Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common heart disease in cats with a suspected genetic origin. Previous studies have identified five HCM-associated variants in three genes (Myosin binding protein C3: MYBPC3 p.A31P, p.A74T, p.R820W; Myosin heavy chain 7: MYH7 p.E1883K; Alstrom syndrome protein 1: ALMS1 p.G3376R). These variants are considered breed-specific, with the exception of MYBPC3 p.A74T, and have rarely been found in other breeds. However, genetic studies on HCM-associated variants across breeds are still insufficient because of population and breed bias caused by differences in genetic background. This study investigates the ubiquitous occurrence of HCM-associated genetic variants among cat breeds, using 57 HCM-affected, 19 HCM-unaffected, and 227 non-examined cats from the Japanese population. Genotyping of the five variants revealed the presence of MYBPC3 p.A31P and ALMS1 p.G3376R in two (Munchkin and Scottish Fold) and five non-specific breeds (American Shorthair, Exotic Shorthair, Minuet, Munchkin and Scottish Fold), respectively, in which the variants had not been identified previously. In addition, our results indicate that the ALMS1 variants identified in the Sphynx breed might not be Sphynx-specific. Overall, our results suggest that these two specific variants may still be found in other cat breeds and should be examined in detail in a population-driven manner. Furthermore, applying genetic testing to Munchkin and Scottish Fold, the breeds with both MYBPC3 and ALMS1 variants, will help prevent the development of new HCM-affected cat colonies.

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common type of heart disease in cats, with an estimated prevalence of approximately 15% in the asymptomatic cat population [1–5]. Most HCM-affected individuals do not appear symptomatic immediately. However, HCM in cats often causes congestive heart failure and arterial thromboembolism, and a minority of cats die suddenly without clinical signs [6–8]. Feline HCM is diagnosed not only by echocardiography, which demonstrates several regional hypertrophic patterns (predominantly including the left ventricle), but also by the absence of diseases that cause cardiomyopathy phenotypes, such as hypertension and hyperthyroidism [9]. Establishing an HCM diagnosis can sometimes be challenging because of the necessary differentiation between various phenotypic categories.

Most cats with HCM are randomly bred; otherwise, HCM is often associated with some specific breeds, including Maine Coon, Ragdoll, American Shorthair, British Shorthair, Persian, Bengal, Sphynx, Norwegian Forest cat, and Scottish Fold [10–15]. The familial incidence of this disease has also been confirmed, suggesting a genetic etiology [16]. However, only a few HCM-related variants have been identified in cats.

Three genetic variants have indicated the association with feline HCM in one of the sarcomeric genes, the Myosin binding protein C3 (MYBPC3) gene. MYBPC3 p.A31P was the first identified HCM-associated variant in a familial HCM colony of Maine Coon [17]. The second variant, MYBPC3 p.R820W, was shown to be associated with HCM in Ragdoll cats [10] These two mutations are widely recognized as HCM-causative mutations, and homozygotes of each mutation have a higher risk of developing HCM [18]. Another study proposed HCM association with the MYBPC3 p.A74T variant; however, this mutation was considered unrelated to cardiomyopathy in recent follow-up studies [19, 20]. Next, Myosin heavy chain 7 (MYH7) p.E1883K variant was detected in an HCM-affected Domestic Shorthair cat [21]. This amino acid mutation has also been reported to be associated with the human HCM [22]. Finally, a mutation recently identified in the HCM-affected Sphynx population belongs to Alstrom syndrome protein 1 (ALMS1) p.G3376R and is considered Sphynx-specific because it is seldom found in more than 200 non-Sphynx cats [23]. Characteristically, ALMS1 is a ubiquitously expressed non-sarcomeric gene [24]. Therefore, studies on HCM-associated genetic variants can help understand HCM risk in advance using genetic testing. However, these mutations are determined to be breed-specific, and the feline HCM guidelines of the Consensus Statements of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine do not recommend genetic testing for MYBPC3 p.A31P and p.R820W in cats not belonging to Maine Coon and Ragdoll breed [9].

