ABSTRACT

Trichinellosis is an important foodborne zoonosis, and no effective treatments are yet available. Nod-like receptor (NLR) plays a critical role in the host response against nematodes. Therefore, we aimed to explore the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome (NLRP3) during the adult, migrating, and encysted stages of Trichinella spiralis infection. The mice were treated with the specific NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 after inoculation with T. spiralis. Then, the role that NLRP3 plays during T. spiralis infection of mice was evaluated using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), Western blotting, flow cytometry, histopathological evaluation, bone marrow-derived macrophage (BMDM) stimulation, and immunofluorescence. The in vivo results showed that NLRP3 enhanced the Th1 immune response in the adult and migrating stages and weakened the Th2 immune response in the encysted stage. NLRP3 promoted the release of proinflammatory factors (interferon gamma [IFN-γ]) and suppressed the release of anti-inflammatory factors (interleukin 4 [IL-4]). Pathological changes were also improved in the absence of NLRP3 in mice during T. spiralis infection. Importantly, a significant reduction in adult worm burden and muscle larvae burden at 7 and 35 days postinfection was observed in mice treated with the specific NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950. In vitro, we first demonstrated that NLRP3 in macrophages can be activated by T. spiralis proteins and promotes IL-1β and IL-18 release. This study revealed that NLRP3 is involved in the host response to T. spiralis infection and that targeted inhibition of NLRP3 enhanced the Th2 response and accelerated T. spiralis expulsion. These findings may help in the development of protocols for controlling trichinellosis.

KEYWORDS: T. spiralis, NLRP3, immune response, Th1/Th2

INTRODUCTION

Trichinellosis is an important foodborne parasitic zoonosis mainly caused by ingesting raw or undercooked meat infected with the encapsulated muscle larvae of Trichinella spiralis (T. spiralis) (1, 2). T. spiralis can infect a wide range of mammalian hosts, including humans and more than 150 mammalian species, and it not only leads to great threat to human health worldwide but also represents an economic problem in the livestock industry (3). Although various countries around the world have taken measures to control and suppress the occurrence of the disease, it has not been effectively controlled because its immune response process is complex (4). Therefore, a good understanding of the immune mechanisms may facilitate the discovery of approaches to control trichinellosis.

Increasing attention has been given to defining the role of the host immune response in T. spiralis infection. The innate immune system plays an important role in recognizing pathogens and triggering biological mechanisms to control infection and eliminate pathogens (5). It is activated when pattern recognition sensor proteins, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), detect the presence of pathogens, their products, or danger signals (6). NLR inflammasomes play a central role in innate immunity (7). The NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome (NLRP3) is a protein complex consisting of the NLRP3 scaffold, ASC adaptor, and procaspase-1. NLRP3, which includes mature caspase-1, can promote the activation of cytokines such as interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) and IL-18 and promote the occurrence of an inflammatory response (8). NLRP3 inflammasome complexes are the most intensively studied and are activated by a broad range of stimuli. Recently, considerable evidence has suggested that NLRP3 activation is essential for the control of different parasitic infections, as it plays a protective role in reducing Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum infection loads (9, 10). In addition, NLRP3 has been involved in the inhibition of eosinophil influx that results from the type 2 response to the parasite in mice infected with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (11). Despite the critical role of inflammasomes in the immune response to parasites, their contribution to the immune response during T. spiralis chronic infections is unclear.

The parasitic process can be divided into adult, migrating, and encysted stages (12). With the transition of larvae from the intestinal phase to the encysted stage in the host, the host’s immune type gradually changes from Th1 to Th2 and concurrent changes in levels of Th1/Th2-related cytokines (13, 14). CD4-positive (CD4+) T cells play a key role in parasite immunity and can differentiate into different subpopulations, including Th1, Th2, Th17, and regulatory T cells (Treg) cells. T. spiralis and its secretory products can induce Th2 immune responses to suppress inflammatory responses (13). Recent studies have shown that Th2 immune responses may help accelerate worm expulsion and reduce tissue damage and strengthen tissue repair (15). The changes in Th1 and Th2 immune types mainly rely on the secretion of cytokines (16).

In this study, we intraperitoneally injected mice with an NLRP3 inhibitor (MCC950) at different developmental stages of T. spiralis development to explore the role of NLRP3 within T. spiralis infection. The aim of the study was to detect the effects of NLRP3 on parasitism and immunity of T. spiralis in adult, migrating, and encysted stages.

RESULTS

NLRP3 increases the Th1 response during T. spiralis infection.

