Abstract

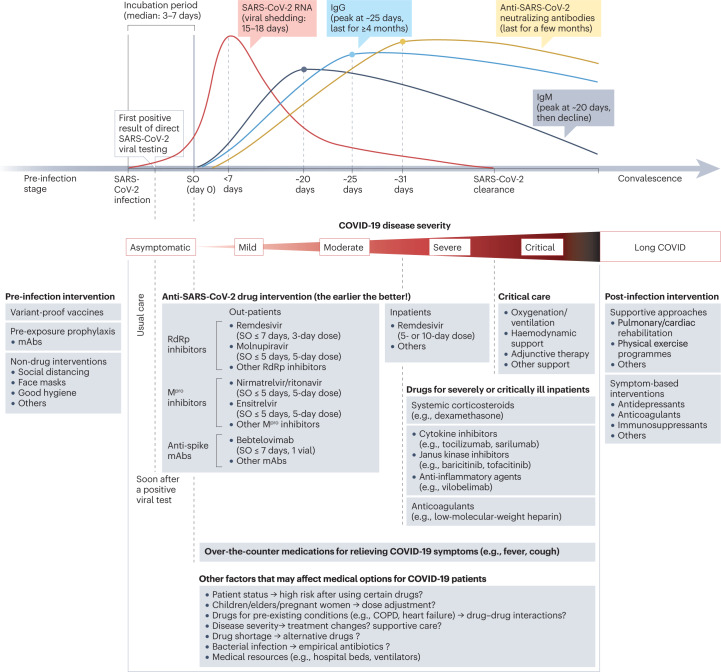

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has stimulated tremendous efforts to develop therapeutic strategies that target severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and/or human proteins to control viral infection, encompassing hundreds of potential drugs and thousands of patients in clinical trials. So far, a few small-molecule antiviral drugs (nirmatrelvir–ritonavir, remdesivir and molnupiravir) and 11 monoclonal antibodies have been marketed for the treatment of COVID-19, mostly requiring administration within 10 days of symptom onset. In addition, hospitalized patients with severe or critical COVID-19 may benefit from treatment with previously approved immunomodulatory drugs, including glucocorticoids such as dexamethasone, cytokine antagonists such as tocilizumab and Janus kinase inhibitors such as baricitinib. Here, we summarize progress with COVID-19 drug discovery, based on accumulated findings since the pandemic began and a comprehensive list of clinical and preclinical inhibitors with anti-coronavirus activities. We also discuss the lessons learned from COVID-19 and other infectious diseases with regard to drug repurposing strategies, pan-coronavirus drug targets, in vitro assays and animal models, and platform trial design for the development of therapeutics to tackle COVID-19, long COVID and pathogenic coronaviruses in future outbreaks.

Subject terms: Antiviral agents, SARS-CoV-2, Antivirals

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, many potential therapeutics that target SARS-CoV-2 and/or human proteins to control viral infection have been investigated, with a few receiving authorization by regulatory agencies. This Review article summarizes progress with COVID-19 drug discovery, and discusses the lessons learned about aspects such as drug repurposing, disease models and clinical development strategies.

Introduction

As the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the seventh coronavirus known to have spilled over from other hosts such as bats and rodents into humans1. Since its discovery in December 2019 (ref. 2), SARS-CoV-2 has caused more than 6.8 million deaths worldwide (see Related links), making it one of the deadliest viruses in human history.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been reflected in the extensive efforts to develop prevention and treatment strategies. So far, these efforts have led to multiple successful vaccines in an exceptionally rapid time frame3,4, as well as the evaluation of a wide range of potential treatments in clinical trials, a few of which have also reached the market (Table 1). Based on lessons learned from six decades of antiviral drug discovery5–8, two types of anti-SARS-CoV-2 agent can be considered. The first type targets viral proteins (mostly viral enzymes) to block the viral life cycle, which may have high selectivity if the targets lack human homologues, but have the potential risk of drug resistance owing to emerging variants5. The second type targets host proteins involved in the viral life cycle (such as the receptors involved in viral entry9,10), which may exhibit broad-spectrum antiviral activities, but with a low degree of selectivity and potentially poor safety profiles6,7. In addition, agents that target human proteins such as immune system modulators may be important in addressing harmful host responses to viral infection, such as ‘cytokine storm’ and thrombosis11.

Table 1.

Therapeutic options for the management of COVID-19 and associated diseases

| Drug name | Type (delivery route) | Use | Eligible patients | Resistance likelihooda | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RdRp inhibitors | |||||

| Remdesivir (Veklury) | Small molecule (i.v.) | Tx | Outpatientsb ≤7 days of symptom onset, or inpatients | Low | Approved by the FDA, EUA in many countries |

| Molnupiravir (Lagevrio) | Small molecule (oral) | Tx | Outpatientsb ≥18 years old and ≤5 days of symptom onset | Low | Approved in the UK, EUA in many countries |

| JT001 (VV116) | Small molecule (oral) | Tx | Outpatientsb ≤5 days of symptom onset | Low | Approved in Uzbekistan |

| Mpro inhibitors | |||||

| Nirmatrelvir–ritonavir (Paxlovid) | Small molecule (oral) | Tx | Outpatientsb ≤5 days of symptom onset | Low | Approved in the UK and EU; EUA in many countries |

| Ensitrelvir (Xocova) | Small molecule (oral) | Tx | Outpatientsb ≤5 days of symptom onset | Low | EUA in Japan, phase III |

| Inhibitors that block the spike–ACE2 interaction | |||||

| Bebtelovimab | mAb (i.v.) | Tx | Outpatientsb ≤7 days of symptom onset | High (e.g., BQ.1, BQ.1.1) | EUA by the FDA; paused owing to resistance |

| Regdanvimab (Regkirona) | mAb (i.v.) | Tx | Outpatientsb ≤7 days of symptom onset | High (e.g., Omicron, Gamma, Beta) | EUA in many countries; paused owing to resistance |

| Sotrovimab | mAb (i.v.) | Tx | Outpatientsb ≤7 days of symptom onset | High (e.g., Omicron) | Approved or EUA in many countries; paused owing to resistance |

| Amubarvimab and romlusevimab | mAbs (i.v.) | Tx | Outpatientsb ≤10 days of symptom onset | High (e.g., Omicron)279 | Approved in China; discontinued |

| Bamlanivimab and etesevimab | mAbs (i.v.) | Tx | Outpatientsb ≤10 days of symptom onset | High (e.g., Omicron, beta) | EUA in many countries; paused owing to resistance |

| PEP | Certain individuals at high risk of COVID-19 | ||||

| Casirivimab and imdevimab (REGEN-COV) | mAbs (i.v. or s.c.) | Tx | Outpatientsb ≤10 days of symptom onset | High (e.g., Omicron) | EUA in many countries, paused owing to resistance |

| PEP | Certain individuals at high risk of COVID-19 | ||||

| Cilgavimab and tixagevimab (Evusheld) | mAbs (i.m.) | PrEP | Certain individuals at high risk of COVID-19 | High (e.g., Omicron) | Approved or EUA in many countries, paused owing to resistance |

| Glucocorticoids | |||||

| Dexamethasone | Small molecule (i.v.) | Tx | Inpatients requiring oxygen support | No | Recommended by COVID-19 guidelines |

| Hydrocortisone | Small molecule (i.v.) | Tx | Inpatients requiring oxygen support | No | Recommended by COVID-19 guidelines |

| Janus kinase inhibitors | |||||

| Baricitinib | Small molecule (oral) | Tx | Inpatients requiring oxygen support | No | Recommended by COVID-19 guidelines |

| Tofacitinib | Small molecule (oral) | Tx | Inpatients requiring oxygen support | No | Recommended by COVID-19 guidelines |

| Cytokine antagonists | |||||

| Tocilizumab | Anti-IL-6R mAb (i.v.) | Tx | Inpatients receiving systemic corticosteroids and requiring oxygen support | No | Recommended by COVID-19 guidelines |

| Sarilumab | Anti-IL-6R mAb (s.c.) | Tx | Inpatients receiving systemic corticosteroids and requiring oxygen support | No | Recommended by COVID-19 guidelines |

| Anakinra | IL-1R antagonist (s.c.) | Tx | Inpatients requiring oxygen supportc | No | EUA by the FDA; authorized in the EU |

| Anticoagulants | |||||

| Various drugs (such as low-molecular-weight heparin) | Various (i.v., s.c. or oral) | Tx, TP | Non-ICU inpatients with no pregnancy190 | No | Recommended by COVID-19 guidelines |

| Anti-C5a inhibitors | |||||

| Vilobelimab | mAb (i.v.) | Tx | Hospitalized adults initiated ≤48 hours of oxygen support | No | EUA by the FDA |

ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; EUA, emergency use authorization; ICU, intensive care unit; IL-6R, interleukin 6 receptor; i.m., intramuscular injection; i.v., intravenous injection; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP: pre-exposure prophylaxis; RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; s.c., subcutaneous injection; TP, thromboprophylaxis; Tx, treatment. aHigh: >10-fold reduction in susceptibility of any SARS-CoV-2 variant. Low: <5-fold reduction in susceptibility. The data were obtained from the drug label. bNonhospitalized patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 and at high risk of progression to severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death (see drug labels). cInpatients with COVID-19 requiring oxygen support who are at risk of progressing to severe respiratory failure and likely to have elevated levels of plasma soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor.

Efforts to develop COVID-19 drugs have been reviewed extensively over the pandemic12–16, although it has been difficult for such reviews to remain timely for long given the exceptional pace at which new results have been reported. Now, with accumulated evidence in the past 3 years, there is an opportunity to summarize progress broadly, consider remaining needs and challenges, and reflect on the lessons learned. Here, we provide a comprehensive overview of virus-targeted and host-targeted agents against SARS-CoV-2, based on an extensive search identifying more than 700 agents that have been reported with anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities in preclinical and/or clinical studies (Supplementary Tables 1–3). Clinical findings for immunomodulators and anticoagulants are highlighted. We also discuss overarching topics in the discovery and development of such agents, including the strengths and limitations of drug repurposing, suitable disease models and clinical trial strategies. Owing to space limitations, readers are encouraged to consult other reviews about SARS-CoV-2 vaccines4,17, diagnostics18,19, biology and pathogenesis20,21, acute and post-acute syndrome22,23, immunology and inflammation24,25, protein structures and functions26,27, emerging variants28,29 and antiviral drugs against other coronaviruses30,31.

