Abstract

HemN is a radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) enzyme that catalyzes the anaerobic oxidative decarboxylation of coproporphyrinogen III to produce protoporphyrinogen IX, a key intermediate in heme biosynthesis. Proteins homologous to HemN (HemN-like proteins) are widespread in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Although these proteins are in most cases annotated as anaerobic coproporphyrinogen III oxidases (CPOs) in the public database, many of them are actually not CPOs but have diverse functions such as methyltransferases, cyclopropanases, heme chaperones, to name a few. This Perspective discusses the recent advances in the understanding of HemN-like proteins, and particular focus is placed on the diverse chemistries and functions of this growing protein family.

Keywords: radical SAM, heme, catalytic promiscuity, biosynthesis, radical addition, homolytic substitution

Introduction

Heme is one of the most abundant cofactors in nature and plays essential roles in many fundamental biological processes, such as respiration, photosynthesis, and the metabolism and transport of oxygen.1 The metabolic pathways of heme, including acquisition, biosynthesis, and degradation of this cofactor, are required nearly in all living organisms. Biosynthesis of heme begins with the formation of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA), which is converted to a tetrapyrrole macrocyclic intermediate coproporphyrinogen III.2,3 A subsequent oxidative decarboxylation catalyzed by coproporphyrinogen III oxidase (CPO) converts coproporphyrinogen III to protoporphyrinogen IX. Two evolutionarily and mechanistically distinct families of CPO have evolved in Nature. For most eukaryotes, the reaction is catalyzed by aerobic CPO HemF, which uses molecular oxygen as an oxidant.4−8 For many bacteria, however, the same reaction is catalyzed by anaerobic CPO HemN, an oxygen-sensitive protein that utilizes S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as the oxidant.9 It is noteworthy that the CPO-independent heme biosynthetic pathways have also been identified in various prokaryotes.10−12

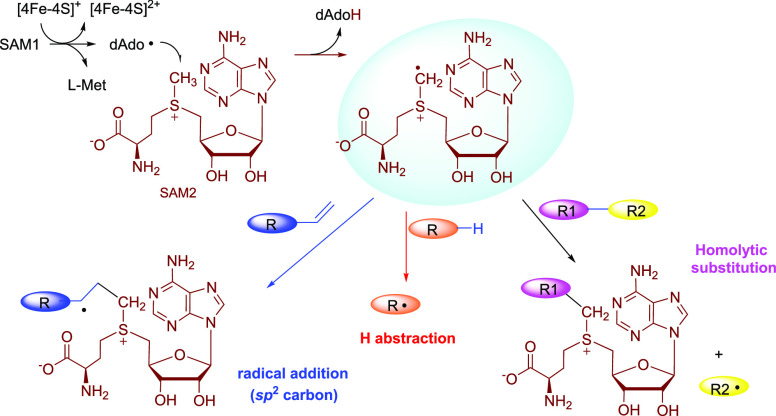

HemN belongs to the radical SAM superfamily, one of the largest known enzyme families consisting of more than 700 000 members13 (e.g IPR007197 in the InterPro database14). These enzymes contain a [4Fe-4S] cluster to bind SAM and reductively cleave its carbon–sulfur bond to produce a highly reactive 5′-deoxyadenosyl (dAdo) radical, which initiates highly diverse reactions.15,16 Although the anaerobic CPO activity is only essential for a subset of bacteria, the predicted HemN proteins are widespread in Nature and have been found in all three domains of life. At time of writing this Perspective, more than 17 000 sequences are found in the IPR004558 family annotated as oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase HemN.14 However, only a small fraction of the HemN-like proteins are CPOs per se, whereas most proteins annotated as HemN are not CPOs. The non-CPO activities of HemN-like proteins include heme transfer and degradation and C1 transfer in the biosynthesis of various natural products. Despite the diverse reactions catalyzed by HemN-like enzymes, these enzymes appear to share a common paradigm by binding two SAM molecules simultaneously in the active site (Figure 1) and generating a unique SAM-based methylene radical 1 to initiate the reaction (Figure 2A).17−19 This Perspective highlights the recent advances in the functional and mechanistic study of HemN-like proteins. The distribution, phylogeny, and catalytic promiscuity of these proteins are also discussed. It is noteworthy that HemN was also named CpdH and CgdH in the literature,2,18 and in this Perspective the nomenclature HemN is used, as it is more prevalent in public databases.

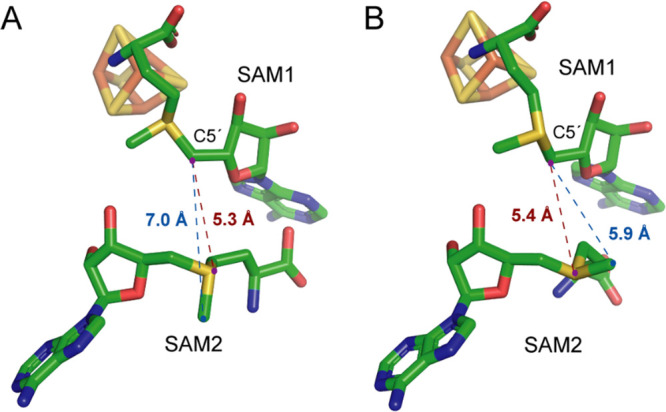

Figure 1.

HemN binds two SAM molecules (PDB 1OLT).13 (A) Active site of HemN that binds (S)-SAM (∼60% occupancy). (B) Active site of HemN that binds (R)-SAM (∼40% occupancy). The distances from the SAM1 C5′ atom to the sulfur and methyl carbon of SAM2 are shown in brown and blue, respectively.

Figure 2.

Catalytic mechanism of HemN. (A) Common pathway of HemN-like enzymes in the generation of a SAM-based methylene radical intermediate 1. (B) Mechanism of HemN-catalyzed oxidative decarboxylation reaction. (C) Working hypothesis for the detailed HemN catalysis. The [4Fe-4S] cluster is represented as a cube, and the porphyrinogen ring is represented as a purple diamond. P and V represent propionate and vinyl moieties, respectively. 2-I, 2-II, 2-III, and 2-IV are coproporphyrinogen III (substrate), mono-decarboxylated product (harderoporphyrinogen), protoporphyrinogen IX (di-decarboxylated product), and the SAM adduct of the mono-decarboxylated product, respectively.

The Anaerobic CPO HemN

Catalytic Mechanism

The in vitro CPO activity of HemN, which catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of the two propionate chains of coproporphyrinogen III, was revealed by the seminal work of Layer et al. in 2002.20 Later the crystal structure of HemN was solved at 2.07 Å resolution, which represents the first structure of the radical SAM superfamily (PDB 1OLT).21,22 In the structure, the [4Fe-4S] cluster is bound by three cysteine residues within the characteristic CxxxCxxC motif found in most radical SAM enzymes. One SAM molecule (SAM1) binds the unique Fe of [4Fe-4S] cluster via its amino nitrogen and carboxylate oxygen, and a second SAM (SAM2) is found adjacent to the [4Fe-4S]-bound SAM1 (Figure 1).21,22 Mutation of the second SAM binding sites completely abolished enzyme activity, demonstrating the essential role of the second SAM in catalysis.23

The HemN-catalyzed decarboxylation occurs in a sequential manner, which first produces the mono-decarboxylated product and then the di-decarboxylated product protoporphyrinogen IX.24 Two SAM molecules were consumed in producing one molecule of protoporphyrinogen IX.23 Hence, it had been generally accepted for a long time that the dAdo radical directly abstracts a hydrogen atom from the propionate chain of coproporphyrinogen III and each SAM is responsible for the decarboxylation of one propionate chain.15,16 Although theoretically feasible, the proposed mechanism would involve significant movement of the two SAM molecules in the enzyme active site, and this appears to be inconsistent with the extremely high reactivity of dAdo radical, which needs to be finely controlled in the active site to achieve a specific catalytic outcome.25,26

