomes

Microsomes of vacuole membranes and solutions of magnetic beads were produced as briefly described in Fig. 2 and as fully described in the Supporting Materials. Next, 700 μL of the sonicated, crude microsomal vesicle fraction were added to 700 μL of the solution of magnetic beads in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl), for a total volume of 1.4 mL. Vesicles were allowed to bind to the beads (Fig. 2 B) by rotating the tubes for 2 h at 4°C in an overhead rotor at 3 rpm, which avoided excessive formation of air bubbles.

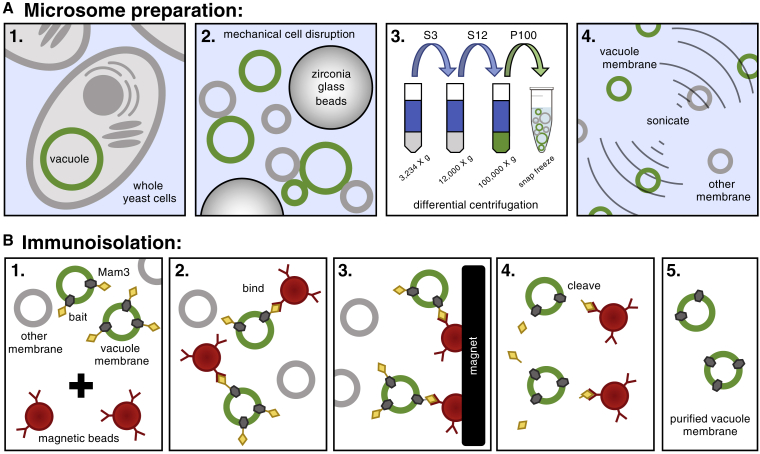

Figure 2.

(A) 1) Yeast cells are cultivated to either the log or stationary stage. 2) Cells are mechanically fragmented with zirconia glass beads using a FastPrep-24 bead beater. 3) A differential centrifugation procedure at 3234 × g, 12,000 × g, and 100,000 × g is performed to deplete cell debris and membranes from other organelles, thereby enriching vacuole membranes in the microsomal fraction. The fraction containing vacuole membranes (either the supernatant, S, or the pellet, P, is retained). 4) Controlled pulses of sonication separates clumps of vesicles and produces smaller microsomes for immuno-isolation (28). Items are not drawn to scale. (B) 1) Top: the microsome solution is enriched in vacuole membranes, which are labeled with a bait tag (myc-3C-3xFLAG) attached to the Mam3 protein. Bottom: microsomes are mixed with magnetic beads coated at sub-saturating densities with a mouse anti-FLAG antibody. 2) Antibody-coated magnetic beads bind to Mam3 in vacuole membranes, but not to other membranes. 3) For washing, the affinity matrix (magnetic beads) is immobilized by a magnet, the buffer with all unbound material is removed, and fresh, urea-containing buffer is added. The affinity matrix is serially washed and agitated in the absence of a magnetic field to ensure proper mixing and removal of unbound membrane vesicles. 4) Vacuole membranes are cleaved from the beads with affinity-purified HRV-3C protease. 5) Removal of the magnetic beads leaves purified vacuole membranes for lipidomics. To see this figure in color, go online.

Magnetic beads and the membranes bound to them were collected after a series of washes (Fig. 2 B). To this end, the tubes were placed in a magnetic rack and the supernatants were removed. The magnetic beads were washed twice with 1.4 mL of wash buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA, 75 mM NaCl, 0.6 M urea), which destabilizes many unspecific protein-protein interactions, and then twice with 1.4 mL of IP buffer. After these washes, the magnetic beads were transferred to a fresh 1.5-mL tube and resuspended with 700 μL of elution buffer (PBS pH 7.4, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 0.04 mg/mL GST-HRV-3C protease).

To elute vesicles from the affinity matrix (Fig. 2 B), the samples were incubated by rotating overhead at 3 rpm for 2 h at 4°C with the HRV-3C protease. The tubes were then placed in a magnetic rack to precipitate the magnetic beads, and the supernatant (eluate) containing the purified vacuole membranes was transferred to fresh tubes. To concentrate the membrane vesicles and to exchange the buffer, the sample was diluted in PBS and transferred to ultracentrifuge tubes. After centrifugation at 264,360 × g for 2 h at 4°C using a Beckman TLA 100.3 rotor, the supernatant was discarded and the pellet containing purified vacuole membranes was resuspended in 200 μL of PBS. Resuspended pellets were transferred to fresh microcentrifuge tubes, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until lipid extraction and mass spectrometry analysis. Procedures for lipid extraction, acquisition of lipidomics data, and processing of lipidomics data are described in the Supporting Materials.

Results

Mam3 is a robust bait protein for immuno-isolation of vacuole membranes

We identified several membrane proteins as candidate “bait proteins” for immuno-isolation of vacuoles in both the log stage and the stationary stage of growth. Immuno-isolation with bait proteins provides a high level of organelle selectivity that is not available by standard flotation methods (30,31). One end of the bait protein (the C terminus) is equipped with a molecular bait (the construct myc-3C-3xFLAG). The bait protein and the membrane in which it resides bind to magnetic beads decorated with anti-FLAG antibodies (Fig. 2 B). The beads are magnetically immobilized and washed extensively with urea-containing buffers. The isolated membranes are then cleaved from the beads (using the GST-HRV-3C protease) and analyzed by shotgun lipidomics. For our application, a robust bait protein (1) must have its C terminus available in the cytosol, (2) contain an intramembrane domain anchoring it to the membrane, (3) localize only to the vacuole, and (4) be expressed at high levels in both the log and stationary stage. Initial guesses can be made about whether given proteins are good candidates for bait proteins by consulting the YeastGFP fusion localization database (https://yeastgfp.yeastgenome.org/), and then fusions must be tested in the lab (32,33).

An obvious candidate for a bait protein was Vph1, which has high expression levels in the log stage (8,34). Vph1 has been extensively used for visualizing vacuole domains (5,7,8,9,10,15), and was previously used by us to demonstrate the utility of MemPrep for isolating vacuole membranes in the log stage (28). However, in the stationary stage, both the expression level of Vph1 and the efficacy of cell lysis are lower (Fig. S1 A-E), resulting in an insufficient yield of membranes upon immuno-isolation via the Vph1-bait construct.

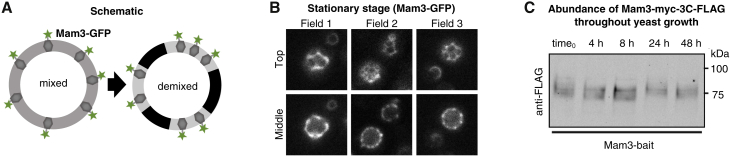

In contrast, Mam3 (∼3230–5890 molecules per cell) proved to be an excellent bait protein (34). We confirmed previous reports that Mam3 localizes to the vacuole membrane (35) by showing that Mam3 colocalizes with FM4-64, a styryl dye that selectively stains vacuole membranes (Fig. S2). In the log stage, when vacuoles do not exhibit domains, Mam3 distributes uniformly on the vacuole membrane. In stationary-stage yeast, Mam3 partitions to only one of the two phases of vacuole membranes (Figs. 3 A–B and S3). Specifically, Mam3 partitions to the same phase as Vph1, which Toulmay and Prinz identified as a liquid disordered (Ld) phase (Fig. S4) (8). Expression levels of Mam3 are high in both the log and stationary stages (Fig. 3 C). Mam3 outperformed four other candidates for bait proteins (Ypq2, Sna4, Ybt1, and YBR241C) carrying the same myc-3C-3xFLAG bait tag. We would expect all of these proteins to preferentially partition to the Ld phase.

Figure 3.

(A) In the log stage of growth, lipids and proteins appear uniformly distributed in vacuole membranes of yeast. Mam3, a transmembrane protein in the vacuole membrane, was produced from its endogenous promoter and equipped at its C terminus either with a bait tag for immuno-isolation or with GFP for fluorescence microscopy. (B) In vivo fluorescence micrographs of yeast showing that, in the stationary stage (after 48 h of growth), the vacuole membrane phase separates into two liquid phases. Mam3-GFP partitions into only one of these phases (identified as the Ld phase). Micrographs were taken at room temperature at both the top (“Top”) and the midplane (“Middle”) of vacuoles for each field of view. Wider, representative fields of view are shown in Fig. S3, and corresponding images for Vph1-GFP are in Fig. S4. (C) Immunoblot showing robust and stable expression levels of Mam3-bait. Synthetic complete medium was inoculated to an OD600 of 0.1 and cells were harvested by centrifugation after cultivation for 0, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h. The immunoblot was visualized using anti-FLAG and fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies, which bind the myc-3C-3xFLAG bait tag on Mam3. Bands for Mam3-bait are shown in the log (early times) and stationary stage (late times), and positions of molecular weight markers are indicated for reference. To see this figure in color, go online.

