Abstract

We present the case of a 59-year-old man who sustained an esophageal perforation as a result of sword swallowing. An esophagogram established the diagnosis, and surgical repair was attempted. However, 19 days later, a persistent leak and deterioration of the patient's condition necessitated a transhiatal esophagectomy with a left cervical esophagogastrostomy. The patient recovered and has resumed his daily activities at the circus, with the exception of sword swallowing.

This case report presents an unusual mechanism for a potentially lethal injury. Our search of the English-language medical literature revealed no other report of esophageal perforation resulting from sword swallowing. Management of such an injury is often difficult, and a favorable outcome is dependent on prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Key words: Esophageal perforation/etiology/diagnosis/radiography/surgery, esophagectomy/methods, esophagus/injuries/surgery

Esophageal perforation is an injury with high morbidity and mortality rates. Rupture or perforation of the esophagus is most often due to iatrogenic instrumentation, foreign bodies, spontaneous rupture (Boerhaave syndrome), or external trauma. We present a case of esophageal perforation with an unusual mechanism of injury: sword swallowing.

Case Report

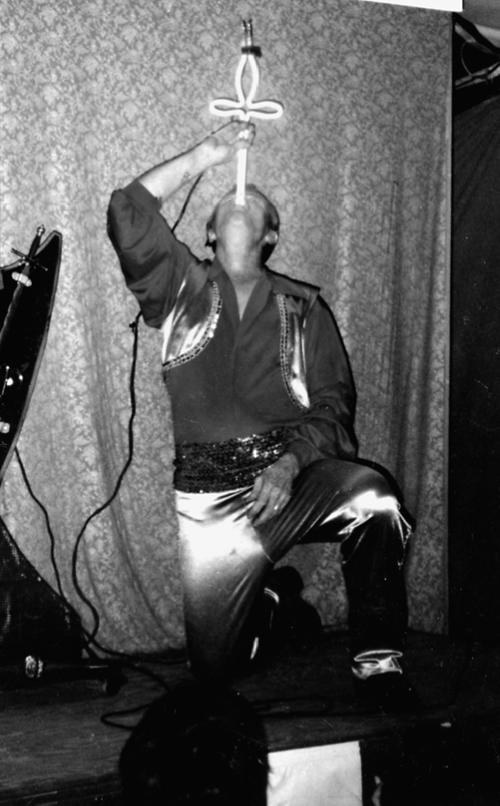

A 59-year-old man presented with a 5-day history of substernal chest pain and discomfort. He stated that he was part of a circus act and was practicing sword swallowing just before the onset of symptoms (Fig. 1). In addition to pain, he had experienced severe dysphagia, which was severely limiting his oral intake. He also reported a 2-day history of low-grade fever and chills. He had no chronic medical disorders. His past surgical history included a laparotomy in 1995 to remove glass fragments from his stomach after he had swallowed a light bulb as part of his circus act. He also reported a history of multiple extremity fractures requiring orthopedic repair, including a fracture of his right humerus that he had sustained after being mauled by a circus elephant.

Fig. 1 Photo of the patient swallowing a neon-lighted sword as part of his circus act.

The patient's initial vital signs were recorded: he had a temperature of 100.6 °F and a pulse rate of 88 beats/min. Physical examination revealed a thin man in moderate distress with mild shortness of breath. No abnormalities were noted on examination of the oropharynx. A neck exam revealed bilateral posterior and lateral tenderness. No crepitus was palpated. On pulmonary auscultation, sparse rales were heard over the right hemithorax. Cardiac auscultation revealed a regular rate and rhythm without murmurs, rubs, gallops, or crunches. An abdominal exam showed mild mid-epigastric tenderness without rebound or guarding. Rectal examination revealed no abnormalities, and there was no evidence of occult blood in the stool.

Initial chest radiography showed no mediastinal emphysema, no pleural effusion, and no evidence of pneumothorax. The patient was the sent for a Gastrografin® (Schering AG; Berlin, Germany) esophagogram, which showed an esophageal perforation in the upper thoracic esophagus with collection of dye in the prevertebral space. No communication with the pleural cavities was noted (Fig. 2). The patient had a white blood cell count of 13,400/mm3 with 69% neutrophils and 9% bands.

Fig. 2 Esophagogram showing esophageal perforation in the upper thoracic esophagus with leakage of Gastrografin dye.

