Abstract

Human inborn errors of immunity (IEI) affecting the type I interferon (IFN-I) induction pathway have been associated with predisposition to severe viral infections. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening systemic hyperinflammatory syndrome that has been increasingly associated with inborn errors of IFN-I-mediated innate immunity. Here is reported a novel case of complete deficiency of STAT2 in a 3-year-old child that presented with typical features of HLH after mumps, measles, and rubella vaccination at the age of 12 months. Due to the life-threatening risk of viral infection, she received SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Unfortunately, she developed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) after SARS-CoV-2 infection, 4 months after the last dose. Functional studies showed an impaired IFN-I-induced response and a defective IFNα expression at later stages of STAT2 pathway induction. These results suggest a possible more complex mechanism for hyperinflammatory reactions in this type of patients involving a possible defect in the IFN-I production. Understanding the cellular and molecular links between IFN-I-induced signaling and hyperinflammatory syndromes can be critical for the diagnosis and tailored management of these patients with predisposition to severe viral infection.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10875-023-01488-6.

Keywords: STAT2 deficiency, Innate immunity, Viral susceptibility, Interferons, IFNα, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

Type I interferons (IFN-I), specially IFNα and IFNβ, are cytokines that play a key role in host human immune defense towards microbial pathogens in general and viruses in particular [1]. When a viral particle is recognized by membrane-bound Toll-like receptors (TLRs) or in the cytoplasm by intracellular viral sensors, interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) mediate the expression of IFN-I. STAT2 is a signal transducer and transcription factor phosphorylated and activated upon IFN-I induction. STAT2, STAT1, and IRF9 form a heterotrimeric complex, the IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) inducing the transcription of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). Human inborn errors of innate immunity affecting the IFN-I pathway have been associated with severe predisposition to viral infections [2, 3, 4, 5, 6].

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening systemic hyperinflammatory syndrome that leads to pathologic immune activation increasing pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion [7, 8]. Primary HLH is caused by genetic defects of NK and T-cell cytotoxicity typically manifested in early childhood, but it has also increasingly been recognized in the context of inborn error of immunity (IEI) and secondary conditions other than cytotoxic defects, often triggered by infections [8]. STAT2 deficiency was first reported in 2013 as an autosomal recessive IEI in a family with susceptibility to severe viral illness [9] and twenty three patients with similar phenotype have been described to date [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Uncontrolled reaction to mumps, measles, and rubella (MMR) vaccine has resulted to be a common feature in these patients, three of them developed hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) features during the following days after routinely vaccination [11, 12, 13]. A failed downregulation of the pathway or delayed activation of IFNγ-mediated response has been proposed as a mechanism for unexplained dysregulated inflammatory response in STAT2 and IRF9 deficiencies [15] but the exact mechanism remains unclear. Although IFNγ has a pivotal role in both primary and secondary HLH, molecular defects in the IFN-I signaling pathway has also been related with HLH (IFNAR1, IFNAR2, and STAT1 deficiencies) [16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Furthermore, IFN-I exerts anti-inflammatory effects [21], so an impaired IFN-I activity has been associated with lack of induction of anti-inflammatory cytokines and inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines production, suggesting that IFN-I may be implicated in the generation of a hyperinflammatory process [22, 23, 24].

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is a very rare condition in the heterogeneous group of IEI [25]. It reflects a severe hyperinflammatory delayed-onset condition of SARS-CoV-2 infection characterized by multiorgan failure with prominent cardiac dysfunction [26, 27]. Furthermore, some features of hyperinflammation as well as the management with high dose steroids overlap with HLH [28].

We report a 3-year-old girl with complete STAT2 deficiency that suffered from viral susceptibility since the first year of life and presented HLH after measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination and MIS-C after SARS-CoV-2 infection (despite proper vaccination).

Methods

Cells and Cell Culture

Human peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained by gradient density separation from the blood of patient and healthy controls. EBV-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (BLCLs) were derived from patients and healthy controls as previously described [29] and maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, penicillin 100 U/mL, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. K562 cell lines were used as target cells for NK cell degranulation and maintained in supplemented RPMI media as described above.

For cell stimulation, PBMCs and BLCLs from the patient and control subjects were stimulated with IFNα (1000 U/mL) (human IFNa2b, Miltenyi Biotec, GmbH, Germany) and IFNγ (1000 U/mL) (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) at indicated times.

NK-Cell Degranulation Assay

PBMCs from patient and healthy control were incubated with K562 cells in NK:K562 ratios of 1:0 and 1:1 in presence of 200 U/mL of rIL-2 (Roche) during 4 h at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator in the presence of brefeldin after 1 h of NK:K562 incubation. Cells were then washed and stained with appropriate antibodies and NK-cell degranulation was evaluated as the percentage of CD56 + CD107a positive cells by flow cytometry.