For completeness, we attempted to find complementary bait proteins that preferentially partition to the opposite phase (the liquid ordered (Lo) phase) of vacuole membranes in the stationary stage. None were found to be good candidates. For example, the protein Gtr2 partitions to the Lo phase in yeast vacuole membranes (8). We find that membrane fragments isolated with a bait attached to Gtr2 proteins contain low amounts of proteins known to reside in vacuole membranes (Vph1 and Vac8); the Gtr2 bait protein does not isolate enough vacuole membrane to analyze by lipidomics (Fig. S5). To date, the only other protein known to preferentially partition to the Lo phase of vacuole membranes is Ivy1 (8). Because Ivy1 is an inverted BAR protein rather than a transmembrane protein, it is an unsuitable bait protein.

Low contamination by non-vacuolar proteins and lipids

A key challenge in isolating pure organellar membranes is that most organelles are in physical contact with other organelles, which can contaminate membrane samples. Most previous isolation attempts have been based on the protocol pioneered by Uchida et al. in which yeast are converted into spheroplasts and mildly lysed, and then vacuole membranes are enriched by differential centrifugation and density centrifugation (30, 36, 37) (see Table S1 for comparisons). Zinser et al. noted that lipid droplets “seemed to adhere” to vacuole membranes isolated by this method (7, 31). The density gradient method of separating vacuole membranes is relatively insensitive to contamination by other types of organelles. When Tuller et al. isolated vacuole membranes, and they found 0.5% contamination by plasma membranes and 5.5% contamination by cardiolipins, a lipid specific to mitochondria (37). Likewise, Schneiter et al. reported that a vacuolar marker protein was enriched ∼15-fold in their vacuolar membrane preparations, with some contamination from the ER and the outer mitochondrial membrane (25).

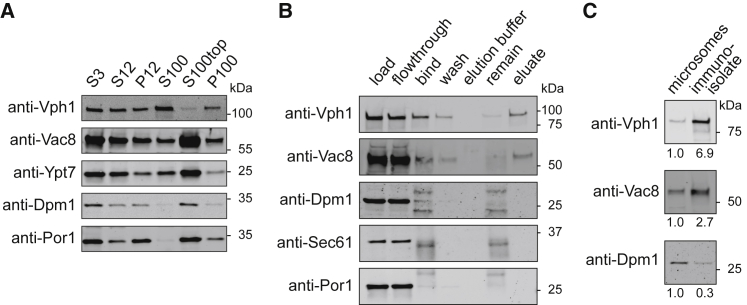

Here, we couple a classical differential centrifugation approach with a sonication step that breaks up vesicle aggregates and produces smaller microsomes, from which vacuolar membranes are then purified by immuno-isolation (Fig. 2). We benchmark the purity of isolated vacuole membranes by verifying that protein markers for vacuoles are enriched in post-immuno-isolation fractions and that markers for other organelles are depleted. For example, Dpm1, which localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum, and Por1, which localizes to the mitochondrial outer membrane, are initially present after sonication of microsomes (Fig. 4 B; “load”) and are removed after immuno-isolation (Fig. 4 B; “eluate”). In contrast, Vac8 and Vph1, which localize to the vacuole, are enriched in the immuno-isolation eluate relative to other proteins (Fig. 4 B,C). Mam3 was not used to evaluate enrichment because the FLAG epitope is cleaved off to release vacuole membranes from the magnetic beads, which means that the Mam3 bait protein cannot be detected with anti-FLAG antibodies after elution.

Figure 4.

Immuno-isolation from cells expressing the Mam3-bait construct. (A) After differential centrifugation, proteins that reside in membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum (Dpm1) and mitochondria (Por1) are present in microsome preparations of yeast (P100 column), as reported by anti-Dpm1 and anti-Por1 immunoblots. (B) P100 microsomes are sonicated and used as input for the immuno-isolation (load). Bands for vacuole markers (Vph1 and Vac8) show binding to antibody-coated magnetic beads (“bind” column), mitigating substantial loss in the flowthrough step (“flowthrough” column). The anti-Dpm1 immunoblot shows two additional bands in the fractions containing magnetic beads (in the “bind” and “remain” columns) originating from the FLAG antibody light chain (∼25 kDa) and the coating of protein G (∼37 kDa). Protein G also leads to a band in the anti-Sec61 and anti-Por1 immunoblots. Immuno-isolation removes membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria (seen by an absence of Dpm1, Sec61, and Por1 in the “eluate” column) and retains only vacuole membranes for lipidomics (seen by bands for Vac8 and Vph1 in the eluate column). (C) Enrichment of organelle protein markers in immuno-isolates over crude microsomes was quantified from immunoblot signals loaded from equal amounts of total protein (0.45 μg).

We also evaluated the purity of isolated vacuole membranes by assessing contamination by lipids known to reside in other organelles. We find that only ∼1% of lipids in isolated membranes (0.8% ± 0.4%) contain cardiolipins from mitochondria. Similarly, TAG (triacylglycerol) and ergosterol esters are “storage lipids” found in the hydrophobic core of lipid droplets (9). For yeast in the log stage, we find that only ∼2.5% of all lipids of immuno-isolated vacuoles are TAG, and <1% are ergosterol esters (Fig. S6). In comparison, in whole-cell extracts of the same cells, we find 9% TAG and 5% ergosterol esters (Fig. S7), in agreement with literature values of 10% ± 1% TAG for equivalent yeast and conditions (38). A characteristic feature of vacuole membranes in the log stage of growth is the almost complete absence of phosphatidic acid (PA) (28), which we confirm for vacuole membranes isolated using the Mam3 bait (Fig. 5 A).

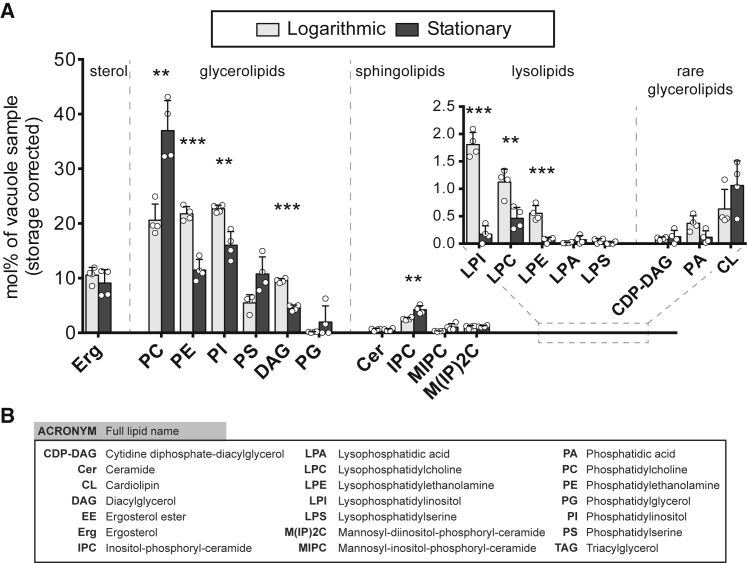

Figure 5.

(A) Abundances of membrane lipids in yeast vacuole membranes in the logarithmic and stationary stages of growth. A large increase is observed in PC lipids. Concomitant decreases are observed in PE, PI, and DAG lipids. Error bars are standard deviations of four vacuole samples immuno-isolated on different days; individual data points are shown by white circles. Data exclude storage lipids (ergosterol ester and triacylglycerol), which are attributed to lipid droplets. Corresponding graphs that include storage lipids are in Fig. S6 and full datasets are in the supporting information. Statistical significance was tested by multiple t-tests correcting for multiple comparisons (method of Benjamini et al. (50)), with a false discovery rate Q = 1%, without assuming consistent standard deviations. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. (B) Acronyms of lipid types.

Isolation of pure vacuole membranes is particularly challenging in the stationary stage, when lipid droplets are produced in high numbers and are in intimate contact with vacuole membranes (7,9,15,39,40). Uptake of lipid droplets into the vacuole lumen, referred to as lipophagy (39) or microlipophagy (41), occurs upon nitrogen starvation or acute glucose limitation and is associated with liquid-liquid phase separation of vacuole membranes (39,41,42,43,44,45).

Nevertheless, we still find low contamination in immuno-isolated vacuole membranes from yeast in the stationary stage, which contain ∼13% TAG and ∼0.5% ergosterol esters (Fig. S6). In comparison, in whole-cell extracts from the same cells, we find three times more TAG (>35%) and an order of magnitude more ergosterol esters (>6%) (Fig. S7). High levels of ergosterol esters persist in vacuoles separated by density gradient methods from log-stage yeast grown in YPD media (31), and may be even higher for equivalent yeast grown in synthetic complete media (38). These data highlight the value of isolating vacuole membranes by immuno-isolation. The difference in depletion levels between TAG and ergosterol ester in our vacuole membrane preparations compared with the corresponding whole-cell lipidomes (∼threefold for TAGs and >10-fold for ergosterol esters) may reflect different rates of lipophagy for TAG- and ergosterol ester-enriched lipid droplets, and/or different turnover rates of these storage lipids in vacuoles. Because the amount of TAG we observe in stationary-stage vacuole preparations exceeds the solubility of TAG in bilayers, which is ∼3% in glycerolipid membranes and likely even lower in membranes containing sterols (46,47), some of the TAG (and perhaps, to a lesser extent, some other lipid types) in our stationary-stage samples likely originates from lipid droplets. In the sections below, we consider storage lipids as non-membrane lipids and exclude them from the discussion.

In general, breaking contact sites between organelles within the MemPrep strategy for immuno-isolation produces highly purified organelle-specific membrane preparations. For example, the strategy results in an unprecedented ∼25-fold enrichment of ER proteins over the cell lysate (28). However, like every technique, it has tradeoffs. As noted by Zinser and Daum, “rupture of intact vacuoles may liberate proteases” (48). Therefore, we perform all steps of MemPrep at 4°C; every increase in temperature of 10°C doubles the rate at which proteases degrade proteins. This constraint prevents us from isolating membranes from the same population of vacuoles at two temperatures. In the future, we hope to find a way to isolate membranes at both a low temperature (at which the membrane phase separates) and a high temperature (at which the membrane is uniform).

Logarithmic stage lipidomes have high levels of PC, PE, and PI lipids

We quantified the lipidome for ∼400 individual lipid species, in ∼20 lipid classes. The list of relevant lipids is shorter in yeast than in many other cell types because yeast can synthesize only mono-unsaturated fatty acids, such that yeast glycerolipids typically contain at most two unsaturated bonds, one in each chain (49). In general, the phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and phosphatidylinositol (PI) lipid classes each constitute ∼20% of the log-stage vacuole lipidome (Fig. 5). Lipidomes of log-stage vacuole membranes immuno-isolated using the Mam3-bait are in excellent agreement with those we previously isolated with a Vph1-bait (Fig. S8) (28). It is difficult to assess whether these lipidomes agree with data determined by more traditional methods. Although Zinser et al. (31) reported that levels of PC lipids were twice the level of PE or PI lipids in log-stage vacuoles, it is unclear if the yeast they used were grown to early log stage or a later stage. Whole-cell lipidomes by Reinhard et al. (38) imply that the difference cannot be simply ascribed to the use of YPD media by Zinser and coworkers versus the synthetic complete media used here.

The importance of isolating vacuoles from whole-cell mixtures is reflected in differences between their lipidomes. For log-stage cells grown in synthetic complete medium, the fraction of IPC (inositolphosphoryl-ceramide) and PA lipids are roughly two and 10 times greater in the whole cell, respectively, whereas the fraction of DAG (diacylglycerol) lipids is roughly two times higher in the vacuole than the whole cell (21,38).

Phase separation in vacuole membranes is not likely due to an increase in ergosterol

A central question is why log-stage vacuole membranes do not phase separate, whereas stationary-stage membranes do. Ergosterol is the major sterol in yeast, and it has been suggested that phase separation of vacuole membranes could be due to an increase in ergosterol (8). An increase in ergosterol would be consistent with a report that the ratio of filipin staining of sterols in vacuole versus plasma membranes is higher in the stationary stage than the log stage, although vacuole and plasma membrane levels were not measured independently (10,15). It would also be consistent with the expectation that esterified sterols in lipid droplets are mobilized in the stationary stage by lipophagy, which is required for the maintenance of phase separation in the vacuole membrane (20,24,36,40).

Here, we find statistically equal mole fractions of ergosterol in vacuole membranes in the log and stationary stages: 10% ± 1% in the log stage and 9% ± 2% in the stationary stage (Fig. 5). Uncertainties represent standard deviations for four independent experiments of each type, and the data exclude storage lipids of ergosterol esters and TAGs. Sterol concentrations in this range (∼10%) are often sufficient for separation of model membranes into two liquid phases (51,52,53,54,55,56,57). Higher levels are not necessarily better at promoting coexisting liquid phases; the solubility limit of ergosterol in membranes of lipids with an average of one unsaturation is only 25%–35% (58,59,60,61), and solubility may be lower when lipid unsaturation is higher, as in biological membranes.

We find that ergosterol fractions in yeast whole-cell extracts, as opposed to only the vacuole membrane, are also ∼10% in both the log stage and the stationary stage (Fig. S7). Similarly, Klose et al. reported mole fractions of ergosterol of 13% and 11% in whole-cell extracts from the log and stationary stage, respectively, with uncertainties on the order of 0.5% (21).

We cannot rule out that immuno-isolation with Mam3 under-samples the Lo phase (which contains higher concentrations of ergosterol per unit area than the Ld phase, based on brighter staining by filipin (8)). Nevertheless, our conclusion that vacuole phase separation is not likely driven by an increase in ergosterol is consistent with other results in yeast; we previously found that log-stage vacuole membranes phase separate upon depletion (rather than addition) of ergosterol (10). Other results in the literature are more difficult to interpret. It is not known whether ergosterol and other lipids move into yeast vacuoles or out of them when sterol synthesis and transport are impaired (9,11,12,15), when lipid droplets are perturbed (9,13), or when drugs are applied to manipulate sterols (8,20) (all of which can disrupt the formation or maintenance of vacuole membrane domains).

Results from other cell types are not necessarily applicable to yeast. As in yeast vacuoles, depletion of sterol from modified Chinese hamster ovary cells results in plasma membrane domains, and recovery of photobleached lipids is consistent with the domains and the surrounding membrane both being fluid (62). Similarly, depletion of sterol from giant plasma membrane vesicles (GPMVs) of NIH/3T3 murine fibroblasts causes phase separation to persist to higher temperatures (63). Membrane domains in other types of sterol-depleted cells (e.g., (64)) may also prove to be due to phase separation, although it is always important to verify that cells are still living (as in (64)) and to identify when membrane properties such as lipid diffusion, dye partitioning, domain shape, and/or domain coalescence reflect liquid rather than solid phases (as in (65,66,67)). Different results are observed in vesicles derived from other cell types. Depletion of sterol from GPMVs of RBL cells restricts phase separation to lower temperatures (68). Similarly, when phase separation is restricted to lower temperatures in zebrafish GPMVs (because the cells are grown at lower temperature), sterol levels are lower (69). Results from these different cell types are not in conflict; addition and depletion of sterol have been suggested to drive membranes toward opposite ends of tie-lines (away from phase separation and toward a single, uniform phase), based on observations in GPMVs of RBL-2H3 cells (70), CH27 cells (71), and model membranes (19,51,63,72).

Changes in the vacuole lipidome from the log stage to the stationary stage

If phase separation in vacuole membranes is not due to an increase (or even a change) in the fraction of ergosterol, could it be due to changes in other lipids? In the remainder of this paper, commencing with Fig. 5, we explore how the changes in the vacuole lipidome from the log stage to the stationary stage might contribute to membrane phase separation in the vacuole membrane. A first impression from Fig. 5 is that the lipid populations “are more alike than they are different” (to quote Burns et al. (69), who compared lipidomes from zebrafish GPMVs that phase separate with ones that do not). It makes sense that the two lipidomes are similar, because the cells from which they are extracted are separated by only 2 days of cultivation.

Nevertheless, significant changes in the lipidomes are apparent. The most dramatic change is the increase in the fraction of PC lipids. This jump is notable because PCs are a large fraction of the vacuole’s lipids. We observe concomitant minor decreases in PE, PI, and DAG lipids, which mirror decreases in the whole-cell lipidome (Figs. S6 and S7). Sphingolipids constitute a much smaller fraction of vacuole membrane lipids; we find that the total mole fraction is in the range of only 5%–10%, even in the stationary stage. That said, within this small fraction, there is an increase in IPC sphingolipids from about 2% to 4% from the log stage to the stationary stage (Fig. 5). This increase is not reflected in whole-cell lipid extracts, of which ∼2% are IPC sphingolipids in the stationary stage (Fig. S7). Even though the fraction of sphingolipids is small, they have often been associated with membrane domains in the literature. For example, model membranes containing sphingolipids exhibit phase behavior at higher temperatures than their counterparts with PC lipids of equal chain lengths (52). Similarly, although 10% of GUVs phase separate at 25°C when they are made from whole lipid extracts of yeast (which is admittedly a small percentage), none of the GUVs phase separate when the yeast undergo mutations that reduce sphingolipids and long-chain fatty acids (eloΔ) or prevent C4 hydroxylation of sphingoid bases (sur2Δ) (73).

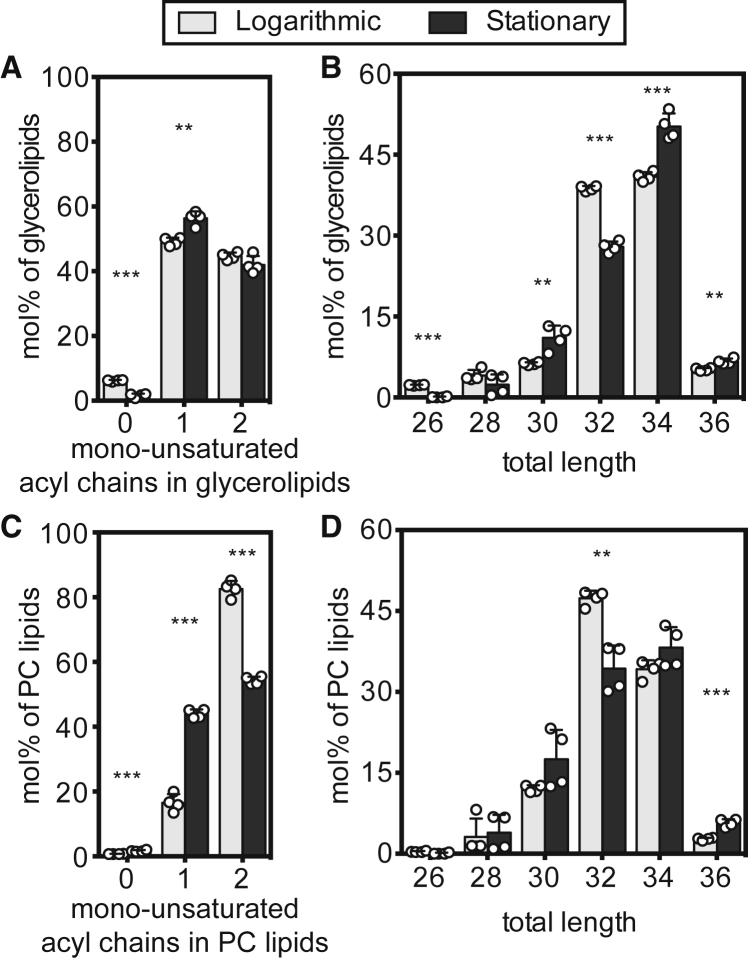

What about the fatty acid chains of the lipids? Roughly 30 mol % of the acyl chains found in vacuolar lipids are saturated (with no double bonds), in both the logarithmic and stationary stage (Fig. S14). Stated another way, the average number of double bonds per lipid acyl chain in vacuolar membrane lipids (excluding TAG, ergosterol esters, and ergosterol) remains constant from the log stage (0.66 ± 0.01) to the stationary stage (0.65 ± 0.00). Even when we restrict the analysis to glycerolipids with two fatty acyl chains, only a minor increase in lipid saturation is apparent (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Molecular features of glycerolipids and PC lipids in vacuole membranes. (A) Number of mono-unsaturated fatty acyl chains in glycerolipids that have two acyl chains (CDP-DAG, DAG, PA, PC, PE, PG, PI, PS) in the log (gray) and stationary (black) stages. These lipids constitute 81% ± 2% and 82% ± 4% of all membrane lipids in the log- and stationary-stage vacuole membrane, respectively. (B) Total length of both acyl chains in glycerolipids with two chains. A shift from the log stage to the stationary stage is accompanied by a small increase in lipid chain lengths. (C) Total number of double bonds in PC lipids (PC). Number of mono-unsaturated fatty acyl chains in PC lipids. A shift from the log to the stationary stage is accompanied by a large decrease in the proportion of PC lipids with two mono-unsaturated acyl chains. (D) Total length of acyl chains in PC lipids. Statistical significance was tested by multiple t-tests correcting for multiple comparisons (method of Benjamini et al. (50)), with a false discovery rate Q = 1%, without assuming consistent standard deviations. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Few lipids in vacuole membranes have more than one chain that is saturated (Fig. 6). This leads to the question of whether a Lo phase could arise in a membrane that has few fully saturated lipids. The answer is yes, for two reasons. The first is tautological: coexisting liquid phases have previously been found in GUVs reconstituted from rat synaptic membranes (74) and in GPMV membranes derived from zebrafish cells (69) and RBL cells (68), all of which have few fully saturated lipids. The second is that biological membranes contain substantial amounts of protein (75), which may increase lipid order (76).

Although the percentage of saturated fatty acid chains remains roughly constant from the log stage to the stationary stage, there is a large shift in how these chains are distributed between different lipid types (Fig. S14). This result highlights that it is essential to evaluate different lipid classes, because average values can obscure shifts. For example, when PC lipids are analyzed on their own (because there is a large increase in PC lipids from the log to the stationary stage), the percentage of PC lipids that contain only one unsaturated chain significantly increases from 17% ± 3% in the log-stage vacuoles to 44% ± 1% in the stationary-stage vacuoles (Fig. 6 C). A concomitant decrease in lipids with two unsaturated chains occurs, from 83% ± 3% in the log stage to 54% ± 1% in the stationary stage (Fig. 6 C).

Similarly, the average length per lipid chain for all lipids in the vacuole (excluding TAG, ergosterol esters, and ergosterol) remains constant from the log stage (16.6 ± 0.1 carbons) to the stationary stage (16.9 ± 0.2 carbons), whereas, by restricting the data to glycerolipids with two chains (Fig. 6 B) or PC lipids (Fig. 6 D), it is clear that chain lengths slightly increase for these lipids, largely due to a decrease in lipids with a total acyl chain length of 32 carbons, in favor of longer lipids. Yeasts employ various mechanisms to remodel their lipidomes. Synthesis of PC lipids can occur via the PE-methylation pathway or the Kennedy pathway, resulting in different lipid profiles (77). Remodeling of existing populations of PC lipids can occur through exchange of acyl chains after cleavage by phospholipase A or B, or, to a smaller extent, lipid turnover (78,79,80).

PC lipids shift to higher melting temperatures in the stationary stage

PC lipids are abundant. Like PE and PI, this lipid class constitutes a large fraction (20%–25%) of all lipids in log-stage vacuole membranes. When yeast transition to the stationary stage, the proportion of PC lipids shoots up to ∼40% of vacuolar lipids, the largest increase of any lipid type. A similar increase in the PC-to-PE ratio occurs in the lipidome of whole yeast cells (81). In both cases, the increase may be due to increased availability of methionine for PE-methylation to form PC when protein synthesis declines (81). Therefore, it seems likely that the onset of phase separation of vacuole membranes is linked to changes in the fraction of PC lipids and their acyl chain compositions. This result is consistent with the observation that yeast knockouts of OPI3 and CHO2 (which diminish synthesis of PC lipids (82,83)) exhibit a smaller proportion of vacuoles with domains (8). The mole fractions of every PC lipid in log and stationary-stage vacuoles are provided in Data File S1, with the caveat that fatty acids with odd numbers of carbons should be excluded. We confirmed that these odd-numbered fatty acids are not relevant by analyzing tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) fatty acid and headgroup fragmentation.

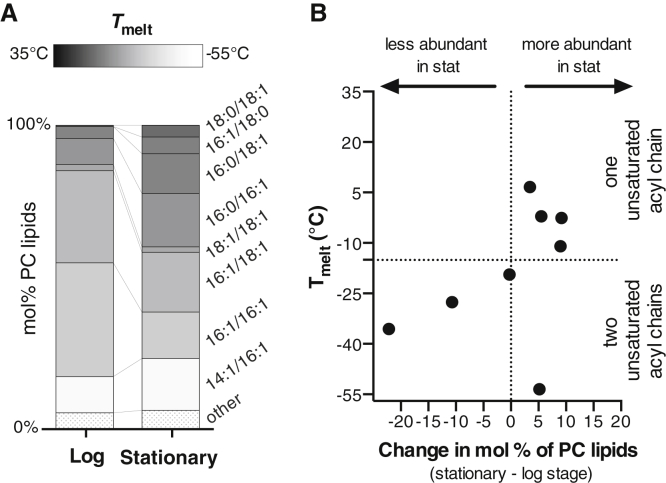

To gain intuition about how the membrane properties of vacuole membranes might be influenced by their diverse set of PC lipids, we mapped the lipidomics data onto a physical parameter, the temperature at which each lipid melts from the gel to the fluid phase (Tmelt). Melting temperatures are related to phase separation. Model membranes phase separate into micrometer-scale domains when at least three types of lipids are present: a sterol, a lipid with a high Tmelt, and a lipid with a low Tmelt (51,52,54,55,56,72,84). High and low should be interpreted as relative values rather than absolute values, based on results from model GUV membranes (51) and cell-derived GPMVs (69).

Lipid melting temperatures are affected by the lipid’s headgroup, chain length, and chain unsaturation (85,86,87). When only one of the lipids in a model membrane is varied, a linear relationship can result between the lipid’s Tmelt and the temperature at which the membrane demixes into liquid phases (51,88). Of course, yeast vacuole membranes experience changes in more than one lipid type and in the relative fractions of lipid headgroups, which likely breaks simple relationships between Tmelt of lipids and the membrane’s mixing temperature (51,52,89). However, we are unaware of any single physical parameter that is more relevant than Tmelt for characterizing lipid mixtures that phase separate.

The formidable task of compiling Tmelt values of all PC lipids is less onerous for yeast vacuoles than for other cell types because each carbon chain of a yeast glycerolipid has a maximum of one double bond (49). This fact provides a straightforward way to evaluate measurement uncertainties because nonzero entries for polyunsaturated phospholipids in Data File S1 (typically well below 0.2%) must be due to error in the process of assigning lipid identities to mass spectrometry data or are due to fatty acids from the medium. Some Tmelt values are available in the literature (85,87,90,91,92). For many others, we estimated Tmelt values from experimental trends (Tables S2–S4 and Fig. S9). This procedure yielded Tmelt values for 95% of PC lipids in log-stage vacuoles, and 94% in stationary-stage vacuoles.

By compiling all our data on PC lipids (Fig. 7), we find that they undergo significant acyl chain remodeling from the log stage to the stationary stage in terms of their melting temperatures. Values of Tmelt are higher for vacuole PC lipids in the stationary stage compared with the log stage (the weighted average Tmelt is −31°C in the log stage and −24°C in the stationary stage). Graphically, Fig. 7 A shows this shift as an increase in the mole percent of lipids with high Tmelt (dark bands).

Figure 7.

Melting temperatures of PC lipids in vacuole membranes. (A) Tmelt values (represented by gray scale) are higher for PC lipid in the stationary stage than the log stage. Lipids contributing less than 1 mol % are categorized as “other.” (B) From the log to the stationary stage, there is an overall loss of PC lipids with low values of Tmelt (lower left quadrant) and a gain of PC lipids with high values of Tmelt (upper right quadrant). Fig. S10 presents an alternative way of plotting these data.

The increase in Tmelt correlates with an increase in lipid saturation. In the shift from the log to the stationary stage, PC lipids with two unsaturated chains (lower Tmelt) become less abundant, and PCs with one unsaturated chain (higher Tmelt) become more abundant (Figs. 7 B and S10). This large increase in saturation of PC lipids is not reflected in all types of glycerolipids found in vacuole membranes (Fig. S11). Nevertheless, we observe a general trend for each glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid species toward longer acyl chains in the stationary phase (Fig. S11).

The observed increase in average Tmelt of PC lipids is robust to any possible oversampling of the Ld phase by the Mam3 immuno-isolation procedure. Because Lo phases typically contain higher fractions of lipids with higher melting temperatures and orientational order (51,93) sampling more of the Lo phase would be expected to further increase average Tmelt values.

The spread in the distribution of lipid melting temperatures is likely to be as important as the average. This is because phase separation persists to higher temperatures in model membranes when the highest Tmelt is increased (51,89) and when the lowest Tmelt is decreased (88), at least when those lipids have PC headgroups and do not have methylated tails. These literature reports are consistent with work by Levental et al. showing that phase separation persists to higher temperatures in GPMVs of RBL cells when the two phases are the most different, as measured by the generalized polarization of a C-laurdan probe (68). These results can be put into broader context that the addition of any molecule that partitions strongly to only one phase (e.g., a high-Tmelt lipid to the Lo phase and a low-Tmelt lipid to the Ld phase) should lower the free energy required for phase separation (94,95,96).

In the left column of Fig. 7 A, PC lipids in log-stage vacuole membranes cluster around intermediate values of Tmelt. In the stationary stage, some lipids are replaced by lipids with higher values of Tmelt, and some are replaced by lipids with lower values. If the vacuole membrane contained only PC lipids, we would conclude that those membranes would be more likely to phase separate in the stationary stage, because their overall melting temperatures are higher and because the distribution of melting temperatures is broader.

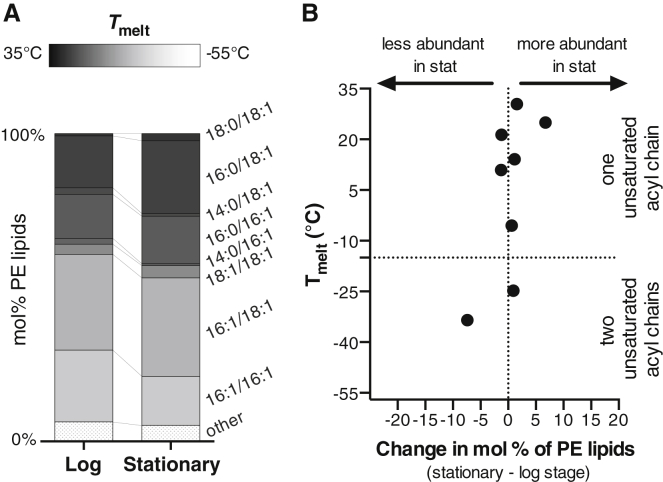

PE lipids have similar melting temperatures in log and stationary stage

PE lipids undergo the largest decrease (from ∼20% to ∼10%) of all lipids in yeast vacuoles. We found melting temperatures of the PE lipids in yeast vacuoles by compiling values in the literature (85,86,97,98) or estimating them (Tables S2 and S3; Fig. S12).

In contrast to PC lipids, the acyl chain composition of PE lipids is not heavily remodeled from the log stage to the stationary stage. This result is seen as a clustering of data points along the vertical dashed line in Fig. 8 B. Accordingly, the melting temperatures of PE lipids change only mildly: the weighted average Tmelt is −9°C and −5°C in the log and stationary stages, respectively. Similarly, by eye from Fig. 8 A, the distribution of Tmelt values for PE lipids are similar in the log stage and the stationary stage.

Figure 8.

Melting temperatures of PE lipids in vacuole membranes. (A) Tmelt values (represented by gray scale) are similar for vacuole PE lipids in the stationary stage and the log stage. Lipids contributing less than 1 mol % are categorized as “other.” (B) Changes in mol % of PE lipids (x axis) with each melting temperature (y axis) are small; data cluster along the vertical line for zero change in mol %.