A surgical consultation was obtained and the patient was taken to the operating room for surgical repair. A posterolateral thoracotomy was used to approach the esophagus through the right 4th intercostal space. An obvious area of inflammation around the esophagus, found near the apex of the right thorax, was explored and cultures were taken. The perforation was identified 4 cm below the apex of the right thorax. The defect was approximately 2 cm in length. The edges of the perforation were carefully débrided and the entire field was well irrigated. The defect was then closed with a fine interrupted absorbable monofilament suture. A parietal pleural flap was then dissected and used to buttress the repair. A Silastic mediastinal drain tube and a 32-F chest tube were placed through separate right intercostal incisions. A small, upper midline laparotomy incision was made, and a feeding jejunostomy tube was placed.

Postoperatively, the patient remained in stable condition with no immediate adverse effects. He had minimal mediastinal and chest tube drainage, and he was afebrile by the 9th postoperative day. An esophagogram at that time did, however, reveal a small leak at the repair site. Chest and mediastinal drainage, enteral nutritional support via the jejunostomy tube, and intravenous antibiotic therapy were continued. On postoperative day 19, an esophagogram indicated that the leakage continued. The patient began experiencing low-grade fevers, as well as nausea, chest pain, and dyspnea. An elevation to 15,800/mm3 in his white blood cell count was noted. Because of the persistent leak, the patient's clinical deterioration, and impending sepsis, the decision was made to proceed with an esophagectomy.

The patient was taken to the operating room and underwent a transhiatal esophagectomy with a left cervical esophagogastrostomy. Postoperatively, he recovered without complication. On postoperative day 8, a Gastrografin esophagogram showed a patent esophagogastrostomy with no leak. The patient was started on a clear liquid diet. His drainage tubes were removed the next day, and his diet was advanced to solid foods. He was discharged from the hospital in good condition on the 11th day after the esophagectomy. When seen 2 months postoperatively, the patient was doing well and had resumed his normal daily activities at the circus, but he had stopped swallowing swords.

Discussion

A search of the English-language medical literature revealed no other reports of an esophageal perforation resulting from sword swallowing. There is very little information on the subject of sword swallowing itself. Two articles in otolaryngology journals discussed the biomechanics of sword swallowing and the use of sword swallowers to assist in the 1st esophagos-copies. 1,2 Adolph Kussmaul performed the 1st esophagoscopy on a professional sword swallower in 1868. 1 He was able to inspect the esophagus and the fundus of the stomach with a rigid 47-cm tube. Kussmaul enlisted sword swallowers because of their ability to form a straight line from the pharynx to the stomach and to voluntarily relax the cricopharyngeal muscle, allowing passage of an endoscope.

Information concerning esophageal perforations and its management is plentiful. Dr. Hermann Boerhaave was the 1st to report a case of esophageal perforation in 1724 3 when he described the postemetic rupture and subsequent rapid death of Dutch grand admiral Baron Jan van Wessenaer. Boerhaave said of esophageal perforation: “When it [occurs] it can be recognized but it cannot be remedied by the medical profession.” This statement bore some truth: it was not until 1947 that Barrett 4 performed the 1st successful repair of a perforated esophagus.

A diagnosis of esophageal perforation is usually suggested by the patient's history. Symptoms include pain, fever, chills, dysphagia, and hematemesis; and signs include chest or cervical tenderness, mediastinal crunch heard on cardiac auscultation (Hamman sign), and crepitation. A chest radiograph often shows mediastinal emphysema, pneumopericardium, pneumothorax, or pleural effusion. The diagnosis is confirmed in almost all cases by contrast esophagograms, which can delineate both the level of perforation and the communication of the injury into the pleural spaces. Less often, computed tomography and direct examination by esophagoscopy are needed in order to establish the diagnosis.

