Abstract

Background:

We hypothesized that cumulative anesthesia exposure over the course of routine treatment of colorectal cancer in older adults can increase long-term risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias (ADRD), and other chronic neurocognitive disorders (CND).

Methods:

We conducted a SEER-Medicare-based retrospective cohort study of 84,770 individuals age 65 years and older diagnosed with colorectal cancer between 1998 and 2007 using a proportional hazards model with inverse probability weighted estimators. The primary exploratory variable was a time-variant measure of cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures, updated continuously.

Results:

Our primary outcomes, AD and ADRD, occurred in 6005/84,770 (7.1%) and 14,414/83,444 (17.3%) individuals respectively. No statistically significant association was found between cumulative anesthesia exposure and AD (hazard ratio [HR], 0.993; 95% CI, 0.973–1.013). However, it was moderately associated with the risk of ADRD (HR, 1.016; 95% CI, 1.004–1.029) and some secondary outcomes including most notably: cerebral degeneration (HR, 1.048; 95% CI, 1.033–1.063), hepatic encephalopathy (HR, 1.133; 95% CI, 1.101–1.167), encephalopathy–not elsewhere classified (HR,1.095; 95% CI: 1.076–1.115), and incident/perioperative delirium (HR, 1.022; 95% CI, 1.012–1.032). Furthermore, we observed an association between perioperative delirium and increased risk of AD (HR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.92–2.09).

Conclusion:

Cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures was not associated with increased risk of AD directly and had a small but statistically significant association with ADRD and a number of other CNDs. Cumulative anesthesia exposure was also associated with perioperative delirium, which had an independent adverse association with AD risk.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Dementia, Anesthesia, Colorectal cancer, Surgery

1. Introduction

Anesthesia combined with surgery, alone or in combination with predisposing factors, is a well-described risk factor for perioperative neurocognitive disorders (Mahanna-Gabrielli et al., 2019). Less clear is the potential role of cumulative anesthesia exposure in the development over time of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias (ADRD), and other chronic neurocognitive disorders (CNDs). There is lack of consensus on the presence of an association between anesthesia exposure for surgical procedures and dementia (Chen et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2017a; Jiang et al., 2017b; Sprung et al., 2013), with existing literature highlighting potential challenges to the conduct of such studies, including longitudinal tracking of cognitive changes sufficient to meet the criteria for a diagnosis of dementia, measuring the effect of cumulative anesthesia exposure for surgical procedures over time, and accounting for the role of comorbidities and treatment modalities that necessitated the surgical procedure (Eckenhoff and Laudansky, 2013; Ehlenbach et al., 2010; Vega et al., 2017).

Colorectal cancer is the third most prevalent cancer for both elderly men and women in the U.S. (American Cancer Society, 2017), and its mortality rate has continued to decline over the last three decades, allowing affected individuals to live longer and reach ages at which onset of AD, for which age is the most important non-genetic risk factor, is common. Guidance concordant care for colorectal cancer often involves one or more surgical procedures and multiple exposures to different anesthetic agents. These characteristics provide an ideal population of individuals for the study of the potential impact of cumulative exposure to anesthesia over the course of guidance concordant care for colorectal cancer in elderly individuals on the short- and long-term risk of AD, ADRD, and select other CNDs, which is the purpose of this study.

2. Methods

This study was approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (Durham, NC); informed consent was waived given the retrospective nature of the study.

2.1. Study population

The data was drawn from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program linked to administrative health insurance claims records from the Medicare program (SEER-Medicare) (Warren et al., 2002). SEER-Medicare provides data on the date of diagnosis, histology, stage, and grade for 10 types of cancer, follow-up vital status, cause of death (if applicable), and basic demographic and area-based socioeconomic characteristics. The Medicare component provides additional information on the diagnoses made (International Classification of Disease 9th Edition, Clinical Modification [ICD-9]) and procedures performed (Current Procedural Terminology 4th Edition [CPT-4]) on all episodes of care paid for by Medicare Parts A and B on a fee-for-service (FFS) basis.

In the present study, we selected individuals who were diagnosed with colorectal cancer between 1998 and 2007. The initial sample size was 287,967 persons. We excluded individuals without reliable anesthesia-related data (121,835); without full fee-for-service Medicare Parts A and B coverage 12 months before and 6 months after diagnosis (20,866); who died within 6 months of diagnosis (15,088); who had AD/ADRD/CND at baseline (13,573); and with incomplete data for socioeconomic status (202), cancer stage (4292), and/or no evidence of anesthesia for abdominal and pelvic procedures within 1 year of diagnosis (27,323). The final sample size was 84,770 individuals.