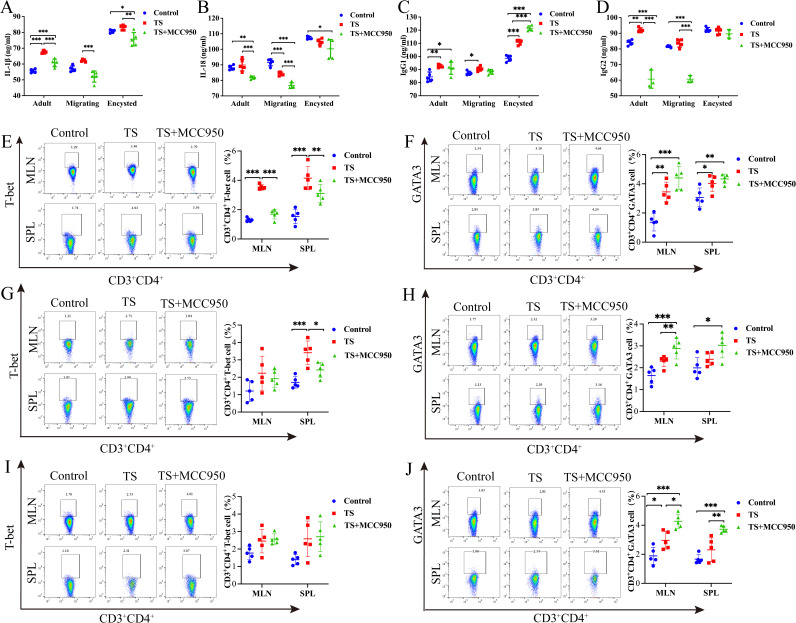

To determine whether the NLRP3 is involved in T. spiralis infection. The contents of the cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 and host immune types IgG1 and IgG2 were detected by ELISA kits in the adult stage, migrating stage, and encysted stage, as shown in Fig. 1. With respect to IL-1β, the T. spiralis infection plus treatment with MCC950 (T. spiralis plus MCC950 group) showed a significant decrease compared with the T. spiralis group (T. spiralis infection) in the migrating and adult stages (P < 0.001) and encysted stages (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1A). IL-18 excretion was also significantly decreased in the adult and migrating stages (P < 0.001) and encysted stage (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1B). In the adult and migrating stages, the excretion of IgG2 of T. spiralis plus MCC950 group was significantly decreased compared to the T. spiralis group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1C and D). There was no significant difference excretion of IgG1 (P > 0.05) (Fig. 1C and D). In contrast, in the encysted stage, the excretion of IgG1 of T. spiralis plus MCC950 group was significantly increased (P < 0.001), and there was no observable difference in IgG2 excretion (P > 0.05) (Fig. 1C and D).

FIG 1.

The content of the cytokines IL-1β, IL-18, IgG1, and IgG2 in the serum of various groups of mice at 7, 14, and 35 dpi was detected by ELISA. (A) Levels of IL-1β. (B) Levels of IL-18. (C) Levels of IgG1. (D) Levels of IgG2. The expression of T-bet and GATA3 in the SPL and MLN of mice of various groups was analyzed by flow cytometry on days 7, 14, and 35. (E) Expression of T-bet in the adult stage. (F) Expression of GATA3 in the adult stage. (G) Expression of T-bet in the adult stage. (H) Expression of GATA3 in the migrating stage. (I) Expression of T-bet in the cycle stage. (J) Expression of GATA3 in the cycle stage. Data are the mean ± SD of each group (n = 5) from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To determine whether NLRP3 plays a role in the development of Th1 or Th2 cells, the levels of T-bet (Th1 transcription factor) and GATA3 (Th2 transcription factor) in CD4+ T cells were assessed. The T-bet expression levels were increased in the spleen (SPL) or mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) of the TS mice significantly in the adult and migrating stages compared to the control group (P < 0.001, P < 0.01). This increase was also inhibited by MCC950 (P < 0.05 and P < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 1E and G). However, there were no significant differences in the encysted stages (Fig. 1I). The results showed that T. spiralis infection promoted the expression of GATA3. In addition, the GATA3 expression levels in the SPL or MLN of T. spiralis plus MCC950 mice were increased significantly in the encysted and migrating stages compared to the control and T. spiralis groups (P < 0.001, P < 0.01) (Fig. 1F, H, and J).

These results suggest that NLRP3 participates in T. spiralis infection and that NLRP3 promotes the host Th1-type immune response in the adult and migrating stages and inhibits the Th2-type immune response in the encysted stage.

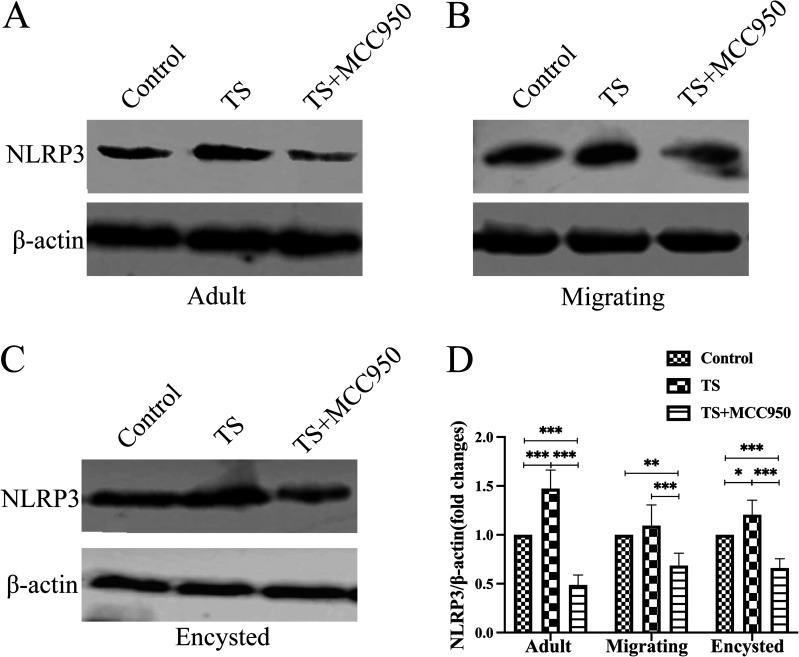

T. spiralis infection promotes the expression of NLRP3 in the small intestine.

The protein expression of NLRP3 in the intestine was detected by Western blotting (Fig. 2). NLRP3 was upregulated during the adult and encysted stages compared to the control group (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 2A, C, and D). This increase was also inhibited by MCC950 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A, C, and D). However, there was no observable difference in NLRP3 expression during the migrating stage (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2B and D), although the expression tended to gradually increase in the T. spiralis group compared to the control group. This illustrated that T. spiralis could promote the expression of NLRP3 in the adult and encysted stages.

FIG 2.

