Abstract

Recent years have seen growing interest in neuropalliative care as a subspecialty. Simultaneously, the rise of narrative medicine in patient support groups and clinician training programs offers a way to listen deeply to the stories of those living with chronic illness and may inform corresponding health interventions. This commentary examines the ways in which an understanding of illness narrative schemata, particularly the so-called “chaos narrative,” can contribute to patient and care partner distress, which in turn can be alleviated by a palliative care approach. Through examples of stories of people with Parkinson disease and their care partners, the article emphasizes the intersections between narrative medicine, neurology, and palliative care. Specific opportunities for bringing narrative medicine into the clinic are discussed.

Over the past decade, palliative care (PC) has been increasingly incorporated into Parkinson disease (PD) care.1 PC models have the capacity to improve quality of life for people with Parkinson (PWP) and their care partners at all stages of the disease.1,2 The central principles of PC address hallmarks of illness progression for PWP with techniques that promote compassionate and empathetic care, defining goals of care, care partner support, holistic well-being, and shared decision-making.3-6 Given the concordance between the needs of PWP and the offerings of PC, narrative medicine is a highly relevant conceptual model that informs specific health interventions for integrating PC into the care of PWP.

Narrative medicine (NM) emphasizes personal and collective narratives and storytelling as active methods of meaning-making7,8; clinicians who are skillful at NM can bridge clinician-patient communication gaps and improve quality of patient-centered care.9 NM frameworks are often compatible with and improve outcomes in PC, oncology,10 psychiatry,11 and intensive care.12 The term “narrative medicine” is used to refer to both an approach to understanding illness and related health interventions. This paper refers to the former as “NM” or “NM frameworks” and the latter as “NM interventions” for clarity. A representative and relevant example of this dual definition is reported by Vanstone et al.12 within an ICU context; their study uses NM to understand the nonlinear, fluid personal, and collective narratives experienced by patients and families in times of crisis, and it also examines the successful implementation of an NM intervention—a Word Cloud project. However, there are few studies examining the role of NM in neuropalliative care of PWP, especially given the ways that NM and NM interventions as reported in the literature can help patients and care partners navigate uncertainty, chronicity, and dying. This article will bring PD, PC, and NM into discussion and comment on the potential value of incorporating evidence-based NM interventions into palliative treatment plans for PWP.

Parkinson Disease as a Chaos Narrative

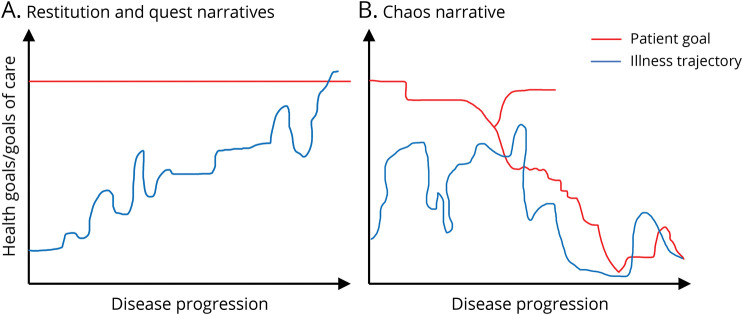

Before examining PD experiences and treatments with narrative lenses, it is necessary to define 3 types of illness narratives as the foundation for NM frameworks: restitution, quest, and chaos7 (Figure 1). Restitution narratives describe a clear illness-to-cure trajectory, characterized by concrete hope of medical healing and restoration. Quest narratives accept illness as a journey through which enlightenment and/or personal growth may be gained. In Western society, these 2 types of narratives are well-tolerated, largely because of their underlying sense of hope.7 By contrast, a chaos narrative is characterized by hopelessness and despair and lacks order, plot, predictability, or optimism.7,13 Chaos narratives are not well-tolerated because of their antinarrative properties and dearth of hope or positive potential.7,8

Figure 1. Chronic Illness Narrative Structures.

Arthur Frank7's 3 narrative types as modified dramatic structure diagrams. (A) The trajectory of a patient whose illness is conducive to a restitution or quest narrative. The patient's goal remains constant and is ultimately attainable. (B) The more complex, tortuous nature of an illness trajectory characterized by chaos. The patient goal is nonlinear and in constant flux, and the bifurcation point represents a point in time where the patient has multiple goals, one of which is above the illness trajectory curve (portraying attainability) and one of which is below the illness trajectory curve (portraying unattainability).