2.2. Definition of cumulative anesthesia exposure and clinical risk factors

Cumulative anesthesia exposure for surgery was identified (Silber et al., 2007) by the presence of anesthesia services provided by a physician/anesthesiologist (Specialty Code 05) billing code for a non-zero number of anesthesia time units (Miles, Times, Units & Services indicator of 02). Claims associated with a zero (not paid/erroneous claim) or negative (refund to Medicare from previous erroneous claim) amount were excluded to avoid double-counting anesthesia times. Medicare requires that anesthesia times be reported in 15-minute units. For this study, these were converted into a continuous measure representing anesthesia hours. This measure was time dependent and accumulated over time as new qualifying claims for anesthesia encounters appeared in an individual’s Medicare record. The resulting aggregate measure of anesthesia exposure was then split into our primary measure of interest—anesthesia for abdominal and pelvic procedures (CPT-4:00700–00882, 01112–01190)––and 9 other types of anesthesia for other surgical procedures. These were i) head/neck (CPT-4:00100–00352); ii) thorax/intrathoracic (CPT-4:00400–00580); iii) spine/spinal cord (CPT-4:00600–00670); iv) leg/knee (CPT-4:01200–01522); v) shoulder/arm (CPT-4:01610–01860); vi) radiological (CPT-4:01916–01936); vii) excision/debridement (CPT-4:01951–01953); viii) obstetric (CPT-4:01958–01969); and ix) other (CPT-4:01990–01999). The value of each variable increased when a qualifying anesthesia case was detected in Medicare records. Cumulative anesthesia exposure was evaluated in 2 ways: i) at baseline (time-independent) using a 5-year lookback period and ii) over the follow-up period accruing from a baseline value of zero (time-dependent). This design was considered reasonable as empirically, duration of anesthesia exposure prior to diagnosis of colorectal cancer was zero or minimal for the overwhelming majority of the individuals with exposure starting to increase after colorectal cancer diagnosis as the individuals progressed through their prescribed guidance concordant care regimens.

2.3. Study outcomes

The study’s primary outcome was onset of AD and ADRD (Matthews et al., 2019). The Medicare ascertainment algorithm used to identify the presence of AD/ADRD and all Medicare-based diseases utilized in the study has been described in detail elsewhere (Akushevich et al., 2016; Akushevich et al., 2012; Akushevich et al., 2018). Since cancer treatment-related cognitive decline does not need to reach the level of an AD/ADRD diagnosis for there to be clinically meaningful decrements in cognitive function, and there is the possibility of other dementia diagnoses appearing as precursors to AD/ADRD onset as well as the presence of multiple dementias in a single individual, we also considered the onset of multiple secondary high-prevalence CNDs (Akushevich et al., 2018) – non-psychotic mental disorders, cognitive deficits (late effects), and encephalopathy – as well as a composite measure representing the onset of any conditions included in this study, referred to as “all chronic neurocognitive disorders”. Finally, to account for the known association between anesthesia exposure, perioperative delirium (POD; delirium occurring within 1 year of colorectal cancer surgery) and the onset of AD/ADRD in later life (Eckenhoff et al., 2020), we explored the risks associated with the following progression: i) effect of anesthesia exposure on POD, followed by ii) effect of POD on long-term risk of AD/ADRD onset.

2.4. Statistical analysis

To account for heterogeneity between individuals with high/low levels of anesthesia exposure, we calculated individual inverse-probability weights (IPW) as the reciprocal of the probability of having exposure to anesthesia. This results in a weighted population equalized with respect to all predictors used in the treatment model, which ensures that groups with high/low anesthesia exposures identified in our sample contain no statistically significant differences with respect to these variables (i.e. the groups would differ only by anesthesia status). Since anesthesia exposure was a time-dependent continuous variable, for the purposes of the pseudorandomization model, we defined high exposure as above median (3 h) exposure to anesthesia for abdominal and pelvic procedures within 1-year of colorectal cancer diagnosis. Supplementary Table S1 provides summary statistics, significance, and pseudo-randomization quality testing for all variables involved in pseudo-randomizing the treatment groups while Supplementary Table S2 shows the sample sizes and numbers of cases for each outcome-specific model. All co-morbidities utilized in the PSM model were measured at baseline (i.e. date of colorectal cancer diagnosis) using a 12-month look-back period.

We used univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models for the analysis. Individual follow-up started at the date of colorectal cancer diagnosis. Age was included as a time-scale variable in order to account for its effects nonparametrically. Such models are preferable when age is a strong predictor of the outcome (Canchola et al., 2003; Korn et al., 1997) as is our case with AD/ADRD/CND. Age at onset is included as a technical predictor in all models. A stepwise variable selection was used for multivariable analyses. All hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of anesthesia exposure were calculated in 3-hour increments.

