Abstract

Background

Following myocardial infarction, left ventricular remodeling (LVR) is associated with heart failure and cardiac death. At the same time, left atrial (LA) remodeling (LAR) is an essential part of the outcome of a wide spectrum of cardiac conditions. The authors sought to evaluate the correlates of LAR and its relationships with LVR after myocardial infarction.

Methods and Results

This is a retrospective analysis of 320 of 443 patients enrolled for study of LVR after ST‐elevation myocardial infarction. Left ventricular (LV) volumes, infarct size and LA volume index were assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging during index hospitalization (day 6 [interquartile range, 4–8]) and after a 3‐month follow‐up. LAR was studied using a linear mixed model for repeated measurements. Overall, there was a decrease in LA volume index between 6 days and 3 months (43.9±10.4 mL versus 42.8±11.1 mL, P=0.003). Patients with changes in LA volume index >8% over time were older, with greater body mass index, lower LV ejection fraction, and larger infarct size. Unadjusted predictors of LAR were age older than 70 years, infarct size, anterior infarction, time to reperfusion, history of hypertension, LV end‐diastolic volume, and heart failure at day 6. Independent correlates were age older than 70 years (3.24±1.33, P=0.015) and infarct size (2.16±0.72 per 10% LV, P<0.001). LA remodeling was correlated with LV remodeling (r=0.372, P<0.001), but neither LA nor LV volumes at day 6 were related to LVR or LAR, respectively.

Conclusions

The authors found LA changes to occur in the months after myocardial infarction, with an overall decrease in LA volumes. While LAR coincided with LVR, the correlates for LAR were age older than 70 years and larger infarct size.

Keywords: cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, left atrial remodeling, myocardial infarction

Subject Categories: Myocardial Infarction, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- LA

left atrial

- LAR

left atrial remodeling

- LAVI

left atrial volume index

- LVR

left ventricular remodeling

- VALIANT

Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Left atrial remodeling is a significant feature after myocardial infarction.

Older age and larger infarction appear to be related with left atrial enlargement during follow‐up.

Six‐day left ventricular ejection fraction and left atrial volume index were both independently related to the risk of decompensated heart failure.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Left atrial remodeling may play an independent role toward postinfarction heart failure, notably among patients older than 70 years.

Left ventricular (LV) remodeling (LVR), as a progressive dilation of the left ventricle and decrease in LV ejection fraction, may occur after a myocardial infarction (MI). 1 LVR is more likely in cases of large MI and is related to heart failure (HF) and cardiac death. 2

During LVR, the left atrium—directly connected to the left ventricle—may undergo loss of LV contractile function and acute LV pressure overload. The size of the left atrium is known to be an independent outcome predictor in normal conditions 3 as well as across a wide spectrum of cardiac diseases. 4 Moreover, left atrial (LA) dilation itself has been shown to be related to the probability of developing HF. 5 How the left atrium adapts and remodels after a myocardial injury such as infarction, however, has been poorly described to date.

Through the use of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging, we sought to evaluate the correlates of LA remodeling (LAR) in a large cohort of patients with acute MI and to study its relationship with LVR.

METHODS

The present data are based on a prospective cohort study analyzing the incidence of LVR in 443 patients with ST‐segment–elevation MI (STEMI) (French governmental hospital‐based clinical research program; “Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique” [PHRC], number 2006/0070). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Patients were included from May 2008 to May 2017 in a single tertiary center if they met the following criteria: STEMI within 12 hours of onset of chest pain, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow grade 0 or 1 before percutaneous coronary intervention and successful revascularization with a flow grade 3 after stenting, and written informed consent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: history of MI or coronary bypass grafting; age younger than 18 years; clinical signs of cardiogenic shock; major comorbidities limiting life expectancy; and contraindications for CMR (pacemaker, metallic devices, claustrophobia, or chronic renal insufficiency). The protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the University Hospital of Angers, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and local regulatory requirements. Blinded to CMR data, details of the patients' baseline medical history and clinical presentation were prospectively collected.

Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance

All patients underwent CMR imaging during the index hospitalization (day 6 [interquartile range (IQR), 4–8]) and after a 3‐month follow‐up (day 98 [IQR, 93–105]). CMR was performed using either a 1.5‐ or 3.0 T‐imager (Avanto or Skyra, Siemens) with the application of an 8‐element phased‐array cardiac receiver coil. Cine CMR imaging was performed using the steady‐state free precession sequence in multiple short‐axis and 4‐chamber long‐axis views covering the entire left ventricle. The typical in‐plane resolution applied was 1.2×1.2 mm with a 7‐mm section thickness and no gap (matrix: 155× 288; temporal resolution: 45–50 ms).

Late gadolinium enhancement images were acquired 8 to 10 minutes after administering a dose of 0.2 mmol/kg gadoterate meglumine (Dotarem, Laboratoires Guerbet). Contiguous short‐axis and 4‐chamber long‐axis slices covered the entire ventricle. Typical parameters used were as follows: in‐plane resolution of 1.6×1.6 mm, with a 7‐mm section thickness; echo time 4.66 ms; flip angle 30°; image acquisition triggered at every other heartbeat.

Image Analysis

CMR images were transferred to a workstation for analysis and calculation (Qmass 7.1, Medis). On all short‐axis cine slices, LV endocardial and epicardial borders were outlined manually, on both end‐diastolic and end‐systolic images, excluding the trabeculae and papillary muscles. LV end‐diastolic and end‐systolic volumes, hence, LV mass, were determined. LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was computed. Infarct size was quantified on late gadolinium enhancement images by means of the full width at half maximum method, 6 corresponding to the sum of the hyperenhanced area measured on all sections, given as a percentage of total LV mass. The variability assessment for LV volumes and infarct size, published elsewhere, produced good results. 6

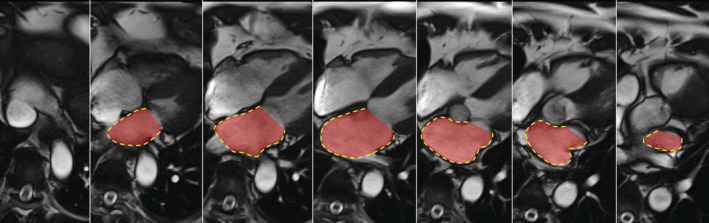

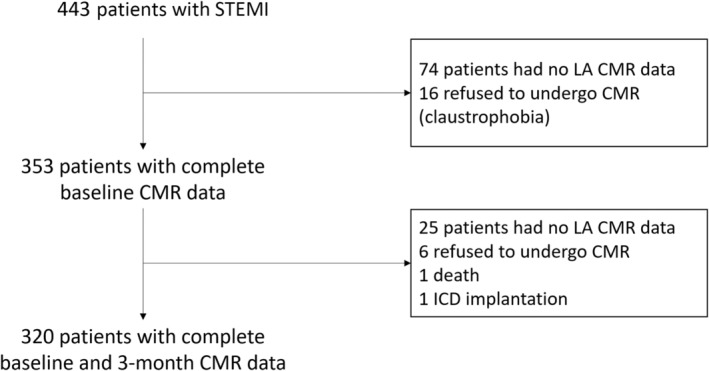

LA maximal volume was assessed using the contiguous 4‐chamber views with manual delineation, at the end of LV systole (Figure 1). Delineation was performed from one side to the other of the mitral annulus, excluding the pulmonary veins and LA appendage. LA volume index (LAVI) was indexed to body surface area. Due to some loss to follow‐up and the retrospective nature of LAVI assessment, LAVI was obtained in 353 patients at day 6 and 320 at 3 months (Figure 2). Incidentally, the 123 excluded patients presented greater infarct size and higher rates of diabetes and HF but no difference in LVR.

Figure 1. Representative image of left atrial volume assessment.

Figure 2. Flow chart of the study population.

CMR indicates cardiac magnetic resonance; ICD, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator; LA, left atrial; and STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as mean±SD or median (IQR) for continuous variables.