Indeed, recent biochemical studies have established a revised mechanism, which involves a key SAM-based methylene radical intermediate 1 in the reaction.27 In the catalysis of HemN, SAM1 is reductively cleaved to generate a dAdo radical, which abstracts a hydrogen from the methyl group of SAM2 to produce 1 (Figure 2A). 1 then abstracts a hydrogen from the propionate β-carbon of coproporphyrinogen III to produce a vinyl chain (Figure 2B). The product dAdoH and l-Met generated from SAM1 is then replaced by a new SAM molecule (SAM3), and the resulting mono-decarboxylated product is released and then re-enters into the enzyme active site with a flipped conformation, presenting the second propionate group to proximity of the SAM2 (Figure 2C). Cleavage of SAM3 leads to the second run of hydrogen transfer and production of the second vinyl group (Figure 2C). The key evidence for the presence of 1 in the reaction is the trapping of a SAM adduct by the mono-decarboxylated product (Figure 2C).27 Such a SAM adduct is apparently a shunt product of the aberrant pathway in which the mono-decarboxylated product generated from the first round of reaction fails to flip its conformation on time (Figure 2C). Because multiple reaction turnovers were observed in the absence of external reductant, it is likely that upon decarboxylation the electron could go back to the [4Fe-4S] cluster to regenerate its active +1 state.27 A similar redox-neutral reaction has also been observed for other radical SAM enzymes.28−30

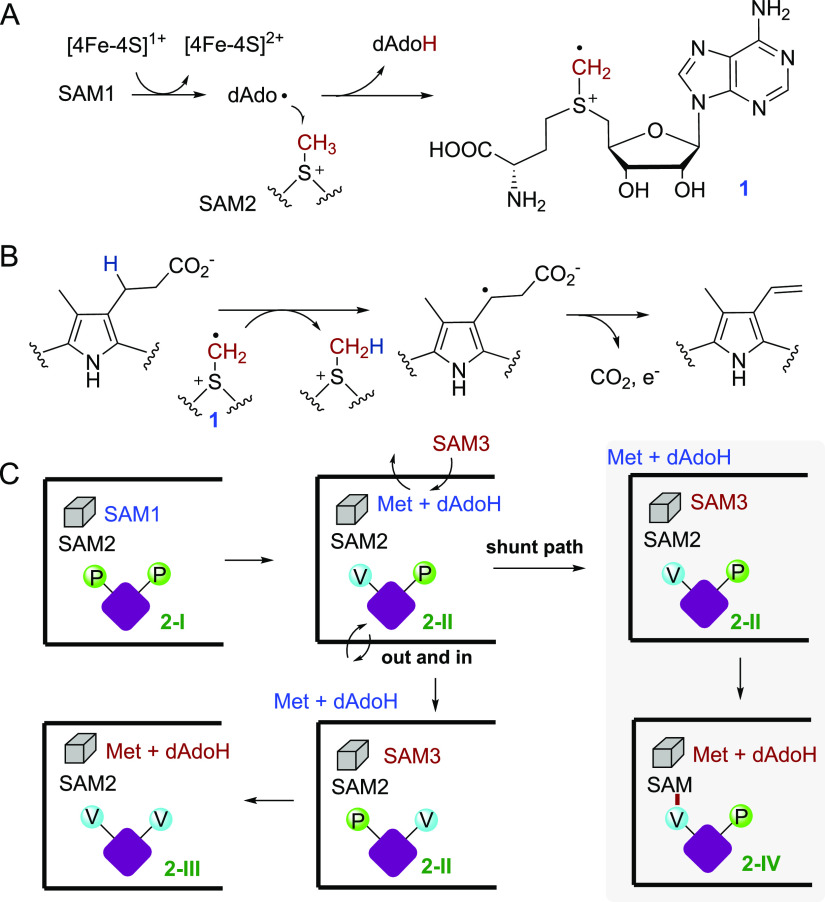

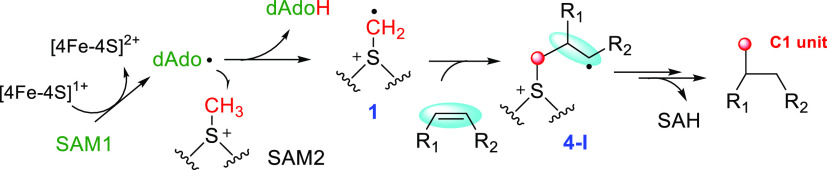

Radical SAM-Dependent Homolytic Substitution

The radical SAM-dependent homolytic substitution was first revealed by Nicolet and co-workers in the study of HydE, which catalyzed the dAdo radical-mediated homolytic substitution on a thioether substrate.31 Later Britt and co-workers showed that the dAdo radical generated in the HydE reaction attacks the cysteine S of the HydG product [FeII(Cys)(CO)2(CN)] to produce an adenosylated Fe(I) intermediate.32 The sulfur-based homolytic substitution has increasingly been recognized as an essential part of synthetic chemistry, which has been reported on various sulfur-containing compounds, including thioethers, thioesters, disulfides, sulfoxides, sulfinates, sulfonamides, and various S-based acetyl and ketals.33−39 As discussed above, in the HemN reaction, the dAdo produced from SAM1 abstracts a hydrogen from the methyl group of SAM2 to produce the key intermediate 1 (Figure 2A). However, in the crystal structure of HemN, it appears that, for both SAM diastereoisomers found in the active site, the C5′ of SAM1 is even closer to the sulfur atom than to the methyl group of SAM2 (Figure 1). This observation raises the tempting possibility that, besides abstracting a hydrogen from the SAM2 methyl group, the dAdo radical may also attack the sulfonium center of SAM2 to initiate a homolytic substitution reaction to produce a diadenosylated product and homoalanine (homoAla) (Figure 3). Indeed, di(5′-deoxyadenosyl)methylsulfonium (3-I) and homoAla were found in the HemN reaction mixture (Figure 3), and the yield of 3-I is slightly higher in the absence of the substrate coproporphyrinogen III.40 These findings demonstrate an unprecedented homolytic substitution reaction that occurs on a sulfonium center.

Figure 3.

HemN-catalyzed homolytic substitution (SH) reactions. The reaction occurs on SAM and the sulfoxide analogueue of SAM (SAHO) but not on the sulfone analogueue of SAM (SAHO2).

It has been shown previously that some radical SAM enzymes such as the tryptophan lyase NosL and the HemN-like enzyme NosN can cleave the sulfoxide and sulfone analogues of SAM (i.e., SAHO and SAHO2) to produce dAdoH.41 HemN is also able to cleave SAHO and SAHO2 to produce a dAdo radical.40 When the HemN reaction was performed with SAHO, the dAdo radical generated from SAHO1 attacked the sulfur center of SAHO2, leading to the production of di(5′-deoxyadenosyl)methylsulfoxide (3-II) (Figure 3). However, the expected di(5′-deoxyadenosyl)methylsulfone (3-III) was not found when the reaction was performed with SAHO2, suggesting that homolytic substitution cannot occur on a sulfone center (Figure 3), and this is supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculation.40 Characterization of these radical SAM-dependent homolytic substitutions expands the understanding of sulfur chemistry and highlights the diverse catalytic versatility of radical SAM enzymes. Although thus far this type of chemistry has only been explored on HemN, it is expected that such a reaction may also occur on many other HemN-like enzymes.

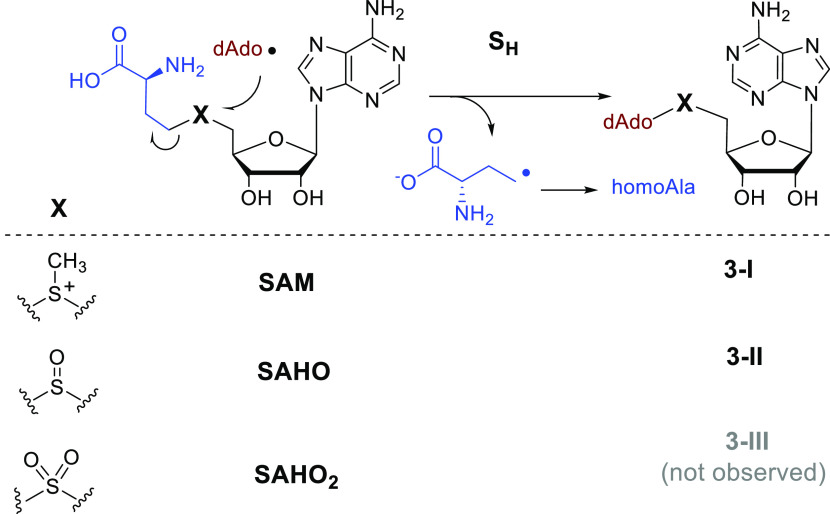

C1 Transfer by the Class C Radical SAM Methylases

The radical SAM-dependent methylase (RSM) can be grouped into several major classes according to the catalytic mechanism.42,43 Class A RSMs consist of the RNA methyltransferase RlmN and Cfr, which utilize a post-translationally methylated Cys in the enzyme active site as a methyl donor.44−47 Class B RSMs require a cobalamin factor to transfer the methyl group from SAM to the substrate.48−50 Although this process predominantly proceeds via radical chemistry, the polar mechanism is also present, as observed in the tryptophan methyltransferase TsrM.51−54 Class D RSM thus far has only one enzyme involved in methanopterin biosynthesis, which is distinct from other classes, as it appears to use methylenetetrahydrofolate instead of SAM as the methyl donor.55 Class E RSM consists of the noncanonic methylase NifB involved in nitrogenase cofactor assembly.56,57 Instead of methyl transfer, NifB transfers a carbide ion and couples two [4Fe-4S] clusters to form a [8Fe-9S-C] precursor called NifB-co.56,57 Class C RSMs, the topic of this Perspective, are homologous to HemN and likely share the same mechanism with HemN in generating the radical intermediate 1. However, instead of hydrogen abstraction to initiate an oxidative decarboxylation in HemN, 1 adds to an sp2 carbon to produce a radical adduct intermediate 4-I (Figure 4), which can be converted to various products, such as a methyl group, a cyclopropane moiety, a methoxy moiety, etc. In all of these cases, the reaction transfers a C1 unit to the substrate and releases an S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) as a coproduct (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Common paradigm in the catalysis of the class C RSMs. The sp2-hydridized carbons are highlighted by a light blue ellipse.