Stability of the results was tested by comparing estimates of the effects of cumulative anesthesia exposure between models with/without: i) pseudorandomization; ii) univariable (adjusted for age at baseline) and multivariable (adjusted for demographic and clinical risk factors) specifications; iii) use of alternative claim ascertainment algorithms (e. g. analysis was repeated using alternative verification periods including: a) without confirmation; b) 90 days; c) 180 days; d) 365 days; and e) 730 days with death over this period treated as a confirmatory record); iv) restriction of anesthesia exposure instances to those of 60 min or longer; v) inclusion of SEER-Registries to assess the possibility of registry-specific effects; vi) adjustments for possible misspecifications in anesthesia records (e.g. reports of 1 and 10 anesthesia units can be used interchangeably due to differences in adherence to reporting standards; surgeries with abnormal durations of 400 min or more); vii) analysis of effect variation in race and sex-specific subgroups; and viii) testing the bounds of the possible effect due to dependence between risks of death and AD using the Fine-Gray competing risk model (Fine and Gray, 1999) with death as the competing risk or by equating all instances of death with simultaneous AD onset. The variations in results were all within the confidence interval of the model reported in this study. The assumption of proportional hazards was satisfied.

All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3. Results

Table 1 shows the summary statistics for the study population and sample subgroups characterized by follow-up outcome information and stage at diagnosis. Trajectories of cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures and four frequently occurring surgical exposure categories are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 while Supplementary Fig. S2 shows the dynamics of the accumulation of total cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic surgical procedures by outcome and cancer stage groups. Although individual cumulative anesthesia exposure for different surgical interventions cannot decline, the mean of this measure decreases with time for groups with higher mortality or censoring probability.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population for the Alzheimer’s disease model.

| Total | Survival status | Cancer stage at diagnosis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s Disease within 60 months of cancer diagnosis | Alzheimer’s disease at 60+ months of cancer diagnosis | Censoreda | Death | In situ | Localized | Regional | Distant | ||

| Panel A. Total and group-specific sample sizes | |||||||||

| N | 84,770 | 3,179 | 2826 | 47,718 | 31,047 | 3174 | 37,302 | 35,161 | 9,133 |

| % of Total | 100 | 3.75 | 3.33 | 56.29 | 36.62 | 3.74 | 44.00 | 41.48 | 10.77 |

| Panel B. Continuous variables: mean (standard deviation) | |||||||||

| Age at diagnosis | 77.04 | 80.68 | 77.82 | 76.00 | 78.21 | 76.14 | 77.17 | 77.22 | 76.13 |

| (6.69) | (6.31) | (6.03) | (6.29) | (7.03) | (6.35) | (6.65) | (6.76) | (6.56) | |

| Follow-up time | 4.77 | 2.52 | 8.51 | 6.38 | 2.18 | 5.32 | 5.41 | 4.69 | 2.22 |

| (3.64) | (1.39) | (2.78) | (3.72) | (1.24) | (3.54) | (3.68) | (3.60) | (2.23) | |

| Panel C. Binary variables: percent | |||||||||

| Cancer Stage at Diagnosis | |||||||||

| In situ | 3.74 | 4.62 | 4.32 | 4.70 | 2.13 | ||||

| Localized | 44.00 | 50.36 | 52.62 | 52.61 | 29.34 | ||||

| Regional | 41.48 | 39.48 | 40.94 | 39.36 | 44.99 | ||||

| Distant | 10.77 | 5.54 | 2.12 | 3.33 | 23.54 | ||||

| Geographic Region | |||||||||

| Midwest | 19.79 | 18.72 | 25.94 | 18.51 | 21.32 | 13.42 | 19.78 | 20.06 | 21.03 |

| Northeast | 25.54 | 30.07 | 23.11 | 25.93 | 24.71 | 41.90 | 25.63 | 24.41 | 23.85 |

| South | 11.18 | 14.25 | 9.31 | 11.43 | 10.66 | 13.11 | 11.28 | 10.99 | 10.85 |

| West | 43.48 | 36.96 | 41.65 | 44.13 | 43.31 | 31.57 | 43.31 | 44.54 | 44.27 |

| Other Demographics | |||||||||

| Female | 52.80 | 57.00 | 62.38 | 53.58 | 50.29 | 49.02 | 52.23 | 54.15 | 51.22 |

| Non-white | 6.71 | 8.08 | 7.50 | 5.99 | 7.60 | 9.64 | 6.15 | 6.60 | 8.40 |

| Rural | 11.83 | 10.00 | 9.87 | 11.93 | 12.04 | 10.65 | 11.85 | 11.88 | 11.97 |

| Baseline Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Other ischemic heart disease | 41.32 | 48.54 | 37.33 | 38.65 | 45.05 | 43.79 | 42.68 | 41.13 | 35.63 |

| Heart failure | 22.89 | 29.60 | 16.77 | 17.71 | 30.74 | 21.90 | 23.25 | 23.36 | 20.02 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (stroke) | 16.85 | 25.92 | 14.26 | 14.93 | 19.10 | 17.93 | 17.57 | 16.66 | 14.26 |

| Cerebrovascular disease with complications | 4.14 | 6.48 | 3.33 | 3.11 | 5.57 | 4.10 | 4.18 | 4.35 | 3.20 |

