Abstract

Light-Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy (LSFM) is a rapidly growing technique that has gained tremendous popularity in the life sciences owing to its high-spatiotemporal resolution and gentle, non-phototoxic illumination. In this protocol, we provide detailed directions for the assembly and operation of a versatile LSFM variant, referred to as Axially Swept Light-Sheet Microscopy (ASLM), that delivers an unparalleled combination of field of view, optical resolution, and optical sectioning. To democratize ASLM, we provide an overview of its working principle, applications to biological imaging, as well as pragmatic tips for the assembly, alignment, and control of its optical systems. Furthermore, we provide detailed part lists and schematics for several variants of ASLM, that together, can resolve molecular detail in chemically expanded samples, subcellular organization in living cells, or the anatomical composition of chemically cleared intact organisms. We also provide software for instrument control and discuss how users can tune imaging parameters to accommodate diverse sample types. Thus, this protocol will serve not only as a guide for both introductory and advanced users adopting ASLM, but as a useful resource for any individual interested in deploying custom imaging technology. We expect that the time to build an ASLM will take about 1–2 months, depending on the experience of the instrument builder and the version of the instrument.

EDITORIAL SUMMARY

This protocol describes the working principle and implementations of Axially Swept Light-Sheet Microscopy, which can image subcellular features at organ scales in 3D. It discusses how to optimize its design, and provides a detailed guide for its construction and alignment.

Introduction

Light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) delivers an axial resolution and optical sectioning that is comparable to or better than confocal microscopes, all the while reducing photobleaching, phototoxicity, and accelerating the volumetric image acquisition rate1. To achieve this, LSFM adopts an orthogonal illumination and detection train, an idea that can be traced back to 1902 when Siedentopf and Zsigmondy introduced the ultramicroscope.2 Nonetheless, this technique remained dormant for nearly a century before being resurrected by Voie and Spelman, and later, Huisken and Stelzer, all of whom captured the scientific community’s attention when they demonstrated stunning fluorescence imaging of large specimens with vastly improved optical sectioning (i.e. the rejection of fluorescence from outside the focal plane of interest) and resolution3, 4. Ever since, rapid developments in LSFM have led to a massive proliferation of technologies and an entirely new field of optical imaging1.

The optical principle of LSFM is simple: by illuminating the sample from the side with a sheet of light, out of focus illumination is eliminated, which improves optical sectioning and reduces photobleaching and phototoxicity. Further, all excited fluorophores in the illuminated sheet of light are detected simultaneously with high quantum-yield efficient scientific cameras. Therefore, the overall laser power can be reduced without compromising the imaging speed or the signal to noise ratio, leading to reduced phototoxicity and photobleaching5. To illustrate, a common voxel dwell time for a laser scanning confocal microscope is ~1 microsecond, and thus it takes ~4.16 seconds to capture a 2048×2048×1 voxel image. In contrast, a LSFM can image an identical region in ~5 ms, 832-fold faster, yet with a per-voxel dwell time that is 5000-fold longer. Thus, LSFM not only eliminates the unnecessary illumination of out-of-focus regions of the sample but permits the massive reduction in the illumination intensities without compromising imaging speed or the signal to noise ratio.

The resolution of a LSFM is theoretically described by its cumulative point spread function (PSF), which is the product of its illumination intensity distribution and detection PSF6. Consequently, the thinner the light-sheet and the higher the numerical aperture (NA) of the detection objective, the better the axial resolution of the LSFM. However, an illumination beam is only useful throughout its waist region where it approximates a sheet of light. For a Gaussian beam, this amounts to ~2 Rayleigh lengths (which is also known as the confocal parameter), and the thickness of the light-sheet increases quadratically with beam length7. To circumvent this restriction, several solutions have been developed, including propagation invariant beams that in theory maintain a narrow beam waist over an arbitrarily long distance. These include Bessel beams8, Airy beams9, Lattice Light-Sheets10, and more recently, beams constructed using Field Synthesis11. However, for 1-photon illumination, each of these approaches is accompanied by sidelobes that increase with beam length, generate out-of-focus blur, and degrade image resolution and contrast. To minimize these side lobes, one can instead tile many short light-sheets and fuse the data12. Nonetheless, even the most widely adopted forms of these advanced light-sheets (e.g., the square Lattice Light-Sheet), show negligible improvements over Gaussian beams in terms of propagation length and light-sheet thickness13. An extended discussion on propagation invariant beams for light-sheet generation, and how they compare to the work presented herein, is provided further below.

Two approaches successfully decouple the trade-off between axial resolution and field of view: multiview deconvolution3, and axially swept light-sheet microscopy (ASLM)14, 15. In the former, the sample is imaged from multiple directions and the complementary views are computationally fused to generate a high-resolution, large field of view image16, 17. This is achieved either through sample rotation, or an optical system whereby each arm of the microscope can be sequentially used in an illumination or detection mode (e.g., diSPIM)18. For large and highly scattering tissues, a four objective mode can be implemented, where each objective has both illumination and detection optics (e.g., IsoView)19. Nonetheless, as multiple views are required for high-resolution imaging, this increases the magnitude of the data linearly, illuminates the sample repeatedly, decreases the throughput of the microscope, and requires computationally intensive multiview deconvolution. In contrast, ASLM uses aberration-free remote focusing20 to sweep a tightly focused Gaussian light-sheet through the sample in its propagation direction synchronously with the rolling shutter of a CMOS camera (Fig. 1a). Thereby only the well-focused beam waist of the light-sheet contributes to the final image, resulting in high axial resolution and optical sectioning. Such imaging performance can be maintained over large fields of view (only bounded by the remote focusing scan range and the size of the camera chip), overcoming the trade-off between axial resolution and field of view of traditional light-sheet microscopes (Fig. 1 b–c). Instead, ASLM trades-off spatial duty cycle, photon efficiency, and illumination confinement for axial resolution, optical sectioning, and field of view. As an additional advantage, the raw data does not require any computational post-processing (Box 1). The cleared tissue variant of ASLM delivers an axial resolution of 260 nm after deconvolution throughout a field of view of 310 μm, which is among the highest axial resolution achieved with light-sheet microscopy14 without applying any super-resolution mechanism (i.e. SIM/PALM/STORM/STED). Importantly, Lattice Light-Sheet Microscopy can only achieve a similar axial resolution for a much smaller field of view10, 11, 13. Consequently, ASLM has successfully imaged diverse specimens across vast spatial scales, including intact animals21, whole tissues14, living cells15, and even the ultrastructural organization of chemically expanded samples (Fig. 2a–d). Here, we aim to democratize ASLM by providing an in-depth yet broadly accessible description of aberration-free remote focusing, optical schematics, part lists, step-by-step protocols for aligning diverse optical elements, as well as directions for installing and using our freely available microscope control software. Thus, we not only describe how to build a light-sheet microscope, but also provide the foundation necessary for future scientists to further improve high-resolution imaging.

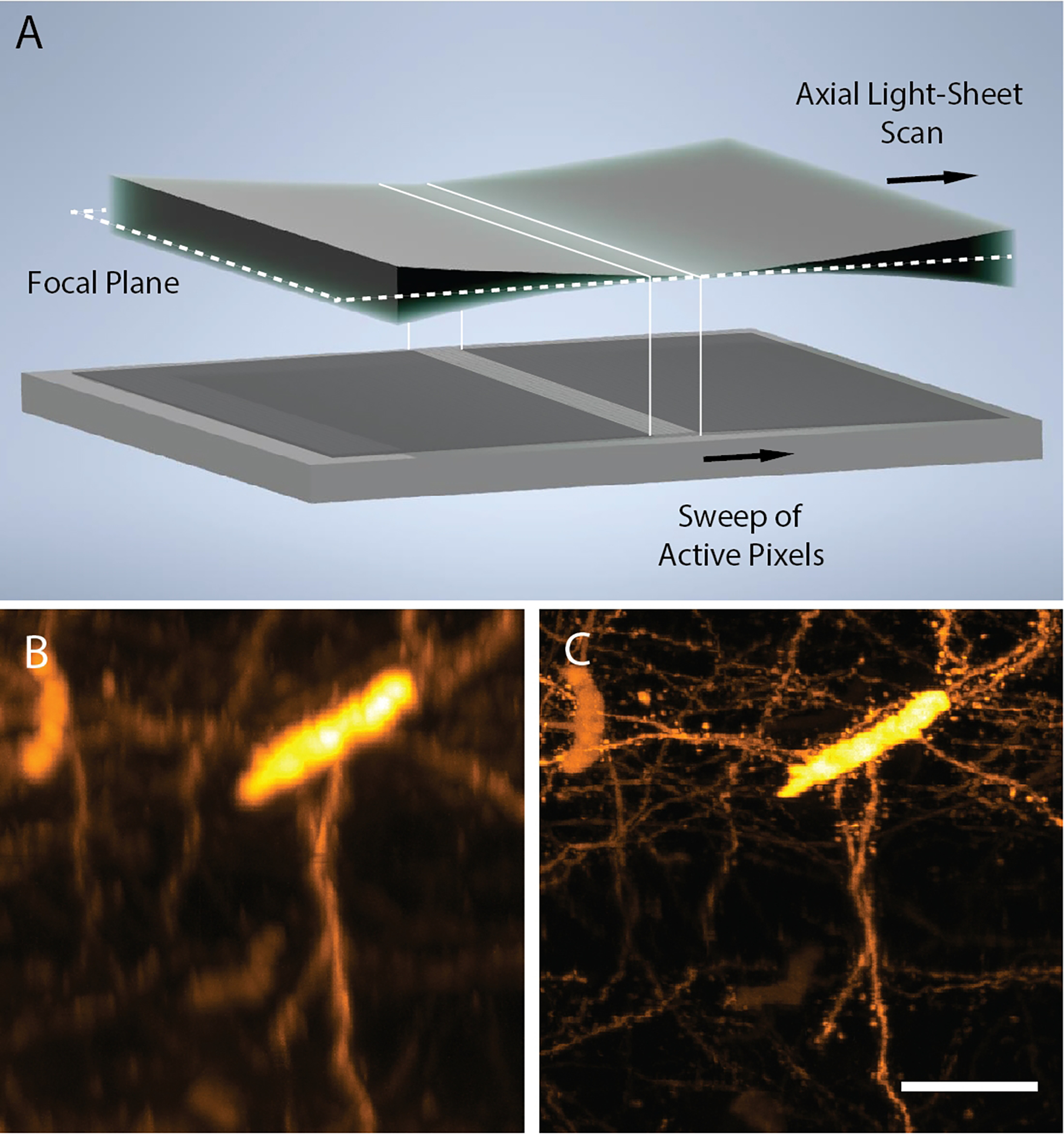

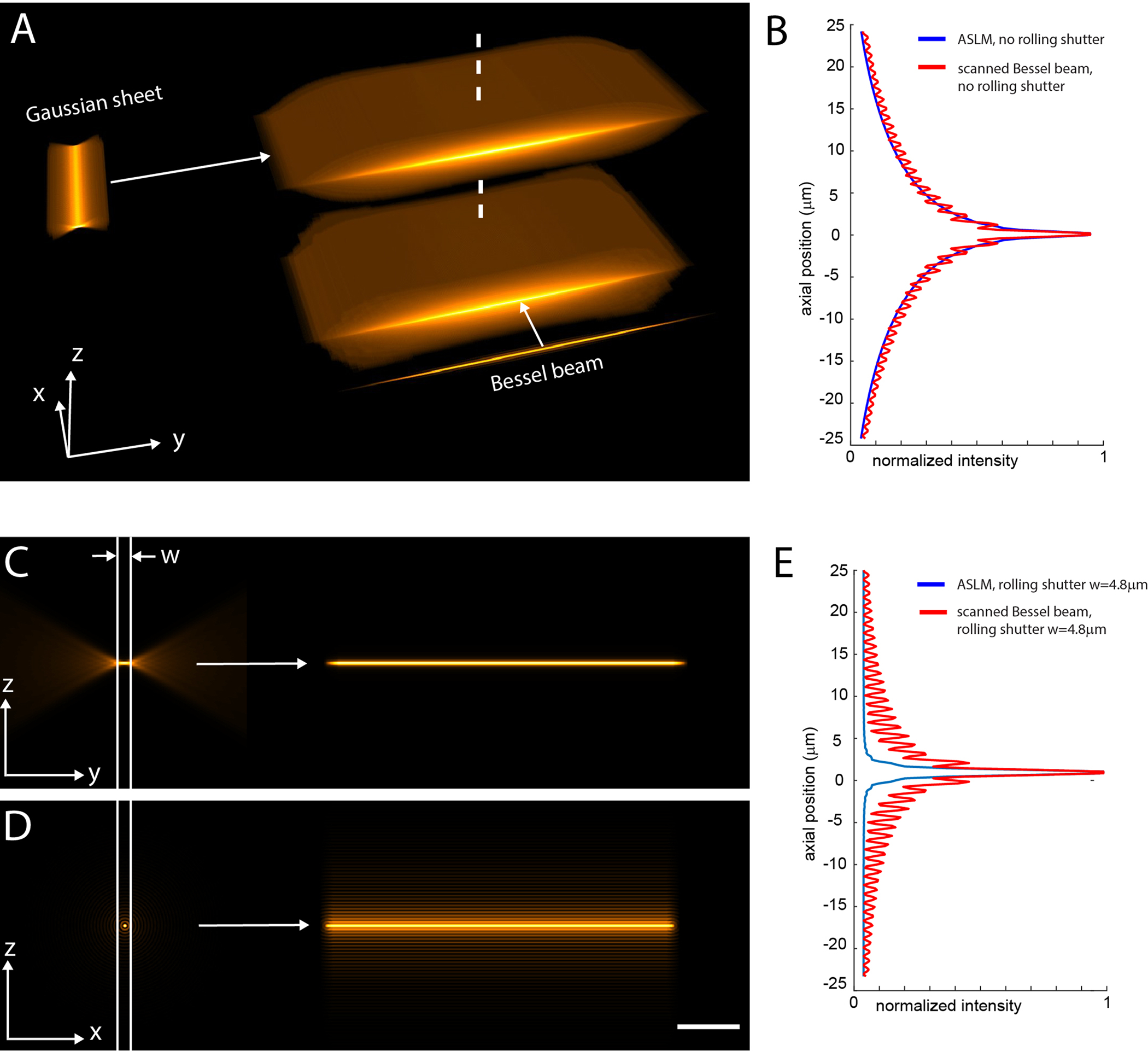

Figure 1 – Axially Swept Light-Sheet Microscopy.

