Abstract

Background

Inequitable access to high‐technology therapeutics may perpetuate inequities in care. We examined the characteristics of US hospitals that did and did not establish left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) programs, the patient populations those hospitals served, and the associations between zip code–level racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic composition and rates of LAAO among Medicare beneficiaries living within large metropolitan areas with LAAO programs.

Methods and Results

We conducted cross‐sectional analyses of Medicare fee‐for‐service claims for beneficiaries aged 66 years or older between 2016 and 2019. We identified hospitals establishing LAAO programs during the study period. We used generalized linear mixed models to measure the association between zip code–level racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic composition and age‐adjusted rates of LAAO in the most populous 25 metropolitan areas with LAAO sites. During the study period, 507 candidate hospitals started LAAO programs, and 745 candidate hospitals did not. Most new LAAO programs opened in metropolitan areas (97.4%). Compared with non‐LAAO centers, LAAO centers treated patients with higher median household incomes (difference of $913 [95% CI, $197–$1629], P=0.01). Zip code–level rates of LAAO procedures per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries in large metropolitan areas were 0.34% (95% CI, 0.33%–0.35%) lower for each $1000 zip code–level decrease in median household income. After adjustment for socioeconomic markers, age, and clinical comorbidities, LAAO rates were lower in zip codes with higher proportions of Black or Hispanic patients.

Conclusions

Growth in LAAO programs in the United States had been concentrated in metropolitan areas. LAAO centers treated wealthier patient populations in hospitals without LAAO programs. Within major metropolitan areas with LAAO programs, zip codes with higher proportions of Black and Hispanic patients and more patients experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage had lower age‐adjusted rates of LAAO. Thus, geographic proximity alone may not ensure equitable access to LAAO. Unequal access to LAAO may reflect disparities in referral patterns, rates of diagnosis, and preferences for using novel therapies experienced by racial and ethnic minority groups and patients experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, ethnic groups, fee‐for‐service plans, left atrial appendage occlusion, Medicare, racial groups, socioeconomic factors

Subject Categories: Atrial Fibrillation, Disparities, Social Determinants of Health

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CBSA

core‐based statistical area

- CMS

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

- DCI

Distressed Communities Index

- LAAO

left atrial appendage occlusion

- PREVAIL

Prospective Randomized Evaluation of the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure Device in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Versus Long‐Term Warfarin Therapy

- PROTECT‐AF

Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Closure Versus Warfarin for Atrial Fibrillation

- TAVR

transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

The growth in left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) programs in the United States between 2016 and 2019 has been concentrated in metropolitan areas.

Hospitals establishing LAAO programs tended to treat wealthier patient populations than hospitals that did not establish LAAO programs.

In major metropolitan areas with LAAO programs, zip codes with more patients of lower socioeconomic status and higher proportions of Black or Hispanic patients had lower rates of LAAO compared with zip codes with more affluent and White patients.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in the use of LAAO persist despite growth in site‐level adoption of the procedure.

Focused efforts are needed to identify specific mechanisms through which barriers to accessing LAAO arise.

These results should inform future policies and practices that work to ensure equitable access to structural heart interventions.

Since its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2015, percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) with the Watchman device (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) has emerged as an alternative stroke prevention therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). 1 , 2 , 3 LAAO may meet clinical needs in patients with AF who are not anticoagulated and/or have contraindications to anticoagulation therapies. 4 Updated American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines recommend consideration of percutaneous LAAO with Watchman in patients with AF at increased risk of stroke who have contraindications to long‐term anticoagulation. 5

Despite the potential benefits of LAAO, Black and Hispanic patients, as well as patients experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage, are underrepresented among those undergoing LAAO. 6 , 7 The diffusion of novel medical technologies has historically suffered socioeconomic, geographic, racial, and ethnic inequities that perpetuate disparities in access to high‐quality health care. 8 , 9 These disparities may be explained by the interaction of geographic proximity and other factors such as biases in care delivery, language barriers, and social determinants of health.

Prior work has found disparities in the use of other structural heart interventions such as transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and transcatheter mitral valve repair. Most previous studies evaluating disparities in LAAO have focused on outcomes (eg, mortality, adverse events). No prior study has comprehensively examined racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in access to and use of LAAO. This study sought to better understand the drivers of disparities in access to LAAO by evaluating the characteristics of hospitals that developed new LAAO programs, the socioeconomic characteristics of patient populations served by LAAO hospitals versus non‐LAAO hospitals, and the associations between zip code–level racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic composition and rates of LAAO among Medicare patients living in populous metropolitan areas with LAAO programs.

METHODS

This study was deemed exempt by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania. No informed consent was required for this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data used for this study are covered by a data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Data are not available for distribution by the authors but can be obtained from the CMS with an approved data use agreement.