| Lung cancer | 2.74 | 2.49 | 1.56 | 1.86 | 4.22 | 1.83 | 2.24 | 2.57 | 5.75 |

| Pulmonary heart disease | 9.36 | 11.67 | 6.44 | 7.58 | 12.14 | 8.41 | 9.19 | 9.61 | 9.43 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 1.12 | 3.46 | 1.49 | 0.70 | 1.49 | 1.17 | 1.12 | 1.17 | 0.91 |

| Depression | 8.24 | 15.19 | 7.68 | 7.37 | 8.93 | 7.81 | 8.25 | 8.46 | 7.54 |

| Alcohol abuse | 2.12 | 2.49 | 1.49 | 1.85 | 2.56 | 2.24 | 2.15 | 1.96 | 2.62 |

| Drug and/or medication abuse | 0.86 | 2.36 | 1.03 | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.79 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.80 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 28.16 | 30.83 | 22.47 | 27.34 | 29.67 | 29.43 | 28.77 | 27.83 | 26.52 |

| Electrolyte disturbances | 32.71 | 37.65 | 29.02 | 28.71 | 38.67 | 27.06 | 30.56 | 34.32 | 37.21 |

| Septicemia | 5.03 | 6.45 | 3.50 | 3.62 | 7.18 | 3.65 | 4.51 | 5.33 | 6.45 |

| Anemia | 64.63 | 72.32 | 59.16 | 61.02 | 69.88 | 52.68 | 61.28 | 68.29 | 68.33 |

| Upper and/or lower limb fracture | 18.02 | 21.67 | 15.11 | 18.47 | 17.22 | 19.66 | 18.91 | 17.47 | 15.94 |

| Weight deficiency | 17.19 | 22.18 | 12.38 | 13.79 | 22.35 | 13.01 | 14.35 | 18.73 | 24.31 |

Censored: censoring or death at 5+ years of cancer diagnosis; death: death within 60 months of cancer diagnosis.

The results of our analysis (Table 2) indicated that there was no significant association between total time-dependent cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures and AD (HR, 0.993; CI, 0.993–1.012). This effect was consistent with the estimates of both univariable (HR, 0.995; CI, 0.976–1.015) and multivariable (HR, 0.989; CI, 0.969–1.009) analysis conducted without pseudorandomization.

Table 2.

Effects of cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures on study outcomes.

| Primary pseudorandomized analysis | Non-pseudorandomized sensitivity analyses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Univariablea | Multivariable | |||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |||

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | 0.993 (0.973, 1.013) | 0.481 | 0.995 (0.976, 1.015) | 0.620 | 0.989 (0.969, 1.009) | 0.279 |

| Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia, AD excluded (ADRD) | 1.016 (1.004, 1.029) | 0.009 | 1.019 (1.007, 1.032) | 0.002 | 1.007 (0.994, 1.020) | 0.282 |

| All chronic neurocognitive disorders (NCD) | 1.020 (1.010, 1.030) | <0.001 | 1.029 (1.020, 1.038) | <0.001 | 1.005 (0.995, 1.014) | 0.321 |

| Dementia permanent mental disorder | 1.020 (1.006, 1.035) | 0.004 | 1.023 (1.009, 1.037) | 0.001 | 1.012 (0.998, 1.026) | 0.107 |

| Dementia (senile) | 1.018 (1.001, 1.034) | 0.038 | 1.016 (1.000, 1.033) | 0.050 | 1.008 (0.991, 1.025) | 0.364 |

| Vascular dementia | 0.991 (0.962, 1.021) | 0.554 | 0.997 (0.969, 1.026) | 0.852 | 0.986 (0.957, 1.016) | 0.344 |

| Non-psychotic mental disorders | 0.988 (0.956, 1.021) | 0.478 | 0.992 (0.961, 1.024) | 0.624 | 0.983 (0.951, 1.016) | 0.297 |

| Cerebral degeneration, excluding Alzheimer’s disease | 1.048 (1.033, 1.063) | <0.001 | 1.058 (1.044, 1.072) | <0.001 | 1.038 (1.024, 1.053) | <0.001 |

| Cognitive deficits (late effects) | 1.027 (1.004, 1.051) | 0.020 | 1.036 (1.014, 1.059) | 0.001 | 1.007 (0.985, 1.030) | 0.528 |

| Encephalopathy | 1.095 (1.076, 1.115) | <0.001 | 1.102 (1.085, 1.120) | <0.001 | 1.055 (1.037, 1.074) | <0.001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1.133 (1.101, 1.167) | <0.001 | 1.136 (1.108, 1.164) | <0.001 | 1.095 (1.061, 1.131) | <0.001 |

| Incident/perioperative delirium | 1.022 (1.012, 1.032) | <0.001 | 1.036 (1.027, 1.046) | <0.001 | 1.003 (0.994, 1.013) | 0.485 |

Univariable analysis was conducted with additional adjustments for baseline age.