Many different surgical approaches are available for esophageal perforation, including primary repair with drainage; exclusion and diversion; and resection. The method of primary repair and drainage is generally chosen for those patients who present early, without evidence of a severe inflammatory reaction and without other esophageal disease. 5 If the diagnosis is delayed and there is some evidence of inflammation, many surgeons advocate a buttressed repair. Depending on the site of injury, the options for reinforcement include the use of pleural flaps, pedicled intercostal muscle flaps, pericardial flaps, diaphragmatic flaps, omental flaps, or gastric wall patches. 6 Exclusion and diversion is a technique that involves primary closure of the defect, formation of an end or loop cervical esophagostomy, ligation or division of the distal esophagus, and formation of a gastrostomy. This technique isolates the injured tissue from contamination of the oral cavity above and the corrosive gastric contents below. Urschel 7 has reported good results using this technique, especially in patients with delayed presentation. The major disadvantage of this technique is the need for a 2nd major operation to restore gastrointestinal continuity. Esophageal resection with reconstruction is most often chosen for patients who have evidence of severe esophageal necrosis, a malignant process, or for patients such as ours, who have undergone a failed attempt at primary repair. 8,9 Esophagectomy can be performed through a transhiatal or thoracic approach and usually involves gastric reconstruction with a cervical esophagogastrostomy. This aggressive approach removes the diseased tissue and allows healing of the anastomosis between 2 surfaces that are not inflamed.

Nonsurgical therapy has been advocated by some, most notably by Cameron and colleagues, 10 for patients with a leak that is confined to the mediastinum, that is self draining into the esophagus, and that causes the patient minimal symptoms without signs of sepsis. Nonsurgical therapy consists of the halting of oral intake, administration of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, nasogastric decompression, and parenteral hyperalimentation. If the patient's condition deteriorates or fails to improve, surgery is indicated. The goal of all management approaches is to prevent further mediastinal contamination, to achieve drainage of all affected compartments, to provide nutritional support, and to restore the gastrointestinal tract.

The prognosis of patients with esophageal perforation depends on many factors. Data gathered by Jones and Ginsberg 8 in a series between 1980 and 1990 indicated an overall mortality rate of 22%. 8 Patients with cervical injuries were found to have a mortality rate of 6%; the mortality rate with thoracic perforation was 34% and with abdominal perforation, 29%. The lower mortality rate in patients with cervical perforation was due to the prevention of spread of infection by the anatomic planes in the neck. In a study by Attar and associates, 11 delay in diagnosis had a major impact on patients' prognosis. Those patients presenting in less than 24 hours had a mortality rate of 13%; however, those who presented more than 24 hours after injury had a mortality rate of 45%. As expected, the rate is higher when underlying esophageal disease is present, such as carcinoma.

This case report presents an unusual mechanism for a potentially lethal injury. Management of esophageal perforation is often difficult, and a favorable outcome is dependent upon prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Patrick R. Wells, MD, General Surgery Resident, Christus St. Joseph Hospital, 1919 LaBranch, Houston, TX 77002

References

- 1.Huizinga E. On esophagoscopy and sword-swallowing. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1969;78:323–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Devgan BK, Gross CW, McCloy RM, Smith C. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of sword swallowing. Ear Nose Throat J 1978;57:445–50. [PubMed]

- 3.Boerhaave H. Atrocis, nec descripti prius, morbi historia. Secundum medicae aris leges conscript. Derbes V, Mitchell R, English translation. Bull Med Libr Assoc 1955;43:217–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Barrett NR. Report of a case of spontaneous perforation of the oesophagus successfully treated by operation. Br J Surg 1947–8;35:216–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Whyte RI, Iannettoni MD, Orringer MB. Intrathoracic esophageal perforation. The merit of primary repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;109:140–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Fell SC. Esophageal perforation. In: Pearson EG, Deslau-riers J, Ginsberg RJ, Hiebert CA, McKneally MF, Urschel HC Jr, editors. Esophageal surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. p. 495–515.

- 7.Urschel HC Jr. Perforation of the esophagus. In: Nyhus LM, Baker RJ, editors. Mastery of surgery. 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown; 1992. p. 602–8.

- 8.Jones WG 2d, Ginsberg RJ. Esophageal perforation: a continuing challenge. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;53:534–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Altorjay A, Kiss J, Voros A, Aziranyi E. The role of esoph-agectomy in the management of esophageal perforations. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;65:1433–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Cameron JL, Kieffer RF, Hendrix TR, Mehigan DG, Baker RR. Selective nonoperative management of contained intrathoracic esophageal disruptions. Ann Thorac Surg 1979; 27:404–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Attar S, Hankins JR, Suter CM, Coughlin TR, Dequeira A, McLaughlin JS. Esophageal perforation: a therapeutic challenge. Ann Thorac Surg 1990;50:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed]