Abstract

Religious spaces have proven to be effective sites of health intervention amongst Black Americans. Less is known about how religious environments impact the health of subgroups of Black Americans, specifically Black men who have sex with men (MSM). Using data from the Promoting Our Worth, Equality, and Resilience (POWER) study, we explored the factor structure of a 10-item religious environment scale among Black MSM (N=2,482). Exploratory factor analysis revealed three distinct factors: 1) visibility of MSM, 2) structural support, and 3) structural homonegativity. The relationship between Black MSM and their religious environments is complex and should be investigated using measures that accurately reflect their lived experiences.

Introduction

Religion, Health, and Black Americans

Black Americans, in comparison to all other racial and ethnic groups in the US, are more likely to report having a formal religious affiliation (Pew, 2008), and similarly, Blacks in the US tend to have stronger ties to their religious affiliations than other racial groups (Watkins, et al, 2016a). This strong religious affiliation carries potential implications for population health, as the religious environment then becomes a part of daily life and community culture that can impact health. Religious involvement has been heavily studied as a predictor of health outcomes among Black Americans living in the US (Levin, et al, 2005). For example, social connections formed within religious communities are associated with improved mental health outcomes and religious behaviors like prayer are important coping mechanisms amongst Black Americans (Ellison & Taylor, 1996; van Olphen, et al, 2003). Meaning-based coping strategies are strengthened within religious environments and communities, and religious practices provide a space for Black Americans to emotionally cope with hardships and engage in religious coping behaviors like prayer (Hayward & Krause, 2015). Additionally, faith-based promotion interventions have been proven to significantly impact chronic disease indicators among Black Americans, further strengthening the evidence that religious spaces impact the health of Black Americans (DeHaven, et al, 2004; Lancaster, et al, 2014; Newlin, et al, 2011). Despite varying degrees of religious involvement, numerous studies suggest that religious involvement is protective for Black Americans’ health in a myriad of ways. When considering the unique experiences of subgroups such as Black men who have sex with men (MSM), however, the picture becomes more complicated as the effects of religious involvement on health are complex because of both positive (affirming) and negative (condemning) experiences within the religious environment (Lassiter, 2012).

Religion and the Health of Black MSM

Less information is known about the role of the religious environment in supporting or harming the health of certain subgroups of the Black population. The relationships between religion and the health and wellness of Black individuals become increasingly more complex when the viewed through the lens of sexuality. Because of tensions arising from cultural unacceptance of homosexuality within many religious communities (Lewis, 2003), Black individuals identifying as gay or experiencing same-sex attraction may be uniquely more vulnerable to health harms influenced by religious communities. This becomes particularly important when considering that the centrality of church and religion has been found to be significant among young Black MSM (Quinn & Dickson-Gomez, 2016). Among Black MSM, religious involvement has been found to be a significant predictor of internalized homonegativity and subsequent sexual risk behaviors (Smallwood, et al, 2017). Counter to what prior literature has found about the healthful effects of religious involvement among Black Americans, among men who have sex with men (MSM), religiosity has been associated with high-risk sexual behavior, substance use, HIV risk and depression among men who have sex with men (MSM) (Lassiter & Parsons, 2016; Watkins, et al, 2016a, 2016b). Though Black MSM experience health inequities beyond HIV, it remains a powerful exemplar; in 2018, young Black MSM accounted for nearly 26% of all new HIV infections and 36% of all new HIV diagnoses among MSM in the US (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2020). Conversely, the findings of a systematic review conducted in 2015 suggests that both religion and spirituality may have a more positive impact on the health of MSM of color than on white MSM (Lassiter & Parsons, 2016). These contradictory findings illustrate how intersections of identity must be considered in order to fully understand these complex associations. Being members of their racial group means that, despite negative outcomes associated with their sexual identity, Black MSM may still benefit from the protective factors associated with religious involvement, specifically protective factors against the acquisition of HIV (Garofalo, et al, 2015). However, intersectional perspectives highlight that research on Black MSM is more than simply adding together research within Black populations and research within MSM communities; rather, this population requires its own critical lens. The complexity of this relationship in this unique population warrants further inquiry into the mechanisms by which religion impacts health. Given that qualitative inquiry has determined that religious institutions’ positions regarding same-sex relationships is inconsistent with the lived experiences and needs of Black MSM that are part of their congregations (Miller, 2007), more quantitative inquiry into how the religious environment may be supporting or harming the health of Black MSM is warranted. This process of quantitative inquiry begins by understanding how measures of religious environment are functioning within samples of Black MSM.