HCM-associated variants have been analyzed occasionally in non-specific breeds that often lead to HCM development. Furthermore, studies in the U.S. have yet to find evidence of variants being universally present among breeds [19, 23, 25]. Additionally, only a single study of a large European feline population reported the presence of MYBPC3 p.A31P in one of the two British Longhair cats besides Maine Coon; however, the findings appeared insufficient to contradict the conclusion that the mutation is specific to Maine Coon [26]. Moreover, the information available on HCM-related variants in a wide variety of breeds is still inadequate because of population and breed biases. For example, genome-wide comparisons of 13 pedigrees and random-bred populations between the U.S. and Japan showed differences in the genetic structure of the majority of pedigrees [27]. Therefore, the genetic structure of breeds often differs between populations owing to differences in the historical lineage and inbreeding levels. In this study, we aimed to verify the spread of HCM-associated variants across broad cat breeds. In addition, we addressed the issue of population bias by using a Japanese population instead of a Western population, which is commonly used in similar studies.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All clinical examinations were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use of Nippon Veterinary and Life Science University in Japan (No. R2-4). Written informed consent authorizing participation in the study was obtained from the cat owners. All swab samples from cats were taken with their consent for genetic testing and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Anicom Speciality Medical Institute Inc. (No. 2022–06 & No. 2022–02).

Phenotyping of selected animals

Seventy-six client-owned cats (63 purebred cats belonging to 13 breeds and 13 Japanese random-bred) underwent complete physical examination, electrocardiography, thoracic radiography, blood pressure measurement, and transthoracic echocardiography. Among them, 57 cats (52 purebred cats belonging to 13 breeds and 5 Japanese random-bred) were diagnosed with HCM (HCM-affected group), while the other 19 cats (11 purebred cats belonging to 4 breeds and 8 Japanese random-bred) were not affected by HCM (non-HCM group). We diagnosed HCM based on echocardiographic evidence of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy and the absence of other diseases that cause LV hypertrophy. Echocardiographic LV hypertrophy was confirmed according to the LV wall thickness of ≥ 6 mm at end-diastole, as measured using B-mode echocardiography. LV thickness was calculated from the short-axis view, and the mean values of the thickest segment obtained in three consecutive cardiac cycles were used [28].

Furthermore, 229 additional cats (95 Munchkin, 132 Scottish Fold, and 2 Minuet) without a known phenotypic myocardium status were used for allele frequency analysis. The cats were either client-owned with genetic testing done at Anicom Pafe Inc. (Japan) or were neutered at Shinjuku Gyoenmae Animal Hospital. These additional cats were not associated with any specific disease and were included as the general group. All owners provided informed consent to use their cat-specific data for scientific research.

Genotyping

The genomic DNA of each cat was extracted from whole blood or buccal swab samples or reproductive tissues removed by castration. DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Netherlands) was used for DNA extraction from reproductive tissues and blood according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Likewise, Chemagic ™ DNA Buccal Swab Kit (PerkinElmer, U.S.) and DNAdvance Kit (Beckman Coulter, U.S.) were used for DNA extraction from the oral mucosal tissue. The extracted DNA samples were used to identify MYBPC3 (p.A31P, p.R820W, and p.A74T), MYH7 (p.E1883K), and ALMS1 (p.G3376R) variants. The genotypes of MYBPC3 p.A31P and p.R820W were confirmed by the Taqman assay, while the others were identified by Sanger sequencing (primers and probes are shown in S1 Table) performed at Eurofins Genomics Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). The obtained DNA sequences were aligned using MEGA 7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets [29]. The genotype of each sample was classified as wild-type (WT), heterozygous, or homozygous.

ALMS1 variant detection using public data

The publicly available whole genome data (as fastq files) were downloaded from Sequence Read Archive (SRA, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra). The downloaded data included those of 40 cats, which comprised 30 purebred cats belonging to 13 breeds and 10 random bred cats. Quality filtering of the raw fastq files was performed using trim_galore v 0.6.5 with default settings. The DRAGEN software v. 3.6 (Illumina Inc.) was used for mapping to the domestic cat genome (felCat9 [30]) and variant calling. The ALMS1 variant (A3:92,439,157) was extracted using Vcftools v 0.1.16 [31].

Statistical analysis

Differences between the HCM-affected group and the general group in terms of the presence of the ALMS1 variant, within the same breed, were detected using Fisher’s exact test using R v 4.1.2 [32]. χ-square test was not applied due to the small number of cells sampled in the 2 × 3 contingency table.

Results

Detection of genetic variants in echocardiographically examined cats

The five genetic variants were genotyped in cats that underwent echocardiography, detecting one heterozygous cat for MYBPC3 p.A31P variant and nine heterozygous cats for ALMS1 p.G3376R variant among 57 HCM-affected cats (Table 1). MYBPC3 p.A31P was identified in one of the four Munchkin cats, whereas it was not found in six Maine Coon cats. The ALMS1 p.G3376R variant was detected in three breeds: Scottish Fold (7/18 cats), Exotic Shorthair (1/3 cats), and Sphynx (1/1 cat). The HCM-affected Scottish Fold accounted for the highest proportion of HCM-affected cats in this study, which ranged from 7 months to 14 years of age (mean of 5.4 years±4.6 SD). Among these, the ALMS1 variant carriers included a wide range of cats aged between 8 and 14 years (mean of 7 years±5.1 SD); and there was no association between the ALMS1 variant and age. Additionally, a six-month-old Scottish Fold (1/1) cat was heterozygous for the MYBPC3 p.A31P variant, and two American Shorthair (2/3) cats, aged 1 and 3, were heterozygous for the ALMS1 p.G3376R variant, among the 19 non-HCM cats (Table 2).

Table 1. The number of HCM-associated variant carriers in the HCM-affected group.

| Total positive | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breed | N |

MYBPC3 p.A31P |

MYBPC3 p.R820W |

MYBPC3 p.A74T |

MYH7 p.E1883K |

ALMS1 p.G3376R |

| American Shorthair | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bengal | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| British Shorthair | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Exotic Shorthair | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1* |

| Maine Coon | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Munchkin | 4 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Norwegian Forest Cat | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ragdoll | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Random bred | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Russian Blue | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scottish Fold | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7* |

| Siberian Forest Cat | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Singapura | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sphinx | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 57 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

* indicates that the variant has never been found before in the breed.

Table 2. The number of HCM-associated variant carriers in the non-HCM group.

| Total positive | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breed | N |

MYBPC3 p.A31P |

MYBPC3 p.R820W |

MYBPC3 p.A74T |

MYH7 p.E1883K |

ALMS1 p.G3376R |

| American Shorthair | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2* |

| Maine Coon | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Munchkin | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Random bred | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scottish Fold | 1 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 19 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

* indicates that the variant has never been found before in the breed.

These results indicate the presence of the variants MYBPC3 p.A31P and ALMS1 p.G3376R in two and three new cat breeds, respectively. In addition, no homozygous MYBPC3 or ALMS1 variants were detected in the cats examined by echocardiography. Moreover, MYBPC3 p.R820W, p.A74T, and MYH7 p.E1883K were not included (Tables 1 and 2). The phenotypes obtained using echocardiography and the genotype of each variant in individual cats are presented in S2 Table. The nine ALMS1 p.G3376R positive cats were classified with seven cats in stage B1, with one in stage B2, and with one in stage C according to the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) stage classification [9]. The stage C cat showed with pleural effusion and pulmonary edema, and had syncope after excitement. Other phenotypes included four of the ALMS1 p.G3376R positive cats with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. One MYBPC3 p.A31p positive cat was classified as stage B1 and had no left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Based on the observed phenotypic variations among cats, it proved challenging to ascertain the precise association of each mutation with a particular stage of HCM.