Genomic DNA and cDNA Sequencing

Genomic DNA and RNA were extracted from EDTA blood samples using a MagNa Pure Compact Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Roche,) and ReliaPrep™ RNA Cell Miniprep System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), respectively. NGS was run in an Ion Torrent PGM platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using a targeted gene sequencing with an inhouse designed panel of 192 genes involved in IEI (Ampliseq, Thermo Fisher Scientific) (Table S1). Candidate STAT2 variant was confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing using the following specific primers: cctgtgctttgcttggtttc and gttgagcatctctccctttc. cDNA was synthetized from RNA with a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystem, Waltham, MA, USA). Splicing was tested with specific exonic primers (GAGCCAGTTCTCGAAACACC and TGCCTCAGGTGAAACAACAG) using RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Gene Expression Assays

Total RNA was isolated from PBMCs and BLCLs and reverse transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and gene expression was analyzed by qPCR using a TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix and specific TaqMan probes (IRF7: Hs01014809_g1; IFIT1: Hs03027069_s1; ISG15: Hs01921425_s1; STAT2: Hs01013116_g1; IFNα2: Hs00265051_s1; GAPDH: Hs02786624_g1); USP18 (Hs07289021_m1) (ThermoFisher Scientific) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instruction. Relative quantifications using GADPH as endogenous control were evaluated with the comparative CT method (ΔΔCT).

Cell extracts for immunoblotting were prepared by incubating PBMCs or BLCLs in RIPA lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, San Luis, MO, USA) with Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (ThermoFisher Scientific) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instruction. Western blot was performed on 4–20% precast polyacrylamide gel and proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-rad, CA, USA). Antibodies used were STAT2 (Cell signaling, MA, USA) and β-actin (Merck Life Science, Darmstadt, Germany). Signal was detected in a Gel Doc XR + Imager (Bio-Rad).

STAT1 Phosphorylation Assay

For testing STAT1 phosphorylation, a total of 200,000 PBMCs or BLCLs were stimulated with IFNα or IFNγ (1000 U/mL) at indicated times at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were fixed with Lyse/Fix buffer and permeabilized with phosphoflow Perm Buffer III (both BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA). After washing, cells were stained with the appropriate antibodies: anti-CD3-FITC (clone UCHT1, Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA), anti-CD64-PE (clone 10.1, BD biosciences, NJ, USA), anti-STAT1 (pY701)-APC (clone 4a RUO, BD Biosciences), and anti-total STAT1 (N-Terminus)-APC (Clone 1, RUO, BD Biosciences) during 30 min at 4 °C. In PBMCs, STAT1 phosphorylation and total STAT1 were evaluated in CD45 + CD3-CD64 + monocytes. In BLCLs, median fluorescence intensity (MFI) was measured in total BLCL population. Cellular acquisition was performed using a Beckman Coulter Navios or DxFLEX cytometer and data were analyzed with Kaluza 2.1 software.

Cellular Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination

The cellular immune response was determined before the administration and after each dose of the vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech, Brooklyn, NY, USA). IFNγ T-cell immunity was measured in FluoroSpot plates (MabTech, Nacka Strand, Sweden) as previously described [30].

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad). Two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied. The results were considered significant when p-values were < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), and < 0.001 (***).

Results

Case Presentation and Molecular Diagnosis

The patient is a 3-year-old girl born to first-cousin consanguineous healthy parents. At the age of 2 months, she began to suffer from respiratory recurrent viral infections and recurrent wheezing. At the age of 10 months, she required hospitalization because an episode of bronchiolitis. When she was 12 months and 6 days after scheduled MMR vaccination, she developed febrile illness with seizures. She presented bilateral exudative tonsillitis, generalized erythematous rash, and hepatomegaly. Laboratory evaluation showed anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, lymphopenia, hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, hypofibrinogenemia, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, elevated soluble CD25 (sCD25), and IFNγ levels in plasma (Table 1). Immunophenotype revealed T and B-cell lymphopenia, increased effector memory, activated CD8 + phenotype, and normal NK-cell number and percentage (482 cells/µL, 29% of total lymphocytes, respectively) and perforin expression on CD8 T and NK cells (Table S2). The patient fulfilled 6/8 clinical and laboratory diagnostic criteria for HLH (fever, hepatomegaly, cytopenias, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia + hypofibrinogenemia, and hemophagocytosis in bone marrow) (Table 1) [31]. In view of HLH episode, she received methylprednisolone, cyclosporine A (CsA), anakinra, and two doses of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).

Table 1.

Laboratory features of patient at diagnosis of HLH and MIS-C

| Laboratory features | HLH (12 m) | MIS-C (3 y) | References values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 7.4 | 10.2 | 11–14 g/dL |

| Platelets | 106,000 | 67,000 | 200,000–450,000/μL |

| Leukocytes | 3900 | 22,700 | 5000–15,000/μL |

| Lymphocytes | 1648 | 300 | 3000–8000/μL |

| Hemophagocytosis in bone marrow | + | NA | - |

| Fibrinogen | 96 | 731 | 200–560 mg/dl |

| Ferritin | 5620 | 1172 | 20–200 ng/ml |

| Triglycerides | 722 | 373 | 50–200 mg/dl |

| sCD25 | 1763 | 462 | 69–503 U/mL (> 2400)* |

| IFNγ | 203 | 2511 | 0–3 pg/mL |

| NT-proBNP | NA | 1589 | < 125 pg/ml |

| D-Dimer | NA | 31,151 | 0–500 ng/mL |

Altered values are shown in bold. *Levels for considering HLH. Abbreviations: Hb, hemoglobin; sCD25, soluble CD25; NA, no analyzed; m, months; y, years