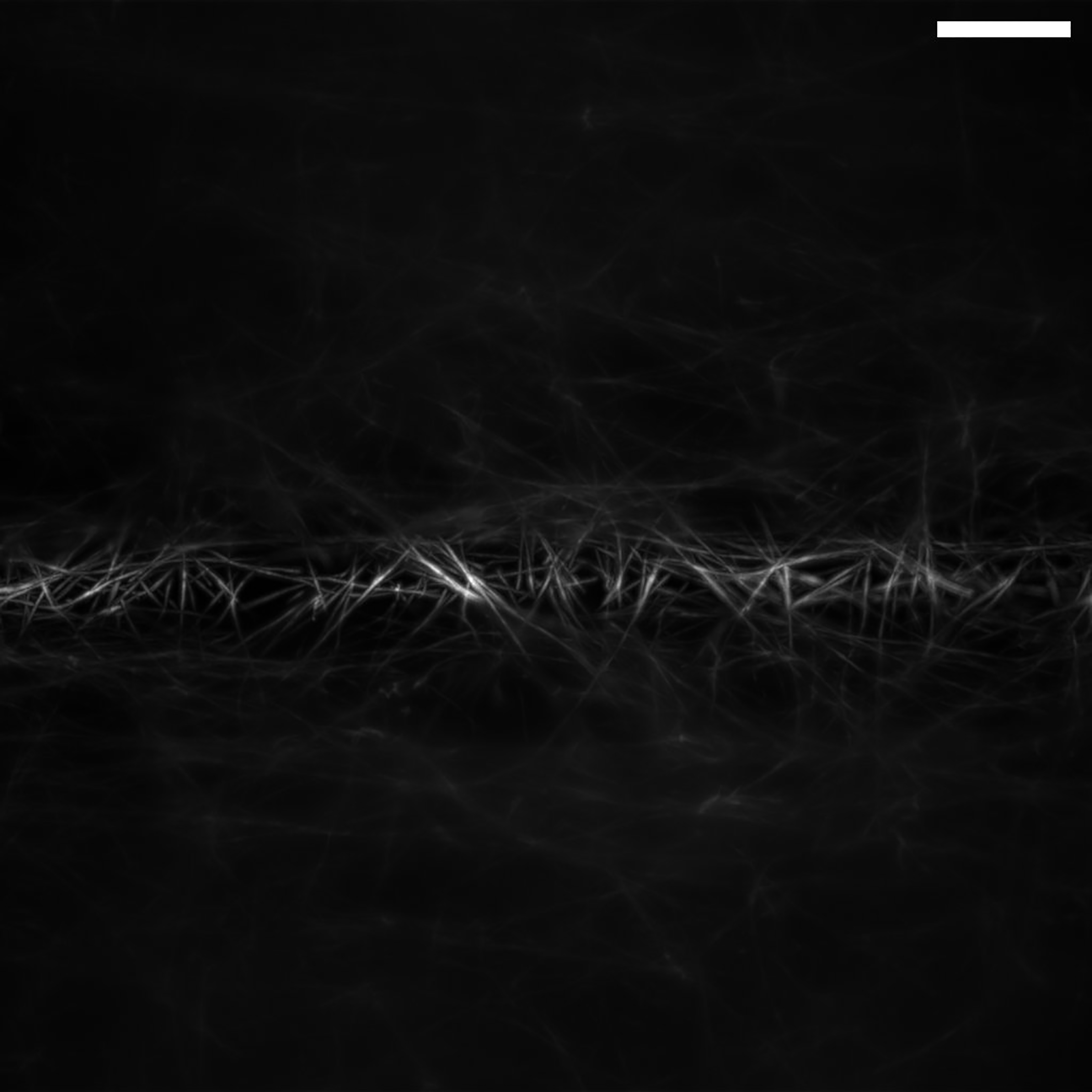

a, Principle of ASLM: a diffraction-limited 1-dimensional laser focus, created with a cylindrical lens, is scanned in its axial (e.g., propagation) direction synchronously with the rolling shutter (e.g., active pixels) of a scientific camera. Cross-sectional (X-Z) projections of CLARITY-cleared cortical39 Thy1-eYFP neurons as imaged by traditional light-sheet fluorescence microscopy b and ASLM c. Both images are shown as raw data, and in both cases, the full field of view spans 330×330 microns. Scale Bar: 50 microns

Box 1 -. Trade-offs in LSFM.

Field of View – The useful imaging area, which in LSFM is approximated by 2 Rayleigh lengths, or 1 confocal parameter in one dimension. The other dimension is given by the lateral extent of the light-sheet.

Lateral Resolution – The XY resolution of the detection path, which is dictated by the emission wavelength and numerical aperture of the detection objective.

Axial Resolution – The Z resolution of the detection path, which depends upon the thickness of the illumination light-sheet, the emission wavelength, and the numerical aperture of the detection objective.

Spatial Duty Cycle – The percent of time that each pixel on a camera is actively collecting photons during an exposure.

Speed – The overall rate at which one can capture images.

Post-Processing – Computational processing that is necessary to visualize the data, including shearing and multiview deconvolution.

Optical Sectioning – The ability to reject fluorescence that arises from outside the focal plane of interest. Such fluorescence manifests itself as out-of-focus blur.

Illumination Confinement – The percent of illumination light that resides within the detection objectives depth of focus.

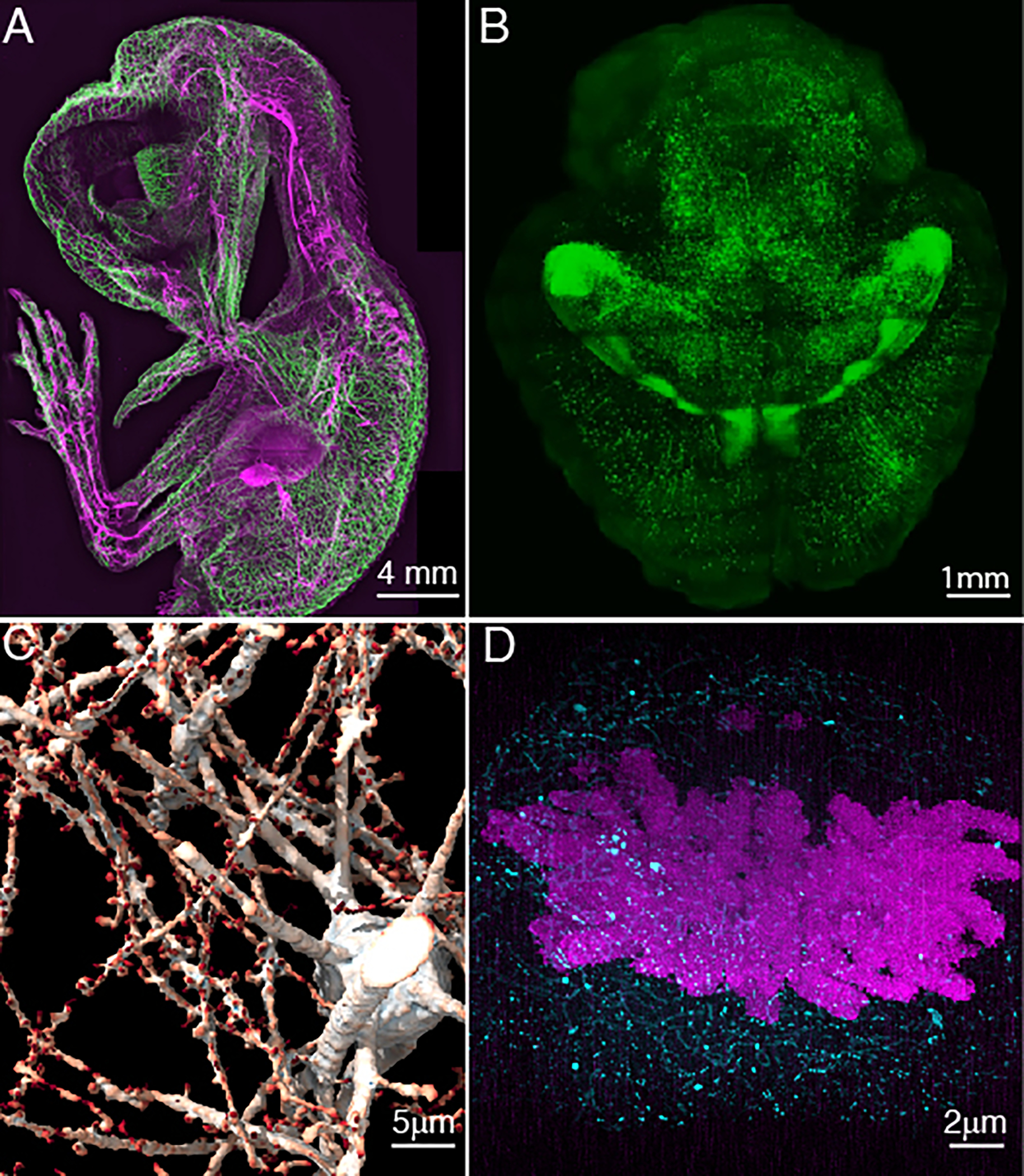

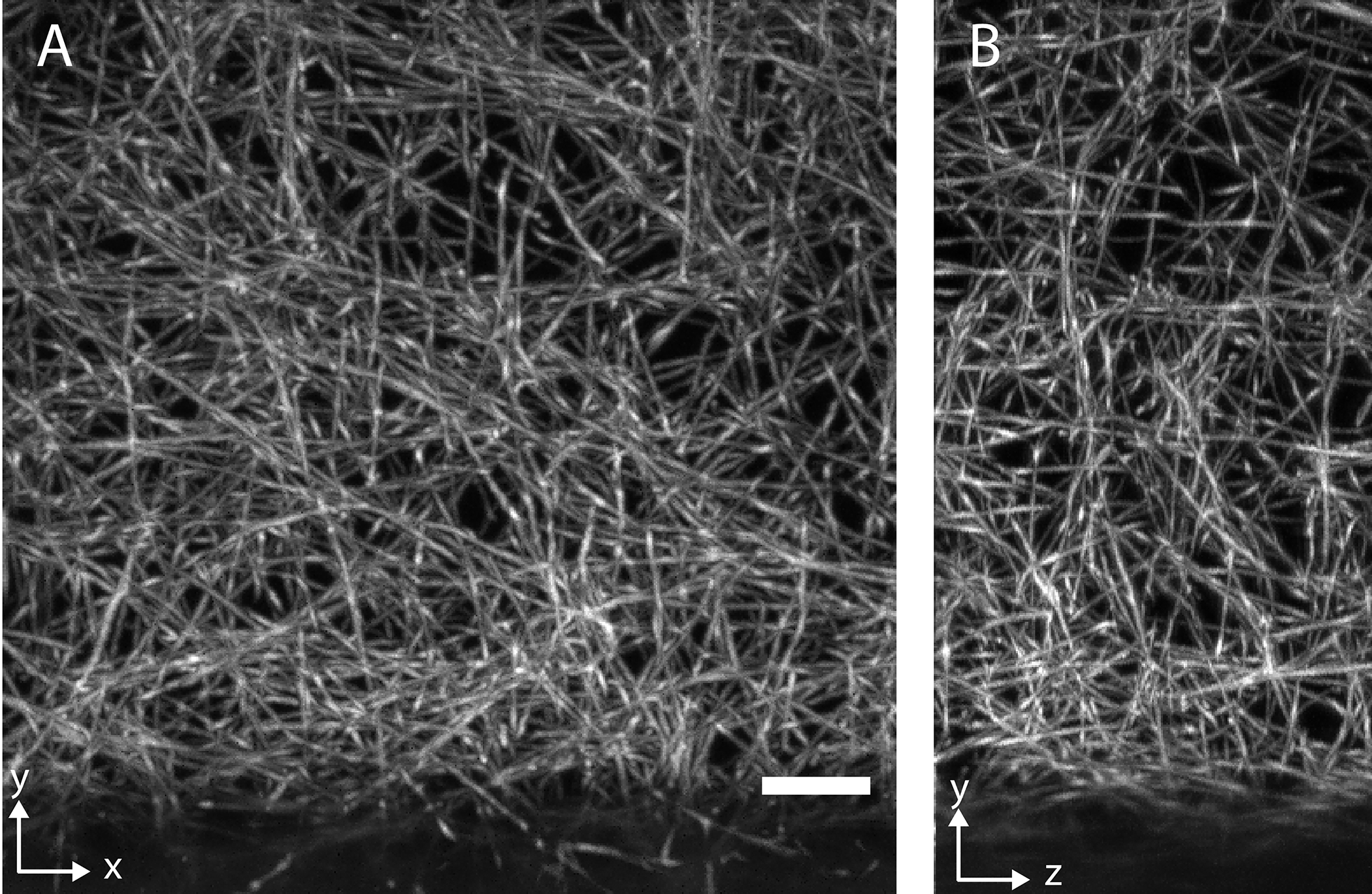

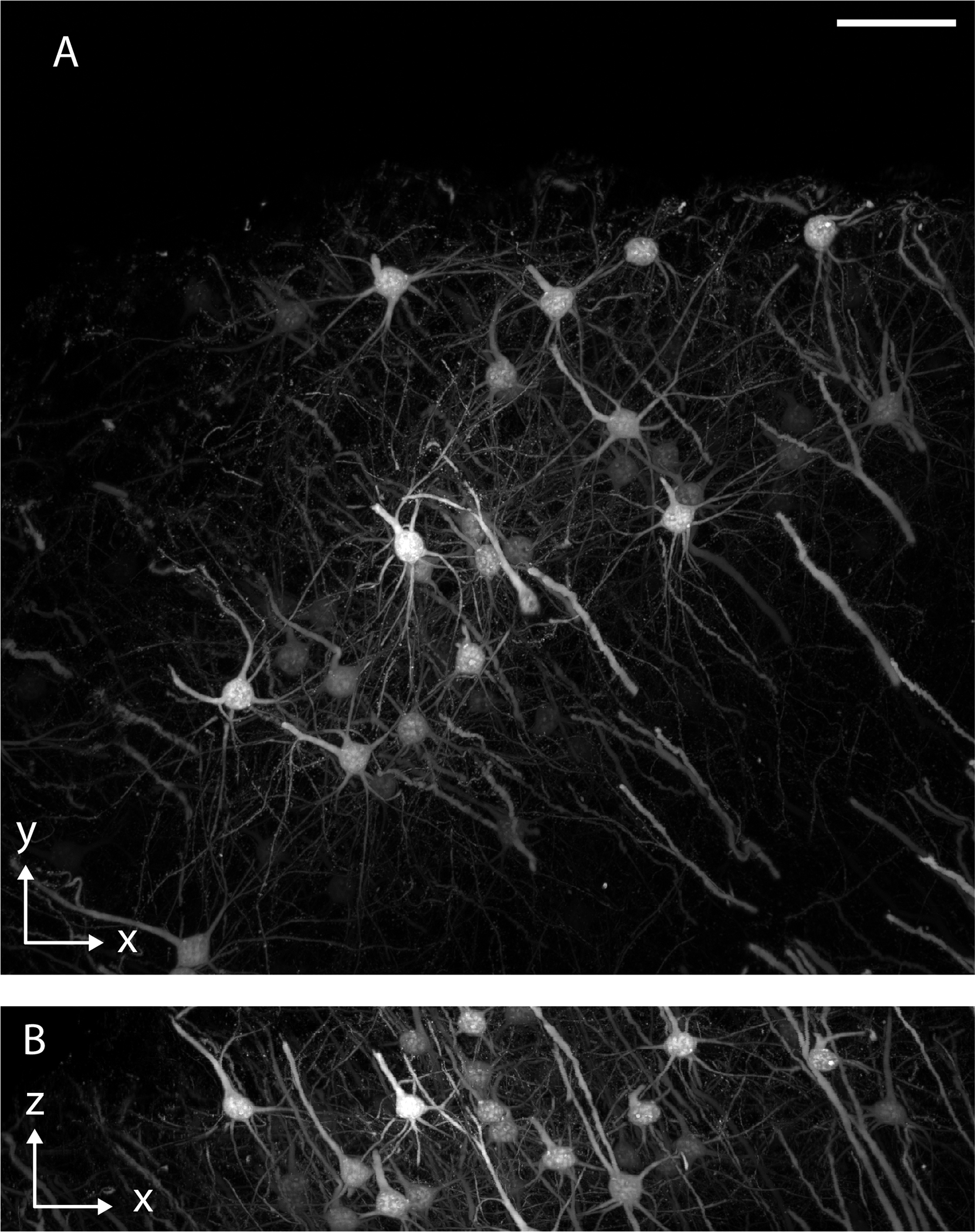

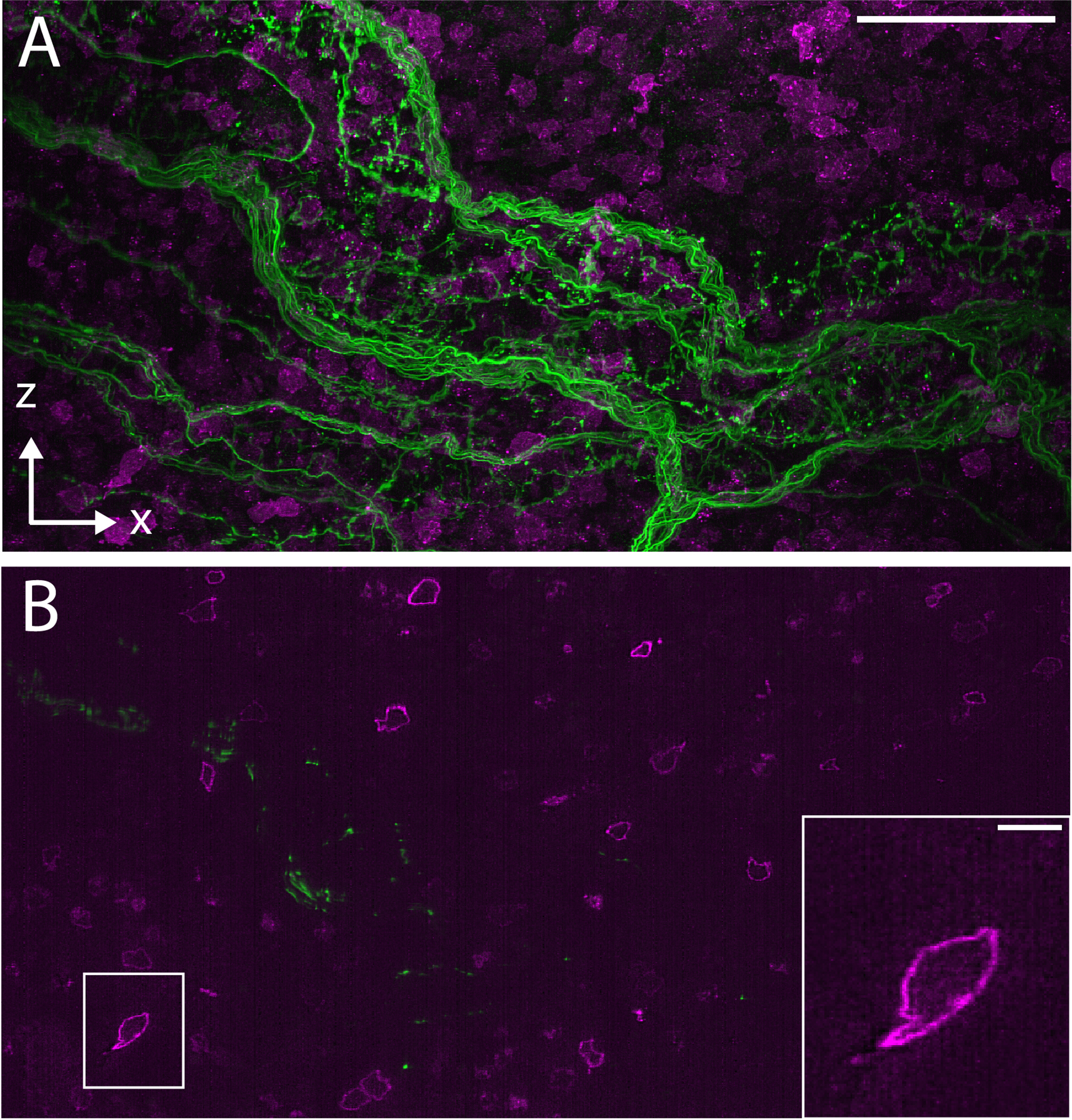

Figure 2 – Multiscale Imaging with Axially Swept Light-Sheet Microscopy.

a, Whole animal imaging of neurofilaments in a chicken embryo with ~5 μm resolution. b, Whole tissue imaging of a mouse brain with ~700 nm resolution. c, Synaptic-level imaging in a CLARITY cleared mouse brain. d, Chromosomes imaged with ~20 nm isotropic resolution in a Pan-ExM51 expanded mitotic HeLa cell.

Expertise and Background Necessary

This protocol aims to be as broadly accessible as possible. Although advantageous, only a basic understanding of optics is necessary. Consequently, we also direct readers to external sources of information to augment their understanding of microscope design and use22. Should one want to customize the microscope, a more advanced knowledge of optics and electrical engineering may be necessary, but we encourage readers to proceed fearlessly.

Axially Swept Light-Sheet Microscopy with Aberration-Free Remote Focusing

The key feature of ASLM is the synchronous scan of a light-sheet in its propagation direction with the rolling shutter of a CMOS camera (Fig. 1a). This ensures that a short and thin light-sheet governs the axial resolution over a large field of view, and stands in contrast to one of the earliest light-sheet microscopes, the orthogonal-plane fluorescence optical sectioning microscope23, 24, where the sample had to be mechanically moved through a stationary thin light-sheet to achieve a high axial resolution24. Consequently, ASLM provides huge improvements in acquisition speed and drastically reduces the amount of computational post-processing (e.g., stitching, image fusion, deconvolution) necessary.

Several mechanisms exist for scanning a beam in its propagation direction. These include electrotuneable lenses25, deformable mirrors26, and aberration-free remote focusing27, 28. However, for light-sheets with an NA greater than 0.3, only aberration-free remote focusing allows one to maintain a diffraction-limited laser focus throughout a large scan trajectory14. In contrast, because light-sheets with an NA below 0.3 are disproportionally less sensitive to spherical aberrations, scanning the illumination light-sheet in its propagation direction can be achieved with an electrotuneable lens without a noticeable decrease in optical performance29, 30.

The theory of aberration-free remote focusing has been described in detail elsewhere27, 28, but an intuitive explanation is given here. In principle, a conventional widefield microscope can form a 3D image, albeit one that is distorted along its optical axis (Fig. 3a). In such an optical system, the axial magnification scales with , where is the lateral magnification of the widefield microscope system and the refractive index of the immersion media7. Thus, the image of the specimen in image space is vastly stretched in its axial direction. Furthermore, the image of the specimen can only be free of aberrations in a plane that is optically conjugate to the nominal focal plane of the microscope objective. Outside of the nominal focal plane, spherical aberrations (and possibly higher order aberrations) significantly lower the resolution of the 3D image. However, it was mathematically shown that if one takes this distorted 3D image and propagates it through a secondary microscope system “in reverse”, a distortion free, diffraction limited 3D replica of the sample will appear in the front focal plane of the secondary microscope (Fig. 3b)20. The symmetry is maintained if the secondary microscope has the same lenses (and the same immersion media).

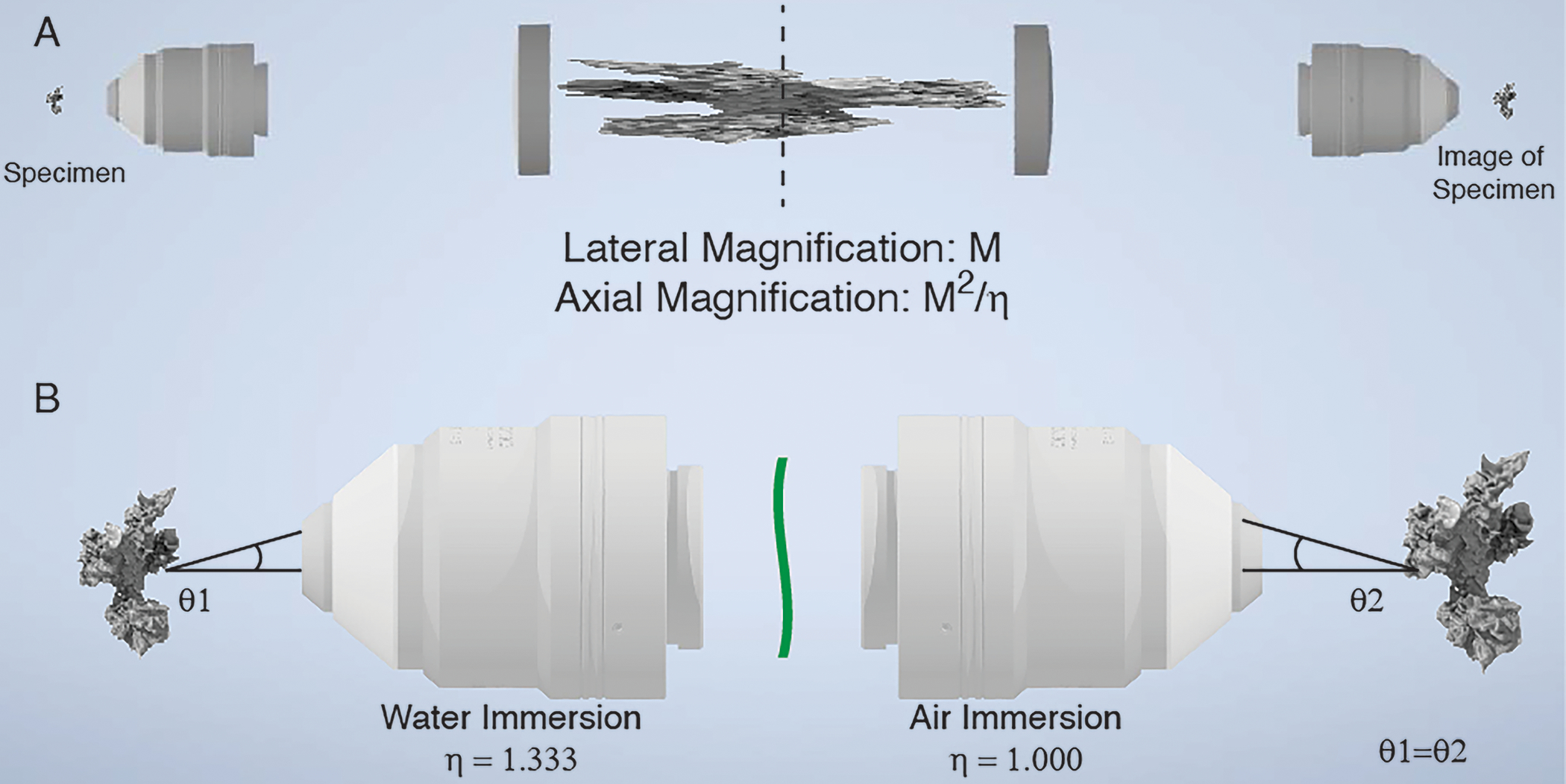

Figure 3 – Principles of aberration-free remote focusing.

a, 3D image formation in a widefield microscope. A cell is imaged with a water immersion objective and a tube lens. In the image space after the first tube lens, a 3D image of the cell is formed that is sharp at the nominal focal plane (dotted line) and stretched along the optical axis before and after the nominal focal plane. The intermediate 3D image (center) formed by the primary microscope (left) is propagated in reverse through a secondary microscope system (tube lens and secondary objective). If the overall magnification of the primary and secondary microscopes is chosen correctly, then the 3D image formed in the front focal plane of the secondary objective will be aberration-free and have the same axial and lateral magnifications. b, Zoomed-in view of the primary and secondary objectives, the cell (left) and its 3D image (right). The black line marks one imaging ray emanating from the sample. To ensure aberration-free image formation, the secondary objective needs to map this ray to the same angle. If the primary objective is designed for water immersion and the secondary objective for air immersion, then an aberration and distortion free 3D image is formed on the right if the overall lateral and axial magnification equals to 1.333.

But what happens if one combines a water immersion primary objective with an air immersion secondary objective? Does the aberration-free 3D image formation still hold? At a minimum, we would require that the image is not unduly stretched in the axial direction, i.e., that the lateral and axial magnification of the overall imaging system are the same. This can be satisfied if the lateral magnification of the entire imaging system is equal to the quotient of the refractive indices of the primary and secondary objective immersion mediums. Here, because we are combining an air immersion remote focusing objective () with a water immersion illumination objective (), the lateral magnification from the remote to the sample plane must be approximately equal to 0.750 to achieve an aberration-free image (See “Choosing ASLM parameters” for details).

Adjusting the lateral magnification to the ratio of the refractive indices guarantees the same magnification both laterally and axially. While not shown here explicitly, aberration-free 3D imaging is achieved if all rays propagating under a specific angle in the sample space of the first objective are mapped to the same angles at the focus of the second objective (black lines in Fig. 3b). Such rays share a common spot in the pupil plane of an objective. Thus, put differently, the task is to map points on the pupil plane of the primary objective to the equivalent points on the pupil plane of the secondary objective such that both generate rays with the same optical angles. This requirement is automatically fulfilled if we choose the overall magnification correctly and use objectives that fulfill the sine condition (i.e., are infinity corrected). The surprising principle of aberration-free 3D imaging also works in reverse, i.e., injecting a laser beam into the front focal space of the secondary objective and mapping it into the sample space of the primary objective. As such, this can be used to refocus a laser spot in the axial direction of the primary objective, which has found numerous applications in raster scanning microscopy28, 31, 32, and is used to scan the light-sheet in ASLM.

To achieve aberration-free imaging in practice, ASLM’s remote focusing scan unit consists of a half-waveplate, a polarizing beam splitter, a quarter waveplate, a microscope objective, a mirror, and a high-speed actuator (e.g., a voice coil14 or piezo actuator15). Light enters the scan unit through the polarizing beam splitter and quarter wave plate and is focused by the objective onto the actuator-mounted mirror (Fig. 4). The light is then back-reflected, transmitted through the quarter wave plate and polarizing beam splitter a second time, and relayed to the illumination objective with a telescope. By properly designing and aligning such a system, scanning the mirror position in the remote focusing unit generates back-reflected light encoding the exact wavefront necessary to scan a diffraction limited laser focus in the illumination objective. Any aberrations introduced by moving the mirror beyond the nominal focal plane of the remote focusing objective are reversed by the illumination objective, which requires an equal and opposite aberration to create a diffraction-limited focus outside its nominal focal plane.