Measures of Religion in Black MSM

Prior measures of the religious environment related to health in Black MSM are scarce. Studies examining religion and its associations with health among Black MSM typically use measures and scales that have not been validated within this population. These measures typically assess affiliation or engagement in religious activities, but tell us less about the religious environment (Carrico, et al, 2017; Watkins, et al, 2016a). Rather than providing information about how the individual actually responds to their religious environment, measures of affiliation or engagement describe how integrated the individual is within their religious context. While valuable information can be gleaned from these measures, they fail to demonstrate the extent to which the individual feels supported within their religious environment. In order to properly understand the influence of religion and the religious environment in Black MSM, it is important to use measures that accurately assess these constructs within this unique population. Failure to do so renders findings unstable within the population and limits external validity of results, indicating that there is space for further scientific inquiry about metrics of the religious environment. In order to build effective health interventions and strategies to address the needs of this population, accurate assessment of the environment must first illuminate the spaces in which these individuals live and thrive. To that end, the purpose of this study is to examine the psychometric properties of a religiosity measure used with a large sample of Black MSM in the US.

Methods

Study design and population

Data come from Promoting Our Worth, Equality, and Resilience (POWER), a serial cross-sectional, community-engaged study of Black MSM and Black transgender women. From 2014 – 2017, POWER recruited individuals attending Black Pride events in Atlanta, GA; Detroit, MI; Houston, TX; Memphis, TN; Philadelphia, PA; and Washington, DC. Individuals were eligible to participate if they: (1) were assigned male sex at birth; (2) reported having a male sexual partner in their lifetime; and (3) were 18 years of age or older.

For each city, POWER identified official Black Pride events and randomly selected recruitment sites from these events. Interested participants were guided to a nearby survey area where they were screened via electronic tablet for eligibility. In total, 13,396 individuals were approached; 44.89% of those approached (n = 6,015) agreed to screening, and 97.39% of screened participants completed a questionnaire (n = 5,858). This study of religious experiences only includes those who both identified as male and as either Black or African American.

Eligible participants completed self-administered, computer-assisted questionnaires using electronic tablets. Questionnaires took approximately 20 minutes to complete and were collected anonymously. A unique identifier code was created from a series of questions to identify participants who completed more than one survey; this process has been validated as 96% successful (Matthews, et al, 2019; Turner, et al, 2003). We identified 301 participants who completed more than one questionnaire across multiple years; only the first completed questionnaire was included in the current study. Additional information about the complete POWER study protocol is available elsewhere (Matthews, et al, 2019).

Measures

Sexual orientation identity.

One item was used to assess sexual orientation: “Which of the following do you identify as?” with the following four response options: (1) “gay/same gender loving;” (2) “heterosexual or ‘straight;’” (3) “bisexual;” and (4) “other.”

Depression.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression 10 (CES-D 10; Cronbach’s α=0.76) assessed depressive symptoms, and the scale dichotomized so that individuals were considered to have sufficient symptomatology consistent with major or clinical depression if they had scores of 10 or greater (Zhang, et al, 2012).

Internalized homophobia.

The extent to which participants reported negative self-views of their sexual orientation was assessed with the nine-item Internalized Homophobia Scale (Cronbach’s α=0.92; e.g., “I wished I werenť attracted to men.”) (Herek, et al, 1998). and recoded so that it ranged from 0 to 3, with higher values indicating greater internalized homophobia.

Demographics.

Age, education, city, and year of data collection were also assessed. Age was measured in years. Education was recoded to reflect the following categories: < high school or GED; high school / GED; some college or technical school; college graduate.

Church membership was assessed with a single-item dichotomous question, “Do you belong to a church?”

Religiosity was assessed with a single-item question, “How religious are you?” and recoded so that it ranged from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very), with higher values indicating greater religiosity.

Religious experiences of church-affiliated Black MSM were assessed using a scale developed by members of the POWER research team based on prior unpublished formative research conducted by one of the original co-investigators of the POWER study. The ten items assessed varying elements of MSM experiences with religion, such as being in the closet at church, the invisibility of MSM at church, the support of other MSM at church, reliance on church community, tolerance but not acceptance of MSM at church, affirmation of identity from church, belief in anti-gay therapy, the importance of church in one’s life, condemnation of MSM from a priest or pastor, and the allowance of same-sex marriages at church. Table 3 includes a full list of each item domain.