Study Cohort

The Medicare Provider Analysis and Review data files and the Master Beneficiary Summary data files were used to identify Medicare fee‐for‐service beneficiaries aged 66 years or older who underwent LAAO between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2019. We implemented an age cutoff of 66 years to allow for a 12‐month lookback period to fully evaluate patient comorbidities. Patients undergoing LAAO were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10) procedure code (02L73DK), which during the study period predominantly reflects use of the Watchman device. 10 During the study period, LAAO with the Watchman device was designated by the CMS as an inpatient‐only procedure.

Because the 2016 CMS National Coverage Determination for LAAO requires hospitals starting LAAO programs to have a structural heart program and/or electrophysiology program, only hospitals with existing TAVR programs and/or intracardiac ablation programs during the study period were considered candidate hospitals for the development of an LAAO program. These were chosen as surrogates for structural and electrophysiology programs, respectively. Hospitals were considered candidate hospitals if they coded for ≥5 TAVR procedures and/or intracardiac ablation procedures during the study period. All hospitals not meeting this criterion were excluded from all analyses. Hospitals that performed ≥10 LAAO procedures in a calendar year were defined as LAAO programs for that year and all subsequent years. A sensitivity analysis was performed with a threshold of 5 LAAO procedures.

Patient and hospital zip code data were obtained from the Medicare Hospital Data Claims and Demographic Data files. We assigned patients and hospitals to individual core‐based statistical areas (CBSAs) using zip code to CBSA crosswalk files from the US Department of Housing as previously described. 11 Individual zip codes were classified as metropolitan (areas with at least 50 000 people) or micropolitan (areas with 10 000 to 50 000 people) based on the 2010 CBSA designation. 12 Zip codes not linked to metropolitan or micropolitan CBSAs were defined as rural. Among metropolitan CBSAs with at least 1 hospital with an LAAO program, we identified the 25 largest metropolitan CBSAs by population as of the 2010 US Census.

Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Identification

Beneficiaries' race and ethnicity were determined from Medicare Demographic Data files. Socioeconomic status (SES) of Medicare fee‐for‐service beneficiaries was evaluated using median household income of the patient's zip code of residence, dual‐eligibility status for Medicaid, and the Distressed Communities Index (DCI) score. 13 , 14 , 15 Higher DCI scores indicate more community‐level distress. Each of these markers was assessed at the level of the zip code for patient residence.

Statistical Analysis

We compared characteristics of hospitals that established LAAO programs with characteristics of hospitals that did not establish LAAO programs using the Student t test for means and χ2 analysis for proportions, as appropriate.

Among LAAO hospitals, we determined the first year that a hospital became an LAAO program. Hospitals were considered nonadopters for each year before establishment of an LAAO program. We identified hospitals establishing new LAAO programs in each year of the study period. We visualized the geographic distribution of new sites by plotting a map showing each new LAAO program's location and year of establishment. We also generated a stacked bar plot to show the annual frequencies of new LAAO sites based on the site location's metropolitan designation and whether the LAAO site opened in a CBSA with a preexisting LAAO program.

Indicators for SES (median household income, percentage of Medicaid dual eligible beneficiaries, and mean DCI) were identified for all inpatients treated in the year preceding LAAO adoption. Student t tests for means were used to compare socioeconomic characteristics of patients served by hospitals establishing LAAO programs with patients served by hospitals not establishing LAAO programs.

Our primary outcome of interest was the zip code–level age‐ and comorbidity‐adjusted rate of LAAO per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries. Comorbidity adjustment included covariates for zip code–level rates of AF and stroke. Age‐adjusted LAAO rates were compared across zip code–level tertiles of socioeconomic indicators using the Kruskal‐Wallis test.

For our primary analysis, we generated generalized linear mixed models with Poisson distribution and log‐link function to model the association between zip code–level racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic composition and zip code–level LAAO rates in the 25 largest CBSAs with LAAO programs. We limited our analysis to the 25 largest CBSAs to identify associations between LAAO rates and zip code–level racial and socioeconomic composition in areas where geography is not a barrier to accessing LAAO. In the primary model, we adjusted for age and clinical comorbidities (congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, AF, peripheral vascular disease, kidney disease, and liver disease). Each of the 3 indicators for SES was introduced separately as a covariate into the model. We clustered the data at the CBSA level using a mixed‐effects approach to better capture variations in LAAO rates within each specific CBSA and adjust for geographic region. In a secondary model, we added covariates for the proportion of Black or Hispanic beneficiaries within each zip code. Sensitivity analyses of the primary and secondary models were performed using all metropolitan CBSAs with LAAO programs.

