Abstract

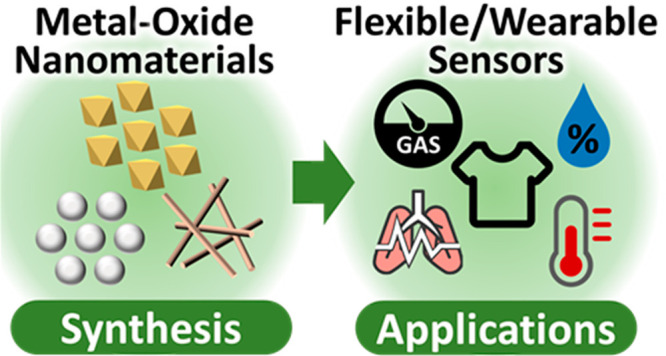

Metal-oxide nanomaterials (MONs) have gained considerable interest in the construction of flexible/wearable sensors due to their tunable band gap, low cost, large specific area, and ease of manufacturing. Furthermore, MONs are in high demand for applications, such as gas leakage alarms, environmental protection, health tracking, and smart devices integrated with another system. In this Review, we introduce a comprehensive investigation of factors to boost the sensitivity of MON-based sensors in environmental indicators and health monitoring. Finally, the challenges and perspectives of MON-based flexible/wearable sensors are considered.

Keywords: Metal oxide nanomaterials, flexible/stretchable/wearable sensors, gas sensors, electrochemical sensors, biomaterials sensors, health monitoring

1. Introduction

Recently, flexible electronics including flexible sensors,1−4 power sources,5 and conductors6,7 have been studied eagerly due to significant advantages in terms of reduced weight, flexibility, and durability to sustain multideformation (i.e., stretching, twisting, bending, and compression) compared with their rigid counterparts.8−10 During this vigorous development, flexible/wearable sensory systems have also been studied with various sensing materials including carbon materials,2,11−13 biomolecules,14,15 conductive polymers,2,16,17 and inorganic nanomaterials1,18,19 to improve their sensitivity, functionality, and stability via diverse strategies.

Among these materials, metal-oxide nanomaterials (MONs) are promising candidates in diverse areas of chemistry, materials science, physics, and biotechnology.20 The unique electronic structure determines the conductor, semiconductor, and insulator properties of nanomaterials. Transition metal ions typically possess unfilled d-shells, allowing for reactive electronic transitions, wide band gaps, superior electrical characteristics, and high dielectric constants.21 As a result, MONs have exceptional and adjustable optoelectronic, optical, electrical, thermal, magnetic, catalytic, mechanical, and photochemical properties. Furthermore, MONs have a wide range of applications: sensors, fuel cells, batteries, actuators, supercapacitors, optical devices, pyroelectrics, piezoelectrics, ferroelectrics, and random access memory due to their exceptional shape and size, which manifest distinctive physicochemical properties. Potential applications also exist due to the high density of surface sites and nanostructures.22

Especially, for sensing materials, MONs, mainly copper(II) oxide (CuO), copper(I) oxide (Cu2O), tin(II) oxide (SnO), tin(IV) oxide (SnO2), zinc oxide (ZnO), nickel oxide (NiO), indium oxide (In2O3), and tungsten oxide (WO3), are promising candidates that manifest high sensitivity, fast response/recovery (res/rec) time, excellent reproducibility and stability, and cost-effectiveness with simple fabrication processes.23−29 Conventional MON-based sensors are generally fabricated on rigid substrates due to their high manufacturing temperature, which increases energy consumption and manufacturing cost as well as imposes limitations in expanding applications.30−32 However, numerous studies on building MON-based sensors on flexible and stretchable substrates have been reported as a result of rapid advances in fabrication techniques in the past decade. As substrates for MON-based flexible sensors, polyimide (PI), polyethylene naphthalene (PEN), poly(ether sulfone) (PES), polyether ether ketone (PEEK), polycarbonate, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) are preferred. The thermal and chemical resistance, flexibility, and transparency of materials should be addressed for pragmatic sensing applications.33 Conductive features are essential to the operation of electrical devices, enabling the connection between various components.34

We present an overview of MON-based flexible/wearable sensors in this Review. First, we go through some of the most prevalent sensing materials. Then we discuss the diverse manufacturing technologies for fabricating flexible/wearable sensors. The applications of flexible/wearable sensors in the field of environmental indicators (e.g., gas, chemical, pH, and humidity sensors) and health monitoring (e.g., biomaterial, respiration, temperature, and mechanical sensors) are introduced to gain a comprehensive understanding of sensing efficiency via the design strategies and advanced characterization techniques. Finally, we discuss the challenges that flexible/wearable sensors are currently facing as well as their potential development in the coming years.

2. MONs as Sensing Materials

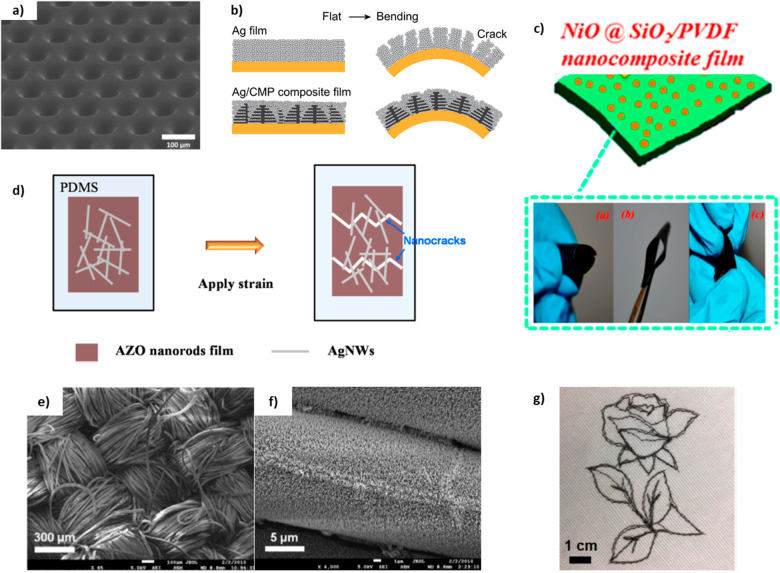

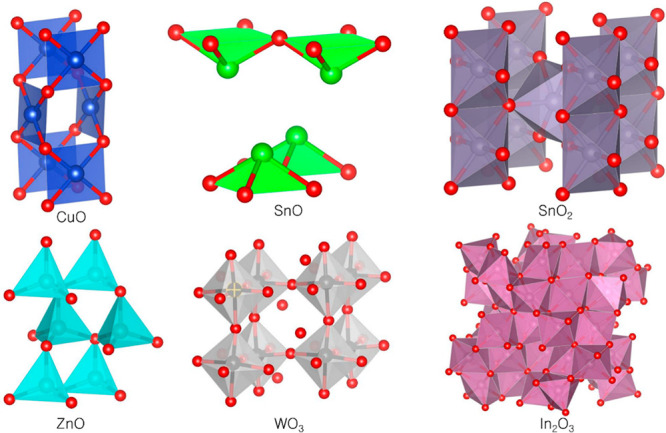

Various MONs in Figure 1 have been intensively employed in diverse applications, such as gas and chemical sensors,35−43 ultraviolet (UV) sensors,44−50 biosensors,51−57 humidity sensors,58−65 multifunction sensors,66 solar cells,67−70 batteries,71−73 photocatalysts,74−76 and thin-film transistors.77−80

Figure 1.

Crystal structures of MONs.

Copper oxides exist in two different states. CuO, also called cupric oxide with a narrow band gap energy of 1.2 eV, is a p-type semiconductor that is chemically stable, cost effective, and black in color.81 Cu2O, also called cuprous oxide, is another type of copper oxide with a reddish color and band gap energy of 2–2.17 eV.82 Additionally, CuO with a C2/c space group (a = 4.683 Å, b = 3.421 Å, and c = 5.129 Å) is attributed to a monoclinic crystal structure where each Cu species is bound to four oxygen atoms in a rectangular parallelogram.83 CuO is dominant for gas sensors, while Cu2O has received less attention in gas sensing applications than CuO.84,85 The key quality of p-type MONs, which are less conductive at elevated temperatures versus n-type MONs, is that they tend to replace lattice oxygen in the air. It is beneficial to maintain the metal-oxide stoichiometry for sensor sustainability. For instance, the shelf life of the carbon monoxide (CO) gas sensor is likely to be maintained and has extended long-term stability. However, the mobility of charge carriers is the most significant disadvantage and can impact the sensitivity, response, and recovery time. These drawbacks are likely to be mitigated by modifying the film morphology, electrode design, and doping materials.35,36,86,87

Thermal oxidation is a popular method for producing CuO-based sensors due to its superior quality, simplicity, and low cost, but it is time-consuming. Other strategies for fabricating CuO-based gas sensors have been reported to overcome this limitation, including hydrothermal,28 solvothermal,35 and thermal evaporation.36,86,87 Diverse nanostructures, including nanoparticles (NPs),35 nanowires (NWs),87 nanoplatelets,36 nanocubes (NCs), nanorods (NRs), nanoflowers (NFs), and nanotubes (NTs),86 have been exploited for CuO-based sensors that typically detect various reducing and oxidizing gases.

The bulk and surface-sensitive materials of the MON-based sensor can be distinguished. SnO2 is classified as a surface-sensitive material, despite the presence of bulk defects that affect conductivity. Variation in the electrical conductivity of sensors is caused by a dispersing conduction band and charge carrier concentration due to high charge mobility. Moreover, stannous oxide, a p-type SnO semiconductor with a P4/nmm space group symmetry (a = b = 3.8029 Å, c = 4.8382 Å), is attributed to a tetragonal structure that has a direct band gap of 2.5–3.0 eV.88 An n-type SnO2, also called stannic oxide or cassiterite with P42/mnm space group symmetry (a = b = 3.8029 Å), is ascribed to a rutile structure with a wide band gap energy (3.6 eV).89 Since SnO is more unstable above 270 °C, SnO gas sensors are typically made of thick porous SnO2 films with a large specific surface area. The electrons trapped by adsorbed species and band bending generate changes in conductivity when the material is heated. Due to high selectivity, fast response, low price, chemical stability, and large excitation binding energy, diverse SnO2 nanostructures have been developed for gas sensing and health monitoring via hydrothermal,90−93 inkjet printing,94 electrospinning,95,96 pulsed laser deposition,97 electrodeposition,98 and hot press.99

ZnO is an n-type semiconductor that possesses qualities such as cost-effectiveness, chemical stability, reproducibility, and nontoxic property. ZnO with a P63mc space group (a = 3.25 Å and c = 5.12 Å) is attributed to a hexagonal wurtzite structure100 for which each Zn is tetrahedrally bound to four O species that possess intrinsic defects like Zn interstitials and oxygen vacancies101 with a large band gap and high excitation binding energy. Due to the sizable electronegative difference (O = 3.44 and Zn = 1.65), Zn and O have strong ionic bonds. Polar surfaces possess distinct physicochemical properties versus nonpolar surfaces based on the rearrangement of negatively or positively charged surfaces.100 The O-polar surface exhibits a relatively electronic structure, while Zn-polar surfaces are more dynamic than nonpolar and O-polar surfaces due to the creation of energetic OH– ions.102 These properties are essential in the growth of ZnO nanomaterials, including crystallization, defects, and polarization. ZnO is also employed in diverse applications, including sensors, photocatalysis, solar cells, and three-dimensional (3D) surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy platform applications. ZnO, which can detect UV light9,45,97,100−106 and various gases, such as H2,24,107−109 H2S,25,110 O2,24 exhaled breath,111 and volatile organic compounds (VOCs),105 has been synthesized by various strategies, including thermal oxidation,24,106 wet-chemical processes,25,111 laser-assisted flow deposition,45 nonhydrolytic aminolysis,102 hydrothermal methods,103,104,107,110 sol–gel methods,105 electrospinning,108 solvent casting,109 and pulsed laser deposition.112