Detection of genetic variants in non-echocardiographically examined cats

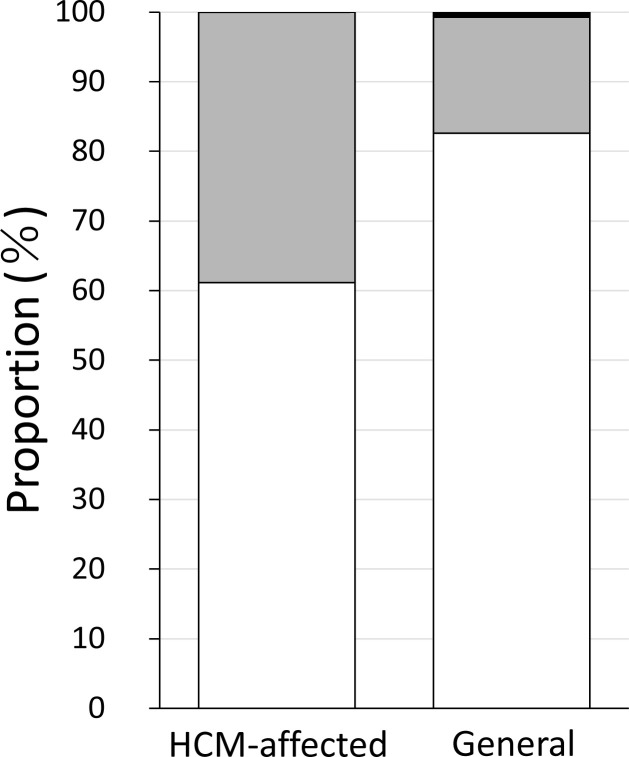

The two variants (MYBPC3 p.A31P and ALMS1 p.G3376R) detected in the first genotypic analysis were used during the second genotypic analysis of non-echocardiographically examined cats. The MYBPC3 variant was identified in Munchkin and Scottish Fold cats, while the HCM-affected Scottish Fold cats exhibited a high prevalence of the ALMS1 variant. Therefore, approximately 100 cats from each of these breeds (Munchkin; N = 95, and Scottish Fold; N = 132) were randomly selected from the general group unrelated to the specific disease and examined for the prevalence of each variant. As a result, two Munchkin and four Scottish Fold heterozygous cats for MYBPC3 p.A31P variant were detected (Table 3). The mutated allele frequencies of Munchkin and Scottish Fold breeds in the general group were 1.05% and 1.51%, respectively. Similarly, one homozygous and 22 heterozygous Scottish Fold cats carrying ALMS1 p.G3376R variant were detected in the general group (Table 3), and the allelic frequency of the variant was 9.09%. In addition, the prevalence of the ALMS1 variant in Scottish Fold cats was compared between the HCM-affected and general groups, and a statistical test was performed (Fig 1). It was proposed that a strong effect of the ALMS1 variant on HCM development would indicate a significantly higher prevalence of this variant in the HCM-affected group than in the general group, although the difference between the two groups (Fisher’s exact test; P = 0.083) was insignificant. Next, considering the possibility that the ALMS1 variant was not fully identified during the first analysis because of the small population size, we genotyped the variant in Munchkin cats, resulting in the detection of 16 Munchkin cats heterozygous for ALMS1 p.G3376R in the general group (Table 3), and the mutated allele frequency was 8.42%. Furthermore, an ALMS1 variant heterozygote was identified in the Minuet cat, a breed closely related to Munchkin (Table 3). Together, these results indicate the presence of ALMS1 p.G3376R variant in five new breeds other than Sphinx.

Table 3. The number of HCM-associated variant carriers among the Munchkin, Scottish Fold, and Minuet cats in the general group.

| Total positive | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Breed | N | MYBPC3 p.A31P | ALMS1 p.G3376R |

| Munchkin | 95 | 2 | 16 |

| Scottish Fold | 132 | 4 | 23* |

| Minuet | 2 | 0 | 1* |

The one ALMS1 p.G3376R positive Scottish Fold was a homozygous cat, and the others are heterozygous cats. Other positive cats were heterozygous.

* indicates that the variant has never been found before in the breed.

Fig 1. Comparison of the proportion of ALMS1 variant carriers in the Scottish Fold cats.

Finally, we identified the ALMS1 genotype from the publicly available cat genome to ascertain the global geographic distribution of ALMS1 p.G3376R. This dataset included purebred cats and random bred cats (Domestic Shorthair) of American, European, Asian, and Middle Eastern origin. Two heterozygous cats (one American Shorthair cat and one random bred cat) were detected, and both were of US origin (S3 Table).

The ALMS1 variant genotypes of each cat among the 18 HCM-affected and the 132 general Scottish Fold cats, were evaluated. White, gray, and black bars indicate wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous variants, respectively. There is no significant difference between the proportion of the two groups (Fisher’s exact test; P = 0.083). The detailed number of cats are presented in Tables 1 and 3.

Discussion

This study focused on determining the widespread occurrence of genetic variants associated with feline HCM in cat breeds, using HCM-affected, non-HCM, and general cat populations in Japan. MYBPC3 p.A31P was present in at least two non-Maine Coon breeds, and ALMS1 p.G3376R was detected in more than five non-Sphynx breeds. Therefore, the genetic variants involved in HCM development may not be limited to specific breeds, as previously reported.

Expansion of breeds with MYBPC3 p.A31P mutation

HCM-associated mutations in cats are usually considered breed-specific variants [10, 17, 18, 33]. Several previous studies have reported the specific association of MYBPC3 p.A31P variant with the Maine Coon breed; this variant is absent in other breeds including interbreed cats [20, 25, 33]. As an exception, carriers of this variant were found in British Longhair, but only in one of the two cats [26]. This heterozygous cat is the only MYBPC3 p.A31P positive non-Maine Coon cat for which data was available. Interestingly, our study is the first study to show the presence of this HCM-associated variant in three Munchkin and five Scottish Fold cats, expanding the range of breeds carrying the MYBPC3 p.A31P mutation. However, MYBPC3 p.A31P variant could not be the primary cause of HCM in these cats because of its low penetrance in HCM-affected breeds [34]. Additionally, one carrier Scottish Fold cat was not diagnosed with HCM, possibly because of its young age of five months at the time of diagnosis. The cat may develop HCM in the future since the preferred age for manifestation of HCM symptoms is about two to three years [8]. Moreover, several cats heterozygous for this variant have been reported to be HCM-unaffected [19]. A meta-analysis of numerous Maine Coon cats suggested an increased prevalence risk only in the homozygous condition [18]. These studies further support the presence of MYBPC3 p.A31P heterozygous cats in the non-HCM group. This study could not provide evidence for an association between the MYBPC3 p.A31P variant and the onset of HCM in non-Maine Coon breeds. However, it is clinically significant that a new non-Maine Coon breed with the MYBPC3 p.A31P variant, an established causative mutation for feline HCM, has been identified.

Association between ALMS1 p.G3376R and HCM onset

ALMS1 p.G3376R is a Sphynx-specific mutation that has been reported in a few carriers of over 200 non-Sphynx cats without known heart disease [23]. To the best of our knowledge, no other studies have associated ALMS1 with HCM in cats, and ALMS1 has not been shown to be as clearly associated with HCM as MYBPC3. This study reports the presence of ALMS1 variant in more diverse cat breeds than that reported previously. The allelic frequency of this mutation in Munchkin and Scottish Fold cats is moderate, suggesting that this variant is not specific to the Sphynx breed. In addition, on comparing the proportion of carriers of this variant in the HCM-affected and general-group Scottish Fold cats, no association between the variant and HCM development was observed. Previous studies have shown a high prevalence of this variant in the HCM-affected Sphynx breed (87.3%), although Sphynx cats from the HCM-unaffected and general population were not used [23]. Therefore, the possibility of widespread distribution of this variant in Sphynx cats unrelated to HCM cannot be excluded. However, the effect of ALMS1 variant can probably be diluted under the influence of a genetic background different from that of the Sphynx. Furthermore, only 1 homozygote and 38 heterozygote cats carrying the ALMS1 variant were observed among the 227 cats in the general group. The ratio of homozygotes was very low compared to that in a previous study in which 35 homozygotes and 27 heterozygotes were detected among 62 HCM-affected Sphynx cats [23]. Therefore, the homozygous ALMS1 p.G3376R variant could influence HCM development. Considering these findings, the association of ALMS1 variant with HCM disease should be carefully evaluated in more cat breeds.