Table 2 also presents the estimates of association between the total time-dependent cumulative anesthesia exposure and the hazards for ADRD and CNDs in univariable (with adjustments for age at baseline), pseudorandomized, and multivariable analyses. In general, the effect of cumulative anesthesia exposure on the risk of AD, vascular dementia, and non-psychotic mental disorders, was not significant. For those CNDs for which a significant effect existed, the associated increases in risk were well under 5% per 3 h of additional anesthesia. The exceptions were hepatic encephalopathy (HR, 1.133; CI, 1.101–1.167) and encephalopathy (HR, 1.095; CI, 1.076–1.115). We note that the effect of delirium occurring within one year of cancer diagnosis (i.e. POD) was itself strongly associated with AD (HR, 2.05; CI, 1.92–2.09). So even though the effect of cumulative anesthesia on incident/perioperative was small (HR, 1.022; CI, 1.012–1.032) an additional indirect pathway between anesthesia exposure and AD risk is possible.

Supplementary Table S3 provides the same estimates stratified by sex, race, and cancer diagnoses subgroups.

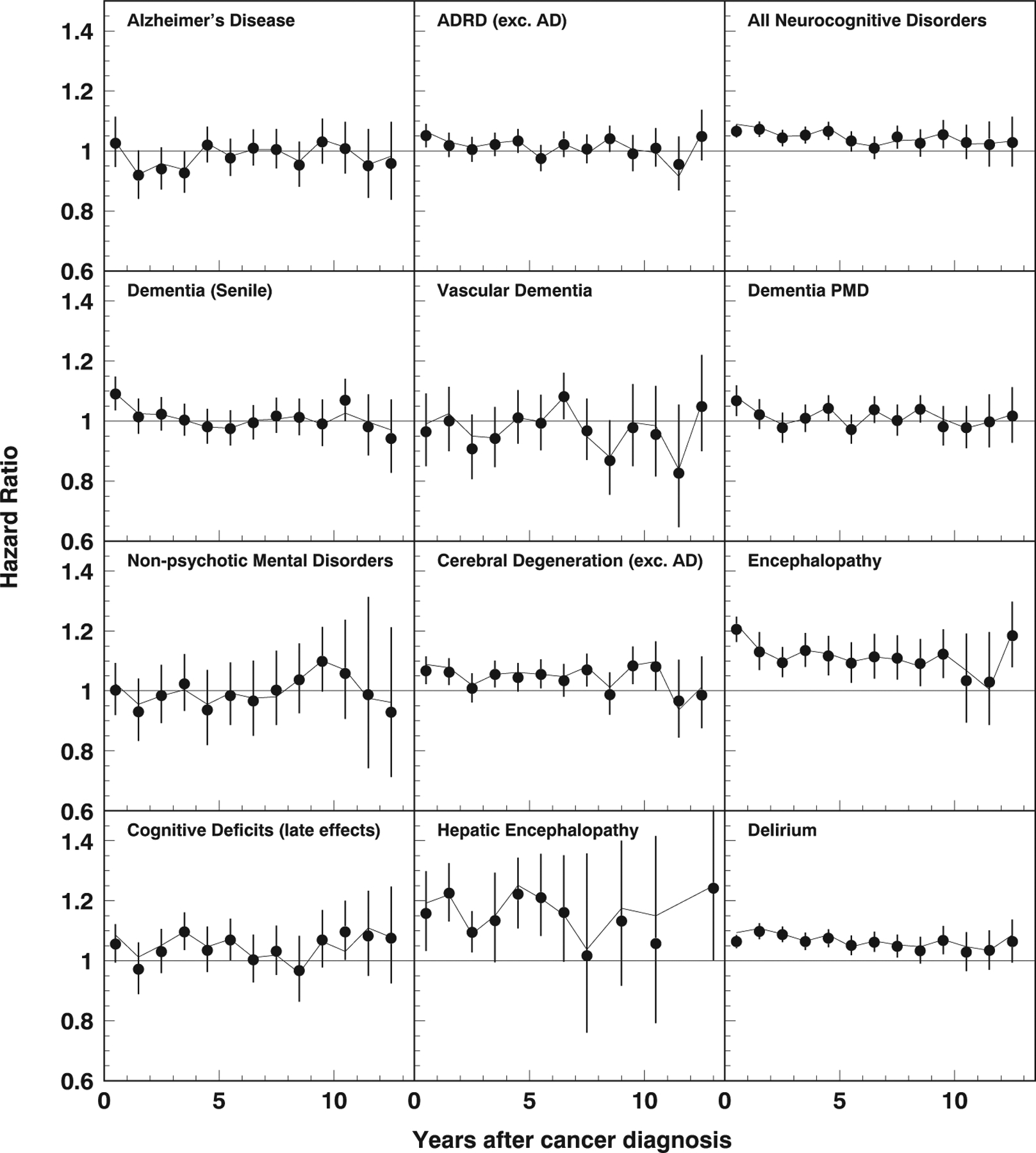

In contrast to Table 2, which shows the effect of anesthesia exposure accumulated over the entire study period, Fig. 1 demonstrates the time patterns of these effects for each year of follow-up after diagnosis (i.e. year one, corresponding to a 1-year follow-up period, year 13, corresponding to a 13-year follow-up, conditional on survival). The findings demonstrate that with the exception of hepatic encephalopathy, encephalopathy, and incident/perioperative delirium, the effects of cumulative anesthesia exposure were short-term, i.e. significant within 0 to 4 years post initial colorectal cancer diagnosis when the impact of other colorectal cancer treatment-related factors was likely also present.