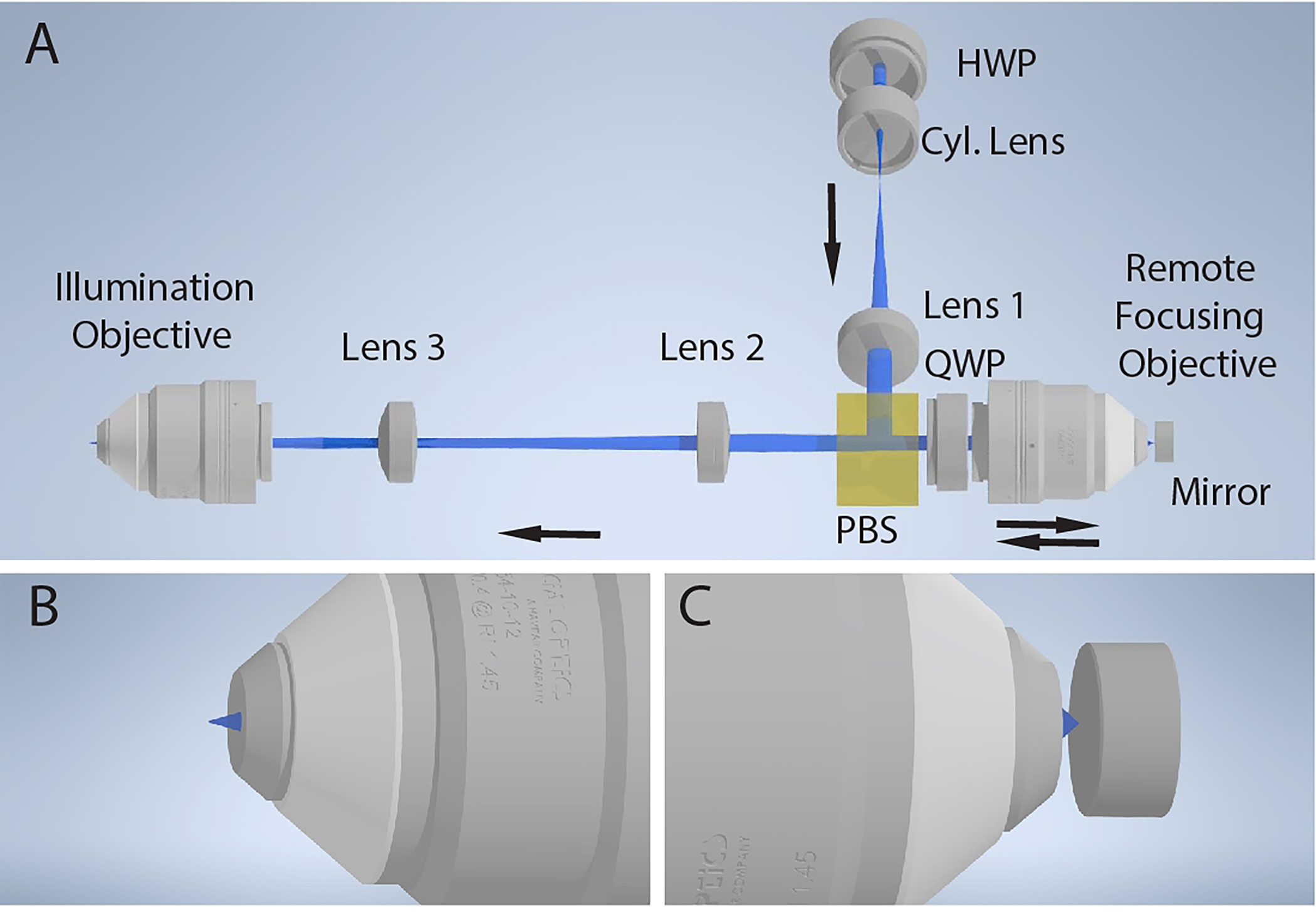

Figure 4. Optical principle for axially sweeping of a light-sheet.

a, Basic schematic of the remote focusing system for axial scanning of the light-sheet. A 1-dimensional light-sheet is created with a cylindrical lens (Cyl. Lens), recollimated with an achromatic doublet (Lens 1), reflected with a polarizing beam splitter (PBS), and focused onto a mirror with a remote focusing objective. The light is back reflected, passed through the polarizing beam splitter, relayed with a pair of achromatic doublets (Lenses 2 and 3), and focused into the specimen with an illumination objective. The half-wave plate (HWP) is rotated to maximize reflection of the light off the polarizing beam splitter, and the rotation of the quarter-wave plate (QWP) is rotated to maximize transmission through the polarizing beam splitter on the reverse path. b, Diffraction-limited light-sheet at the focus of the illumination objective. c, Laser focused onto the mirror by the remote focusing objective. An axial translation of the mirror results in an axial shift in the position of the diffraction-limited light-sheet at the focus of the illumination objective.

Comparison of ASLM to other light-sheet modalities

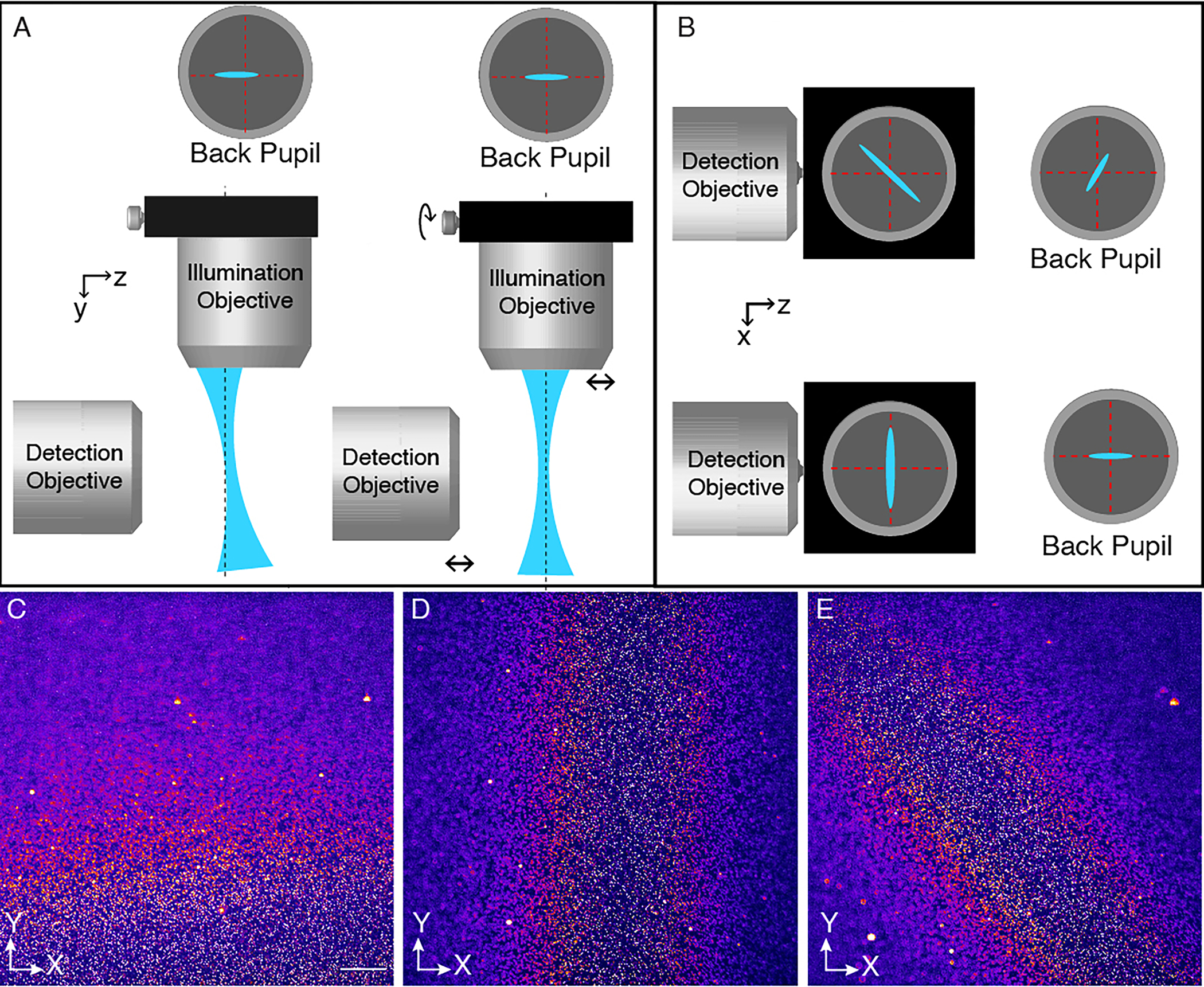

To understand the relative strengths and weaknesses of ASLM compared to other high-resolution light-sheet techniques that employ propagation invariant beams, we have performed numerical simulations based on vectorial theory. Here we have simulated the overall intensity distribution with which the sample is illuminated by ASLM, Bessel beam and hexagonal lattice light-sheets. The more commonly used square lattice was not compared here, as it cannot be engineered to cover large fields of view at a constant thickness. Instead, the square lattice behaves more like a Gaussian light-sheet that increases in thickness for larger propagation lengths13, 33. Based on the data available, it appears that recreating the coverage of a particular square lattice light-sheet with ASLM would require little to no axial scanning.

Fig. 5a, top-left, shows a simulated Gaussian light-sheet of NA 0.5. On the right, the total three-dimensional intensity distribution is depicted as the light-sheet is axially swept by one hundred microns in its propagation direction. While the rolling shutter for detection is synchronized to the beam waist and thereby does not “see” the additional out-of-focus blur, the sample is nonetheless excited by the sum of all intensity components of the scanned light-sheet. For comparison, we also performed numerical simulations for a scanned Bessel beam light-sheet which covers the same field of view and features the same main lobe thickness as the Gaussian light-sheet. The static and scanned Bessel beams are shown on the bottom-right of Fig. 5a.

Figure 5. Numerical simulations for light-sheets derived via ASLM and a scanned Bessel beam.

a, A Gaussian light-sheet (NA 0.5) and a Bessel beam, both adjusted to have the same thickness, are scanned in the X and Y directions, respectively, to generate light-sheets with identical field of views. In the Y-direction, both light sheets are 100 microns long (Full-Width Half Maximum). b, Cross sectional profile along the dotted line in a through the ASLM and the scanned Bessel beam light-sheet. These profiles and the renderings in a represent the overall volumetric excitation load for both techniques. c, Portion of the light-sheet that is used for imaging in ASLM when using a rolling shutter with a width “w” that encompasses the beam waist of the light-sheet. d, Portion of the light-sheet that is used for imaging with the scanned Bessel beam when using a rolling shutter of the same width as in c. e, Cross-sectional profiles of the light-sheets used for imaging in c-d. These profiles and the light-sheets shown in c-d illustrate the optical sectioning capability of the two light-sheet techniques for a given width of the rolling shutter. The Z direction is along the optical axis of the detection objective. The Y-direction is along the optical axis of the illumination objective. Scale Bar: 20 microns. The width w of the rolling shutter was set to 24 pixels in this simulation, which corresponds to 4.8 microns.

If we compare axial profiles (dotted vertical line in Fig. 5a) through these simulated intensity distributions, we see that the effective excitation load imparted by ASLM is virtually identical to the scanned Bessel beam light-sheet (Fig. 5b). Therefore, the excitation of out-of-focus fluorescence and the amount of photobleaching will be similar within a linear excitation regime. However, in the example shown in Fig. 5a, the Gaussian light-sheet is ~six times longer than it is thick, a ratio that increases when reducing the excitation NA. In contrast, the Bessel beam main lobe is round and not elongated like the Gaussian sheet, resulting in a six-fold lower spatial duty cycle (the time pixels are effectively illuminated by the main lobe during a scan). In general, ASLM has a four to sixty-fold (for excitation NAs from 0.8 to 0.15 respectively) better duty cycle than light-sheets generated by scanning a Bessel beam.

We note that such a high-aspect ratio Bessel beam light-sheet as shown in Fig. 5a would be impractical due to the large amount of out-of-focus fluorescence that is generated, which would flood the in-focus signal on the camera. In contrast, ASLM rejects out-of-focus light robustly, due to the geometrical location of the out-of-focus blur ahead and behind the main waist of the Gaussian beam. This is illustrated in Fig. 5c–e, where a rolling shutter with a width that encompasses the Gaussian beam waist was applied (see also corresponding point spread function simulations in Supplementary Fig. 1–2). While the use of a rolling shutter suppresses out-of-focus blur in the final image, it also reduces the photon collection efficiency compared to a global camera shutter. In this numerical simulation, the peak intensity (e.g. the peak of the line profiles in Fig. 5b and 5e) is reduced by a factor of ~2.5 for ASLM and ~1.6 for the Bessel beam light-sheet with a rolling shutter. Of note, even with a rolling shutter of one pixel width (in this example 24-fold shorter than what is sufficient for ASLM), the sidelobes for the Bessel beam light-sheet cannot be fully suppressed. Importantly, Bessel beam light-sheets using two- and three-photon excitation can largely avoid out-of-focus light excitation34, 35, even for high aspect ratio sheets as shown in Fig. 5a36. Multiphoton excitation comes however with its own challenges, such as a limited choice of fluorophores for multicolor imaging, high laser power densities and expensive and complex laser sources.

Among the documented dithered optical lattices used in LLSM, the hexagonal lattice remains propagation invariant, and as such can in theory span large light-sheets while keeping a narrow main lobe. The hexagonal lattice in the seminal LLSM paper10 is 4.9 times longer than a corresponding Gaussian light-sheet with an identical main lobe thickness that would be used in ASLM (See also Supplementary Fig. 3). As a lattice has a 50% duty cycle laterally due to its interference pattern (compared to 100% lateral duty cycle using Gaussian sheets in ASLM), this leaves an estimated overall improvement in duty cycle of ~2.5 over ASLM. Thus, for faint signals, the hexagonal lattice, in this implementation, is estimated to yield ~2.5 times stronger signal for a given overall exposure time, at the expense of more out-of-focus blur. For sparse emitters, this trade-off might be worthwhile taking. In principle, this advantage in duty cycle would increase for hexagonal lattices with higher aspect ratios, i.e., sheets that are stretched in the propagation direction in which ASLM must scan its sheet. However, hexagonal lattices suffer from large out-of-focus excitation when they are pushed to aspect ratios that ASLM can routinely image (Supplementary Fig. 4)15, 36. As there is currently no mechanism to physically exclude the out-of-focus blur in LLSM, image data would be compromised by the shot noise of the blur in such a scenario. Consequently, LLSM uses either short hexagonal light-sheets for high-resolution imaging, and much more commonly, the much thicker square light-sheets with reduced sidelobe structures. We note that the combination of hexagonal lattices and structured illumination can improve the axial resolution and optical sectioning capability, at the expense of acquiring five images per reconstruction10. While not yet widely used, this mechanism has the potential to improve axial resolution and/or extend the field of view for LLSM.

Choosing ASLM Illumination Parameters

From the numerical simulations in the previous section, we can state that ASLM can provide light-sheet imaging with field of views and axial resolution that would otherwise not be possible with square lattices or not practical with hexagonal lattices or one-photon Bessel beam light-sheets. While ASLM allows one to perform such imaging, this comes with a price: the larger the field of view for a given axial resolution, the shorter the effective pixel dwell time, the smaller the detected signal and the larger the out-of-focus excitation becomes. As an example, for a light-sheet shown in Fig. 5a, scanning it across a hundred microns reduces the pixel dwell time by a factor of 20. In other words, for a camera exposure time of 100 milliseconds, the individual pixels only integrate signal for 5 milliseconds. Thus, for live cell imaging, we advise choosing the axial scan range to be as short as possible (so that the field of view encompasses the sample, but not much more). Furthermore, for very dim samples, it can be worthwhile reducing the excitation NA (which is typically done by placing an adjustable slit mask in front of the cylindrical lens, as shown in Fig. 6). Reducing the excitation NA will strongly increase the fluorescence signal, as the light-sheet becomes longer in a nonlinear fashion. The longer light-sheet will lead to longer effective pixel dwell times and its increased sheet thickness will lead to increased fluorescence signals, at the expense of axial resolution.