Viral targets for antiviral agents

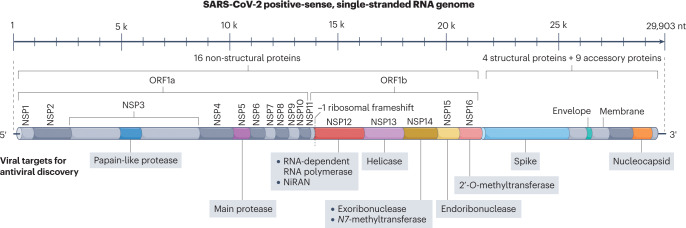

SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus from the Coronaviridae family. With a length of ~29.9 kb, the SARS-CoV-2 genome (Fig. 1) is one of the largest among RNA viruses and encodes 16 non-structural proteins (NSP1 to NSP16), four structural proteins (spike, envelope, membrane, nucleocapsid) and nine accessory proteins26. The development of virus-targeted inhibitors aims to block different stages of the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle (Fig. 2), including entry (spike inhibitors), proteolytic processing (main protease inhibitors, papain-like protease inhibitors), RNA synthesis (NSP12 to NSP16 inhibitors) and assembly (nucleocapsid inhibitors). This section focuses on drug development for these viral targets at various stages of the viral life cycle (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. The SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome.

Antiviral drug targets are indicated beneath the genome map. Accessory proteins are not mapped. NiRAN, nidovirus RdRp-associated nucleotidyltransferase domain; NSP, non-structural protein; ORF, open reading frame; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

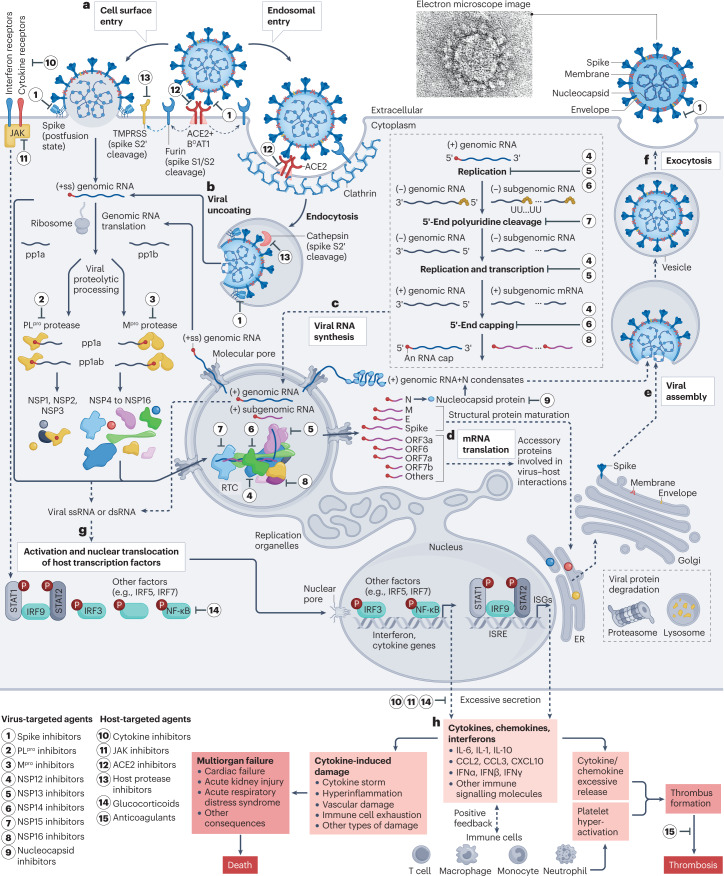

Fig. 2. The life cycle of SARS-CoV-2 and drug targets.

a, Entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) into host cells. The viral spike protein binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (in complex with the sodium-dependent neutral-amino-acid transporter B0AT1) on the membrane surface. Spike is cleaved by furin at the S1/S2 cleavage site and subsequently cleaved at the S2′ site by transmembrane protease serine subfamily (TMPRSS) proteases in the cell surface entry pathway, or cathepsins in the endosomal entry pathway172 (see Fig. 7 for further details). b, Viral uncoating. The (+ss) genomic RNA is released from the viral particle into the host cell. The genomic RNA is translated into open reading frame 1a (ORF1a) and ORF1ab polyproteins (pp1a and pp1ab), which are subsequently cleaved by papain-like protease (PLpro) and the main protease (Mpro) to release 16 non-structural proteins (NSPs). c, Viral RNA synthesis. Several NSPs assemble into the replication–transcription complex (RTC) that replicates and translates viral genomic RNA in replication organelles. d, Viral mRNA translation. Structural proteins are sorted into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus for maturation. Accessory proteins modulate virus−host interactions and viral pathogenesis. e, Viral assembly. The genomic RNA is packed with viral nucleocapsid (N) for viral assembly, along with structural proteins. f, Viral release by exocytosis. g, Viral RNA triggers host immune signalling pathways, which involve activation of transcription factors to produce cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, chemokines such as C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) and C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), and interferons such as interferon-α (IFNα). h, Excessive production and secretion may result in cytokine-induced damage, multiorgan failure, thrombosis or death (see reviews elsewhere11,280,281). Immune cells also provide positive feedback to release more cytokines, chemokines and interferons187. Ps in red circles denote phosphorylation sites. dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; E, envelope protein; IRF, interferon regulatory factor; ISG, interferon-stimulated gene; ISRE, interferon-stimulated response element; JAK, Janus kinase; M, membrane protein; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; ssRNA, single-stranded RNA; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; UU...UU, polyuridines. The electron micrograph image of SARS-CoV-2 (contributed by C.S. Goldsmith and A. Tamin) was retrieved from the CDC Public Health Image Library.

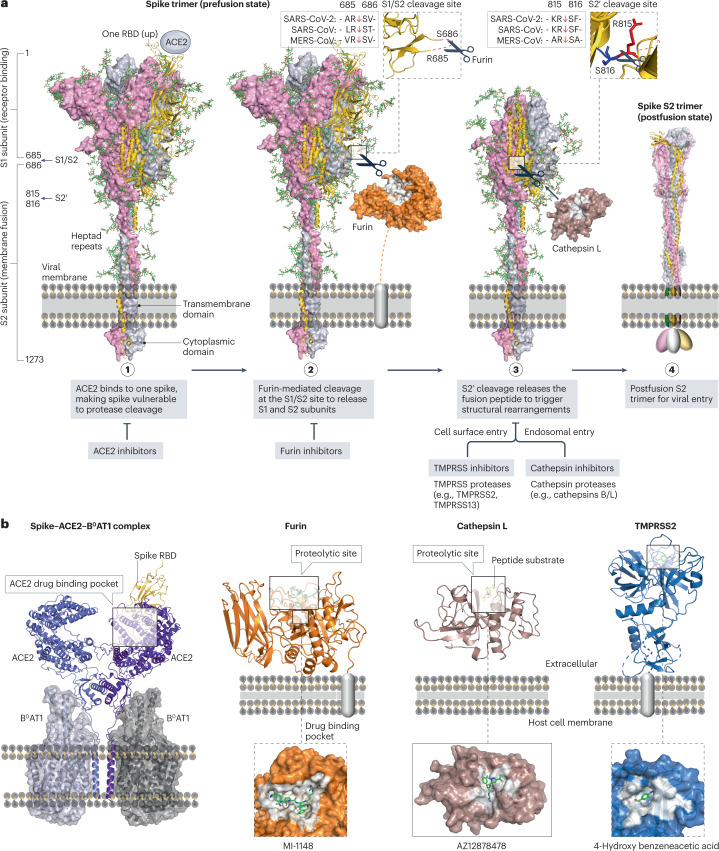

Spike

SARS-CoV-2 spike is a homotrimeric class I fusion glycoprotein on the virion surface that is indispensable for viral entry, making it an attractive antiviral target. In most cases, the spike protein is cleaved by host proteases into a receptor-binding subunit S1 and a membrane-fusion subunit S2, heavily shielded by N-linked and O-linked glycans32. After major conformational rearrangements, the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 spike binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the cell surface with high affinity, almost 22-fold higher than that of SARS-CoV spike for ACE2 (ref. 33). Subsequent structural transitions and proteolytic cleavages drive the postfusion conformation of a three-helix bundle that fuses the viral membrane with the host plasma membrane34. Several types of agent have been developed to inhibit the spike–ACE2 interaction or membrane fusion, including neutralizing antibodies, small-molecule inhibitors and peptide inhibitors.

Anti-spike antibodies

More than 100 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are marketed for the treatment of human diseases, including a few for viral infections, such as palivizumab for respiratory syncytial virus and ansuvimab for Ebola virus12,35. So far, a handful of anti-SARS-CoV-2 mAbs and mAb cocktails have been approved or granted emergency use authorization (EUA), including bebtelovimab, sotrovimab, regdanvimab, bamlanivimab plus etesevimab, cilgavimab plus tixagevimab, casirivimab plus imdevimab and amubarvimab plus romlusevimab (Table 1). Most of these mAbs and cocktails have been authorized as early treatment options to treat outpatients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 (ref. 36). With the continuing emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants, most mAbs are no longer recommended (Box 1) and their efficacy will need to be continually assessed37.

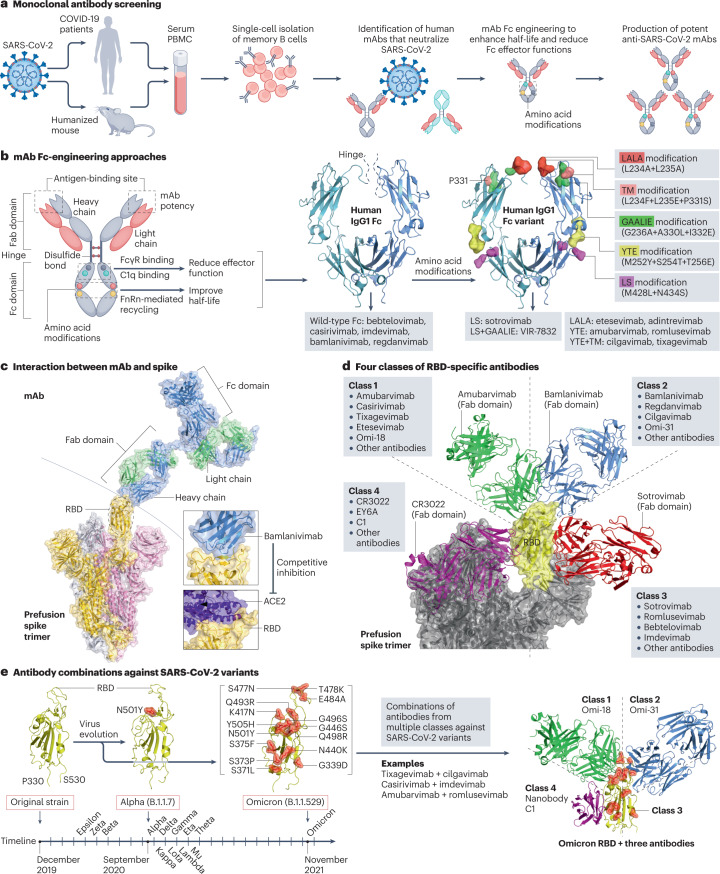

More than 300 anti-SARS-CoV-2 mAbs have been reported, including more than 20 candidates in clinical trials (Supplementary Table 2). These candidates were mostly identified through the screening of antibodies from the memory B cells of convalescent patients or humanized mice exposed to SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 3a). Potent wild-type mAbs can be subsequently engineered with amino acid modifications in the fragment crystallizable (Fc) region to develop mAbs with a longer half-life and enhanced effector functions38. Common Fc modifications include: LALA modification with L234A+L235A; YTE modification with M252Y+S254T+T256E; LS modification with M428L+N434S; TM modification with L234F+L235E+P331S; and GAALIE modification with G236A+A330L+I332E (Fig. 3b). As an example, COV2-2130 and COV2-2196 are two synergistic IgG1κ mAbs engineered with the YTE modification (for half-life extension) and the TM modification (for reduced Fc effector functions), leading to the development of cilgavimab and tixagevimab39. Although all marketed anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies are IgG1 mAbs (Supplementary Table 2), there is also a growing interest in developing polyclonal antibodies such as SAB-185 and XAV-19, nanobodies such as VHH-E, Nb12 and XG014 and biosynthetic proteins such as ensovibep (Supplementary Table 2). Finally, as a natural source of polyclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, high-titre convalescent plasma from COVID-19 survivors might provide passive immunotherapy40,41. However, current evidence does not generally support the efficacy of convalescent plasma in the standard treatment of COVID-19 (refs. 42,43), and its widespread use also poses major challenges, including limited supply, administrative and logistical barriers, and antibody-dependent enhancement of SARS-CoV-2 infection44.

Fig. 3. Development of anti-spike monoclonal antibodies.

a, Screening of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are collected from convalescent donors or humanized mice exposed to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Single-cell cultures of plasma or memory B cells are prepared to screen potent mAbs. b, Fragment crystallizable (Fc)-engineering approaches that modify amino acids in the Fc domain of mAbs to enhance the half-life and reduce the effector functions38. Common modifications such as LALA, TM, LS, YTE and GAALIE are indicated, with their wild-type residues visualized using the structure of human IgG1 Fc (PDB: 4X4M), and their applications in selected mAbs are shown below. c, Structure of a mAb in complex with the prefusion spike trimer. Bamlanivimab (PDB: 7KMG) blocks the binding of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of spike (PDB: 6M17). d, Four antibody classes can be defined based on their interactions with the spike RBD. Representative antibodies from each class are shown, including amubarvimab (class 1, PDB: 7CDI), bamlanivimab (class 2, PDB: 7KMG), S309 (class 3, PDB: 7TNO) and CR3022 (class 4, PDB: 6W41). e, Antibodies from multiple classes can be combined to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 variants. SARS-CoV-2 variants harbour amino acid substitutions in the RBD (for example, 15 mutations in the Omicron variant) that potentially hamper antibody potency. The timeline of the earliest documented samples provided by the WHO (see Related links) shows viral evolution from the SARS-CoV-2 original strain to more than ten variants to date, including Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), Delta (B.1.617.2), Epsilon (B.1.427/B.1.429), Zeta (P.2), Eta (B.1.525), Theta (P.3), Iota (B.1.526), Kappa (B.1.617.1), Lambda (C.37), Mu (B.1.621) and Omicron (B.1.1.529). A three-antibody combination of Omi-18 from class 1, Omi-31 from class 2 and nanobody C1 from class 4 can simultaneously target one RBD of an Omicron variant (PDB: 7ZFB). Fab, fragment antigen binding.

Anti-spike antibodies mitigate SARS-CoV-2 infection through two main mechanisms. One is pathogen neutralization, in which antibodies that bind to spike — especially to the RBD — prevent viral entry45. RBD-binding antibodies make up ~90% of neutralizing antibody titres in COVID-19 convalescent plasma46. The other mechanism is antibody effector functions, in which antibodies mediate the destruction of SARS-CoV-2 virions or infected cells via the opsonization pathway, complement-dependent cytotoxicity and/or antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis and cytotoxicity47. Antibodies developed so far predominantly target the RBD to block the spike–ACE2 interaction (Fig. 3c), except for a few agents such as COV2-3434, S3H3 and 4A8 that target epitopes outside the spike RBD (Supplementary Table 2). RBD-binding antibodies can be categorized into four classes on the basis of the epitope landscape that they target (Fig. 3d). Neutralizing antibodies from different classes that target non-overlapping epitopes could be potentially combined into cocktails with increased potency against SARS-CoV-2 variants (Fig. 3e). Antibody cocktails such as etesevimab (class 1) plus bamlanivimab (class 2) and casirivimab (class 1) plus imdevimab (class 3) have been marketed.

It remains challenging to develop broadly neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants and multiple distinct sarbecoviruses for several reasons. First, the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is highly mutable, enabling the emergence of drug-resistance mutations37. Most existing anti-spike antibodies are weakly active or inactive against Omicron variants of concern such as BA.1, BA.1.1, BA.2, BA.4 and BA.5 (refs. 48,49), the spikes of which harbour >30 amino acid substitutions, including at least 15 located in the RBD (Fig. 3e). To counteract neutralization escape, it is important to develop potent antibodies and their combinations that target highly conserved non-overlapping epitopes within or outside the spike RBD. Second, antibody-based therapies might offer clinical benefits to certain patients early in the disease or those with undetectable anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies50, but benefits are probably limited for inpatients who have already mounted endogenous antibody responses51. For instance, bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) was prematurely withdrawn from the ACTIV-3 trial (NCT04501978) owing to its limited benefits for inpatients with COVID-19. Whether antibody therapies provide benefits in treating severe COVID-19 remains under investigation. Third, serum titres of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies decrease over time52, and RBD-targeted antibodies may protect for only a few months46. Broadly neutralizing super-antibodies53 and antibodies encoded via lipid-nanoparticle-encapsulated mRNA54 may have the potential to provide longer-term protection against variants of concern. Lastly, the need for intravenous or intramuscular infusion of neutralizing antibodies, their strict storage and distribution requirements, and high production costs are important factors that limit the accessibility of neutralizing antibodies to patients living in resource-limited regions with poor medical facilities.

Box 1 COVID-19 treatment guidelines and resources.

COVID-19 guidelines

World Health Organization (WHO): Clinical management of COVID-19

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO): Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Treatment and pharmaceutical prophylaxis of COVID-19

US National Institutes of Health (NIH): COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines

Australian Department of Health and Aged Care: COVID-19 treatments

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Diagnosis and treatments for COVID-19

Federal Ministry of Health (Germany): Together against Corona

Indian Council of Medical Research: COVID-19 guidelines and information on research study

Government of the United Kingdom: COVID-19 guidance and support

Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA): COVID-19 real-time learning network

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): Critical updates on COVID-19 in children

European Respiratory Society (ERS): Management of hospitalised adults with coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19)

Labelling resources and authorization of COVID-19 therapies and vaccines

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

European Medicines Agency (EMA): Treatments and vaccines for COVID-19

Other drug-related databases and resources

Anti-spike small molecules, peptides and engineered proteins

Small molecules such as clofazimine that potentially inhibit SARS-CoV-2 spike have been investigated (Supplementary Table 1) but so far, no results from late-stage clinical trials have been reported. Potential small-molecule inhibitors of the spike–ACE2 interaction such as MU-UNMC-2, P2119, P2165, H69C2, DRI-C23041 and AB-00011778 (Supplementary Table 1) need further optimization before they could progress towards clinical trials.

Several potent anti-spike peptide inhibitors derived from the heptad repeat α-helix regions of SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and HIV-1 spikes were first reported by Jiang’s group55–58. EK1, a 36-amino-acid pan-coronavirus fusion peptide inhibitor derived from the SARS-CoV-2 heptad repeat 2 region, is currently in phase I COVID-19 trials59. Despite their remarkable potency and low toxicity, antiviral peptide inhibitors might be limited by low oral bioavailability, metabolic instability and short circulation time60. Enfuvirtide, which inhibits HIV-1 entry, is the only FDA-approved antiviral peptide, but it is now rarely recommended in clinical practice5. Future studies need to identify peptide inhibitors with better pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) properties and delivery approaches61.

Thermostable designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins) such as ensovibep, FSR16m and FSR22 (Supplementary Table 1) target SARS-CoV-2 spike to block the spike−ACE2 interaction. The phase III ACTIV-3/TICO trial, which was terminated early, showed no clinical benefits of ensovibep (MP0420) in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (ref. 62). However, the phase II/III EMPATHY trial showed clinical benefits of ensovibep in outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19 (NCT04828161). In general, DARPins could provide antiviral options, although optimization may still be needed.

Papain-like protease (part of NSP3)

Papain-like protease (PLpro) is a cysteine protease that cleaves not only the pp1a and pp1ab polyproteins to release viral proteins NSP1, NSP2 and NSP3 (Supplementary Fig. 1a), but also removes host ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) from signalling proteins to suppress innate immune responses63. The PLpro catalytic site contains a classical catalytic triad (Cys111–His272–Asp286) that preferentially cleaves the tetrapeptide motif LXGG↓XX in adjacent viral proteins (NSP1–NSP2, NSP2–NSP3, NSP3–NSP4) and the C-terminal tails of cellular ubiquitin and ISG15 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Nearly 15 Å away from the catalytic site, a flexible β-hairpin loop, known as blocking loop 2 (BL2), controls substrate access to the catalytic site (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

More than 30 potent PLpro inhibitors have been reported (Supplementary Table 1). Based on their mechanisms of action, anti-PLpro agents can be classified into three groups: class (i), covalent inhibitors that form a C–S thioether linkage with the catalytic cysteine; class (ii), non-covalent inhibitors that block the entry of PLpro substrates into the catalytic site; and class (iii), non-covalent inhibitors that target allosteric binding pockets (Supplementary Fig. 1c). In class (i), covalent inhibitors such as VIR250 and VIR251 (ref. 64) are peptidomimetics that mimic the tetrapeptide motif LXGG to inhibit PLpro peptidase activity. The ‘featureless’ two glycine residues of the LXGG motif make the development of potent peptidomimetic inhibitors difficult because only peptide substrates with two glycine residues at the P1 and P2 positions can be accommodated within the substrate-binding pocket65. In class (ii), non-covalent inhibitors such as GRL0617, F0213, acriflavine, Jun9-72-2, Rac3k and XR8-24 (Supplementary Table 1) occupy the BL2 groove to block the channel that is used by substrates to access the catalytic site65. Most of these inhibitors seem to only inhibit SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, but not MERS-CoV, because of sequence and structural dissimilarities at the BL2 groove (Supplementary Fig. 1b). An exception is F0213, which inhibits both SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV PLpro, probably by targeting a narrow substrate-binding pocket adjacent to the BL2 groove66. In class (iii), non-covalent inhibitors such as HE9 target an allosteric pocket (30 Å away from the catalytic site) to block the binding of ISG15 and ubiquitin to PLpro (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Zn-ejector drugs such as disulfiram block an allosteric Zn2+-binding pocket of PLpro (ref. 67). The selectivity and toxicity of allosteric PLpro inhibitors should be evaluated extensively because Zn ejectors may interfere with Zn-containing proteins in humans, and the ISG15-binding pocket is also present in human ubiquitin-specific peptidase 18 (USP18).

PLpro inhibition blocks viral protein maturation and restores human immune responses68. However, the design of selective PLpro inhibitors is challenging, partly because PLpro is structurally similar to a large family of human deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) and DUB-like proteases that also recognize ubiquitin or ubiquitin-like proteins69. DUB and DUB-like proteases are under investigation as therapeutic targets for other human diseases, but no inhibitors of these proteins have yet been approved70. Future development may focus on non-covalent PLpro inhibitors in class (ii) with extensive optimizations that enhance selectivity and potency, and reduce cross-reactions with homologous DUB and DUB-like proteases in humans.

Main protease (NSP5)

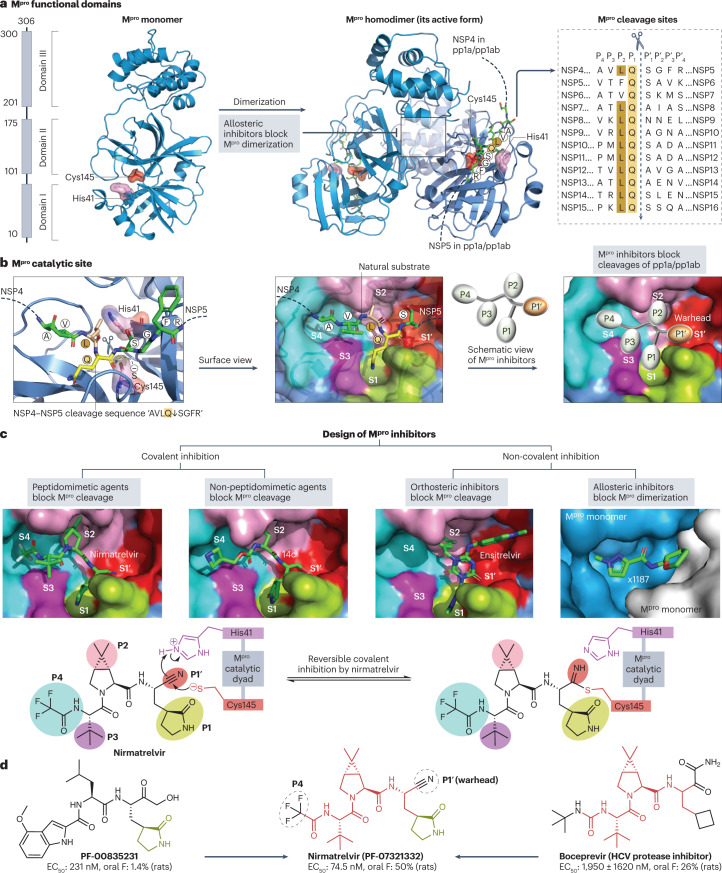

The SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro), also known as 3C-like protease, is a cysteine protease that cleaves the pp1a and pp1ab polyproteins to release viral proteins NSP4 to NSP16 (Fig. 4a). Inhibition of Mpro-mediated proteolytic cleavage prevents the maturation of key viral enzymes such as NSP12 and NSP13, thereby blocking subsequent viral replication (Fig. 2). The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro homodimer has a strong preference for hydrolysing glutamine residues at the P1 position of the cleavage motif Gln↓(Ser/Ala/Asn) (Fig. 4a). Although there is no known host protease with a primary cleavage site identical to that of Mpro71, some human cysteine proteases (for example, cathepsins B, K, L and S) can also cleave at the C-terminal side of Gln residues72; therefore, potential cross-specificity needs to be considered when developing Mpro inhibitors.

Fig. 4. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease and its drug-binding pocket.

a, The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) main protease (Mpro) functional domains, protein structures and cleavage sequences. The Mpro homodimer is the active form (PDB: 7VU6). The cleavage sequence ‘AVLQ↓SGFR’ between adjacent NSP4 and NSP5 in the pp1a and pp1ab polyproteins is localized across the Mpro catalytic dyad formed by Cys145 and His41 (PDB: 7DVP). Mpro cleavage sequences from the reference genome are shown on the right. b, Mpro catalytic site in the pre-cleavage state with the NSP4−NSP5 cleavage sequence (PDB: 7DVP). Mpro inhibitors with P1′ warhead, P1, P2, P3 and P4 moieties can be developed to maximize the drug–receptor interactions at the S1′, S1, S2, S3 and S4 subsites of Mpro, respectively. c, Four classes of Mpro inhibitors and the drug-binding pockets of nirmatrelvir (PDB: 7VH8), 14c (PDB: 7T4B), ensitrelvir (PDB: 7VU6) and x1187 (PDB: 5RFA). Reversible covalent inhibition of nirmatrelvir via the catalytic dyad Cys145−His41 is also shown77. The drug-binding pocket of x1187 is captured at the dimer interface (see panel a). d, Development of nirmatrelvir from PF-00835231 (ref. 78). Nirmatrelvir and boceprevir share identical structures at the backbone and P2/P3 moieties. The half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) values of PF-00835231, nirmatrelvir and boceprevir against SARS-CoV-2 USA_WA1/2020 and oral bioavailability (oral F) in rats were obtained from the literature78,282.

Each subunit of the Mpro homodimer possesses a catalytic dyad that is formed by a nucleophilic cysteine at position 145 (Cys145) and a nearby histidine residue at position 41 (His41)73,74. The Mpro catalytic dyad catalyses the formation of a covalent carbon–sulfur bond between the Cys145 thiolate and the main-chain carbonyl of the substrate’s P1 glutamine75 (Fig. 4b). Similar to the structure-based rational design of HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus (HCV) protease inhibitors5,76, various small-molecule Mpro inhibitors have been designed to maximize drug–receptor interactions, particularly via the formation of extensive interactions with backbone atoms from the S1′, S1, S2, S3 and S4 subsites of Mpro (Fig. 4b).

More than 100 Mpro inhibitors have been reported, including leading candidates such as nirmatrelvir, ensitrelvir and SIM0417 (Supplementary Table 1). Mpro inhibitors can be classified into four groups (Fig. 4c) based on their mechanisms of action: class (i), peptidomimetic inhibitors that covalently bind to the Mpro catalytic pocket; class (ii), non-peptidomimetic inhibitors that block the Mpro catalytic pocket via covalent interactions; class (iii), orthosteric inhibitors that occupy the Mpro substrate-binding pocket through non-covalent reversible interactions; and class (iv), non-covalent inhibitors that target allosteric sites, mostly to impair Mpro dimer formation.

In class (i), peptidomimetic covalent inhibitors commonly bear an electrophilic warhead such as a nitrile (for example, nirmatrelvir), a ketone (for example, PF-00835231), an α-ketoamide (for example, compound 13b-K), an aldehyde (for example, compound 18p) or a Michael acceptor (for example, compound N3) to form a covalent bond with the catalytic Cys145 of Mpro (Supplementary Table 1). Nirmatrelvir is a peptidomimetic that harbours a nitrile warhead that covalently bonds with Cys145 to achieve reversible inhibition77 (Fig. 4c). Nirmatrelvir inhibits all seven human coronavirus (HCoV) wild types78 and various SARS-CoV-2 variants in cell culture79, and substantially reduces viral loads in mice and hamsters80.

In class (ii), non-peptidomimetic covalent inhibitors such as penicillin derivatives81, ebselen derivatives82, ester-derived inhibitors83, spirocyclic derivatives84 and myricetin derivatives85 have been synthesized to block the catalytic pocket of Mpro, but their leads should be further optimized to yield better specificity and fewer off-target effects71.

In class (iii), non-covalent inhibitors such as ensitrelvir, CCF0058981, 23R, ML188 and ML300 (Supplementary Table 1) have been synthesized to block the substrate-binding pocket of Mpro without the formation of new covalent bonds. Based on a virtual-screening hit from pharmacophore filters, ensitrelvir (S-217622) was optimized to occupy the S1′, S1 and S2 subsites of Mpro using hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts and π–π stacking interactions86. Ensitrelvir inhibits many SARS-CoV-2 variants (such as Omicron BA.1 and BA.2) in cell culture86 and reduced SARS-CoV-2 titres in a phase II/III study of patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, mostly within 5 days of symptom onset87. Ensitrelvir was granted emergency regulatory approval in Japan in November 2022. The phase III SCORPIO-HR trial is investigating the efficacy and safety of oral ensitrelvir in high-risk outpatients with COVID-19 (NCT05305547).

In class (iv), allosteric inhibitors such as NB1A2, colloidal bismuth subcitrate and x1187 (Supplementary Table 1) target the Mpro dimer interface to inhibit dimer formation (Fig. 4a); however, their anti-Mpro potency and selectivity require optimization.

So far, nirmatrelvir (PF-07321332) is the most successful Mpro inhibitor, with an unprecedentedly short period of 22 months (March 2020 to December 2021) between drug discovery and market authorization. This rapid programme benefited from previous work on the development of PF-00835231 in 2003 to target the substrate-binding pocket of SARS-CoV Mpro, which shares 96% amino acid sequence identity with that of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (ref. 73). PF-00835231 development was suspended because SARS-CoV had disappeared by late 2004, and many hydrogen bond donors in its structure limited oral delivery88. In an attempt to optimize this early lead, nirmatrelvir was quickly designed by assembling five readily available building blocks78: a nitrile as the warhead; a canonical γ-lactam in the P1 subsite; a bicyclic proline derivative in the P2 subsite, known from boceprevir (an FDA-approved HCV protease inhibitor); a tert-leucine structure in the P3 subsite, known from boceprevir and previously shown to be optimal in tetrapeptidic SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors89; and a trifluoroacetamide group in the P4 subsite (Fig. 4d). This combination of known structural elements was probably the key to the rapid success of nirmatrelvir. Because nirmatrelvir is mainly metabolized by human liver cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor such as ritonavir (an FDA-approved HIV inhibitor with no anti-coronavirus activity) can be co-administered to reduce CYP3A4-mediated metabolic clearance, thereby boosting the therapeutic concentration of nirmatrelvir78.

In the phase II/III EPIC-HR study, early treatment with nirmatrelvir 300 mg plus ritonavir 100 mg twice daily for 5 days reduced COVID-19-related hospitalization (nirmatrelvir–ritonavir: 0.77%, placebo: 6.31%) and 28-day all-cause mortality (nirmatrelvir–ritonavir: 0%, placebo: 1.15%) among high-risk, unvaccinated, nonhospitalized adults with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 (ref. 90). Based on the EPIC-HR study, ritonavir-boosted nirmatrelvir (marketed as Paxlovid) received its first EUA in the USA in December 2021, followed by approval or authorization in many countries. Paxlovid is now recommended as early treatment for outpatients who have mild-to-moderate COVID-19 and are at high risk of progression to severe COVID-19 (Table 1). Nevertheless, preliminary studies indicated occasional COVID-19 rebound after Paxlovid treatment91, and naturally occurring mutations such as E166V in Mpro may confer resistance to nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir92. Paxlovid is not recommended for patients with severe renal or hepatic impairment or a history of clinically significant hypersensitivity reactions, nor for patients taking contraindicated drugs that cause significant drug–drug interactions. Future studies should monitor drug-resistant mutations and drug−drug interactions (for example, with CYP3A4 inducers) that affect the potency and safety of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir.

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (NSP12)

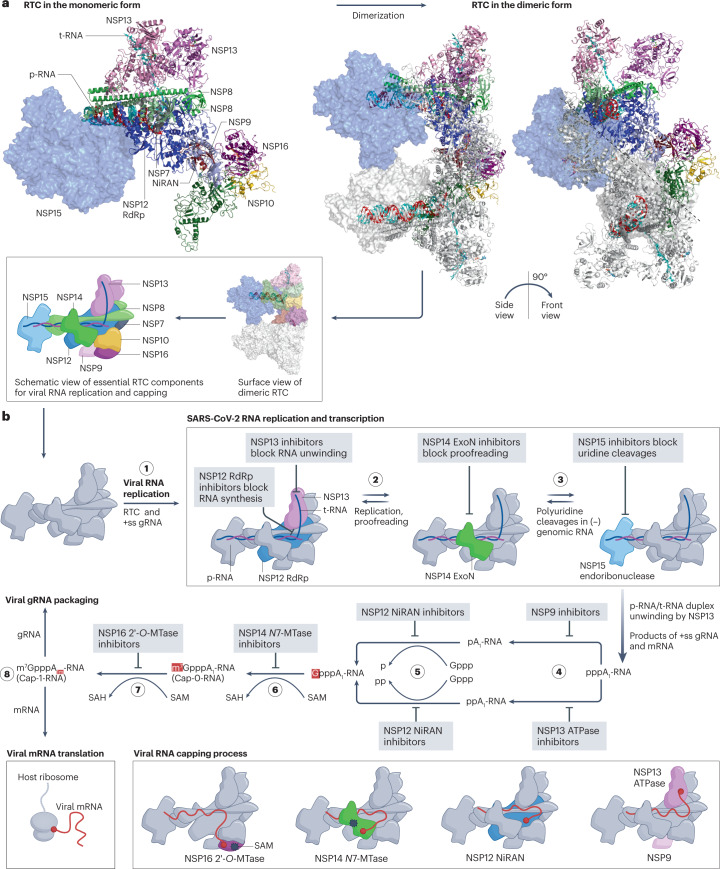

SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), encoded by NSP12, is a highly conserved holoenzyme involved in viral RNA replication and transcription. After Mpro-mediated proteolytic processing, mature NSP12 coordinates with other non-structural proteins (NSP7 to NSP10, NSP13 to NSP16) in the viral replication–transcription complex93 (Fig. 5a), which catalyses template unwinding, RNA synthesis, RNA proofreading and RNA capping27. By targeting key components of the replication–transcription complex (Fig. 5b), a series of antiviral agents can be developed to block RNA synthesis (NSP12 RdRp inhibitors), template unwinding (NSP13 helicase inhibitors), RNA proofreading (NSP14 exoribonuclease inhibitors), uridine cleavage (NSP15 endoribonuclease inhibitors) and RNA capping (NSP9 inhibitors, NSP12 NiRAN inhibitors, NSP13 ATPase inhibitors, NSP14 guanine-N7-methyltransferase inhibitors and NSP16 2′-O-methyltransferase inhibitors). NSP12 inhibitors will be described in this section, while other inhibitors will be addressed later.

Fig. 5. The SARS-CoV-2 replication–transcription complex and its drug targets.

a, Model of the severe acute respiratory virus syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) replication–transcription complex (RTC) in complex with the product RNA (p-RNA) and template RNA (t-RNA), based on the superimposition of protein structures from the PDB codes 7EGQ, 7JYY, 7RDY and 7TQV. The exact structure of the SARS-CoV-2 RTC is yet to be discovered. The monomer is shown on the left, and two views of the active dimeric RTC are shown on the right. A schematic view of the essential RTC components is shown below. b, RTC activities and mechanisms of action of drugs that target it. Step 1: the RTC initiates viral RNA replication after unwinding the viral genomic RNA (gRNA). Step 2: non-structural protein 12 (NSP12) RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and NSP14 exoribonuclease (ExoN) mediate RNA synthesis and proofreading, respectively. Step 3: NSP15 cleaves uridines in the viral single-stranded RNA/double-stranded RNA (ssRNA/dsRNA), especially the long polyuridine tracts at the 5′-end of negative gRNA, to avoid host immune defences146. The products of ss gRNA and mRNA undergo a four-step process (steps 4–8) to complete viral RNA capping for immune evasion93,94. Step 4: NSP13 ATPase hydrolyses and releases the γ-phosphate of the 5′-triphosphate of viral RNA94. An alternative pathway is mediated by the RNAylated NSP9 (refs. 277,283). Step 5: NSP12 nidovirus RdRp-associated nucleotidyltransferase domain (NiRAN) transfers a covalently linked guanosine 5′-monophosphate to the 5′-diphosphate end of viral RNA96. Step 6: the NSP14 guanine-N7-methyltransferase (N7-MTase) domain uses S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as the methyl donor to produce the intermediate Cap-0-RNA structure (m7GpppA1-RNA)284. Step 7: NSP16 2′-O-methyltransferase (2′-O-MTase) uses SAM as the methyl donor to produce the cap-1-RNA structure (m7GpppA1m-RNA)149. Step 8: the capped RNA genome is translocated for viral packaging, while the other capped mRNAs are translocated to host ribosomes for translation. Schematic RTC models involved in the steps of the viral RNA capping process are shown at the bottom of the figure.

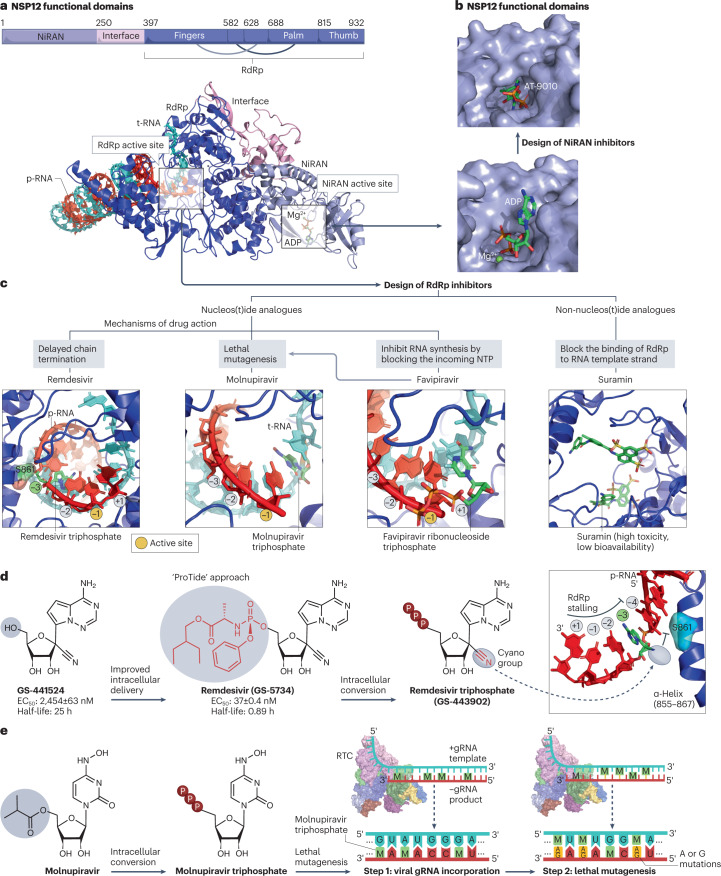

NSP12 is composed of an N-terminal nidovirus RdRp-associated nucleotidyltransferase domain (NiRAN) for viral RNA capping and other activities94,95, a dynamic interface domain and a C-terminal RdRp domain for viral RNA synthesis (Fig. 6a). During viral RNA capping, the NiRAN domain acts as a guanylyltransferase that adds a guanosine 5′-triphosphate to the 5′-end of viral RNA96 (Fig. 5b). The NiRAN active site can be blocked by nucleos(t)ide analogues such as remdesivir triphosphate95 and bemnifosbuvir triphosphate97 (Fig. 6b). However, it is a challenge to develop potent NiRAN inhibitors with high specificity and low toxicity because the NiRAN domain shares significant structural homology with many human kinases, such as insulin receptor kinase, spleen tyrosine kinase and O-mannose kinase98. The SARS-CoV-2 RdRp active site is the key drug target. Similar to HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors99, RdRp inhibitors can be classified into nucleos(t)ide analogues (such as remdesivir, molnupiravir, favipiravir and bemnifosbuvir) and non-nucleos(t)ide analogues (such as suramin) with different mechanisms of action (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6. NSP12 protein structure and its drug-binding pockets.

a, Non-structural protein 12 (NSP12) functional domains (PDB: 7EIZ). NSP12 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and nidovirus RdRp-associated nucleotidyltransferase domain (NiRAN) catalytic sites are highlighted with the template RNA (cyan) and product RNA (red). b, Drug-binding pocket at the catalytic site of the NiRAN domain. ADP (PDB: 7RDY) binds to the NiRAN active site. AT-9010 is the active 5′-triphosphate form of bemnifosbuvir that blocks the NiRAN active site (PDB: 7ED5)97. c, RdRp inhibitors include nucleos(t)ide analogues such as remdesivir triphosphate (PDB: 7B3C), molnupiravir triphosphate (PDB: 7OZU), favipiravir ribonucleoside triphosphate (PDB: 7AAP) and non-nucleos(t)ide analogues such as suramin (PDB: 7D4F). d, Development of remdesivir from GS-441524 using the ProTide approach. The post-translocation positions (+1, −1 to −4) of the nascent base pairs in the product viral RNA (p-RNA) are indicated, and the substrate active site of natural nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) is located at the −1 position107. Remdesivir triphosphate acts as a delayed chain terminator, and its cyano group clashes with S861 of RdRp to stall RNA synthesis107. In vitro half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) and half-life values were obtained from the literature285,286. e, Lethal mutagenesis caused by molnupiravir, which is converted intracellularly into an active triphosphate form (EIDD-2061) that increases the frequency of G-to-A and C-to-U transition errors within genomic RNA (gRNA)122. RTC, replication–transcription complex.