Fig. 1.

Hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) of cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures versus time elapsed after initial colorectal cancer diagnosis. The solid line shows the estimates after pseudorandomization.

4. Discussion

This study of elderly individuals with colorectal cancer demonstrated that, over the course of routine treatment, cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures was not associated with increased long-term risk for AD but was associated with ADRD, especially within one year of cancer diagnosis (likely due to the contribution of cerebral degeneration) after adjusting for population heterogeneity, anesthesia exposure for other surgical procedures, and treatment with chemotherapy, which was found to be associated with lower risk of AD in a recent study (Akushevich et al., 2021). We found no increased risk of AD and ADRD at the 5- and 10-year post-diagnosis marks; however, we observed cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures was associated with a number of CNDs. Specifically, cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures showed an incremental risk for incident/perioperative delirium (without time constraints), cerebral degeneration, hepatic encephalopathy, and encephalopathy–not elsewhere classified. These effects were stable (i.e. did not change direction or lose significance [exception: incident/perioperative delirium in multivariate model without PSM]) across alternative specifications for the outcome model and its input parameters as well as across subgroups of the total sample defined by sex, race, cancer stage at diagnosis, and time since initial colorectal cancer diagnosis.

Our findings support results obtained from a previous meta-analysis (Seitz et al., 2011), a case-control study (Sprung et al., 2013), and a larger-scale cohort study (Aiello Bowles et al., 2016) and allow us to hypothesize that the variations in findings (Aiello Bowles et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2018; Seitz et al., 2011; Sprung et al., 2013) on the direct association between repeated anesthesia exposure and AD are indicative of the association being epiphenomenal in nature and, when present, reflective of individual subject factors or comorbidities rather than the repeated anesthesia exposure itself. Many previous studies focused on exploring the association between anesthesia exposure for surgical procedures (including colorectal procedures) and AD exclusively (Chen et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2017a; Sprung et al., 2013; Velkers et al., 2021). In contrast, our study additionally explored the association between time-varying cumulative anesthesia exposure times for abdominal and pelvic procedures and their potential impact on short-and long-term hazard for a wide range of short- and long-term CNDs. This is an important distinction as establishing the diagnosis of AD is challenging and AD often coexists with or is preceded by the diagnosis of other short- and long-term CNDs. Indeed, studies exploring the association between anesthesia exposure for surgical procedures and short- and long-term CNDs remain sparse. To date, there has been only one prospective study that found that exposure to anesthesia and cardiac surgery was associated with a higher prevalence of dementia compared with population prevalence (Evered et al., 2016). Specifically, in our study, we observed that cumulative anesthesia exposure was associated with a transiently increased hazard for cerebral degeneration (up to 2 years) and hepatic encephalopathy (up to 3 years) after initial colorectal cancer diagnosis, and a persistently increased long-term risk for encephalopathy–not elsewhere classified up to 10 years after initial colorectal cancer diagnosis. Furthermore, we observed that cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures was associated with an elevated risk for POD (i.e. delirium within 1 year of cancer diagnosis) and a persistent long-term risk for incidental delirium.

The observation that cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures was associated with an elevated risk for hepatic encephalopathy in our study highlights the potential role of preexisting chronic hepatocellular disease, abdominal and pelvic surgery, anesthetic medications, and colorectal cancer treatment-related factors such as chemotherapy, precipitating albeit transient factors for impaired hepatocellular function, and an elevated risk for hepatic encephalopathy and cerebral degeneration (Schwendimann and Minagar, 2017). Once the initial or subsequent course of treatment (surgery and/or chemotherapy) for colorectal cancer is completed, the impact of these factors is unlikely to persist in the long-term. However, hepatic-encephalopathy occurred in only a relatively small number of patients and that may have also impacted the strength of observed associations in our study.

The findings that cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic surgery was associated with an elevated risk for POD, and a persistently elevated long-term risk for delirium and encephalopathy–not elsewhere classified are intriguing. Generally, delirium is considered a short-term condition, but it can persist for months and is associated with poor cognitive and functional outcomes (Rudolph and Marcantonio, 2011); furthermore, it can accelerate cognitive decline in all older individuals including those with AD (Fong et al., 2009). Of note, the diagnosis “encephalopathy–not elsewhere classified” is a disorder that can be caused by disease, injury, medications, or chemicals, highlighting the potential role that colorectal cancer treatment-related modalities may play in its development. In our study, we also observed that individuals who developed POD, and encephalopathy–not elsewhere classified after cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures had a significantly higher risk for developing AD. These findings support earlier observations that indicate a potential association between anesthesia exposure for major surgery (e.g., orthopedic surgery), the development of POD or cognitive dysfunction, and the incident risk for dementia in elderly patients (Krogseth et al., 2011; Lundstrom et al., 2003).