Detection of NLRP3 protein by Western blot analysis for NLRP3 protein levels in the adult (A), migrating (B), and cycle (C) stages. (D) Bar plot depicting the NLRP3/β-actin ratios as determined by densitometric analysis of Western blotting and expressed as fold change compared with the control group. Data are the mean ± SD of each group (n = 5) from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

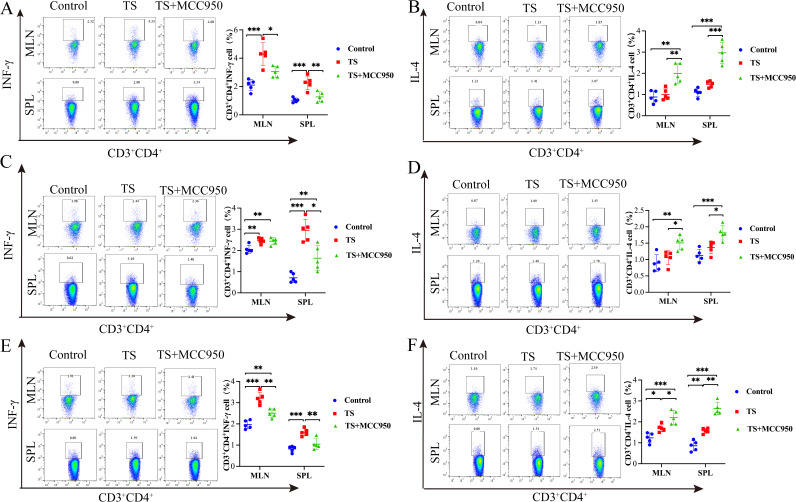

Effects of NLRP3 on IFN-γ and IL-4 during T. spiralis infection.

We detected the impact of NLRP3 expression on changes in the expression of proinflammatory factors (interferon gamma [IFN-γ]) and anti-inflammatory factors (IL-4). In the adult migrating and encysted stages, flow cytometry assays showed that the IFN-γ expression levels in the SPL and MLN in the T. spiralis plus MCC950 group were significantly decreased compared with the T. spiralis group (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, specifically) (Fig. 3A, C, and E). However, the levels of IL-4 increased significantly in the SPL and MLN of the TS and MCC950 group compared with the control group and T. spiralis group (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, and P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 3B, D, and F).

FIG 3.

The expression of IFN-γ and IL-4 in the SPL and MLN of mice of various groups was analyzed by flow cytometry on days 7, 14, and 35. (A) Expression of IFN-γ in the adult stage. (B) Expression of IL-4 in the adult stage. (C) Expression of IFN-γ in the migrating stage. (D) Expression of IL-4 in the migrating stage. (E) Expression of IFN-γ in the cycle stage. (F) Expression of IL-4 in the cycle stage. Data are the mean ± SD of each group (n = 5) from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

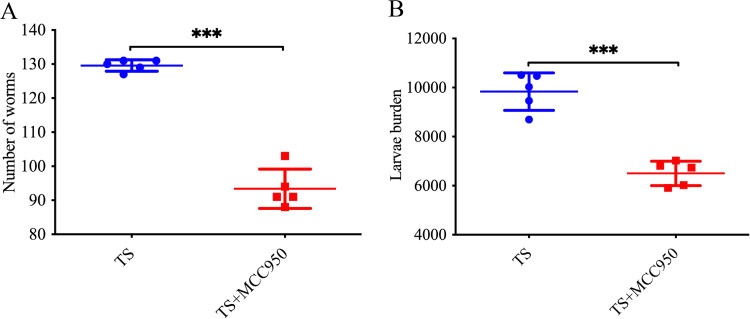

NLRP3 enhances the burden of intestinal worms and muscle larvae during T. spiralis infection.

Five mice were randomly selected from the T. spiralis group and the T. spiralis plus MCC950 group in the adult stage (7 days) and encysted stage (35 days), and the number of worms was obtained by separating muscle larvae and adults of T. spiralis. The results showed that the number of worms in the T. spiralis plus MCC950 group was significantly reduced compared with that in the T. spiralis group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A), and the number of muscle larvae was significantly reduced (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). It was concluded that NLRP3 could enhance the survival of T. spiralis in the host.

FIG 4.

Adult and muscle larvae burden. (A) Intestinal adult burden at day 7 after infection with T. spiralis. (B) Muscle larval burden in muscle at day 35 after infection with T. spiralis. Mice were infected with 400 muscle larvae. Data are the mean ± SD of each group (n = 5) from three independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001.

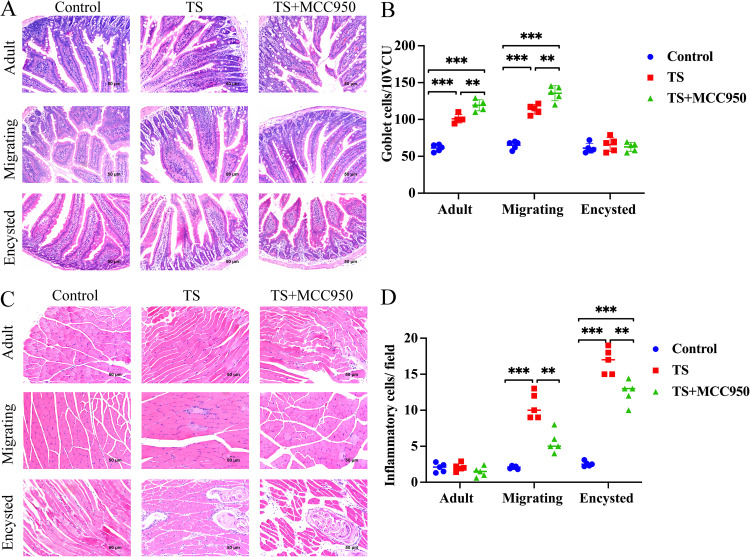

Effects of NLRP3 on the pathological damage to intestinal and masseter muscle in mice during T. spiralis infection.

To investigate how NLRP3 enhances the burden of intestinal worms and muscle larvae during T. spiralis infection, we observed goblet cell hyperplasia of the intestinal epithelium and inflammatory cell infiltration of masseter muscle, which are characteristic of intestinal nematode infection (Fig. 5A and B). The number of intestinal goblet cells increased on days 7 and 14 in T. spiralis-infected mice compared with noninfected mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5B). Compared with mice in the T. spiralis group, mice in the T. spiralis plus MCC950 group showed goblet cell hyperplasia in the intestinal mucosa in the adult and migrating stages (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5B), the mucosal epithelium was integral, and the morphology of the villi was normal (Fig. 5A). There was no significant difference in the encysted stage. Histological observation of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained T. spiralis-infected masseter muscle clearly showed inflammatory cell infiltration around the encystation. The level of inflammatory cells was significantly increased sharply in the migrating and encysted stages (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5D). In addition, the T. spiralis plus MCC950 group displayed a significant reduction in inflammatory cellular infiltration and parasite cysts in the muscle compared with the T. spiralis group (Fig. 5C and D) (P < 0.01). Suppressing NLRP3 could increase goblet cells in the intestine and ameliorate inflammatory cell infiltration in the masseter muscle during T. spiralis infection.