Table 3.

Table of final factor loadings for 3-factor solution.

| Item number | Item domain | Factor loading | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visibility of MSM | Structural support | Structural homonegativity | ||

| 1 | Forced in the closet at church | 0.892 | ||

| 2 | Nobody talks about MSM at church | 0.440 | ||

| 3 | Other MSM at church | 0.613 | ||

| 4 | Church provides support | 0.549 | ||

| 6 | Church affirms MSM | 0.817 | ||

| 10 | Church allows same-sex marriage | 0.745 | ||

| 5 | Church tolerates but does not support MSM | 0.612 | ||

| 7 | Church believes in conversion | 0.710 | ||

| 9 | Condemnation of MSM | 0.512 | ||

Data Analysis

Bivariate analysis compared participants by whether or not they reported belonging to a church. Only those participants who reported church membership, and therefore completed the 10-item religiosity scale, are represented in the subsequent factor analysis.

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the 10-item religious involvement scale using maximum likelihood estimation. Items were considered to have loaded on to a given factor if the factor loading was above 0.4, as guided by Hair, et al (1998). Factor structure was analyzed using an oblique rotation in MPlus 7.4 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2012). The initial process was guided by a theoretical hypothesis that a two-factor solution would best fit the data: church elements supportive MSM and church elements antagonistic of MSM. The next steps in the iterative process require knowledge of which eigenvalues were greater than 1, and as such are described in more detail in Results.

Results

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1 (n = 4,840). Approximately half (51.28%) of the sample reported belonging to a church. Though age, education, and sexual orientation identity did not significantly differ by church membership, several other differences were observed. Compared to those who did not report belonging to a church, those who did reported higher levels of internalized homophobia and religiosity, though they were less likely to report depressive symptomatology. The remaining analyses only use data from the 2,482 Black MSM participants who reported church membership.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Black MSM in POWER by church membership (n = 4,840)

| Does not belong to a church (n = 2,358) | Belongs to a church (n = 2,482) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SE) | 30.76 (0.20) | 31.14 (0.20) | 0.19 |

