Abstract

An 82-year-old man underwent an endovascular procedure with a commercially available endovascular graft for an anastomotic juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. The anastomotic aneurysm, which showed no sign of infection, developed 4 years after implantation of an aortic end-to-end graft for an infrarenal aortic aneurysm.

The aneurysm was diagnosed during routine ultrasonographic follow-up; there was no apparent infection of the graft. Aortography confirmed the diagnosis and also revealed a small pseudoaneurysm at the level of the distal aortic anastomosis. Endovascular surgery was performed in the operating room with the guidance of C-arm fluoroscopy and intravascular ultrasound. Two Vanguard™ Straight Endovascular Aortic Graft Cuffs (26 × 50 mm and 24 × 50 mm) were implanted, successfully excluding both the anastomotic juxtarenal aortic aneurysm and the distal pseudoaneurysm. The renal arteries were preserved and no early or late endoleaks were observed.

The patient was discharged 2 days after the procedure. Sixteen months later, he was alive and well, with no endovascular leakage, no enlargement of the aortic aneurysms, and no sign of infection.

In our opinion, this experience shows that commercially available endovascular grafts may be used successfully to treat anastomotic aortic aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms.

Key words: Anastomosis, surgical/adverse effects; aortic aneurysm, abdominal/surgery; blood vessel prosthesis; postoperative complications/surgery; reoperation; vascular surgical procedures/methods

Despite improved surgical techniques and materials, the incidence of anastomotic aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms is most likely underestimated: reports vary from 0.2% to 15%. 1–3 Untreated, anastomotic aneurysms are prone to the same complications as true aneurysms, including rupture, thrombosis, embolism, and compression or erosion of adjacent structures.

The operative morbidity and mortality rates of the traditional surgical approach for anastomotic aortic aneurysms are significantly higher than those of primary aortoiliac reconstructions. 1,4–8 Therefore, a less invasive endovascular approach is preferable.

