Abstract

Background

Blood culture-negative infective endocarditis is a potentially severe disease that can be associated with infectious agents such as Bartonella spp., Coxiella burnetti, Tropheryma whipplei, and some fungi.

Case presentation

Reported here are two cases of blood culture-negative infective endocarditis in patients with severe aortic and mitral regurgitation in Brazil; the first case is a 47-year-old white man and the second is a 62-year-old white woman. Bartonella henselae deoxyribonucleic acid was detectable in the blood samples and cardiac valve with vegetation paraffin-fixed tissue samples. Additionally, an investigation was carried out on patients’ pets, within the context of One Health, and serum samples collected from cats and dogs were reactive by indirect immunofluorescence assay.

Conclusions

Even though the frequency of bartonellosis in Brazil is unknown, physicians should be aware of the possibility of blood culture-negative infective endocarditis caused by Bartonella, particularly in patients with weight loss, kidney changes, and epidemiological history for domestic animals.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13256-023-03839-8.

Keywords: Endocarditis, Bartonella, Pets, One Health, Case report

Background

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a life-threatening systemic infectious disease in which a multidisciplinary group of specialists is required for patient treatment and follow-up. Viridans streptococci, Streptococcus bovis, Haemophilus spp., Aggregatibacter spp., Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, and Kingella spp. (HACEK) group, Staphylococcus aureus, or community-acquired enterococci are classic typical microorganisms causing IE, an infection associated with the proliferation of microorganisms on the endocardium [1]. Vegetation is the prototypic lesion of IE, which can be identified by a mass of platelets, fibrin, and microcololia of bacteria, fungi, or other germs and scant inflammatory cells. The vegetation of IE is located on the mural endocardium and analogous processes can occur in intracardiac devices, arteriovenous shunts, or coarctation of the aorta [2]. The risk factors of IE involve patients with predisposing heart conditions and comorbidities, including intravenous drug use, among other factors [3]. The diagnosis of IE is established according to the modified Duke criteria [1, 4], which include predisposing heart condition or intravenous drug use, symptoms such as fever ≥ 38 °C, vascular phenomena, immunologic phenomena, and serologic evidence of active infection consistent with IE or positive blood culture but not meeting major criteria [1, 2, 4, 5]. Major modified Duke criteria, in addition to including the persistently positive blood culture and evidence of endocardial involvement, now include positive serology for Coxiella burnetii and Bartonella spp.

At least two separated positive blood cultures samples, with typical microorganisms, are required to meet major microbiological criteria. Gram-negative bacillus such as Bartonella spp., C. burnetti, and Tropheryma whipplei, some fungi such as Aspergillus spp. and Histoplasma must be searched when facing blood culture-negative infective endocarditis (BCNIE), since these etiological agents are harder to be cultivated in vitro [6–9]. Specifically, C. burnetti, Bartonella quintana, and Bartonella henselae are not easy to isolate in blood cultures, and classic Duke criteria do not identify patients with IE.

In this context, serological and molecular methods have become an important tool in the detection of C. burnetti and Bartonella spp. in the last decades in Brazil. The genus Bartonella is recognized as the second most frequent etiological agent in HACEK group, non-HACEK groups, and BCNIE. B. henselae is the most prevalent of the 14 species of associated with Bartonella endocarditis. This species is also known to be the main cause of cat scratch disease (CSD), a typical zoonotic disease in Brazil [10]. Although domestic cats and their ectoparasites are often found as hosts of B. henselae [11–13], dogs have also been reported to host this species [14, 15].

The risk is not limited to clinical cases in humans; dogs and cats can also develop cardiac complications related to infection by Bartonella [10, 16–20]. Bartonellosis is a disease of medical and veterinary importance, so One Health becomes a strategy to approach this epidemiological context. The One Health approach integrates a multidisciplinary team of researchers from different areas of knowledge to cooperate in the diagnosis, prevention, treatment, and mitigation of infection diseases [21]. The most common health professionals are typically physicians, veterinarians, and biologists linking human, animal, and environmental health [21]. Thus, the One Health epidemiological approach, such as in this study, could make more data available in the IE scenario associated with zoonoses [19].