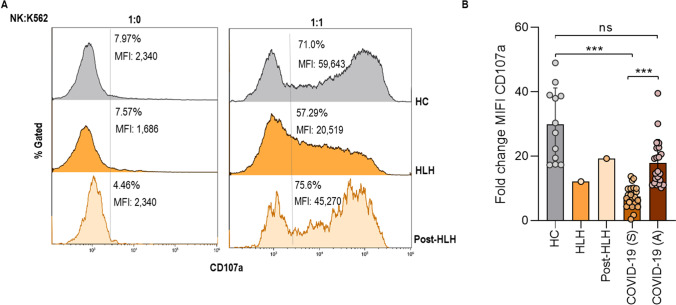

To complete the criteria for HLH, NK-cell function was evaluated by a degranulation assay against K562 cells (Fig. 1). Patient showed mild decreased both percentage and median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD107a expression on NK-cells (Fig. 1A). These results are in accordance with NK degranulation data in patients with severe acute Sars-CoV-2 infection, which has been associated with a worse prognosis of the disease [32]. NK degranulation returned to normal levels after treatment, when she was asymptomatic and infection-free, similar to healthy controls and asymptomatic COVID-19 patients (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

NK-cell activity. A STAT2 patient NK-cell degranulation represented with percentage and median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD107a expression in CD56 + NK-cells against K562 cells evaluated at diagnosis of HLH, in stable condition (post-HLH) and healthy control (HC). One experiment is represented B CD107a MFI fold change in healthy controls (HC, n = 12), STAT2 patient at HLH and post-HLH, severe COVID-19 (S, n = 26), and asymptomatic COVID-19 patients (A, n = 22)

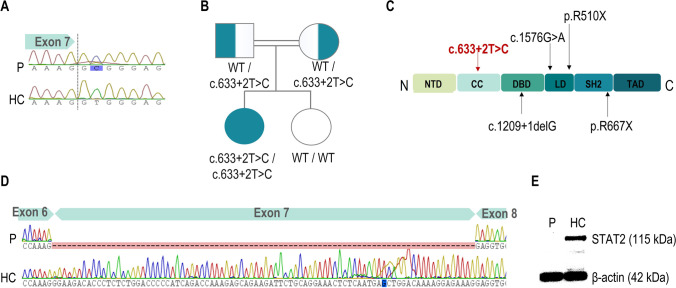

Given the familial history of consanguinity, an autosomal recessive IEI was suspected. Targeted NGS gene panel for 192 genes associated to IEI identified a previously unreported germline homozygous variant in the STAT2 gene (chr12:56748560A > G; c.633 + 2 T > C) that was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 2A). Family segregation study confirmed the heterozygosity in the parents while old sister did not carry the variant (Fig. 2A, B). This variant is described for the first time in the coiled-coil domain associated with HLH phenotype (Fig. 2C); it was not found in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) and was predicted to be damaging by in silico tools, since it introduces a premature stop codon (p.Gly183Glyfs*40). No additional mutations in genes associated with familial HLH and other IEI were identified. RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing from cDNA confirmed the expected altered splicing leading to exon 7 deletion (Fig. 2D). Protein expression in IFNα-stimulated PBMCs was assayed by Western blot showing the complete lack of STAT2 in the patient (Fig. 2E), without expression of any truncated protein.

Fig. 2.

Molecular diagnosis of the patient. A Sanger sequencing of exon 7 of STAT2 revealing the homozygous c.633 + 2 T > C variant; B family pedigree. Consanguineous parents were asymptomatic heterozygous carriers and the old sister was wild type; C STAT2 protein domains, showing pathogenic variants described in patients with STAT2 deficiency presented with HLH phenotype. The c.633 + 2 T > C mutation described here is shown in red affecting the coiled-coil domain; D aberrant splicing of exon 7 of STAT2 showed in Sanger sequencing of RNA from patient and control subjects; E STAT2 protein expression in lysates from IFNα-stimulated PBMCs from the patient and control subjects. HC, healthy controls; P, patient

After clinical recovery, two doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine schedule (Pfizer-BioNTech) were administrated due to the high risk of life-threatening COVID-19. The patient presented an adequate cellular immune response to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein after vaccine administration (Fig. S1). Four months after the last dose, when she was 3 years old, she developed typical features of MIS-C associated to SARS-CoV-2 infection. At hospitalization, she presented with sudden onset of high-spiking fevers, elevated liver enzymes, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and coagulopathy with elevated B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and D-Dimer (Table 1). Blood count revealed mild leukocytosis with progressive development of thrombocytopenia, severe lymphopenia, and mild liver dysfunction that resolved after treatment with vitamin K, two doses of IGIV 1 g/kg, steroids, and anakinra. Elevation of IL-10, IL-6, IFNγ, and IFNα was noted at MIS-C presentation. In comparison with healthy controls, all cytokines normalized 1 month after treatment, except to slightly elevated IFNγ levels (Fig. S2). Viral nasopharyngeal screening by PCR revealed rhinoviral infection. Despite we could not prevent her from developing MIS-C, the two-dose schedule prevented a life-threatening disease. A timeline describing the course of the disease and the treatments administered is represented in Fig. S3.