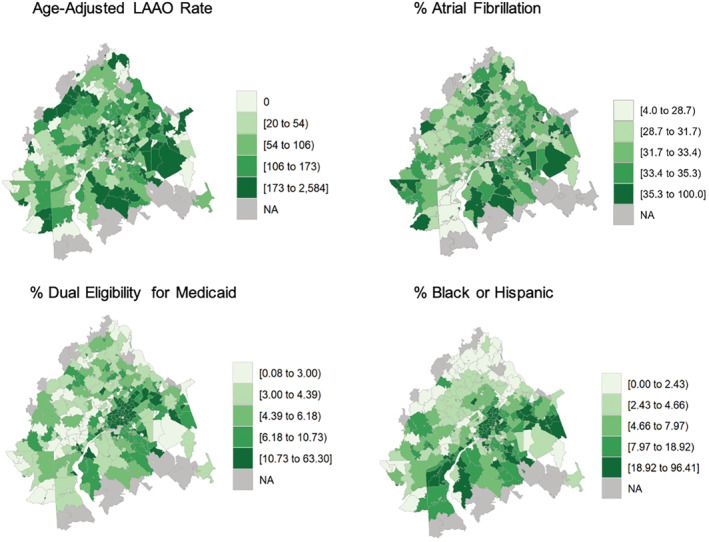

We visualized variation in rates of LAAO within the 25 largest CBSAs with LAAO programs by plotting choropleths (color‐coded maps) of age‐adjusted LAAO rates by zip code. We also plotted corresponding zip code–level choropleths of proportions of beneficiaries with AF, proportions of Medicaid dual‐eligible patients, and proportions of Black or Hispanic patients.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Choropleths were generated using R version 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All statistical testing was 2‐tailed, with P values <0.05 designated statistically significant.

RESULTS

In the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review data files, we identified 4780 relevant hospitals (ie, inpatient prospective payment system hospitals and critical access hospitals) in the 50 US states and the District of Columbia. Of those, 3510 hospitals without LAAO, TAVR, or intracardiac ablation programs were excluded, leaving 1270 candidate hospitals considered in our analyses. Complete details on the selected hospital cohort are provided in Figure S1.

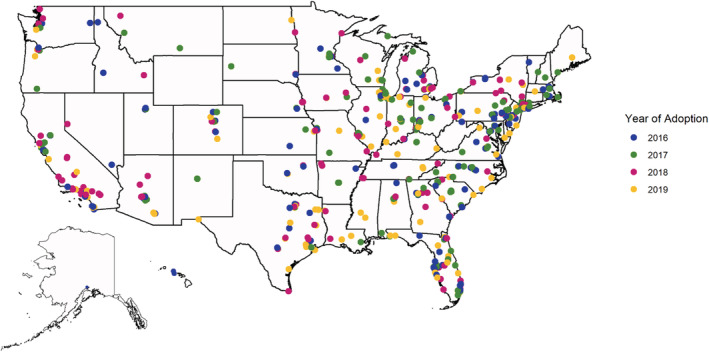

We identified 525 hospitals that had established LAAO programs by December 31, 2019, with 507 new LAAO programs opened in the study period (Figure 1). Of those, 494 LAAO centers opened in metropolitan areas (97.4%) and 13 (2.6%) in micropolitan and rural areas. Furthermore, 246 LAAO centers opened in metropolitan areas with preexisting LAAO programs (48.5%). The number of new LAAO programs decreased annually from a high of 140 in 2017 to 115 in 2019 (P=0.05) (Figure S2). Patients living in the 217 CBSAs with LAAO programs had higher rates of LAAO procedures per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries than patients living in the 709 CBSAs without LAAO (130 versus 82, P<0.01).

Figure 1. Newly established left atrial appendage occlusion programs in the United States, 2016 to 2019.

Hospitals establishing LAAO programs tended to have ≥400 beds (P<0.01) and be teaching hospitals (P<0.01) (Table S1). Compared with non‐LAAO hospitals, hospitals establishing LAAO programs treated patients with higher median household incomes ($913 [95% CI, $197–$1629], P=0.01), fewer Medicaid dual‐eligible patients (−2.9 percentage points [95% CI, −3.4 to −2.3], P<0.01), and patients from areas with lower DCI (−2.3 [95% CI, −3.1 to −1.4], P<0.01) [Table 1]. We observed similar trends in the sensitivity analysis of ≥5 LAAO procedures to designate LAAO adoption.

Table 1.

Difference in Socioeconomic Characteristics of Patients Served by Hospitals That Did and Did Not Start New LAAO Programs

| LAAO program, n=525 | No LAAO program, n=745 | Difference (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median household income, $, mean (SD) | 56 997 (12 281) | 56 084 (13 173) | 913 (197 to 1629) | 0.0146 |

| Distressed Communities Index, unit, mean (SD) | 42.4 (13.6) | 44.7 (16.1) | −2.3 (−3.1 to −1.4) | <0.0001 |

| Dual eligibility for Medicaid, %, mean (SD) | 11.8 (7.4) | 14.7 (11.0) | −2.9 (−3.4 to −2.3) | <0.0001 |

LAAO indicates left atrial appendage occlusion.