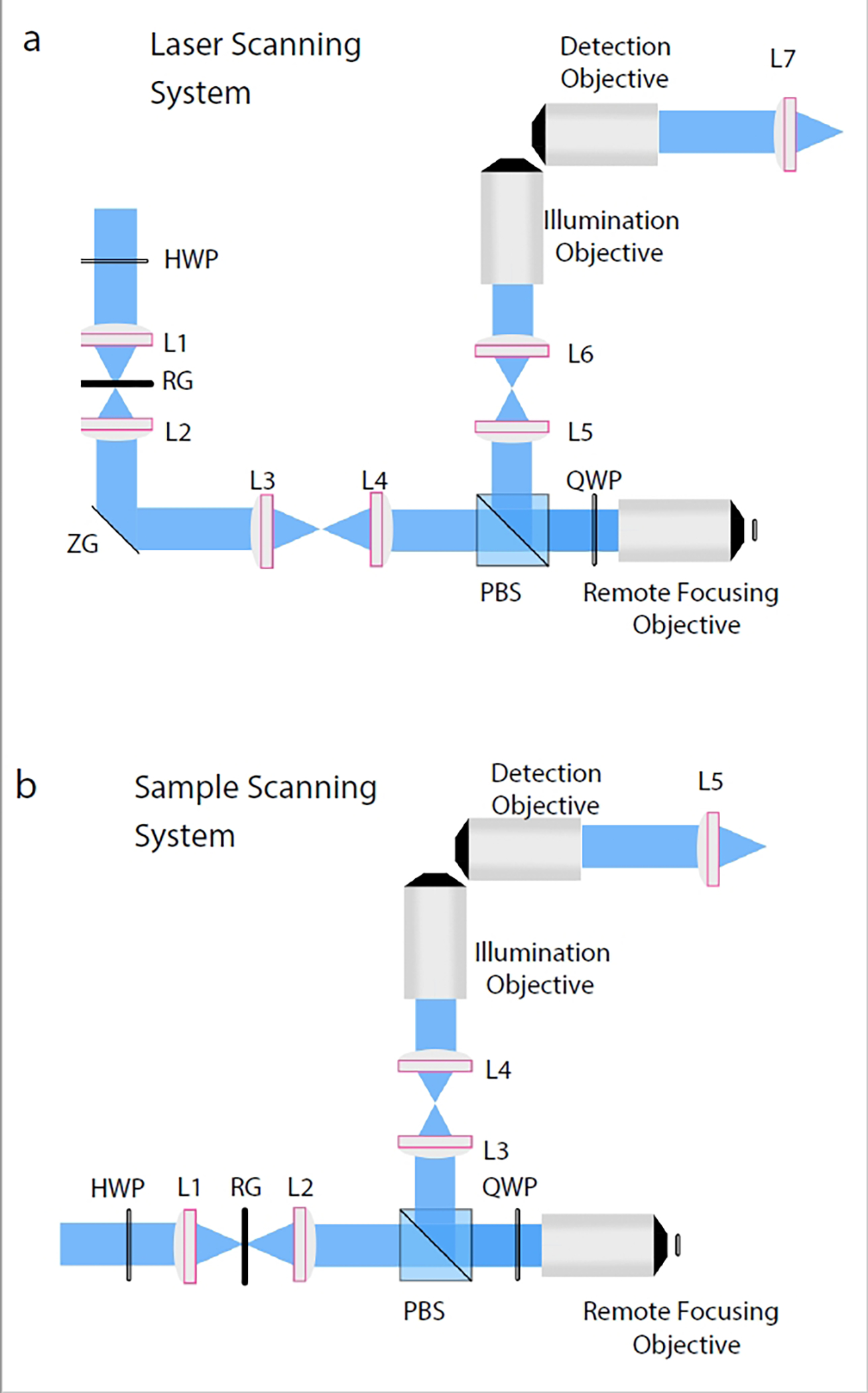

Figure 6. Detailed optical schematics of generic variants of axially swept light-sheet microscopy.

a, Laser scanning variant: Incoming light polarization is rotated with a half wave plate, focused into a 1D line with a cylindrical lens (L1), reflected off the resonant galvanometer (RG), recollimated with an achromatic doublet (L2), reflected off the Z-galvanometer (ZG), and relayed to the remote focusing objective with a scan lens (L3) and tube lens (L4). Polarization is rotated on each pass through the remote focusing objective with a quarter wave plate (QWP) and relayed towards the illumination objective with a polarizing beam splitter and a pair of achromatic doublets (L5 and L6). The detection objective collects the fluorescence from an orthogonal viewing perspective and focuses it onto a camera with a tube lens or achromatic doublet (L7). b, Sample scanning variant: The sample scanning variant does not require the Z-galvanometer, scan lens, or achromatic doublet. Instead, the light-sheet is formed with a cylindrical lens (L1), reflected off the resonant galvanometer (RG), recollimated with an achromatic doublet (L2), and sent directly into the remote focusing objective.

By judiciously choosing the axial scan range, we have imaged single cells expressing fluorescent proteins for >16 hours without notable photo-bleaching or toxicity over hundreds (at high excitation NA) to thousands (at reduced excitation NAs) of timepoints15. In the arena of cleared tissue imaging, ASLM can be pushed further in its field of view and axial resolution, as phototoxicity is no longer a concern. Nevertheless, when imaging field of views spanning the full camera chip, weak fluorescent signals can become limiting. In such scenarios, we typically apply exposure times in the range of 100–200 milliseconds. This allows us to reduce peak laser powers and acquire sufficient signal. Faster ASLM imaging has been reported31, 37, which is normally achieved with high laser powers, bright samples and/or short scan ranges that are similar to what is used in high-resolution applications of LLSM.

De Novo Design of an Aberration-Free Remote Focusing System

To design an aberration-free remote focusing system for a particular illumination objective, one must first calculate its opening half angle according to equation 1. Here, is the opening half angle of the objective, is the numerical aperture of the illumination objective, and is the refractive index of its immersion media.

| Eq.1 |

For the 0.4 multi-immersion objective used in the larger field of view variant of ctASLM14 the opening half angle is ~16 degrees for solvents with a refractive index between 1.333 and 1.56. Necessarily, the remote focusing objective needs an opening half angle that is equal to or larger than this value. In the case of an air objective (), an of 0.27 or greater is thus required, which is easily achieved using an objective with an of 0.28 (e.g., XLFLUOR4X/340).

After identifying a suitable primary and remote objective, the relay lenses must be selected such that the overall magnification from the remote space to the sample space is equal to the ratio of the refractive indices of the immersion media of the used objectives. For the aforementioned combination of objectives, this requires the magnification from sample space () to remote space () equal the ratio of the refractive indices, which here is simply the refractive index of the immersion media at the sample. To compute the overall magnification, it is easiest to first determine the focal length of each objective, which can be calculated by dividing the focal length of the tube lens by the objective’s magnification. The overall magnification is described by equation 2. Here, and are the focal lengths of the primary and the remote objective, respectively, and and are the focal lengths of the lenses adjacent to the remote and the primary objective, respectively (Fig. 4a, where the primary objective is the illumination objective of the ASLM system).

| Eq. 2 |

According to our example, our remote and primary objectives have a focal length of 45 and 12.35 mm, respectively, which was calculated by dividing the focal length of the tube lens, indicated by the objective manufacturer (f = 180 mm in case of the Olympus XLFLUOR4X/340 objective, and f = 200 mm in case of the multi-immersion objective), by the magnification of the objective. If we choose as 200 mm and as 75 mm, we obtain an overall magnification from the sample space to the image space of 1.37, which is close enough to 1.45 for practical purposes. Importantly, the multi-immersion objective lens slightly changes its focal length and numerical aperture with different immersion media. This is desirable, as the overall magnification must change with increasing or decreasing refractive index of the immersion media. Here, it is advisable to compute the overall magnification for different immersion media and choose the telescope accordingly. In our hands, the magnification of the telescope cannot be perfectly matched for all immersion media but is selected according to the refractive index of the predominant clearing method used (e.g., BABB38, CLARITY39, Expansion Microscopy40). For live cell variants of ASLM, the overall magnification can in principle be perfectly matched as the primary objective is only used with water immersion15.

In addition to calculating the magnification according to the objective focal lengths, we can also verify if angles are indeed mapped to the same angles between the remote and sample space using equation 3. Here, is the radius of the back pupil and is the focal length of the objective.

| Eq. 3 |

Accordingly, the highest angle rays (16 degrees) at the front pupil of the multi-immersion illumination objective will circularly exit the back pupil of the objective with a radius of 4.9 mm. Next, we must design the relay optics between the illumination objective and the remote focusing objective such that this opening half angle is maintained at the focus of the remote objective, which has a focal length of 45 mm. If we use the same opening half angle of 16 degrees, then we obtain a back-pupil radius of 12.6 mm at the remote objective using equation 3. Thus, for a proper relay, the 12.6 mm back pupil of the remote focusing objective must be de-magnified by a factor of 2.55-fold to create the desired opening half angle at the front focal plane of the illumination objective. In this system, we accomplish this with a telescope consisting of a 200 mm and 75 mm achromatic doublet, a de-magnification of 2.67. As we have seen with the overall magnification, the relay system does not perfectly fulfill the aberration-free remote focusing condition, but it is close.

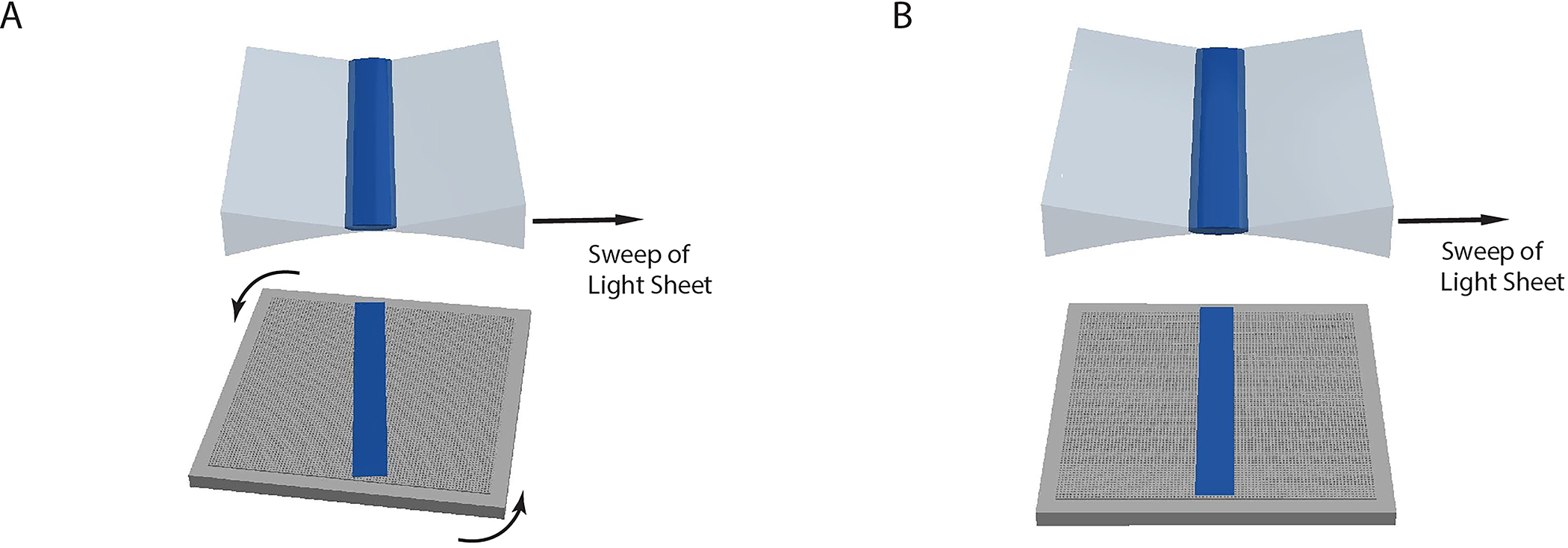

Variants of Axially Swept Light-Sheet Microscopy

Several variants of ASLM exist, each optimized for specific sample types, and operating at distinct spatial scales. For live-cell imaging, two variants of ASLM are designed to accommodate high NA water immersion objectives15, 31, 41, 42. In contrast, for imaging chemically cleared tissues, another two variants of ASLM (ctASLMv1 and ctASLMv2) are designed with multi-immersion objectives capable of imaging at the desired spatial scale and in the solvent of choice for tissue clearing14. A 5th system, mesoSPIM, which uses an electrotuneable lens (ETL) for remote focusing, is detailed elsewhere but included here for comparison43. Each of these 5 variants are compatible with Expansion Microscopy40. Table 1 lists the key optics for each of these systems, including the detection and illumination objectives, and the resulting theoretical lateral resolution, axial resolution, and field of view. Part lists for key components in each of these microscopes is provided in Supplementary Tables 1–5. While the methods described here can be used to build any variant of ASLM, we will focus on the large field of view cleared tissue imaging system, ctASLMv114. Fig. 4a provides an optical overview of aberration-free remote focusing and Fig. 6 provides a schematic layout for laser and sample-scanning variants of ASLM. The laser scanning variant is intended for fast volumetric imaging in live cell applications. In this variant, the acquisition of a 3D stack is performed by moving the detection objective with a piezo actuator and scanning the light-sheet with a galvanometer to each new focal plane. In contrast, in the sample scanning variant, the sample is moved with a piezo actuator through the fixed focal plane of the detection objective (to which the light-sheet is aligned). This variant is primarily used for cleared tissue imaging, as it provides a larger range for Z-stack acquisition (only limited by the range of the actuator and the working distance of the detection objective) than the laser scanning variant.

Table 1.

Different variants of ASLM.

| Sample Type | Detection Objective | Illumination Objective | Lateral and Axial Resolution (nm) | Field of View (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live cell imaging | Nikon NA 1.1 25x | Special Optics NA 0.69 | 300 and 450 | 160 × 160 |

| Live cell imaging | Nikon NA 0.8 40x | Nikon NA 0.8 40x | 380 and 390 | 300 × 300 |

| Cleared Tissue Imaging (ctASLMv2) | ASI NA 0.7 | ASI NA 0.7 | 450 and 380 | 300 × 300 |

| Cleared Tissue Imaging (ctASLMv1) | ASI NA 0.4 | ASI NA 0.4 | 830 and 940 | 870 × 870 |

| Cleared Tissue and Animal Imaging (mesoSPIM) | Olympus MVX10/ MVPLAPO 1x | Nikon AF-S Nikkor 50 mm f/1.4G | ~5,000 | 2,800 – 28,300 |

All resolution values are estimated from raw (e.g., without deconvolution) data of fluorescence nanospheres and reported as a Full-Width Half-Maxima according to each variant’s original and/or subsequent manuscripts14, 15, 29, 44.

Overview of the Protocol

The remainder of this protocol provides an in-depth guide for constructing a fully-functional ctASLM-v1 imaging system14. This includes installation of the microscope software, general optical alignment tips and tricks, the construction of the illumination path, detection path, optimization of remote focusing operation, sample chamber and mount, and fine-tuning of instrument alignment.