Methyltransferases

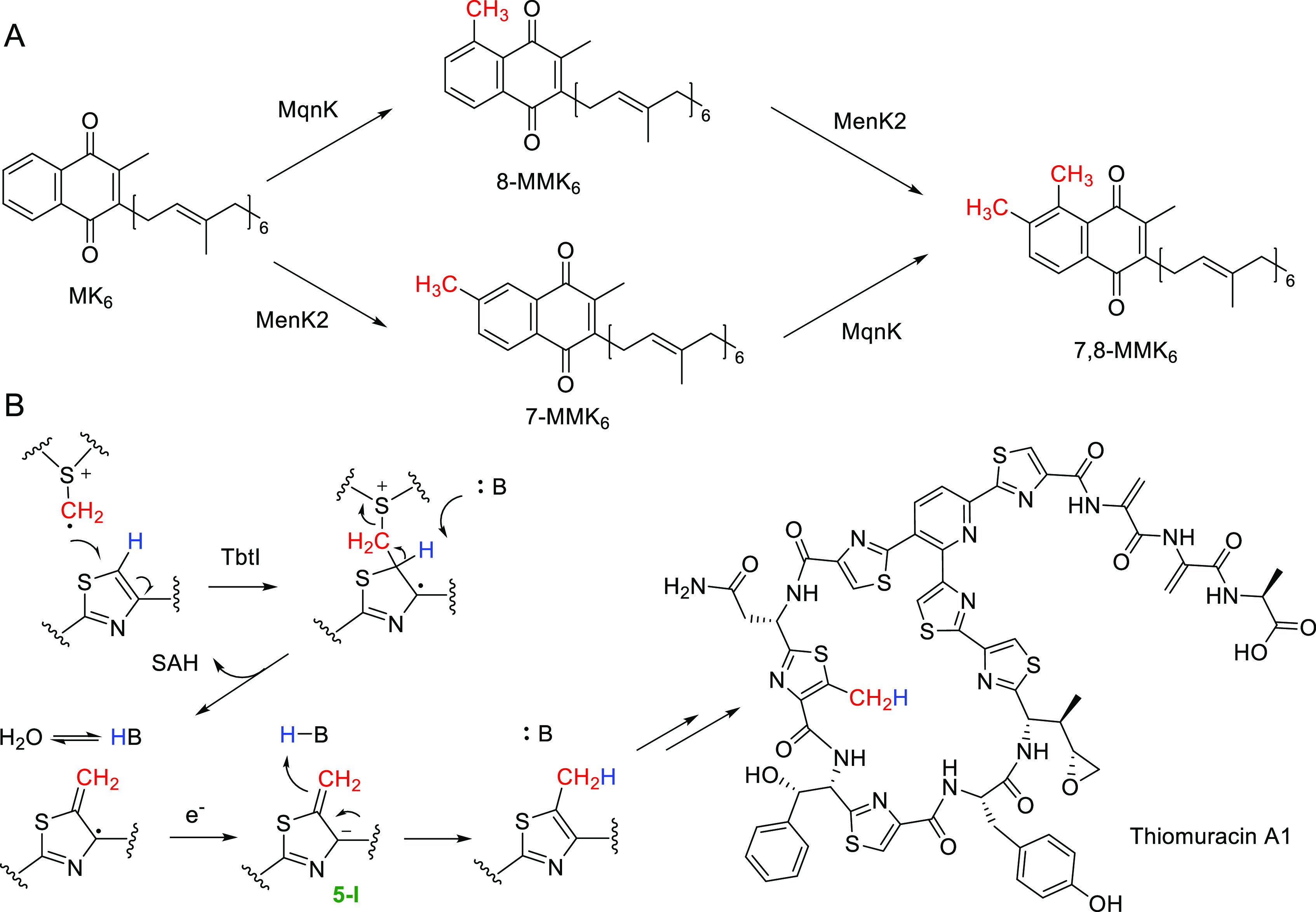

Menaquinone (MK) is an important component of the electron-transfer system in prokaryotes.58,59 Biosynthesis of MK involves either menaquinone (Men) pathways or futalosine (Mqn) pathways.60,61 MK is also found in methylated forms such as methyl-menaquinone (MMK) and dimethylmenaquinone (DMMK).58,59 In 2017, Hein et al. showed that the mqnK gene (which encodes a HemN-like protein) of the Mqn pathway in Wolinella succinogenes is required to convert MK6 to 8-MMK6 (the subscript number specifies the number of prenyl units in the isoprenoid side chain) (Figure 5A).62 They expressed a MqnK homologue MenK of the Men pathway and showed MenK converted MK6 to 8-MMK6in vitro. Later Hein et al. showed another MqnK homologue MenK2 catalyzes the methylation of MK6 on the C7 position to produce 7-MMK6.63 When the menK2 gene was introduced into W. succinogenes wide type strain, 7-MMK6, 8-MMK6, and 7,8-DMMK6 were all found from the cell membranes (Figure 5A). These results clearly demonstrate the methyltransferase activity of MenK and MenK2.

Figure 5.

Methylation reactions catalyzed by the class C RSMs. (A) Consecutive methylation of menaquinone. (B) Thiazole methylation by TbtI in the biosynthesis of thiomuracin A1.

The thiopeptide antibiotic thiomuracin A1 contains a 5-methylthiazole ring. In 2017, Mahanta et al. reported in vitro reconstitution of a HemN-like enzyme TbtI involved in thiomuracin biosynthesis, showing that this enzyme catalyzes thiazole C5-methylation on a linear hexazole-bearing intermediate of the precursor peptide TbtA (Figure 5B).64 Instead, thiomuracin GZ, an analogue of thiomuracin A1 that lacks the thiazole C5-methyl group, is not the substrate of TbtI. The mechanism of TbtI was later investigated in detail by isotopic labeling studies.65 Briefly, when deuterium-labeled SAM (i.e., CD3-SAM) was used in the reaction, the majority of methylated products contained a CHD2 group. When the reaction was performed with CD3-SAM in D2O, the major product again contained a CHD2 group. When the reaction was performed using CD3-SAM in D2O with the deuterium-labeled substrate at the thiazole C5, the major product then contained a CD3 group. These results revealed the deprotonation of the Cβ position by a solvent-exchangeable protein residue during the catalysis (Figure 5B). This hydrogen can be transferred back to the methylated product likely via an anion intermediate 5-1 (Figure 5B).

Besides the in vitro characterized examples, many HemN-like enzymes were also reported to perform methyl transfer reactions, such as TpdI, TpdL, and TpdU in GE2270 biosynthesis66 and Blm-Orf8,67 Tlm-Orf11,68 and Zbm-Orf2669 in the biosynthesis of bleomycin family antibiotics. It is also noteworthy that although some HemN-like enzymes such as YtkT and NosN are not methyltransferase per se, methylated products were also observed in the reaction,70−73 which are the results of off-pathway promiscuous reaction of the intermediates.