In the 25 largest CBSAs with LAAO programs, there were 7532 individual zip codes. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) number of LAAO hospitals per CBSA was 6 (5–9). The mean (SD) age of Medicare beneficiaries within these CBSAs was 73.1 (1.5) years. A mean (SD) of 47.7% (5.7%) of beneficiaries were men, and a mean (SD) of 72.8% (25.2%) were White, 11.3% (19.2%) were Black, 4.2% (7.3%) were Asian, and 8.2% (13.0%) were Hispanic. The median (IQR) household income was $62 235 ($46 479–$83121), median (IQR) proportion of Medicaid dual‐eligible patients was 6.6% (3.7%–12.7%), and the median (IQR) DCI score was 28.5 (11.8–55.9) (Table S2).

Within the studied major metropolitan CSBAs with LAAO programs, the median (IQR) rate of LAAO per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries by zip code was 23 (0–110) (Table S2). We divided zip codes into tertiles by markers of SES, and found that age‐adjusted rates of LAAO were higher in zip codes with higher median household incomes (median [IQR], 45 [0–126] LAAO per 100 000 beneficiaries) compared with lower median incomes (median [IQR], 0 [0–82]; P<0.01). We observed similar trends when comparing zip codes with lower proportions of patients dually eligible for Medicaid (median [IQR], 29 [0–139]) with zip codes with higher proportions (median [IQR], 0 [0–77]; P<0.01), and zip codes with low DCI (median [IQR], 82 [6–154]) with zip codes with high DCI (median [IQR], 33 [0–104]; P<0.01) (Table S3).

Results of our primary model measuring the association between zip code–level socioeconomic composition with rates of LAAO per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries, adjusting for age and clinical comorbidities, are presented in Table 2. For each $1000 decrease in median household income, the number of LAAO procedures performed per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries was 0.34% (95% CI, 0.33%–0.35%) lower (P<0.01). In other words, every $1000 reduction in zip code–level median household income is associated with a 0.34% relative decrease in the number of LAAO procedures performed per 100 000 beneficiaries at the zip code level. For each 1% increase in the proportion of Medicaid dual‐eligible patients, the number of LAAO procedures performed per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries was 1.76% (95% CI, 1.72%–1.79%) lower (P<0.01). For each 1‐unit increase in DCI score, the number of LAAO procedures performed per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries was 0.10% (95% CI, 0.09%–0.12%) lower (P<0.01). We observed similar trends in the sensitivity analysis of all metropolitan CBSAs with LAAO programs.

Table 2.

Association Between Zip Code–Level Markers of Socioeconomic Status and Rates of LAAO per 100 000 Medicare Beneficiaries in 25 Largest Core‐Based Statistical Areas With LAAO Programs, Adjusting for Clinical Comorbidities

| Indicator | Difference in no. of LAAOs per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries, % (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Median household income per $1000 decrease | −0.34 (−0.35 to −0.33) | <0.0001 |

| Dual eligibility for Medicaid per 1% increase | −1.76 (−1.79 to −1.72) | <0.0001 |

| Distressed Communities Index score per 1‐unit increase | −0.10 (−0.12 to −0.09) | <0.0001 |

LAAO indicates left atrial appendage occlusion.

Results of our secondary model measuring the associations between race, ethnicity, and rates of LAAO per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries are presented in Table 3. After adjusting for median household income, for each 1% increase in proportion of Black patients within a zip code, the number of LAAO procedures performed per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries was 0.75% (95% CI, 0.73%–0.77%; P<0.01) lower, and for each 1% increase in the proportion of Hispanic patients, the number of LAAO procedures performed per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries was 2.01% (95% CI, 1.98%–2.04%; P<0.01) lower. Similar results were obtained when adjusting for proportion of Medicaid dual‐eligible patients and DCI. In the sensitivity analysis of all metropolitan CBSAs with LAAO programs, comparable results were obtained.

Table 3.

Association Between Zip Code–Level Markers of Socioeconomic Status, Race, Ethnicity, and Rates of LAAO per 100 000 Medicare Beneficiaries in 25 Most Populous Core‐Based Statistical Areas With LAAO Programs, Adjusting for Clinical Comorbidities

| Difference in no. of LAAOs per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries, % | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median household income, per $1000 decrease | −0.19 | −0.20 to −0.18 | <0.0001 |

| Black race, per 1% increase | −0.75 | −0.77 to −0.73 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic ethnicity, per 1% increase | −2.01 | −2.04 to −1.98 | <0.0001 |

| Dual eligibility for Medicaid (per 1% increase) | −0.60 | −0.64 to −0.56 | <0.0001 |

| Black race, per 1% increase | −0.76 | −0.78 to −0.74 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic ethnicity, per 1% increase | −1.89 | −1.93 to −1.86 | <0.0001 |

| Distressed Communities Index score, per 1‐unit increase | −0.06 | −0.07 to −0.04 | <0.0001 |

| Black race, per 1% increase | −0.83 | −0.87 to −0.79 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic ethnicity, per 1% increase | −0.25 | −0.28 to −0.22 | <0.0001 |

LAAO indicates left atrial appendage occlusion.