Remdesivir (GS-5734) was initially synthesized in 2013 in a search for a potent nucleoside inhibitor of the respiratory syncytial virus100. To improve its intracellular delivery and bypass the rate-limiting first phosphorylation step, remdesivir was synthesized as a monophosphoramidate prodrug of its parent nucleoside (GS-441524)101 through the addition of an amino acid ester and aryloxy-substituted phosphoryl group102. This prodrug approach, called ‘ProTide’ (Fig. 6d), has been used in two FDA-approved antivirals: the HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitor tenofovir alafenamide and the HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir. After it diffuses across the cell membrane, remdesivir undergoes a series of metabolic conversions to generate the active metabolite remdesivir triphosphate103.

During the 2014–2016 outbreak of Ebola virus, remdesivir was identified as a potent anti-Ebola inhibitor102, but its anti-Ebola use was not pursued because of limited benefits in Ebola-infected patients104. Soon after the COVID-19 outbreak, its anti-SARS-CoV-2 potential was demonstrated in preclinical and clinical studies105. As an analogue of ATP, remdesivir triphosphate competes with natural ATP substrates to be efficiently incorporated into nascent RNA chains, causing delayed chain termination at the post-translocation position −3 (ref. 106) (Fig. 6d). This blockade is mediated by a steric clash of the 1′-cyano group of remdesivir triphosphate with the side chain of Ser-861 (Fig. 6d) near the RdRp catalytic site107. The 1′-cyano group and C-linked nucleobase of remdesivir are crucial for its anti-coronavirus activity107.

Remdesivir was granted an EUA for the treatment of COVID-19 under certain conditions by the FDA in May 2020, which was followed by approval or authorization in many countries. Clinical benefits of remdesivir versus placebo or standard care have been indicated by randomized trials such as ACTT-1 (NCT04280705) and PINETREE (NCT04501952), whereas an added value of remdesivir was absent in Solidarity108 and DisCoVeRy109. Despite such discordance affected by various factors (such as patient status, study design and treatment timing), it is generally agreed that early treatment with remdesivir reduces viral loads and improves recovery for certain patients with COVID-19, especially when administered on an outpatient basis110. Remdesivir is unsuitable for oral administration and lung-specific delivery because of its low oral bioavailability and low stability in human liver microsomes111. These shortcomings might be resolved by developing oral prodrugs of the remdesivir parent such as VV116 (approved in Uzbekistan, conditionally approved in China), GS-5245 (currently in a phase III trial: NCT05603143), ODBG-P-RVn, ATV006 and GS-621763, all of which have favourable oral bioavailability, relatively simple structure and potent anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity (Supplementary Table 1). A randomized phase III trial revealed the noninferiority of oral VV116 versus nirmatrelvir–ritonavir in reducing the time to sustained clinical recovery among symptomatic inpatients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 (ref. 112).

Molnupiravir (EIDD-2801, MK-4482) is an oral prodrug of β-d-N4-hydroxycytidine (EIDD-1931)113. N4-hydroxycytidine has long been known to have mutagenic characteristics, mainly increasing AT to GC transition errors114. Molnupiravir is a mutagenic ribonucleoside analogue that was originally being developed to inhibit influenza A and B viruses113. In early 2020, a repurposing screen of existing compounds led to the discovery that molnupiravir had broad-spectrum activities against SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV in cell culture115 and animal models116. In the phase III MOVe-OUT trial of unvaccinated outpatients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, primary end point events (hospitalization or death by day 29) occurred among 6.8% (48/709) of molnupiravir-treated patients and 9.7% (68/699) of placebo-treated patients117. Molnupiravir was first approved in the UK in November 2021 and has been marketed in many countries since then. In 2022, the platform-adaptive PANORAMIC trial reported no benefit of molnupiravir plus usual care in reducing COVID-19-associated hospitalizations or deaths among high-risk vaccinated adults within 5 days of symptom onset118. A large-scale real-world study also showed no benefit of molnupiravir in reducing hospitalization rates among high-risk outpatients with incomplete vaccination119.

Molnupiravir induces a lethal accumulation of mispaired nucleobases in the viral RNA genome through a mechanism called lethal mutagenesis or error catastrophe120 (Fig. 6e). In the first step, molnupiravir is converted into its active metabolite, β-d-N4-hydroxycytidine 5′-triphosphate (EIDD-2061), which can be recognized as either cytosine or uridine triphosphate owing to ambiguous base-pairing121. In the second step, its active metabolite competes with natural cytosine or uridine triphosphates to be incorporated into the viral template strand, thus increasing the frequency of G-to-A and C-to-U transition errors in the viral RNA genome122. However, molnupiravir-induced mutagenesis requires a comprehensive safety evaluation because mutagenic ribonucleoside analogues might also detrimentally affect cellular DNA synthesis in mammalian cells123. Molnupiravir is only approved for short-term use (≤5 consecutive days) and is not recommended for pregnant women or young patients (<18 years) owing to the potential risk of fetal toxicity and bone and cartilage toxicity. Furthermore, by definition, lethal mutagenesis will increase the viral sequence diversity. It remains unclear whether molnupiravir accelerates SARS-CoV-2 evolution to escape current vaccines and antiviral treatment. There are other mutagenic nucleoside analogues such as favipiravir124, ribavirin, pyrimidine, purine and pyrazine derivatives, the active metabolites of which also engage in erroneous hydrogen bonding and base-pairing125. Lethal mutagens might cause fewer adverse events if their mispairing can be confined to viral RNA.

Favipiravir (T-705), approved in Japan for influenza treatment, is a purine N-nucleoside analogue precursor that exhibits broad-spectrum activities against many RNA viruses126. Favipiravir ribonucleoside triphosphate can be incorporated into the viral RNA primer strand to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 RNA synthesis127, but only high-dose favipiravir reduces SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in Syrian hamsters128. In randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies, favipiravir showed no significant benefit in improving viral clearance among outpatients with mild129, mild-to-moderate130 or asymptomatic or uncomplicated COVID-19 (ref. 131). In the phase III JIKI trial, favipiravir plasma concentrations decreased over time and its lower-than-predicted concentrations failed to improve clinical outcomes of Ebola-infected patients with high viral loads132. Low plasma concentrations of favipiravir (half-life: 2–5.5 h) might be insufficient to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in human lung cells. Despite its emergency use in several countries (including Japan, India and Russia), anti-SARS-CoV-2 use of favipiravir is currently not recommended by the WHO or the FDA (Box 1).

Bemnifosbuvir (AT-527, RO7496998), initially designed for HCV inhibition, is a prodrug of the guanosine nucleotide analogue AT-9010 that shows a dual mechanism of inhibition against SARS-CoV-2 RdRp and NiRAN97. The efficacy and safety of oral bemnifosbuvir versus placebo among high-risk outpatients with COVID-19 are currently being evaluated in the phase III SUNRISE-3 trial (NCT05629962). Galidesivir, an adenosine C-nucleoside analogue, showed limited benefit in a phase I study of 24 inpatients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 (NCT03891420) and has not progressed further. Of the other NSP12 inhibitors (such as 6-72-2a, 5-iodotubercidin, HeE1-2Tyr, 5-hydroxymethyltubercidin) with in vitro activity (Supplementary Table 1), some have obvious limitations that need to be addressed. For example, sangivamycin is an experimental N-nucleoside analogue that exhibits in vitro activity against many SARS-CoV-2 variants133, but targets cellular proteins, including protein kinase C and histone H3-associated protein kinase133. Suramin blocks the binding of viral RNA template strand within the RdRp catalytic site (Fig. 6c) and inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication in Vero E6 cells134. However, suramin has never been recommended for antiviral use because of its poor bioavailability and strong side effects (the negatively charged suramin binds to many human proteins with positively charged surfaces)135.

Helicase (NSP13)

SARS-CoV-2 helicase, a member of the 1B helicase superfamily, has RNA unwinding and adenosine 5′-triphosphatase (ATPase) activities136. The helicase structure includes an N-terminal zinc-binding domain that coordinates zinc ions; a C-terminal RNA-binding ATPase with two RecA-like domains; and stalk and 1B domains that bridge the N-terminal and C-terminal domains94. Dynamic structures of the helical stalk and the 1B domain are unlikely to be druggable, but the RNA-binding site and the ATPase active site (Supplementary Fig. 2) have been identified as conserved drug-binding pockets137.

A few small-molecule leads have been reported to inhibit helicase RNA unwinding (such as FPA-124 and 2-phenylquinoline derivatives) and/or ATPase activity (such as 5645-0263 and ranitidine bismuth citrate) (Supplementary Table 1). However, further optimization to address issues such as off-target toxicity and limited potency is needed, because SARS-CoV-2 and some host helicases such as human DDX helicases138 share similar substrate-binding structures and functions, including double-stranded RNA unwinding and NTPase hydrolysis. Although no helicase inhibitor has yet entered clinical trials for COVID-19, potent helicase inhibitors have been developed for other infectious diseases139, including amenamevir, which is approved in Japan for herpes zoster treatment, and pritelivir, which is in a phase III trial enrolling immunocompromised patients infected with aciclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus (NCT03073967).

NSP14 exoribonuclease and guanine-N7-methyltransferase

SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 has an N-terminal exoribonuclease domain and a C-terminal guanine-N7-methyltransferase domain (Supplementary Fig. 3a) that conduct viral RNA proofreading and capping, respectively140,141. The exoribonuclease domain of NSP14 interacts with its cofactor NSP10 to act as a 3′–5′ exoribonuclease that rectifies viral RNA mispairing by removing misincorporated nucleotides or nucleotide analogues from the 3′-end of the nascent RNA strand141. This proofreading mechanism is indispensable for maintaining the replication fidelity of the long SARS-CoV-2 genome142. It also limits the effectiveness of nucleos(t)ide inhibitors such as ribavirin because NSP14 exoribonuclease rapidly excises ribavirin 5′-monophosphate from the viral RNA143. NSP14 inhibitors that target the exoribonuclease active site have been identified, such as compound#79, A-2 and B-1 (Supplementary Table 1), but off-target effects of these inhibitors should be carefully evaluated because of the structural similarity between NSP14 and human DEDD exonucleases.

