Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic progressive fibrotic interstitial lung disease. A barrier to developing more effective therapies for IPF is the dearth of preclinical models that recapitulate the early pathobiology of this disease. Intratracheal bleomycin, the conventional preclinical murine model of IPF, fails to reproduce the intrinsic dysfunction to the alveolar epithelial type 2 cell (AEC2) that is believed to be a proximal event in the pathogenesis of IPF. Murine fibrosis models based on SFTPC (Surfactant Protein C gene) mutations identified in patients with interstitial lung disease cause activation of the AEC2 unfolded protein response and endoplasmic reticulum stress—an AEC2 dysfunction phenotype observed in IPF. Although these models achieve spontaneous fibrosis, they do so with precedent lung injury and thus are challenged to phenocopy the general clinical course of patients with IPF—gradual progressive fibrosis and loss of lung function. Here, we report a refinement of a murine Sftpc mutation model to recapitulate the clinical course, physiological impairment, parenchymal cellular composition, and biomarkers associated with IPF. This platform provides the field with an innovative model to understand IPF pathogenesis and index preclinical therapeutic candidates.

Keywords: IPF, pulmonary fibrosis, unfolded protein response, AT2 cell

Clinical Relevance

A barrier to more effective therapeutic development for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is the dearth of preclinical models that recapitulate the pathogenesis and pathology of the disease. We report a major technical advance to murine lung fibrosis modeling that permits faithful recapitulation of the clinical course, physiological impairment, parenchymal changes in cellular composition, and elaboration of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis–associated biomarkers, resulting in an innovative tool in the search for novel therapeutics.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic progressive interstitial lung disease (1), histologically defined by the destruction of the alveolar–capillary interface with infiltration of myofibroblasts into the distal lung parenchyma and loss of the normal alveolar epithelial composition with the accumulation of hyperplastic epithelial cells expressing markers of an aberrant “transitional” state (2, 3). This loss of alveolar structure and function leads to impaired gas exchange and subsequent respiratory failure. Despite two antifibrotic drugs approved for the treatment of IPF, it remains the leading diagnosis for lung transplant referral (4). A barrier to more effective therapeutic development is the dearth of preclinical models that recapitulate the pathogenesis and pathology of IPF (5).

The conventional preclinical murine model of IPF has been the intratracheal instillation of bleomycin, which causes DNA strand damage and oxidative stress to the lung epithelium and subsequent alveolitis followed by fibrotic lung remodeling (6). This model of epithelial injury and fibrotic repair has been further refined by the development of repetitive bleomycin dosing intervals, providing a more durable fibrotic remodeling (7, 8). However, this too is a model of extrinsic lung epithelial injury and fails to phenocopy the intrinsic dysfunction found in the alveolar epithelial type 2 cell (AEC2), which is believed to be a proximal event in the pathogenesis of IPF (9).

Based on the study of familial cohorts of patients with pulmonary fibrosis, we and others have identified specific mutations associated with the development of disease. Although these driver mutations account for <10% of IPF cases, they provide the opportunity to study the proximal events in disease pathogenesis and have provided models of spontaneous lung fibrosis. Broadly, these models can be broken down into those based on clinical mutations in the telomerase complex that cause severe AEC2 senescence (10, 11), those based on mutations in surfactant proteins that cause disruption of AEC2 proteostasis (12–14), and mutations that disrupt AEC2 organellar quality control (15–17).

We previously reported the generation of a murine fibrosis model based on a clinical SFTPC (Surfactant Protein C gene) mutation identified in a pediatric patient with interstitial lung disease (13), whereby the expression of a Brichos class surfactant protein c proprotein (proSP-C) mutant caused activation of the AEC2 unfolded protein response (UPR) and endoplasmic reticulum stress, with subsequent AEC2 recruitment of immune cells and alveolitis. Although the AEC2 dysfunction that initiates this model is a cellular phenotype observed in patients with sporadic IPF (non-SFTPC mutation associated) (18, 19), and ultimately results in spontaneous fibrotic remodeling with IPF features, it does not fully recapitulate the predominant protracted clinical course of patients with IPF—that of a progressive fibrosis without significant antecedent diffuse lung injury. Here we report a major refinement to this murine model that permits faithful recapitulation of the clinical course, physiological impairment, parenchymal changes in cellular composition, and elaboration of IPF-associated biomarkers, resulting in an innovative tool in the search for novel therapeutics.