Microscope Overview

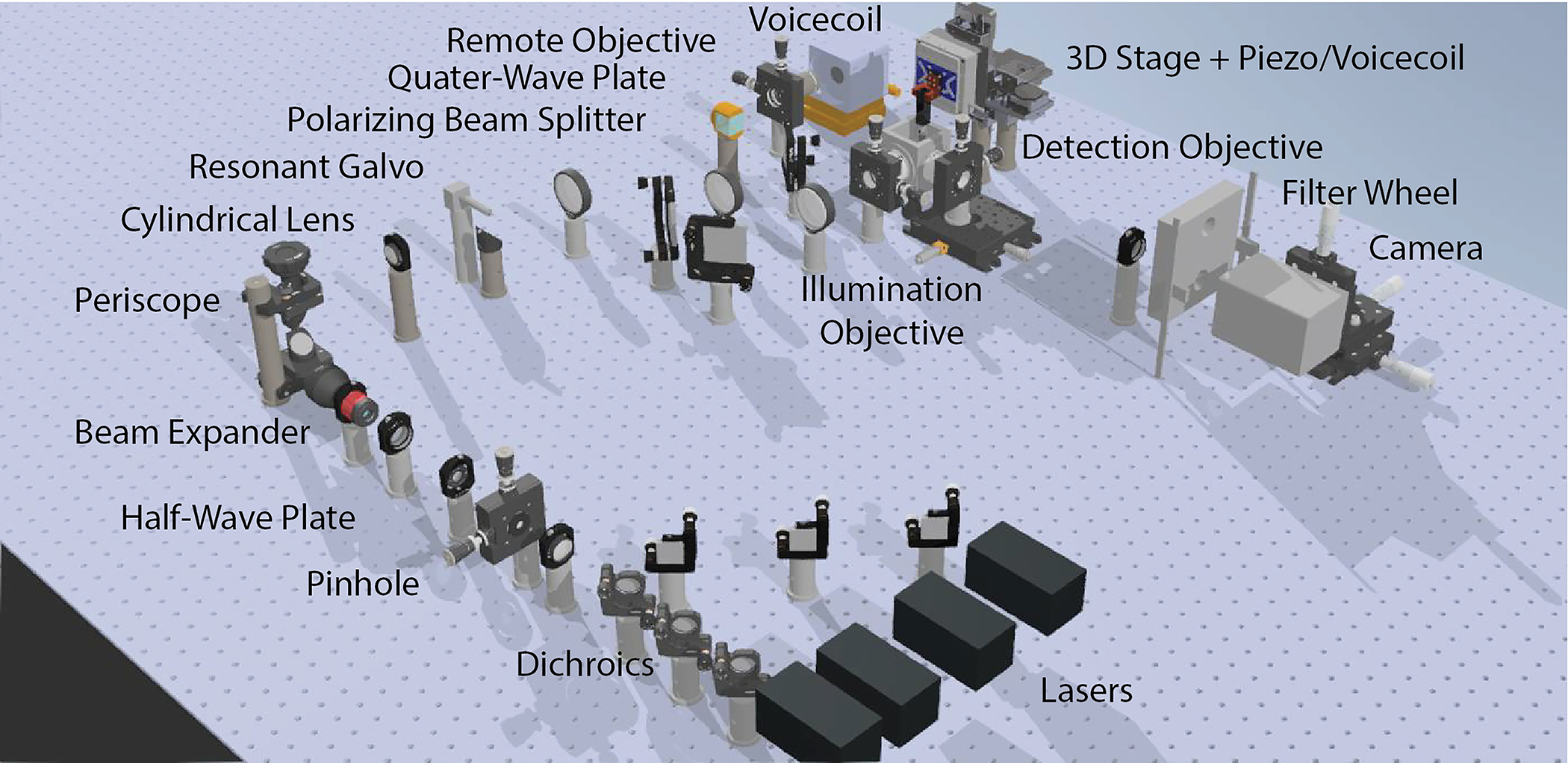

A CAD rendering of a complete sample scanning ctASLM-v1 system is shown in Fig. 7, and is publicly available online (see DOI:10.5281/zenodo.6048284, see also parts list in Table 2). Four laser lines are combined with dichroic mirrors and spatially filtered with a pinhole. After passing through a beam expander and a periscope, the laser beam is focused with a cylindrical lens onto a resonant galvo, which reflects the laser light downwards to the table. After being reflected by a static mirror into a horizontal propagation direction, the focused line is mapped via a lens and the remote objective onto the remote mirror, mounted on a voice coil actuator. A polarizing beam splitter, together with a quarter waveplate, sends the back reflected laser light via two relay lenses to the illumination objective, which forms the light-sheet in sample space. Fluorescence light is collected with the detection objective, oriented at 90 degrees to the optical axis of the illumination objective, and is imaged with a tube lens onto a scientific camera. All CAD documents are freely available on the AdvancedImagingUTSW GitHub repository (https://github.com/AdvancedImagingUTSW/manuscripts/tree/main/2021-dean-protocol/).

Figure 7. Complete CAD rendering of ctASLMv1.

The illumination source consists of 4 lasers that are combined with dichroic mirrors and focused through a pinhole to improve the beam quality. The filtered laser beam is then enlarged by a beam expander and raised to a 3.5” height above the table with a periscope. A cylindrical lens focuses the laser beam as a line onto the resonant galvo. A folding mirror brings the laser beam to a beam height of 3”. The laser beam passes through a polarizing beam splitter and a quarter-wave plate and is focused via the remote objective onto the remote mirror actuated by a voice coil actuator. The polarization of the returning beam is rotated by 90 degrees by the second pass through the quarter-wave plate and is reflected by the polarizing beam splitter. The laser beam is relayed to the illumination objective, which forms the light-sheet in sample space. The sample is mounted from the top into the sample chamber and positioned by a 3D stage and rapidly scanned in the third dimension by a piezo or voice coil actuator. Fluorescence light is collected by the detection objective and is imaged onto a scientific camera after passing a fluorescence filter.

Table 2.

Equipment List for ctASLM-v1.

| Item | Supplier | Catalog Number | Qty |

|---|---|---|---|

| 405 nm LX 50 mW Laser | Coherent | Coherent® OBIS™ 1284369 | 1 |

| 488 nm LX 150 mW Laser | Coherent | Coherent® OBIS™ 1220123 | 1 |

| 561 nm LS 50 mW Laser | Coherent | Coherent® OBIS™ 1230935 | 1 |

| 637 nm LX 140 mW Laser | Coherent | Coherent® OBIS™ 1196625 | 1 |

| OBIS LX/LS Single Laser Remote Control Box | Coherent | Coherent OBIS 1214875 | 4 |

| 613 nm single-edge laser dichroic beam splitter | Semrock | LM01-613-25 | 1 |

| 503 nm single-edge laser dichroic beam splitter | Semrock | LM01-503-25 | 1 |

| 427 nm single-edge laser dichroic beam splitter | Semrock | LM01-427-25 | 1 |

| Ø1” Protected Silver Mirror | Thorlabs | PF10-03-P01 | 6 |

| f=50 mm, Ø1” Achromatic Doublet | Thorlabs | AC254-050-A-ML | 1 |

| 30 ± 2 μm Pinhole | Thorlabs | P30K | 1 |

| f=200 mm, Ø1” Achromatic Doublet | Thorlabs | AC254-200-A-ML | 1 |

| Achromatic Waveplate, Half-Wave, Quartz-MgF2, 25.4 mm, 400-700 nm | Newport | 10RP52-1B | 1 |

| 5X Achromatic Galilean Beam Expander | Thorlabs | GBE05-A | 1 |

| Periscope assembly | Thorlabs | RS99 | 1 |

| Adjustable Mechanical Slit | Thorlabs | VA100 | 1 |

| Rotation Mount for Ø1” (25.4 mm) Optics | Thorlabs | RSP1 | 1 |

| f = 50.0 mm, Ø1” Cylindrical Achromat | Thorlabs | ACY254-050-A | 1 |

| Resonant galvanometer | Cambridge Technology | CRS 4 KHz | 1 |

| f = 200 mm, Ø2” Achromatic Doublet | Thorlabs | ACT508-200-A | 2 |

| Cube Beam splitter, Polarizing, 25.4 mm, 420-680 nm | Newport | 10FC16PB.3 | 1 |

| Vis Achromatic Quarter Wave Retarder | Boldervision | AQWP3 | 1 |

| 4x remote objective | Olympus | XLFLUOR4X/340 | 1 |

| 25mm Dia., 3mm Thick, VIS 0° Coated λ/4 N-BK7 Window | Edmund Opticss | #37-005 | 1 |

| Linear Focus Actuator with servo-controlled amplifier | Equipment Solutions | LFA-2010 with SCA814 servo-controlled amplifier | 1 |

| Tilt and Rotation Platform for mounting Linear Focus Actuator | Newport | #36 | 1 |

| Linear Stage for mounting Linear Focus Actuator; with Venier | Newport | #443, SM-50 | 1 |

| 2” × 2” protected silver mirror | Thorlabs | PFSQ20-03-P01 | 3 |

| f=75 mm, Ø2” Achromatic Doublet | Thorlabs | AC508-075-A-ML | 1 |

| 0.4 NA illumination objective | ASI | 54-10-12 Multi-Immersion Objective | 1 |

| High-Dynamics Linear Stage with motion controller | Physik Instrumente | V-522.1AA, C-413.2GA | 1 |

| 3 Axis Motorized Stage | Sutter Instrument | 3DMS-285 | 1 |

| Sample Chamber | Protolabs | Custom | 1 |

| 0.4 NA detection objective | ASI | 54-10-12 Multi-Immersion Objective | 1 |

| Tube Lens, f = 200 mm, ARC: 350 – 700 nm | Thorlabs | TTL200 | 1 |

| Emission Filter for 405 nm excitation | Semrock | FF01-445/20-25 | 1 |

| Emission Filter for 488 nm excitation | Semrock | FF01-525/30-25 | 1 |

| Emission Filter for 561 nm excitation | Semrock | FF01-605/15-25 | 1 |

| Emission Filter for 640 nm excitation | Semrock | FF01-660/30-25 | 1 |

| 4-position 25 mm filter wheel, with controller | Sutter Instrument | LB10-WHS4E with controller LB10-3 | 1 |

| 1/2” XYZ Translation Stage with Standard Micrometers for Mounting Camera | Thorlabs | MT3 | 3 |

| ORCA-Fusion Digital CMOS camera | Hamamatsu | C14440-20UP | 1 |

| FPGA | National Instruments | PCIe-7852R; SHC68-68-A2; SCB-68A | 1 |

| Diverse Opto-Mechanics | Thorlabs | ||

| Diverse BNC cables | Thorlabs | ||

| 200 nm Fluorescent Beads | Polysciences | 17151 | 1 |

| Computer | Colfax International | ProEdge SX6300 Workstation | 1 |

| Optical Table | Newport | OTS-UT2-46-8-1 | 1 |

| Test Clips | Thorlabs | T3788 | 10 |

| Agarose | Millipore Sigma | A4718 | 1 |

| Magnetic Beam Height Measurement Tool | Thorlabs | BHM1 | 1 |

| Alignment Disk | Thorlabs | DG10-1500-H1-MD | 1 |

| Shearing Interferometer | Thorlabs | SI050 | 1 |

| Shearing Interferometer | Thorlabs | SI100 | 1 |

| Post Holder | Thorlabs | PH1 | 10 |

| Mounted Standard Iris | Thorlabs | ID25 | 10 |

| Laser Safety Glasses | Thorlabs | LG4 | 1 |

The computer for operating the microscope benefits from having fast read/write capabilities, significant RAM, a powerful CPU, and ~4 PCIe-x16 slots on the motherboard. In contrast, a GPU is only necessary if you intend to render the data three-dimensionally, which adds a significant cost to the overall system. Supplementary Table 6 provides the configuration of an example computer, and a recommended BIOS configuration.

Materials

Equipment

Software

Several sources of microscope control software exist, each with their own advantages and disadvantages. These include but are not limited to μManager’s diSPIM module45, Pycro-Manager46, PYthon Microscopy Environment47, as well as commercially viable third-party options like Inscoper, LabView, and MATLAB. A key feature for robust microscope operation includes deterministic timing for all analog/digital inputs and outputs. To achieve this, our Light-Sheet Software package uses a field-programmable gate-array (FPGA) to deterministically control all aspects of microscope operation and is freely available for non-profit institutions through a Material Transfer Agreement with UT Southwestern Medical Center1. In brief, the waveforms (shown in Supplementary Figure 5) necessary for driving the microscope are calculated on the CPU and transferred to the FPGA for execution at a set frequency. Supplementary Table 7 lists the packages (and approximate costs) necessary for microscope control using our software within the LabView environment, or as a standalone executable program.

Equipment Setup

Installation of the Microscope Software

Install the frame grabber for the Hamamatsu Flash 4.0 into a PCIe x16 slot on the computer and connect the camera.

Download and install the DCAM-API software. This includes both the Active Silicone Firebird Module, and DCAM Tools. Confirm that the camera is functional by opening ExCap.

Install the 64-bit version of LabView 2016 and update all device drivers via the LabView automatic update. Register the software with your personal license information.

If you would like to run the software as an executable, install LabView Run-Time Engine.

Install the PCIe-based National Instruments 7852r FPGA in an x8 or x16 slot on the computer

Install NI-RIO Device Drivers for FPGA operation and register the FPGA.

Install the Vision Development Module, the Vision Run Time Engine, and the Vision Acquisition Software 18.5.1 version (VAS1851).

Upon completion of an MTA with the UT Southwestern Medical Center Tech Transfer office, pull the most recent version of the light-sheet software from AdvancedImagingUTSW GitHub repository (https://github.com/AdvancedImagingUTSW).

Configure the initialization file (e.g., \SPIM\SPIM Support files/SpimProject.ini) such that it includes proper RS232 COM ports and camera information (e.g., Serial Number). An example .ini file is provided on the AdvancedImagingUTSW GitHub repository (https://github.com/AdvancedImagingUTSW/manuscripts/tree/main/2021-dean-protocol/laser-alignment-tool)

CRITICAL STEP The wiring diagram for instrument control is provided in Supplementary Table 8 and 9. We recommend using a BNC to test clip adapter (T3788, Thorlabs) for wiring the breakout box, after removing the test clips and stripping the wires. These provide a convenient BNC adapter that can be used with appropriate 50-ohm input impedance (e.g., RG-58) cables. Supplementary Note 1 provides information on operating the software.

General Alignment Design Parameters

The height of the optical train must be specified in advance such that the tallest component in the path can be accommodated. Generally, we use a 3” (~76 mm) beam height and confirm this with a magnetic measurement tool (BHM1, Thorlabs). Some height changes might be introduced by folding mirrors, which change the beam height by approximately half an inch. The lateral and rotational alignment of each optical element added to the optical path is optimized by measuring its back reflections with a business card or a diffuser plate, each equipped with a ~1 mm diameter hole (e.g., DG10–1500-H1-MD, Thorlabs). Furthermore, the distance between every pair of lenses should be “4f” (e.g., a collimated beam that enters the lens pair remains collimated when it exits the lens pair), which can be confirmed with a shear plate interferometer (SI050 and SI100, Thorlabs). Also, it is convenient to use the hole pattern on the optical table as a reference, which can be confirmed through the placement of multiple irises (ID25, Thorlabs) that are directly mounted to the optical table with a post holder (PH1, Thorlabs). Supplementary Note 2 provides detailed methods on how to use each of these techniques to align an optical system.

Procedure

Installation of the Illumination Path Timing 3–4 days

Critical. To build an ASLM microscope, we typically start out with building the illumination train first. Once this beam path is fully aligned, the final location of the illumination defines where the detection objective and the corresponding detection path need to be positioned.

Critical The light-path of ctASLM initially starts with a 3.5” beam height, which is then switched to a 3” beam height with a folding mirror and a resonant mirror galvanometer. The resonant galvanometer is important for reducing shadow artifacts that arise from optical heterogeneities in the specimen48.

Critical Standard optical shutters (e.g., DSS10B, Uniblitz) can be used for simple systems. However, to minimize unnecessary exposure of the specimen with laser light between image acquisitions, higher bandwidth modulation of the laser power is preferable. To achieve this, we routinely use solid state lasers (OBIS LX, Coherent) that can be directly modulated with analog and digital waveforms at ~100 kHz. Alternatively, acousto-optic modulators (e.g., AOM-402AF1, IntraAction Corp.) or acousto-optical tunable filters (e.g., AOTFnC-400.650, AA Opto-Electronic) can be adopted.