First, for descriptive purposes, LAVI change over time was expressed as percentage change and categorized per quartile. Quartile 4 was represented by an increase >8%. Mann–Whitney and Fisher exact tests were used to compare the differences between the groups of continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

A paired Wilcoxon test was used to compare paired data over time. Pearson correlation was used to describe relationships between continuous variables.

As there is no categorical definition for LAR to date, LAR was studied as LAVI changes over time (as a continuous variable). As the different measurements performed on the same patient were inevitably correlated, general linear mixed models allowed us to account for the correlated structure of data when analyzing repeated measurements.

Such linear mixed models allowed us to display the effects of the underlying variables considered (including clinical data, coronary angiogram, and CMR parameters), while simultaneously presenting a random‐effects model.

Cox regression models were run to determine the univariate hazard ratios (HRs) for 6‐day LVEF and 6‐day LAVI to predict decompensated HF during follow‐up.

All tests were performed with a type I error set at 0.05. Analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, version 13.1 (StataCorp LLC).

RESULTS

Baseline Clinical and CMR Characteristics

Patients with a LAVI change >8% were older (60±11.9 years versus 56.7±10.3 years, P=0.020) and had a greater body mass index (28.2±4.2 kg/m2 versus 26.5±3.8 kg/m2, P=0.001). Sex prevalence and cardiovascular risk factors were similar in both groups. Overall, 102 patients (32%) had a history of hypertension (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Population Characteristics at Baseline

| Variable | Total | LAVI change <8% (n=246) | LAVI change >8% (n=74) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometry | ||||

| Men | 224 (84.8%) | 176 (84.2%) | 48 (87.3%) | 0.67 |

| Age, y | 57.5±10.7 | 56.7±10.3 | 60±11.9 | 0.020 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27±4 | 26.5±3.8 | 28.2±4.2 | 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 102 (32%) | 80 (32.7%) | 22 (29.7%) | 0.67 |

| Diabetes | 32 (10%) | 24 (9.8%) | 8 (10.8%) | 0.82 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 177 (55.7%) | 137 (55.9%) | 40 (54.8%) | 0.89 |

| Current smoker | 157 (49.2%) | 127 (51.8%) | 30 (40.5%) | 0.11 |

| STEMI characteristics | ||||

| Anterior infarction | 183 (57.4%) | 139 (56.7%) | 44 (59.5%) | 0.80 |

| Complete revascularization | 219 (68.9%) | 168 (68.6%) | 51 (69.9%) | 0.89 |

| Time to reperfusion, min | 281±187 | 269.6±161 | 319.1±253 | 0.046 |

| In‐hospital HF | 47 (14.8%) | 33 (13.5%) | 14 (18.9%) | 0.26 |

| Thrombolysis | 29 (9.1%) | 23 (9.4%) | 6 (8.1%) | 0.82 |

| Biology | ||||

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 80.7±18.7 | 80.6±18.8 | 80.9±18.3 | 0.89 |

| Creatine kinase peak, IU/L | 2863±2298 | 2686.2±2252.6 | 3513.4±2366.2 | 0.014 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 6.0±1 | 5.9±1 | 5.9±1.1 | 0.97 |

| LDL cholesterol, g/L | 1.39±0.46 | 1.37±0.46 | 1.43±0.44 | 0.37 |

| Triglycerides, g/L | 1.6±1.1 | 1.6±1 | 1.5±1.3 | 0.70 |

| Medical therapy at discharge | ||||

| Aspirin | 307 (96.5%) | 237 (97.1%) | 70 (94.6%) | 0.29 |

| β‐Blockers | 307 (96.5%) | 237 (97.1%) | 70 (94.6%) | 0.29 |

| Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors | 314 (98.7%) | 241 (98.8%) | 73 (98.6%) | 1.00 |

| Vital signs at discharge | ||||

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 119±15 | 120±15 | 117±15 | 0.28 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 71±12 | 72±12 | 69±10 | 0.08 |

| Heart rate (per min) | 69±11 | 68±11 | 72±11 | 0.07 |

Values are expressed as number (percentage) or mean±SD.