In2O3 is an n-type semiconductor with two types of crystalline structures: cubic (bixbyite) and rhombohedral (corundum). Furthermore, the band gap energy in both phases is 3 eV. In2O3 with an Ia3 nonsymmetric space group (a = 1.011 nm) is attributed to a cubic structure, while the R3c space group (a = 5.487 Å, b = 5.487 Å, and c = 5.781 Å) is designated as a rhombohedral structure. Nonsymmetric cubic In2O3, with high conductivity, is commonly utilized in microelectronics.113 Phase compositions, preparation conditions, and the indium electronic state of materials all influence the features of In2O3-based gas sensors. Several synthesis methods for developing gas, chemical, and healthcare sensors from In2O3 nanostructures have been exploited, including electrospinning,114,115 sputtering,116,117 sol–gel,37 hydrothermal,118 facile solution-based processing,26 and thermal annealing.37

Tungsten oxide (WO3) is an n-type semiconductor with a broad band gap energy (2.6–3.25 eV). WO3 has diverse crystal structures, including monoclinic, hexagonal, cubic, and orthorhombic phases. WO3 with a P21/c space group (a = 7.30 Å, b = 7.53 Å, and c = 7.69 Å) is designated as a monoclinic structure commonly explored for gas sensing. This is further composed of a WO6 octahedral bound to corner-sharing of oxygen atoms.119

Sputtering, hydrothermal, sol–gel, wet-chemical, thermal oxidation, and electrospinning methods are utilized to fabricate WO3 nanostructures with variable phases, sizes, porosity, and thickness.27,120−124 The preparation process and postannealing treatment have a significant impact on the performance characteristics of WO3-based sensors.125,126

3. Crucial Parameters for Sensors

Parameters such as sensitivity, selectivity, res/rec time, and limit of detection (LOD) are pivotal to assess the sensing efficiency of sensors. Sensor parameters can be optimized by various technological approaches.

3.1. Sensitivity

The signal due to detector and target analyte interaction is recognized during detection time. Sensitivity can be defined depending on sensor types as follows.

Chemo-resistive sensors:93

where Rg and Ra are resistance changes in gas and air, respectively.

Electric-resistive sensors:96

where Ig and Ia are the sensor current in gas and air, respectively.

Capacitive-type sensor:129

where Cini and Cfin are the capacitance at the initial (Tini) and the final (Tfin) temperatures, respectively.

The enhancement of sensitivity is described in detail throughout sections 2 and 3. Morphologies and microstructures play a pivotal role in enhancing sensitivity. MONs can be functionalized by doping and hybridization strategies. The presence of metallic dopants may reduce the activation energy of gas analytes by lowering operation temperature.130 Doping and hybridization with covalent and noncovalent interactions also enable tuning of morphologies, crystallites, and size, generating very active surface sites and significantly boosting the sensing efficiency.96,99,127,128,131 Additionally, the sensitivity can be considerably enhanced by the working conditions (light irradiation,128,132 analyte type127 and concentration,109,131 humidity,94,131 and temperature109,132) and fabrication (synthesis,133 substrate,109 dopant loading,128,131,132 and thickness134).

3.2. Selectivity

The selectivity of sensors can be understood as the capability of sensors to detect a target analyte in the mixture of analytes. Achieving a high selectivity is still a big challenge for MON-based sensors. The capability of detecting a single analyte distinctively among various analytes is commonly accomplished through temperature modulation1 or sensor arrays.20,135 Also, functionalized MONs with dopants and hybrid access a robust enhancement of sensor selectivity.

3.3. Stability

Stability is a vital key in the enlargement of sensors in the market and can be considered in two aspects. First, the active stability terms include the reproducibility of sensor features at least two years in the operating conditions. The second aspect of stability is the capacity to maintain sensitivity and selectivity. Korotcenkov and Cho specified that chemical mechanical impacts and environment such as humidity and temperature oscillation at an ambient atmosphere, and interference effect may contribute to instability.136 Almost no unified strategy improves the stability of MONs. Post treatments, such as annealing, calcination methods, and reduced operating temperature of sensitive materials, enhance the stability. The stability can also be improved by metal doping and MON hybridization.20

Improved engineering approaches, including drift compensation, selecting a correct analyte in the sensing system, adding filters, and temperature stabilization, also help solve stability issues.136

3.4. Functional Characterization Techniques

Diverse characterization methodologies have been exceptionally utilized to generate high-resolution photographs of materials’ nanostructure, along with the directly sensing process. For instance, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis is a valuable technique for examining the link between the crystal phase-sensing potential. Researchers can tune synthesis procedures on the surface of MONs using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). In addition, analytical instruments, including a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer, photoluminescence (PL) spectrometer, and Raman spectrometer, deliver multiscale information in the sensing process, enabling a deeper insight into the mechanism and sensing process. Furthermore, time-resolved spectroscopies, such as time-resolved mid-IR and PL, two-photon photoemission, transient absorption spectroscopy, and positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy are conducted to quantify the diffusion/transfer state of photoexcited carriers.137−139

The XRD pattern reveals the structure-sensing activity relations based on structural information such as shape, size, and crystallinity.44 This technique is promising to figure out phase transformations, orientations, and the impact of hybridization or doping on morphology and crystallinity. A cutting-edge technique, In situ XRD researches crystallization behavior by manipulating exterior conditions, enables a direct remark of phase composition and crystallization progression.140 Nanoscale structure, interface, and grain size are routinely detected with transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In various works, TEM study has been used to demonstrate the microstructural evolution and morphology modification of MONs during preparation methods such as hydrothermal treatment,28 wet chemical synthesis,141 single-step thermal decomposition,142 and sputtering.143 Electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) can suggest that charges transfer from the MONs surface to chemisorbed O2 elements due to the lack of the vacancy loss characteristic.144,145 In order to provide more complete results, EELS-equipped TEM is powerful and can reveal chemical configurations, lattice and crystal structure, oxidation state, and band gap.146 Due to the unaltered surface of MONs in ultrahigh vacuum, in situ STM research may offer a deeper knowledge of surface processing on sensitive materials during adsorption and reaction processes. Integration with atomic force microscopy (AFM) or tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS) technology clarifies sensing reaction mechanisms that offer the design and development of innovative materials for optoelectronic applications.147,148 X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) is influential in providing chemical states and compositions of elements. However, XPS does not exhibit the sensing process during a reaction between chemisorbed O2 species and target analytes. Near ambient pressure XPS (NAP-XPS) is a perfect alternating to investigate sensing mechanisms in diverse surfaces under the appearance of vapors and gases. The intermediates of radical O2 species, as well as the stoichiometry of MONs, also are recognized.20

4. MON-Based Flexible/Wearable Sensors

4.1. Gas Sensors

MON-based gas sensors usually detect gases through their resistance change caused by the interaction of exposed target gas and chemisorbed oxygen ions on the surface of the metal oxide. When the metal oxides are present in the ordinary atmosphere, oxygen molecules are absorbed on the surface and extract electrons consequently from the conduction band in the formation of the negatively charged ion. In this process, the metal oxide increases or decreases the conductivity depending on whether the metal oxide is n-type or p-type. In the case of n-type, the conductivity decreases because electron carriers are captured by oxygen. On the contrary, p-type metal oxides increase the conductivity as hole carriers are generated.

The ion form of oxygen includes O2–, O, and O2–, of which the dominant form depends on operating temperature, because reduction processes of the oxygen ions occur in stages below 100 °C, between 100 and 300 °C, and above 300 °C as shown by the following equations.

Furthermore, the chemical reaction between chemisorbed oxygen ions and the target gas also affects the number of charge carriers of the metal oxides. Correspondingly, the changed conductivity of MON allows the detection of the target gases. In the case of the exposure of the reducing gas, including H2S, NH3, CO, H2, acetaldehyde (CH3CHO), and ethanol (EtOH), oxygen ions reacting with the reducing gas, as shown in following equations, reinject electrons to the conduction band. In other words, the surface of metal oxides is reduced by the reducing gas.

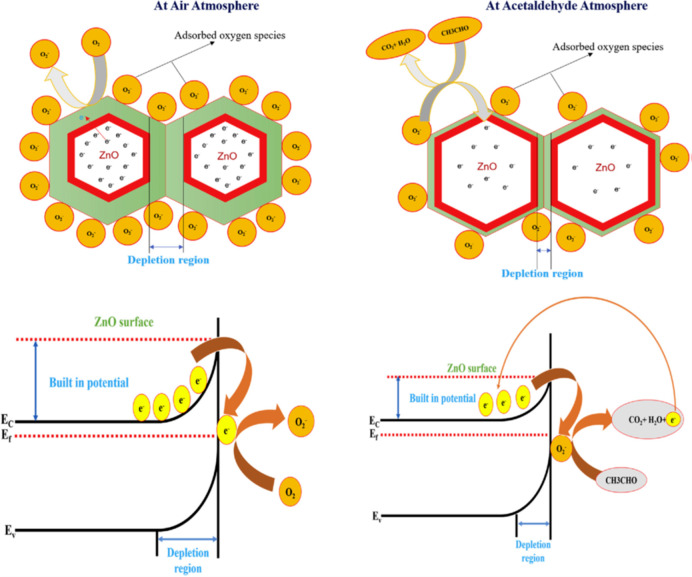

Consequently, the reinjection of electrons induces a change in the conductivity of the metal oxides by the decrease of hole carriers or the increase of electron carriers and permits precise sensing of target gases. Figure 2 shows a schematic of the sensing mechanism of ZnO NRs toward CH3CHO gas for an instance.105

Figure 2.

Schematic of the sensing mechanism of ZnO NRs toward CH3CHO gas. Reprinted from ref (105), with permission from Elsevier.

In contrast, when the metal oxides are exposed to an oxidizing gas such as NO2, NO, and O2, the adsorbed oxygen ions extract more electrons to react with the target gases and the extraction changes the conductivity of the metal oxide sensor as shown in the following equations.110

Generally, the sensing efficacy of gas sensors is improved at high temperatures of 100–400 °C due to the encouraged redox reaction of oxygen ions, thereby dramatically inducing the increase of energy consumption, cost, and overall size of the devices. Moreover, operation at high temperatures, which can cause microstructure transformation of the sensing MON resulting in low sensing efficacy, is harmful to flammable and explosive gas sensing applications and flexible substrates. For instance, a ZnO NR-based sensor exhibited an improved response to formaldehyde (HCHO) at 400 °C, which can damage flexible substrates (PET, PI, PDMS, PEN). To overcome these drawbacks, gas sensing applications have been considered to operate at room temperatures. Fortunately, due to the high reactivity of nanomaterials resulting from the high surface-to-volume ratio, single species MON-based flexible gas sensors can operate at low temperatures. However, there was still a limitation of the sensor’s performance at low temperatures. To overcome the limitation, several researchers approached the improvement of sensor performance at low temperature via metal-doping and hybridization methods described in section 5, “Strategies to Enhance Sensing Efficiency”.