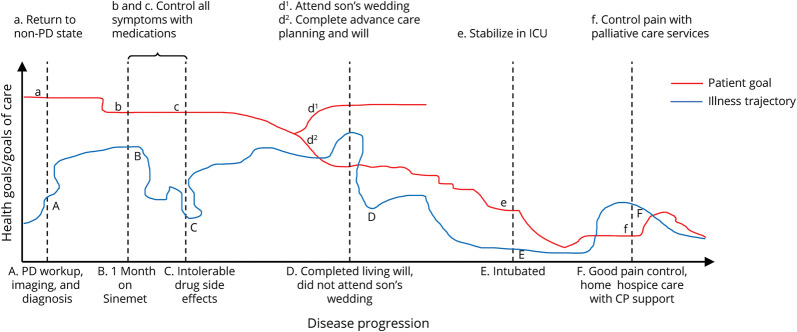

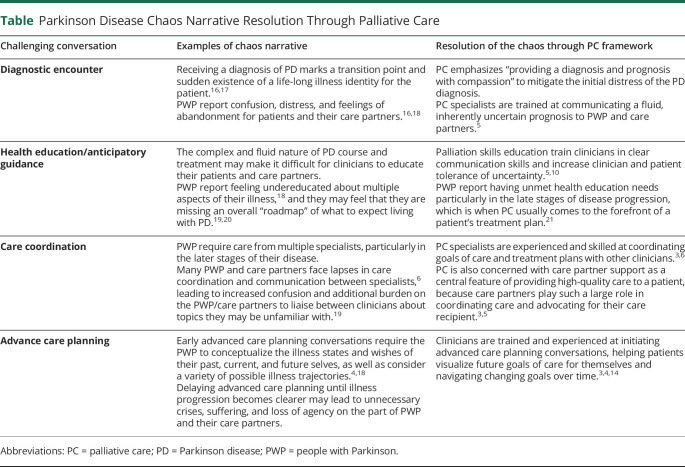

A patient-centered, nuanced understanding of the potential roles of PC in PD treatment benefits greatly from situating PD illness experiences within these narrative frameworks. The chronicity, unpredictability, and degenerative nature of PD align strongly with the hallmark features of a chaos narrative and results in the loss of key narrative features of medicine—temporality, linear plot, and intersubjectivity of shared human experiences (Figure 2).13 The neurodegenerative nature of PD progression continually disrupts a patient's conceptualizing of past, present, and future selves.14 Living with PD involves frequent identity re-evaluations because of ever-changing symptoms, treatments, and goals of care15; succinctly, “…the trajectory of the disease is uncertain, but change is inevitable.”16 Potential areas of improvement in PD treatment are repeatedly identified by PWP, care partners, and clinicians as moments of high PC need in previous literature, and examining 4 selected challenges through Frank NM lens reveals the relevance of chaos narratives in perpetuating difficult illness experiences of PWP and care partners (Table).

Figure 2. A Parkinson Disease Chaos Narrative.

This graph applies the chaos narrative framework from Figure 1B to an imagined, representative PD illness course (the x-axis label is displayed to the right of the axis for ease of annotation). Each vertical marker marks a point in a patient's PD journey—points on the illness trajectory curve are marked with a capital letter and described at the bottom of the graph, and points on the patient goal curve are marked with a corresponding lower-case letter and described at the top of the graph. Vertical markers where the patient goal surpasses the illness trajectory represent times where a patient's PD progression is limiting them from reaching their health goal. For example, at point b, the patient's goal is to control all their symptoms on medication, but point B on the illness trajectory curve shows that the Sinemet is providing only partial relief. Vertical markers where the illness trajectory surpasses the patient goal represent points when a patient is surpassing their health goals. For example, at point f, the patient's goal is to control their pain, but point F on the illness trajectory curve shows that their pain is not only controlled but they are also benefiting from home hospice with their care partner support.

Table.

Parkinson Disease Chaos Narrative Resolution Through Palliative Care

Palliative Care and Narrative Implications

The benefits of incorporating PC into an integrated, holistic approach to PD treatment are well-documented.3,5 The Neuropalliative Summit established in 2017 that a key clinical priority was “to develop and implement effective models to integrate palliative care into neurology.”5 NM frameworks are highly relevant to integrating PC into PD.10 The conceptual compatibility of NM frameworks and PC and the evidence-based success of NM interventions in other fields provide a compelling foundation for investigating ways to effectively integrate PC into PD.