BP indicates blood pressure; HF, heart failure; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; and STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Initial MI presentation appeared similar in terms of prevalence of anterior infarction, thrombolysis use, and complete revascularization, but time to reperfusion was greater (319.1±253 minutes versus 269.6±161 minutes, P=0.046).

At discharge, the use of β‐blockers (96.5%) and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (98.7%) was similar between the groups.

Six‐day LVEF was lower (45%±8.9% versus 48.1%±9.1%, P=0.013) and infarct size was greater (13.5%±8.5% versus 11.1%±8.6 %LV, P=0.032) in patients with a LAVI change >8% (Table 2 and Table S1).

Table 2.

CMR Data During Follow‐Up

| Variables | Total | LAVI change <8% (n=246) | LAVI change ≥8% (n=74) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six‐day CMR | ||||

| LVEDV index, mL/m2 | 84±31.3 | 85.9±29.6 | 79.7±36.3 | 0.16 |

| LVESV index, mL/m2 | 44.9±20.6 | 45.1±19.7 | 44.2±23.5 | 0.76 |

| LVEF, % | 47.5±9.2 | 48.1±9.1 | 45±8.9 | 0.013 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 53.4±19.5 | 54.6±18.4 | 49±22.5 | 0.11 |

| Infarct size (% left ventricle) | 11.7±8.6 | 11.1±8.6 | 13.5±8.5 | 0.032 |

| Microvascular obstruction | 119 (47.8%) | 90 (45.7%) | 29 (55.8%) | 0.21 |

| LAVI, mL/m2 | 44±10.5 | 44.4±10.2 | 42.5±10 | 0.17 |

| Three‐month CMR | ||||

| LVEDV index, mL/m2 | 84.7±33.4 | 84.2±31.2* | 86.2±40* | 0.67 |

| LVESV index, mL/m2 | 42.6±22.4* | 41.8±21.4* | 45.1±25.3 | 0.28 |

| LVEF, % | 51.1±10* | 51.6±10* | 48.7±9.5* | 0.049 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 48.2±17.6* | 48.8±16.6* | 45.9±20.6* | 0.24 |

| Infarct size, % LV | 15.2±9.9* | 14.4±9.6* | 18.2±10.3* | 0.012 |

| LAVI, mL/m2 | 42.9±11.2* | 40.2±9.3* | 51.6±12.3* | < 0.001 |

Categorical variables were compared by chi‐square test and the continuous variable by Mann–Whitney tests. CMR indicates cardiac magnetic resonance; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LV, left ventricle; LVEDV, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and LVESV, left ventricular end‐systolic volume.

For P<0.05 for the comparison of 6‐day and 3‐month values by means of paired Wilcoxon tests.

LA Volume

Overall, there was a decrease in LAVI over time (with 44±10.5 mL/m2 versus 42.9±11.2 mL/m2 at day 6 and 3 months, respectively; P=0.003) (Table 2).

