To the Editor:

Alveolar macrophages (AMs) from individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have impaired function, a phenomenon that may be closely linked to mitochondrial dysfunction in these cells (1–3). The trigger for this mitochondrial dysfunction is unknown. We have previously demonstrated a mechanistic role for mitochondrial iron overload in COPD and showed that systemic administration of deferiprone, a membrane-permeable iron chelator, slowed disease progression in a murine cigarette smoke exposure model (4). Clinically, lung iron overload is a well-recognized feature in individuals with COPD, with high levels of iron and iron-binding proteins in the lung extracellular space and within AMs (5–8). This iron accumulation is biologically relevant and may be connected to impaired AM function in COPD and consequently contribute to the recurrent respiratory infections that drive COPD exacerbation events (7). AM iron is therefore potentially a novel therapeutic target in COPD, but whether an iron-directed agent like deferiprone can relieve the iron burden in AMs and improve their immune function is unknown.

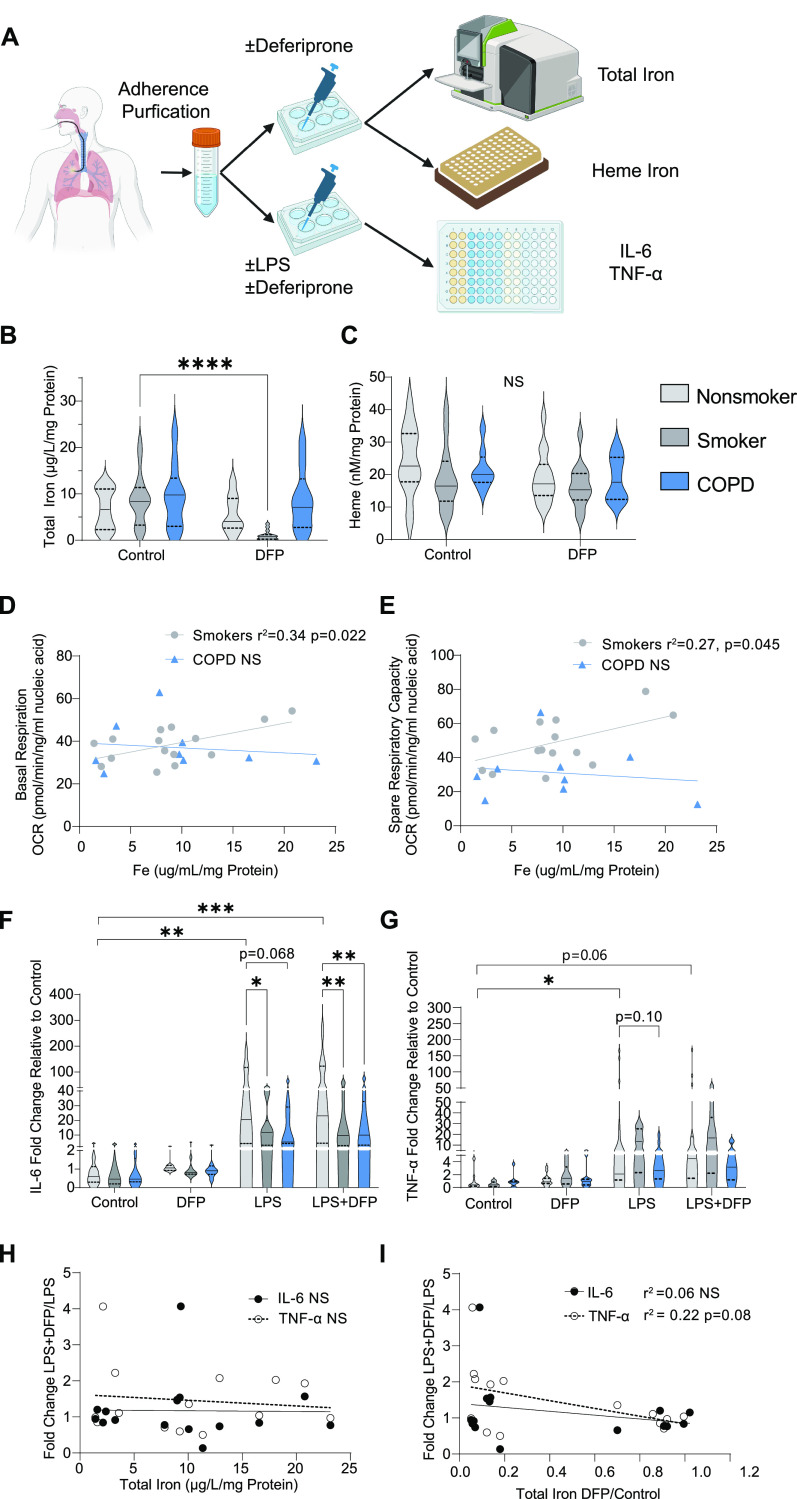

In this study, we collected BAL fluid (BALF) macrophages (hereafter referred to as AMs) from healthy nonsmoker study participants (n = 19), smokers (n = 18), and study participants with COPD (n = 10) as previously described (3, 9) (Table 1). Smokers and participants with COPD were significantly older than nonsmoker participants (P < 0.007 and P < 10−6, respectively), and participants with COPD were older than smokers (P < 0.002). Smokers were more likely to be current smokers than were participants with COPD (P < 0.0005). Following an adherence purification step (95–98% purity of AMs), as previously described (3, 9, 10), we measured the amount of total elemental iron and total heme using graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (7) and a fluorescent heme assay (11), respectively (Figure 1A). Iron levels in AMs from smokers and participants with COPD trended toward being higher than those from control participants, whereas