In Brazil, where most cases of endocarditis are found in the Southeast region, we still have few epidemiological data on Bartonella endocarditis, although we have been working on retrospective studies since 2006 [5, 8, 9, 22–24]. The aim of this report is to show two cases of B. henselae endocarditis associated with Bartonella-infected domestic animals during the COVID-19 pandemic in Rio de Janeiro, in the southeast region of Brazil. We considered the modified Duke criteria to establish the diagnosis of IE caused by Bartonella, including the presence of titer Immunoglobulin type G (IgG) antibodies against Bartonella spp. ≥ 800 of dilution and a positive result of molecular testing obtained from cardiac valve and blood samples.

Case presentation

Patient 1

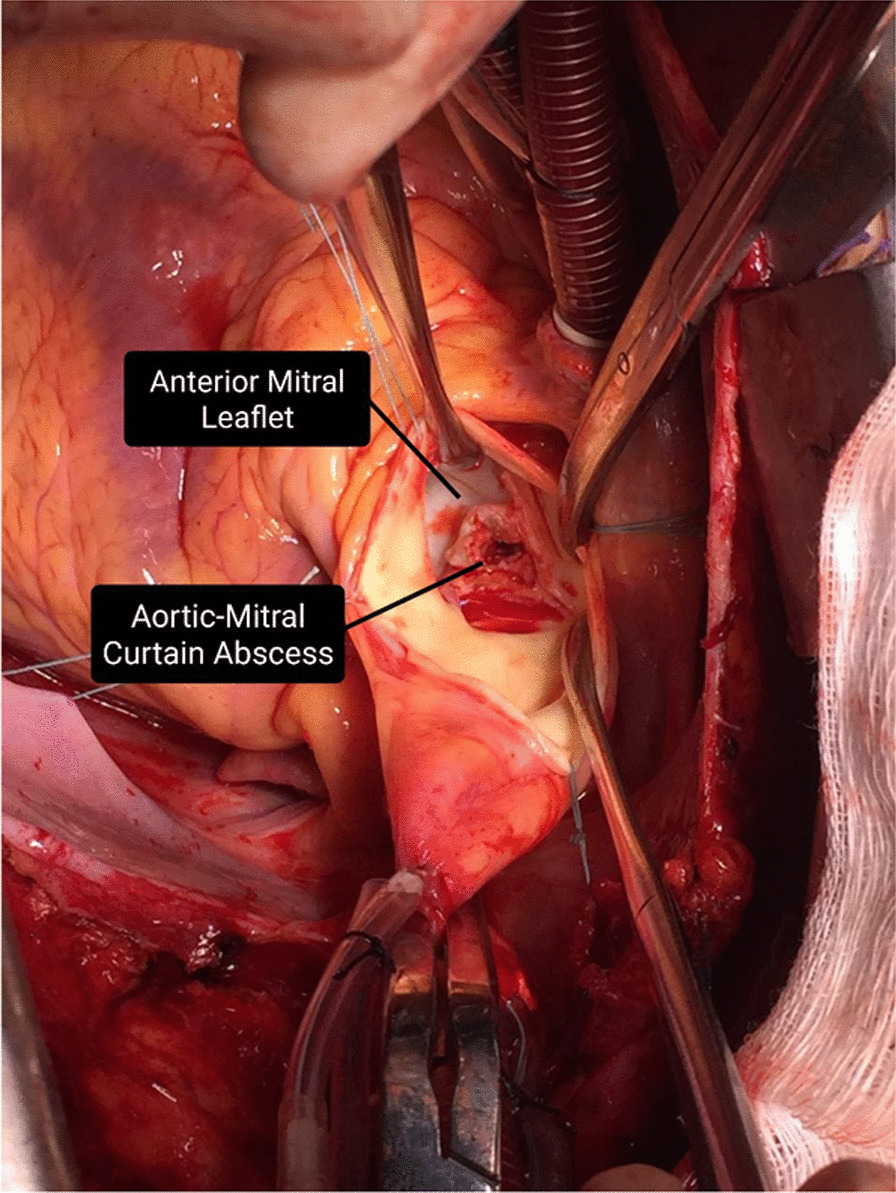

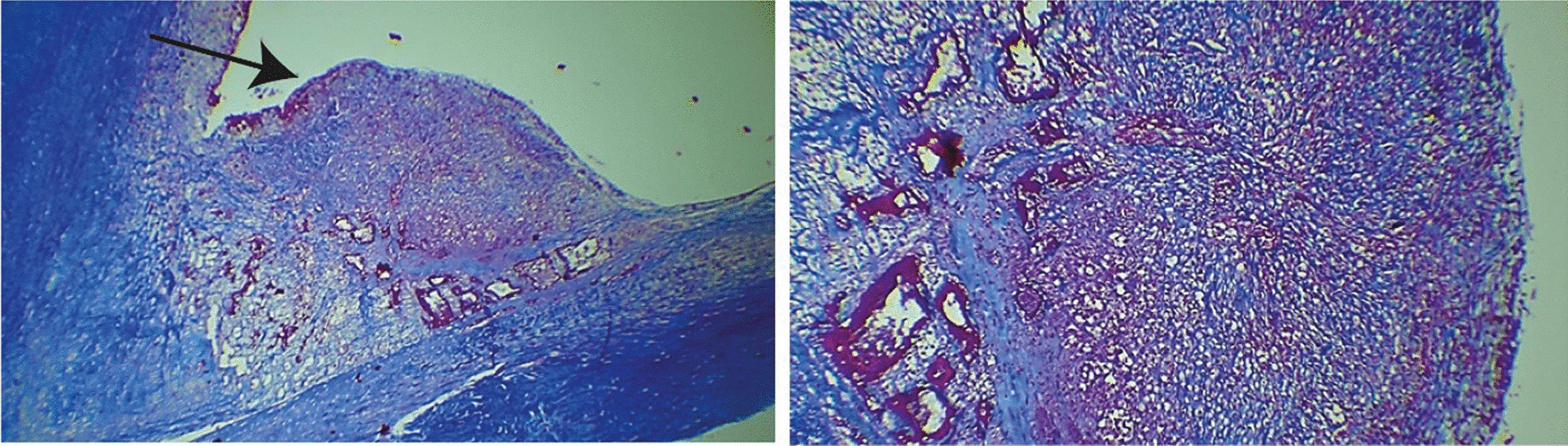

A 47-year-old white man was admitted to Pedro Ernesto University Hospital of the State of Rio de Janeiro (HUPE-UERJ) with a history of tachycardia palpitations, atrial fibrillation associated with recurrent episodes of fever, and weight loss of 3 kg in the last 40 days. At admission, he had a mild acute kidney injury, with hematuria and no proteinuria. The echocardiogram showed severe mitral and aortic stenosis associated with rheumatic valvular disease and aortic valve vegetation, with normal left and right ventricular systolic function. He was febrile and had high levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and rheumatoid factor (RF). As comorbidities, he had tooth infections and recent untreated nephrolithiasis. Three sets of blood culture samples were collected at admission, and they were all negative. Antibiotic therapy