The genetic history of MYBPC3 and ALMS1 variants

In this study, we identified HCM-related variants in breeds not previously reported. Since MYBPC3 p.A31P has not been detected in many breeds [20, 25, 33], its phylogenetic transmission from Maine Coon to a relatively new breed, such as Munchkin, over a long period is unlikely. In addition, the possibility of a de novo mutation in the same nucleotide in each breed cannot be excluded; however, it is minimal. Previous studies have shown that genomes of some Japanese Munchkin and Scottish Fold cats share the genetic component with Maine Coon breed [27]. These findings suggest outcrossing of other breed cats with MYBPC3 p.A31P-carrying Maine Coon cats. A long-hair trait further indicates the outcrossing between breeds. This is consistent with a previous study showing the presence of MYBPC3 p.A31P variant in British Longhair cats, suggesting the occurrence of Maine Coon breed in British Longhair historical lineage due to the similarity with the longhair breed [26]. Unfortunately, the information regarding cat hair length was unavailable in our study. Nevertheless, Munchkin and Scottish Fold contain long-haired cats; therefore, these cats carrying the MYBPC3 variant may share similar features. Other pure-bred cats in the Japanese population with a genetic structure similar to the Maine Coon cat include the American Curl, Persian, Siberian Forest Cat, and Norwegian Forest Cat [27]. Additional genetic analysis using a higher number of cats in these breeds may help identify MYBPC3 variant carriers and genetic history of the variants. In contrast, the theory behind the widespread occurrence of ALMS1 p.G3376R in several breeds is unclear. Considering a large gap in the appearance phenotype between the breeds, including the genetic variant-carrying Sphinx, it excludes the possibility of hybridization in recent history. The breeds that carried the ALMS1 variant in this study are of European or American origin [35, 36]. The ALMS1 variant, examined using publicly available cat genomes based on next-generation sequencing, was not detected in any Asian or Middle Eastern cat breeds (S3 Table). Therefore, a common ancestor of Western origin may have initially possessed the causative factor. Interestingly, the ALMS1 variant was not identified in the Scottish Fold cat in a previous study [23], suggesting the specific prevalence of the Scottish Fold breed carrying the ALMS1 variant in the Japanese population. Several Scottish Fold lines have different genetic structures between the Japanese and U.S. populations [27], which could be the cause of the difference in allelic frequencies of the ALMS1 variant.

Importance of investigating pathogenesis across a wide range of cat breeds and populations

This study highlights the importance of investigating the cross-breed distribution of heritable pathogenesis across cat populations. The feline HCM guidelines do not recommend genetic testing for MYBPC3 p.A31P variant in non-Maine Coon breeds because of the breed-specificity of this variant [9]. However, the variant was identified in non-Maine Coon breeds in this study (e.g., Munchkin and Scottish Fold), indicating a possibility for variant-mediated onset of HCM. Therefore, genetic testing of MYBPC3 p.A31P in non-Maine Coon breeds is a valid measure for HCM diagnosis and to prevent the establishment of HCM-affected colonies. Besides, the variants MYBPC3 p.A74T, p.R820W, and MYH7 p.E1883K were not detected in any cat in this study. The two variants MYBPC3 p.R820W and MYH7 p.E1883K have been reported only in Ragdoll cats and a Domestic Shorthair, respectively [20, 33]. However, a number of studies in the United States and Europe have identified MYBPC3 p.A74T in several breeds [19, 20, 37], supporting the importance of investigating genetic pathogenesis in different populations. This study has certain limitations, such as the younger age of the animals and the relatively small sample sizes; therefore, future research with a larger sample size would enable identifying a wider distribution of these three variants in cats. Meanwhile, a species-exhaustive study of known variants would not be sufficient to understand HCM development comprehensively. Notably, 47 out of 57 HCM-affected cats in this study did not carry any of the five variants associated with HCM. In humans, over 450 causative variants have been identified in the genes associated with sarcomeres and myofilaments related to the genetic disease HCM [38–40]. Hence, a variety of HCM-associated variants may still be identified in cats, and the prevalence of such variants should be analyzed across breeds and populations.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that variants associated with feline HCM are found in various non-specific cat breeds. The MYBPC3 p.A31P variant could be responsible for the onset of HCM in Scottish Fold and Munchkin breeds, and the ALMS1 p.G3376R variant may not occurred in a Sphynx-specific manner. The study highlights the significance of examining the prevalence of genetic variants across different populations and breeds.

Supporting information

The sequences of used primers and Taqman probes were shown.

(XLSX)

*: The stage classification method was from previous paper [9].

(XLSX)

Origins of Domestic Shorthair according to each published data. SRA Run ID denote Run ID of Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra).

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all Japanese breeders, veterinarians, and cat owners who participated in this study for collecting tissues and buccal swabs from their cats. We also thank all the staff performing genetic testing at the Anicom Specialty Medical Institute Inc. for their support. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Research Foundation of Anicom Insurance Inc. (Japan), Anicom Specialty Medical Institute Inc. (Japan), Anicom Pafe Inc. (Japan), Nippon Veterinary and Life Science University (Japan) and Azabu University (Japan). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Noriyoshi Akiyama and Yuki Matsumoto received a salary from Anicom Specialty Medical Institute Inc. and Anicom Pafe Inc. Yuki Matsumoto also received a salary from Azabu University. Ryohei Suzuki received a salary from Nippon Veterinary and Life Science University. Hisashi Ukawa received a salary from Anicom Pafe Inc. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section.