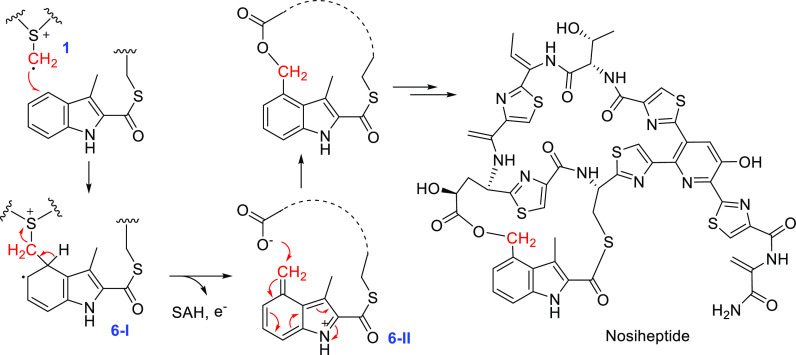

NosN

The HemN-like enzyme NosN catalyzes the indolyl side ring formation in nosiheptide biosynthesis, which introduces a methylene group into the indole C5 of the 2-methylindolic acid moiety and subsequently form the ether linkage with a glutamate residue.73,74 In the reaction, the SAM methylene radical 1 adds to the indole C5 indole to produce the SAM-adduct radical 6-I, which undergoes one-electron oxidation and SAH elimination to produce a cation intermediate 6-II. An intramolecular nucleophilic attack of 6-II by the Glu γ-carboxyl group leads to the formation of the indolyl ring (Figure 6). NosN exhibits remarkable substrate promiscuity, which acts on the indole ring attached to various moieties, including the peptide-bound Cys, N-acetylcysteamine (SNAC), pantetheine, and carrier protein NosJ.71,72,75,76 Moreover, different nucleoside adducts were observed in the NosN reaction.76−78 It appears that although the radical intermediate 6-I is oxidized in the normal reaction pathway, it actually can be either oxidized or reduced to result in different products in vitro (Figure 6).76,78 It is likely that the enzyme–substrate interaction finely tunes the redox chemistry of the intermediates in the native reaction process.

Figure 6.

NosN-mediated biosynthesis of the nosiheptide indolyl ring.

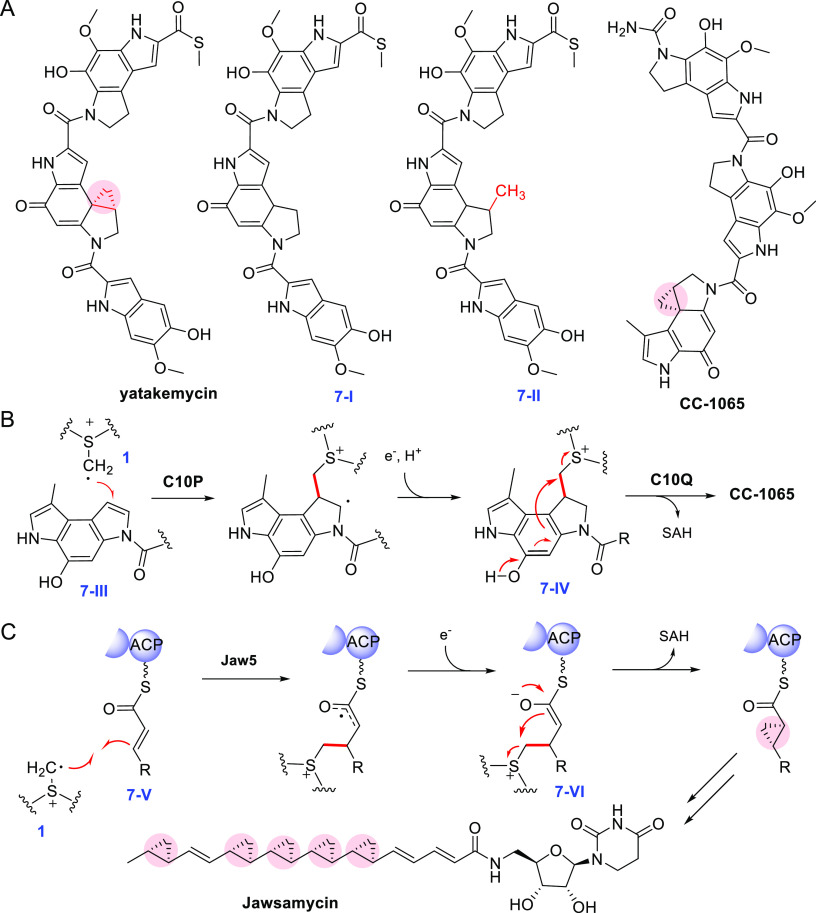

Cyclopropanases

The spirocyclopropylcyclohexadienone family natural products such as yatakemycin79 and CC-106580 contain multiple benzodipyrrole subunits connected by amide bonds, and one benzodipyrrole is further decorated with a cyclopropane ring. In 2012, Tang and co-workers showed the HemN-like enzyme YtkT is essential for the cyclopropane moiety of yatakemycin (YTM), as the ytkT-knockout mutant strain does not produce yatakemycin; instead, it produced a yatakemycin analogue 7-I that lacks the cyclopropane ring (Figure 7A).70In vitro assays showed that YtkT catalyzed the C-methylation of 7-I to produce a methylated analogue 7-II (Figure 7A); however, the cyclopropane moiety of yatakemycin was not produced in this analysis.70

Figure 7.

Cyclopropanation reactions catalyzed by the class C RSMs. (A) The structure of spirocyclopropylcyclohexadienone family compounds. 7-I is a metabolite produced by the ytkT-knockout mutant, and 7-II is produced in vitro in the YtkT assay. (B) Cyclopropanation in CC-1065 biosynthesis. (C) Cyclopropanation in jawsamycin biosynthesis.

Later, detailed in vivo and in vitro biosynthetic studies were reported for CC-1065. Similar to the study on ytkT, inactivation of c10p (which shares high sequence similarity with ytkT) abolished CC-1065 production and led to the production of a CC-1065 analogue 7-III that lacks the cyclopropane moiety (Figure 7B).81 Interestingly, the same analogue was also accumulated in the gene knockout mutant of c10Q, which is predicted to be an O-methyltransferase.81 These results indicated that C10P and C10Q may work collaboratively to produce the cyclopropane ring. Subsequent in vitro assays corroborated this hypothesis, showing that C10P and C10Q together were able to install the cyclopropane moiety of CC-1065 on the olefin precursor (Figure 7B).82 It was proposed that C10P catalyzes the radical SAM-dependent coupling reaction to produce the SAM adduct 7-IV and C10Q then catalyzes an intramolecular SN2 reaction to produce CC-1065 (Figure 7B).

Jawsamycin (also known as FR-900848) is a polyketide-nucleoside hybrid natural product containing multiple cyclopropane rings.83 The biosynthetic gene cluster of jawsamycin encodes a HemN-like protein Jaw5. The jaw5-knockout mutant loses the ability to produce jawsamycin. However, unlike the genetic knockout study of yatakemycin and CC-1065, the cyclopropane-deficient analogue was not observed.84 Later, a series of jawsamycin analogues with shortened chain length but lacking the cyclopropane moieties were isolated from a Streptomyces lividans strain expressing the jaw gene cluster, and these analogues are likely resulted from a shunt pathway skipping the cyclopropanation steps.85 It was proposed that, unlike YtkT and C10P, Jaw5 is solely responsible for cyclopropanation in jawsamycin biosynthesis (Figure 7C). This enzyme acts iteratively on the acyl carrier protein (ACP)-tethered α,β-unsaturated thioether substrate 7-V and involves the carbanion/enolate intermediate 7-VI, and the latter compound undergoes an intramolecular nucleophilic substitution to produce the cyclopropane ring (Figure 7C).