Methods

Animals and Mutation Induction

The SftpcC121Gneo founder line was commercially produced (Genoway, Inc.) and crossed to the Rosa26ERT2-Cre strain B6.129-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(cre/ERT2)Tyj/J (stock no. 008463; The Jackson Laboratory) to permit tamoxifen (TMX)-inducible removal of phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK)-neomycin cassette as previously described (13). The progeny were backcrossed to achieve homozygosity of the Sftpc mutant allele and the Rosa26ERT2-Cre allele (R26Ert2Cre). TMX (dissolved in corn oil at 20 mg/ml) was delivered by oral gavage (OG) at 200 mg/kg (female) and 230 mg/kg (male) once weekly to induce Sftpc mutation expression (mice hereafter referred to as SftpcC121G). Sftpc wild-type (SftpcWT) mice harboring homozygous R26Ert2Cre allele treated with TMX were used as controls. Mice were weighed weekly, and TMX dose was adjusted for weight changes. Both male and female animals aged 12–16 weeks were used (except where noted), and all mouse strains and genotypes generated for these studies were congenic with C57/B6/J.

Endpoint Analysis

BAL fluid analysis

BAL fluid (BALF) was collected from mice using sequential lavages of lungs with five 1-ml aliquots of sterile saline. Cell pellets recovered from centrifugation were resuspended in 1 ml PBS and total BALF cell counts were determined using a Z1 Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter). Differential cell counts were determined manually from cytospins of BALF cell pellets stained with modified Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich, GS500). The first milliliter of recovered cell-free BALF was first analyzed for protein content using the Lowery Assay with 350-μl aliquots used for Luminex assays. BALF was loaded for western blotting as previously described and probed for Osteopontin secreted phosphoprotein-1 (SPP1) (1:1,000; Millipore AB10910) and MMP7 (matrix metalloproteinase 7) (1:1,000; Cell Signaling 3801). BALF mitochondrial DNA was quantified as previously described (20).

Assessment of fibrotic burden and remodeling

At take down, mice underwent Flexivent analysis for assessment of lung physiology as previously described (13, 21). The fourth lobe was resected for RNA isolation. The remaining lobes were inflated by intratracheal instillation of 10% formalin at a constant pressure of 25 cm H2O, embedded in paraffin, and 6-μm sections were obtained and stained with Masson’s trichrome and picrosirius red. Septal collagen was quantified as a mean area of positive picrosirius staining as a percentage of total septal areas, as previously described (16, 22). Lung sections were stained with antibodies against proSP-C (1:300; NPRO2, in-house and previously published [23]), SMA (smooth muscle actin) (1:500; Sigma Aldrich A2547), and Krt8 (keratin 8) (TROMA-1, 1:200; University of Iowa Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Fluorescently conjugated secondary antibodies were used at 1:200 (Invitrogen). All imaging was performed on a Nikon Eclipse 80i and analyzed on ImageJ.

AEC2 analysis

Mouse AEC2s were isolated as previously described and validated (13, 16). See supplemental methods for details on AEC2 isolation protocol, western blot analysis, and qRT-PCR testing of mRNA and genomic DNA.

Whole lung gene expression

Whole lung RNA was obtained from the fourth lobe and analyzed by qRT-PCR and RNA sequencing. See supplemental methods for RNA isolation protocol, qRT-PCR, and details of RNA sequencing methodology.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.3.1 and are presented as the mean ± SEM. Differences between genotypes at specific time points were examined using Student’s unpaired two-tailed test, with P < 0.05 considered to be significant. Survival statistics were assessed using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Results

Chronic Induction of Sftpc Mutant Alleles Produces Fibrotic Remodeling

Inducible (SftpcC121Gneo; R26Ert2Cre) mice (hereafter, SftpcC121G) receiving weekly OG TMX were monitored over the course of 7 weeks (Figure 1A). Compared with our previously published intraperitoneal (IP) TMX (400 mg/kg) strategy, in which 90.6 ± 1.0% of AEC2 had inducible removal of the PGK-neo cassette at 7 days, we found that two doses of OG TMX (200 mg/kg) caused removal of only 56.0 ± 3.8% of AEC2 PGK-neo cassettes at 2 weeks, which increased to 82.2 ± 6.0% of AEC2 at 7 weeks (see Figures E1A and E1B in the data supplement) and resulted in a gradual induction of AEC2s expressing the mutant Sftpc allele with associated weight loss (Figure 1B). Controls for the SftpcC121G experiments consisted of SftpcWT mice crossed to R26ERt2Cre mice (hereafter, SftpcWT) that received OG TMX to control for potential toxicity from chronic TMX and Cre recombinase (Cre) expression, which showed similar weight curves over time, lung compliance, and BALF cell count to inducible (SftpcC121Gneo; R26ERt2Cre) mice that received OG corn oil (vehicle for the TMX) (Figures E1C–E1F). We identified a separation of the weight curves between the SftpcC121G and SftpcWT at 1 week after the first OG TMX, with further separation as the study progressed. Unlike our previously reported IP TMX strategy that had substantial early mortality from acute alveolitis, the mortality with the OG TMX strategy at 7 weeks was minimal (Figure 1C), although progressive weight loss meeting the mortality endpoint prevented longer study duration.