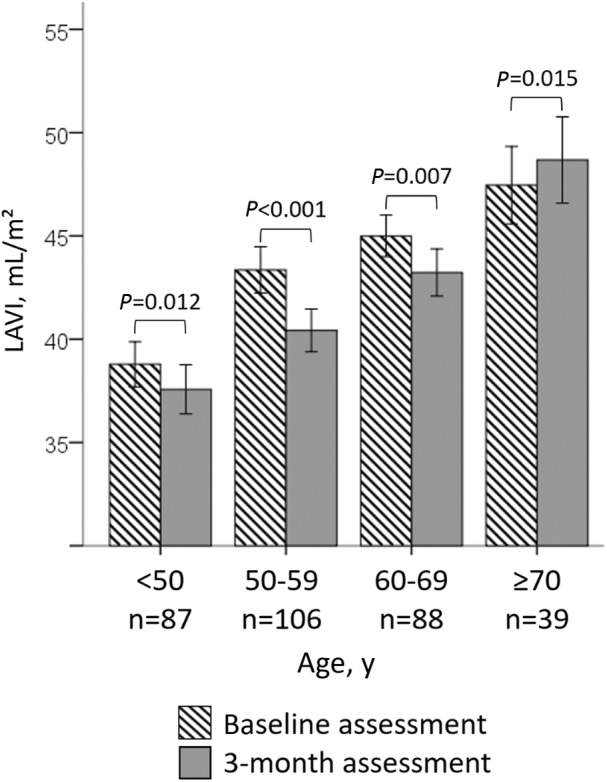

The general linear mixed model for repeated measurements revealed age older than 70 years and infarct size to be the correlates of LAVI change over time. Corresponding estimates were +3.24±1.33 mL/m2 and +2.16±0.72 mL/m2, respectively (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis for Correlates of LAVI Increase Over Time

| Variable | Estimate of LAVI increase, mL/m2 | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age >70 y | 3.24±1.33 | 0.015 |

| Hypertension | −0.90±0.98 | 0.36 |

| Body mass index >30 kg/m2 | 0.80±1.10 | 0.47 |

| Time to reperfusion >360 min | 1.36±1.15 | 0.23 |

| Anterior infarction | 0.38±0.96 | 0.69 |

| In‐hospital HF | 1.19±1.40 | 0.40 |

| Infarct size at day 6 (per 10% left ventricle) | 2.16±0.72 | 0.003 |

| LVEF at day 6 (per 1%) | −0.62±0.37 | 0.095 |

The estimate refers to the difference in mean change in LAVI, given with SD. HF indicates heart failure; LAVI, left atrial volume index; and LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Figure 3. LAVI at 6 days and after 3 months according to age older than 70 years. LAVI indicates left atrial volume index.

LAR and LVR

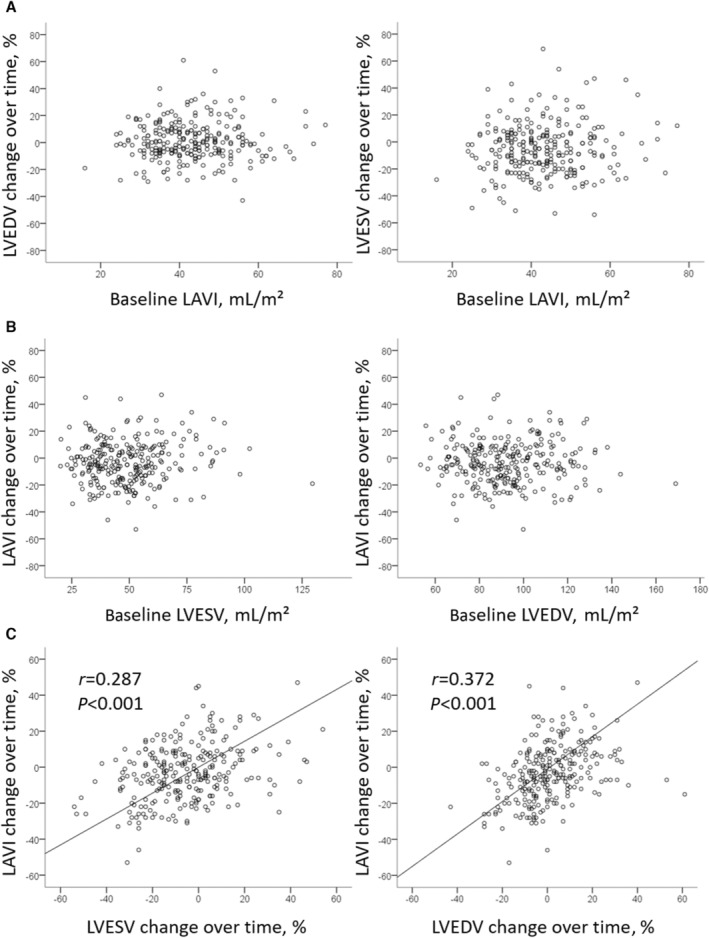

There was a relationship between changes in LAVI and LV volumes over time (Pearson correlation coefficient r=0.372 [P<0.001] for LV end‐diastolic volume and r=0.287 [P<0.001] for LV end‐systolic volume), but there was no relationship between 6‐day LAVI and change in LV volumes over time or 6‐day LV volumes and change in LAVI over time (Figure 4).