| Education, No. (%) | 0.31 | ||

| <High school/GED | 166 (7.06) | 179 (7.24) | |

| High school/GED | 511 (21.74) | 499 (20.18) | |

| Some college or technical school | 859 (36.54) | 880 (35.58) | |

| College graduate | 815 (34.67) | 915 (37.00) | |

| Sexual orientation identity, No. (%) | 0.12 | ||

| Bisexual | 395 (16.75) | 468 (18.86) | |

| Heterosexual | 33 (1.40) | 29 (1.17) | |

| Other | 29 (1.23) | 41 (1.65) | |

| Gay or same-gender loving | 1901 (80.62) | 1944 (78.32) | |

| Depressive symptomatology, No. (%) | 525 (22.35) | 447 (18.13) | <.01 |

| Internalized homophobia,a mean (SE) | 1.31 (0.02) | 1.49 (0.02) | <.01 |

| Religiosity,b mean (SE) | 1.40 (0.02) | 2.41 (0.02) | <.01 |

| City of data collection, No. (%) | <.01 | ||

| Atlanta | 705 (29.90) | 711 (28.65) | |

| Detroit | 299 (12.68) | 284 (11.44) | |

| Houston | 423 (17.94) | 643 (25.91) | |

| Memphis | 22 (0.93) | 59 (2.38) | |

| Philadelphia | 378 (16.03) | 288 (11.60) | |

| Washington, DC | 531 (22.52) | 497 (20.02) | |

| Year of data collection, No. (%) | 0.42 | ||

| 2014 | 643 (27.27) | 726 (29.25) | |

| 2015 | 794 (33.57) | 830 (33.44) | |

| 2016 | 638 (27.06) | 633 (25.50) | |

| 2017 | 283 (12.00) | 293 (11.80) |

Range = 0 to 4, with higher values indicative of greater internalized homophobia

Range = 0 to 3, with higher values indicative of greater religiosity

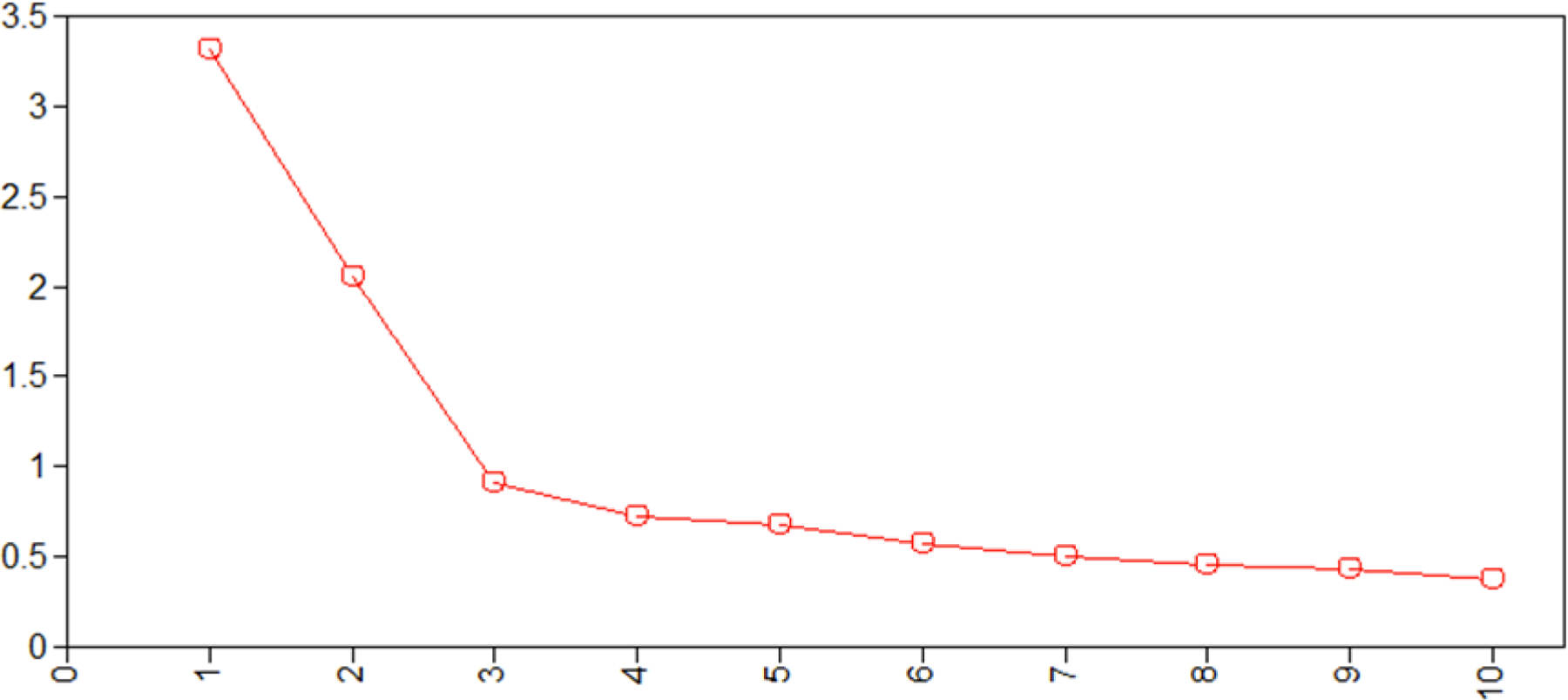

Despite an initial starting place of 2 factors, the eigenvalue criterion indicated that 3 factors may fit the data better, as shown in the scree plot presented in Figure 1. This led to the ultimate decision to test up to a 4-factor solution. The 4-factor solution included an item that loaded onto a single factor, raising concerns about the possibility of Q4 ‘Church provides support’ being a Heywood case (Kolenikov & Bollen, 2012). This led to the decision to revert to a 3-factor solution for the sake of model fit and parsimony, as the CFI and TLI for the 4-factor solution, both presented in Table 2, indicated model overfit.

Figure 1.

Scree plot of eigenvalues.

Table 2.