Choropleths of the studied metropolitan CBSAs showed that zip codes having higher age‐adjusted rates of LAAO per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries colocalized with those having smaller proportions of Medicaid dual‐eligible patients and lower proportions of Black and/or Hispanic patients. The Philadelphia, Pennsylvania‐Camden, New Jersey‐Wilmington, Delaware CBSA is presented in Figure 2. In wealthy suburban areas west of Philadelphia with fewer Black and Hispanic patients, there were higher relative local rates of LAAO per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries compared with areas of lower SES and/or more Black and Hispanic residents. Similar maps for all studied CBSAs are provided in Figure S3.

Figure 2. Choropleths demonstrating geographic variation in the age‐adjusted rate of left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) performed per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries, as well as the proportion of beneficiaries with atrial fibrillation, proportion of patients dual‐eligible for Medicaid, and proportion of Black or Hispanic patients for each zip code within the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania‐Camden, New Jersey‐Wilmington, Delaware core‐based statistical area.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the characteristics of new LAAO centers in the United States, the patient populations those centers serve, and the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in access to LAAO in major metropolitan areas. We found that the overall number of LAAO centers in the United States has grown significantly, and that most new LAAO sites opened in metropolitan areas. LAAO sites served patients residing in wealthier neighborhoods with lower levels of community distress, and fewer Medicaid dual‐eligible patients, compared with non‐LAAO hospitals. Within major metropolitan areas with LAAO programs, areas with markers of low SES or greater proportions of Black or Hispanic patients had lower age‐adjusted rates of LAAO. Race and ethnicity were independently associated with lower LAAO rates even after adjusting for socioeconomic measures. Taken together, these findings suggest that in major metropolitan areas, where geographic proximity to an LAAO center is not an issue, patients experiencing lower levels of SES and racially and ethnically minoritized groups may still have less access to this procedure.

These findings add to a growing body of work that underscores similar racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in the diffusion of other structural heart procedures, such as TAVR and transcatheter mitral valve repair. 6 , 7 , 9 , 11 , 16 However, differences in preprocedural requirements for structural heart interventions may suggest that patients face unique barriers to accessing LAAO compared with TAVR. These findings are consistent with a larger body of literature that has found persistent racial and socioeconomic disparities in access to specialized cardiovascular procedures including cardiac catheterization and percutaneous intervention. 17 , 18 , 19 The unequal diffusion of novel cardiac technologies may be explained by a combination of market‐, site‐, and patient‐level factors. Drug‐eluting stents and TAVR, for example, have diffused faster in markets with higher degrees of competition between cardiology practices. 20 , 21 However, prior work has found that even within large, urban health systems where access to care is not geographically limited, Black and White patients may have differing attitudes toward medical innovation. This may be informed by socioeconomic factors and trust in the health care system and may explain differing propensities to accept novel, invasive treatments. 22 , 23 , 24 Further work must be done to identify the causal mechanisms through which novel cardiac technologies diffuse unequally.

Given our model specifications, our results also suggest that the association of race, ethnicity, and SES on LAAO rates depend on zip code–level factors within each specific CBSA. These trends differ from those observed with TAVR, for which a prior analysis by our group was able to rule out neighborhood‐level clustering as being significantly associated with TAVR rates. 9 One potential explanation for this divergence is that LAAO is much less established and may be susceptible to greater local practice variation for management of AF with high bleeding risk. Uncertainty on the use of LAAO persists, because few comparative studies and randomized control trials between LAAO and direct oral anticoagulants have been done. 25 On the other hand, there have been numerous randomized control trials studying the efficacy of TAVR, making it one of the most carefully studied medical devices at the point of introduction into clinical practice. 26 Because this study does not examine clinical indications for LAAO procedures, further work is needed to understand the clinically appropriate levels of LAAO use across population subgroups by way of cohort studies and trials. Nevertheless, we underscore the key finding that even within CBSAs with existing LAAO programs, where local populations should theoretically have ready geographic access to LAAO centers, racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic factors are associated with decreased use of LAAO. Consequently, geographic proximity to LAAO hospitals alone may not ensure equitable access to the procedure.

Such inequities arise because of various factors, including structural racism, social determinants of health, and geographic segregation of groups experiencing disadvantage from advanced medical centers. 27 , 28 , 29 High‐technology procedures may be predisposed to inequitable diffusion among marginalized groups, thereby contributing to racial and ethnic inequities in health care. Racially minoritized communities and groups experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage in metropolitan areas tend to be clustered in neighborhoods with inadequate housing, high unemployment, and reduced access to public resources, thus making it difficult to access high‐tech procedures even if they live in a metro area with a medical center offering such procedures. 30 , 31

In particular, racially and ethnically minoritized patients and patients having lower levels of SES face significant barriers to accessing specialist cardiac care and, consequently, difficulty obtaining referrals for LAAO procedures. 32 , 33 , 34 Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in access to LAAO represent just 1 component of larger disparities in treatment and management of AF among racial and ethnic minority groups. Black and Hispanic patients are less likely to receive rhythm control therapies and have lower quality of AF management. 35 , 36 , 37 One potential solution to improving AF‐related care among racially and ethnically minoritized groups is mobilizing community health workers. In prior studies, community health workers have been effective in reducing coronary heart disease risk and hypertension. 38 , 39 By improving AF‐related health literacy, providing translation services and adherence assistance, and facilitating access to primary and specialist care, community health workers could reduce barriers to access for AF treatment, including LAAO, among marginalized groups.