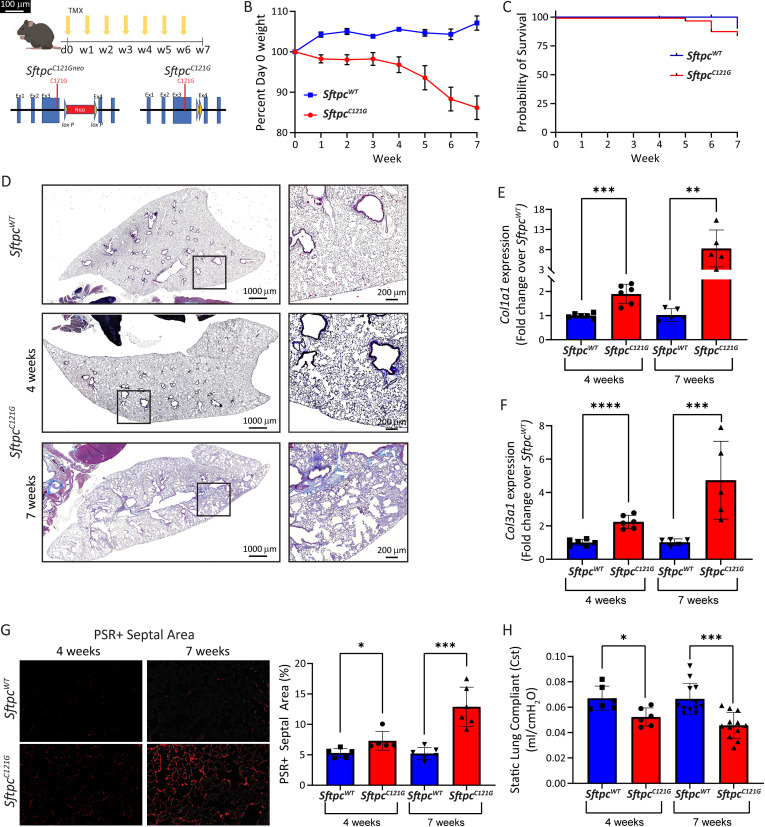

Figure 1.

Fibrotic remodeling in the Sftpc (Surfactant Protein C gene) mutation model. (A) Schematic of tamoxifen (TMX) induction and excision of the inhibitory phosphoglycerate kinase-neomycin (PGK-neo) cassette from the founder SftpcC121Gneo allele to generate the active SftpcC121G allele. (B) Weight loss curves (mean ± SEM) for SftpcC121G and Sftpc wild-type (SftpcWT) mice receiving weekly oral gavage (OG) TMX (n = 12 and 6, respectively). (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for SftpcWT and SftpcC121G mice; P = 0.46 by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (D) Representative lung sections stained with Masson’s trichrome (scale bar, 1,000 μm; insert, 200 μm). (E and F) Whole lung relative expression of collagen type I alpha 1 chain (Col1a1) and collagen type III alpha 1 chain (Col3a1) at 4 and 7 weeks in the model as measured by qRT-PCR (n = 6 [4 wk] and n = 5 [7 wk]). (G) Left panel shows representative 20× magnification of picrosirius red (PSR)-stained sections showing septal fibrillar collagen (PSR+). Right panel shows quantification of PSR+ septal areas as percentage of total septal area at 4 and 7 weeks (average PSR+ septal area per lung as quantified in 10 20× fields/lung; n = 6). Scale bars, 100 μm. (H) Cst measured by Flexivent at 4 (n = 6) and 7 weeks (n = 12). SftpcC121G and SftpcWT compared by Student’s t test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. Cst = static lung compliance.

Histological examination with trichrome staining demonstrated early remodeling at 4 weeks and then regions of dense fibrotic remodeling appearing in the SftpcC121G mice at 7 weeks (Figure 1D). Consistent with the trichrome staining, analysis of whole lung RNA expression showed an initial increase in collagen type I alpha 1 chain (Col1a1) and collagen type III alpha 1 chain (Col3a1) gene expression at 4 weeks, which further increased by 7 weeks (Figures 1E and 1F) in the SftpcC121G mice. Analysis of lung sections stained with picrosirius red to mark fibrillar collagen deposition showed a twofold increase in septal collagen in regions not densely fibrotic at 7 weeks (Figure 1F). The physiological consequence of this remodeling was the development of a restrictive impairment, as demonstrated by a decrease in the static lung compliance (Figure 1G). Together, these phenotype data reveal the successful development of a model of progressive lung fibrosis with collagen deposition and tissue remodeling causing a restrictive physiologic defect.

Aged Mice Have Increased Susceptibility to Sftpc Mutation–induced Fibrosis

IPF is considered a disease of aging, typically diagnosed in patients in the sixth decade of life. We were interested in whether aged SftpcC121G mice would display enhanced susceptibility to developing lung fibrosis compared with young SftpcC121G mice. We performed the weekly OG TMX induction in aged (48–52 wk) mice and compared their phenotype to that of young SftpcC121G mice (Figure E2A). Compared with young cohorts, aged SftpcC121G mice had accelerated weight loss and earlier mortality and developed dense histological fibrotic remodeling by 4 weeks accompanied by increased collagen gene expression (Figures E2B–E2E).