Case Report

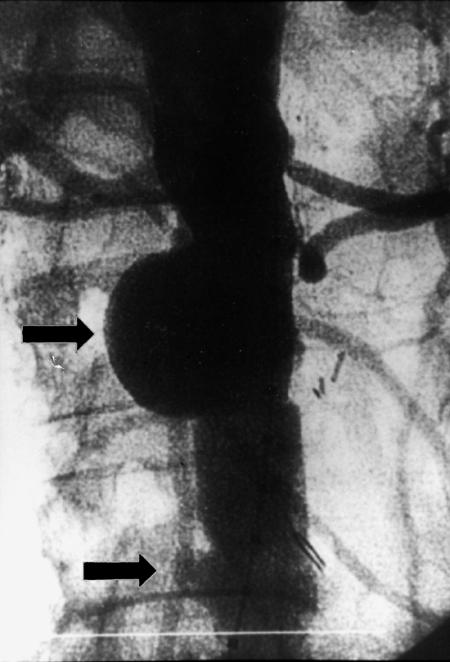

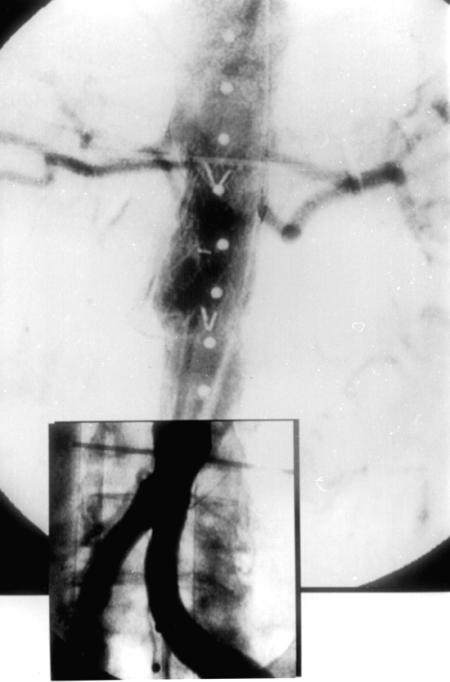

In February 1999, an anastomotic juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm exceeding 5 cm in diameter was diagnosed in an 82-year-old man during routine follow-up ultrasonography. In May 1995, he had undergone end-to-end infrarenal aortic grafting (Dacron®, 20-mm diameter) for an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. He had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and essential arterial hypertension, without concomitant cardiac or renal disease. Upon admission to the hospital, the patient was asymptomatic and in fair condition, with no recent history of fever or leukocytosis. No periprosthetic fluid suggesting infection of the original graft was observed on computed tomographic (CT) scanning of the abdomen (Fig. 1). Aortography was performed with a diagnostic catheter featuring 1-cm platinum markers for precise sizing of the aneurysm. The aortogram revealed 2 left renal arteries, the lower of which was immediately above a 5-cm-diameter anastomotic juxtarenal aortic aneurysm, with a lumen that was 42 mm in diameter. At the level of the distal aortic anastomosis on the right side, there was a small pseudoaneurysm, 12 mm in diameter (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 Preoperative computed tomographic scan showing the anastomotic juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Fig. 2 Preoperative aortography performed with calibrated pigtail catheter showing 2 left renal arteries, an anastomotic juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm (upper arrow), and a small distal pseudoaneurysm.

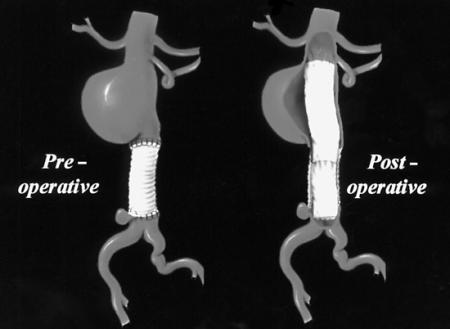

The endovascular repair was performed in the operating room, with the patient under general anesthesia and on heparin therapy (1 bolus dose of 70 IU/kg). The grafts were inserted through a right open femoral transverse arteriotomy, with use of an over-the-wire technique under fluoroscopic and intravascular ultrasound guidance. A percutaneous contralateral femoral approach was used for imaging during the procedure. We initially implanted a Vanguard™ Straight Endovascular Aortic Graft Cuff (26 × 50 mm; Boston Scientific Corporation; Natick, Mass) by anchoring the proximal endovascular graft portion inside the native juxtarenal aorta, with the covered stent-graft portion immediately below the lower left renal artery, and by anchoring the distal endovascular graft portion inside the previous aortic graft. The proximal uncovered endograft portion overlapped the lower left renal artery ostium. This allowed sufficient anchoring surface for the endograft, while preserving direct arterial flow to the renal artery. We then inserted the same type of aortic graft (24 × 50 mm) at the distal aortic anastomosis, anchoring the proximal end of the new endovascular graft inside the distal portion of the proximal endograft, and anchoring the distal part of the new endograft within the native aorta, immediately above the origin of the common iliac arteries (Fig. 3). This 2nd endovascular graft was placed to avoid excess aortic enlargement at the bifurcation by the greater proximal endograft. Thus, the smaller endograft (24-mm diameter) was inserted in the larger endograft (26-mm diameter) within the end-to-end aortic graft (20-mm diameter), resulting in sufficient oversizing of both endografts (Fig. 4). The insertion was successful; both the anastomotic juxtarenal aortic aneurysm and the distal pseudoaneurysm were completely excluded, with endografts overlapping. No expansion defects were noted, nor were there any early or late endovascular leaks. Right femoral artery reconstruction was performed using a running 5-0 polypropylene suture. No wound hematoma was noted, either at the surgical site or at the contralateral percutaneous access site.

Fig. 3 Final intraoperative aortography: both pseudoaneurysms are excluded and the renal arteries are preserved.

