Abstract

Background

Gastric cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death in the world. It is increasingly evident that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) transcribed from the genome-wide association studies (GWAS)-identified gastric cancer risk loci act as a key mode of cancer development and disease progression. However, the biological significance of lncRNAs at most cancer risk loci remain poorly understood.

Methods

The biological functions of LINC00240 in gastric cancer were investigated through a series of biochemical assays. Clinical implications of LINC00240 were examined in tissues from gastric cancer patients.

Results

In the present study, we identified LINC00240, which is transcribed from the 6p22.1 gastric cancer risk locus, functioning as a novel oncogene. LINC00240 exhibits the noticeably higher expression in gastric cancer specimens compared with normal tissues and its high expression levels are associated with worse survival of patients. Consistently, LINC00240 promotes malignant proliferation, migration and metastasis of gastric cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, LINC00240 could interact and stabilize oncoprotein DDX21 via eliminating its ubiquitination by its novel deubiquitinating enzyme USP10, which, thereby, promote gastric cancer progression.

Conclusions

Taken together, our data uncovered a new paradigm on how lncRNAs control protein deubiquitylation via intensifying interactions between the target protein and its deubiquitinase. These findings highlight the potentials of lncRNAs as innovative therapeutic targets and thus lay the ground work for clinical translation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13046-023-02654-9.

Keywords: LINC00240, DDX21, USP10, Gastric cancer, Ubiquitination

Introduction

Gastric cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death in the world, with an estimated 769,000 deaths (7.7% of the total cancer deaths) according to the GLOBOCAN estimates in 2020 [1]. Incidence rates in Eastern Asia and Eastern Europe are generally high, whereas rates are low in Northern America and Northern Europe [1]. Established environmental risk factors of gastric cancer include Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), alcohol consumption, tobacco smoking, foods preserved by salting, and low fruit intakes [1, 2]. Chronic H. pylori infection is the main cause of gastric cancer [1, 2]. The prevalence of H. pylori infection is extremely high, infecting about half of the world's population [1, 3]. However, only less than 5% of infected hosts will develop gastric cancer, indicating that other factors, especially differences in host genetics, may be crucial during tumorigenesis of stomach.

Multiple genetic loci have been significantly associated with gastric cancer risk via genome-wide association studies (GWASs) [4–14]. However, only a few of gastric cancer-susceptibility genes in these risk loci have been functionally verified [4, 6, 9, 13, 15]. Multiple studies elucidated that long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are transcribed from cancer risk genetic loci and contribute to tumorigenesis [15–21]. For instance, we previously reported that lncPSCA in 8q24.3 is a novel tumor suppressive gene [15]. LncPSCA remarkably inhibits malignant behaviors of gastric cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncoprotein DDX5 has been identified as the interacting protein of lncPSCA. Interestingly, lncPSCA could accelerate degradation of DDX5 via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Decreased levels of DDX5 results in less RNA polymerase II (Pol II) binding with DDX5 as well as transcriptional activation of multiple P53 signaling tumor suppressors by Pol II [15]. However, the role of lncRNAs transcribed from genome intervals around other gastric cancer risk signals in development and progression of gastric cancer are still largely unclear.

In the current study, we systematically investigated three candidate lncRNAs (LINC00240, LINC01012 and ZNRD1-AS1) transcribed from the 6p22.1 risk locus. Only LINC00240 exhibits the noticeably higher expression in gastric cancer specimens compared with normal tissues and its high expression levels are associated with worse survival of gastric cancer patients. Consistently, LINC00240 promotes malignant proliferation, migration and metastasis of gastric cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, LINC00240 could interact and stabilize oncoprotein DDX21 via eliminating its ubiquitination by its novel deubiquitinating enzyme USP10, which, thereby, promote progression of gastric cancer.

Material and methods

Patients and tissue specimens

There are two gastric cancer patient cohorts (Discovery cohort and Validation cohort) which were enrolled in the current study. The detailed characteristics of all patients of Discovery cohort (n = 96) or Validation cohort (n = 30) from have been described previously. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute. At recruitment, the written informed consent was obtained from each subject. The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from tissue specimens or culture cells with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) as previously reported [15, 22]. Each RNA sample was then reverse transcribed into cDNAs using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (TaKaRa, Japan). cDNA and appropriate primers (Supplementary Table 1) were plated in a 96-well plate and gene expression levels were measured using TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa, RR820A). The expression of candidate lncRNAs or genes was calculated by using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Each sample was measured in triplicate and specificity of PCR products was validated by the melting-curve.

Cell culture

Human gastric cancer MKN-45, MKN-28, and BGC-823 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, USA). Human HGC-27, GES-1, MGC80-3 and HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco, USA). Human gastric cancer AGS cells were cultured in Ham's F-12 K medium (Gibco, USA). HGC-27, MGC80-3, MKN-45, and HEK293T cells were kindly provided by Dr. Yunshan Wang (Jinan Central Hospital, Shandong Province, China). GES-1, MKN-28, AGS, and BGC-823 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Jie chai (Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute, Shandong Province, China). All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator and periodically tested mycoplasma negative.

The expression and shRNA constructs and transient transfection

The human full-length LINC00240 (NR_026775.2) cDNA and truncated versions of LINC00240 cDNA were directly synthesized and cloned after the CMV promoter of pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro. The full-length LINC00240 cDNA plasmid was named as LINC00240. After one HA-tag sequence was inserted after ATG of the CDS region of DDX21 (NM_004728.4), the cDNA was cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector to generate the HA-tagged DDX21 plasmid (WT). Five truncated DDX21 plasmids (ΔDEADc, Δ1-398, Δ617-783, ΔGUCT, and ΔAdoMet) were mutants of the HA-tagged DDX21 plasmid with CDS region after deletion of the DEADc domain, 1-398aa, 329-1283aa, the GUCT domain, or the AdoMet domain, separately. Two shRNA hairpins targeting human LINC00240 (sh240-1 or sh240-2) or the control shRNA (Supplementary Table 2) were cloned into the pLKO.1 vector. The resultant plasmids were designated sh240-1, sh240-2, or shNC. All the plasmids were synthesized by Genewiz (Suzhou, China) and sequenced to confirm the orientation and integrity. Transient transfection of plasmid constructs or small interfering RNAs (GenePharma, Shanghai, China) (Supplementary Table 2) was performed with Lipofectamine 3000 or the INTERFERin reagent (Polyplus, 409–10).

Lentiviral transduction

As previously reported, recombinant lentiviral particles were produced by transient co-transfection of the sh240-1, sh240-2, or LINC00240 plasmids into HEK293T cells [23]. After transfection for 48 h and 72 h, the viral supernatants containing the recombinant lentiviral particles of LINC00240, sh240-1, sh240-2 or their controls (NC or shNC) were collected and filtered. Gastric cancer HGC-27 and MGC80-3 cells were infected with the viral supernatants containing 8 μg/mL polybrene. Stably LINC00240-overexpression (OE) cells were selected using 2 μg/mL puromycin. Stably LINC00240-knockdown (KD) gastric cancer cells were selected using 10 μg/mL blasticidin. In these lentiviral transducted cells, the expression levels of LINC00240 were examined by RT-qPCR.

Cell proliferation and colony formation analyses

For cell proliferation assays, a total of 3 × 104 gastric cancer HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells with stable overexpression of LINC00240 or silencing of LINC00240 were seeded in 12-well plates. Cells were harvested and counted at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h after seeding. For the rescue assays, siRNAs of DDX21 or NC RNA (Genepharma, China) (Supplementary Table 2) were transfected to the stably LINC00240-OE HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells, whereas the HA-tag DDX21 expression construct or the pcDNA3.1 vector were transfected to the stably LINC00240-KD cells. For colony formation assays, a total of 1,000 gastric cancer cells per well were seeded in 6-well plates. When colonies were visible after 14 days, cells were washed with cold PBS twice and fixed with the fixation fluid (methanol:acetic acid = 3:1). After the gastric cancer cells were dyed using crystal violet, colony number in each well was counted.