Identification of IPF Biomarkers in the Chronic Sftpc Mutation Model

Protein biomarkers have diagnostic and prognostic capabilities in IPF (24, 25). We first identified a nearly sixfold increase in the protein content in the BALF of the SftpcC121G mouse lungs (Figure 2A), which suggests increased barrier permeability, a feature of the IPF lung (26), and then sought to analyze the BALF for the presence of known IPF biomarkers. The profibrotic protein Osteopontin (SPP1) and the matrix metalloproteinase MMP7 have been shown to differentiate IPF from other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (24), and by western blot analysis we found the presence of both of these proteins in the SftpcC121G BALF (Figure 2B). In addition, by Luminex assay we identified an increase in tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP1) (Figure 2C), another recently identified IPF biomarker associated with tissue remodeling (27).

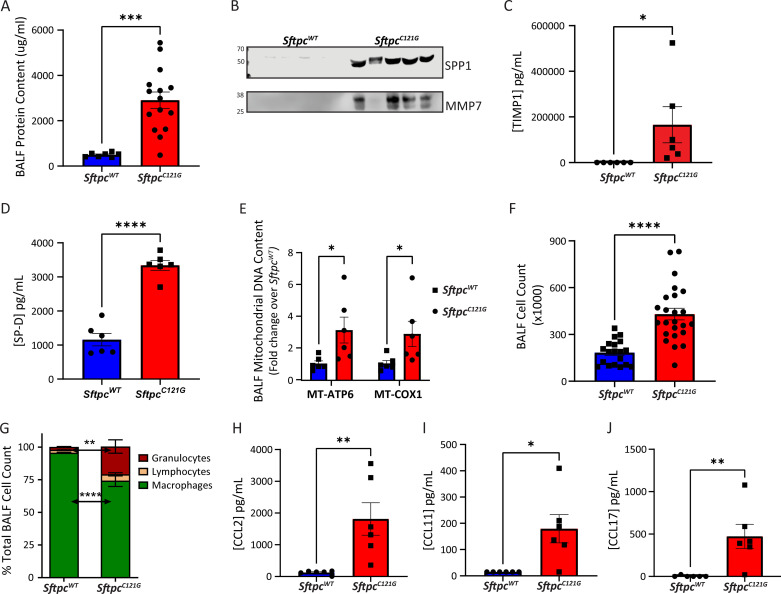

Figure 2.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) biomarkers in the Sftpc mutation model. (A) BAL fluid (BALF) protein content in SftpcC121G and SftpcWT (n = 15 and 7, respectively). (B) Western blot analysis of BALF for SPP1 (secreted phosphoprotein-1) and MMP7 (matrix metalloproteinase 7) (equal volume loading, 20 μl; n = 5). (C and D) TIMP1 (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1) and SP-D (surfactant protein D) content in SftpcC121G and SftpcWT BALF (n = 6). (E) BALF mitochondrial DNA content for MT-ATP6 (mitochondrially encoded ATP synthase membrane subunit 6) and MT-COX1 (mitochondrially encoded cytochrome c oxidase I) (n = 6). (F) Cell count in SftpcC121G and SftpcWT (n = 24 and 19, respectively). (G) BALF cell differentials as assessed by Giemsa-stained cytospins show increased percentage of granulocytes and reduced percentage of macrophages in SftpcC121G. (H–J) CCL2, CCL11, and CCL17 content in SftpcC121G and SftpcWT BALF (n = 6). SftpcC121G and SftpcWT compared by Student’s t test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

In addition to tissue remodeling–associated biomarkers, we also identified an increase in BALF IL6, which has been identified in the serum of patients with IPF and is a known mitogen affecting both myofibroblast differentiation and expansion and epithelial proliferation (28, 29), and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), an alternative signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) activator, heretofore not implicated in lung fibrosis (Figures E3A and E3B). We also identified an increase in BALF SP-D (surfactant protein D), an epithelial-derived biomarker in IPF (24) (Figure 2D), and mitochondrial DNAs (mtDNAs) (Figure 2E) which have prognostic implications for disease progression (20). These data show a diverse assortment of IPF biomarkers in the BALF from the chronic fibrosis model.