References

- 1.Ferasin L, Sturgess CP, Cannon MJ, Caney SMA, Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Wotton PR. Feline idiopathic cardiomyopathy: a retrospective study of 106 cats (1994–2001). J Feline Med Surg. 2003; 5: 151–159. doi: 10.1016/S1098-612X(02)00133-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Côté E, Manning AM, Emerson D, Laste NJ, Malakoff RL, Harpster NK. Assessment of the prevalence of heart murmurs in overtly healthy cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004; 225: 384–388. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.225.384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paige CF, Abbott JA, Elvinger F, Pyle RL. Prevalence of cardiomyopathy in apparently healthy cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009; 234: 1398–1403. doi: 10.2460/javma.234.11.1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner T, Fuentes VL, Payne JR, McDermott N, Brodbelt D. Comparison of auscultatory and echocardiographic findings in healthy adult cats. J Vet Cardiol. 2010; 12: 171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Payne JR, Brodbelt DC, Luis Fuentes V. Cardiomyopathy prevalence in 780 apparently healthy cats in rehoming centres (the CatScan study). J Vet Cardiol. 2015; 17 Suppl 1: S244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Payne JR, Borgeat K, Brodbelt DC, Connolly DJ, Luis Fuentes V. Risk factors associated with sudden death vs. congestive heart failure or arterial thromboembolism in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Vet Cardiol. 2015; 17 Suppl 1: S318–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2015.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkie LJ, Smith K, Luis Fuentes V. Cardiac pathology findings in 252 cats presented for necropsy; a comparison of cats with unexpected death versus other deaths. J Vet Cardiol. 2015; 17 Suppl 1: S329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox PR, Keene BW, Lamb K, Schober KA, Chetboul V, Luis Fuentes V, et al. International collaborative study to assess cardiovascular risk and evaluate long-term health in cats with preclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and apparently healthy cats: The REVEAL Study. J Vet Intern Med. 2018; 32: 930–943. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luis Fuentes V, Abbott J, Chetboul V, Côté E, Fox PR, Häggström J, et al. ACVIM consensus statement guidelines for the classification, diagnosis, and management of cardiomyopathies in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2020; 34: 1062–1077. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meurs KM, Norgard MM, Ederer MM, Hendrix KP, Kittleson MD. A substitution mutation in the myosin binding protein C gene in ragdoll hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Genomics. 2007; 90: 261–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Granström S, Godiksen MTN, Christiansen M, Pipper CB, Willesen JL, Koch J. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a cohort of British Shorthair cats in Denmark. J Vet Intern Med. 2011; 25: 866–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.0751.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chetboul V, Petit A, Gouni V, Trehiou-Sechi E, Misbach C, Balouka D, et al. Prospective echocardiographic and tissue Doppler screening of a large Sphynx cat population: reference ranges, heart disease prevalence and genetic aspects. J Vet Cardiol. 2012; 14: 497–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trehiou-Sechi E, Tissier R, Gouni V, Misbach C, Petit AMP, Balouka D, et al. Comparative echocardiographic and clinical features of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in 5 breeds of cats: a retrospective analysis of 344 cases (2001–2011). J Vet Intern Med. 2012; 26: 532–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2012.00906.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borgeat K, Casamian-Sorrosal D, Helps C, Luis Fuentes V, Connolly DJ. Association of the myosin binding protein C3 mutation (MYBPC3 R820W) with cardiac death in a survey of 236 Ragdoll cats. J Vet Cardiol. 2014; 16: 73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.März I, Wilkie LJ, Harrington N, Payne JR, Muzzi RAL, Häggström J, et al. Familial cardiomyopathy in Norwegian Forest cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2015; 17: 681–691. doi: 10.1177/1098612X14553686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kittleson MD, Meurs KM, Munro MJ, Kittleson JA, Liu SK, Pion PD, et al. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Maine Coon cats: an animal model of human disease. Circulation. 1999; 99: 3172–3180. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.24.3172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meurs KM, Sanchez X, David RM, Bowles NE, Towbin JA, Reiser PJ, et al. A cardiac myosin binding protein C mutation in the Maine Coon cat with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2005; 14: 3587–3593. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gil-Ortuño C, Sebastián-Marcos P, Sabater-Molina M, Nicolas-Rocamora E, Gimeno-Blanes JR, Fernández Del Palacio MJ. Genetics of feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clin Genet. 