NSP14 guanine-N7-methyltransferase is involved in the construction of a viral RNA cap structure that prevents viral RNA degradation and the activation of antiviral immunity144. It transfers a methyl group from the S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) donor to the N7 position of the guanosine 5′-triphosphate of the newly synthesized viral RNA, yielding a Cap-0-RNA structure (Supplementary Fig. 3b). A sulfonamide-based bisubstrate analogue, compound 25, harbours an adenosine to block the SAM-binding pocket and a 3-cyano-4-methoxybenzenesulfonamide ring to occupy the cap-binding pocket145. Other N7-methyltransferase inhibitors (such as pyridostatin, sinefungin and DS0464) also exhibit modest anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities in cell culture (Supplementary Table 1). No NSP14 inhibitor has yet entered clinical trials for COVID-19.

Endoribonuclease (NSP15)

NSP15 is a uridine-specific endoribonuclease (Supplementary Fig. 4a) that cleaves 5′-polyuridine tracts in negative-sense viral RNA (Supplementary Fig. 4b) to evade activation of host immune responses146. The active site of NSP15 Mn2+-dependent endoribonuclease, which cleaves viral RNA substrates and produces the 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiester and 5′-hydroxyl termini146,147, is a potential drug-binding pocket (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Inhibitors identified so far (Supplementary Table 1), such as tipiracil148, a uracil derivative approved for the treatment of colorectal cancer, have weak activities against SARS-CoV-2 (Supplementary Fig. 4d), and further optimizations are needed. In theory, NSP15 endoribonuclease can be an attractive antiviral target owing to the lack of close human homologues.

2′-O-methyltransferase (NSP16)

SARS-CoV-2 NSP16 and its activator NSP10 form a heterodimeric 2′-O-methyltransferase complex (Supplementary Fig. 5) that efficiently converts viral RNA from the Cap-0-RNA into the Cap-1-RNA configuration for evading activation of pattern recognition receptors144,149. Despite their anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities in cell culture, S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (SAH) and SAM derivatives such as sinefungin usually have poor membrane permeability (due to their zwitterionic nature) and high toxicity (due to human methyltransferases such as cap-specific mRNA (nucleoside-2′-O-)-methyltransferase 1 (CMTR1)), therefore limiting their clinical applications150.

NSP16 has structural homology to human CMTR1, which facilitates SARS-CoV-2 RNA methylation as an alternative route151. An experimental adenine analogue, called 3-deazaneplanocin A, suppresses SARS-CoV-2 replication by blocking both NSP16 2′-O-methyltransferase and human CMTR1 synergistically151, but causes undesirable effects such as stunted growth and nephrotoxicity in rodents152. In principle, inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 RNA methylation requires concomitant targeting of both NSP16 and CMTR1 and may have a high risk of toxicity because inhibition of human SAM cycle-related enzymes will damage human mRNA maturation151.

Nucleocapsid

The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid is a flexible and multivalent protein (Supplementary Fig. 6) with multiple functions including viral genome packaging153 and suppression of innate antiviral immunity154. However, it remains a challenge to develop nucleocapsid inhibitors. First, drug-binding pockets in nucleocapsid, unlike those of viral proteases and RdRp, seem to be structurally dynamic153, thereby making it difficult for stable drug binding. Second, the nucleocapsid is the most abundant SARS-CoV-2 protein and folds into the intricate ribonucleoprotein complex with viral RNA. Third, current nucleocapsid inhibitors are inferior to protease and RdRp inhibitors regarding antiviral potency and binding affinity. Despite active research in the past 30 years, no antiviral nucleocapsid inhibitor has been approved.

Other viral targets

Non-structural proteins such as NPS1, NSP6, NPS7 and NSP9 have also been explored as antiviral targets (Supplementary Table 1). Nevertheless, the specificity and potency of their potential inhibitors, mostly obtained from drug repurposing, requires further improvement and evaluation. SARS-CoV-2 accessory proteins (such as open reading frame 3a (ORF3a), ORF6 and ORF9b) are involved in a wide variety of functions, including viral replication, immune evasion, autophagy and/or apoptosis155. Although a few compounds have been screened for inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 accessory proteins (Supplementary Table 1), such proteins are generally dispensable for the viral life cycle156.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA structures at the conserved region are potential targets for the development of nucleic acid therapeutics (Supplementary Table 1) such as antisense oligonucleotides (for example, ASO4 (ref. 157)) and small interfering RNAs (for example, O3 (ref. 158) and C6G25S159). However, their widespread application faces challenges such as manufacturing160. No RNA-based inhibitor has yet reached COVID-19 trials.

Host targets for antiviral agents

SARS-CoV-2 hijacks host factors (n > 300) to complete its viral life cycle10, including key cellular proteins such as ACE2. Despite their limitations concerning drug selectivity and safety, antiviral agents that target conserved human proteins have the potential advantage of broad-spectrum activities against emerging variants and multiple viruses6,9. A successful example is ibalizumab, an FDA-approved mAb that binds to the T cell surface glycoprotein CD4 to inhibit viral entry of HIV-1 and HIV-2 multidrug-resistant strains161. This section introduces important host proteins that have been explored as antiviral targets to interrupt the viral entry or replication of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 2).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)

ACE2 is the primary entry receptor (Fig. 7a) for some human coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and HCoV-NL63 (ref. 162). At the initial stage of viral entry into host cells, the N-terminal domain of the ACE2 dimer163 on the cell surface is recognized by the spike RBD (Fig. 7b). SARS-CoV-2 infection subsequently decreases ACE2 expression and weakens ACE2-mediated regulation of the human renin–angiotensin system, resulting in pulmonary hypertension, inflammation and cardiovascular complications164.

Fig. 7. Interactions between spike, ACE2 and cellular proteases as drug targets.

a, Structural rearrangements of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike trimer from the prefusion state (PDB: 7WEA) to the postfusion state (PDB: 6XRA). Viral entry is initiated via the binding of one prefusion spike with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), rendering the spike cleavage sites vulnerable to host proteases. The SARS-CoV-2 spike undergoes extensive conformational changes from the closed (down) prefusion state to the open (up) fusion-prone state. Subsequently, furin and cellular proteases (such as cathepsins B/L and transmembrane protease serine subfamily (TMPRSS) 2/13) cleave the S1/S2 site and the S2′ site of the spike, respectively. b, Drug-binding pockets within the spike–ACE2–B0AT1 complex (PDB: 6M17), furin in complex with MI-1148 (PDB: 4RYD), cathepsin L in complex with the Gln-Leu-Ala peptide substrate (PDB: 3K24) and AZ12878478 (PDB: 3HHA), and TMPRSS2 in complex with 4-hydroxy benzeneacetic acid (PDB: 7MEQ), which is the active metabolite of camostat mesylate.

One potential therapeutic strategy aims to block SARS-CoV-2 entry into host cells by mimicking ACE2 with peptide fragments165 or mini-proteins such as APN01, a soluble extracellular fragment of wild-type human ACE2 (ref. 166). However, compared with placebo control, APN01 offered no significant benefit in 28-day all-cause mortality or any use of invasive mechanical ventilation in a phase II trial involving inpatients with COVID-19 (NCT04335136). Small molecules such as SB27041 that target ACE2 have also been investigated as potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents in preclinical studies (Supplementary Table 3). SB27041 targets the allosteric binding pocket of ACE2 and possibly induces conformational changes to block interactions between ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 spike without affecting ACE2 enzymatic functions167.

Cellular proteases

Cellular proteases, such as furin, transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), cathepsin proteases, ADAM10 and ADAM17, cleave and prime SARS-CoV-2 spike for viral entry168–170. Membrane fusion of SARS-CoV-2 virions into host cells depends on proteolytic cleavage of viral spike via a two-step process (Fig. 7a): first, furin-mediated cleavage at the S1/S2 site (684AR↓SV687) to release the receptor-binding subunit S1 and the membrane-fusion subunit S2 (ref. 171); and second, proteolytic cleavage at the S2′ site (814KR↓SF817), located within the membrane-fusion subunit S2, to release the fusion peptide of spike that anchors the host cell membrane172. Cleavage at the S2′ site is processed by TMPRSS2 or TMPRSS13 during rapid cell–membrane fusion173 or endosomal cathepsin proteases (primarily cathepsin B and L) during slow endosomal internalization174. Omicron replicates quickly in the human bronchus175, but it is less pathogenic, probably because the Omicron spike has an altered preference for cathepsin-mediated endosomal entry176.

Camostat mesylate and nafamostat mesylate, approved in Japan for the treatment of noninfectious conditions such as pancreatitis, are oral serine protease inhibitors that target TMPRSS2 to block the membrane fusion of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 7b) in cell culture and animal models168,177. However, two double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trials independently showed no clinical benefit of camostat mesylate among hospitalized adults with COVID-19 (NCT04657497, NCT04321096). Another two open-label randomized controlled trials also consistently reported no benefit of nafamostat mesylate among inpatients with COVID-19 (NCT04623021, NCT04473053). Other TMPRSS2 inhibitors (such as N-0385, avoralstat, MM3122), cathepsin L inhibitors (such as E-64d, K777 and Z-FY-CHO) and furin inhibitors (such as decanoyl-RVKR-CMK) may suppress spike cleavage to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in cell culture and/or animal models (Supplementary Table 3). Nevertheless, applications of antiviral inhibitors targeting a single cellular protease remain a challenge because SARS-CoV-2 uses multiple entry pathways in a cell-type-dependent manner. In general, single-protein blockade of cellular proteases might be insufficient for complete virus inhibition, while a combination of multiple protease inhibitors usually causes severe toxicity.

Other host proteins

In addition to ACE2 and cellular proteases, many host proteins such as farnesoid X receptor178, bromodomain-containing protein 2 (ref. 179), caspase-6 (ref. 180), CD147 (ref. 181), eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1A182, glycogen synthase kinase 3 (ref. 183) and transmembrane protein 16F184 have been explored for the development of anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents (Supplementary Table 3). Most such agents are in preclinical development, with a few having entered clinical trials. Sabizabulin, a microtubule disruptor with potential antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities, reduced all-cause mortality by day 15, 29 and 60 in a small cohort of high-risk adults hospitalized with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 (ref. 185). Meplazumab, a humanized anti-CD147 IgG2 mAb, plus standard care reduced the 29-day mortality and viral loads in a phase II/III study of inpatients with severe COVID-19 (ref. 186). In theory, inhibitors targeted at conserved host proteins overcome drug resistance, but their efficacy and safety profiles require evaluation. Future development of host-targeted inhibitors may focus on host proteins that are indispensable for the viral life cycle.