AM heme levels did not differ between any of the subgroups (Figures 1B and 1C and Table 1). We tested AM iron levels for associations with mitochondrial function (previously measured oxygen consumption rates) in AMs from matched study subjects (3) and found that higher AM total iron was significantly associated with higher basal respiration (r2 = 0.34, P = 0.022) and spare respiratory capacity (r2 = 0.27, P = 0.045) in smokers but not in participants with COPD (Figures 1D and 1E).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population and Relevant Measured Parameters

| Parameter | Nonsmokers | Smokers | COPD |

P Value* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S vs. NS | COPD vs. NS | COPD vs. S | ||||

| No. of participants | 23 | 17 | 12 | |||

| Sex (M/F) | 10/13 | 11/6 | 9/3 | >0.3 | >0.1 | >0.8 |

| Age | 38 ± 12 | 49 ± 11 | 62 ± 7 | <0.007 | <10−6 | <0.002 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 10 | 11 | 3 | >0.7 | >0.1 | >0.1 |

| European | 4 | 2 | 7 | |||

| Hispanic | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Other | 9 | 3 | 1 | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23 ± 27 | 27 ± 4 | 28 ± 5 | >0.9 | >0.6 | >0.6 |

| Smoking history | ||||||

| Pack-years | NA | 23 ± 15 | 36 ± 23 | NA | NA | >0.06 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | NA | 17 (100) | 4 (25) | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | <0.02 |

| Urine nicotine, ng/ml | NA | 711 ± 563 | 272 ± 452 | NA | NA | <0.04 |

| Lung function† | ||||||

| FVC | 102 ± 15 | 105 ± 10 | 82 ± 18 | >0.4 | <0.002 | <0.0002 |

| FEV1 | 97 ± 13 | 97 ± 12 | 58 ± 20 | >0.9 | <10−7 | <10−6 |

| FEV1/FVC | 80 ± 5 | 75 ± 5 | 55 ± 12 | <0.008 | <10−9 | <10−6 |

| TLC | 94 ± 13 | 98 ± 12 | 99 ± 32 | >0.3 | >0.5 | >0.8 |

| DlCO | 93 ± 12 | 80 ± 16 | 70 ± 24 | <0.006 | <0.0004 | >0.1 |

| GOLD stage (I/II/III) | NA | NA | 426 | NA | NA | NA |

| Total iron, µg/L/mg | n = 16 | n = 15 | n = 9 | |||

| Control | 6.72 ± 4.34 | 8.82 ± 5.48 | 9.46 ± 6.96 | >0.4 | >0.3 | >0.9 |

| Deferiprone | 5.73 ± 3.99 | 1.02 ± 1.03 | 8.68 ± 6.62 | <0.05 | >0.3 | <0.001 |