We next sought to interrogate the cellular composition of the BALF in the chronic fibrosis model. Compared with our acute IP TMX model (13), where we discovered a five- to sixfold increase in BALF cells in SftpcC121G mice compared with control mice during peak alveolitis, BALF cell counts in the chronic OG model at 2, 4, and 7 weeks did not reflect an overt alveolitis, with a limited 1.8- to 2.4-fold increase over time (Figures 2F and E4A). Analysis of the BALF cells at 7 weeks by Giemsa staining showed an increase in the percentage and absolute number of granulocytes (Figures 2G and E4B–E4D), which is appreciated in the BALF from patients with IPF (30). We sought to identify cytokines in the BALF associated with IPF that may be responsible for this increased BALF cell count. We identified both an increase in CCL2, CCL11, and CCL17 (Figures 2H–J) and an increase in the corresponding RNAs in AEC2 in the SftpcC121G mice (Figure E5). In addition, we found increases in CXCL1, CXCL9, CXCL10, and Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in the BALF from the SftpcC121G mice (Figure E6). Taken in whole, the BALF from the chronic SftpcC121G fibrosis model contains disease-relevant tissue remodeling biomarkers (SPP1, MMP7, TIMP1), markers of resident cell dysfunction (SP-D, mtDNA), and AEC2-derived cytokines implicated in the multicellular orchestration of lung fibrosis.

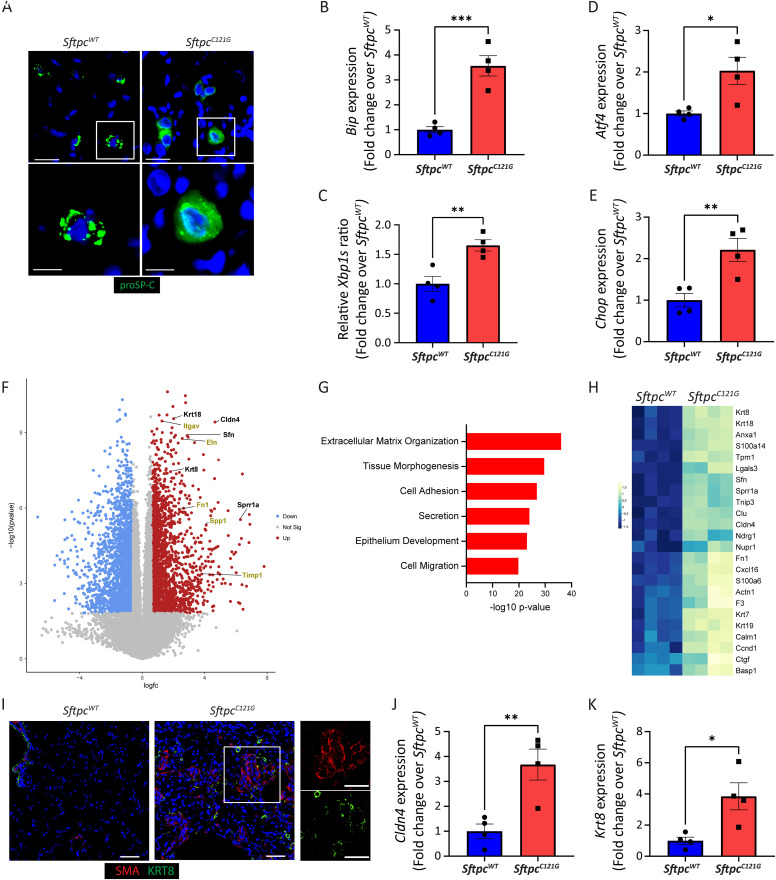

Figure 3.

Sftpc mutant mice exhibit a persistent unfolded protein response (UPR) and aberrant transitional epithelium. (A) Representative immunofluorescence staining of SftpcWT and SftpcC121G lungs for proSP-C (surfactant protein c proprotein); magnified inserts show punctate appearance to wild-type proSP-C and reticular pattern to mutant proSP-C, 60× magnification (scale bar, 20 μm [top] and 10 μm [bottom]). (B–E) Alveolar epithelial type 2 cell (AEC2) expression of UPR genes Bip (binding immunoglobulin protein), Aft4 (Activating transcription factor 4), Chop (C/EBP homologous protein), and spliced isoform of Xbp1 (X-box binding protein 1) as measured by qRT-PCR at 4 weeks (n = 4). (F) Volcano plot showing differentially upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) genes (>1.5-fold change; adjusted P value < 0.05) between of SftpcC121G and SftpcWT. Selected genes associated with aberrant epithelial state (black) and tissue remodeling (yellow) are annotated. (G) Gene ontogeny analysis for upregulated biological processes (see Table E2 for top 20 enriched pathway list). (H) Heatmap of genes associated with the aberrant transitional epithelial state. (I) Representative immunofluorescence staining of SftpcWT and SftpcC121G lungs for Krt8 (keratin 8) and αSMA (α-smooth muscle actin), 20× magnification (scale bar, 40 μm). (J and K) AEC2 relative expression of transitional cell markers Cldn4 (Claudin 4) and Krt8 by qRT-PCR at 4 weeks (n = 4). SftpcC121G and SftpcWT compared by Student’s t test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Sftpc Mutation Expression Produces an Endoplasmic Reticulum–retained Proprotein and Persistent UPR Activation