Targeting immune and inflammatory responses and coagulation

SARS-CoV-2 infection induces dysfunctional immune responses and aggressive inflammatory responses that are often associated with severe manifestations, including fatal systemic inflammation, cytokine storm, multiorgan damage and acute respiratory distress syndrome24,187,188. Repurposing a wide range of marketed immunomodulators and anticoagulants, as well as some investigational drugs, has been extensively explored to mitigate dysfunctional responses in patients with COVID-19 (refs. 189,190). However, many of these agents have not resulted in meaningful beneficial effects in clinical trials (Supplementary Table 4), and this section focuses on those with conclusive evidence. Limitations of drug repurposing in the context of COVID-19 are discussed later.

Systemic corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids are widely available and affordable anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs for the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases191. Corticosteroids can be classified into glucocorticoids (such as dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, prednisolone and methylprednisolone) and mineralocorticoids (such as fludrocortisone). The former exert anti-inflammatory action and immune regulation with clinical benefits for inpatients with severe COVID-19 (refs. 192,193). The latter bind to cellular mineralocorticoid receptors to regulate the salt and water balance192 and probably have no beneficial effect on COVID-19 outcomes194.

Dexamethasone and hydrocortisone are now recommended36, mostly for inpatients with COVID-19 who are receiving oxygen support (Table 1). Dexamethasone is the first glucocorticoid identified with clinical benefit among inpatients with severe COVID-19. Soon after the COVID-19 outbreak, the RECOVERY study showed that dexamethasone significantly reduced 28-day mortality among inpatients with COVID-19 who required respiratory support195. Dexamethasone alone or combined with tocilizumab and antivirals is beneficial for treating moderate-to-severe or critical COVID-19 (ref. 196). Yet, such a benefit was not observed among inpatients who did not require respiratory support195, and dexamethasone even increases the risk of severe drug-related adverse events among inpatients with severe COVID-19 (ref. 197). Unlike systemically administered dexamethasone, inhaled glucocorticoids such as budesonide198,199 and ciclesonide200,201 exhibited inconsistent findings in randomized clinical trials.

Systemic corticosteroid therapies are known to cause severe adverse effects such as osteoporosis, adrenal suppression, cardiovascular disease and hyperglycaemia, especially when used at high doses for a prolonged period202. In fact, corticosteroid therapy represents a double-edged sword to treat COVID-19 because its immunosuppressive properties may harmfully suppress antiviral immune responses in humans, especially during early disease progression203. Further studies need to address the optimal dose and treatment timing of systemic glucocorticoids in patients with COVID-19 because their benefits probably depend on the timing of drug initiation, dosage and COVID-19 severity.

Janus kinase inhibitors

Janus kinases (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, tyrosine kinase 2) belong to a family of receptor-associated tyrosine kinases that modulate immune responses by activating JAK–STAT signalling pathways and transcriptional regulation in response to extracellular cytokines, interferons and growth factors204. JAK inhibitors such as baricitinib and tofacitinib have already been approved for treating immune–mediated inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, and so are readily available for drug repurposing to reduce inflammation and suppress COVID-19-associated immune dysregulation205,206.

In May 2022, the FDA approved a new indication for baricitinib in hospitalized adults with COVID-19 who require oxygen support (Table 1). The oral regimen of baricitinib (tofacitinib is an alternative option if baricitinib is unavailable) plus systemic glucocorticoids such as dexamethasone is recommended by the NIH and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines to inpatients with severe or critical COVID-19 under certain conditions (Box 1). The efficacy and safety of baricitinib in inpatients with COVID-19 have been shown in randomized phase III trials such as RECOVERY207, COV-BARRIER208 and ACTT-2 (ref. 209). Both RECOVERY and COV-BARRIER reported a benefit of baricitinib in reducing 28-day all-cause mortality207,208. Adding baricitinib to remdesivir was superior to remdesivir alone in reducing recovery time and 28-day all-cause mortality209. With established safety profiles, baricitinib offers potential benefits for inpatients with COVID-19, especially the elderly205. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib were shown in the STOP-COVID trial of 289 hospitalized adults mostly receiving glucocorticoids210. The incidence of death or respiratory failure through day 28 was lower in the tofacitinib group than in the placebo group, although this study was not powered to detect a difference in mortality210. The short-term use of tofacitinib and baricitinib is unlikely to be associated with off-target effects such as thrombosis, secondary infections and immunosuppression208–210.

Other JAK inhibitors such as fostamatinib, nezulcitinib, ruxolitinib and pacritinib have been evaluated in COVID-19 trials. A phase II trial of 59 hospitalized patients showed the clinical benefits of fostamatinib (NCT04579393), and a phase III trial (NCT04629703) is ongoing. Nezulcitinib (TD-0903) reduced 28-day all-cause mortality in a phase II trial of 235 inpatients with severe COVID-19 (NCT04402866). Compared with placebo plus standard care, ruxolitinib plus standard care showed no clinical benefit for inpatients with COVID-19 in the phase III RUXCOVID trial (NCT04362137). The phase III PRE-VENT study reported no significant benefit of pacritinib over placebo among inpatients with severe COVID-19 (NCT04404361). Overall, JAK inhibitors alone are insufficient for treating COVID-19 (ref. 211), and the optimal timing of JAK inhibitor treatment requires further investigation.

Cytokine antagonists

More than 20 interleukin or interleukin receptor antagonists have been approved, mostly for the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (Supplementary Table 5). Blockade of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and their receptors is a possible therapeutic strategy to reduce aggressive inflammatory responses and to mitigate exacerbated cytokine release in patients with COVID-19 (refs. 24,187,188). Among the long list of cytokines and chemokines, IL-6 has been recognized as a pleiotropic cytokine strongly associated with COVID-19 severity212. Repurposing IL-6 receptor antagonists such as tocilizumab thus reduces inflammatory responses and improves clinical outcomes in inpatients with COVID-19 (ref. 213). Based on the RECOVERY trial (see Related links), which involved 4,116 COVID-19 inpatients with hypoxia and systemic inflammation at baseline, adding tocilizumab to standard care (glucocorticoids in 82% of cases) improved 28-day hospital discharge, lowered 28-day all-cause mortality and reduced the percentage of patients reaching the composite end point of invasive mechanical ventilation or death213. Nevertheless, compared with standard care, tocilizumab plus standard care (concomitant glucocorticoids in only 19% of cases) did not reduce 28-day mortality in a phase III trial of inpatients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia214. In June 2021, tocilizumab was granted an EUA by the FDA for the treatment of COVID-19 inpatients receiving systemic corticosteroids and requiring supplemental oxygen (Table 1).

Apart from tocilizumab, many cytokine antagonists have been evaluated in COVID-19 trials. Clinical benefits of the IL-6 receptor antagonist sarilumab versus placebo or standard care have been indicated in a randomized platform trial called REMAP-CAP215, whereas added value of sarilumab was absent in Sarilumab-COVID-19 (NCT04315298) and Sarilumab COVID-19 Global Study (NCT04327388). In the REMAP-CAP study, the 180-day all-cause mortality was reduced among critically ill adults in intensive care units who received sarilumab or tocilizumab during their COVID-19 hospitalization216. Clazakizumab, an experimental IL-6 antagonist, improved clinical outcomes among COVID-19 inpatients with hyperinflammation217.

Anakinra, an IL-1 receptor antagonist, reduced 28-day all-cause mortality and hospital stay of inpatients with COVID-19 in SAVE-MORE (NCT04680949) but failed to show clinical benefits in REMAP-CAP (NCT02735707) and CORIMUNO-ANA-1 (NCT04341584). Differing outcomes have also been seen with three experimental mAbs that inhibit granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor: lenzilumab in LIVE-AIR218, gimsilumab in BREATHE219 and namilumab in CATALYST220. Clinical benefits of canakinumab (an IL-1β antagonist) and secukinumab (an IL-17 antagonist) among severely ill inpatients have not been shown in the randomized trials CAN-COVID221 and BISHOP222, respectively. CERC-002, a human anti-LIGHT mAb, reduced serum levels of the LIGHT cytokine in a small study of inpatients with COVID-19-associated pneumonia and mild-to-moderate acute respiratory distress syndrome (NCT04412057). Infliximab, a tumour necrosis factor antagonist, reduced the 28-day all-cause mortality and improved 14-day clinical status in the phase III ACTIV-1 IM study (NCT04593940).

Why do IL-6 antagonists offer clinical benefits but other interleukin antagonists seem less effective? This may be explained by the fact that IL-6 concentrations are highly elevated in patients with severe-to-critical COVID-19, but other interleukins are less so212,223. However, the administration of IL-6 (receptor) antagonists should be closely monitored based on serum cytokine levels, the timing of cytokine blockade and the optimal dose36.

Interferon therapies

Type I interferons, such as interferon-α (IFNα) and IFNβ, are known for their important roles in antiviral immune responses against viral infections224,225. Pegylated IFNα-2a/2b and IFNβ-1a have been approved for treating hepatitis infection and relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis, respectively5. Early treatment with IFNβ-1b plus remdesivir may shorten viral shedding and hospitalization in high-risk patients226. Peg-IFNλ-1a reduced the incidence of hospitalization or emergency department visit in the phase III TOGETHER study of outpatients with COVID-19 (ref. 227), whereas IFNβ-1a showed no benefit in reducing overall mortality, initiation of ventilation or duration of hospital stay among inpatients with COVID-19 (ref. 228). For inpatients requiring high-flow oxygen at baseline, IFNβ-1a even increased the frequency of adverse effects such as respiratory failure229.

Other anti-inflammatory agents

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents can be considered as adjunctive therapy to mitigate SARS-CoV-2-induced hyperinflammation, potentially reducing the risk of progression to severe COVID-19 (ref. 230). Topotecan, an FDA-approved anticancer compound, inhibits human topoisomerase 1 to suppress SARS-CoV-2-induced lethal inflammation in animal models231, and it is being evaluated in a phase I study (NCT05083000). Vilobelimab, an anti-C5a mAb that blocks the C5a–C5aR1 signalling axis to mitigate inflammation and coagulation232, reduced 28-day all-cause mortality among mechanically ventilated inpatients with COVID-19 in the phase III PANAMO study233. In April 2023, the FDA granted an emergency use of vilobelimab in hospitalized adults with COVID-19 when initiated within 48 hours of oxygen support.

Anticoagulants