Xenograft studies

To examine the in vivo role of LINC00240, we inoculated subcutaneously a total of 6 × 106 stably LINC00240-OE, LINC00240-KD or control HGC-27 cells into fossa axillaries of five-week-old female nude BALB/c mice (Vital River Laboratory, Beijing, China). Tumor growth was measured every two days as previously described [15, 23]. To assess functions of LINC00240 during gastric cancer metastases in vivo, we injected a total of 2 × 106 HGC-27 cells with stable LINC00240-KD (shNC, sh240-1, or sh240-2) or LINC00240-OE (NC or LINC00240) into tail vein of 5-week-old female nude BALB/c mice (Vital River Laboratory, Beijing, China) (n = 3 per group). Mouse lungs with metastatic tumors were formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining was performed in mouse livers with an antibody specific for vimentin as previously reported [24, 25]. All procedures involving mice were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute. All analyses were performed in a blinded fashion with individuals unaware of xenograft types.

Wound healing and transwell assays

In wound healing assays, a wound was scratched by a 10 μL pipette tip when the cell layer of gastric cancer cells with lentiviral transduction of overexpressed LINC00240 or the LINC00240 shRNAs reached about 90% confluence. Cells were continued cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and the average extent of wound closure was quantified. For transwell assays, gastric cancer cells were added to upper transwell chambers (pore 8 μm, Corning) after transwell chambers were coated with BD Biosciences Matrigel (1:20 dilution) for 12 h. Culture medium containing 10% FBS was added to the lower wells. After 48 h, gastric cancer cells migrated to the lower wells through pores were stained with 0.2% crystal violet solution and counted.

Subcellular fractionation

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the cytosolic and nuclear fractions of gastric cancer HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells were separately isolated using the nuclear/cytoplasmic Isolation Kit (Biovision, K266, China). The relative RNA levels of LINC00240 in cytosolic or nuclear fractions were detected by RT-qPCR.

RNA pulldown

The RNA pulldown assays were performed to identify proteins interacting with LINC00240 as reported previously [15, 23]. To prepare the DNA template for in vitro RNA synthesis, LINC00240 was subcloned into pcDNA3.1 with inserted T7 promoter before and after the cloning site. In briefs, LINC00240 RNAs were transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase (MEGAscript T7 Transcript Kit, Thermo fisher, AM1330) and the linearized LINC00240 construct. After purified with the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, #74,104, Germany), the sense and antisense LINC00240 RNAs were biotinylated with Pierce™ RNA 3' End Desthiobiotinylation Kit (Thermo fisher, 20,163). These RNAs were then incubated with MGC80-3 protein extracts at 4 °C for 1 h. Proteins bound on the streptavidin magnetic beads were recovered with Elution Buffer following the instruction of Pierce™ Magnetic RNA–Protein Pull-Down Kit (Thermo, 20,164, USA). The retrieved proteins were then analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LS-MS/MS) (Hoogen Biotech Co., Shanghai, China) and Western Blot. Mass spectra were analyzed using MaxQuant software (version 1.5.3.30) with the UniProtKB human database (Uniport Homo sapiens 188441_20200326).

RNA immunoprecipitation (RNA-IP)

As reported previously, RNA-IP assays were performed with the DDX21 antibody or the IgG Isotype-control [15, 23]. The protein-RNA complexes were recovered by Dynabeads® Protein G beads (Thermo, 10003D, USA). LINC00240 RNA levels in the precipitates were measured by RT-qPCR. A total of 10% of inputs were used for RT-qPCR.

Western blot

Western blot was performed following the standard protocol as previously described [15, 23]. In brief, after separated with SDS-PAGE gel, total cellular proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, ISEQ00010, USA). The PVDF membrane was then incubated overnight at 4 °C with various antibodies (Supplementary Table 3). The ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Pierce, 32,106) was used to visualize target proteins.

Turnover assays

The stably LINC00240-OE, LINC00240-KD or control HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells were seeded into 6-well plates and then cultured for 24 h. Cycloheximide (CHX) (Merck, # 66–81-9, US) at a final concentration of 200 μg/mL was added to the cells to stop de novo protein synthesis. The HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells were harvested at the indicated times after CHX treatments. Western blot was performed to measure the DDX21 and GAPDH protein levels in HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells.

Ubiquitination assays

As reported previously, gastric cancer cells were firstly transfected with the pcDNA3.1-HA-ubiquitin (HA-ubi) plasmid [15, 23]. At 36 h after transfection, MG132 at a final concentration of 50 μg/mL was added to the cells and incubated for 6 h. To isolate ubiquitinated DDX21, proteins in the cell lysate were immunoprecipitated with anti-DDX21 antibody and then detected with the anti-HA antibody by Western blot.

Statistics

Student’s t test was used for calculation of the difference between two groups. Impacts of LINC00240 expression on gastric cancer patients’ survival were tested by Kaplan–Meier plots and survival durations were analyzed using the log-rank test. A P value of less than 0.05 was used as the criterion of statistical significance. All analyses were performed with SPSS software package (Version 16.0, SPSS Inc.) or GraphPad Prism (Version 8.0, GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Results

Increased expression of LINC00240 at chromosome 6p22.1 locus in gastric cancer tissues was associated with shortened survival time of patients

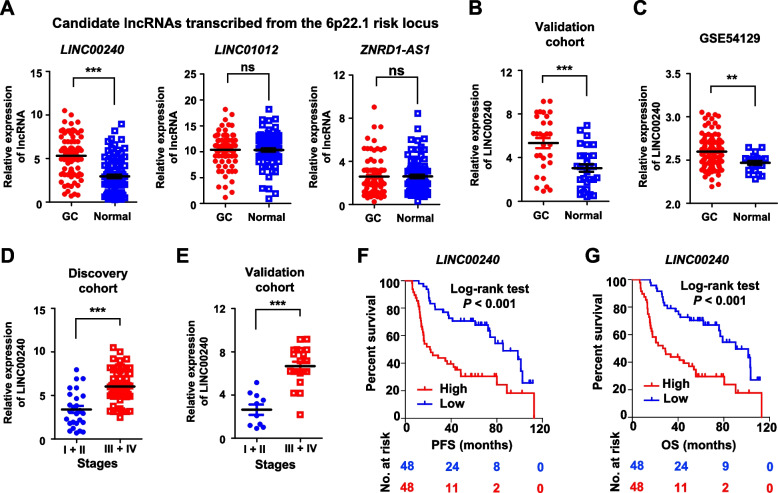

To examine whether lncRNAs transcribed from the chromosome 6p22.1 risk locus contribute to gastric cancer development, we firstly measured levels of three candidate lncRNAs (LINC00240, LINC01012, and ZNRD1-AS1) in paired gastric cancer specimens and normal tissues of Discovery cohort (n = 96) (Fig. 1A). We found that only LINC00240 showed evidently elevated expression in malignant tissues compared to normal stomach specimens (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1A). In line with this, we found markedly increased levels of LINC00240 in gastric cancer specimens of Validation cohort (n = 30) (both P < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). In support of this notion, significantly increased LINC00240 expression in cancerous specimens was observed compared to normal tissues in another gastric cancer cohort from China (GSE54129) (P < 0.01). There was remarkably elevated expression of LINC00240 in patients with advanced stage diseases compared to cases with early-stage diseases (Fig. 1D and E). Importantly, LINC00240 levels were significantly associated with progression-free survival (PFS) (log-rank P < 0.001; Cox regression P = 3.9 × 10–4) and overall survival (OS) in gastric cancer patients of Discovery cohort (log-rank P < 0.001; Cox regression P = 2.6 × 10–4) (Fig. 1F and G). Patients with lower LINC00240 expression had prolonged time of PFS or OS compared to ones with high LINC00240 levels (Fig. 1F and G), suggesting that LINC00240 might be involve in gastric cancer progression as a novel oncogene.