was withheld since there was no clear evidence of vegetation seen on transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). However, there was a severe aortic insufficiency with clear evidence of rheumatic valve degeneration, and due to the risk of imminent death, the patient was referred for a surgical procedure. The entire surgical procedure was performed using transesophageal echocardiography and an aortic valve was evidenced with fusion of its cusps and friable additive image, compatible with vegetation caused by infective endocarditis. The valve was resected and it was possible to see an abscess affecting the mitral aortic curtain. The mitral valve was also rheumatic and dysfunctional. The two valves were replaced uneventfully and the extracted material was sent for analysis. The collected samples were analyzed by the pathologist in the operating room, confirming the diagnostic suspicion (Fig. 1). Samples were collected and fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin for histopathological and molecular studies. The mitral and aortic valves were replaced, and the left auricle was clipped. Histological examination of the valve vegetation, preserved in 10% formalin, demonstrated the presence of inflammatory infiltrate associated with mononuclear cells and macrophages, vascular neoformation, and fibrosis (Fig. 2). After the intraoperative impression, treatment for subacute endocarditis was started with gentamicin and ampicillin.

Fig. 1.

Aortic–mitral curtain abscess visualized after resection of aortic valves: patient 1 with blood culture-negative infective endocarditis. The black arrows correspond to the pointed structures described

Fig. 2.

Left - Masson trichrome staining micrographs showing an inflammatory nodule (pointed by the arrow) in the valve vegetation of patient 1 with blood culture-negative infective endocarditis. Right – Enlarged and detailed left micrograph, showing the nodule with fibrosis, vascular neoformation, and chronic inflammatory infiltrate

Acute-phase and convalescent-phase serum samples were evaluated by an indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) for antibodies anti-Bartonella considering a cut-off titer of 64 (Additional file 1: Methods S1). The serum sample collected on first day of hospital admission, before antibiotic treatment therapy, was IFA reactive, with titer of 8192. Three other sequential serum samples were analyzed and were also reactive: (i) after antibiotic treatment, before the surgical procedure, titer of 16,384, (ii) after cardiac surgery, titer of 32,768, and (iii) at his house, titer of 2048 (Additional file 1: Table S1).

In relation to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, despite blood, serum, and plasma samples being negative, the PCR assay on the paraffin-fixed tissue samples targeting the gltA, groEL, and htrA genes were evaluated by routine of the National Reference Laboratory for Rickettsioses (NRLR), Oswaldo Cruz Institute (IOC), and Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) and segments of Bartonella genes were amplified (Additional file 1: Methods S1). The DNA sequence of gltA was similar 99.84% to KX024515 Uncultured Bartonella of domestic cat blood samples (B. henselae), the DNA sequence of groEL was similar 100% to HQ704721 B. henselae isolate of feral cat blood, and the DNA sequence of htrA was similar 100% to CP020742, B. henselae strain Houston-I (Additional file 1: Table S2).

The patient had two adult dogs, and one of them slept with him and his wife. Serum samples collected from the patient’s wife were nonreactive. Dogs were assessed by veterinarians for the presence of ectoparasites, general aspects of health, and living conditions in the home environment (Fig. 3). Blood serum samples were collected from these animals and serum samples from one of his dogs was reactive with titer of 128. The patient subsequently improved and was discharged for outpatient follow-up.

Fig. 3.

Veterinarian professional collecting blood sample from a Bartonella-serorreactive dog

Patient 2

Patient 2 is a 62-year-old white woman with a history of chronic renal disease, anemia, and reported loss of 10 kg in the last 9 months. She was admitted to the Pedro Ernesto University Hospital of the State of Rio de Janeiro (HUPE-UERJ) to explore the cause of consumptive syndrome. She had undergone a mitral valve prothesis replacement with a biological prosthesis 2 years before due to complications from rheumatic heart disease. Echocardiography revealed a dysfunctional biological mitral valve associated with rheumatic valve disease. The patient also had acute on chronic renal failure with hematuria, severe anemia, splenomegaly, paratracheal lymphadenomegaly, and arterial hypertension, associated with high levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and rheumatoid factor (RF). During hospitalization, kidney biopsy showed glomerulonephritis with crescents, tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis. Blood culture samples were all negative and the patient was treated with ceftriaxone and doxycycline. She improved and was discharged for outpatient follow-up.

Considering a possible diagnosis of IE, according to modified Duke criteria, three minor criteria blood samples were sent to the National Reference Laboratory for Rickettsioses (NRLR) to research etiologic agents associated with BCNIE (Additional file 1: Methods S1). Two serum samples were reactive to Bartonella IgG-antibodies: (i) with titers of 8192, without antibiotic treatment, and (ii) with titers of 512, subsequently after antibiotic treatment (Additional file 1: Table S1). Bartonella spp. DNA was detectable in the blood by htrA primers and this sequence of htrA was similar 99.76% to CP020742 B. henselae strain Houston-I (Additional file 1: Table S2).

During home visits, three cats were assessed by veterinarians for the presence of ectoparasites, general aspects of health, and living conditions in the home environment (Fig. 4). Subsequently, serum samples were collected from these animals, and all were reactive with titers of 128 (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Fig. 4.

Bartonella-serorreactive cat in patient 2’s house, showing the unhealthy living conditions

Discussion and conclusions

Bartonella infections occur worldwide and can be associated with blood culture-negative infective endocarditis (BCNIE). Since the first publication of infective endocarditis due to Bartonella spp. confirmed by serologic test in Brazil, few cases of this endocarditis infection have been reported, although cases of cat scratch disease (CSD) are often reported, especially in the southeast Brazilian region [8].