It is important to note that other observational studies have been inconclusive in elucidating the relationships between i) exposure to surgery and anesthesia, ii) resulting POD and postoperative cognitive dysfunction, and iii) long-term dementia risk (Mason et al., 2010; Slor et al., 2011; Steinmetz et al., 2013). Therefore, there is a need for further study of both the possibility of a direct relationship between surgery/anesthesia and long-term dementia as well as of possible pathological pathways through increased risk of a mediator condition such as POD or cognitive dysfunction. Our study responds to this need, and has the notable advantages of high statistical power, an extended follow-up period of up to 13 years, and the use of an advanced methodology designed to offset the potential confounding effects of population heterogeneity and selection bias.

However, our study has a number of limitations. Given the type of data used in our study, we were unable to ascertain the severity of AD, ADRD, and other CNDs, and therefore the development of milder forms of cognitive impairment. We could not distinguish between the effect of anesthesia itself and the effect of the surgical procedure that necessitated the anesthetic exposure. Since surgery and anesthesia occurs simultaneously, it is not possible to partition the respective contributions of surgery and anesthesia out of the total effect within the constraints of the available data. The nature of the data precluded us from differentiating between different types of anesthetic procedures, some of which may be associated with a reduced risk or may have a differential effect on AD/ADRD risk. Furthermore, by necessity, our study relied on diagnosis and procedure codes present in administrative claims data. Information on neurocognitive testing or magnetic resonance imaging was not available. Reliance on administrative codes can result in over-, under-, or misreporting of the conditions analyzed in this study due to the difficulty involved in making a valid diagnosis, even at bedside. Finally, there could have been other factors associated with the risk of cognitive decline in our study population not ascertainable in our data, such as those related to underlying cancer treatment (Pendergrass et al., 2018).

5. Conclusion

We did not observe a direct association between cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures and AD, and the positive association with ADRD was minor (1%–2% increased risk), short term (within 1-year of cancer diagnosis) and likely an artifact of the effect of cerebral degeneration. In our study, we also observed a higher short-term risk for cerebral degeneration and hepatic encephalopathy, and a persistently elevated risk for encephalopathy–not elsewhere classified. Importantly, we observed that cumulative anesthesia exposure for abdominal and pelvic procedures was associated with a higher risk for POD, which, in turn, was associated with a higher risk for AD and ADRD. This observation highlights the need to explore the role of mediation effects between anesthesia/surgery exposure, resulting short-term perioperative cognitive outcomes, and their combined effect on long-term risk of AD/ADRD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Yvonne Poindexter, MA, (Editor, Department of Anesthesiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA) for her editorial contributions.

Funding

Publication of this article was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging (grants R01-AG057801, R01-AG066133, and R01-AG046860). The funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Igor Akushevich: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation; Writing - Original draft; Writing - Review & editing; Arseniy P. Yashkin: Methodology, Writing - Original draft; Writing - Review & editing; Julia Kravchenko: Writing - Original draft; Miklos D. Kertai: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Original draft; Writing - Review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2022.111830.

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- Aiello Bowles EJ, Larson EB, Pong RP, Walker RL, Anderson ML, Yu O, Gray SL, Crane PK, Dublin S, 2016. Anesthesia exposure and risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 64, 602–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akushevich I, Kravchenko J, Arbeev KG, Ukraintseva SV, Land KC, Yashin AI, 2016. Health effects and medicare trajectories: population-based analysis of morbidity and mortality patterns. In: Biodemography of Aging. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Akushevich I, Kravchenko J, Ukraintseva S, Arbeev K, Yashin AI, 2012. Age patterns of incidence of geriatric disease in the US elderly population: Medicare-based analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 60, 323–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akushevich I, Yashkin AP, Kravchenko J, Kertai MD, 2021. Chemotherapy and the RISK of Alzheimer’s disease in colorectal cancer survivors: evidence from the Medicare system. JCO Oncol.Pract 20, 00729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akushevich I, Yashkin AP, Kravchenko J, Ukraintseva S, Stallard E, Yashin AI, 2018. Time trends in the prevalence of neurocognitive disorders and cognitive impairment in the United States: the effects of disease severity and improved ascertainment. J. Alzheimers Dis 64, 137–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canchola AJ, Stewart SL, Bernstein L, West DW, Ross RK, Deapen D, Pinder R, Reynolds P, Wright W, Anton-Culver H, 2003. Cox Regression Using Different Time-scales. Western Users of SAS Software, San Francisco, California. [Google Scholar]