Lung sections stained for proSP-C at 7 weeks in the OG TMX SftpcC121G demonstrated a diffuse reticular pattern with perinuclear aggregates consistent with proximal retention of the proprotein compared with the cytoplasmic punctate appearance of the wild-type proprotein consistent with its known trafficking to lamellar bodies (Figure 3A). Analysis of isolated AEC2 for UPR signaling at 4 weeks demonstrated selective increases in gene and protein expression for the general marker of UPR activation, binding immunoglobulin protein (Bip) (Figures 3B and E7) in SftpcC121G AEC2. Engagement of the inositol-requiring enzyme1α (IRE1α) and protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) arms of the UPR in the IPF epithelium has been implicated in disease pathogenesis (19). We found that IRE1α signaling was activated in the AEC2 of the SftpcC121G mice as shown by an increase in the spliced transcript of X-box binding protein 1 (Xbp1) indicative of enhanced IRE1α RNAse activity (Figure 3C). Activation of the PERK arm of the UPR was interrogated by gene expression changes in Activating transcription factor 4 (Aft4) and C/EBP homologous protein (Chop), and both were found to be significantly increased in the SftpcC121G AEC2s (Figures 3D, 3E, and E7). In addition, interrogation of whole lung gene expression for UPR genes demonstrated UPR activation (Figure E8A). Together, these data show UPR activation in the lungs and specifically the AEC2 in the Sftpc mutant mice, a cellular phenotype observed in the IPF epithelia (31), at 4 weeks in the model when early fibrotic remodeling appears.

Sftpc Induced UPR Is Associated with Emergence of Aberrant Cellular Populations

Next, we performed whole lung gene expression analysis on the SftpcC121G mice at 7 weeks to identify global changes in the lung transcriptome associated with the development of the fibrotic lung (Figure E8B). We discovered that many of the most differentially expressed genes were associated with epithelial cell differentiation and fibrogenesis (Figures 3F, E8C, and E8D). Gene ontogeny analysis affirmed enrichment of pathways associated with extracellular matrix and epithelial development (Figure 3G).

Recently, a persistent anomalous distal lung epithelial population expressing markers of an aberrant transitional state (Krt8, Claudin 4 (Cldn4)) has been identified in the lungs of mice with fibrotic lung injury with a human homolog identified in the lungs of patients with IPF (2, 3, 7, 32). We have identified that this AEC2 cell state emerges in the IP TMX modeling of SftpcC121G mice, and we have implicated AEC2 UPR signaling in the cell state’s ontogeny (33). Whole lung gene expression analysis from the SftpcC121G mice at 7 weeks revealed enrichment of marker genes for this aberrant epithelial population (Figure 3H), which was affirmed by qRT-PCR enrichment of Krt8, Cldn4, growth differentiation factor 15 (Gdf15), and small proline rich protein 1A (Sprr1a) (Figures E8E–E8H). We next performed staining for Krt8 as a marker of the transitional state and αSMA to define regions of alveolar parenchymal fibrosis. In the SftpcWT lung sections, Krt8+ cells were limited to the distal airways and αSMA+ cells to airway and vascular smooth muscle cells in the distal lung. However, in the lung parenchyma of SftpcC121G mice, we identified Krt8+ cells in close proximity to accumulating αSMA+ cells, indicative of aberrant epithelial cells in regions of fibrotic remodeling (Figure 3I). Finally, we identified that at 4 weeks sorted SftpcC121G AEC2 were enriched in Cldn4 and Krt8 expression (Figure 3J and 3K), showing the UPR-activated AEC2s develop a transitional phenotype during early fibrogenesis in this model. Taken in whole, these data identify a cellular composition of the SftpcC121G mice lung that aligns with aberrant populations identified in the lungs of patients with IPF.

Discussion

Preclinical modeling of IPF has proven to be challenging, and the lack of optimal murine models is a barrier to identifying more effective therapies. Intratracheal bleomycin has been the standard for disease modeling. Recent optimization of bleomycin delivery with repetitive dosing has been a major technical advance for our field (7, 8), showing the capacity of this model to recapitulate many of the histopathological features of the IPF lung. However, this model relies on exogenous injury and not the intrinsic disruption of alveolar epithelial cell homeostasis that is believed to be the upstream event in IPF pathobiology (9). The chronic SftpcC121G fibrosis model, which is initiated by the disruption of AEC2 proteostasis imposed by the expressed proSP-C mutant isoform, phenocopies an AEC2 phenotype observed in the lungs of patients with IPF and is hypothesized to be a proximal cellular dysfunction that initiates profibrotic signaling (18, 19, 34). Thus, chronic TMX induction of SftpcC121G mice provides a new preclinical tool to better model the initial pathobiology of IPF.