Of note, Black patients have been shown to have a lower prevalence of AF, which may be because of ancestry‐based differences in paroxysmal patterns of AF and atrial substrate, less intensive screening for AF leading to underdiagnoses, and less opportunity to develop AF because of shorter life expectancy. 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 Although our study does not evaluate the burden of undiagnosed AF among racial and ethnic minority groups, we emphasize the fact that structural inequities in medicine may preclude groups that have been marginalized from accessing the care they need to not only be properly treated for AF but to be diagnosed with AF at all. Moreover, Black patients with AF are still at greater risk for developing stroke, coronary artery disease, and mortality relative to non‐Hispanic White patients and have the highest stroke‐related mortality of any racial group in the United States. 44 , 45 , 46 Therefore, ensuring equitable AF‐related care for Black patients by improving access to specialist care, primary prevention strategies, and cost‐effective hypertension therapies is essential, despite questions about the burden of recognized AF. 35

Our understanding of potential benefits of LAAO among Black patients with complicated AF is constrained by their underrepresentation in both trial populations and the overall population of patients receiving LAAO. Prior research has shown that in landmark LAAO trials, such as the PROTECT‐AF (Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Closure Versus Warfarin for Atrial Fibrillation) and PREVAIL (Prospective Randomized Evaluation of the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure Device in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Versus Long‐Term Warfarin Therapy) trials, Black patients composed 1.3% and 2.2%, respectively, of patients receiving LAAO, despite Black individuals comprising 12.4% of the US population. 45 , 47 Thus, further research is needed to better understand the true nature of barriers to access and specific mechanisms through which disparities arise to determine precise solutions to limited access to LAAO procedures.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, our study considered Medicare fee‐for‐service beneficiaries and may not be generalizable to patients with Medicare Advantage. Second, the use of administrative data impedes a granular understanding of reasons why candidate hospitals were unable to establish LAAO programs, which may include factors such as local market forces, strategic planning decision, and local cardiac specialist expertise. Third, we were unable to evaluate local specialist referral patterns, patient preferences, and patient values, all of which affect patients' ability and desire to undergo LAAO. Despite the reasons underlying adoption of LAAO and varying rates of LAAO, racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic inequities in patient populations with access to LAAO were observed. Such inequities in age‐adjusted rates of LAAO in geographic areas with LAAO centers were also observed. Fourth, the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities observed in rates of LAAO may be interpreted as a gap in quality care for AF, such that racial and ethnic minority groups and groups experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage receive better medical treatment for AF and, therefore, forego LAAO. However, research has shown that individuals with lower levels of SES and from racially and ethnically minoritized groups receive generally worse care for AF. Fifth, given that age is strongly correlated with the prevalence of LAAO, our study is susceptible to some degree of survivor bias because of variations in life expectancy by race and ethnicity. All analyses were age‐adjusted. Sixth, given the observational methods used and the use of administrative data, there may be residual confounding that persists even after controlling for several variables that may be associated with LAAO rates. Seventh, our primary and secondary zip code–level analyses were limited to patients in populous metropolitan areas with LAAO centers. More work is needed to evaluate disparities in access to LAAO in rural areas and the different factors affecting access to LAAO among rural populations. Finally, we selected candidate hospitals based on presence of TAVR and/or ablation programs on site. Although CMS requirements specify that LAAO must be furnished in a hospital with a structural heart disease program and/or electrophysiology program, we felt TAVR and intracardiac ablation would serve as effective proxies to identify all hospitals with capacities to establish LAAO programs.

CONCLUSIONS

Between 2016 and 2019, the growth of LAAO programs in the United States was concentrated to metropolitan areas, and especially metropolitan areas with preexisting programs. Hospitals establishing LAAO programs treated wealthier patient populations than hospitals that did not adopt an LAAO program. Despite this growth of LAAO centers in metropolitan areas, within major metropolitan areas in the United States with LAAO programs, zip codes with larger populations of individuals with low levels of SES and greater proportions of Black and Hispanic patients had lower age‐adjusted rates of LAAO. These findings suggest that although the overall number of LAAO centers has grown, even when geographic proximity to LAAO is not a limitation to access, proximity alone may not ensure equitable access to the procedure. Unequal access may reflect disparities in referral patterns, rates of diagnosis, and propensities to accept novel therapies experienced by racially and ethnically minoritized groups and patients experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

K. Reddy has no disclosures. Dr Nathan has received research funds from Abiomed. Dr Giri has received research funds to the institution from Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Inari Medical, and Recor Medical. He has served on advisory boards for Boston Scientific, Inari Medical, and Astra Zeneca. Dr Kobayashi has received research funds to the institution from Medtronic. He has served on advisory boards for Medtronic. Dr Fanaroff has no disclosures. Dr Fiorilli has received consulting fees and/or honoraria from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Dr Herrmann reports institutional research funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Highlife, Medtronic, and WL Gore, consulting fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Wells Fargo, and WL Gore. Dr Eberly has no disclosures. No other disclosures were reported.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S3

Figures S1–S3

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.122.028032

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

References

- 1. United States Food and Drug Administration . Premarket Approval for Watchman Left Atrial Appendage (LAA) Closure Technology. Last updated February 2, 2022. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=P130013

- 2. Price MJ, Valderrabano M. Left atrial appendage closure to prevent strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2014;130:202–212. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reddy VY, Doshi SK, Kar S, Gibson DN, Price MJ, Huber K, Horton RP, Buchbinder M, Neuzil P, Gordon NT, et al. 5‐year outcomes after left atrial appendage closure: from the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2964–2975. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holmes DR, Alkhouli M, Reddy V. Left atrial appendage occlusion for the unmet clinical needs of stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:864–874. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Furie KL, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in collaboration with the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2019;140:e125–e151. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alkhouli M, Alqahtani F, Holmes DR, Berzingi C. Racial disparities in the utilization and outcomes of structural heart disease interventions in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012125. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kupsky DF, Wang D, Eng M, Gheewala N, Nakhle A, Georgie F, Shah R, Wyman J, Mahan M, Greenbaum A, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in access for watchman device insertion in patients with atrial fibrillation and at elevated risk of bleeding. Structural Heart. 2019;3:144–149. doi: 10.1080/24748706.2019.1569795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glied S, Lleras‐Muney A. Technological innovation and inequality in health. Demography. 2008;45:741–761. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nathan AS, Yang L, Yang N, Eberly LA, Khatana SAM, Dayoub EJ, Vemulapalli S, Julien H, Cohen DJ, Nallamothu BK, et al. Racial, ethnic and socioeconomic inequities in access to transcatheter aortic valve replacement within major metropolitan areas. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;7:150–157. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.4641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Freeman JV, Varosy P, Price MJ, Slotwiner D, Kusumoto FM, Rammohan C, Kavinsky CJ, Turi ZG, Akar J, Koutras C, et al. The NCDR left atrial appendage occlusion registry. JACC. 2020;75:1503–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nathan AS, Yang L, Yang N, Khatana SAM, Dayoub EJ, Eberly LA, Vemulapalli S, Baron SJ, Cohen DJ, Desai ND, et al. Socioeconomic and geographic characteristics of hospitals establishing transcatheter aortic valve replacement programs, 2012‐2018. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14:e008260. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.008260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. United States Office of Management and Budget . Last revised November 22, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.census.gov/programs‐surveys/metro‐micro/about.html

- 13. Dartmouth Atlas Data . 2010‐2017 Zip to Median Household Income Crosswalk Files. 2018. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://atlasdata.dartmouth.edu/folder/list_files/income_crosswalk

- 14. Joynt Maddox KE, Reidhead M, Hu J, Kind AJH, Zaslavsky AM, Nagasako SM, Nerenz DR. Adjusting for social risk factors impacts performance and penalties in the hospital readmissions reduction program. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:327–336. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Economic innovation group . Distressed Communities Index. 2015. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://eig.org/dci