| P value: control vs. DFP | >0.9 | <0.0001 | >0.9 | – | – | – |

| Heme iron, nM/mg | n = 14 | n = 13 | n = 8 | |||

| Control | 24.26 ± 10.50 | 19.03 ± 9.67 | 21.63 ± 6.14 | >0.2 | >0.8 | >0.8 |

| DFP | 19.11 ± 7.81 | 16.53 ± 6.66 | 18.76 ± 6.82 | >0.8 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| P value: control vs. DFP | >0.2 | >0.8 | >0.6 | – | – | – |

| IL-6, pg/mL | n = 10 | n = 11 | n = 8 | |||

| Control | 348.5 ± 439.1 | 543.5 ± 729.6 | 595.0 ± 740.0 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| DFP | 391.5 ± 380.0 | 581.0 ± 969.1 | 661.7 ± 921.2 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| LPS | 16,217 ± 25,910 | 12,657 ± 23,951 | 10,011 ± 13,272 | >0.8 | >0.7 | >0.9 |

| LPS + DFP | 17,061 ± 25,075 | 16,044 ± 25,117 | 14,784 ± 19,393 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| P value: control vs. DFP | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | – | – | – |

| P value: LPS vs. LPS+ DFP | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | – | – | – |

| TNF-α, pg/mL | n = 14 | n = 10 | n = 7 | |||

| Control | 377.3 ± 553.3 | 451.9 ± 516.2 | 299.4 ± 360.6 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| DFP | 501.7 ± 886.0 | 744.3 ± 776.4 | 317.6 ± 423.1 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| LPS | 3,557 ± 5,367 | 2,924 ± 3,135 | 1,471 ± 2,077 | >0.8 | >0.2 | >0.5 |

| LPS + DFP | 3,054 ± 3,382 | 4,015 ± 3,297 | 1,576 ± 2,184 | >0.6 | >0.4 | >0.1 |

| P value: control vs. DFP | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | – | – | – |

| P value: LPS vs. LPS + DFP | >0.9 | >0.7 | >0.9 | – | – | – |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DFP = deferiprone; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC = forced vital capacity; NA = not applicable; NS = nonsmokers, S = smokers; TLC = total lung capacity; TNF = tumor necrosis factor-α.

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation.

In demographic section, numerical parameters were compared using a Student’s t test and categorical parameters were compared using a χ2 test (Yates correction applied when applicable); P < 0.05 was considered significant. Measured iron and cytokines were compared using Tukey’s honestly significant difference test or two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test as appropriate; P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Lung function parameters are presented as measurements before administration of bronchodilators and as percent predicted except the FEV1/FVC ratio, which is presented as percent observed.

Figure 1.