On the basis of clinical and diagnostic protocols in this case report, both patients met the evaluation criteria for infective endocarditis associated with blood culture-negative, a heart disease infection often severe and difficult to diagnose. In view of the inconclusive microbiological research with blood cultures, serum samples collected from the two patients and cardiac valve tissue sample (patient 1) were analyzed by both serological and molecular tests and the results confirmed infection by B. henselae. Often the Bartonella diagnosis is determined using serological tests, mainly by IFA. In this study, the patients presented high IgG-antibodies titers to Bartonella spp., a fact that allows the confirmation of BCNIE caused by this zoonotic agent exclusively by serological testing, since the IFA results with IgG titers ≥ 1:800 have a sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 99%.

Subsequent molecular analysis performed on blood and cardiac tissue (mitral valve) sample collected from patients allowed for the identification of the B. henselae species as the causative agent of BCNIE. Since 2009, the National Reference Laboratory for Rickettsioses/Ministry of Health (NRLR), Laboratory of Hantaviruses and Rickettsiosis, Oswaldo Cruz Institute, and FIOCRUZ, have been collaborating with our IE team at our teaching hospital. It is the first time we have B. henselae endocarditis in our series of 110 cases of IE defined by modified Duke criteria in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The incidence of BCNIE in this Brazilian cohort was 10.9%, although the frequency of BCNIE in review of IE in low- and middle-income countries during the years 2002–2017 ranged from 10.8–69.1% [5].

These Bartonella IE cases are a classic example of a zoonosis where a One Health approach must be applied [19]. After the confirmation of endocarditis caused by B. henselae, a multidisciplinary team carried out visits at the homes of both patients. The participation of a veterinarian allowed for the handling of domestic animals, the collection of blood samples, and the search for ectoparasites in these animals. From the epidemiological inquiry, both patients maintained very close contact with the animals, living with the pets until bedtime.

Serological investigation of domestic animals showed IgG reactivity to Bartonella spp. in the patients’ pets. Information regarding intimate contact with these pets, as well as our serological results, reinforce the likelihood of contagion through this human–pet relationship. It is interesting to consider that during the isolation caused by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, this contact between humans and their pets increased, which may have facilitated exposure to B. henselae. In this context, the presence of ectoparasites and the possibility of injury caused by scratches can facilitate the inoculation of this agent in humans [11, 26, 27].

Despite evidence of circulation of Bartonella spp. having already been reported in other studies from Rio de Janeiro [9, 28], in these case reports we indicate which bacterial species was found in these patients, which facilitates the understanding of the epidemiological aspects and the investigation of human cases from a One Health initiative [19]. The formation of a multidisciplinary team is the most effective way to identify zoonotic agents such as Bartonella that cause infections in humans and animals, also considering the non-specificity of this bacteria genus, which can be found in humans as well as in domestic and wild animals in several different environments [10, 19, 21, 29, 30].

Our two cases of Bartonella henselae infection exemplify two difficulties in defining Bartonella IE. Firstly, finding the vegetation in the valvular endocardium in the echocardiography proved to be very difficult. Secondly, although both patients had a subacute temporal course with weight loss and changes in kidney function, they did not have vascular phenomena. Bartonella endocarditis is a diagnostic challenge even for cardiac surgery referral centers. Health professionals should be alert to an atypical case of infective endocarditis, especially when patients have weight loss, kidney injury, and epidemiological history for domestic animals with ectoparasites.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Methods S1. Serological and molecular investigation. Table S1. Serological results of serum samples of the patients and their pets. Table S2. Bartonella species detected in paraffin-fixed human tissue and blood samples from Patients P1 and P2.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the patients involved for their kind participation and all the staff of the Pedro Ernesto University Hospital of the State of Rio de Janeiro and the National Reference Laboratory for Rickettsioses.

Abbreviations

- BCNIE

Blood culture-negative infective endocarditis

- IE

Infective endocarditis

- HACEK

Haemophilus spp., Aggregatibacter spp., Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, and Kingella spp.