- 16. Stetieh D, Zaidi A, Xu S, Cheung JW, Feldman DN, Reisman M, Mallya S, Paul TK, Singh HS, Bergman G, et al. Racial disparities in access to high volume transcatheter mitral valve repair center. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:862. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(22)01853-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sonel AF, Good CB, Mulgund J, Roe MT, Gibler WB, Smith SC, Cohen MG, Pollack CV, Ohman EM, Peterson ED, et al. Racial variations in treatment and outcomes of black and white patients with high‐risk non‐ST‐elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from CRUSADE (can rapid risk stratification of unstable angina patients suppress adverse outcomes with early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines?). Circulation. 2005;111:1225–1232. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157732.03358.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Casale SN, Auster CJ, Wolf F, Pei Y, Devereux RB. Ethnicity and socioeconomic status influence use of primary angioplasty in patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2007;154:989–993. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brown CP, Ross L, Lopez I, Thornton A, Kiros GE. Disparities in the receipt of cardiac revascularization procedures between blacks and whites: an analysis of secular trends. Ethn Dis. 2008;18:S2‐112–S2‐117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karaca‐Mandic P, Town RJ, Wilcock A. The effect of physician and hospital market structure on medical technology diffusion. Health Serv Res. 2017;52:579–598. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reddy KP, Groeneveld PW, Giri J, Fanaroff AC, Nathan AS. Economic considerations in access to transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Circ: Cardiovascular Interv. 2022;15:e011489. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.011489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Groeneveld PW, Sonnad SS, Lee AK, Asch DA, Shea JE. Racial differences in attitudes toward innovative medical technology. J Gen Inter Med. 2006;21:559–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00453.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heidenreich PA, Shlipak MG, Geppert JD, McClellan M. Racial and sex differences in refusal of coronary angiography. Am J Med. 2002;113:200–207. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01221-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rathore SS, Ordin DL, Krumholz HM. Race and sex differences in the refusal of cardiac catheterization among elderly patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2002;144:1052–1056. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.126122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alkhouli M. Moving the needle forward for more relevant evidence on left atrial appendage occlusion. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2021;14:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Al‐Azizi K, Hamandi M, Mack M. Clinical trials of transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Heart. 2019;105:S6–S9. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baciu A, Negussie Y, Geller A, Weinstein J. The root causes of health inequity. In: Baciu A, Negussie Y, Geller A, Weinstein J, eds. Community Action: Pathways to Health Equity. National Academies Press; 2017. Accessed February 23, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cee GC, Gord CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8:115–132. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Churchwell K, Elking MSV, Benjamin RM, Carson AP, Chang EK, Lawrence W, Mills A, Odom TM, Rodriguez CJ, Rodriguez F, et al. Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e454–e468. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:414–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eberly LA, Day SM, Ashley EA, Jacoby DL, Jeffries JL, Colan SD, Rossano JW, Semsarian C, Pereira AC, Olivotto I, et al. Association of race with disease expression and clinical outcomes among patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:83–91. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cook NL, Ayanian JZ, Orav EJ, Hicks LS. Differences in specialist consultations for cardiovascular disease by race, ethnicity, gender, insurance status, and site of primary care. Circulation. 2009;119:2463–2470. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.825133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eberly LA, Richterman A, Beckett AG, Wispelwey B, Marsh RH, Manchanda ECC, Chang CY, Glynn RJ, Brooks KC, Boxer R, et al. Identification of racial inequities in access to specialized inpatient heart failure care at an academic medical center. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12:e006214. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eberly LA, Garg L, Yang L, Markman TMM, Nathan AS, Eneanya ND, Dixit S, Marchlinski FE, Groeneveld PW, Frankel DS. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in management of incident paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e210247. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sparrow R, Sanjoy S, Choy Y, Elgendy IY, Jneid H, Villablanca PA, Holmes DR, Pershad A, Alraies C, Sposato LA, et al. Racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in patients undergoing left atrial appendage closure. Heart. 2021;0:1–10. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-318650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Golwala H, Jackson LR, Simon DN, Piccini JP, Gersh B, Go AS, Hylek EM, Kowey PR, Mahaffey KW, Thomas L, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in atrial fibrillation symptoms, treatment patterns, and outcomes: insights from outcomes registry for better informed treatment for atrial fibrillation registry. Am Heart J. 2016;174:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Krantz MJ, Coronel SM, Whitley EM, Dale R, Yost J, Estacio RO. Effectiveness of a community health worker cardiovascular risk reduction program in public health and health care settings. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e19–e27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Levine DM, Bone LR, Hill MN, Stallings R, Gelber AC, Barker A, Harris EC, Zeger SL, Felix‐Aaron KL, Clark JM. The effectiveness of a community/academic health center partnership in decreasing the level of blood pressure in an urban African‐American population. Ethn Dis. 2003;13:354–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kamel H, Kleindorfer DO, Bhave PD, Cushman M, Levitan EB, Howard G, Soliman EZ. Rates of atrial fibrillation in black versus white patients with pacemakers. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002492. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ugowe FE, Jackson LR, Thomas KL. Racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence, management, and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:1337–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dewland TA, Olgin JE, Vittinghoff E, Marcus GM. Incident atrial fibrillation among Asians, Hispanics, blacks, and whites. Circulation. 2013;128:2470–2477. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Soliman EZ, Prineas RJ. The paradox of atrial fibrillation in African Americans. J Electrophysiol. 2014;47:804–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Magnani JW, Norby FL, Agarwal SK, Soliman EZ, Chen LY, Loehr LR, Alonso A. Racial differences in atrial fibrillation‐related cardiovascular disease and mortality the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:443–441. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vincent L, Grant J, Ebner B, Potchileev I, Maning J, Olorunfemi O, Olarte N, Colombo R, de Marchena E. Racial disparities in the utilization and in‐hospital outcomes of percutaneous left atrial appendage closure among patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2021;18:987–994. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2021.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Howard G, Peace F, Howard VJ. The contributions of selected diseases to disparities in death rates and years of life lost for racial/ethnic minorities in the United States, 1999‐2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:e129. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. United States Census Bureau . 2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country. Published August 12, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved‐race‐ethnicity‐measures‐reveal‐united‐states‐population‐much‐more‐multiracial.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S3

Figures S1–S3

Data Availability Statement

Data used for this study are covered by a data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Data are not available for distribution by the authors but can be obtained from the CMS with an approved data use agreement.