Trends in Tmelt for every glycerolipid

Literature values for lipid melting temperatures are not available for all lipid types, so plots such as Figs. 7 and 8 cannot be reproduced for all headgroups. The next best option is to apply known trends of how lipid chain length and saturation affects lipid Tmelt ((85,87) and Table S3). We estimate changes in Tmelt from the log to the stationary stage for each lipid headgroup separately because it is not clear that combining datasets for all lipids would yield insight about whether a membrane would be more likely to phase separate. This is because two lipids can have the same melting temperature, but membranes containing those lipids can phase separate at different temperatures. For example, pure bilayers of palmitoyl sphingomyelin, 16:0SM, and dipalmitoyl PC, di(16:0)PC, have the same Tmelt (85,99), but multicomponent model membranes containing 16:0SM phase separate at a higher temperature than membranes containing di(16:0)PC (51,52), possibly because sphingomyelins have additional opportunities to hydrogen bond with the sterol (100,101). Similarly, even though PE lipids have higher melting temperatures than equivalent PC lipids (Fig. S13), sterol (cholesterol) partitioning is lower in PE membranes than in PC membranes (102), implying that interactions between sterols and PE lipids are less favorable.

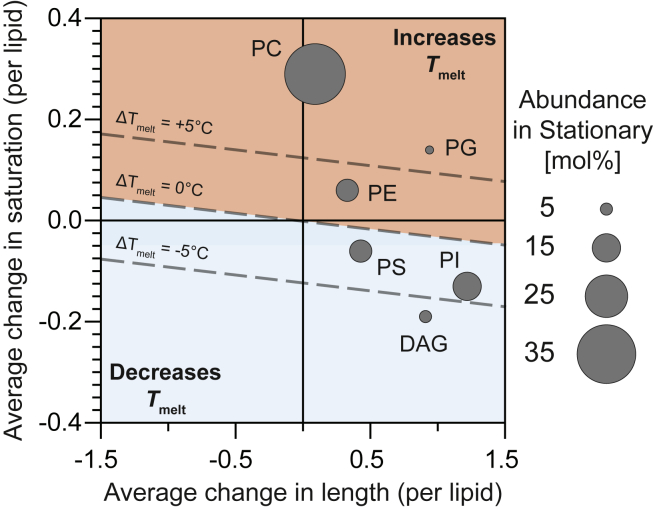

Changes in lipid saturation have much larger effects on melting temperatures than changes in chain length. We find that increasing the average, summed length of both lipid chains by one carbon results in an increase in Tmelt of 3.6°C for PC and PE lipids (because increasing the total length from 32 to 34 carbons results in an increase in Tmelt of 7.2°C, as in Table S5). Increasing the saturation of the lipid by one bond results in an increase in Tmelt of 30.3°C. Therefore, an increase in Tmelt of, say, 5°C can be achieved either by increasing the average total chain length by 5/3.6 = 1.4 carbons or by increasing the average saturation by 5/30.3 = 0.17 bonds (dashed line in Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

At the origin, there is no change in average lipid length (x axis) and no change in average lipid saturation (y axis). Each point represents a different glycerolipid species, and each lipid experiences a change in both length and saturation. The size of each point represents the relative abundance of that lipid class in the stationary stage. Lipids located above the diagonal line of “ΔTmelt = 0” are expected to experience an increase in Tmelt. Those below the line are expected to experience a decrease. To see this figure in color, go online.

We know how chain length and saturation changes from the log to stationary stage for all abundant glycerolipids in yeast vacuoles (PC, PE, PI, PS, PG, and DAG) (Figs. 9 and S11). By assuming that the melting temperatures of all these lipids follow similar trends, we find that Tmelt likely increases for most lipid types during the shift from log to stationary stage. In Fig. 9, changes in chain length or saturation that result in an increase in Tmelt fall within the shaded region toward the top right of the graph, and the area of each symbol represents the abundance (in mol %) of the lipid type in the stationary stage. The largest increase in Tmelt is for PC lipids, which are the most abundant lipids in the stationary stage. Lipids for which Tmelt likely decreases (DAG) have relatively low abundance. Increases in lipid saturation (and, hence, increases in lipid Tmelt and orientational order) have previously been correlated with phase separation persisting to higher temperatures in GPMVs of zebrafish cells (69).

An alternative mechanism by which eukaryotic cells may influence lipid melting temperatures is through the introduction of highly asymmetric chains. Although highly asymmetric lipids can appear in S. cerevisiae membranes (38), here we find no significant change of highly asymmetric lipids in vacuole membranes from the stationary stage (Table S6). In contrast, Burns et al. find that zebrafish GPMVs with lower transition temperatures have more highly asymmetric lipids (69). Similarly, when Schizosaccharomyces japonicus fission yeast cannot produce unsaturated lipids (due to anoxic environments), they increase the fraction of lipids with asymmetric acyl tails, which may maintain membrane fluidity (103). Some yeast (e.g., Schizosaccharomyces pombe) appear to be biochemically unable to use this strategy (103).

It is also possible that sphingolipids contribute to membrane phase separation in stationary-phase vacuoles, even though they are present at low mole percentages. We find an increase in the length and hydroxylation of the sphingolipids (Fig. S11). We previously noted an increase in IPC sphingolipids from ∼2% to ∼4% from the log to the stationary stage (Fig. 5), which is noteworthy because its Tmelt is relatively high (53.4°C as reported by (73)).

Addition of ethanol to isolated, log-stage vacuoles does not cause membrane phase separation

Yeast membranes undergo many changes from the log to the stationary stage that are not captured by lipidomics. For example, as yeast consume glucose, they produce ethanol, some of which partitions into yeast membranes. In model membranes, addition of ethanol results in disordering of lipid acyl chains (104). Lipidomics does not quantify the percent ethanol in membranes. Nevertheless, we can assess whether ethanol on its own is sufficient to cause log-stage vacuole membranes to phase separate. Here, yeast were grown at 30°C in synthetic complete medium (with 4% glucose) for <24 h until the culture reached an optical density of 0.984. Vacuoles were isolated as in (5), incubated on ice in either 10% v/v ethanol for 1.5 h or 20% v/v ethanol for 2 h, and then imaged at room temperature. Neither population of vacuoles showed evidence of phase separation; only one vacuole showed clear evidence of membrane phase separation, which could not be attributed to the addition of ethanol. The result showing that ethanol, on its own, is not sufficient to cause log-stage vacuole membranes to phase separate is consistent with literature reports. Although ethanol enhances phase separation in vacuole membranes in model membranes (by increasing the temperature at which coexisting Lo and Ld phases persist) (96), it suppresses phase separation in GPMVs from rat basal leukemia cells, which have lipid compositions more similar to yeast vacuole membranes (95).

Discussion

This special issue is dedicated to Klaus Gawrisch, who directed the first experiments to quantify ratios of lipids in Lo and Ld phases of ternary model membranes with high accuracy (93). NMR data from those experiments showed that Lo and Ld phases differed primarily in their fractions of phospholipids with high and low melting temperatures (rather than the amount of sterol). This result was previously surmised from semi-quantitative estimates of lipid compositions from area fractions of Lo and Ld phases (51), but the concept that the two phases could be primarily distinguished by their phospholipid content did not gain traction in the community until high quality data from Klaus’s NMR spectrometers were published.

Here, we report a complementary result: demixing of yeast vacuoles into coexisting Lo and Ld phases, which occurs upon a transition from the log to the stationary stage of growth, is accompanied by significant changes in the phospholipid compositions of yeast vacuoles. The fraction of PC lipids roughly doubles. Among the PC lipids, there is a significant increase (7°C) in the average Tmelt of the lipids. PE lipids, which also exhibit an increase in the average Tmelt (4°C), are roughly halved in mole fraction.

In this manuscript, we have analyzed the differences in the vacuole lipidome at two growth stages (the log and the stationary stage) in the context of a single physical variable (the mixing temperature) and how it might affect a single membrane attribute (demixing of the membrane into coexisting liquid phases). Of course, membrane phase separation is only one of many relevant physiological parameters. Cellular lipidomes are also affected by temperature, growth medium, carbon source, anoxia, ethanol adaptation, mutations, and cell stress (69,103,105,106,107,108,109,110). Cells have the potential to adjust their membrane compositions to meet a broad list of inter-related constraints, including lipid packing, thickness, compression, viscosity, permeability, charge, asymmetry, monolayer and bilayer spontaneous curvatures, and avoidance of (and proximity to) nonlamellar phases (69,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122). Likewise, the lipidome is only one of many biochemical attributes that a cell might vary (e.g., the asymmetry, charge, tension, and adhesion of the membrane; the abundance, crowding, condensation, and crosslinking of proteins; and the conditions of the solvent) to enhance or suppress liquid-liquid phase separation of its membranes (57,123,124,125,126,127).