- IgG

Immunoglobulin type G

- HUPE-UERJ

Pedro Ernesto University Hospital of State of Rio de Janeiro

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- ESR

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- RF

Rheumatoid factor

- IFA

Indirect immunofluorescence assay

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- NRLR

National Reference Laboratory for Rickettsioses

- IOC

Oswaldo Cruz Institute

- FIOCRUZ

Oswaldo Cruz Foundation

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- BLAST

Basic local alignment search tool

- CSD

Cat scratch disease

Author contributions

JGO, PVD, and ERSL wrote the manuscript; JGO, ERSL, PVD, and PFR were involved in draft correction and editing; MRSA and DEF carried out the molecular tests and methods and writing; AAPJ carried out the serological tests and methods and writing; LSS, NGR, PHD, GIFB, JFG, HMRC, and KM were responsible for the clinical team, signs and symptoms evaluation, figures and antibiotic treatment reports and writing; NSM took care of the pet handling and pet samples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Conselho Nacional para o Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), grant number 303024/2019-4 and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) grant number E-26/202.575/2019.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All sequences generated in this study are available in Genbank (MZ666121–MZ666124).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Oswaldo Cruz Institute, FIOCRUZ, number 3905610.6.0000.5248 in conformity with the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors have no disclosures to report and have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG, Tleyjeh IM, Rybak MJ, Barsic B, Lockhart PB, Gewitz MH, Levison ME, Bolger AF, Steckelberg JM, Baltimore RS, Fink AM, O’Gara P, Taubert KA. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications. Circulation. 2015;132:1435–1486. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta J-P, Del Zotti F, Dulgheru R, El Khoury G, Erba PA, Iung B, Miro JM, Mulder BJ, Plonska-Gosciniak E, Price S, Roos-Hesselink J, Snygg-Martin U, Thuny F, Tornos Mas P, Vilacosta I, Zamorano JL. ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(2015):3075–3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent LL, Otto CM. Infective endocarditis: update on epidemiology, outcomes, and management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20:86. doi: 10.1007/s11886-018-1043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, Nettles R, Fowler VG, Ryan T, Bashore T, Corey GR. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:633–638. doi: 10.1086/313753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damasco PV, Correal JC, Cruz-Campos AC, Wajsbrot BR, Cunha RG, Fonseca AG, Castier MB, Fortes CQ, Jazbick JC, Lemos ER, Rossen JW, de Souza RL, Hirata Junior R, de Mattos Guaraldi AL. Epidemiological and clinical profile of infective endocarditis at a Brazilian tertiary care center: an eight-year prospective study. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;52:1–9. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0375-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liesman RM, Pritt BS, Maleszewski JJ, Patel R. Laboratory diagnostic endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:2599–2608. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00635-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner M, Fournier P-E, Andersson R, Hogevik H, Raoult D. Bartonella and Coxiella antibodies in 334 prospectively studied episodes of infective endocarditis in Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:724–727. doi: 10.1080/00365540310015980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siciliano RF, Strabelli TM, Zeigler R, Rodrigues C, Castelli JB, Grinberg M, Colombo S, da Silva LJ, do Nascimento EM, dos Santos EM, Uip DE. Infective endocarditis due to Bartonella spp. and Coxiella burnetii: experience at a cardiology hospital in São Paulo, Brazil. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1078:215–222. doi: 10.1196/annals.1374.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.da Cruz Lamas C, Ramos RG, Lopes GQ, Santos MS, Golebiovski WF, Weksler C, Ferraiuoli GI, Fournier PE, Lepidi H, Raoult D. Raoult, Bartonella and Coxiella infective endocarditis in Brazil: molecular evidence from excised valves from a cardiac surgery referral center in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1998 to 2009. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e955–e956. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breitschwerdt EB. Bartonellosis: One Health perspectives for an emerging infectious disease. ILAR J. 2014;55:46–58. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilu015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chomel BB, Kasten RW. Bartonellosis, an increasingly recognized zoonosis. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;109:743–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guptill L. Bartonellosis. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140:347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koehler JE. Rochalimaea henselae Infection. JAMA. 1994;271:531. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510310061039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Paiva Diniz PP, Maggi R, Schwartz D, Cadenas M, Bradley J, Hegarty B, Breitschwerdt E. Canine bartonellosis: serological and molecular prevalence in Brazil and evidence of co-infection with Bartonella henselae and Bartonella vinsonii subsp. Berkhoffii. Vet Res. 2007;38:697–710. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2007023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bessas A, Leulmi H, Bitam I, Zaidi S, Ait-Oudhia K, Raoult D, Parola P. Molecular evidence of vector-borne pathogens in dogs and cats and their ectoparasites in Algiers, Algeria. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;45:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breitschwerdt EB, Maggi RG, Chomel BB, Lappin MR. Bartonellosis: an emerging infectious disease of zoonotic importance to animals and human beings. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2010;20:8–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2009.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.André MR, Canola RA, Braz JB, Perossi IF, Calchi AC, Ikeda P, Machado RZ, Vasconcelos RD, Camacho AA. Aortic valve endocarditis due to Bartonella clarridgeiae in a dog in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2019;28:661–670. doi: 10.1590/s1984-29612019078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabar M-D, Altet L, Maggi RG, Altimira J, Roura X. First description of Bartonella koehlerae infection in a Spanish dog with infective endocarditis. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:247. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2188-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breitschwerdt EB. Bartonellosis, One Health and all creatures great and small. Vet Dermatol. 2017;28:96–e21. doi: 10.1111/vde.12413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beerlage C, Varanat M, Linder K, Maggi RG, Cooley J, Kempf VA, Breitschwerdt EB. Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii and Bartonella henselae as potential causes of proliferative vascular diseases in animals. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2012;201:319–326. doi: 10.1007/s00430-012-0234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibbs EPJ. The evolution of One Health: a decade of progress and challenges for the future. Vet Rec. 2014;174:85–91. doi: 10.1136/vr.g143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siciliano RF, Castelli JB, Mansur AJ, Dos Santos FP, Colombo S, Do Nascimento EM, Paddock CD, Brasil RA, Velho PE, Drummond MR, Grinberg M, Strabelli TMV. Bartonella spp. and Coxiella burnetii associated with community-acquired, culture-negative endocarditis, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1429–1432. doi: 10.3201/eid2108.140343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamas C, Favacho A, Ramos RG, Santos MS, Ferravoli GI, Weksler C, Rozental T, Bóia MN, Lemos ERS. Bartonella native valve endocarditis: the first Brazilian case alive and well, Brazilian. J Infect Dis. 2007;11:591–594. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702007000600012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drummond MR, de Almeida AR, Valandro L, Pavan MH, Stucchi RS, Aoki FH, Velho PE. Bartonella henselae endocarditis in an elderly patient. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corrêa FG, Pontes CLS, Verzola RMM, Mateos JCP, Velho PENF, Schijman AG, Selistre-de-Araujo HS. Association of Bartonella spp bacteremia with Chagas cardiomyopathy, endocarditis and arrhythmias in patients from South America, Brazilian. J Med Biol Res. 2012;45:644–651. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2012007500082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Floyd-Hawkins K, Chi B, Yamamoto K, Roberts-Wilson J, Gurfield AN, Abbott RC, Pedersen NC, Koehler JE. Experimental transmission of Bartonella henselae by the cat flea. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1952–1956. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.8.1952-1956.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iannino F, Salucci S, Di Provvido A, Paolini A, Ruggieri E. Bartonella infections in humans dogs and cats. Vet Ital. 2018;54:63–72. doi: 10.12834/VetIt.398.1883.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamas CC, Mares-Guia MA, Rozental T, Moreira N, Favacho AR, Barreira J, Guterres A, Bóia MN, de Lemos ER. Bartonella spp. infection in HIV positive individuals, their pets and ectoparasites in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: serological and molecular study. Acta Trop. 2010;115:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regier Y, Órourke F, Kempf VAJ. Bartonella spp.—a chance to establish One Health concepts in veterinary and human medicine. Parasites Vectors. 2016;9:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1546-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kosoy M, Bai Y. Bartonella bacteria in urban rats: a movement from the jungles of Southeast Asia to metropoles around the globe. Front Ecol Evol. 2019;7:1–17. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Methods S1. Serological and molecular investigation. Table S1. Serological results of serum samples of the patients and their pets. Table S2. Bartonella species detected in paraffin-fixed human tissue and blood samples from Patients P1 and P2.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All sequences generated in this study are available in Genbank (MZ666121–MZ666124).