Fig. 4 Schematic drawings of the anastomotic juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm, end-to-end aortic graft, and final endograft positions.

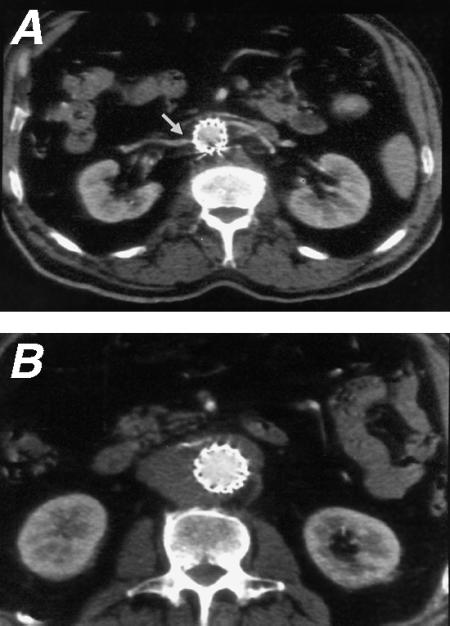

After 2 days, the patient was discharged from the hospital on antiplatelet therapy. The endografts, the renal arteries, the native iliofemoral system, and the internal iliac and medial sacral arteries were found to be patent during an angiographic study performed immediately after the procedure. These findings were confirmed by CT scanning performed 2 days later and again at 6 months (Fig. 5), and by color-coded duplex Doppler ultrasonography performed at 24 hours, 30 days, 3 months, and 6 months. Computed tomographic scanning was performed (Toshiba Xpress/SX spiral CT scanner; Toshiba Corp.; Tokyo, Japan) before and during bolus injection of a non-ionic iodinated contrast medium. Color-coded duplex Doppler ultrasonography was performed (HDI® 5000 system; ATL Ultrasound, a Phillips Medical Systems company; Bothell, Wash) both before and during intravenous injection of a microbubble contrast agent. At the 16-month follow-up visit, the patient was alive and asymptomatic. Ultrasonic examination at 12 months documented complete thrombosis of the anastomotic juxtarenal aortic aneurysm and of the distal pseudoaneurysm and revealed no new endovascular leaks, no enlargement of the juxtarenal aneurysm, and no infection. Plain abdominal radiography documented the absence of structural deterioration or distortion of the endovascular grafts.

Fig. 5 At the 6-month follow-up, computed tomographic scanning during a bolus injection of non-ionic iodinated contrast medium shows the patency of A) the renal artery at the level of the uncovered stent and B) the endograft.

Discussion

It is likely that the known incidence of anastomotic juxtarenal aortic aneurysms would be higher than that currently reported if all patients undergoing surgical treatment for abdominal aortic aneurysm were part of a routine follow-up program. Early detection and elective surgical repair of these anastomotic lesions, for which the prognosis is similar to that of true aneurysms, would minimize the morbidity and mortality rates of affected patients. Conventional elective repair is often challenging; it requires intraabdominal or retroperitoneal redissection through a scarred operative field 1,8 and frequently involves technically demanding aortic or iliac cross-clamping. Conventional elective surgical results are poor compared with those of primary surgery, and the emergency surgical mortality rates are high, ranging from 67% to 100%. 4–7

On the other hand, long-term results of endovascular treatment have not yet been established. Furthermore, this approach cannot be used unless the aneurysm has a proximal infrarenal aortic neck of at least 1 cm in length, and lack of a sufficiently long neck is not unusual in proximal anastomotic aortic aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. In patients with preserved renal function and patent renal arteries, total or partial interruption of renal perfusion by the covered portion of the endovascular graft would increase the risk of renal failure. Moreover, many anastomotic aneurysms are caused by infection; in these cases, endoluminal treatment does not allow total graft excision and débridement of infected tissue. In our patient, there was no clinical or radiologic evidence of infection.