Critical If the lasers do not have a nice TEM00 spatial mode and a beam quality (M2) less than 1.1, it may be necessary to install a spatial filter after the laser combining dichroics, shutters, modulators, etc. For a standard 0.7 mm diameter laser, this can be assembled using two 50 mm achromatic doublets (AC254–050-A-ML, Thorlabs) and a 100 μm pinhole (P100D, Thorlabs).

-

1

Install all lasers onto an optical table such that they emit at a 3.5” beam height and combine their emissions with laser multiplexing dichroics (e.g., LaserMUX Beam Combiners, Semrock). As seen in Fig. 6, typically each laser line has a normal mirror and a dichroic mirror, both in a kinematic mount. This allows alignment of the laser beam’s relative position and pointing (See also Supplementary Note 1 on Laser beam walking). Confirm that the lasers overlap perfectly immediately following the dichroics and after traveling ~6’ (2 m).

-

2

(Optional) If you need to clean the laser beam with a spatial filter, insert two 50 mm achromatic doublets (AC254–050-A-ML, Thorlabs) immediately after the laser combining dichroics into the beam path. For this, first align the first achromatic doublet by using irises in the beam path and by checking the lens back-reflection. Then place the second lens and confirm that the laser light is collimated with a shear plate interferometer (See also Supplementary Note 1, Measuring Collimation with a Shear Plate Interferometer).

-

3

Now place the 100 μm pinhole (P100D, Thorlabs) at the focal point and optimize its position by measuring the laser power after the second lens.

-

4

Install two irises into the optical path. The first should be located ~8” after the last laser combining dichroic (or the spatial filter), and the second should be located ~36” further downstream. The height of each iris should be 3.5”, and the lasers (each color) should go perfectly through the irises.

-

5

Immediately after the laser combining dichroics (or the spatial filter), place an achromatic beam expander (GBE20-A, Thorlabs), check its rotational and translational alignment with back-reflections (see also Supplementary Note 1, Optical Back Reflections), and confirm that the laser light coming out is collimated with a shear plate interferometer. The expanded laser light should remain aligned through downstream irises. If this is not the case, you have to realign the beam expander more carefully as failure to do so will result in uneven illumination of the specimen.

-

6

Close the iris immediately following the beam expander (henceforth referred to as the ‘alignment iris’) such that only a small portion of the beam remains, which is helpful for aligning subsequent lenses and optical elements with back-reflections.

-

7

Thread a mounted achromatic doublet (AC254–100-A-ML, Thorlabs) into a rotation stage that can be easily removed from the optical path. We recommend a manual rotation stage (RSP1, Thorlabs) and a flip mount (FM90, Thorlabs).

CRITICAL STEP This achromatic doublet, which is henceforth referred to as the ‘alignment lens’, will be replaced with a mounted cylindrical lens (ACY-254–050-A, Thorlabs) in the future, but working with a two-dimensional Gaussian beam greatly simplifies alignment tasks.

-

8

Place the resonant galvo (CRS 4 kHz, Cambridge Technologies) at the focus of the achromatic lens. Confirm that the resonant galvanometer is powered on, but with zero voltage applied to the external amplitude control input. For proper laser scanning, the position of the galvo must be critically aligned.

For rotational and translational positioning of the mirror, close the alignment iris to create a small diameter beam and back-reflect the laser light with the mirror galvanometer such that it traverses back through all upstream optics and is coincident with the exit aperture of the laser.

For axial (e.g., along the optical path) positioning of the mirror, open the alignment iris and confirm that the back-reflected light is collimated after traveling back through the achromatic lens that focused the laser onto the mirror galvanometer. This can be checked with a 50:50 non-polarizing beam splitter and a shear plate interferometer, or at least, by confirming that the laser is approximately the same size as the iris following the beam expander. This provides the correct position of the galvanometer in the direction of beam propagation. Once confirmed, carefully rotate the mirror galvanometer by 45 degrees so that the laser light is now being focused directly on the optical table. CAUTION Wear eye protection when working with the excitation laser turned on (e.g., Thorlabs, LG4). While class 3B lasers are considered generally safe, one should avoid eye exposure to direct or reflected beams, which is more likely when the laser is incident on the optical table.

-

9

Using a mirror mounted at 45 degrees (e.g., MA45–2, Thorlabs), with the center of the mirror positioned at a 3” beam height, reflect the laser light such that it is parallel to the surface of the optical table and traverses all downstream irises.

-

10

Place an achromatic doublet into the optical path to recollimate the laser. Confirm the proper positioning of the lens by measuring the back-reflections with a closed alignment iris, and by measuring its collimation with a shear plate and an open alignment iris.

-

11

Define a beam path close to the achromatic doublet, orthogonal to the beam, and ideally along the hole patterns of the optics table. This beam path will be the optical axis of the Remote focusing objective (see also Fig. 2). Place two irises, both at 3” height, in this beam path and insert the polarizing beam splitter so that the reflected beam passes both irises. To maximize the light reflected by the polarizing beam splitter, place a half-wave plate upstream before the achromatic beam expander (GBE20-A, Thorlabs) and rotate it until the laser power after the polarizing beam splitter is maximized.

-

12

Align the remote focusing objective as follows:

Remove the alignment lens immediately upstream of the resonant galvanometer.

Open the alignment iris and place the remote focusing objective where the laser comes to a focus. When the laser focus is conjugate with the back-pupil plane of the remote focusing objective a non-diverging (e.g., collimated) beam will emerge from the front pupil of the remote focusing objective. Despite being collimated, a beam with a small diameter will always diverge slightly. As such, we try to minimize the size of the beam several meters from the front pupil of the objective. Typically, the beam exiting the objective will appear diverging, and illuminate a large spot at the wall. The correct position of the remote focusing objective is found when the spot at the wall reaches its smallest size. Moving the objective beyond this optimal position will make the spot on the wall increase in size again. Note: The back-pupil plane of the objective is not necessarily coincident with the rear aperture of the objective and can exist within or outside of the physical housing of the objective itself, depending on its optical design.

Reintroduce the alignment lens, close the alignment iris, and align the remote focusing objective laterally with back-reflections. For precise alignment, mounting the remote focusing objective in a XY flexure translation stage (e.g., CP1XY, Thorlabs) can ease the alignment. Note: While stages improve ease of assembling the microscope, they also introduce additional sources of drift that can lead to a microscope becoming misaligned in time. We recommend using the minimal number of stages possible.

Remove the remote focusing objective from its mount, and introduce the remote focusing mirror assembly (mirror, voice-coil, tip-tilt stage, and translation stage). Confirm that the remote focusing voice-coil is powered on, and with 0 volts applied to the external amplitude control input (the voltage corresponding to the middle position of the voice-coil travel range). Align the mirror assembly such that the back-reflected beam travels through all upstream optics and is coincident with the alignment iris.

Carefully install the remote focusing objective back into its mount and translate the remote focusing mirror such that its surface is coincident with the laser focus. The mirror is properly positioned when the light exiting the remote focusing objective’s back pupil is collimated and has the same diameter as the alignment iris; i.e. the beam returning to the iris does not exceed its opening. By slightly moving the remote focusing mirror, one should see the beam returning to the iris grow or shrink beyond the open aperture of the iris. If the returning laser beam is not concentric with the alignment iris, slightly adjust the lateral position of the remote focusing objective. Only minor adjustments should be necessary, if at all.

-

13

Place a quarter-wave plate close to the back-pupil plane of the remote focusing objective. Then optimize the rotation of quarter-wave plate to maximize the laser power passing through the polarizing beam splitter into the downstream optical path. Using a shear plate interferometer, confirm that the laser beam has good collimation. If not, ever so slightly adjust the position of the remote focusing mirror.

-

14

Remove the alignment lens and introduce the first achromatic doublet of the telescope that relays the remote focused light towards the illumination objective. Proper axial placement of the achromatic doublet is achieved when it re-collimates the laser light, which can be confirmed with a shear plate interferometer. Lateral positioning of the achromatic lens can be verified by checking back reflections. This is best done after reintroducing the alignment lens and closing the alignment iris.

-

15

With the alignment lens in place, introduce the second achromatic doublet of the relay telescope such that the output (with an open alignment iris and the alignment lens in place) is collimated, and (with a closed alignment iris) optimize the back-reflections.

-

16

Remove the alignment lens and position the illumination objective (also mounted in a XY flexure stage) such that the light that emerges from its front pupil is collimated (by minimizing the size of the transmitted beam at a distance). As before, reintroduce the alignment lens, close alignment iris, and optimize back-reflections. Repeat until illumination objective is properly positioned.

?Troubleshooting

Installation of the Detection Path Timing 1–2 days

Critical The illumination objectives have a focal length that depends on the refractive index. Thus, in order to image in a diverse selection of immersion solvents, the detection system needs to be able to move in X (normal to the optical table), Y (along the illumination axis), and Z (along the detection axis).

Critical The camera fan introduces vibrations into mechanically soft samples, which can degrade the resolution of the microscope. To avoid this, we recommend cooling the camera with a chilled water source instead. Configure the camera for water cooling using the DCAM configurator and set the liquid temperature according to manufacturer’s recommendations to avoid condensation.

Critical Most objectives are designed to be coupled with an infinity-corrected tube lens, which provides apochromatically corrected and high-Strehl ratio imaging throughout the entire field of view. However, for high-resolution imaging, the magnification of the detection path may need to be increased to achieve Nyquist spatial sampling. For the high-resolution variant of ctASLM, we achieve this by using a 300 mm achromatic doublet (AC508–300-A, Thorlabs), which increases the magnification of the detection path 1.5-fold to 35.7X and yields an effective pixel size of ~180 nm. However, because achromatic doublets are much more sensitive to off-axis imaging, the entire detection train needs to be perfectly colinear.

Critical If imaging is performed at a distance other than the nominal focal plane of the tube lens, achromatic doublet, or detection objective, aberrations will be introduced that reduce the resolution and sensitivity of the microscope. We eliminate this possibility by directly measuring the working distance of the achromatic doublet or tube lens with a collimated laser and a camera, fixing the position of the camera, then aligning the remainder of the detection path. We note that if small amounts of spherical aberrations are present in the detection system, this can be compensated by axially translating the camera (away from the position where the collimated laser beam is perfectly focused on the camera) and refocusing the detection objective. This ideally introduces a spherical aberration with the opposite sign, compensating the residual spherical aberration of the objective.

-

17

Place a tube lens or achromatic doublet into a lens tube system (SM2E60, Thorlabs) with a rotating optical adjustment (SM2V15, Thorlabs) tube. The overall length of the tube system should be similar to the lens’ nominal focal length. Using a collimated laser source (ideally with a wavelength similar to that of your fluorescence emission), optimize the rotational and translational positioning of the lens tube system with back-reflections. Once the lens tube is aligned, identify the approximate location of the laser focus, and mount a cost-effective CMOS camera as alignment camera to the tube lens system at this location. Rotate the optically adjusted lens tube until a tight focus appears on the camera and lock the position so that it is secured.

-

18

Place the immersion chamber around the illumination objective (see Supplementary Note 3). Confirm that the silicone gaskets are sufficiently tight that they will withhold immersion media.

-

19

Add a long-pass emission filter (BLP01–514R-25, Semrock) and the detection objective to the lens tube system and mount the entire assembly on an XYZ stage (9063-XYZ, Newport) at a 3” beam height.

-

20

Slide the detection assembly through the remaining aperture in the immersion chamber and confirm with a standard carpentry square that the illumination and detection paths are oriented at 90-degrees relative to one another. Confirm that the silicone gasket is also secure around the detection objective.

-

21

With paper towels on hand in case the silicone gaskets leak, fill the immersion chamber with 50 μM fluorescein in water or phosphate buffered saline.

-

22

Replace the cylindrical lens in the illumination path with the alignment achromatic doublet lens and illuminate the fluorescent solution using a 488 nm laser. Use the alignment camera that is secured to the detection path to identify the location of the laser focus. Because we previously located the proper focal length of the achromatic doublet or tube lens and physically secured the camera, an in-focus image should only appear at the nominal focal length of the detection objective.

-

23

Secure the stage holding the detection assembly and remove the long-pass emission filter and alignment camera.

-

24

Place the emission filter wheel and scientific CMOS camera (Flash 4.0, Hamamatsu) into the detection path. Without changing the position of the detection assembly, use the fluorescent signal to align the camera such that the laser focus is perfectly centered on the camera detector. Confirm that the camera is oriented such that the rolling shutter on the camera is parallel or antiparallel, but not orthogonal, with the scan direction of the laser.

?Troubleshooting

Alignment of the Remote Focus Scan Timing 1–2 days

CRITICAL Once both the illumination and detection systems have been aligned relative to one another, fine alignments must be performed to optimize the remote focusing scan frequency and length (voltage range applied to the voice-coil). These should be performed using our Light-Sheet Software package (see Supplementary Note 1) since it will precisely control the timing of the remote focusing scan, camera triggering, and laser firing.