4.1.1. Single Species MON-Based Flexible Gas Sensor

ZnO, SnO2, In2O3, WO2, TiO2, Fe2O3, MoO3, VO2, CuO, Co3O4, and NiO are common materials used for MON-based flexible gas sensors. Among those materials, ZnO is the most widely used material due to its wide band gap (3.3 eV), high conductivity, biocompatibility, good stability, and high sensitivity for both reducing and oxidizing gases. Several reports have focused on ZnO-nanomaterial-based flexible gas sensors for H2, H2S, O2, NH3, NO2, CO, CH3CHO, and EtOH in the recent decade.

Zheng et al. fabricated light-controlled transparent and flexible EtOH gas sensors based on a thin ZnO NP layer on an indium tin oxide (ITO)-PET substrate.149 They adjusted the sensor’s sensitivity by generating a high density of free carrier and oxygen ions under controlled UV irradiation. The sensor even operates well at a curvature angle of 90°. The ZnO NP-based gas sensor is also fabricated on a biodegradable and flexible CHP substrate.109 The ZnO nanoparticle layer on a CHP substrate displays an excellent sensitivity value of 69% at 180 °C. At an operation temperature of 150 °C (Table 1), the sensitivity of the ZnO sensor on the CHP substrate is 24% and 46% to 0.5% and 2% H2, better than that of the ZnO sensor on SiO2 substrate of only 10% and 24%, respectively.

Table 1. Sensing Efficiency of Diverse Materials.

| materials | method | substrate | target | temperature (°C) | LOD | response | res/rec (s) | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd NPs/ZnO NRs | sputtering | PI | H2 (1000 ppm) | RT | 0.2 ppm | 91c | 18.8/NA | (134) |

| Pd-SnO2 NPs | inkjet printing | PI | CO (50 ppm), dry air | 250 | NA | 2.1a | NA | (94) |

| CO (50 ppm), wet air | 1.5a | |||||||

| NO2 (5 ppm), dry air | 3.4b | |||||||

| NO2 (5 ppm), wet air | 2.5b | |||||||

| SnO2/SnS2 NTs | in situ sulfuration | PET | NH3 (100 ppm) | RT | NA | 2.48e | 21/110 | (96) |

| SnO2 NTs | electrospinning | NA | 1.25e | NA | ||||

| PVDF/SnO2 NPs/rGO | hot press | PVDF | H2 (1000 ppm) | RT | 500 ppb | 71.4c | 52/242 | (99) |

| ZnO NWs | hydrothermal growth | carbon microfiber | O2 (600 ppm) | 2 ppm | 13b | 10/12 | (24) | |

| H2 (500 ppm) | 4 ppm | 11.2a | 8/12 | |||||

| ZnO film | solution casting | chitosan/PVP (CHP) | H2 (2%) | 150 | NA | 46c | NA | (109) |

| 180 | 69c | NA | ||||||

| H2 (0.5%) | 150 | 24c | 1080/210 | |||||

| SiO2 | H2 (0.5%) | 150 | 10c | NA | ||||

| H2 (2%) | 150 | 24c | NA | |||||

| Cr-ZnO NPs | hydrothermal growth | Glass | NH3 (50 ppm), UV | RT | NA | 9c | 270/300 | (128) |

| Ce-ZnO NPs | hydrothermal growth | PET | NH3 (0.1–1 ppm), 97.5% RH | RT | NA | 32.66c | 155/NA | (131) |

| rGO/ZnO NRs | spin-cast | PDMS | NO2 (3000 ppb) | RT | 40 ppb | 55.4d | 16/65 | (127) |

| In2O3/rGO | DLW | PI | NO2 (1 ppm) | RT | NA | 31.6d | 252/798 | (133) |

| Pt NPs/In2O3 film | spray-coating | PI | EtOH | RT | 5.14 ppb | 90 (S/N) | 1/2 | (37) |

| Ni-WO3 NFs | hydrothermal growth | ceramic tube | CH3COCH3 (100 ppm), white light | RT | 2 ppm | 38c | 150/65 | (132) |

| Au-CeO2 NPs | hydrothermal growth | ceramic | H2S (50 ppm) | 100 | 94 ppb | 976c | 66/166 | (130) |

| Pd-CeO2 NPs | SO2F2 | 250 | 1.0 ppb | 153c | 63/773 | |||

| CeO2 NPs/g-C3N4 | screen-printing | PET | humidity | RT | 6573 | 959.5 pF/% RH (0–97% RH) | 12/NA | (172) |

| CeO2 NPs | hydrothermal growth | NA | NA | 33/NA | ||||

| PANI/CeO2 NPs | in-situ self-assembly | PI | NH3 (50 ppm) | RT | 16 ppb | 262.7c | NA/840 | (198) |

| PANI | NA | NA | 65.8c | NA/900 | ||||

| La-AlO3 film | sol–gel process | PI | temperature | 30–200 | NA | 2.7%°/C | NA | (129) |

| Al2O3 film | NA | 1.9%/°C | NA | |||||

| TiO2 NPs/2D-TiC | thermal decomposition | PET | EtOH (10–60 ppm) | RT | 10 ppb | 380f | 2.0/NA | (142) |

| 2D-TiC | NA | 155f | 3.2/NA | |||||

| PANI/Rh-SnO2 NTs | in situ polymerization | PET | NH3 (100 ppm) | RT | 500 ppb | 13.6b | NA | (95) |

(Ra/Rg).

(Rg/Ra).

([Ra – Rg]/Ra%).

([Rg – Ra]/Rg%).

(Ig/Ia).

(KPm).

ZnO NRs grown on cotton fabric are preferred for wearable gas sensors due to the intrinsically flexible and stretchable properties and the high surface-to-volume ratio of textile structures.24,105,150 Subbiah et al. demonstrated a wearable gas sensor sensing CH3CHO, NH3, and EtOH at room temperature (RT) by growing ZnO NRs on the surface of a carbon cellulosic fabric by sol–gel and sputter seed layer-coated sol–gel techniques.105 The gas sensor modified by the sol–gel method showed more sensitive responses to gases than the sensor modified by the sputtered seed layer-coated sol–gel technique. The sensor also showed UV-blocking performance due to a 3.37 eV band gap of ZnO. Lim et al. grew ZnO NRs on fabrics at RT using a scalable solution process and fabricated wearable H2 gas sensors.150 Also, the H2 sensing performance of the ZnO seed layer, ZnO NRs, and ZnO NRs with Pt catalyst was compared.

One-dimensional (1D) shaped nanomaterials such as NRs and NWs have preferred shapes for sensing materials due to their high aspect and surface-to-volume ratios. Therefore, several studies about flexible/wearable gas sensors based on ZnO 1D nanomaterials have been reported.24,25,104,107,150 Kwon et al. fabricated a flexible ZnO NR UV/gas dual-sensor through Ag NP templates. ZnO NRs were grown on Ag NP templates. It showed a better sensing performance than the ZnO NP seed layered template and a different sensing performance depending on the size of the Ag NPs because Ag NPs affect the surface depletion region.104

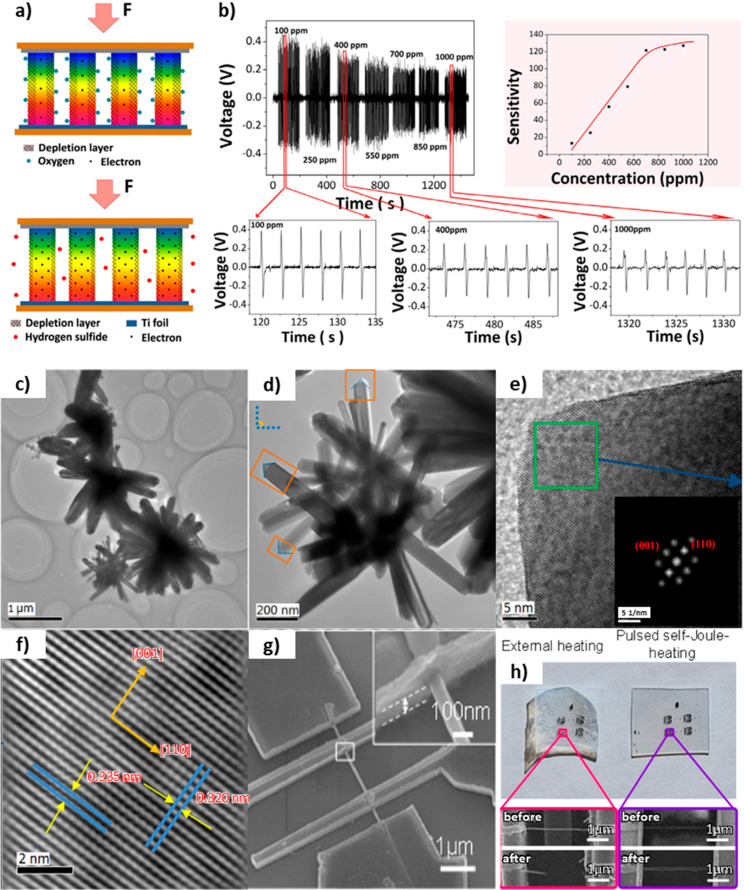

ZnO-based flexible/wearable gas sensors usually employ the conductometric method. However, some sensors employed a self-powered voltammetric sensing system using the piezoelectric characteristic of ZnO.25,131 Xue et al. demonstrated a self-powered active gas sensor based on the fact that absorption gas molecules could modify the density of the surface charge carrier, which largely influences the output of a piezoelectric nanogenerator as shown in Figure 3a.25 The sensor was fabricated using vertically grown ZnO NW arrays between the Al and Ti layers on polyimide substrates. The sensor showed a lower output voltage toward the higher concentration of H2S and water vapor, as shown in Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic of piezoelectric output and depletion layer at atmosphere and H2S environment. (b) Output voltage data and sensitivity of a piezoelectric-based ZnO NR gas sensor depending on the diverse concentrations of H2S gas. Copyright IOP Publishing Ltd. Reproduced from ref (25) with permission. (c) Lower and (d) higher magnification TEM photos of 3D hierarchical SnO2. (e) HRTEM photo of a single SnO2 nanorod. (f) Focused HRTEM photo taken from the rectangular region in (e). Adapted with permission from ref (93). Copyright 2015 Elsevier. (g) SEM photo and (h) photos of a SnO2 NWs-based sensor under external heating (left) and self-Joule-heating (right) conditions. Reproduced from ref (97). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

In2O3 is also the preferred semiconducting metal oxide material for its wide band gap (3.6 eV) and optical transparency. Therefore, In2O3-nanomaterial-based flexible gas sensors for NO2 and EtOH have been reported. Seetha et al. synthesized In2O3 nanocubes at a low temperature by a modified hydrothermal route and fabricated an EtOH sensor showing fast response and recovery times.151 The nanocubes obtained flexibility by constituting a composite with poly(vinyl alcohol). Wang et al. fabricated an In2O3 NW-based flexible transparent NO2 sensor operating at RT.152 To decrease the operating temperature of the sensor, visible light was illuminated on the sensor to reduce the activation energy. Furthermore, the ITO electrode and In2O3 NWs were employed for sensor transparency. The sensor showed highly selective responses for NO2 compared with H2S, NH3, trimethylamine, CH3COCH3, benzene, EtOH, toluene, and xylene.