A strong rationale exists for endovascular grafting in patients who have the appropriate morphologic features and are at high surgical risk. Endoluminal treatment minimizes operative blood loss and cardiac and pulmonary complications, reduces anesthetic and transfusion requirements, and entails a relatively rapid postoperative recovery. Furthermore, the type 2 endoleaks from patent collateral side branches described after endovascular treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms are not usually a concern with anastomotic aneurysms. 9,10 In our opinion, endografting of anastomotic aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms lessens the risk of peripheral emboli in the lower limbs compared with endografting of primary abdominal aortic and iliac aneurysms. The intraaortic maneuvers are performed through the smooth graft rather than through an irregular, often tortuous, thrombotic, and thus potentially embolus-producing aortic wall. In 1997, Dr. Yuan's group 11 used an endovascular technique to treat 2 aortic anastomotic aneurysms, among a total of 12 isolated or combined aortic or iliac anastomotic aneurysms in 10 patients. Custom polytetrafluoroethylene aortoiliac endografts were used successfully in association with endovascular exclusion of the contralateral iliac artery and surgical revascularization via a femorofemoral bypass graft. 11 In our patient, we used commercially available endovascular grafts; we believe our experience to be the 1st reported successful use of such grafts for treatment of an anastomotic aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Dr. Germano Melissano, Divisione di Chirurgia Vascolare, IRCCS H. San Raffaele, Via Olgettina 60 - 20132 Milano, Italy

References

- 1.Szilagyi DE, Smith RF, Elliott JP, Hageman JH, Dall'Olmo CA. Anastomotic aneurysms after vascular reconstruction: problems of incidence, etiology, and treatment. Surgery 1975;78:800–16. [PubMed]

- 2.Mikati A, Marache P, Watel A, Warembourg H Jr, Roux JP, Noblet D, et al. End-to-side aortoprosthetic anastomoses: long-term computed tomography assessment. Ann Vasc Surg 1990;4:584–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.van den Akker PJ, Brand R, van Schilfgaarde R, van Bockel JH, Terpstra JL. False aneurysms after prosthetic reconstructions for aortoiliac obstructive disease. Ann Surg 1989;210:658–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Treiman GS, Weaver FA, Cossman DV, Foran RF, Cohen JL, Levin PM, et al. Anastomotic false aneurysms of the abdominal aorta and the iliac arteries. J Vasc Surg 1988;8:268–73. [PubMed]

- 5.Curl GR, Faggioli GL, Stella A, D'Addato M, Ricotta JJ. Aneurysmal change at or above the proximal anastomosis after infrarenal aortic grafting. J Vasc Surg 1992;16:855–60. [PubMed]

- 6.Allen RC, Schneider J, Longenecker L, Smith RB 3d, Lumsden AB. Paraanastomotic aneurysms of the abdominal aorta. J Vasc Surg 1993;18:424–32. [PubMed]

- 7.Edwards JM, Teefey SA, Zierler RE, Kohler TR. Intraabdominal paraanastomotic aneurysms after aortic bypass grafting. J Vasc Surg 1992;15:344–53 [see discussion by Ernst CB, p. 351]. [PubMed]

- 8.Crawford ES, Manning LG, Kelly TF. “Redo” surgery after operations for aneurysm and occlusion of the abdominal aorta. Surgery 1977;81:41–52. [PubMed]

- 9.Marin ML, Veith FJ, Cynamon J, Sanchez LA, Lyon RT, Levine BA, et al. Initial experience with transluminally placed endovascular grafts for the treatment of complex vascular lesions. Ann Surg 1995;222:449–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Moore WS, Vescera CL. Repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm by transfemoral endovascular graft placement. Ann Surg 1994;220:331–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Yuan JG, Marin ML, Veith FJ, Ohki T, Sanchez LA, Suggs WD, et al. Endovascular grafts for noninfected aortoiliac anastomotic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 1997;26:210–21. [DOI] [PubMed]