Use of deferiprone (DFP) to modulate alveolar macrophage (AM) function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). (A) Experimental schema. (B) Total elemental iron and (C) intracellular heme normalized to total protein in AMs treated with or without DFP for 24 hours from nonsmoker study participants (n = 16 for total iron, n = 14 for heme), smokers (n = 15 for total iron, n = 13 for heme), and participants with COPD (n = 9 for total iron, n = 8 for heme). AM basal respiration (D) and spare respiratory capacity (E) in association with total in smokers (n = 15) and participants with COPD (n = 9). Fold change in AM supernatant IL-6 (F) (n = 10 for nonsmokers, n = 11 for smokers, n = 8 for COPD) and TNF-α (G) (n = 14 for nonsmokers, n = 10 for smokers, n = 7 for smokers) levels following LPS treatment quantified by ELISA and normalized to control unstimulated cytokine levels in the same participant. LPS-induced cytokine response in AMs from smokers (n = 9) and participants with COPD (n = 6) following DFP treatment relative to untreated response in association with baseline total iron levels (H) (n = 15 for IL-6 and TNF-α) and fractional iron reduction with DFP (I) (n = 15 for IL6 and TNF-α) in matched study participants. (B, C, F, and G) Data displayed as violin plots with a solid line indicating the median and dashed lines indicating first and third quartiles; P values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparison test or Tukey’s honestly significant difference test as appropriate (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001). (D, E, H, and I) R2 and P values obtained using unadjusted simple linear regression. OCR = oxygen consumption rate. ns = not significant.

We next assessed if deferiprone could lower iron levels in AMs. Deferiprone (300 μM for 24 h) significantly lowered iron levels in AMs from smokers (9.47–1.67 μg/L/mg; P < 0.0001), but not in control subjects or participants with COPD; deferiprone did not change heme levels in any group (Figures 1B and 1C). We then stimulated AMs with LPS (500 ng/ml) for 12 hours with and without pretreatment with deferiprone (300 μM, 24 h) and quantified secreted levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in the culture supernatant. IL-6 and TNF-α levels were variable but did not differ among control participants, smokers, and participants with COPD in any of the treatment subgroups (Figures E1A and E1B in the data supplement). To account for batch effect and individual variability, we normalized supernatant cytokine levels from each study participant to their baseline unstimulated levels. Using this fold change approach, we uncovered a trend for AMs from smokers and individuals with COPD producing lower IL-6 levels in response to LPS compared with healthy controls (14.3-fold for smokers vs. 54.5 for controls, P = 0.03; 17.4 vs. 54.5 for COPD vs. controls, P = 0.07; Figure 1F). A similar nonsignificant trend was seen with TNF-α (Figure 1G). Deferiprone did not significantly increase the amount of IL-6 and TNF-α produced in response to LPS by AMs from nonsmoker participants, smokers, and participants with COPD (Figures E1A and E1B). However, there was a trend for the LPS response in AMs from smokers and COPD participants pretreated with deferiprone to be greater relative to that of LPS-exposed AMs without pretreatment (Table 1). Specifically, there was a boost in TNF-α, but not IL-6, production that was weakly associated with the extent to which deferiprone lowered total iron levels in AMs from smokers and participants with COPD (r2 = 0.22, P = 0.079), an effect that was not associated with baseline iron levels only (Figures 1H and 1I).

These data demonstrate that iron, but not heme, levels are higher in isolated AMs from smokers and patients with COPD, and only smoker AMs responded to iron reduction by deferiprone, suggesting that the increase in iron observed in COPD AMs may be harder to chelate and may not be heme-derived. Higher iron levels in smoker AMs correlated with better mitochondrial function, an observation that was not present in COPD AMs. Although deferiprone (500 μM for 24 h) has been shown to improve glycolysis and inhibit mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in bone marrow–derived macrophages (12), whether deferiprone can alter mitochondrial function in AMs requires further extensive investigation.

Our data show that AMs from smokers and patients with COPD are hyporesponsive to LPS relative to those from healthy subjects and that, in some cases, deferiprone may improve macrophage immune function. These results are consistent with previous findings that AMs in COPD have more iron, impaired phagocytosis of respiratory bacteria, and have altered transcriptomic expression of cytokines (2, 5, 6, 9, 13), but are in contrast to data that suggest that red blood cell–derived heme may be the source of iron found in AMs in COPD (14). Although deferiprone can reduce the iron content of human monocyte–derived macrophages (12), this is the first study to show that deferiprone reduces iron in tissue-derived macrophages in a disease state.

Our study is limited by a small study population size, the batch effect of stimulating cells with LPS/deferiprone in samples as they were collected, and the possibility that, because COPD AMs are heterogeneously iron-loaded, only a subpopulation will be targeted by deferiprone (5, 6). In addition, such a small population size did not allow for consideration of additional variables such as age in our statistical analysis. Aging and accelerated senescence play an important role in COPD pathogenesis (15), and we are unable to conclude if our findings of higher iron levels inside AMs from smokers and individuals with COPD is attributable to accelerated senescence in these cells (“ferrosenescence”) (16, 17). However, in prior studies, macrophage iron accumulation observed in smokers and individuals with COPD was not affected by age (5, 8), and age was not a factor in our prior study of extracellular BALF iron levels in COPD (7).

In this study, we used IL-6 and TNF-α production in response to LPS as surrogates of immune function, leaving other common infectious stimuli (such as Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae) and immune function readouts (e.g., phagocytic ability) unexplored. Deferiprone was our choice of iron chelator given its efficacy in our murine model (4, 5) and also its pharmacologic advantage in being able to cross biological membranes, but the optimal dose and duration of treatment are not known, and higher doses have been used in other in vitro studies (12). As such, we cannot confidently attribute our inability to decrease iron levels in COPD AMs to a pharmacological issue (i.e., higher concentrations needed) or to differences in macrophage subpopulations between smokers and patients with COPD (9, 18, 19). Deferiprone is not just an iron “chelator,” but rather a shuttle that has the important pharmacokinetic characteristics of being able to traverse biological membranes and liberate intracellular iron (20). However, it is not clear if deferiprone can access only free labile iron or whether it can “pull” iron out of other biological constructs such as protein complexes like ferritin or insoluble constructs like hemosiderin (8), both of which are increased in COPD (7, 8, 21). From our previous work in mice, we also know that deferiprone treatment reduces the amount of iron inside mitochondria isolated from whole lung tissue of mice exposed to chronic smoke exposure. Whether this iron is “stuck” inside mitochondrial in COPD AMs remains to be determined and is the subject of current investigation (4).

To conclude, this is a proof-of-concept study that an iron chelator such as deferiprone may be used to lower iron levels in primary human AMs and perhaps improve AM immune function in smokers and individuals with COPD, supporting further exploratory avenues to use deferiprone as a treatment to enhance macrophage function in COPD. Additional appropriately powered studies will be needed to validate our findings, but our results add further evidence to the concept of AM iron overload as a possible targetable COPD endotype.

Footnotes

Supported by Science Foundation Ireland Future Research Leaders grant FRL4862 (S.M.C.), American Lung Association Catalyst Award 823287 (W.Z.Z.), Parker B. Francis Fellowship (W.Z.Z.), and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant HL113443 (R.G.C.).

Author Contributions: S.M.C. conceived and designed the study. S.L.O’B., R.J.K., and Y.S.-B. obtained samples and provided clinical data. K.K., S.A.K., and S.M.C. performed the experiments. K.K., W.Z.Z., and S.M.C performed the data analyses. R.G.C. provided critical discussions for data interpretation. K.K., W.Z.Z., and S.M.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

This letter has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Bewley MA, Preston JA, Mohasin M, Marriott HM, Budd RC, Swales J, et al. Impaired mitochondrial microbicidal responses in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease macrophages. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2017;196:845–855. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201608-1714OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belchamber KBR, Singh R, Batista CM, Whyte MK, Dockrell DH, Kilty I, et al. COPD-MAP Consortium Defective bacterial phagocytosis is associated with dysfunctional mitochondria in COPD macrophages. Eur Respir J . 2019;54:1802244. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02244-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Beirne SL, Kikkers SA, Oromendia C, Salit J, Rostmai MR, Ballman KV, et al. Alveolar macrophage immunometabolism and lung function impairment in smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2020;201:735–739. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1683LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cloonan SM, Glass K, Laucho-Contreras ME, Bhashyam AR, Cervo M, Pabón MA, et al. Mitochondrial iron chelation ameliorates cigarette smoke-induced bronchitis and emphysema in mice. Nat Med . 2016;22:163–174. doi: 10.1038/nm.4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Philippot Q, Deslée G, Adair-Kirk TL, Woods JC, Byers D, Conradi S, et al. Increased iron sequestration in alveolar macrophages in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One . 2014;9:e96285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Najafinobar N, Venkatesan S, von Sydow L, Klarqvist M, Olsson H, Zhou XH, et al. ToF-SIMS mediated analysis of human lung tissue reveals increased iron deposition in COPD (GOLD IV) patients. Sci Rep . 2019;9:10060. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46471-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang WZ, Oromendia C, Kikkers SA, Butler JJ, O’Beirne S, Kim K, et al. Increased airway iron parameters and risk for exacerbation in COPD: an analysis from SPIROMICS. Sci Rep . 2020;10:10562. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67047-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ho T, Nichols M, Nair G, Radford K, Kjarsgaard M, Huang C, et al. Iron in airway macrophages and infective exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res . 2022;23:8. doi: 10.1186/s12931-022-01929-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shaykhiev R, Krause A, Salit J, Strulovici-Barel Y, Harvey BG, O’Connor TP, et al. Smoking-dependent reprogramming of alveolar macrophage polarization: implication for pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Immunol . 2009;183:2867–2883. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heguy A, O’Connor TP, Luettich K, Worgall S, Cieciuch A, Harvey BG, et al. Gene expression profiling of human alveolar macrophages of phenotypically normal smokers and nonsmokers reveals a previously unrecognized subset of genes modulated by cigarette smoking. J Mol Med (Berl) . 2006;84:318–328. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sassa S. Sequential induction of heme pathway enzymes during erythroid differentiation of mouse Friend leukemia virus-infected cells. J Exp Med . 1976;143:305–315. doi: 10.1084/jem.143.2.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pereira M, Chen TD, Buang N, Olona A, Ko JH, Prendecki M, et al. Acute iron deprivation reprograms human macrophage metabolism and reduces inflammation in vivo. Cell Rep . 2019;28:498–511.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martí-Lliteras P, Regueiro V, Morey P, Hood DW, Saus C, Sauleda J, et al. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae clearance by alveolar macrophages is impaired by exposure to cigarette smoke. Infect Immun . 2009;77:4232–4242. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00305-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baker JM, Hammond M, Dungwa J, Shah R, Montero-Fernandez A, Higham A, et al. Red blood cell-derived iron alters macrophage function in COPD. Biomedicines . 2021;9:1939. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9121939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barnes PJ. Senescence in COPD and its comorbidities. Annu Rev Physiol . 2017;79:517–539. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zecca L, Youdim MB, Riederer P, Connor JR, Crichton RR. Iron, brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci . 2004;5:863–873. doi: 10.1038/nrn1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sfera A, Bullock K, Price A, Inderias L, Osorio C. Ferrosenescence: the iron age of neurodegeneration? Mech Ageing Dev . 2018;174:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liégeois M, Bai Q, Fievez L, Pirottin D, Legrand C, Guiot J, et al. Airway macrophages encompass transcriptionally and functionally distinct subsets altered by smoking. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2022;67:241–252. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2021-0563OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sauler M, McDonough JE, Adams TS, Kothapalli N, Barnthaler T, Werder RB, et al. Characterization of the COPD alveolar niche using single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Commun . 2022;13:494. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28062-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hider RC, Hoffbrand AV. The role of deferiprone in iron chelation. N Engl J Med . 2018;379:2140–2150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1800219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ghio AJ, Hilborn ED, Stonehuerner JG, Dailey LA, Carter JD, Richards JH, et al. Particulate matter in cigarette smoke alters iron homeostasis to produce a biological effect. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2008;178:1130–1138. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-334OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]