Fig. 1.

LINC00240 is a significantly elevated lncRNA in gastric cancer specimens and associated with shortened survival time of patients. A Relative expression of three candidate lncRNAs transcribed from the 6p22.1 risk locus (LINC00240, LINC01012, and ZNRD1-AS1) in paired gastric cancer specimens and normal tissues of Discovery cohort (n = 96). B, C Significantly upregulated expression of LINC00240 in gastric cancer specimens of Validation cohort (n = 30) and another Chinese gastric cancer cohort (GSE54129) compared to normal tissues. D, E In Discovery cohort and Validation cohort, there were much higher LINC00240 expression levels in cancerous tissues from gastric cancer patients with high-grade diseases compared to malignant tissues from patients with low-grade diseases. F, G The gastric cancer patients with higher LINC00240 expression had a shorter PFS or OS compared to patients with lower LINC00240 expression (Discovery cohort). Data are shown as mean ± SD. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test (A, B), or by unpaired Student’s t test (C, D, E). ns: not significant. Log-rank test was used for survival comparison (F, G)

LINC00240 enhanced malignant proliferation of gastric cancer cells in vitro and in vivo

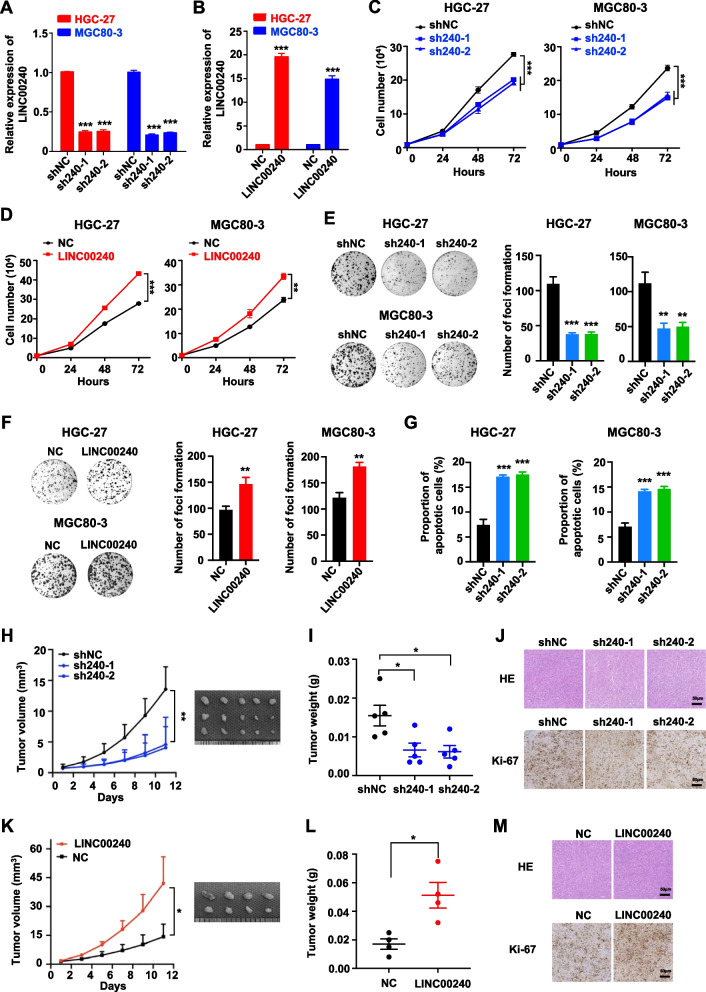

We next examined the involvement of LINC00240 in gastric cancer development in vitro and in vivo. We firstly examined levels of LINC00240 in human GES-1, MKN-28, MKN-45, AGS, BGC-823, HGC-27 and MGC-803 cell lines. Evidently higher LINC00240 expression levels in gastric cancer cells (MKN-28, MKN-45, AGS, BGC-823, HGC-27 and MGC-803) were observed than that in normal human GES-1 cells (all P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, there were no obvious LINC00240 expression differences among various gastric cancer cell lines. Therefore, we chose HGC-27 and MGC-803 cell lines to explore the role of LINC00240. Multiple gastric cancer cell lines were then generated via stably silencing of LINC00240 by shRNAs or forced-expressing the lncRNA by the LINC00240 plasmid. These gastric cancer cells successfully transduced by lentivirus were selected by blasticidin or puromycin. In HGC-27 and MGC80-3 cells stably expressing LINC00240 shRNAs, there was significantly decreased expression of the lncRNA (shL240-1 or shL240-2 vs. shNC: all P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). Strikingly over-expressed LINC00240 was found in HGC-27 and MGC80-3 cells stalely expressing the LINC00240 construct (LINC00240 vs. NC: both P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). As shown in Fig. 2C and D, silencing of LINC00240 significantly inhibited proliferation of HGC-27 and MGC80-3 cells (all P < 0.001); whereas, ectopic LINC00240 expression markedly promoted viability of gastric cancer cells (both P < 0.01). Consistently, knocking-down expression of LINC00240 suppressed clone formation of HGC-27 and MGC80-3 cells (all P < 0.01) (Fig. 2E). Gastric cancer cells with overexpressed LINC00240 showed reinforced clonogenicity (both P < 0.01) (Fig. 2F). Moreover, silencing of LINC00240 significantly promoted apoptosis of gastric cancer cells, but did not impact cell cycle of gastric cancer cells (Fig. 2G and Supplementary Fig. 2). Together, these data elucidated the oncogenic functions of LINC00240 in gastric cancer.

Fig. 2.

LINC00240 promotes malignant proliferation of gastric cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. A, B Relative expression of LINC00240 in HGC-27 and MGC80-3 gastric cancer cell lines with stably silenced LINC00240 (shL240-1 or shL240-2) or with stably forced-expressed LINC00240 (LINC00240). C Silencing of LINC00240 significantly repressed viability of HGC-27 and MGC80-3 cells. D Overexpression of LINC00240 significantly promoted proliferation of gastric cancer cells. E, F In colony formation assays, silencing of LINC00240 markedly inhibited clone formation of HGC-27 and MGC80-3 cells. Overexpressed LINC00240 remarkably increased clonogenicity of gastric cancer cells. G Silencing of LINC00240 significantly promoted apoptosis of gastric cancer cells. H-J Evidently decreased growth and tumor weights of the HGC-27 xenografts with stably depleted LINC00240 were observed compared to the controls. K-M The xenografts stably over-expressing LINC00240 grew much faster and showed an obvious increase in tumor weight compared to the control xenografts. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by unpaired Student’s t test (A-J)

We then assessed the in vivo role of LINC00240 using gastric cancer xenografts. Importantly, stable silencing of LINC00240 evidently inhibited growth of the gastric cancer xenografts compared to the controls (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2H-J). On the contrary, xenografts stably over-expressing LINC00240 grew much faster and showed an evident increase in tumor volume and tumor weight compared to the control xenografts (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2K-M). In addition, we also detected expression levels of multiple apoptotic proteins (BAX, BAK and BCL-2) in gastric cancer xenografts, which indicated the pro-apoptotic of LINC00240 (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Collectively, these results suggested that LINC00240 could promote malignant proliferation of gastric cancer in vivo.

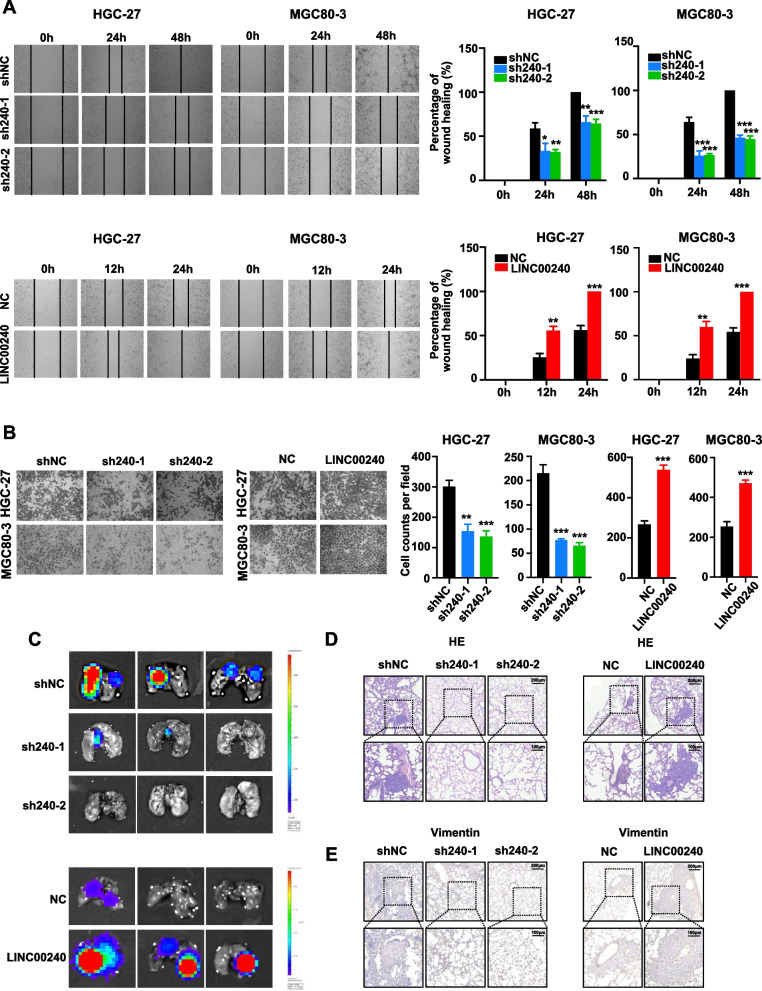

LINC00240 improved invasive activities of gastric cancer cells

We next investigated if LINC00240 influences the migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells (Fig. 3). The wound-healing assays were performed to determine the impact of LINC00240 on mobility of gastric cancer cells. Stable LINC00240-KD significantly impaired HGC-27 cell motility, whereas stabilized LINC00240-OE accelerated migration capability of gastric cancer HGC-27 cells. In line with this observation, silencing of LINC00240 evidently weakened gastric cancer MGC80-3 cell migration and forced-expressed LINC00240 promoted motility capability of MGC80-3 cells (Fig. 3A). The Matrigel invasion assays elucidated that stably silenced LINC00240 could reduce invasion of gastric cancer cells. In contrast, increased invasion capability of gastric cancer cells was observed after ectopic LINC00240 expression (Fig. 3B). We then examined if LINC00240 could regulate metastasis of gastric cancer cells in vivo. To establish metastasis mice models, stably LINC00240-KD HGC-27 cells, stably LINC00240-OE cells or NC cells were injected into the tail vein of mice. We found that LINC00240-depletion inhibited lung metastasis of gastric cancer cells; whereas, stabilized LINC00240 overexpression obviously enhanced gastric cancer lung metastases (Fig. 3C). HE staining and vimentin IHC further confirmed the effect of LINC00240 expression on metastasis of gastric cancer cells in vivo (Fig. 3D and E). These results indicated that LINC00240 enhances migration and invasion capability of gastric cancer cells.

Fig. 3.

LINC00240 enhances migration and invasion capabilities of gastric cancer cells. A In HGC-27 and MGC80-3 gastric cancer cells, LINC00240-knockdown inhibited wound-healing and the stably enforced LINC00240 expression accelerated wound-healing. The lines are the edges of cell layers. B LINC00240-knockdown reduced invasion of gastric cancer cells. Overexpression of LINC00240 promoted invasion abilities of HGC-27 and MGC80-3 cells. C Representative fluorescent images of metastatic tumors in lungs of nude mice. D Representative images of HE slides of lung metastases. E Representative images of IHC staining showing the expression of Vimentin within lung metastases. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by unpaired Student’s t test (A-F)

LINC00240 interacted with oncoprotein DDX21 in gastric cancer cells

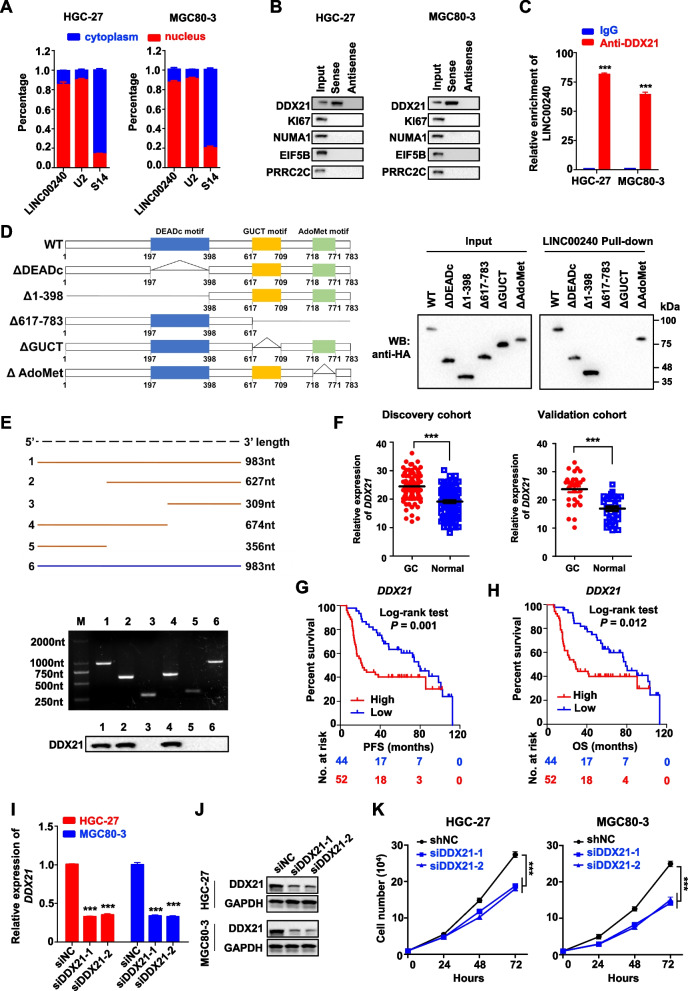

To explore how LINC00240 contributing to gastric tumorigenesis, we firstly detected the cellular localization of LINC00240 in gastric cancer cells. Interestingly, we found that LINC00240 locates dominantly in nucleus of gastric cancer cells (Fig. 4A). Accumulating evidences demonstrated that lncRNAs could function as protein-binding scaffolds in various malignancies [15, 23, 26, 27]. To test if LINC00240 interacts with certain proteins in gastric cancer, we then performed RNA pulldown assays plus mass spectrometry proteomics with the MGC80-3 cell extracts pulled-down by LINC00240. Among proteins pulled-down by LINC00240 (Supplementary Table 4), we successfully verified DDX21 as the lncRNA-binding protein through independent RNA pulldown assays and Western blot in HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells (Fig. 4B). Nevertheless, other four cancer-related candidate proteins (KI67, NUMA1, EIF5B and PRRC2C) could not be validated in cells (Fig. 4B). Importantly, RIP assays indicated that there was noticeable enrichment of LINC00240 in RNA–protein complexes precipitated with the anti-DDX21 antibody in both gastric cancer cell lines as compared with the IgG control (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4C). To explore the specific regions or domains required for the interaction between LINC00240 and DDX21, we then constructed various truncated DDX21 constructs and truncated LINC00240 plasmids (Fig. 4D and E). The results elucidated that the GUCT motif (aa 617–709) of DDX21 protein and the middle region of LINC00240 RNA (nucleotides 357–674) are required for the interaction between LINC00240 and the protein (Fig. 4D and E).

Fig. 4.

LINC00240 interacts with oncoprotein DDX21 in gastric cancer cells. A LINC00240 predominantly locates in the nuclear fraction of gastric cancer cells. B LINC00240 pull-down followed by Western blot validated its interaction with DDX21 and other candidate proteins identified by Mass spectrometry. C LINC00240 could be precipitated with antibody against DDX21 as compared with the IgG control in HGC-27 and MGC80-3 cells. Relative enrichment (means ± SD) represents RNA levels associated with DDX21 relative to an input control from three independent experiments. D Diagrams of HA-tagged DDX21 and its truncated forms used in LINC00240 pull-down assays. Western blot of HA-tagged wild-type (WT) DDX21 and its truncated forms retrieved by in vitro transcribed biotinylated LINC00240. E Truncated LINC00240 mapping of DDX21 binding domain. Top panel: schematic diagrams of LINC00240 full-length and truncated fragments. Middle panel: RNA sizes of in vitro transcribed full-length and truncations of LINC00240. Bottom panel: Western blot of DDX21 pulled down by various LINC00240 fragments. F There were evidently increased DDX21 expression in gastric cancer tissues compared to normal tissues in both Discovery cohort and Validation cohort. G, H The high expression levels of DDX21 were significantly associated with poor OS or PFS of gastric cancer patients. I, J Silencing of DDX21 expression with different siRNAs in HGC-27 and MGC80-3 cells. K DDX21-knockdown significantly suppressed proliferation of HGC-27 and MGC80-3 gastric cancer cell lines. Data are shown as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 by unpaired Student’s t test (C, F, J, K)

DDX21 is a crucial DEAD cassette RNA helicase and acts as an oncogene in multiple cancers [28–34]. Indeed, significantly elevated DDX21 expression in gastric cancer tissues was also observed compared to normal tissues in both Discovery cohort and Validation cohort (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4F). Aberrantly high expression of DDX21 was associated with poor OS or PFS of gastric cancer patients (log-rank P = 0.001 or 0.012; Cox regression P = 0.029 or 0.027) (Fig. 4 G and H). In line with these data, silencing of DDX21 profoundly inhibited viability of HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells (Fig. 4I-K), indicating the oncogenic nature of DDX21 in gastric cancer. Collectively, these findings suggested that LINC00240 could interact with oncoprotein DDX21 via the GUCT motif in gastric cancer cells.

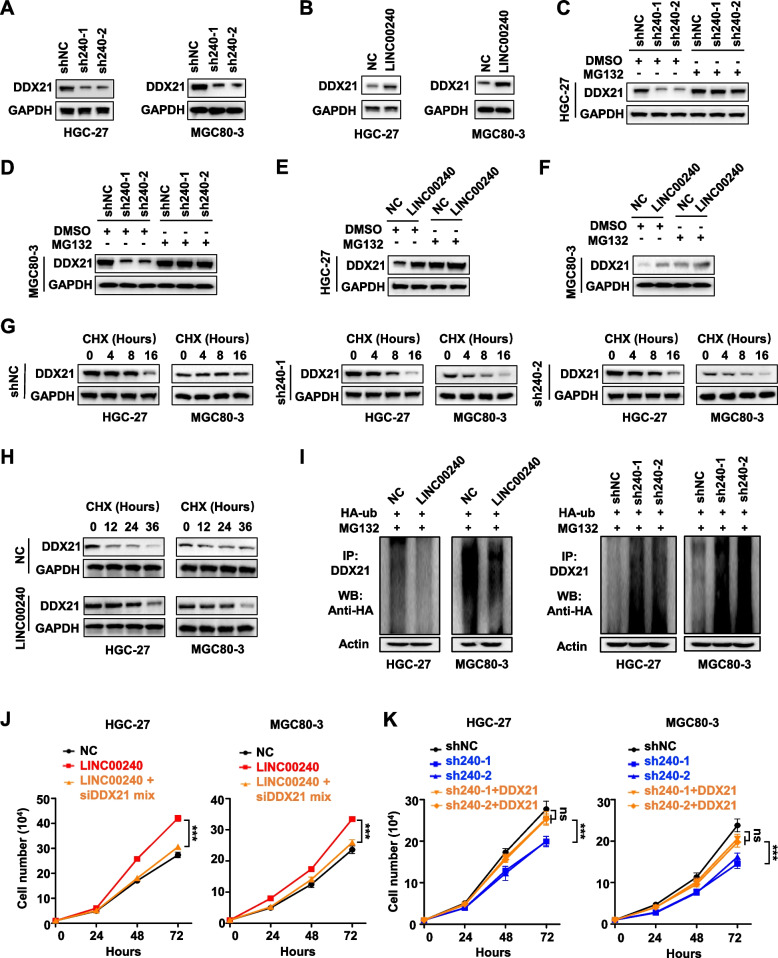

LINC00240 repressed DDX21 degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway

Intriguingly, silencing of LINC00240 evidently suppressed DDX21 protein expression in gastric cancer cells (Fig. 5A). On the contrary, over-expressed LINC00240 markedly up-regulated DDX21 protein levels in HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells (Fig. 5B). Treatment of the stably LINC00240-KD gastric cancer cells with the 26S protostome inhibitor MG132 increased expression of endogenous DDX21 protein compared to the controls (Fig. 5 C and D). In contrast, MG132 abolished LINC00240-induced up-regulation of DDX21 protein in HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells (Fig. 5 E and F), indicating that the lncRNA might participate in regulating the proteasome degradation of DDX21. To verify this, we next examined DDX21 expression in HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor CHX. It was found that the DDX21 protein levels declined much faster in the stably LINC00240-KD cells than those in the control cells (Fig. 5G). Conversely, treatment of the stably LINC00240-OE gastric cancer cells with CHX led to an evidently longer half-life of DDX21 protein than in control cells (Fig. 5H). We then explored whether LINC00240-dependent degradation of DDX21 was mediated by its ubiquitination. After endogenous DDX21 was immunoprecipitated in cells transfected with HA-Ub, strikingly increased ubiquitin signals of DDX21 protein were detected in the stably LINC00240-KD cells in comparison to the control cells (Fig. 5I). In line with this, the ubiquitination of DDX21 was evidently decreased in the stably LINC00240-OE cells compared to the control cells (Fig. 5I). Rescue assays indicated that silencing of DDX21 with siRNAs significantly inhabited proliferation of gastric cancer cells with stably overexpressed LINC00240 (both P < 0.001) (Fig. 5J). On the contrary, over-expression of DDX21 could enhance cell proliferation of gastric cancer cells with stable silencing of LINC00240 with shRNAs (all P > 0.05) (Fig. 5K). Taken together, these results elucidated that LINC00240 stabilize DDX21 protein via the ubiquitin–proteasome system.

Fig. 5.

LINC00240 represses DDX21 degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. A, B Western blot analyses of DDX21 protein in cells with stable knock-down of LINC00240 or enforced expression of LINC00240. C, D Treatment of the stably LINC00240-knock-down gastric cancer cells with the 26S protostome inhibitor MG132 elevated expression of DDX21 protein. E, F Treatment of gastric cancer cells with MG132 eliminated LINC00240-induced upregulation of DDX21 protein expression. G, H Gastric cancer cells with stable LINC00240-knockdown, overexpression of LINC00240 and control cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated periods of time. I Western blot of the ubiquitination of DDX21 in cells that stabilized silenced LINC00240 or over-expressed LINC00240. J Silencing of DDX21 with siRNAs significantly inhibited proliferation of HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells with stably overexpressed LINC00240. J Over-expression of DDX21 could enhance growth of gastric cancer cells with stable silencing of LINC00240 with shRNAs. Data are shown as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 by unpaired Student’s t test (J, K). ns: not significant

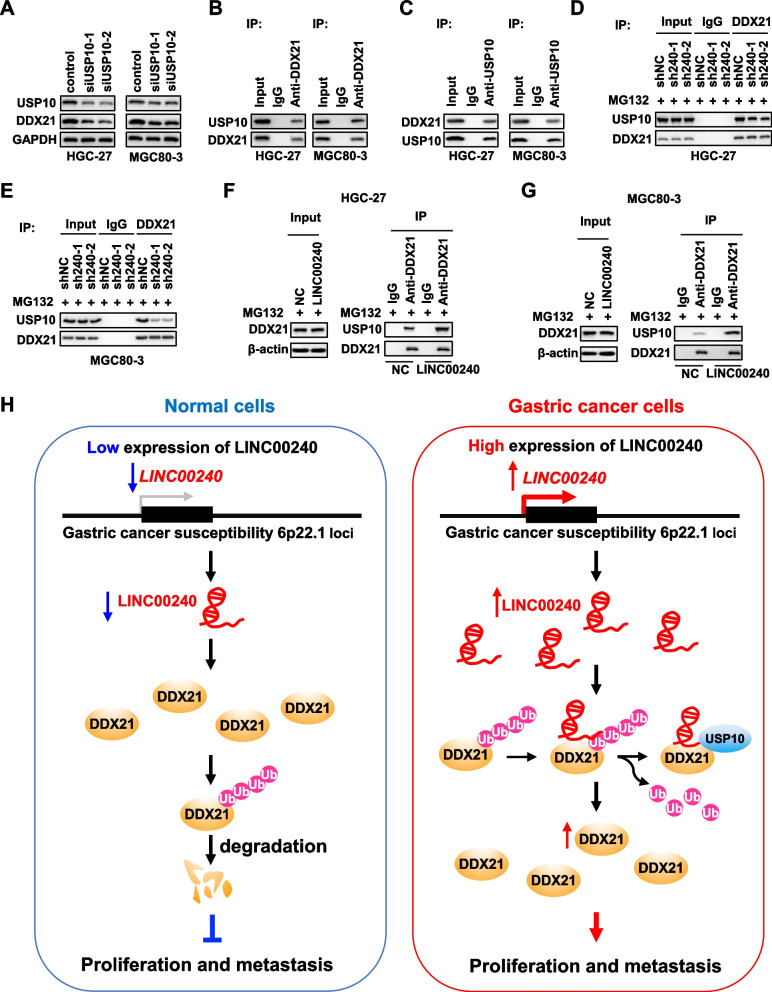

LINC00240 interrupts binding of DDX21 with its novel deubiquitinase USP10

To reveal how LINC00240 retards the ubiquitin–proteasome degradation of DDX21, we analyzed proteins pulled-down by LINC00240 in MGC80-3 cells. Mass spectrometry indicated that there was only one deubiquitinase, USP10. To confirm if USP10 is a novel deubiquitinase of DDX21, we firstly examined DDX21 levels in HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells with silenced expression of USP10 (Fig. 6A). After knock-downing of USP10 expression, obviously decreased DDX21 protein levels could be detected in gastric cancer cells in comparation with the control cells (Fig. 6A). Importantly, Co-IP assays showed that endogenous USP10 could be precipitated with DDX21 in HGC-27 or MGC80-3 cells (Fig. 6B). Endogenous DDX21 could also be precipitated with USP10 in both gastric cancer cell lines (Fig. 6C). These data elucidated that USP10 might be a potential deubiquitinase of DDX21 in gastric cancer. We next investigated if LINC00240 impacts interactions between DDX21 and USP10 in cells. Less USP10 protein could be precipitated with DDX21 in the stably LINC00240-KD cells compared to the control cells (Fig. 6 D and E). In contrast, more USP10 protein could be precipitated with DDX21 in the stably LINC00240-OE cells compared to the control gastric cancer cells (Fig. 6 D and G). Furthermore, silencing of LINC00240 evidently suppressed DDX21 protein expression in gastric cancer xenografts (Supplementary Fig. 3B). However, LINC00240 did not impact the expression level of USP10 protein in xenografts (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Together, these findings suggested that LINC00240 promotes DDX21 stabilization via intensifying interactions between DDX21 and its novel deubiquitinase USP10 in gastric cancer (Fig. 6H).

Fig. 6.

LINC00240 facilitates the interaction between DDX21 and the deubiquitinase USP10. A Silencing of USP10 significantly suppressed DDX21 protein expression in gastric cancer cells. B, C Interactions between USP10 and DDX21 in gastric cancer cells were verified via Co-IP assays. D, E Silencing of LINC00240 diminished the interaction between USP10 and DDX21 in HGC-27 and MGC80-3 cells. F, G Overexpressed LINC00240 strengthened the interaction between USP10 and DDX21. H Diagram depicted how LINC00240 promotes DDX21 stabilization via intensifying interactions between DDX21 and its novel deubiquitinase USP10

Discussion

In this study, we identified a novel gastric cancer susceptibility gene, LINC00240, in the 6p22.1 risk locus. There were significantly higher LINC00240 expression levels in gastric cancer tissues as compared with normal specimens. High levels of LINC00240 are associated with evidently shortened OS or PFS time of gastric cancer patients. LINC00240 functions as an oncogene to enhance malignant behaviors of gastric cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. We also found that LINC00240 interacts with oncoprotein DDX21, suppresses its ubiquitination and stabilize the protein via intensifying binding of DDX21 with its novel deubiquitinase USP10, which, thus, leading to disease progression of gastric cancer (Fig. 6H). This line of research provides compelling evidences which contributing to the understanding of the genetic component and pathogeneses of gastric cancer.

GWAS have identified many independent genetic signals associated with cancer risk [35]. However, understanding the mechanisms by which these susceptibility genomic loci have an impact on associated cancers remains a great hurdle. Multiple lines of evidences indicated that lncRNAs are transcribed from these cancer-risk loci and confer to tumorigenesis [17–20, 36–39]. For instance, PCAT1, PVT1, and PCAT19 in prostate cancer, CUPID1 and CUPID2 in breast cancer, PTCSC2 and PTCSC3 in thyroid cancer, LINC00673 in pancreatic cancer, lncPSCA in gastric cancer, as well as LCETRL3 and LCETRL4 in non-small cell lung cancer, are implicated in malignant development. Guo et al. found that lncRNA PCAT1 binds AR and LSD1 and is essential for their recruitment to the enhancers of GNMT and DHCR24, two important genes in prostate cancer development and progression [16]. Another such example is lncRNA PTCSC2 which interacts with MYH9 and, thus, reverses MYH9-mediaed inhibition of activities of a bidirectional promoter shared by FOXE1 and PTCSC2 in thyroid cancer [38]. Our study, for the first time, indicated that LINC00240 is a novel gastric cancer susceptibility gene transcribed from the GWAS-identified 6p22.1 locus, highlighting the functional impotence of lncRNAs at risk loci during cancer progression.

DEAD-box RNA helicases are crucial for regulating various RNA metabolism. DDX21 is a member of the DEAD-box RNA helicase family that can promote malignant behaviors via various mechanisms [28–34]. DDX21 controls ribosome biogenesis via sensing the transcriptional status of both RNA Pol I and II in cells [28, 34]. That is, DDX21 interacts with 7SK RNA and is recruited to the promoters of genes encoding ribosomal proteins as well as snoRNAs to enhance their transcription [28, 34]. Consistently, DDX21 could stimulate breast cancer cell proliferation through activation of PARP-1, rDNA transcription, ribosome biogenesis, and protein translation [30]. For a number of biological processes, maintenance of sufficient nucleotide pools is vital. Alterations during nucleotide metabolism may lead to malignant transformation and tumorigenesis [31]. Intriguingly, knockdown of ddx21 in zebrafishes confers resistance to nucleotide depletion. DDX21 acts as a sensor of nucleotide stress and contributes to melanoma development [31]. Furthermore, DDX21 plays its oncogenic role in colorectal cancer via inducing genome fragility, damaging double-strand repair and procrastinating HR repair [33]. In line with these findings, we also found that the high expression of DDX21 in gastric cancer leads to poor prognosis and disease progression of gastric cancer patients.

Emerging evidence demonstrates that deubiquitylases significantly contribute to a number of malignancies including gastric cancer. As a deubiquitinase essential for the deubiquitylation, USP10 controls turnover and function of many substrates including p53, H2A.Z, SIRT6, NEMO, TOP2α, AMPK, p14ARF, FLT3, KLF4, YAP/TAZ, NICD1 and MSH2 [40–51], which play key roles in multiple oncogenic signaling pathways. For example, USP10 is the important deubiquitinase required to stabilize oncogenic forms of the kinase FLT3, a critical therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [47]. Targeting of USP10 with its small-molecule inhibitors showed efficacy in preclinical models of mutant-FLT3 AML [47]. Similarly, USP10 acts as a YAP/TAZ-activating deubiquitinase through directly binding and reverting their proteolytic ubiquitination [49]. USP10 defects improved polyubiquitination of YAP/TAZ and their proteasomal degradation in hepatocellular carcinoma [49]. Interestingly, in the current study, we also identified USP10 as a binding partner for both DDX21 and LINC00240. Additionally, we for the first time reported that LINC00240 enhances USP10-mediated deubiquitylation of DDX21 and evaluates DDX21 levels.

In summary, we revealed the importance of LINC00240 transcribed from the 6p22.1 locus in gastric cancer and uncovered a novel regulatory partnership between LINC00240 and USP10 in controlling ubiquitination of oncogenic protein DDX21. Given their vital roles and high abundances in gastric cancer, the LINC00240-USP10-DDX21 axis could be a potential therapeutic target for the lethal disease in the clinic.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1. Primers for RT-qPCR. Supplementary Table 2. Sequences of shRNAs and siRNAs. Supplementary Table 3. Antibodies used in the study. Supplementary Table 4. Mass spectrometry of proteins pulled-down by LINC00240 in MGC80-3 cells

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure 1. The relative expression levels of LINC00240 in human GES-1, MKN-28, MKN-45, AGS, BGC-823, HGC-27 and MGC-803 cell lines. ***P < 0.001. Supplementary Figure 2. Silencing of LINC00240 significantly promoted apoptosis of gastric cancer cells (A), but did not impact cell cycle (B). Supplementary Figure 3. Expression of apoptotic proteins (A), DDX21 and USP10 (B) in gastric cancer xenografts.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- GWASs

Genome-wide association studies

- lncRNAs

Long noncoding RNAs

- Pol II

RNA polymerase II

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- RT-qPCR

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

- OE

Overexpression

- KD

Knockdown

- LS-MS/MS

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- RNA-IP

RNA immunoprecipitation

- PVDF

Polyvinylidene fluoride

- CHX

Cycloheximide

- HA-ubi

HA-ubiquitin

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- OS

Overall survival

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

Authors’ contributions

MY and NZ conceived and designed this study. NZ, BW, and CM performed the experiments. MY and NZ acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data from experiments. BW, JZ, TW, and LH collected the human samples. MY and NZ drafted the manuscript. MY and NZ critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. MY supervised this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82173070 and 82103291); Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2021LZL004 and ZR202102250889); Major Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of Shandong Province (2021ZDSYS04); Taishan Scholars Program of Shandong Province (tsqn202211340 and tstp20221141); Program of Science and Technology for the youth innovation team in universities of Shandong Province (2020KJL001 and 2022KJ316).