Comparison of fit statistics for 1, 2, 3, and 4 factor solutions.

| 1 Factor solution | 2 Factor solution | 3 Factor solution | 4 Factor solution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 (df) | 6793.46 (45) | 577.95 (26) | 247.96 (18) | 71.97 (11) |

| RMSEA (90% CI) | 0.187 (0.181, 0.192) | 0.093 (0.086, 0.099) | 0.072 (0.064, 0.080) | 0.047 (0.037, 0.058) |

| CFI | 0.555 | 0.918 | 0.966 | 0.991 |

| TLI | 0.428 | 0.858 | 0.915 | 0.963 |

One item, ‘the importance of belonging to a church’, did not load above the 0.4 cutoff guided by Hair et al (1998), and was not included in the final model. Upon closer examination, it appears that this item differs substantively from the rest of the items; it asks about the centrality of religion to the individual rather than asking about the religious environment itself. Table 3, presented below, presents the final 3-factor solution and the named factors: visibility of MSM at church, structural support at church, and structural homonegativity at church. Each of the three factors demonstrated sufficiently high internal consistency when assessing the resulting Cronbach’s Alphas: Visibility of MSM at church (α=0.66), structural support at church (α=0.77), structural homonegativity at church (α=0.71).

The fit statistics of the 3-factor solution are presented in contrast to the fit statistics of the four tested models in Table 2. Both the CFI (0.966) and TLI (0.915) in the 3-factor solution were sufficiently high (above 0.9) indicating good model fit as guided by Hu & Bentler (1999). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of the 3-factor solution was 0.072 (90% CI: 0.064, 0.080). Though higher than the widely-accepted cutoff value of 0.05, we view this RMSEA value as acceptable when considered in conjunction with model specification and other model fit indices as guided by Chen, et al (2008).

Discussion

Religion and experiences within religious environments are complex. For this reason, examining religion as a unidimensional construct is not sufficient and will not provide complete information on experiences in religious spaces. Specifically, the experiences of Black MSM are complicated in religious spaces that might not be affirming of their sexual identity, but carry cultural significance and importance for their other identities (e.g., race, gender). In order to capture this complexity, multidimensional measures are needed to examine how Black MSM navigate the idiosyncrasies of religious spaces.

Current measures of experiences in religious environments are not appropriate to use within this population, as they may not sufficiently capture the nuances of the lived experiences of Black MSM. A 2016 systematic review of religion and HIV among MSM revealed a lack of standardized, widely-used measures of religion among Black MSM. The most commonly cited measures were the COPE-religious coping scale and Duke religion index (Lassiter & Parsons, 2016). Neither one of these scales was designed to assess complexities like those within the relationship between Black MSM and religious spaces. These measures are inappropriate for use in this population because they fail to take the individual’s social identities – in this case, sexual identity – into account when determining the supportiveness of a religious environment. In a sense, these measures flatten the experiences of Black MSM. Current measures assume that all groups have similar relationships with religious structures, and this assumption undermines the great diversity and complexity of individuals’ relationships with religious spaces.

The results of this exploratory analysis showed a multidimensional structure undergirding these measures. We named these resulting factors emerged as visibility of MSM at church, the structural support of MSM within the church, and structural homonegativity of the church environment. The visibility of MSM at church focuses on the visible existence of MSM in the religious space; items within this factor refer to the conspicuousness of MSM within the religious environment. The structural support factor inquires how the religious environment supports MSM in the congregation, with a specific emphasis on support factors that are unique to Black MSM. We hypothesized a two-factor solution, but our analysis suggests visibility in and of itself cannot be thought of the same as support. The structural homonegativity factor examines how the religious environment structurally upholds tenets of homonegativity and heterosexism that directly impact Black MSM within the congregation. It is important to note with this factor that homonegativity comprises not just abject condemnation of homosexuality, such as a “fire and brimstone” messaging commonly attributed to Black American faith traditions; it also includes the concept of the “open closet,” or passive acceptance of homosexuality until it is made public and overt, at which point rebuke is invoked (Fullilove & Fullilove, 1999).

Researchers need more accurate information about Black MSM’s relationships with religious environments in order to build more culturally-appropriate health interventions in this population. The measures that are being used to build these interventions fail to account for intersecting social identities and the tensions that may arise in religious communities. Further, this work can help shift the focus of interventions away from working with individuals to cope with their church experiences, to partnering with churches to identify and address what environmental characteristics might be intervened upon to ensure all congregants can experience the full benefit of church membership, and in turn improve outcomes in this population.

Strengths and Limitations

This research is among the first to acknowledge how the complexity of the relationships between Black MSM and religious spaces can impact health. Prior work has established that this is a unique population because of its complex ties to religion, but has not yet gone on to understand how measures can better reflect that complexity. In particular, this study carries the strength of doing within group analyses, and provides the basis to establish measures of religious experience that efficaciously represent this unique population.

No research is without limitations. Here, missing data means that we may not have full or accurate information for all individuals within the sample. However, as this is among the first work to validate these types of measures in a large sample of this unique population, this work captures more of the totality of Black MSM’s experiences in religious spaces. Additionally, this research only assessed individuals who reported having a religious affiliation; therefore, it does not include individuals who may attend or be involved in religious settings but do not consider themselves affiliated. There are individuals who may have experiences in religious settings that are important for our understanding of how these environments work to promote or hinder healthful behaviors among MSM. However, those experiences may not be represented within this work because it only assessed individuals who reported a membership with a church, and as a result, limits our understanding of mechanisms by which church, or other religious organizations, promote wellbeing for Black MSM. For example, despite reporting higher levels of internalized homophobia, church-belonging Black MSM were less likely to report depressive symptomatology. Additionally, there were several limitations within the data regarding the measures of religiosity. First, the item that assessed church membership failed to assess the multiple dimensions of membership. Different individuals can interpret ‘church membership’ and its various aspects of participation differently. Similarly, the single item measure of religiosity did not assess the various ways individuals can interpret what it means to be religious, whether that be through occasional attendance at religious services or more personal involvement within religious communities. The survey items did not ask about the composition of the churches that participants attend. This is a limitation because there are structural factors within each individual’s church which may be impacting their experiences as well. Finally, some individuals may have been involved in religious settings during formative periods of development; we cannot currently determine if those with no current church affiliation never had one, or severed ties later in life. The presence of regional differences also highlights a need to especially engage with religion in the Southern context, where those cultural and policy determinants that have been shown to be harmful to Black and LGBT people already exist to a greater degree (Barth, 2019).

Conclusion

There is great complexity in the relationship that individuals have with religious environments. As such, measures that go beyond unidimensional understandings of constructs like religion and the religious environment are needed to accurately assess the interplay between health and social environments. Future research should focus on validating these measures in other populations that may have complex relationships with religion and religious spaces.

Acknowledgments

We express our appreciation to the thousands of participants who donated their time in our research, and to the Center for Black Equity for welcoming our research team into the community of Black Prides across the country. We extend a special thanks to the dozens of service organizations who provided HIV testing services for our study participants.

Funding:

This research was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (grant R01NR013865), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant R21AI120777), and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant T32MH094174).

Autobiographical note:

Tiffany Eden, MPH, is a PhD candidate in the department of Health Behavior at the Gillings School of Global Public Health. She focuses her research on intersectionality and adolescent mental health as it relates to risk behaviors among youth.

Footnotes

Declarations

Author Disclosure: No competing financial interests exist.

Availability of data: More information regarding the data analyzed in this manuscript can be found in Matthews, et al, 2019.

Code availability: Not applicable.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The original study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s IRB, and secondary analysis of the data for this manuscript was deemed exempt by The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill IRB. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Barth J (2019). The American South and LGBT Politics. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics

- 2.Carrico AW, Storholm ED, Flentje A, Arnold EA, Pollack LM, Neilands TB, Rebchook GM, Peterson JL, Eke A, Johnson W, & Kegeles SM (2017). Spirituality/religiosity, substance use, and HIV testing among young black men who have sex with men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 174(1): 106–112. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). HIV and African American gay and bisexual men Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/msm/cdc-hiv-bmsm.pdf