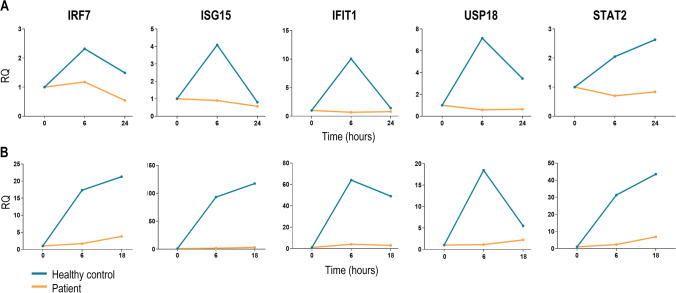

The STAT2 LOF Mutation Abolishes the Immune Response Induced by IFN-I and Could Impair Positive Feedback at Later Stages of Pathway Activation

Firstly, to investigate whether the STAT2 deficiency affected the IFN-I signaling, as has been reported elsewhere [11, 12, 13], gene expression of ISGs was performed in IFNα-stimulated PBMCs and BLCLs at different times in the patient and healthy controls. IRF7, ISG15, IFIT1, USP18, and STAT2 gene expression in PBMCs were severely decreased in the patient compared to healthy controls (Fig. 3A). Decreased ISGs expression was also confirmed in patient BLCLs (Fig. 3B), evidencing the impairment IFN-I-mediated innate immunity.

Fig. 3.

IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) expression. A Quantitative PCR of IRF7, ISG15, IFIT1, USP18, and STAT2 genes in patient (orange lines) and control subjects PBMCs (blue lines) after stimulation with 1000 U/mL of IFNα2 at 0, 6, and 18 h. B Quantitative PCR of IRF7, ISG15, IFIT1, USP18, and STAT2 genes in patient (orange lines) and control subjects BLCLs (blue lines) after stimulation with 1000 U/mL of IFNα2 at 0, 6, and 18 or 24 h. Fold change expression is shown respect to GAPDH basal expression. Duplicated of one of two independent experiments is represented

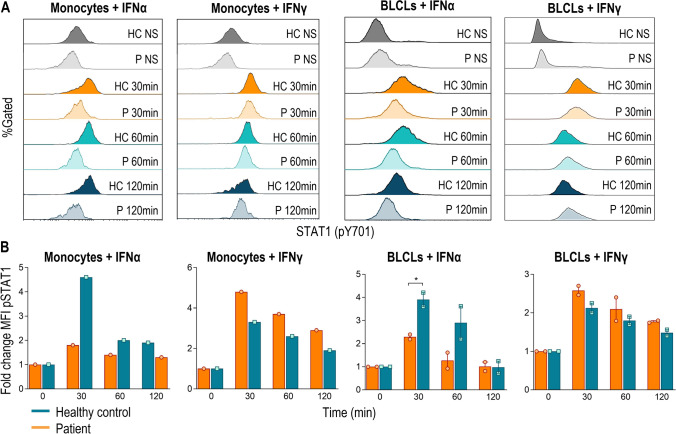

Secondly, IFN-I binds to the IFNα/β receptor and activates preferentially the heterotrimeric ISGF3 complex (STAT1-STAT2-IRF9), but a small fraction of phosphorylated STAT1 homodimerizes forming the IFNγ-activated factor (GAF) [33]. We investigated in peripheral monocytes and BLCLs if STAT1 phosphorylation was altered in both IFNα and IFNγ signaling pathways in the absence of STAT2 (Fig. 4). On the base of the total STAT1 expression was similar in the patient and healthy control (Fig. S4), the patient showed a reduced but not abolished STAT1 phosphorylation when stimulated with IFNα both in monocytes and BLCLs and normal values were observed after IFNγ stimulation (Fig. 4A). The fold change upon IFNα stimulation resulted be half of the values achieved in the control, while the IFNγ pathway was not altered (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

IFNα2-induced STAT1 phosphorylation in monocytes and BLCLs from patient and control subjects. A STAT1 phosphorylation/dephosphorylation kinetics after IFNα or IFNγ (both 1000 U/mL) stimulation at indicated times; B median fluorescence intensity fold change of phosphorylated STAT1 (pY701) in the patient (orange bars) and control subjects (blue bars) after IFNα or IFNγ stimulation at indicated times is represented. One experiment in monocytes and two independent experiments in BLCLs are shown. HC, healthy control. P, patient. NS, no stimulated. *p < 0.05

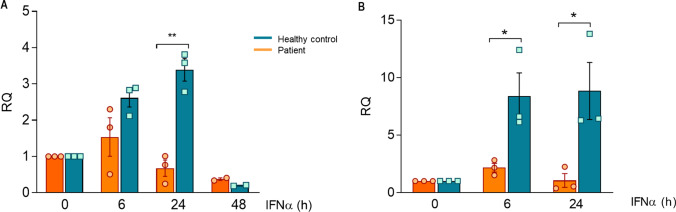

Finally, IFN-I exert a positive feedback by inducing its synthesis through IRF7, an ISG which expression is regulated in turn by ISGF3 stimulation [33, 34]. Thus, we wanted to check if the expression of IFNα after induction of the pathway was affected in the absence of STAT2 (Fig. 5). IFNA expression progressively increased after stimulation with soluble IFNα2 at 6 and 24 h in BLCLs (Fig. 5A) or PBMCs (Fig. 5B) in the healthy controls. In the case of the patient, the expression of IFNA was barely observed at 6 h and severely decreased at 24 h.