The utility of a preclinical model can be evaluated based on its similarity with the clinical disease, which includes not only shared pathobiology but also physiology, histopathology, and disease-relevant biomarkers. We had previously reported our model of AEC2 initiated alveolitis and lung injury followed by fibrotic remodeling and likened this phenotypic pattern to an acute exacerbation of IPF, a clinical event defined by alveolitis and accelerated fibrosis encountered by roughly 20% of patients at some point during their disease course (35). However, we believed that this modeling failed to phenocopy the dominant clinical course of progressive lung fibrosis faced by most patients. This current optimized model of lung fibrosis overcomes the mortality and injury-repair phenotype observed in our previous report. Not only did the SftpcC121G mice develop spontaneous progressive lung fibrosis with restrictive lung physiology, but interrogation of the BALF in the model for the presence of IPF-associated biomarkers identified disease-associated mediators of tissue remodeling as well as a multitude of IPF-linked cytokines and chemokines. Finally, we identified the presence of a recently described aberrant transitional epithelial cell (2, 3, 7) and found these cells intermixed with SMA+ cells within the lung parenchyma showing a distal lung cellular composition and histopathology seen in IPF (32, 36).

The SftpcC121G model of AEC2 dysfunction leading to spontaneous lung fibrosis thus becomes a valuable tool for asking fundamental questions of lung fibrogenesis and specifically the distal lung epithelial contribution to disease. Future work in this model using single-cell genomics and spatial transcriptomics may provide mechanistic insights into the cellular niche that drives lung fibrosis. The SftpcC121G model also offers a disease-relevant platform for biomarker discovery and therapeutic interrogation.

Footnotes

Supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants F32 HL160011 (L.R.), R01 HL145408 (M.F.B.), U01 HL152970 (M.F.B.), and 1K08HL150226 (J.K.); Department of Veterans Affairs, Merit Review 2I01BX001176-10 (M.F.B.); the Bristol Myers Squibb IDEAL Consortium 2.0 (J.K. and M.F.B.); the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (J.K.); and the Parker B Francis Foundation (J.K.).

Author Contributions: L.R., Y.T., P.C., T.D., M.Z., K.C., S.I., M.F.B., A.M., and J.K. participated in study conception, experimental design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation. L.H., C.E., L.S., and G.T. performed data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2022-0203MA on December 6, 2022