- Chen CW, Lin CC, Chen KB, Kuo YC, Li CY, Chung CJ, 2014. Increased risk of dementia in people with previous exposure to general anesthesia: a nationwide population-based case-control study. Alzheimers Dement. 10, 196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenhoff RG, Laudansky KF, 2013. Anesthesia, surgery, illness and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 47, 162–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenhoff RG, Maze M, Xie Z, Culley DJ, Goodlin SJ, Zuo Z, Wei H, Whittington RA, Terrando N, Orser BA, Eckenhoff MF, 2020. Perioperative neurocognitive disorder: state of the preclinical science. Anesthesiology 132, 55–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlenbach WJ, Hough CL, Crane PK, Haneuse SJ, Carson SS, Curtis JR, Larson EB, 2010. Association between acute care and critical illness hospitalization and cognitive function in older adults. JAMA 303, 763–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evered LA, Silbert BS, Scott DA, Maruff P, Ames D, 2016. Prevalence of dementia 7.5 years after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Anesthesiology 125, 62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JP, Gray RJ, 1999. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc 94, 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- Fong TG, Jones RN, Shi P, Marcantonio ER, Yap L, Rudolph JL, Yang FM, Kiely DK, Inouye SK, 2009. Delirium accelerates cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 72, 1570–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Dong Y, Huang W, Bao M, 2017a. General anesthesia exposure and risk of dementia: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Oncotarget 8, 59628–59637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Dong Y, Huang W, Bao M, 2017b. General anesthesia exposure and risk of dementia: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Oncotarget 8, 59628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CT, Myung W, Lewis M, Lee H, Kim SE, Lee K, Lee C, Choi J, Kim H, Carroll BJ, Kim DK, 2018. Exposure to general anesthesia and risk of dementia: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J. Alzheimers Dis 63, 395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn EL, Graubard BI, Midthune D, 1997. Time-to-event analysis of longitudinal follow-up of a survey: choice of the time-scale. Am. J. Epidemiol 145, 72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogseth M, Wyller TB, Engedal K, Juliebo V, 2011. Delirium is an important predictor of incident dementia among elderly hip fracture patients. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord 31, 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstrom M, Edlund A, Bucht G, Karlsson S, Gustafson Y, 2003. Dementia after delirium in patients with femoral neck fractures. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 51, 1002–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahanna-Gabrielli E, Schenning KJ, Eriksson LI, Browndyke JN, Wright CB, Evered L, Scott DA, Wang NY, Brown CH IV, Oh E, 2019. State of the clinical science of perioperative brain health: report from the American Society of Anesthesiologists Brain Health Initiative Summit 2018. Br. J. Anaesth 123, 464–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SE, Noel-Storr A, Ritchie CW, 2010. The impact of general and regional anesthesia on the incidence of post-operative cognitive dysfunction and postoperative delirium: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis 22 (Suppl. 3), 67–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, Holt JB, Croft JB, Mack D, McGuire LC, 2019. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in adults aged≥ 65 years. Alzheimers Dement. 15, 17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendergrass JC, Targum SD, Harrison JE, 2018. Cognitive impairment associated with cancer: a brief review. Innov. Clin. Neurosci 15, 36–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph JL, Marcantonio ER, 2011. Review articles: postoperative delirium: acute change with long-term implications. Anesth. Analg 112, 1202–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendimann RN, Minagar A, 2017. Liver disease and neurology. Continuum (Minneap. Minn). 23, 762–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz DP, Shah PS, Herrmann N, Beyene J, Siddiqui N, 2011. Exposure to general anesthesia and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 11, 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Zhang X, Even-Shoshan O, 2007. Estimating anesthesia and surgical procedure times from Medicare anesthesia claims. Anesthesiology 106, 346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slor CJ, de Jonghe JF, Vreeswijk R, Groot E, Ploeg TV, van Gool WA, Eikelenboom P, Snoeck M, Schmand B, Kalisvaart KJ, 2011. Anesthesia and postoperative delirium in older adults undergoing hip surgery. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 59, 1313–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society, A.C., 2017. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2017–2019. American Cancer Society, Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- Sprung J, Jankowski CJ, Roberts RO, Weingarten TN, Aguilar AL, Runkle KJ, Tucker AK, McLaren KC, Schroeder DR, Hanson AC, Knopman DS, Gurrieri C, Warner DO, 2013. Anesthesia and incident dementia: a population-based, nested, case-control study. Mayo Clin. Proc 88, 552–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz J, Siersma V, Kessing LV, Rasmussen LS, Group I., 2013. Is postoperative cognitive dysfunction a risk factor for dementia? A cohort follow-up study. Br. J. Anaesth 110 (Suppl. 1), i92–i97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega JN, Dumas J, Newhouse PA, 2017. Cognitive effects of chemotherapy and cancer-related treatments in older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 25, 1415–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velkers C, Berger M, Gill SS, Eckenhoff R, Stuart H, Whitehead M, Austin PC, Rochon PA, Seitz D, 2021. Association between exposure to general versus regional anesthesia and risk of dementia in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 69, 58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF, 2002. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med. Care IV3–IV18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.