Fig. 5.

IFNA2 expression after BLCLs (A) and PBMCs (B) stimulation with soluble IFNα2 (1000 U/mL) during 0, 6, 24, and 48 h. Fold change expression is shown respect to GAPDH basal expression. Three independent experiments are represented in this figure

Discussion

Interferons are key components of the innate immune response and especially IFN-I (IFNα/β) constitute the first line against viral infections. Here, we report a novel case of defects in intrinsic and innate immunity with predisposition to severe viral infection due to STAT2 deficiency. The patient presented innate immune dysregulation showing HLH and, despite proven antibody and T-cell response to vaccination, she experienced MIS-C requiring heavy IL-1 blockade to achieve remission. In any case, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination early in life should be promoted to avoid fatal disease in patients with STAT2 deficiency.

Twenty three patients with STAT2 deficiency underling life-threatening viral infection and systemic inflammation have been described [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14], three of them presented clinical and laboratory criteria for HLH [11, 12, 13]. Interestingly, HLH has increasingly been reported in the context of other inborn errors of IFN-I signaling immunity, including STAT1, IFNAR1, and IFNAR2 deficiencies [16, 17, 18, 20, 35, 36] (Table 2). Almost all patients had suffered from relatively few viral infections uneventfully. However, life-threatening single viral episodes may confer a high mortality risk. In this context, three patients died of multisystem failure after unknown viral infection or severe complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of previously reported inborn errors of IFN-I signaling immunity with HLH features

| Gene | Mutation | Age of onset | Viral phenotype | HLH trigger | HLH criteria | Outcome | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAT2 | p.R510X/ p.G526A | First 3 y | Adenovirus, enterovirus, RSV | HLH 7 d after MMR vaccine | Fever, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, hepatitis (4/8)* | Death of multisystemic failure after viral infection | [11] |

| STAT2 | c.1209 + 1delG | First 1 y | RSV, norovirus, coxsackie virus | HLH 7 d after MMR and varicella vaccines | Fever, pancytopenia, hyperferritinemia, elevated sCD25, hypofibrinogenemia (5/8) | Alive | [12] |

| STAT2 | p.R667X | 9 m | Severe coronavirus HKU1, influenza A, rhinovirus/enterovirus | HLH, HHV and varicella 20 d after Varivax, MMR, HA, HI vaccines | Fever, cytopenia, hyperferritinemia, elevated sCD25, hypertriglyceridemia (6/8) | Alive | [13] |

| STAT2 | c.633 + 2 T > C | 2 m | Sinopulmonary infections | HLH 6 d after MMR vaccine | Fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia, hyperferritinemia, elevatedsCD25, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, HLH cells in bone marrow (7/8) | Alive |

This report |

| STAT1 | c.88delA | 8 m | HHV6 infection | HLH after HHV6 infection and 7 d afte MMR vaccine | Fever, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenia, hyperferritinemia, elevated sCD25 (5/8) | Alive 4 m after HSCT | [19] |

| STAT1 | c.1011_1012delAG | 4 m | Viral meningoencephalitis, bronchitis, keratoconjunctivitis. VZV-like after VZV vaccine | HLH after VZV vaccine | Fever, cytopenia, hypofibrinogenemia, hyperferritinemia, elevated sCD25, HLH cells in bone marrow (6/8) | Death after HSCT | [18] |

| STAT1 |

c.128 + 2 T > G/ c.542–8 A > G |

11 m |

RSV, influenza A, MPV infections; paralytic ileus by rotavirus |

HLH after infection with an unknown pathogen |

Fever, cytopenia, hyperferritinemia, elevated sCD25 (4/8)* | Alive | [20] |

| IFNAR1 | p.Gln308Ter | 15 m | NR | HLH 5 d after MMR vaccine | Fever, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenia, hyperferritinemia, elevated sCD25, hypofibrinogenemia, hypertriglyceridemia (7/8) | Death of cardiorespiratory failure at 21 m | [16] |

| IFNAR2 | p.Leu79Ter/ p.Ile185MetfsTer12 | 22 m | Influenza A and herpes simplex virus | HLH 5 d after MMR vaccine | Fever, cytopenia, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenia (5/8) | Alive | (17) |

*Patient with HLH-like phenotype, without fulfill 5 of 8 criteria required for HLH diagnosis. Abbreviations: y, years; m, months; d, days; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; HHV6, human herpesvirus 6; VZV, varicella zoster virus; MPV, human metapneumovirus; NR, not report