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Lederer DJ, Martinez FJ. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med . 2018;378:1811–1823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1705751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Strunz M, Simon LM, Ansari M, Kathiriya JJ, Angelidis I, Mayr CH, et al. Alveolar regeneration through a Krt8+ transitional stem cell state that persists in human lung fibrosis. Nat Commun . 2020;11:3559. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17358-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jiang P, Gil de Rubio R, Hrycaj SM, Gurczynski SJ, Riemondy KA, Moore BB, et al. Ineffectual type 2-to-type 1 alveolar epithelial cell differentiation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: persistence of the KRT8hi transitional state. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2020;201:1443–1447. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201909-1726LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chambers DC, Perch M, Zuckermann A, Cherikh WS, Harhay MO, Hayes D, Jr, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-eighth adult lung transplantation report - 2021; focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant . 2021;40:1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2021.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jenkins RG, Moore BB, Chambers RC, Eickelberg O, Königshoff M, Kolb M, et al. ATS Assembly on Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: use of animal models for the preclinical assessment of potential therapies for pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2017;56:667–679. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0096ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. B Moore B, Lawson WE, Oury TD, Sisson TH, Raghavendran K, Hogaboam CM. Animal models of fibrotic lung disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2013;49:167–179. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0094TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Redente EF, Black BP, Backos DS, Bahadur AN, Humphries SM, Lynch DA, et al. Persistent, progressive pulmonary fibrosis and epithelial remodeling in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2021;64:669–676. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2020-0542MA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Degryse AL, Tanjore H, Xu XC, Polosukhin VV, Jones BR, McMahon FB, et al. Repetitive intratracheal bleomycin models several features of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2010;299:L442–L452. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00026.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Katzen J, Beers MF. Contributions of alveolar epithelial cell quality control to pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest . 2020;130:5088–5099. doi: 10.1172/JCI139519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naikawadi RP, Disayabutr S, Mallavia B, Donne ML, Green G, La JL, et al. Telomere dysfunction in alveolar epithelial cells causes lung remodeling and fibrosis. JCI Insight . 2016;1:e86704. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yao C, Guan X, Carraro G, Parimon T, Liu X, Huang G, et al. Senescence of alveolar type 2 cells drives progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2021;203:707–717. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1274OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takezaki A, Tsukumo SI, Setoguchi Y, Ledford JG, Goto H, Hosomichi K, et al. A homozygous SFTPA1 mutation drives necroptosis of type II alveolar epithelial cells in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med . 2019;216:2724–2735. doi: 10.1084/jem.20182351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Katzen J, Wagner BD, Venosa A, Kopp M, Tomer Y, Russo SJ, et al. An SFTPC BRICHOS mutant links epithelial ER stress and spontaneous lung fibrosis. JCI Insight . 2019;4:e126125. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.126125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borok Z, Horie M, Flodby P, Wang H, Liu Y, Ganesh S, et al. Grp78 loss in epithelial progenitors reveals an age-linked role for endoplasmic reticulum stress in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2020;201:198–211. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201902-0451OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lyerla TA, Rusiniak ME, Borchers M, Jahreis G, Tan J, Ohtake P, et al. Aberrant lung structure, composition, and function in a murine model of Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2003;285:L643–L653. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00024.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nureki SI, Tomer Y, Venosa A, Katzen J, Russo SJ, Jamil S, et al. Expression of mutant Sftpc in murine alveolar epithelia drives spontaneous lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest . 2018;128:4008–4024. doi: 10.1172/JCI99287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Young LR, Gulleman PM, Bridges JP, Weaver TE, Deutsch GH, Blackwell TS, et al. The alveolar epithelium determines susceptibility to lung fibrosis in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2012;186:1014–1024. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201207-1206OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kropski JA, Blackwell TS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disease. J Clin Invest . 2018;128:64–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI93560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lawson WE, Cheng DS, Degryse AL, Tanjore H, Polosukhin VV, Xu XC, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress enhances fibrotic remodeling in the lungs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2011;108:10562–10567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107559108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ryu C, Sun H, Gulati M, Herazo-Maya JD, Chen Y, Osafo-Addo A, et al. Extracellular mitochondrial DNA is generated by fibroblasts and predicts death in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2017;196:1571–1581. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201612-2480OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Headley L, Bi W, Wilson C, Collum SD, Chavez M, Darwiche T, et al. Low-dose administration of bleomycin leads to early alterations in lung mechanics. Exp Physiol . 2018;103:1692–1703. doi: 10.1113/EP087322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Henderson NC, Arnold TD, Katamura Y, Giacomini MM, Rodriguez JD, McCarty JH, et al. Selective αv integrin depletion identifies a core, targetable molecular pathway that regulates fibrosis across solid organs. Nat Med . 2013;19:1617–1624. doi: 10.1038/nm.3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beers MF, Kim CY, Dodia C, Fisher AB. Localization, synthesis, and processing of surfactant protein SP-C in rat lung analyzed by epitope-specific antipeptide antibodies. J Biol Chem . 1994;269:20318–20328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. White ES, Xia M, Murray S, Dyal R, Flaherty CM, Flaherty KR, et al. Plasma surfactant protein-d, matrix metalloproteinase-7, and osteopontin index distinguishes idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis from other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2016;194:1242–1251. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0862OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neighbors M, Cabanski CR, Ramalingam TR, Sheng XR, Tew GW, Gu C, et al. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treated with pirfenidone: post-hoc assessment of the CAPACITY and ASCEND trials. Lancet Respir Med . 2018;6:615–626. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Probst CK, Montesi SB, Medoff BD, Shea BS, Knipe RS. Vascular permeability in the fibrotic lung. Eur Respir J . 2020;56:1900100. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00100-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Todd JL, Vinisko R, Liu Y, Neely ML, Overton R, Flaherty KR, et al. IPF-PRO Registry investigators Circulating matrix metalloproteinases and tissue metalloproteinase inhibitors in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the multicenter IPF-PRO Registry cohort. BMC Pulm Med . 2020;20:64. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-1103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zepp JA, Zacharias WJ, Frank DB, Cavanaugh CA, Zhou S, Morley MP, et al. Distinct mesenchymal lineages and niches promote epithelial self-renewal and myofibrogenesis in the lung. Cell . 2017;170:1134–1148.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Papiris SA, Tomos IP, Karakatsani A, Spathis A, Korbila I, Analitis A, et al. High levels of IL-6 and IL-8 characterize early-on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis acute exacerbations. Cytokine . 2018;102:168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pesci A, Ricchiuti E, Ruggiero R, De Micheli A. Bronchoalveolar lavage in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: what does it tell us? Respir Med . 2010;104:S70–S73. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Korfei M, Ruppert C, Mahavadi P, Henneke I, Markart P, Koch M, et al. Epithelial endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in sporadic idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2008;178:838–846. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-313OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Habermann AC, Gutierrez AJ, Bui LT, Yahn SL, Winters NI, Calvi CL, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals profibrotic roles of distinct epithelial and mesenchymal lineages in pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Adv . 2020;6:eaba1972. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Katzen J, Rodriguez L, Tomer Y, Babu A, Zhao M, Murthy A, et al. Disruption of proteostasis causes IRE1 mediated reprogramming of alveolar epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2022;119:e2123187119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2123187119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tanjore H, Lawson WE, Blackwell TS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress as a pro-fibrotic stimulus. Biochim Biophys Acta . 2013;1832:940–947. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim DS, Collard HR, King TE., Jr Classification and natural history of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc . 2006;3:285–292. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-005TK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Adams TS, Schupp JC, Poli S, Ayaub EA, Neumark N, Ahangari F, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals ectopic and aberrant lung-resident cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Adv . 2020;6:eaba1983. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]