Figure 4. LA volume remodeling compared with LVR.

A and B, Show the absence of relationships between 6‐day parameters and LVR and LAR, while panel C shows the connected alteration of LV volumes and LAVI over time. LA indicates left atrial; LAR, left atrial remodeling; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LV, left ventricular; LVEDV indicates left ventricular end‐diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricular end‐systolic volume; and LVR, left ventricular remodeling.

Six‐day LVEF and LAVI were both independently related to the risk of decompensated HF (n=19) during follow‐up, with an HR of 17.544 (95% CI, 5.848–52.632; P<0.001) for LVEF <40% and 4.154 (95% CI, 1.357–12.7210; P=0.013) for LAVI >45 mL/m2.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the major findings were: (1) overall, post‐MI LAR occurred as a global decrease in LAVI over time; (2) older patients and those with a larger infarct size presented adverse LAR during follow‐up; and (3) LAR and LVR were related but were independent from baseline LA or LV volumes and function.

We described an overall decrease in LAVI from 44±10.5 at day 6 to 42.9±11.2 mL/m2 at 3 months (P=0.003). Even though these results were obtained on the largest CMR‐driven post‐STEMI cohort that assessed LAVI, they remain very specific to patients with early and successful reperfusion.

The decrease in LAVI may be a consequence of LV healing over time. While post‐MI immediate pressure overload may lead to acute LA dilation, myocardial functional recovery usually occurs in the months following MI. 7 In that respect, structures that are connected with the left ventricle may recover as well. The present study and the body of evidence on LAR 8 , 9 , 10 suggest considering post‐MI healing at the cardiac level rather than focusing on the left ventricle alone. Moreover, β‐blockers and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors are now broadly given and may play a role in LAR. For instance, Kokubo et al showed that angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors preserve LA reservoir function and consequently LA enlargement in patients with hypertension. 11

Nevertheless, our results differ from reports that previously described the alteration of LA volumes after MI. Contrary to our observational cohort, which was set up to study post‐MI LVR, these reports were issued from randomized controlled trials implying various drugs. 8 , 9 , 10 Kyhl et al showed LAVI to increase from 48.3 mL/m2 (IQR, 41.8–54.1) at day 6 to 49.8 mL/m2 (IQR, 40.4–57.2) 3 months after STEMI (P=0.014) in a cohort of 160 CMR‐assessed patients. 10 Considering these patients presented with greater 6‐day LAVI, older age (mean age of 60.6±10.4 years), and adverse prognosis (23% of cardiovascular outcomes), they may relate to patients with more severe cases, such as the one with the highest quartile of LAVI change in our study.

More data were obtained by echocardiography studies. The first report detailing LA dilation over time was obtained by assessing LA surface area. 12 In 2008, the VALIANT (Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction) echocardiography study, 8 which involved patients with high‐risk MI associated with in‐hospital HF and/or LV dysfunction, showed a mean increase in LAVI of 3.00±7.08 mL/m2 at 20 months. Similarly, Bakkestrom et al studied 66 patients with acute MI and described an increase in LAVI from 38±6 mL/m2 at day 6 to 48±11 mL/m2 after 4 months, which was related to midregional pro‐atrial natriuretic peptide but surprisingly not with rest and exercise pulmonary pressures. 9 Again, these patients appeared to be much older (mean age of 62±8 years) and were included because of preexisting diastolic dysfunction.

While LA enlargement was described as an independent predictor of all‐cause mortality, reinfarction, and hospitalization for HF after STEMI, 8 , 13 , 14 the present data show that patients with a larger infarction and age older than 70 years will show additive LA dilation during follow‐up.