Previously, one patient with STAT2 deficiency has been reported associated with severe COVID-19 pneumonia [37] but the clinical phenotype showed by our patient with HLH and MIS-C is a novel finding associated with STAT2 deficiency. MIS-C has been reported in few patients with inborn errors of immunity, being less common that could be thought [25, 37, 38, 39]. This clinical phenotype associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection has been related both with LOF and GOF IFN-I signaling, as IFNAR1 deficiency or the patient presented here and SOCS1 haploinsufficiency, respectively [37, 40], suggesting that a dysregulated IFN-I activity may play a role in the pathogenesis of MIS-C. However, the dual role of IFN-I in viral infections and viral-induced inflammation remains unclear. During initial stages of viral infection, a rapid synthesis of IFN-I promotes an efficient differentiation of effector T-cells and prompts viral clearance [41, 42]. However, both GOF and LOF IFN-I signaling may become proinflammatory at later stages of infection. In the first case, some studies have evidenced in mice that administration of IFN-I after respiratory virus infection increased immunopathology and inflammatory reaction (43, 44). In the second case, a slower clearance of virus due to impaired IFN-I signaling could lead to continued secretion of inflammatory mediators and cytokines from infected cells [45]. In severe pneumonia in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection, a low IFNα/β production and/or high levels of neutralizing auto-antibodies against IFN-I are associated with a worse evolution of disease, suggesting that IFN-I deficiency could be also a hallmark of severe COVID-19 [46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51]. For this reason, although it has been suggested that IFN-I might be an effective candidate treatment for COVID-19, at later stages of infection, the IFN-I therapy could be contraindicated [43, 52]. Indeed, IFN-I may negatively regulate diverse pro-inflammatory cytokines [21, 22, 24]. Hyperinflammatory conditions found both in GOF and LOF STAT2 patients could reveal a potential role of correctly equilibrated IFN-I signaling to prevent immunopathology, not only as a direct effect against viral replication but also immunomodulating the pro-inflammatory cytokines pathway [15, 53].

In this report, we show a new patient with a novel STAT2 deficiency that presents an impaired IFN-I signaling (Fig. 3). Although an altered STAT1 phosphorylation after IFN-I stimulation has been observed in this patient (Fig. 4), this probably leads to a scarce clinical consequence due to the redundant activation of GAF by IFN-I and IFN-II. Indeed, no mycobacterial infections has been reported in this patient until today. Furthermore, these results showed in the patient a suboptimal expression of IFNα after longer times of stimulation (Fig. 5). As far as we know, we describe for the first-time a possible defect of IFNα expression in a case of STAT2 deficiency. Cytotoxicity is an essential process for the optimal clearance of a viral infection. Genetic alterations compromising CD8 T-cells and NK-cells activity are the most common causes of primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) but a transient defect has also been reported in a patient with an inborn error of innate immunity (IFNAR2 deficiency) with HLH phenotype [17]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that severe COVID-19 patients presented a dysfunctionality in NK degranulation in contrast to non-severe and asymptomatic patients [32]. As occurs with secondary HLH and severe acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, the STAT2 patient showed a mild defect in NK-cell degranulation process, which was normalized when the girl was treated and clinically recovered.

Although these data need to be confirmed in a larger number of patients, a deficient IFNα response and production together with a probable transient defect in the NK-cell activity could contribute to the hyperinflammatory reaction and the HLH triggering in this patient.

Defining the molecular and clinical consequences of variants in STAT2 and other IFN-I pathway-related genes provides insight into the involvement of interferons in human innate immunity. Understanding the cellular and molecular IFN-I signaling is essential to treat and control the fine tuning between hyperinflammation and immunodeficiency in this type of patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

MLN and LMA contributed to conception, design of the study, and drafted the manuscript. MLN did the molecular and functional studies and analyzed the results and constructed the tables and figures. JS and LIGG conducted the clinical and immunological follow-up of the patients and informed them about the study and collected the informed consents approved by the ethics committee. PAV, FJGE, and SG contributed to the cytokine production and response after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine functional assays. ASH and EPA contributed to the critical review of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study has been funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through the project FIS-PI16/2053 and FIS-PI21/1119, and PI21/132 to Luis M. Allende. LGG is supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through the project FIS-PI21/01642. The project has been co-funded by the European Union.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

All experimental work was performed under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Institution (imas12), after written informed consent for publication of clinical and immunological information of the patients.

Consent to Participate

All participants provided written informed consent to participate.

Consent for Publication

All participants have consented to publication of their data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marta López-Nevado, Email: martalopezne@gmail.com.