Availability of data and materials

All data are included in the manuscript. Materials used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional Review Board of Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Nasha Zhang, Bowen Wang, and Chi Ma contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plummer M, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Forman D, de Martel C. Global burden of gastric cancer attributable to Helicobacter pylori. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:487–490. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, et al. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:420–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Study Group of Millennium Genome Project for C. Sakamoto H, Yoshimura K, Saeki N, Katai H, Shimoda T, et al. Genetic variation in PSCA is associated with susceptibility to diffuse-type gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:730–40. doi: 10.1038/ng.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abnet CC, Freedman ND, Hu N, Wang Z, Yu K, Shu XO, et al. A shared susceptibility locus in PLCE1 at 10q23 for gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2010;42:764–767. doi: 10.1038/ng.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saeki N, Saito A, Choi IJ, Matsuo K, Ohnami S, Totsuka H, et al. A functional single nucleotide polymorphism in mucin 1, at chromosome 1q22, determines susceptibility to diffuse-type gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:892–902. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Y, Hu Z, Wu C, Dai J, Li H, Dong J, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for non-cardia gastric cancer at 3q13.31 and 5p13.1. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1215–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helgason H, Rafnar T, Olafsdottir HS, Jonasson JG, Sigurdsson A, Stacey SN, et al. Loss-of-function variants in ATM confer risk of gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47:906–910. doi: 10.1038/ng.3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu N, Wang Z, Song X, Wei L, Kim BS, Freedman ND, et al. Genome-wide association study of gastric adenocarcinoma in Asia: a comparison of associations between cardia and non-cardia tumours. Gut. 2016;65:1611–1618. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Dai J, Hu N, Miao X, Abnet CC, Yang M, et al. Identification of new susceptibility loci for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma: pooled results from two Chinese genome-wide association studies. Gut. 2017;66:581–587. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu M, Yan C, Ren C, Huang X, Zhu X, Gu H, et al. Exome Array Analysis Identifies Variants in SPOCD1 and BTN3A2 That Affect Risk for Gastric Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:2011–2021. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanikawa C, Kamatani Y, Toyoshima O, Sakamoto H, Ito H, Takahashi A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies gastric cancer susceptibility loci at 12q24.11–12 and 20q11.21. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:4015–24. doi: 10.1111/cas.13815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan C, Zhu M, Ding Y, Yang M, Wang M, Li G, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies and functional assays decipher susceptibility genes for gastric cancer in Chinese populations. Gut. 2020;69:641–651. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin G, Lv J, Yang M, Wang M, Zhu M, Wang T, et al. Genetic risk, incident gastric cancer, and healthy lifestyle: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies and prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1378–1386. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng Y, Lei T, Jin G, Guo H, Zhang N, Chai J, et al. LncPSCA in the 8q24.3 risk locus drives gastric cancer through destabilizing DDX5. EMBO Rep. 2021;22:e52707. doi: 10.15252/embr.202152707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo H, Ahmed M, Zhang F, Yao CQ, Li S, Liang Y, et al. Modulation of long noncoding RNAs by risk SNPs underlying genetic predispositions to prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1142–1150. doi: 10.1038/ng.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betts JA, MoradiMarjaneh M, Al-Ejeh F, Lim YC, Shi W, Sivakumaran H, et al. Long Noncoding RNAs CUPID1 and CUPID2 Mediate breast cancer risk at 11q13 by modulating the response to DNA damage. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho SW, Xu J, Sun R, Mumbach MR, Carter AC, Chen YG, et al. Promoter of lncRNA Gene PVT1 Is a Tumor-Suppressor DNA Boundary Element. Cell. 2018;173:1398–412 e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao P, Xia JH, Sipeky C, Dong XM, Zhang Q, Yang Y, et al. Biology and Clinical Implications of the 19q13 Aggressive Prostate Cancer Susceptibility Locus. Cell. 2018;174:576–89 e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MoradiMarjaneh M, Beesley J, O'Mara TA, Mukhopadhyay P, Koufariotis LT, Kazakoff S, et al. Non-coding RNAs underlie genetic predisposition to breast cancer. Genome Biol. 2020;21:7. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1876-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian J, Lou J, Cai Y, Rao M, Lu Z, Zhu Y, et al. Risk SNP-mediated enhancer-promoter interaction drives colorectal cancer through both FADS2 and AP002754.2. Cancer Res. 2020;80:1804–18. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang N, Song Y, Xu Y, Liu J, Shen Y, Zhou L, et al. MED13L integrates Mediator-regulated epigenetic control into lung cancer radiosensitivity. Theranostics. 2020;10:9378–9394. doi: 10.7150/thno.48247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Shen Y, Xie M, Wang B, Wang T, Zeng J, et al. LncRNAs LCETRL3 and LCETRL4 at chromosome 4q12 diminish EGFR-TKIs efficiency in NSCLC through stabilizing TDP43 and EIF2S1. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:30. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00847-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Ye T, Xue B, Yang M, Li R, Xu X, et al. Mitochondrial GRIM-19 deficiency facilitates gastric cancer metastasis through oncogenic ROS-NRF2-HO-1 axis via a NRF2-HO-1 loop. Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:117–132. doi: 10.1007/s10120-020-01111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye T, Yang M, Huang D, Wang X, Xue B, Tian N, et al. MicroRNA-7 as a potential therapeutic target for aberrant NF-kappaB-driven distant metastasis of gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:55. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1074-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adnane S, Marino A, Leucci E. LncRNAs in human cancers: signal from noise. Trends Cell Biol. 2022;32:565–573. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen B, Dragomir MP, Yang C, Li Q, Horst D, Calin GA. Targeting non-coding RNAs to overcome cancer therapy resistance. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:121. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00975-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calo E, Flynn RA, Martin L, Spitale RC, Chang HY, Wysocka J. RNA helicase DDX21 coordinates transcription and ribosomal RNA processing. Nature. 2015;518:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature13923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao J, Wu N, Han Y, Hou Q, Zhao Y, Pan Y, et al. DDX21 promotes gastric cancer proliferation by regulating cell cycle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;505:1189–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim DS, Camacho CV, Nagari A, Malladi VS, Challa S, Kraus WL. Activation of PARP-1 by snoRNAs controls ribosome biogenesis and cell growth via the RNA Helicase DDX21. Mol Cell. 2019;75:1270–85 e14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santoriello C, Sporrij A, Yang S, Flynn RA, Henriques T, Dorjsuren B, et al. RNA helicase DDX21 mediates nucleotide stress responses in neural crest and melanoma cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22:372–379. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-0493-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang K, Yu X, Tao B, Qu J. Downregulation of lncRNA HCP5 has inhibitory effects on gastric cancer cells by regulating DDX21 expression. Cytotechnology. 2021;73:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10616-020-00429-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie J, Wen M, Zhang J, Wang Z, Wang M, Qiu Y, et al. The Roles of RNA Helicases in DNA Damage Repair and Tumorigenesis Reveal Precision Therapeutic Strategies. Cancer Res. 2022;82:872–884. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xing YH, Yao RW, Zhang Y, Guo CJ, Jiang S, Xu G, et al. SLERT Regulates DDX21 Rings Associated with Pol I Transcription. Cell. 2017;169:664–78 e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Przybyla L, Gilbert LA. A new era in functional genomics screens. Nat Rev Genet. 2022;23:89–103. doi: 10.1038/s41576-021-00409-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jendrzejewski J, He H, Radomska HS, Li W, Tomsic J, Liyanarachchi S, et al. The polymorphism rs944289 predisposes to papillary thyroid carcinoma through a large intergenic noncoding RNA gene of tumor suppressor type. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8646–8651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205654109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He H, Li W, Liyanarachchi S, Jendrzejewski J, Srinivas M, Davuluri RV, et al. Genetic predisposition to papillary thyroid carcinoma: involvement of FOXE1, TSHR, and a novel lincRNA gene, PTCSC2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E164–E172. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, He H, Li W, Phay J, Shen R, Yu L, et al. MYH9 binds to lncRNA gene PTCSC2 and regulates FOXE1 in the 9q22 thyroid cancer risk locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:474–479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619917114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng J, Huang X, Tan W, Yu D, Du Z, Chang J, et al. Pancreatic cancer risk variant in LINC00673 creates a miR-1231 binding site and interferes with PTPN11 degradation. Nat Genet. 2016;48:747–757. doi: 10.1038/ng.3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Draker R, Sarcinella E, Cheung P. USP10 deubiquitylates the histone variant H2A.Z and both are required for androgen receptor-mediated gene activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3529–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guturi KKN, Bohgaki M, Bohgaki T, Srikumar T, Ng D, Kumareswaran R, et al. RNF168 and USP10 regulate topoisomerase IIalpha function via opposing effects on its ubiquitylation. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12638. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin Z, Yang H, Tan C, Li J, Liu Z, Quan Q, et al. USP10 antagonizes c-Myc transcriptional activation through SIRT6 stabilization to suppress tumor formation. Cell Rep. 2013;5:1639–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niu J, Shi Y, Xue J, Miao R, Huang S, Wang T, et al. USP10 inhibits genotoxic NF-kappaB activation by MCPIP1-facilitated deubiquitination of NEMO. EMBO J. 2013;32:3206–3219. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan J, Luo K, Zhang L, Cheville JC, Lou Z. USP10 regulates p53 localization and stability by deubiquitinating p53. Cell. 2010;140:384–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim R, Sugino T, Nolte H, Andrade J, Zimmermann B, Shi C, et al. Deubiquitinase USP10 regulates Notch signaling in the endothelium. Science. 2019;364:188–193. doi: 10.1126/science.aat0778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Xia S, Li H, Wang X, Li C, Chao Y, et al. The deubiquitinase USP10 regulates KLF4 stability and suppresses lung tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:1747–1764. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0458-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weisberg EL, Schauer NJ, Yang J, Lamberto I, Doherty L, Bhatt S, et al. Inhibition of USP10 induces degradation of oncogenic FLT3. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:1207–1215. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang M, Hu C, Tong D, Xiang S, Williams K, Bai W, et al. Ubiquitin-specific Peptidase 10 (USP10) Deubiquitinates and Stabilizes MutS Homolog 2 (MSH2) to Regulate Cellular Sensitivity to DNA Damage. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:10783–10791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.700047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu H, Yan F, Yuan T, Qian M, Zhou T, Dai X, et al. USP10 Promotes Proliferation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Deubiquitinating and Stabilizing YAP/TAZ. Cancer Res. 2020;80:2204–2216. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deng M, Yang X, Qin B, Liu T, Zhang H, Guo W, et al. Deubiquitination and Activation of AMPK by USP10. Mol Cell. 2016;61:614–624. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ko A, Han SY, Choi CH, Cho H, Lee MS, Kim SY, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence mediated by c-Myc requires USP10 dependent deubiquitination and stabilization of p14ARF. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:1050–1062. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0072-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1. Primers for RT-qPCR. Supplementary Table 2. Sequences of shRNAs and siRNAs. Supplementary Table 3. Antibodies used in the study. Supplementary Table 4. Mass spectrometry of proteins pulled-down by LINC00240 in MGC80-3 cells

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure 1. The relative expression levels of LINC00240 in human GES-1, MKN-28, MKN-45, AGS, BGC-823, HGC-27 and MGC-803 cell lines. ***P < 0.001. Supplementary Figure 2. Silencing of LINC00240 significantly promoted apoptosis of gastric cancer cells (A), but did not impact cell cycle (B). Supplementary Figure 3. Expression of apoptotic proteins (A), DDX21 and USP10 (B) in gastric cancer xenografts.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript. Materials used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.