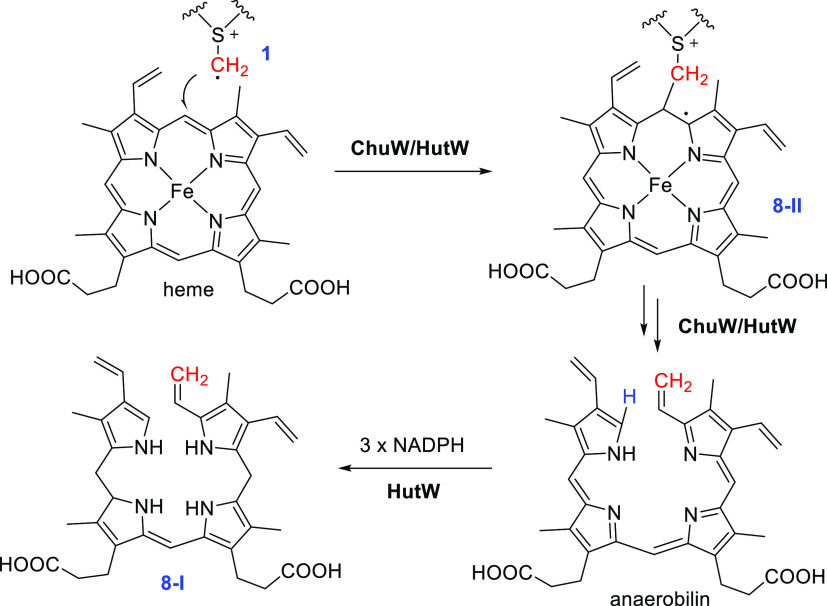

Heme Degradation by ChuW/HutW

In 2016, Lanzilotta and co-workers showed the HemN-like enzyme ChuW is responsible for anaerobic degradation of heme, producing a tetrapyrrole product named anaerobilin (Figure 8).86 This result suggests that ChuW catalyzes an ring-open methylation of heme to release iron. Like other class C RSMs, the reaction produced dAdoH and SAH in similar yields, and isotopic labeling studies showed that the newly introduced C1 group of anaerobilin is from the methyl group of SAM. More recently, the same group reported that HutW, a homologous protein of ChuW from Vibrio cholerae, also catalyzes the ring-opening methylation of heme.87 However, distinct from ChuW, HutW produced 8-I, a reduced form of anaerobilin. Moreover, unlike most radical SAM enzymes that require the flavodoxin and flavodoxin reductase to reduce the [4Fe-4S] cluster, the HutW-catalyzed reaction can proceed only with NADPH as the electron donor.87 ChuW/HutW can also act on the porphyrin substrate, suggesting the metal ion of heme is not necessary for reaction.87,88 Although the detailed mechanism for the ring-opening methylation of ChuW/HutW is currently unclear, it very likely involves the addition of the methylene radical 1 to the porphyrin ring to produce a porphyrin-based radical intermediate 8-II, which is subjected to a β-fragmentation to produce anaerobilin (Figure 8). Protonation of the pyrrole C2 should be an essential step before ring-opening, and isotopic labeling studies showed that this proton is derived from the solvent-exchangeable hydrogen.86

Figure 8.

Anaerobic degradation of heme by ChuW or HutW. The solvent-derived hydrogen atom is shown in blue.

Other HemN-like Proteins

HemW as a Heme Chaperone in Heme Transfer

HemW is a HemN-like enzyme widely distributed in prokaryotes. Biochemical analysis showed that HemW does not have CPO activity.89,90 Instead, HemW covalently binds heme in vitro, with a stoichiometry of one heme per protein. The addition of membrane fraction to the heme-binding HemW triggered the release of heme from HemW in vitro. Later Jahn and co-workers showed that HemW has a weak activity in SAM cleavage and the [4Fe-4S] cluster is essential for the HemW-catalyzed heme transfer but not for heme binding.90 The iron-storage protein bacterioferritins potentially serve as a heme donor for HemW, which can transfer heme to a heme-depleted, catalytically inactive nitrate reductase to restore its nitrate reductase activity.90 How heme is bound to HemW is not clear, and molecular dynamics analysis showed that heme likely interacts with the conserved HNXXYW motif in the mycobacterial HemW.91 Future studies are awaited to reveal the detailed function and mechanism of HemW.

RSAD1

Radical S-adenosylmethionine domain-containing 1 (RSAD1) is a HemN-like protein found in eukaryotes.92 In humans, the RSAD1 gene is located on chromosome 17 in the myeloperoxidase-chrondroadherin genomic interval (17q21.3-q24), which has been shown to be important for heart development, as deletion of the myeloperoxidase-chrondroadherin gene segment resulted in congenital heart disease in mice.93 Removing the RSAD1 gene in zebra fish embryos causes serious dysfunctional development, suggesting RSAD1 is required for survival.94 Recently, it has been shown that the gene expression level of RSAD1 increased apparently in the brain tissues from individuals diagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease.95 Besides the important roles of RSAD1 from animals, the members from plants also appear to be functional, as has been revealed by transcriptomic analysis.96In vitro studies showed that RSAD1 firmly binds heme, as a typical heme absorption spectrum was clearly observed in the human RSAD1-heme complex,90 suggesting that RSAD1 likely has a heme chaperone activity similar to HemW.

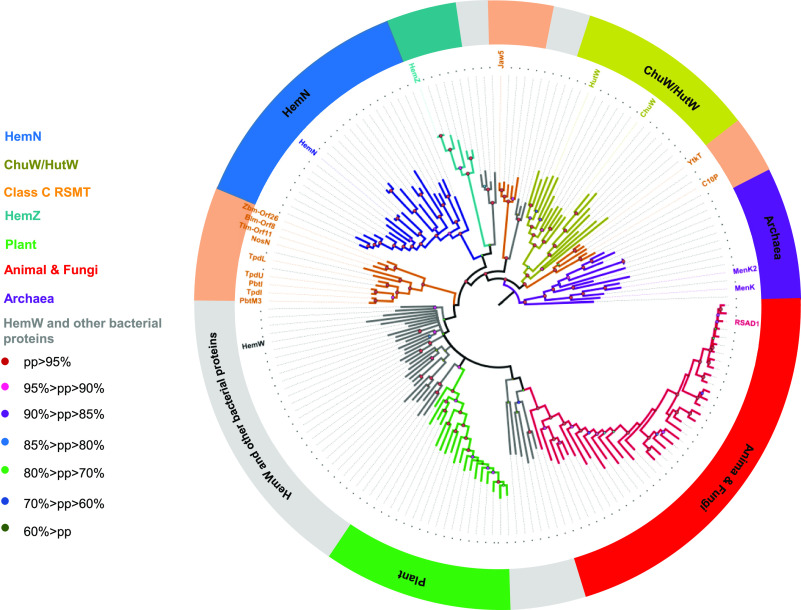

The Phylogeny of HemN-like Proteins

To investigate the phylogeny and functionally differentiate HemN-like proteins, we obtained 180 sequences from the NCBI databases. These proteins are from diverse kingdoms including Archaea, bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals, which are in almost all cases annotated as CPO proteins. A phylogenetic tree was then constructed by using Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) inference (Figure 9).97 This analysis revealed that the class C RSMs are distributed in diverse clades, and this is consistent with their diverse origins and functions (Figure 9). ChuW and HutW fall into two different clades, which together form a major clade neighboring to the clade containing YtkT and C10P. Other class C RSMs such as NosN and TbtI appear to be closer with HemW than HemN. In contrast, HemN falls into a distinct clade neighboring to a clade containing HemZ, and this observation appears to be consistent with the finding that hemZ is able to complement the hemN-deficient bacteria.98 HemW belongs to a polyphyletic clade that also contains RSAD1 from plants (Figure 9). This clade is neighboring to a polyphyletic clade containing RSAD1 from animals and fungi. Apparently, the eukaryotic RSAD1 has evolved from a bacterial precursor. These observations demonstrate the complex evolution process of RSAD1, and are consistent with the previous finding that RSAD1 is a heme chaperone similar to HemW. Besides the clades mentioned above, several subclades containing unknown bacterial sequences (Figure 9), which remain to be characterized by future studies.

Figure 9.

Bayesian MCMC phylogeny of Hem-like proteins. The major clades are shown in different colors, and the functionally characterized proteins are shown along the branches. Bayesian inferences of posterior probabilities (PPs) are indicated by the filled circles with different colors. It is worth noting that in some literature HemZ is annotated as a HemN-homologous protein,98,99 while it is sometimes also annotated as HemH and CpfC,2 and the latter enzymes are not radical SAM enzymes and not HemN-homologous. Caution should be taken for these different nomenclature systems. See the Supporting Information for the detailed information on the sequences discussed in this Perspective.

Conclusion

Recent years have witnessed a surge in the study of HemN-like proteins, which appear to be far more diverse than originally anticipated. For most HemN-like enzymes, the reaction likely shares a common paradigm by employing two SAM molecules in the catalysis, in which SAM1 is cleaved to generate a dAdo radical and SAM2 then undergoes the dAdo radical-mediated hydrogen abstraction from the methyl group to produce a key methylene radical 1 to initiate subsequent reactions. However, it is unclear whether such a reaction paradigm is universal to all the HemN-like proteins, as such a mechanism appears unrelated to the functions of other members such as HemW. Besides the highly diverse functions of prokaryotic enzymes, the functions of eukaryotic HemN-like proteins (i.e., RSAD1) also appear quite interesting, as they seem to play certain important physiological roles. Given the widespread occurrence and the diverse chemistry and function of HemN-like proteins, future studies on this growing family of proteins could be fruitful, which will not only reveal novel biochemistry but also likely contribute to our understanding of human physiology and health.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program (2018Y F A0900402), from National Natural Science Foundation of China (21822703 and 21921003), and from the funding of Innovative research team of high-level local universities in Shanghai and a key laboratory program of the Education Commission of Shanghai Municipality (ZDSYS14005).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsbiomedchemau.1c00058.