SnO2 NPs were usually used to fabricate n-type MON-based gas sensors to detect n-butanol (n-BuOH) vapor,93 CO,94 NO2,94,97,153 and NH3.95 Wang et al. engineered 3D hierarchical SnO2-based gas sensors via a one-step and facile hydrothermal pathway.93 The hierarchical nanostructure produced a potentially efficient sensing efficiency with fast res/rec times and superior response to ppm n-BuOH. Gas diffusion and mass transport boosted by the 3D hierarchical nanostructure also boosted sensing performance, as shown in Figure 3c–f. Thermal control in spatial and time domains is preferred as a novel approach, reducing the operation energy to 102 pJ/s and enhancing the response to 100 ppb n-BuOH. The thermal management of a single SnO2 NW-based flexible NO2 sensor was reported.97 A pulsed self-Joule-heating of SnO2 NW enhanced sensitivity for NO2 as well as highly reduced energy consumption. The PEN substrate is destroyed by ordinary external heating at 523 K in Figure 3g,h. Conversely, the pulsed self-heating approach did not cause any damage to the substrate. Additionally, TiO2 has been broadly investigated for gas sensing due to its wide band gap (3.1 eV), low cost, low energy consumption, and unique electrical properties. Indeed, there have been reports of TiO2-nanomaterial-based sensors detecting EtOH142,154 and NO2.155 Dubourg et al. annealed the screen-printed TiO2 NPs on a flexible substrate via laser irradiation to fabricate a multifunctional sensor detecting UV and EtOH at RT.154 The morphology of the TiO2 film was adjusted by the laser irradiation process to enhance the sensor’s electrical properties.

4.2. Electrochemical Sensors

The semiconducting properties of MONs make them applicable to electrochemical sensors as well. pH, glucose, dopamine, humidity, heavy metals, cortisol, and urea were measured in an electrochemical way using MON-based flexible sensors. pH sensors are among the simplest electrochemical sensors, commonly measuring surface potential, which is shifted by a redox reaction between metal-oxide molecules on the surface and the hydrogen ions in the solution.29,156−163 Furthermore, researchers have measured pH levels by detecting the protonation of functionalizing groups on the surface26,159 or the change of capacitance of the interdigitated impedance metric sensor.28 In addition, biomaterials including glucose and dopamine were detected by attaching enzymes that induce catalysis to the modified surface of metal oxides. The three-electrode system is commonly employed to measure the electrochemical potential of the metal-oxide sensors because of its accuracy, but two-electrode systems and extended gate field-effect transistors (EGFET) are also used to fabricate sensing arrays or simplify the sensor.

4.2.1. pH Level Sensors

WO3 and IrOx were mainly exploited for flexible pH sensors based on MONs. In addition, ZnO, In2O3, indium–zinc oxide (IZO), ITO, and CuO were employed occasionally. The pH sensing mechanism of WO3 can be understood as the formation of HxWO3, namely, tungsten oxide bronze, via the redox reaction of WO3 according to the following equation.29,157

The redox reaction involves the double injection of protons (H+) and electrons (e–) for which the number is denoted as x. Moreover, the reaction mechanism was explained as utilizing a small polaron transition forming the W5+ site and Drude-like free electron scattering for amorphous films and crystalline films, respectively. According to both mechanisms, electron localization or delocalization into W atoms results in a shift in the peak potential. Therefore, the measured potential and the pH have a linear correlation according to Nernstain behavior.

A WO3-NP-based pH sensor showing a sensitivity of −56.7 ± 1.3 mV/pH in a pH range of 9–5 was fabricated via electrodeposition of WO3 NPs on metal electrodes on flexible substrates. The flexible sensor was also demonstrated as a conformable reference electrode on the curved surface of the solid electrolyte.157 In addition, WO3 NRs were directly grown on carbon fiber cloth to sense pH levels. The WO3-NR-modified carbon fiber cloth sensor showed a sensitivity of 41.38 mV/pH and a response time of 150 s over the pH range of 3–10.29

As mentioned, IrOx was also frequently exploited as materials for flexible pH sensors owing to its high conductivity, fast response, good stability, biocompatibility, and wide responsive range.156,158,160,161 The pH sensing mechanism of IrOx is understood as a shift of potential from the redox conversion reaction involving Ir4+ and Ir3+ as shown by the following equations.

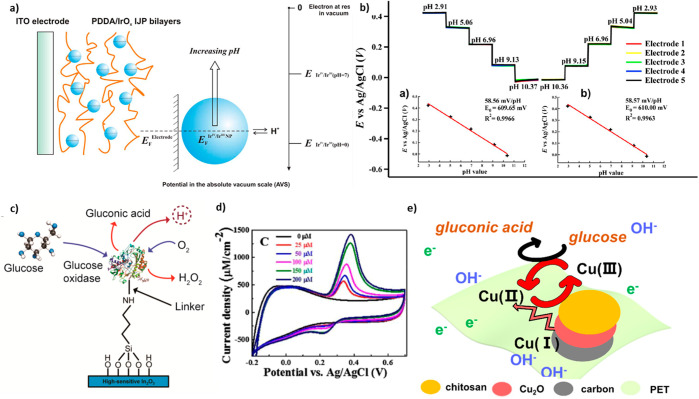

The pH level can be measured since the electrode’s potential is equalized with the Fermi level of the IrOx and NPs resulting from the redox reaction depending on the pH level, as shown in Figure 4a,b.

Figure 4.

(a) Schematic of the pH-dependent equilibrium potential of the IrOx NPs film. (b) Measurement of pH level via an IrOx NPs film. Reprinted from ref (156), with permission from Elsevier. (c) Schematic of enzymatic oxidation of d-glucose via attached glucose oxidase on In2O3. Reproduced from ref (26). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. (d) CV response of Fe2O3 NPs directly grown on carbon cloth and with different uric acid concentrations. Reprinted from ref (166), with permission from Elsevier. (e) Schematic of the circumstance of Cu(II)–Cu(III) in electrocatalysis oxidation. Reproduced with permission from ref (141). Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

4.2.2. Biomaterial Sensors

Additionally, MON-based flexible sensors detecting biomaterials including glucose, dopamine, cortisol, hydrogen peroxide, and urea were frequently reported recently. These materials were commonly detected via catalysis, which can be categorized into two ways which are enzyme reactions26,116,164 and enzyme-free electrocatalysis.141,165−167 On the other hand, electrochemical sensors detected a shift of potential due to the chemical combination of biomaterials and attached functionalizing chemical groups including antibodies.159,168

In the method using enzymatic catalysis, the concentration of biomaterials in a solution is estimated by detecting byproducts, including hydrogen ions from the reaction. Recently, In2O3-nanomaterial-based flexible glucose sensors employing the enzymatic oxidation of d-glucose with glucose oxidase have been reported.26,116 The concentration of d-glucose was estimated through the pH level determined by the concentration of hydrogen ions generated via enzymatic glucose oxidation in the following equations, as shown in Figure 4c.

To immobilize glucose oxidase on the surface, an amine-terminated (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane and glutaraldehyde linker was assembled to the In2O3 surface hydroxyl group.26

Fe2O3 NPs were also exploited for urea biosensors based on NiO and GO to absorb more enzyme molecules and act as an immobilization carrier.164 The sensor read the change of pH level of the microsurroundings of the sensing electrode affected byproducts from enzymatic catalysis as following equations.

Modifying with Fe2O3 NPs on the GO layer enhanced the sensitivity of the sensor.

On the other hand, in the case of the enzyme-free method, electrocatalytic oxidations of biomaterials including glucose,141,165 dopamine,166,167 and hydrogen peroxide169,170 are induced by nanomaterials including NiP0.1-SnOx,165 CuO,165 Cu2O,141 Pt,169,170 and Fe2O3.166 The circumstance between several oxidation states of metal atoms that occur through electrocatalysis affects the electrochemical sensor characteristics. Accordingly, the concentration of biomaterials was sensed by specific redox peaks in the CV curve, the open-circuit potential measurement, or the amperometric measurement. For example, Figure 4d exhibits specific peaks of Fe2O3 NPs resulting from the redox reaction of uric acid.

In the case of enzyme-free glucose sensors, metal compounds such as NiP0.1-SnOx, CuO, and Cu2O have been used as the electrocatalyst for inducing glucose oxidation.141,165 A shift of the electrochemical potential resulted from the reaction allowed sensitive detection of glucose molecules. For instance, the mechanism of electrocatalysis oxidation with Cu and Cu2O is known as the following equations.141,165

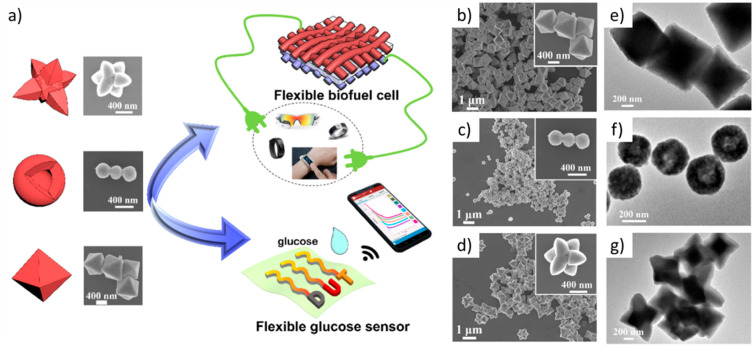

Owing to these oxidation reactions and circumstances of Cu(II)–Cu(III) (Figure 4e), Cu2O- and CuO-based glucose sensors showed broad oxidation peaks in their CV curves. The shape of Cu2O NPs affects the characteristics in the CV curves due to their different facets. Jiang et al. studied Cu2O-based wearable glucose sensors with various morphologies, such as octahedral, cuboctahedral, and extended hexapod nanostructures via a mild reduction synthesis, as displayed in Figure 5a. Figure 5b–g shows that only the cuboctahedral nanostructure has a specific hollow form with a smaller size while the other exhibited core-solid forms.141 The average sensitivity of morphologies is in this order: extended hexapod < octahedral < cuboctahedral. Consequently, the cuboctahedral nanostructure (Figure 5c) has (110)- and (100)-exposed facet engineering that provides higher interactions with glucose and electron-accelerated transfer, respectively. As a result, the cuboctahedral Cu2O-based sensor exhibits the highest selectivity and responsive signal.

Figure 5.

(a) Schematic of preparation of Cu2O glucose sensor. (b–d) SEM and (e–g) TEM images of octahedral, cuboctahedral, and extended hexapod Cu2O, respectively. Reproduced from ref (141). Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

4.2.3. Humidity Sensors

MONs including Ce/ZnO NPs,131 ZnO NWs,171 and CeO2 NPs combined with graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4),172 ZnO NRs modified with CeO2 NPs,173 ZnO NRs modified with SnO2 NPs,173 and CuO NPs28,174 have been widely used for electrochemical sensors detecting humidity recently.