FIG 5.

Histological analysis of T. spiralis-infected small intestine and masseter muscle. (A) Representative images of H&E-stained small intestine. (B) Effect of NLRP3 on goblet cell hyperplasia of intestinal epithelium after infection with T. spiralis. The number of goblet cells in 10 VCU was counted. (C) Representative images of H&E-stained masseter muscle tissue. (D) Inflammatory cell infiltration of masseter muscle after infection with T. spiralis. Twenty nonoverlapping representative fields of tissue were imaged under a light microscope using a 200× objective, and the amount of inflammation in a field was counted. The histological test revealed 5 to 10 sections per muscle tissue. Data are the mean ± SD of each group (n = 5) from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

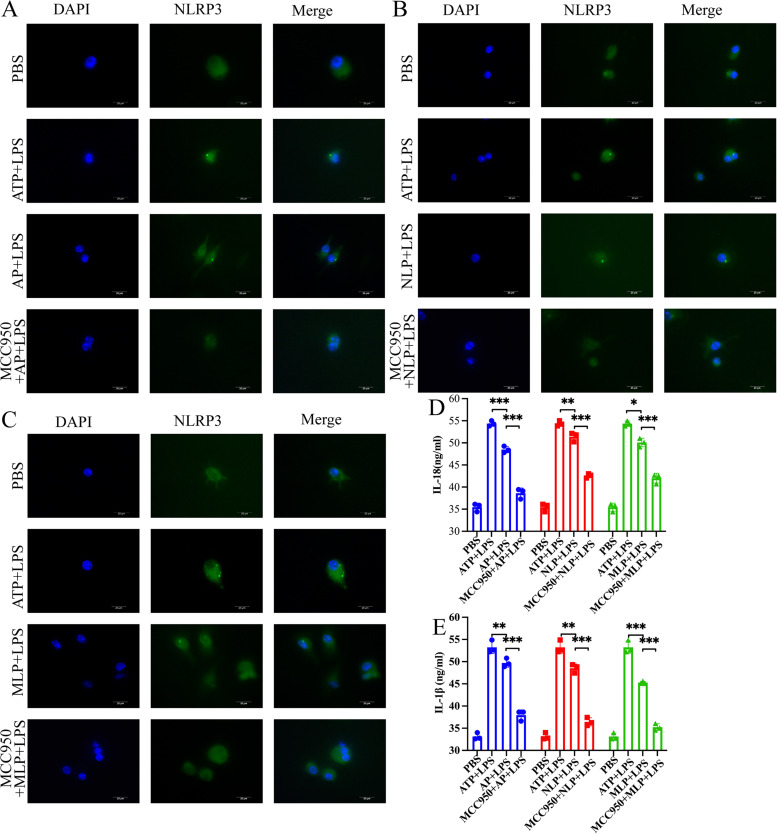

T. spiralis protein activates NLRP3 in BMDMs.

To determine the role of proteins of three different stages of T. spiralis associated with the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, an in vitro culture of mouse BMDMs was performed, and all groups of BMDMs were pretreated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The results showed that the activation of NLRP3 in the stimulation group was higher than that in the phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) group. Moreover, compared with the T. spiralis protein stimulation group (adult protein, newborn larvae, and muscle larvae protein), there was a significant decrease in the activation of NLRP3 in the MCC950 group (Fig. 6A to C). The secretion of IL-18 and IL-1β in the T. spiralis protein stimulation group was significantly lower than that in the positive-control group (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively) but significantly higher than that in the MCC950 group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6D and E). These results suggest that different life cycle stages of T. spiralis proteins promote the activation of NLRP3 and that NLRP3 promotes the secretion of IL-18 and IL-1β in BMDMs.

FIG 6.

T. spiralis proteins activate NLRP3 in BMDMs. All groups of BMDMs were pretreated with LPS. (A) BMDMs were stimulated with adult protein (AP) of T. spiralis. (B) BMDMs were stimulated with neonatal larval proteins (NLP) of T. spiralis. (C) BMDMs were stimulated with muscle larvae protein (MLP) of T. spiralis. Scale bars, 20 μm. (D, E) The contents of the cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 in BMDMs were measured by ELISA. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results being obtained and is expressed in the bar graph as the mean ± SD.

DISCUSSION

Parasitic helminth infestation is the most common chronic disease among humans and animals. At present, due to the complexity of the life cycle of worms, the mechanisms by which antigens induce Th2-type immune responses and initiate inflammation are not entirely clear, and no effective immunological approach is used to control worms (17, 18). Although there is evidence that inflammasome signaling and inflammasome-dependent cytokines are important for host defense against T. spiralis, further studies are needed to establish how the inflammasome affects adaptive immune responses in the context of T. spiralis infections (19). In the present study, we identified that NLRP3 is involved in both innate and adaptive immune responses and the conversion of immune response patterns by regulating the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 during T. spiralis infection. Additionally, we first demonstrated that NLRP3 in macrophages can be activated by T. spiralis proteins and promotes IL-1β and IL-18 release. MCC950 inhibits the activation of NLRP3 to speed up Th2-type immune type-mediated T. spiralis clearance.