Accession numbers and the sequence similarities (BlastP with E. coli HemN) of the protein sequences used in the phylogenetic analysis (PDF)

Author Contributions

† J.C. and W.-Q.L. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Poulos T. L. Heme enzyme structure and function. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (7), 3919–62. 10.1021/cr400415k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey H. A.; Dailey T. A.; Gerdes S.; Jahn D.; Jahn M.; O’Brian M. R.; Warren M. J. Prokaryotic Heme Biosynthesis: Multiple Pathways to a Common Essential Product. Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017, 81 (1), e00048-16 10.1128/MMBR.00048-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann I. U.; Jahn M.; Jahn D. The biochemistry of heme biosynthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 474 (2), 238–51. 10.1016/j.abb.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga T.; Sano S. Coproporphyrinogen oxidase. I. Purification, properties, and activation by phospholipids. J. Biol. Chem. 1980, 255 (10), 4722–6. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)85555-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medlock A. E.; Dailey H. A. Human coproporphyrinogen oxidase is not a metalloprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271 (51), 32507–10. 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckau D.; Mahlitz E.; Sauerwald A.; Layer G.; Jahn D. Oxygen-dependent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase (HemF) from Escherichia coli is stimulated by manganese. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278 (47), 46625–31. 10.1074/jbc.M308553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. D.; Whitby F. G.; Warby C. A.; Labbe P.; Yang C.; Pflugrath J. W.; Ferrara J. D.; Robinson H.; Kushner J. P.; Hill C. P. Crystal structure of the oxygen-dependant coproporphyrinogen oxidase (Hem13p) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279 (37), 38960–8. 10.1074/jbc.M406050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. S.; Flachsova E.; Bodnarova M.; Demeler B.; Martasek P.; Raman C. S. Structural basis of hereditary coproporphyria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102 (40), 14232–7. 10.1073/pnas.0506557102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troup B.; Hungerer C.; Jahn D. Cloning and characterization of the Escherichia coli hemN gene encoding the oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177 (11), 3326–31. 10.1128/jb.177.11.3326-3331.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza I.; Dailey H. A. One ring to rule them all: trafficking of heme and heme synthesis intermediates in the metazoans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823 (9), 1617–32. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey H. A.; Gerdes S.; Dailey T. A.; Burch J. S.; Phillips J. D. Noncanonical coproporphyrin-dependent bacterial heme biosynthesis pathway that does not use protoporphyrin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112 (7), 2210–5. 10.1073/pnas.1416285112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brian M. R.; Thony-Meyer L. Biochemistry, regulation and genomics of haem biosynthesis in prokaryotes. Adv. Microb Physiol 2002, 46, 257–318. 10.1016/S0065-2911(02)46006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlt J. A.; Bouvier J. T.; Davidson D. B.; Imker H. J.; Sadkhin B.; Slater D. R.; Whalen K. L. Enzyme Function Initiative-Enzyme Similarity Tool (EFI-EST): A web tool for generating protein sequence similarity networks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1854 (8), 1019–37. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum M.; Chang H. Y.; Chuguransky S.; Grego T.; Kandasaamy S.; Mitchell A.; Nuka G.; Paysan-Lafosse T.; Qureshi M.; Raj S.; Richardson L.; Salazar G. A.; Williams L.; Bork P.; Bridge A.; Gough J.; Haft D. H.; Letunic I.; Marchler-Bauer A.; Mi H.; Natale D. A.; Necci M.; Orengo C. A.; Pandurangan A. P.; Rivoire C.; Sigrist C. J. A.; Sillitoe I.; Thanki N.; Thomas P. D.; Tosatto S. C. E.; Wu C. H.; Bateman A.; Finn R. D. The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49 (D1), D344–D354. 10.1093/nar/gkaa977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey P. A.; Hegeman A. D.; Ruzicka F. J. The radical SAM superfamily. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 43 (1), 63–88. 10.1080/10409230701829169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick J. B.; Duffus B. R.; Duschene K. S.; Shepard E. M. Radical S-adenosylmethionine enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (8), 4229–317. 10.1021/cr4004709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W. B.; Wu S.; Xu Y. F.; Yuan H.; Tang G. L. Recent advances in HemN-like radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Nat. Prod Rep 2020, 37 (1), 17–28. 10.1039/C9NP00032A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimberry M. A.; Mathew L.; Lanzilotta W. Making and breaking carbon-carbon bonds in class C radical SAM methyltransferases. J. Inorg. Biochem 2022, 226, 111636. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2021.111636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S.; Mandalapu D.; Wang S.; Zhang Q. Biosynthesis of cyclopropane in natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 10.1039/D1NP00065A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layer G.; Verfurth K.; Mahlitz E.; Jahn D. Oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen-III oxidase HemN from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277 (37), 34136–42. 10.1074/jbc.M205247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layer G.; Moser J.; Heinz D. W.; Jahn D.; Schubert W. D. Crystal structure of coproporphyrinogen III oxidase reveals cofactor geometry of Radical SAM enzymes. EMBO J. 2003, 22 (23), 6214–24. 10.1093/emboj/cdg598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layer G.; Kervio E.; Morlock G.; Heinz D. W.; Jahn D.; Retey J.; Schubert W. D. Structural and functional comparison of HemN to other radical SAM enzymes. Biol. Chem. 2005, 386 (10), 971–80. 10.1515/BC.2005.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layer G.; Grage K.; Teschner T.; Schunemann V.; Breckau D.; Masoumi A.; Jahn M.; Heathcote P.; Trautwein A. X.; Jahn D. Radical S-adenosylmethionine enzyme coproporphyrinogen III oxidase HemN: functional features of the [4Fe-4S] cluster and the two bound S-adenosyl-L-methionines. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280 (32), 29038–46. 10.1074/jbc.M501275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand K.; Noll C.; Schiebel H. M.; Kemken D.; Dulcks T.; Kalesse M.; Heinz D. W.; Layer G. The oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase HemN utilizes harderoporphyrinogen as a reaction intermediate during conversion of coproporphyrinogen III to protoporphyrinogen IX. Biol. Chem. 2010, 391 (1), 55–63. 10.1515/bc.2010.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vey J. L.; Drennan C. L. Structural Insights into Radical Generation by the Radical SAM Superfamily. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111 (4), 2487–2506. 10.1021/cr9002616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet Y. Structure-function relationships of radical SAM enzymes. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 337–350. 10.1038/s41929-020-0448-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X.; Mo T.; Liu W. Q.; Ding W.; Deng Z.; Zhang Q. Revisiting the Mechanism of the Anaerobic Coproporphyrinogen III Oxidase HemN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58 (19), 6235–6238. 10.1002/anie.201814708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruszczycky M. W.; Choi S. H.; Liu H. W. Stoichiometry of the redox neutral deamination and oxidative dehydrogenation reactions catalyzed by the radical SAM enzyme DesII. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (7), 2359–69. 10.1021/ja909451a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J.; Ji W.; Ma S.; Ji X.; Deng Z.; Ding W.; Zhang Q. Characterization and Mechanistic Study of the Radical SAM Enzyme ArsS Involved in Arsenosugar Biosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60 (14), 7570–7575. 10.1002/anie.202015177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S.; Chen H.; Li H.; Ji X.; Deng Z.; Ding W.; Zhang Q. Post-Translational Formation of Aminomalonate by a Promiscuous Peptide-Modifying Radical SAM Enzyme. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60 (36), 19957–19964. 10.1002/anie.202107192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohac R.; Amara P.; Benjdia A.; Martin L.; Ruffie P.; Favier A.; Berteau O.; Mouesca J. M.; Fontecilla-Camps J. C.; Nicolet Y. Carbon-sulfur bond-forming reaction catalysed by the radical SAM enzyme HydE. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8 (5), 491–500. 10.1038/nchem.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao L.; Pattenaude S. A.; Joshi S.; Begley T. P.; Rauchfuss T. B.; Britt R. D. Radical SAM Enzyme HydE Generates Adenosylated Fe(I) Intermediates En Route to the [FeFe]-Hydrogenase Catalytic H-Cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (24), 10841–10848. 10.1021/jacs.0c03802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crich D. Homolytic substitution at the sulfur atom as a tool for organic synthesis. Helv. Chim. Acta 2006, 89 (10), 2167–2182. 