Luis M. Allende, Email: luis.allende@salud.madrid.org

References

- 1.McNab F, Mayer-Barber K, Sher A, Wack A, O’Garra A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(2):87–103 . doi: 10.1038/nri3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourdon M, Manet C, Montagutelli X. Host genetic susceptibility to viral infections: the role of type I interferon induction. Genes Immun. 2020;21(6):365–79. doi: 10.1038/s41435-020-00116-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tangye SG, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Cunningham-Rundles C, Franco JL, Holland SM, et al. Human inborn errors of immunity: 2022 update on the classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee. J Clin Immunol. 2022. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35748970/. Retrieved October 21 2022 from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10875-022-01289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Bousfiha A, Moundir A, Tangye SG, Picard C, Jeddane L, Al-Herz W, et al. The 2022 update of IUIS phenotypical classification for human inborn errors of immunity. J Clin Immunol. 2022;42(7). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36198931/. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10875-022-01352-z. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Bucciol G, Moens L, Bosch B, Bossuyt X, Casanova JL, Puel A, et al. Lessons learned from the study of human inborn errors of innate immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(2):507–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moens L, Meyts I. Recent human genetic errors of innate immunity leading to increased susceptibility to infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2020;62:79–90 . doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinn IK, Eckstein OS, Peckham-Gregory EC, Goldberg BR, Forbes LR, Nicholas SK, et al. Genetic and mechanistic diversity in pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2018;132(1):89–100 . doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-11-814244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imashuku S, Morimoto A, Ishii E. Virus-triggered secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(10):2729–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hambleton S, Goodbourn S, Young DF, Dickinson P, Mohamad SMB, Valappil M, et al. STAT2 deficiency and susceptibility to viral illness in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(8):3053–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220098110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shahni R, Cale CM, Anderson G, Osellame LD, Hambleton S, Jacques TS, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 deficiency is a novel disorder of mitochondrial fission. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 10):2834–46 . doi: 10.1093/brain/awv182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moens L, Van Eyck L, Jochmans D, Mitera T, Frans G, Bossuyt X, et al. A novel kindred with inherited STAT2 deficiency and severe viral illness. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(6):1995–1997.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alosaimi MF, Maciag MC, Platt CD, Geha RS, Chou J, Bartnikas LM. A novel variant in STAT2 presenting with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(2):611–613.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freij BJ, Hanrath AT, Chen R, Hambleton S, Duncan CJA. Life-threatening influenza, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and probable vaccine-strain varicella in a novel case of homozygous STAT2 deficiency. Front Immunol. 2021;11(February):1–9. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.624415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bucciol G, Moens L, Ogishi M, Rinchai D, Matuozzo D, Momenilandi M, et al. Human inherited complete STAT2 deficiency underlies inflammatory viral diseases. J Clin Invest. 2023; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36976641/. Retrieved April 04, 2023 from https://www.jci.org/articles/view/168321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Gothe F, Stremenova Spegarova J, Hatton CF, Griffin H, Sargent T, Cowley SA, et al. Aberrant inflammatory responses to type I interferon in STAT2 or IRF9 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35182547/. Retrieved November 2022 from https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(22)00185-3/fulltext. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Gothe F, Hatton CF, Truong L, Klimova Z, Kanderova V, Fejtkova M, et al. A novel case of homozygous interferon alpha/beta receptor alpha chain (IFNAR1) deficiency with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(1):136–9 . doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Passarelli C, Civino A, Rossi MN, Cifaldi L, Lanari V, Moneta GM, et al. IFNAR2 deficiency causing dysregulation of NK cell functions and presenting with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Front Genet. 2020;11(September):1–6. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boehmer DFR, Koehler LM, Magg T, Metzger P, Rohlfs M, Ahlfeld J, et al. A novel complete autosomal-recessive STAT1 LOF variant causes immunodeficiency with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like hyperinflammation. J allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(9):3102–11 . doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burns C, Cheung A, Stark Z, Choo S, Downie L, White S, et al. A novel presentation of homozygous loss-of-function STAT-1 mutation in an infant with hyperinflammation-a case report and review of the literature. J allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(4):777–9 . doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakata S, Tsumura M, Matsubayashi T, Karakawa S, Kimura S, Tamaura M, et al. Autosomal recessive complete STAT1 deficiency caused by compound heterozygous intronic mutations. Int Immunol. 2020;32(10):663–71 . doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxaa043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billiau A. Anti-inflammatory properties of Type I interferons. Antiviral Res. 2006;71(2–3):108–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Di Cola I, Ruscitti P, Giacomelli R, Cipriani P. The pathogenic role of interferons in the hyperinflammatory response on adult-onset still’s disease and macrophage activation syndrome: paving the way towards new therapeutic targets. J Clin Med. 2021;10(6):1164. doi: 10.3390/jcm10061164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrat FJ, Crow MK, Ivashkiv LB. Interferon target-gene expression and epigenomic signatures in health and disease. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(12):1574–83 . doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0466-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guarda G, Braun M, Staehli F, Tardivel A, Mattmann C, Förster I, et al. Type I interferon inhibits interleukin-1 production and inflammasome activation. Immunity. 2011;34(2):213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goudouris ES, Pinto-Mariz F, Mendonça LO, Aranda CS, Guimarães RR, Kokron C, et al. Outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection in 121 patients with inborn errors of immunity: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41(7):1479–89 . doi: 10.1007/s10875-021-01066-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):1607–8 . doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakra NA, Blumberg DA, Herrera-Guerra A, Lakshminrusimha S. Multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) following SARS-CoV-2 infection: review of clinical presentation, hypothetical pathogenesis, and proposed management. Child (Basel, Switzerland). 2020;7(7). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32630212/. Retrieved January 2022 from https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/7/7/69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Kumar D, Rostad CA, Jaggi P, Villacis Nunez DS, Chengyu Prince, Lu A, et al. Distinguishing immune activation and inflammatory signatures of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) versus hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(5). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35304157/. Retrieved June 2022 from https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(22)00297-4/fulltext. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Hui-Yuen J, McAllister S, Koganti S, Hill E, Bhaduri-Mcintosh S. Establishment of Epstein-Barr virus growth-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines. J Vis Exp. 2011;57:2–7. doi: 10.3791/3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Almendro-Vázquez P, Laguna-Goya R, Ruiz-Ruigomez M, Utrero-Rico A, Lalueza A, de la Calle GM, et al. Longitudinal dynamics of SARS-CoV-2-specific cellular and humoral immunity after natural infection or BNT162b2 vaccination. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34962970/. Retrieved June 2022 from https://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1010211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Henter JI, Horne AC, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124–31 . doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcinuño S, Gil-Etayo FJ, Mancebo E, López-Nevado M, Lalueza A, Díaz-Simón R, et al. Effective natural killer cell degranulation is an essential key in COVID-19 evolution. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35743021/. Retrieved December 2022 from https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/12/6577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Mogensen TH. IRF and STAT transcription factors - from basic biology to roles in infection, protective immunity, and primary immunodeficiencies. Front Immunol. 2019;8(9):3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Civas A, Island ML, Génin P, Morin P, Navarro S. Regulation of virus-induced interferon-A genes. Biochimie. 2002;84(7):643–654. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(02)01431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischer A, Provot J, Jais JP, Alcais A, Mahlaoui N, Adoue D, et al. Autoimmune and inflammatory manifestations occur frequently in patients with primary immunodeficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(5):1388–1393.e8 . doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.12.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyts I, Casanova JL. Viral infections in humans and mice with genetic deficiencies of the type I IFN response pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2021;51(5):1039–1061. doi: 10.1002/eji.202048793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abolhassani H, Landegren N, Bastard P, Materna M, Modaresi M, Du L, et al. Inherited IFNAR1 deficiency in a child with both critical COVID-19 pneumonia and multisystem inflammatory syndrome. J Clin Immunol. 2022;42(3):471–83 . doi: 10.1007/s10875-022-01215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, Collins JP, Newhams MM, Son MBF, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):334–46 . doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giardino G, Milito C, Lougaris V, Punziano A, Carrabba M, Cinetto F, et al. The impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with inborn errors of immunity: the experience of the Italian Primary Immunodeficiencies Network (IPINet). J Clin Immunol. 2022; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35445287/. Retrieved December 2022 from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10875-022-01264-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Lee PY, Platt CD, Weeks S, Grace RF, Maher G, Gauthier K, et al. Immune dysregulation and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) in individuals with haploinsufficiency of SOCS1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(5):1194–1200.e1 . doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.González-Navajas JM, Lee J, David M, Raz E. Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(2):125–35 . doi: 10.1038/nri3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crouse J, Kalinke U, Oxenius A. Regulation of antiviral T cell responses by type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(4):231–42 . doi: 10.1038/nri3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Channappanavar R, Fehr AR, Vijay R, Mack M, Zhao J, Meyerholz DK, et al. Dysregulated type I interferon and inflammatory monocyte-macrophage responses cause lethal pneumonia in SARS-CoV-infected mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(2):181–93 . doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson S, Crotta S, McCabe TM, Wack A. Pathogenic potential of interferon αβ in acute influenza infection. Nat Commun. 2014;5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24844667/. Retrieved February 2022 from https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Yan N, Chen ZJ. Intrinsic antiviral immunity. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(3):214–22 Available . doi: 10.1038/ni.2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hadjadj J, Yatim N, Barnabei L, Corneau A, Boussier J, Smith N, et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science. 2020;369(6504):718–24. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Q, Bastard P, Liu Z, Pen J Le, Moncada-Velez M, Chen J, et al. Inborn errors of type I IFN immunity in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science 2020;370(6515). Available from: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/370/6515/eabd4570. Retrieved October 2020 from https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abd4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Lee JS, Park S, Jeong HW, Ahn JY, Choi SJ, Lee H, et al. Immunophenotyping of COVID-19 and influenza highlights the role of type I interferons in development of severe COVID-19. Sci Immunol. 2020;5(49):1554 . doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bastard P, Rosen LB, Zhang Q, Michailidis E, Hoffmann H-H, Zhang Y, et al. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. 2020;370(6515). Available from: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/370/6515/eabd4585. Retrieved October 2020 from https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abd4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Contoli M, Papi A, Tomassetti L, Rizzo P, Vieceli Dalla Sega F, Fortini F, et al. Blood interferon-α levels and severity, outcomes, and inflammatory profiles in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Front Immunol. 2021;12. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33767713/. Retrieved December 2021 from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.648004/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Bastard P, Vazquez S, Liu J, Laurie MT, Wang CY, Gervais A, et al. Vaccine breakthrough hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia in patients with auto-Abs neutralizing type I IFNs. Sci Immunol. 2022;19:25. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abp8966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.King C, Sprent J. Dual nature of type I interferons in SARS-CoV-2-induced inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2021;42(4):312–22 . doi: 10.1016/j.it.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duncan CJA, Hambleton S. Human disease phenotypes associated with loss and gain of function mutations in STAT2: viral susceptibility and type I interferonopathy. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41(7):1446–56 . doi: 10.1007/s10875-021-01118-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.