NLRP3 is associated with the Th1 immune response and mediates host protection against pathogen invasions (20). Recent studies have also demonstrated that NLRP3 plays an important role in the promotion of Th2 immune responses (21). We confirmed that NLRP3 promotes a Th1 immune response during T. spiralis infections, and this effect may be caused by cytokine secretion of IL-1β and IL-18. IL-18 is one of the best-characterized inflammasome-dependent cytokines whose maturation requires cleavage by caspase-1 from its inactive intracellular precursor pro-IL-18, which can induce IFN-γ production in Th1-type cells and can promote T-cell proliferation (22, 23). Our data support an important role for NLRP3-dependent IL-18 in regulating immunity and inflammation following T. spiralis clearance. Moreover, we demonstrated that IL-1β was similarly regulated by NLRP3 during T. spiralis infection. Previous studies showed that Th2 lymphocyte (CCL17) chemoattractant was strongly reduced in mice deficient in NLRP3 and IL-1β (24, 25). Our findings are consistent with these findings. We demonstrated that the decrease in the expression of IL-18 and IL-1β may lead to an increased Th2-type response and weakening of the Th1-type response when NLRP3 is inhibited after T. spiralis infection. This result was further confirmed by the induced expression levels of GATA3 and reduced expression levels of T-bet. Similar results were obtained in a study using dendritic cells of NLRP3−/− mice (19). Inflammasomes have a regulatory role in the infection of early innate responses and can promote the maturation and production of inflammatory cytokines. There is a large body of evidence related to the involvement of inflammasomes in the innate immune response (26). We demonstrated that NLRP3 induced an inflammatory response and mediates protective immunity to T. spiralis infection, possibly via adaptive immune responses.

Th1 subset cells mediate cellular immunity by secreting IFN-γ, and Th2 subset cells mediate cellular immunity by secreting IL-4 (27, 28). In the present study, NLRP3-inhibited mice displayed decreased IFN-γ levels and increased IL-4 levels, which may promote a shift in the Th1/Th2 balance toward Th2-dominant immunity during the T. spiralis infection, showing that Th2 cell development was regulated by NLRP3 in CD4+ T cells. Some studies have demonstrated Th2 responses that are induced by T. spiralis help expel adult T. spiralis worms and prevent the growth of muscle larvae during infection (29). This explains the lower burden of intestinal worms and muscle larvae observed in this study. Based on the above, inhibition or deletion of NLRP3 expression could provide increased immunity to T. spiralis infection.

Previous studies have shown that NLRP3 plays a key role in pathogenic bacteria-induced progression of acute inflammation (30). Reports have demonstrated that NLRP3 is involved in the inhibition of eosinophil influx to the parasite in mice infected with N. brasiliensis, and IL-1β secretion is mediated by P2X7R in small intestinal epithelial cells in response to Toxoplasma gondii infection (6, 11). T. spiralis infections in host intestinal acute mucosal inflammation, after larvae enter the skeletal muscle tissue, induce a relevant inflammatory reaction that is responsible for myositis and can cause systemic inflammatory manifestations all over the body before entering the striated muscles (31). In this study, we identified that T. spiralis enhances NLRP3-dependent IL-18 and IL-1β secretion, which may contribute to the inflammatory cell infiltration and histological changes observed in the muscle and intestinal tissue.

In the acute phase of the infection, the parasite load dictates the magnitude of the inflammatory response and tissue damage (32). In this study, a significant reduction in adult worm burden and muscle larvae burden at 7 and 35 days postinfection was observed in mice treated with the specific NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950. It has also been found to be effective in the treatment of Trichuris muris (33). NLRP3 inhibition may influence the functions of nonhematopoietic cells in the intestine that promote worm expulsion, including epithelial cell turnover, goblet cell expansion, mucus production, and smooth muscle hypercontractility (33). This is consistent with the increase in goblet cells observed in the absence of NLRP3 in mice during T. spiralis infection in this study. It is conceivable that targeting the NLRP3 pathway in T. spiralis-infected hosts using MCC950 may be a rational approach for lowering worm burdens. However, people living in helminth regions of endemicity are often exposed to coinfections with other parasites, and previous studies have demonstrated a protective role for NLRP3 in these infection models. Some studies have shown that the absence of NLRP3 results in increased parasite burden, such as with Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum (10, 34). Further studies are necessary to assess the impact of such therapeutic strategies on other preventive and curative interventions.

Conclusion.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that NLRP3 regulates immunity and inflammation in T. spiralis infections and that targeted inhibition of NLRP3 enhanced the Th2 response and accelerated T. spiralis expulsion. Therefore, NLRP3 is an important target for controlling T. spiralis infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites and animals.

The T. spiralis isolate ISS534 used in this study was maintained by serial infection of Sprague-Dawley rats from the Animal Parasite Laboratory of Jilin Agricultural University. BALB/c mice (female, 4 to 6 weeks old), and Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Beijing Fukang Biotechnology company. All animal husbandry was maintained in Jilin Agricultural University Animal Experiment Center under the care of a professional breeder with a light/dark cycle of 12 h and with sterile food and water. Furthermore, all experiments in this study were performed in accordance with the Chinese Animal Management Ordinance. The animal experiments were approved by the Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Jilin Agricultural University.

Isolation of T. spiralis adults, newborn larvae, and muscle larvae.

Muscle larvae, adults, and newborn larvae were obtained from rats as previously described (35). In brief, BALB/c mice were orally inoculated with 300 muscle larvae of T. spiralis and sacrificed 7 days postinfection (dpi). The intestine was exposed, and the entire small intestine was harvested and washed by flushing in sterile saline to remove any intestinal contents before the tissue was cut into 3-cm pieces. The small intestine sections were transferred to a separation screening cloth of a nematode larva separator (200 mesh), which was put in a small beaker containing sterile saline (preheated at 37°C) and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. T. spiralis adults were collected from the bottom of the beaker and counted. The adults were incubated and washed in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (RPMI 1640; Gibco) with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin (Gibco), and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The culture solution was filtered with a 280-mesh sterile mesh so that the newborn larvae were collected. Muscle larvae of T. spiralis were obtained by standard pepsin digestion (1% pepsin and 1% HCl at 37°C for 2 h) to release larvae from the muscles of the rats infected at 35 days.

Animal experimental design.