The left atrium is a major contributor to LV filling, notably by means of its conduit and booster pump functions. 15 , 16 These functions may be altered by myocardial injury. Indeed, acute MI compromises both LV systolic and diastolic function. To some extent, such acute hemodynamic changes lead to an immediate increase in LA filling pressure and secondary LA volume overload. Similar to our results, larger infarct size, greater troponin peak, and depressed LVEF—which correspond to severe forms of STEMI—were correlated with LAR. 10 The novelty of our report is to identify older age (>70 years) as being related to LAR, as 6‐day LAVI and change in LAVI over time differed with regard to age (Figure 3). LA enlargement with age was broadly described 17 and recognized as a risk marker for the development of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and HF. 18

LAR and LVR were strongly related (Figure 4), as they might share similar pathophysiology with increased pressure overload and wall shear stress leading to cavity dilation. In the post‐MI condition, while a simultaneous and parallel process may be hypothesized, it is more likely that LVR causes LAR. Indeed, depressed LV function at day 6 has been described as predicting LAR in populations with severe MI. 8 , 10 For instance, the main biomarker for LVR remains the extent of infarct size, 19 just as reported here and by others 10 for LAR. The effect of advanced age on LVR remains more controversial. 20 Finally, the association between microvascular obstruction and LAR was anticipated but not encountered in our study, perhaps because of a lack of power, especially in models including infarct size. 21

Limitations

Our study has limitations inherent to current CMR procedures and retrospective analyses. First, we lack some LA CMR data when planes were missing (Figure 1). As a result, excluded patients (n=123) appeared more severely afflicted, and it is likely that in a higher‐risk population, the magnitude of our findings would be greater. Similarly, baseline CMR was performed relatively late on, considering that some cardiac remodeling may occur during the first days, including LA volume. 12 Second, despite the recent resurgence of interest in the assessment of LA function and longitudinal volumetric measurements, Doppler and LA strain analysis were not studied. 16 We did not quantify LA fibrosis because of the need for dedicated CMR sequences. 22 This is an important point when studying remodeling processes over time. Furthermore, biomarkers such as the brain natriuretic peptide might be of interest in future research in corroborating LAR significance. Finally, our study lacked echocardiographic data to correlate our results with the presence of mitral regurgitation.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study described the natural course of LA volume over time in a large cohort of patients with STEMI, showing an overall decrease in LAVI. We also identified several conditions in which reverse remodeling did not occur, namely older age and larger infarction. LA remodeling appeared to be strongly connected to LV remodeling. Future research would do well to study the impact of and relationship between LA and LV remodeling with their clinical outcomes.

Sources of Funding

The study was funded by the French governmental hospital‐based clinical research program (PHRC number 2006/0070) and the University Hospital of Angers (France).

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supporting information

Table S1

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.122.026048

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 7.