- 4.Chen F, Curran PJ, Bollen KA, Kirby J, & Paxton P (2008). An Empirical Evaluation of the Use of Fixed Cutoff Points in RMSEA Test Statistic in Structural Equation Models. Sociological Methods & Research, 36(4), 462–494. 10.1177/0049124108314720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, & Berry J (2004). Health programs in faith-based organizations: Are they effective? American Journal of Public Health, 94(6): 1030–1036. 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellison CG & Taylor RJ (1996). Turning to prayer: Social and situational antecedents of religious coping among African Americans. Review of Religious Research, 38(2): 111–131. 10.2307/3512336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fullilove MT, & Fullilove RE III (1999). Stigma as an obstacle to AIDS action: The case of the African American community. American Behavioral Scientist, 42(7), 1117–1129. 10.1177/00027649921954796 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garofalo R, Kuhns LM, Hidalgo M, Gayles T, Kwon S, Muldoon AL, & Mustanski B (2015). Impact of religiosity on the sexual risk behaviors of young men who have sex with men. Journal of Sex Research, 52(5): 590–598. 10.1080/00224499.2014.910290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hair JF, Tatham RL, Anderson RE, & Black W (1998). Multivariate data analysis (Fifth Ed.) Prentice-Hall: London. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayward RD, & Krause N (2015). Religion and strategies for coping with racial discrimination among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. International Journal of Stress Management, 22(1), 70–91. 10.1037/a0038637 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herek GM, Cogan JC, Gillis JR, Glunt EK (1998). Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Medical Association, 2(1):17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu L-I, Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolenikov S, & Bollen KA (2012). Testing negative error variances: Is a Heywood case a symptom of misspecification? Sociological Methods & Research, 41(1), 124–167. 10.1177/0049124112442138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lancaster KJ, Carter-Edwards L, Grilo S, Shen C, & Schoenthaler AM (2014). Obesity interventions in African-American faith-based organizations: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews, rel15(Suppl. 4): 159–176. 10.1111/obr.12207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lassiter JM (2014) Extracting dirt from water: A strengths-based approach to religion for African American same-gender-loving Men. Journal of Religion and Health 53, 178–189. 10.1007/s10943-012-9668-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lassiter JM, & Parsons JT (2016). Religion and spirituality’s influences on HIV syndemics among MSM: A systematic review and conceptual model. AIDS and Behavior, 20: 461–472. 10.1007/s10461-015-1173-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin J, Chatters LM, & Taylor RJ (2005). Religion, health and medicine in African Americans: Implications for physicians. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(2): 237–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis GB (2003). Black-white differences in attitudes toward homosexuality and gay rights. Public Opinion Quarterly, 67: 59–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3521666 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews DD, Sang JM, Chandler CJ, Bukowski LA, Friedman MR, Eaton LA, & Stall RD (2019). Black Men Who Have Sex with Men and Lifetime HIV Testing: Characterizing the Reasons and Consequences of Having Never Tested for HIV. Prevention Science, 20(7), 1098–1102. 10.1007/s11121-019-01022-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller RL Jr. (2007). Legacy Denied: African American Gay Men, AIDS, and the Black Church. Social Work, 52(1), 51–61. 10.1093/sw/52.1.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthén LK and Muthén BO (1998–2012). Mplus User’s Guide Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newlin K, Dyess SM, Allard E, Chase S, & Melkus GD (2011). A methodological review of faith-based health promotion literature: Advancing the science to expand delivery of diabetes education to Black Americans. Journal of Religion and Health, 51: 1075–1097. 10.1007/s10943-011-9481-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pew Research Center (2008). US religious landscape: Religious affiliation Retrieved from https://www.pewforum.org/2008/02/01/u-s-religious-landscape-survey-religious-affiliation/.

- 24.Quinn K, & Dickson-Gomez J (2016). Homonegativity, religiosity, and the intersecting identities of young Black men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 20(1): 51–64. 10.1007/s10461-015-1200-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smallwood SW, Spencer SM, Ingram LA, Thrasher JF, & Thompson-Robinson MV (2017). Examining the relationships between religiosity, spirituality, internalized homonegativity, and condom use among African American men who have sex with men in the Deep South. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(2): 196–207. 10.1177/1557988315590835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner KR, McFarland W, Kellogg TA, Wong E, Page-Shafer K, Louie B, Dilley J, Kent CK, & Klausner J (2003). Incidence and prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in persons seeking repeat HIV counseling and testing. Sexually Transmitted Disease, 30(4):331–334. 10.1097/00007435-200304000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Olphen J, Schulz A, Israel B, Chatters L, Klem L, Parker E, & Williams D (2003). Religious involvement, social support, and health among African American women on the east side of Detroit. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 18(7): 549–557. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21031.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watkins TL Jr., Simpson C, Cofield SS, Davies S, Kohler C, & Usdan S (2016a). The relationship between HIV risk, high-risk behavior, religiosity, and spirituality among Black men who have sex with men (MSM): An exploratory study. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(2): 535–548. 10.1007/s10943-015-0142-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watkins TL Jr., Simpson C, Cofield SS, Davies S, Kohler C, & Usdan S (2016b). The relationship of religiosity, spirituality, substance abuse, and depression among Black men who have sex with men (MSM). Journal of Religion and Health, 55(1): 255–268. 10.1007/s10943-015-0101-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang W, O’Brien N, Forrest JI, Salters KA, Patterson TL, Montaner JSG, Hogg RS, & Lima VD (2012) Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One, 7(7): e40793. 10.1371/journal.pone.0040793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]