Forty-five healthy female BALB/c mice were randomly divided into three groups, T. spiralis plus MCC950, T. spiralis, and control. T. spiralis plus MCC950 mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected daily with the specific NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 (10 mg/kg) after inoculation with T. spiralis (350 larvae per mouse), whereas the T. spiralis group mice were injected with an equal volume of PBS (i.p.). The mice in the control group received PBS solution. Five mice in each group were killed on the 7th, 14th, and 35th days after infection with T. spiralis by cervical dislocation. The blood samples were placed in a sterile Eppendorf tube for 1 h at 37°C and stored overnight in a 4°C refrigerator. Serum was obtained by centrifuging the Eppendorf tube at 3,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Single-cell suspensions of the SPL or MLN were analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described (36). The small intestinal and masseter muscles were extracted as pathological sections to detect inflammation. Western blotting was utilized to detect changes in NLRP3 protein levels.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

The production of IgG1, IgG2, IL-1β, and IL-18 in the serum of infected mice was determined in the control group, T. spiralis group, and T. spiralis plus MCC950 group at 7, 14, and 35 dpi. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Abcam) were used.

Western blot analysis.

The mall intestine was pulverized using a mortar and pestle in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Thermo Scientific). The protein concentration of the extracts was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Total protein was resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membrane was blocked in TBST (10 mM Tris HCl, 0.15 M NaCl containing 0.05% Tween 20) with 5% nonfat skim milk for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and incubated with the corresponding primary antibody at 4°C overnight. After washing for 10 min with TBST three times, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h and washed again. Bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) chromogenic reagent. The primary antibodies used were anti-NLRP3 (Abcam; 1:2,000 dilution) and anti-mouse β-actin (Proteintech; 1:2,000 dilution). Quantification of band intensity was performed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The results were normalized to β-actin protein levels and are expressed as fold changes over the T. spiralis group and T. spiralis plus MCC950 group.

Flow cytometry.

The relative ratios of IL-4 and IFN-γ on CD3+ CD4+ T cells in the SPL and MLN were analyzed by flow cytometry. Single-cell suspensions of the SPL and MLN of all groups of mice were prepared as previously described (24) at days 7, 14, and 35 after infection. Briefly, single cells were counted and seeded in 48-well plates at 2.0 × 106 cells/well in 500 μL RPMI 1640 medium (100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 10% heat-inactivated FBS) containing ionomycin (1 μg/mL), Golgi plug (10 μg/mL), and phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; 20 ng/mL) and were then incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 6 h. After treatment, the cells were collected into Eppendorf tubes by centrifugation (2,000 relative centrifugal force [rcf] for 5 min at 4°C) and discarded from the supernatant.

Harvested cells were resuspended in 100 μL of cold PBS, and Zombie NIR fixable viability kit (BioLegend) was used to exclude cell debris and dead cells. After blocking Fc receptors with anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (BD Biosciences), cells were stained with anti-mouse CD45 (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]; BD Biosciences), anti-mouse CD3 (catalog no. AF700; BD Biosciences), and anti-mouse CD4 (catalog no. PerCP-CY5.5; BD Biosciences) at 4°C for 30 min in the dark. After staining for cell surface markers, the cells were fixed and permeabilized with a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) following the manufacturer’s instructions and washed two times with 500 μL of cold BD Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences). Cells were stained with anti-mouse IL-4 (allophycocyanin [APC]; BD Biosciences) and anti-mouse IFN-γ (phycoerythrin [PE]; BD Biosciences) was performed at 4°C for 30 min in the dark. The transcription factor buffer set kit (BD Pharmingen) was used for intranuclear protein staining for detecting GATA3 (PE-Cy7; BD Biosciences) and T-bet (PE; BD Biosciences) expression. Following this, all stained cells were washed three times with cold PBS to remove unbound antibodies, suspended in 300 μL of PBS, and then examined using an LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (version 7.6.1; TreeStar Inc., USA).

Histopathological evaluation and immunofluorescence.

At 7, 14, and 35 dpi, lingual muscle and small intestine samples were obtained from each group and fixed in 4% formalin for 48 h. The tissue was subjected to washing, dehydrated in gradual ethanol (70 to 100%), made transparent with xylene, processed, embedded with paraffin wax, sliced (3 μm), placed in warm water (42°C) for spreading, collected using slides, baked, and prepared into paraffin tissue sections. The tissue slices were baked at 80°C for 1 h and placed in xylene for 8 min twice. For histopathological evaluation, the sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and visualized with a microscope (Leica). The number of goblet cells per 10 randomly selected villus-crypt units (VCU) was determined by microscopy from at least two sections per animal as previously described (37). Twenty nonoverlapping representative fields of the tissue were examined microscopically using a 400× objective, and the number of inflammatory cells infiltrating the masseter muscle was observed (38).

Bone marrow-derived macrophage isolation, culture, and stimulation.

Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were generated from 5-week-old BALB/c mice as previously described (39). In the in vitro experiments, the BMDMs were randomly divided into the PBS-negative control, ATP-positive control, adult protein group, newborn larvae group, muscle larvae protein group, and MCC950 group. ELISA was used to detect changes in IL-18 and IL-1β levels, and indirect immunofluorescence was used to detect the expression of NLRP3.

BMDMs were primed with LPS for 3 h and then treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Beyotime) or DMSO plus MCC950 (7.5 nm/mL) for 30 min, followed by stimulation with T. spiralis protein (50 mg/mL) of newborn larvae(NLP), muscle larvae (MLP), and adult stages (AP) for 6 h. Protein extraction was performed as previously described (40). After treatment, the BMDMs were washed with PBS, fixed with 80% cold acetone for 30 min at RT, and then washed three times with PBS. After blocking with 3% BSA in PBS for 30 min at RT, the BMDMs were incubated with an antibody against NLRP3 (Sigma) for 1 h at 4°C. After washing with PBST, the BMDMs were incubated with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 [green]; Proteintech) for 40 min at RT. After washing, nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (blue; Sigma) for 10 min in the dark. Imaging analysis was performed using a fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analysis.

Data were statistically analyzed by using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to analyze normality. For comparisons of only two groups, data were analyzed using Student's t test, while for comparisons of three or more groups, we performed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test as indicated. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for nonnormally distributed data. The statistically significant differences between the means are indicated by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). Statistical data are expressed as the mean value ± standard deviation (SD).