10.1002/hlca.200690204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denes F.; Schiesser C. H.; Renaud P. Thiols, thioethers, and related compounds as sources of C-centred radicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42 (19), 7900–7942. 10.1039/c3cs60143a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crich D.; Yao Q. W. Generation of Acyl Radicals From Thiolesters By Intramolecular Homolytic Substitution At Sulfur. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61 (10), 3566–3570. 10.1021/jo960115e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krenske E. H.; Pryor W. A.; Houk K. N. Mechanism of S(H)2 reactions of disulfides: frontside vs backside, stepwise vs concerted. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74 (15), 5356–60. 10.1021/jo900834m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith A. L. J.; Boate D. R. Stereochemistry of Intramolecular Homolytic Substitution at the Sulfur Atom of a Chiral Sulfoxide. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Comm 1986, (3), 189–190. 10.1039/c39860000189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coulomb J.; Certal V.; Fensterbank L.; Lacote E.; Malacria M. Formation of cyclic sulfinates and sulfinamides through homolytic substitution at the sulfur atom. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2006, 45 (4), 633–7. 10.1002/anie.200503369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulomb J.; Certal V.; Larraufie M. H.; Ollivier C.; Corbet J. P.; Mignani G.; Fensterbank L.; Lacote E.; Malacria M. Intramolecular homolytic substitution of sulfinates and sulfinamides. Chemistry 2009, 15 (39), 10225–32. 10.1002/chem.200900942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji W.; Ji X.; Zhang Q.; Mandalapu D.; Deng Z.; Ding W.; Sun P.; Zhang Q. Sulfonium-based Homolytic Substitution Observed for the Radical SAM Enzyme HemN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 8880–8884. 10.1002/anie.202000812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandalapu D.; Ji X.; Zhang Q. Reductive Cleavage of Sulfoxide and Sulfone by Two Radical S-Adenosyl-l-methionine Enzymes. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 36–39. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; van der Donk W. A.; Liu W. Radical-Mediated Enzymatic Methylation: A Tale of Two SAMS. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 555–64. 10.1021/ar200202c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauerle M. R.; Schwalm E. L.; Booker S. J. Mechanistic diversity of radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290 (7), 3995–4002. 10.1074/jbc.R114.607044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F.; Fujimori D. G. RNA methylation by radical SAM enzymes RlmN and Cfr proceeds via methylene transfer and hydride shift. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108 (10), 3930–4. 10.1073/pnas.1017781108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boal A. K.; Grove T. L.; McLaughlin M. I.; Yennawar N. H.; Booker S. J.; Rosenzweig A. C. Structural basis for methyl transfer by a radical SAM enzyme. Science 2011, 332 (6033), 1089–92. 10.1126/science.1205358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove T. L.; Benner J. S.; Radle M. I.; Ahlum J. H.; Landgraf B. J.; Krebs C.; Booker S. J. A radically different mechanism for S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. Science 2011, 332 (6029), 604–7. 10.1126/science.1200877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojkovic V.; Fujimori D. G. Radical SAM-Mediated Methylation of Ribosomal RNA. Methods Enzymol 2015, 560, 355–76. 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding W.; Li Q.; Jia Y.; Ji X.; Qianzhu H.; Zhang Q. Emerging Diversity of the Cobalamin-Dependent Methyltransferases Involving Radical-Based Mechanisms. Chembiochem 2016, 17 (13), 1191–7. 10.1002/cbic.201600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S.; Alkhalaf L. M.; de Los Santos E. L.; Challis G. L. Mechanistic insights into class B radical-S-adenosylmethionine methylases: ubiquitous tailoring enzymes in natural product biosynthesis. Curr. Opin Chem. Biol. 2016, 35, 73–79. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M. F. Cobalamin-Dependent C-Methyltransferases From Marine Microbes: Accessibility via Rhizobia Expression. Methods Enzymol 2018, 604, 259–286. 10.1016/bs.mie.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre S.; Guillot A.; Benjdia A.; Sandstrom C.; Langella P.; Berteau O. Thiostrepton tryptophan methyltransferase expands the chemistry of radical SAM enzymes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8 (12), 957–9. 10.1038/nchembio.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjdia A.; Pierre S.; Gherasim C.; Guillot A.; Carmona M.; Amara P.; Banerjee R.; Berteau O. The thiostrepton A tryptophan methyltransferase TsrM catalyses a cob(II)alamin-dependent methyl transfer reaction. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8377. 10.1038/ncomms9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz N. D.; Blaszczyk A. J.; McCarthy E. L.; Wang B.; Wang R. X.; Jones B. S.; Booker S. J. Enhanced Solubilization of Class B Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Methylases by Improved Cobalamin Uptake in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 2018, 57 (9), 1475–1490. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox H. L.; Chen P. Y.; Blaszczyk A. J.; Mukherjee A.; Grove T. L.; Schwalm E. L.; Wang B.; Drennan C. L.; Booker S. J. Structural basis for non-radical catalysis by TsrM, a radical SAM methylase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021, 17 (4), 485–491. 10.1038/s41589-020-00717-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen K. D.; Xu H.; White R. H. Identification of a unique radical S-adenosylmethionine methylase likely involved in methanopterin biosynthesis in Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196 (18), 3315–23. 10.1128/JB.01903-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Ribbe M. W. Maturation of nitrogenase cofactor-the role of a class E radical SAM methyltransferase NifB. Curr. Opin Chem. Biol. 2016, 31, 188–94. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay A. W.; Wiig J. A.; Lee C. C.; Hu Y. Identification and characterization of functional homologs of nitrogenase cofactor biosynthesis protein NifB from methanogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112 (48), 14829–33. 10.1073/pnas.1510409112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepp-Cothenet B.; van Lis R.; Atteia A.; Baymann F.; Capowiez L.; Ducluzeau A. L.; Duval S.; ten Brink F.; Russell M. J.; Nitschke W. On the universal core of bioenergetics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1827 (2), 79–93. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicka B.; Kruk J. Occurrence, biosynthesis and function of isoprenoid quinones. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1797 (9), 1587–605. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dairi T. Menaquinone biosyntheses in microorganisms. Methods Enzymol 2012, 515, 107–22. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394290-6.00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi X. Y.; Yao J. C.; Tang S. K.; Huang Y.; Li H. W.; Li W. J. The futalosine pathway played an important role in menaquinone biosynthesis during early prokaryote evolution. Genome Biol. Evol 2014, 6 (1), 149–60. 10.1093/gbe/evu007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein S.; Klimmek O.; Polly M.; Kern M.; Simon J. A class C radical S-adenosylmethionine methyltransferase synthesizes 8-methylmenaquinone. Mol. Microbiol. 2017, 104 (3), 449–462. 10.1111/mmi.13638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein S.; von Irmer J.; Gallei M.; Meusinger R.; Simon J. Two dedicated class C radical S-adenosylmethionine methyltransferases concertedly catalyse the synthesis of 7,8-dimethylmenaquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 2018, 1859 (4), 300–308. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahanta N.; Zhang Z.; Hudson G. A.; van der Donk W. A.; Mitchell D. A. Reconstitution and Substrate Specificity of the Radical S-Adenosyl-methionine Thiazole C-Methyltransferase in Thiomuracin Biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (12), 4310–4313. 10.1021/jacs.7b00693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Mahanta N.; Hudson G. A.; Mitchell D. A.; van der Donk W. A. Mechanism of a Class C Radical S-Adenosyl-l-methionine Thiazole Methyl Transferase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (51), 18623–18631. 10.1021/jacs.7b10203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R. P.; Leeds J. A.; Naegeli H. U.; Oberer L.; Memmert K.; Weber E.; LaMarche M. J.; Parker C. N.; Burrer N.; Esterow S.; Hein A. E.; Schmitt E. K.; Krastel P. Ribosomally synthesized thiopeptide antibiotics targeting elongation factor Tu. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (16), 5946–55. 10.1021/ja900488a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L.; Sánchez C.; Chen M.; Edwards D. J.; Shen B. The biosynthetic gene cluster for the antitumor drug bleomycin from Streptomyces verticillus ATCC15003 supporting functional interactions between nonribosomal peptide synthetases and a polyketide synthase. Chem. Biol. 2000, 7 (8), 623–42. 