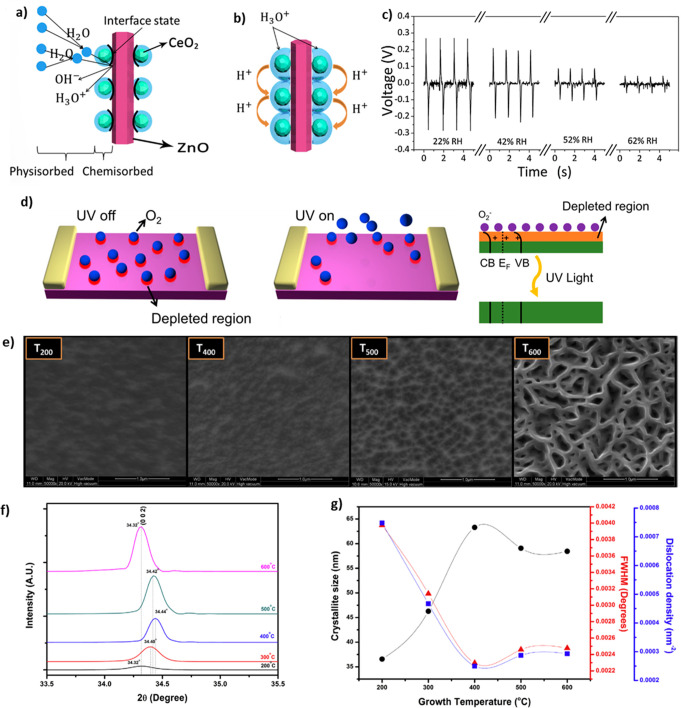

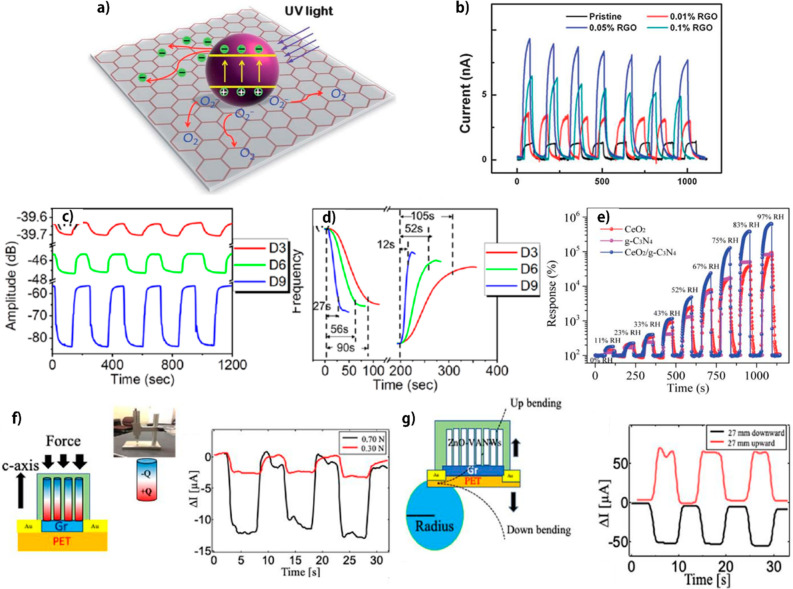

The piezoelectrical response of ZnO decreases in higher humidity; this characteristic was utilized to fabricate humidity sensors.131,173 D. Zhu drastically enhanced this characteristic by decorating CeO2 and SnO2 NPs on the surface of vertically grown ZnO NWs.173 The decorated ZnO NWs showed an almost doubled response compared to pure ZnO NWs. Basically, the mechanism of humidity sensors based on piezoelectric characteristics can be understood as a piezoelectric potential screening effect owing to the conductive H3O+ ions resulting from adsorbed water molecules which increase at higher relative humidity. Furthermore, decorating CeO2 and SnO2 NPs led to not only the adsorption of a greater amount of water molecules, as shown in Figure 6a, resulting in enhancement of the screening effect, but also freely moving H+ ions in the connected water layer in the highly humid environment, as shown in Figure 6b, further decreasing piezoelectric output. Consequently, the sensor showed a highly sensitive response, as shown in Figure 6c.

Figure 6.

(a,b) Schematics of a CeO2/ZnO NW at (a) low RH and (b) high RH. (c) Output voltage of piezoelectric MONs humidity sensor at different humidity levels. Reprinted from ref (173), with permission from Elsevier. (d) Schematic of UV sensing mechanism. Reproduced from ref (106). Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. (e) FE-SEM photos, (f) XRD patterns, and (g) crystallite size, density, and fwhm of (002)-indexed diffraction peak of ZnO thin films. Adapted with permission from ref (44). Copyright 2018 Elsevier.

4.3. Photodetectors

Photodetectors are also common applications for metal oxides such as SnO2,153 ZnO,104−106,150,175−182 TiO2,154 MoO3,181 Zn2SNO4,183 and Cu2O180 for their semiconducting properties. The UV sensing mechanism can be understood as the photoelectric phenomenon or the photodesorption of oxygen molecules adsorbed on the surface of metal oxides.

For example, in the case of n-type semiconducting metal oxides including SnO2, ZnO, TiO2, Zn2SNO4, and MoO3, conductivity is decreased due to the depletion region in the dark because oxygen molecules trap free electrons to be ionized and chemisorbed on the surface. When light with a higher photon energy than the band gap of the metal oxide is illuminated, the electron–hole pairs are generated photoelectrically. Accordingly, generated hole carriers recombine and discharge negatively charged adsorbed oxygen ions on the surface and increase the free-carrier concentration by reducing the depletion region, as shown in Figure 6d.106 In other words, the conductivity of the metal oxide increases via the photodesorption of oxygen, induced by the illumination of the light whose photon energy is higher than the band gap. The absorption and the desorption of the oxygen can be described by the following equations.

Nanomaterials are considered appropriate for these sensors due to their large surface-to-volume ratio since the trapping of electrons by oxygen occurs on the surface. Furthermore, several groups have studied the control of the shape of NPs to achieve larger surface areas177,179 and the relationship between geometric characteristics and performance of sensors.106,154 Shewale et al. explored the sensing performance of ZnO UV sensors fabricated at various growth temperatures.44 As shown in Figure 6e, the T200 (ZnO film grown at 200 °C) surface comprises unevenly sized grains and appears fuzzy, likely resulting from inhibition of grain growth due to a lack of thermal energy. However, the surface grains enlarge adequately at 400 °C and begin to degenerate fairly above 400 °C, resulting in a porous network-like surface structure. It is obvious that the (002) diffraction peak irregularly shifts to a low 2θ above 400 °C (Figure 6f). As confirmed in Figure 6g, the crystallinity of ZnO film is directly proportional to a growth temperature of up to 400 °C due to the mobility boost of atoms on the film surface. The elevated temperatures cause the film surface to re-evaporate, leading to a decrease in film thickness.112 The as-prepared ZnO-based sensor displayed the best UV response at 400 °C compared to other temperatures.

Two-dimensional (2D) semiconducting nanomaterials are desirable materials for flexible optoelectronics because their ultrathin nanosheet structure results in excellent flexibility and carrier mobility. However, most of them lack spectral selectivity in photodetection due to their narrow band gap, but orthorhombic structured molybdenum trioxide (α-MoO3) has an exclusive wide band gap (∼3.2 eV) which is appropriate to detect UV light. In fact, the flexible UV detector based on α-MoO3 showed transparency, high UV spectral selectivity, a high responsivity of 18 mAW–1 under mechanical deformations.181

4.4. Thermistors

Metal oxides, including NiO and doped Mn-spinel oxide, are widely employed to fabricate NTC thermistors because of their high thermal constant values (B-value). However, the high temperature (600–1200 °C) annealing process hindered progress to the fabrication of flexible metal oxides-based thermistors, but the low melting point of nanomaterials avail fabrication of metal oxides-based thermistors at relatively low temperature.

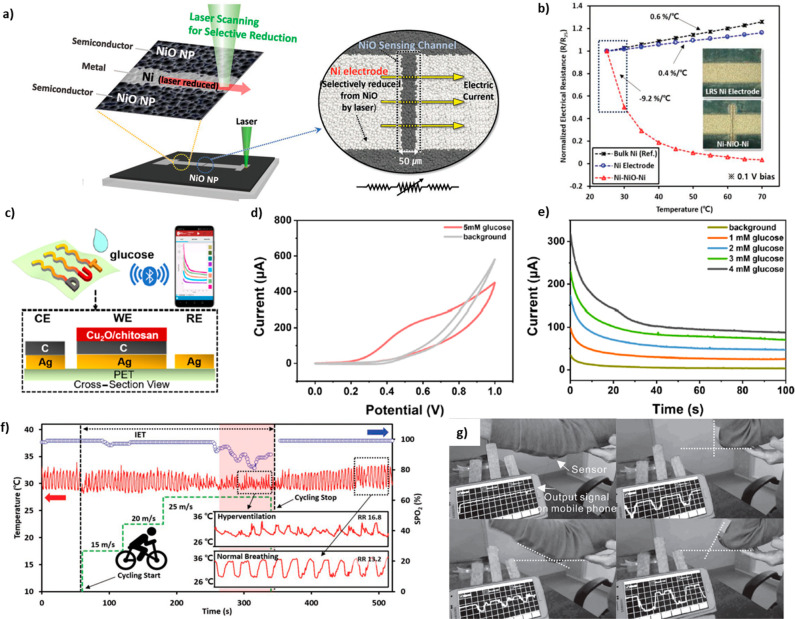

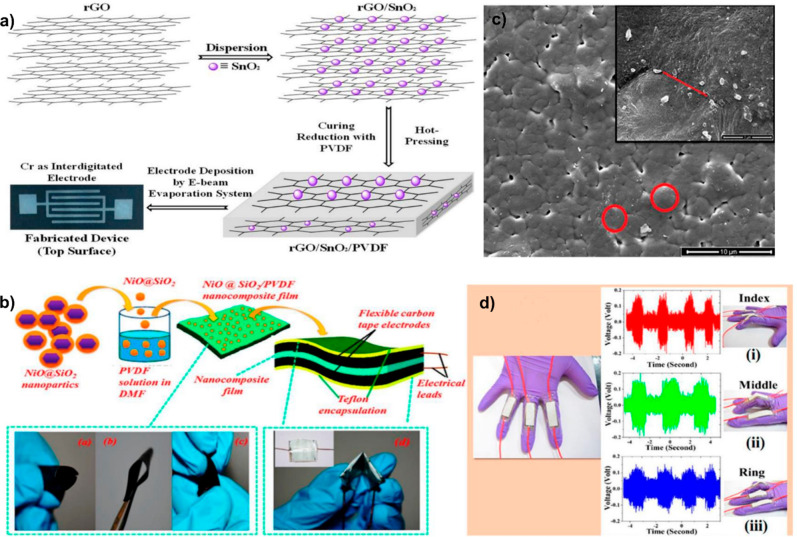

Huang et al. successfully fabricated a flexible thermistor array by inkjet-printing NiO NP ink on a polyimide substrate and annealing at 200 °C.184 The fabricated thermistor showed high B-values (∼4300 K) and good stability in the bending state. Furthermore, RT fabrication processes have been accomplished by laser sintering techniques.185 The wearable NTC thermistor was demonstrated with seamless monolithic integration of Ni and NiO by the selective NiO reduction technique based on laser process as shown in Figure 7a. The fabricated sensor showed excellent B-values (∼8162 K), as shown in Figure 7b, yet it is fabricated at RT.

Figure 7.

(a) Schematic of the selective NiO reduction technique based on laser process and the fabricated thermistor. (b) Temperature sensing properties of bulk Ni, reduced and sintered Ni NPs film, seamless NiO thermistor. Reprinted from ref (185) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License. (c) Schematic of a real-time glucose monitoring system based on Cu2O glucose sensor. (d) CV curves exhibiting oxidation peaks at 0.5–0.6 V and e) amperometric curves showing linear response in the range of 0–4 mM from the glucose monitoring system. Reproduced from ref (141). Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society. (f) Real-time monitoring of the respiration and progression of hyperventilation (red area) with the NiO NPs-based thermistor and the conventional SpO2 monitoring device. Reprinted from ref (185) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License. (g) Demonstration of the real-time wireless arm motion monitoring based on the ZnO/CNT/rGO/PET textile piezoelectric strain sensor. Reprinted with permission from ref (188). Copyright 2016 John Wiley and Sons.