Previous literature has identified common, chaotic themes in the lives of PWP, including but not limited to constant uncertainty, stigma, life disruption, cognitive decline, changes in interpersonal relationships, and changing identities.15,22 PC interventions address some of these chaotic elements, emphasizing nonabandonment, psychosocial and spiritual support, holistic well-being, care partner support, patient empowerment, and clear, empathetic clinician-patient communication.3,5 This directly mitigates some of the unpredictability and uncertainty that PD chaos narratives introduce and perpetuate; it allows PWP and care partners to regain some narrative control. The Table considers the effects of PC on the 4 chaos-promoting challenges identified in the previous section.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This article has examined the benefits of incorporating NM frameworks into the care of PWP. Building on previous literature that supports incorporation of PC into an interdisciplinary PD treatment approach, even in early disease stages, this article posits that NM offers additional insight into PD illness experiences, particularly as related to meaning-making and illness trajectories. These topics are important and central in PC, and given this congruence, there is an opportunity for this narrative understanding of PD experiences and illness identities to translate into appropriate, specific NM interventions in neuropalliative care.

Existing literature offers insight into replicable NM interventions that can be tailored around the PD chaos narrative to provide high-quality health care to PWP and support for their care partners, particularly in the context of neuropalliative care. One NM intervention from the University of Alberta demonstrably improved the self-reported health-related quality of life and mental health of PWP using discussion groups, arts-based expression, and storytelling.23 Another promising NM intervention was a longitudinal NM program for PWP, care partners, and clinicians that included readings and discussion, writing exercises, and group reflection. The study showed increased clinician empathy and decreased depression in PWP.24 PD-PC–specific modifications to both of these interventions could include patient education, including readings and discussions, about types of storytelling, the 3 types of illness narratives (quest, restitution, and chaos), writing or art activities that prompt patients to reflect on goals of care, comfort care, and palliation, and also engage with their past, present, and future selves.25 Finally, word clouds, as a visual representation of verbal storytelling, can capture a holistic, narrative-driven picture of each patient, provide significant relief and pastoral care for families, and improve satisfaction with clinicians.12 This intervention could be beneficial for PWP as a method of capturing and preserving the patient's identity throughout the ensuing PD chaos narrative. It could also be used as a patient-centered tool for guiding early advanced care planning conversations and discussions about PC.

Apart from adapting some of the NM interventions detailed above, there are other ways that PD clinicians can incorporate this research about the benefits of NM frameworks and interventions for PWP who are receiving or will ultimately receive PC. Clinicians should pursue formalized training to improve narrative competency involving readings, written reflections, and oral discussions that address core elements of the PD chaos narrative.10 In addition, nonpalliative clinicians should seek guidance from palliative specialists and encourage patient-PC clinician conversations from early on in the disease course to promote a shared NM-centered understanding of the ensuing PD chaos narrative and initiate identity-based and goals of care discussions early on. Finally, clinicians should consider methods for tracking the progression of a patient's personal chaos narrative in their medical records to facilitate ongoing, narrative-based discussions between the patient and clinician.

This research also has important implications for other neurologic conditions. Chaos narratives characterize virtually all neurodegenerative illnesses for similar reasons to PD—unpredictability, changing identities, and chronic decline. Neurologists who practice outside the field of PD, especially those who treat patients receiving PC, should consider whether the recommendations in the previous 2 paragraphs may be applicable and beneficial to their own patients. Future research in this field would do well to examine narratives that characterize degenerative and nondegenerative neurologic conditions and determine the applicability of NM interventions. Studies that assess the delivery of NM interventions based on the type of clinician who delivers them (medical or nonmedical; palliative or nonpalliative) would also be informative for further clarifying the relationships between NM, NM interventions, and PC. Modern, interdisciplinary treatment guidelines for PWP make clear the importance of PC incorporation in standard, high-quality care, with evidence-based justifications that align with NM frameworks and a PD-specific chaos narrative. NM interventions are appropriate in PD treatment, and likely many other neurologic diseases, for reducing the distress that characterizes the experiences of many PWP and care partners and allows patients to regain some control over their chaos narrative.

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

This work was funded by the University of Rochester award “Implementing Team-based Outpatient Palliative Care in Parkinson Foundation Centers of Excellence” (DI-2019C2-17499).