Not all lipidomic changes that we observe in the vacuole are reflected across the whole cell (21), highlighting the importance of isolating organelles. Our ability to isolate yeast vacuoles with low levels of contamination by non-vacuole organelles leverages advances in immuno-isolation (28) and our discovery that Mam3 is a robust bait protein in both the log and stationary stages. Recent advances in simulating the molecular dynamics of complex membranes with many lipid types over long timescales are equally exciting (128,129). We hope that sharing our lipidomic data (Data File S1) will be useful to future modelers in elucidating why stationary-stage vacuole membranes phase separate, whereas log-stage membranes do not.

Conclusions

Here, we establish that Mam3 is a robust bait protein for immuno-isolation of vacuole membranes. Expression levels of Mam3 are high throughout the yeast growth cycle. In the stationary stage, Mam3 partitions into the Ld phase. By conducting lipidomics on isolated vacuole membranes, we find that the shift from the log to the stationary stage of growth is accompanied by large increases in the fraction of PC lipids in the membrane, and that these lipids become longer and more saturated. The resulting increase in melting temperature of these lipids may contribute to demixing of stationary-stage vacuole membranes to form coexisting liquid phases.

Author contributions

A.J.M., C.E.C., C.L.L., J.R., R.E., and S.L.K. designed the research. C.E.C., C.L.L., C.K., and J.R. performed the research. C.L.L., J.R., C.K., R.E., and S.L.K. analyzed the data. A.J.M., C.L.L., J.R., R.E., and S.L.K. wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NSF grant MCB-1925731 to S.L.K., NIH grants GM077349 and GM130644 to A.J.M., European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 866011) to R.E., Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft in the framework of the SFB894 to R.E., Volkswagen Foundation grant #93089 to R.E. and J.R., and a travel grant by The Company of Biologists to C.L.L.

This manuscript is dedicated to Klaus Gawrisch, whose contributions to the biophysical community go beyond his rigorous NMR measurements. His open-mindedness to consider and test unpopular ideas, his generosity in sharing credit through collaborations, and his dedication to mentoring of early-career researchers have continuously elevated the quality of scientific results and the collegiality of scientific culture.

Declaration of interests

C.K. is employed by Lipotype GmbH, a company that conducts quantitative lipidomic services.

Editor: Jeanne Stachowiak.

Footnotes

John Reinhard and Chantelle L. Leveille contributed equally to this work.

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2023.01.009.

Contributor Information

Robert Ernst, Email: robert.ernst@uks.eu.

Sarah L. Keller, Email: slkeller@uw.edu.

Supporting material

Additional data of log-stage whole-cell lipidomes (Fig. S7, logarithmic) and log-stage lipidomes of vacuole membranes immuno-isolated via a Vph1 bait protein (Fig. S8, Vph1-bait) are taken from (1) and highlighted in green. Data in Figure S8 (Mam3-bait) are replotted from Figure S6 (logarithmic). Tabs in the data file show calculated and plotted values for respective figures.