2020; 98: 203–214. doi: 10.1111/cge.13743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wess G, Schinner C, Weber K, Küchenhoff H, Hartmann K. Association of A31P and A74T polymorphisms in the myosin binding protein C3 gene and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Maine Coon and other breed cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2010; 24: 527–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0514.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longeri M, Ferrari P, Knafelz P, Mezzelani A, Marabotti A, Milanesi L, et al. Myosin-binding protein C DNA variants in domestic cats (A31P, A74T, R820W) and their association with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Vet Intern Med. 2013; 27: 275–285. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schipper T, Van Poucke M, Sonck L, Smets P, Ducatelle R, Broeckx BJG, et al. A feline orthologue of the human MYH7 c.5647G>A (p.(Glu1883Lys)) variant causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a Domestic Shorthair cat. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019; 27: 1724–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armel TZ, Leinwand LA. Mutations in the β-myosin rod cause myosin storage myopathy via multiple mechanisms. PNAS. 2009; 106: 6291–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meurs KM, Williams BG, DeProspero D, Friedenberg SG, Malarkey DE, Ezzell JA, et al. A deleterious mutation in the ALMS1 gene in a naturally occurring model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the Sphynx cat. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021; 16: 108. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01740-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hearn T, Renforth GL, Spalluto C, Hanley NA, Piper K, Brickwood S, et al. Mutation of ALMS1, a large gene with a tandem repeat encoding 47 amino acids, causes Alström syndrome. Nat Genet. 2002; 31: 79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fries R, Heaney AM, Meurs KM. Prevalence of the myosin-binding protein C mutation in Maine Coon cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2008; 22: 893–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mary J, Chetboul V, Sampedrano CC, Abitbol M, Gouni V, Trehiou-Sechi E, et al. Prevalence of the MYBPC3-A31P mutation in a large European feline population and association with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the Maine Coon breed. J Vet Cardiol. 2010; 12: 155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto Y, Ruamrungsri N, Arahori M, Ukawa H, Ohashi K, Lyons LA, et al. Genetic relationships and inbreeding levels among geographically distant populations of Felis catus from Japan and the United States. Genomics. 2021; 113: 104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki R, Mochizuki Y, Yuchi Y, Yasumura Y, Saito T, Teshima T, et al. Assessment of myocardial function in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy cats with and without response to medical treatment by carvedilol. BMC Vet Res. 2019; 15: 376. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-2141-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016; 33: 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang W, Schoenebeck JJ. The ninth life of the cat reference genome, Felis_catus. PLoS Genet. 2020; 16: e1009045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, DePristo MA, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011; 27: 2156–2158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Team RC, Team RDC. R (2019) A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. R Core Team. [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Donnell K, Adin D, Atkins CE, DeFrancesco T, Keene BW, Tou S, et al. Absence of known feline MYH7 and MYBPC3 variants in a diverse cohort of cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Anim Genet. 2021; 52: 542–544. doi: 10.1111/age.13074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyons LA. Genetic testing in domestic cats. Mol Cell Probes. 2012; 26: 224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipinski MJ, Froenicke L, Baysac KC, Billings NC, Leutenegger CM, Levy AM, et al. The ascent of cat breeds: genetic evaluations of breeds and worldwide random-bred populations. Genomics. 2008; 91: 12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Firdaus I. The complete cat breed book: choose the perfect cat for you. Dorling Kindersley Ltd; 2021. 256 p. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demeekul K, Sukumolanan P, Panprom C, Thaisakun S, Roytrakul S, Petchdee S. Echocardiography and MALDI-TOF identification of myosin-binding protein C3 A74T gene mutations involved healthy and mutated Bengal cats. Animals (Basel). 2022; 12: 1782. doi: 10.3390/ani12141782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bos JM, Ommen SR, Ackerman MJ. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: one, two, or more diseases? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007; 22: 193–199. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3280e1cc7f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alcalai R, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: from bench to the clinics. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008; 19: 104–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00965.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keren A, Syrris P, McKenna WJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the genetic determinants of clinical disease expression. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008; 5: 158–168. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]