Laser sintering processes of spinel Mn–Co–Ni oxide NPs have been studied for the flexible NTC thermistor. Moreover, liquid-phase sintering of Mn–Co–Ni oxide NPs was demonstrated by optimized laser pulse irradiation at RT. Crystal growth from the solid–liquid interface in the photoreaction of NPs resulted in densification, planarization of the sintered film, and highly sensitive performance.186 Moreover, the mechanical stability of the pulsed laser sintered Mn–Co–Ni oxide NP film was mechanically reinforced by fabrication of the Ag electrode embedded in the CMP structure.187 The reinforced sensor showed a resistance change of only 0.6% during 10,000 bending cycles.

4.5. Mechanical Sensors

MONs are used as piezoresistive materials,188,189 piezoelectric materials,190 and fillers enhancing piezoelectric characteristics in flexible/wearable sensor fabrication, detecting diverse mechanical deformations including bending, stretching, and compression.191 In particular, ZnO is the most common material used for mechanical sensors because of its magnificent piezoelectric and piezoresistive performance.

The microstructure of ZnO, which includes crystal morphology, crystal size, crystal orientation, aspect ratio, and crystalline density, strongly affects the piezoresistive properties. Therefore, the effect of the aspect ratio of the ZnO structure in the piezoresistive properties was investigated, and the optimized ZnO NW structure hydrothermally grown on the carbon hybrids on the PET textile was fabricated as a wearable bending sensor.188 Moreover, the sensing performance and mechanical properties of ZnO NPs-based piezoresistive sensors can be enhanced by combining them with another nanomaterial. The strain sensor composed of ZnO NPs/graphene nanoplatelets nanocomposite showed an extensive working range of up to 44% strain and perfect linearity (R2 = 0.999) with high sensitivity.189

MON fillers such as NiO, CuO, ZnO, and CoFe2O4 enhance the piezoelectric effect of PVDF by increasing the β phase fraction. Dutta et al. studied a tactile e-skin nanocomposite mechanosensor consisting of PVDF and NiO NPs coated by SiO2.191 To achieve a large interference surface between NiO and PVDF and resolve low percolation threshold problems, prevention of agglomeration of the particles was necessary. For this reason, conductive NiO NPs were coated with a nonconductive SiO2 nanolayer and dispersed well in the PVDF-based nanocomposite. The sensor was constructed as a nanogenerator, and its capacitance, impedance, and output voltage responded to compressive mechanical stimulation.

4.6. Wearable Sensor Applications

The highly advanced flexible electronics technique, that facilitates conformal attachment to human skin and enduring a deformation from human body motion, led to the emergence of wearable electronics. According to these trends, several researchers have introduced MON-based sensors flexible enough to be utilized as wearables. Furthermore, some researchers demonstrated wearable systems including MON-based flexible sensors.

Fabricating sensors on wearable substrates such as fabrics and fiber is an interesting approach to obtain enough flexibility to undergo mechanical deformation of the human body. ZnO NRs are the approved materials to be grown on fabric or fiber structures. ZnO NRs have been grown on cotton fabrics,150 Kevlar fiber,179 PET textile,188 and carbon fiber168 through the hydrothermal growth method150,168,188 and chemical vapor deposition179 to be used as gas (H2, EtOH, NO2), UV, and piezoelectric strain sensors. In addition, ZnO NPs,105 WO3 NPs,29 and α-Fe2O3 NPs166 were also used to fabricate gas and UV, pH, and dopamine sensors on fabrics. Meanwhile, spinning methods including blow-spinning66 and electrospinning are also good techniques to fabricate fabric-like structures consisting of nanofibers. Moreover, a colorimetric H2 sensing fiber was fabricated by striping an electrospun nanofiber containing PdO@ZnO NPs.108

However, the demonstrations of practical wearable applications using MON-based sensors on fabric and fiber structures are relatively insufficient. Li et al. introduced an E-textile gas sensor by yarning a reduced graphene oxide (rGO)/ZnO nanosheet (NS) hybrid fiber on fabric.192 The gas sensing textile was stitched on a shirt, and it detected NO2 successfully. A wireless textile strain sensor was demonstrated based on ZnO NRs and a carbon-nanomaterials coated PET textile. The ZnO-NR-based piezoelectric strain sensor, attached to the elbow of a shirt, transmitted the body motion data to a smartphone via ROIC, MCU, and Bluetooth module.188 Wang et al. demonstrated multimodal and monolithically integrated wearable sensor applications based on electrospun metals and metal oxides. A 3D-inorganic nanofiber network film (FN) including indium–gallium–zinc oxide (IGZO), CuO, ITO, and Cu was fabricated via blow-spinning. Blow-spun FN fulfilled various functions including switching, gas sensing, strain sensing, photodetection, thermistor, and pressure sensing due to the high adaptability in the material aspects of the fabrications process. The FN was also employed to fabricate a wearable strain sensing e-skin detecting finger motions and a multimodal wearable sensing device integrated into a band.

Contrary to textile-type MON-based sensors, film-type MON-based sensors have been actively studied to extend to wearable applications due to their simple structure and the availability of previous research allows easier approaches to stable and high performance devices. MON-based wearable sensor applications were commonly exploited for health-monitoring and detecting human physiological information, such as sweat,116,141,158,168 skin dryness,172 respiration,131,172,185 body temperature,129,185 and human motion,188,191 that can estimate and monitor human conditions via MON-based flexible/wearable sensors.

Sweat analysis is widely exploited to obtain physiological information from biomarkers in the composition of sweat. There has been literature that obtained physiological information from human sweat using MON-based electrochemical sensors. Cortisol concentration in human sweat samples was measured by cortisol-antibody modified ZnO NRs, integrated with the flexible carbon fibers.168 Furthermore, Jiang et al. developed a wireless real-time glucose monitoring system based on a wearable Cu2O NP sensor.141 The obtained real-time concentration data was transmitted to a smartphone via Bluetooth communication. (Figure 7c–e) The real-time glucose monitoring technology was expected to be developed for generalized healthcare applications, including preliminary medical diagnosis, chronic self-management. Also, wearable In2O3 nanoribbon transistor biosensor was developed.116 Chitosan, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and glucose oxidase were coated on the source and gated electrode of an In2O3 FET to detect glucose in body fluids. Therefore, the wearable sensor recognized the concentration of glucose in artificial sweat on an artificial eyeball and hand. Also, the sensor recognized real sweat collected before and after glucose beverage intake. The pH level of human sweat is also a useful parameter that can detect human activities. Zhou et al. demonstrated wireless real-time pH analysis with a smartphone and wearable epidermal electrochemical sensing device based on IrOx NWs during running.158 The mounted device on the arm skin of the runner recorded the pH level every 5 min, and the pH decreased during running and slightly increased during rest.

Also, perspiration can be tracked through the difference in chemical and thermal properties of inhaling and exhaling breath. The detection of human physiologic information based on humidity was revealed via a flexible wearable humidity sensing system based on cerium oxide/graphitic carbon nitride nanocomposite.172 The sensor attached to the human skin estimated different speeds of running states based on the measurement of the dryness of the skin. Also, long-time sitting monitoring was demonstrated through humidity detection via an attached sensor system on the cushion. Furthermore, a self-powered respiratory pattern sensing system based on a cycle and humidity sensor was developed and measured respiratory rate depending on the speed of the cycle. In addition, a self-powered wearable respiration monitoring system based on Ce-doped ZnO NPs flexible sensor detecting NH3 was demonstrated.131 The system included a Ce-doped ZnO-NP-based flexible triboelectric sensor, the sensor attached to the chest generates a voltage by the expansion and contraction of the chest during respiration, and NH3 contained in the exhaled breath supplied through the tube connected to the mouth affects the generated voltage. Therefore, the speed and the intensity of the respiration and the concentration of NH3 in the breath were measured. The respiratory pattern was also measured by detecting a slight temperature change of philtrum resulting from respiration via an attached epidermal physiological temperature sensor fabricated by laser sintering of NiO NPs.185 The sensor measured the respiratory rate and intensity and respiratory symptoms of hyperventilation due to the metabolic need resulting from intense physical activity, as shown in Figure 7f. Park et al. also introduced La-doped Al2O3-based wearable temperature sensors for body temperature monitoring systems.129 The capacitance of the La-doped Al2O3 nanofilm indicated temperature. Moreover, they established a wearable body temperature sensor device in the form of an armband, which could lead to a potential path for wearing bioelectronics.

Conventional mechanical sensors like strain gauges based on rigid metals were not suitable for health monitoring, including capturing the posture or motion of humans due to their limited range of strain and flexibility. However, flexible/wearable MON-based mechanical sensors suitable to monitor human motion were reported. Dutta et al. developed a tactile e-skin piezoelectric mechanosensor based on NiO@SiO2 NPs and a PVDF composite.191 The sensor was fabricated in typical piezoelectric energy harvester form and showed the output voltage and current depending on applied diverse mechanical stimulation such as pressure, stretching, and bending. Also, the capacitance and the impedance changed linearly according to the intensity of the static pressure. Measurements of voltage generation by bending motions of various fingers and mechanosensory array mapping distribution of the pressure were demonstrated. A wireless wearable textile strain sensor based on the piezoresistive characteristic of ZnO NWs was reported.188 The resistance of a ZnO/CNT/rGO/PET textile embedded in PDMS was measured by a readout integrated circuit, converted to digital data by the MCU, and subsequently transmitted to mobile phones wirelessly via a Bluetooth module. The wireless monitoring of the arm bending motion was exhibited through the sensing system, as shown in Figure 7g.

Also, there was a multifunctional wearable application for human–machine interfaces (HMIs).193 A sol–gel-on-polymer-processed IZO nanomembrane was exploited to achieve UV, temperature, and strain sensing ability and construct resistive random-access memory and FET for interfacing and switching circuits. Moreover, a serpentine pattern of a Au thin film electrode was employed to obtain stretchability. The IZO nanomembrane and Au electrode were encapsulated by the PI layer, and appropriate pattern designs were applied depending on the types of the sensors. The HMI not only recognized the motion of the arm and finger while attached on human skin, but also sensed humans touch via a temperature sensor while attached to a robot hand. Also, the HMI was able to deliver temperature via integrated microheaters.

5. Strategies to Enhance Sensing Efficiency

To improve the sensing performance of MON-based flexible sensors, several materials and modifying strategies such as low-dimensional carbon materials (graphene, rGO, and CNT), 2D materials (TiC, g-C3N4), PANI, metal sulfides, heterogeneous metal-oxide structure, and surface modification with noble metals have been studied. Modified MONs are of great interest due to their adjustable optoelectronic, optical, electrical, thermal, magnetic, catalytic, mechanical, and photochemical properties while also promoting long-term stability. These strategies also have been applied at once in a single sensor (Table 1).