References

- 1.Casanovas A., Sprenger R.R., et al. Ejsing C.S. Quantitative analysis of proteome and lipidome dynamics reveals functional regulation of global lipid metabolism. Chem. Biol. 2015;22:412–425. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werner-Washburne M., Braun E., et al. Singer R.A. Stationary phase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 1993;57:383–401. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.383-401.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiemken A., Matile P., Moor H. Vacuolar dynamics in synchronously budding yeast. Arch. Mikrobiol. 1970;70:89–103. doi: 10.1007/BF00412200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones E.W. Biogenesis and function of the yeast vacuole. Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces. 1997;3:363–470. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rayermann S.P., Rayermann G.E., et al. Keller S.L. Hallmarks of reversible separation of living, unperturbed cell membranes into two liquid phases. Biophys. J. 2017;113:2425–2432. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moor H., Mühlethaler K. Fine structure in frozen-etched yeast cells. J. Cell Biol. 1963;17:609–628. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.3.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moeller C.H., Thomson W.W. An ultrastructural study of the yeast tonoplast during the shift from exponential to stationary phase. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1979;68:28–37. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(79)90139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toulmay A., Prinz W.A. Direct imaging reveals stable, micrometer-scale lipid domains that segregate proteins in live cells. J. Cell Biol. 2013;202:35–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201301039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang C.-W., Miao Y.-H., Chang Y.-S. A sterol-enriched vacuolar microdomain mediates stationary phase lipophagy in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 2014;206:357–366. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201404115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leveille C.L., Cornell C.E., Keller S.L., et al. Yeast cells actively tune their membranes to phase separate at temperatures that scale with growth temperatures. Biophys. J. 2022 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2116007119. 119:e2116007119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murley A., Sarsam R.D., et al. Nunnari J. Ltc1 is an ER-localized sterol transporter and a component of ER–mitochondria and ER–vacuole contacts. J. Cell Biol. 2015;209:539–548. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201502033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murley A., Yamada J., et al. Nunnari J. Sterol transporters at membrane contact sites regulate TORC1 and TORC2 signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2017;216:2679–2689. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201610032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seo A.Y., Lau P.-W., et al. Lippincott-Schwartz J. AMPK and vacuole-associated Atg14p orchestrate μ-lipophagy for energy production and long-term survival under glucose starvation. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.21690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatakeyama R., Péli-Gulli M.P., et al. De Virgilio C. Spatially distinct pools of TORC1 balance protein homeostasis. Mol. Cell. 2019;73:325–338.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuji T., Fujimoto M., et al. Fujimoto T. Niemann-Pick type C proteins promote microautophagy by expanding raft-like membrane domains in the yeast vacuole. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.25960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatterjee S., Maltseva D., et al. Parekh S.H. Lipid-driven condensation and interfacial ordering of FUS. Sci. Adv. 2022;8 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abm7528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H.Y., Chan S.H., et al. Levental I. Coupling of protein condensates to ordered lipid domains determines functional membrane organization. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adf6205. Preprint at. 2022.08.02.502487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toulmay A., Prinz W.A. Direct imaging reveals stable, micrometer-scale lipid domains that segregate proteins in live cells. J. Cell Biol. 2013;202:35–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201301039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beattie M.E., Veatch S.L., et al. Keller S.L. Sterol structure determines miscibility versus melting transitions in lipid vesicles. Biophys. J. 2005;89:1760–1768. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seo A.Y., Sarkleti F., et al. Lippincott-Schwartz J. Vacuole phase-partitioning boosts mitochondria activity and cell lifespan through an inter-organelle lipid pipeline. bioRxiv. 2021 Preprint at. 2021.04.11.439383. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klose C., Surma M.A., et al. Simons K. Flexibility of a eukaryotic lipidome – insights from yeast lipidomics. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan X., Roberts P., et al. Goldfarb D.S. Nucleus–vacuole junctions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are formed through the direct interaction of Vac8p with Nvj1p. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:2445–2457. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.7.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisinski D.D., Gomes Castro I., et al. González Montoro A. Cvm1 is a component of multiple vacuolar contact sites required for sphingolipid homeostasis. J. Cell Biol. 2022;221:e202103048. doi: 10.1083/jcb.202103048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franzusoff A., Lauzé E., Howell K.E. Immuno-isolation of Sec7p-coated transport vesicles from the yeast secretory pathway. Nature. 1992;355:173–175. doi: 10.1038/355173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneiter R., Brügger B., et al. Kohlwein S.D. Electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) analysis of the lipid molecular species composition of yeast subcellular membranes reveals acyl chain-based sorting/remodeling of distinct molecular species en route to the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:741–754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klemm R.W., Ejsing C.S., et al. Simons K. Segregation of sphingolipids and sterols during formation of secretory vesicles at the trans-Golgi network. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:601–612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200901145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Surma M.A., Klose C., et al. Simons K. Generic sorting of raft lipids into secretory vesicles in yeast. Traffic. 2011;12:1139–1147. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinhard J., Starke L., et al. Ernst R. A new technology for isolating organellar membranes provides fingerprints of lipid bilayer stress. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s44318-024-00063-y. Preprint at. 2022.09.15.508072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang R.J., Meng S.-F., et al. Luan S. Conserved mechanism for vacuolar magnesium sequestration in yeast and plant cells. Native Plants. 2022;8:181–190. doi: 10.1038/s41477-021-01087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchida E., Ohsumi Y., Anraku Y. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 1988. Purification of yeast vacuolar membrane H+-ATPase and enzymological discrimination of three ATP-driven proton pumps in Saccharomyces cerevisiae; pp. 544–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zinser E., Sperka-Gottlieb C.D., et al. Daum G. Phospholipid synthesis and lipid composition of subcellular membranes in the unicellular eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:2026–2034. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.2026-2034.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta M.N., Roy I. Elsevier; 2021. Three Phase Partitioning: Applications in Separation and Purification of Biological Molecules and Natural Products. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghaemmaghami S., Huh W.-K., et al. Weissman J.S. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ho B., Baryshnikova A., Brown G.W. Unification of protein abundance datasets yields a quantitative Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteome. Cell Syst. 2018;6:192–205.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huh W.-K., Falvo J.V., et al. O’Shea E.K. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zinser E., Paltauf F., Daum G. Sterol composition of yeast organelle membranes and subcellular distribution of enzymes involved in sterol metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:2853–2858. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2853-2858.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tuller G., Nemec T., et al. Daum G. Lipid composition of subcellular membranes of an FY1679-derived haploid yeast wild-type strain grown on different carbon sources. Yeast. 1999;15:1555–1564. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199910)15:14<1555::AID-YEA479>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinhard J., Mattes C., et al. Ernst R. A quantitative analysis of cellular lipid compositions during acute proteotoxic ER stress reveals specificity in the production of asymmetric lipids. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8:756. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Zutphen T., Todde V., et al. Kohlwein S.D. Lipid droplet autophagy in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2014;25:290–301. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-08-0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moeller C.H., Thomson W.W. Uptake of lipid bodies by the yeast vacuole involving areas of the tonoplast depleted of intramembranous particles. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1979;68:38–45. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(79)90140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vevea J.D., Garcia E.J., et al. Pon L.A. Role for lipid droplet biogenesis and microlipophagy in adaptation to lipid imbalance in yeast. Dev. Cell. 2015;35:584–599. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia E.J., Vevea J.D., Pon L.A. Lipid droplet autophagy during energy mobilization, lipid homeostasis and protein quality control. Front. Biosci. 2018;23:1552–1563. doi: 10.2741/4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang C.W., Miao Y.H., Chang Y.S. A sterol-enriched vacuolar microdomain mediates stationary phase lipophagy in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 2014;206:357–366. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201404115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seo A.Y., Lau P.W., et al. Lippincott-Schwartz J. AMPK and vacuole-associated Atg14p orchestrate μ-lipophagy for energy production and long-term survival under glucose starvation. Elife. 2017;6:e21690. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsuji T., Fujimoto M., et al. Fujimoto T. Niemann-Pick type C proteins promote microautophagy by expanding raft-like membrane domains in the yeast vacuole. Elife. 2017;6:e25960. doi: 10.7554/eLife.25960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamilton J.A., Small D.M. Solubilization and localization of triolein in phosphatidylcholine bilayers: a 13C NMR study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:6878–6882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spooner P.J., Small D.M. Effect of free cholesterol on incorporation of triolein in phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 1987;26:5820–5825. doi: 10.1021/bi00392a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zinser E., Daum G. Isolation and biochemical characterization of organelles from the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1995;11:493–536. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henry S.A., Kohlwein S.D., Carman G.M. Metabolism and regulation of glycerolipids in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;190:317–349. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benjamini Y., Krieger A.M., Yekutieli D. Adaptive linear step-up procedures that control the false discovery rate. Biometrika. 2006;93:491–507. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Veatch S.L., Keller S.L. Separation of liquid phases in giant vesicles of ternary mixtures of phospholipids and cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2003;85:3074–3083. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74726-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veatch S.L., Keller S.L. Miscibility phase diagrams of giant vesicles containing sphingomyelin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;94 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.148101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Veatch S.L., Gawrisch K., Keller S.L. Closed-loop miscibility gap and quantitative tie-lines in ternary membranes containing diphytanoyl PC. Biophys. J. 2006;90:4428–4436. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.080283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao J., Wu J., et al. Feigenson G.W. Phase studies of model biomembranes: complex behavior of DSPC/DOPC/cholesterol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:2764–2776. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ionova I.V., Livshits V.A., Marsh D. Phase diagram of ternary cholesterol/palmitoylsphingomyelin/palmitoyloleoyl-phosphatidylcholine mixtures: spin-label EPR study of lipid-raft formation. Biophys. J. 2012;102:1856–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bezlyepkina N., Gracià R.S., et al. Dimova R. Phase diagram and tie-line determination for the ternary mixture DOPC/eSM/Cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2013;104:1456–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blosser M.C., Starr J.B., et al. Keller S.L. Minimal effect of lipid charge on membrane miscibility phase behavior in three ternary systems. Biophys. J. 2013;104:2629–2638. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stevens M.M., Honerkamp-Smith A.R., Keller S.L. Solubility limits of cholesterol, lanosterol, ergosterol, stigmasterol, and β-sitosterol in electroformed lipid vesicles. Soft Matter. 2010;6:5882–5890. doi: 10.1039/c0sm00373e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mannock D.A., Lewis R.N.A.H., McElhaney R.N. A calorimetric and spectroscopic comparison of the effects of ergosterol and cholesterol on the thermotropic phase behavior and organization of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine bilayer membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hsueh Y.-W., Chen M.-T., et al. Thewalt J. Ergosterol in POPC membranes: physical properties and comparison with structurally similar sterols. Biophys. J. 2007;92:1606–1615. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Urbina J.A., Pekerar S., et al. Oldfield E. Molecular order and dynamics of phosphatidylcholine bilayer membranes in the presence of cholesterol, ergosterol and lanosterol: a comparative study using 2H-13C- and 31P-NMR spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1238:163–176. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00117-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hao M., Mukherjee S., Maxfield F.R. Cholesterol depletion induces large scale domain segregation in living cell membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13072–13077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231377398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levental I., Byfield F.J., et al. Janmey P.A. Cholesterol-dependent phase separation in cell-derived giant plasma-membrane vesicles. Biochem. J. 2009;424:163–167. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mahammad S., Dinic J., et al. Parmryd I. Limited cholesterol depletion causes aggregation of plasma membrane lipid rafts inducing T cell activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1801:625–634. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vrljic M., Nishimura S.Y., et al. McConnell H.M. Cholesterol depletion suppresses the translational diffusion of class II major histocompatibility complex proteins in the plasma membrane. Biophys. J. 2005;88:334–347. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.045989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Samsonov A.V., Mihalyov I., Cohen F.S. Characterization of cholesterol-sphingomyelin domains and their dynamics in bilayer membranes. Biophys. J. 2001;81:1486–1500. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75803-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baumgart T., Hammond A.T., et al. Webb W.W. Large-scale fluid/fluid phase separation of proteins and lipids in giant plasma membrane vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3165–3170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611357104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levental K.R., Lorent J.H., et al. Levental I. Polyunsaturated lipids regulate membrane domain stability by tuning membrane order. Biophys. J. 2016;110:1800–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burns M., Wisser K., et al. Veatch S.L. Miscibility transition temperature scales with growth temperature in a zebrafish cell line. Biophys. J. 2017;113:1212–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao J., Wu J., Veatch S.L. Adhesion stabilizes robust lipid heterogeneity in supercritical membranes at physiological temperature. Biophys. J. 2013;104:825–834. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stone M.B., Shelby S.A., et al. Veatch S.L. Protein sorting by lipid phase-like domains supports emergent signaling function in B lymphocyte plasma membranes. Elife. 2017;6:e19891. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Veatch S.L., Keller S.L. Organization in lipid membranes containing cholesterol. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;89 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.268101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Klose C., Ejsing C.S., et al. Simons K. Yeast lipids can phase-separate into micrometer-scale membrane domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:30224–30232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tulodziecka K., Diaz-Rohrer B.B., et al. Levental I. Remodeling of the postsynaptic plasma membrane during neural development. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2016;27:3480–3489. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-06-0420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dupuy A.D., Engelman D.M. Protein area occupancy at the center of the red blood cell membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2848–2852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712379105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jähnig F. Structural order of lipids and proteins in membranes: evaluation of fluorescence anisotropy data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:6361–6365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boumann H.A., Damen M.J.A., et al. de Kroon A.I.P.M. The two biosynthetic routes leading to phosphatidylcholine in yeast produce different sets of molecular species. Evidence for lipid remodeling. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3054–3059. doi: 10.1021/bi026801r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Patton-Vogt J., de Kroon A.I.P.M. Phospholipid turnover and acyl chain remodeling in the yeast ER. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2020;1865 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]