-

25

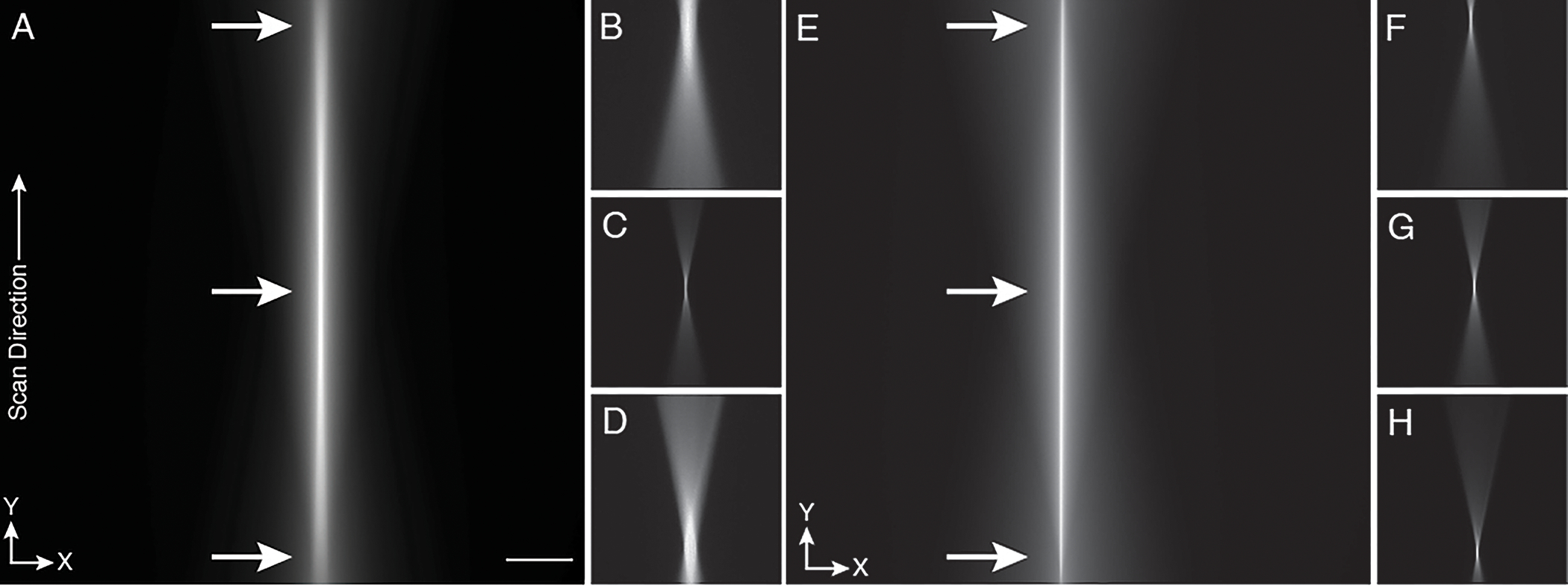

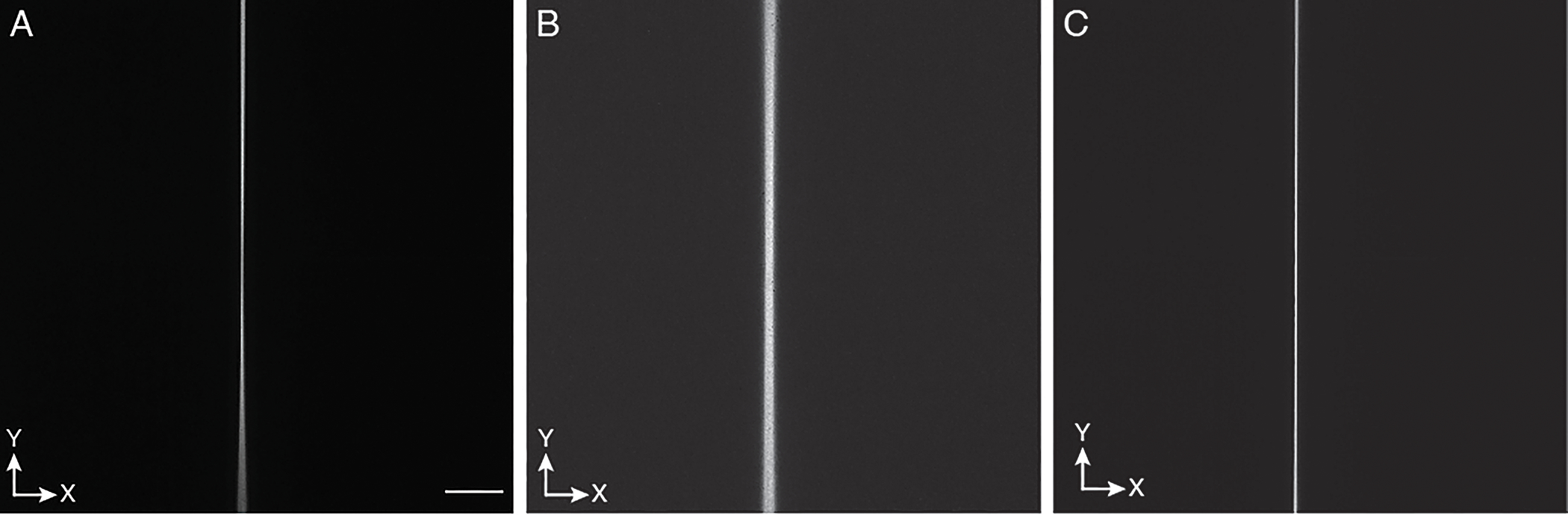

Precisely position the Gaussian laser focus in the center of the field of view by adjusting the remote focusing ‘Phase Delay’ in the Light-Sheet Software. Then, deliver a sawtooth waveform to the remote focusing voice-coil by adjusting the ‘Amplitude’ of the remote focusing scan range. Identify the scan range that allows the beam to scan throughout the complete field of view, as can be seen in Fig. 8a. The laser should have the same thickness throughout the entire field of view. In Fig. 8a, the alignment is not perfect; the beam waist has a different thickness at the ends of the field of view. This is particularly obvious if the remote focusing scan amplitude is set to 0, and an offset is delivered to the remote focusing unit to generate a stationary beam as in Fig. 8b, c, and d.

-

26

If the beam appears to be out of focus on one or two sides of the field of view, it is likely due to a tilt between the laser trajectory and the focal plane of the detection objective. To correct this, adjust the lateral position of the illumination objective and the Z-position of the detection objective in an iterative fashion while the remote focus scan is active. When the light-sheet uniformly comes into and out of focus as the Z-position of the detection objective is adjusted, and its width is uniform throughout the field of view, then the remote focus scan is aligned to the focal plane of the detection objective (Fig. 8e). Supplementary Fig. 4 provides a visual for this alignment protocol.

?Troubleshooting

-

27

Observe the static beams at the center and periphery of the field of view and confirm that the beam waist remains tight and in focus (Fig. 8f, g, and h). In the ideal case, each laser focus should be symmetric along its propagation axis (e.g., the Y-axis). Asymmetry of the laser focus along the propagation axis is likely due to spherical aberration, which can be corrected by adjusting the correction collar on the remote objective and correcting for any shifts in the laser focus with the Remote Focus Offset software feature or by translating the remote focus mirror slightly. Alternatively, if no correction collar is present, one can insert glass optical cover slides of defined thickness between the front pupil of the remote focusing objective and its mirror. If the aberrations of the lasers change as the beam is scanned along the propagation direction, this is usually a sign that the remote focusing system is not properly working and its alignment needs to be redone.

?Troubleshooting

Figure 8. Fine alignment of the ASLM scan.

For better alignment, the cylindrical lens is replaced with a regular achromatic lens of identical focal length, and the generated laser spot and laser scanning line are visualized with fluorescein solution. a, Fast scanning of the beam by the voice-coil mirror generates a line that spans the whole field of view. Inspection of the beam at both scan ends and, in the middle, (arrows) reveals differences in brightness and thickness indicating an imperfect alignment. b-d, This can further be illustrated by parking the beam at different offsets (arrow positions in panel a. The laser focus profile b, at the far end of the scan, c, at offset zero, i.e., in the middle and d, at the near end of the scan show different profiles. e, A perfectly aligned scanned beam shows the same brightness and profile across the full scan range, f-h, This is also confirmed by parking the beam at different offset positions indicated by arrows in panel e. The laser focus profiles f, at the far end, g, in the middle, h, and close end of the scan all reveal the same profile and thickness. Note: At this stage of the alignment, the rolling shutter feature of the camera is not turned on. The Y-direction is along the scan direction of the light-sheet. Scale bar: 100 microns.

Optimization of Remote Scan Parameters Timing 1 day

Critical. Depending on the remote focusing actuator technology, it is recommended to perform this optimization for different camera exposure times and fields of view.

-

28

Using the empirically determined Remote Focusing Amplitude and Offset from the previous step, activate the light-sheet mode of the camera. Depending on the orientation of the camera, this may have to be done from the ‘top to bottom’ or ‘bottom to top’ setting.

-

29

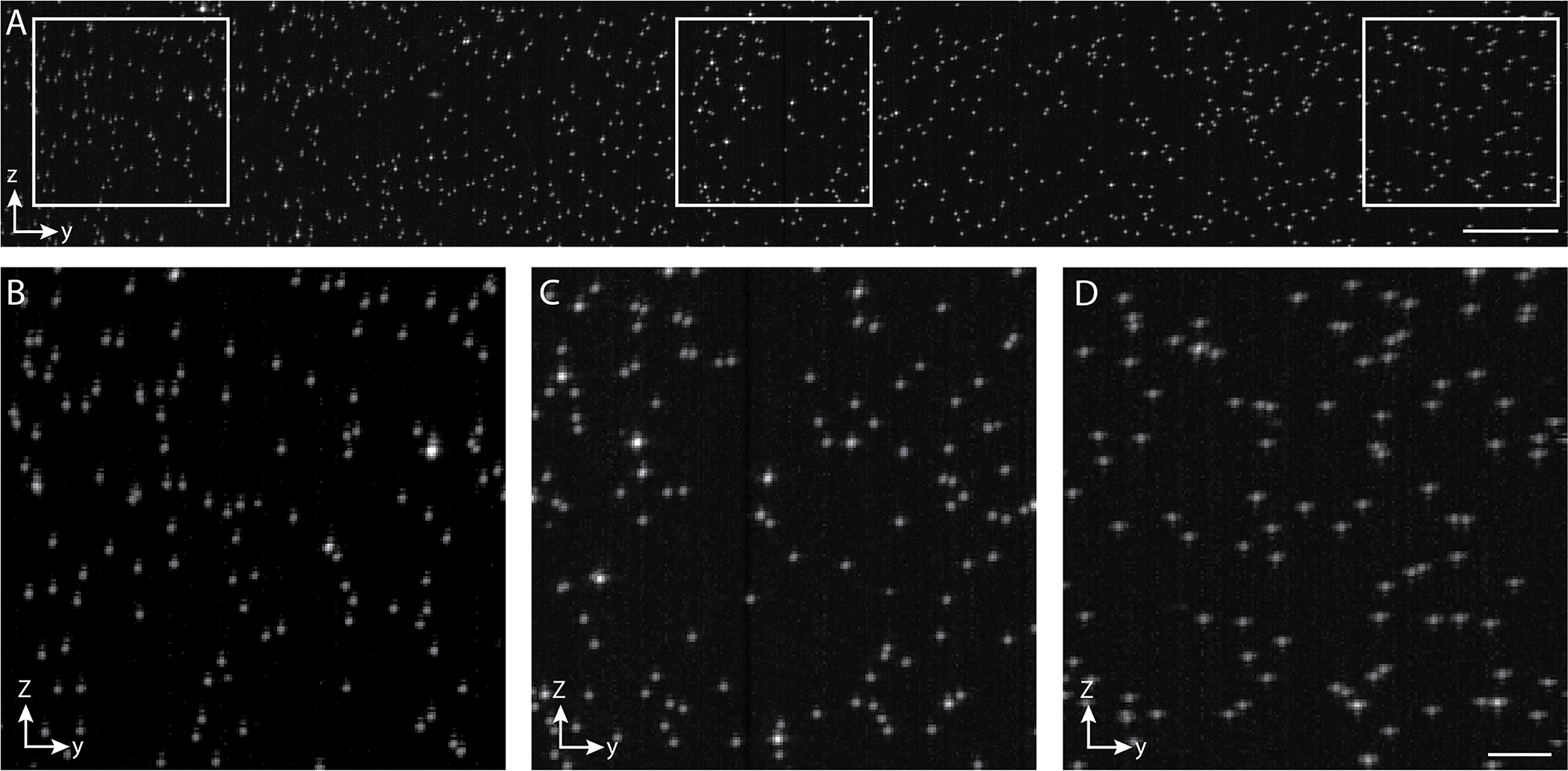

With the fluorescein solution as an imaging target, adjust the Remote Focusing Amplitude and Offset iteratively, and possibly the Z-position of the detection objective, until a narrow line appears.

If the line has a non-uniform width (Fig. 9a), adjust the Remote Focusing Amplitude.

If the line is too wide and appears blurry (Fig. 9b), adjust the Z-position of the detection objective to make it as narrow and sharp as possible.

Fig. 9c shows an image after the Remote Focusing Offset and Amplitude parameters have been successfully optimized.

If the line still has a non-uniform width after trying to correct it with these steps, this may be due to an insufficient bandwidth of the remote focusing actuator. To evaluate this, increase the camera integration time, which decreases the bandwidth demands of the actuator. Or, alternatively, increase the duration of the ‘flyback’ time between image planes for the actuator with the ‘Custom Cycle Time’ feature in our Light-Sheet Software. In general, the amplitude of the signal sent to the Remote Focusing actuator needs to increase in magnitude as the exposure time decreases and approaches the resonance frequency of the actuator.

-

30

Write the Remote Focusing Amplitude and Offset parameters down as they will be used routinely for ASLM imaging.

Figure 9. Adjusting the scan range and offset to the rolling shutter of the camera.

Scanning a 2D laser focus creates a line-shaped image: a, Example of a sub-optimal range for the laser scan, as one portion of the laser scan is out of sync with the camera rolling shutter. b, Example of a suboptimal offset for the scanning waveform for the laser focus: the laser focus is not in phase with the rolling shutter of the camera, leading to a blurry line. Note: blurriness of the line can also occur if the focal plane of the detection objective is off. c, Optimized range and offset for the scanning waveform. A thin line appears that does not change in width and brightness over the full field of view. The Y-direction is along the scan direction of the light-sheet. Scale bar: 100 microns.

Construction of the Sample Mounting System Timing 0.5 days

-

31

The sample mounting system consists of a motorized three-dimensional stage (MP-285, Sutter Instruments) for sample tiling, a fast piezo-electric actuator that scans the sample through the light-sheet during a Z-stack, and a series of adapters to mount the specimen to these stages. Supplementary Note 4 provides a detailed layout of the sample mounting system.

Place the sample mounting system on the optical table. Make sure that it is aligned such that the axes of stage travel are perfectly coincident with the illumination and detection axes. If a mismatch exists, the sample will not scan perfectly along the Z-direction and the imaging results might be hard to interpret.

Critical step The scan direction for the sample scanning piezo and the sample positioning stage need to be colinear, otherwise the 3D image stack will be flipped in Z. In principle, our Light-Sheet Software package allows this to be corrected, but we recommend using the configuration described in Supplementary Note 4 to avoid any confusion. Of note, the coordinate system of the sample positioning 3D stage is different than the coordinate system of the optical train. For example, the Z-axis of the sample positioning stage is perpendicular to the optical table surface, which is the X-axis for the optical system.

Fine Alignment of the Axially Swept Light-Sheet Scan Parameters Timing 3–4 days

-

32

Replace the achromatic alignment lens with a cylindrical lens. Rotate the cylindrical lens so that the beam in the back pupil of the illumination objective is approximately parallel with the optical surface of the optical table. This will create a light-sheet that is perpendicular to the surface of the optical table at the front focus of the objective.

-

33

Rinse the immersion chamber several times to remove the fluorescein solution, fill the immersion chamber with phosphate buffered saline or deionized water, and prepare an agarose cube with ~200 nm fluorescent nanospheres (See Supplementary Note 5). Mount the agarose cube to the sample mounting system.

-

34

Turn off the light-sheet mode of the camera so that it images in a traditional widefield detection format, set the Remote Focus Amplitude to 0, and place the agarose cube into the immersion chamber. The flat surfaces of the agarose cube should face the illumination and detection paths. Otherwise, refraction at the agarose water interface will occur.

-

35

Find the beam waist, which appears as a bright band of beads that are in focus. Ideally, they this band will be located in the middle of the field of view. Adjust the rotation of the cylindrical lens until the strip of in-focus beads is perfectly vertical. This can be verified by iteratively adjusting the focus of the detection system so that the in-focus region of beads uniformly come into and out of focus.

-

36

Switch to ASLM mode and observe the bead image. Adjust slightly the focus and offset of the remote focus scan to sharpen the image, and to make it as uniform as possible over the full field of view.

?Troubleshooting

-

37

Acquire a short Z-stack (e.g., over 20 microns depth) and compute the maximum intensity projection (MIP) in all three directions. These projections can help to identify residual alignment problems. In an axial side view along the scan direction, the beads should all be similarly confined in Z as shown in Fig. 10a–d. To get a clearer cross-sectional view of the beads, it is recommended to keep the range of the MIP to 50–100 pixels. If the axial extent of the PSF is getting wider to one side, adjust slightly the scan range, and acquire another stack. Sometimes it is also necessary to adjust the offset of the remote focus scan. If the scan range appears optimal, look at the top view MIP. If the beads exhibit non-uniform brightness across the field of view, this can be due to the following main reasons:

Light-sheet is still not scanning perfectly parallel to the focal plane of the detection objective (Scenario 1, schematically illustrated in Fig. 11a)

Light-sheet is slightly rotated in respect to the focal plane (Scenario 2, schematically illustrated in Fig. 11b)

?Troubleshooting

Figure 10. ASLM imaging of fluorescent nanospheres embedded in agarose.