5.1. Metal Doping

Doping is a powerful way of manipulating metal-oxide features such as oxygen vacancies, electrical conductivity, band gap, lattice parameters, and magnetic properties. The sensing ability is mostly determined by various carrier defects, mainly oxygen vacancies. Doping species, also called dopants, can tune the crystal structure and escalate defects and reaction sites. Furthermore, dopants could reduce the activation energy between the target analytes and the sensing material, boosting the sensor’s performance.128

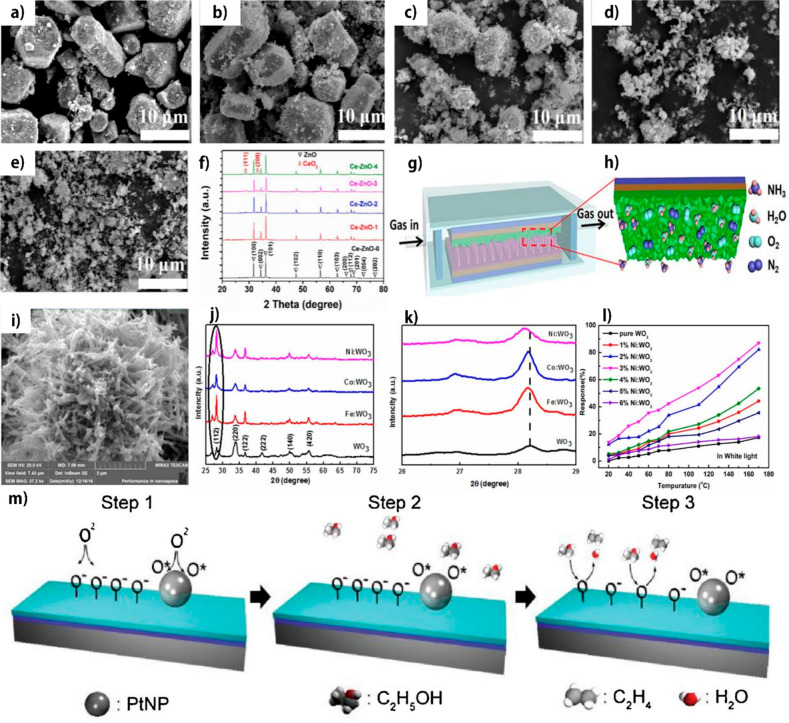

Hu et al. employed different metals (Cu, Co, Ni, and Sn) as dopants in plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) to create metal-doped ZnO-NR-based HCHO sensors. The introduction of metal doping can reduce the working temperatures and improve the sensing efficiency due to the reduced activation energy; Co-, Ni-, and Sn-doped ZnO NRs result in the highest response at 300 °C at which PI substrates can be used. Among metal dopings, Sn-doped ZnO NRs synthesized by PECVD exhibit a maximum response of 90% with Sn at 0.5% compared to ZnO NRs synthesized by precipitation and hydrothermal methods due to extensive crystal defects.194 The metal doping concentration can directly influence the morphology of the materials, leading to a high sensing efficiency.131 As seen in Figure 8a, pure ZnO NRs display a typical wurtzite hexagonal shape. On the other hand, the morphology of the Ce-ZnO composite changes slowly to NPs with increasing Ce-doping concentrations, as seen in Figure 8b,c. Consequently, the shape transforms to flocculent structures with partial agglomeration when the Ce-doping concentration is further increased (Figure 8d,e). Metal-doped triboelectric nanogenerators have been extensively exploited for self-powered respiration monitoring due to their appealing characteristics, including superior biocompatibility, low price, wearing ease, and excellent response to respiration activities. Wang et al. engineered a triboelectric self-powered respiration sensor (TSRS) based on a Ce-ZnO composite on a PET substrate, as observed in Figure 8f–h.131 Ce concentrations of 0, 0.001, 0.004, 0.007, and 0.01 M are indicated as CeZn-0, CeZn-1, CeZn-2, CeZn-3, and CeZn-4, respectively. Among these Ce concentrations, CeZn-2 exhibits the best selectivity and response value toward 20.13 ppm of NH3. Furthermore, the sensor displays a stronger NH3 response at low concentrations (0.1–1 ppm) than at large concentrations (1–10 ppm) when exposed to the same moisture as the breathing gas, demonstrating that TSRS can detect trace levels of the NH3 biomarker in human breathing gases.131 Another group developed a Cr-doped ZnO-based NH3 sensor with different Cr-doping ratios. Cr-ZnO with a 3 mol % Cr-doping concentration acquires the highest response efficiency due to the generation of extensive chemisorbed surface sites. In comparison, the surface becomes rougher at higher doping concentrations. It can be interpreted as that extra Cr dopants cause the agglomeration that cannot substitute Zn2+ ions in the wurtzite structure. Furthermore, Cr dopant boosts UV–vis absorption while decreasing the energy band gap.128 Namgung et al. used Al-doped ZnO NRs to fabricate low-temperature gas sensors and employ a Ag NW layer to compensate for the decreased conductivity due to Al doping.195 The fabricated sensor successfully sensed H2 and NO2.

Figure 8.

(a–e) SEM photos of Ce-ZnO at various Ce-loading amounts: (a) CeZn-0, (b) CeZn-1, (c) CeZn-2, (d) CeZn-3, and (e) CeZn-4. (f) XRD patterns of (a–e). (g) Diagram of the fabricated TSRS. (h) Focused view of the Ce-ZnO active layer. Adapted with permission from ref (131). Copyright 2019 Elsevier. (i) SEM photo of Ni-WO3 NFs. (j) XRD patterns of WO3 with various dopants. (k) Focused XRD patterns of j). (l) The 100 ppm acetone response of pristine WO3 and Ni-WO3 with various Ni-loading amounts. Adapted with permission from ref (132). Copyright 2021 IOPscience. (m) Sensing mechanism of ethanol detection of Pt nanoparticle/In2O3. Reprinted from ref (37), with permission from Elsevier.

Pi et al. investigated the sensing efficiency of WO3-NF-based acetone (CH3COCH3) sensors with different dopants, such as Co, Fe, and Ni.132 Via a hydrothermal method, metal-doped WO3 NFs were fabricated and showed a porous structure as shown in Figure 8i. Figure 8j,k indicates the different dopants are successfully doped on the WO3 surface, which exhibits a higher sensitivity to 100 ppm of CH3COCH3 than that of pure WO3 under various light sources (UV, green, and white lights). The Ni-WO3 composite displays the highest response under white light irradiation compared to other composites at the same intensity. Besides the effect of light irradiation, Figure 8l realizes the efficiency of Ni-doping concentrations at different working temperatures. At room temperature (RT), Ni-WO3 NFs have a sensitivity of 27%, whereas pure WO3 has almost no sensitivity without light irradiation. Park et al. produced lanthanum (La)-doped Al2O3 on PI substrate (Table 1) via a sol–gel method to develop capacitive-type flexible temperature sensors that operate at 1 V, 1 MHz achieving a good sensitivity across an extensive temperature range (30–200 °C) as well as excellent mechanical properties in cyclic bending tests with a 5 mm curvature radius.129 They established a wearable body temperature sensor device in the form of an armband, which could lead to a potential path for wearing bioelectronics.

Employing a nanomaterial as a catalyst is a widely used method to improve the sensing performance of MON-based flexible gas sensors. Noble metals such as Pd,196 Ag,195 and Pt37,150,197 are well-known as dissociation catalysts for gases including H2,150,196 NO2,197 and O2.37,195 These noble metal NP catalysts were exploited to detect NO2,195,197 H2,150,196 and EtOH.37Figure 8m shows the catalysis of Pt NPs in the EtOH sensing process of In2O3. Adsorbed oxygen molecules on the surface of In2O3 were dissociated to O– species, and the O– species reacted to EtOH molecules at exposure. At ambient temperature, the Pt NPs/In2O3-based sensor can detect 238 ppb of EtOH vapor. Furthermore, the response reaches 105 ± 15 as the density of Pt NPs changes from 8 to 163 μm2 due to the increased charged oxygen ions and specific surface area. As the density of Pt NPs exceeds 163 μm2, this response is unchanged.37 Rashid et al. decorated Pd NPs on ZnO NRs using a sputtering method.134 The loading time is directly proportional to the thickness of the Pd layer. The Pd-doped ZnO at 15 s loading time displays a high response of ∼91% at RT and is stable until 105 bending/relaxing cycles for 1000 ppm of H2. The response time is also rapid, i.e., 18 s, with a LOD of 0.2 ppm, while the shorter loading time shows a lower response. Khan et al. produced Pd-doped SnO2 NPs on PI substrates via the inkjet-printing method.94 The chemo-resistance response for 50 ppm of CO in dry air is 2.1, while the response for NO2 at 5 ppm is 3.4. The response to CO is practically halved in wet air. Yang et al. functionalized CeO2 NPs with various noble dopants, namely Au, Ag, and Pd, via a mild thermal method. Ag- and Pd-CeO2 NPs displayed random aggregation like CeO2 NPs.130 While functionalized CeO2 NPs with Au NPs displayed a flake structure, the Au-CeO2 NPs achieved the highest sensing efficiency to gases in the order SOF2 < SO2 < H2S at 100 °C, versus Ag-CeO2NPs, Pd-CeO2 NPs, and pristine CeO2NPs, while Pd-CeO2 NPs showed the highest sensitivity to SO2F2 at 250 °C due to the largest surface area.

Also, localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) can improve the response. For instance, ZnO NRs were hydrothermally grown on a Ag NP template to cause LSPR. The interaction with the Ag NPs intensely scattered the incident light through the LSPR, and absorption intensity increased. As a result, the photoresponse of the sensor was improved.

5.2. Hybridization

Hybridization is preferred owing to the synergistic effects of MON properties with another material, especially superior chemical and mechanical features. Generally, both n-type and p-type MONs facilitate core–shell heterostructures that have shown promising results, possibly because excited electrons of n-type that transfer to p-type holes get moved in the reverse direction until equilibrium is reached at the Fermi level. As a result, the formation of hole depletion layers increases chemisorbed oxygen species as well as increases the oxidation reaction on the sensing surface, increasing the resistance of materials.199 Comprehensive studies have been carried out in recent years, demonstrating that hybridization is superior to conventional MONs in diverse sensing areas of gas sensors, humidity sensors, and biosensors. The main aim of the sensing facilitates the robust target response at optimal temperature.