10.1016/S1074-5521(00)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao M.; Wang L.; Wendt-Pienkowski E.; George N. P.; Galm U.; Zhang G.; Coughlin J. M.; Shen B. The tallysomycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptoalloteichus hindustanus E465–94 ATCC 31158 unveiling new insights into the biosynthesis of the bleomycin family of antitumor antibiotics. Mol. Biosyst 2007, 3 (1), 60–74. 10.1039/B615284H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galm U.; Wendt-Pienkowski E.; Wang L.; George N. P.; Oh T. J.; Yi F.; Tao M.; Coughlin J. M.; Shen B. The biosynthetic gene cluster of zorbamycin, a member of the bleomycin family of antitumor antibiotics, from Streptomyces flavoviridis ATCC 21892. Mol. Biosyst 2009, 5 (1), 77–90. 10.1039/B814075H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W.; Xu H.; Li Y.; Zhang F.; Chen X. Y.; He Q. L.; Igarashi Y.; Tang G. L. Characterization of yatakemycin gene cluster revealing a radical S-adenosylmethionine dependent methyltransferase and highlighting spirocyclopropane biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (21), 8831–40. 10.1021/ja211098r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding W.; Li Y.; Zhao J.; Ji X.; Mo T.; Qianzhu H.; Tu T.; Deng Z.; Yu Y.; Chen F.; Zhang Q. The Catalytic Mechanism of the Class C Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Methyltransferase NosN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56 (14), 3857–3861. 10.1002/anie.201609948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y.; Du Y.; Wang S.; Zhou S.; Guo Y.; Liu W. Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Protein NosN Forms the Side Ring System of Nosiheptide by Functionalizing the Polythiazolyl Peptide S-Conjugated lndolic Moiety. Org. Lett. 2019, 21 (5), 1502–1505. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMattina J. W.; Wang B.; Badding E. D.; Gadsby L. K.; Grove T. L.; Booker S. J. NosN, a Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Methylase, Catalyzes Both C1 Transfer and Formation of the Ester Linkage of the Side-Ring System during the Biosynthesis of Nosiheptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 17438–17445. 10.1021/jacs.7b08492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; LaMattina J. W.; Badding E. D.; Gadsby L. K.; Grove T. L.; Booker S. J. Using Peptide Mimics to Study the Biosynthesis of the Side-Ring System of Nosiheptide. Methods Enzymol 2018, 606, 241–268. 10.1016/bs.mie.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding W.; Ji W.; Wu Y.; Wu R.; Liu W. Q.; Mo T.; Zhao J.; Ma X.; Zhang W.; Xu P.; Deng Z.; Tang B.; Yu Y.; Zhang Q. Biosynthesis of the nosiheptide indole side ring centers on a cryptic carrier protein NosJ. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8 (1), 437. 10.1038/s41467-017-00439-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding W.; Wu Y.; Ji X.; Qianzhu H.; Chen F.; Deng Z.; Yu Y.; Zhang Q. Nucleoside-linked shunt products in the reaction catalyzed by the class C radical S-adenosylmethionine methyltransferase NosN. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2017, 53, 5235–5238. 10.1039/C7CC02162C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X.; Mandalapu D.; Cheng J.; Ding W.; Zhang Q. Expanding the Chemistry of the Class C Radical SAM Methyltransferase NosN by Using an Allyl Analogue of SAM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 6601–6604. 10.1002/anie.201712224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; LaMattina J. W.; Marshall S. L.; Booker S. J. Capturing Intermediates in the Reaction Catalyzed by NosN, a Class C Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Methylase Involved in the Biosynthesis of the Nosiheptide Side-Ring System. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (14), 5788–5797. 10.1021/jacs.8b13157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tichenor M. S.; Boger D. L. Yatakemycin: total synthesis, DNA alkylation, and biological properties. Nat. Prod Rep 2008, 25 (2), 220–6. 10.1039/B705665F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanka L. J.; Dietz A.; Gerpheide S. A.; Kuentzel S. L.; Martin D. G. CC-1065 (NSC-298223), a new antitumor antibiotic. Production, in vitro biological activity, microbiological assays and taxonomy of the producing microorganism. J. Antibiot (Tokyo) 1978, 31 (12), 1211–7. 10.7164/antibiotics.31.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.; Jian X. H.; Yuan H.; Jin W. B.; Yin Y.; Wang L. Y.; Zhao J.; Tang G. L. Unified Biosynthetic Origin of the Benzodipyrrole Subunits in CC-1065. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12 (6), 1603–1610. 10.1021/acschembio.7b00302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W. B.; Wu S.; Jian X. H.; Yuan H.; Tang G. L. A radical S-adenosyl-L-methionine enzyme and a methyltransferase catalyze cyclopropane formation in natural product biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 2771. 10.1038/s41467-018-05217-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M.; Ezaki M.; Hashimoto M.; Yamashita M.; Shigematsu N.; Okuhara M.; Kohsaka M.; Horikoshi K. A novel antifungal antibiotic, FR-900848. I. Production, isolation, physico-chemical and biological properties. J. Antibiot (Tokyo) 1990, 43 (7), 748–54. 10.7164/antibiotics.43.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsuka T.; Suzuki H.; Kariya R.; Seo T.; Minami A.; Oikawa H. Biosynthesis of the structurally unique polycyclopropanated polyketide-nucleoside hybrid jawsamycin (FR-900848). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53 (21), 5423–5426. 10.1002/anie.201402623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsuka T.; Suzuki H.; Minami A.; Oikawa H. Stepwise cyclopropanation on the polycyclopropanated polyketide formation in jawsamycin biosynthesis. Org. Biomol Chem. 2017, 15 (5), 1076–1079. 10.1039/C6OB02675C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMattina J. W.; Nix D. B.; Lanzilotta W. N. Radical new paradigm for heme degradation in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113 (43), 12138–12143. 10.1073/pnas.1603209113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimberry M.; Toma M. A.; Hines K. M.; Lanzilotta W. N. HutW from Vibrio cholerae Is an Anaerobic Heme-Degrading Enzyme with Unique Functional Properties. Biochemistry 2021, 60 (9), 699–710. 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew L. G.; Beattie N. R.; Pritchett C.; Lanzilotta W. N. New Insight into the Mechanism of Anaerobic Heme Degradation. Biochemistry 2019, 58 (46), 4641–4654. 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abicht H. K.; Martinez J.; Layer G.; Jahn D.; Solioz M. Lactococcus lactis HemW (HemN) is a haem-binding protein with a putative role in haem trafficking. Biochem. J. 2012, 442 (2), 335–43. 10.1042/BJ20111618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskamp V.; Karrie S.; Mingers T.; Barthels S.; Alberge F.; Magalon A.; Muller K.; Bill E.; Lubitz W.; Kleeberg K.; Schweyen P.; Broring M.; Jahn M.; Jahn D. The radical SAM protein HemW is a heme chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293 (7), 2558–2572. 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M.; Gupta Y.; Dwivedi P.; Kempaiah P.; Singh P. Mycobacterium lepromatosis MLPM_5000 is a potential heme chaperone protein HemW and mis-annotation of its orthologues in mycobacteria. Infect Genet Evol 2021, 94, 105015. 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.105015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf B. J.; McCarthy E. L.; Booker S. J. Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Enzymes in Human Health and Disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2016, 85, 485–514. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y. E.; Morishima M.; Pao A.; Wang D. Y.; Wen X. Y.; Baldini A.; Bradley A. A deficiency in the region homologous to human 17q21.33-q23.2 causes heart defects in mice. Genetics 2006, 173 (1), 297–307. 10.1534/genetics.105.054833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt R. D.Radical S-adenosyl methionine domain containing-1 (rsad1): A novel gene essential for cell survival during vertebrate development. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- York A.; Everhart A.; Vitek M. P.; Gottschalk K. W.; Colton C. A. Metabolism-Based Gene Differences in Neurons Expressing Hyperphosphorylated AT8- Positive (AT8+) Tau in Alzheimer’s Disease. ASN Neuro 2021, 13, 1–16. 10.1177/17590914211019443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrero R. A.; Guerrero F. D.; Moolhuijzen P.; Goolsby J. A.; Tidwell J.; Bellgard S. E.; Bellgard M. I. Shoot transcriptome of the giant reed, Arundo donax. Data Brief 2015, 3, 1–6. 10.1016/j.dib.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F.; Teslenko M.; van der Mark P.; Ayres D. L.; Darling A.; Hohna S.; Larget B.; Liu L.; Suchard M. A.; Huelsenbeck J. P. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61 (3), 539–42. 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homuth G.; Rompf A.; Schumann W.; Jahn D. Transcriptional control of Bacillus subtilis hemN and hemZ.. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181 (19), 5922–9. 10.1128/JB.181.19.5922-5929.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompf A.; Hungerer C.; Hoffmann T.; Lindenmeyer M.; Romling U.; Gross U.; Doss M. O.; Arai H.; Igarashi Y.; Jahn D. Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa hemF and hemN by the dual action of the redox response regulators Anr and Dnr. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 29 (4), 985–97. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.