Disclosure

E.D. Trahair reports no disclosures relevant to this manuscript; S. Mantri reports research support from the University of Rochester award “Implementing Team-based Outpatient Palliative Care in Parkinson Foundation Centers of Excellence” (DI-2019C2-17499). Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Kluger BM, Dolhun R, Sumrall M, Hall K, Okun MS. Palliative care and Parkinson's disease: time to move beyond cancer. Mov Disord. 2021;36(6):1325-1329. doi: 10.1002/mds.28556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kluger BM, Fox S, Timmons S, et al. Palliative care and Parkinson's disease: meeting summary and recommendations for clinical research. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;37:19-26. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaughan CL, Kluger BM. Palliative care for movement disorders. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2018;20(1):2. doi: 10.1007/s11940-018-0487-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sokol LL, Young MJ, Paparian J, et al. Advance care planning in Parkinson's disease: ethical challenges and future directions. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2019;5(1):24. doi: 10.1038/s41531-019-0098-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creutzfeldt CJ, Kluger B, Kelly AG, et al. Neuropalliative care: priorities to move the field forward. Neurology. 2018;91(5):217-226. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000005916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanoix M. Palliative care and Parkinson's disease: managing the chronic-palliative interface. Chronic Ill. 2009;5(1):46-55. doi: 10.1177/1742395309102819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank AW. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics, 2nd ed. The University of Chicago Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith B, Sparkes AC. Exploring multiple responses to a chaos narrative. Health. 2011;15(1):38-53. doi: 10.1177/1363459309360782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charon R. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanocha N. Lessons in stories: why narrative medicine has a role in pediatric palliative care training. Children. 2021;8(5):321. doi: 10.3390/children8050321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyerson JL, O'Malley KA, Obas CE, Hinrichs KLM. Lived experience: a case-based review of trauma-informed hospice and palliative care at a veterans affairs medical center. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022;40(3):329-336. doi: 10.1177/10499091221116098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanstone M, Toledo F, Clarke F, et al. Narrative medicine and death in the ICU: word clouds as a visual legacy. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2016. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mantri S, Klawson E, Albert S, et al. The experience of care partners of patients with Parkinson's disease psychosis. PLOS ONE 2021;16(3):e0248968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sokol LL, Lum HD, Creutzfeldt CJ, et al. Meaning and dignity therapies for psychoneurology in neuropalliative care: a vision for the future. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(9):1155-1156. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sylvie G, Farré Coma J, Ota G, et al. Co-Designing an integrated care network with people living with Parkinson's disease: from patients' narratives to trajectory analysis. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(14):2585-2601. doi: 10.1177/10497323211042605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peek J. ‘There was no great ceremony’: patient narratives and the diagnostic encounter in the context of Parkinson's. Med Humanit. 2017;43(1):35-40. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2016-011054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vann-Ward T, Morse JM, Charmaz K. Preserving self: theorizing the social and psychological processes of living with Parkinson disease. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(7):964-982. doi: 10.1177/1049732317707494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boersma I, Jones J, Carter J, et al. Parkinson disease patients' perspectives on palliative care needs. Neurol Clin Pract. 2016;6(3):209-219. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prizer LP, Gay JL, Wilson MG, et al. A mixed-methods approach to understanding the palliative needs of Parkinson's patients. J Appl Gerontol. 2020;39(8):834-845. doi: 10.1177/0733464818776794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordan SR, Kluger B, Ayele R, et al. Optimizing future planning in Parkinson disease: suggestions for a comprehensive roadmap from patients and care partners. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(S1):S63–S74. doi: 10.21037/apm.2019.09.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giles S, Miyasaki J. Palliative stage Parkinson's disease: patient and family experiences of health-care services. Palliat Med. 2009;23(2):120-125. doi: 10.1177/0269216308100773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haahr A, Kirkevold M, Hall EOC, Østergaard K. Living with advanced Parkinson's disease: a constant struggle with unpredictability. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(2):408-417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murdoch KC, Larsen D, Edey W, et al. The efficacy of the Strength, Hope and Resourcefulness Program for people with Parkinson's disease (SHARP-PWP): a mixed methods study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020;70:7-12. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gross N, Nicolas M, Neigher S, et al. Planning a patient-centered Parkinson's disease support program: insights from narrative medicine. Adv Parkinson's Dis. 2014;03(04):35-39. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thurston A. Cases: the use of narrative medicine in existential distress. November 23, 2015. Accessed October 22, 2022. https://www.pallimed.org/2015/11/cases-use-of-narrative-medicine-in.html. [Google Scholar]