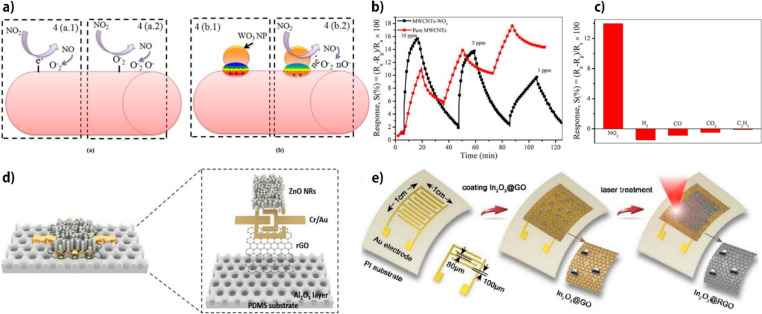

5.2.1. Binary Hybridization with an Inorganic Material

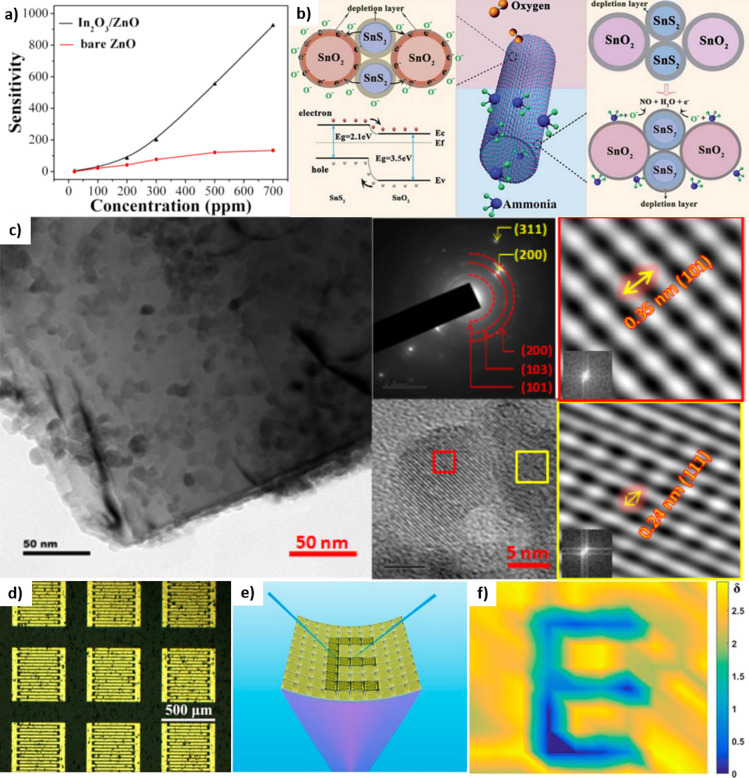

Several studies have improved the performance of sensors through synergetic effects by combining different types of oxides. For an example of heterogeneous MONs of flexible gas sensors, Liu et al. introduced porous SnO2/Zn2SnO4 nanospheres.200 Zn2SnO4 is a desirable n-type semiconductor due to its high conductivity, electron mobility, and chemical stability, and Zn2SnO4 becomes more attractive when it combines with SnO2 since SnO2 assists electron–hole separation because of its higher conduction band position of Zn2SnO4. Thus, SnO2 performs as a sink, enhancing the electrical conductivity of the SnO2/Zn2SnO4 nanosphere and improving gas sensing performance. Also, ZnO nanothorns grown on the surface of NiO nanocones were introduced to improve the response and recovery time of the flexible gas sensor because abundant negative charge carriers in ZnO accelerate the adsorption and desorption of gas molecules.201 The response/recovery speed and sensitivity of the NiO/ZnO-based NH3 sensor showed less dependence on the humidity and temperature than those of pure NiO nanomaterials-based sensors. Moreover, In2O3/ZnO heterostructure nanoarray-based self-powered gas sensors that achieved high sensitivity and selectivity toward H2S were reported.202 Since the conversion of In2O3/ZnO to In2S3/ZnO, which occurred during the sensing process, strongly adjusted the free-carrier piezo-screening effect of ZnO rather than the gas adsorption, the sensor showed a higher sensitivity than pure ZnO-based sensor as shown in Figure 9a.

Figure 9.

(a) Comparison of In2O3/ZnO heterostructure sensitivity and bare ZnO-based H2S gas sensor. Reproduced from ref (202). Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society. (b) Schematic of the mechanism of SnO2/SnS2 heterojunction enhancing sensing performance. Reprinted from ref (96) under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. (c) TEM, SAED, and focused TEM data of TiO2@2D-TiC NSs hybrid. Reproduced from ref (142). Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. (d) Optical image of the photodetector array based on the ZnO NP modified Zn2SnO4 NWs. (e) Schematic of the photodetector array sensing the letter “E” under compressive bending. (f) Resulting output image from the flexible photodetector array. Reproduced from ref (183). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

Metal sulfides were also exploited to construct heterogeneous structures of nanomaterials for flexible gas sensors and enhance the sensing performances. Li et al. demonstrated a SnO2/SnS2-NT-based adjustable NH3 gas sensor at RT.96 Since the conduction band of SnO2 is higher than that of SnS2, the SnO2/SnS2 heterojunction leads to the construction of the accumulation layer on the surface of SnO2 and the thin depletion layer on the surface of SnS2, as shown in Figure 9b. The hybridized SnO2/SnS2 sensor promotes a superb response value of 2.48 to 100 ppm of NH3 versus pristine SnO2 NTs due to the synergetic effect of the two different materials. Furthermore, ZnS was employed to enhance the stability of the H2S sensing ZnO. In fact, ZnO NWs are unsuitable materials for the H2S sensor because ZnO reacts with H2S and transforms to ZnS irreversibly, but Yang et al. demonstrated a ZnO/ZnS core–shell NW-based H2S sensor by sulfurizing the surface of the ZnO NWs.110

MXenes, emerging 2D materials including Ti3C2Tx and TiC, known as suitable materials to decrease the signal-to-noise ratio of the gas sensor, were also studied to improve MON-based flexible sensors. For instance, a wearable and flexible EtOH sensor based on TiO NPs grafted on 2D-TiC NSs operating on a PET substrate at RT was reported.142 Schottky-type p–n junctions formed at the TiO2/TiC interface improved the response, selectivity to EtOH gas, and signal-to-noise ratio of the sensor. The hybrid NS surface with the uniform organization of TiO2 NPs (Figure 9c) generates an outstanding amount of chemisorbed O2 sites, resulting in excellent response and selectivity to 10 ppb to 60 ppm of EtOH. In addition to the 2D structure, 3D structured MXenes were applied to the MON-based flexible gas sensor. 3D crumpled MXene, Ti3C2Tx, spheres decorated with ZnO NPs were developed via ultrasonic spray pyrolysis self-assembly and utilized as the NO2 sensing material.203 The crumpled structure of the MXene sphere possesses a larger specific surface area and more plentiful edges and defects than the 2D MXene sheet, resulting from the crumpled geometry and p–n heterojunction between MXene and ZnO. Moreover, these characteristics enhanced the responsive intensity, gas absorbing property, selectivity toward NO2 gas, and res/rec times of the sensor.

Arrays of photodetectors also were developed as flexible image sensors. Li et al. fabricated drastically improved flexible UV photodetectors composed of ZnO NP decorated Zn2SnO4 NWs.183 Due to the type II heterojunction between ZnO NPs and Zn2SnO4 NWs, electron–hole pairs were effectively separated and trapped holes in ZnO NPs resulted in a local positive gating effect to the n-type Zn2SnO4 NW channel, inducing augmentation of electron concentration in the NWs. The ZnO NP decoration improved the responsivity of the UV photodetector via this mechanism. Furthermore, UV image sensors were demonstrated by fabricating 10 × 10 arrays of the photodetectors to detect images under diverse bending states (Figure 9d–f).

5.2.2. Binary Hybridization with an Organic Material

5.2.2.1. Hybridization with Polymer

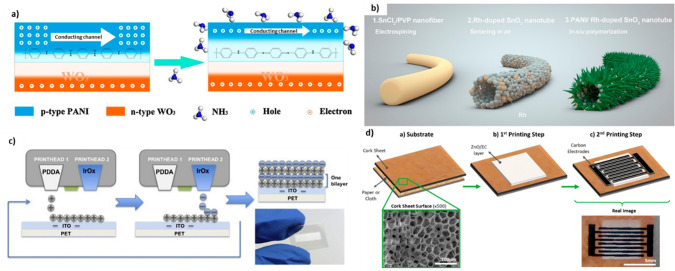

PANI, a p-type semiconducting polymer, can be used as a detecting material of NH3 sensors because =NH+– and −NH2+– groups of PANI provide protons to NH3 molecules.204 However, its development has been hindered by its low reaction, delayed response, and recovery. PANI can be composited with n-type MONs such as SnO2,95,205 CeO2,198 WO3,206 SnO2/Zn2SnO4,200 and SeGe4O9207 which highly enhances its sensing characteristic due to the p–n heterojunction formed at the interface between PANI and MONs. Figure 10a shows the NH3 sensing mechanism via PANI and n-type MON heterostructures. When PANI is exposed to NH3, NH3 induces the transformation of PANI from the emeraldine salt form to the emeraldine base form and increases the resistance of PANI by capturing protons to NH3. Therefore, the depletion region at the PANI side of the p–n heterojunction becomes larger. Accordingly, the conducting channel of PANI becomes narrow and its resistance increases. Liu et al. reported the hybridized heterostructure of PANI and Rh-SnO2 hollow NTs (PRS) via electrospinning and in situ polymerization approaches, which exhibited a NH3 sensor with a hollow tubular structure, as shown in Figure 10b.95 The hybridization structure demonstrated the greatest sensitivity value of 13.6 to 100 ppm of NH3 with outstanding selectivity and good reliability. Furthermore, this heterostructure can be monitored by the polymerization method. The introduction of metal oxides possibly tunes the hybridization morphology. Another group fabricated PANI-CeO2 NP hybrid NH3 gas sensors on PI substrates via a deposition method.198 CeO2 NPs could influence the morphology of the PANI shell by arranging the PANI chains. This hybridization-based sensor gained an increased res/rec time, superb reproducibility, and linear concentration response as well as excellent selectivity and stability. On the other hand, it achieved an ultralow LOD (0.274 ppb) and exceptional flexibility without reducing sensitivity after 500 bending/extending cycles. By taking advantage of the piezoelectric and excellent mechanical properties of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF). A self-powered pH sensor is constructed on a hybrid composite-based piezoelectric nanogenerator (PNG) of ZnO NWs and PVDF.208 Due to the homogeneous and disaggregated ZnO NWs in the film, this hybrid nanogenerator produces a maximum open-circuit voltage and short-circuit current corresponding to 6.9 V and 0.96 μA, respectively, under uniaxial compression. Also, it operated five green LEDs without the assistance of energy. An inkjet-printed IrOx-based flexible pH sensor was demonstrated by layer-by-layer printing IrOx NPs and polydiallyldimethylammonium (PDDA) on the ITO/PET electrode, as shown in Figure 10c.156 The PDDA/IrOx bilayer was printed in up to five layers since the negatively charged PDDA polymer functioned as an adhesive layer between the positively charged substrate and IrOx NPs as well as between positively charged IrOx NP layers. The inkjet-printed sensor showed a rapid, linear, and near-Nernstain pH response of 59 mV/pH. IrOx-based pH sensing two-electrode system arrays have been fabricated via a sol–gel process over metal electrodes on PI substrates.160,161

Figure 10.

(a) Sensing mechanism of the NH3 of PANI/WO3 composite. Reprinted from ref (206), with permission from Elsevier. (b) Schematic of the preparation of PRS NT-based NH3 sensor. Adapted with permission from ref (95). Copyright 2021 Elsevier. (c) Schematic of layer-by-layer inkjet-printing approach of negatively and positively charged particles for pH sensing. Adapted with permission from ref (156). Copyright 2018 Elsevier. (d) Preparation of ZnO/EC nanocomposite for UV sensing, Reprinted from ref (178) under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The conductive H3O+ ions provided by water molecules adsorbed by CuO NPs also reduced the resistance of the PVA-PEO-CuO nanocomposite.174 The porous structure of the composite also is speculated to enhance the humidity sensing performance. A sustainable, flexible UV sensor was also revealed based on MONs. Figueira et al. fabricated a sustainable, flexible UV sensor by printing ink containing ZnO NPs and ethylcellulose (EC) on cork substrates.178 The fabrication process was entirely conducted by screen printing, as observed in Figure 10d.

5.2.2.2. Hybridization with Carbon Materials