References

- 1. Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling—concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:569–582. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00630-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gaudron P, Kugler I, Hu K, Bauer W, Eilles C, Ertl G. Time course of cardiac structural, functional and electrical changes in asymptomatic patients after myocardial infarction: their inter‐relation and prognostic impact. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:33–40. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01319-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khan MA, Yang EY, Zhan Y, Judd RM, Chan W, Nabi F, Heitner JF, Kim RJ, Klem I, Nagueh SF, et al. Association of left atrial volume index and all‐cause mortality in patients referred for routine cardiovascular magnetic resonance: a multicenter study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2019;21:4. doi: 10.1186/s12968-018-0517-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abhayaratna WP, Seward JB, Appleton CP, Douglas PS, Oh JK, Tajik AJ, Tsang TS. Left atrial size: physiologic determinants and clinical applications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2357–2363. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Takemoto Y, Barnes ME, Seward JB, Lester SJ, Appleton CA, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Tsang TSM. Usefulness of left atrial volume in predicting first congestive heart failure in patients > or =65 years of age with well‐preserved left ventricular systolic function. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:832–836. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bière L, Audonnet M, Clerfond G, Delagarde H, Willoteaux S, Prunier F, Furber A. First pass perfusion imaging to improve the assessment of left ventricular thrombus following a myocardial infarction. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:1532–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dall'Armellina E, Karia N, Lindsay AC, Karamitsos TD, Ferreira V, Robson MD, Kellman P, Francis JM, Forfar C, Prendergast BD, et al. Dynamic changes of edema and late gadolinium enhancement after acute myocardial infarction and their relationship to functional recovery and salvage index. Circulation. 2011;4:228–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meris A, Amigoni M, Uno H, Thune JJ, Verma A, Kober L, Bourgoun M, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, Maggioni AP, et al. Left atrial remodelling in patients with myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both: the VALIANT Echo study. Eur Heart J. 2008;30:56–65. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bakkestrøm R, Andersen MJ, Ersbøll M, Bro‐Jeppesen J, Gustafsson F, Køber L, Hassager C, Møller JE. Early changes in left atrial volume after acute myocardial infarction. Relation to invasive hemodynamics at rest and during exercise. Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kyhl K, Vejlstrup N, Lønborg J, Treiman M, Ahtarovski KA, Helqvist S, Kelbæk H, Holmvang L, Jørgensen E, Saunamäki K, et al. Predictors and prognostic value of left atrial remodelling after acute myocardial infarction. Open Heart. 2015;2:e000223. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kokubu N, Yuda S, Tsuchihashi K, Hashimoto A, Nakata T, Miura T, Ura N, Nagao K, Tsuzuki M, Wakabayashi C, et al. Noninvasive assessment of left atrial function by strain rate imaging in patients with hypertension: a possible beneficial effect of renin‐angiotensin system inhibition on left atrial function. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:13–21. doi: 10.1291/hypres.30.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Popescu BA, Macor F, Antonini‐Canterin F, Giannuzzi P, Temporelli PL, Bosimini E, Gentile F, Maggioni AP, Tavazzi L, Piazza R, et al. Left atrium remodeling after acute myocardial infarction (results of the GISSI‐3 Echo substudy). Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1156–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lønborg JT, Engstrøm T, Møller JE, Ahtarovski KA, Kelbæk H, Holmvang L, Jørgensen E, Helqvist S, Saunamäki K, Søholm H, et al. Left atrial volume and function in patients following ST elevation myocardial infarction and the association with clinical outcome: a cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14:118–127. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Antoni ML, ten Brinke EA, Atary JZ, Marsan NA, Holman ER, Schalij MJ, Bax JJ, Delgado V. Left atrial strain is related to adverse events in patients after acute myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2011;97:1332–1337. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2011.227678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carluccio E, Biagioli P, Mengoni A, Francesca Cerasa M, Lauciello R, Zuchi C, Bardelli G, Alunni G, Coiro S, Gronda EG, et al. Left atrial reservoir function and outcome in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the importance of atrial strain by speckle tracking echocardiography. Circulation. 2011;11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.118.007696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoit BD. Left atrial size and function: role in prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:493–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pritchett AM, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ, Karon BL, Redfield MM. Diastolic dysfunction and left atrial volume: a population‐based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kotecha D, Lam CSP, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Van Gelder IC, Voors AA, Rienstra M. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation: vicious twins. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2217–2228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bière L, Donal E, Jacquier A, Croisille P, Genée O, Christiaens L, Prunier F, Gueret P, Boyer L, Furber A. A new look at left ventricular remodeling definition by cardiac imaging. Int J Cardiol. 2016;209:17–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ennezat PV, Lamblin N, Mouquet F, Tricot O, Quandalle P, Aumegeat V, Equine O, Nugue O, Segrestin B, de Groote P, et al. The effect of ageing on cardiac remodelling and hospitalization for heart failure after an inaugural anterior myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1992–1999. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reinstadler SJ, Metzler B, Klug G. Microvascular obstruction and diastolic dysfunction after STEMI: an important link? Int J Cardiol. 2020;301:40–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.10.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Quail M, Grunseich K, Baldassarre LA, Mojibian H, Marieb MA, Cornfeld D, Soufer A, Sinusas AJ, Peters DC. Prognostic and functional implications of left atrial late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2019;21:2. doi: 10.1186/s12968-018-0514-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1