Animal welfare statement.

The animal experimental procedures were performed on the basis of the regulations of the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals in China. All animal experiments in this study were approved by the constitution of the Experimental Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Jilin Agricultural University.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32072888, 31941018, and U21A20261) and the Science and Technology Development Program of Jilin Province (20220202057NC, 20210101041JC, YDZJ202102CXJD029, 20190301042NY).

Gui-Lian Yang and Chun-Feng Wang conceived and designed the experiments. Tian-Xu Pan, Hai-Bin Huang, Hui-Nan Lu, Yu Quan, Jun-Yi Li, Ying Xue, Zhi-Yu Zhu, Yue Wang, Chun-Wei Shi, and Nan Wang carried out the research and performed data processing and analyses. Tian-Xu Pan and Hai-Bin Huang Guang-Xun Zhao performed the statistical analysis. Tian-Xu Pan drafted the manuscript with input from all other authors. Tian-Xu Pan and Hui-Nan Lu revised the review. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Gui-Lian Yang, Email: yangguilian@jlau.edu.cn.

Chun-Feng Wang, Email: wangchunfeng@jlau.edu.cn.

De’Broski R. Herbert, University of Pennsylvania

REFERENCES

- 1.Gu Y, Sun X, Huang J, Zhan B, Zhu X. 2020. A multiple antigen peptide vaccine containing CD4+ T cell epitopes enhances humoral immunity against Trichinella spiralis infection in mice. J Immunol Res 2020:2074803–2074814. 10.1155/2020/2074803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long S, Wang Z, Liu R, Liu L, Li L, Jiang P, Zhang X, Zhang Z, Shi H, Cui J. 2014. Molecular identification of Trichinella spiralis nudix hydrolase and its induced protective immunity against trichinellosis in BALB/c mice. Parasit Vectors 7:600. 10.1186/s13071-014-0600-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z, Hao C, Huang J, Zhuang Q, Zhan B, Zhu X. 2018. Mapping of the complement C1q binding site on Trichinella spiralis paramyosin. Parasit Vectors 11:666. 10.1186/s13071-018-3258-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pratesi F, Bongiorni F, Kociecka W, Migliorini P, Bruschi F. 2006. Heart- and skeletal muscle-specific antigens recognized by trichinellosis patient sera. Parasite Immunology 28:447–451. 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu J, Shi G, Fan Y, Choi I, Cha G, Zhou Y, Lee Y, Quan J. 2016. Production of IL-1β and inflammasome with up-regulated expressions of NOD-like receptor related genes in Toxoplasma gondii-infected THP-1 macrophages. Korean J Parasitol 54:711–717. 10.3347/kjp.2016.54.6.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quan J, Huang R, Wang Z, Huang S, Choi I, Zhou Y, Lee Y, Chu J. 2018. P2X7 receptor mediates NLRP3-dependent IL-1β secretion and parasite proliferation in Toxoplasma gondii-infected human small intestinal epithelial cells. Parasit Vectors 11:1. 10.1186/s13071-017-2573-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Almeida R, Clendenon S, Richards W, Boedigheimer M, Damore M, Rossetti S, Harris P, Herbert B, Xu W, Wandinger-Ness A, Ward H, Glazier J, Bacallao R. 2016. Transcriptome analysis reveals manifold mechanisms of cyst development in ADPKD. Hum Genomics 10:37. 10.1186/s40246-016-0095-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du RH, Tan J, Sun XY, Lu M, Ding JH, Hu G. 2016. Fluoxetine inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation: implication in depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 37:pyw037. 10.1093/ijnp/pyw037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Gong P, Zhang X, Wang J, Tai L. 2017. NLRP3 inflammasome activation in murine macrophages caused by Neospora caninum infection. Parasit Vectors 10:266. 10.1186/s13071-017-2197-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abreu MSAC, Coutinho A-d-S, Prado RT, Costa RGD, Maria B, Simões ZD, Claudia VR, Robson CS. 2017. The P2X7 receptor mediates Toxoplasma gondii control in macrophages through canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation and reactive oxygen species production. Front Immunol 8:1257. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chenery A, Alhallaf R, Agha Z, Ajendra J, Parkinson J, Cooper M, Chan B, Eichenberger R, Dent L, Robertson A, Kupz A, Brough D, Loukas A, Sutherland T, Allen J, Giacomin P. 2019. Inflammasome-independent role for NLRP3 in controlling innate antihelminth immunity and tissue repair in the lung. J Immunology 203:2724–2734. 10.4049/jimmunol.1900640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aranzamendi C, Sofronic-Milosavljevic L, Pinelli E. 2013. Helminths: immunoregulation and inflammatory diseases-which side are trichinella spp. and Toxocara spp. on? J Parasitol Res 2013:329438. 10.1155/2013/329438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sofronic-Milosavljevic L, Ilic N, Pinelli E, Gruden-Movsesijan A. 2015. Secretory products of Trichinella spiralis muscle larvae and immunomodulation: implication for autoimmune diseases, allergies, and malignancies. J Immunol Res 2015:523875. 10.1155/2015/523875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosmann TR. 1991. Cytokine secretion patterns and cross-regulation of T cell subsets. Immunol Res 10:183–188. 10.1007/BF02919690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maizels RM, Gause WC. 2014. How helminths go viral. Science 345:517–518. 10.1126/science.1258443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tymoshok NO, Lazarenko LM, Bubnov RV, Shynkarenko LN, Babenko LP, Mokrozub VV, Melnichenko YA, Spivak M. 2014. New aspects the regulation of immune response through balance Th1/Th2 cytokines. EPMA J 36:A134. 10.1186/1878-5085-5-S1-A134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu Y, Wei J, Yang J, Huang J, Yang X, Zhu X. 2013. Protective immunity against Trichinella spiralis infection induced by a multi-epitope vaccine in a murine model. PLoS One 8:e77238. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Werf N, Redpath S, Azuma M, Yagita H, Taylor M. 2013. Th2 cell-intrinsic hypo-responsiveness determines susceptibility to helminth infection. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003215. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin X, Bai X, Yang Y, Ding J, Shi H, Fu B, Boireau P, Liu M, Liu X. 2020. NLRP3 played a role in Trichinella spiralis-triggered Th2 and regulatory T cells response. Veterinary Res 51:107. 10.1186/s13567-020-00829-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva G, Costa R, Silveira T, Caetano B, Horta C, Gutierrez F, Guedes P, Andrade W, De Niz M, Gazzinelli R, Zamboni D, Silva J. 2013. Apoptosis-associated speck–like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain inflammasomes mediate IL-1β response and host resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Immunology 191:3373–3383. 10.4049/jimmunol.1203293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruchard M, Rebé C, Derangère V, Togbé D, Ryffel B, Boidot R, Humblin E, Hamman A, Chalmin F, Berger H, Chevriaux A, Limagne E, Apetoh L, Végran F, Ghiringhelli F. 2015. The receptor NLRP3 is a transcriptional regulator of TH2 differentiation. Nat Immunol 16:859–870. 10.1038/ni.3202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlaeger J, Cai H, Steffen A, Angulo V, Shroff A, Briller J, Hoppensteadt D, Uwizeye G, Pauls H, Takayama M, Yajima H, Takakura N, DeVon H. 2019. Acupuncture to improve symptoms for stable angina: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 8:e14705. 10.2196/14705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang T, Kawakami K, Qureshi MH, Okamura H, Kurimoto M, Saito A. 1997. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-18 synergistically induce the fungicidal activity of murine peritoneal exudate cells against Cryptococcus neoformans through production of gamma interferon by natural killer cells. Infect Immun 65:3594–3599. 10.1128/iai.65.9.3594-3599.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Besnard A, Guillou N, Tschopp J, Erard F, Couillin I, Iwakura Y, Quesniaux V, Ryffel B, Togbe D. 2011. NLRP3 inflammasome is required in murine asthma in the absence of aluminum adjuvant. Allergy 66:1047–1057. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helmby H, Grencis RK. 2004. Interleukin 1 plays a major role in the development of Th2-mediated immunity. Eur J Immunol 34:3674–3681. 10.1002/eji.200425452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciraci C, Janczy JR, Sutterwala FS, Cassel SL. 2012. Control of innate and adaptive immunity by the inflammasome. Microbes Infect 14:1263–1270. 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia X, Li X, Shen Y, Miao J, Liu H, Li G, Wang Z. 2016. MiR-16 regulates mouse peritoneal macrophage polarization and affects T-cell activation. J Cell Mol Med 20:1898–1907. 10.1111/jcmm.12882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu F, Liu X, Sun Z, Yu C, Liu L, Yang S, Li B, Wei K, Zhu R. 2016. Immune-enhancing effects of Taishan Pinus massoniana pollen polysaccharides on DNA vaccine expressing Bordetella avium ompA. Front Microbiol 7:66. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finkelman FD, Shea-Donohue T, Morris SC, Gildea L, Strait R, Madden KB, Schopf L, Urban JF Jr. 2004. Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated host protection against intestinal nematode parasites. Immunol Rev 201:139–155. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C, Yang C, Tsai Y, Liaw C, Chang W, Hwang T. 2017. Ugonin U stimulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation and enhances inflammasome-mediated pathogen clearance. Redox Biol 11:263–274. 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruschi F, Chiumiento L. 2011. Trichinella inflammatory myopathy: host or parasite strategy? Parasit Vectors 4:42. 10.1186/1756-3305-4-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lafuse W, Wozniak D, Rajaram M. 2020. Role of cardiac macrophages on cardiac inflammation, fibrosis and tissue repair. Cells 10:51. 10.3390/cells10010051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alhallaf R, Agha Z, Miller CM, Robertson AAB, Sotillo J, Croese J, Cooper MA, Masters SL, Kupz A, Smith NC, Loukas A, Giacomin PR. 2018. The NLRP3 inflammasome suppresses protective immunity to gastrointestinal helminth infection. Cell Rep 23:1085–1098. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Gong P, Zhang X, Li S, Lu X, Zhao C, Yu Q, Wei Z, Yang Y, Liu Q, Yang Z, Li J, Zhang X. 2018. Neospora caninumNLRP3 inflammasome participates in host response to infection. Front Immunol 9:1791–1805. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Despommier D, Campbell W, Blair L. 1977. The in vivo and in vitro analysis of immunity to Trichinella spiralis in mice and rats. Parasitology 74:109–119. 10.1017/s0031182000047570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang H, Yang W, Hu J, Jiang Y, Wang J, Shi C, Kang Y, Wang D, Wang C, Yang G. 2021. Antitumour metastasis and the antiangiogenic and antitumour effects of a Eimeria stiedae soluble protein. Parasite Immunol 43:e12825. 10.1111/pim.12825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu Y-R, Liu X-C, Zhang J-S, Ji C-Y, Qi Y-F. 2013. Taurine drinking attenuates the burden of intestinal adult worms and muscle larvae in mice with Trichinella spiralis infection. Parasitol Res 112:3457–3463. 10.1007/s00436-013-3525-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mi-Kyung P, Yun-Jeong K, Jin-Ok J, Kyung-Wan B, Hak-Sun Y, Hyun CY, Hee-Jae C, Sun OM. 2018. Effect of muscle strength by Trichinella spiralis infection during chronic phase. Int J Med Sci 15:802–807. 10.7150/ijms.23497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugata R, Sebastian S, Erik A, Tanvir A, Parihar SP, Mumin O, Ousman T, Hideya K, Michiel JL, de H, Masayoshi I. 2015. Redefining the transcriptional regulatory dynamics of classically and alternatively activated macrophages by deepCAGE transcriptomics. Nucleic Acids Res 43:6969–6982. 10.1093/nar/gkv646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wranicz MJ, Gustowska L, Gabryel P, Kucharska E, Cabaj W. 1998. Trichinella spiralis: induction of the basophilic transformation of muscle cells by synchronous newborn larvae. Parasitol Res 84:403–407. 10.1007/s004360050418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]